Tel Rehov

(left) Aerial View of Tel Rehov from the northwest

(left) Aerial View of Tel Rehov from the northwestAreas C (left) and D (right, down the slope) are seen in the foreground and Areas B (left) and G (right) in the background

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com

(right) Aerial view of Tel Rehov from the southeast showing erosion that has taken place on this side of the Tel

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Drone photos taken by Jefferson Williams on 11 June 2023

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tel Rehov | Hebrew | תל רחוב |

| Tell es-Sarem | Arabic | تل الصارم |

| Ro-ob | Greek | Pσωβ |

| Rihib |

The excavations at Tel Rehov are part of the Beth Shean Valley Archaeological Project, which began in 1989 with the excavations at Tel Beth-Shean. Since 1997, the project has been made possible by the continuing sponsorship of John Camp of Minnesota. Eight seasons of excavations from 1997 to 2007 have been carried out at Tel Rehov.1 The focus of the investigations have been on the Iron Age IIA period (the tenth to ninth centuries BCE). Vast building remains from this period have been revealed in eight excavation areas representing various parts of the mound, and thus it can be concluded that the entire ten hectares of the mound were densely settled at this time. Following a severe destruction during the ninth century BCE, the lower city was abandoned in its entirety, while occupation continued on the upper mound until the Assyrian conquest at the end of the eighth century BCE.

Other periods revealed during the excavations include the Early Bronze Age III, when a mighty fortification surrounded part of the upper mound (Area H) and the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I, when a dense continuous occupation sequence was identified in the trench cut in the western slope of the lower city (Area D). Remains of Early Islamic occupation have been revealed on the summit of the upper city (Mazar 1999; 2003a; 2008; in press).

The Iron IIA architecture at Tel Rehov differs in both plan and technical details from the prevalent Iron Age II architecture typical of Israel. Virtually all the walls were constructed of mudbricks with no stone foundation, a phenomenon unknown from other contemporary sites. The buildings contained a wealth of finds, including hundreds of restorable ceramic vessels, seals, ivories, metal and stone objects, bones, flint, clay altars and shrines, figurines, and a profusion of organic material. These rich finds make Tel Rehov a major site for research into the Iron Age in northern Israel.

While Tel Rehov is not mentioned in the Bible, it figures in other ancient sources. Several texts dating to the Egyptian New Kingdom indicate that Rehov was the central city-state in the region in the Late Bronze Age, while nearby Beth-Shean was in fact no more than a small garrison town for the Egyptian administration at that time. A stele discovered at Beth-Shean relates how during a revolt against Pharaoh Seti I, Pehal (Pella, seven kilometers east of Tel Rehov), and Hammat (Tel el-Hammah in the Jordan Valley, just south of Tel Rehov) opposed the Egyptian domination, while Rehov chose to remain independent of the fracas and loyal to Egypt. The Taanach Letters and Papyrus Anastasi I, both second-millennium BCE texts, also mention Rehov in the Beth-Shean Valley. The town is also cited in the list of conquered towns during the campaign of Pharaoh Shoshenq I (biblical Shishak) in the late tenth century BCE.

1. The excavations have been carried out under the direction of Amihai Mazar on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University. Nava Panitz-Cohen was director of the excavations in Area C, which is the focus of this paper. In the study of the beehives we consulted the following beekeeping experts from the Ministry of Agriculture in Israel: H. Efrat, Y. Slabetsky, and Y. Weiss, as well as D. Namdar from the Weizmann Institute, Rehovot, and G. Bloch from the Institute of Life Sciences of the Hebrew University, who have conducted various studies of our finds.

Tel Rehov (Tell es-Sarem), the largest mound in the alluvial Beth-Shean Valley, is located about 6 km west of the Jordan River, 3 km east of the Gilboa Ridge, and 5 km south of Tel Beth-Shean. Rehov dominated the north–south road through the Jordan Valley. The site comprises an upper mound and a lower mound to its north, each covering about 12 a. The upper mound rises to 20 m above the surrounding plain, while the lower mound stands about 8 m above the plain; the summit of the upper mound is at an absolute elevation of 116 m below sea level. A ravine separates the two mounds; a gate may have been located in this ravine on the eastern side of the mound. The closest water source is a spring near the northeastern corner of the mound. Additional springs are found at short distances from the site.

In the early 1920s, P. Abel identified the site with Rehob mentioned in Egyptian texts. The identification is also based on the occurrence of the name in several other historical sources, on the name of the Byzantine Jewish town Rohob (Rehob) located at Ḥorvat Parva (Khirbet Farwana) northwest of the mound (see Vol. 4, pp. 1272–1274), and on the name of the Islamic tomb of Sheikh er-Rihab south of the mound. Surveys conducted by W. F. Albright, A. Bergman (Biran), and N. Zori indicated occupation at the site throughout the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Reḥov (Hebrew for “piazza” or “street”) was the name of several cities mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and other ancient Near Eastern sources. Two cities by that name in the western Galilee are referred to in the city lists of Asher (Josh. 19:28–30). An Aramean city and state of that name are mentioned in Syria, mainly in relation to David’s conquests (2 Sam. 10:6, 8). However, Rehov in the Beth-Shean Valley is never mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

Several Egyptian sources, however, do make mention of Rehov in the Beth-Shean Valley. The earliest is probably Rahabu in letter no. 2 from Taanach (fifteenth century BCE). In the stele of Seti I found at Beth-Shean (c. 1300 BCE), Pehel, Ḥamat, and Yeno‘am are mentioned as rebelling against the Egyptian administration, while Rehov remained loyal to the Pharaoh. In Papyrus Anastasi I (22:8; thirteenth century BCE), the Egyptian scribe refers to Rehov in relation to Beth-Shean and the crossing of the Jordan. Pharaoh Shishak’s list of conquered cities (c. 925 BCE) mentions Rehov (no. 17) after “the valley” and before Beth-Shean. Several other Egyptian sources refer to a city of this name in the Beth-Shean Valley or to Rehov in western Galilee. These include the execration texts, Tuthmosis III’s topographic list (no. 87; the latter two probably refer to the western Galilee); bronze vessels from a place called Rehov mentioned in a papyrus kept in Turin, Italy, which includes accounts dated to the Twentieth Dynasty; and a notation concerning the production of chariot parts at Rehov in Papyrus Anastasi IV (17:3).

The excavations at Tel Rehov were directed by A. Mazar on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and sponsored by J. Camp. The first six seasons took place between 1997 and 2003. Three excavation areas (A, B, H) were opened on the upper mound, and five (C, D, E, F, G) on the lower mound. Geophysical and geological surveys were also conducted. The number of strata varies in certain areas or sub-areas, and the correlation between them is tentative in certain cases. Yet an attempt was made to correlate local strata dating from the late Iron Age I and onwards in each of the excavation areas with seven general strata (VII–I), which also remain tentative in certain cases.

- Fig. 1.1 Location Map

for Tel Rehov from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.5)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Map of the geographic sub-regions, main Bronze and Iron Age sites and roads in the Central Jordan Valley. Key to sub-regions:

- Kinnarot Valley

- NE Beth-Shean Valley

- Northern Beth-Shean Valley

- Central Beth-Shean Valley

- Southern Beth-Shean Valley

- SE Beth-Shean Valley

- Harod Valley

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.5) - Location Map for Tel Rehov

from biblewalks.com

- Fig. 1.1 Location Map

for Tel Rehov from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.5)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Map of the geographic sub-regions, main Bronze and Iron Age sites and roads in the Central Jordan Valley. Key to sub-regions:

- Kinnarot Valley

- NE Beth-Shean Valley

- Northern Beth-Shean Valley

- Central Beth-Shean Valley

- Southern Beth-Shean Valley

- SE Beth-Shean Valley

- Harod Valley

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.5) - Location Map for Tel Rehov

from biblewalks.com

- Annotated Satellite View of

Tel Rehov and environs from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Tel Rehov and environs

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Tel Rehov and environs

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Annotated Satellite View of

Tel Rehov showing excavation areas from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Tel Rehov showing excavation areas

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Tel Rehov showing excavation areas

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Photo 3.1 Aerial Photo from

1945 showing Tel Rehov and vicinity from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Photo 3.1

Photo 3.1

Tel Rehov and its surroundings

- the tell is in the center

- the village of Fawarna (the location of Byzantine Rehob [Ro-ob (Pσωβ) of Eusebius]) is in the upper left

- the line of modern Route 90 is seen in the upper left

(aerial photo taken by the British Royal Air Force in 1945; courtesy of the Department of Geography, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Aerial View of Tel Rehov

from biblewalks.com

Aerial View of Tel Rehov from the northwest

Aerial View of Tel Rehov from the northwest

JW from Mazar: Areas C (left) and D (right, down the slope) are seen in the foreground and Areas B (left) and G (right) in the background

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Wide Aerial View of Tel Rehov from the northwest from Jefferson Williams

- Photo 3.7 Aerial Photo of Tel

Rehov showing eroded ravine on the eastern slope from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Photo 3.7

Photo 3.7

Tel Rehov, looking northwest towards Beth-Shean and the Harod Valley. Note the ravine between the upper and lower mound and the damaged area on the eastern part of the upper mound; note also the hump on the western part of the upper mound, where the Early Bronze fortification and the Islamic village are located

(Photo: Albatross; 2003)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Photo 3.8 Another Aerial Photo

of Tel Rehov showing eroded ravine on the eastern slope from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Photo 3.8

Photo 3.8

Tel Rehov, looking west towards the Gilboa ridge. Note the ravine between the upper and lower mound and the damaged area on the eastern part of the upper mound. The green area on the far right marks the spring closest to the mound

(Photo: Albatross; 2003)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Tel Rehov in Google Earth

- Tel Rehov on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated Satellite View of

Tel Rehov and environs from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Tel Rehov and environs

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Tel Rehov and environs

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Annotated Satellite View of

Tel Rehov showing excavation areas from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Tel Rehov showing excavation areas

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Tel Rehov showing excavation areas

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Photo 3.1 Aerial Photo from

1945 showing Tel Rehov and vicinity from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Photo 3.1

Photo 3.1

Tel Rehov and its surroundings

- the tell is in the center

- the village of Fawarna (the location of Byzantine Rehob [Ro-ob (Pσωβ) of Eusebius]) is in the upper left

- the line of modern Route 90 is seen in the upper left

(aerial photo taken by the British Royal Air Force in 1945; courtesy of the Department of Geography, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Aerial View of Tel Rehov

from biblewalks.com

Aerial View of Tel Rehov from the northwest

Aerial View of Tel Rehov from the northwest

JW from Mazar: Areas C (left) and D (right, down the slope) are seen in the foreground and Areas B (left) and G (right) in the background

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Wide Aerial View of Tel Rehov from the northwest from Jefferson Williams

- Photo 3.7 Aerial Photo of Tel

Rehov showing eroded ravine on the eastern slope from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Photo 3.7

Photo 3.7

Tel Rehov, looking northwest towards Beth-Shean and the Harod Valley. Note the ravine between the upper and lower mound and the damaged area on the eastern part of the upper mound; note also the hump on the western part of the upper mound, where the Early Bronze fortification and the Islamic village are located

(Photo: Albatross; 2003)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Photo 3.8 Another Aerial Photo

of Tel Rehov showing eroded ravine on the eastern slope from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Photo 3.8

Photo 3.8

Tel Rehov, looking west towards the Gilboa ridge. Note the ravine between the upper and lower mound and the damaged area on the eastern part of the upper mound. The green area on the far right marks the spring closest to the mound

(Photo: Albatross; 2003)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Tel Rehov in Google Earth

- Tel Rehov on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 3.7 Map of the site

showing grid and excavation areas from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7

Topographic map of Tel Rehov showing the grid and excavated areas. Note that levels are given in actual elevation below sea level followed by the relative levels used by our excavation

(triangulation point -116.26 considered as +100m)

(topography and grid by Mabat, Digital Mapping, Jerusalem; areas added by Jay Rosenberg)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

- Fig. 3.7 Map of the site

showing grid and excavation areas from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7

Topographic map of Tel Rehov showing the grid and excavated areas. Note that levels are given in actual elevation below sea level followed by the relative levels used by our excavation

(triangulation point -116.26 considered as +100m)

(topography and grid by Mabat, Digital Mapping, Jerusalem; areas added by Jay Rosenberg)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

