Megiddo

Left

LeftTel Megiddo from the NorthWest

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com

Right

Tel Megiddo from the Southeast

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Drone photos taken by Jefferson Williams on 27 April 2023

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

Megiddo

Hebrew

מגידו

Tel Megiddo

Hebrew

תל מגידו

Har Məgīddō

Hebrew

הַר מְגִדּוֹ

Magiddu, Magaddu

Akkadian

Maketi, Makitu, Makedo

Egyptian

Magidda, Makida

Canaanite-influenced Akkadian used in the Amarna tablets

Megiddo

Greek

Μεγιδδώ

Mageddou

Greek

Μαγεδδών

Megiddó, Mageddón

Greek in the Septuagint

Mageddo

Latin in the Vulgate

Armagedōn

Late Latin

Armageddon

New Testament Book of Revelation

Harmagedōn

Greek

Ἁρμαγεδών

Tell el-Qedah

Arabic

تل القدح

Tell el-Mutesellim

Arabic

مجیدو

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

Kefar ʿUthnai

Hebrew

כפר עותנאי

Legio

Latin

Caporcotani

Latin in the Tabula Peutingeriana Map

Legionum ?

Latin

al-Lajjun

Arabic

اللجّون

Transliterated Name

Source

Name

Qina, Kina, Qinnah

Egyptian

"Waters of Megiddo"

in Song of Deborah

Qyni ?

Hebrew

קיני

Nahal Qeni ?

Hebrew

נַחַל קֵינִי

- from Chat GPT 5, 18 September 2025

- sources: Tel Megiddo – Wikipedia, Armageddon – Wikipedia, Book of Revelation – Wikipedia

The site preserves over twenty layers of occupation, revealing monumental architecture such as temples, palaces, gates, water systems, and administrative complexes. It was a major Canaanite city-state during the Bronze Age and later a fortified stronghold under Israelite rule, mentioned in Egyptian, Assyrian, and Biblical sources alike.

Due to its strategic location, Megiddo was the site of several influential battles and as a result has gained global fame for the metaphor it spawned – Armageddon. In the Book of Revelation, the final book of the New Testament, Armageddon (which is linguistically derived from Megiddo) is prophesied as the place where the final battle of human history will be fought.

The mound has been the focus of numerous archaeological expeditions since the early 20th century, including the University of Chicago’s pioneering work in the 1920s–30s, Yigael Yadin’s excavations in the 1960s, and more recent multinational campaigns. These investigations have provided a critical framework for understanding urbanism, state formation, and conflict in the ancient Near East.

The identification of biblical Megiddo with el-Lejjun, about 1 km (0.6 mi.) south of Tel Megiddo (Tell el-Mutesellim, map reference 1675.2212) was suggested as early as the fourteenth century by Estori ha-Pari and in the nineteenth century by E. Robinson. Tel Megiddo is one of the most important city mounds in Israel. It rises 40 to 60 m above the surrounding plain and covers an area of about 15 a. This area was enlarged in various periods by a lower city. The position of the mound at the point where Nahal 'Iron (Wadi 'Ara) enters the Jezreel Valley gave it strategic control in ancient times over the international Via Maris, which crossed from the Sharon Plain into the Valley of Jezreel by way of the 'Iron Valley. This position, astride the most important of the country's roads, made Megiddo the scene of major battles from earliest times through our own.

The excavations conducted on the mound have shown that, in the Early and Middle Bronze ages, Megiddo was already a fortified city of major importance, despite the fact that it is not mentioned in historical sources until the fifteenth century BCE. At that time it appeared in inscriptions of Thutmose III. The annals of this pharaoh record that Megiddo led a confederation of rebel Canaanite cities that, together with Kadesh on the Orontes, attempted to overthrow Egyptian rule in Canaan and Syria. The Egyptian army and Canaanite chariotry fought the decisive battle of this rebellion at the Qinnah Brook (Wadi Lejjun), near Megiddo. This is the earliest military engagement whose details are preserved. After thoroughly routing the Canaanite force in the field, Pharaoh captured a rich booty, including 924 chariots. According to the Jebel Barkal stela, the siege of the city lasted seven months. During this time, the Egyptian army harvested the city's fields and took 207,300 kor of wheat (apart from what the soldiers kept for themselves).

After his great victory, Thutmose turned Megiddo into the major Egyptian base in the Jezreel Valley. Evidence of its importance and military strength is found in three documents: In one of the Taanach letters, in which the king of Taanach was ordered to send men and tribute to Megiddo; in a description of Amenotep II's second campaign (c. 1430 BCE), which ended "in the vicinity of Megiddo"; and in one of the el-Amarna letters (EA 244), in which the king of Megiddo asks Pharaoh to return to that city the Egyptian garrison that had been stationed there.

Megiddo is mentioned in the city lists of Thutmose III and Seti I - in Thutmose's list of Canaanite emissaries (Leningrad Papyrus 1116-A). Among the el-Amarna letters are six sent by King Biridiya (an Indo-Aryan name) of Megiddo to the Egyptian pharaoh. These letters show that Megiddo was one of the mightiest cities in the Jezreel Valley, and that its major rivals were Shechem and Acco. In one of his letters, Biridiya mentions that he brought corvee workers from Yapu (Japhia ?) to plow the fields of Shunem (a city that, according to another letter, had been previously destroyed). In the Papyrus Anastasi I, dated to the reign of Ramses II, Megiddo is mentioned in a detailed description of the road from the city down to the Coastal Plain, following the course of the 'Iron Brook'.

During the period of the Judges, Megiddo was one of the major Canaanite cities in the Jezreel Valley. It is mentioned in the Song of Deborah: "The kings came, they fought; then fought the kings of Canaan, at Taanach, by the waters of Megiddo" (Jg. 5:19; and cf. Jos. 12:21). It is also listed among the Canaanite cities not conquered by the tribe of Manasseh (Jos. 17: 11-13; Jg. 1:27-28;and cf. l Chr. 7:29). How or when Megiddo fell into lsraelite hands is not known, but it appears during the period of the United Monarchy, together with Hazor and Gezer, among the Israelite cities fortified by Solomon (I Kg. 9:15). It is also mentioned as one of the cities in Solomon's fifth administrative district (I Kg. 4: 12).

Thereafter, there are few written references to Megiddo, but it is clear that it continued to be one of the major northern cities. Pharaoh Shishak conquered it during his campaign against Israel in the fifth year of Rehoboam's reign (about 925 BCE), and it is mentioned in the story of the death of Ahaziah king of Judah, during Jehu's revolt (2 Kg. 9:27). In 733-732 BCE, Tiglath-pileser III, king of Assyria, conquered the northern part of lsrael and made Megiddo the capital of the Assyrian province of Magiddu. This province included the Jezreel Valley and the Galilee (the district "of the nations" in Isaiah 9:1). The fact that Josiah's battle against Pharaoh Necho [II] in 609 BCE was fought at Megiddo (2 Kg. 23:29; 2 Chr. 35:22) indicates that, at least for a short time, the city was under Judean rule. This was in all likelihood the last period of prosperity in Megiddo's long history because, after Josiah's defeat, nothing more is heard of Megiddo. The strategic role of guarding the 'Iron Pass' was assumed by Kefar 'Othnai, a small village that became the base of the Sixth Roman Legion after the Bar-Kokhba Revolt. The village became known as Legio (in Arabic: el-Lejjun). Megiddo's military importance and long history as an international battleground were aptly reflected in the Apocalypse of John [aka Revelations] (Rev. 16:12 ff.), in which Armageddon ('Ἁρμαγεδών, the Mount of Megiddo) is designated as the site where, at the end of days, all the kings of the world will fight the ultimate battle.

The excavations conducted at Megiddo were very large and extensive. From 1903 to 1905, the mound was excavated by G. Schumacher on behalf of the German Society for Oriental Research. Schumacher dug a trench 20 to 25m wide running north-south along the entire length of the mound.In part of the trench he dug down to the Middle Bronze Age II occupation levels, reaching bedrock in a small section. In his reports, Schumacher described six building levels from the Middle Bronze Age II to the Iron Age. Two large buildings discovered in the trench, the Mittelburg and the Nordburg (Schumacher's terms), were both built during the Middle Bronze Age II and continued in use, with some repairs and additions, until the Late Bronze Age. Beneath these buildings were two unique tombs with false-arch roofs that some scholars considered were tombs of the Megiddo royal dynasty in the Late Bronze Age. At the south end of the trench, Schumacher uncovered part of a large building dating to the Israelite period (Iron Age), which he called the Palast, or palace-building 1723 of the Chicago expedition (see below). Schumacher also made several soundings in different parts of the mound and on the slopes along the city walls. The sections of walls that he excavated belonged mostly to the Israelite city, but some were earlier. Near the east end of the mound, Schumacher excavated a large Israelite building he thought was a sanctuary because of its stone pillars (identified by him as the stelae of a sanctuary). He called the building the Tempelburg. Similar stone pillars, however, have been found in ordinary houses from the Israelite period. A proto-Aeolic capital, reused as a building stone, was discovered in the wall of this building. It was the first such capital found in the country. The finds of the excavation were published by C. Watzinger in a separate volume. Especially noteworthy are two seals inscribed "(belonging) to Shema' servant of Jeroboam" and "(belonging) to Asaph," which were found in the ruins of the "palace," and a stone incense burner with painted decoration found in the upper (sixth) stratum at the south end of the trench.

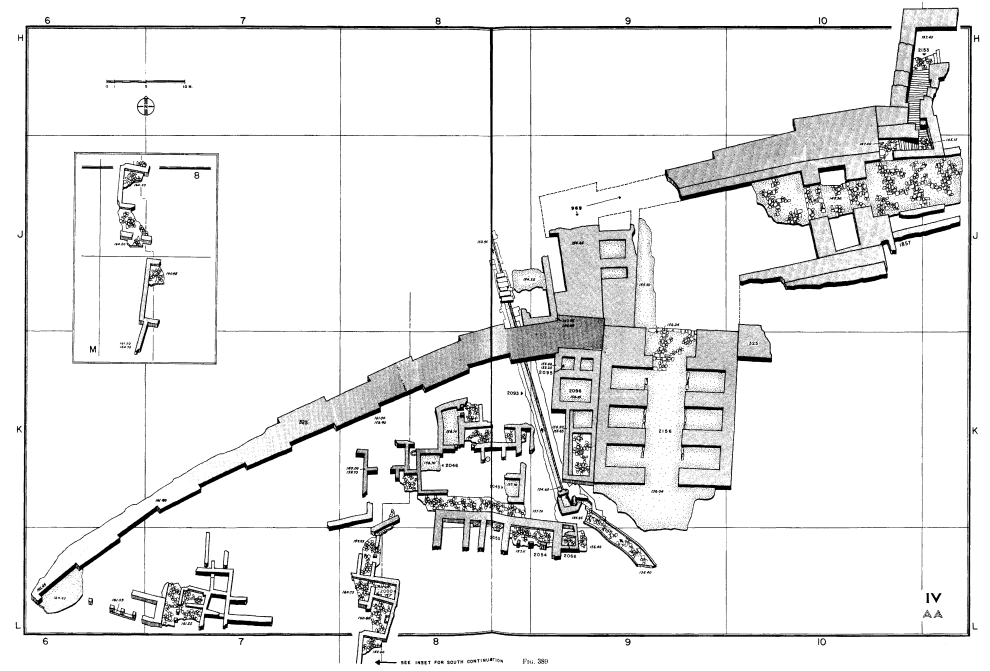

In 1925, excavations at Megiddo were renewed by the Oriental Institute of Chicago, on the initiative of J. H. Breasted, and continued until l939, under the successive direction of C. S. Fisher, P. L. 0. Guy, and G. Loud. The original goal of the expedition was to excavate the entire mound, removing stratum after stratum, from top to bottom. This ambitious project was carried out for the first four strata (Persian period to ninth century BCE). The finds from the four strata and from part of the excavation of the fifth stratum were published by R. Lamon and G. M. Shipton.

