Damiya

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Damiya | Arabic | |

| Damieh | Arabic | |

| Damiyeh | Arabic | |

| Tall Damiyah | Arabic | |

| Adam Ha-ir | Hebrew |

Petit & Kafafi (2016:18) note that

Tall Damiyah, located

in the Central Jordan Valley, is identified by most scholars with the historical city of

Adama,

an important town destroyed by Pharaoh Shoshenq I

in the late tenth century B.C.E.

They also note that

Adama is mentioned in the Old Testament along with sites like Sodom and Gomorrah, and was ruled by a

king.

However, as pointed out by Petit & Kafafi (2016:18),

the minute dimensions of Tell Damiyah – only a few hectares at its greatest extent – make this identification and

description, at least at first sight, not very likely

.

Tell Damiyah is identified by most scholars as Adama, a place name mentioned in two sources. According to the Old Testament (e.g., Gen. 14:2; Joshua 3:16), Adama is attested as an important royal town near one of the few fords of the Jordan River and close to Zarethan, Sodom, and Gomorra. Although the existence of the last two cities remains obscure, the biblical city of Zarethan has most frequently been located at Tell es-Sa’idiyeh (fig. 1). Adama is also mentioned on the victory stele of Shoshenq I in Karnak. Ths topographic list from the late tenth century B.C.E. enumerates the names of annexed towns in the Southern Levant (Kitchen 1973: 293–300). One of these towns happens to be ỉdmỉ, which is generally accepted to be Adama. Together with neighboring sites like Succoth, Penuel, and Mahanaim – all of these places are said to be located in the area immediately north of Tell Damiyah – this apparent town was captured and possibly destroyed. However, looking at the size of Tell Damiyah, one could question its identification as Adama. On the Tell itself, there seems to be only space for a few houses, let alone a city with a royal palace, and recent excavations at the foot of the Tell has not yet revealed evidence of a lower city. Thus, either the identification supported by most scholars is wrong, or the character of the site was different to what biblical and Egyptian sources described.

The archaeological site of Tall Damiyah is situated in the Zor, directly south of the confluence of the Zarqa and the Jordan Rivers (Lat. 32.1040000915527; Lon. 35.5466003417969). The site is surrounded from three sides by Katar-hills (the Ras Zaqqum, the Sha'sha'a and the Damiyah Katar), and is 500 meters east of the Jordan River. Across the river, on the western side, are the Jiftik and the Marj en-Najeh, which belong to the Nablus district of Palestine. Tall Damiyah is considered to be the most southern settlement which has Iron Age occupation in the Jordan Valley, other than tells (or tails) which are situated in oases (e.g. Jericho, Tall Nimrin and Tall Hammam). The site covers an area of approximately 3 hectares at the base, and has relatively steep slopes all around, rising approximately 17 meters above today's ground level. It consists of two parts; an upper tell and a lower terrace which occupies the western and southern sides. The upper tall in particular occupies a strategic position, and today overlooks the Prince Muhammad (General Al-Linbi) Bridge across the Jordan River. In addition, it dominates the N-S road through the Jordan Valley and the E-W road which connects ancient Ammon with the Wadi Far`ah. This area is very fertile and currently irrigated for intensive farming.

Victor Guerin was the first to recognize the importance of Tall Damiyah (Guerin 1869:238¬40), although others, such as Irby and Mangles in 1818, William Lynch in 1848 and Charles van de Velde in 1851 must have directly passed the site during their travels (Irby and Mangles 1823: 325-26; Lynch 1855: 249-50; Van de Velde 1854: 321). John William McGarvey, who visited the site in 1879, mentioned the ruins of a building on its summit near the eastern end (1881:350). He was also one of the first scholars to equate Tall Damiyah with Adam(ah), a city mentioned several times in the Old Testament (e.g. Joshua 3:16, I Kings 7:46, II Chr. 4:17) and on the victory stele of Shoshenq I in Karnak. From 1880 onwards, the site was visited and surveyed many times (e.g. Albright 1926: 47; Glueck 1951: 329-31; Yassine et al. 1988: 191). The survey teams found pottery from the following major periods: LB II, Iron I, Iron II, Persian, Early Roman, Byzantine and Islamic.

Archaeological excavations were undertaken by Petit in 2004 and 2005 (Kaptijn et al. 2005; Petit et al. 2006; Petit 2009). During these first two seasons, the main objective was to rescue and document the archaeological remains uncovered by the bulldozer cut (Squares I-III). Archaeological research has continued from 2012 onwards.

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location Map

Petit & Kafafi (2016) - Location Map from

Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Deir 'Alla region, based upon topographic map 1947

