Hazor

Aerial photo of Tel Hazor. Remains of Iron and Bronze Age cities are

seen in the upper tell, and the lower tell stretches to the right and beyond the frame of this photo.

Aerial photo of Tel Hazor. Remains of Iron and Bronze Age cities are

seen in the upper tell, and the lower tell stretches to the right and beyond the frame of this photo.Wikipedia - public domain

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Hazor | Hebrew | חצור |

| Chatsôr | Hebrew | חָצוֹר |

| Tel Hazor | Hebrew | תל חצור |

| Hasōr | Ancient Greek | Άσώρ |

| Tell el-Qedah | Arabic | تل القدح |

| Tell Waqqas | Arabic |

Razor, a large Canaanite and Israelite city in Upper Galilee, was identified by J. L. Porter in 1875 with Tell el-Qedah (also called Tell Waqqas), some 14km (8.5 mi.) north of the Sea of Galilee and 8 km (5 mi.) southwest of Lake I:Iula (map reference 203.269). This identification was proposed again in 1926 by J. Garstang, who conducted trial soundings at the site in 1928. Today, Kibbutz Ayelet ha-Shahar lies at the foot of the mound.

Yigal Yadin in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) wrote the following about the history of Hazor:

Hazor is first mentioned in the Egyptian Execration texts (published by G. Posener) from the nineteenth or eighteenth century BCE. It is the only Canaanite city mentioned (together with Laish-Dan) in the Mari documents of the eighteenth century BCE that point to Hazor having been one of the major commercial centers in the Fertile Crescent. The caravans plying between Babylon and Hazor passed through other large centers, such as Yamkhad and Qatna. Hazor is also mentioned frequently in Egyptian documents of the New Kingdom, such as the city lists of Thutmose III's conquests, the Leningrad Papyrus 1116-A , and city lists of Amenhotep II and Seti I.Yigal Yadin in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) reports that after the city was destroyed during the Assyrian conquest in 732 BCE, Hazor

The role of Hazor in the fourteenth century BCE, as reflected in the el-Amarna letters, is of particular significance. The kings of Ashtaroth in the Bashan and of Tyre accuse 'Abdi-Tirshi, king of Hazor, of having taken several of their cities. The king of Tyre furthermore states that the king of Hazor had left his city to join the Habiru. The king of Hazor, on the other hand, one of the few Canaanite rulers to call himself king (and to be called so by others), proclaims his loyalty to Egypt. In the Papyrus Anastasi I, probably dating from the time of Ramses II, the name of Hazor occurs together with that of a nearby river.

Hazor is first mentioned in the Bible in connection with the conquests of Joshua. The Bible relates that Jabin, king of Hazor, was at the head of a confederation of several Canaanite cities in the battle against Joshua at "the waters of Merom." Especially noteworthy are the verses: "And Joshua turned back at that time, and took Hazor, and smote its king with the sword; for Hazor formerly was the head of all those kingdoms .... and he burned Hazor with fire .... But none of the cities that stood on mounds did Israel burn, except Hazor only; that Joshua burned" (Jos. 11:10-13)1. Here, then, is a direct reference to the role of Hazor at the time of the Israelite conquest. Hazor is also indirectly mentioned in the account of Deborah's wars in the prose version preserved in Judges 4, in contrast to the "Song of Deborah", which describes a battle in the Valley of Jezreel without mentioning Hazor. In I Kings 9:15, it is related that Hazor, together with Megiddo and Gezer, was rebuilt by Solomon. According to 2 Kings 15:29, Hazor, among other Galilean cities, was conquered in 732 BCE by Tiglath-pileser III, king of Assyria.

The city is again mentioned indirectly in 1 Maccabees 11:67, which relates that Jonathan and his army marched northward from the Valley of Ginnosar in his campaign against Demetrius. Jonathan camped on the plain of Hazor (Γo πεδiov 'Aσωρov) near Cadasa. Josephus describes Hazor as situated above Lake Semachonitis (Antiq. V, 199).

remained uninhabited thereafter, except for occasional temporary occupations2 - lonely forts overlooking the Hula Valley and the important highways that passed it.

1 Amnon Ben-Tor, who has been in charge of renewed excavations starting in the 1990s, states (in the park brochure)

that archaeological finds show that Hazor was indeed burned in a huge conflagration, signs of which are visible

in both the upper and lower cities

but the relation between the archaeological record and the biblical story

is still a matter of debate among scholars

.

2 Amnon Ben-Tor states (in the park brochure) that after the [Assyrian destruction], settlement at Hazor was limited. A citadel was

built in the western, higher part of the upper city during the Assyrian, Persian and Hellenistic periods.

The site comprises two distinct areas: the mound proper, covering 30 a. (at the base) and rising about 40 m above the surrounding plain, and a large rectangular lower city of about 170 a. (1,000 by 700 m) to the north of the high mound. On the west the lower city is protected by a huge rampart of beaten earth and a deep fosse, on the north by a rampart alone, and on the east by a steep slope reinforced by supporting walls and a glacis. On the south, a deep fosse separates the lower city from the mound.

The results of Garstang's trial soundings (1928) on the mound and in the lower city (the "enclosure") were not published in detail. He concluded, inter alia, that the enclosure, which he called the camp area, was a camping ground for infantry and chariotry, rather than an actual dwelling area. As no Mycenean pottery was found, Garstang dated the final destruction of the site to about 1400 BCE, the period to which he assigned Joshua's conquest. On the west side of the mound proper stood a structure that he dated to the Israelite and Hellenistic periods (area B). In the center of the mound (area A), he found a row of pillars and assumed they were part of a stable from the time of Solomon.

From 1955 to 1958, the James A. de Rothschild Expedition, under the direction of Y. Yadin, conducted excavations on the site on behalf of the He brew University of Jerusalem in conjunction with PICA, the Anglo-Israel Exploration Society, and the Government of Israel. Among the members of the expedition were Y. Aharoni, C. Epstein, M. Dothan, T. Dothan, R. Amiran, I. Dunayevsky, J. Perrot, and E. Stern. During the first four seasons of work, several areas were excavated, both on the mound and in the lower city. Because of the great distances between the areas, separate stratum numbers were assigned to each. The dating of the strata at Razor and the correlation between the lower and upper cities are presented in the table at the end of this article.

Excavations were resumed in the summer of 1968 (the fifth season), under the direction of Y. Yadin, with A. Ben-Tor and Y. Shiloh as the main field directors and I. Dunayevsky as the team's architect. Excavations were renewed in 1990 as a joint project of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Complutense University at Madrid, in cooperation with Ambassador College at Big Sandy, Texas, and the Israel Exploration Society, under the direction of A. Ben-Tor.

The results of the excavations at Hazor enable us to reconstruct the history of the site and the nature of its settlement. In the third millennium BCE, the city was confined to the mound. At the end of this period there was a gap in occupation until the Middle Bronze Age I, when the mound proper was resettled.

The great turning point in the development of Hazor started in the Middle Bronze Age IIB (mid-eighteenth century BCE), when the large lower city was founded. Excavations in all the areas of the lower city proved that it should not be termed an enclosure or a camp but that it was a built-up area with fortifications, constructed by a new wave of settlers too numerous to settle within the upper city alone. Unlike the mound with its natural fortifications, here it was necessary to dig a large, deep fosse on the west; the excavated material was used to construct a rampart on the west and north. The slopes of the eastern side of the lower city were strengthened by the addition of a glacis. Thus, a fortified area came into being, within which the various structures of the lower city were built - the temples, public buildings, and private houses.

Because the mention of Hazor in the Mari documents presumably refers to the city only after the large lower city had been established, the results of the excavations lend support to the lower chronology for dating these documents - that is, to the end of the eighteenth century BCE.

The lower city flourished throughout the Late Bronze Age, being alternately destroyed and rebuilt. Hazor reached its peak in the fourteenth century BCE, the el-Amarna period, at which time it was the largest city in area in the whole land of Canaan. The final destruction of Canaanite Hazor, both of the upper and the lower cities, probably occurred in the second third of the thirteenth century BCE, by conflagration. This destruction is doubtless to be ascribed to the Israelite tribes, as related in the Book of Joshua.

Important evidence for understanding the process of Israelite settlement is the remains of stratum XII. These remains, which clearly belong to the twelfth century BCE, when Hazor ceased to be a real city, are essentially identical with the remains of the Israelite settlements in Galilee. This indicates, in the opinion of this writer, that the Israelite settlement, which was still semi-nomadic in character, arose only after the fall of the cities and provinces of Canaan.

Only from the time of Solomon onward did Hazor return to some extent to its former splendor, although on a smaller scale than in Canaanite times. Occupation was henceforth limited to the upper city.

In 732 BCE, Hazor was destroyed by the Assyrians. It remained uninhabited thereafter, except for occasional temporary occupations - lonely forts overlooking the Hula Valley and the important highways that passed it.

In 1990, 35 years after Y. Yadin began excavations at Tel Hazor, a renewed excavation dedicated to his memory commenced at the site and has been underway continuously every summer. The Selz Foundation Hazor Excavations in Memory of Y. Yadin are a joint project of the Philip and Muriel Berman Center for Biblical Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University, the Israel Exploration Society, and, until 2000, the Complutense University at Madrid. The renewed excavation is directed by A. Ben-Tor.