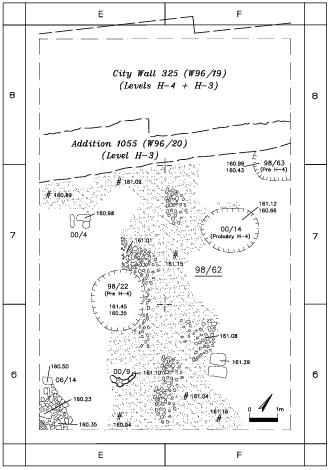

During the final four years of the expedition, it became evident that the work could not be continued on such a grand scale, and the excavations were thereafter concentrated in two main areas: area AA in the north, in the vicinity of the city gate, where the excavators reached stratum XIII (Middle Bronze Age IIA), and area BB, in the east, the area of the temples, where bedrock was reached (stratum XX). The expedition reached stratum VI in two additional areas, area CC in the south (the area of Schumacher's Palast) and area DD in the northeast, situated between areas AA and BB.

The outbreak of World War II put an unexpected end to the excavations. The results have appeared only in a "Catalogue Publication of floor plans and finds" - to quote Loud's definition.

Because the east slope of the mound was to be used as a dump for the excavated earth, the expedition first undertook to clear and examine this area. Its investigation revealed many burial caves from different periods. They contained rich and varied finds that provided valuable additions to the discoveries made on the mound. The finds from the burial caves were published separately by Guy and R. M. Engberg.

The east slope also yielded remains from seven levels from Early Bronze Age settlements (the excavators previously assumed that the earliest settlement level dated to the Chalcolithic period). These levels, called stages I-VII, were published separately by Engberg.

One of the most significant discoveries was the city's monumental water tunnel. It was fully excavated and made the subject of a separate study by R. Lamon. The excavators suggested that the tunnel had been dug in the twelfth century BCE. Later excavations by Y. Yadin showed that it was probably built in the Iron Age (see below). In another, separate study, H. G. May assembled the cult finds from the various levels. The magnificent hoard of ivories (see below) from the Late Bronze Age was published by Loud.

In 1960, 1961, 1966, 1967, and 1971, an expedition headed by Y. Yadin excavated Megiddo on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In the course of reexamining Iron Age strata VIA-III, this expedition was able to distinguish the buildings already uncovered in the previous excavations, such as the northern stable compound, the gate area, and the subterranean water system. Extensive excavations were also carried out in area B of the Yadin expedition, east of area DD and north of area BB of the Chicago expedition. A more limited probe was done near gallery 629, gate 2153, and a trench in the lower terrace of the mound.

The renewed excavations at Megiddo have been undertaken under the auspices of Tel Aviv University, with Pennsylvania State University as the senior American partner. Consortium institutions are George Washington University, Loyola Marymount University, the University of Southern California, Vanderbilt University, the University of Bern, and Rostock University. The directors of the expedition are I. Finkelstein and D. Ussishkin, who lead the excavation; and B. Halpern, who heads the academic program and acts as the coordinator of the consortium. The expedition is endorsed by the Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority, which maintains the site as a national park, and the Israel Exploration Society.

The renewed excavations, aiming at a long-term, systematic study of Tel Megiddo and its history, commenced in two short seasons in 1992 and 1993. The first full season took place in 1994, and the expedition has operated in the field every other year since. Eight areas have thus far been chosen for excavation. They include two trenches in the upper periphery of the site—one to the northwest and the other to the southeast; one trench in the lower mound; two areas aimed at further investigating remains uncovered in the previous excavations; and three areas in conjunction with development plans of the Nature and National Parks Protection Authority. These excavation areas consist of the following:

- Area F: Located in the lower terrace of the mound, with remains of the Middle Bronze Age earthen embankment, Late Bronze Age I and Iron Age I domestic houses, and a Late Bronze Age II monumental building.

- Area G: The Late Bronze Age city gate excavated by the University of Chicago team in their area AA.

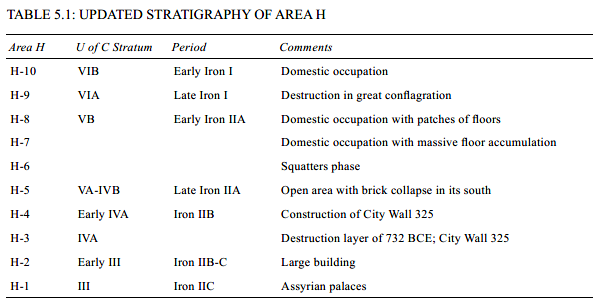

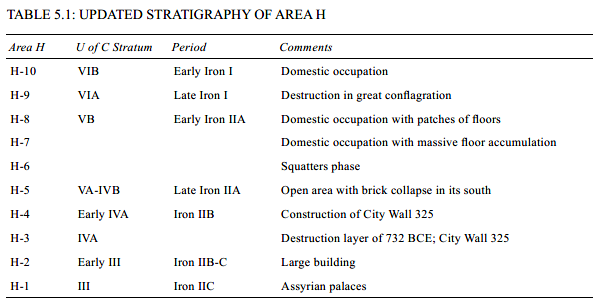

- Area H: A sectional trench on the northwestern edge of the mound; investigation concentrated on the relationship between the Assyrian palaces excavated in the 1920s, the destruction debris of stratum IVA, and Iron Age II stratigraphy.

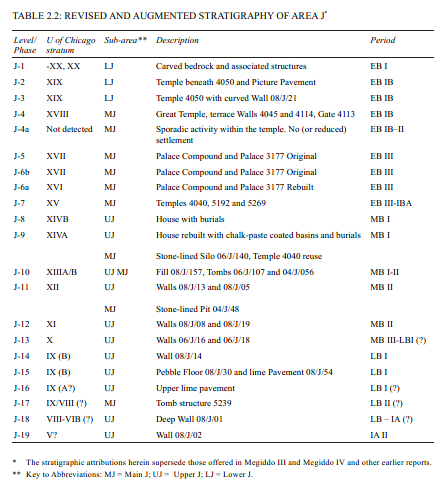

- Area J: A renewed study of the Early Bronze Age temples, uncovered by the University of Chicago excavations in area BB.

- Area K: A sectional trench in the southeastern edge of the mound, with remains of Iron Age I–II domestic buildings.

- Area L: A renewed study of palace 6000 partly excavated by Y. Yadin, and the “northern stables” partially unearthed by the University of Chicago team.

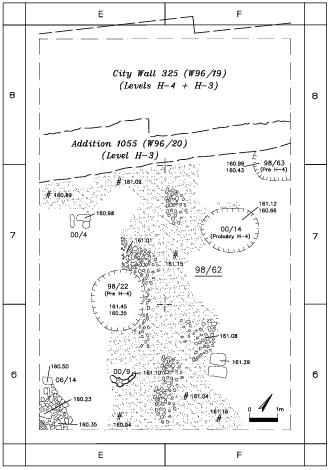

- Area M: Located in the center of the mound, in and around the great north–south trench dug by G. Schumacher in the early twentieth century. Excavation was devoted to the clarification of the date and nature of the Nordburg and the monumental chamber tomb f uncovered by Schumacher, and to the exposure of an elaborate building of stratum VI to the east of Schumacher’s trench.

- Area N: Located at the northwestern foot of the mound and containing Middle Bronze Age III/Late Bronze Age I remains.

- Fig. 31.1 - Faults and Epicenters near Meggiddo

from Marco et. al. (2006)

Fig. 31.1

Fig. 31.1

Location of faults near Megiddo and recent earthquake epicentres in the vicinity of the Carmel Fault. Earthquake data from the Geophysical Institute of Israel

- Y - Yoqne'am

- M - Megiddo

- T - Ta'anach

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 25 Late Iron I destructions

in the southern Levant from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 25

Fig. 25

Late Iron I destructions in the southern Levant. A few of these sites, e.g., Shiloh, were devastated slightly earlier, in the middle Iron I, while other sites, e.g., Khirbet Qeiyafa and Tel Miqne/Ekron (Stratum IV), were destroyed a bit later, in the Iron I/II transition

Kleiman et al. (2023)

- Annotated Aerial View of

Tel Megiddo from biblewalks.com

- Annotated Aerial View of

Tel Megiddo from the north from BibleWalks.com

- Unannotated Aerial View of

Tel Megiddo from the north from BibleWalks.com

- Aerial View of Tel Megiddo

from wikipedia

Tel Megiddo with archaeological remains from the Bronze and Iron Ages

Tel Megiddo with archaeological remains from the Bronze and Iron Ages

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

AVRAM GRAICER - wikipedia - CC by SA 3.0 - Aerial View of Tel Megiddo

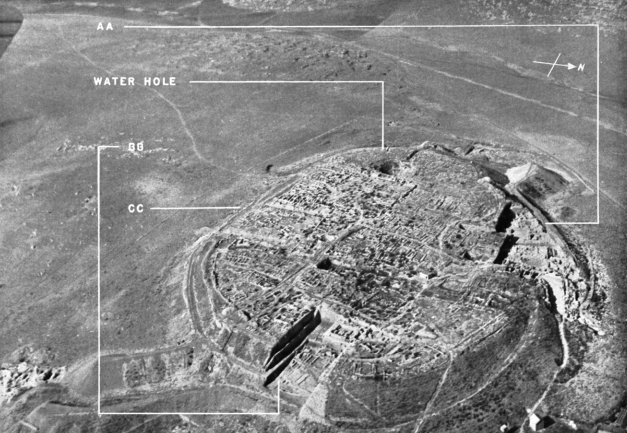

in 1948 from Loud (1948)

Air View of The Mound

Air View of The Mound

Loud (1948) - Fig. 2 Annotated Aerial View

of Tel Megiddo and Tel Megiddo East from Sapir-Hen et al. (2022)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The dual site of Megiddo and Tel Megiddo East in the Early Bronze Age Ib.

(Illustration by M. J. Adams)

