Tell el-Mazar

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tell el-Mazar | Arabic | |

| Tell al-Mazar | Arabic |

Tell el-Mazar forms part of a complex of sites in the East Jordan Valley that were all occupied in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. The two nearest main sites of this complex, both of which have been excavated are Tell Deir Alla and Tell es-Sa’idiyeh. A bit further removed to the north are Pella and Tell Abu Kharaz. In between these main sites is a large number of smaller sites, all occupied in the Late Bronze and/or Iron Ages. This density of occupation testifies to the importance of the region. It was not only economically important because of its climate, but it was also a crossroads, connecting north and south, as well as east and west (van der Steen 2004:213-251). Towards the end of the Late Bronze Age an Egyptian trade route ran from Beth Shean towards the Amman Plain, crossing the river first by Pella, and later by Tell es-Sa’idiyeh. This route must have passed Tell Mazar, which was inhabited during the late Bronze Age, as shown by the large number of Late Bronze Age sherds that were found by successive surveys.

The excavator believes that at all times was the Tell connected to the main towns of the district in this part of the Jordan Valley, and dependent on the internal administrative organization of the district and the degree of security it provided. As a result the historical stratigraphy of the Tell is entwined with that of Tell Deir Alla and Tell es-Sa’idiyeh, of which it was a sister town. At the end of the Late Bronze Age settlement declined in the Jordan Valley, as it did elsewhere, but on most of the large sites settlement continued, or was resumed after a short break, albeit on a smaller scale.

Iron Age II saw the rise of the tribal kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Israel. The biblical tradition claims that Ammon became a kingdom before Israel, i.e. before the 10 th century. There are no external sources for this, either textual or archaeological, but settlement patterns suggest that the Amman plateau saw increased settlement during Iron Age I, prior to Cisjordan (Younker 1999:208). It has been suggested that large tribal confederations were in control of the region, and over time developed into tribal kingdoms (Labianca 1999; Younker 1999:208-09; van der Steen and Smelik 2007). Whether the Jordan Valley, the region dominated by Tell Mazar, Tell Deir Alla and Tell es-Sa’idiyeh was part of the Ammonite kingdom (and later the province of Ammon) is a matter of debate. Biblical tradition suggests that at the end of Iron Age II the western border of Ammon was the Jordan river. Various scholars on the other hand, considered the Wadi Zerqa to be the western border of the kingdom (MacDonald 1999:43 with references). Sauer suggests, on the basis of the material culture, that the Valley was eventually incorporated in the Ammonite polity (Sauer 1985:212). Herr (1992) defines the Ammonites as an ethnic or cultural group which was well defined in the Iron Age II, and extending into the Jordan valley as far north as Mazar, and possibly Tell es- Sa’idiyeh, but absent in Pella.

The material culture of Tell Deir Alla and Mazar is predominantly Ammonite (Groot 2011:96), although at Tell es-Sa’idiyeh, 6 km north of Mazar, this influence is much less, and at Pella it is missing altogether (Herr 1992:175) suggesting that Mazar was on the edge of a cultural region, and may have been part of the border territory.

Eventually the small tribal kingdoms of Ammon, Moab, Edom, Israel and Juda would be overrun by the rise of large empires from the North: the Neo-Assyrian, Neo- Babylonian and Persian empires, all of which used the Jordan Valley as a thoroughfare for their expeditions into the southern countries.

Tiglath-Pileser III (745-27) subjected Ammon and forced it to pay tribute. It became a vassal state, together with Moab and Edom. Neo-Assyrian influences can be found in the material culture of Tell Deir ‘Alla, Tell ‘Adliyyeh, Tell es-Sa’idiyeh and Tell Damiya. Tell Damiya was a Neo-Assyrian centre situated strategically on an east-west crossroad on the River Jordan (Petit 2009:187, 226). Hübner suggests that the Jordan Valley with the eastern foothills, although still culturally ‘Ammonite’, was turned into the separate province of Galaad (Gilead; Hübner 1992:189-90 with references). The vassal state of Ammon flourished in the 7th century2. The province of Gilead was home, among others, to the iron smelting industry around Mugharet el-Warde (Veldhuyzen and Rehren 2007). Hübner is adamant that this industry was never part of Ammon (Hübner 1992:150), which means that it must have been part of Gilead3.

Initially the Babylonian conquest did not significantly change the political map of the region. Gilead, which had been an Assyrian province, now became a Babylonian province. However, in 581 Ammon was stripped of its vassal status and also became a Babylonian province. The incorporation of Ammon as a province in the Babylonian empire coincided with a slow decline in the settled population and an increased nomadization of the population (Hübner 1992:210-11; Geraty et al 1987). Existing villages and towns became smaller, and some disappeared altogether. Nevertheless the large sites in the Jordan valley Deir ‘Alla, Mazar and Sa’idiyeh remained settled, as did some of the smaller sites, testifying to the continued importance of the region.

After the Persian conquest in the middle of the 5th century both Ammon and Gilead became Persian sub-provinces, part of the Satrapy ‘Beyond the River’. The Persian and Hellenistic periods in the region are still relatively unknown, but the settlement pattern, which continues from the previous period, shows the continued relative importance of the region.

2 Contra Petit who concludes that the late 7-6th century BC left

archaeologically hardly any traces of occupation, suggesting a more

nomadic lifestyle (Petit 2009:187)

3 However, Hübner wrote before the smelting site of Hammeh was

discovered. It is now clear that the iron industry flourished here from at

least the 9th century onwards, long before the Assyrian conquest and the

creation of the province of Gilead. It must therefore have been part of

the Ammonite kingdom.

“Mazar” means burial shrine, and the tell is named after the nearby burial shrine of Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, who was one of the ten original companions of the Prophet Muhammad, and a commander of his army.

The shrine is situated about 1.5 km east of the Tell, in the village that is named after it Mazar Abu Ubayda. It was first visited by John Lewis Burckhardt in 1812, who saw a small domed tomb surrounded by a few peasants’ huts, with a guardian (Burckhardt 1822:346).

