Deir 'Alla

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Deir Alla | Arabic | دير علا |

| Tell Deir Alla | Arabic | |

| Ghor Abū ‘Ubaydah | Arabic - modern local name |

The Tell of Deir Alla was inhabited from the Bronze Age until late Persian times and is the place where the oracular Deir Alla Inscription (aka the Balaam Text) was discovered ( H.J. Franken in Meyers et. al., 1997). The area was also occupied in later periods. Some scholars have suggested an identification with Biblical Succoth, Penuel, or Gilgal and others have suggested an identification with Tar 'alah (aka Dar 'ellah) in the Jerusalem Talmud ( H.J. Franken in Meyers et. al., 1997, Halbertsma, 2019:26 citing Franken, 1969, and G. Van Der Kooij in Stern et al., 1993 v. 1).

The region in which Tell Deir 'Alia is located is referred to in ancient sources, including Shishak I's victory stela at Karnak, erected after his military expedition in the region. It is mentioned in the Bible in the context of such place names as Adam(ah), Penuel, Succoth, and Zarethan. According to 1 Kings 7:46, Phoenician craftsmen in the region cast bronzes for Solomon's temple in Jerusalem.

The site's name means "monastery situated high up." It has been identified mainly with two historical places, Succoth and Penuel. S. Merrill was the first to suggest Succoth, mainly because the Jerusalem Talmud identifies Succoth with Tar'ala, or Dar'ala, which may very well have been Tell Deir 'Alia. Identification with Penuel was proposed by A. Lemaire, based mainly on the existence of a large sanctuary at Deir 'Alia in the Late Bronze Age. Archaeological research has not yet offered certain identification of the site with any of the places named in the written sources, which are often characterized contradictorily.

Early topographical descriptions were given by Merrill and C. Steuernagel. Extensive surface explorations of the site were carried out by Glueck until 1942, in which he identified surface pottery sherds as originating in the Middle Bronze Age II, the Late Bronze Age II, and the Iron Age I-II.

The first archaeological excavations at Tell Deir 'Alla were conducted along the northern slope. In 1960, a team from the Netherlands, directed by H. J. Franken of the University of Leiden, opened a 30-m-wide stepped trench. In four seasons (1960-1964), the main goal - to collect a corpus of well-stratified, commonly used pottery from the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age-was reached. Franken's approach to the site was to emulate the detailed stratigraphical analysis practiced by K. M. Kenyon at Tell es-Sultan. In the course of the work, a Late Bronze Age sanctuary was discovered. In 1967, a new series of excavations was initiated to extend the excavation area to the east and southeast, in order to unearth the sanctuary complex. In addition, a sounding was made at the medieval tell (Tell Abu Gourdan), about 50 m to the northeast of Tell Deir 'Alla.

Excavations were resumed in 1976 that were continued in 1978, 1979, 1982, 1984, and 1987 by a joint expedition from the University of Leiden, the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, and, since 1980, the Yarmouk University in Irbid. The expedition was codirected by M. M. Ibrahim (DAJ and Yarmouk University), Franken (1976 and 1978) and G. van der Kooij (since 1979) from Leiden. The format for their research, a diachronic settlement study, was to excavate extensions of the previously excavated areas to the east and southeast (partly prompted by questions concerning the context of the Balaam inscription discovered in 1967). To date, Iron Age II strata have been excavated in the area under study, and some Middle Bronze Age rescue work has been done at the southeastern foot of the mound.

- from Halbertsma (2019)

1.1.1 – The 1960s excavations

Franken’s excavation methods, while not perfect by today’s standards, were ahead of their

time and still largely hold up to scrutiny. ... a well-defined excavated area and

archaeological period were chosen as a pilot project:

Franken’s Phase B, belonging to his ‘first period’ of Iron Age occupation at the

site. This period dates roughly to the second half of the 12th century BCE.

One of the few stand-out features belonging to the Phase B deposits at Tell Deir

‘Alla is a series of large installations, which for various reasons (which will

be discussed in the following chapters) were interpreted as having to do with

bronze-production (Franken 1969, 36-38). These installations, published as

‘furnaces’ by Franken, were attributed to the activity of large-scale bronze

casting, practiced by semi-nomadic metalworkers (Franken 1969, 21).

| Archaeological Period | Dates BCE |

|---|---|

| Late Bronze Age | 3000-1200 |

| Iron Age I | 1200-1000 |

| Iron Age II | 1000-550 |

... The Jabbok (now the Zerqa River) once ran to the north of the mound, shown by the river deposits in the lowest part of Trench D. These are the result of periodic flooding of the river, which kept depositing along the northern side of the mound until after the early Islamic period. The current bed of the Zerqa river is as such a recent development.

2.1.2 – Tell Deir ‘Alla

Tell Deir ‘Alla, meaning ‘tell of the high monastery’, is a prominent landmark in the Central

Jordan Valley, and is one of the larger tell sites in the immediate area. In his report of this

region, Nelson Glueck (1945-1949, 308) describes the tell as “one of the most prominent tells

in the entire Jordan Valley, and only Tell el-Husn (Beth-shan) and Tell es-Sultan (Jericho) can

compare favourably in importance and position with it”. It commands a central point in the

landscape, close to the mouth of the Zerqa Valley and the Zerqa River, and most of the nearby

tells are visible from its summit. Furthermore, the site is located along several trade routes.

These routes led from north to south, along the Jordan Valley, and from east to west, down the

Wadi al-Far’ah, crossing the ford at Tell Damiyah, and either following the Zerqa River

along and up into the Zerqa Valley, or via the ancient road going east from Ma’adi which is

now the main road in and out of the valley. One such route went from Beth Shean in the north,

through the eastern ghor to Tell Deir ‘Alla, where it would enter the Zerqa Valley and

continue up to the plains of Amman (van der Steen 2008b, 133).

The site measures around 250 by 200 meters, making it a medium sized tell for this part of

the Levant (see figure 3). The mound itself is 27 meters high, and its highest point is measured

at 201 meters below sea level. It was inhabited at least from the Middle Bronze Age through to

the Persian period, and evidence suggests it might have been inhabited during the

Chalcolithic as well. During the Islamic period it was used as a cemetery, similar to

many tell sites in the Jordan Valley.

2.2 – Franken and Tell Deir ‘Alla

Tell Deir ‘Alla was first excavated by Prof Dr Hendricus J. Franken (1917-2005), on behalf of

Leiden University, during five seasons between 1960-1964, and in 1967. Franken began his

career as a theologist, and after completing his PhD obtained a lectureship in Old Testament

archaeology in the Theological Faculty of Leiden University. Franken obtained funding from

the ZWO, the Dutch Organisation for the Advancement of Pure Research (now NWO), to study

the field techniques required to excavate in the Middle East. The Dutch governmental

research institute deemed it necessary that Dutch scholars obtain practical experience

with excavation techniques, and funded Franken so that he might run his own project in the

future, independently (Steiner and Wagemakers 2018, 38). At the recommendation of Gerald

Lankaster Harding, then director of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, he contacted

Dame Kathleen Kenyon to study with her at the 1950’s excavations at Jericho. He participated

for three seasons at Jericho, between 1955 and 1957.

Jericho had not produced an archaeological sequence covering the transition from the Late

Bronze Age to the Iron Age, the period he was interested in. Apparently, Kenyon had hoped

to also document this, but Tell es-Sultân did not yield any occupational phases from that

period. Kenyon was however able to establish a clear stratigraphically substantiated

chronology for the periods from the Neolithic to the end of the Middle Bronze Age. Franken

wanted to do the same for the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I. To do this he had to pick

out another site in the same region, which could provide stratified material that would

continue the chronology established at Jericho (Franken 1969, 2). Though explicitly not

his primary goal, Franken also hoped to excavate a site that could give archaeological

insights into the Israelite arrival into Palestine. If not evident at Jericho, then

perhaps another site close to the Wadi Far’ah might provide this information. Having worked

at Jericho, Franken was trained in the excavation of mud-brick sites. Due to this experience

he was of the opinion that such sites often provide a much greater depth of finely stratified

deposits than stone-built sites. He set out to find a site with mudbrick architecture close

to the Wadi Far’ah, and did so at Tell Deir ‘Alla. Franken had visited Tell Deir ‘Alla

during his travels through the Levant, and became convinced this site held the most

potential for the type of excavation he aspired. The site he had in mind needed to be

big enough to provide representative data from each occupational layer. On the other hand,

it needed to be small enough in order to reach the relevant layers without too much loss of time.

Franken was of the opinion that Tell Deir ‘Alla met both of these requirements, and began

organising the first season of excavation (Steiner and Wagemakers 2018, 43).

2.4 – Excavation strategy and methods

As mentioned above, Franken worked under Dame Kathleen Kenyon at the Jericho

excavations, from 1955 until 1957. During this period Franken familiarised himself with the

then state of the art Wheeler-Kenyon method, and saw its potential for excavations on mudbrick

tell sites. The main principles of the Wheeler-Kenyon method included a focus on the systematic

stratigraphic analysis of both architecture and relating deposits, which were excavated as smaller

units, named ‘Loci’ - or as is the case at Tell Deir ‘Alla - ‘Features’. This method often involved t

he excavation in square trenches placed on a grid, leaving baulks between the individual excavation

trenches. These baulks offered vertical sections of the already excavated deposits, used for

the ongoing interpretation of the excavated stratigraphy. Excavated finds were collected

and registered per feature, which were mapped onto detailed plans. This excavation and registration

method had as benefit the improved definition of the stratigraphy, and a more accurate registration

of the finds. Because of this attention to stratigraphy and find-contexts, this excavation

method aligned with his ambitions to construct a robust pottery chronology for the possible

changes from the Late Bronze Age to the Iron Age I.