Van der Kooij (2006) - Jordan Valley Sites from

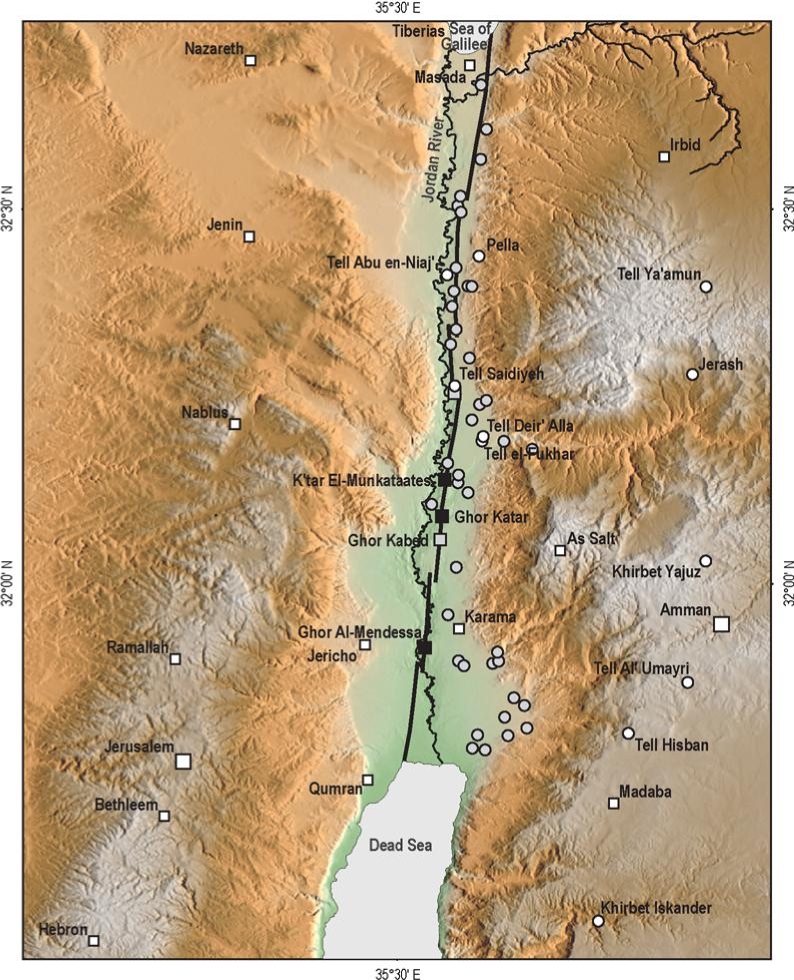

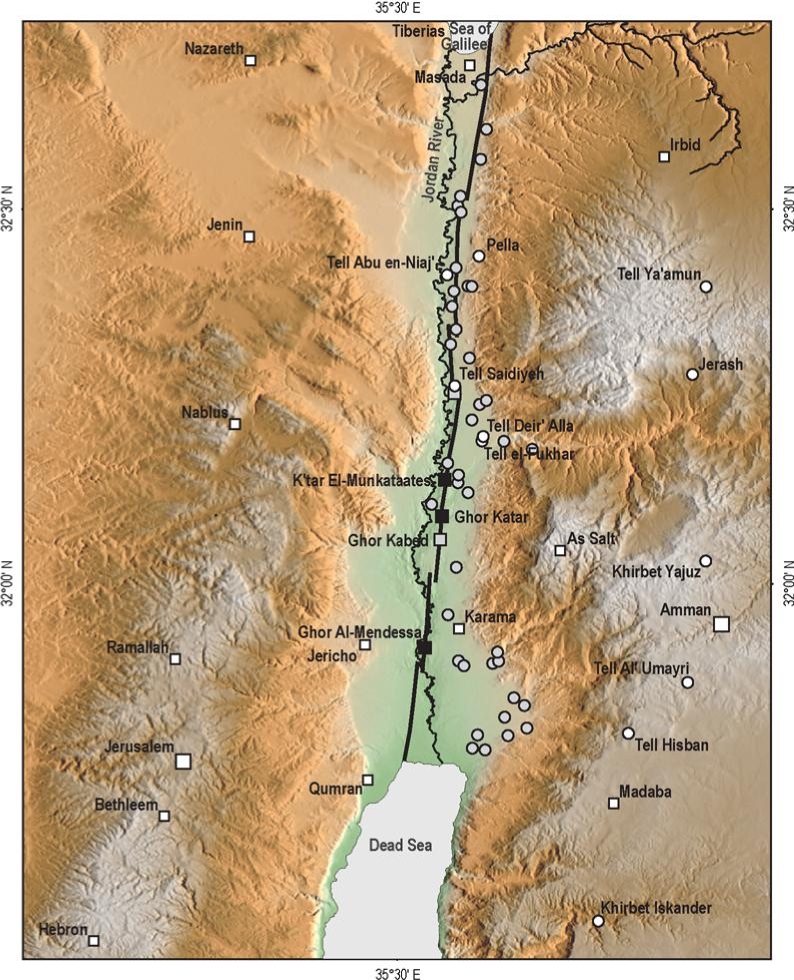

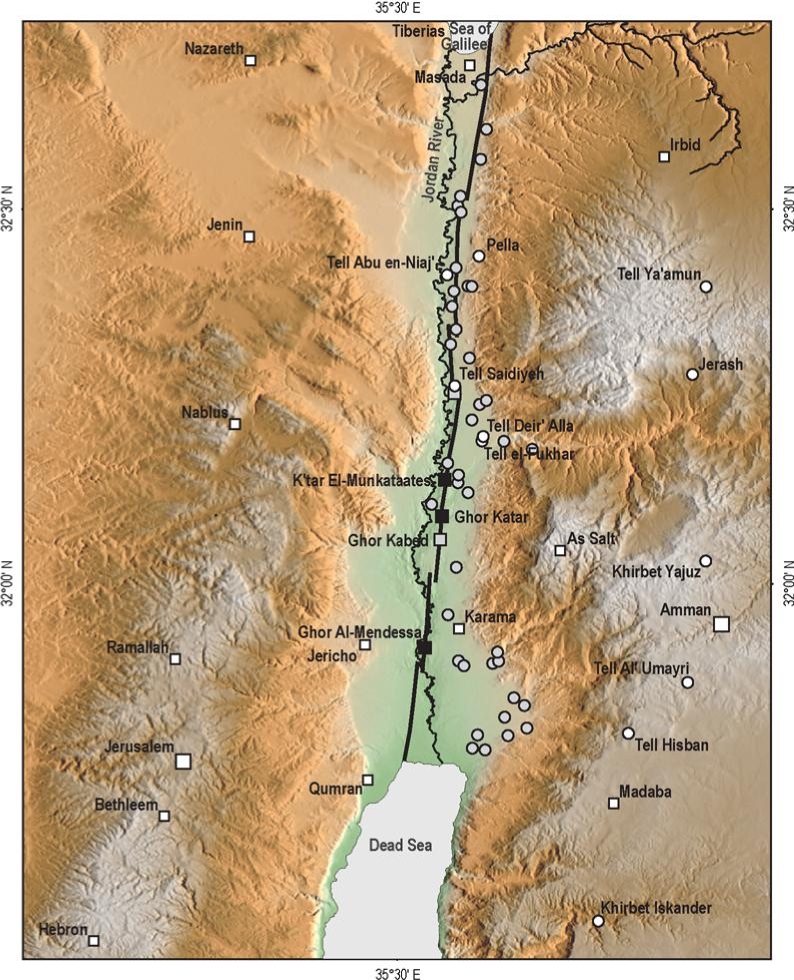

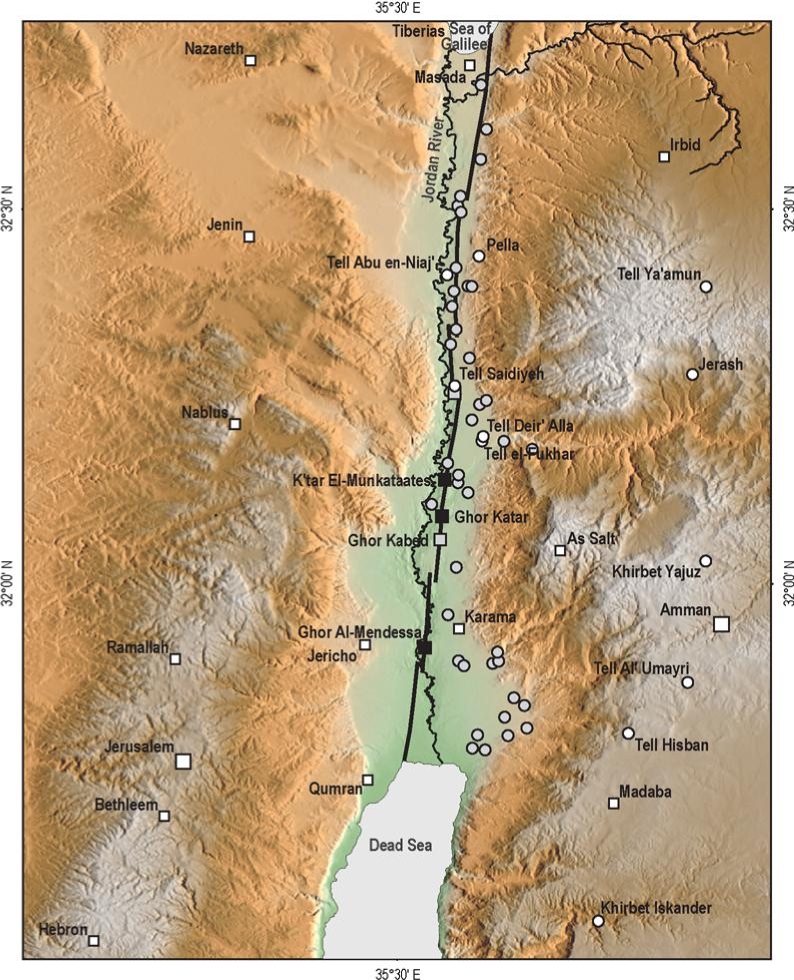

Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Archaeology of the Jordan Valley.

- White squares, main populated areas cited in historical documents

- white dots, archaeological sites visited and reappraised in this study

- gray dots are archaeological sites not studied here (lack of evidence and/or available literature) but of potential interest for future studies

- gray squares, paleoseismic sites

- black squares, geomorphological sites studied by Ferry et al. (2007)

Ferry et al. (2011)) - Fig. 2 Map of Iron Age I

sites in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Jordan Valley with Iron Age I sites mentioned in the thesis. The open circles are modern cities.

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 4.1 Map of sites

in central and northern Israel and Jordan from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Map of major archaeological and historical site in central and northern Israel and Jordan

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

- Location Map from

Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Deir 'Alla region, based upon topographic map 1947

Van der Kooij (2006) - Jordan Valley Sites from

Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Archaeology of the Jordan Valley.

- White squares, main populated areas cited in historical documents

- white dots, archaeological sites visited and reappraised in this study

- gray dots are archaeological sites not studied here (lack of evidence and/or available literature) but of potential interest for future studies

- gray squares, paleoseismic sites

- black squares, geomorphological sites studied by Ferry et al. (2007)

Ferry et al. (2011)) - Fig. 2 Map of Iron Age I

sites in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Jordan Valley with Iron Age I sites mentioned in the thesis. The open circles are modern cities.

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 4.1 Map of sites

in central and northern Israel and Jordan from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Map of major archaeological and historical site in central and northern Israel and Jordan

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

- Fig. 4 Site Plan with

excavation squares from Kafafi & Petit (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Site Plan with Location of Squares.

Kafafi & Petit (2018) - Fig. 2 Excavation Squares

of Areas A and B from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Contour map of Tell Damiyah with excavation areas

Drawing by Muwaffaq Bataineh

Petit & Kafafi (2016) - Fig. 4 Site Plan with

excavation squares from Petit et al. (2023)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Site plan with location of squares in red (dark gray in this black and white image)

Drawing by Muwaffaq Bataineh

Petit et al. (2023)

- Fig. 4 Site Plan with

excavation squares from Kafafi & Petit (2018)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Site Plan with Location of Squares.

Kafafi & Petit (2018) - Fig. 2 Excavation Squares

of Areas A and B from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Contour map of Tell Damiyah with excavation areas

Drawing by Muwaffaq Bataineh

Petit & Kafafi (2016) - Fig. 4 Site Plan with

excavation squares from Petit et al. (2023)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Site plan with location of squares in red (dark gray in this black and white image)

Drawing by Muwaffaq Bataineh

Petit et al. (2023)

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

- Fig. 4 Excavation squares

in Area A from Petit et al. (2023)

Figure 4 Inset

Figure 4 Inset

Location of squares in red (dark gray in this black and white image)

Drawing by Muwaffaq Bataineh

Petit et al. (2023)

- Fig. 4 Excavation squares

in Area A from Petit et al. (2023)

Figure 4 Inset

Figure 4 Inset

Location of squares in red (dark gray in this black and white image)

Drawing by Muwaffaq Bataineh

Petit et al. (2023)

- Fig. 3 Photo of Tall Dāmiyah

from Kafafi & Petit (2018)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Tall Dāmiyah (MEGA number: 2750, DAAHL Site number: 353200251).