The excavations have three main objectives. First, they aim at assessing the stratigraphical, chronological, and historical conclusions outlined by the Y. Yadin expedition. Second, they explore several important issues not resolved by Yadin’s excavations. Noteworthy among these are chronological issues, including the rise of “greater Hazor,” the date of the fall of Canaanite Hazor, and the date of the Iron Age II fortifications (gate and casemate wall, the so-called “Solomonic Gate”), attributed by Yadin to the tenth century BCE; and the complete exposure of the structure investigated by Yadin and referred to by him as “the ‘palatial’ building of the Middle Bronze Age II,” the northeastern corner of which was discovered in 1958. The third objective of the renewed excavations is to preserve and partially restore some of the most important monuments uncovered, prevent their further deterioration, and help develop Hazor into an attractive site for visitors.

Whereas Yadin opened ten excavation areas in the upper and lower parts of the site, the renewed excavations opened only two, both of them in the upper city (the acropolis): area A, an expansion of Yadin’s area A in the center of the acropolis; and area M, on the northern edge of the acropolis, facing the lower city. In order to avoid confusion, it was decided to temporarily retain Yadin’s stratigraphic designations, despite the fact that as a result of the renewed excavations, it will be necessary to somewhat modify these designations, further subdivide various strata, and perhaps even add or omit strata.

The most complete stratigraphic sequence at Hazor was encountered in area A, where remnants of occupation from the Early Bronze Age through the Persian period were uncovered by the Yadin expedition. Also uncovered in area A were the “Solomonic fortifications,” the remains of the latest Late Bronze Age level, and what Yadin identified as the corner of Hazor’s Bronze Age palace. Hence, this area was chosen as the best place to attempt to check Yadin’s stratigraphy and chronological conclusions.

Area M is an expansion to the north and east of Yadin’s area M, opened in 1968. There were two main reasons behind the decision to return to this area. First, this is where Yadin’s excavations found the “joint” between the two major Iron Age fortification systems of the site, which he dated to the tenth and ninth centuries BCE, the reigns of Solomon and Ahab, respectively. It was one of the most disputed of Yadin’s chronological-historical conclusions, and it could be tested through work at this spot, along with the new information gleaned from the investigation in area A. The second reason it was chosen to work in area M has to do with the fact that the northern flank of the upper city (the acropolis) slopes steeply northward towards the lower city everywhere except in area M, at the middle of the slope, where there is a rather broad and flat terrace-like plateau. It was hoped that the investigation of this topographic feature might yield information on how the two parts of Hazor—the lower city and the acropolis—were connected.

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1Map of major archaeological and historical site in central and northern Israel and Jordan

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

- Annotated Satellite Image (google)

of Hazor from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Hazor

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of Hazor

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Aerial View of the Mound of

Hazor and surroundings from Kenyon (1978)

Figure 14

Aerial view of Hazor, excavated by Yadin, showing the bottle-shaped mound of the Upper City, to the south, in the foreground. It was the nucleus of the settlement on this site from the earliest occupation there through to the first millennium BC. Beyond it is the vast enclosure marking the Lower City, established sometime in the earlier second millennium BC (Middle Bronze Age), and occupied down to the early thirteenth century BC (towards the end of the Late Bronze Age).

click on image to open in a new tab

Kenyon (1978) - Hazor in Google Earth

- Hazor on govmap.gov.il

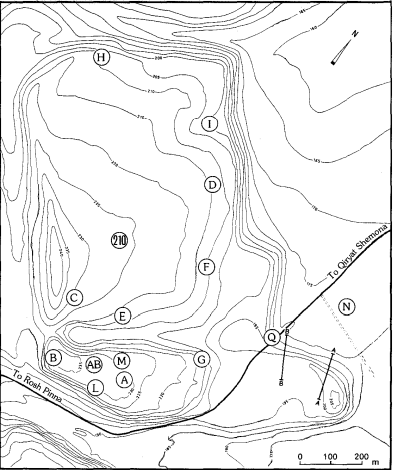

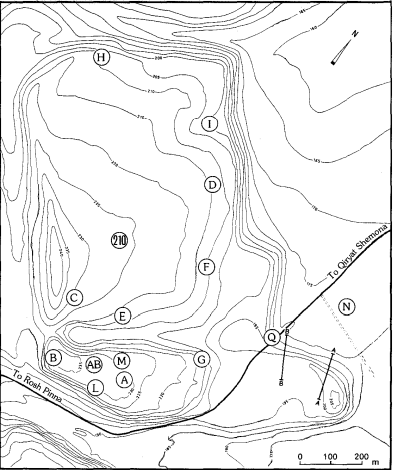

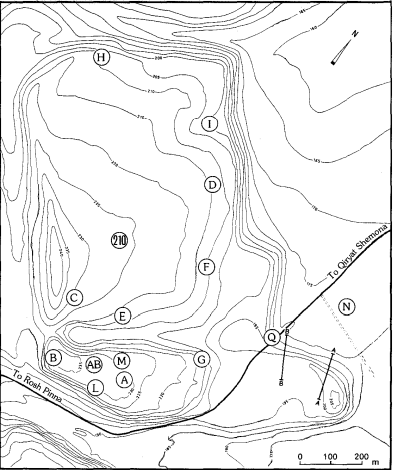

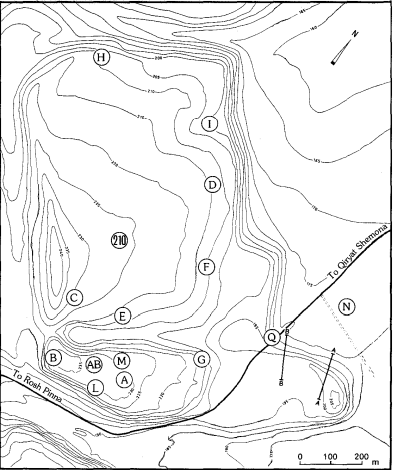

- Map of the mound,

the lower city, and excavation areas and excavation areas from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Map of the mound, the lower city, and excavation areas.

Map of the mound, the lower city, and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993). - Map of the excavation

areas and principal remains of the Upper City from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Map of the excavation areas and principal remains of the Upper City

Map of the excavation areas and principal remains of the Upper City

Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Map of the mound,

the lower city, and excavation areas and excavation areas from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Map of the mound, the lower city, and excavation areas.

Map of the mound, the lower city, and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993). - Map of the excavation

areas and principal remains of the Upper City from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Map of the excavation areas and principal remains of the Upper City

Map of the excavation areas and principal remains of the Upper City

Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Aerial view of Area A

from Stern et al (2008)

Area A: aerial view looking northwest

Area A: aerial view looking northwest

Stern et. al. (2008). - Close air-view of Area A

at end of 1958 season from Yadin et al (1961)

Area A: Plate II

Area A: Plate II

Looking south. Close air-view of Area A at end of 1958 season. Below, the city-gate and the casemate wall (Strata IX-X). In centre and under city-gate, structures of the Bronze Ages. Above, the pillared building (Strata VII-VIII). To its right and above it, buildings of Strata V-VI

Yadin et al (1961) - Close air-view of Area A

at end of 1957 season various from Yadin et al (1961)

Area A: Plate III

Area A: Plate III

Looking south. Close air-view of Area A at end of 1957 season. Below, the city-gate and the casemate wall (Strata IX-X). Above, the pillared building (Strata VII-VIII) and above it, buildings of Strata V-VI

Yadin et al (1961) - Aerial View of the

main Iron Age remains of the Upper City from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Aerial View of the main Iron Age remains [Upper City]

Aerial View of the main Iron Age remains [Upper City]

Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Aerial view of Area A

from Stern et al (2008)

Area A: aerial view looking northwest

Area A: aerial view looking northwest

Stern et. al. (2008). - Close air-view of Area A

at end of 1958 season from Yadin et al (1961)

Area A: Plate II

Area A: Plate II

Looking south. Close air-view of Area A at end of 1958 season. Below, the city-gate and the casemate wall (Strata IX-X). In centre and under city-gate, structures of the Bronze Ages. Above, the pillared building (Strata VII-VIII). To its right and above it, buildings of Strata V-VI

Yadin et al (1961) - Close air-view of Area A

at end of 1957 season various from Yadin et al (1961)

Area A: Plate III

Area A: Plate III

Looking south. Close air-view of Area A at end of 1957 season. Below, the city-gate and the casemate wall (Strata IX-X). Above, the pillared building (Strata VII-VIII) and above it, buildings of Strata V-VI

Yadin et al (1961) - Aerial View of the

main Iron Age remains of the Upper City from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Aerial View of the main Iron Age remains [Upper City]

Aerial View of the main Iron Age remains [Upper City]

Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Plate XIII - Plan of Area A

Stratum VI from Yadin et al (1961)

Plate XIII

Plate XIII

Plan of Area A Stratum VI

Yadin et al (1961) - Fig. 48 - Plan of Area A

Stratum VI from Yadin (1970)

Fig. 48

Fig. 48

Area A Stratum VI

Yadin (1970) - Fig. 3 - Plan of Area A

Strata V-VIII from Shochat and Gilboa (2018)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Area A at the end of Yadin’s fourth season

(1958; Yadin et al. 1961: pl. II; courtesy of The Israel Exploration Society).

Shochat and Gilboa (2018) - Fig. 6b - Plan of Area A

Stratum VI from Shochat and Gilboa (2018)

Figure 6b

Figure 6b

Area A, plan of Stratum VI as excavated by Yadin. The ‘Annexed Halls’ continue in use also in Stratum VI

(Yadin et al. 1960: pls CCII, CCIII; courtesy of The Israel Exploration Society).

