En Haseva

Orthophoto of En Haseva

Orthophoto of En HasevaClick on Image to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

From Drone Survey by Jefferson Williams 12 Jan. 2023

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| En Haseva | Hebrew | |

| Mezadit Hazeva (or Mezad Haseva) | Hebrew | מצודת חצבה |

| Ain Husub | Arabic | اين هوسوب |

| Hosob | German (Musil) | |

| Tamara | Latin | |

| Thamana | Latin | |

| Thamaro | ||

| Tamar | Biblical Hebrew |

‘En Hazeva, situated in the Arava ~38 km. south of the Dead Sea, contains remains from the Late Iron Age I, IIa, and IIb as well as a Roman Fort that appears to be associated with the Diocletianic military build-up in the region (Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes, 2019). It also has levels of Nabatean, Byzantine, and Early Arab occupation. Identification of the site with Latin Tamara is widely accepted (Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes, 2019) - perhaps with Biblical Tamar as well. The site was excavated by R. Cohen and Y. Israel between 1987 and 1994-1995 but a final report was not published before Rudolph Cohen passed away in 2006. Tali Erickson-Gini is working on a Final Publication.

Mezad Hazeva (map reference 1734.0242) was established on a hill adjacent to the southern bank of Nahal Hazeva, close to 'En Haseva in the northern Arabah. Researchers who toured the area in the nineteenth century discovered remains near the spring. A Musil, on a visit to the site in 1902, prepared a sketch of the fortress and determined that its plan was square, each of its sides being about 90 m long, with protruding corner towers. He observed another building, adjoining the fortress on the south, that contained several rooms and the remains of a bathhouse to the east. The fortress was severely damaged in 1930, and its original plan could no longer be discerned. In 1932, the site was visited by F. Frank. Subsequently, A. Alt concluded that the large structure at Hazeva was a Roman fortress. N. Glueck, who visited the site in 1943, was of the opinion that the building was a khan established by the Nabateans that the Romans continued to use. He identified Hazeva with Eiseiba (Εισειβα), which appears on a list of settlements in the Negev and the amount of the annual tax imposed on them by the Byzantine authorities (the so-called Beersheba edict; Alt, GIPT, no. 2). B. Mazar and M. Avi-Yonah, who visited Haz~eva in 1950, found several Iron Age sherds in addition to decorated Nabatean potsherds and sherds from the Roman-Byzantine period. Following this discovery, Y. Aharoni proposed identifying Hazeva with biblical Tamar and Roman Tamara. This view was opposed by B. Rothenberg, who noted that no Roman coins earlier than the fourth century CE had been found at the site; he therefore located Roman Tamara at Mezad Tamar (q.v.).

In 1972, excavations were conducted at Mezad Hazeva under the direction of R. Cohen, on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums. The excavations were renewed from 1987 to 1990, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, under Cohen's direction.

... In the excavator's opinion, the excavation results at Mezad Hazeva strengthen the identification of the site with biblical Tamar. In his view, this was a central fortress on the southeastern border of the kingdom of Judah. Its specific role in the fortification system of Judah and Edom has yet to be established.

- Location Map from

biblewalks.com

Map of the area – during the Biblical periods

Map of the area – during the Biblical periods

En Haseva is labeled as Tamar

(based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Location Map from

Cohen and Yisrael (1995)

'En Haseva sits at a stratgeically crucial commercial crossroads, especially vital for the Arabian spice trade

'En Haseva sits at a stratgeically crucial commercial crossroads, especially vital for the Arabian spice trade

Cohen and Yisrael (1995) - Map of the main Iron

Age sites in the Negev Hills (En Haseva not included) from Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

Map of the main Iron Age sites in the Negev Hills

Map of the main Iron Age sites in the Negev Hills

En Haseva not included

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 3)

- Annotated Satellite Image (google) of

En Haseva from biblewalks.com

- Oblique Aerial Shot of Entire Site

by Jefferson Williams

Oblique Aerial Shot of entire excavated site of En Hatseva

Oblique Aerial Shot of entire excavated site of En Hatseva

Photo by Jefferson Williams 12 Jan. 2023 - Oblique Aerial Shot of Entire Site

(cropped) by Jefferson Williams

Cropped Oblique Aerial Shot of entire excavated site of En Hatseva

Cropped Oblique Aerial Shot of entire excavated site of En Hatseva

Photo by Jefferson Williams 12 Jan. 2023 - Aerial View of En Haseva

from biblewalks.com

Aerial View of En Haseva

Aerial View of En Haseva

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Outline of early Israelite

fortress in En Haseva from biblewalks.com

- Outline of Roman

fortress, bathhouse, and Inn in En Haseva from biblewalks.com

- Fig. 1.83 - Aerial Photo of

site from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.83

Figure 1.83

‘En Hazeva, 1990-1994 excavations (Note revised plan of the cavalry camp in Fig. 1.58)

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Oblique Aerial Shot of Iron Age

Gate by Jefferson Williams

Oblique Aerial Shot of Iron Age Gate at En Hatseva

Oblique Aerial Shot of Iron Age Gate at En Hatseva

Photo by Jefferson Williams 6 Jan. 2023 - Fig. 11 - Aerial photo

of Area E from Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Aerial photo of Area E prior to balk removal, looking northwest

Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019) - En Haseva in Google Earth

- En Haseva on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 1.83 - Aerial Photo of

site from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.83

Figure 1.83

‘En Hazeva, 1990-1994 excavations (Note revised plan of the cavalry camp in Fig. 1.58)

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.83 - Site plan from

from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.83

Figure 1.83

‘En Hazeva, 1990-1994 excavations (Note revised plan of the cavalry camp in Fig. 1.58)

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Site plan with Cohen's

original stratigraphy (in Hebrew where שִׁכבָה = Stratum) from Cohen and Israel (1990)

Site plan with Cohen's original stratigraphy (in Hebrew)

Site plan with Cohen's original stratigraphy (in Hebrew)

שִׁכבָה = Stratum

Cohen and Israel (1990)

- Fig. 1.83 - Aerial Photo of

site from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.83

Figure 1.83

‘En Hazeva, 1990-1994 excavations (Note revised plan of the cavalry camp in Fig. 1.58)

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.83 - Site plan from

from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.83

Figure 1.83

‘En Hazeva, 1990-1994 excavations (Note revised plan of the cavalry camp in Fig. 1.58)

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Site plan with Cohen's

original stratigraphy (in Hebrew where שִׁכבָה = Stratum) from Cohen and Israel (1990)

Site plan with Cohen's original stratigraphy (in Hebrew)

Site plan with Cohen's original stratigraphy (in Hebrew)

שִׁכבָה = Stratum

Cohen and Israel (1990)

- Plan of fortresses at En Haseva

from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Mezad Hazeva: plan of the Roman fortress and the two Iron Age fortresses

Mezad Hazeva: plan of the Roman fortress and the two Iron Age fortresses

Stern et. al. (1993) - Fig. 1.84 - Plan of Late

Roman Fort from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.84

Figure 1.84

‘En Hazeva Late Roman Fort

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Artist's depiction of the

Middle Fortress at En Haseva from Cohen and Yisrael (1995)

The middle fortress (Stratum 5) from the ninth-eighth centuries BCE occupies roughly four times the areal extent

of contemporaneous Negev fortresses. Perhaps the site should be regarded as a small administrative city, like the Judean

fortified city of Tel Beersheba, rather than a large fortress. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The middle fortress (Stratum 5) from the ninth-eighth centuries BCE occupies roughly four times the areal extent

of contemporaneous Negev fortresses. Perhaps the site should be regarded as a small administrative city, like the Judean

fortified city of Tel Beersheba, rather than a large fortress. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Cohen and Yisrael (1995)

- Plan of fortresses

at En Haseva from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Mezad Hazeva: plan of the Roman fortress and the two Iron Age fortresses

Mezad Hazeva: plan of the Roman fortress and the two Iron Age fortresses

Stern et. al. (1993) - Fig. 1.84 - Plan of Late

Roman Fort from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.84

Figure 1.84

‘En Hazeva Late Roman Fort

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Artist's depiction of the

Middle Fortress at En Haseva from Cohen and Yisrael (1995)

The middle fortress (Stratum 5) from the ninth-eighth centuries BCE occupies roughly four times the areal extent

of contemporaneous Negev fortresses. Perhaps the site should be regarded as a small administrative city, like the Judean

fortified city of Tel Beersheba, rather than a large fortress. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The middle fortress (Stratum 5) from the ninth-eighth centuries BCE occupies roughly four times the areal extent

of contemporaneous Negev fortresses. Perhaps the site should be regarded as a small administrative city, like the Judean

fortified city of Tel Beersheba, rather than a large fortress. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Cohen and Yisrael (1995)

- Fig. 4 - Plan of the eastern

part of the Roman camp from Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019)

Figure 4

Figure 4

The eastern part of the camp, plan

JW: locations

Room 45 - upper right

Wall 785 - mid right

Room 53 - bottom center

Wall W578 - bottom right

Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019) - Fig. 1.58 - Plan of Late