Sapir-Hen et al. (2022) - Megiddo in Google Earth

- Megiddo on govmap.gov.il

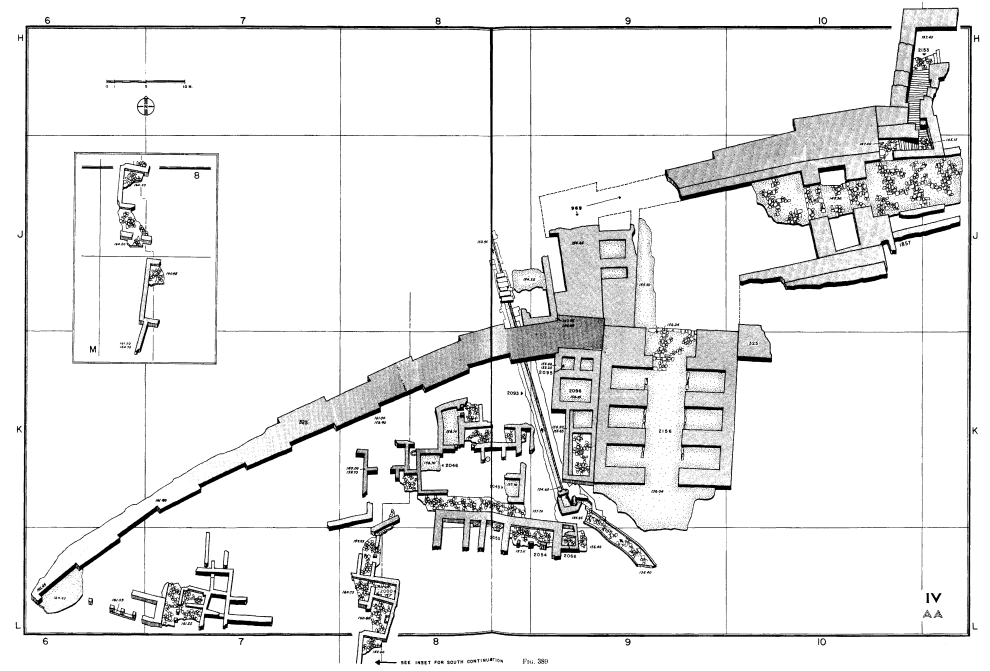

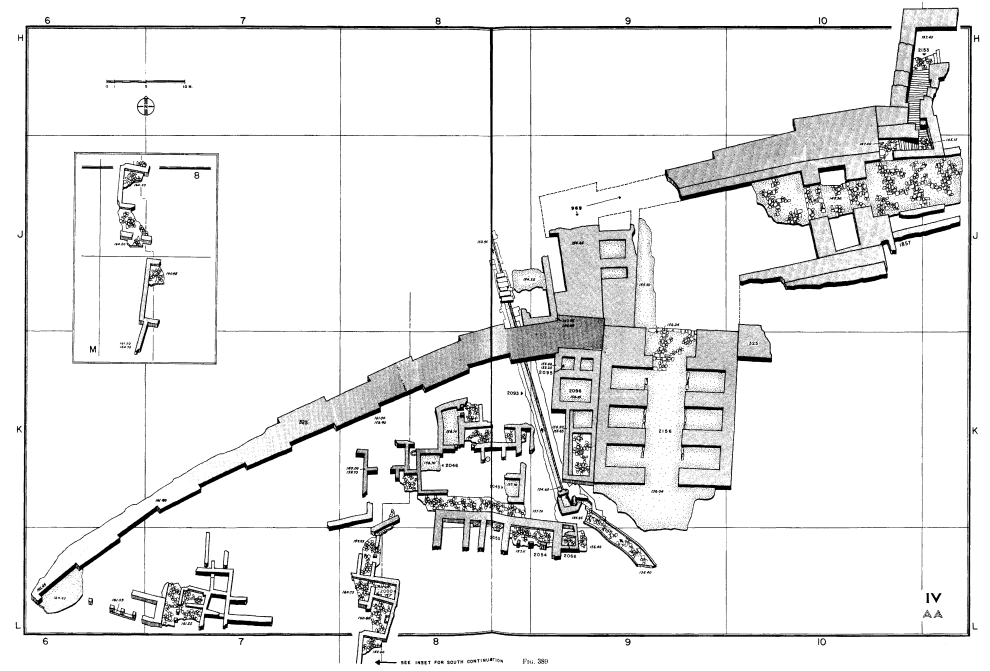

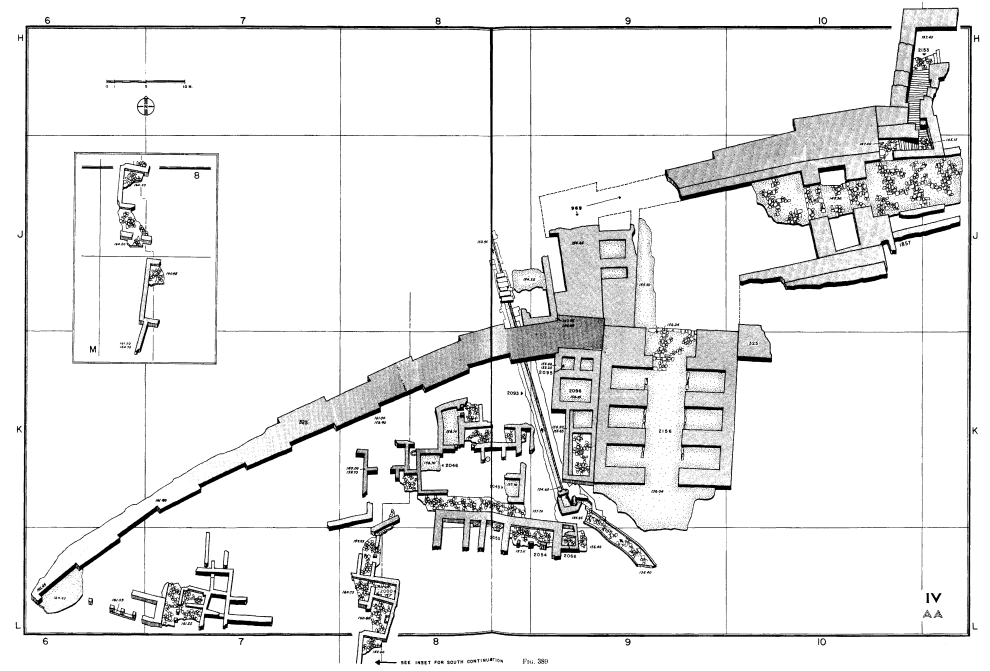

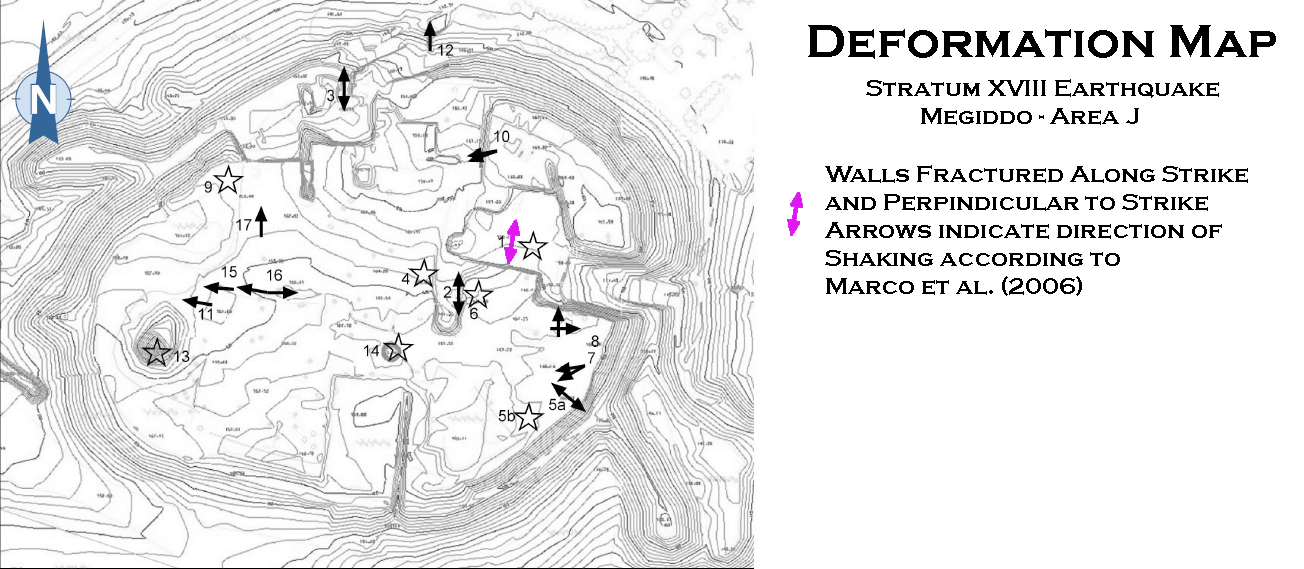

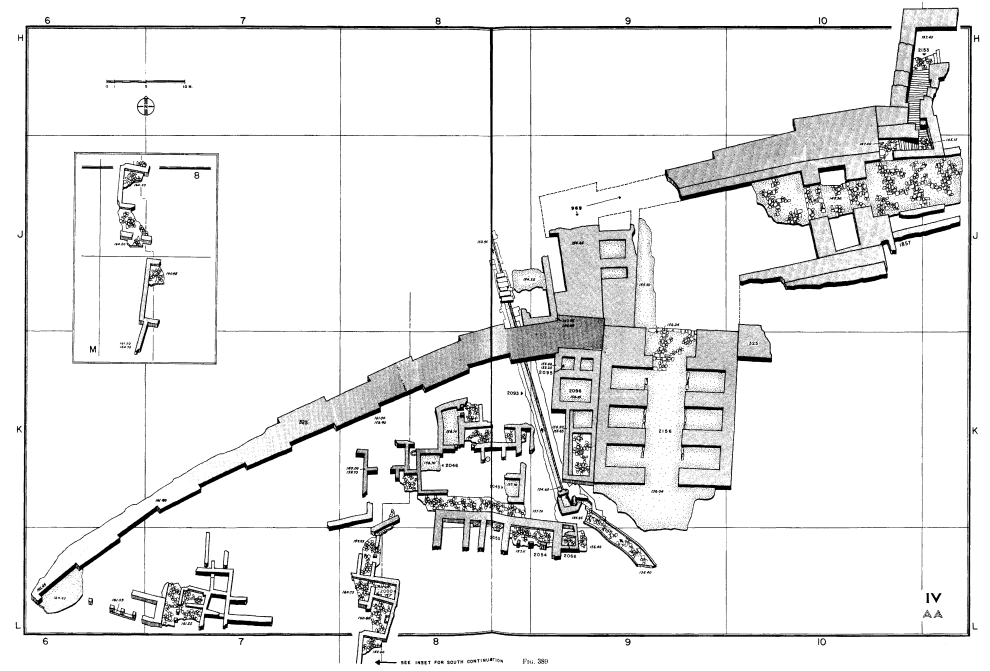

- Fig. 5.1 - Map of the

mound and excavation areas of the Tel Aviv University expedition from Ussishkin (2018))

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1

Excavation areas of the Tel Aviv University expedition

Ussishkin (2018) - Map of the site and

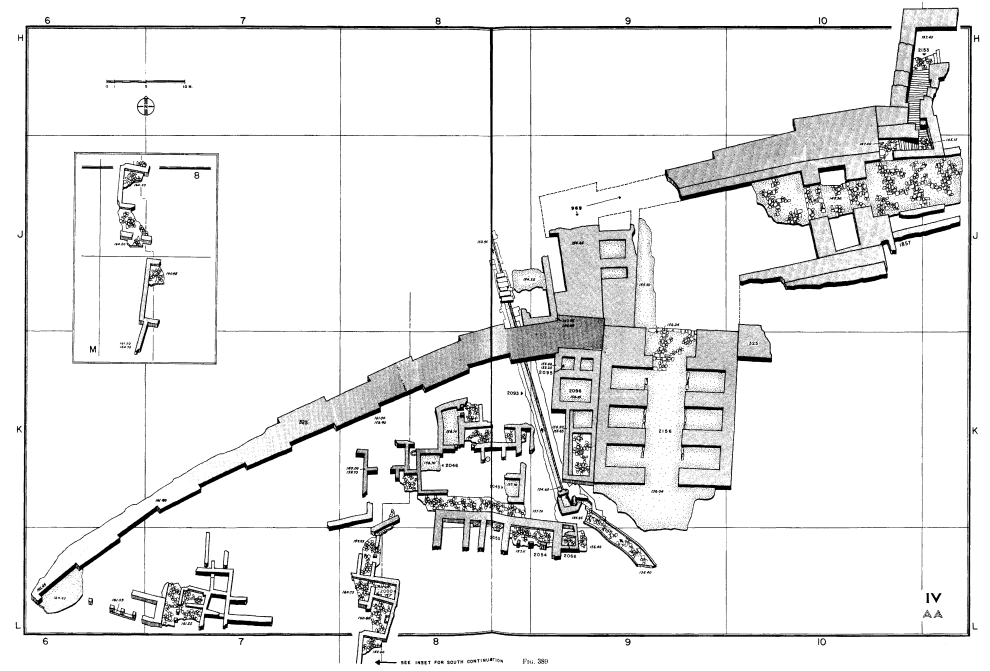

renewed excavation areas from Stern et al (2008 v. 5)

Megiddo: map of the site, showing excavation areas

Megiddo: map of the site, showing excavation areas

Stern et al (2008 v. 5) - Fig. 1 Map of the site

with excavation areas from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Aerial view of Megiddo, looking north, indicating the excavation areas discussed in the article

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023)

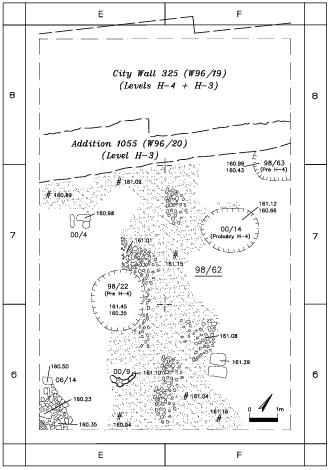

- Fig. 5.1 - Map of the

mound and excavation areas of the Tel Aviv University expedition from Ussishkin (2018))

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1

Excavation areas of the Tel Aviv University expedition

Ussishkin (2018) - Map of the site and

renewed excavation areas from Stern et al (2008 v. 5)

Megiddo: map of the site, showing excavation areas

Megiddo: map of the site, showing excavation areas

Stern et al (2008 v. 5) - Fig. 1 Map of the site

with excavation areas from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Aerial view of Megiddo, looking north, indicating the excavation areas discussed in the article

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023)

- Plan of Strata

VA-IVB and IVA from Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

Megiddo: plan of the city and main buildings in strata VA-IVB and IVA.