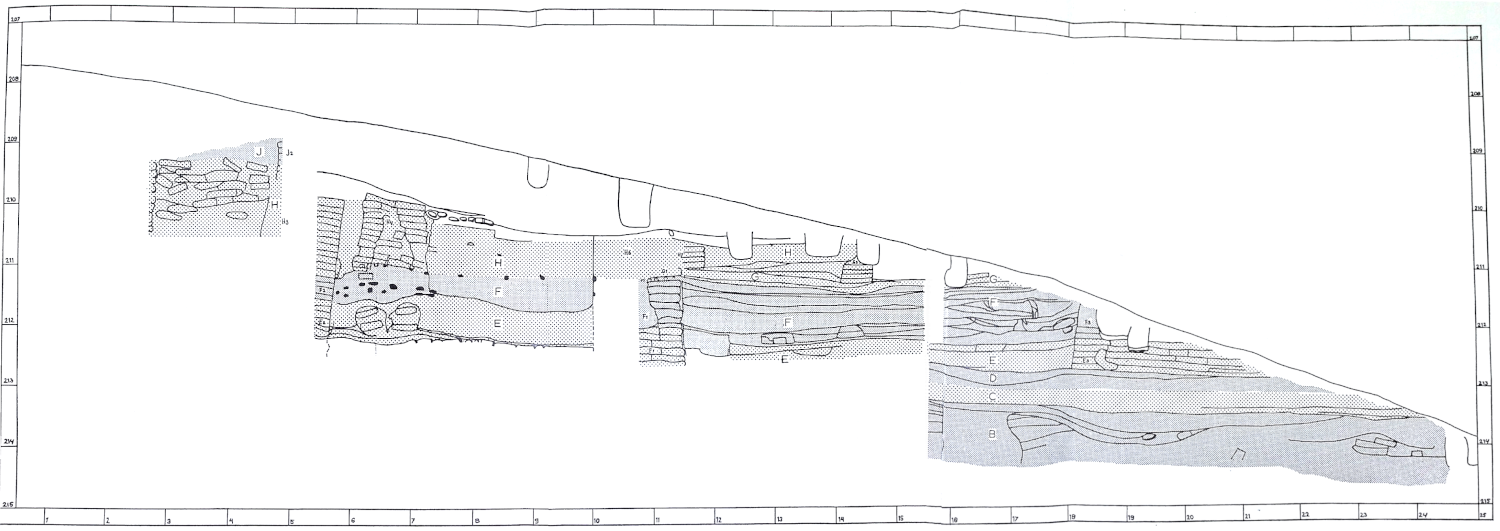

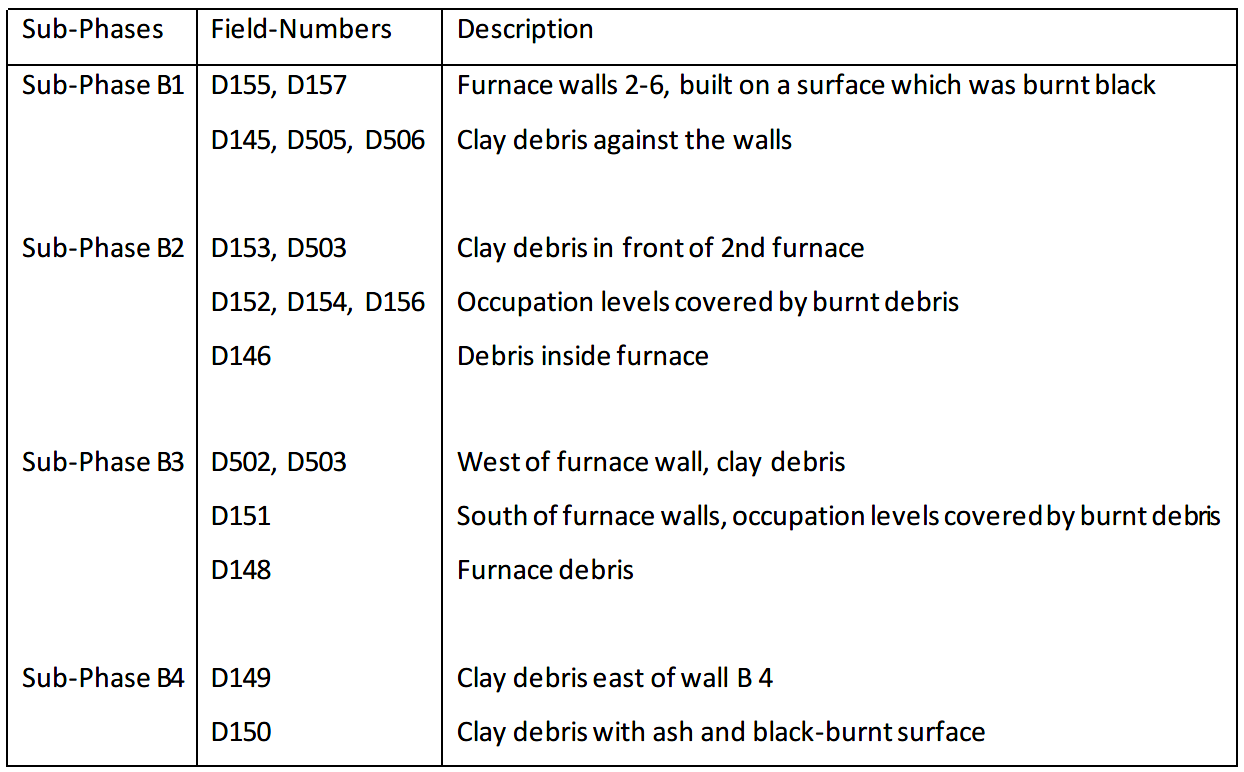

- Figure 6 Trench D Excavation

from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Excavating in Trench D, the 30-meter section trench, looking east

from the Tell Deir ‘Alla archive).

Halbertsma (2019) - Figure 7 Trench Layout

from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Layout of the trenches of the 1960s excavations at Tell Deir 'Alla (Franken 1969, 13).

Halbertsma (2019)

In line with the Wheeler-Kenyon method, a grid system was used for the Franken excavations at Tell Deir ‘Alla. This grid system covered the entire site. The main datum line for the excavation made use of a Jordanian Government survey point on the tell’s summit, and ran across the summit of the mound in an East-West direction. The exact positioning of this grid system is detailed in Franken’s 1969 publication (Franken 1969, 15). The Jordanian Government triangulation point was also used as the fixed point from which heights for plans and sections were taken.

Initially, for the purpose of these exploratory excavations an area of 30 by 30 meters was laid out on the grid, along a 30-meter line. This area was subsequently divided into 10 by 10 meter squares. These squares were named alphabetically, in order of excavation. Each individual square was then subdivided into 5 by 5 meter units, increasing the stratigraphic control of excavations. Each of these separate units, henceforth sub-squares, was given a series number, which allowed for precise data collection. For example, square A consisted of sub-squares A100, A200, A300, and A400. Per trench excavation of the 5 by 5 sub-squares proceeded from the top of the slope in a westward direction, stepwise down the slope towards the north (see figure 6). This had as benefit that no baulks were left between the sub-squares, which otherwise would create deep pits. Rather, prior to the excavation of each new trench to the west, the west section of the old trench would be carefully planned, providing as Franken put it “a walking baulk” (Franken 1969, 12). An added benefit to this excavation strategy was that each terrace had an open northern end which greatly facilitated the removal of soil, and eliminated any safety issues related to high, and thus unstable, baulks.

... Initially Squares A to C were excavated, creating the first east-west oriented step. While these excavation trenches adhered to the above described configuration, Trench D deviated from this set. This trench was created to provide a north-south cross-section of the entire excavated area, together with Trench C. Initially, this Trench D was 6 meters wide, but later extended to the full 10 meters. Resultantly, Trench D was 20 by 10 meters, and with the east section of Trench C, provided a north-south section of the entire 30 meter stepped trench. Trenches were also extended north of Squares A and B. These new sub-squares were initially identified as belonging to trenches A and B (to be specific named A500, A600, B300 and B500). However, during the 1961 excavations the 5 meter extension of Trench A (A500, A600) was further excavated as F100 and F200. As a result, there is an overlap between Squares A and F, and both Squares A and B are larger than the originally intended 10 by 10 meters. Subsequently, the remaining part of the 30 by 30 grid was excavated further as Trenches E to G, and Trench L. Squares H and K were eastwards extensions, made in the 1962 excavation season (Franken 1969, 15). Letters I and J were not used for excavation squares. Unfortunately the rationale behind this decision is not clearly detailed in the 1969 publication. For other purposes, Franken does not make use of the letter I to avoid confusion with the Latin numeral for one (Franken 1969, 26). Possibly a similar reasoning is behind the omission of trenches I and J. In 1964 the original 30 by 30 meter excavation area was extended towards the north and east, to investigate a number of interesting Late Bronze Age structures touched upon in this area (Franken 1992). However, these extended areas, which contain the Late Bronze Age sanctuary, are not within the scope of the present research. As such they will not be discussed in further detail.

The ideal excavation strategy outlined by Franken in both his main publications of these early seasons of excavation as well as his later work describing the Late Bronze Age sanctuary, appears not to have been followed in all cases. The resultant plan of the excavated area therefore has an overall planned, but somewhat cobbled together appearance (see figure 7), apparently due to idiosyncratic choices made in the field. Unfortunately, several of these diversions are detailed neither in the published works nor the original field documentation, significantly complicating the understanding and systematic reinterpretation of the excavations in these areas.

2.4.2 – Field documentation

Each stratigraphic unit, such as soil deposits, pits or walls, was documented as a separate

feature. Each received its own feature code, also referred to as a ‘deposit number’ (Franken 1992, 6).

While topsoil would simply receive the name of the sub-square (for example A100), each following

feature would receive an ascending number (for example A101, A102, A103). Both man-made structures

and individual earth deposits were excavated separately and

documented in this manner. Where possible individual floor layers were also excavated

separately. However, in the case of finely laminated floors and in some cases sequences of thin

soil deposits, this was not deemed practicable and instead a collective feature code was given.

This was indicated through the addition of the letter S to the sub-square code. Features present

in more than one sub-square received a separate number in each sub-square. These were then

linked in the field book. The appearance of said features were recorded per square in a

field notebook, detailing the feature and its relationship to the surrounding archaeology,

and providing simple illustrative sketches. Furthermore, each feature was recorded three

dimensionally, through scaled drawings (sections and plans) provided with elevations.

In addition to the field drawings and description in the field notebooks, black

and white photographs were taken of the most important features. Usually excavation was

paused until the photographs were developed. In certain cases this was not possible,

resulting in the lack of high quality photographs for a number of features. Colour

photos were only made on slides for educational purposes. In the later seasons

pull-offs were successfully made of several

sections.

Minor walls were excavated and drawn upon discovery. Significant earthquake damage was observed

at the site, often affecting the visibility of walls greatly. As such, the original plans often

proved rather misleading. The precise configuration of the walls was often only fully apparent

after complete excavation and examination of the nearest baulks. No heights were

taken of walls on the basis of Franken’s assessment that the stratigraphic positioning of walls

was not necessarily related to such measurements. As the broad exposure of architecture was not

an objective of these early excavations, substantial structures, as well as the directly surrounding

deposits would be left untouched for future systematic excavation. Conveniently, many of

these substantial structures were found along the trench edges and did not obstruct the digging

of the terraces. However, the Late Bronze Age sanctuary proved to fall well within the excavation

area, prompting a revised excavation strategy and extension

of the trenches in 1964.

2.4.4 – Excavations at Tell Deir ‘Alla after the 1960s

After Franken’s 1967 excavation season, hostilities in the region forced the excavations to

come to a temporary stop. The excavations were renewed as a joint expedition between Leiden

University and the Department of Antiquities of Jordan in 1976 and 1978, led by Franken and

Dr Mo’awiyah Ibrahim (Franken and Ibrahim 1978, 57). Due to the importance

of the abovementioned Aramaic plaster texts found during the 1967 season, these

excavations focussed on the Iron Age II period encountered on the tell’s summit.

This focus on the Iron Age II contexts at Tell Deir ‘Alla was continued by Franken’s

successor on Leiden University’s behalf, Dr Gerrit Van der Kooij, who took over the

excavations at Tell Deir ‘Alla from 1979 onwards in co-directorship with

Dr Mo’awiyah Ibrahim from the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. From 1998 the

Tell Deir ‘Alla excavations became a co-directorship between Leiden University and

the Yarmouk University, with Prof Zeidan Kafafi

as co-director of the project. While these excavations focussed largely on the Iron

Age II contexts on the tell’s summit, several trenches were opened on the northern,

eastern, and southern slopes of the site. These trenches yielded Late Bronze Age and

Iron Age I remains, which will be discussed in chapter 4. The excavations at Tell

Deir ‘Alla came to a stop in 2008, marking almost 50 years of ongoing research at

Tell Deir ‘Alla.

3.1 – The Iron Age I

The Iron Age I is a period that is not well understood in the Southern Levant. It follows a

chaotic period, commonly known as the Late Bronze Age collapse (ca. 1200-1130 BCE). What, or

who, exactly caused the onset of this brief but turbulent period is still a matter of debate,

but the results are clear. Numerous cities across the Levant are destroyed within a short time

frame, as is attested by archaeologically traceable destruction layers: “Within a period of

forty to fifty years at the end of the thirteenth and the beginning of the twelfth century

almost every significant city in the eastern Mediterranean world was destroyed, many of them

never to be occupied again” (Drews 1993, 4). Major sites which are destroyed during this period

are for example Emar, Ras Bassit, Ras Ibn Hani, and Tell Tweini (Cline 2014, 112-113). The

events comprising the Late Bronze Age collapse resulted in the demise of the Mycenaean palace s

ystem, the decline of both the Late Bronze Age Egyptian and Hittite Empires, and the

loss off an intricate economic, political, and culturally connected system of networks

(Killebrew 2014, 595). This series of cataclysmic events was traditionally seen as the end of an

‘Age of Internationalism’, of the ‘heroism’ portrayed in the Iliad, and has been interpreted to

have resulted in the displacement of large groups of peoples (Ibid.).

The successive Iron Age I is traditionally regarded as a period of ‘dark ages’, lasting

for several centuries (Sandars 1978; Wood 1996, 210-259). In this period a shift appears to have taken

place from the complex and interconnected palatial systems of the Late Bronze Age to small

and isolated village structures. However, the Iron Age I has only recently become understood

to be more than only a period of demise, but also a period “characterized by multidirectional

cultural and socio-economic interconnections that preceded and coincided with a more

protracted demise of the Bronze Age” (Killebrew 2014, 595). Furthermore, this period saw

significant societal and political reconfiguration, which is expressed in smaller-scale

connectivity, rather than adhering to the preceding Late Bronze Age internationalism

(Bloch-Smith and Alpert Nakhai 1999, 115). These changes eventually resulted in the

formation of local polities in the Iron Age II Southern Levant, such as the kingdoms of

Ammon, Edom, Israel, Judah, and Moab. This reconfiguration allowed for new traditions

to be developed, old ones to be reinterpreted, new trade routes to be connected, and

new opportunities to be grasped. This period at the turn of the Late Bronze Age and

Iron Age I falls largely in the 12th

century BCE.

3.1.1 – The Iron Age I in the Southern Levant

Following the Late Bronze Age collapse, the Southern Levant appears to have gone through

a hectic period, which included the abandonment of sites, changes in material culture,

and interruptions in trade relations. This period in turn was followed by a

period of reconfiguration, rebuilding, and at certain sites also continuation of older

traditions, all falling roughly in the 12th-10th century BCE. While all of these general

patterns have been attested

in the archaeological record on both sides of the Jordan River, for the area east of the Jordan

River, henceforth referred to as Transjordan, much less is known about this tumultuous period.

The number of excavations on sites with Iron Age I levels in this area remains significantly

lower than in Cisjordan. Larry Herr states in his exploration of the Iron Age I in Transjordan,

that many sites in this region have most likely even been mistakenly identified as Iron Age I.

Several older excavations and surveys tended to misidentify pottery as Iron Age I, when it was

actually Iron Age II (Herr 2014, 650). Of the sites which have been excavated,

a staggering number remains (largely) unpublished, often only accessible through small

numbers of preliminary reports describing what was done during the different seasons of excavations.

This makes any comprehensive studies on Iron Age I settlement dynamics, socio-political changes,

and changes in material culture a difficult endeavour.

Endeavours have been made, however, such as in Bruce Routledge’s book on the archaeology of Moab,

Eveline Van der Steen’s book on the Iron Age I in the Jordan Valley, and Larry Herr’s

chapter on Iron Age I Transjordan (Routledge 2004; Van der Steen 2004; Herr 2014).