Kafafi & Petit (2018) - Fig. 4 Photo of Tall Dāmiyah

from Petit & Kafafi (2019)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Tell Damiyah in 2018

Petit & Kafafi (2019) - Fig. 8 Fallen Roof Roller

from Kafafi & Petit (2018)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

White Plastered Wall and the Roof Roller from the 7th Century BC

Kafafi & Petit (2018) - Fig. 11 Fallen Roof Roller

from Petit (2013)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

A stone roof roller from roof debris in square VIII.

Petit (2013) - Fig. 1 Broken Pottery in

a storeroom from Petit & Kafafi (2020)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

One of the storage rooms in the east part of the late Iron Age complex

Petit & Kafafi (2020) - Fig. 2 Fragments of a

painted pithos (large storage container) on the floor from Petit & Kafafi (2020)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Fragments of a painted pithos [large storage container] on the floor of a rectangular freestanding building.

JW: This is the same photo as shown in Fig. 7 of Petit & Kafafi (2019)

Petit & Kafafi (2020) - Fig. 31 Crushed Pottery

bowl from Petit & Kafafi (2018)

Fig. 31

Fig. 31

A crushed pottery bowl found next to the remains of a mudbrick building. In the left corner are the remains of a tabun

(photo courtesy of Lucas Petit)

Petit & Kafafi (2018) - Fig. 9 Broken pottery

from Petit et al. (2023)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Restorable pottery in square XIX

photo Yousef al Zu'bi

Petit et al. (2023) - Fig. 6 Excavation work

in 2019 (broken pottery in foreground) from Petit et al. (2023)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Excavation work in 2019

photo Yousef al Zu'bi

Petit et al. (2023) - Paleo-Landslide Scar near

Damiya in Jordan

Photo taken in 1947 or 1948 of an old Landslide near the modern town of Damiya in Jordan

Photo taken in 1947 or 1948 of an old Landslide near the modern town of Damiya in Jordan

Unknown (forgotten) provenance

- Fig. 2 Sampling Photos

from al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Samples from the two sections in

- square I

- square VII

al Khasawneh et al. (2020) - Fig. 4 OSL Ages plot

from al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

OSL ages from the two sections shown as related to their depths. error bars represent total error.

al Khasawneh et al. (2020) - Table 1 14C ages

from al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

Table 1

Table 1

Relevant radiocarbon ages for five samples 14C ages to the highest probability, calibrated to BCE using OxCal v4.3.2 Ramsey (2017); InterCal atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. 2013).

al Khasawneh et al. (2020) - Table 3 OSL ages

from al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

Table 3

Table 3

Equivalent doses, total dose rate and calculated OSl ages.

al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

The most extensively excavated occupation phase on the summit (Stratum VII) dates provisionally to Iron Age IIc – around 700 B.C.E. – and consists of at least two mud brick buildings (fig. 5). Both structures were completely destroyed by a very intense fire, and a thick debris layer sealed off all utensils on the floors and surfaces. The reason for this seemingly site-wide destruction is unclear, but a similar event seems to have been detected at Tell Deir ‘Alla (Phase VII) and Tell al-Mazar (Phase V). The remains at Tell Damiyah were unfortunately heavily damaged in post Iron Age times, the latest disturbance being by a bulldozer in the early 2000’s. A few more buildings can be expected towards the north and west of these structures, but all together the settled area during Iron Age IIc is intriguingly small.

... A heavy, stone roller was found on top of a layer of roof debris inside the building.

... The figurines suggest that Tell Damiyah was a place of worship over a longer period during the fist millennium B.C.E. (Strata VIII–?).

There are traces of a few other buildings around the sanctuary. The remains of a second structure were found south of the street, although heavily damaged by a bulldozer in the early 2000’s (fig. 5). The structure consists of at least two rooms and was in use at the same time as the sanctuary. The mud brick walls were set up in shallow foundation trenches and plastered on the inside and outside with mud. This building suffered a destruction accompanied by fire as well.

... Based on the discoveries so far, Tell Damiyah seems to have been an interregional cultic center in the Jordan Valley during the Iron Age II, until its destruction in the early seventh century B.C.E.

Excavation work at the site, headed by the author, was conducted from the 30th of September until the 8th of November 2012. ... four excavation units were opened: three 5x5m squares and one 5x4m trench (fig. 3).

... Late Iron Age Occupation (Phase 9)

At the end of the 2012 season the excavation team reached undisturbed layers dated to the seventh century BC on a few locations. The excavation of the burials had taken most of the time and the destruction debris of phase 9 could only partly be investigated. The evidence equals the situation as was discovered in 2004 and 2005: a sudden conflagration accompanied by fire that gutted down the seventh century BC houses (Petit 2009a: 117-120). A spectacular find in 2004 was a clay bulla with cuneiform writing (Petit 2008; 2009a: 118, Fig. 8.38: 20). The minor excavation work in 2012 revealed this destruction debris and a collection of restorable pottery (fig. 10). A stone roof roller was discovered in square VIII (fig. 11). The rich Iron-Age finds recovered in the limited excavation area at Tall Dāmiyah are very promising for the future

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Results (Stratigraphy and Finds)

Excavations

Excavation work was carried out in 6 squares, numbered I, III, IV, VII, VIII and XII (Fig. 4). The preliminary results provided here are based on all excavation seasons (hence including data from the 2004, 2005, 2012 and 2013 seasons), although the 2014 season provided substantially more information, and solved several stratigraphic problems. The results are presented chronologically, commencing with the oldest occupation phase excavated so far. The excavators recognized several archaeological strata, which are all included in this report.

The oldest occupation remains were encountered in Squares I and III. They consist of thick deposits of occupation layers, with some complete pottery objects, and others which are restorable. The layers contain mud brick fragments, similar to some structures on the summit. The pottery, such as a complete bowl and small black juglet, can be dated to Iron Age IIC, somewhere around 700 BC. The presence of large clay loom weights suggest some textile production on the site (Fig. 6). One special find was a bone seal which depicted a lion.

The next occupation level, also from Squares I and III, encompasses the remains of several mud brick walls, oriented NW-SE which are extant in numerous occupation layers. The pottery, all fragmentary, can be dated exclusively to the 7th century BC. A possible oven associated with this level was found in Square III. Either contemporaneous or immediately on top of this phase was a thick deposit of courtyard layers; in 2014, most of the excavation in this area took place in Square IV (Fig. 7). Successive greyish floors, some of which were plastered, were interrupted by a number of stones.

These stones range in size, from medium to small unhewn, and are all river stones, sourced from the basins of both the Zarqa and Jordan Rivers. Fireplaces and post holes were identified in these layers. Possible associated remains of a mud brick structure, destroyed by a heavy conflagration, were discovered in 2012 (Square VII) and 2014 (Square VIII). However, this level was only reached in two small spots, and the shape of this building cannot be determined. At least two ovens “tabuns” were in use during this phase in Square XII. The pottery is consistent and clearly Iron Age IIC, including a number of Assyrian Palace Ware and Ammonite sherds. The next occupation phase, still dated to the 7th century BC, can be associated with an Assyrian presence. The discovery in 2004 of a clay bulla with Akkadian writing, and numerous Assyrian Palace Ware-sherds (in this and previous seasons) indicates increasing contact with the Neo-Assyrian Empire. But there was definitely contact with the Cypro-Phoenician coast and Egypt also.

At least two rectangular buildings separated by a small alley are located on the southeastern summit of Tall Dāmiyah; unfortunately, very little of the southern building has been preserved due to the bulldozer cut. The other building is rectangular, with a doorway in the SE-corner. The interior of the walls were white lime-plastered (Fig. 8), and a type of platform was situated against the western wall, which was also covered with plaster. It was difficult to get a complete plan of this building due to several later pits and burials. The pottery is clearly Iron Age IIC, some of which could be restored (in 2012 and 2013). A large stone roof roller was found on top of debris in the most northern building. The most important and intriguing finds were, however, several figurines and anthropomorphic jars.

North of the platform, near the western wall, four animal figurines (cf. Fig. 9) and a possible anthropomorphic jar statue was found. Two similar statues were found in Square IV in 2005 and 2012 (e.g. Petit 2009). In that same area, which is situated southeast of the plastered building, several other animal and human figurines were discovered. The courtyard layers may be contemporaneous with these finds. If this is the case, it can be assumed that the white plastered building had a cultic function. Further analyses on the objects and the stratigraphic situation must be carried out before this can be determined conclusively. However, it could be determined that both structures had been destroyed by fire, and a thick, burnt mud brick debris covered the floors of the rooms.