Four years later James Silk Buckingham described the Mazar as follows: “a small village of huts, collected around a mosque, built over the tomb of some distinguished personage, who had given his name to the place. This Abu-el-Beady was said, according to the traditions preserved of him here, to have been a powerful sultan of Yemen, who died on this spot on his way from Arabia Felix to Damascus; but of whom no other particulars are known. The tomb and mosque appeared to be very ancient, and both were ornamented with a number of Arabic inscriptions in a square formed character. A large piece of green glass, weighing probably from three to four pounds, was placed in the wall near the door of entrance” (Buckingham 1825:12).

When Thomas Molyneux explored the river Jordan by boat in 1847, he ran into trouble at Abu Ubayda, which was at that time the boundary between the territories of the Beni Amr (to the north) and the Meshaleha to the south. Molyneux was exasperated by the extortionate protection fees the southern tribe demanded, and decided to ignore them, which proved to be a serious mistake. The expedition was robbed, and forced to flee back to Tiberias (Molyneux 1848:120-21).

Two years later Francis Lynch also explored the river by boat, and came past Abu Ubayda. He mentions the village, but without describing it (Lynch 1849:230).

Not one of these travellers seems to have noticed the large tell that dominated the landscape west of the village, and it was Nelson Glueck who first described it. Glueck both visited the tell, and observed it from the air. He describes it as a prominent hill, commanding a view of the Ghor in all directions. From the air Glueck noticed the outlines of a fortification wall encompassing the circumference of the top of the site. Glueck also remarked upon the vast quantities of pottery he found: “On the top and slope and around the base of Tell el- Mazar are very large quantities of LBII, Iron Age I-II sherds of all kinds, with a seeming predominance of lron Age II sherds. There were also some Roman and Byzantine sherds. With the exception of Tell Deir ‘Alla, no other site in the Jordan Valley that we examined produced more or larger pieces of Iron Age pottery than Tell el-Mazar” (Glueck 1949:302).

In later surveys the Tell figures more prominently, among them the survey by Henry de Contenson in 1953 and the Jordan Valley Survey (Ibrahim, Sauer and Yassine 1976,1988; site 103).

In recent years the small shrine of Abu Ubayda in the village has been replaced by a major monument and mosque, which dominates the small village (fig. 2).

The excavations at Tell Mazar have uncovered remains from the 11th century to the early Hellenistic period, although the Tell itself was occupied from the Middle Bronze Age onwards, as shown by the surface pottery. There are some tantalizing remains of even earlier pottery, which were found in the excavations at the edge of the Tell, of an Early Bronze IB jar (Cat. P116), and some possible Early Bronze I sherds in the layer below it.

The earliest excavated remains were on mound A, a smaller mound some 200m northeast of the main tell. Here a courtyard building was found, that has been interpreted as an open-court sanctuary. It is dated to the end of the 11th century, continuing into the first half of the next century. It consisted of a courtyard, with adjoining rooms, one of which was a small cella.

In the preceding period there had been a temple at nearby Deir Alla, which was destroyed in the 12th century. Franken considers it to be a local tribal sanctuary that played a role in the international Egyptian trade (Franken 1992, 2008; van der Steen 2004)1. After its destruction by a succession of earthquakes, and after the collapse of the international trade, the sanctuary seems to have been abandoned, at least until the 9th century.

Franken states that the numinous character of Deir Alla must have continued after the destruction of the temple. However, if the tribes that used to worship at Deir Alla no longer had access to the site, for political or other reasons, they would have needed an alternative place of worship. If a holy place becomes inaccessible, a place from which it is visible can become sacred by association (van der Steen, in press). This may be the origin of the Mazar Mound A sanctuary, which was in sight of Deir Alla. It is possible that the tribes that originally worshipped in Deir Alla created a new place of worship somewhat further north, much smaller, from where they could see the original holy place. The ‘cella’ of Mazar is different from that of Deir Alla, but the layout of the sanctuary as a whole, with a courtyard and service rooms adjoining the cella, is very similar.

On the main tell architecture has been found from the Assyrian period onwards.

Throughout the late Iron Age Tell Mazar has had a more than local significance, as can be seen from the substantial buildings that occupied the tell. This is partly due to the prominence of the tell itself, towering over its surroundings. Partly it may also have been due to its position in the valley. Mazar formed a chain with its sister sites Deir Alla to the south and Sa’idiyeh to the north, and their fates are often connected.

The earliest excavated areas (Stratum VI) revealed fragmentary but promising remains of substantial architecture, probably representing some kind of public building(s), the nature of which is unclear. What little pottery was found in context with these remains does not differ significantly from the pottery of the succeeding Stratum V, which is dated to the Assyrian period (end of the 8th century).

The region became a vassal state of Assyria during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727). There are traces of a violent destruction of Stratum VI (burnt remains, and layers of mudbrick rubble). Since the transition of Ammon into an Assyrian vassal state seems to have been peaceful, there are no historical events that can directly be related to this destruction.

The Balaam text at Deir Alla dates from the same time as Stratum VI, and it is likely that Deir Alla had a religious function. At Sa’idiyeh there were rows of houses, with evidence of weaving, possibly on an industrial scale (Pritchard 1985). Deir Alla Phase IX was destroyed by a violent earthquake in the second half of the 8th century. The region is prone to earthquakes, and it is by no means certain that this was the same destruction, but the scale of the destruction at Deir Alla makes it a distinct possibility the destruction of (parts of) Stratum VI can be attributed to the same natural disaster. Tell es-Sa’idiyeh was also destroyed in the same period.

Stratum V was built on top of the remains of Stratum VI. The building excavated on top of the tell was a large courtyard building, with rooms surrounding the courtyard (at least on the excavated southeast side) and a casemate outer wall. The building type has elements that are reminiscent of the Syro-Hittite bit hilani, such as the large central hall, and the double (in this case triple) outer walls.