Combining the results from these studies on Iron Age I Transjordan, in addition to Ayelet

Gilboa’s synthesis of the Iron Age I period in Cisjordan (Gilboa 2014, 625-626), the following

model could be proposed for the Iron Age I Southern Levant.

- During the Iron Age I the Southern Levant becomes free of external domination, as the chaos of the Late Bronze Age collapse resulted in the retreat of the two main imperial powers of the time: Egypt, and to a lesser extent the Hittites. This ‘power vacuum’ allowed for new societal and political configurations, which in the various regions of the Southern Levant take different forms.

- Contact between Cisjordan and the Aegean and beyond nearly ceased altogether, contact with Cyprus and Egypt decreased significantly. Interregional trade, while formerly ‘state administered’, assumes a new and less centralised form. In settlements a larger focus emerges on the “modular repetition of pillared houses” (Routledge 2004, 89), which is seen as indicative of a larger focus on the village and (nuclear) family (e.g. Stager 1985, 20).

- Bronze production was still crucial, but the Cyprus and the Egyptian Timna mines were severely weakened. This gap was likely filled by mining enterprises in the Wadi Faynan copper mines, through local initiatives.

- A settlement shift from lowland to highland areas is witnessed throughout the Southern Levant, together with an influx of new peoples that had been displaced by the turmoil of the Late Bronze Age collapse. Furthermore, there is an increase in site density compared to the Late Bronze Age, but not necessarily in site dimensions.

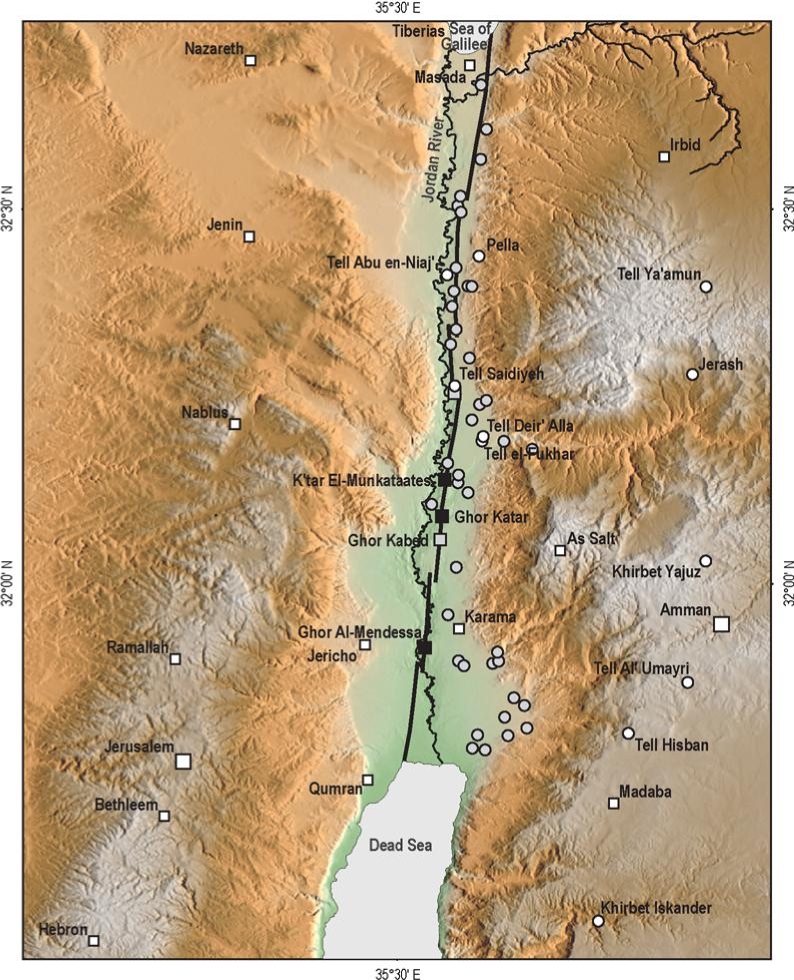

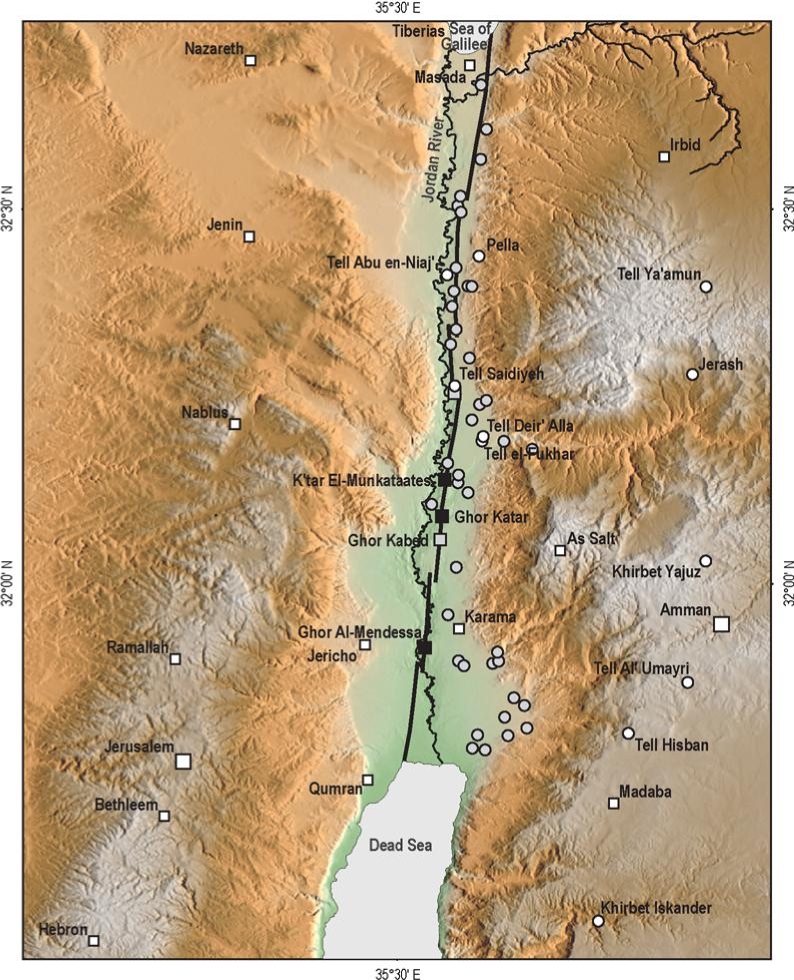

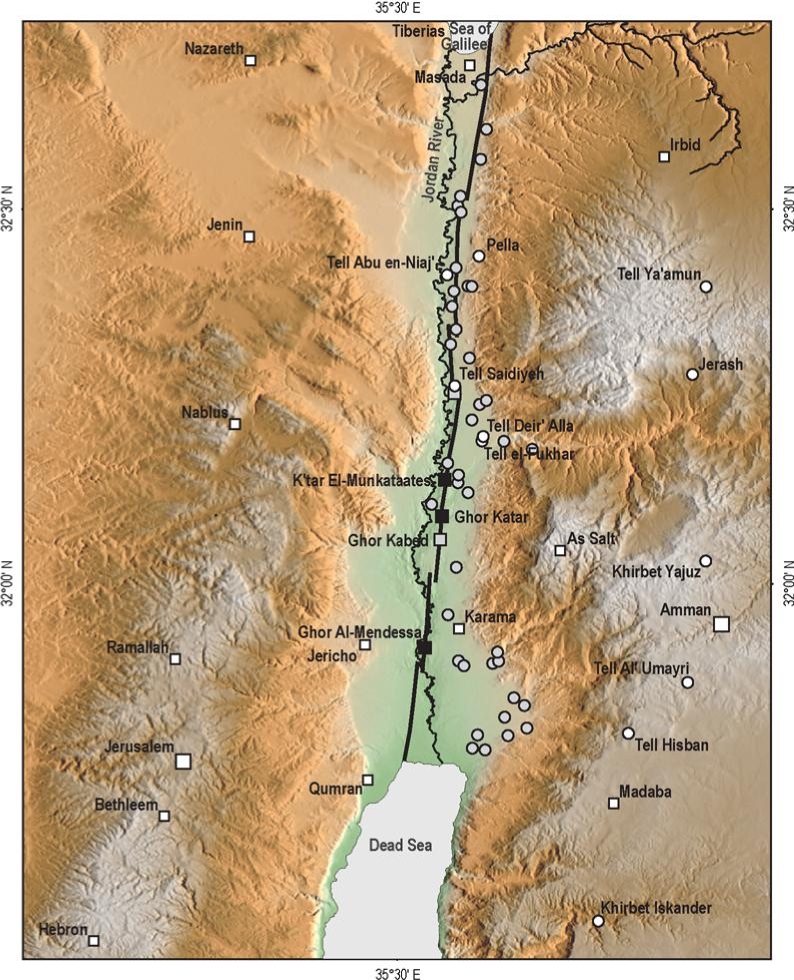

- Figure 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019)

The Jordan Valley itself, which forms the regional setting for the site of Tell Deir ‘Alla, shows most of the features described above associated with the 12th century BCE. There are sites that are abandoned, resettled, or destroyed. As this thesis’ aim is to explore this period specifically from the perspective of Tell Deir ‘Alla, the following chapter will provide a focussed overview of the archaeological evidence pertaining to the 12th century BCE in this region.

The Jordan Valley, which as mentioned in chapter 2 will cover the area from the southern end of the Sea of Galilee to the confluence of the Jordan and Zerqa Rivers, is mentioned as both the exception to and the rule of the larger narratives about the Late Bronze Age to Iron Age I. Contradictory statements about the character of the Jordan Valley in this period are numerous. Iron Age I sites in the Jordan Valley are, sometimes within the same volume, referred to as both “no more than the poor habitations of pastoralists and accompanying animal pens” (Gilboa 2014, 642) as well as seeming “to reflect a more prosperous lifestyle and [containing] a material culture that is oriented more toward the west than sites on the plateau” (Herr 2014, 649). This creates a confusing narrative, entirely dependent on which perspective is chosen for the specific passage.

In order to disentangle this confusing picture, a brief overview will be provided of the evidence gleaned from the archaeological record, which includes various survey projects that provide evidence for the settlement patterns of the Iron Age I in the Jordan Valley, as well as various archaeological excavations of sites with Iron Age I habitation layers.

Survey results

While typically travel reports from the Middle East are associated with 19th century travellers from the West, the Jordan Valley was already frequented and written about from at least as early as Idrisi (1154 CE), Yakut (1225 CE), and Ibn-Batuta (1326 CE) (Le Strange 1890, 31; Gibb 1958, 82-83). The first historical investigations of this area done by the 19th century Western travellers were usually focused on the identification of biblical sites (for a comprehensive list of all travellers' reports and surveys regarding the Jordan Valley, see Kaptijn 2009b).

The first wave of trained archaeologists who began identifying archaeological phenomena in the region, including Albright (1924-1925) and Glueck (1945-1949), began observing that a number of important changes in settlement patterns could be identified for the end of the Late Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age I. Albright, for example, describes that the Jordan Valley must have been the first part of Palestine to be heavily developed, despitethe heat and "mosquito-breeding swamps" (Albright 1924-1925, 67). He noticed that the amount of Late Bronze Age sites in the Jordan Valley was significantly higher than in the hills, and remarks that most of them were abandoned in the Iron Age I, except for Tell Deir 'Alla (which he calls 'Succoth' in his publication) (Ibid., 68). A similar pattern is discussed by Glueck, who argues on the basis of his thorough survey of the Jordan Valley, that the Jordan Valley was not only one of the first settled areas (by which he meant urban settlements of the Bronze Age) of the Southern Levant, but also one of the richest parts of the entire area. He noted that 30 Iron Age I-II settlements were encountered in the area between the southern end of the Sea of Galilee, and the confluence of the Jordan and Zerqa Rivers (Glueck 1945-1949, 335).

While these important early archaeological surveys provided the foundations for the understanding of this period in the Jordan Valley, in more recent years additional large -scale surveys and the subsequent systematic reinterpretation of the existing survey data have allowed for the refinement of this image, such as the East Jordan Valley Survey (Ibrahim et al. 1976), and Eveline Van der Steen's survey during the 'Deir 'Alla Regional Project' (Ibrahim and Van der Kooij 1997; Van der Steen 2004).

The important work by Eveline Van der Steen, combining excavation and survey data of the Jordan Valley (e.g. Van der Steen 1996, 53), produced a picture which shows an increase in Iron Age I sites in comparison to the Late Bronze Age, especially in the Central Jordan Valley. However, the amount of Late Bronze Age sites in this area was already much larger than expected in comparison with other regions (Van der Steen 2004, 101). Additionally, her research identified patterns in the preferential location of Iron Age I sites in this region. Whereas the Late Bronze Age sites are found spread throughout the ghor area, the Iron Age I sites are most often located near a water source such as wadi's. As such, many Iron Age I sites are located along the Zerqa River, resulting in a higher density of sites located in the Central Jordan Valley in comparison to the surrounding areas, in particular the regions north of Tell es-Sa'idiyeh, and south of Tell Damiyah (Ibid.).