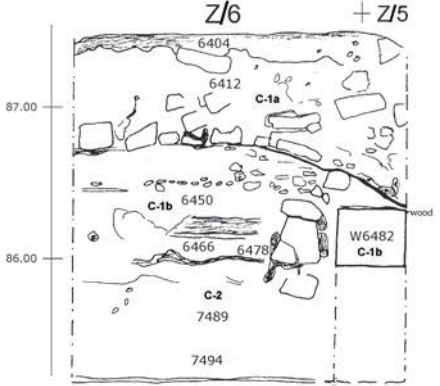

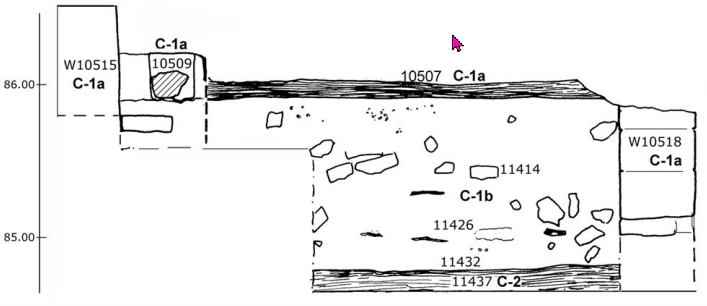

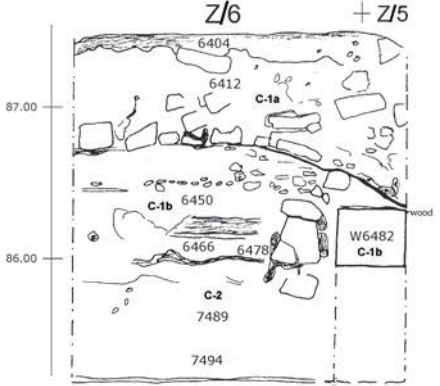

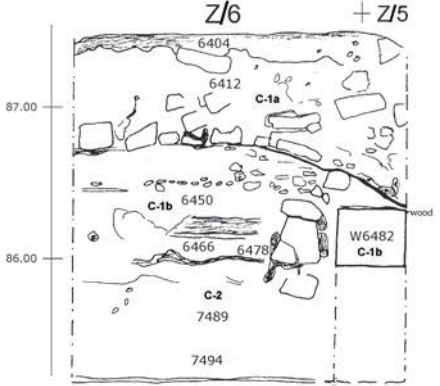

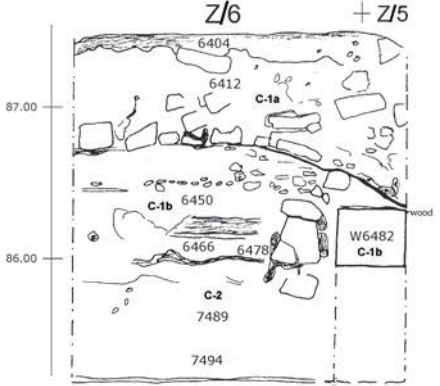

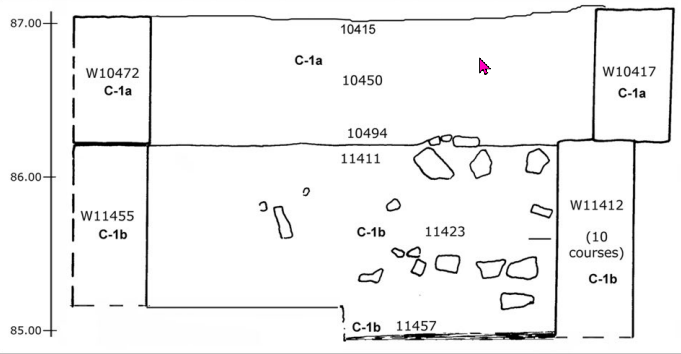

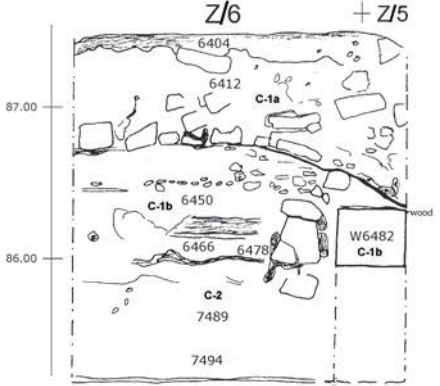

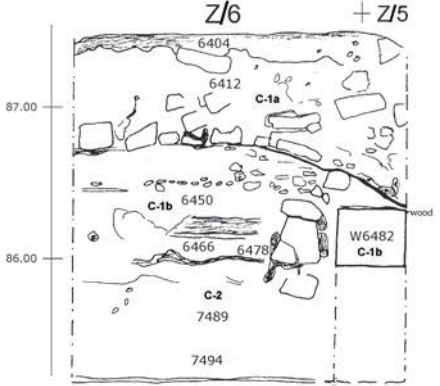

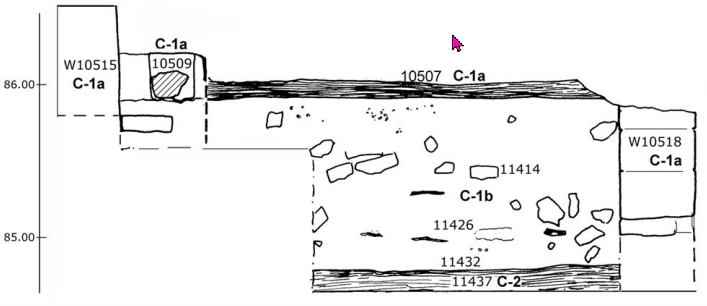

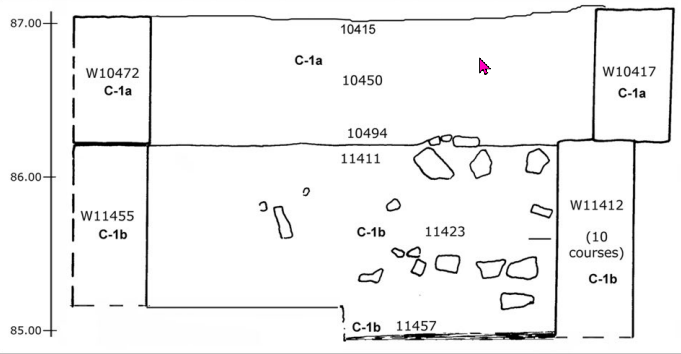

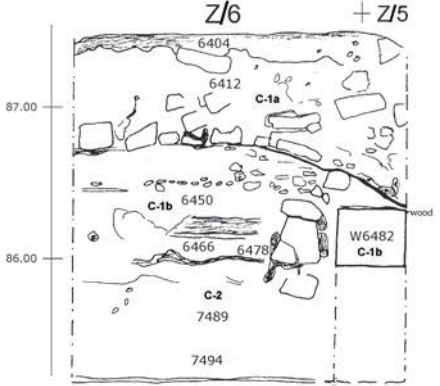

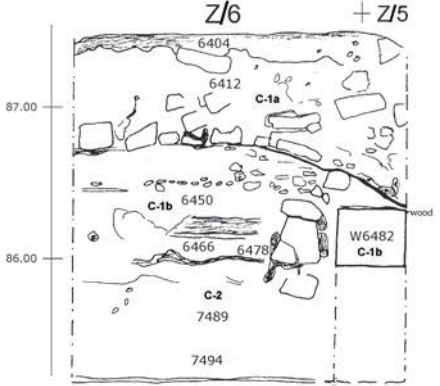

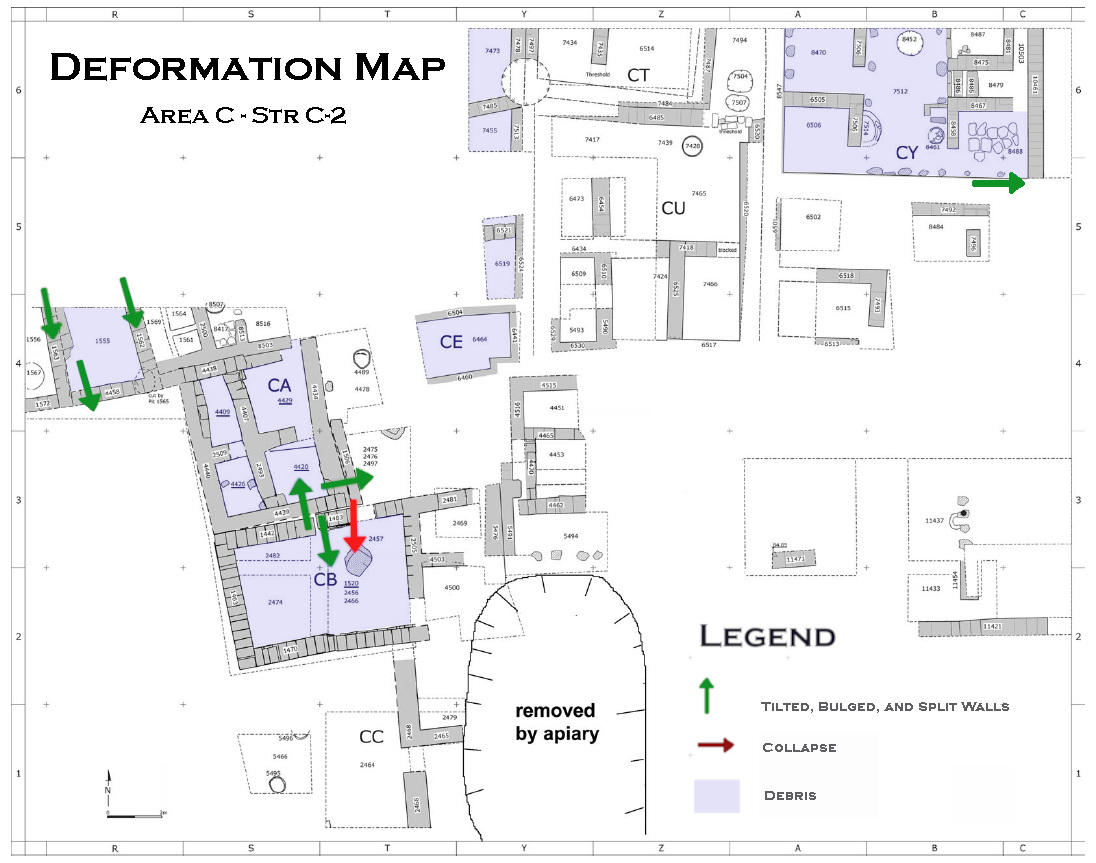

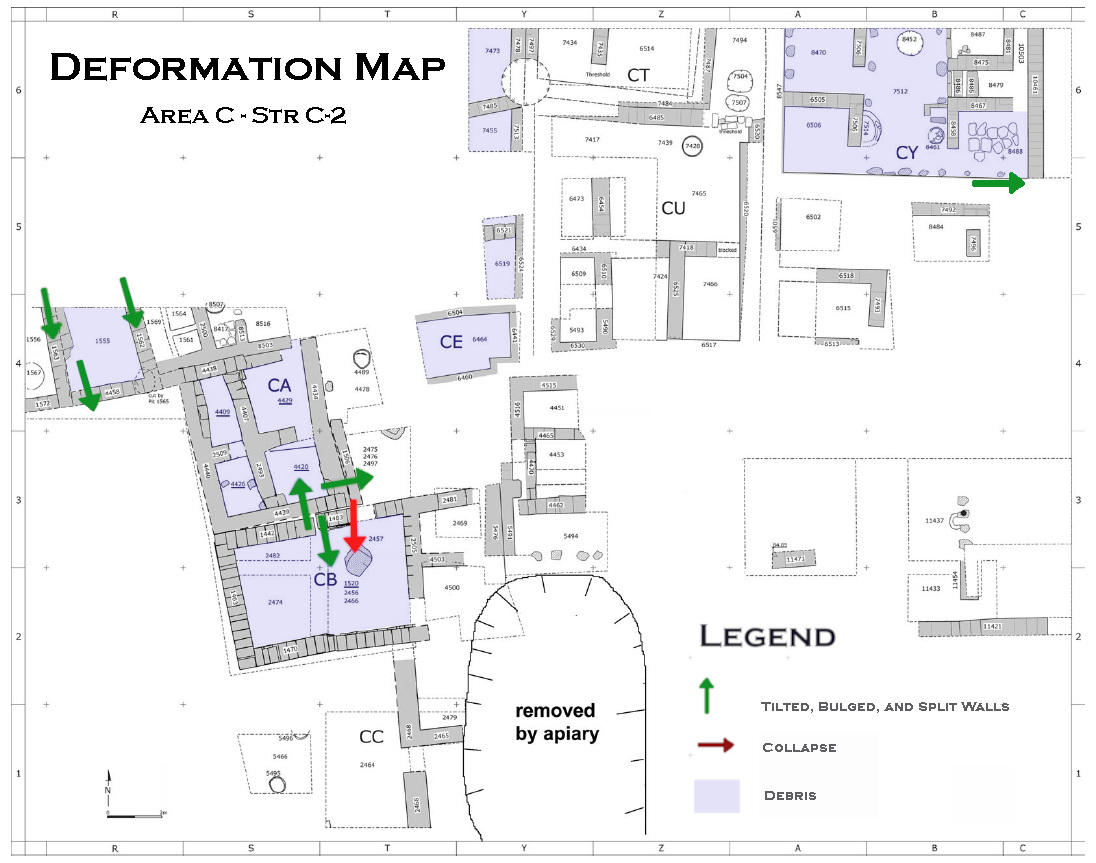

- Fig. 12.7

Plan of Stratum C-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

Fig. 12.7

Fig. 12.7

Plan of Stratum C-2 (1:250); for the continuation of this stratum in Area D, see Fig. 15.28

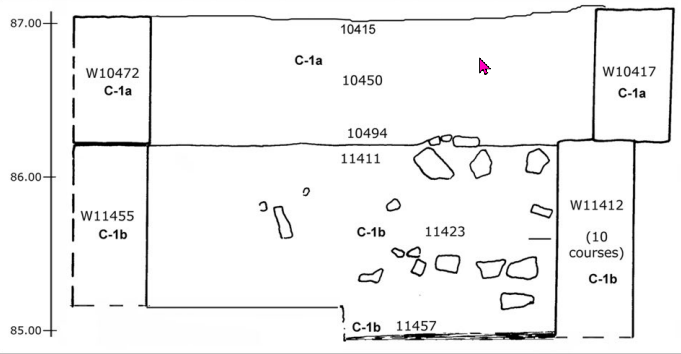

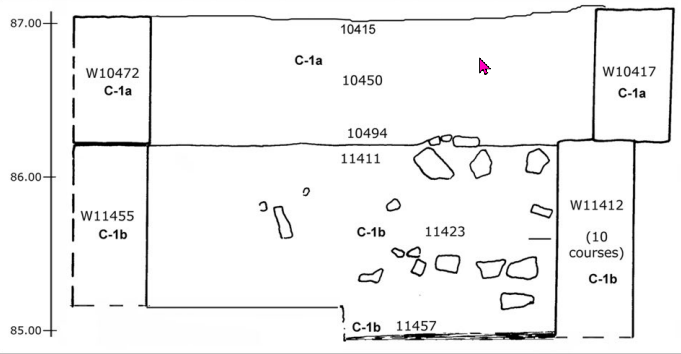

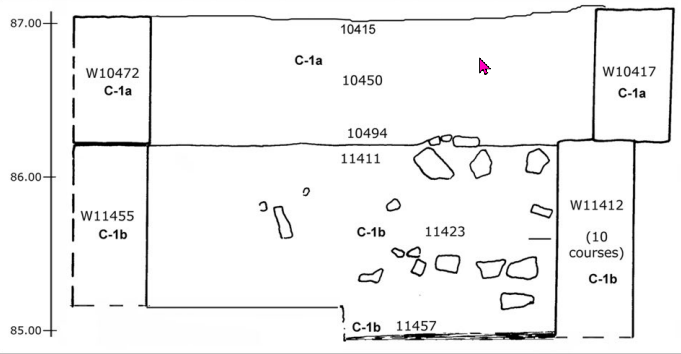

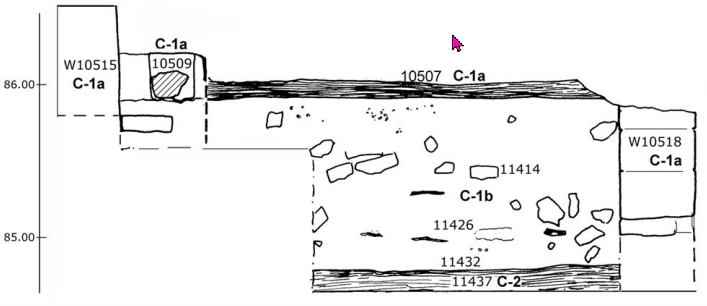

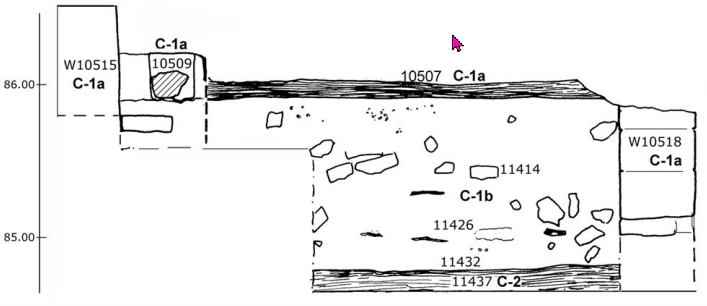

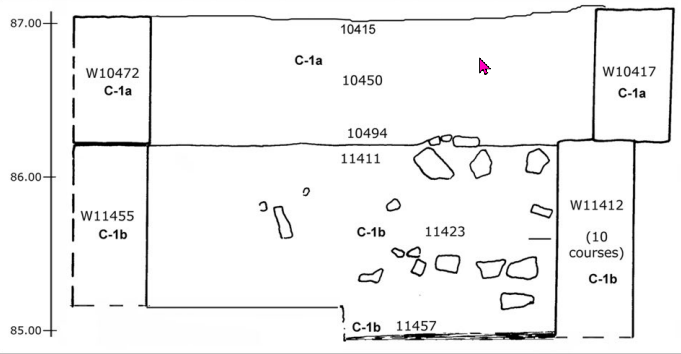

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2) - Fig. 12.18

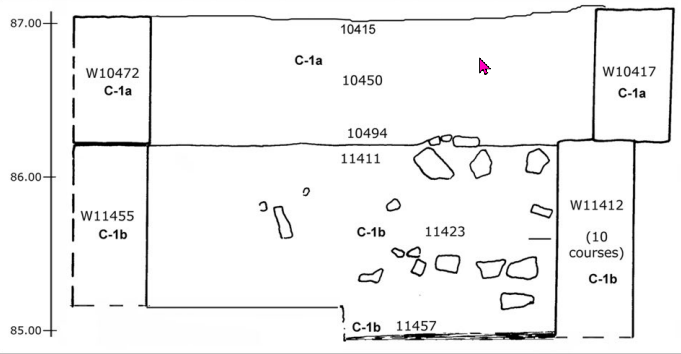

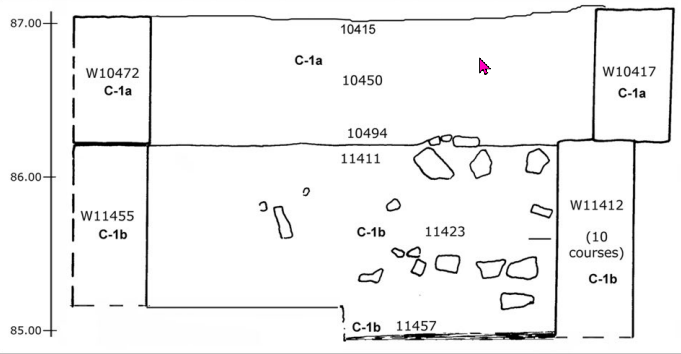

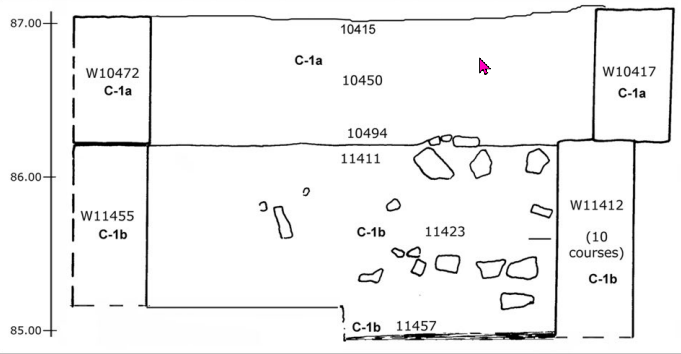

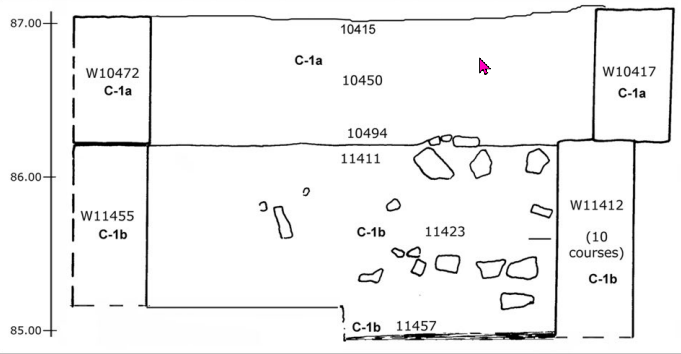

Plan of Stratum C-1b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

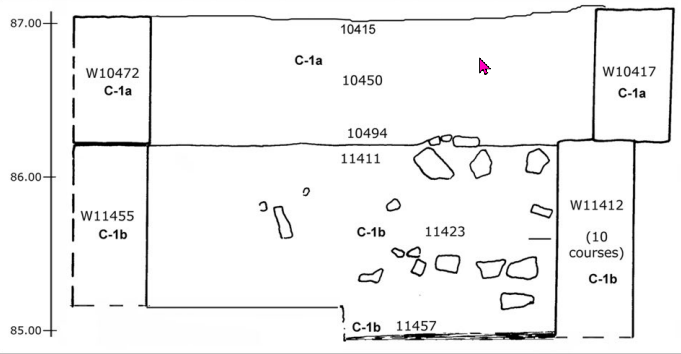

Fig. 12.18

Fig. 12.18

Plan of Stratum C-1b (1:200)