Roman cavalry camp from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.58

Figure 1.58

Late Roman cavalry camp, ‘En Hazeva

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.59 - Cavalry camp

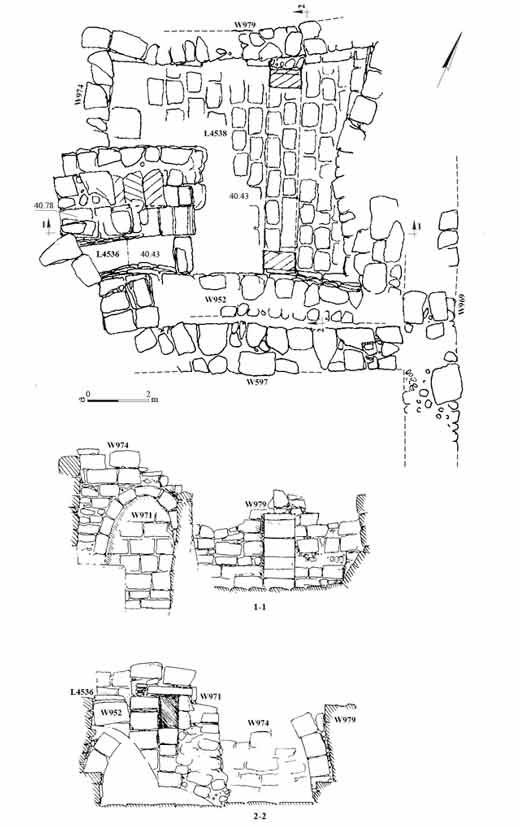

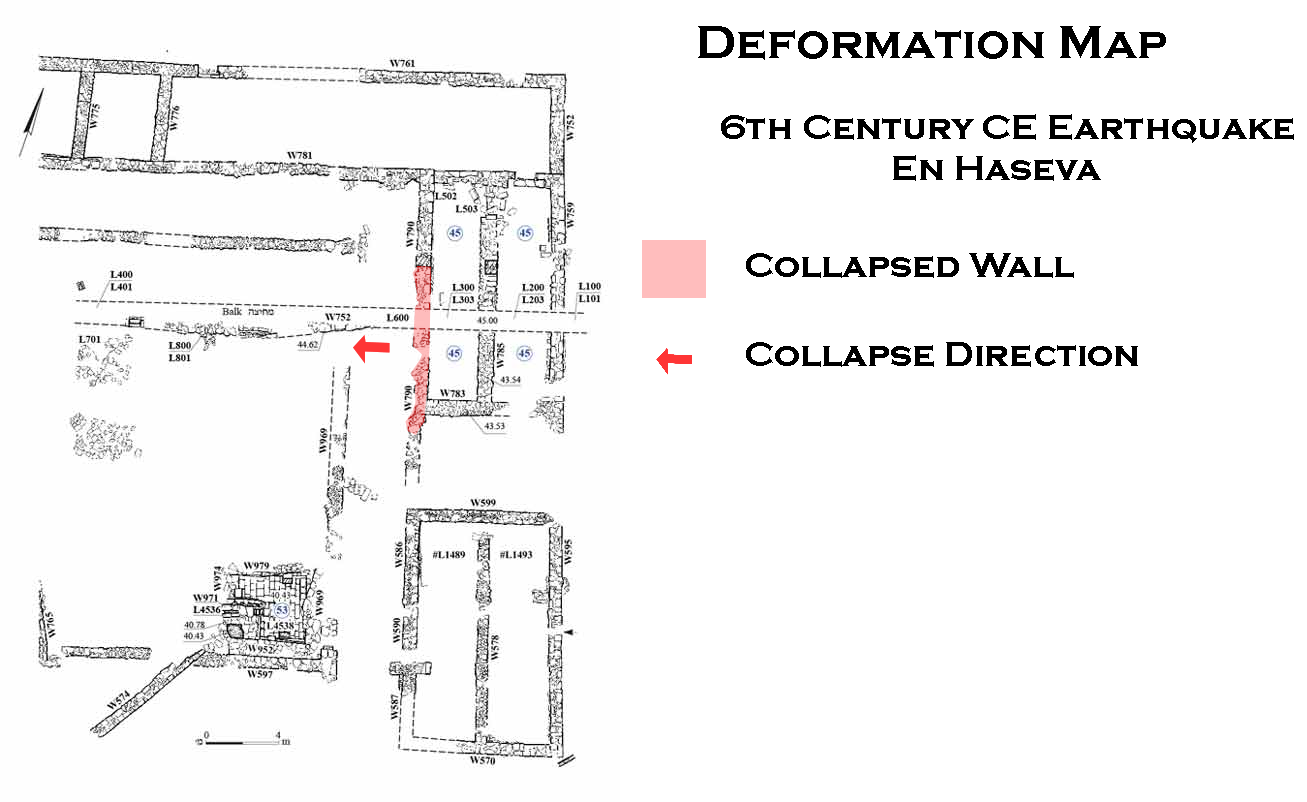

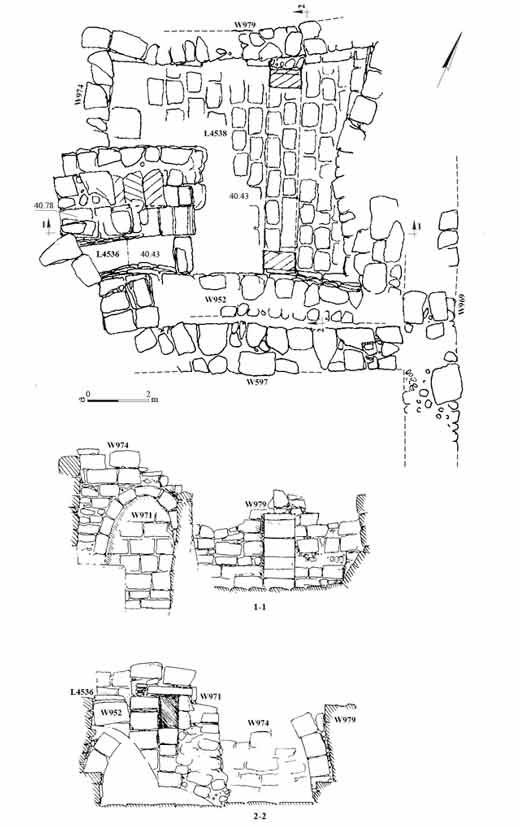

treasury vault sections (before and after Late Roman or Byzantine Earthquake from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.59

Figure 1.59

'En Hazeva cavalry camp treasury vault sections

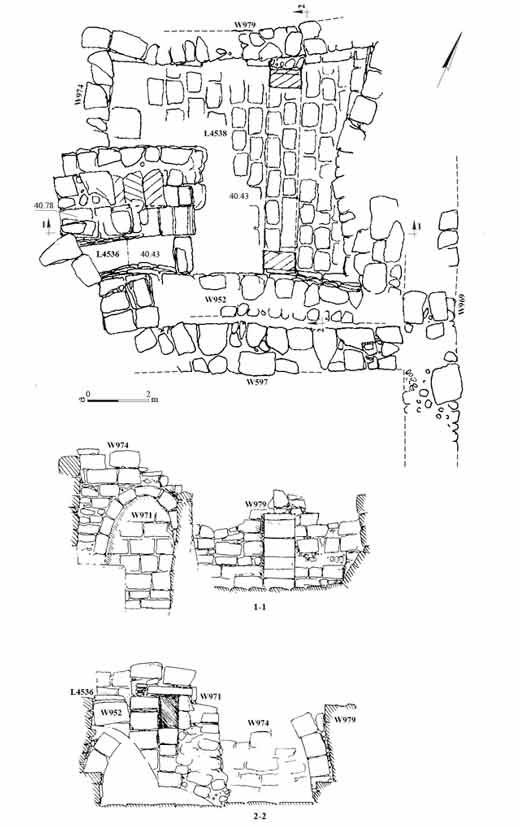

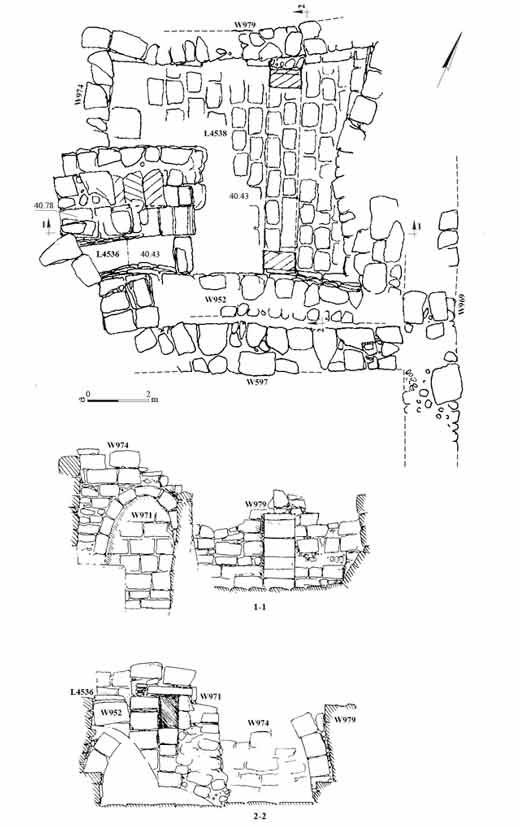

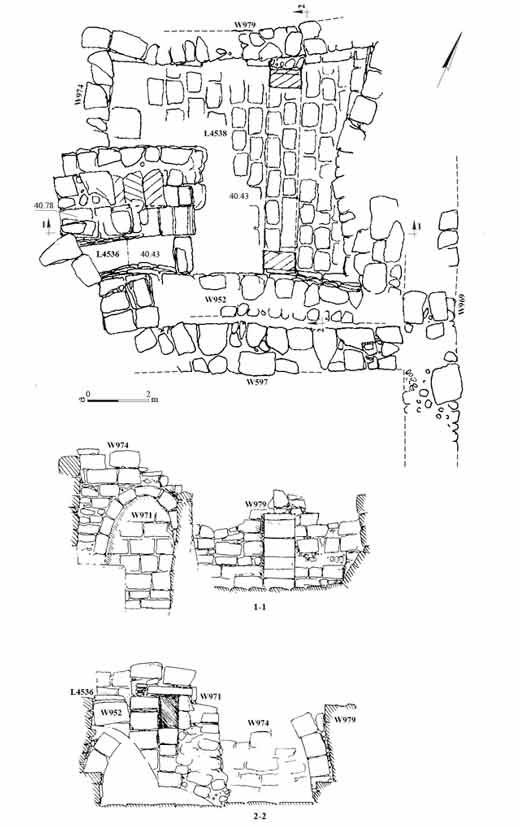

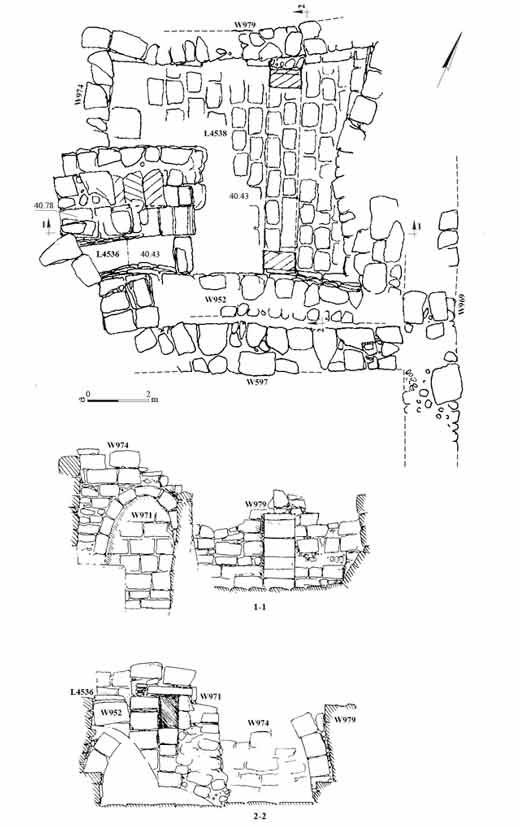

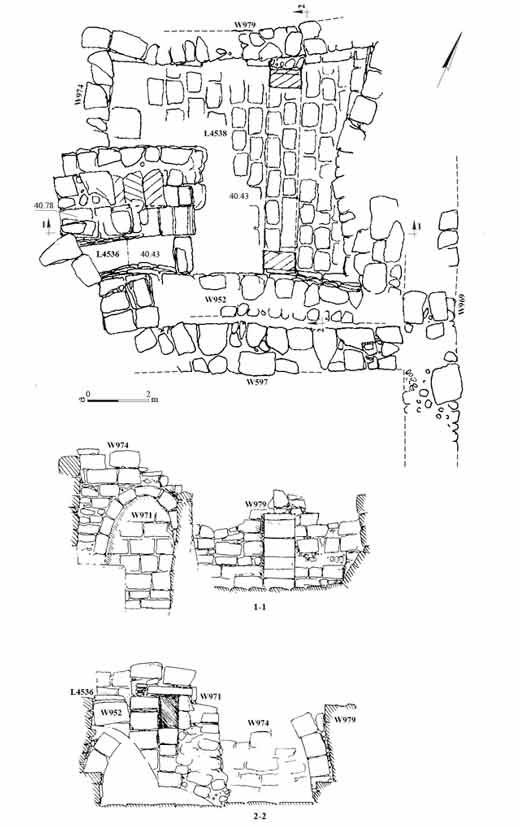

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 9 - Plan and sections

of Room 53 from Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Room 53, plan and sections

Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019)

- Fig. 4 - Plan of the eastern

part of the Roman camp from Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019)

Figure 4

Figure 4

The eastern part of the camp, plan

JW: locations

Room 45 - upper right

Wall 785 - mid right

Room 53 - bottom center

Wall W578 - bottom right

Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019) - Fig. 1.58 - Plan of Late

Roman cavalry camp from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.58

Figure 1.58

Late Roman cavalry camp, ‘En Hazeva

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.59 - Cavalry camp

treasury vault sections (before and after Late Roman or Byzantine Earthquake from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.59

Figure 1.59

'En Hazeva cavalry camp treasury vault sections

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 9 - Plan and sections

of Room 53 from Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Room 53, plan and sections

Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of ‘En Hazeva, Phase VIIB

(drawn by D. Poretzki, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 3

Figure 3Plan of ‘En Hazeva, Phase VIIA

(drawn by D. Poretzki, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 2

Figure 2Plan of ‘En Hazeva, Phase VIIB

(drawn by D. Poretzki, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 3

Figure 3Plan of ‘En Hazeva, Phase VIIA

(drawn by D. Poretzki, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Table 1

Table 1Radiocarbon measurements, their archaeological contexts, and calibrated ranges without modelling. The δ13C was measured in the AMS

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 15

Figure 15Modelled probability distributions of ‘En Hazeva, based on stratigraphic model. The agreement of the model is 69%. The modelled distribution is marked with dark grey or colour, while the borders and highly transparent colouring mark the entire unmodelled probability distribution. The upper line below the distributions is the 68.3% range, and the lower line is the 95.4% probability

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 16

Figure 16Calibrated probability distributions on the Calibration Curve. The modelled distribution is marked with grey or colour, while the borders and highly transparent colouring mark the entire unmodelled probability distribution. The lines below the distributions mark the 68.3% range. The sample in red (RTD-12153) is stratigraphically the earliest sample at the site and falls at a low part of the wiggle around 960 BC. The two samples in green were taken from Phases VIIB and VIIA in situ contexts. Sample RTD 12207 comes from the latest use of Building 3011

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 17

Figure 17Separate sums of all the probability distributions of the radiocarbon dates published from ‘En Hazeva, Khirbet en- Nahas and Atar Haroa. The number of samples used for each sum-plot appears next to the site names. The dark grey area in the ‘En Hazeva plot denotes the modelled date range of the site.

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

- Fig. 14 - Wall 578 and

the eastern wall of the gatehouse (W595) from Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Wall 578 and the eastern wall of the gatehouse (W595), looking east.

Erickson-Gini and Moore Bekes (2019) - Fig. 1.85 - Restored

finds from 363 CE destruction layer in casemate rooms in Late Roman fort at ‘En Hazeva from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.85

Figure 1.85

Restored finds from the 363 CE destruction layer in the casemate rooms in the Late Roman fort at ‘En Hazeva

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.85 - Restored

finds from 363 CE destruction layer in casemate rooms in Late Roman fort at ‘En Hazeva from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.85

Figure 1.85

Restored finds from the 363 CE destruction layer in the casemate rooms in the Late Roman fort at ‘En Hazeva

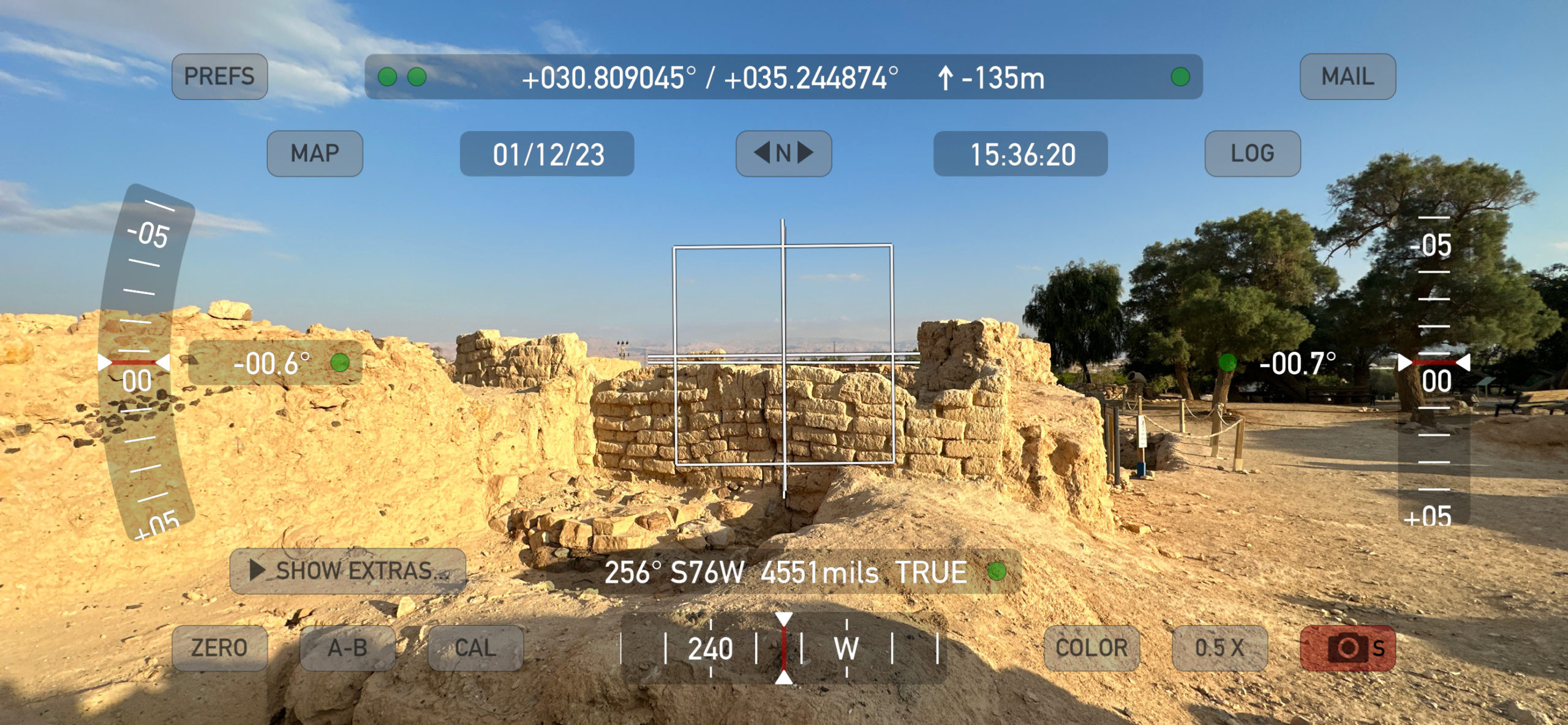

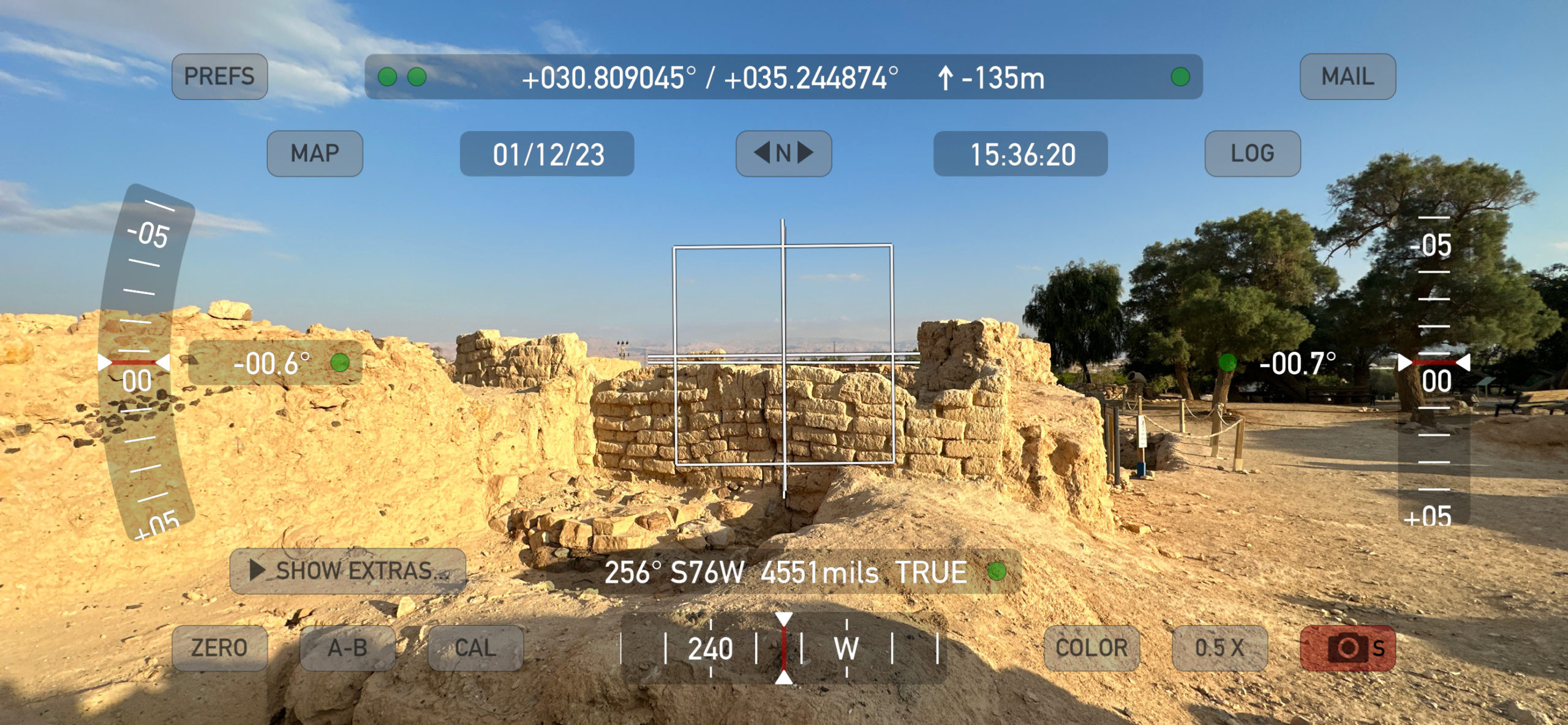

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Digital Theodolite photo

of the Iron Age Gate's Tilted Wall - photo by JW

Digital Theodolite Shot of Tilted Iron Age Gate Wall at En Hatseva

Digital Theodolite Shot of Tilted Iron Age Gate Wall at En Hatseva

Photo by Jefferson Williams 12 Jan. 2023 - Fig. 4 - Constructional

fills below Room 4’s floor from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Constructional fills below Room 4’s floor, looking west. Note there is no foundation trench for W330 on the left