This picture is later substantiated by Eva Kaptijn's survey results from the large-scale 'Settling the Steppe' project (Kaptijn 2009b). This project focussed on creating a diachronic perspective of settlement strategies in the Central Jordan Valley, and like Van der Steen's work, shows that the Central Jordan Valley has the highest settlement density of Iron Age I sites in the entire Jordan Valley (Kaptijn 2014, 27). The increase is substantiated with a graph combining both site numbers and settlement density. There is an increase from 26 Late Bronze Age sites, to 37 Iron Age I sites, of which the densest cluster is in the Central Jordan Valley. Another interesting observation stemming from this project, was her theory that larger investments in irrigation strategies likely began somewhere during the Iron Age (Kaptijn 2009b, 410). This allowed for a higher percentage of crop yields, which might have resulted in population growth and subsequently more permanent settlements in the area. Unfortunately her survey conclusions don't differentiate between Iron Age I and Iron Age II, which might narrow this process down further.

Finally, a targeted site survey at several sites in the Central Jordan Valley was conducted by Lucas Petit (Petit 2009). This survey conducted targeted excavations for known Iron Age II sites, in order to gain a better understanding of the settlement dynamics of this period. This project succeeded in the identification of a process of oscillation of habitation at numerous sites, with rapid abandonment and resettling being the norm rather than the exception. Importantly, he observed that the Jordan Valley could be seen as a 'high risk, high reward' area, where the inhabitants had to maintain a manner of flexibility in their subsistence strategies in case of sudden internal or external threats. Petit postulates that this meant maintaining a communication network with the inhabitants of the highland areas, to have a place to fall back on when in need (Petit 2009, 229). While his study focussed on the Iron Age II, this model should be kept in mind for the study of the Iron Age I period, as during this period similar situations might have forced rapid changes in subsistence strategies for the inhabitants of the Central Jordan Valley.

In conclusion, the survey results of this area provide a picture of both change and continuity between the Late Bronze age and the following Iron Age I period. It is suggested that an increase in site density can be witnessed for this period, with a clear locational preference. These observations are particularly important with the political reconfiguration of the Iron Age I in mind, and provide a general, but essential framework in which to interpret the archaeological evidence deriving from the excavation of sites dated to this complex period in the history of the Jordan Valley and surrounding areas.

Excavations of Iron Age I layers

While surveys have indicated the presence of a large number of Iron Age I sites in Trans-Jordan, not much is known about the habitation at these sites. As mentioned above, in comparison to Cisjordan, excavations of Iron Age I layers in Transjordan are still quite rare. This holds true for the Jordan Valley, despite numerous long-term excavation projects in this region. These projects tended to focus on the Late Bronze Age or the Iron Age II, due to the picture of the Iron Age I being 'dark ages'. Seen as a period of decline, Iron Age I occupation often fell between the cracks. Nonetheless, at a modest number of sites layers dating to this period were excavated, giving us some more insights into the material culture and habitation in this period. With the published data several conclusions can be drawn about the Iron Age I in the Jordan Valley.

Of the 37 Jordan Valley sites identified as having habitation dating to the Iron Age I, only roughly 8 published excavations have touched upon those layers thusfar. These most notably include Tell Deir 'Alla, Tell el-Mazar, Tell es-Sa'idiyeh, Tell al-Hammeh, Tell Abu al-Kharaz, Beth Shean, Pella, and Tel Rehov. The most extensively excavated, and published, of these is Beth Shean, where substantial architecture has been uncovered. This site gives evidence of the presence of a large Egyptian garrison town at the site, during the 12th century BCE. It is estimated to have had a modest, but substantial community, with extraordinary richness portrayed in the Egyptian-style public buildings. The material found at this site reflects an ongoing engagement with Egypt, as well as an abundance of local Canaanite traditions. This is indicative of continuity of tradition, where not much changes throughout the 12th century. While several sites show similar patterns of continuation, such as Tel Rehov and to a lesser extent Tell al-Hammeh, Tell Deir 'Alla shows a highly different pattern. At this site the substantial Late Bronze Age sanctuary was destroyed in the first half of the 12th century, after which the site was briefly abandoned. It was then resettled, arguably by 'newcomers' (Franken 1969, 20-21) who came from a different area than the Jordan Valley. The layers belonging to these phases are associated with evidence for metalworking. This pattern of abandonment and resettling shows similarities with other sites, such as Tell Abu al-Kharaz. Particularly in the change in material culture do these similarities emerge, which could be a signal of the reconfiguration of interregional contacts mentioned above. The picture that emerges from the brief outline mentioned above, largely shows that two broad categories of characteristics can be discerned for the Iron Age I in the Jordan Valley, being that of abandonment, destruction, and resettlement, or 'change' in short, as opposed to continuation of local traditions. A third category will be added, being excavated Iron Age I sites with lack of or problematic data. Below a number of the main observations are discussed in more detail.

Table 2

Table 2List of discussed archaeological sites with relevant phases as published, with corresponding dates BCE.

Halbertsma (2019)

Abandonment, destruction, and resettlement: change

Several sites in the Jordan Valley appear to be abandoned, or have been abandoned,

and subsequently resettled in the period of the 12th century BCE. Clear evidence

for this pattern is attested at Tell Deir ‘Alla. During the Late Bronze

Age Tell Deir ‘Alla housed an extraordinarily substantial religious structure,

or sanctuary. This sanctuary had been built already during the Middle Bronze Age,

on an artificially levelled platform. It consisted of a

central cella, which functioned as the ‘holy of holies’ of the sanctuary, and was

flanked by several store-rooms which contained ceremonial and functional pottery, of both local

and imported Aegean origin, imported objects such as cylinder seals, and inscribed tablets.

The sanctuary’s architecture shows features of Egyptian building characteristics,

comparable to the Fosse Temple at Lachish (Franken 1961, 365). Based on these

characteristics, it was postulated that the sanctuary possibly functioned as a

hub for a regional market-economy (Franken 1992, 178), trading between the Jordan Valley,

Egypt, and possibly Syria and Lebanon. Somewhere after 1180 BCE the temple was destroyed

most likely by an earthquake. The specific date was attested by the terminus post quem

provided by a cartouche of Queen Taousert from the latest layers of the temple. This

destruction event is witnessed in a clearly recognisable destruction layer, with mud-bricks

burnt to a degree of vitrification (Franken 1961, 367). This event did not cause the

inhabitants to abandon the site immediately, however, as it is apparent from the

archaeological record that attempts were made to rebuild parts of the sanctuary, and

possibly salvage some of the temple’s inventory (Franken 1969, 20). Another fire resulted

in the end of this phase, and the site was briefly abandoned. However, this abandonment

phase did not last long, as on top of the debris from the Late Bronze Age sanctuary

a series of industrial installations were built. Franken suggests that this was done

by a group of newcomers, as mentioned above, largely on the basis of a new pottery

repertoire unlike that of the Late Bronze Age inhabitants (Franken 1969, 20-21).

These phases, Franken’s Phases A-D, fall somewhere in the second half of the 12th century BCE.

These phases have been published, but largely limited to the analysis of the pottery

chronology (Franken 1969).

At Pella there is a similar situation as seen at Tell Deir 'Alla, namely destruction and resettlement,

but not abandonment. Pella, or Tabaqat Fahl, is a 30-meter-high mound located at the edge of the eastern

foothills of the Jordan Valley. It hosted very substa ntial Middle to Late Bronze Age city, which is

mentioned in the Amarna letters. Excavations atthe site yielded multi-roomed Late Bronze Age, Pella Phase IA,

domestic structures, a multi-roomed courtyard building, as well as a 'Governor's Residence', an

administrational/palatial residence of significant size (Bourke 1997, 108). Finds from these buildings

include imported Aegean pottery, lapis lazuli, and cuneiform tablets, indicative of long-distance trade.

Furthermore, a stone-built Migdol Temple was excavated measuring around 35 x 20 meters, making it one of

the largest such temples in the Southern Levant (Bourke and da Costa in Egan and Bikai 1999, 495). Finds

from this temple include ivory and faience furniture inlays, faience, carnelian, and lapis lazuli beads,

a bronze spearhead, and a ritual ceramic bowl (Ibid.). It was likely constructed around 1450 BCE, and

continually used until its destruction in the 9th century BCE, although its shape changed significantly

overtime. To the west of this substantial temple was another large building, with heavy walls made from

mudbrick. This building, postulated to have been constructed around 1300 BCE, contained numerous storage

jars, cooking vessels, and drinking vessels, leading t he excavators to assume it was a public building,

possibly for the Iron Age rulers of the town. It was most likely destroyed around 850 BCE. While these

large buildings appear to have been used continuously throughout the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I,

this did not happen without incident. The entire excavated area is marked by an "extensive fierydestruction"

dating to the 12th century BCE, Pella Phase O (Bourke 1997, 110). While Pella does not seem to have been

abandoned after this heavy conflagration, the quality of attempted repairs at the site indicate it had

significantly declined in its critical faculties, and is left a fairly modest village. Interestingly,

one of the buildings from this phase contained a foundation deposit of six 'lamp and bowls', a pottery

vessel typical for the 12th century BCE (Ibid., 113). Pella is still awaiting a final comprehensive

publication, so unfortunately one must err on the side of caution with most of the published contexts.

Another site which does have evidence for abandonment, is Tell Abu al-Kharaz. This site, located just

north of the perennial Wadi al-Yabis, appears to have been continuously occupied from the Early Bronze

Age throughout the Late Bronze Age, during which there was a large fortified city. Then, from the Late

Bronze Age to the late Iron Age I, there was a sudden break in the site's occupation. This lacuna is

postulated to have been caused by a destruction event, but the precise dating of this event is not

without complications. While the final Bronze Age phase, Tell Abu al-Kharaz phase VIII, is known to

start around 1350 BCE, the exact end of this phase is unknown due to disturbances in the stratigraphy

by later Iron Age occupation. As such, dating the destruction layer causing the lacuna is difficult.

However, it is clear that the site wasn't occupied again until the late Iron Age I, around 1100 BCE

(Fischer and Burge 2013b, 309). Although the precise dating remains an issue, there is a clear occupational

gap during the 12th century BCE, the period in which both Tell Deir 'Alla and Pella are destroyed and

subsequently resettled. Tell Abu al-Kharaz is well published, with comprehensive final publications on

the Early- and Late Bronze Age and Iron Age layers (Fischer 2006; Fischer 2008; Fischer, 2014).

While not entirely fitting with the sites described above, the Tell es-Sa'idiyeh cemetery shows evidence

for change in a different way. Tell es-Sa'idiyeh is a substantial tell site to the northwest of Tell

Deir 'Alla, and at only 1.8 km from the Jordan River, close to the katar. It rises some 40 meters

above the surface, and consists of an upper and a lower mound. On the lower mound an impressive

cemetery was encountered, yielding around 500 individually numbered burial installations (Green 2013, 420).

These date from the Late Bronze Age to the end of the Iron Age I. These burials show evidence of

local burial customs (consisting of rectangular or oval pits sometimes lined with mud-bricks),

as well as burials in ceramic jars (single jars with interred children and double-pithos burials

containing adults). Interestingly, the latter of these burials, and only the latter, were robbed in

antiquity. Among the burials were signs of attempted mummification using bitumen, dressing and

ornamenting the body, as well as secondary treatment of burials (Green 2006, 243-261). Burials

yielded numerous artefacts pointing to wealth, social expression, and long-distance trading,

such as metal scarab-rings, lotus-vessel pendants, scaraboids, electrum toggle-pins, necklaces,

(ankle) bracelets, bronze weapons, bronze 'wine sets', and finger-rings (Ibid., 422-427; Tubb

1988b, 58-65). The cemetery is published extensively by Jack Green (e.g. Green 2006; Green 2007;

Green 2009; Green 2010; Green 2013; Green 2014), who established that the burial record could be

used to identify social changes during the end of the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I. For example,

based on a study of which individuals wore certain personal adornments, he was able to reconstruct a

possible shift in kinship structure towards the Iron Age I, with a "shift to a more patriarchal

society in the Early Iron Age" (Green 2007, 303-304). Other than kinship, a preference in burial

goods seems to have shifted as well, where Egyptian-style beads in the Iron Age I were usually

interred with children, whereas in the Late Bronze Age burials they usually accompany adults (Green 2013, 427).

Figure 21

Figure 21Idealized models for the major characteristics in cross-sectional view of the three types of flower structures present in the divergent-wrench fault zone.

- Negative

- Positive

- Hybrid

Huang and Liu (2017)

Flower structures are typical features of wrench fault zones.Identification is

based on differences in their internal structural architecture.Negative and Positive Flower Structures are widely known in Paleoseismology. Huang and Liu (2017) proposed a model of a 3rd type of flower structure - the Hybrid Flower Structure. All 3 types of flower structures are summarized below:

- Negative flower structures

- consists of a shallow synform bounded by upward spreading strands of a wrench fault with mostly normal separations

- occur in divergent-wrench fault zones where blocks move parallel to each other (i.e., pure strike-slip faults) and move with a component of divergence (i.e., divergent or transtensional wrench faults), especially easily occur in the regions of releasing bends and step overs along these wrench faults

- their presence indicates the combined effects of extensional and strike-slip motion.

- Positive flower structures

- consists of a shallow antiform displaced by upward diverging strands of a wrench fault with mostly reverse separations

- only occur in fault restraining bends and step overs where blocks move parallel to each other (i.e., pure strike-slip faults) and move with a component of convergence (i.e., convergent or transpressional wrench faults)

- Hybrid flower structures

- characterized by both antiforms and normal separations

- only occur in fault restraining bends and step overs

- can be considered as product of a kind of structural deformation typical of divergent-wrench zones

- is the result of the combined effects of extensional, compressional, and strike-slip strains under a locally appropriate compressional environment.