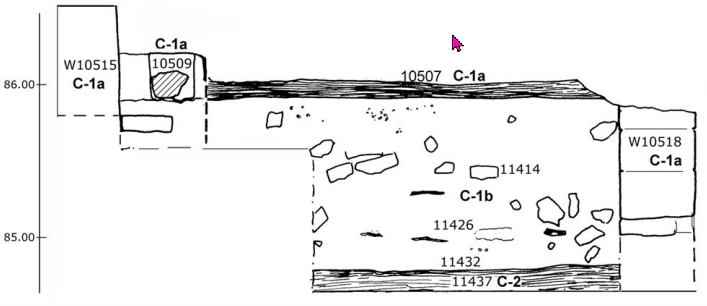

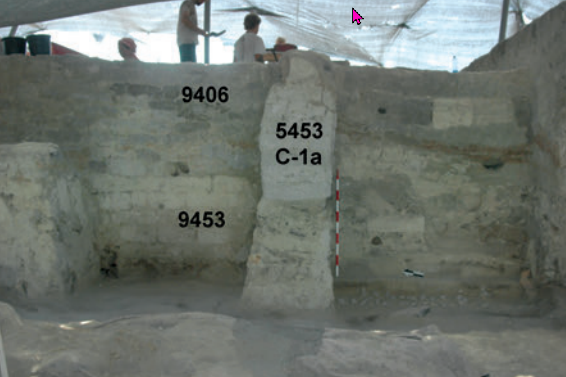

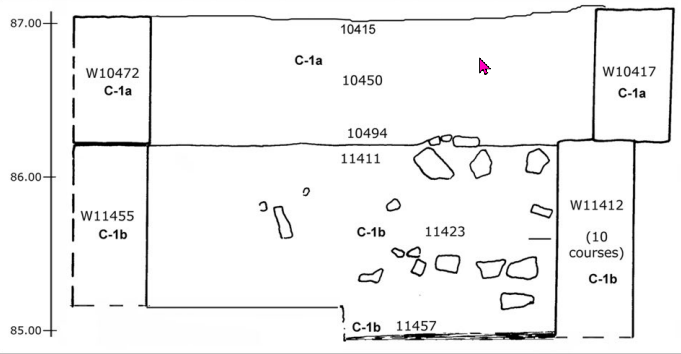

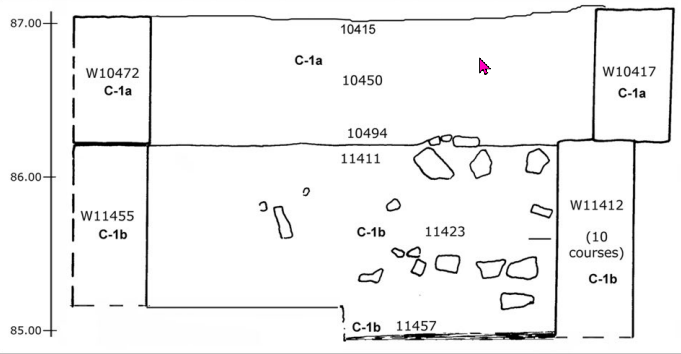

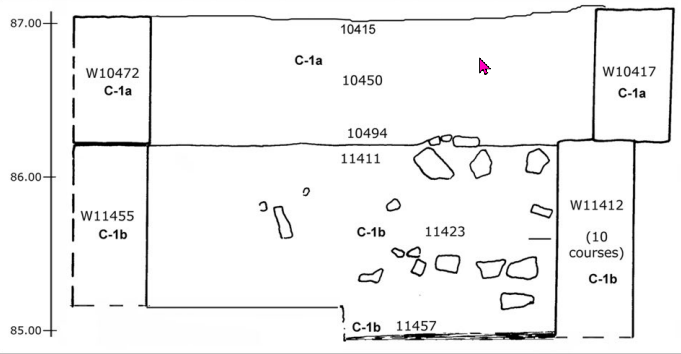

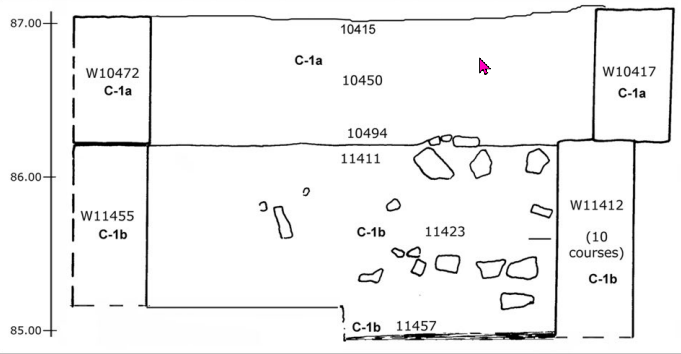

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2) - Fig. 12.19

Plan of Stratum C-1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

Fig. 12.19

Fig. 12.19

Plan of Stratum C-1a (1:200)

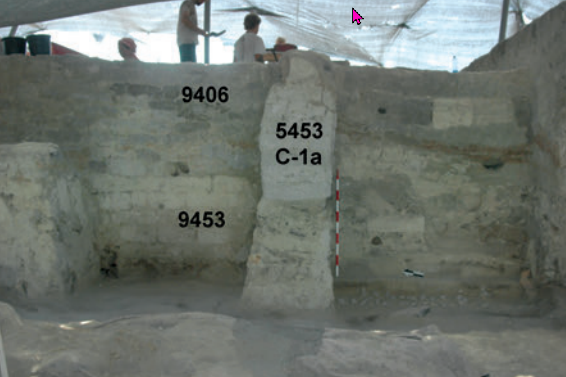

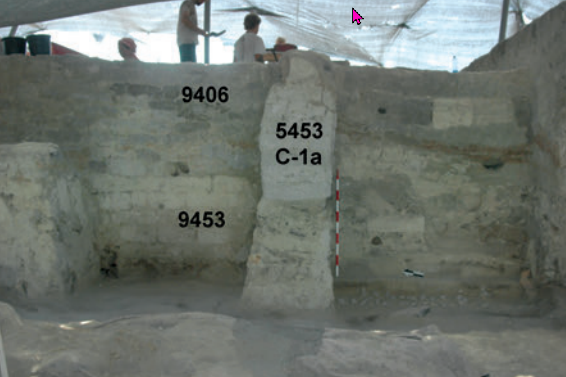

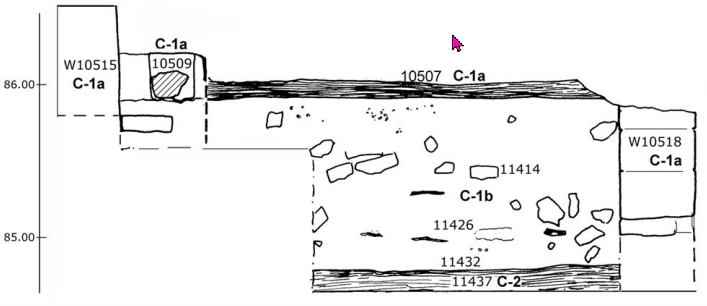

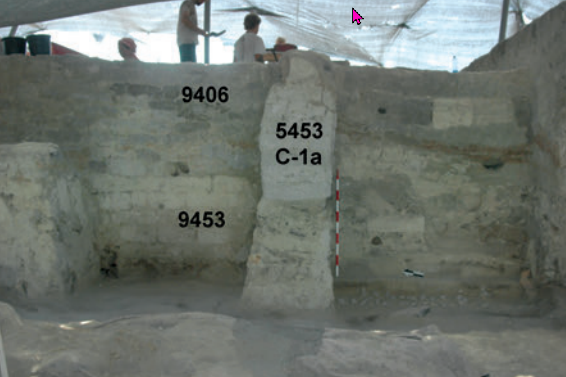

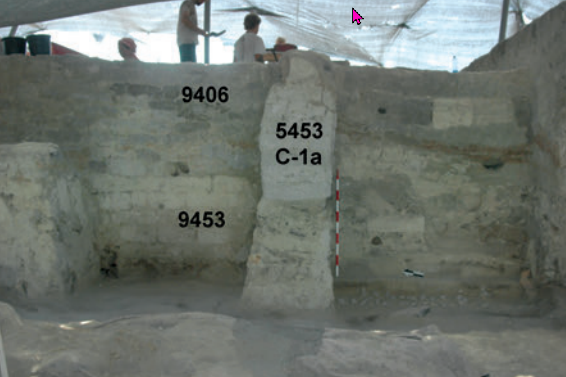

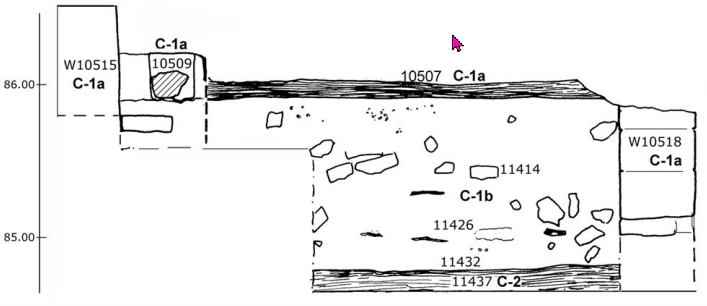

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2) - Fig. 12.23

Isometric view of Area C, Stratum C-1a, looking northwest from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

Fig. 12.23

Fig. 12.23

Isometric view of Area C, Stratum C-1a, looking northwest

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

- Fig. 12.7

Plan of Stratum C-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

Fig. 12.7

Fig. 12.7

Plan of Stratum C-2 (1:250); for the continuation of this stratum in Area D, see Fig. 15.28

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2) - Fig. 12.18

Plan of Stratum C-1b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

Fig. 12.18

Fig. 12.18

Plan of Stratum C-1b (1:200)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2) - Fig. 12.19

Plan of Stratum C-1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

Fig. 12.19

Fig. 12.19

Plan of Stratum C-1a (1:200)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2) - Fig. 12.23

Isometric view of Area C, Stratum C-1a, looking northwest from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

Fig. 12.23

Fig. 12.23

Isometric view of Area C, Stratum C-1a, looking northwest

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

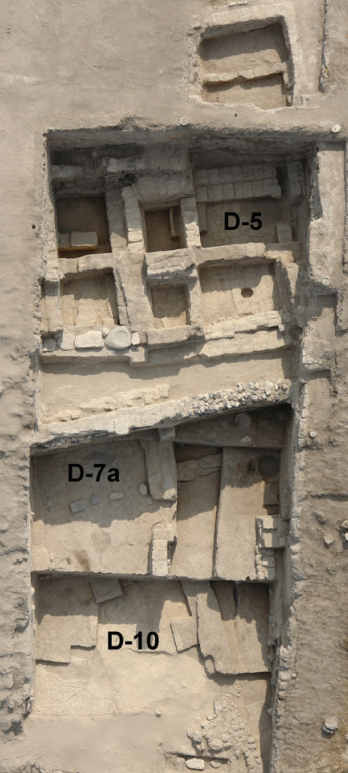

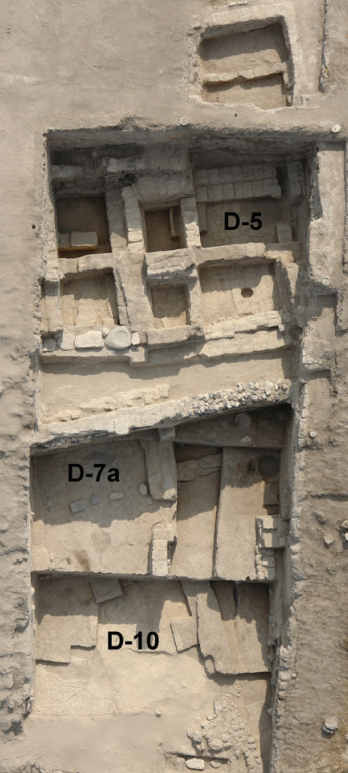

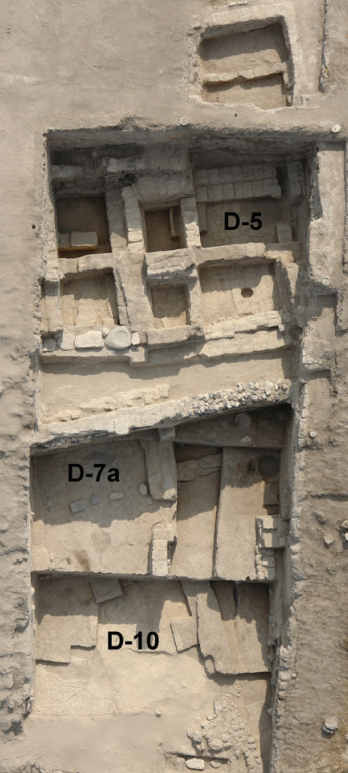

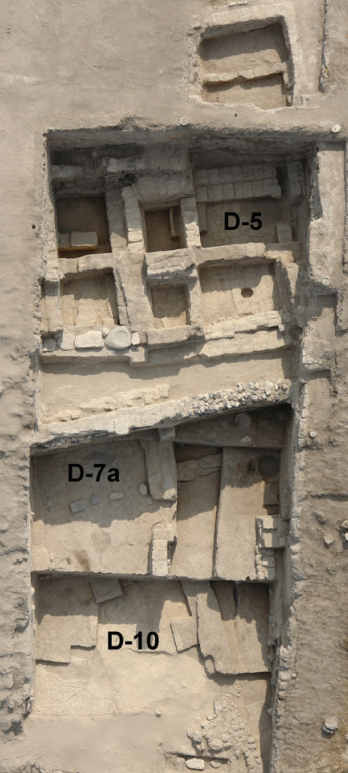

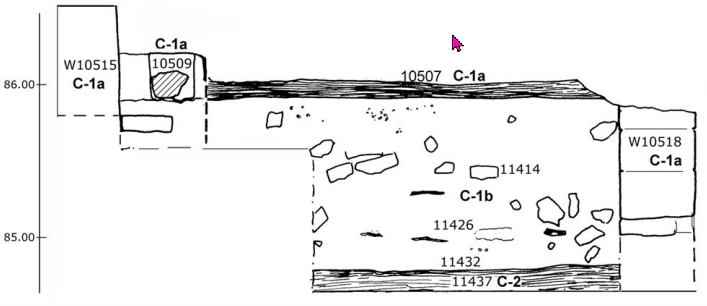

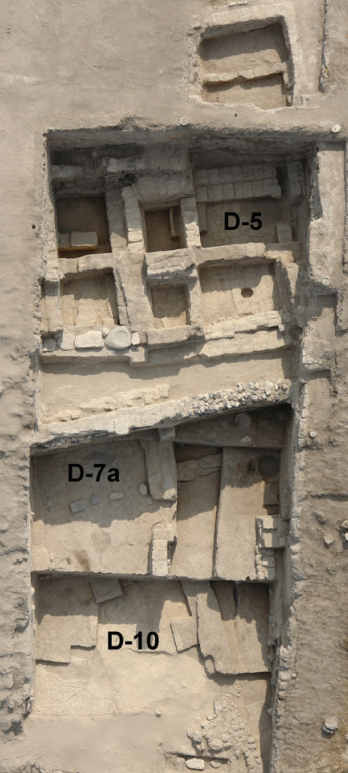

- Fig. 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.2

Schematic section of Area D from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2

Schematic section of Area D

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.3

Plan of Stratum D-11b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.3

Figure 15.3

Plan of Stratum D-11b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.4

Plan of Stratum D-11a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.4

Figure 15.4

Plan of Stratum D-11a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.5

Plan of Stratum D-10 constructional fills from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.5

Figure 15.5

Plan of Stratum D-10 constructional fills

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.6

Plan of Stratum D-10 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.6

Figure 15.6

Plan of Stratum D-10

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.7

Plan of Stratum D-9b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.7

Figure 15.7

Plan of Stratum D-9b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.8

Plan of Stratum D-9a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.8

Figure 15.8

Plan of Stratum D-9a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.9

Plan of Stratum D-8 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.9

Figure 15.9

Plan of Stratum D-8

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.10

Plan of Stratum D-8' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.10

Figure 15.10

Plan of Stratum D-8'

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.11

Plan of post Stratum D-8 fills from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.11

Figure 15.11

Plan of post Stratum D-8 fills

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.12

Plan of Stratum D-7b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.12

Figure 15.12

Plan of Stratum D-7b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.13

Plan of Stratum D-7a (encircled numbers denote foundation deposits as listed in the text) from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.13

Figure 15.13

Plan of Stratum D-7a (encircled numbers denote foundation deposits as listed in the text)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.14

Plan of Stratum D-7a' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.14

Figure 15.14

Plan of Stratum D-7a'