Megiddo: plan of the city and main buildings in strata VA-IVB and IVA.

Stern et al (1993 v. 3) - Fig. 15.2 - Plan of

Strata VA-IVB from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 15:2

Fig. 15:2

Plan of Stratum VA-IVB

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 18.1 - Plan of

Stratum IVA from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 18:1

Fig. 18:1

Plan of Stratum IVA

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 19.3 - Plan of

Stratum III from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 19:3

Fig. 19:3

Plan of Stratum III, after Ze'ev Herzog

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 24 Evidence for

the fierce conflagration of Stratum VIA from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

Evidence for the fierce conflagration of Stratum VIA at Megiddo; areas with evidence for burials/human remains under collapse are indicated. Though the stratigraphic situation in Area BB is fuzzy, signs of a violent event were found there too.

Kleiman et al. (2023)

- Plan of Strata

VA-IVB and IVA from Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

Megiddo: plan of the city and main buildings in strata VA-IVB and IVA.

Megiddo: plan of the city and main buildings in strata VA-IVB and IVA.

Stern et al (1993 v. 3) - Fig. 15.2 - Plan of

Strata VA-IVB from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 15:2

Fig. 15:2

Plan of Stratum VA-IVB

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 18.1 - Plan of

Stratum IVA from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 18:1

Fig. 18:1

Plan of Stratum IVA

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 19.3 - Plan of

Stratum III from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 19:3

Fig. 19:3

Plan of Stratum III, after Ze'ev Herzog

Ussishkin (2018)

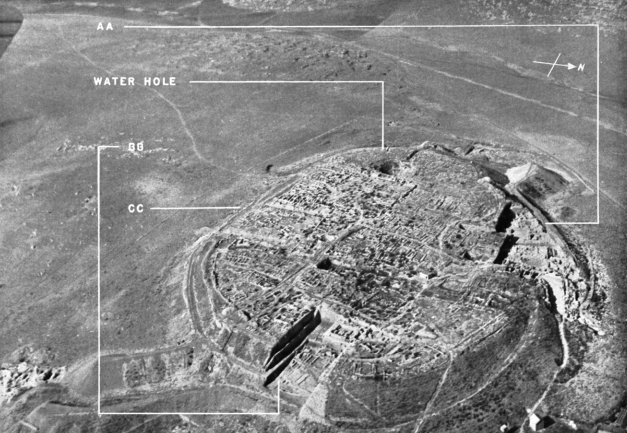

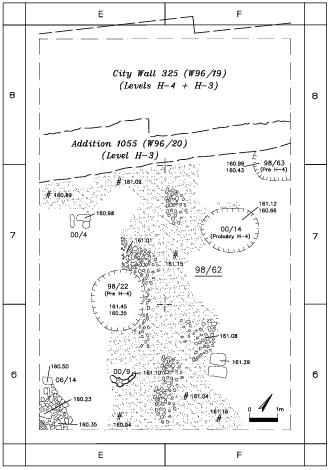

Fig. 31.2

Fig. 31.2Location map of deformed structures at Megiddo. Arrows indicate direction of shaking. Stars mark deformation that cannot be associated with a particular sense of movement.

JW: Excavation Area Overlay in Red is approximate

Modified from Marco et. al. (2006)

Fig. 31.2

Fig. 31.2Location map of deformed structures at Megiddo. Arrows indicate direction of shaking. Stars mark deformation that cannot be associated with a particular sense of movement.

Marco et. al. (2006)

- Fig. 2.5a - Excavation

areas of Schumacher from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 2:5a

Fig. 2:5a

The plan of the tell and the excavations prepared by Schumacher

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 2.5b - North-South

section of Schumacher from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 2:5b

Fig. 2:5b

North-South section prepared by Schumacher

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 3.5 - Excavation

areas of Oriental Institute expedition (Univ. of Chicago) from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 3:15

Fig. 3:15

The excavation areas of the Oriental Institute expedition

Ussishkin (2018)

- Fig. 2.5a - Excavation

areas of Schumacher from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 2:5a

Fig. 2:5a

The plan of the tell and the excavations prepared by Schumacher

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 2.5b -

North-South section of Schumacher from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 2:5b

Fig. 2:5b

North-South section prepared by Schumacher

Ussishkin (2018) - Fig. 3.5 - Excavation

areas of Oriental Institute expedition (Univ. of Chicago) from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 3:15

Fig. 3:15

The excavation areas of the Oriental Institute expedition

Ussishkin (2018)

- Fig. 2.5b -

North-South section of Schumacher from Ussishkin (2018)

Fig. 2:5b

Fig. 2:5b

North-South section prepared by Schumacher

Ussishkin (2018)

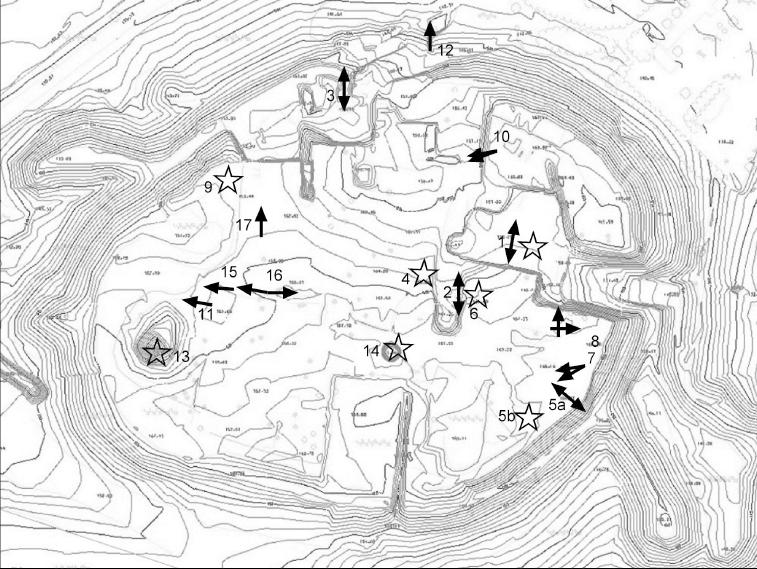

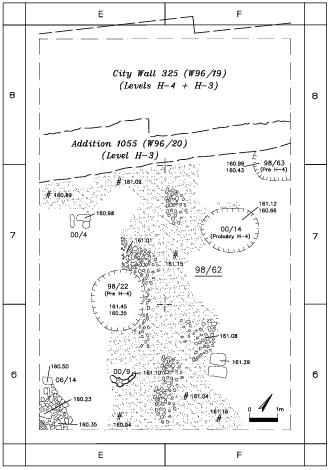

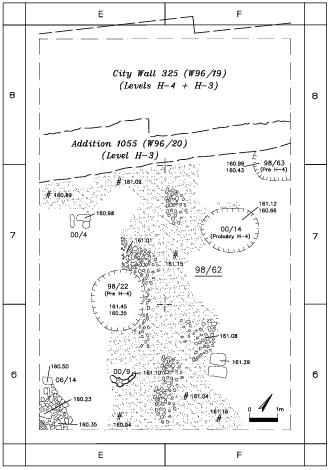

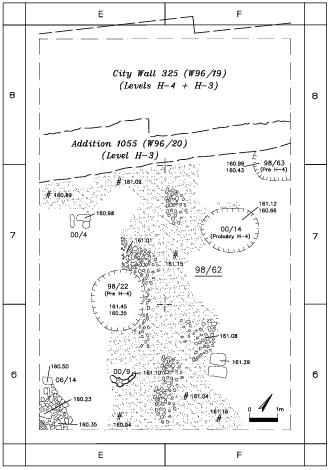

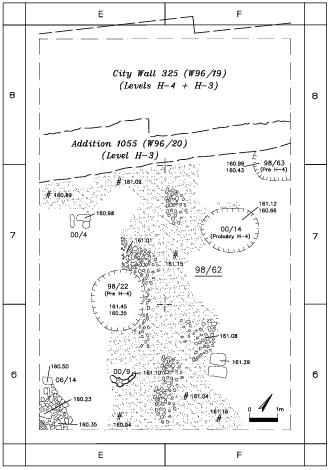

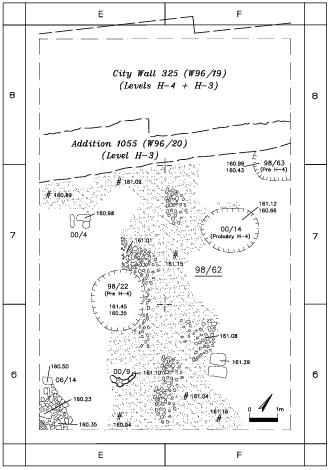

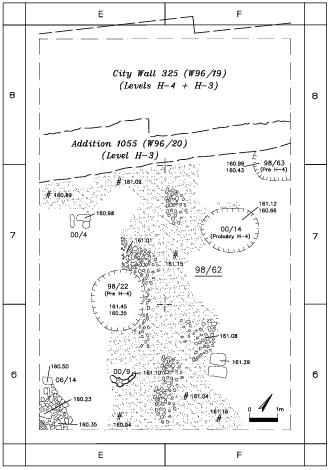

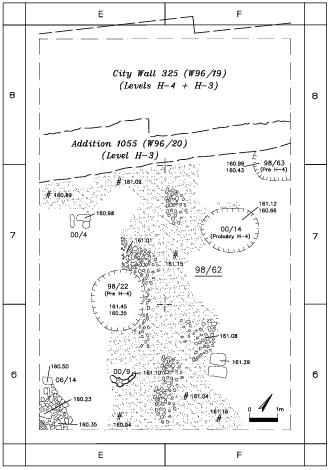

- Fig. 5.2 - Plan of

Level H-9 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2

Plan of Level H-9

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.8 - Photo of

Level H-9 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.8

General view of Level H-9, looking north.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.4 - South

section of Area H from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4

South section of Area H (Squares E—F/6).

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.5 - East section

of Area H from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.5

East section of Area H (Squares F/6-9).

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.6 - West section

of Area H from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6

West section of Area H (Squares E/6-9).

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.7 - Eastern section

of Area H from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.7

Eastern section of Squares E/6-9.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.8 - Photo of

Level H-9 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.8

General view of Level H-9, looking north.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.25 - Plan of Level H-5

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.25

Figure 5.25

Plan of Level H-5

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.26 - View of Level H-5 looking north

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.26

Figure 5.26

General View of Level H-5, looking north

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

- Fig. 5.2 - Plan of

Level H-9 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2

Plan of Level H-9

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.4 - South

section of Area H from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4

South section of Area H (Squares E—F/6).

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.5 - East section

of Area H from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.5

East section of Area H (Squares F/6-9).

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.6 - West section

of Area H from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6

West section of Area H (Squares E/6-9).

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.7 - Eastern section

of Area H from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.7

Eastern section of Squares E/6-9.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.8 - Photo of

Level H-9 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.8

General view of Level H-9, looking north.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.25 - Plan of

Level H-5 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.25

Figure 5.25

Plan of Level H-5

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.26 - View of

Level H-5 looking north from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.26

Figure 5.26

General View of Level H-5, looking north

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

- Fig. 3.2 Plan of the

Stratum XIX Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

Plan of the Stratum XIX Temple

(after Loud 1948: Fig. 390; Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago).

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 3 Reconstruction

of the Great Temple of Stratum XVIII (Level J-4) from Sapir-Hen et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Plan of the Great Temple of Level J-4.

(Illustration by M. J. Adams)

Sapir-Hen et al. (2022) - Fig. 2.7 - Reconstruction

of the Great Temple of Stratum XVIII (Level J-4) from Ussishkin (2011)

Fig. 2.7

Fig. 2.7

The Great Temple of Stratum XVIII; a reconstructed plan.

Ussishkin (2011) - Fig. 2.37 - Section from

Squares H–G/7–8, eastern section from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.37

Figure 2.37

Squares H–G/7–8, eastern section.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

- Fig. 3.2 Plan of the

Stratum XIX Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

Plan of the Stratum XIX Temple

(after Loud 1948: Fig. 390; Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago).

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 3 Reconstruction

of the Great Temple of Stratum XVIII (Level J-4) from Sapir-Hen et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Plan of the Great Temple of Level J-4.