(photograph by A. Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024) - Fig. 5 - Constructional

fills diagonally slanting from the outer face of Wall W340 from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Constructional fills diagonally slanting from the outer face of W340, looking south. The connection between the wall and the fills was cut in modern times

(photograph by A. Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024) - Fig. 6 - Constructional

fills diagonally slanting from the outer face of Wall W871 from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Constructional fills diagonally slanting from the outer face of W871, looking west

(photograph by A. Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024) - Fig. 7 - General view

of Building 3011 from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 7

Figure 7

General view of Building 3011, looking north-west. At the rear, Stratum VI mudbrick installation L3137

(photograph by A. Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024) - Fig. 9 - Building 3011

from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Building 3011, looking north-west; the location of the dated samples marked

(photograph by A. Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024) - Fig. 11 - Black surface

L131 extending under Building 3011’s southern foundation wall (W871) from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Black surface L131 extending under Building 3011’s southern foundation wall (W871); the location of dated sample RDT 12153 marked. Looking north

(photograph by A. Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024) - Fig. 12 - Wall W132

(St. VIII) and two related floors — L132 and L134 from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 12

Figure 12

W132 (St. VIII) and two related floors — L132 and L134, looking south-east; showing the location of dated sample RDT 12152

(photograph by J. Regev)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024) - Fig. 13 - Mudbrick superstructure

wall (W855) atop a stone foundation from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Mudbrick superstructure wall (W855) atop a stone foundation showing the location of dated sample RDT 12155, looking east

(photograph by A. Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024) - Fig. 14 - Floor 130 (Phase VIIB; Room 3)

with circular deposit of dark heat-altered sediments (L129) from Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Floor 130 (Phase VIIB; Room 3) with circular deposit of dark heat-altered sediments (L129), looking north-west; showing the location of dated sample RDT 12154

(photograph by A. Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE |

Table 1

Table 1A chronological scheme for the Levant (after Finkelstein 2010 and 2011; Regev et al. 2012; Sharon 2013).

Palmisano et al. (2019)

- Originally taken from ancientneareast.tripod.com

- Supplemented from ancientneareast.tripod.com

- This appears to match with the stratigraphy cited in more recent publications (e.g. by Tali Erickson-Gini, Ben-Ami et al, 2024)

| Stratum | Period | Approximate Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | Modern | 1900- |

|

| 1a | Early Islamic | 8th - 9th centuries CE |

|

| 2 | Byzantine | 4th-7th centuries CE | |

| 3 | Late Roman/Byzantine | 4rd-6th centuries CE |

|

| 4 | Roman | 3rd-4th centuries CE |

|

| 5 | Nabatean | 1st century BCE to 1st century CE | |

| 6 | Iron IIC ( Ben-Ami et al., 2024) |

7th-6th centuries BCE |

|

| 7b | Iron IIA or IIB Early Iron IIA ( Ben-Ami et al. (2024)) |

8th century BCE ~950-900 BCE ( Ben-Ami et al., 2024) |

|

| 7a | Late Iron IIA Early Iron IIA ( Ben-Ami et al., 2024) |

9th-8th centuries BCE ~950-900 BCE ( Ben-Ami et al., 2024) |

|

| 8 | Late Iron I Early Iron IIA ( Ben-Ami et al., 2024) |

10th century BCE ~1000-950 BCE ( Ben-Ami et al., 2024) |

|

- from biblewalks.com

| Strata | Date | Period | Findings |

| 1b | 20th Century AD | Modern | · Aqueduct, well, police station

· Kibbutz Ir-Ovot (1967- 1980s) |

| 1a |

7th-8th Century AD

|

Early Arab | · Buildings, farm |

| 2 | 4th-7th Century AD | Byzantine | |

| 3,4 |

2nd-4th Century AD |

Roman | · Square fortress (46m x 46m) with 4 corner towers

· Caravanserai, Bathhouse

|

| 5 |

1st Century BC- 1st Century AD

|

Nabatean | · Room with store jars under the Roman fortress |

| 6 |

7th-6th Century BC |

Late 1st temple | · Fortress

· Cult vessels from Edomite shrine · Four-room house

|

| 7b

|

8th Century BC | 1st temple | · Immense fortress (casemate wall

100m x 100m, 3 towers) · 4 chambers gate

|

| 7a

|

9th-8th Century BC |

1st temple | · Fortress (casemate wall 50m x 50m)

· 4 chambers gate

|

| 8 |

10th Century BC (Solomonic)

|

Unified Kingdom | · square fortress |

| Stratum | Period | Approximate Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Early Arab | ||

| 2 | Roman | 2nd-4th c. CE | Remains of a Roman fortress |

| 3 | Nabatean | 1st-2nd c. CE | |

| 4 | Iron Age | Iron Age fortress | |

| 5 | Iron Age | Iron Age fortress |

| Stratum | Period | Approximate Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Late Byzantine and Early Islamic | 6th-7th c. CE | |

| 2 | Late Roman | 3rd-4th c. CE | Remains of a Roman fortress |

| 3 | Nabatean and Early Roman | 1st-2nd c. CE | |

| 4 | Iron Age | 6th-7th c. BCE | |

| 5 | Iron Age | 8th-9th c. BCE | |

| 6 | Iron Age | 10th c. BCE |

- Artist's depiction of the

Middle Fortress at En Haseva from Cohen and Yisrael (1995)

The middle fortress (Stratum 5) from the ninth-eighth centuries BCE occupies roughly four times the areal extent

of contemporaneous Negev fortresses. Perhaps the site should be regarded as a small administrative city, like the Judean

fortified city of Tel Beersheba, rather than a large fortress. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The middle fortress (Stratum 5) from the ninth-eighth centuries BCE occupies roughly four times the areal extent

of contemporaneous Negev fortresses. Perhaps the site should be regarded as a small administrative city, like the Judean

fortified city of Tel Beersheba, rather than a large fortress. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Cohen and Yisrael (1995) - Fig. 5 The tilted Iron Age

wall of En Haseva from Austin et al (2000)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Foundation failure beneath the inside pier of the fortress gate at `En Haseva. Although the Iron Age fortress gate is superbly constructed of well-hewn stones, individual blocks within the pier cracked on several courses as the foundation compacted differentially. The whole pier of the gate now leans northeastward. The excavators of the gate complex associated destruction debris within the gate complex to damage caused by an earthquake, not foundation failure caused by a continuous process of creep.

Austin et al (2000) - Photo of Tilted Iron Age Gate Wall by Jefferson Williams

- Digital Theodolite photo

of the Iron Age Gate's Tilted Wall - photo by Jefferson Williams

Digital Theodolite Shot of Tilted Iron Age Gate Wall at En Hatseva

Digital Theodolite Shot of Tilted Iron Age Gate Wall at En Hatseva

Photo by Jefferson Williams 12 Jan. 2023

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

used radiocarbon to produce an absolute chronology for the so-called "Early Fortress"1 of Strata VIII and the

so-called "Middle Fortress"1 of Stratum VII. Stratum VIII was dated ending in ~950 BCE while both phases of Stratum VII (A and B) were dated to between

~950 and ~900 BCE.

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

assigned Stratum VIII to Iron Age I and both phases of Stratum VII to Iron Age IIA - which appears to follow Finklestein's Low Chronology2.

The date ranges of

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

were supplemented with pottery, cross-checked with radiocarbon dates from nearby sites, compared to architectural styles of the time, and assessed in regards to historical trends in the region.

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

contend that during the Early Iron Age IIA (Stratum VII), 'En Haseva was associated or involved with copper trade from the nearby copper mining and production site of Khirbet en-Nahas in Wadi Faynan.

They also concluded that abandonment at the end of Stratum VII in ~900 BCE was not due to Egyptian Pharaoh's Shoshenq I's ~925 BCE military campaign in Southern Canaan.

Post Stratum VII abandonment, according to

Ben-Ami et al. (2024),

lasted for nearly a couple of centuries showing no trace of later occupation activity

and the immense fortress established at ‘En Hazeva over the abandoned building (Stratum VI),

opens a new chapter in the site’s history, dating to the Iron Age IIB–C

.

Cohen and Yisrael (1995) suggested that the so-called "Middle Fortress"1 of Stratum VII was damaged by one of the

Amos Quakes while

Austin et al. (2000) and others

have suggested that the tilted wall (see Fig. 5) in the Casemate Gate was tilted by one of these earthquakes. However, Dogon Ben-Ami (pers. communication, 2024)3 indicates that

this Casemate Gate pier is in Stratum VI which dates its construction to nearly a couple of centuries

after ~900 BCE putting it outside of the time window for the

Amos Quakes - one of which struck in ~760 BCE.

Although the Amos Quakes are excluded, it is possible that a later earthquake caused the tilt.

However, there is a question why the other walls were not tilted. Dogon Ben-Ami (pers. communication, 2024)3 indicates that the tilted casemate pier is underlain by

a layered sediment foundation like that which underlies Building 3011

(see Ben-Ami et al., 2024)

while Roberts (2012:187-189) noted that floors were absent in the casemate walls. All of this points to a weak foundation which suggests an

alternate theory for the wall tilt - poor construction techniques eventually led to differential settlement.

In its current post excavated state, the wall

Although this would seem to close the Chapter on Amos Quake evidence at En Haseva, I am going to assign an Event probability of possible to unlikely rather than unlikely simply because a final excavation report has not yet been produced, there have been changes in chronology at En Haseva as new research uncovers new evidence, and work on the site is still on-going.