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.15

Plan of Stratum D-6b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.15

Figure 15.15

Plan of Stratum D-6b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.16

Plan of Stratum D-6a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.16

Figure 15.16

Plan of Stratum D-6a

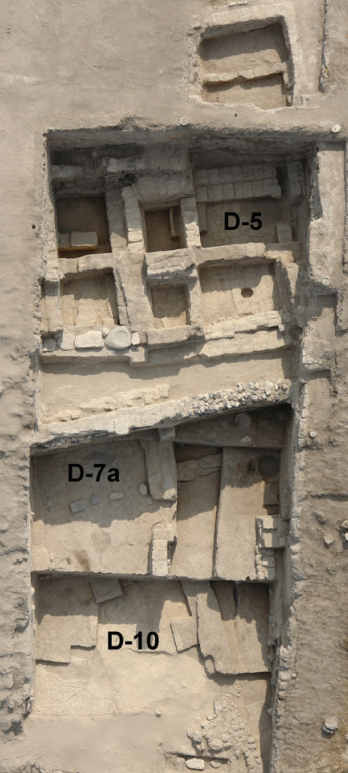

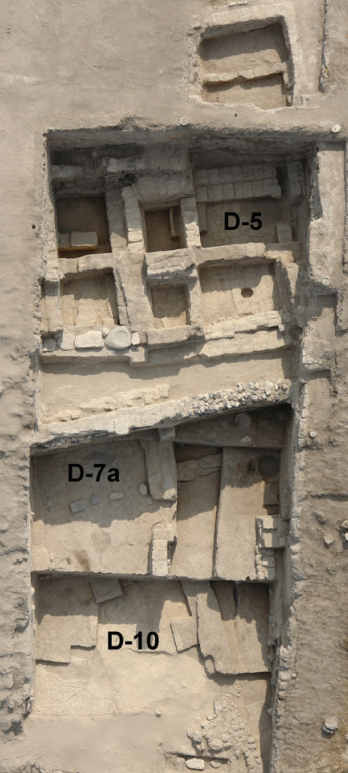

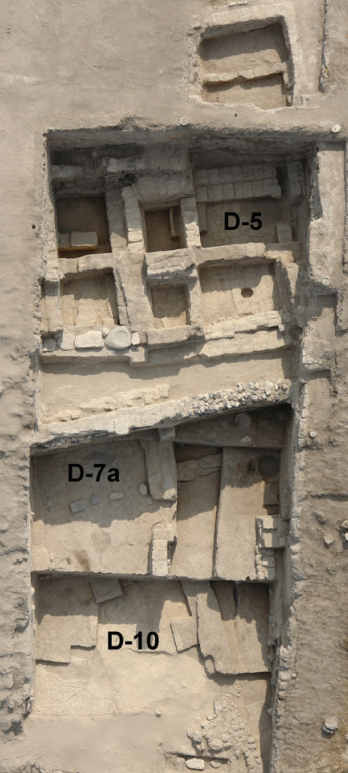

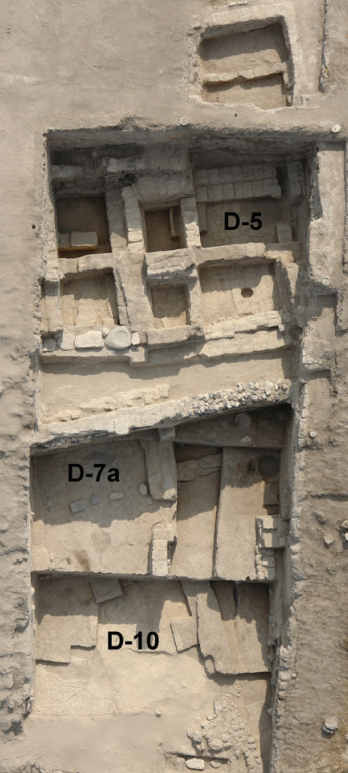

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.22

Plan of Stratum D-5 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.22

Figure 15.22

Plan of Stratum D-5

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.23

Plan of Stratum D-4b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.23

Figure 15.23

Plan of Stratum D-4b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.24

Plan of Stratum D-4a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.24

Figure 15.24

Plan of Stratum D-4a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.25a

Iron IB remains in Areas D and C from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.25a

Figure 15.25a

Schematic plan of Iron IB remains in Areas D and C, showing possible correlation: Strata D-5 and C-3b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.25b

Iron IB remains in Areas D and C from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.25b

Figure 15.25b

Schematic plan of Iron IB remains in Areas D and C, showing possible correlation: Strata D-4b and C-3a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.26

Plan of Stratum D-3, lower pits from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.26

Figure 15.26

Plan of Stratum D-3, lower pits

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.27

Plan of Stratum D-3, upper pits from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.27

Figure 15.27

Plan of Stratum D-3, upper pits

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.28

Plan of Stratum D-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.28

Figure 15.28

Plan of Stratum D-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.29

Plan of Stratum D-1c from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.29

Figure 15.29

Plan of Stratum D-1c

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.30

Plan of Stratum D-1b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.30

Figure 15.30

Plan of Stratum D-1b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.31

Plan of Stratum D-1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.31

Figure 15.31

Plan of Stratum D-1a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- Fig. 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.2

Schematic section of Area D from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2

Schematic section of Area D

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.3

Plan of Stratum D-11b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.3

Figure 15.3

Plan of Stratum D-11b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.4

Plan of Stratum D-11a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.4

Figure 15.4

Plan of Stratum D-11a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.5

Plan of Stratum D-10 constructional fills from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.5

Figure 15.5

Plan of Stratum D-10 constructional fills

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.6

Plan of Stratum D-10 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.6

Figure 15.6

Plan of Stratum D-10

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.7

Plan of Stratum D-9b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.7

Figure 15.7

Plan of Stratum D-9b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.8

Plan of Stratum D-9a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.8

Figure 15.8

Plan of Stratum D-9a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.9

Plan of Stratum D-8 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.9

Figure 15.9

Plan of Stratum D-8

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.10

Plan of Stratum D-8' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.10

Figure 15.10

Plan of Stratum D-8'

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.11

Plan of post Stratum D-8 fills from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.11

Figure 15.11

Plan of post Stratum D-8 fills

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.12

Plan of Stratum D-7b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.12

Figure 15.12

Plan of Stratum D-7b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.13

Plan of Stratum D-7a (encircled numbers denote foundation deposits as listed in the text) from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.13

Figure 15.13

Plan of Stratum D-7a (encircled numbers denote foundation deposits as listed in the text)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.14

Plan of Stratum D-7a' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.14

Figure 15.14

Plan of Stratum D-7a'

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.15

Plan of Stratum D-6b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.15

Figure 15.15

Plan of Stratum D-6b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.16

Plan of Stratum D-6a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.16

Figure 15.16

Plan of Stratum D-6a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.22

Plan of Stratum D-5 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.22

Figure 15.22

Plan of Stratum D-5

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.23

Plan of Stratum D-4b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.23

Figure 15.23

Plan of Stratum D-4b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.24

Plan of Stratum D-4a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.24

Figure 15.24

Plan of Stratum D-4a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.25a

Iron IB remains in Areas D and C from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.25a

Figure 15.25a

Schematic plan of Iron IB remains in Areas D and C, showing possible correlation: Strata D-5 and C-3b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.25b

Iron IB remains in Areas D and C from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.25b

Figure 15.25b

Schematic plan of Iron IB remains in Areas D and C, showing possible correlation: Strata D-4b and C-3a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.26

Plan of Stratum D-3, lower pits from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.26

Figure 15.26

Plan of Stratum D-3, lower pits

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.27

Plan of Stratum D-3, upper pits from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.27

Figure 15.27

Plan of Stratum D-3, upper pits

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.28

Plan of Stratum D-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.28

Figure 15.28

Plan of Stratum D-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.29

Plan of Stratum D-1c from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.29

Figure 15.29

Plan of Stratum D-1c

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.30

Plan of Stratum D-1b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.30

Figure 15.30

Plan of Stratum D-1b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 15.31

Plan of Stratum D-1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.31

Figure 15.31

Plan of Stratum D-1a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- Fig. 17.1

Schematic plan of Areas E and F; Iron IIA Stratum F-1 in black from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.1

Figure 17.1

Schematic plan of Areas E and F; Iron IIA Stratum F-1 in black

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.2a

Plan of Stratum E-3 (Square E/15) from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.2a

Figure 17.2a

Plan of Stratum E-3 (Square E/15)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.2b

Plan of Stratum E-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.2b

Figure 17.2b

Plan of Stratum E-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.3

Plan of Stratum E-1b in Squares D–F/13–16 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.3

Figure 17.3

Plan of Stratum E-1b in Squares D–F/13–16

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.4

Schematic plan of Stratum E-1a, marked with location of sub-plans from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.4

Figure 17.4

Schematic plan of Stratum E-1a, marked with location of sub-plans

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.5

General plan of Stratum E-1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.5

Figure 17.5

General plan of Stratum E-1a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- Fig. 17.1

Schematic plan of Areas E and F; Iron IIA Stratum F-1 in black from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.1

Figure 17.1

Schematic plan of Areas E and F; Iron IIA Stratum F-1 in black

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.2a

Plan of Stratum E-3 (Square E/15) from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.2a

Figure 17.2a

Plan of Stratum E-3 (Square E/15)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.2b

Plan of Stratum E-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.2b

Figure 17.2b

Plan of Stratum E-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.3

Plan of Stratum E-1b in Squares D–F/13–16 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.3

Figure 17.3

Plan of Stratum E-1b in Squares D–F/13–16

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.4

Schematic plan of Stratum E-1a, marked with location of sub-plans from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.4

Figure 17.4

Schematic plan of Stratum E-1a, marked with location of sub-plans

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 17.5

General plan of Stratum E-1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 17.5

Figure 17.5

General plan of Stratum E-1a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- Fig. 20.1

Plan of Stratum G-2b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

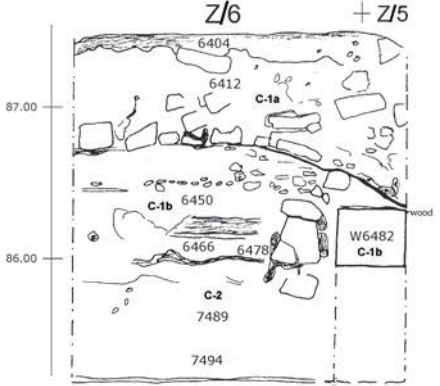

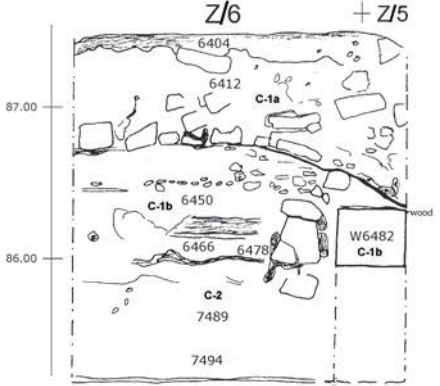

Figure 20.1

Figure 20.1

Plan of Stratum G-2b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.2a

Plan of Stratum G-2a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.2a

Figure 20.2a

Plan of Stratum G-2a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.2b

Plan of Stratum G-2a' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.2a

Figure 20.2a

Plan of Stratum G-2a'

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.3

Plan of wooden beams in the foundations of Stratum G-1 walls from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.3

Figure 20.3

Plan of wooden beams in the foundations of Stratum G-1 walls

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.4

Plan of Stratum G-1b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.4

Figure 20.4

Plan of Stratum G-1b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.5

Plan of Stratum G-1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.5

Figure 20.5

Plan of Stratum G-1a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- Fig. 20.1

Plan of Stratum G-2b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.1

Figure 20.1

Plan of Stratum G-2b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.2a

Plan of Stratum G-2a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.2a

Figure 20.2a

Plan of Stratum G-2a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.2b

Plan of Stratum G-2a' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.2a

Figure 20.2a

Plan of Stratum G-2a'

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.3

Plan of wooden beams in the foundations of Stratum G-1 walls from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.3

Figure 20.3

Plan of wooden beams in the foundations of Stratum G-1 walls

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.4

Plan of Stratum G-1b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.4

Figure 20.4

Plan of Stratum G-1b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Fig. 20.5

Plan of Stratum G-1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 20)

Figure 20.5

Figure 20.5

Plan of Stratum G-1a

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- from Chapter 2 - The Geology and Morphology of the Beth-Shean Valley and Tel Rehov ( Zilberman in Mazar et. al., 2020 v. 1)

- If you don't want to spend time reading, go through the Figures - they tell much of the story

- Figure 2.1 - Digital Terrain Map

showing locations and faults from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.1

The escarpment of the Western Marginal Fault of the Dead Sea Rift (dashed line). This escarpment forms the morphological and tectonic border between the Beth-Shean Valley and the Central Jordan Valley.

(DTM map by J.K.Hall, 1994)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.5 - Drawing of geological and

morphological structure of the Beth-Shean Valley from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5

Schematic block diagram illustrating the geological and morphological structure of the Beth-Shean Valley. The drainage systems are delineated by dashed lines.

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.6 - Map of the main surface and

subsurface structural elements in the Beth-Shean area from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6

Schematic illustration of the main surface and subsurface structural elements in the Beth-Shean area

(after Shaliv,Mimran and Hatzor 1991; Gardosh and Bruner 1998; Zilberman et al. 2004; Meiler et al. 2008)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.7a - Air Photo showing surface scarps

(in black) and subsurface trace (in yellow) of the marginal fault along with (in red) traces of the west to east seismic lines GP-5037 (to the north) and GP-5036 (to the south)

Figure 2.7a

Figure 2.7a

The surface scarp system and subsurface trace of the underlying marginal fault of the DSR (dashed line), as detected in geophysical surveys by Gardosh and Bruner 1998 and Bruner, Zilberman and Amit 2002. The traces of seismic lines GP-5036 and GP-5037 are marked on the aerial photo.

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.7b - West to east seismic line

GP-5037 (the northern line)

Figure 2.7b

Figure 2.7b

The subsurface marginal fault as interpreted from seismic line GP-5037.

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.7c - West to east seismic line

GP-5036 (the southern line)

Figure 2.7c

Figure 2.7c

The subsurface marginal fault as interpreted from seismic line GP-5036.

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Explanation : The deep faults labeled as "Fault Zone" in the seismic sections (2.7 b and c) were used to help draw the location of the marginal fault (in yellow) on the Air photo (2.7a).

Tel Rehov Paleoseismic Trench - The location of the Tel Rehov Paleoseismic Trench is pointed to by a yellow arrow in the Air photo (2.7a). Its extent is shown as a white double arrow (labeled Trench TR-1) on GP-5036 (2.7c). This Earthquake Encyclopedia has a webpage for the Tel Rehov Trench. Clicking on the link to the left will open it's page in a new tab.

Figures 2.7 a-c all come from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.11 - Subsurface structure of Tel Rehov

interpreted from a N-S seismic line - from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 2.11

Figure 2.11

The subsurface structure of Tel Rehov as demonstrated by the N–S oriented seismic line 136.

- Velocity-Depth model of lower tufa sediments

- Velocity-Depth model of upper anthropogenic sediments

(Note the small hill under the higher mound) - Diffraction Stack illustrating the waves diffracted from the fault traces

- the interpreted faults under the mound - the fault between stations 40 and 60 [2nd fault from the right] underlies the step between the higher and lower mounds.

(from Zilberman et al. 2002:13; Fig. 4)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.12 - Seismic interpretation of the top

of the lower tufa layer along with subsurface faults - from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 2.12

Figure 2.12

A subsurface map of the tufa hill, which underlies the anthropogenic sediments of Tel Rehov. The faults are reconstructed from the seismic survey. The survey lines are marked in red.

(from Zilberman et al. 2002:16; Fig. 5)

Seismic Survey lines (not shown here) are in Fig. 2.10 of Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1:28)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.13 - Buried Fault Scarp (exposed in a trench)

which bounds the western part of the mound - from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 2.13

Figure 2.13

The west-facing scarp of the fault that bounds the western part of the Rehov mound uplifted block (view to the east, toward the mound). The fault was detected by seismic line 134 and was exposed in a trench. Notice the different colors of the displaced sediment (light brown) and the overlying, undisturbed younger sediments (dark brown)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 2.10 - Topography of

Tel, Excavation Areas, and location of seismic lines - from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Figure 2.10

Figure 2.10

Detailed topographic map of Tel Rehov. The seismic lines are marked on the map.

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

- BSV - Beth-Shean Valley

- CJV - Central Jordan Valley

- DSR - Dead Sea Rift

- DST - Dead Sea Transform

- WMF - Western Marginal Fault

The Beth-Shean Valley [BSV] is bounded by four fault systems (Fig. 2.6). Its eastern boundary is a morphotectonic escarpment 20-40 m high that marks the trace of the Western Marginal Fault (WMF) of the DSR [Dead Sea Rift] (Gardosh and Bruner 1998; Bruner et al. 2002: Zilberman et al. 2004; Meiler et al. 2008). The north-south-oriented escarpment of the marginal fault runs between Sede Trumot in the south and the Nahal Harod stream in the north.