- The strain situation in it represents the transition stage that in between positive and negative flower structures.

- Kinematic and dynamic characteristics of the hybrid flower structures indicate the salient features of structural deformation in restraining bends and step overs along divergent-wrench faults, including the coexistence of three kinds of strains (i.e., compression, extension, and strike-slip) and synchronous presence of compressional (i.e., typical fault-bend fold) and extensional (normal faults) deformation in the same place.

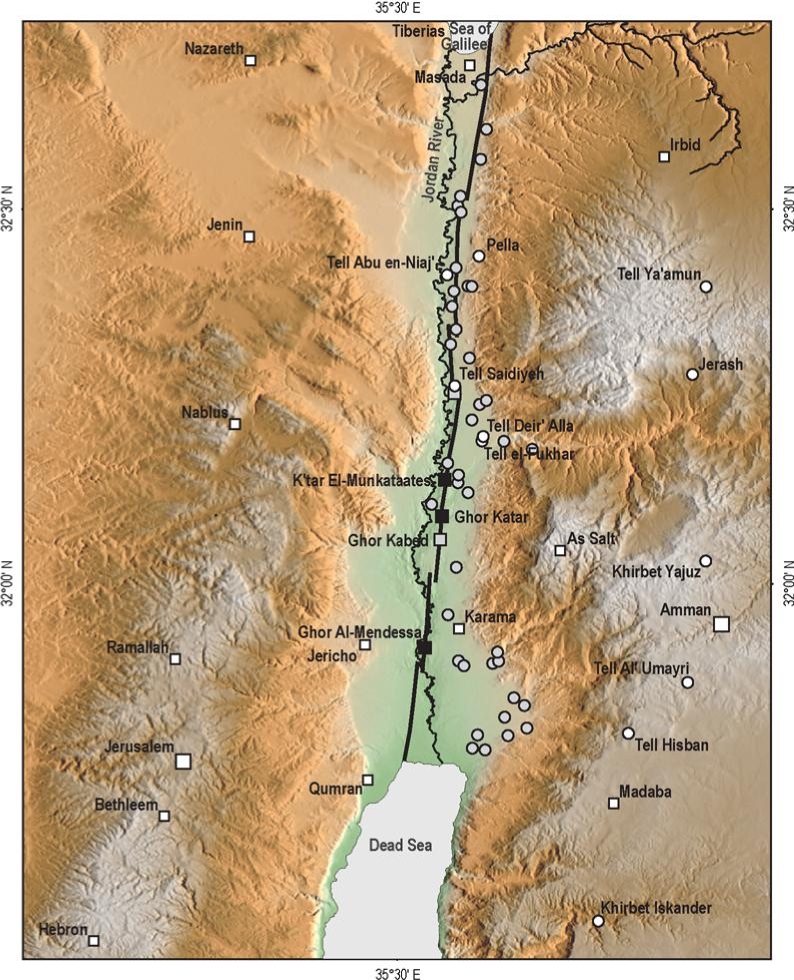

- Location Map from

Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Deir 'Alla region, based upon topographic map 1947

Van der Kooij (2006) - Jordan Valley Sites from

Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Archaeology of the Jordan Valley.

- White squares, main populated areas cited in historical documents

- white dots, archaeological sites visited and reappraised in this study

- gray dots are archaeological sites not studied here (lack of evidence and/or available literature) but of potential interest for future studies

- gray squares, paleoseismic sites

- black squares, geomorphological sites studied by Ferry et al. (2007)

Ferry et al. (2011)) - Fig. 2 Map of Iron Age I

sites in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Jordan Valley with Iron Age I sites mentioned in the thesis. The open circles are modern cities.

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019)

- Location Map from

Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Deir 'Alla region, based upon topographic map 1947

Van der Kooij (2006) - Jordan Valley Sites from

Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Archaeology of the Jordan Valley.

- White squares, main populated areas cited in historical documents

- white dots, archaeological sites visited and reappraised in this study

- gray dots are archaeological sites not studied here (lack of evidence and/or available literature) but of potential interest for future studies

- gray squares, paleoseismic sites

- black squares, geomorphological sites studied by Ferry et al. (2007)

Ferry et al. (2011)) - Fig. 2 Map of Iron Age I

sites in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Jordan Valley with Iron Age I sites mentioned in the thesis. The open circles are modern cities.

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019)

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of

Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial view of Tall Dayr ‘Allå

(after G. Van der Kooij 2006)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 4 Aerial view of

Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2023)

- Deir 'Alla in Google Earth

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of

Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial view of Tall Dayr ‘Allå

(after G. Van der Kooij 2006)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 4 Aerial view of

Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2023)

- Map of the mound and

excavation areas from Stern et al. (1993 v. 1)

Tell Deir 'Alla: map of the mound and excavation areas

Tell Deir 'Alla: map of the mound and excavation areas

Stern et al. (1993 v. 1) - Site Plan with Excavation

Areas from Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Tell Deir 'Alla site plan: fields of Excavation

Van der Kooij (2006) - Fig. 1 - Map of the

mound and excavation areas from Kafafi (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Contour Map and distribution of areas and squares at Tell Deir 'Alla

Photo: Deir 'Alla Expedition

Kafafi (2023) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Excavation

Trenches of the 1977-1978 seasons from Franken and Ibrahim (1978)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Tell Deir 'Alla Excavation Trenches

Franken and Ibrahim (1978)

- Map of the mound and

excavation areas from Stern et al. (1993 v. 1)

Tell Deir 'Alla: map of the mound and excavation areas

Tell Deir 'Alla: map of the mound and excavation areas

Stern et al. (1993 v. 1) - Site Plan with Excavation

Areas from Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Tell Deir 'Alla site plan: fields of Excavation

Van der Kooij (2006) - Fig. 1 - Map of the

mound and excavation areas from Kafafi (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Contour Map and distribution of areas and squares at Tell Deir 'Alla

Photo: Deir 'Alla Expedition

Kafafi (2023) - Fig. 1 - Plan of Excavation

Trenches of the 1977-1978 seasons from Franken and Ibrahim (1978)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Tell Deir 'Alla Excavation Trenches

Franken and Ibrahim (1978)

- Fig. 1 - Top plan of

the recovered architectural remains of the last stage of Phase IX (Area B) from Ibrahim and van der Kooij (1991)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Top plan of the recovered architectural remains of the last stage of Phase IX (Area B). Dotted lines refer to later disturbances (pits, erosion, egalisation)

Ibrahim and van der Kooij (1991) - Fig. 4 Section and plan

of Middle Bronze structures showing collapsed walls from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Section drawing and plan of MB structures excavated 1976-1978

(after Franken and Ibrahim 1977-1978; Van der Kooij 2006)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 16 Plan and section

of excavated structures in Squares C/P 13 and 14 from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

Plan of the excavated structures in Squares C/P 13 and 14

(after Ibrahim and Van der Kooij 1997)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 82 West Section

of the excavated area from Franken (1969)

- Fig. 1 - Top plan of

the recovered architectural remains of the last stage of Phase IX (Area B) from Ibrahim and van der Kooij (1991)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Top plan of the recovered architectural remains of the last stage of Phase IX (Area B). Dotted lines refer to later disturbances (pits, erosion, egalisation)

Ibrahim and van der Kooij (1991) - Fig. 4 Section and plan

of Middle Bronze structures showing collapsed walls from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Section drawing and plan of MB structures excavated 1976-1978

(after Franken and Ibrahim 1977-1978; Van der Kooij 2006)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 16 Plan and section

of excavated structures in Squares C/P 13 and 14 from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

Plan of the excavated structures in Squares C/P 13 and 14

(after Ibrahim and Van der Kooij 1997)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 82 West Section

of the excavated area from Franken (1969)

- Fig. 19 Reconstruction drawing

of the ‘pillared house’ at Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

Reconstruction of the ‘pillared house’ at Tall Dayr ‘Allå

(drawn by Ali Omari)

Kafafi (2009)

- Plate IVa Phase C Earthquake

Crack from Franken (1969)

Plate IVa

Plate IVa

Photograph of section 5.50/15.50-20, with earthquake crack, dated to phase C

Franken (1969) - Plate IVb Phase C Earthquake

Crack drawing from Franken (1969)

Plate IVb

Plate IVb

Section Drawing of section 5.50/15.50-20, with earthquake crack, dated to phase C

Franken (1969) - Plate Va Seismic displacements

(Phases A-D) from Franken (1969)

Plate Va

Plate Va

A typical section through phases A-D courtyard deposits. Section to the left cf. fig. 3. The black burnt deposit clearly shows the disruptions by the shifting of the earth. In the centre: collapsed sides of a pit. Looking S.

Franken (1969) - Plate Vb Phase B Flower

Structure and burnt floors in Trench D from Franken (1969)

Plate Vb

Plate Vb

Trench D, looking s. Foreground phase A courtyards. Burnt floor of B 1 furnance. Top left the round tower, (wall K 13), cut through wall F (G) 8. Below the round tower remains of wall E 7 and phase D courtyards.

Franken (1969) - Figure 21 The same Phase B

Flower Structure and burnt floors in Trench D from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 21

Figure 21

Trench D100, looking south from D500. Visible is the heavily burnt surface of one of the installations (also visible in figure 18), and the various earthquake cracks complicating the stratigraphy in this part of the tell

(from the Tell Deir ‘Alla archive).

Halbertsma (2019) - Figure 6 Trench D Excavation

from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Excavating in Trench D, the 30-meter section trench, looking east

from the Tell Deir ‘Alla archive).

Halbertsma (2019) - Plate VIb Phase A Flower

Structure from Franken (1969)

Plate VIb

Plate VIb

Phase A accumulation over the red burnt L.B. ruins. Thick ash deposit (D 908), interrupted by pits and cracks.

Franken (1969) - Plate IXa Reed foundation and

cracks from Franken (1969)

Plate IXa

Plate IXa

Wall F 8 in section, showing the reed 'foundation' and cracks running through it

Franken (1969) - Plate IXb Bowed Walls

from Franken (1969)

Plate IXb

Plate IXb

Wall J 3 and wooden beam underneath. On the left wall J 1

Franken (1969) - Plate Xa Phase J road levels

from Franken (1969)

Plate Xa

Plate Xa

Phase J road levels, looking s. and stone pavement running along wall J 1

Franken (1969) - Plate Xb Phase K wall

dug into ruins of wall F8 from Franken (1969)

Plate Xb

Plate Xb

Phase K, wall K 13, the round tower dug into the ruins of wall F 8

Franken (1969) - Plate XIa Phase M wall

from Franken (1969)

Plate XIa

Plate XIa

Phase M, wall M5

Franken (1969) - Plate XIb Phase M cistern

from Franken (1969)

Plate XIb

Plate XIb

Phase M cistern, showing the circular pattern of the compressed fill in the horizontal section.

Franken (1969) - Plate XII Fill of Phase M

cistern from Franken (1969)

Plate XII

Plate XII

Fill of Phase M cistern near the surface. In the centre, a wall of a house built on a clay deposit over the cistern with stone floor. In the burnt debris of this house, a mediaeval grave

Franken (1969) - Fig. 13 burned layer separating

the two Middle and Late Bronze Age phases from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

The burned layer, which separates the two phases

(photo by Yousef Zu‘bi)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 17 burned phase at the

south foot of the tall from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

General view of the burned phase at the south foot of the tall

(photo by Yousef Zu‘bi)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 18 four burned wooden

pillars and the stone pavement south of them from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

General view of the four burned wooden pillars and the stone pavement south of them

(photo by Yousef Zu‘bi)

Kafafi (2009) - Mudbrick photo by JW

- Fig. 5b Vertical excavation

at Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2023)

- Fig. 7 Stratigraphy of

Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2023)

- Plate IVa Phase C Earthquake

Crack from Franken (1969)

Plate IVa

Plate IVa

Photograph of section 5.50/15.50-20, with earthquake crack, dated to phase C

Franken (1969) - Plate IVb Phase C Earthquake

Crack drawing from Franken (1969)

Plate IVb

Plate IVb

Section Drawing of section 5.50/15.50-20, with earthquake crack, dated to phase C

Franken (1969) - Plate Va Seismic displacements

(Phases A-D) from Franken (1969)

Plate Va

Plate Va

A typical section through phases A-D courtyard deposits. Section to the left cf. fig. 3. The black burnt deposit clearly shows the disruptions by the shifting of the earth. In the centre: collapsed sides of a pit. Looking S.

Franken (1969) - Plate Vb Phase B Flower

Structure and burnt floors in Trench D from Franken (1969)

Plate Vb

Plate Vb

Trench D, looking s. Foreground phase A courtyards. Burnt floor of B 1 furnance. Top left the round tower, (wall K 13), cut through wall F (G) 8. Below the round tower remains of wall E 7 and phase D courtyards.

Franken (1969) - Figure 21 The same Phase B

Flower Structure and burnt floors in Trench D from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 21

Figure 21

Trench D100, looking south from D500. Visible is the heavily burnt surface of one of the installations (also visible in figure 18), and the various earthquake cracks complicating the stratigraphy in this part of the tell

(from the Tell Deir ‘Alla archive).