Shochat and Gilboa (2018) - Fig. 6b - Plan of Area A

Stratum VI (closeup) from Shochat and Gilboa (2018)

Figure 6b

Figure 6b

Area A, plan of Stratum VI as excavated by Yadin. The ‘Annexed Halls’ continue in use also in Stratum VI

(Yadin et al. 1960: pls CCII, CCIII; courtesy of The Israel Exploration Society)

N arrow added by JW

Shochat and Gilboa (2018) - Plan of Area A from

Avi-Yonah et. al. (1975 v. 2 English version)

Plan of Area A

Plan of Area A

Strata according to fill

- No Fill - VI

- Shaded Fill - X-XI

- Black Fill - VIII-VII

Avi-Yonah et. al. (1975) - Fig. 2 - Area A Map of

Excavation Areas from Ben-Tor (2004)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map of Excavation Areas

Ben-Tor (2004)

- Plate XIII - Plan of Area A

Stratum VI from Yadin et al (1961)

Plate XIII

Plate XIII

Plan of Area A Stratum VI

Yadin et al (1961) - Fig. 48 - Plan of Area A

Stratum VI from Yadin (1970)

Fig. 48

Fig. 48

Area A Stratum VI

Yadin (1970) - Fig. 3 - Plan of Area A

Strata V-VIII from Shochat and Gilboa (2018)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Area A at the end of Yadin’s fourth season

(1958; Yadin et al. 1961: pl. II; courtesy of The Israel Exploration Society).

Shochat and Gilboa (2018) - Fig. 6b - Plan of Area A

Stratum VI from Shochat and Gilboa (2018)

Figure 6b

Figure 6b

Area A, plan of Stratum VI as excavated by Yadin. The ‘Annexed Halls’ continue in use also in Stratum VI

(Yadin et al. 1960: pls CCII, CCIII; courtesy of The Israel Exploration Society).

Shochat and Gilboa (2018) - Fig. 6b - Plan of Area A

Stratum VI (closeup) from Shochat and Gilboa (2018)

Figure 6b

Figure 6b

Area A, plan of Stratum VI as excavated by Yadin. The ‘Annexed Halls’ continue in use also in Stratum VI

(Yadin et al. 1960: pls CCII, CCIII; courtesy of The Israel Exploration Society)

N arrow added by JW

Shochat and Gilboa (2018) - Plan of Area A from

Avi-Yonah et. al. (1975 v. 2 English version)

Plan of Area A

Plan of Area A

Strata according to fill

- No Fill - VI

- Shaded Fill - X-XI

- Black Fill - VIII-VII

Avi-Yonah et. al. (1975) - Fig. 2 - Area A Map of

Excavation Areas from Ben-Tor (2004)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map of Excavation Areas

Ben-Tor (2004)

- from Ben-Tor et. al. (1989:42-43)

- from archive.org

- If you can't see the plan, click one of the links above to open a new tab and borrow the book. Then refresh this page.

- Artists Rendition of Area A

Stratum VI Buildings from Sign at Hazor Site/Park (Solomonic Gate and Public and Private Dwellings)

Artists Rendition Area A Stratum VI Buildings

Artists Rendition Area A Stratum VI Buildings

Solomonic Gate, Public and Private Dwellings

Hazor Park/Site Sign

Photo by Jefferson Williams 17 April 2023 - Fig. 1 - Reconstruction of

Stratum VI Building from Yadin et al. (1960)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Reconstruction of Stratum VI Buildings

(Isometric Projection)

Yadin et al. (1960)

- Artists Rendition of Area A

Stratum VI Buildings from Sign at Hazor Site/Park (Solomonic Gate and Public and Private Dwellings)

Artists Rendition Area A Stratum VI Buildings

Artists Rendition Area A Stratum VI Buildings

Solomonic Gate, Public and Private Dwellings

Hazor Park/Site Sign

Photo by Jefferson Williams 17 April 2023 - Fig. 1 - Reconstruction of

Stratum VI Building from Yadin et al. (1960)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Reconstruction of Stratum VI Buildings

(Isometric Projection)

Yadin et al. (1960)

- Area A - Plate IX.2 -

Southward-leaning wall within Hazor Stratum VI from Yadin et al. (1960)

Area A Plate IX 2.

Area A Plate IX 2.

Looking east. Northern wall of Locus 113 (Stratum VI) found slanting as the result of an earthquake. To left, southern wall of pillared-Building (Stratum VIII)

[Description by Austin et. al. (2000) - Southward-leaning wall within Hazor Stratum VI (Area A, Locus 113). Many walls within Stratum VI that did not collapse show significant tilt southward. The rod was oriented to vertical using the plumb line. Thickness of the wall is ~1 m (from Yadin et al., 1960, plate IX).]

Yadin et al. (1960) - Area A - Plate IX.3 -

Wall collapse within Hazor Stratum VI from Yadin et al. (1960)

Area A Plate IX 3.

Area A Plate IX 3.

Looking west. Locus 78 (Stratum VI). In the northwest corner of this room can be seen segment of wall that collapsed as the result of an earthquake.

Yadin et al. (1960) - Area A - Plate IX.4 -

Wall after removal of collapse debris within Hazor Stratum VI from Yadin et al. (1960)

Area A Plate IX 4.

Area A Plate IX 4.

Looking west. Same as above [Area A Plate IX 3.] after removal of wall debris. In the centre, entrance of Locus 78 (Stratum VI) blocked by stone debris. To right, slanting northern wall.

Yadin et al. (1960) - Bronze Age (Canaanite) Wall

Collapse at Tel Hazor - photo by Jefferson Williams

Bronze Age (Canaanite) Wall Collapse at Tel Hazor

Bronze Age (Canaanite) Wall Collapse at Tel Hazor

photo by Jefferson Williams from April 2023

- from Zuckerman (2013)

| Fixed date (BCE) | Archeological Period | Stratum (Layer) - Upper City | Stratum (Layer) - Lower City | Excavation results | Historical references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28th century | Early Bronze Age III-II | XXI | Houses | ||

| 27th century 24th century |

Early Bronze Age III | XX-XIX | Houses and a monumental structure (possibly a palace or other central building) | ||

| 22nd century 21st century |

Middle Bronze Age I/Intermediate Bronze Age | XVIII | Houses | ||

| 18th century | Middle Bronze Age IIA-B | Pre XVII | Burials and structures | Egyptian Execration Texts | |

| 18th century 17th century | Middle Bronze Age IIB | XVII | 4 | Erection of the earthen rampart of the Lower City | Mari archive |

| 17th century 16th century | Middle Bronze Age IIB | XVI | 3 | Both Upper and Lower Cities are settled. | |

| 15th century | Late Bronze Age I | XV | 2 | Both Upper and Lower Cities are settled. | Annals of Thutmose III |

| 14th century | Late Bronze Age II | XIV | 1b | Both Upper and Lower Cities are settled. | Amarna letters |

| 13th century | Late Bronze Age II | XIII | 1a | Both Upper and Lower Cities are settled. | Papyrus Anastasi I |

| 11th century | Iron Age I | XII-XI | pits and meager architecture | ||

| mid 10th century early 9th century |

Iron Age IIA | X-IX | six-chambered gate, casemate wall, domestic structures | United Kingdom of Israel (possibly under Solomon) | |

| 9th century | Iron Age IIA-B | VIII-VII | casemate wall still used, administrative structures and domestic units | Northern Kingdom of Israel (Omri dynasty) | |

| 8th century | Iron Age IIC | VI-V | casemate wall still used, administrative structures and domestic units | Northern Kingdom of Israel (from under Jeroboam II to the Assyrian destruction by Tiglath-pileser III | |

| 8th century | Iron Age IIC | IV | sporadic settlement | post–Assyrian destruction; settlement (possibly Israelite) | |

| 7th century | Iron Age IIC (Assyrian) | III | governmental structures on and around the tell | ||

| 5th century 4th century |

Persian | II | citadel, tombs | ||

| 3rd century 1st century |

Hellenistic | I | citadel |

- from Finkelstein (1999)

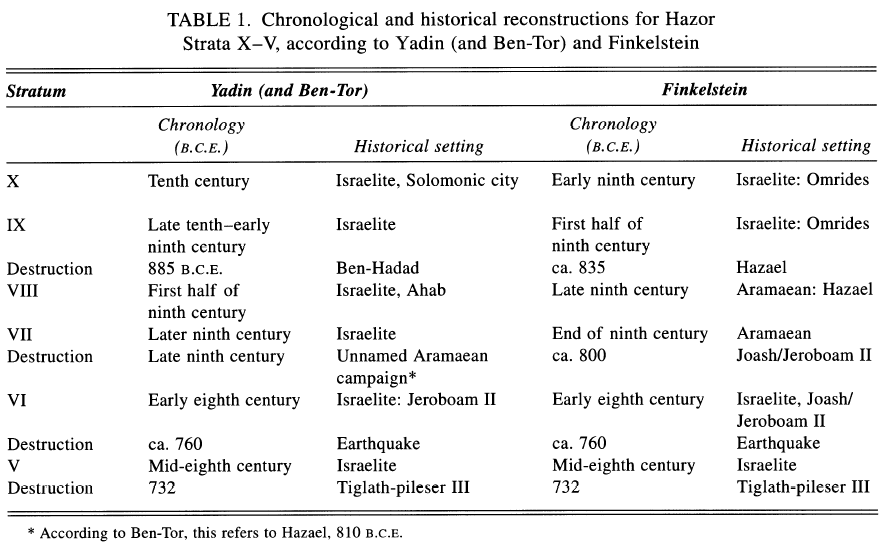

Table 1

Table 1Chronological and historical reconstructions for Hazor Strata X-V, according to Yadin (and Ben-Tor) and Finkelstein

Finkelstein (1999)