The valley is bounded in the west and north-west by the Gilboa fault belt that runs along the foot of Mt. Gilboa (Hatzor 1991; Shaliv et al. 1991; Gardosh and Bruner 1998; Meiler et al. 2008), which is the northeastern elevated part of the Shekhem Syncline. The southwestern tilted block of the Gilboa is bounded in the northeast by a belt of normal faults that forms a series of northeastward-descending blocks (Hatzor 1991; Gardosh and Bruner 1998).

The northern boundary of the BSV is the WNW (295°)—ESE(115°)-oriented Harod Graben fault system that separates between the southwestward-tilted blocks of the Sheluhat Zev'aim block in the north and Mt. Gilboa in the south (Meiler at al. 2008). The Sheluhat Zeva'im Ridge is a southwest-tilted block, capped by the Pliocene Cover Basalt. It is the southernmost of a series of post-Cover Basalt tilted blocks that dictate the present relief of the eastern Lower Galilee.

The north—west-oriented buried Mehola fault and the younger, subparallel Bardala fault, form the southern border of the BSV. They down-fault the northeastern part of the Faria anticline, which is buried under the Neogene sequence of the valley (Shaliv et al. 1991; Gardosh and Bruner 1998; Meiler et al. 2008) (Fig. 2.6). The Faria anticline is part of the Syrian Arc Fold belt. It is crossed by a north-west oriented normal fault system with a vertical displacement of several hundred meters. This system is part of a north-west-oriented fault system detected in the subsurface of the BSV by Meiler et al. (2008). The most prominent feature of this system is the "Arched Fault" that splits from the WMF near Tel Rehov and crosses the BSV to the northwest, where it appears to merge with the fault that runs along the northeast-facing mountain front of Mt. Gilboa.

From the above data, it appears that the Beth-Shean Valley is a structural block bounded between the elevated (about 1200 m) Gilboa block in the west and the subsided (about 2800 m; Meiler et al. 2008) DSR in the east.

The WMF of the DSR forms a prominent morphological escarpment 20-40 m high that separates the BSV [Beth-Shean Valley] from the CJV [Central Jordan Valley]. This escarpment is underlain by a system of deep-seated fault belts several hundred meters wide, encountered in several seismic reflection lines (Gardosh and Bruner 1998; Bruner et al. 2002; Meiler et al. 2008) (Figs. 2.5-2.7). The faults are inclined eastward towards the deep Kinnarot-CJV basin (Meiler et al. 2008) that is bounded in the east by the DST [Dead Sea Transform].

The escarpment formed by the vertical displacement along the fault is built of a tufa sequence that also underlies the surface of the BSV, as well as the western part of the CJV, thus reflecting a post-tufa deposition (post 20 ka) vertical offset of 20-40 m.

The southern escarpment (termed here the "Rehov Fault") extends from Sde Trumot in the south to Tel Rehov in the north (Figs. 2.5, 2.7a). It is a 15-20 m-high arched escarpment, which separates a high tufa plateau in the west from a flat surface covered by soil in the east. The northern escarpment (termed here the "Beth-Shean Fault") starts north of Tel Rehov and extends northward to the CJV (Fig. 2.5). The morphological expression of this fault can be traced northward to Kibbutz 'En Hanatziv, where it forms a clear step. Several springs are located along the trace of the fault: 'En Neshev, which is located some 600 m north of Tel Rehov, and 'En Naftali and 'En Yehuda, which are located in Kibbutz 'En Hanatziv. North of 'En Hanatziv, the steps of the fault merge with the 40 m-high escarpment that runs northward towards Beth-Shean (Figs. 2.1, 2.5, 2.7a).

North of Beth-Shean, the escarpment splits into two branches: one continues northward towards the Sea of Galilee and the second runs to the northwest towards Tel Beth-Shean and seems to merge with the north-south-oriented fault system that separates between the tilted blocks of Sheluhat Zev'aim and the CJV [Central Jordan Valley].

A deep seismic line, 1800 m long, and a short (500 m), shallow high-resolution seismic reflection line, which were shot across the escarpment of the marginal fault some 300 m north of Tel Rehov (Bruner et al. 2002) detected a fault belt some 400 m wide (Fig. 2.7c). The main stem of the marginal fault exhibits a dip of 70° eastward, while a low-angle (30-40°) array of listric faults splits from the main fault to the west, forming a fault belt. All these faults seem to displace the surface and some of them are expressed as N—NW-oriented low steps or undulations in the cultivated area.

- from Zilberman in Mazar and Panitz-Cohen ed.s (2020 v. 1:25-26)

- This Earthquake Encyclopedia has a webpage for the Tel Rehov Trench. Clicking on the link to the left will open it's page in a new tab.

The trenched fault is the western branch of a low-angle normal fault belt, which is part of the WMF belt of the DSR. It was detected in the seismic line that was shot across the escarpment. It is visible up to a depth of 0.5 sec (two-way travel time), near the top of the Miocene Hordos Formation (Fig. 2.7b, c).

The trench exposed a fault escarpment about 3.0 m high (Figs. 2.8-2.9), built of tufa. The age of the tufa in the lower block is 64±5 ka, and in the upper block 32 ±2.5 ka (determined by the U/Th method). The time period between the deposition of the upper part of the tufa and the colluvial sediments exposed in the trench (i.e., almost 30 ky) is not represented in the sequence. This sedimentary hiatus is related to the erosion of the uplifted block which is located on the upper part of the tectonic step.

The lower block is overlain by two colluvial units built of silty gray-brown sediments, consisting mainly of reworked soils and tufa fragments, with scattered pieces of pottery. The deposition of each of these units was triggered by an earthquake associated with a vertical displacement of about 1.5 m that occurred sometime in the 7th and 8th centuries BCE. These two co-seismic displacements correspond to earthquakes with a magnitude of M=6.5-6.7, which are usually accompanied by surface rupture 20-30 km long (Wells and Coppersmith 1994). However, only one strong earthquake from this period is mentioned in historic catalogues (Ben Menahem 1991).

This earthquake, which is also mentioned in the book of Amos, occurred in 759 BCE and caused great damage in the Galilee, Samaria and Judea. The magnitude of this earthquake has been estimated from historical records as ML=7.3 and it is assumed that its epicenter was located some 140 km north of Jerusalem, probably near Hazor (Ben Menahem 1991).

- [JW: The Amos Quakes appear to have been at least two large earthquakes rather than one. This was discovered by Kagan et. al. (2011:Appendix C) who observed two seismites at three locations in the Dead Sea separated by up to a few decades of deposition.

- Two closely timed earthquakes were also observed in Deir 'Alla

- Destruction observed at Hazor was not extensive and may have occurred to abandoned or weakened structures. There is no good reason to place the epicenter(s) that far north

- Ben-Menahem (1991) was unaware that there were two earthquakes when he composed his catalog and surmised that only a very large magnitude earthquake could explain all the archeoseismic evidence in the north and south of Israel.

- The archeoseismic evidence in the north and south of Israel is explained by two (or more) earthquakes

- Historical records do not allow us to assign a Magnitude as the description of the earthquake in the older sources is too brief. No locations for seismic destruction is mentioned in Amos. Pseudo-Zechariah mentioned that the earthquake was felt in Jerusalem and the passage suggests that the shaking was intense.

- Ben-Menahem (1991) also assumed that the chronological synchronisms of Josephus, writing about one of the Amos Quakes ~850 years later and not citing a source, were accurate. This was not a good assumption as Josephus has a tendency to embellish his narratives. As a result, while 759 BCE is a possible date for one of the Amos earthquakes, the best the historical sources can do is to constrain the dates to between 766/765 and 751 BCE.

- See more in the entry for the Amos Quakes

- If you need to consult an earthquake catalog, consult this one, Ambraseys (2009), Guidoboni et. al. (1994), Guidoboni and Comastri (2005), or Zohar (2019). Other catalogs contain a number of errors.]

[JW: That earthquake struck in January 749 CE - See the Sabbatical Year Quakes entry.]

The paleoseismic analyses of the tectonic activity along the WMF illustrates only part of the tectonic activity in this region, which is induced by the left lateral movement along the DST that runs in this area along the eastern margin of the DSR. The most prominent feature related to this activity is the escarpment that separates the BSV from the CJV. This fault escarpment is underlain by a deep-seated, east-dipping fault belt dominated by vertical displacement, which accommodates the subsidence of the Kinnarot-CJV basin (Meiler et al. 2008).

The deformation of the landscape by the young tectonic activity is manifested by the configuration of the stream network in the BSV and the CJV. In the BSV, the escarpment forms a barrier to the east-flowing streams that drain Mt. Gilboa and then shift northward towards Nahal Harod (Fig. 2.5). This situation is attributed to a westward tilting of the Beth-Shean block (the Beth-Shean Valley) by the tectonic phase that established the present escarpment. This change in the flow direction post-dates the tufa sequence that was deposited in eastward-flowing streams.

The situation on the eastern, down-faulted block (the Central Jordan Valley) is much more complicated; the present eastward gradient of this area is well manifested by the flow direction of the main springs and Nahal Harod. However, the geometry of the abandoned stream network indicates that a previous westward-flowing channel system drained this area. Therefore, it seems that the post-tufa tectonic activity along the marginal fault also caused a westward tilting of the eastern, down-faulted block.

The establishment of this drainage system is probably young, not older than the mid-Holocene. This conclusion is based on observations made by Neev (1976) and Koucky and Smith (1986) that in the early Holocene, the CJV was still covered by swamps and ponds. The development of the present drainage systems was induced by the establishment of the Jordan River and desiccation of the ponds and swamps that covered the CJV.

It is not clear when the westward-descending terrain of the western part of the CJV was inverted to the present eastward gradient. However, if we accept the observations of Neev (1976), we must assume that post-Chalcolithic period tectonic activity was responsible for this gradient inversion, which was also associated with the first incision of the Jordan River in the CJV. The preservation of this channel system in spite of a thousand years of intensive cultivation, suggests that the inversion of the drainage direction occurred in historic times.

Tel Rehov is located 4 km south of Beth-Shean on the tectonic and morphological boundary between the Beth-Shean and the Central Jordan Valleys (Figs. 2.1, 2.5, 2.7a). The tell is separated from the tufa plateau of Moshav Rehov in the south by a narrow valley occupied today by an artificial drainage canal and from the northern tufa plateau by a valley, probably a route of an ancient spring, occupied today by dense vegetation indicating a high ground-water level. To the east, the tell rises above a flat east-descending surface underlain by tufa near the marginal fault and by lacustrine sediments of the Lisan Formation further eastward (Rozenbaum 2009).

The mound of Tel Rehov is located in a tectonic depression that developed between two segments of the Western Marginal Fault of the DSR (Figs. 2.5-2.6): the Rehov Fault in the south and the Beth-Shean Fault in the north. The WMF that runs east of the mound is expressed in this area as a fault array several hundred meters wide, which forms a series of low morphologic steps descending to the east, associated with east-flowing springs that create narrow gorges in the uplifted blocks.

The mound of Tel Rehov is composed of two levels separated by a steep step (Fig. 2.10). The height of the southern mound is 20-25 m above its surroundings, whereas the northern low mound is only 8-10 m high. The base of the step that separates the two parts of the tell is drained eastward by a channel, which, together with the base of the escarpment, forms a morphologic lineament. A tufa bank, which is exposed at the western foot of the mound, indicates that the first settlement was built on a small hill built of tufa sequence.

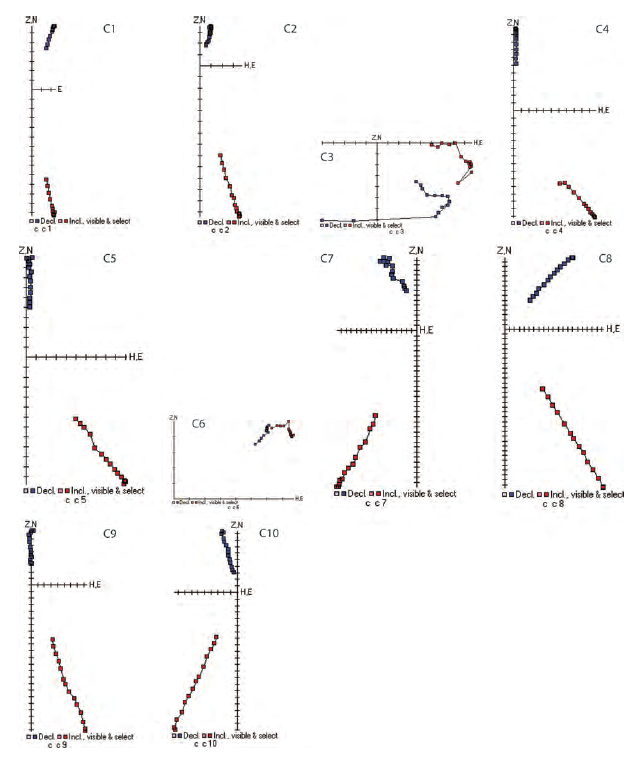

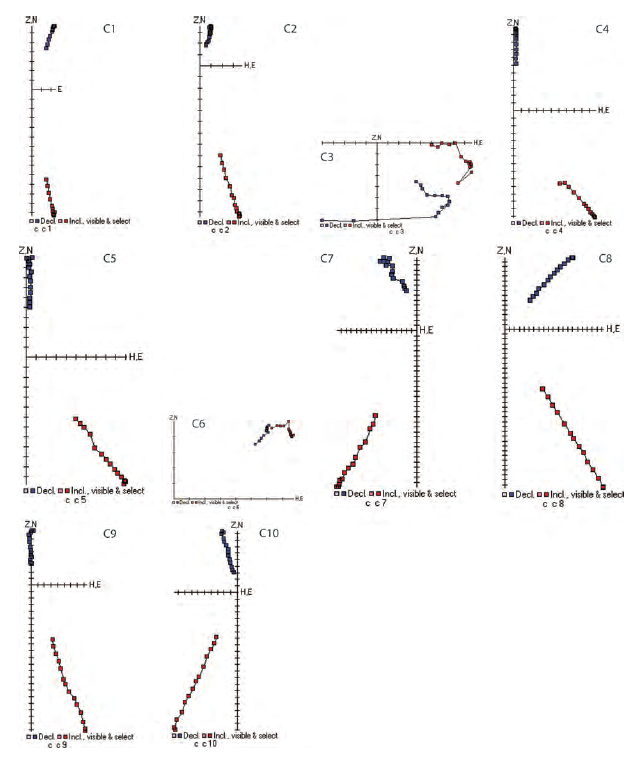

The subsurface relief of Tel Rehov is hidden at present under the anthropogenic sediments of the mound. In order to evaluate the relief of the underlying terrain and to examine the relations between its morphology and the fault system in this area, several high resolution seismic lines were shot by the GII across the mound (Fig. 2.10), applying a combination of reflection and refraction wave methods (for details, see Zilberman et al. 2002). Mapping of seismic reflectors and velocity estimation along them based on refraction waves is carried out in three stages (Fig. 2.11):

- refraction stack

- inversion

- tomography

A three-dimensonal map of the contact plane between the two seismic units identified in the area of Tel Rehov (Fig. 2.12) indicates that human settlement on the tell began on an apparently uplifted tectonic block approximately 10 meters above its surroundings. The western border of the block is steep and relatively straight, whereas its eastern part slopes moderately eastward. In the northeast, there is a subsurface step along which the seismic contact plane drops about 6.0 m to the north. This step coincides roughly with the northern slope of the low mound. The morphological step that separates the two parts of the tell is also manifested, albeit indistinctly, in the buried relief below the anthropogenic section. The map indicates that beneath the morphologic step there is a low tectonic step, 3.0-4.0 m high, which is underlain by a fault.

A steep slope also characterizes the southern margin of the uplifted block, were the seismic contact surface between the anthropogenic section and the tufa is some 15-20 m lower than the tufa sequence exposed in the slope of the Rehov tufa plateau, just south of the tell. This suggests that a NW—SE trending fault separates the tufa plateau in the south from the tectonic depression of Tel Rehov in the north. This is evidently the tip of a fault that runs southward and separates the elevated Rehov tufa plateau from the lower eastern block on which Kibbutz Sde Eliyyahu is located.

Faults were also identified along the northern (seismic lines 133, 137), southern (seismic lines 135, 136) and western (seismic line 134) margins of the tell. The west-facing escarpment of the western fault was exposed in an E—W-oriented deep trench excavated across its subsurface trace (Fig. 2.13). On the other hand, no fault was identified along the moderate eastern margins of the uplifted block (seismic lines 135, 137).

Therefore, the overall view of Tel Rehov is of a tectonic block which is tilted to the east and bounded on three sides (west, north and south) by faults or sets of faults. The seismic sections also indicate the presence of several faults that cross the uplifted block of the tell.