Some scattered occupation remains (pits and hearths) were found in the destroyed remains, after which the site was abandoned. Some NeoBabylonian finds, for example seals, indicate the presence of people during the late 7th and 6th century BC. The seals from Square IV reminded the excavators of the objects found at the Tall Mazar Cemetery, approximately 30 km to the north of the site (Yassine 1988). It is unclear if those finds could be associated with mud brick wall fragments at the summit, as their dating remained obscure.

The only remains from the 5th to the 2nd century BC were numerous large pits (see Petit 2014 for a possible explanation). These rounded architectural features were of two types: silos which were simply dug into settlement mound layers, and pits lined with mud bricks (Fig. 10)

... Archaeobotanical Research

(by Yotti van Deun)

... 14C Dates (export permission granted: October 2013)

A carbon sample was taken to the Netherlands for 14C analyses in 2013; it was studied by Dr. Rene Cappers from the University of Groningen. The sample contained Triticum Aestivum/Dureum, Hardeum vulgare ssp vulgare and grape. The sample was then dated by the 14C laboratory in Groningen (by Dr. Hans van der Plicht) to the end of the 8th century BC (calibrated).

... Discussion

The Tall Dāmiyah excavation results from 2014 have resulted in a more complete understanding of occupation during the late 8th and 7th centuries BC. Although heavily disturbed by Persian and Hellenistic pits, as well as by later burials and the bulldozer cut, the remains of two rectangular buildings, dated to the early 7th century BC, could be discerned. A clear relationship with the Neo-Assyrian Empire has been substantiated. However, Tall Dāmiyah’s precise role in this period has not been determined yet, hence further research is required. Was this building a type of trading post, or an Assyrian fort, as was previously thought? Alternatively, was Tall Dāmiyah a religious center, with the white-plastered building functioning as a temple? That the site had some cultic role is highly likely, as evidenced by the discoveries in the layer directly underneath the mud brick buildings; figurines and statues are reasonable arguments for assuming religious activity. Nevertheless, cook pots and loom weights were found in essentially contemporary layers, implying that, around 700 BC, Tall Dāmiyah was not merely either a temple or a trading colony. People were living on the site, hunting, farming, producing textiles and possibly trading.

Excavation work at Tall Dāmiyah continued in the autumn of 2015, between October 4 and November 5. ... The work was carried out in two areas: Area A on the summit (Squares IV, VIII, IX and XII) and Area B on the western lower terrace (Squares XIII and XIV) (Fig. 2).

A few skeletons from the Ottoman and Byzantine Period were excavated during this season, most of them discovered during the removal of the baulks. Two Ottoman graves were encountered and studied in Square VII; both were covered by stone slabs (Fig. 3). The discovery of an Ottoman pipe in the fill above these slabs in 2014 dates those burials to the latest occupation phase at Tall Dāmiyah. Over the five seasons, more than 50 skeletons have been carefully excavated and studied; results will be published in the nearby future.

During the 5th, 4th and 3rd century BC, the summit of Tall Dāmiyah was used for storage. Numerous pits cut through earlier Iron Age layers, sometimes more than 2 meters deep. Reports from previous seasons have described their outlook and content in detail (Petit 2013; Petit 2014; Kafafi and Petit 2018). During the 2015 season, two interesting finds were discovered in pits from this period. One was a single large fragment of a jar with an Aramaic ink inscription (Fig. 4), and the other was comprised of fragments of two storage jars, one of which could be reconstructed. Neither object has been discovered previously, and both provide additional information about the function and date of the pits.

Excavations have verified that, during the late Iron Age, the summit was inhabited by at least two buildings (Fig. 5). Whereas the most southern building seems to be domestic in nature, finds near and in the northern excavated structure suggest a cultic function (Kafafi and Petit 2018). In 2015, the archaeologists concentrated on the better preserved northern building and the street in between. The baulks were excavated and remaining debris on top of the floor was removed. By the end of the 2015-season, this level was reached in almost all squares.

The largest of the two buildings is rectangular in shape, oriented east-west, and has a doorway in the central part of the long southern wall. It was built on the top of a layer of artificial fill. At a few places, older wall remains were used as foundations, and one of these stumps acted as a division wall between the eastern and western part of the large room. In this rectangular building, all inner walls and installations were coated with white lime plaster. The inner dimensions are ca. 10.6 m in length and 4.2 m in width, and the building is considered large compared to contemporaneous structures at other sites in the vicinity. The roof was made of wooden beams, covered with smaller branches, reeds and packed clay. A heavy, stone roller was found on top of a layer of roof debris inside the building. Two mudbrick installations were found; one against the western wall and one in the north-eastern corner. The remains of the latter are difficult to interpret, due to its location close to the present surface. The western platform, probably the primary offering installation, was stepped, and plastered with lime (Petit and Kafafi 2016).

Several pottery stands and figurines, both of horses and females, were discovered inside and outside the building, and cultic activities can be assumed. The excellent condition of the figurines and the remains of two anthropomorphic statues are unique objects that have only a few parallels (Petit 2009b). Moreover, a clay bulla with cuneiform signs (found in 2004), Assyrian Palace Ware, a few Egyptian objects and Cypro-Phoenician and Ammonite pottery sherds, indicate relationships with the Jordanian Highland, Lebanon, Mesopotamia and Egypt. The head of an anthropomorphic statue (Fig. 6) was discovered near the northern wall, together with two animal skulls carefully placed on the walking surface.

Three other complete female figurines were uncovered in street-layers towards the southeast of the main building (Fig. 7). These objects were probably used during an earlier stage, implying that Tall Dāmiyah had a cultic function during large parts of the Iron Age. The co-directors suggest that Tall Dāmiyah was a significant and international religious centre during the late Iron Ages, along two major trade routes and close to one of the few fords crossing the Jordan River (Petit and Kafafi 2016).

The identification of Adama in biblical and Egyptian sources as an important town (Petit and Kafafi 2016), does not fit the situation found at Tall Dāmiyah, a small settlement mound with space for only a few buildings. Either the identification is wrong, or the remains of the town must be located elsewhere; for example, at the foot of the ‘acropolis’. Two squares were opened at the elevated south-western foot of Tall Dāmiyah (Fig. 2). Historical photographs suggest that it is part of a peninsula of white Qatar material that connect Tall Dāmiyah with the eastern Qatar hills.

Several graves and pits were discovered. The pits were circular and in almost all cases bell-shaped. They were filled with debris, some of which was mudbrick fragments. The pottery was a mixture of several occupation periods at Tall Dāmiyah; the presence of Byzantine pottery suggests that the pits were dug during or after this period. The graves must also have been post-Byzantine in date, based on similar reasoning. There were no funerary objects, and the skeletons were not buried according to the Islamic tradition.

All these features cut through a somewhat puzzling block of very regular white, black and yellowish layers (Fig. 8). Most of the material seems to be the result of some kind of industrial activity using intense heat. No structures have been detected yet, but the presence of burnt mudbrick suggest that some buildings were standing in the vicinity. Only fragmentary pottery with a mixed character was found. Coarse tempered pottery sherds might suggest an Islamic date, but in the lower ash layers, an increase in Late Bronze Age sherds was encountered, among them fragments of Cypriot milk bowls. The colourful accumulation of ash layers has, however, an identical parallel only a few kilometres to the north (Steiner 2008: Fig. 9). At Tall Abū Sarbuṭ similar layers were discovered between 1988 and 1992 dated to the Ayyubid/Mamluk period (De Haas et al. 1989; 1992; Steiner 2008). Although archaeobotanical research could not confirm the idea that sugar cane was processed, the excavators of Tall Abū Sarbuṭ believe the layers are the result of largescale burning, which took place somewhere else on the site (Steiner 2008: 165). Although the situation at Tall Dāmiyah equals these findings, future investigations should bring more information about the date and function of the layers. A natural sand deposit was reached below the ash layers, containing no material culture.

The excavation results of 2015 at Tall Dāmiyah have resulted in a better picture of the occupation during the late 8th and 7th century BC, as well as of the occupation remains at the foot of the settlement mound. Although heavily disturbed by Persian and Hellenistic pits, as well as later burials, the remains of two rectangular buildings on the summit, dated to the Late Iron Age, were further investigated. A clear relationship existed with the NeoAssyrian Empire, as well as with Ammon and the western areas. However, the role Tall Dāmiyah played in this period is still unknown, and needs further research. Was this building some sort of trading post, or an Assyrian fort, as was previously thought (Petit 2009a)? Or was Tall Dāmiyah a religious centre with the white-plastered building functioning as a sanctuary? The material culture especially, such as the complete figurines, statues and animal skulls, are strong evidence to assume religious activities at the site. However, in contemporary layers, especially in and around the southern building, cooking pots and loom weights were found, implying that around 700 BC, Tall Dāmiyah was more than just a sanctuary. At least in the southern building, people were living, hunting, farming, producing textiles and possibly trading.