Halbertsma (2019) - Figure 6 Trench D Excavation

from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Excavating in Trench D, the 30-meter section trench, looking east

from the Tell Deir ‘Alla archive).

Halbertsma (2019) - Plate VIb Phase A Flower

Structure from Franken (1969)

Plate VIb

Plate VIb

Phase A accumulation over the red burnt L.B. ruins. Thick ash deposit (D 908), interrupted by pits and cracks.

Franken (1969) - Plate IXa Reed foundation and

cracks from Franken (1969)

Plate IXa

Plate IXa

Wall F 8 in section, showing the reed 'foundation' and cracks running through it

Franken (1969) - Plate IXb Bowed Walls

from Franken (1969)

Plate IXb

Plate IXb

Wall J 3 and wooden beam underneath. On the left wall J 1

Franken (1969) - Plate Xa Phase J road levels

from Franken (1969)

Plate Xa

Plate Xa

Phase J road levels, looking s. and stone pavement running along wall J 1

Franken (1969) - Plate Xb Phase K wall

dug into ruins of wall F8 from Franken (1969)

Plate Xb

Plate Xb

Phase K, wall K 13, the round tower dug into the ruins of wall F 8

Franken (1969) - Plate XIa Phase M wall

from Franken (1969)

Plate XIa

Plate XIa

Phase M, wall M5

Franken (1969) - Plate XIb Phase M cistern

from Franken (1969)

Plate XIb

Plate XIb

Phase M cistern, showing the circular pattern of the compressed fill in the horizontal section.

Franken (1969) - Plate XII Fill of Phase M

cistern from Franken (1969)

Plate XII

Plate XII

Fill of Phase M cistern near the surface. In the centre, a wall of a house built on a clay deposit over the cistern with stone floor. In the burnt debris of this house, a mediaeval grave

Franken (1969) - Fig. 13 burned layer separating

the two Middle and Late Bronze Age phases from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

The burned layer, which separates the two phases

(photo by Yousef Zu‘bi)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 17 burned phase at the

south foot of the tall from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

General view of the burned phase at the south foot of the tall

(photo by Yousef Zu‘bi)

Kafafi (2009) - Fig. 18 four burned wooden

pillars and the stone pavement south of them from Kafafi (2009)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

General view of the four burned wooden pillars and the stone pavement south of them

(photo by Yousef Zu‘bi)

Kafafi (2009) - Mudbrick photo by JW

- Fig. 5b Vertical excavation

at Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2023)

- Fig. 7 Stratigraphy of

Tall Dayr ‘Allå from Kafafi (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Chronological table of the periods represented at Tell Der 'Alla

(after van der Kooij 2009)

Kafafi and van der Kooij (2013)

| Phase | Equivalent Phase | Age | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | The medieval arabic graveyard on top of the tell was touched in the baulks only. Some of the graves, excavated before, were still partly left in them. One complete, though damaged, grave with a main part of the skeleton was found in the 1.5 m wide N - baulk of B/B5, on top of the remnants of the phase V E - W wall. The skeleton had at its feet a small stone, artefact with a waist-like middle part. |

||

| II | The characteristic pits of this phase were found in some of the baulks (partly) as well as probably in square B/C8. Substantial work on this phase was done in B/A9 and 10, in excavating the very large pit which was discovered in 1978 already. This pit (deposit nr. B/A 10.6) turned out to be partly 2.75 m deep. Large portions of the thick accumulation of red-brown courtyard layers of phase IV, through which this pit had been dug and which formed the edge of it, were broken off and fallen down into the pit, partly together with other fill. The reason for making this pit is still obscure. One might think of digging away the plant remains of phase IV as manure, but the pit went considerably below that phase as well. |

||

| III | not earlier than 4th c. BCE | The remnants of this phase are of the last building activities (as far as the evidence goes until now), which took place on the tell. Wall parts of a large building were found in 1978 right on top of the mound. Outside this building no architectural remains of this phase could be discerned. The walls and floors found in squares B/A 5 and 6, and B/B 5 and 6 in 1978, and previously attributed to phase III have to be connected with phase V. This gives a change in date attribution of this phase: not earlier than the 4th cent. B. C. |

|

| IV | The thick accumulation of red-brown plant matter, mixed with some earth ("courtyard layers") was dug away again on several places, especially in the baulks. Again no walls were found associated with these layers during this phase. At places it is clear that some irregular pits were made during the accumulation and filled again with the same kind of layers. Human activity during the accumulation is also clear from some pots and many potsherds found in the layers, and also from a sherd with some aramaic ink writing on it (It is a sherd of a jar written below the handle). However the sherd was found without any other sherd of the same jar around. |

||

| V | 5th/early 4th c. B.C. | Most of phase V had been excavated in the two previous seasons already. Some architecture was found as well as court¬yards with pits (silo's). See op. cit p. 70 fig 9. However several lacunae in the walls still existed. The walls in squares B/A5 and 6 and B/B5 and 6 had been built in the phase between V and VI (see below) and rebuilt (reused) in phase V. Wall B/A5.1 was a re-use of wall B/A5. 21, 29, 30, going together with B/A6.1 on top of B/A6.33. B/A5 and 6.1 had been attributed to phase III in the previous report. On the other hand a 10 m long wall, discovered in the N. baulks of B/B5 and 6 was contemporary with N-S wall B/A5.2, so belonging to phase V. Peculiar in this E-W wall was that a large stone with a cavity (for grinding?) was found in its foundation. The wall was well preserved with its one, partly two, rows of foundation stones, and four, partly five, courses of mudbrick left. |

|

| V/VI | around 600 BCE | Additional phase between V and VI - We had to decide to establish an intermediate phase to account for several courtyard layers, many pits and a reappraisal of the stratigraphy of the architectural evidence in squares B/A5 and 6 and B/B5 and 6. The architecture to be attributed to this phase is limited to the W. part of the excavated area, as it has been drawn in op.cit. p. 70, fig. 9, as attributed to phase V. Cf. Pl. XI for stone foundation of walls B/A5, 15, and 29. This phase started with digging away much of the preceding phase VI, e. g. in B/A8 and 9 and B/B8 and 9 (See section drawing fig. 3,and plan drawing of phase VI, fig. 4). This digging was possibly done in order to obtain clay for building. During the existence of this additional phase several other pits were made, e.g. in B/B9 and B/C8 (cf. Pl. XVIII). Some of them were filled with the same burnt debris of phase VI as was taken out. |

|

| VI | ~600 BCE | In addition to the architecture found in 1976/78 some more walls of phase VI were unearthed this season. See plan drawing (fig. 4), and see also plan drawing, (fig. 10) in the previous report. The architectural remains are still very fragmentary due to the large scale pit digging during subsequent phases. Most of these later pits are indicated on the plan drawing. The largest one is in the SW half of square B/B9 and the bordering squares (see also section drawing, fig. 3). It has a diameter of about 5.5 m. Phase VI itself had started with a large scale digging too. This is clear in squares B/B5 & 6. Much of the solid clay deposits of phase VII had been removed, and the resulting "pits" have been filled again with debris dump. Many sheep or goat bones were found on a surface in the lower part of this dump (Pl. XIII). There had been some leveling as well, and it is worth noticing that in most squares the surface of the beginning of phase VI was at about the same level (c. -202.40 m). |

|

| VII | B | ~700 BCE | Phase VII is up to now represented by solid courtyard layers of clay in squares B/B5 and 6 as well as normal wash and courtyard layers in B/C7 and 8 and B/A7. In B/A8 also stones are involved, out no clear wall foundation. The clay deposits in B/B6 are especially interesting, because they have many holes of pointed poles in and below the floors, (see Pl. XX, 1). The unexpected identity of the holes was understood by the fact that the object that had made them had pressed the clay layers in which it came sideward and downward. The poles had been standing close together in a certain order, but not all at the same time. The precise function of them remains obscure. Further digging more to the S may give clear suggestions. |

| VIII | The 8th phase has been touched in B/C6 7 and 8 only. There appears a very shallow remnant of it. The main feature is an almost 7 m. long double row of mudbricks (size 40 X 55 X 10 cm) going E-W, with in B/C6 a double N-S row of mudbricks making a corner. In B/C6 the rows have two courses of bricks each, and the bricks are made of the local yellow banded clay. It seems that the rows of bricks are two courses high everywhere. This would possibly mean that the brick-made construction had not been built higher originally, whatever its function might have been. |

||

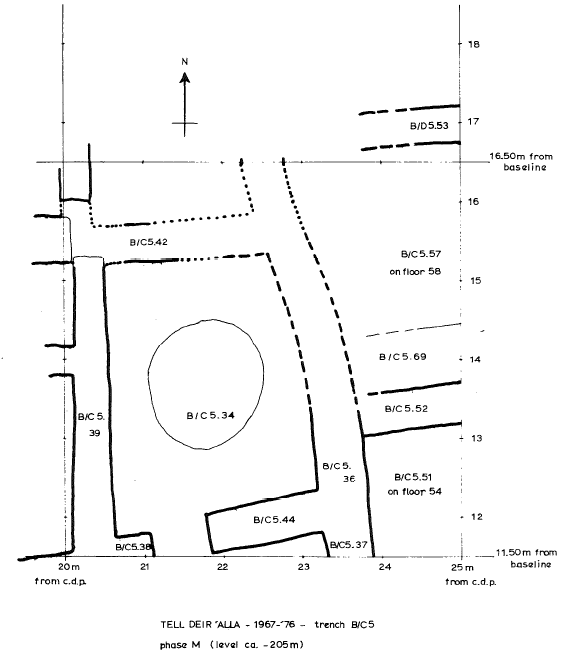

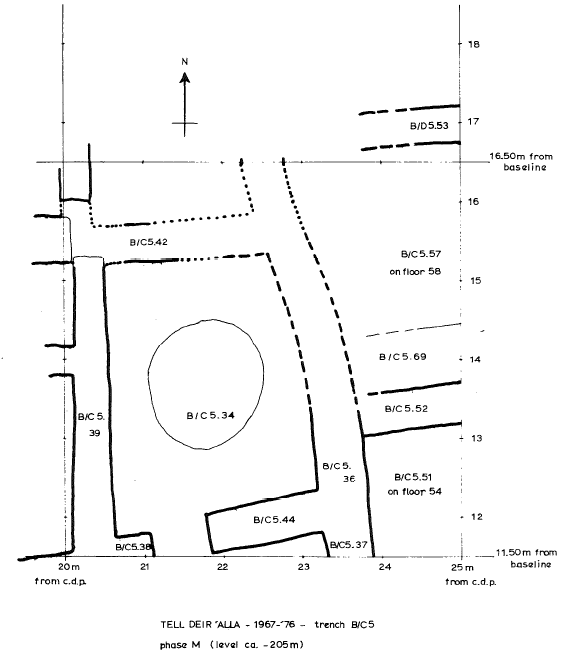

| IX | M | 8th century BCE | This phase IX is the same as phase M in previous countings. Much of it had been excavated in 1967 in an area of c. 25 X 25 m NW of the trenches dug during the last three seasons. Much of the architecture had been revealed, and some of it has been published preliminary in J. Hoftijzer, G. van der Kooij, Aramaic Texts from Deir 'Alla, Leiden, 1976, (Pls. 16-19) and in A.D.A J. op. cit. 1978, p. 64, fig. 6 (square B/C5). During this season excavations of phase M were done in one square only, namely in B/C6, to the E of B/C5, labelled EE 400 and EE 300 respectively in 1967. In 1967 it became clear that all the phase M architecture excavated had been destroyed by earth-shock and fire . The room found in B/C6 was destroyed by fire too. |

| Phase | Equivalent Phase | Age | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| X and XI | D | 1200 - 950 BCE ? | Equating X and XI with D comes from Van der Kooij (2006) |

| XII | E | ends c. 1200 BCE | Equating XII with E comes from Van der Kooij (2006) |