- from Chapter 3 - Introduction to the Site and the Excavations ( Mazar in Mazar et. al., 2020 v. 1:42-51)

- Photo 3.7 - Aerial Photo

of Tel Rehov showing eroded ravine on the eastern slope from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Photo 3.7

Photo 3.7

Tel Rehov, looking northwest towards Beth-Shean and the Harod Valley. Note the ravine between the upper and lower mound and the damaged area on the eastern part of the upper mound; note also the hump on the western part of the upper mound, where the Early Bronze fortification and the Islamic village are located

(Photo: Albatross; 2003)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Photo 3.8 - Another Aerial Photo

of Tel Rehov showing eroded ravine on the eastern slope from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Photo 3.8

Photo 3.8

Tel Rehov, looking west towards the Gilboa ridge. Note the ravine between the upper and lower mound and the damaged area on the eastern part of the upper mound. The green area on the far right marks the spring closest to the mound

(Photo: Albatross; 2003)

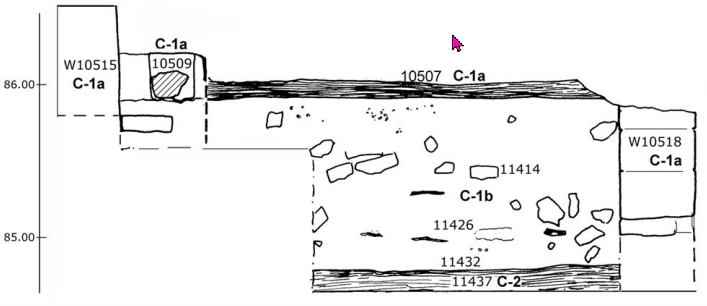

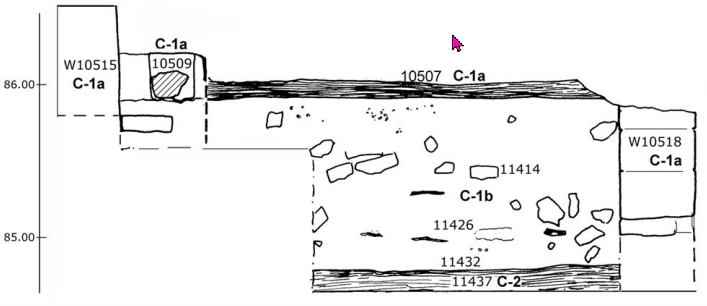

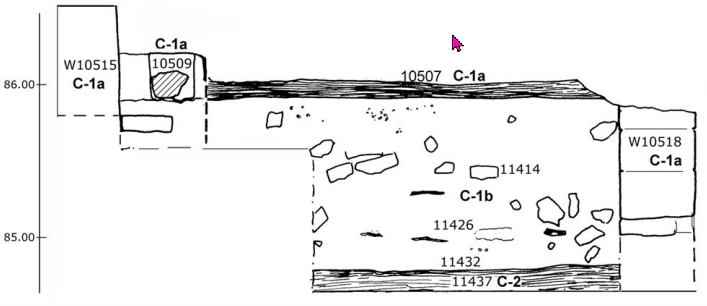

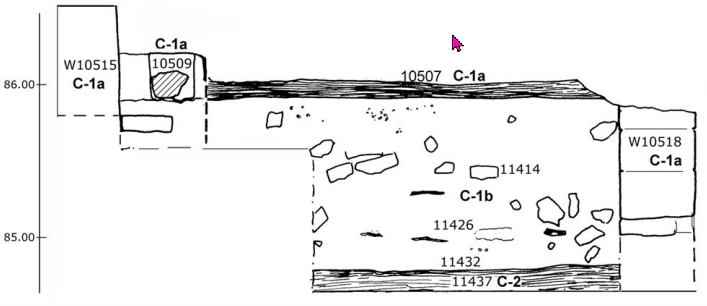

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Figure 3.4 - Plan View

and Section Views

Photo 3.4

Photo 3.4

Schematic sections through the tell, showing the present topography. Location map of sections and sections a–a to d–d. Levels in m below sea level (these differ from the levels used in the excavation report; see text)

(prepared by Sveta Matskevich)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)through the Tel from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.5)

Photo 3.4

Photo 3.4

Schematic sections through the tell, showing the present topography. Location map of sections and sections a–a to d–d. Levels in m below sea level (these differ from the levels used in the excavation report; see text)

(prepared by Sveta Matskevich)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.5)

... THE MOUND: LOCATION, MORPHOLOGY AND SITE-FORMATION PROCESSES

... The morphology of the mound as seen today is probably the result of site-formation processes which occurred during its history due to both tectonic and human activities. A geophysical survey of the mound enabled reconstruction of the natural topography and the depth of the anthropogenic deposits (Chapter 2; Zilberman et al. 2002). The results indicate the existence of an elongated ridge stretching along the western side of the mound from its top until the northwestern corner of the lower mound, with its top level at ca. 140–143 m below sea level (corresponding to ca. 74–77 m in terms of the expedition heights; see explanation below). Thus, the uppermost point of the upper mound in the south should be ca. 24 m above bed-rock, and the topsoil in Area C (in the northwestern part of the lower mound in the north) would be ca. 12 m above the tufa bedrock in that part of the mound (Chapter 2, Figs. 2.10–2.11). A small hill, evidently of tectonic origin, was defined below the top of the upper mound; perhaps this would become the core of the fortified Early Bronze Age settlement defined in Area H (Chapter 5). A series of geological faults were mapped along the survey lines, as follows:

- along the northern edge of the lower mound

- in the south of the upper mound

- three faults in the area of the mound itself, the largest one at the eastern side of the lower mound, including the ravine between the upper and lower mounds south of Area E (Chapter 2, Figs. 2.10,2.12); see Fig. 3.4 for schematic sections of the present topography of the tell.

The lower mound, ca. 315 m along the east–west axis and 135 m along the north–south axis, rises to 8–9 m above the plain on the west and north, while the upper mound (275 m on the east–west axis and 237 m on the north–south axis) rises to ca. 20 m above the plain on the west and ca. 25 m above the ravine that traverses the tell from west to east at the juncture between the upper and lower mounds. The surface of both the upper and lower mounds slopes down to the east; thus, the triangulation point on the western end of the upper mound (-116.26 m, our 100 m datum line) is 15 m higher than the topsoil at the eastern edge of Area A2, 125m to the east, where Iron IIB remains were found just below topsoil. The western end of the lower city at the top of the mound’s slopes in Area C is ca. 16 m higher than the eastern end of that part of the city, near Area E, ca. 300 m away (Fig. 3.4).

The downslope of the topsoil surface to the east and the ravine between the lower and upper mounds may have been created by tectonic activity during historical times. This suggestion is supported by the fact that the mound is located between two segments of the Rehov–Beth-Shean geological fault, and that a minor fault was detected between the upper and lower mounds, as noted above. These subsidiary faults of the Dead Sea Rift are still active and could have affected the shape of the mound during historical times (Chapter 2). Evidence of the slope down from west to east was also detected inside the excavation areas and comprises a prominent site-formation feature. For example, in AreaD, Late Bronze and Iron I layers and floor surfaces were found tilted from west to east, although they are on the western slope of the mound, which would infer an opposite tilt direction. In Area C, elevations of floors in the eastern side of the area are ca. 0.6–1 m lower than floors of the same stratum in the western side of the area, ca. 20 m away; such differences may indicate that by the- 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the slope down from west to east already existed.

Evidence for recent tectonic movements was also found at the bottom of the step-trench in Area D on the western slope of the lower mound, in the form of a 1.3 m-high step in the tufa bedrock in Square K/5, which was interpreted by Zilberman as the outcome of young tectonic activity (see Chapter 2, Figs. 2.8-2.9). This down-faulted block (level 74.70 m) was not reached in the deep backhoe trench that was dug in the field west of the mound (base level of 73.85 m), implying that this is possibly only one step in a graduated fault zone, which resulted in a considerable subsidence of the area west of the mound prior to the accumulation of thick colluvial sediments to its west (see further below). This fault was initially detected in the geo-seismic study of the mound (Zilberman et al. 2002). The dating of the faulting activity is unclear; however, it could, at least in part, be later than the earliest occupation of the lower mound in the 15th century BCE.

The lowest part of the western slope of the mound was buried under layers of colluvium accumulated over the last 3000 years. This became evident in Area D, where Stratum D-11, the lowest Late Bronze Age occupation layer, was exposed 2.15 m lower than the current level of the plain to the west of the mound (Chapter 15; Fig. 15.2). This indicates a substantial rise of the field level in historical times, as well as significant changes in the topography and visible prominence of the mound, at least on the western side. A backhoe trench dug into the field ca. 8 m to the west of the edge of the mound opposite Area D, revealed an accumulation of brown colluvial soils at least 4.3 m deep (as much as the backhoe could reach); this layer contained only Roman/Byzantine sherds, probably eroded from Khirbet Farwana, ca. 0.7 km northwest of the mound, the location of the Roman-Byzantine town Rohob. The accumulation of such thick deposits during the last 3000 years (or less) is probably the result of massive erosion from the Gilboa ridge, located ca. 3 km west of the mound, possibly through ancient channels not clearly visible in the present topography of the valley, but that can be detected through geophysical inquiries (Zilberman et al. 2002; Zilberman, Amit and Bruner 2004; Chapter 2, this volume). Similar phenomena were observed near other mounds in the Southern Levant, e.g., Lachish and Megiddo (Rosen 2006, with previous literature).

Erosion along the slopes of the mound is another site-formation feature. In Area D, all eleven strata revealed in the step-trench were found cut along their western margins, so that the western portions of all the structures were missing. The extent of the erosion is unknown, but it may be assumed that it caused the elimination of ca. 1-2 m of each stratum. No fortifications were found along the slope in Area D, but it seems that an entire fortification system could not just disappear due to erosion and we thus concluded that such fortifications did not exist during the entire LB IB-Iron Age IIA occupation sequence represented in Area D (Chapter 15).

On the north and south, the mound is bounded by east-west brooks. An unnamed spring is located at the bottom of the northern slope of the lower mound; today, a substantial part of this area is covered by dense reeds and vegetation typical of an area adjoining a water source (see Photo 3.3, top). Three additional springs ('En Neshev, 'En Merljav and 'En Rehov) are found 350-450 m to the north and east of the mound; these must have been the main water sources of the ancient city. Five additional springs are located at a distance of up to 2 km to the north and east; two of them are in the area of Kibbutz 'En Hanatziv, 1.5-2 km north of the mound (known today as 'En Zvi and 'En Yehudah, which are probably the springs marked as Ain Nusrah and Ain Nuseirah on the SWP map; see Fig. 3.1 and Chapter 1, Fig. 1.3).

The SWP map marks a "Roman Road" 500 m due west of the mound, just below or parallel to the modern Route 90, the main road through the Jordan Valley to Beth-Shean (Fig. 3.1; Photo 3.1, upper left). It may be assumed that a similar road was in use during the Bronze and Iron Ages, and that an east-west road led to Transjordan, as alluded to in Papyrus Anastasi I.

Gates to the lower city may have been located at the eastern end of the outlet of the ravine between the upper and lower mounds and, perhaps, also near the western join between the lower and upper mounds, where there is a topographic depression with a modern dirt road that ascends the mound from the west. A ramp visible on the northern slope of the lower mound could be evidence for an ancient road that climbed the slope to a possible entrance located between Areas C and E, although this may have been a modern feature (Photo 3.11).

Table 12.1

Table 12.1Correlation of local Area C and general tell strata

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.2)

Table 15.1

Table 15.1Stratigraphy and chronology in Area D, with correlation to Area C

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

Table 17.2

Table 17.2Correlation of the Iron Age stratigraphic sequence in Areas C, D, E, and F

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

Table 20.1

Table 20.1Correlation of strata – Areas G and C

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- from Finkelstein (2013:7)

Table 1

Table 1Dates of ceramic phases in the Levant and the transition between them according to recent radiocarbon results (based on a Bayesian model, 63 percent agreement between the model and the data)

Finkelstein (2013:7)

- from Amihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

- For reference in dealing with older publications

Stratigraphy of Tel Rehov

Stratigraphy of Tel RehovAmihai Mazar in Stern et. al. (2008)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