Most of the remains found in and around the building date from the latest phases of use. The substantial architecture suggests that it was erected as a public building. However, most of the pottery and other artifacts found inside and around it, are indicative of domestic use. There is substantial evidence for cooking, weaving and other domestic activities, as well as for animal husbandry. It seems that at some point in its existence, the public function of the building became obsolete, and it was taken over by squatters or local farmers. Some narrow walls were built in the central courtyard, the guard room at the entrance of the building became a weavers’ workshop, and to the north of the building a small house was built, with an oven room in it. The beautiful Astarte Beer jug, that was found outside the guardroom on the pavement, may have been a remnant of the original function of the building. There are no indications about the original function of the building, apart from the casemate walls, which suggests either a defensive function, or reflects the volatile political situation of the region. The campaign of Sennacherib of 701, which was aimed at the rebellious Hezekia of Judah and largely fought in the Mediterranean coastal regions, may have had a wider impact, and included Mazar, or caused the occupants of the Mazar fortress to desert their stronghold. Whether the building was partially destroyed before the squatters moved in, is impossible to determine. A fire caused the end of the squatter occupation.

The pottery found in Stratum V suggests it is contemporaneous with Deir Alla Phase VII. Deir Alla Phase VII dates from the beginning of the 7th century and only existed for a relatively short period. It also seems to coincide with the presence of some heavy walls on the top of Tell es-Sa’idiyeh, which are found underneath the Persian residency on that site, and which still await further excavation to determine their function. Destruction struck at Deir Alla and at Mazar at more or less the same time.

Stratum IV was built on top of the remains of Stratum V, after a period of abandonment. The orientation of the building of Stratum IV is the same as that of the previous stratum, but the building’s layout is very different. It consisted of rows of rooms surrounding a central hall, south of a cobbled and plastered courtyard. The architecture of the building suggests a public, possibly an administrative function. The remains, which were mostly found in the central part of the building, were mostly domestic and related to storage, cooking and weaving. It had a monumental entrance on its east side.

At some point in its existence the building was expanded, marking the beginning of Stratum III. The central part was covered with a fill layer, which preserved the remains of the previous stratum, whilst creating a podium which made the central part of the new building stand out among its surroundings. The walls surrounding the podium were very heavy and buttressed, as they had to support the fill inside. The space inside these walls was reorganized. The monumental entrance on the east side remained in use, but two wings were added, on each side of the entrance.

Towards the end of its existence, the building seems to have undergone a change in function. Several rooms were added, and the large hall in the central part was divided into smaller rooms. The remains in most of the rooms, particularly the inner rooms and the two wings, indicate a largely domestic function. The southern wing seems to have been used as an abattoir, judging from the large amounts of cattle bones. There were some finds of a possibly administrative nature, such as several ostraca, and a stone weight.

The building of Stratum IV and its successor of Stratum III represent a long period of relative peace. There was no destruction at the end of Stratum IV, the function of the rebuilding in Stratum III was expansion, probably reflecting the growing importance of Mazar. The building was dubbed ‘the Palace Fort’ by the excavator, and interpreted as the seat of a governor of the region. It may have doubled as a garrison. In one of the rooms an ostracon was found, carrying the name of an Ammonite king, possibly Hissalel (Yassine 1988:87). Since Ammon was a vassal state of the Assyrian empire, the local governor would have been an Ammonite. The introduction of several new (but local) types of pottery (see Chapter Pottery) indicates a cultural shift towards a more upper class presence.

It is possible that the change in function in the last stages of the Stratum III building reflects larger political events. The creation of the Assyrian province of Gal’ad in 733 which included the Zerqa triangle with Mazar and Deir Alla (Hubner 1992:189) would have made a governor’s palace superfluous, and it would probably have been replaced with a garrison. That may have been the cause for the creation of the smaller rooms in the centre. Alternatively, it is possible that the Babylonian conquest was followed by a change in function of the fortress. Several finds in the rooms, such as cylinder seals, horse figurines, storage rooms, a central slaughter area and an arrow head, suggest that the function of the building was not purely domestic, but possibly housed a garrison of soldiers. How the large numbers of looms found in this stratum fit into this function is not clear, although it is possible that the soldiers lived in the building with their families.

Stratum IV-III coincides with Deir Alla Phase VI, which is interpreted as a village, possibly fortified (Groot 2011:96). The corresponding layers in Sa’idiyeh are still hidden below the Persian residency. It seems that the Mazar Palace Fort was the centre of government for the region in this period.

This period saw an expansion of international trade, with a number of major roads traversing the region. The major North-South route through Jordan was the King’s Highway, from which several east-west roads must have crossed the Jordan Valley towards the west. Another road ran through the Jordan Valley past Mazar and Deir Alla. The finds from Tell Mazar, particularly from the cemetery (Yassine 1984) but also pottery and objects from the mound itself, suggest prosperity and international contacts.

The building of Stratum III was burnt down in a heavy conflagration, which seems to have been sudden, because the inhabitants left many of their belongings behind. This suggests the building was not under siege, and the destruction has been ascribed to Nebuchadnezzar’s expedition in 582, which destroyed several other sites in the region such as Deir Alla, Adliyeh and Ammata.

After the fire and destruction the tell was deserted for a while. The occupation of Stratum II started with a levelling operation of the ruins of the previous stratum. The difference in height between the leveled ruins and the surrounding area was retained by a heavy stone wall. The buildings of Stratum II consisted of groups of rooms (‘units’) around a central courtyard. It could have been a common farmstead belonging to an extended family, but for several features. The leveling operation involving massive stone walls seems out of proportion with a purely domestic occupation. Also, there were a relatively large number of arrow heads found among the rubble. The Persian Period, in which Stratum II can be dated, saw a general decline in occupation in the region. Mazar belonged to the province of Ammon, which was part of the satrapy of ‘beyond the river’. Left to itself, the Jordan Valley tends to become the playground for local tribes, and tribal conflicts are common (van der Steen in press). Any settlers in the region would have to be prepared to defend themselves against attacks from local bands and tribes. It is possible that the platform created by the stone retaining walls was part of a defensive structure which has disappeared (it was found directly under topsoil, and in places on the surface of the tell, any superstructures having eroded away). This is supported by the number of arrow heads. There are no indications for a violent end to this stratum. It was probably deserted and left to fall into ruin.

During the Persian period the occupation of Deir Alla seems to have been rural, more or less like that of Mazar, while at Sa’idiyeh a more substantial government presence has been suggested by the excavator. Here a small fortress has been excavated, a substantial courtyard building with heavy walls.