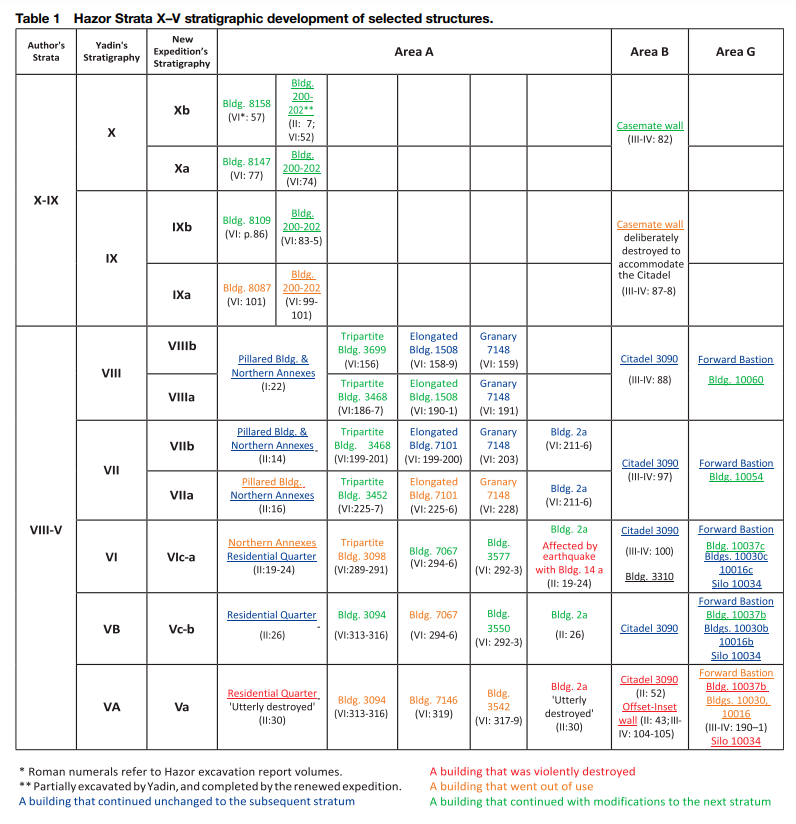

Table 1

Table 1Hazor Strata X–V stratigraphic development of selected structures.

Shochat and Gilboa (2018)

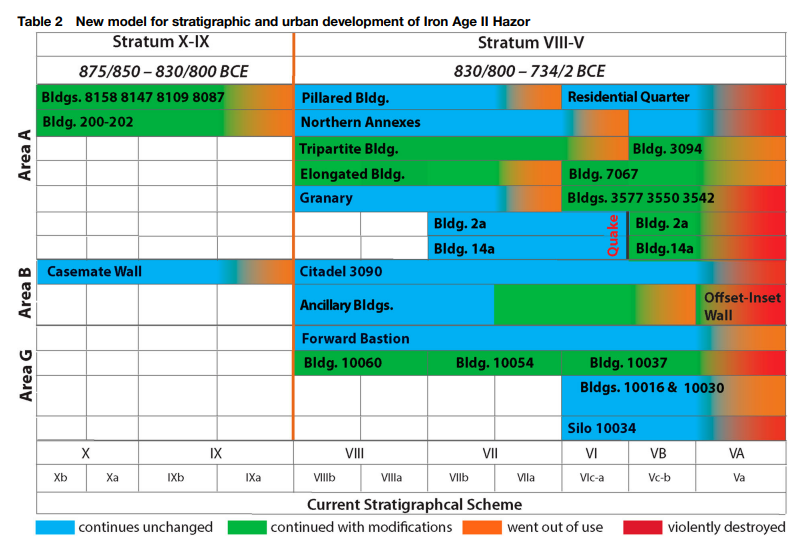

Table 2

Table 2New model for stratigraphic and urban development of Iron Age II Hazor

Shochat and Gilboa (2018)

- Area A - Plate IX.2 -

Southward-leaning wall within Hazor Stratum VI from Yadin et al. (1960)

Area A Plate IX 2.

Area A Plate IX 2.

Looking east. Northern wall of Locus 113 (Stratum VI) found slanting as the result of an earthquake. To left, southern wall of pillared-Building (Stratum VIII)

[Description by Austin et. al. (2000) - Southward-leaning wall within Hazor Stratum VI (Area A, Locus 113). Many walls within Stratum VI that did not collapse show significant tilt southward. The rod was oriented to vertical using the plumb line. Thickness of the wall is ~1 m (from Yadin et al., 1960, plate IX).]

Yadin et al. (1960) - Area A - Plate IX.3 -

Wall collapse within Hazor Stratum VI from Yadin et al. (1960)

Area A Plate IX 3.

Area A Plate IX 3.

Looking west. Locus 78 (Stratum VI). In the northwest corner of this room can be seen segment of wall that collapsed as the result of an earthquake.

Yadin et al. (1960) - Area A - Plate IX.4 -

Wall after removal of collapse debris within Hazor Stratum VI from Yadin et al. (1960)

Area A Plate IX 4.

Area A Plate IX 4.

Looking west. Same as above [Area A Plate IX 3.] after removal of wall debris. In the centre, entrance of Locus 78 (Stratum VI) blocked by stone debris. To right, slanting northern wall.

Yadin et al. (1960)

Yadin et. al. (1960) uncovered collapsed and tilted walls in Stratum VI of Area A which he dated to the 8th century BCE and before destruction of Stratum V in the Assyrian conquest in in 732 BCE. Yadin et. al. (1960:24-26) described their findings as follows:

In the 1956 season we were able to establish that Stratum VI was destroyed by an earthquake. Many walls in this stratum were found bent or cracked; in several places we found debris of walls lying course on course, just as is found in earthquakes when the entire wall collapses at once. The direction in which the walls leant or fell was southerly or easterly, according to the direction in which they ran. In some cases the upper part of the wall collapsed and the lower part remained standing but leaning. Leaning walls were used as a foundation for Stratum V when rebuilding began. Signs of the earthquake were most striking in the following rooms:Yadin et. al. (1960:36) re-iterated this in their Chronological Conclusions.

Geologists from the Hebrew University, to whom we showed these phenomena when they visited the site, confirmed our supposition that Hazor had been some distance from the epicentre of the earthquake. Strong walls had therefore stood up to the shock, while others had been only partially wrecked, even remaining standing in places, albeit at a slant. This partial destruction is seen again in the levels of the walls that survived from Stratum VI: some were preserved to a height of 2 m., others were totally wrecked.

- 78 — The N. wall was leaning to the S., and was partly supported by the debris that blocked the W. entrance to the room. Next to the wall was a sloping pile of debris made up of courses of stones; buried beneath it were several vessels (Pl. IX, 3, 4). The earthquake wrought most havoc in this room, and it was the wreckage here that first gave us the clue to the disaster.

- 14a ["The House of Makhbiram"]— The W. wall leans sharply to the E., the E. wall less so (Pl. VII, 4).

- 113 - The W. wall is cracked down the middle and leans eastwards. The N. wall leans southwards very markedly (Pl. IX, 2).

- 21a — The E. wall slants eastwards, and fallen courses of stones covered the street to the E. of the room (28a).

The damage done was repaired at once and the buildings were rebuilt. Some of them were rebuilt by the former inhabitants, to judge by the astonishing resemblance between Stratum VI and Stratum V, in which most of the buildings rose again with very slight changes. The various special installations — silos and ovens — were also rebuilt. The similarity is most striking in Room 24, in which new, almost identical silos were built on top of the old ones, and in the restoration of the special ovens in "Makhbiram's House" (made of upturned jars), although now the ovens were in another room, owing to certain changes in plan. Likewise, even in the rooms where the walls stood unaltered we found a new and raised floor, evidently built over the debris of the fallen ceilings.

Area A - Chronological Conclusions

... (b) Stratum VI. Another absolute date is provided by the earthquake that destroyed Stratum VI. Since Stratum V (see below) end with the glut destruction of 732 B.C., and Strata VIII-VII belong to the 9th century B.C. 215, it is cleat that Stratum VI belongs to the 1st half of the 8th century B.C. It can hardly be a matter of chance that precisely from this period we have records of a severe earthquake remembered for generations216. This earthquake caused widespread ruin and a general flight from the towns, reflected in the words of Zechariah: "Yea. ye shall flee, like as ye fled from before the earthquake in the days of Uzziah, king of Judah;" (XIV, 5). So deep and abiding was the memory of the disaster that events were dated from it, at we read in the Bible: "The words of Amos, who was among the herdsmen of Tekoa, which he saw concerning Israel in the days of Uzziah king of Judah, and in the days of Jeroboam the son of Joash king of Israel, two years before the earthquake." (I.1).

Thee date of this great earthquake can be fixed at about 760 B.C., and this date therefore marks the end of Stratum VI and the beginning of Stratum V.Footnotes215. See the article by Aharoni and Amiran (note 89 above) for their views on the synchronization of these (and later) strata at Hazor with those at Samaria.

216. For Yadin's views on the results of this earthquake at Samaria, and on the synchronization of the later strata at Hazor with the Samaria strata, see Y. Yadin: Ancient Judean Weights and the Date of the Samarian Ostraca, scripta Hierosolymitana VI, 1959, note 73.

Indications of the destruction of stratum VI by earthquake, noted by Yadin, were not identified. There is an evident decline in the urban layout of the city in the eighth century (strata VI–V) relative to the ninth century, when area A in the center of the town had been strewn with buildings of a public nature. However, the dwellings which replace the huge storehouses that once stood there still exhibit a degree of affluence. Mostly belonging to variants of the four-room house type, they are rather spacious domiciles, measuring c. 150 sq m each, and carefully planned and well built, as befits a neighborhood located at the very center of the city. The renewed excavations have defined more sub-phases in this period than were reported by Yadin, resulting in a very dense stratigraphic sequence for the tenth–eighth centuries BCE, unparalleled at any contemporary site in the country. The latest remains in both areas A and M (Yadin’s stratum VA) were found to have been violently destroyed and covered by a thick layer of ash and debris, clearly associated with Hazor’s destruction in 732 BCE by the Assyrians.