| XIII | H/G/F | Equating XIII with H/G/F comes from Van der Kooij (2006) |

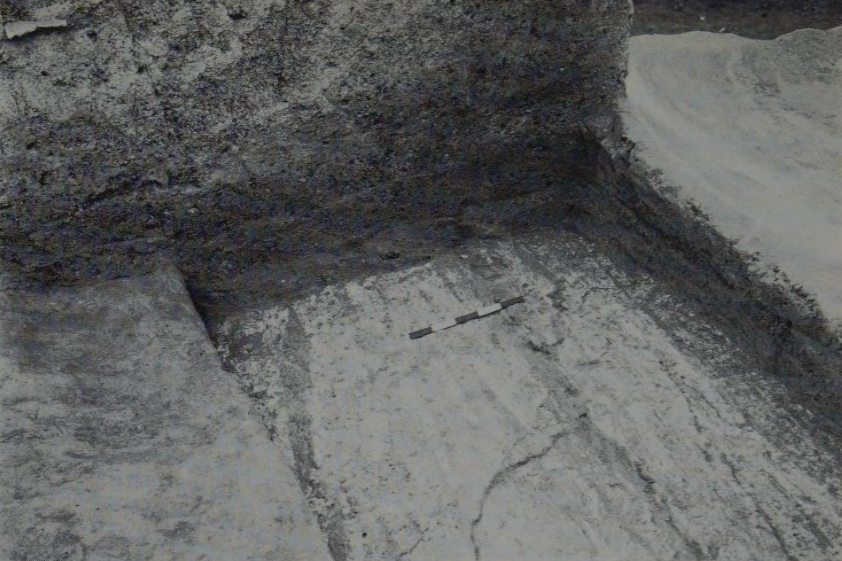

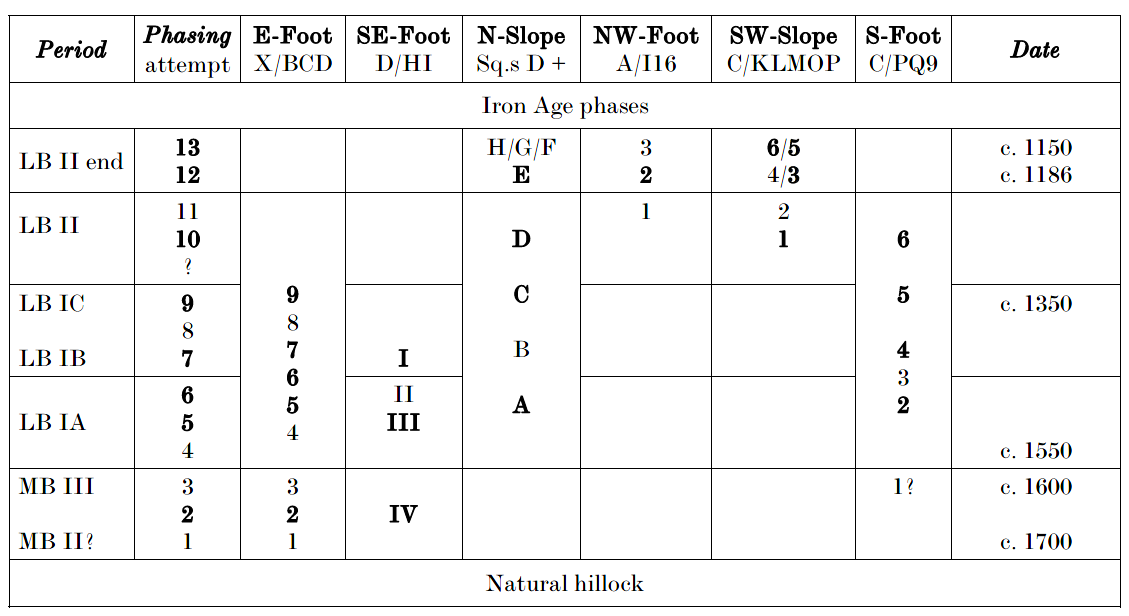

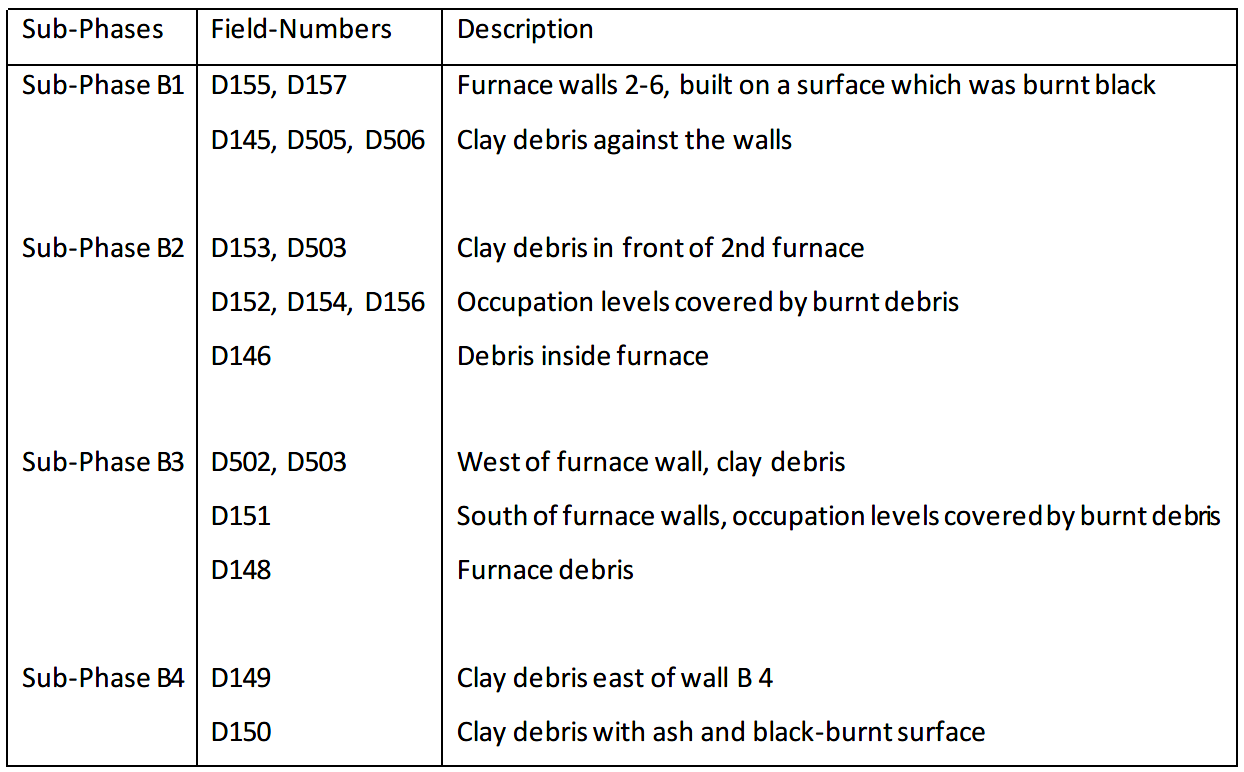

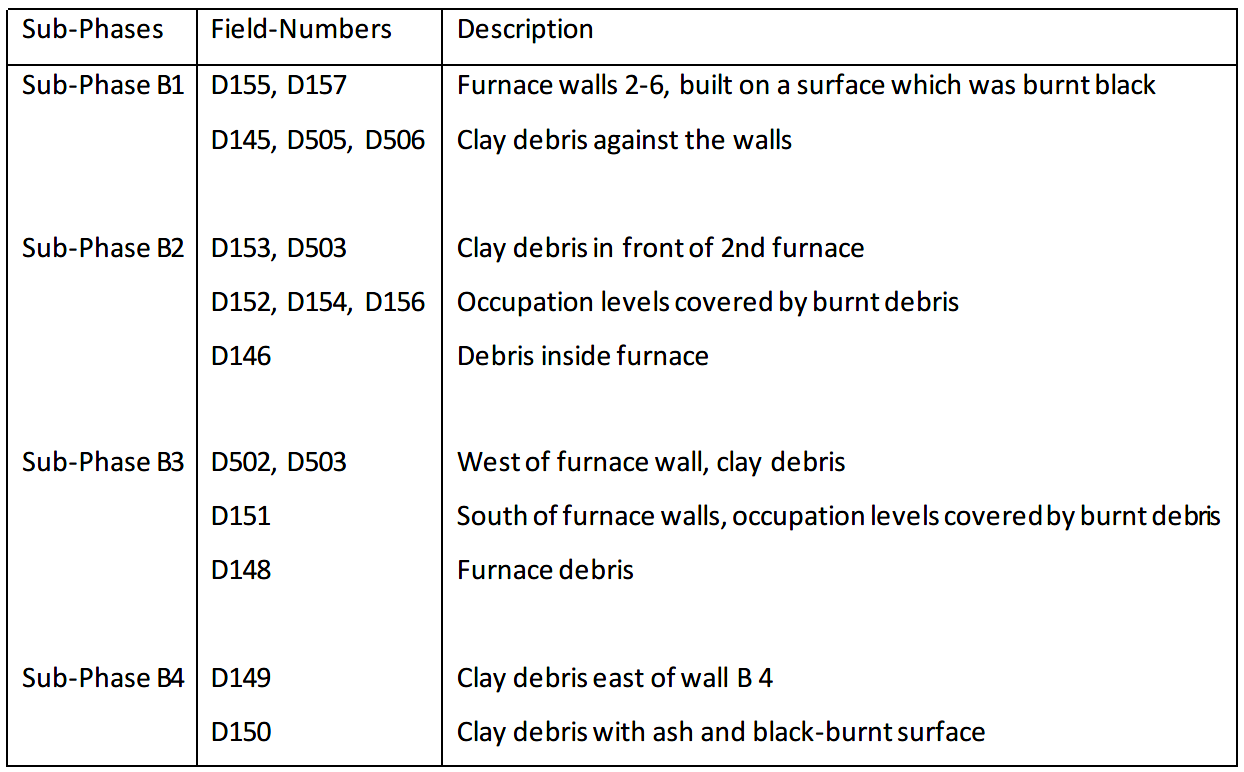

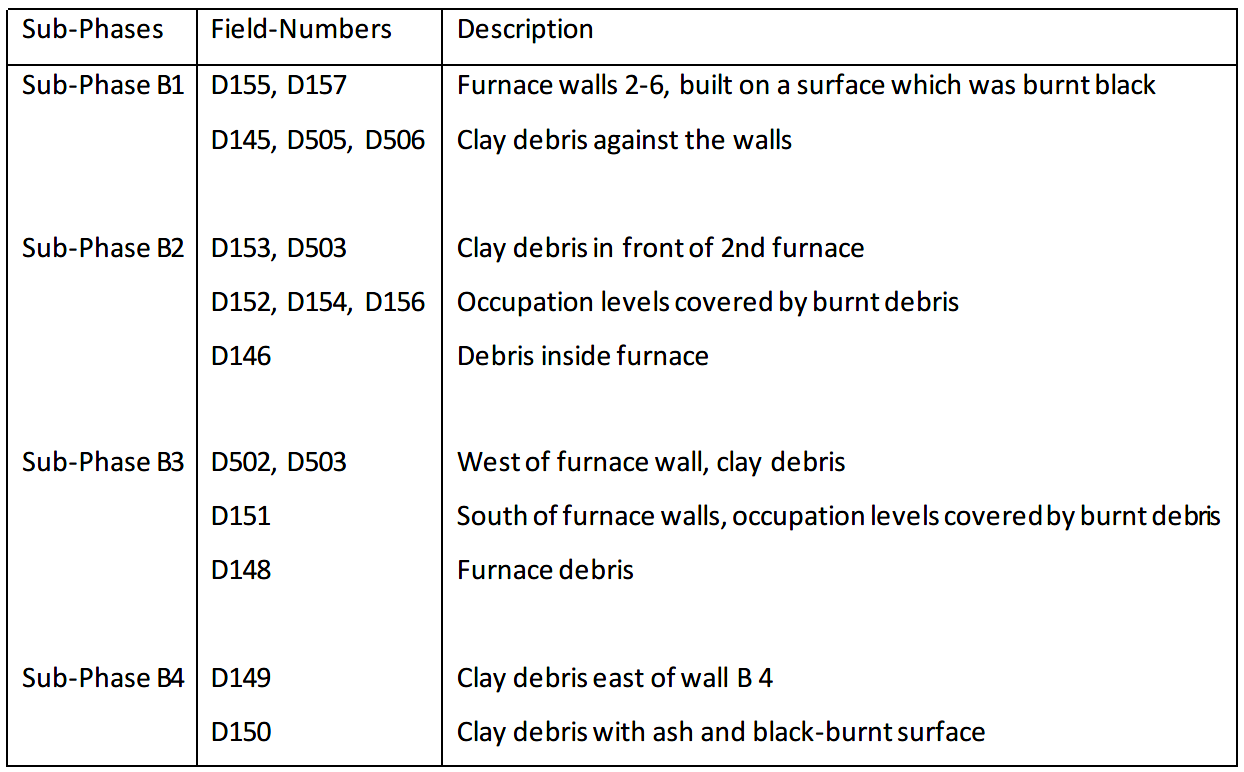

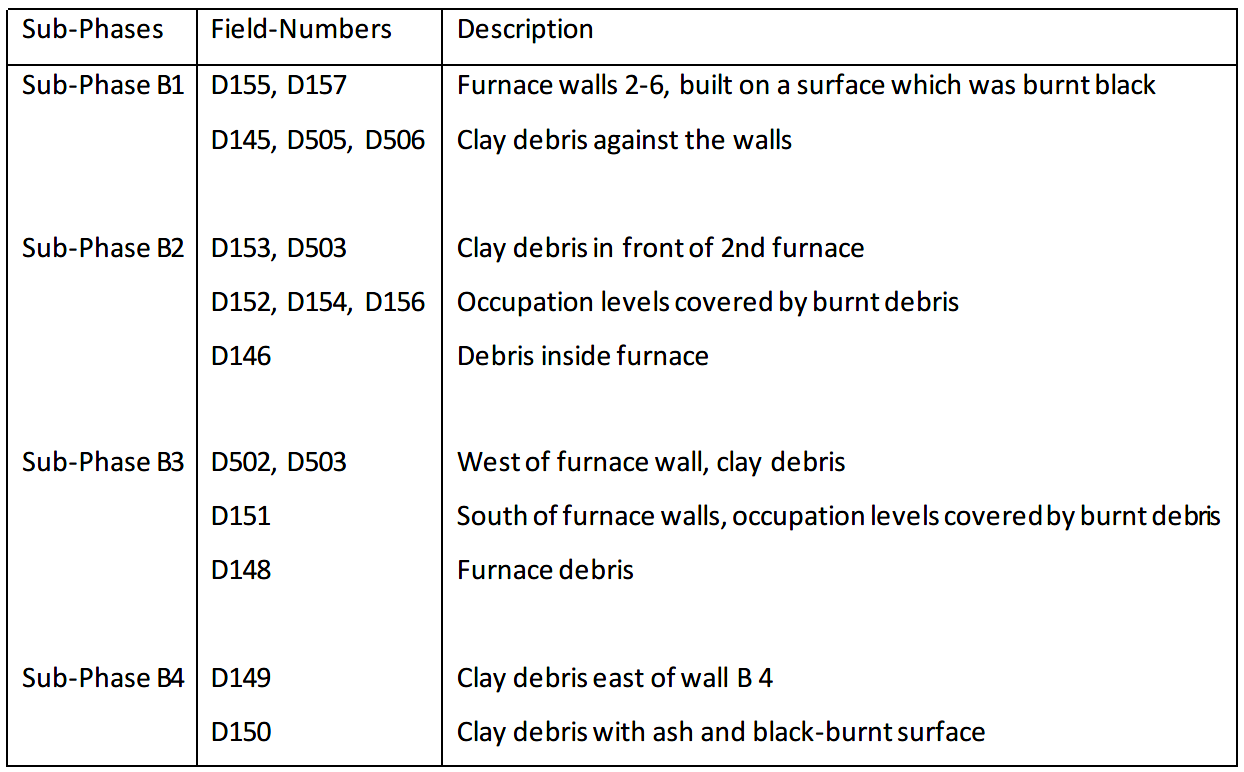

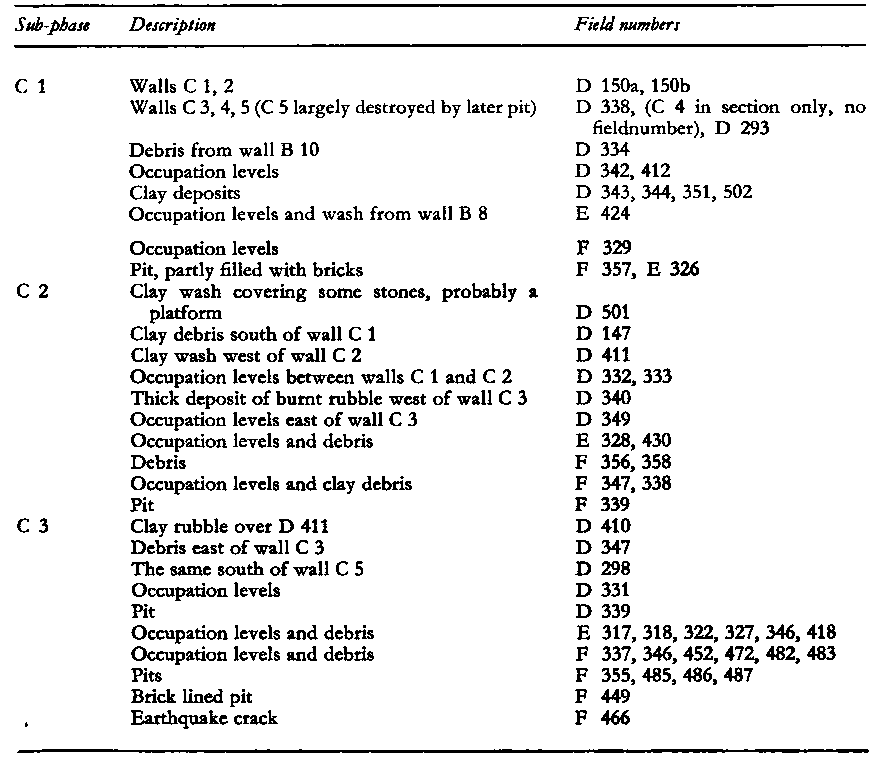

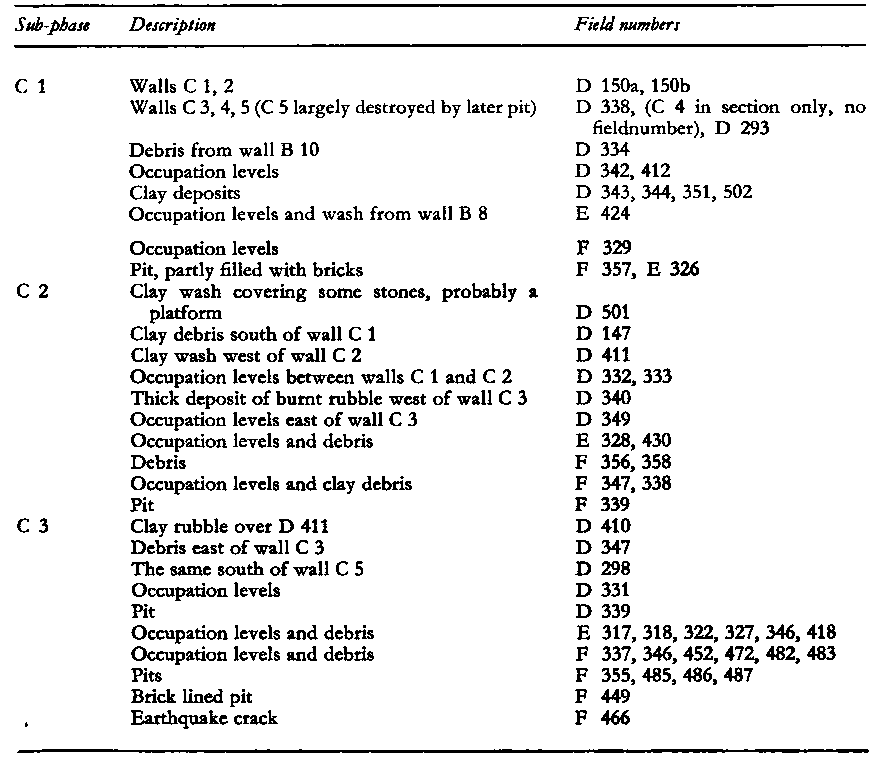

Franken published a list of deposits relating to Phase B in the 1969 publication, which is summarised below for Trench D

- from Halbertsma (2019)

Table 3

Table 3Subdivision of phases with corresponding field-numbers from Trench D100 and D500

(after Franken 1969, 39-40).

Halbertsma (2019)

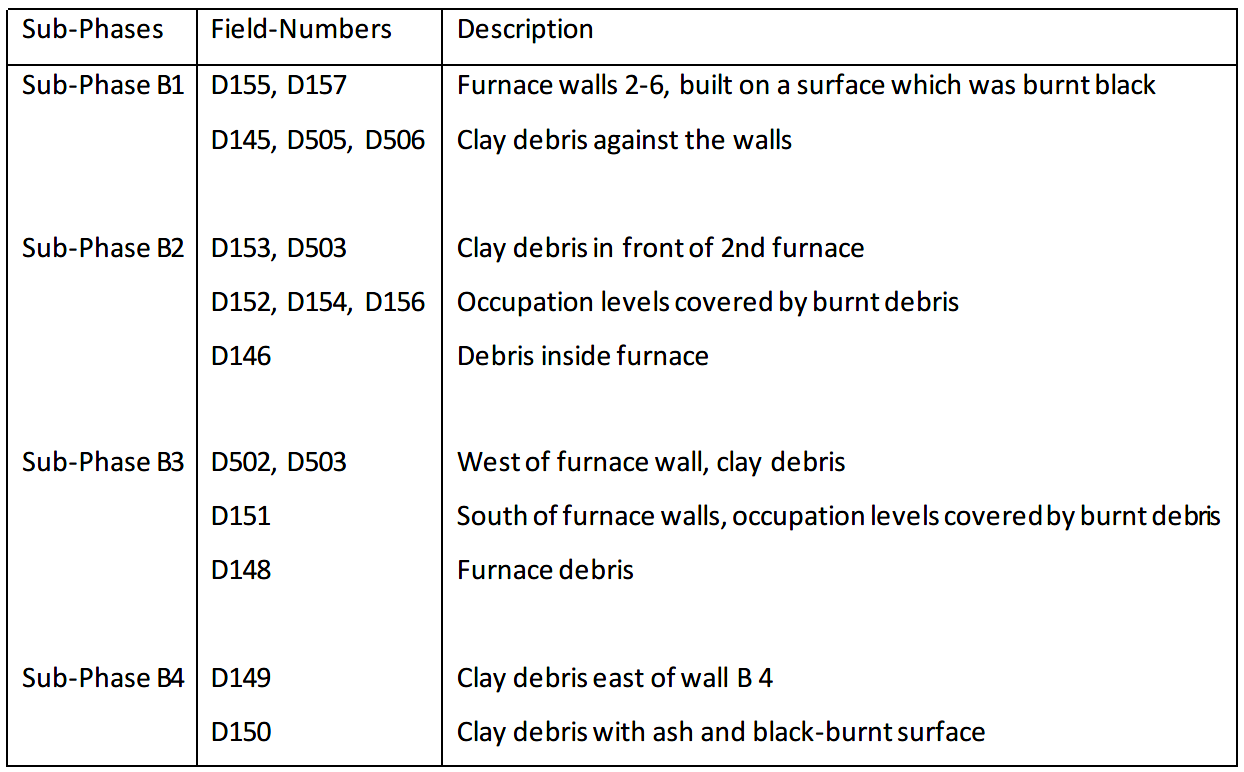

- from Van der Kooij (2006)

Table 2

Table 2Excavation and stratigraphic results: Phases A–G3 (from squares “F and L” in the west to “P600” in the east)

Footnote 3 Not all parts of the excavated field had stratigraphic connections through all phases.

Van der Kooij (2006)

- from Van der Kooij (2006)

Preliminary general phasing: an attempt to synchronize all fields’ phases9

Footnote 9 - The phases are distinguished according to features of partial or full collapse and rebuilding, as well as separate courtyard accumulations; a more limited rebuilding is taken as a sub-phase. Long term desertion of the site is not clearly noted. Bold types are used for major building phases, which may be synchronous. These distinctions are basically local, but four of them are indicated as multi-local or even general which is indicated by continuing horizontal lines in the table.

Van der Kooij (2006)

- from Fischer (2006)

The locations of the remains from the various periods are as follows:

- MB II (?)/III-LB IC at the eastern base of the tell

- MB II (?)/III-LB IB at the southeastern base of the tell

- LB IA-end of LB on the northern slope

- LB II at the north-western base and the south-western slope of the tell

- MB III (?)-LB II at the southern base of the tell (see p. 224 Table 10)

- the initial phase, viz. MB II/III

- the follow-up settlement which includes major parts of the LB I and II

- the final stage which ended with a general conflagration and only some limited rebuilding, viz. the end of the LB II

17 There are some occupational lacunae during the Iron Age.

- from Fischer (2006)

| Phase | Period | Dates | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-3 | MB II /III | see Table 10 - -The phases of the first settlement are Phases 1-3.

The first settlement was established on a low natural hill. Drill holes