It was built in the course of the Persian period, and seems to have remained in use (possibly by squatters only in the later phases, judging from the lack of finds) until well into the Hellenistic period.

The latest stratum, Stratum I, consists mainly of pits. Many of these were storage pits for grain and possibly animal feed (chaff), possibly for a nearby town or garrison. It was dated to the Hellenistic period on the basis of the pottery found. The absence of any defensive structures suggests that in this period the area was relatively safe. The excavator has suggested it may have been a central storage facility for nearby Tell Ammata. The pottery dates the stratum to the Early Hellenistic period, ending before the conquest of Alexander. At Deir Alla the Late Persian – Early Hellenistic period may have seen some substantial building, although nothing has been found of those with the exception of some heavy foundations. Apart from that, there were large numbers of pits, probably used for storage, like on Tell Mazar. Most conspicuous was a very large (diam >10m) pit on the top of the tell.

After the Tell was deserted, it was used as a burial site, until very recently. Tells and hills have always been popular burial sites.

In the four seasons of excavation, only a relatively small part of Tell Mazar has been excavated. Small trenches into the deeper layers, as well as the excavation on the edge of the tell (Areas P and Q), have shown that there are substantial periods of occupation, from as early as the Early Bronze Age. Future excavations may therefore bring to light a substantial part of the history of Mazar that is presently covered in soil, and substantiate, or even alter, the history of the region.

1 Recent excavations have shown that Deir Alla in the Late Bronze Age was a large village. That does not, of course, preclude the function of the temple as a tribal sanctuary, because tribes were rarely fully nomadic or fully settled, and the development of an international market area would in any case lead to increased settlement around the sanctuary

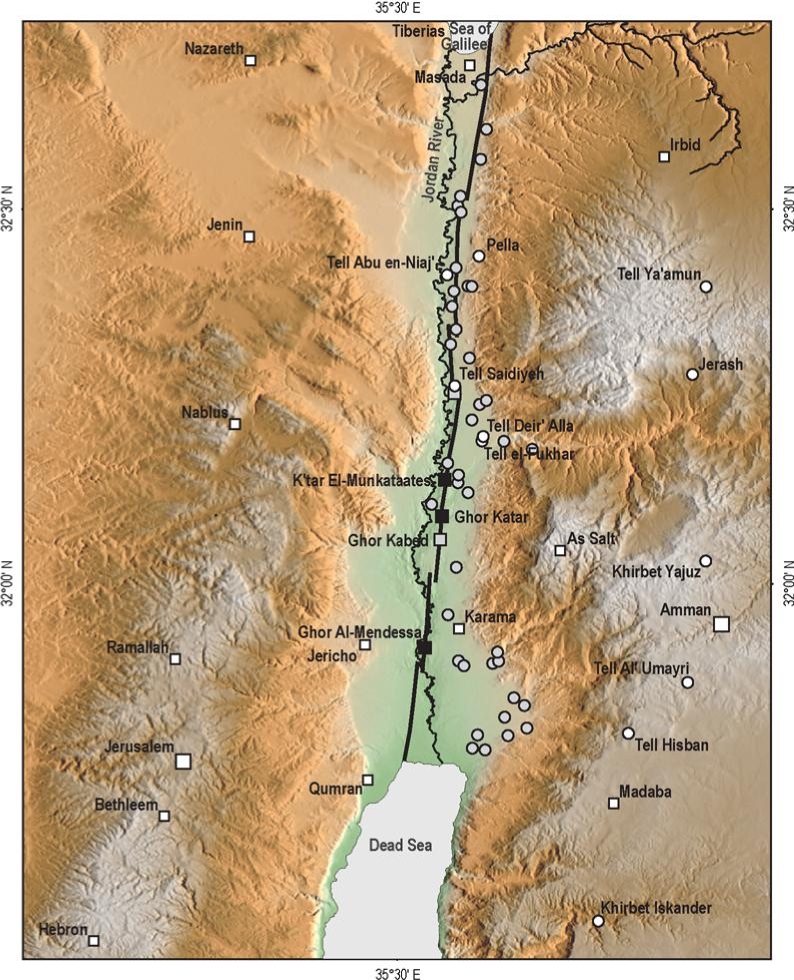

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location Map

Petit & Kafafi (2016) - Location Map from

Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Deir 'Alla region, based upon topographic map 1947

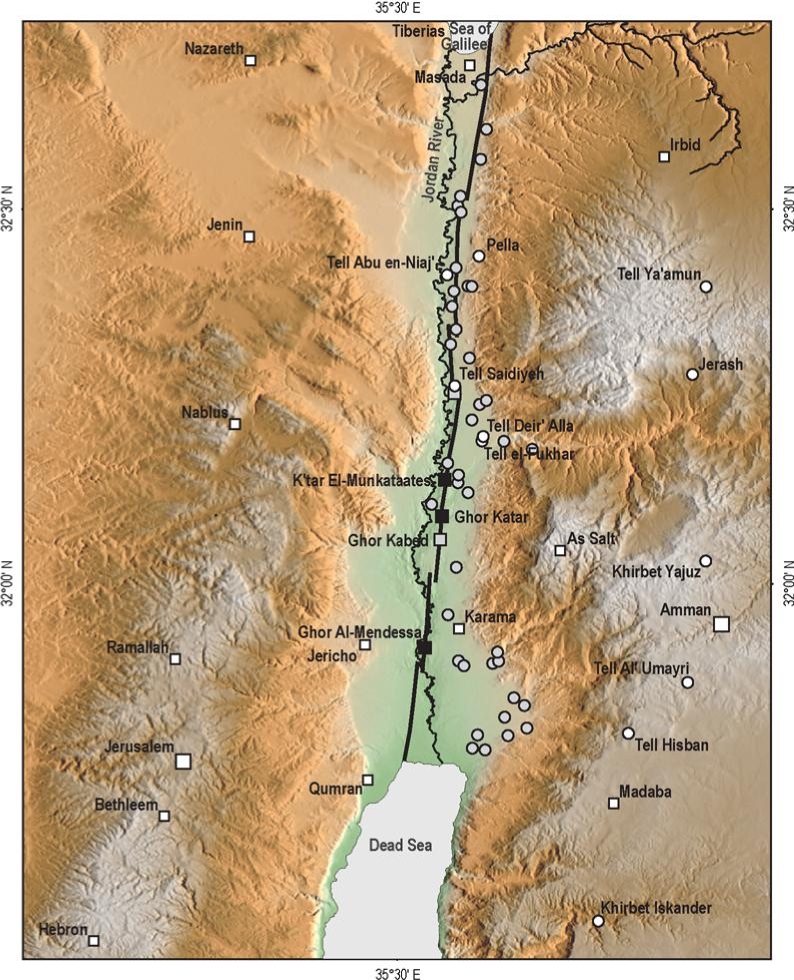

Van der Kooij (2006) - Jordan Valley Sites from

Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Archaeology of the Jordan Valley.