(Illustration by M. J. Adams)

Sapir-Hen et al. (2022) - Fig. 2.7 - Reconstruction

of the Great Temple of Stratum XVIII (Level J-4) from Ussishkin (2011)

Fig. 2.7

Fig. 2.7

The Great Temple of Stratum XVIII; a reconstructed plan.

Ussishkin (2011) - Fig. 2.37 - Section from

Squares H–G/7–8, eastern section from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.37

Figure 2.37

Squares H–G/7–8, eastern section.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

- Fig. 2.6 - Superposition

of temples in the cultic area from Ussishkin (2011)

Fig. 2.6

Fig. 2.6

Diagram showing the superposition of the temples in the cultic area:

- at the bottom, at left – the Stratum XIX temple

- above it, and further to the right – The Great Temple of Stratum XVIII

- above it – the Round Altar (Stratum XVI) and the three Megaron Temples (Stratum XV)

- at the top – the Tower Temple of the Middle and Late Bronze Ages

Ussishkin (2011)

- Fig. 2.6 - Superposition

of temples in the cultic area from Ussishkin (2011)

Fig. 2.6

Fig. 2.6

Diagram showing the superposition of the temples in the cultic area:

- at the bottom, at left – the Stratum XIX temple

- above it, and further to the right – The Great Temple of Stratum XVIII

- above it – the Round Altar (Stratum XVI) and the three Megaron Temples (Stratum XV)

- at the top – the Tower Temple of the Middle and Late Bronze Ages

Ussishkin (2011)

- Fig. 7.7 Plan of

Level K-4 from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 7.7

Figure 7.7

Plan of Level K-4

Finkelstein et al. (2006)

- Fig. 7.7 Plan of

Level K-4 from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 7.7

Figure 7.7

Plan of Level K-4

Finkelstein et al. (2006)

- Fig. 4.20 - Plan of

Level M-4 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 4.20

Figure 4.20

Plan of Level M-4.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.1 Left - Location

of Area M vis-a-vis the central sector of Schumacher's trench (plan) from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

Location of Area M vis-a-vis the central sector of Schumacher's trench. Plan.

(based on Loud 1948: Fig. 415)

Finkelstein et al. (2006) - Fig. 5.1 Right - Location

of Area M vis-a-vis the central sector of Schumacher's trench (Aerial view) from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

Location of Area M vis-a-vis the central sector of Schumacher's trench. Aerial view 1998, looking north.

Finkelstein et al. (2006)

- Fig. 4.20 - Plan of

Level M-4 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 4.20

Figure 4.20

Plan of Level M-4.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.1 Left - Location

of Area M vis-a-vis the central sector of Schumacher's trench (plan) from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

Location of Area M vis-a-vis the central sector of Schumacher's trench. Plan.

(based on Loud 1948: Fig. 415)

Finkelstein et al. (2006) - Fig. 5.1 Right - Location

of Area M vis-a-vis the central sector of Schumacher's trench (Aerial view) from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

Location of Area M vis-a-vis the central sector of Schumacher's trench. Aerial view 1998, looking north.

Finkelstein et al. (2006)

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of

Squares H–I/4–5 in Area Q from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial view of Squares H–I/4–5 in Area Q at the end of the 2016 season, looking north

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Plan of Level

Q-9 of the Late Bronze III from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of Level Q-9 of the Late Bronze III (this phase was revealed only in limited probes below the floors of Level Q-8)

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 6 Plan of Level

Q-8 from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Plan of Level Q-8; shaded walls signify elements built in a previous occupational phase and reused

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 8 Plan of Level

Q-7b from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Plan of Level Q-7b; shaded walls signify elements built in a previous occupational phase and reused

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 10 Plan of Level

Q-7a from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Plan of Level Q-7a; shaded walls signify elements built in a previous occupational phase and reused

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023)

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of

Squares H–I/4–5 in Area Q from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial view of Squares H–I/4–5 in Area Q at the end of the 2016 season, looking north

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Plan of Level

Q-9 of the Late Bronze III from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of Level Q-9 of the Late Bronze III (this phase was revealed only in limited probes below the floors of Level Q-8)

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 6 Plan of Level

Q-8 from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Plan of Level Q-8; shaded walls signify elements built in a previous occupational phase and reused

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 8 Plan of Level

Q-7b from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Plan of Level Q-7b; shaded walls signify elements built in a previous occupational phase and reused

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 10 Plan of Level

Q-7a from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Plan of Level Q-7a; shaded walls signify elements built in a previous occupational phase and reused

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023)

- Fig. 3.2 Plan of the

Stratum XIX Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

Plan of the Stratum XIX Temple

(after Loud 1948: Fig. 390; Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago).

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 3.1 Aerial view of

f Area J at the end of the 1996 season from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1

Aerial view of Area J at the end of the 1996 season; looking east.

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 31.3D - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3D

Figure 31.3D

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 31.3E - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3E

Figure 31.3E

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 31.3F - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3F

Figure 31.3F

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 40.1 - Extension

Fractures in Stone Wall of Level J-4 Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 3)

Figure 40.1

Figure 40.1

Wall 96/J/1 in Square H-10, looking east. Note fracture along the strike on the edge of the wall.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 3) - Fig. 2.28 - J-4 Temple

Collapse Layer from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.28

Figure 2.28

Square H/7 east section. Striated remains near the base of the section are Level J-4a squatter’s debris and temple collapse (see also Fig. 2.38). At left, Probe 06/J/099/PT003 reveals the bottom of Wall 00/J/21. Note phytolith level 08/J/185 in low baulk at right.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013) - Fig. 2.47 - Strike Fractures

in Temple 4040 from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.47

Figure 2.47

Strike fractures in Temple 4040 Wall 08/J/38.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

- Fig. 3.2 Plan of the

Stratum XIX Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

Plan of the Stratum XIX Temple

(after Loud 1948: Fig. 390; Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago).

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 3.1 Aerial view of

Area J at the end of the 1996 season from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1

Aerial view of Area J at the end of the 1996 season; looking east.

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 31.3D - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3D

Figure 31.3D

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 31.3E - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3E

Figure 31.3E

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 31.3F - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3F

Figure 31.3F

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 40.1 - Extension

Fractures in Stone Wall of Level J-4 Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 3)

Figure 40.1

Figure 40.1

Wall 96/J/1 in Square H-10, looking east. Note fracture along the strike on the edge of the wall.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 3) - Fig. 2.28 - J-4 Temple

Collapse Layer from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.28

Figure 2.28

Square H/7 east section. Striated remains near the base of the section are Level J-4a squatter’s debris and temple collapse (see also Fig. 2.38). At left, Probe 06/J/099/PT003 reveals the bottom of Wall 00/J/21. Note phytolith level 08/J/185 in low baulk at right.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013) - Fig. 2.47 - Strike Fractures

in Temple 4040 from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.47

Figure 2.47

Strike fractures in Temple 4040 Wall 08/J/38.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

- Fig. 31.3H - Extension cracks and

shifted Ashlars in the Late Bronze gate from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3H

Figure 31.3H

Extension cracks in the Late Bronze gate. Ashlar stones in courses in the middle of the walls (sandwiched between other courses) are fractured in opening mode. Horizontal sliding of the fragments occurred everywhere in the same direction, sub-parallel to N-S trend of the wall (Fig. 31.3h). The gate has no foundations, a fact that could have made it particularly vulnerable to seismic vibrations.

Marco et. al. (2006)

- Fig. 5.3 - Destruction Layers H-5 and H-9

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3

Southern section of Area H, looking south. The figure is standing on the floor of Level H-9. From bottom: the thick accumulation debris of Level H-9, the floors of Level H-7 and the destruction of Level H-5. (Note the differences in the nature of destruction between Levels H-9 and H-5.)

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.8 - Photo of Level H-9

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.8

General view of Level H-9, looking north.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.9 - Smashed storage jar

and charred beam in Level H-9 from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.9

Figure 5.9

Smashed storage jar lying on the floor of Courtyard 08/H/38 of Level H-9 (note charred beam between mudbricks), looking east.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.10 - Complete storage jar in Level H-9

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.10

Figure 5.10

A complete storage jar on Paved Floor 06/H/51 in the northwestern part of Courtyard 08/H/38 of Level H-9 (note the depth of City Wall 325), looking east.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.11 - Smashed pottery vessels in Level H-9

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.11

Figure 5.11

Smashed pottery vessels in the eastern part of Courtyard 08/H/38 with Partition wall 06/H/8, Level H-9, looking east.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 3 Stratum VIA destruction

debris in Area Q from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

A typical accumulation of the destruction debris of Stratum VIA. The black line at the bottom of the debris signifies the floor; Square I/2 in Area Q, looking north

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 5 Pottery on the floor of

Level Q-9 from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Restorable vessels on the floor of Level Q-9. On the left, the eastern wall of Schumacher’s Südliches Burgtor; looking north

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 7 Floor of Level Q-8

from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Floor 14/Q/106 of Level Q-8 below remains of Level Q-7, looking north

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 9 Stone pillars in Area Q

from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9- Two of the three octagonal stone pillars of a possibly small shrine in Square I/4 after the 2014 season (Building 14/ Q/145), looking east (courtesy of the Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology)

- combined 3D model of Squares I/ 3–4 in Area Q, after the exposure of the third octagonal pillar in the 2016 season

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 11a pavement of Level Q-7a

building from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 11a

Fig. 11a

The pavement of the new Level Q-7a building erected above Building 14/Q/145, looking north-east; note the third pillar of Building 14/Q/145 on the right side of the photo

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 11b broken stelae originating

from pavement of Building 16/Q/48 from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 11b

Fig. 11b

one of the broken stelae, which originated from the pavement of Building 16/Q/48

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 12 Level Q-7 (Stratum VIA)

destruction layer from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12

A view of the destruction of the Level Q-7 (Stratum VIA) city in Squares H/4–5, looking south-east

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 13 Level Q-6b stone monolith

erected above the ruins of the Iron I destruction from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

A stone monolith erected in Level Q-6b above the ruins of the Iron I destruction, looking north

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 14 Skeletal remains

from Stratum VIA destruction in Area Q from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 14

Fig. 14

Remains of an individual found in Locus 16/Q/79:

- schematic diagram that shows which skeletal elements were recovered (in grey)

- in situ photo of the individual’s right pelvis and femoral head

- proximal ends of right (on left) and left (on right) radii, showing differential size and colouration

- left (on left) and right (on right) fourth metacarpals, showing differential size and colouration

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 17 Iron blades and stacked

bronze bowls from cache from Locus 12/Q/76 from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

The cache from Locus 12/Q/76, which contained iron blades placed beside two stacked bronze bowls filled with additional items

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition).

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 21 Burials in Area CC

along with smashed pottery from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

Burials in Square Q/10 (Locus 1770) in Area CC (Harrison 2004: fig. 73). Note the relationship between the skeletons on the right, with respect to architecture and the smashed pottery

(courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures of the University of Chicago)

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 22 Skeletal remains in

Area K from Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 22

Fig. 22

Skeletal remains in articulation in Baulk N–O/11 (Locus 04/K/38) in Area K. Note that the initial exposure of the individual was under Locus 04/K/26

(courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition, previously unpublished photo)

Kleiman et al. (2023) - Fig. 7.10 Destruction

layer of Level K-4 showing collapsed mudbricks and vessels from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 7.10

Figure 7.10

Destruction layer of Level K-4 in the southern baulk of Square N/11. Note collapse of mudbricks and vessels.

Finkelstein et al. (2006) - Fig. 7.11 Destruction

layer of Level K-4 from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 7.11

Figure 7.11

Destruction layer of Level K-4 in Square O/9.

Finkelstein et al. (2006) - Fig. 7.12 Square O/9

with remains of Level K-4 (Tabun 00/K/19), looking south from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 7.12

Figure 7.12

Square O/9 with remains of Level K-4 (Tabun 00/K/19), looking south.