- Figure 2 - Southward-leaning wall

within Hazor Stratum VI Area A from Austin et. al. (2000)

FIG. 2

FIG. 2

Southward-leaning wall within Hazor Stratum VI (Area A, Locus 113). Many walls within Stratum VI that did not collapse show significant tilt southward. The rod was oriented to vertical using the plumb line. Thickness of the wall is ~1 m (from Yadin et al., 1960, plate IX).

Austin et. al. (2000) - Figure 3 - Time-stratigraphic

correlation chart of Iron IIb excavations throughout an extensive region of Israel and Jordan from Austin et. al. (2000)

FIG. 3

FIG. 3

Time-stratigraphic correlation chart of Iron IIb excavations throughout an extensive region of Israel and Jordan. Datum for correlation is earthquake debris or rebuilding horizons assigned to a single, 750 B.C. seismic event. Locations of cities are shown in Figure 1. Strata names at each site are from primary archaeological reports.

Symbols

- P = pottery date

- C-14 = radiocarbon date

- T = dated text material

- D = military destruction layer with historical date assigned

- A = historically dated architectural style

- E = earthquake destruction layer

- E ? = probable earthquake destruction layer (significant rebuilding horizon without evidence of military conquest)

Austin et. al. (2000)

Austin et. al. (2000) summarized 8th century BCE Archaeoseismic evidence at Hazor

Archaeological excavations at Hazor revealed graphic evidence of earthquake destruction within Stratum VI throughout Area A (Yadin et al., 1958, 1960, 1961). Walls tilted or fell in a southerly or easterly direction, roofs collapsed, and pillars inclined. The House of Makhbiram was excavated with collapsed walls (Yadin et. al., 1960, p. 19-29, 36). The building called Yael's House was excavated, with objects of daily use found beneath the collapsed ceiling. Southward-leaning walls were common near the house (Fig. 2) and characterize the orientation of the collapse debris generally. Sixteen short pillars in the adjacent courtyard were each excavated in standing position but tilted significantly from vertical (Yadin, 1975, p. 152, 153) [JW: The sixteen pillars appear to come from different older Strata (VII-VIII instead of VI). If so, they are unrelated to an 8th century BCE earthquake]. Renewed excavations within Hazor's Stratum VI by Ammon Ben-Tor unearthed further evidence of seismic destruction (Dever, 1992). The stratigraphy of the late Iron Age in Israel is summarized in Figure 3. Hazor's Stratum VI, which is terminated by debris from the severe earthquake, contains superior masonry buildings, providing evidence of prosperous economic conditions in the kingdom of Israel associated with Jeroboam II's northward expansion of ~760 B.C. into Syria (2 Kings 14:25; Yadin, 1975; Finkelstein, 1999). Stratum V, which overlies Stratum VI, contains destruction debris and a charcoal horizon marking the end of Hazor as a fortified city upon the conquest of northern Israel by Tiglath-pileser III, the king of Assyria, in 732 B.C. (2 Kings 15:29; Yadin, 1975; Finkelstein, 1999). Thus, a strong argument can be made for dating Hazor's earthquake to 760 B.C. ± 20 years, the year 760 being specified by Yadin, 1975 and Finkelstein, 1999 from their stratigraphic analysis of the destruction debris.

- Figure 6 - Map of Israelite and Phoenician cities

ca. 1500-574 BCE from Ben-Menahem (1991)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Israelite and Phoenician cities during circa 1500-574 B.C.E.

(Published with permission of Whitehouse and Whitehourse [1975, p. 103] and W.H. Freeman Publishing House)

Ben-Menahem (1991) - Figure 7 - Southward-tilting northern wall

within Hazor Stratum VI Area A from Ben-Menahem (1991)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Tilting toward the south of a northern wall at Hazor, caused by the earthquake of 759 B.C.E. The direction of tilt of the shown wall and others in the same site reveal that the causative fault was to the NE of Hazor.

Ben-Menahem (1991) - Figure 8 - Horizontal shear (SH) acceleration

in the near field from Ben-Menahem (1991)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Azimuthal horizontal shear (SH) acceleration in the near field of the M = 7.3 earthquake of 759 B.C.E. Northern walls at Hazor tilted southward, while western walls tilted eastward [ Yadin et al., 1959], in accord with a left-hand strike slip fault, circa 20 km, NE of the city.

Ben-Menahem (1991)

Ben-Menahem (1991) surmised that

the location of the causative faultcould

be estimated from the oriented tilt of the walls in stratum 6 at Hazor (Figure 6), a detail of which is shown in Figure 7.He added

According to the report of the excavating archeologists [Yadin et al., 1959], northern walls were tilted southward, while western walls tilted eastward. Figure 8 shows that these orientations are consistent with the effect of a near field horizontal shear acceleration coming to Hazor from the north east. This is consistent with modern ideas that structures in the near-field of a major earthquake are mostly affected by SH body waves and the fundamental Love mode.Ben-Menahem (1991) estimated the following seismic source parameters

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| ML - Local Magnitude | 7.3 |

| Fault Motion | Left Hand Strike Slip |

| Latitude | 33.0° N |

| Longitude | 35.5° E |

- from Danzig (2011:15-26)

Tectonic faults are found throughout the fertile crescent due to the impingement of the Arabian plate on the

Eurasian, leading to mountain building of the Zagros and Taurus, and to the abutment of the Arabian and African

Plates (see Figure 1). One might say that this ongoing geological process is what created many of the large

scale landscape features that allowed for the growth of many ancient peoples and civilizations.

More specific to ancient Israel is the Dead SeaTransform, the northern extension of the Syro-African Rift between

the African and Arabian plates (see Figure 2). It stretches from the Gulf of Aqaba in the south into southeastern

Turkey.The current intersection of these plates is a left-lateral strike-slip fault. The motion along these

faults is due to the fact that although both plates are moving northward, the Arabian plate is moving faster than

the African and to the northeast.46 Earthquakes along the Dead Sea Transform result from the

non-continuous movement directly along the faults as the local ground moves in order to release the

built up energy from the plate's movement.

Earthquakes due to movement in this array of faults have

been evidenced for over the past 50,000 years.47

Our knowledge of seismic activity before the past 4,000 years comes from

paleoseismological research that uses geological information, such as lake bed cores of the Dead Sea,

to analyze ancient seismicity. From then through 1900 C.E., two other sources of information are available:

textual evidence, of which the references in Amos are some of the oldest, and archaeological evidence.

Direct seismographic data has been accumulated only over the past century.48

Archaeologists have sporadically and unevenly attempted to interpret some archaeological arrangements

as evidence of earthquake damage. Initial suggestions of earthquake damage, in the first half of the 20th

century, were most often in interpretation of destructions levels. Toward the middle of the century,

these ideas were commonly dismissed and even ridiculed, but over the past two decades a significant change

has come about in which archaeologists and seismologists have begun to collaborate as part of a new discipline,

Archaeoseismology. With the new combination of methods, confidence has been raised in assertions of earthquake

damage in some instances, although many such ascriptions have yet to be reinvestigated and the methodologies

are still in flux. A series of attempts have been made at assembling criteria by which certain configurations

of ancient ruins may be ascribed to seismic activity.49 Most recently, there has been movement in

the direction of applying more quantitative measures, often drawn from seismology, to these archaeological

problems in order to allow for factors pro and con to be more easily weighed, which is very difficult when

dealing solely with various, isolated, qualitative facts and their interpretation. A very promising quantitative

approach, which attempts to encompass all possible factors on multiple levels of

resolution as well as providing results that should be easy to compare across the board, is a scale of the

probability for the assignment of such evidence to earthquakes that has been adopted from paleoseismology.50

Regarding the earthquake referenced in Amos, strata identified as belonging to Iron Age IIB in the

8th century BCE, at sites as far flung as Hazor and Meggido in the north, Gezer and Lachish in the middle, and

Beersheba and Tell Deir Alla in the south, have been proposed as containing damage from this earthquake (see Table 2 for a list).

Some archaeological arrangements that have been suggested as possibly indicative of earthquake damage related to the

earthquake in Amos are: site abandonment; building restorations; destruction layers;destroyed buildings; and deformation

of buildings or city walls, including fallen, tilted, or displaced walls, displaced blocks, or cracks in wall stones,

especially vertically and in a series of contiguous stones. Since many of these things can happen in connection with

normal geological processes over longer stretches of time,51 scholars have sought criteria for better identification of finds.52

Most important other than identifying possible reasons for the unusual geometry of finds are stratigraphic considerations.53

Also, one must keep in mind that in areas where earthquakes are common, damage often occurs as an accrual of smaller structural

problems from several earthquakes over longer spans of time, rather than of major collapse at one time.54

Yigael Yadin was the first to attempt to ascribe an archaeological arrangement to the earthquake mentioned

in the Book of Amos. Yadin excavated for four seasons in 1955-58,working in several different areas on

Tell Hazor, as well as one season in 1968. He claimed to have found evidence for earthquake-related ruins

at Hazor in his Stratum VI, which he dated to the 8th century B.C.E., to the time of Jeroboam II, and connected

it to the earthquake mentioned in Amos. Aside from the excavation reports,55 Yadin describes and

interprets his excavations in two later works, Hazor: Head of All Those Kingdoms, the 1972 publication of the Schweich

Lectures he gave in 1970,56 and Hazor: The Rediscovery of a Great Citadel of the Bible

, 1975.57 Further excavations, directed by Amon Ben-Tor, began in 1990 and are ongoing, but

only partially published.58

Yadin reported observations of several leaning walls, some partially collapsed walls, and fallen ceiling materials as

proof of his interpretation of earthquake damage. All of this damage was found in levels he ascribed to Stratum

VI in Area A, on the middle of the upper citadel area of the tell (see Figure 3). Yadin described this area in Stratum VI

as mostly shops and workshops.59 Another building with purported earthquake damage is Building 2a (see Figure 4).60

Yadin claims, based on his observations, that "[t]he house was severely damaged by an earthquake."61

Yadin also noted “that floors of many of the houses were covered by fragments of the ceilings

that had fallen suddenly,” which he claims is an “unusual phenomenon in archaeological excavations.”