- White squares, main populated areas cited in historical documents

- white dots, archaeological sites visited and reappraised in this study

- gray dots are archaeological sites not studied here (lack of evidence and/or available literature) but of potential interest for future studies

- gray squares, paleoseismic sites

- black squares, geomorphological sites studied by Ferry et al. (2007)

Ferry et al. (2011)) - Fig. 2 Map of Iron Age I

sites in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Jordan Valley with Iron Age I sites mentioned in the thesis. The open circles are modern cities.

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 4.1 Map of sites

in central and northern Israel and Jordan from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Map of major archaeological and historical site in central and northern Israel and Jordan

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

- Location Map from

Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Deir 'Alla region, based upon topographic map 1947

Van der Kooij (2006) - Jordan Valley Sites from

Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Archaeology of the Jordan Valley.

- White squares, main populated areas cited in historical documents

- white dots, archaeological sites visited and reappraised in this study

- gray dots are archaeological sites not studied here (lack of evidence and/or available literature) but of potential interest for future studies

- gray squares, paleoseismic sites

- black squares, geomorphological sites studied by Ferry et al. (2007)

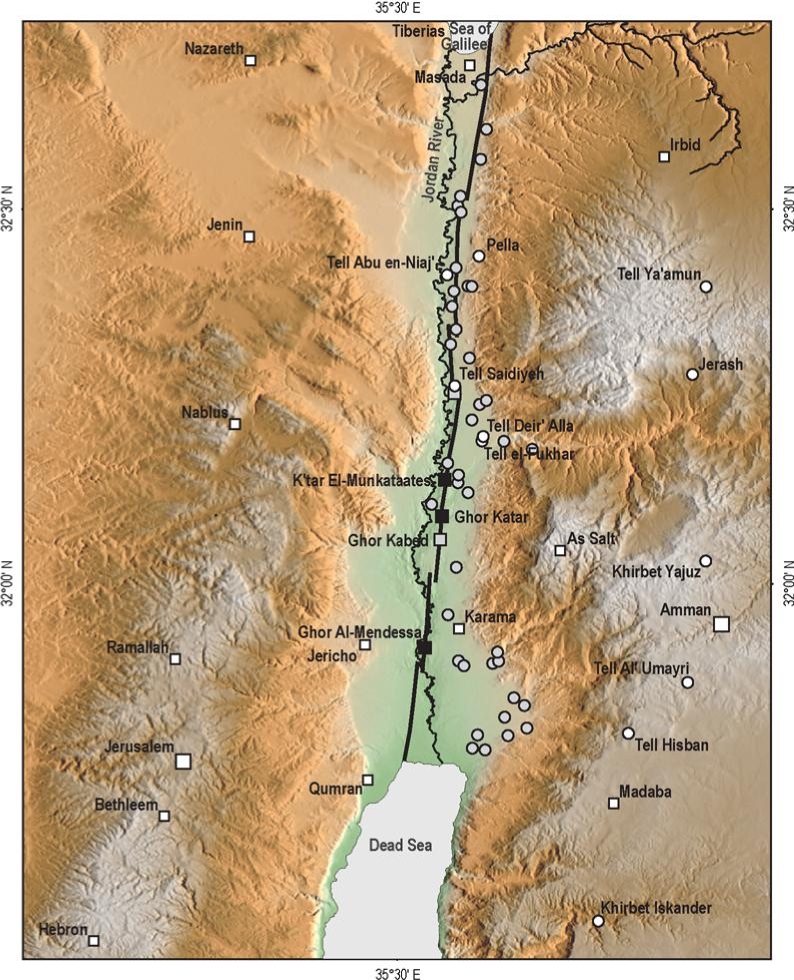

Ferry et al. (2011)) - Fig. 2 Map of Iron Age I

sites in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Jordan Valley with Iron Age I sites mentioned in the thesis. The open circles are modern cities.