Finkelstein et al. (2006) - Fig. 7.13 Room 00/K/45

of Level K-4 from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 7.13

Figure 7.13

Room 00/K/45 of Level K-4, looking west

Finkelstein et al. (2006) - Fig. 7.14 Square M/11

of Level K-4 from Finkelstein et al. (2006)

Figure 7.14

Figure 7.14

Square M/11, looking north. Note plaster floor of Level K-6 and lines of ash cut by a robber trench in the section

Finkelstein et al. (2006)

- Fig. 5.26 - View of Level H-5 looking north

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.26

Figure 5.26

General View of Level H-5, looking north

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.27 - Level H-5 Destruction Layer

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.27

Figure 5.27

The southern section of Area H with Level H-5 destruction in the centre of the picture (note the sloping down of the Level H-5 floor toward Installation 06 H 14 in the right) and Level H-7 floors, looking south.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1) - Fig. 5.28 - Level H-5 Destruction Debris

from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 5.28

Figure 5.28

Destruction debris on Floor 98 H 62 of Level H-5, looking west.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

- Fig. 2.12 - Strata VIII-VII Canaanite Gate

before restoration from Ussishkin (2011)

Fig. 2.12

Fig. 2.12

The late Canaanite city-gate (Strata VIII-VII)

Ussishkin (2011) - Old photo of the Canaanite Gate

from Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

LB city gate in area AA.

LB city gate in area AA.

Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

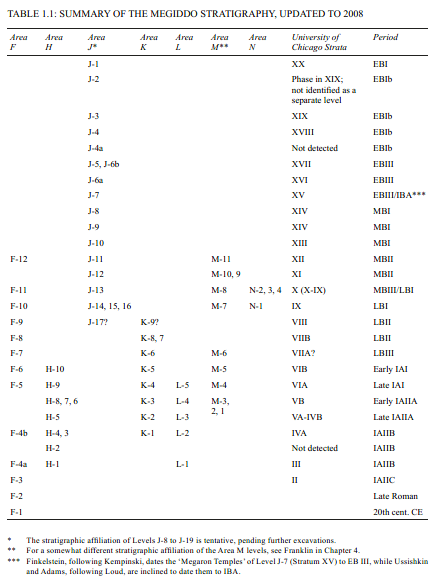

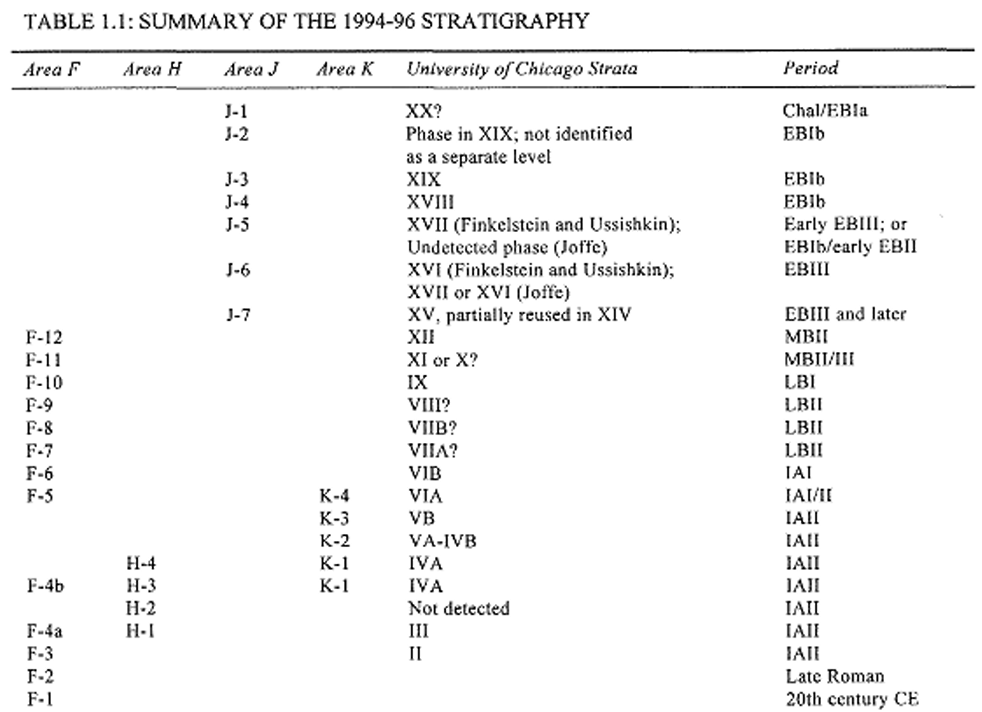

The renewed excavations dealt with almost the entire sequence of occupation at Megiddo, from stratum XX of the Chalcolithic/Early Bronze Age IA to stratum III of the late Iron Age II. A dual system for labeling the strata has been adopted. In each excavation area the local strata have been labeled as “levels,” the letter designating the area used as a prefix for the number of the level, e.g., “level K-3” in area K or “level H-2” in area H. In each excavation area the levels are counted from top to bottom, except for area J, where local conditions dictated a count from bottom up. As to the general stratigraphy of the site, the Chicago Expedition’s strata numbering system, e.g., “stratum XII,” has been followed.

Table 1.1

Table 1.1Summary of Megiddo stratigraphy updated to 2008

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Table 1.1

Table 1.1Summary of the 1994-1996 Stratigraphy

Finkelstein et al. (2000)

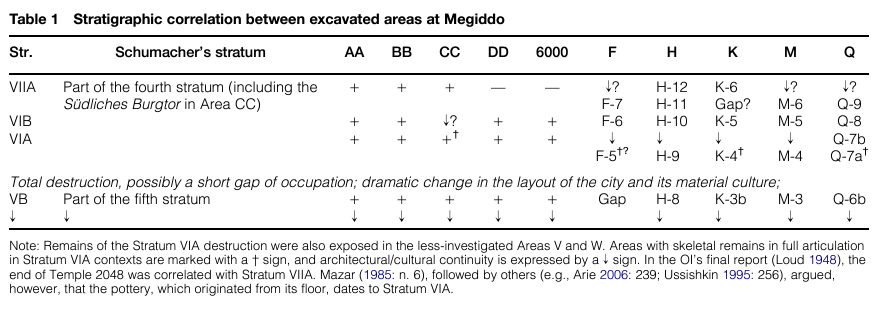

Table 1

Table 1Stratigraphic correlation between excavated areas at Megiddo

Kleiman et al. (2023)

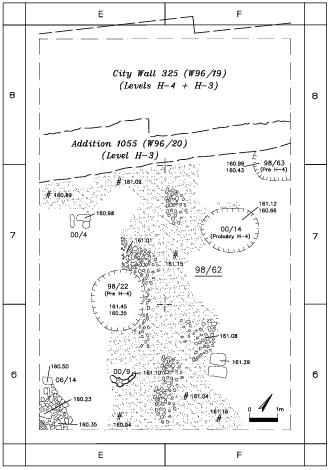

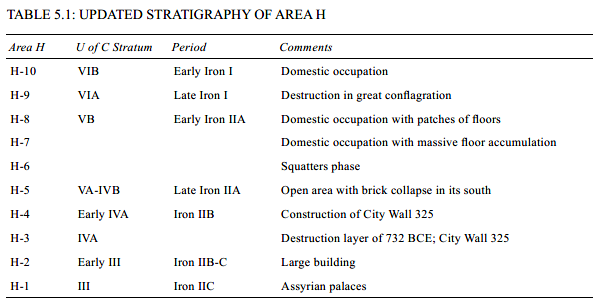

Table 5.1

Table 5.1Updated Stratigraphy of Area H

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Table 2.2

Table 2.2Revised and Augmented Stratigraphy of Area J

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1Updated Stratigraphy and Chronology of Early Bronze Age Megiddo

Finkelstein et al. (2006, Megiddo IV: Vol. 1)

Table 2.6

Table 2.6Schematic Stratigraphic Sequence Of The Level J-4 Floor And The Phase J-4a Activity

Finkelstein et al. (2006, Megiddo IV: Vol. 1)

- from Ussishkin (2015)

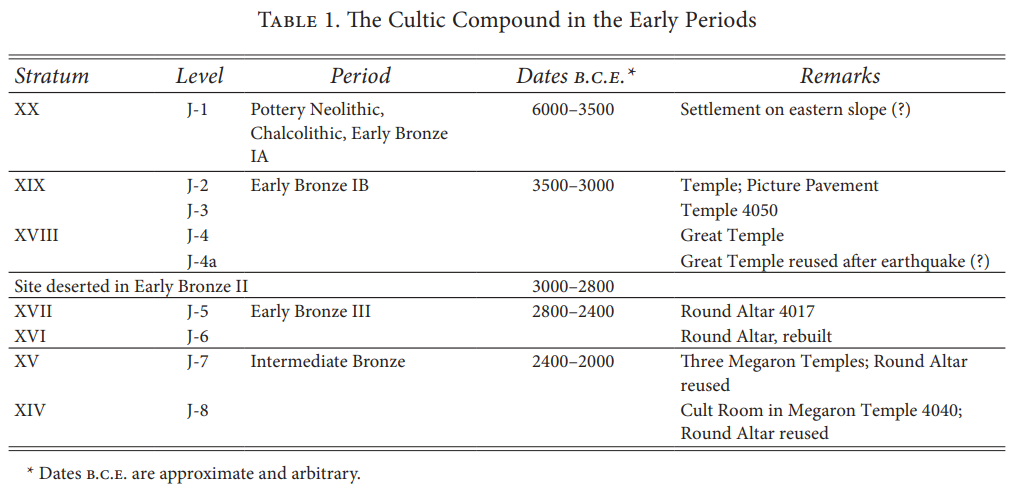

Table 1

Table 1The Cultic Compound in the Early Periods

Ussishkin (2015)

Table 2

Table 2The Six Stages of the Sacred Area during Strata XX-XIV Levels J-1 - J-8

Ussishkin (2015)

| Area K Level | The University of Chicago stratum | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-6 | ‘VIC’ or VIIA | End phase of Late Bronze | No wholesale destruction |

| K-5 | VIB | Early Iron I | Locally made Myc. IIIC vessel |

| K-4 | VIA | Late Iron I | Destroyed in violent fire |

| K-3 | VB | Iron IIA | Two main phases |

| K-2 | VA-IVB | Iron IIA | Two main phases |

| K-1 | IVA | Iron II | City Wall 325 |

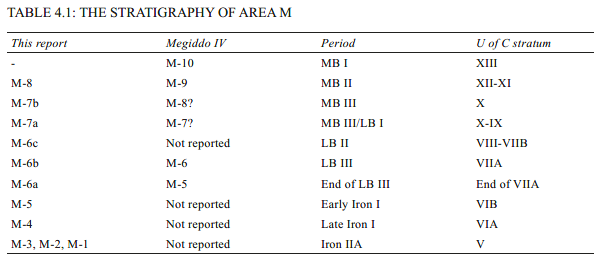

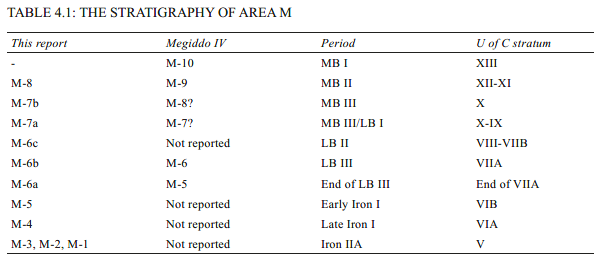

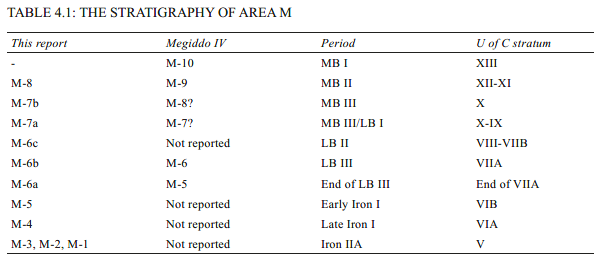

Table 4.1

Table 4.1The Stratigraphy of Area M

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Table 4.3

Table 4.3UPDATED STRATIGRAPHY OF AREA M (REPLACING FINKELSTEIN, USSISHKIN AND DEUTSCH 2006: 80, TABLE 5.1)

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 1)

Table 3

Table 3Radiocarbon dates from Level Q-9 to Q-6b (Boaretto 2022: table 41.1

Kleiman et al. (2023)

Fig. 20

Fig. 20The Area Q radiocarbon sequence ((based on the data reported in Boaretto 2022: table 41.1

Kleiman et al. (2023)

Krauwer (2016) observes that, owing to the

uncertainty surrounding the date of

Shoshenq I’s

campaign, attempts to associate specific

destruction layers with that event have proven

problematic. He notes that “we do not have even

one destruction layer which can safely be assigned

to this campaign,” adding that at several sites

multiple destruction horizons exist—for example at

Megiddo, where both Stratum VIA and Stratum

VA–IVB “can be attributed to Shoshenq’s campaign”

(Finkelstein 1996: 180). The most potentially

significant piece of evidence relevant to this

debate was recovered out of context during the

Megiddo excavations: a fragment of a large stone

bearing the name of

Pharaoh

Shoshenq I, discovered

near the eastern edge of the mound in one of

Schumacher’s dumps during Fisher’s excavations.