In room 148, built in a room of an older casemate wall, they found “great blocks of fallen bricks,”

which Yadin surmised were found from the earlier city wall and reused, “from beneath which were

visible fragments of many vessels” from walls built above the remaining height of the casemate walls.

“The rest of the room was full of jars and other vessels, standing side by side and smashed to bits

by the fallen roof,” a hypothesis that Yadin supports by explaining that “[they] managed to restore

most of them, which shows that the roof fell in suddenly.”63 In Building 2a, “all the floors were

littered with hundreds of pieces of ceiling plaster,”64 including a large chunk in room 82a.

Shulamit Geva, in an analysis of the site based solely on Yadin’s published reports, lists

items buried in several rooms. She ascribes their buried position to the earthquake, and it

seems that she means they were located so due to fallen ceilings. Yadin went so far with

his emphatic descriptions of purported earthquake damage in his popular book as to imagine

that “[t]here was evidence that the ‘last supper’ of the residents, eaten just before the

quake, consisted, among other things, of olives, if the many olive stones found on the

floor are any indication.” The implication is that those olive remains were a meal left

abandoned and caught under the rubble of the fallen ceilings.

In summary of his findings, Yadin states, “In the 1956 season we were able to establish

that Stratum VI was destroyed by an earthquake.” Yadin supports his interpretation with

anonymous, undocumented expert assessment, writing, “Geologists from the Hebrew University,

to whom we showed these phenomena when they visited the site, confirmed our supposition that

Hazor had been some distance from the epicenter of the earthquake. Yadin seems to understand

the earthquake as the main factor in the transition between Strata VI-V: “The destruction

wrought by the earthquake was quickly repaired and the next city represented by Stratum V

is very similar indeed in character to that of Stratum VI,” and “Stratum V […] was rebuilt

immediately following the destruction of City VI by the earthquake.” Yadin mentions his

broad conclusions regarding his feeling of having found significant evidence for an

earthquake several times. He claims that “[t]he earthquake which destroyed Stratum VI

seems to be the one referred to in the Bible, which occurred during the reign of King

Uzziah (c. 760 B.C.).” In fact, he uses this as a chronological anchor point in order

to date Stratum V to between the earthquake and the destruction by Tiglat-pileser in

732 B.C.E. and in aid of dating the destruction of Stratum VII to the Aramean attack

at the end of the 9th century B.C.E. and thereby dating the well-appointed Stratum VIII

to the time of Ahab in the early-middle of that century.

There are several problems with Yadin’s conclusion that an earthquake is evidenced

by finds in Stratum VI at Tell Hazor and that that earthquake is to be identified

with the one described in the Book of Amos, in the mid-8th century B.C.E.

Some pieces of Yadin’s evidence for an earthquake are not convincing and

his stratigraphic conclusions in Area A, where all of the purported

earthquake evidence was found, have been challenged by Ben-Tor’s excavations.

The items of evidence Yadin found are mainly of two types: leaning or fallen

walls or pillars and fallen ceiling pieces. In total, Yadin describes 7 leaning

or partially fallen walls, 3 leaning columns, collapsed plaster ceilings in 2

buildings, and broken pottery under some of those ceilings.

Regarding the first group of evidence of walls and pillars, Yadin thought that

the reason why no other walls had fallen or were leaning was that these were of the thinner walls.

To some degree, these walls are thinner, but not very significantly. I would also add that one of

the walls that partially collapsed, the west wall of room 113, was freestanding on one end, making

it highly susceptible to tilt from any sort of uneven load. Plus, the description of whole courses

of stones falling together is unintelligible in light of the construction of these walls, made

out of unfinished and partially finished stones of various sizes, held together with mortar.

These are not walls of ashlar masonry which could actually be said to fall in rows. In addition

the evidence of walls or pillars falling in the same direction is not necessarily indicative of

an earthquakes directional force. All of this evidence was found only in Area A, which is at

the eastern end of the upper city.

In terms of the direction of the walls and pillars tilt or collapse, all of the walls were to

the east or southeast, toward the downward slope of that part of the tell. Yadin seems to have

thought it was the eastern end of the previous levels in the upper city, which would have been

constituted of only the upper city’s western half. As noted by Ambraseys, it is most common for

walls to fall in the direction of downward sloping, which is outwards at a major slope or edge

of a tell. This makes it more likely that the tilting of several walls within close proximity

to one another can have occurred due to slower processes, such as water seepage causing leeching

of soils in the particulate, not well compacted ground of a tell. Although it is difficult to

discern in the site reports how much the ground sloped at the time of Stratum VI, it is notable

that in the southeast corner of Building 21a, in room 80a, where the wall and pillars are leaning

southward, the floor is 0.2 m. lower than the floors in rooms 81a and 2a, at 229.55 m. elevation

rather than 229.75 m. (see Figure 4). Nonetheless, we cannot rule out an earthquake as the cause

of the damage to these walls.

For the evidences of ceiling collapse, it is not simple to ascribe them to earthquake damage;

they may be due to abandonment and weakening. It is important for this to have a cataloging of the

ceiling fragments according to size and location in order to distinguish between slow and sudden

collapse, but this is absent in the Hazor reports. However, in Yadin’s favor, it is unclear if

there would have been enough time for slow collapse in Stratum VI according to his chronology of

the stratigraphy. It is also difficult to tell to what extent ceilings actually collapsed as the

reports only contain mention of it in two buildings, whereas elsewhere Yadin implies that there was

more widespread collapse as previously noted. Also, the discovery of broken pottery with ceiling

fragments above it does not lead to the necessary conclusion that the ceiling fragments destroyed the pots.

A curious point is the fact that, in Building 2a, the Stratum V walls were built immediately on top

of the leaning Stratum VI walls with essentially the same plan as the earlier stratum. In addition,

Yadin claims that the material culture of the two strata is very similar if not identical. He concludes

from this that there was a quick rebuilding of this structure (and the others) after the earthquake at a

higher level, with the fallen parts of the structure buried under the floor of the next level so as not

to necessitate the removal of the rubble. Yadin views this as conclusive evidence that an earthquake is

what destroyed the previous stratum, but, even if he is correct that this indicates a quick rebuilding,

an earthquake as the cause of the previous destruction is not the necessary cause.

The biggest evidentiary problem facing Yadin’s proposal is that he does not report any earthquake related

damage in any of the other areas excavated in this stratum, neither in Areas B nor G. The lack of widespread

destruction makes it much less likely that an earthquake was the cause of these damaged walls and fallen ceilings.

Stiros invokes widespread damage as a usual feature of earthquake-related damage and indicates that it is crucial

for identification of an earthquake in archaeological remains.

A further complication to Yadin’s assembled evidence is that his whole analysis of the stratigraphy of Area

A has been challenged by the newer excavations. One of the goals of the renewed excavations was to inspect

Yadin’s stratigraphy in this area. Area heads Greenberg and Bonfil constructed a differing stratigraphy

from Yadin’s. They noted an asymmetry in the ceramic, architectural, and stratigraphic phases as well as

problems with the correlation of strata between the three Areas: A, B, and G. Part of their solution was

to combine Yadin’s Stratum VIII and part of Stratum VII into a single Stratum 5, during which the Pillared

Building and connected storehouse originally functioned. Stratum 4 equates to the rest of Stratum VII. At

that time, Building 2a was initially built, while the Pillared Building was still in use, as opposed to

Yadin’s ascription of it to Stratum VI. Stratum 3 corresponds to Yadin’s Stratum VI and possibly Stratum

2 to Yadin’s Stratum V, although those last results were not clear after the first four seasons of renewed

excavation. This reorganization of the stratigraphy places the damage noted by Yadin to the end of Stratum 4,

Yadin’s Stratum VII, and coterminous with the large Pillared Building and adjacent storehouse going out of use.

This significant change in the layout of the buildings and the change to using smaller buildings in the area

seems to imply that a significant change occurred. But, since no earthquake evidence was found in the other

buildings Yadin ascribed to Stratum VII and since the large building went out of use in favor of smaller ones,

it seems that a period of abandonment leading to a reorganization of the area is more probable than an earthquake.

If so, then Yadin’s argument from the sealing of the floor of the initial stratum in Building 2a after an earthquake

is unappealing. In addition, it would seem that the fallen ceiling pieces and leaning wall and pillars in Building

2a would then be distanced in time from the leaning walls and fallen ceilings in the nearby buildings to its northeast.

In sum, although Yadin’s reasoning and evidence is questionable in several different ways, making it more probable

that it does not substantiate the earthquake mentioned in Amos than that it does, more investigation is necessary

to make solid conclusions. One can hope that the current excavations will include experts trained in the detection

of archaeoseismic evidence, that the excavation design will include emphasis on answering this question, and that

the reports will contain the detail needed to investigate such possibilities.