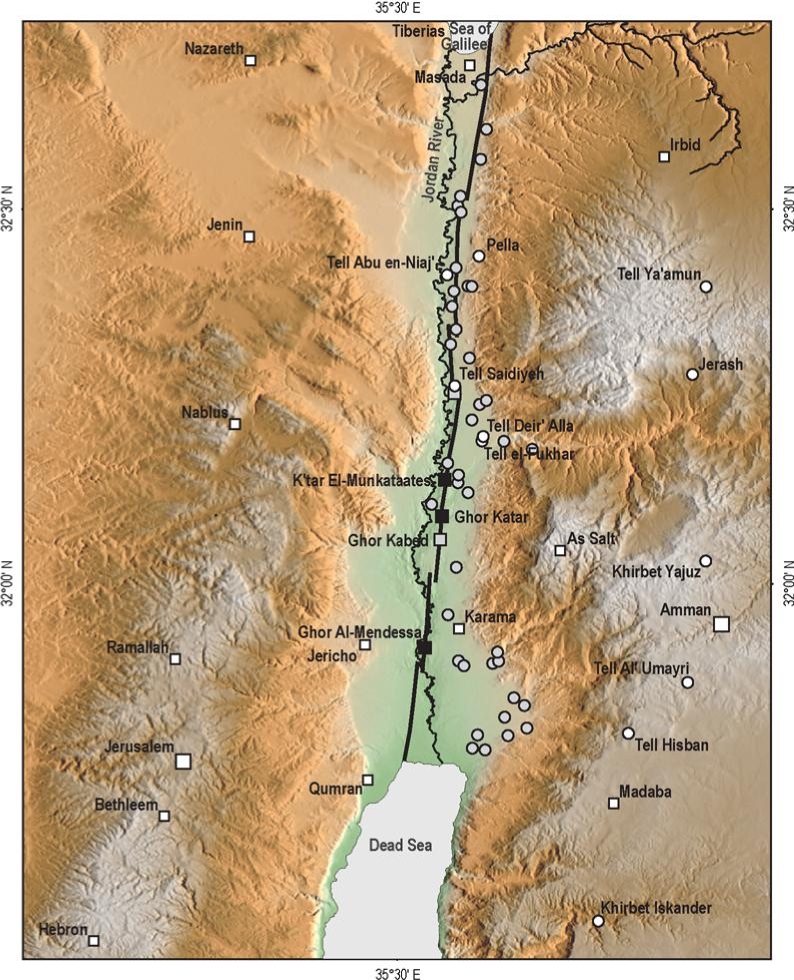

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 4.1 Map of sites

in central and northern Israel and Jordan from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Map of major archaeological and historical site in central and northern Israel and Jordan

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

- Fig. 30 Plan of excavated

area of Mound A from Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Figure 30

Figure 30

Excavated area of Mound A

Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

- Fig. 30 Plan of excavated

area of Mound A from Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Figure 30

Figure 30

Excavated area of Mound A

Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

- Fig. 3 Stratum VI

Topplan from Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Topplan Stratum VI

Yassine & van der Steen (2012) - Fig. 6 Stratum V

Topplan and Isometric View from Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Topplan (above) and isometric view (below) of Stratum V

Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

- Fig. 3 Stratum VI

Topplan from Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Topplan Stratum VI

Yassine & van der Steen (2012) - Fig. 6 Stratum V

Topplan and Isometric View from Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Topplan (above) and isometric view (below) of Stratum V

Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

- Fig. 35 Broken and likely

Fallen pottery in Room 101 of Mound A from Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Figure 35

Figure 35

Room 101

Yassine & van der Steen (2012) - Fig. 36 Broken and likely

Fallen pottery in Room 101 of Mound A from Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Figure 36

Figure 36

Room 101

Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

| Stratum | Period | Age | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| VI |

Comments

The oldest stratum for which a meaningful architectural

context could be reconstructed based on the excavated

area was Stratum V. Isolated loci from the preceding

strata have been excavated in only a few squares. They

could not be connected, but since they all immediately

preceded Stratum V, these excavated features have been

incorporated into Stratum VI. |

||

| V | 8th-7th century BCE? |

Comments

The destruction layer that covers this Stratum is burnt in

many places. There was obviously a violent destruction at

the end of the phase, but it seems that its administrative

function had ended before the destruction. |

|

| IV |

Comments

After the building of Stratum V was destroyed, there was

a period of abandonment, and possible squatter

occupation, during which the walls were allowed to

disintegrate, before a new complex was built on the tell.

The general orientation of this complex was the same as

that of Stratum V, so the visible wall remains were

probably still substantial. This might explain why so few

of the walls had stone foundations: old walls were reused

as foundations for the new ones. |

||

| III | This fire [at the end of Stratum III] has been associated with Nebuchadnezzar’s expedition into Ammon in 582 BC | 7th-6th centuries BCE |

Comments

Stratum III was an expansion of the building complex of

Stratum IV. The courtyard in the north of the excavated

area remained in use, as did the rooms to the west of this

area. However, the central part was rebuilt, on a platform

or podium, in order to make it stand out among the

surrounding structures, and around it, on a lower level,

were new buildings (fig 18 a,b. Fig. 18b shows show

stratum III overlies stratum IV). |

| II |

Comments

Stratum II was built over the burnt remains of the Stratum

III building, probably after some considerable time,

although the walls of the previous stratum must still have

been visible, since the walls of the new structures

followed the same general orientation (fig.25a,b). |

||

| I | Early Hellenistic - Abandonment of the site may have coincided with the rise of Alexander the Great. |

Comments

In practically every excavated area large numbers of pits

and silos were found (fig. 28,29). Most of these could not

be assigned to a certain period, as the level from which

they had been dug in had eroded away, or disturbed by

the modern graves (some of these graves may have been

contemporary with the graves of Mazar Abu Ubayda

cemetery). However, a large group of silo’s have been

dated to the Hellenistic period, on the basis of the

contents. |

The archaeological site of Mound A lies roughly 220 m. northwest of the tell proper and occupies a little over one and a half dunams, with a maximum extant height of 1.80m above the surrounding fields. This report covers the results of the 1977, 1978 and 1979 field seasons, conducted on behalf of Jordan University and the Department of Antiquities. The work was directed by Dr. Khair Yassine.

... There had been one major construction period of a building constructed on a very ambitious scale (about 624.00 sq.m) dated to the 11th- 10th century BC. No earlier buildings or constructions were found. This structure was almost rectangular in plan, measuring 24.00m from north to south and 12.60m from east to west (dimensions of mean outside exterior measurements). The building proper has a tripartite division (loci 100, 101 and 102), and an open courtyard (locus 103). The rooms and the courtyard were solidly constructed of mudbricks, forming walls with a width of ca. 1.20 m, except for the cross walls, which are 0.60m wide.

The whole structure was destroyed, and the rooms were filled up very rapidly after the collapse of the roof and mudbrick walls. The fallen roof sealed the contents on the floor of Room 101. The western wall was extant to a height of 1.25m above floor level, while the eastern walls were preserved only to a height of about 0.60 m. The destruction took place at the end of the second half of the 10th century BC, following which the mound suffered two major disturbances. The first occurred in the 5th century BC, when the mound was used as a graveyard; the tombs were dug through the destruction debris and into the occupational surface of the building. As a result, the structure’s stratification was disturbed. The second disturbance took place in modern times, when a subterranean house was built, and the removal of soil for building material has caused substantial disfiguration in Square D4. Despite this, considerable insight can be gained into the construction of the structure and its religious complexity.