1 These designations come from Cohen and Yisrael (1995)

2 For details on competing Iron Age Chronologies in the south Levant see

deadseaquake.info's page for Iron Age in the Southern Levant

3 Underneath the Stratum VI gate pier (the tilted wall) is the foundation of the Stratum VII Building 3011.

21. 'Haseva

‘En Haseva (Tamar) stood as a massive 100m x 100m Iron Age fortress (or fortified city) on the southern border of ancient Judah about 35 km south of the Dead Sea. While excavation began in the early 1970’s, it was only in 1987 that the excavations, directed by Rudolph Cohen and Yigal Yisrael, uncovered an Iron Age fortress.135 In Cohen’s 1993 article that updated the discovery of the Iron Age fortress, he also noted that the end of strata 2, the Late Roman Period (third-fourth century CE) could have been due to the earthquake of 363 CE though he did not supply any evidence for his suggestion.136 While early on, there was very little pottery to help date the Iron Age strata, more discoveries helped excavators conclude that Stratum 5 was built in the ninth-eighth century rather than a century later as they previously thought. towers at the corners and an offset-inset casemate wall built of dressed stones. These walls surround a large courtyard with a four-room gate near the northeastern corner of the fortress with some storehouses and granaries near an inner courtyard surrounded by casemate walls. An interesting feature of the site is the absence of floors. In both the storehouses and in the casemate walls floors are absent and complete vessels were found in only two of the casemate rooms near the gate and in the granaries.

Regarding the end of Stratum V, the excavators suggest an earthquake, “Based on the destruction debris and its configuration, we believe that the quake mentioned in Amos and Zechariah was responsible for the destruction of…the gate complex…”137 They do not list reasons other than the foundation failure associated with the uneven compaction of the substrate.

There is little to evaluate Cohen and Yisrael’s view publication was limited to small reports and Cohen’s untimely death inhibited a full publication of the results though some reevaluation has taken place. For example, Nadav Na’aman has argued that the builders of Stratum V were not Judean kings, but Assyrians in the late eighth century.138 Na’aman sees three Assyrian forts in the Negev, at {En Haseva, in Wadi {Aravah near the copper mines, and on the road to the Gulf of Eilat in addition to those at Kadesh Barnea and Tell el-Kheleifeh. Na’aman’s suggestion of a later genesis in the building of {En H¸asΩeva’s fortress would certainly dismiss its fate at the hands of an earthquake though Na’aman does not explain how the Stratum V would have ended.139 David Ussishkin approaches stratum 5 from a different perspective, arguing that the casemate wall of the fortress and its monumental gate form the substructure of the complex and not the superstructure.140 He notes, more surprising, that this conclusion was reached with the excavators during a tour of the site during excavations of the stratum 5 gate. In sum, a superstructure of mostly mudbrick would sit on top of the stone substructure. Usshiskin sees evidence of a similar type of construction at other Iron II locations such as a courtyard gate at Megiddo dating to the VA-IVB Southern Palace as well as the inner gatehouse at Lachish from Level IV-III.141 Ussishkin raises some interesting points about the role of the stone walls and how this could affect earthquake interpretations. The parallel fortresses he provides would argue against Na’aman’s proposal of an Assyrian fortress as well as the date of its construction. All this to say, the fortress remains inconclusive for earthquake damage.

136 Rudolph Cohen, “The Fortress at 'En 'Haseva,” BA 57 (1994): 203-214. On the 363 CE earthquake, see Kenneth

W. Russell, “The Earthquake of May 19, A.D. 363,” BASOR 238 (1980): 47–64; Kenneth W. Russell, “The

Earthquake Chronology of Palestine and Northwest Arabia from the 2nd Through the Mid-9th Century A.D.,” BASOR

260 (1985): 37–59.

137 Cohen and Yisrael, “The Iron Age Fortreses,” 231. Austin et al., “Amos’s Earthquake,” 661-662, list ‘En Haseva

as one of the sites that corroborates evidence of earthquake damage.

138 Nadav Na’aman, “Notes on the Excavation of {Ein HasΩeva,” Qadmoniot 30 (1997): 60 (Hebrew); Nadav

Na’aman, “An Assyrian Residence at Ramat RahΩel?,” TA 28 (2001): 260-280.

139 To be fair, stratum 4 dates to the seventh-sixth centuries so a tight sequence is not needed to explain the end of

stratum 5 before stratum 4 began.

140 David Ussishkin, “{En H¸asΩeva: On the Gate of the Iron Age II Fortress,” TA 37 (2010): 246-253.

141 David Ussishkin, “The City-Gate Complex: A Synopsis of the Stratigraphy and Architecture,” in The Renewed

Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994) (Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv

University 22). Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 2004), 504–524.

This paper presents, for the first time, an analysis of the early Iron Age IIA occupation at ‘En Hazeva. A series of radiocarbon measurements from short-lived samples obtained from the site’s earlier occupation levels (Strata VIII–VII) were all dated to the 10th century BCE. It is noteworthy, that Stratum VII occupies the second half of the 10th century BCE exclusively, with its final phase around 900 BCE. Fixing the site’s absolute chronology has far-reaching implications, enabling the placement of the early Iron Age IIA settlement within the broader historical context. Situated c. 20 kilometres from the most significant copper industry centre in the Levant — Khirbet en-Nahas, ‘En Hazeva enjoyed a strategic location in the transport network of copper through the Negev Highlands and the Beer-Sheba Valley to the Mediterranean seaports. It is claimed that the economic prosperity related to copper production at Khirbet en-Nahas during the early Iron Age IIA was ‘En Hazeva’s raison d’être.

... The Iron Age is represented at ‘En Hazeva by three strata — VIII, VII and VI, ranging from Iron Age I to the Iron Age IIC (the Strata designation follows the new stratigraphical scheme that resulted from the preparation of the material for final publication). The earliest remains, dated to the Iron Age I (Stratum VIII), were retrieved mainly during the 2013 and 2023 excavations (above), which took place long after the Cohen-Yisrael project ended. They include a few architectural remains and related finds recovered in a limited area, stratigraphically located beneath the remains of Stratum VII and differing from them significantly in magnitude (this paper focuses on the early Iron Age IIA at ‘En Hazeva (Stratum VII). Stratum VIII’s remains were barely excavated and await more significant exposure, which is planned for the near future). The early Iron Age IIA remains at ‘En Hazeva, the focus of this paper, are primarily represented by a single structure — Building 3011, which displays a well-planned, skilfully executed architecture. The comprehensive study of the available material, including the 2023 excavation results, enabled radiocarbon dating and setting the building in the broader cultural sphere.

Remains belonging to Stratum VII were exposed below the Stratum VI fortress’ gate complex, which dates to Iron Age IIB–C. Given the spring nearby, the concentration of remains in this part of the site should not be considered coincidental. The remains ascribed to Stratum VII include Building 3011, as well as some wall segments and installations exposed nearby. Two stratigraphic phases were discerned in the building (Strata VIIB and VIIA); the later phase consisted mainly of raising the floor levels in most rooms, and some architectural alterations (Figs 2–3)5.

Building 3011 features a massive substructure. Despite being partly damaged by the construction of the immense fortress over it in the subsequent stratum, its foundation walls are relatively well preserved and stand to a considerable height, some measuring over 2.5 m. No foundation trenches for the substructure walls were distinguished, and this observation further emphasises Building 3011’s construction technique. The substructure followed the ‘built-up foundation walls’ (Ussishkin 1980: 10–11; 2004: 510–12). Accordingly, the foundation walls’ lower courses were built directly on the surface of the time, scarcely penetrating the earlier level. Short-lived organic samples retrieved from beneath the building’s southern wall (W871) were submitted to radiocarbon dating (RTD 12153, see below). As the foundation walls were gradually raised, fills were laid horizontally, at intervals, to fill in the spaces between the walls. This procedure was repeated until the internal space delineated between the foundation walls was filled to the desired height. Only then were the floors in the various rooms laid, directly over the extensively accumulated constructional fills. Evidently, the high foundation walls and massive constructional fills were intended to raise the structure’s living floors above its surroundings.

The constructional fill, consisting of two distinct units, was almost devoid of artefacts and stones (Fig. 4). The lower unit is a dark fill, while the upper is a thick layer of whitish-yellowish fill. The two fill units are easy to distinguish, indicating deliberate planning and execution. Constructional fills were also traced along the outer face of the building’s southern and eastern walls (W871 and W340, respectively); presumably, they surrounded the substructure walls on all four sides. These fills formed diagonal layers slanting at 45° from the outer face of the building’s foundation walls, toward the extant surface (Figs 5–6). On the eastern side, these earthen fills (L3238 + L3008+L3228+L127) were clad with stones on their lower outer end (W887, W706, W707). A thin blackish layer of ash, sandwiched between two hard, compact layers of white-coloured plaster, coated the southern side. The purpose of these coatings was to stabilize the sloping fills. The constructional fill created a podium-shaped substructure. As this construction process found similar reflections in the six-chambered gate at Tel Megiddo, it is appropriate to quote Ussishkin’s methodological observation (1980: 10):

Similar fills [constructional fills — DBA], some times ramp-shaped, were usually laid against the outer face of the foundation walls, to support them from outside. This way, the foundation walls are initially constructed as free-standing walls, and once stripped of the supporting constructional fill they would look like typical walls of the superstructure of a building. Furthermore, once the built-up foundation walls of the whole structure are exposed to their supporting constructional fill, they look like a free-standing structure built on the surface of the previous stratum.The foundation walls consisted of small and medium-sized stones, with some larger ones integrated into the building’s corners. The stones are unworked, sometimes only roughly hewn. Many are dark greyish flint stones of the Mishash Formation, others are brighter in colour, and belong to the Hazeva Group and the Taqiye Formation.6 No ashlars were used in any of the walls. These characteristics make the Stratum-VII walls distinct from those of the overlying Iron Age IIB–C fortress in the subsequent stratum. The latter was constructed solely of whitish-yellowish limestones. This choice of building materials for the substructure and superstructure of Building 3011 makes the distinction between the Stratum VII architectural remains and those of Stratum VI easy to follow. In some instances, the sun-dried mudbricks that formed Building 3011’s superstructure were discovered in situ; placed on top of the substructure’s stone walls. These mudbricks were of orangish-brownish and greyish hues and had average dimensions of 0.3 ×0.5×0.1 m. Short-lived organic samples retrieved from these mudbricks were sampled for radiocarbon dating (see below).

The building is rectangular, nearly square in plan (c. 13.0 × 12.0 m). It consists of five rooms: Room 5 in the centre, surrounded by Rooms 1–4 (Fig. 7). The entrance to the building was not exposed, but it is likely to have been located on the eastern wall (W340), facing the spring. Three doorways that connected Room 5 with three surrounding rooms in the north, east and south were excavated (Rooms 4, 3 and 2, respectively). The south-western side of this room and the southern part of Room 1 were consider ably damaged by the white mudbrick installation (L3137) that was constructed atop Building 3011 in the subsequent stratum (VI). Since this is the first time the building is being published, it deserves a brief description.

- Room 1 is an elongated space (9.5 × 2.5 m), located on the western side of the building. As noted, the southern side of the room was damaged by the later mudbrick installation built over it. To make room for the installation, the builders of the subsequent stratum had to dismantle some walls on the south-western side of Building 3011, mudbrick superstructure and stone substructure alike. Hence, W871 and W872 were poorly preserved here, and the southern part of W859 was almost entirely razed (see below). A partition wall might have divided this elongated room. No floor level was detected in the limited area not occupied by the Stratum VI installation.