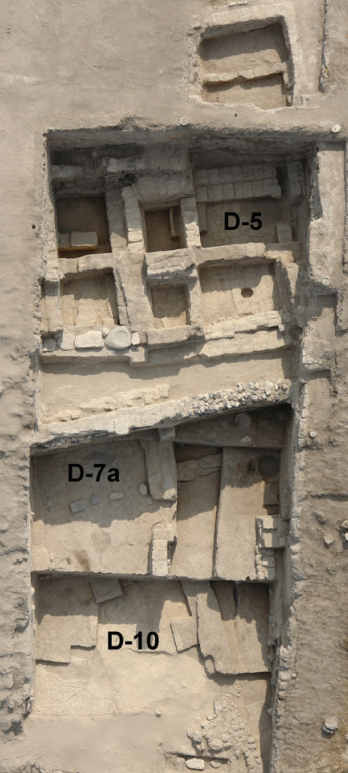

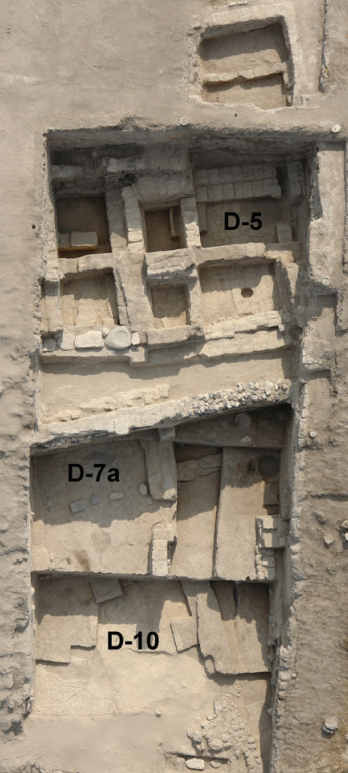

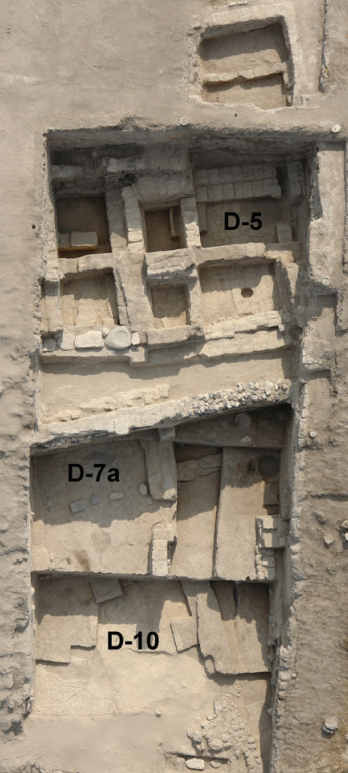

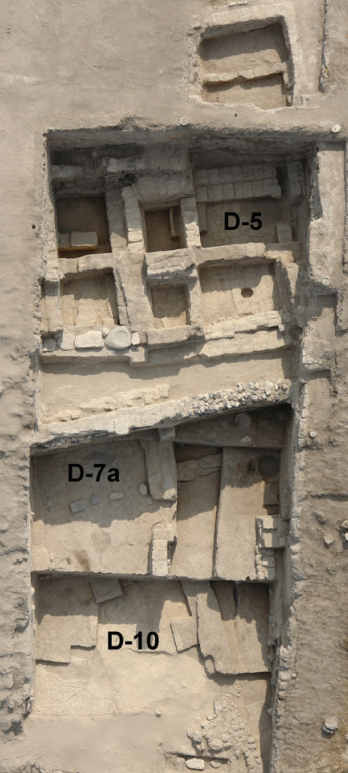

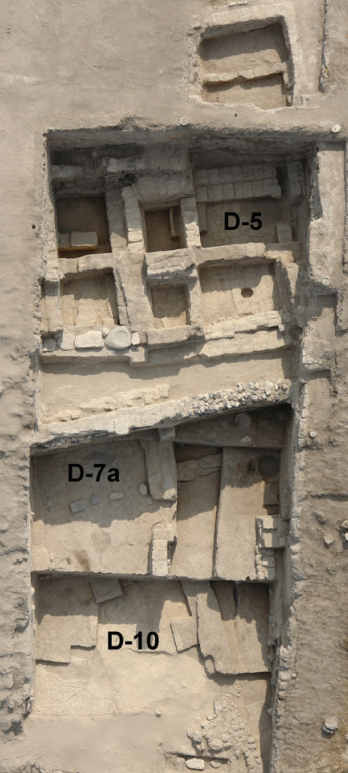

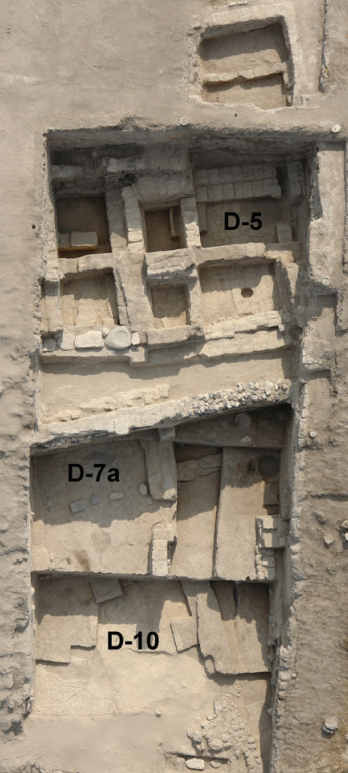

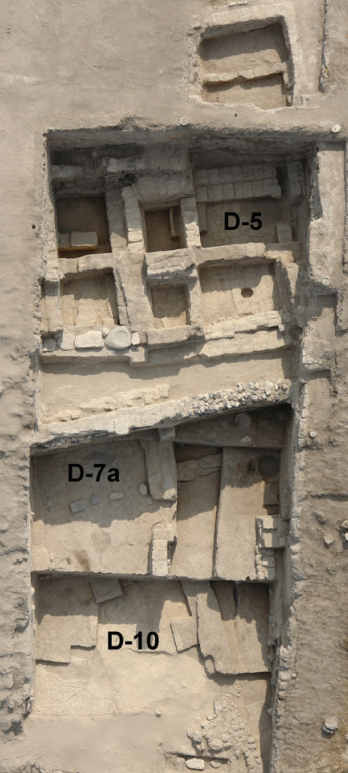

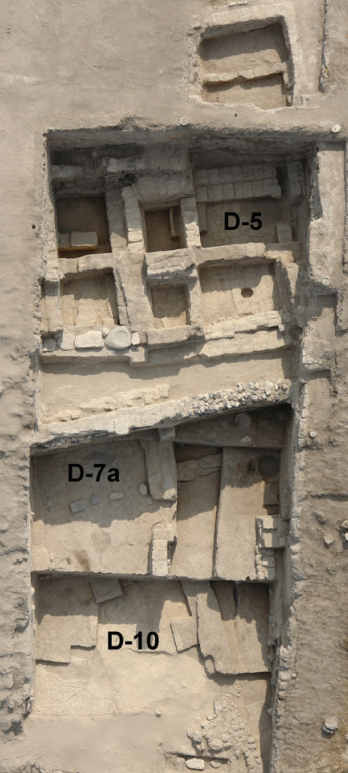

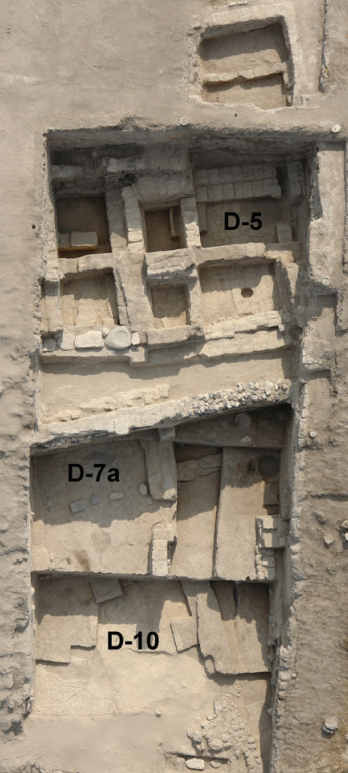

Although

Mazar in Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15:1) noted that continuous occupation was detected in Area D from Late Bronze I to Iron IIA,

a time span of some 600 years

and that no major destruction events were identified between the strata

, there are a number of descriptions

of potentially seismically induced structural damage in their report on Area D. It may be the case that in some parts of Mazar et. al. (2020)'s

Final Report, destruction is defined solely as destruction due to military conquest.

Rotem, Sumaka'i Fink, and Mazar in Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3 Ch.15:57) report that Iron IIA strata in Area D (D-2 and younger) were very damaged,

apparently due to erosion.

- Figure 15.5

Plan of Stratum D-10 constructional fills from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.5

Figure 15.5

Plan of Stratum D-10 constructional fills

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.6

Plan of Stratum D-10 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.6

Figure 15.6

Plan of Stratum D-10

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

Davidovich, Sumaka'i Fink, and Mazar in Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15:16-19) report brick debris related to collapse of Building DA in Stratum D-10 while noting that

it remains unclear whether a human or natural agent initiated the collapse of the building.Davidovich, Sumaka'i Fink, and Mazar in Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15:20) later noted that

There is no clear evidence for a sudden or violent destruction of this building, although very little of its interior was excavated. It is possible that the building went out of use due to deterioration, damage by earthquakes or other natural causes. It is also possible that the building was abandoned as part of socio-political changes in the city during the transition between the 14th and 13th centuries BCE.Stratum D-10 was dated to LB IIA in the 14th century BCE