Three rooms were aligned facing the open courtyard. Room 100, in the middle, measured 4.25m by 2.50 m. The room is entered through a doorway on the south side, measuring 0.97m in width. In a later phase one course of bricks formed a threshold at this entrance to prevent the couryard’s ash from being swept into the room.

One fragmented pottery bowl was found on the east side of the room.

The west room is 2.50m wide, the same as Room 100, and 4.60m long. It is approached through a door on the south side which measures ca 0.90m in width. Within the entranceway were found dark mudbricks intentionally blocking the entrance (fig 33).

... The room has a hard floor covered with mudbrick materials and charcoal. This deposit remained after the collapse of the brick walls and roof, the later presumably composed of earth and brushwood set on cross-beams which were laid across the width of the room. The same roofing system was found in Room 100.

The east room was entered through a doorway on the south side, measuring ca 0,90m in width. The room measured 2.50m by 2.70m. Despite the damage caused by the later graves, there is enough material and information to establish the nature of the room and its function. The walls were preserved to a height of about 0.60m. Room 101 contained a mass of pottery vessels (Fig 35,36).

The use of the room for storing pottery is readily intelligible from the excessive quantity of vessels found filling the whole room. The pottery deposit gave the impression of having fallen from shelves (Fig 35). No benches or other architectural features were found. Considering only the more or less easily recognizable and complete vessels, the group is comprised of two pedestalbowl chalices (Fig 40 K,L; 41 A,B), two globular flasks (Fig 40 A,B; 41 C), an undetermined number of storage jars, two kraters, (Fig. 40 G,H; 41:D,E), one cyclindrical incense stand with windows (Fig. 40 M) (only one half found), and a few small storage jars (Fig. 40 D,E,F,L; 41:F,G,H).

The pottery found on the floor of the room belongs to the last phase of the sanctuary, that is, towards the end of the 10th century BC. The several cult vessels testify to the ritual function of the building (e.g., the cylindrical incense burner and the chalices). From the above it is clear that each of the three rooms had served a different function, at least one of them (Room 101) as a storage room.

The courtyard was only partially excavated. The composition of the deposited material in every square dug in the courtyard seemed to be homogeneous, if not identical, displaying the same characteristics. The width of the courtyard is 16.0m; the length has not been determined, since the south side of the courtyard was eroded. However, on the basis of the existing west wall, we might assume that the length was 24.0m. The walls of the court were built of yellowish-red mudbricks, mixed with stone pebbles. The main entrance would have been on the south wall, but we cannot be sure, since this part was totally eroded. In view of the fact that the south side of the courtyard is facing the city (Tell el-Mazar proper) it would have been appropriate to communicate with the city through this side. Nonetheless, there was another doorway at the north-west corner of the courtyard.

| Stratum | Corresponding Deir Alla Phase | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| I | F | Ash deposit of dark gray colour. In texture it is very fine and very loose, mixed with great quantities of pottery sherds, animal bones, grain, brushwood and charcoal. The thickness was ca. 0.23-0.25m. The pottery corresponds to Tell Deir Alla Phase F. |

| II | F | Ash and brown clay material mixed with chunks of mudbrick, similar to Phase I, but forming a thinner (0.05m) deposit. Pottery corresponds to Tell Deir Alla Phase F. |

| III | G and H | Ash deposit of dark gray colour. In texture it is very fine and loose, mixed with great quantities of pottery sherds, animal bones, brushwood, and charcoal. Thickness ca 0.23-0.25 m. Pottery corresponds to Tell Deir Alla Phases G and H. |

| IV | J | Very thin deposit of reddish-yellow clay, broken in many places and thus linking Level III with Level V. Pottery corresponds to Tell Deir Alla Phase J. |

| V | J and K | Thick ash deposit of yellowish-gray ash of fine powdery texture but compressed, mixed with pottery sherds, animal bones (Fig. 38), a few grain seeds, and small pieces of charcoal. The total thickness was 0.24-0.30m. Pottery corresponds to Tell Deir Alla, Phases J and K. |

| VI | J and K | Burnt clay, dark gray to almost black in colour and rather coarse in texture. The pottery was broken, with some reconstructable vessels (Fig. 37). Phase VI marks the destruction level corresponding to that covering the floor level of Room 101. Pottery vessels were blackened by fire. |

| VII | This is the upper deposit, about 0.40-0.50m thick, composed solely of mudbrick material. Only a few pottery sherds from the later grave period (the 5th century BC). Phase VII is the deposit of the destroyed sanctuary walls. The great mass of bricks illustrates that the walls were of considerable height. |

From the condition and the context of the pottery sherds within the different phases (levels), in addition to the pottery pile in locus A1D5, it is suggested that the courtyard was used for the disposal of refuse resulting from ritual activities (cooking, sacrificing) which amounted to about 1760 cubic metres. Such deposits containing mainly ash would have required a rich source of fuel. The closest source would have been the trees from the Ajlun mountains and the bushes along the River Jordan.

The consistent practice of this large scale activity, lasting from the end of the 10th century BC, would point to a public function with a very set tradition prevailing the whole time. This sanctuary was not a place of popular worship, since the city (of Tell el-Mazar proper) revealed cultic objects in an architectural complex which might indicate that the city could have possessed at least one temple of its own, dedicated to one of its gods.

We might infer that the people were supplying, perhaps largely on their own initiative, services and goods in the form of agricultural holdings, including animal herds, grain, and drink.

The pottery of Phase A,B,C,D and E of Tell Deir Alla is not represented in the deposit of Phase I to VI from the courtyard. The closest parallel and frequencies of pottery types are well represented as of Phase F. The pottery sequence from the courtyard coincides with the sequence of Tell Deir Alla from Phases F to K.

Thus, we tentatively assume the earliest period for the construction of the sanctuary to have been the end of the 11th century6. The pottery vessels found in Room 101 and from Locus A1D5, the pottery pile, date the final phase of the sanctuary and its destruction. It is approximately contemporaneous with Tell Deir Alla I, K and J, Tell Beit Mirsim B3, Tell Abu Hawam III and Hazor XB. The destruction of the structure should be dated a little later than Beth Shemesh IIa and Megiddo Va. The material is similar to the bulk of material of Tomb 120 at Lachish, dated to 900 BC (Tufnell et al 1940 : 193-96). The termination of the sanctuary must therefore be dated to the late second half of the 10th century BC.