Excavations in 2016 were carried out in three squares on the summit and aimed at investigating the southwestern corner of the sanctuary, unravelling its relationship with a domestic building located to the south, and studying older occupation phases. The area southwest of the sanctuary was unfortunately heavily disturbed by later burials and pits, making it hard to add new information to the already existing plan (Petit and Kafafi 2016: Figure 5). It is, however, clear from results encountered during previous seasons that this area was part of a street or courtyard between the sanctuary and the southern domestic building. Part of it was most likely roofed since several clay loom weights were encountered on the surface in 2016 (Fig. 32). The complete difference of the inventories of the two buildings is intriguing. It is suggested here that the southern building was primarily used as a living area, whereas the main rectangular building on the summit was intended for cultic purposes. Some of the finds from this phase, such as an Iron Age I figurine, advocate that Tall Damiyah was also used as a cultic place before Iron Age IIC.

An important aim of the 2016 field season was to investigate occupational remains below the phase of the sanctuary, especially in the southern square. The uncovered courtyard layers with several tabuns point to a domestic function, at least of this part of the site. Most of the finds in these layers were extremely fragmented due to frequent trampling.

Below these series of courtyard layers, a fragment of a mudbrick structure appeared that suffered a major conflagration. The wall and associated finds, such as a typical Iron Age II bowl, were dated to the 8th century B.C. (Fig. 31). Excavations of these earlier levels will be resumed in 2018.

In the autumn of 2018, the RMO and the Jordanian Yarmouk University organized the eighth excavation season at Tell Damiyah. This time most attention was paid to the layers beneath the sanctuary of 700 BC. Due to the strategic and special location of the site, the archaeologists suspected that Tell Damiyah had also been built earlier, i.e. in the early eighth century BC, had a religious function. Beneath the sanctuary, the archaeologists found the remains of an older, rectangular building. The walls were wide and made of square clay bricks. Unlike the later sanctuary, this structure had a main entrance on the north side. On the floor were the shards of a gigantic earthenware storage vessel with a diameter of more than one meter (fig. 7 - same photo as Fig. 2 of Petit & Kafafi, 2020). The red and black painting, mainly animal and plant motifs, is very similar to the decoration on a jar found in a shrine in the south of Israel. More research needs to be done on this building, but it is likely that Tell Damiyah was indeed used for a long time as a religious center for travelers and traders.

Excavations at Tall Damiyah were resumed during the falls of 2018 and 2019. These field seasons had two aims: to investigate the role of Tall Damiyah during earlier phases and to determine the extent of the Iron Age IIC sanctuary. In order to reach the second goal, the Jordanian-Dutch team opened several squares north of the main sanctuary building. First considered to be a freestanding construction, this turned out to be part of an extensive complex that had covered large parts of the summit. Not only was the main cultic room with the two altars destroyed by fire, the newly discovered rooms also showed traces of burning. Unfortunately, many graves and Persian-Hellenistic pits had wreaked havoc on these Iron Age layers, destroying much of the original floor deposits. Nevertheless, the team was able to uncover three additional rooms and a possible courtyard. Two of the rooms were in use for storage (Fig. 1). Numerous large kraters filled with burnt organic material, such as barley, were found in these rooms, preserved considerably well under a thick burnt debris layer. Other items, such as metal sickles and knives, suggest that the few occupants of Tall Damiyah were not only storing food but also harvesting. It is to be investigated whether this surplus was a donation of worshippers, was used for feeding visitors, or was a stockpile for the inhabitants to overcome arid periods. Much of the evidence point to a function as a caravanserai, where traders and travelers could eat, sleep, and worship.

During the 2018 season, the main aim was to investigate the role of Tall Damiyah during the Iron Age IIB and early IIC. Earlier evidence of cultic behavior was expected, following the assumption that the place had a religious significance over a longer period. Under the previously mentioned sanctuary, a freestanding building with thick, mud-brick walls was encountered. Although not burnt, collapse debris suggest some sort of destruction, although the team could not exclude deliberate dismantling. On the floor of this building, sherds of a large pithos were found, painted with a “tree of life” and two bulls or zebus (Fig. 2). A series of block-shaped pyramids forms the lower scene. Heavily fragmented and cut by a later pit, only part of the vessel was preserved. The closest parallel seems to be the pithos found in a temple context at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud. East of the building at Tall Damiyah stands a burnt mud-brick platform surrounded by ash lenses, and, farther to the south, several female figurines, most of them complete, were discarded in street levels. It seems at this stage safe to suggest that this earlier building also had a cultic function. Intriguing for the team is the clear distinction between the figurines found in this occupation phase (females) and those found in the later sanctuary (equids). It is proposed here that those figurines resemble the worshippers and not a deity. During the later phase, the Jordan Valley suffered a major arid period and the main group that visited Tall Damiyah were traders and travelers, those people associated with equids. In the earlier period the site was also used by sedentary occupants from nearby settlements with other intentions and thus other types of offerings.

- Fig. 2 Sampling Photos

from al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Samples from the two sections in

- square I

- square VII

al Khasawneh et al. (2020) - Fig. 4 OSL Ages plot

from al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

OSL ages from the two sections shown as related to their depths. error bars represent total error.

al Khasawneh et al. (2020) - Table 1 14C ages

from al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

Table 1

Table 1

Relevant radiocarbon ages for five samples 14C ages to the highest probability, calibrated to BCE using OxCal v4.3.2 Ramsey (2017); InterCal atmospheric curve (Reimer et al. 2013).

al Khasawneh et al. (2020) - Table 3 OSL ages

from al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

Table 3

Table 3

Equivalent doses, total dose rate and calculated OSl ages.

al Khasawneh et al. (2020)

In this study, we investigate quartz-based luminescence optical dating of Iron Age deposits at the archaeological site of Tell Damiyah in the Jordan valley. Ten samples, taken from different occupation layers from two different excavation areas, proved to have good luminescence characteristics (fast-component dominated, dose recovery ratio 1.032 ± 0.010, n=24). The optical ages are completely consistent with both available 14C ages and ages based on stylistic elements; it appears that this material was fully reset at deposition, although it is recognised that the agreement with age control is somewhat dependent on the assumed field water content of the samples. Further comparison with different OSL signals from feldspar, or investigations based on dose distributions from individual grains would be desirable to independently confirm the resetting of this material. It is concluded that the sediments of Tell Damiyah are very suitable for luminescence dating. Despite the relatively large associated age uncertainties of between 5 and 10%, OSL at tell sites has the potential to provide ages for material very difficult to date by conventional methods, and to identify reworked mixtures of older artifacts in a younger depositional setting.

Tell Damiyah is located ~500 m east of the Jordan River in the Zor region and is surrounded by the Katar Hills (Figure 1). Tell Damiyah is an exceptional archaeological site for the Central Jordan valley; it is one of the few which show evidence of continuous occupation during the Iron Ages (1200–600 BCE) (Petit and Kafafi 2016). Other sites, such as the nearby Tell Deir ‘Alla, reveal numerous occupational gaps, e.g. in the 10th and 8th century BCE (van der Kooij 2001). These periods without anthropogenic activity are simultaneous with dry climate stages, and it is argued elsewhere that the occupational pattern in the central Jordan Valley is closely related to these environmental factors (Petit 2009). Iron Age sites in this area are located mainly along major routes such as the North-South road through the Jordan Valley (Figure 1) and especially along the East-West road between ancient Ammon and the Wadi Far’ah. Tell Damiyah seems to have been a central point on these routes, close to one of the few fords across the Jordan River. Recent excavation results suggest that the apparently continuous occupation history of Tell Damiyah had much to do with a cultic function of this site. The small settlement seems to have remained occupied even during periods of harsh climate and after destructive earthquakes (Petit and Kafafi 2016, 2018; Kafafi and Petit 2018).

Excavations at Tell Damiyah are divided into a lower (at the western foot of the Tell) and an upper site (the summit of the Tell), together measuring about 3 ha. The upper site rises 17 m above the present surface and this is where most archaeological work has been carried out (Kafafi and Petit 2018; Petit and Kafafi 2018). Excavations began in 2004, as a reaction to destructive bulldozer cutting on the southern summit. The seventh season of excavation was carried out in October 2016 as a joint Jordanian-Dutch project under the directorship of Zeidan Kafafi of the Yarmouk University and Lucas Petit of the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities. Investigations took place in three areas on the southeastern summit of the Tell.