- Room 2 is the smallest in the building (4.5 × 2.5 m), located on its southern side. The room’s western boundary was cut and built over by the Stratum VI mudbrick installation. An entrance set in the north-eastern corner of the room connected it with the central Room 5. The floor features a stone-paved foundation (L3217), slightly slanting eastward toward the doorway.

- Room 3 (6.0 ×2.5 m) occupies the eastern side of

Building 3011. Mudbricks were preserved in situ

along W855 on the west, and W841 on the north.

The single entryway into this room was set in W332

+W855, connecting it with Room 5. The entrance is

flanked by two mudbrick doorposts, preserved to a

height of 1 m above the floor. During the early

phase (VIIB), a compact earth floor (L130, excavated

in 2023), abutted the threshold. Hand-made pottery

(mostly referred to as ‘Negebite ware’), including a

complete hand-made juglet, was found on this floor

along with wheel-made pottery. A thick, circular

layer of dark ash (L129, excavated in 2023) was

found in the north-western corner of the room. This

ash material is evidence of a circular installation

whose walls were almost entirely dismantled in the

subsequent phase. The ash contained charred date

pits that yielded a radiocarbon date in the later part

of the 10th century BCE (RTD 12154, see below).

Fragments of a hand-made vessel lay in the ash.

During Phase VIIA, the floor level was raised by c. 0.5 m, and a new compact earth floor was added above the previous one. A single flagstone abutting the northern doorpost was preserved in situ in the later threshold. A circular installation (L1699) was set in the northern part of the room. The installation was constructed of whitish-greenish clay. Similar installations were also excavated in Rooms 4 and 5 (below). Ash layers were excavated inside and next to the installation. A complete hand-made cooking krater was found on the floor close to Installation L1699. A narrow mudbrick wall (W873) was built perpendicular to the doorpost in W855. This thin mud brick wall stretched eastward, serving as a short partition wall in Room 3. A compact earth floor, L3126, was excavated in the southern part of this room. A semi-circular installation, L3130, similar to L1699 above, was unearthed just south of the partition wall W873, leaning against the eastern face of W855. - Room 4 is a large rectangular space (8.0 × 2.6 m) that occupies the northern side of Building 3011. A stone-built threshold connecting Room 4 with the central Room 5 was unearthed at the eastern end of W330. The original floor (Phase VIIB, L1620b), visible in the section that cuts into the room’s eastern side, rests directly over the massive constructional fill mixed with mudbricks and mudbrick material. In the later phase (Phase VIIA), the floor level was raised by c. 0.65 m (L1620a + L1610), as it was in the adjacent Room 3. Furthermore, additional features noted in the later phase of Room 3 also characterize Room 4’s latest phase. These include a circular installation (L1629) and a thin curvilinear mudbrick wall (W331). Among the finds worth noting ascribed to this floor are ostrich eggshell fragments.

- Room 5 (4.7×3.2 m) is situated at the centre of the building, surrounded by the other four rooms, and with an entryway to each. It is likely that this room served as an open courtyard. Its original floor (Phase VIIB, L1658b) abutted the stone thresholds of the surrounding rooms. This compact earth floor rested, like the building’s original floors, on the massive constructional fills whose upper part consisted of a fill layer mixed with mudbrick material. In the subsequent Phase VIIA, the floor level was raised (L3011). A circular installation, similar in character to those found in the adjacent rooms (above), was set close to the doorway leading to Room 4. Dozens of charred date pits were found in the ash layer in and around the installation (Fig. 8). These were radiocarbon-dated to the last quarter of the 10th century BCE (RTD 12207, see below).

In addition to the constructional fills that slope from the outer face of the foundation walls to create a ramp-shaped platform (above), some wall stubs and an oven excavated outside Building 3011 could be safely ascribed to Stratum VII. These were built atop the constructional fill, outside the building near its eastern wall (W340). These walls were built, without exception, from fieldstones similar to the substructure of Building 3011.

Analysis of the Stratum VII remains brought to light two significant architectural and stratigraphical observations. Firstly, the massive fills that create an artificial, platform-like foundation for Building 3011’s substructure testify to a considerable investment in workforce and to close acquaintance with large-scale building enterprises. To the best of our knowledge, this phenomenon, of using elevated built-up substructures that integrate massive constructional fills, has been noticed primarily in monumental public structures. Prominent examples are the four- chambers city gate at Megiddo (Ussishkin 1980) and the city gate and palace at Lachish (Ussishkin 2004). Indeed, Building 3011 does not integrate ashlar masonry in its substructure as did the other examples, and there is a clear tendency to use local raw materials; nonetheless, the exceptional endeavours characterizing its construction distinguish it from the common domestic structures of its type and allude to an organized initiative (below). Moreover, the construction of the immense fortress (Stratum VI) in Iron Age IIB occurred while some of Building 3011’s walls still stood to a considerable height. The archaeological evidence testifies to this building having been covered by the fortress’ constructional earthen fills, and these fills are the main reason for its excellent state of preservation, including some of the mudbrick superstructure walls. The only damage occurred to the walls that underlay Stratum VI’s foundations. This is best reflected in the Stratum-VI mudbrick installation L3137, which was built over the south-western side of Building 3011 (above). It is only the understanding that L3137, with its thin mud brick walls, was an underground facility (and therefore well-protected), while Building 3011’s inner walls formed part of its superstructure, that put these elements in their proper context. The stratigraphical and architectural relationships between these elements have important implications for evaluating the diachronic circumstances at the final phase of Building 3011 (and Stratum VII overall) and the construction of the overlying Stratum VI fortress. Accordingly, the scarcity of finds in general, and of pottery in particular, on its floors suggests that the inhabitants left the site by choice, taking their portable belongings and valuables. The immense fortress was constructed in the Iron Age IIB, long after Building 3011 had been abandoned, and a considerable chronological gap separates the two.

One of the primary objectives of this project is to establish high-resolution radiocarbon dating for the ‘En Hazeva Iron Age sequence. The first renewed excavation season at ‘En Hazeva, in 2023, allowed sampling of several secure and stratified contexts that provided high-precision radiocarbon dating for Building 3011. Setting the absolute chronology for ‘En Hazeva Building 3011 has far-reaching implications beyond the site’s occupation history, for it sheds light on the early Iron Age IIA settlement in the broader geographical and historical context.

5 When excavations were initiated at ‘En Hazeva, an arbitrary benchmark

for height-measurements was set in the field. To calculate real heights

(all below sea level) it is necessary to subtract c. 181.34 m

6 We would like to express our gratitude to Dr Nimrod Weiler, head of the

geoarchaeology branch at the IAA, for this information.

The earliest radiocarbon measurement obtained from ‘En Hazeva dates to 980–950 BCE and is associated with Stratum VIII. The three short-lived samples analyzed from this early context, which is stratigraphically located beneath the Stratum VII floors, point to a date in the Iron Age I for Stratum VIII. Thus far, we have only measured its latest upper boundary; our project aims for a broader architectural and stratigraphical exposure of Stratum VIII in the coming excavation season, which will undoubtedly allow us to study its character and set the absolute date of its foundation phase.

Building 3011 is a nearly complete architectural unit. Structures with this plan are common farther west, in the Negev Highlands, during the early Iron Age IIA (second half of the 10th century–first half of the 9th century BCE; see Finkelstein and Piasetzky, 2010; Herzog and Singer-Avitz 2004). Cohen and Yisrael, who excavated the building, suggested that it was part of a fortress. According to them, the early Iron Age IIA ‘fortress’ at ‘En Hazeva was part of a fortress network established in the 10th century BCE under royal initiative. They ascribed it to the United Monarchy during Solomon’s reign. The reasons behind establishing these ‘fortresses’ were twofold — to safeguard the roads crossing the central Negev, and to defend the kingdom’s southern border. Cohen and Yisrael (1995: 232; 1996: 91; and see below) attributed the destruction of the ‘fortresses’, ‘En Hazeva included, to Sheshonq’s military campaign in c. 926 BCE. However, the data retrieved during the 2023 excavations at ‘En Hazeva lead to a somewhat different interpretation of the fortress’ precise date and character.

Recent investigations into the early Iron Age IIA settlements in the southern arid regions of southern Israel and southern Jordan have provided significant insights that allow ‘En Hazeva Stratum VII to be set in a broader historical context. The ‘En Hazeva building parallels in plan several Negev-Highlands structures, the closest parallel being Har Hemet (Cohen and Cohen-Amin 2004: fig. 95:6). Like the Negev-Highlands structures, the ‘En Hazeva building included a pottery assemblage dated to the early Iron Age IIA, comprising two wares typical of the region — the wheel-made and the hand-made (i.e., ‘Negebite’) vessels (Cohen and Cohen-Amin 2004: 121–41, 6*–8*).7 Thus, based on its chronological setting, architectural plan and pottery assemblages, Building 3011 is associated with this early Iron Age IIA settlement wave (see below).

Although it is widely accepted that the Iron Age settlements in the Negev Highlands should all be dated to the early Iron Age IIA (Finkelstein 2014: 95; Martin et al. 2013), other fundamental issues remain in dispute. Debates are mainly concerned with the ‘who’ and ‘why’ questions, and relate primarily to the identity of the inhabitants, the reasons for their sudden establishment in this arid zone, and their abrupt demise. As these subjects have been widely discussed in literature without reaching a consensual view, it is futile to repeat the various approaches and sets of arguments here (for detailed discussions and references, see Aharoni 1967; Cohen 1979; Cohen and Cohen-Amin 2004; Eitam 1988; Faust 2006; Finkelstein 1984; Haiman 1994; Herzog 1983; Martin et al. 2013; Meshel 1994; and Rothenberg 1967).