6 For the end of Phase E of Tell Deir Alla see Franken 1969:246-47

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

One major construction period dated from the 11th-10th centuries BCE was identified on Mound A which is located ~220 m northwest of Tell el-Mazar

(Yassine & van der Steen, 2012:17). These structures were destroyed and the rooms were

filled with debris as the mudbricks walls and roof collapsed. Although a 5th century BCE graveyard and a subterranean house built on the mound

in modern times disturbed some of the site's earlier stratigraphy, it was possible to date and characterize the destruction. The contents on the

floor of Room 101 - largely broken pottery that appear to have fallen - were sealed by roof collapse.

Yassine & van der Steen (2012:17) dated this destruction to the second half of the 10th century BC

based on pottery and comparisons to other Iron Age sites. The excavators did not suggest a reason for the destruction.

Yassine & van der Steen (2012:81-83) saw evidence of possible earthquake destruction in Stratum VI on the main mound.

On the main tell architecture has been found from the Assyrian period onwards.

... The earliest excavated areas (Stratum VI) revealed fragmentary but promising remains of substantial architecture, probably representing some kind of public building(s), the nature of which is unclear. What little pottery was found in context with these remains does not differ significantly from the pottery of the succeeding Stratum V, which is dated to the Assyrian period (end of the 8th century).

The region became a vassal state of Assyria during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727). There are traces of a violent destruction of Stratum VI (burnt remains, and layers of mudbrick rubble). Since the transition of Ammon into an Assyrian vassal state seems to have been peaceful, there are no historical events that can directly be related to this destruction.

The Balaam text at Deir Alla dates from the same time as Stratum VI, and it is likely that Deir Alla had a religious function. At Sa’idiyeh there were rows of houses, with evidence of weaving, possibly on an industrial scale (Pritchard 1985). Deir Alla Phase IX was destroyed by a violent earthquake in the second half of the 8th century. The region is prone to earthquakes, and it is by no means certain that this was the same destruction, but the scale of the destruction at Deir Alla makes it a distinct possibility the destruction of (parts of) Stratum VI can be attributed to the same natural disaster. Tell es-Sa’idiyeh was also destroyed in the same period.

Yassine & van der Steen (2012:81-83) saw evidence of possible earthquake destruction in Stratum VI on the main mound.

The pottery found in Stratum V suggests it is contemporaneous with Deir Alla Phase VII. Deir Alla Phase VII dates from the beginning of the 7th century and only existed for a relatively short period. It also seems to coincide with the presence of some heavy walls on the top of Tell es-Sa’idiyeh, which are found underneath the Persian residency on that site, and which still await further excavation to determine their function. Destruction struck at Deir Alla and at Mazar at more or less the same time.Yassine & van der Steen (2012:5-15) added

Stratum IV was built on top of the remains of Stratum V, after a period of abandonment.

The destruction layer that covers this Stratum is burnt in many places. There was obviously a violent destruction at the end of the phase, but it seems that its administrative function had ended before the destruction.Ibrahim and van der Kooij (1997:100-101) uncovered

Stratum V has been dated by the excavator to the 8th-7th century, a date that is borne out by the finds. The style of the building has been categorized by the excavator as of ‘Syro-Hittite inspiration’. Comparison of the pottery with that of Deir Alla (see the chapter on Pottery) suggests a date contemporaneous with Deir Alla Stratum VII.

a sudden collapse of buildings, with fire at placesin Deir Alla Stratum VII. They attributed this destruction to an earthquake and dated the destruction to the 7th or late 8th century BCE.

Yassine & van der Steen (2012:81-83) saw evidence of possible earthquake destruction in Stratum VI on the main mound.

The building of Stratum III was burnt down in a heavy conflagration, which seems to have been sudden, because the inhabitants left many of their belongings behind. This suggests the building was not under siege, and the destruction has been ascribed to Nebuchadnezzar’s expedition in 582 [BCE], which destroyed several other sites in the region such as Deir Alla, Adliyeh and Ammata.Yassine & van der Steen (2012:5-15) noted that

After the fire and destruction the tell was deserted for a while. The occupation of Stratum II started with a levelling operation of the ruins of the previous stratum.

the fire that destroyed Stratum III left its markin

the form of layers of burnt rubble and ash found in all squares. They added the following:

Stratum III ended with a fire that destroyed the building and left heavy layers of ash and burnt material over the whole excavated area. The building was burnt to the ground, and the walls that were still standing were baked hard by the heat of the fire. Remains of wooden furniture were found in several of the rooms, charred grain and burnt mudbrick were found in most spaces, inside as well as outside the building, covering it. Large numbers of vessels were found in the store rooms, as well as figurines of horses and other animals. This indicates that, while the inhabitants of the building managed to flee (no human remains were found in the building) they did not have time to remove any of the contents.

This fire has been associated with Nebuchadnezzar’s expedition into Ammon in 582 BC (see introduction). Thick layers of burned debris were also encountered at Tell Deir ‘Alla VI, Tell Adliyeh 15 and tell ‘Ammata 9 (Petit 2009:227), which have been ascribed to the same expedition and destruction.

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

|

| Collapsed Walls | Courtyard on Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

|

| Collapsed Roof | Room 101 on Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

|

| Broken and Fallen Pottery | Room 101 on Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

Fig. 35

Figure 35

Figure 35Room 101 Yassine & van der Steen (2012) Fig. 36

Figure 36

Figure 36Room 101 Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

|

Courtyard on Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 30 of Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 30 of Yassine & van der Steen (2012)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

|

|

| Collapsed Walls | Courtyard on Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

VIII + | |

| Collapsed Roof suggests displaced walls | Room 101 on Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

VII + | |

| Broken and Fallen Pottery | Room 101 on Mound A

Figure 30

Figure 30Excavated area of Mound A Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

Fig. 35

Figure 35

Figure 35Room 101 Yassine & van der Steen (2012) Fig. 36

Figure 36

Figure 36Room 101 Yassine & van der Steen (2012) |

|

VII + |

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master kmz file | various |