The prime discovery at Tell Damiyah was two mud brick buildings that had been completely destroyed by a very intense fire in around 700 BCE. The largest of the two buildings, with inner dimensions of ca. 11 × 4 m, was interpreted as a sanctuary with two mud brick platforms. Several cultic items were found, such as horses and females (Petit and Kafafi 2016), within and in front of this building. The other structure, located more to the south, was a domestic building. This important phase was dated by pottery and by 14C to ~800 BCE. During the 2016 seasons older layers were excavated that were dated stylistically to the 8th century BCE. After the sanctuary was destroyed, Tell Damiyah was apparently only lightly occupied until the 6th century BCE. Evidence for more recent occupation depends on storage pits from the Persian and Hellenistic times and two cemeteries dated to the Byzantine and Ottoman periods (available 14C ages are summarized in Table 1, after calibration to BCE using OxCal v4.3.2 Ramsey [2017]; InterCal atmospheric curve [Reimer et al. 2013]). OSL samples were collected from two sections in two different excavation squares, the newly excavated north section of square I and the south section of square VII (Figure 2). Both sections represent occupational layers from the Late Iron Age. Samples were collected by driving light-tight tubes into the faces of the sections. All samples were taken from units chosen to be as locally homogeneous as possible. Four samples were taken from discrete layers in the section in square I; these layers were subsequently interpreted at the end of the excavation season as follows (based on the excavation reports of Petit and Kafafi 2018 and Kafafi and Petit 2018):

- the upper sample (D1), 70 cm below the excavation surface (a previous bulldozer cutting), was taken from an occupation layer contemporary with the oldest sample taken from square VII (see below) and placed in the 8th century BCE (Stratum VIII).

- The second and third samples (D2 and D3) were taken from older occupation or courtyard layers also associated with stratum VIII.

- The lowest sample (D4) came from stratum IX deposited in the late 9th century BCE.

- sample (D5), closest to the modern surface, was taken from wash and occupation layers from the very late Iron Age, most likely around 600 BCE (Stratum IV).

- The second and third samples (D6 and D7) came both from occupation layers and debris of Stratum V, dated provisionally to the second half of the 7th century BCE.

- The fourth and fifth samples (D8 and D9) are associated with a sanctuary from around 700 BCE (Stratum VII).

- The oldest sample (D10) came from the occupation phase below the sanctuary, dated by archaeological finds to the 8th century BCE (Stratum VIII).

Calculated equivalent doses and ages from the two profiles are listed in Table 3. Random uncertainties (σr) are based primarily on OSL and gamma ray counting statistics, and OSL curve fitting (Duller 2007). The systematic uncertainties (σsys), shared across all samples, originate from gamma spectrometry calibration, beta source calibration and water content estimates.

The two sets of OSL ages range from 2.50 to 2.96 ka (Figure 4). The average age of the two OSL samples taken from Phase VII and attributed to the sanctuary structure is 2.82 ± 0.17 ka, indistinguishable from the average of the 14C ages from the same unit, of 2.80 ± 0.02 ka (n=4) cal BP.

Phases IV, V, VIII, and IX have no direct radiometric age control, but the archaeological estimates of age are 2.65, 2.65, 2.85, and 2.85 ka, respectively, based on stylistic characteristics (Petit and Kafafi 2016) as discussed above. The estimated age ranges are given in Table 3 (based on the description in the previous section, “Archaeological Context and Sampling,” and the table provided by Petit and Kafafi [2016: 19]).

Phase IV corresponds to OSL sample D5 with an age 2.76 ± 0.16 ka. The average OSL age for samples (D6, D7) that match phase V is 2.45 ± 0.13 ka. Four OSL samples were taken from Phase VIII (average is 2.74 ± 0.17 ka, n=4). Finally, one sample from phase IX gave an age of 2.86 ± 0.17 ka.

The luminescence characteristics of quartz extracted from these geo-archaeological sediments are very satisfactory. The OSL signal is dominated by the fast-component, and when used with a SAR protocol, it shows good recycling (0.971 ± 0.009; n=292) and low recuperation (2.0 ± 0.4% of the natural signal; n=292). The dose recovery ratio of 1.032 ± 0.010 (n=24) indicates that our chosen protocol is able to accurately measure a known dose given before any prior thermal treatment. Thus we have no reason to doubt the accuracy of our measured doses. The resulting OSL ages (Table 3) for each unit are, on average, in excellent agreement with expectations (OSL age /expected age = 0.99 ± 0.01; n=5), with 4 out of 5 expected ages lying within the 66% confidence interval of the corresponding OSL age. The largest deviation between OSL and expectation is 8% for Phase V (OSL 2.45 ± 0.11 ka compared with an expected age of 2.65 ka); in this case the expected age still lies within the 95% confidence interval of the OSL age.

However, it must be acknowledged that this agreement is to some degree fortuitous. The observed water content of the samples was, on average 9.5 ± 1.2% (n=10) of saturation. These samples were taken from exposed south and north facing sections, in a semi-arid environment. As a result, the sediment must have dried out to some degree, and the measured average water content must underestimate the present-day water content of sediment buried even a few metres further inside the Tell deposits. On the other hand, the Tell rises up to 17 m above the local valley floor (these samples were taken in the upper part of the site), and so must always have been well drained. Based on these considerations, we assumed that the buried water content was most likely to have been around 20% of saturation; we then used the observed water content to put a lower bound on our uncertainties, by assuming it lies at a probability of 95%. Similarly, it seems very unlikely that the water content was ever higher than 30%, and so we took 20 ± 5% as the assumed average lifetime fraction of saturation. For these samples, the effect of increasing our assumed water content by 1% would be to increase the age by about 1%. Thus, had we (incorrectly) used the observed field water content, our ages would be ~10% younger, and had we used the very unlikely assumption of 30% of saturation, the ages would be 10% older.

If we normalize each sample (and its associated random uncertainty) to the expected age, and neglect uncertainties on the expected age, then the over-dispersion in the ratios is 4.5%. This is not large and suggests that either all samples are equally poorly bleached, and at the same time suffer from some systematic uncertainty that largely compensates for this poor bleaching, or that the samples are well bleached, and unaccounted systematic uncertainties are negligible. We consider the latter the most likely, but acknowledge that it would be desirable to test this assumption by e.g. comparison with feldspar age (Murray et al. 2015; Thomsen et al. 2016), or by examining single grain age distributions (Feathers et al. 2006; Bateman et al. 2007; Arnold and Roberts 2009).

Nevertheless, these results confirm the suitability of these Tell sediments for luminescence dating. The typical uncertainty is ± 130 yr, to be compared with corresponding uncertainties on 14C ages of between 15 and 45 yr (based on 25% of the 95% range in calibrated ages). On the other hand, OSL is being used to date an event (deposition) and material (sediment) that cannot be dated directly by 14C. Clearly there are many circumstances where even the larger uncertainties of OSL dating will be useful in dating otherwise undatable material or in resolving ambiguities in typology.

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

The most extensively excavated occupation phase on the summit (Stratum VII) dates provisionally to Iron Age IIc – around 700 B.C.E. – and consists of at least two mud brick buildings (fig. 5). Both structures were completely destroyed by a very intense fire, and a thick debris layer sealed off all utensils on the floors and surfaces. The reason for this seemingly site-wide destruction is unclear, but a similar event seems to have been detected at Tell Deir ‘Alla (Phase VII) and Tell al-Mazar (Phase V). The remains at Tell Damiyah were unfortunately heavily damaged in post Iron Age times, the latest disturbance being by a bulldozer in the early 2000’s. A few more buildings can be expected towards the north and west of these structures, but all together the settled area during Iron Age IIc is intriguingly small.

... A heavy, stone roller was found on top of a layer of roof debris inside the building.

... The figurines suggest that Tell Damiyah was a place of worship over a longer period during the fist millennium B.C.E. (Strata VIII–?).

There are traces of a few other buildings around the sanctuary. The remains of a second structure were found south of the street, although heavily damaged by a bulldozer in the early 2000’s (fig. 5). The structure consists of at least two rooms and was in use at the same time as the sanctuary. The mud brick walls were set up in shallow foundation trenches and plastered on the inside and outside with mud. This building suffered a destruction accompanied by fire as well.

... Based on the discoveries so far, Tell Damiyah seems to have been an interregional cultic center in the Jordan Valley during the Iron Age II, until its destruction in the early seventh century B.C.E.

Excavation work at the site, headed by the author, was conducted from the 30th of September until the 8th of November 2012. ... four excavation units were opened: three 5x5m squares and one 5x4m trench (fig. 3).