Many of the studies have shown that the incentive for the Negev Highlands settlements was economic, since they chronologically coincide with the peak of copper production activity at Faynan (Bienkowski 2022: 128; Howland 2021: 75–79). Intensive research into the Arabah copper production centres, primarily the leading site of Khirbet en-Nahas, concludes that copper production lasted from the 12th to the 9th centuries BCE, with major mining activity occurring during the early Iron Age IIA (Ben-Yosef 2010; 2018; Ben-Yosef and Thomas 2023; Levy 2009). In this respect, the significance of ‘En Hazeva’s geographical proximity to the western end of Wadi Faynan cannot be overestimated. Situated close to the Wadis Faynan-Arabah meeting point, c. 20 kilometres, only, from the largest copper industry centre in the Levant, Khirbet en-Nahas (Ben-Yosef et al. 2014: 544 and figs 6.38–6.39; Levy et al. 2004: 867), ‘En Hazeva enjoyed a prime location in the copper traffic network associated with the two copper production regions, Timna in the southern Arabah Valley and the close-by Wadi Faynan. Since much of the Arabah copper had to cross to the Negev Highlands and proceed through the Beer-Sheba Valley to Gaza and the Mediterranean seaports, ‘En Hazeva was a strategic station along the commercial trade routes (Finkelstein 2014: 96; Singer-Avitz 1999: 10; 2008: 79). Its strategic location in this international copper trade network is further supported on petrographic grounds: preliminary results of the petrographic analyses, carried out on the pottery assemblage from Building 3011, testify that the hand-made ware included crushed copper slag as a tempering agent in the clay matrix (see below). This phenomenon aligns perfectly with studies establishing a connection between the Negev Highlands and the Arabah copper production centres (Howland 2021: 70–72 with extensive literature). Thus, the Negev Highlands phenomenon must be seen as a westward expansion of the activities centred in the Arabah Valley (Ben-Yosef 2023: 240; for the resemblance of the Area R building at Khirbet an-Nahas to some of the Negev Highlands structures, particularly that of Atar Haroa, see Bienkowski 2022: 126–27; Levy et al. 2014a: 231–32), with ‘En Hazeva located close to its hub. The absolute chronology of Building 3011 is harmoniously aligned with the peak recorded in the Arabah mining activity during the early Iron Age IIA. This economic prosperity was ‘En Hazeva’s raison d’être during this period.

To assess the overlapping activity intensities at ‘En Hazeva with the two bounding regions — Faynan on its east and the Negev Highlands settlements on its west — the radiocarbon dates from Khirbet en-Nahas and the Negev Highlands site of Atar Haroa were compared. One hundred and ten measurements were published from Khirbet en-Nahas (Levy et al. 2010; 2014a; see Tebes 2022: n. 4), and 16 from Atar Haroa (Boaretto et al. 2010). In principle, a site-specific stratigraphic model is the ideal approach to compare site chronologies. However, Atar Haroa has no discernible stratigraphy and is considered to be a single-layer site. In the case of Khirbet en-Nahas, the measured samples, including charred wood and charred seeds, are from stratigraphic layers in different areas, meaning that several chronologies would need to be built, which is beyond the scope of this study. Consequently, the Sum function available at the OxCal software was used to obtain a rough estimate of the dominant activity phases at these two sites and compare them with ‘En Hazeva. The individual probability distributions of all the samples measured at each site were combined into a single probability distribution plot (Fig. 17). These plots illustrate the timespan in which the sites show high values of occupation intensity. It should be taken into account that the resolution of these plots is dependent on the number of samples that the excavators decided to date, particularly at Khirbet en-Nahas. Nevertheless, they give the trends of occupation intensity. It should be noted that since most of the samples from Khirbet en-Nahas were of charcoal, there is a potential bias towards slightly older dates; however, sampling outer rings reduces the ‘old wood effect’. On the other hand, at the site of Atar Haroa, the samples were of short-lived material.

Figure 17

Figure 17Separate sums of all the probability distributions of the radiocarbon dates published from ‘En Hazeva, Khirbet en- Nahas and Atar Haroa. The number of samples used for each sum-plot appears next to the site names. The dark grey area in the ‘En Hazeva plot denotes the modelled date range of the site.

Ben-Ami et al. (2024)

These comparisons, between the three sites, allow for some conclusions to be drawn. It is clearly shown that ‘En Hazeva was already inhabited during Iron Age I (Stratum VIII), a time when substantial activity was noted at Khirbet en-Nahas. Building 3011, of the subsequent Stratum VII at ‘En Hazeva, is dated to the second half of the 10th century BCE, coinciding with increased activity at Khirbet en-Nahas. However, while the peak of the Faynan copper industry seems to be around the mid-9th century BCE, corresponding to the chronology of Atar Haroa, En Hazeva was abandoned slightly earlier, at the close of the 10th century BCE (see below).

The alterations recorded in Building 3011 distinguish ‘En Hazeva from most other Negev Highlands settlements, which, in general, lack complex stratigraphy, and mostly feature one short-span occupation phase (e.g., Eitam 1979: 128; Faust 2006: 139; Haiman 1994: 57–58; Meshel 1994: 58). Building 3011 provides a firsthand opportunity to pinpoint the dating of its establishment, duration and final use. The stratigraphically well-controlled radiocarbon dates of the sampled mudbricks, offer a range between 950 and 920 BCE, setting the mid-10th century BCE as the earliest possible date for its construction. The date pits sampled from the floors of the two phases put Phase VIIB at c. 940–910 BCE, while Phase VIIA is dated to c. 935–900 BCE. Hence, Building 3011 is dated exclusively within the early Iron Age IIA, occupying the second half of the 10th century BCE. These stratigraphical and chronological settings have significant implications for the historical circumstances in the southern arid regions, namely the Arabah Valley and the Negev Highlands, during the early Iron Age IIA.

Historically, the second half of the 10th century BCE is primarily known for Pharaoh Sheshonq I’s (biblical Shishak) Asiatic campaign to Canaan (for some uncertainty regarding the exact year of Sheshonq’s campaign, see Boaretto et al. 2010, n. 4; Fantalkin and Finkelstein 2006; Finkelstein 2002; c.f., Webster et al. 2023). The Sheshonq I list, on a wall of the temple of Amun at Karnak, boasting about his campaign into Canaan, includes a large group of toponyms widely accepted as being located in Canaan’s southern, arid zone (Kitchen 1986: 293–300, 432–47; 2003; Na’aman 1998 with further references). Archaeologically, this region is known to have experienced a sudden wave of short-term settlements during the early Iron Age IIA, and the two (i.e., the campaign and the settlement wave) demonstrate, to a certain extent, possible contemporaneity (Mazar 2007: 148). It is widely accepted that this settlement wave was economically motivated by the Arabah copper production and commerce system. Indeed, recent works focusing on the economic prosperity that evolved from the copper exploitation system of the early Iron Age IIA in the southern arid zones have already suggested a link between this settlement wave and Sheshonq’s enterprise in southern Canaan, stressing the Pharaoh’s intention to gain control over the copper production and trade system and improve its efficiency (Boaretto et al. 2010: 10; Fantalkin and Finkelstein 2006: 27– 28; Martin et al. 2013: 3790; c.f. Ben-Yosef 2010: 971–77; 2016: 193; 2023: 240, 247; for a scarab of this Pharaoh found at Wadi Fidan see Levy et al. 2014b). This interpretation is supported by a set of radiocarbon measurements from short-lived samples measured at Atar Haroa (Boaretto et al. 2010) and similar determinations from the nearby site of Nahal Boqer (Finkelstein 2014: 95, 98; Shahack-Gross et al. 2014: 107–08; 114–15) alluding to early Iron Age IIA dates in the 9th century BCE. In light of the new radiocarbon chronology of ‘En Hazeva, these 14C determinations invalidate the possibility that the settlements were destroyed by, or even abandoned as a result of, the Egyptian Pharaoh’s campaign (c.f., Cohen and Cohen-Amin 2004: 157; Cohen and Yisrael 1995: 232; 1996: 91; Faust 2006: 153; Mazar 1997: 160–61; 2007: 149–52; 2010: 31; Na’aman 1992: 83–85, 88; 1998).

‘En Hazeva provides a unique insight into this complex period due to its stratigraphical, architectural and chronological settings, and the fact that it was not destroyed but rather abandoned in the late 10th century BCE. If indeed the ultimate candidate for royal initiative in the Arabah Valley and the Negev Highlands during the early Iron Age IIA is Pharaoh Sheshonq I, then Building 3011 resonates with this scenario. As noted earlier, Building 3011 was founded on a massive elevated built-up substructure, a fact that attests to a significant investment in labour and to knowledge of complex construction techniques. Initiatives on such a scale must have been carried out by an authority with an established tradition of large-scale construction operations, which, therefore, makes the local desert inhabitants less likely candidates (for a different view, see the ‘architectural bias’ in Ben-Yosef 2010: 988; 2019; 2020; 2023; Ben-Yosef and Thomas 2023). Indeed, the coarse hand-made pottery found in the building, and understood by many scholars as a product of the desert nomads, suggests that the building has pastoral nomadic traits, possibly of the local desert population (Faust 2006: 149; Herzog 1984: 26; Martin and Finkelstein 2013: 12; Meshel 1994: 59; Tebes 2006). Nonetheless, this does not mean that this section of the population was, necessarily, responsible for the planning and execution of the enterprise. Any attempt to claim that groups with nomadic back ground were involved in the construction of the site, or to consider them among its dwellers, solely on the basis of the hand-made ware in the pottery assemblage, would, at best, be mere speculation. Hand-made ware has been accepted as a distinct regional phenomenon, confined almost exclusively to the desert regions of the Negev Highlands and Wadi Arabah. Recently, however, this view has changed, and it is now deemed to have been transported into these regions from Wadi Faynan via the movement of people (Bienkowski 2022: 127; Martin et al. 2013; Martin and Finkelstein 2013; Yahalom-Mack et.al 2015). Thus, the hand-made vessels cannot be considered a firm indicator of either the participation of the desert communities in the construction of Building 3011, or of their actual presence there (see Bernick-Greenberg 2007: 210); it can only allude to a certain degree of contact between the building’s dwellers and this nomadic element.

7 Discussion of the pottery retrieved from Building 3011 is beyond the scope of this paper. A large-scale petrographic analysis and typological study of this assemblage is currently in process and will be published else where. We take this opportunity to express our gratitude to Dr Anat Cohen-Weinberger of the IAA for her valuable insights into the preliminary results of the hand-made pottery from the building.

The new high-resolution dates from stratified contexts enabled an absolute chronological setting for the early Iron Age settlement at ‘En Hazeva. The above analysis testifies to the special status that should be assigned to ‘En Hazeva during the early Iron Age IIA; a status that derived directly from its role in the Arabah copper trade network. Due to its prime location at the crossing of the Arabah (see also Ben-Yosef et al. 2014: figs 6.38–6.39), ‘En Hazeva became a strategic waystation along the commercial network transport ing the Arabah Valley copper to the Mediterranean seaports, with the residents of ‘En Hazeva working under the auspices of the authorities and holding administrative positions primarily relating to Arabah copper production and commerce (see already Mazar 2007: 151). Given that the aim of Sheshonq’s campaign was to control the Faynan copper exploitation and trade system, and to redirect the copper trade from the eastern highway to the coastal plain and Egypt (e.g., Finkelstein 2014: 96), Egypt becomes the ‘usual suspect’ for initiating the construction of Building 3011 at ‘En Hazeva.