More recently, William Dever claimed to have discovered evidence for an earthquake in the middle

of the 8th century B.C.E. at Tell Gezer. The focus of his evidence is on the outer wall of the city,

in which he has found cracks through several courses of stones, bends in the wall, and stones fallen

off of it, supposedly with stretches of courses together. Although the arrangement of courses of

stones falling in both directions off of a wall is good evidence for an earthquake, “collapsed,

bulging or outwardly leaning retaining walls are unlikely to be due to earthquake damage alone.”

And, even though the bottom courses of the wall “were set into leveled-out depressions cut directly

into the bedrock,” the outward pressure from the inside ground of the tell could very well have

caused significant displacement of higher stones. Since Dever offers no other evidence than that

of the outer wall at Gezer, our conclusion will have to be open ended until further inspection

of the site and/or its reports are completed.

46 Amos Nur and Hagai Ron, ³And the Walls Came Tumbling Down: Earthquake History in the Holyland,´ in

Archaeoseismology (Fitch Laboratory Occasional Paper 7; Eds. S. Stiros and R. E. Jones; Athens: Institute of

Geology and Mineral Exploration and The British School at Athens, 1996), 75-76; Zvi Ben-Avraham, et al.,

'The Dead Sea Fault and its Effect on Civilization,´ in Perspectives in Modern Seismology

(Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences 105; Ed. Wenzel Friedemann; Berlin: Springer, 2005), 147-69.

47 For historical earthquakes, see the earthquake catalogs cited in Martin R. Degg, ³A Database of Historical Earthquake Activity in the Middle East,´

Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers N. S. 15:3 (1990), 295. For paleoseismic evidence, see Shmuel Marco, Mordechai Stein, and Amotz Agnon,

"Long-term Earthquake Clustering: A 50,000-year Paleoseismic Record in the Dead Sea Graben," Journal of Physical Research

101:B3 (1996), 6179-6191.

48 See chart in Galadini, et al., ³Archaeoseismology,´ 397, figure 1.

49 See Sintubin and Stewart, ³A Logical Methodology for Archaeoseismology,´ 2213-6, and especially the appendix, 2229-30.

50

Sintubin and Stewart, ³A Logical Methodology for Archaeoseismology,´ 2209-30.

51 Ambraseys, “Earthquakes and Archaeology,” 1009-11.

52 See above, n. 49.

53 Galadini, et al., “Archaeoseismology,” 402-3, 404-6.

54 Ambraseys, “Earthquakes and Archaeology,” 1009-11.

55 Complete reports of the first two seasons were published subsequently

in 1958 and 1960 (Yigael Yadin, et al., Hazor I: An Account of the

First Season of Excavations, 1955 [Jerusalem: Magnes, 1958]; Yigael

Yadin, et al., Hazor II: An Account of the Second Season of Excavations,

1956 [Jerusalem: Magnes, 1960]), along with plates from the third and

forth seasons in 1961 (Yigael Yadin, et al., Hazor III-IV: An Account

of the Third and Fourth Season of Excavations, 1957-1958. Vol. 1: Plates

[Jerusalem: Magnes, 1961]). The text of those later reports was published

in 1989 (Yigael Yadin, et al., Hazor III-IV: An Account of the Third and

Fourth Season of Excavations, 1957-1958. Vol. 2: Text [Biblical Archaeology

Society, 1989]). Excavations were continued in 1990 under the direction of

Amnon Ben-Tor, who also published the results of Yadin’s 1968 season in

conjunction with some of the results of his first four seasons (Amnon

Ben-Tor and Robert Bonfil, Hazor V: An Account of the Fifth Season of

Excavations, 1968 [Israel Exploration Society, 1997]).

56 Yigael Yadin, Hazor: The Head of All Those Kingdoms (London: Oxford University Press, 1972).

57 Yigael Yadin, Hazor: The Rediscovery of a Great Citadel of the Bible (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1975).

58 Amnon Ben-Tor, “The Yigael Yadin Excavations at Hazor, 1990-1993:

Aims and Preliminary Results,” in The Archaeology of Israel:

Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present (Journal for the

Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 237; Eds. Neil A.

Silberman and David Small; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1997), 107-27.

59 Yadin, Hazor II, 24, lists damage in four rooms as follows (see Figure 4):

[Room] 78 – The N. wall was leaning to the S., and was partly supported by the

debris that blocked the W. entrance to the room. Next to the wall was a sloping

pile of debris made up of courses of stones; buried beneath it were several vessels.

The earthquake wrought most havoc in this room, and it was the wreckage here that first gave us the clue to the disaster.

[Room] 14a – The W. wall leans sharply to the E., the E. wall less so.

[Room] 113 – The W. wall is cracked down the middle and leans eastwards. The N. wall leans southwards very markedly.

[Room] 21a – The E. wall slants eastwards, and fallen courses of stones covered the street to the E. of the room (28a).

60 It was only partially excavated in the 1956 season, and so later reported

as follows: of the “six well-dressed square stone pillars[, t]hree […] were

found still in situ.” But, “all the walls and pillars [of Building 2a] were

tilted southwards,” so much so “that only their tops could be used, and even

those only as a base for the new foundations” of the buildings of the subsequent

Stratum V. In addition, “[i]n all the rooms, as well as in the western part of the

court, huge blocks of ceiling plaster were found sealed off by the floors of Stratum V”

(Yadin, Hazor: The Head of All Those Kingdoms, 179, 181).

61 Yadin, Hazor: The Head of All Those Kingdoms, 181.

62 Yadin, Hazor: Rediscovery, 151.

63 Yadin, Hazor II, 243

64 Yadin, Hazor: Rediscovery, 153.

65 Geva, Hazor, Israel, 125-31, tables 17, 19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 29, 30.

66 Yadin, Hazor: Rediscovery, 154.

67 Yadin, Hazor II, 24. He continues:

Many walls in this stratum were found bent or cracked; in several places we

found debris of walls lying course on course, just as is found in earthquakes

when the entire wall collapses at once. The direction in which the walls leant

or fell was southerly or easterly, according to the direction in which they ran.

In some cases the upper part of the wall collapsed and the lower part remained

standing but leaning. Leaning walls were used as a foundation for Stratum V when

rebuilding began.

68 Ibid., 24-25. He continues:

Strong walls had therefore stood up to the shock, while others had been only partially wrecked,

even remaining standing in places, albeit at a slant. This partial destruction is seen again

in the levels of the walls that survived from Stratum VI: some were preserved to a height of

2 m., others were totally wrecked.

The damage done was repaired at once and the buildings were rebuilt.

69 Yadin, Hazor: The Head of All Those Kingdoms, 185.

70 Ibid., 181.

71 See Yadin, Hazor: Rediscovery, 151, 157-8.

72 Although the chronology of Iron Age strata of many sites in Israel has

come under question, this seems to not be an issue at Hazor for the levels

beginning exactly with Stratum VII. Israel Finkelstein spearheaded the argument

that the Iron Age levels at Hazor and other sites need to be down-dated to better

correlate with carbon 14 dates from those sites (see Amihai Mazar,

“The Debate over the Chronology of the Iron Age in the Southern Levant,”

in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating: Archaeology, Text, and Science

[Ed. Thomas E. Levy and Thomas Higham; London: Equinox, 2005], 15-30).

But, he leaves Stratum VII at Hazor untouched (Israel Finkelstein,

“Hazor and the North in the Iron Age: A Low Chronology Perspective,”

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 314 [May, 1999]: 57).

73 See above, n. 68.

74 Ambraseys, “Earthquakes and Archaeology,” 1009.

75 Ben-Tor, “The Yigael Yadin Memorial Excavations at Hazor,” 123, notes

“The area’s terrain slopes in all directions with an especially sharp slant toward the east.”

76 Ambraseys, “Earthquakes and Archaeology,” 1010.

77 Ibid. and Stiros, “Identification of Earthquakes from Archaeological Data,” 139, 141.

78 Galadini, et al., “Archaeoseismology,” 402.

79 Seemingly, there would be less time if we follow the Low Chronology,

which shrinks the time spans of Iron Age II strata, but there would be

more if Ben-Tor’s reports are correct and the building complex in which

all of Yadin’s evidence is found was built still during his Stratum VII,

while the Pillared Building still stood. See n. 72.

80 Above, p. 19.

81 Yadin, Hazor: The Head of All Those Kingdoms, 181.

82 Stiros, “Identification of Earthquakes from Archaeological Data,” 145.

83 Ben-Tor, “The Yigael Yadin Memorial Excavations at Hazor,” 110.

84 Ben-Tor, et al., Hazor V, 150; Ben-Tor, “The Yigael Yadin Memorial Excavations at Hazor,” 112-4.

85 Ben-Tor, et al., Hazor V, 123-51, 165.

86 Certainly the Pillared Building itself suffered no damage as

all of its pillars were found in situ and erect.

87 William G. Dever, “A Case Study in Biblical Archaeology:

The Earthquake of Ca. 760 BCE,” Eretz-Israel 23 (1992), 27*-35*.

88 Randall W. Younker, “A Preliminary Report of the 1990 Season at Tel Gezer:

Excavations of the ‘Outer Wall’ and the ‘Solomonic’ Gateway (July 2 to August 10, 1990),”

Andrews University Seminary Studies 29:1 (1991), 28.