... Late Iron Age Occupation (Phase 9)

At the end of the 2012 season the excavation team reached undisturbed layers dated to the seventh century BC on a few locations. The excavation of the burials had taken most of the time and the destruction debris of phase 9 could only partly be investigated. The evidence equals the situation as was discovered in 2004 and 2005: a sudden conflagration accompanied by fire that gutted down the seventh century BC houses (Petit 2009a: 117-120). A spectacular find in 2004 was a clay bulla with cuneiform writing (Petit 2008; 2009a: 118, Fig. 8.38: 20). The minor excavation work in 2012 revealed this destruction debris and a collection of restorable pottery (fig. 10). A stone roof roller was discovered in square VIII (fig. 11). The rich Iron-Age finds recovered in the limited excavation area at Tall Dāmiyah are very promising for the future

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

- Fig. 5 Iron Age IIc

occupation (Stratum VII) with excavation squares from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Top plan of the Iron Age IIc occupation (Stratum VII) at Tell Damiyah

Drawing by Lucas Petit

Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Results (Stratigraphy and Finds)

Excavations

Excavation work was carried out in 6 squares, numbered I, III, IV, VII, VIII and XII (Fig. 4). The preliminary results provided here are based on all excavation seasons (hence including data from the 2004, 2005, 2012 and 2013 seasons), although the 2014 season provided substantially more information, and solved several stratigraphic problems. The results are presented chronologically, commencing with the oldest occupation phase excavated so far. The excavators recognized several archaeological strata, which are all included in this report.

The oldest occupation remains were encountered in Squares I and III. They consist of thick deposits of occupation layers, with some complete pottery objects, and others which are restorable. The layers contain mud brick fragments, similar to some structures on the summit. The pottery, such as a complete bowl and small black juglet, can be dated to Iron Age IIC, somewhere around 700 BC. The presence of large clay loom weights suggest some textile production on the site (Fig. 6). One special find was a bone seal which depicted a lion.

The next occupation level, also from Squares I and III, encompasses the remains of several mud brick walls, oriented NW-SE which are extant in numerous occupation layers. The pottery, all fragmentary, can be dated exclusively to the 7th century BC. A possible oven associated with this level was found in Square III. Either contemporaneous or immediately on top of this phase was a thick deposit of courtyard layers; in 2014, most of the excavation in this area took place in Square IV (Fig. 7). Successive greyish floors, some of which were plastered, were interrupted by a number of stones.

These stones range in size, from medium to small unhewn, and are all river stones, sourced from the basins of both the Zarqa and Jordan Rivers. Fireplaces and post holes were identified in these layers. Possible associated remains of a mud brick structure, destroyed by a heavy conflagration, were discovered in 2012 (Square VII) and 2014 (Square VIII). However, this level was only reached in two small spots, and the shape of this building cannot be determined. At least two ovens “tabuns” were in use during this phase in Square XII. The pottery is consistent and clearly Iron Age IIC, including a number of Assyrian Palace Ware and Ammonite sherds. The next occupation phase, still dated to the 7th century BC, can be associated with an Assyrian presence. The discovery in 2004 of a clay bulla with Akkadian writing, and numerous Assyrian Palace Ware-sherds (in this and previous seasons) indicates increasing contact with the Neo-Assyrian Empire. But there was definitely contact with the Cypro-Phoenician coast and Egypt also.

At least two rectangular buildings separated by a small alley are located on the southeastern summit of Tall Dāmiyah; unfortunately, very little of the southern building has been preserved due to the bulldozer cut. The other building is rectangular, with a doorway in the SE-corner. The interior of the walls were white lime-plastered (Fig. 8), and a type of platform was situated against the western wall, which was also covered with plaster. It was difficult to get a complete plan of this building due to several later pits and burials. The pottery is clearly Iron Age IIC, some of which could be restored (in 2012 and 2013). A large stone roof roller was found on top of debris in the most northern building. The most important and intriguing finds were, however, several figurines and anthropomorphic jars.

North of the platform, near the western wall, four animal figurines (cf. Fig. 9) and a possible anthropomorphic jar statue was found. Two similar statues were found in Square IV in 2005 and 2012 (e.g. Petit 2009). In that same area, which is situated southeast of the plastered building, several other animal and human figurines were discovered. The courtyard layers may be contemporaneous with these finds. If this is the case, it can be assumed that the white plastered building had a cultic function. Further analyses on the objects and the stratigraphic situation must be carried out before this can be determined conclusively. However, it could be determined that both structures had been destroyed by fire, and a thick, burnt mud brick debris covered the floors of the rooms.

Some scattered occupation remains (pits and hearths) were found in the destroyed remains, after which the site was abandoned. Some NeoBabylonian finds, for example seals, indicate the presence of people during the late 7th and 6th century BC. The seals from Square IV reminded the excavators of the objects found at the Tall Mazar Cemetery, approximately 30 km to the north of the site (Yassine 1988). It is unclear if those finds could be associated with mud brick wall fragments at the summit, as their dating remained obscure.

The only remains from the 5th to the 2nd century BC were numerous large pits (see Petit 2014 for a possible explanation). These rounded architectural features were of two types: silos which were simply dug into settlement mound layers, and pits lined with mud bricks (Fig. 10)

... Archaeobotanical Research

(by Yotti van Deun)

... 14C Dates (export permission granted: October 2013)

A carbon sample was taken to the Netherlands for 14C analyses in 2013; it was studied by Dr. Rene Cappers from the University of Groningen. The sample contained Triticum Aestivum/Dureum, Hardeum vulgare ssp vulgare and grape. The sample was then dated by the 14C laboratory in Groningen (by Dr. Hans van der Plicht) to the end of the 8th century BC (calibrated).

... Discussion

The Tall Dāmiyah excavation results from 2014 have resulted in a more complete understanding of occupation during the late 8th and 7th centuries BC. Although heavily disturbed by Persian and Hellenistic pits, as well as by later burials and the bulldozer cut, the remains of two rectangular buildings, dated to the early 7th century BC, could be discerned. A clear relationship with the Neo-Assyrian Empire has been substantiated. However, Tall Dāmiyah’s precise role in this period has not been determined yet, hence further research is required. Was this building a type of trading post, or an Assyrian fort, as was previously thought? Alternatively, was Tall Dāmiyah a religious center, with the white-plastered building functioning as a temple? That the site had some cultic role is highly likely, as evidenced by the discoveries in the layer directly underneath the mud brick buildings; figurines and statues are reasonable arguments for assuming religious activity. Nevertheless, cook pots and loom weights were found in essentially contemporary layers, implying that, around 700 BC, Tall Dāmiyah was not merely either a temple or a trading colony. People were living on the site, hunting, farming, producing textiles and possibly trading.

Excavation work at Tall Dāmiyah continued in the autumn of 2015, between October 4 and November 5. ... The work was carried out in two areas: Area A on the summit (Squares IV, VIII, IX and XII) and Area B on the western lower terrace (Squares XIII and XIV) (Fig. 2).

A few skeletons from the Ottoman and Byzantine Period were excavated during this season, most of them discovered during the removal of the baulks. Two Ottoman graves were encountered and studied in Square VII; both were covered by stone slabs (Fig. 3). The discovery of an Ottoman pipe in the fill above these slabs in 2014 dates those burials to the latest occupation phase at Tall Dāmiyah. Over the five seasons, more than 50 skeletons have been carefully excavated and studied; results will be published in the nearby future.

During the 5th, 4th and 3rd century BC, the summit of Tall Dāmiyah was used for storage. Numerous pits cut through earlier Iron Age layers, sometimes more than 2 meters deep. Reports from previous seasons have described their outlook and content in detail (Petit 2013; Petit 2014; Kafafi and Petit 2018). During the 2015 season, two interesting finds were discovered in pits from this period. One was a single large fragment of a jar with an Aramaic ink inscription (Fig. 4), and the other was comprised of fragments of two storage jars, one of which could be reconstructed. Neither object has been discovered previously, and both provide additional information about the function and date of the pits.

Excavations have verified that, during the late Iron Age, the summit was inhabited by at least two buildings (Fig. 5). Whereas the most southern building seems to be domestic in nature, finds near and in the northern excavated structure suggest a cultic function (Kafafi and Petit 2018). In 2015, the archaeologists concentrated on the better preserved northern building and the street in between. The baulks were excavated and remaining debris on top of the floor was removed. By the end of the 2015-season, this level was reached in almost all squares.

The largest of the two buildings is rectangular in shape, oriented east-west, and has a doorway in the central part of the long southern wall. It was built on the top of a layer of artificial fill. At a few places, older wall remains were used as foundations, and one of these stumps acted as a division wall between the eastern and western part of the large room. In this rectangular building, all inner walls and installations were coated with white lime plaster. The inner dimensions are ca. 10.6 m in length and 4.2 m in width, and the building is considered large compared to contemporaneous structures at other sites in the vicinity. The roof was made of wooden beams, covered with smaller branches, reeds and packed clay. A heavy, stone roller was found on top of a layer of roof debris inside the building. Two mudbrick installations were found; one against the western wall and one in the north-eastern corner. The remains of the latter are difficult to interpret, due to its location close to the present surface. The western platform, probably the primary offering installation, was stepped, and plastered with lime (Petit and Kafafi 2016).