- from Krauwer (2016:1-4)

The importance of Megiddo is due in part to its strategic location on the international highway running north-south, and thus competing powers in the region have vied for control of this tel for centuries (Finkelstein 2002: 117). Evidence for the desirability of this prime location can be seen in the numerous destruction layers at the site, leaving tangible remains from the ancient near eastern powers that sought to control this territory.

The culprit responsible for the destruction of the late Iron Age I city, represented by Stratum VIA, however, has remained elusive to scholars for decades. This city was destroyed in its entirety, unlike the partial destructions uncovered in excavations from the Late Bronze III, late Iron Age IIA, and Iron IIB (Finkelstein 2013: 1336). The violent end of the Iron I city is thus unique in its totality, yet the agent responsible cannot be easily discerned through archaeological or textual data. Past explanations have included the conquest of King David and the establishment of the United Monarchy, the campaign of the Egyptian Pharaoh Shoshenq I, the expansion of the Israelite polity from the northern highlands, or a massive earthquake that felled several cities in the region. After a critical analysis of all of these theories, the only plausible option that remains for the destruction of Megiddo Stratum VIA is that of the expanding Israelites from the highlands, who conducted a series of campaigns to the region in an attempt to expand their territory into more desirable areas.

- from Krauwer (2016:4-6)

Excavations at the site have provided incredible contributions to the field of archaeology, including advances in the typological understanding of ceramics, radiocarbon studies, as well as a well-defined stratigraphic sequence containing layers from throughout the Bronze and Iron Ages that are often used to determine the relative chronologies of nearby sites.

Of interest at present is the destruction of Stratum VI, first identified during Shumacher’s excavations and later divided by the University of Chicago’s team “into two phases – VIB and VIA – although an actual division with clear stratigraphy was possible only in Areas AA and DD” (Arie 2006: 191; see also Schumacher 1908: 80; Loud 1948: 33). Stratum VIB is understood as the early Iron Age I stratum at the site, remains of which were found in Levels F-6, H-10, K-5, and M-5, whereas Stratum VIA represents the late Iron Age I and this city’s destruction, remains from which were found in Levels F-5, H-9, K-4, L-5, and M-4. The separation between these to phases is “somewhat artificial,” as they both belong to the same Iron Age I city which developed gradually, culminating in the destruction of the city at the end of Stratum VIA, evidence for which “was unearthed by all excavators, in almost every area of excavations” (Finkelstein 2002: 117; 2009: 115).

The destruction of Stratum VIA has been a highly debated topic, due in part to the implications that it has regarding the dating and historical reliability of events such as Shoshenq I’s campaign to the Levant, possibilities of natural disasters in the region, and the historicity of the United Monarchy. Before moving forward, two crucial points regarding Stratum VIA should be noted. First, the conflagration that took place was intense and total, suggesting that this stratum did not end with a peaceful abandonment but rather a severe or catastrophic event. Second, the general city layout as well as the pottery of Stratum VIA shows continuity with the Late Bronze traditions, yet discontinuity with the following Stratum VB city, which contains distinctly Iron Age characteristics (Finkelstein and Ussishkin 2000: 595-596; Finkelstein 2009: 116). This suggests that following the destruction of Stratum VIA a new people settled at the site and brought with them their own customs and traditions, made evident from the material culture of the site.

Thus, scholars have suggested a number of possible scenarios to explain the destruction of this city. While some have attributed it to the military campaigns of Pharaoh Shoshenq I (Watzinger 1929: 58, 91; Finkelstein 2002), King David (Yadin 1970: 95; Harrison 2004: 108), or the expanding Israelite polity from the hill country (Finkelstein 2009: 122-123), others have suggested a natural phenomenon as the culprit: a major earthquake in the region (Lamon and Shipton 1939: 7; Marco et al. 2006; Cline 2011). Each theory indeed contains its own problems, however after a critical analysis of each it will be shown that the most plausible historical reconstruction is to attribute the destruction of Megiddo Stratum VIA to the expansion of the Israelite territory to the region.

1. Finkelstein, Ussishkin and Halpern 2000:1-3; see also Schumacher 1908; Watzinger 1929; Lamon 1935; May 1935; Guy 1938; Lamon and Shipton 1939; Yadin 1970; for summary of the history of the site and the results of past excavations see Davies 1986; Kempinski 1989; Ussishkin 1992; Aharoni and Shiloh 1993.

- from Krauwer (2016:6-7)

In an attempt to resolve the chronological dispute scholars have looked to radiocarbon dating in order to determine an absolute date for the destruction of this stratum. Following a study conducted using samples from seven sites, five of which were destroyed by fire, it seems that the end of the late Iron Age I in northern Israel was not a result of a single catastrophic event, but rather “two main events, or two clusters of events, in 1047-996 BCE and 974-915 BCE according to the ‘uncalibrated weighted average method (Finkelstein and Piasetzky 2007); 1017-984 and 969-898 BCE according to a Bayesian model constructed for this purpose (Finkelstein and Piasetzky: 2009)” (Finkelstein 2013: 1337). Following this study, the destruction of Stratum VIA has been assigned to the mid 10th century BCE (Finkelstein 2010: 11; 2013: 1337).

The Low Chronology seems to provide the more accurate dates for a variety of reasons. Not only does the High Chronology independently contain problems of its own (see Finkelstein 2010: 7-9), the Low Chronology solves many of the problems contained within the traditional dating system both within Israel and in the surrounding region, creating a more unified and harmonious picture of the Iron Age I-II in the greater context of the Mediterranean world (see Finkelstein 1999: 39). With a more accurate chronology of this period, one is able to more securely determine the historical event(s) responsible for destructions in northern Israel at the end of the Iron Age I.

2 Finkelstein, Ussishkin and Halpern 2006: 850; for the varying dates see Yadin 1970; Mazar in Bruins, van der Plicht and Mazar 2003; Finkelstein 2002; 2003a; for a summary of the High and Low Chronology dates assigned to Strata VIB and VIA see Gilboa, Sharon and Boaretto 2013: 1122.

- from Krauwer (2016:7-12)

The conquest of King David (especially in the north) and the rule of the United Monarchy should be the first historical reconstruction to be dismissed. First of all, this scenario is based almost entirely on the biblical narrative and has little to no support in the archaeological record. Second, it is implausible to imagine that David’s conquest led to the establishment of a full-blown kingdom in such a short amount of time. “The Israelite kingdom could not have developed so rapidly into the stage that sociologists call a ‘grown state’…the picture drawn in the Bible cannot be sustained” (Na’aman 2007: 401). If David was indeed a historical king his territory was likely restricted to a small territory in the southern highlands around Jerusalem (Finkelstein 2010: 20). State formation in the north was surely a slow and gradual process from the mid 10th until the early 9th centuries BCE (Na’aman 2007: 404).

After eliminating the possibility of a Davidic campaign, three possible historical reconstructions remain:

- destruction by earthquake

- conquest by Pharaoh Shoshenq I

- the expansion of the Israelites from the northern highlands

Due to Megiddo’s location in the Carmel fault zone it is particularly prone to seismic

activity. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that Stratum VIA was destroyed in a

massive earthquake, and in 2006 Shmuel Marco et al. published a report documenting the

dates and probabilities of seismic events at Megiddo. Attributing a destruction level to an

earthquake, however, is difficult to prove, as “Earthquake-related damage often

resembles that deliberately caused by humans, geotechnical failure, or slow deterioration

over the ages” (Marco et al. 2006: 569). Investigators thus looked for certain criteria that

could suggest seismic activity, the main criterion being “time-constrained widespread

damage. The temporal bounds should be tight enough to indicate that the damage

occurred in a single catastrophic event” (Marco et al. 2006: 569). Other significant

pieces of evidence include the absence or scarcity of weapons, historical records that

document seismic activity, “deformation of coeval natural sediments, and the existence of

certain types of damage that are uniquely associated with earthquakes” (Marco et al.

2006: 569).

Ultimately, the study was inconclusive regarding the occurrence of a major

earthquake in Stratum VIA. Only two earthquakes were confirmed beyond doubt: “one

at the end of the fourth millennium BCE and another in the 9th century BCE (which caused

the damage in Stratum VA-IVB)” (Marco et al. 2006: 572). This study did not eliminate

the possibility of an earthquake in Stratum VIA, however there was no conclusive

evidence to support such an event (Marco et al. 2006: 572).

Despite the inconclusive results of the archaeoseismic study regarding Stratum

VIA, other considerations have supported the view that this city was not destroyed in an

earthquake. First of all, the remains from this stratum show extensive burning,

suggesting that the city was intentionally burned down by a hostile force. “It is difficult

to imagine that all the stone and brick-built houses could have simultaneously caught fire

due to an earthquake as might happen in a modern city” (Finkelstein, Ussishkin and

Halpern 2006: 850). Secondly, the following stratum showed discontinuity in material

culture, suggesting that a new population inhabited the later city and that the inhabitants

of the Stratum VIA city did not return following its destruction. “Had the Stratum VIA

settlement been destroyed by fire resulting from an earthquake we would have expected

the inhabitants to reconstruct their ruined houses without delay. The fact that they did not

return indicates that they were forced to abandon their settlement forever by a human

agent” (Finkelstein, Ussishkin and Halpern 2006: 850). Finally, as previously stated, the

radiocarbon results from the region suggest that there were two main destruction events,

further strengthening the theory that this destruction was part of an ongoing process such

as the gradual conquest of the region by an outside power rather than a single time-restricted event.

In the search for the military power responsible for the destruction of this city, the

Egyptian army of Pharaoh Shoshenq I has been a popular explanation. This campaign,

known from 1 Kgs 14:25-28 (cf. 2 Chr 12:1-12) as well as from the temple of Amun at

Karnak (see Simons 1937: 95-102), has traditionally been dated to around 926 BCE by the

biblical text (Finkelstein 2002: 109), which states that “In the fifth year of King

Rehoboam, King Shishak of Egypt came up against Jerusalem (1 Kgs 14:25, NRSV).

A late 10th century BCE date for Shoshenq’s campaign has proven troublesome for

the archaeologist. Egyptian records do not corroborate the precise year of his campaign,

thus some have suggested a wider range of possible dates for this event. Finkelstein

raises four main problems regarding the date of this campaign:

- the complicated chronology of the 21st and 22nd Dynasties in Egypt allow for the change of several years back or forth of Shoshenq I’s reign

- it is unknown whether his campaign occurred early or late in his rule

- the biblical references of the length of reigns of the early Davidides are completely schematized

- the fifth year of Rehoboam datum may have been altered to fit the theology of the Deuteronomistic Historian (Finkelstein 2002: 110).

Due to the uncertainty of the date of Shoshenq I’s campaign, identification of destruction layers to his campaign have been problematic. Indeed, “we do not have even one destruction layer which can safely be assigned to this campaign. For instance, in several sites there are two destruction horizons (e.g. and Megiddo, Stratum VIA and Stratum VA-IVB); both can be attributed to Shoshenq’s campaign” (Finkelstein 1996: 180). Furthermore, the destruction layer of Stratum IVA has also been attributed to this campaign (Guy 1931: 48).

Unfortunately, the most significant piece of evidence that could contribute to this debate was found out of context during Megiddo excavations. Found during Fisher’s excavations in one of Schumacher’s dumps, a fragment of a large stone stele of Pharaoh Shoshenq was discovered near the eastern edge of the mound (Ussishkin 1990: 71). This fragment appears to be part of a stele that would have measured approximately 3.30 m high, 1.50 m wide, and 50 cm thick (Ussishkin 1990: 72). Four criteria typify this type of monument:

First, they were erected by a monarch in a foreign land; second, their erection was carried out following, or in association with, a military campaign or submission by the local ruler to the conquering leader; third, they were erected in a public, central position inside a capital city; fourth, the city in question was inhabited at the time the monument was erected and dominated by the monarch who erected the stele (Ussishkin 1990: 72).As a result of this find many scholars do not attribute the destruction of Stratum VIA to Shoshenq I’s campaign. The erection of a victory stele in the city implies that the city would have had inhabitants to appreciate such an impressive work, yet the total destruction of this stratum and the settlement gap following it would imply that had Shoshenq I been responsible for this destruction, he would have erected his stele in an uninhabited city.