89 Galadini, et al., “Archaeoseismology,” 403.

90 Ambraseys, “Earthquakes and Archaeology,” 1010.

91 Younker, “Preliminary Report,” 29.

This paper has investigated the possible biblical and some of the possible archaeological evidence relating to the earthquake in the days of Uzziah mentioned in the Book of Amos. Our conclusions are mixed. Biblical evidence points toward an impactful earthquake. As of yet, the archaeological evidence which has been suggested as indicative of this earthquake by several archaeologists and scholars is largely inconclusive. Further archaeological excavations with this problem in mind, as well as with personnel knowledgeable in archaeoseismological investigation could make significant inroads toward its solution. The biblical evidence is very strong since most scholars recognize the earliest parts of the Book of Amos as belonging to the 8th century B.C.E. Because of that, there is an expectation that corresponding archaeological evidence will be found, but that will not necessarily occur. It is quite possible that no recognizable trace of this earthquake has remained in the archaeological record due to myriad factors. Even if it might exist, the biblical account is so vague regarding the location of actual damages incurred that digs may not be aimed in the correct locations. As such, it remains an open problem.

7. Hazor

Hazor, well known for its imposing mound in northern Israel has stood as the unquestioned paradigm of archaeoseismic evidence ever since Yadin’s publications in the late 1950s and early 1960s.57 Yadin believed he found evidence of earthquake damage within Stratum VI throughout Area A located just west of the well-known six chamber gate. In building 2a, a building with a large court and series of rooms on its northern and western sides with a roof supported on the eastern side by six square stone pillars, all the walls and pillars leaned south.58 Yadin also found “huge blocks” of ceiling plaster sealed off by the floors of Stratum V that were built 1.5 meters above the Stratum VI floors. In Yadin’s view, since the walls of the Stratum VI house were so tilted, only their tops could be used, and this accounted for the 1.5 meter rise in flooring between strata. Building 14a, located just east of 2a and nicknamed “The House of Makhbiram” because of the inscription found inside was excavated with collapsed walls. Also, the building termed "Ya'el's House" was found with objects of daily use beneath the collapsed ceiling as well as southward-leaning walls that were common near the house.59

Decades after Yadin’s excavations from the late 1950’s Amnon Ben-Tor would also follow Yadin’s interpretation.60 In Hazor III-IV, Ben-Tor writes,

Due to the excellent construction of building 2a, we can trace in it the effects of the earthquake which destroyed Stratum VI better than anywhere else in the excavation area. Its strongly-built walls remained standing to a considerable height, but the earthquake is evidenced by their tilt-southwards, particularly that of the three pillars (Pl. XXV, 2). In all the rooms and in the northern part of the courtyard, we came upon great quantities of debris comprising lumps of plaster form the collapsed ceilings (Pl. XXVII, 1, 4), resembling those that we found in storeroom 148 in 1956 (Hazor I, p. 23).61In the renewed excavations led by Amnon Ben-Tor, he also has argued for evidence of seismic destruction. William Dever, through personal observation and communication with Ben-Tor noted, “…in a street and drain in Area A that seemed simply to have split down the centre – difficult to explain by any other hypothesis.”62

Given Hazor’s location near where the presumed epicenter of the quake struck, one would expect more evidence of earthquake damage. At the same time some of the diagnostics used by Yadin must be balanced by our knowledge of the site as well as more advanced archaeoseismic diagnostics. For example, currently, all the evidence that Yadin identified as seismic damage is found in Area A. The area slopes towards the east or southeast, the downward slope of the tel.63 Thus, the well-known pillars that are slanted, slant towards the downward slope of the tel. This does not undercut his assertion that an earthquake caused the slanting but the topography must be accounted for in labeling damage as due to an earthquake. In sum, earthquake evidence at Hazor is expected but it is not as clear or widespread as we would like.

57 Amnon Ben-Tor, “Hazor,” NEAHL 2: 594-606, simply notes that there are “clear signs that this city was destroyed

by the earthquake in the days of Jeroboam II, which is mentioned by Amos.” But he also mentions that, “Indications

of the destruction of stratum VI by earthquake, noted by Yadin, were not identified,” Amnon Ben-Tor, “Hazor,”

NEAHL 5:1769-1776.

58 Yadin, Hazor: the Head, 179-181.

59 In sum, Yadin, Hazor II, 24, lists damage as most striking in the following rooms:

Room 78 – The N. wall was leaning to the S., and was partly supported by the debris that blocked the W. entrance to the room. Next to the wall was a sloping pile of debris made up of courses of stones; buried beneath it were several vessels. The earthquake wrought most havoc in this room, and it was the wreckage here that first gave us the clue to the disaster.60 Shulamit Geva, Hazor, Israel: An Urban Community of the 8th Century B.C.E. (BARIS 543; Oxford: BAR, 1989), lists items buried in several rooms and strongly supports the earthquake theory championed by Yadin.

Room 14a – The W. wall leans sharply to the E., the E. wall less so.

Room 113 – The W. wall is cracked down the middle and leans eastwards. The N. wall leans southwards very markedly.

Room 21a – The E. wall slants eastwards, and fallen courses of stones covered the street to the E. of the room (28a).

61 Amnon Ben-Tor, Hazor III-IV. An Account of the Third and Fourth Seasons of Excavation 1957-1958 (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1989), 41-44.

62 Dever, “A Case-Study,” 28*.

63 This can be seen in picture 2, plate I and on the topographic map, Plate CXCVIII. The entire upper city has an elevation of about 30 feet that runs from the high side on the west and then downward toward the east side

| Period | Age | Site | Damage Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | Hazor | houses (Area A, stratum IV) with tilting walls and a street and drain that were split down the center are indicative of an earthquake (Yadin 1975: 150-151; Dever 1992: 28). |

Excavations by Yigal Yadin at Hazor in the last half of the 1950s uncovered fairly compelling archaeoseismic

evidence on the south side of Area A in Stratum VI

(see, for example, Yadin et. al., 1959,

Yadin et. al., 1960,

Yadin, 1970, and/or

Yadin, 1975). The excavators encountered

tilted and collapsed walls including collapses which preserved the original courses, inclined pillars, and

fallen ceilings with extensive debris from ceiling plaster lying on floors.

Broken jars were found on the floors and some expensive luxury items were found in the debris. Stratum VI is fairly well dated. Pottery

dates it to the 8th century BCE perhaps even the first half of that century (Dever, 1992:28*

and Finkelstein, 1999:65 Table 1).

The overlying Stratum, Stratum V, is terminated by a burned destruction layer which appears to coincide with the

Assyrian destruction of Hazor in 732 BCE. Thus, it appears that Stratum VI contains a seismic destruction layer from the first half of the

8th century BCE which may coincide with one of the Amos Quakes.

Although Dever (1992:28*), relying on personal communication with Amnon Ben-Tor,

reports that more archaeoseismic evidence in Stratum VI was uncovered during renewed excavations in the 1990s -

especially in a street and drain in Area A that seemed simply to have split down the centre — difficult to explain by any other hypothesis

,

Amnon Ben-Tor in Stern et al (2008) reports

that indications of the destruction of stratum VI by earthquake, noted by Yadin, were not identified

.

A number of walls were described as tilting to the south and to the east.

Ben-Menahem (1991) took this as evidence that Hazor was in the near field of seismic energy when the earthquake struck

and estimated that the epicenter was only ~20 km. to the northeast.

According to the report of the excavating archeologists [Yadin et. al., 1959], northern walls were tilted southward, while western walls tilted eastward. Figure 8 shows that these orientations are consistent with the effect of a near field horizontal shear acceleration coming to Hazor from the north east. This is consistent with modern ideas that structures in the near-field of a major earthquake are mostly affected by SH body waves and the fundamental Love mode. ( Ben-Menahem, 1991)While this may be correct, a true archaeoseismic survey was not conducted on the site in order to, for example, make exact measurements of tilting directions and inclinations, look for shifted ashlars, see if there were rotated stones, etc.. The fact that the damage was concentrated on the south side of Area A rather than throughout the entire site casts doubt on Ben-Menahem (1991)'s estimate of a ML = 7.3 earthquake with an epicenter a mere ~20 km. to the NE of the site. An earthquake that large and that close would have probably caused extensive damage throughout the site; not just on the south side of Area A. In addition, as noted by Korzhenkov and Mazor (1999),

areas above a hypo-center do not reveal systematic inclination and collapse patterns, whereas some distance away inclination and collapse have pronounced directional patterns. Thus, while the archaeoseismic evidence does suggest that an earthquake struck the site, shaking would have been moderate rather than severe. This site may be subject to a ridge effect.

Expanded discussions can be found in the References section below. It should be noted that some of the discussions suggest that tilting in Area A may be due to its location on a slope. A site visit by Jefferson Williams in April 2023 suggests that this is not a real possibility. Area A is offset from the part of the mound that slopes. This can be seen from the topographic maps. It is possible, however, that differential subsidence and/or a poor state of pre-existing building integrity contributed to the tilting.

| Effect | Location | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tilted Walls and Pillars, Broken fragments of ceiling plaster | Area A - Building 2a - aka "Ya'el's House

Figure 6b

Figure 6bArea A, plan of Stratum VI as excavated by Yadin. The ‘Annexed Halls’ continue in use also in Stratum VI (Yadin et al. 1960: pls CCII, CCIII; courtesy of The Israel Exploration Society) N arrow added by JW Shochat and Gilboa (2018) |

|

|

| Tilted Pillars | Area A - Building 2a - aka Ya'el's House

Figure 6b

Figure 6bArea A, plan of Stratum VI as excavated by Yadin. The ‘Annexed Halls’ continue in use also in Stratum VI (Yadin et al. 1960: pls CCII, CCIII; courtesy of The Israel Exploration Society) N arrow added by JW Shochat and Gilboa (2018) |

|