Several pottery stands and figurines, both of horses and females, were discovered inside and outside the building, and cultic activities can be assumed. The excellent condition of the figurines and the remains of two anthropomorphic statues are unique objects that have only a few parallels (Petit 2009b). Moreover, a clay bulla with cuneiform signs (found in 2004), Assyrian Palace Ware, a few Egyptian objects and Cypro-Phoenician and Ammonite pottery sherds, indicate relationships with the Jordanian Highland, Lebanon, Mesopotamia and Egypt. The head of an anthropomorphic statue (Fig. 6) was discovered near the northern wall, together with two animal skulls carefully placed on the walking surface.

Three other complete female figurines were uncovered in street-layers towards the southeast of the main building (Fig. 7). These objects were probably used during an earlier stage, implying that Tall Dāmiyah had a cultic function during large parts of the Iron Age. The co-directors suggest that Tall Dāmiyah was a significant and international religious centre during the late Iron Ages, along two major trade routes and close to one of the few fords crossing the Jordan River (Petit and Kafafi 2016).

The identification of Adama in biblical and Egyptian sources as an important town (Petit and Kafafi 2016), does not fit the situation found at Tall Dāmiyah, a small settlement mound with space for only a few buildings. Either the identification is wrong, or the remains of the town must be located elsewhere; for example, at the foot of the ‘acropolis’. Two squares were opened at the elevated south-western foot of Tall Dāmiyah (Fig. 2). Historical photographs suggest that it is part of a peninsula of white Qatar material that connect Tall Dāmiyah with the eastern Qatar hills.

Several graves and pits were discovered. The pits were circular and in almost all cases bell-shaped. They were filled with debris, some of which was mudbrick fragments. The pottery was a mixture of several occupation periods at Tall Dāmiyah; the presence of Byzantine pottery suggests that the pits were dug during or after this period. The graves must also have been post-Byzantine in date, based on similar reasoning. There were no funerary objects, and the skeletons were not buried according to the Islamic tradition.

All these features cut through a somewhat puzzling block of very regular white, black and yellowish layers (Fig. 8). Most of the material seems to be the result of some kind of industrial activity using intense heat. No structures have been detected yet, but the presence of burnt mudbrick suggest that some buildings were standing in the vicinity. Only fragmentary pottery with a mixed character was found. Coarse tempered pottery sherds might suggest an Islamic date, but in the lower ash layers, an increase in Late Bronze Age sherds was encountered, among them fragments of Cypriot milk bowls. The colourful accumulation of ash layers has, however, an identical parallel only a few kilometres to the north (Steiner 2008: Fig. 9). At Tall Abū Sarbuṭ similar layers were discovered between 1988 and 1992 dated to the Ayyubid/Mamluk period (De Haas et al. 1989; 1992; Steiner 2008). Although archaeobotanical research could not confirm the idea that sugar cane was processed, the excavators of Tall Abū Sarbuṭ believe the layers are the result of largescale burning, which took place somewhere else on the site (Steiner 2008: 165). Although the situation at Tall Dāmiyah equals these findings, future investigations should bring more information about the date and function of the layers. A natural sand deposit was reached below the ash layers, containing no material culture.

The excavation results of 2015 at Tall Dāmiyah have resulted in a better picture of the occupation during the late 8th and 7th century BC, as well as of the occupation remains at the foot of the settlement mound. Although heavily disturbed by Persian and Hellenistic pits, as well as later burials, the remains of two rectangular buildings on the summit, dated to the Late Iron Age, were further investigated. A clear relationship existed with the NeoAssyrian Empire, as well as with Ammon and the western areas. However, the role Tall Dāmiyah played in this period is still unknown, and needs further research. Was this building some sort of trading post, or an Assyrian fort, as was previously thought (Petit 2009a)? Or was Tall Dāmiyah a religious centre with the white-plastered building functioning as a sanctuary? The material culture especially, such as the complete figurines, statues and animal skulls, are strong evidence to assume religious activities at the site. However, in contemporary layers, especially in and around the southern building, cooking pots and loom weights were found, implying that around 700 BC, Tall Dāmiyah was more than just a sanctuary. At least in the southern building, people were living, hunting, farming, producing textiles and possibly trading.

Excavations in 2016 were carried out in three squares on the summit and aimed at investigating the southwestern corner of the sanctuary, unravelling its relationship with a domestic building located to the south, and studying older occupation phases. The area southwest of the sanctuary was unfortunately heavily disturbed by later burials and pits, making it hard to add new information to the already existing plan (Petit and Kafafi 2016: Figure 5). It is, however, clear from results encountered during previous seasons that this area was part of a street or courtyard between the sanctuary and the southern domestic building. Part of it was most likely roofed since several clay loom weights were encountered on the surface in 2016 (Fig. 32). The complete difference of the inventories of the two buildings is intriguing. It is suggested here that the southern building was primarily used as a living area, whereas the main rectangular building on the summit was intended for cultic purposes. Some of the finds from this phase, such as an Iron Age I figurine, advocate that Tall Damiyah was also used as a cultic place before Iron Age IIC.

An important aim of the 2016 field season was to investigate occupational remains below the phase of the sanctuary, especially in the southern square. The uncovered courtyard layers with several tabuns point to a domestic function, at least of this part of the site. Most of the finds in these layers were extremely fragmented due to frequent trampling.

Below these series of courtyard layers, a fragment of a mudbrick structure appeared that suffered a major conflagration. The wall and associated finds, such as a typical Iron Age II bowl, were dated to the 8th century B.C. (Fig. 31). Excavations of these earlier levels will be resumed in 2018.

In the autumn of 2018, the RMO and the Jordanian Yarmouk University organized the eighth excavation season at Tell Damiyah. This time most attention was paid to the layers beneath the sanctuary of 700 BC. Due to the strategic and special location of the site, the archaeologists suspected that Tell Damiyah had also been built earlier, i.e. in the early eighth century BC, had a religious function. Beneath the sanctuary, the archaeologists found the remains of an older, rectangular building. The walls were wide and made of square clay bricks. Unlike the later sanctuary, this structure had a main entrance on the north side. On the floor were the shards of a gigantic earthenware storage vessel with a diameter of more than one meter (fig. 7 - same photo as Fig. 2 of Petit & Kafafi, 2020). The red and black painting, mainly animal and plant motifs, is very similar to the decoration on a jar found in a shrine in the south of Israel. More research needs to be done on this building, but it is likely that Tell Damiyah was indeed used for a long time as a religious center for travelers and traders.

Excavations at Tall Damiyah were resumed during the falls of 2018 and 2019. These field seasons had two aims: to investigate the role of Tall Damiyah during earlier phases and to determine the extent of the Iron Age IIC sanctuary. In order to reach the second goal, the Jordanian-Dutch team opened several squares north of the main sanctuary building. First considered to be a freestanding construction, this turned out to be part of an extensive complex that had covered large parts of the summit. Not only was the main cultic room with the two altars destroyed by fire, the newly discovered rooms also showed traces of burning. Unfortunately, many graves and Persian-Hellenistic pits had wreaked havoc on these Iron Age layers, destroying much of the original floor deposits. Nevertheless, the team was able to uncover three additional rooms and a possible courtyard. Two of the rooms were in use for storage (Fig. 1). Numerous large kraters filled with burnt organic material, such as barley, were found in these rooms, preserved considerably well under a thick burnt debris layer. Other items, such as metal sickles and knives, suggest that the few occupants of Tall Damiyah were not only storing food but also harvesting. It is to be investigated whether this surplus was a donation of worshippers, was used for feeding visitors, or was a stockpile for the inhabitants to overcome arid periods. Much of the evidence point to a function as a caravanserai, where traders and travelers could eat, sleep, and worship.

During the 2018 season, the main aim was to investigate the role of Tall Damiyah during the Iron Age IIB and early IIC. Earlier evidence of cultic behavior was expected, following the assumption that the place had a religious significance over a longer period. Under the previously mentioned sanctuary, a freestanding building with thick, mud-brick walls was encountered. Although not burnt, collapse debris suggest some sort of destruction, although the team could not exclude deliberate dismantling. On the floor of this building, sherds of a large pithos were found, painted with a “tree of life” and two bulls or zebus (Fig. 2). A series of block-shaped pyramids forms the lower scene. Heavily fragmented and cut by a later pit, only part of the vessel was preserved. The closest parallel seems to be the pithos found in a temple context at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud. East of the building at Tall Damiyah stands a burnt mud-brick platform surrounded by ash lenses, and, farther to the south, several female figurines, most of them complete, were discarded in street levels. It seems at this stage safe to suggest that this earlier building also had a cultic function. Intriguing for the team is the clear distinction between the figurines found in this occupation phase (females) and those found in the later sanctuary (equids). It is proposed here that those figurines resemble the worshippers and not a deity. During the later phase, the Jordan Valley suffered a major arid period and the main group that visited Tall Damiyah were traders and travelers, those people associated with equids. In the earlier period the site was also used by sedentary occupants from nearby settlements with other intentions and thus other types of offerings.