and excavations suggested that the natural hill was probably limited

to what is at present the eastern and middle part of the tell. The small

excavated parts of the first settlement show quite solid mudbrick architecture

with walls of 1.0-1.5 m width, and with courtyards. One of the courtyards

includes a cooking area with bread ovens and often ash-rich occupation debris.

The well-constructed buildings had several rooms which show various

orientations in the different areas excavated. The function of the rooms

is not yet clear. A bent trident and a spearhead were found at the bottom

of a stone-lined pit in a niche-like space. The intentional deposition of

the disabled tools may point to cultic practices, although there are no

other indications of sacral activities. The distribution of the finds

suggests a minimum settlement size of approx. 200 X 100 m. There is a

possibility that the settlement was — at some stage — surrounded by an

earthen rampart, of which the northern part was turned into a terrace

to give an elevated position for the temple later on (see below).

A shaft-hole axe on a stone-paved area was found in the latest phase

of the Middle Bronze Age. The pottery from the first settlement (Phases 1-3) includes Chocolate-on-White, represented by a bowl with pronounced carination, and Tell el-Yahudiyeh Ware. Common ware bowls, too, show carinations, of various shapes but usually rather pronounced. Another shape is a bowl with a profile resembling that of the Eggshell Ware, a sub-group of the Chocolate-on-White Ware (Fischer in this volume), viz. a flaring S-shape. Cooking pots from the first settlement are of the "hole-mouth type" with some variations which mainly concern the stance of the rim, the earliest showing an inwardly curved upper part with a folded-over or thickened rim (Types 1-3). The other cooking pot types, with the typical flaring rim, with a number of variations (Type 4 and subtypes) also occurred. This type dominated during the entire Late Bronze Age. A Cypriote White Slip II bowl is obviously an intrusive find. |

|

| 4-13 | LB I-II | The Late Bronze Age is divided into Phases 4-13. Additional field work and

studies are necessary in order to evaluate the characteristics of the various

Late Bronze Age phases. These phases show local collapse and rebuilding processes,

but not necessarily any large-scale destruction during the Late Bronze Age nor a

prolonged period of erosion except for the general destruction very likely caused

by an earthquake which brought Phase 12 (= E) to an end. It appears that the

habitation was more or less continuous for some three centuries, though