The site’s abandonment is in keeping with the abandonment of many other sites in the region at about the same time and should, therefore, be viewed against this more comprehensive background. It was a gradual process, tightly associated with the gradual decrease in Arabah copper production towards the late 9th century BCE. While the end of this process is due to the revival of the import of Cypriot copper to the Levant in the late Iron Age IIA, the abandonment of Building 3011 at ‘En Hazeva could have resulted from Egypt losing its firm grasp over the region following Sheshonq I’s sudden death. During the time of Sheshonq I’s successor, Osorkon I, Egypt kept its foreign affairs policy unchanged, maintaining its alliance with the commercial port of Byblos. But it was not too long before internal instability struck, preventing the Egyptians from establishing a colonial system in the southern Levant during the Third Intermediate period. These troubles culminated during the reign of Osorkon II (whose cartouches were found on a large alabaster vessel at Samaria), when Upper Egypt and the Thebaid sought greater independence, challenging Osorkon II’s effective, absolute rule, and thus rendering any foreign adventure beyond Egypt’s capability (Kitchen 1986: 324). It seems, however, that the early years of the 22nd dynasty were nothing more than a ‘short-period revival of Egypt as a key player in the Levant’ (Finkelstein and Piasetzky 2008: 89). If the Egyptian interest in controlling the southern Levantine copper trade network was the raison d’être for ‘En Hazeva Building 3011, its loss of influence in the region eventually led to the building’s doom.

Building 3011 stood abandoned for nearly a couple of centuries showing no trace of later occupation activity. The immense fortress established at ‘En Hazeva over the abandoned building (Stratum VI), opens a new chapter in the site’s history, dating to the Iron Age IIB–C. The fortress’ massive constructional fills buried Building 3011 entirely, and were the main reason for the latter’s excellent preservation, including its mudbrick superstructure walls.

The work at 'En Haseva has now distinguished six occupation levels (from the latest to the earliest):

- Late Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods (sixth-seventh centuries CE)

- Late Roman Period (third-fourth centuries CE)

- Nabatean and Early Roman Periods (first-second centuries CE)

- Iron Age (seventh-sixth centuries BCE)

- Iron Age (ninth-eighth centuries BCE)

- Iron Age (tenth century BCE)

As previously reported (Cohen 1994:208), only the eastern side of the Stratum 4 fortress (ca. 36 m long) with two projecting towers (ca. 14 m apart) was cleared. The southeastern tower (11xl m; its walls ca. 1.5 m in width) was completely cleared. One side of the northeastern tower was built atop an earlier Stratum 5 casemate wall, while the other side lay beneath Late Roman and Nabatean period remains (Strata 2-3).

The ceramic assemblage from this stratum belongs to the seventh-sixth centuries BCE. On this basis, we suggest that the Stratum 4 fortress was constructed during the reign of Josiah (639-609 BCE) and destroyed at about the same time as the First Temple in Jerusalem (586 BCE; Cohen 1994:208).

Though the last three seasons of excavation uncovered no major architectural remains that could clarify the plan of this structure, the area near the northeastern tower offered a very important find in 1994: a circular, polished seal. Made of choice stone, the hemispherical seal measures 22 mm in diam- eter and is 15 mm thick. Two standing, apparently bearded, male figures are skillfully and delicately engraved on this seal. They face one another and are dressed in long gowns. Between them is a tall horned altar. The figure on the left stands with one hand raised heavenward in a gesture of blessing, while the figure on the right stands with one hand raised in a gesture of offering. Above the figures are two lines of engraved Edomite script (deciphered by Prof. Joseph Naveh): lmikt bn whzm ("belonging to mikt son of whzm"). This seal may have belonged to one of the priests serving in the shrine uncovered at 'En Haseva (see below). A seal discovered at Horvat Qitmit depicts a similar figure (Beit-Arieh 1991:99; Beit-Arieh and Beck 1987:19).

The group of cult vessels, described below with the Edomite Shrine in which they were found, also belongs to this time period.

Remains of an earlier Iron Age fortress (ninth-eighth centuries BCE) were first discovered in 1987 in well-recorded stratigraphy (Cohen 1994). The 1992-1995 seasons were dedicated principally to exposing the plan and outline of this fortress.

The large Stratum 5 fortress (100x100 m) was surrounded by an inset-offset casemate wall with three corner towers projecting approximately 3 m from the wall. Casemate-rooms (21 m in width) appeared on all sides of the fortress, but no tower was found in the northeastern corner; builders had intentionally filled most of the rooms with earth. Their walls exhibit various states of preservation-from a height of ca. 4.5 m to nothing more than foundations.4

Excavations also exposed casemate-rooms on either side of the beautifully preserved, four-chambered gate (Cohen 1994:210). Two of these rooms yielded a pottery assemblage which included a number of complete ceramic and stone vessels characteristic of the ninth-eighth centuries BCE: a cooking-pot, juglets, a storage jar, and an Achzib-type jug (Phoenician red-slipped ware). Alongside this collection was a stone bowl placed on a stone stand; in the bowl was a pottery bowl that contained a clay lamp. Nearby was a round stone massebah(?).

The last three years of excavation saw to the final clearing of the large gate-complex (ca. 15.0x12.8 m). In addition to the four chambers and piers found inside the gate (Cohen 1994:210), a long open corridor/courtyard (13.6-14.0 m wide) was found immediately outside, probably leading to the outer gate of the fortress. The walls of this corridor/courtyard were 2 m wide and the length of the eastern wall was 25 m. There was a structure attached to the 18 m western wall. The structure (9x4 m), a bastion or rooms related to the outer gate, contained two adjacent chambers. In addition to its resemblance to the fortress- gate at Tell el-Kheleifeh (Glueck 1939:9,13-14, fig. 1; Pratico 1985; 1986), this fortress-gate is also very similar to-although better preserved than-the gatehouse uncovered at Tel Jezreel (Ussishkin and Woodhead 1994:13-24) .

Excavations also uncovered a storeroom complex (magzines) and granaries in Stratum 5 stratigraphy (Cohen 1994:208-212). The storeroom complex consisted of three parallel long rooms. They were located south of the gate and adjacent to the inner southwestern corner of the gate complex (Cohen 1994:208). The rooms were 1.5-2.6 m wide and 172 m long, with walls 1.0 1.3 m thick, most preserved to a height of 3 m. No floors were found and, like the casemate-rooms, the storerooms were filled with earth. A long parallel corridor (ca. 3.5 m in width, its walls 1.0-1.2 m wide) separated this complex from whatever structures may have stood to its north. Structures of this type, considered to be storehouses (Currid 1992:102-7; Shiloh 1970:184), stables (Holladay 1986), barracks (Fritz 1977), or market places (Herr 1988), are known at various important sites of the Iron Age II, like Beersheva (Aharoni 1973:14-15; Herzog 1973) and Horvat Tov (Cohen 1985; 1988/89).

Two granaries emerged near the magazines. The largest, east of the storeroom unit, was ca. 3.5 m in diameter, built of undressed stones, and preserved to the height of ca. 0.5 m. Its plastered floor offered burnt wheat and barley remains. The granary also contained two com- plete vessels: a large decorated flask and a jug. The outer wall of the second granary, which stood to the north of the long storeroom complex and was built above Stratum 6 wall remains, was constructed of clay bricks and preserved to the height of approximately 1.2 m. Its floor was paved with crude silex (flint) stones. Since remains similar to those found in the first granary were not uncovered in this structure, we cannot be sure that it was, in fact, a granary.

Stratum 6 wall remains, was constructed of clay bricks and preserved to the height of approximately 1.2 m. Its floor was paved with crude silex (flint) stones. Since remains similar to those found in the first granary were not uncovered in this structure, we cannot be sure that it was, in fact, a granary. The immense size of the Stratum 5 fortress (1ha) suggests that 'En Haseva should be considered a fortified city and not merely a fortress. Its groundplan has several features in common with that of the fortress uncovered at Tel Jezreel (Ussishkin and Woodhead 1994), thought to be the central military base in the Israelite Kingdom (Ussishkin and Woodhead 1994:47).5 Furthermore, it is not surprising that its first phase resembles the plan of the fortress at Tell el-Kheleifeh (Stratum II) (Glueck 1939; 1940:12-13; Pratico 1985; 1986) since they were all most likely built during the same time period.

4 The existence of robber trenches, a common phenomenon at multi-period sites, indicates that these walls were destroyed deliberately rather than by natural forces. The trenches were dug along walls that were then dismantled so their stones could be used in later construction activities. At (En Haseva, this looting seems to have been carried out principally by the builders of the Roman fortress.

Among the earliest remains uncovered at 'En Haseva are those of a rectangular structure (ca. 13.0x11.5 m) that may belong to the tenth century BCE. Uncovered beneath the piers of the fortress gate and to its west and south, the walls of the structure were built of silex. The impressive southwestern corner, built of large silex blocks, is preserved to the height of more than a meter. It appears to be a fortress, similar in plan to those found at several Iron Age sites in the central Negev (Cohen 1995).

Diggers retrieved a complete handmade Negbite cooking-pot, made of rather coarse ware and exhibiting very crude manufacturing, from the southeastern room of this fortress. Negbite ware has been found at Tell el-Kheleifeh (Glueck 1939:13f; 1940:17f; Pratico 1985:23f) and in all three fortresses uncovered at Kadesh-Barnea (Cohen 1981; 1983a), dating from the tenth to the beginning of the sixth centuries BCE

... There are several good candidates for the builders of the Stratum 5 fortress. The results of the most recent excavations at the site have contributed to a change in our thinking concerning the initiator of this construction project. We now believe that it may have been built in the ninth-eighth centuries BCE rather than a century later as previously suggested. A look at the relations between Judea and Edom as they are described in the Bible is necessary to understand who the possible architects were and how we have arrived at our choice of the most likely candidate. cEn Haseva Stratum 5 may represent a military base that was enlarged as necessitated by the political climate of the times. The initial early phase, the gate complex, may have been constructed by Jehoshaphat (867-846 BCE) when "there was no king in Edom, a deputy was king" (1Kgs 22:48). 1 Kgs reports that, in an unsuccessful attempt to repeat Solomon's achievements, "Jehoshaphat made ships of Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold, but they did not go, for the ships were wrecked at Ezion-geber" (1 Kgs 22:49; Bartlett 1989:115-6). This attribution would also find support in 2 Chr 17:2: 'And he [Jehoshaphat] placed forces in all the fortified cities of Judah, and set garrisons in the land of Judah." Later, perhaps at the end of his reign, the fortress was enlarged to accommodate the Israelite/Judean retaliatory campaign against Mesha, king of Moab (mid-ninth century BCE; 2 Kgs 3:4-15), who mentions his rebellion against the king of Israel in his Stele (Bartlett 1989:116-22; Dearman 1989). The large Stratum 5 fortress may have served as the deployment center for this invasion. This would not only lend credence to the biblical statement that Jehoshaphat built fortresses and storage cities in Judah (2 Chr 17:12), but would also serve to strengthen the identification of the magazines at CEn Haseva as, in fact, a storeroom complex and not a building of some other kind (e.g., stables, barracks, or market places). The similarity in plan between the Stratum 5 fortress at CEn Haseva and the Iron Age fortifications at Tel Jezreel (Ussishkin and Woodhead 1994) suggests that they may date to approximately the same time, i.e., the ninth century BCE or some time thereafter.