Therefore, it would seem that Shoshenq I’s campaign occurred in the Iron Age IIA rather than during the Iron Age I. Stratum VIA is ruled out due to four main considerations:

Shoshenq I’s campaign was intended to reestablish Egyptian hegemony in the region, made evident from the stele fragment. This being the case, he likely would have only destroyed the elite quarter of the city, or perhaps taken it peacefully (Finkelstein 2009: 121; regarding the possibility of a peaceful takeover see Finkelstein 2002: 122). Thus, Shoshenq I’s campaign to the north should not be attributed to Megiddo Stratum VIA, but rather to a later city in the Iron Age IIA (Ussishkin 1990: 73; Finkelstein 2011: 232).

- At least some of these destructions are radiocarbon dated to before the highest possible date for his reign

- the radiocarbon evidence indicates a gradual demise of these cities and not a single destructive event

- there was no reason for a pharaoh who was probably interested in re- establishing Egyptian rule in the area to devastate a fertile valley that was the bread basket of the entire country

- it is illogical that Sheshonq I would establish a stele in a deserted Megiddo (Finkelstein 2011: 232).

After ruling out destruction by both earthquake and the military campaign of Pharaoh

Shoshenq I, one must investigate the possibility of the Israelite expansion to the region

from the northern highlands. Indeed, this suggestion best fits the current set of data

available by both textual sources and archaeological excavations.

First of all, the data from radiocarbon studies “renders the earthquake and single

military campaign theories invalid,” as the dates provided by these samples suggest two

waves of destruction in the region rather than one (Finkelstein 2013: 1337). A series of

raids or the gradual expansion of the Israelites from the highlands better explains these

waves of destructions (Na’aman 2007: 402; Finkelstein 2011: 229; 2013: 1337).

Second, the later settlements at Megiddo support this reconstruction. The break in

material culture between the Iron Age I-IIA suggests that the population that resettled in

the city following Stratum VIA was a different people, most likely the Israelites who later

on established the Omride Kingdom in the region (Megiddo VA-IVB and its

contemporaries) (Finkelstein 2009: 122-123). This reconstruction still leaves room for

the campaign of Shoshenq I in the decades following the Israelite expansion, thus

allowing for a unified and harmonious historical reconstruction inclusive of all known

historical events from this period.

- from Krauwer (2016:13)

- Fig. 3.2 Plan of the

Stratum XIX Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

Plan of the Stratum XIX Temple

(after Loud 1948: Fig. 390; Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago).

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 3.1 Aerial view of

f Area J at the end of the 1996 season from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1

Aerial view of Area J at the end of the 1996 season; looking east.

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 31.3D - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3D

Figure 31.3D

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 31.3E - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3E

Figure 31.3E

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 31.3F - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3F

Figure 31.3F

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 40.1 - Extension

Fractures in Stone Wall of Level J-4 Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 3)

Figure 40.1

Figure 40.1

Wall 96/J/1 in Square H-10, looking east. Note fracture along the strike on the edge of the wall.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 3) - Fig. 2.28 - J-4 Temple

Collapse Layer from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.28

Figure 2.28

Square H/7 east section. Striated remains near the base of the section are Level J-4a squatter’s debris and temple collapse (see also Fig. 2.38). At left, Probe 06/J/099/PT003 reveals the bottom of Wall 00/J/21. Note phytolith level 08/J/185 in low baulk at right.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013) - Fig. 2.37 - Section from

Squares H–G/7–8, eastern section from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.37

Figure 2.37

Squares H–G/7–8, eastern section.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013) - Fig. 2.47 - Strike Fractures

in Temple 4040 from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.47

Figure 2.47

Strike fractures in Temple 4040 Wall 08/J/38.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

- Fig. 3.2 Plan of the

Stratum XIX Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2

Plan of the Stratum XIX Temple

(after Loud 1948: Fig. 390; Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago).

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 3.1 Aerial view of

f Area J at the end of the 1996 season from Finkelstein et al. (2000)

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1

Aerial view of Area J at the end of the 1996 season; looking east.

Finkelstein et al. (2000) - Fig. 31.3D - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3D

Figure 31.3D

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 31.3E - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3E

Figure 31.3E

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 31.3F - Fractured

Temple Walls from Marco et. al. (2006)

Figure 31.3F

Figure 31.3F

In Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d) as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f). The overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured

Marco et. al. (2006) - Fig. 40.1 - Extension

Fractures in Stone Wall of Level J-4 Temple from Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 3)

Figure 40.1

Figure 40.1

Wall 96/J/1 in Square H-10, looking east. Note fracture along the strike on the edge of the wall.

Finkelstein et al. (2013 Vol. 3) - Fig. 2.28 - J-4 Temple

Collapse Layer from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.28

Figure 2.28

Square H/7 east section. Striated remains near the base of the section are Level J-4a squatter’s debris and temple collapse (see also Fig. 2.38). At left, Probe 06/J/099/PT003 reveals the bottom of Wall 00/J/21. Note phytolith level 08/J/185 in low baulk at right.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013) - Fig. 2.37 - Section from

Squares H–G/7–8, eastern section from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.37

Figure 2.37

Squares H–G/7–8, eastern section.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013) - Fig. 2.47 - Strike Fractures

in Temple 4040 from Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

Figure 2.47

Figure 2.47

Strike fractures in Temple 4040 Wall 08/J/38.

Adams in Finkelstein et al. (2013)

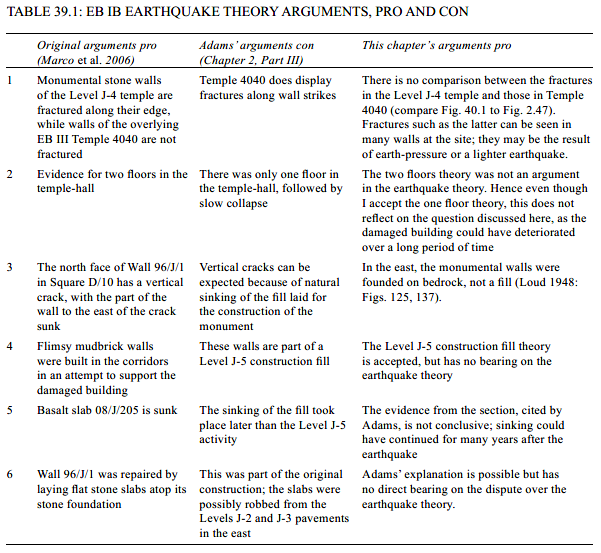

Marco et. al. (2006) reported that

in Area J, the monumental walls of the Level J-4 temple are fractured in several places along their strike (Fig. 31.3d)

as well as perpendicular to the strike (Figs. 31.3e-f)

while the overlying walls of the EB III temple 4050 are not fractured.

They attributed this to probable catastrophic horizontal shaking

and categorized this as an earthquake event that was

beyond doubt

. This archaeoseismic evidence is indeed compelling.

Israel Finkelstein in Adams et al. (2013 Vol. 3:1331) reports that

Adams in Adams et al. (2013 Vol. 3 Ch.3 Part III) argues against this interpretation attributing

abandonment of the temple in particular and Megiddo in general to socio-political change.

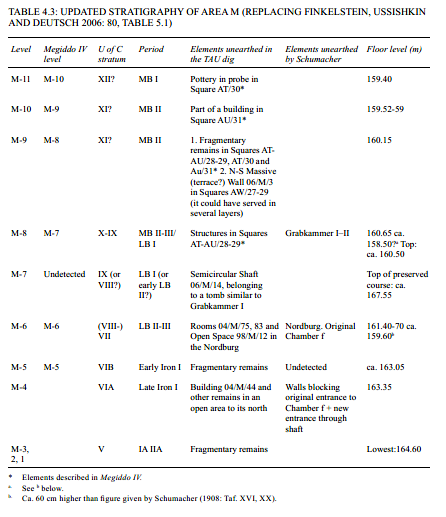

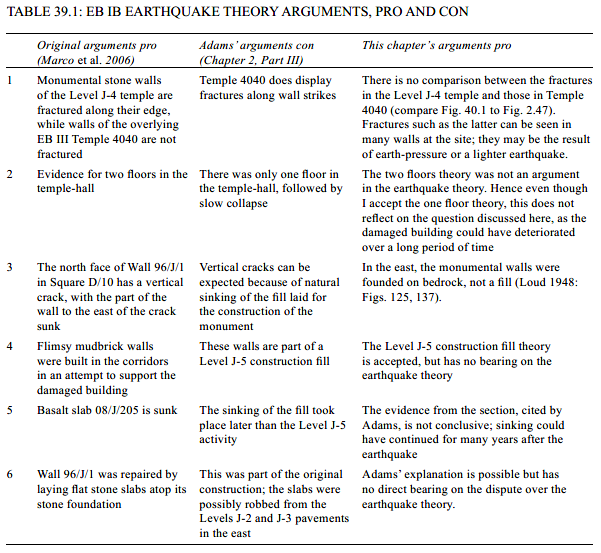

Israel Finkelstein in Adams et al. (2013 Vol. 3:1331) summarized Pro and Con arguments in the Table below while asserting that

an earthquake was likely responsible for the wall fractures.

Table 39.1

Table 39.1EB IB Earthquake Theory Arguments, Pro and Con

Israel Finkelstein in Adams et al. (2013 Vol. 3:1331)

A few years ago Finkelstein and Ussishkin (2003, 2006) offered a reinterpretation of the stratigraphy of the Level J-4 temple and the transition to the EB III based on the then-current understanding of two floors within the temple. As described above, however, what was previously identified as the lower floor is actually the construction fill for the temple platform. The later floor turned out to be a phytolith lens representing collapse and sporadic Phase J-4a activity within the temple.

There is evidence for only one phase of primary use of the temple – Level J-4. This phase was followed by a crisis period during which the temple was allowed to deteriorate. Within the corridors, Square D/10 showed evidence of water-washed mudbrick and other sorted debris over the Level J-4 bone accumulation in the corridors (96/J/096; Finkelstein and Ussishkin 2000b: 585). Within the sanctuary, there is evidence for numerous ephemeral hearths attesting to the temple’s continued sporadic use during this period.

A total of five owl pellets were discovered in Area J. The first two come from the corridors behind the temple sanctuary, which were used as bone favissae (94/J/81 and 96/J/21). Wapnish and Hesse indicated that owl pellets are typically found in areas where owls were nesting and that these roosts are typically found in spaces little used or deserted by humans (Wapnish and Hesse 2000: 444–445; see also Chapter 30).

Three additional owl pellets were identified within the temple sanctuary itself (in Loci 98/J/122, 08/J/142) in the 1998 and 2008 seasons Locus 98/J/122 yielded two pellets directly on the floor immediately west of the altar. Both were identified in situ. The fifth pellet came from the surface of the monumental basalt threshold (08/J/142). The entrance pellet was identified by the numerous small fauna bones recovered during sifting of earth within 5 cm of the basalt threshold 08/J/144 (identified in the field by Aharon Sasson).

While the owl pellets found within the corridors were not conclusive evidence of the abandonment of the temple, those within the sanctuary demonstrate unequivocally that owls roosted within the building where they regurgitated the bones of their prey, and that no one returned to clean up after them. Their location directly on the floor demonstrates that the building remained rarely visited as it began to collapse

In an effort to better understand the sequence of activity during the ‘crisis phase’, a portion of the 2008 season was dedicated to a detailed study of the 10–20 cm accumulation (Figs. 2.28, 2.37) in the Squares H/8–9 baulk, the Squares G–H/7+G–H/8 baulk and the Square J/7 western incision. To complement this approach, a sampling strategy was coordinated with Ruth Shahack-Gross. (The results of the micromorphological analysis of these samples appear in Part V of this chapter; RME numbers refer to these samples, see Table 2.8.)