- Figure 15.7

Plan of Stratum D-9b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.7

Figure 15.7

Plan of Stratum D-9b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.8

Plan of Stratum D-9a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.8

Figure 15.8

Plan of Stratum D-9a

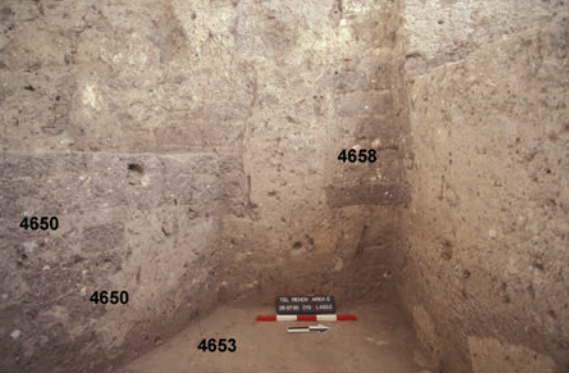

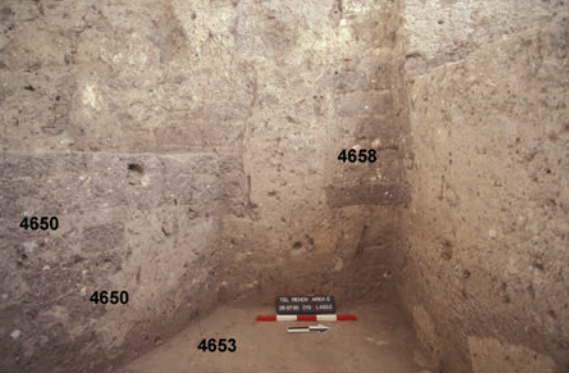

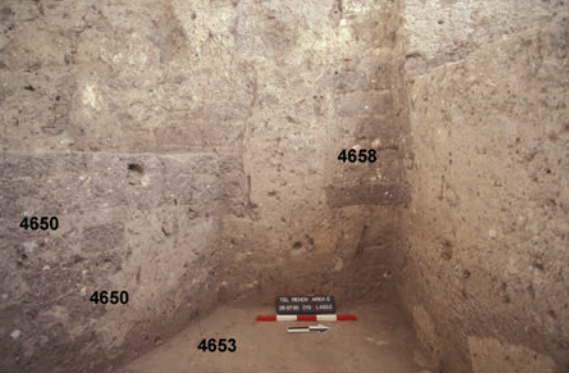

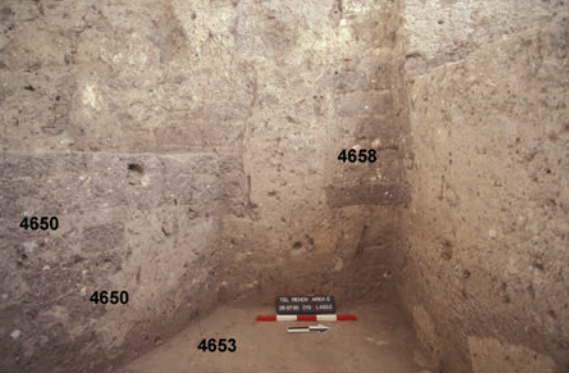

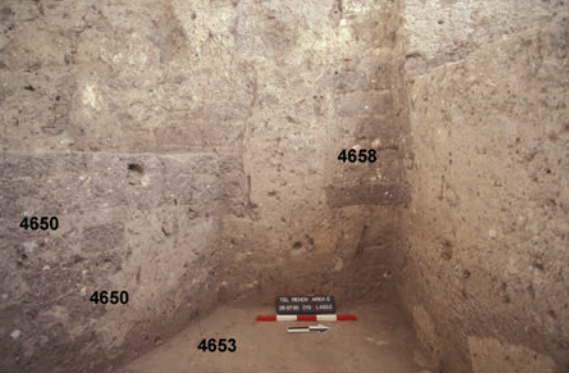

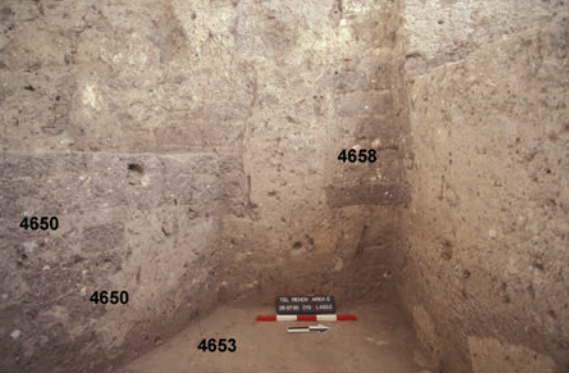

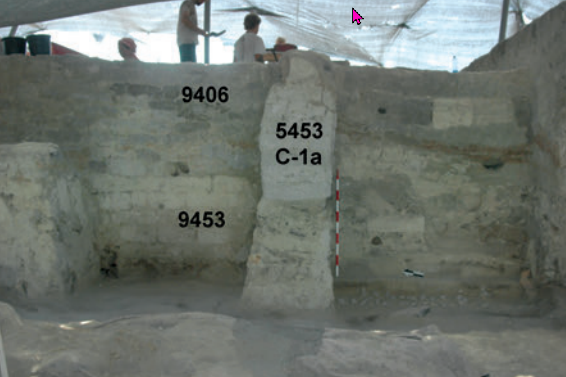

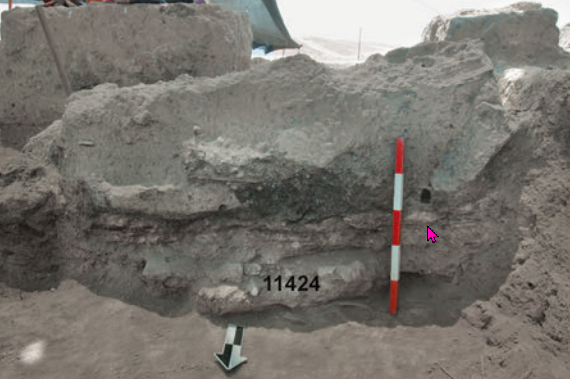

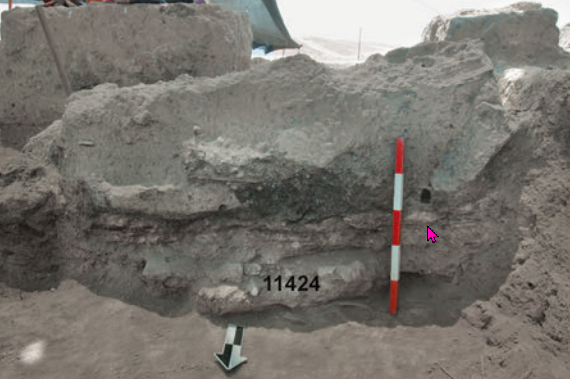

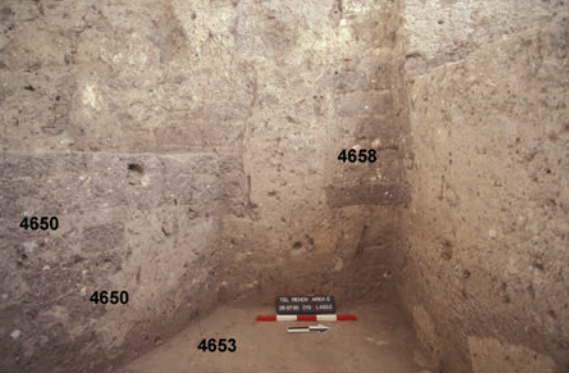

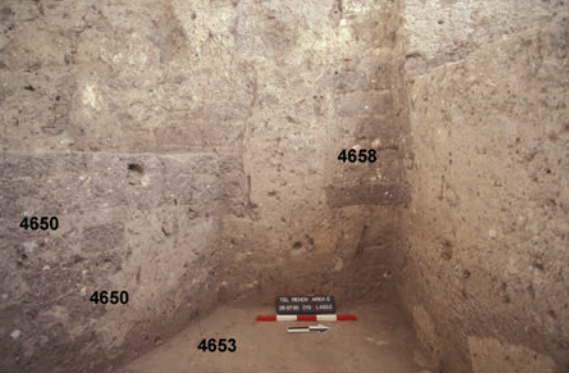

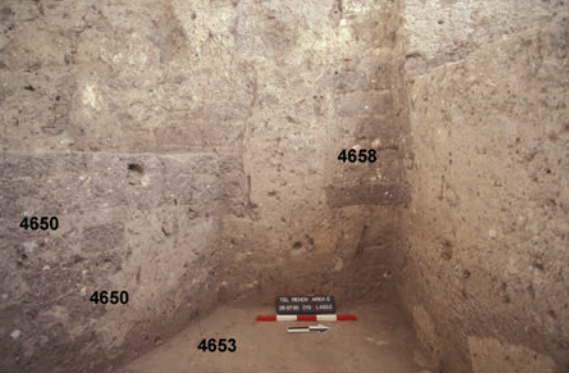

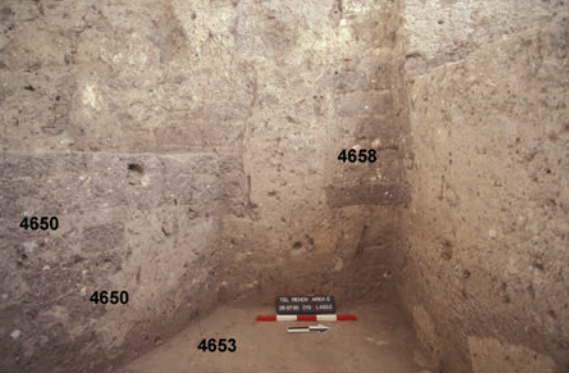

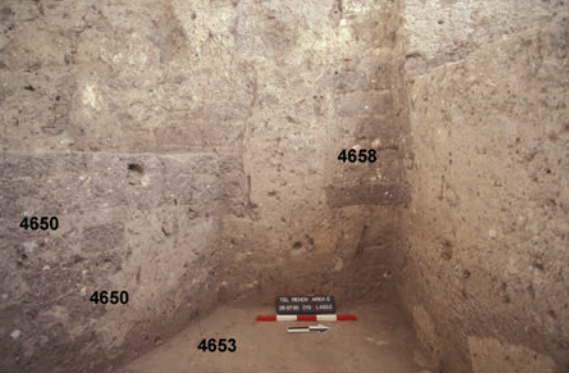

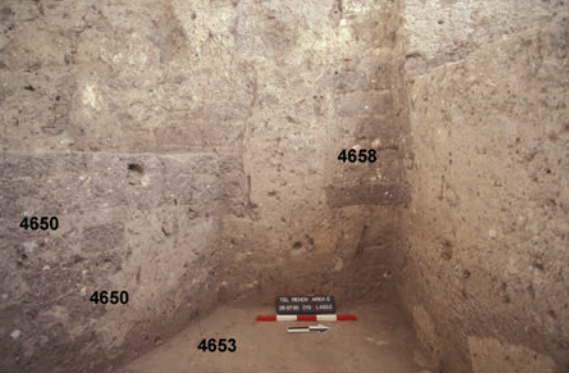

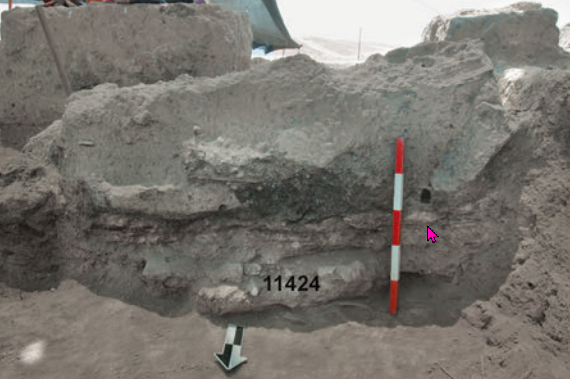

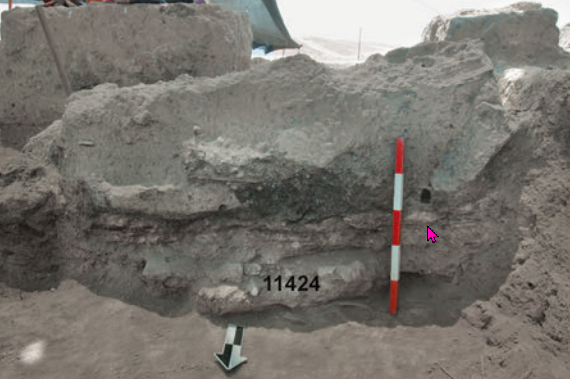

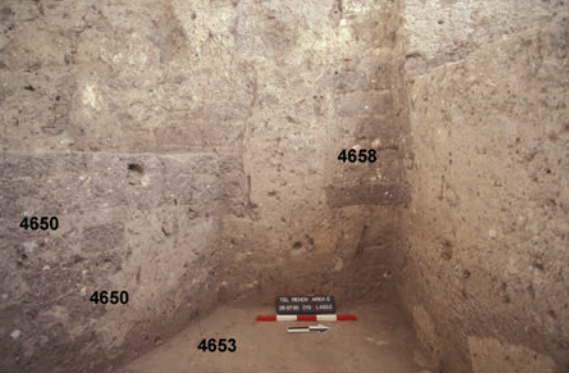

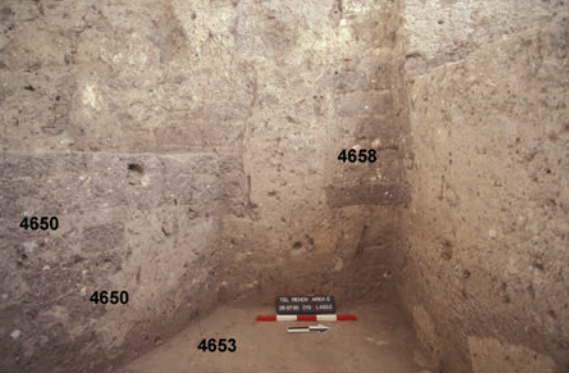

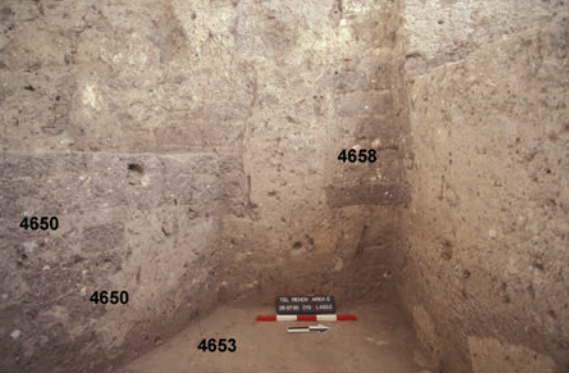

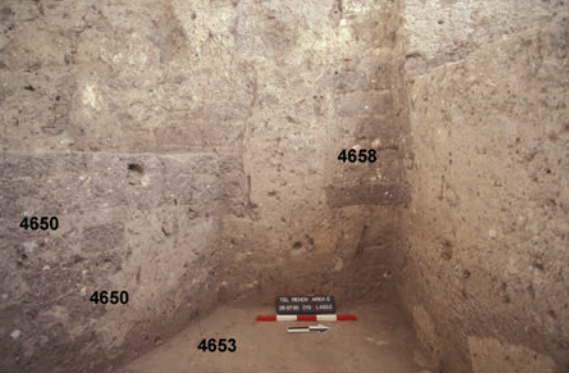

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Photo 15.28

Squares M–N/4–5 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Photo 15.28

Photo 15.28

Squares M–N/4–5, looking south at D-9a–b stone foundations (2010)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Photo 15.29

Squares M–N/4–5, from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Photo 15.29

Photo 15.29

Squares M–N/4–5, looking south; left: D-9a Wall 8932 and Post-holes 1912; right: D-9b stone foundations (2010)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Photo 15.30

Squares N/4–5 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Photo 15.30

Photo 15.30

Squares N/4–5, looking west; top: D-9b stone foundations; bottom: D-9a Wall 8932 and Post-holes 1912; right: D-9a Wall 1916 (2010)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Photo 15.31

Squares N/5 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Photo 15.31

Photo 15.31

Square N/5, looking south; bottom: D-9a Wall 1916; right and top: D-9b Walls 8943 and 9923; left: D-9a Post-holes 1912 (2010)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

Davidovich, Sumaka'i Fink, and Mazar in Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15:22-26) report that

two units, either rooms or courtyardsin D-9b Building DB

were delineated by three walls (8943, 9923, 1904) (Photos 15.28–15.31)while noting that Wall 9923

sloped considerably to the east, with a difference of up to 0.4 m in elevation of the lower level over its length.They noted the presence of

other tilted features in this areawhich

possibly resulted from young [er?] tectonic activity. They also noted that

the wall ended abruptly on the east, without a clear edge, and with a slight protrusion to the south, the nature of which remained unclear.

Davidovich, Sumaka'i Fink, and Mazar in Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15:22-26) noted that the foundations of oven 9924 near to Wall 9923

were slightly tilted to the east, in accordance with Floor 9925 and Wall 9923.

Strata D-9a and D-9b were dated to LB IIA/IIB in the late 14th-13th centuries BCE.

- Table 15.1

Stratigraphy and chronology in Area D, with correlation to Area C from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Table 15.1

Table 15.1

Stratigraphy and chronology in Area D, with correlation to Area C

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Table 15.2

Locus and basket numbers from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Table 15.2

Table 15.2

Locus and basket numbers

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.2

Schematic section of Area D from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2

Schematic section of Area D

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.10

Plan of Stratum D-8' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.10

Figure 15.10

Plan of Stratum D-8'

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- Plans: Figs. 15.10

The Stratum D-8 floor to the west of Wall 8932 was covered with a 0.3–0.4 m-thick layer of brick debris, containing compacted whitish brick fragments, which most probably originated from Wall 8932. In Square M/5, this debris layer was superimposed by a 0.01–0.02 m-thick pinkish clay layer (7938; Figs. 15.10, 15.17), which was covered by a thick (0.05–0.1 m) layer of dark gray ash. This layer sloped from west (80.40 m) to east (80.26 m); it extended into the northern section of the square, but faded away in its southern part, as well as in Square N/5 (9908; Fig. 15.10). On 7938 was a 0.15–0.2 m-thick accumulation, rich in sherds and animal bones, which may be explained as some kind of a localized ephemeral activity, post-dating Stratum D-8 and pre-dating Stratum D-7b; this phase was denoted D-8'. No evidence for this activity was found in Squares M–N/4.

Pottery from loci attributed to this layer is presented together with that of Stratum D-8 (Figs. 16.16–16.22), and is dated to LB IIB [13th century BCE].

- Table 15.1

Stratigraphy and chronology in Area D, with correlation to Area C from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Table 15.1

Table 15.1

Stratigraphy and chronology in Area D, with correlation to Area C

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Table 15.2

Locus and basket numbers from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Table 15.2

Table 15.2

Locus and basket numbers

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.2

Schematic section of Area D from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2

Schematic section of Area D

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.10

Plan of Stratum D-8' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.10

Figure 15.10

Plan of Stratum D-8'

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3)

- Plans: Figs. 15.10

Covering the brick debris and walls related to Stratum D-8, a 0.35–0.6 m-thick layered accumulation was found all over the excavated area (2826 in Square M/4, 7915 and 7937 in M/5, 8927 and 8929 in N/4, 9904 in N/5) (Fig. 15.11). It was characterized by a soft brown layered matrix containing a few brick fragments, very rich in charred material (charcoal and grain), as well as sherds, bones, and fine plaster fragments of unknown origin. The layering of this accumulation was more pronounced in the eastern part, where the layers sloped down into the eastern section of Squares N/4–5. Several thin layers consisted of grayish material, possibly the remains of ash or decayed organics.

No architectural elements were noted in association with this thick accumulation. It clearly sealed the remains of Stratum D-8 and was superimposed by Stratum D-7b elements, most of which were pits dug into the aforementioned accumulation (see below). Therefore, it seems to belong to a post-D-8 and pre-D-7 phase. Nevertheless, it is difficult to suggest any clear explanation for such a thick accumulation, unless a gap in occupation enabled natural forces of sedimentation to operate undisrupted for an unknown time span. Another option is that this layer was a constructional fill related to the building of Stratum D-7b. Although no substantial architecture was found in the latter, the small size of the excavated area does not allow us to reach secure conclusions, and this option remains viable.

Pottery from loci attributed to this layer is presented together with that of Stratum D-8 in Figs. 16.16–16.23.

- Table 15.1

Stratigraphy and chronology in Area D, with correlation to Area C from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Table 15.1

Table 15.1

Stratigraphy and chronology in Area D, with correlation to Area C

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Table 15.2

Locus and basket numbers from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Table 15.2

Table 15.2

Locus and basket numbers

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1

Location of section drawings on superimposed plan of Strata D-11–D-2

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.2

Schematic section of Area D from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 17)

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2

Schematic section of Area D

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.12

Plan of Stratum D-7b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.12

Figure 15.12

Plan of Stratum D-7b

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.13

Plan of Stratum D-7a (encircled numbers denote foundation deposits as listed in the text) from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.13

Figure 15.13

Plan of Stratum D-7a (encircled numbers denote foundation deposits as listed in the text)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.14

Plan of Stratum D-7a' from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.14

Figure 15.14

Plan of Stratum D-7a'

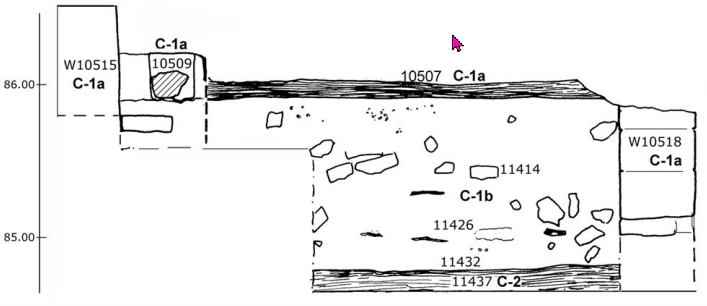

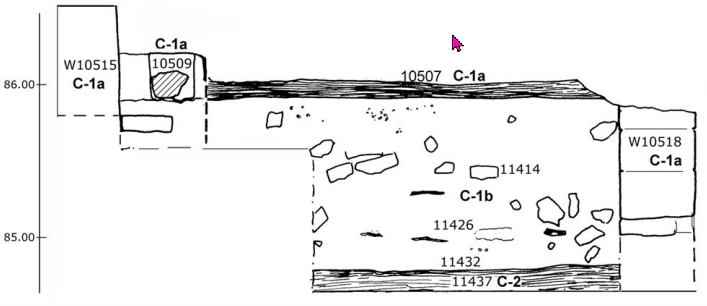

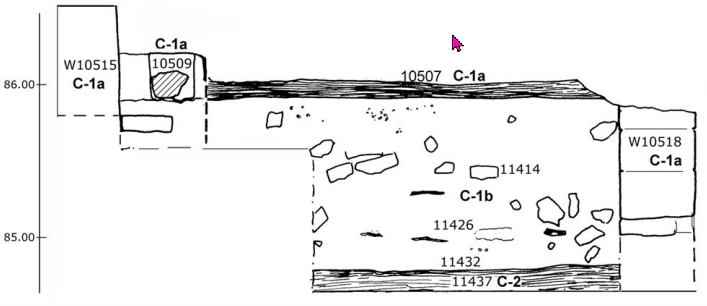

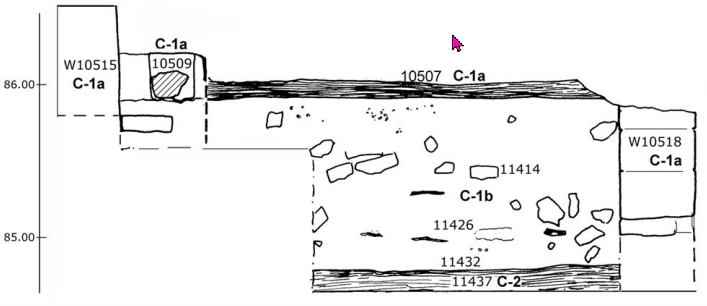

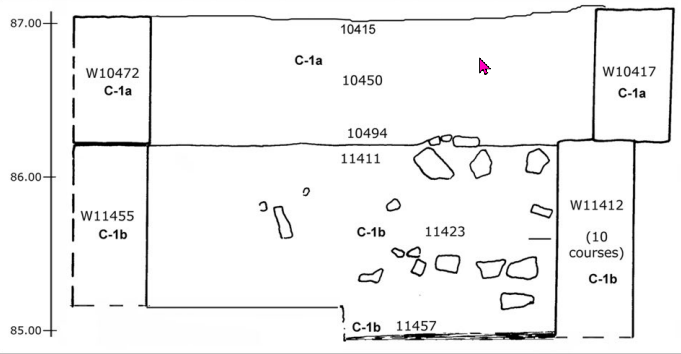

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.17a

Section 1a from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.17a

Figure 15.17a

Section 1a (Squares G–L/5, looking north, showing probe in alluvial field)

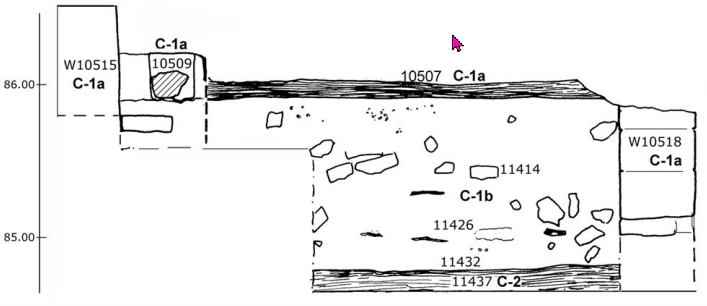

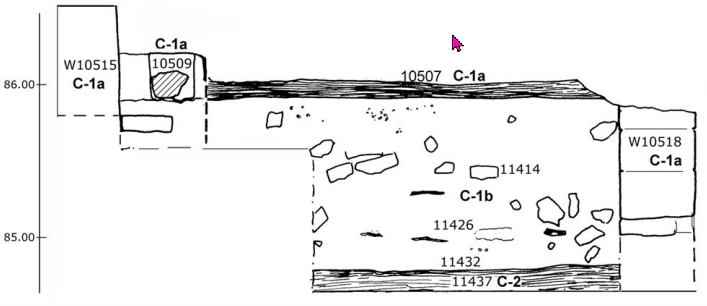

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.17b

Section 1b from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.17b

Figure 15.17b

Section 1b (Squares J–M/5 and part of N/5, looking north)

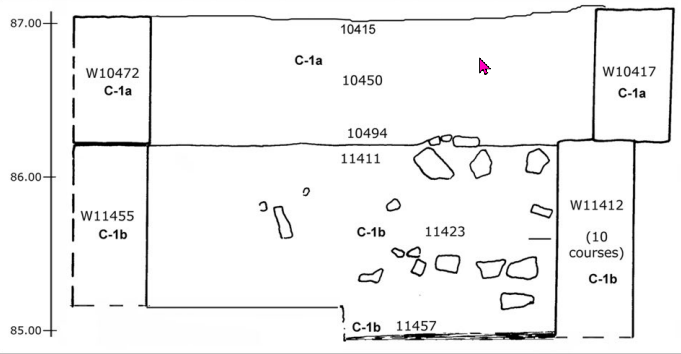

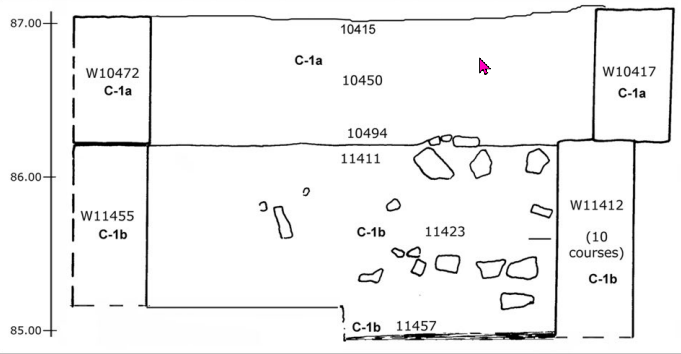

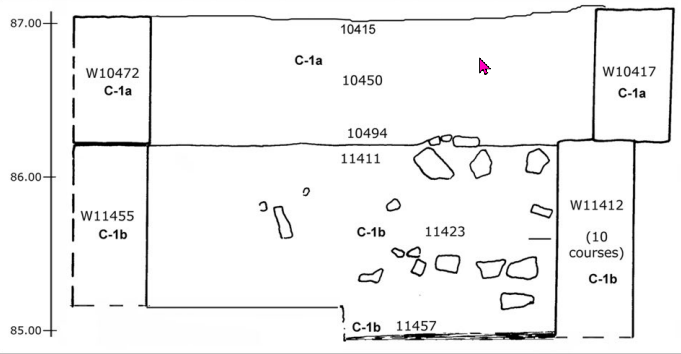

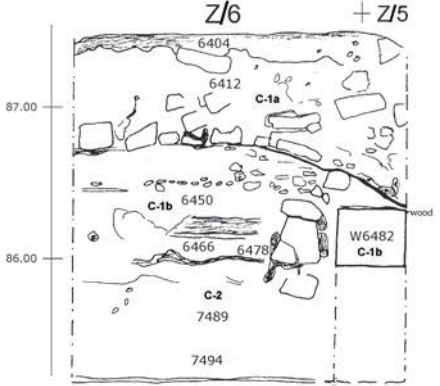

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.19

Section 3 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.19

Figure 15.19

Section 3 (Squares L–N/4, looking north)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.20

Section 4 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.20

Figure 15.20

Section 4 (Squares N–L/4, looking south)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Figure 15.21

Section 5 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Figure 15.21

Figure 15.21

Section 5 (Squares N/4–5, looking east)

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.3) - Photo 15.40

Squares M–N/4–5 from Mazar et. al. (2020 v. 3: Chapter 15)

Photo 15.40

Photo 15.40