Tell es-Safi/Gath

Aerial View of Gath

Aerial View of GathClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Used with permission from Biblewalks.com

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Gat | English | |

| Gath of the Phillistines | English | |

| Gath or Gat or Geth | Hebrew | גַּת |

| Tel Zafit | Hebrew | תל צפית |

| Gimti/Gintu | el-Amarna Letters | |

| Saphitha ? | Greek - Madaba Map | ΣΑΦΙΘΑ |

| Gitta ? | Greek - Madaba Map | |

| Geth | Latin | |

| Tell es-Safi, Tell el-Ṣāfiyya | Arabic | تل الصافي |

| Blanche Garde | French Crusader |

Tel Zafit (Tell es-Safi) is located on the southern bank of Wadi Elah, where it enters the Shephelah (map reference 1359.1237). The mound, 232 m above sea level and about 100 m above the valley bed, dominates the road that passes along the foot of Azekah (Tell Zakariyeh) and leads through Wadi Elah into the mountains. It also guards the main north-south route of the Shephelah that runs through the plain, at the foot of the mound to the west, toward Gezer. On the north and east the mound slopes steeply, revealing white limestone cliffs: to the south, the mound slopes gradually and is connected by a saddle to the range behind it. The mound's summit is crescent shaped and slopes moderately to the south, where the acropolis was located in antiquity.

The identification of the site is disputed. J. L. Porter, in 1887, was the first to identify it as Gath, and this was accepted by many scholars - including F. J. Bliss, the mound's excavator. Another suggestion, also widely accepted at the time, located the biblical city of Libnah here. This suggestion was based (aside from various biblical and other sources) on the Arabic name Tell es-Safi, meaning "the white mound," and on the French Crusader name, Blanche Garde, or "white citadel". The recurrence of the word "white" was taken to be a connection with the biblical name Libnah, which also means white. It was suggested that these three interrelated names had their origin in the white cliffs, which are visible from afar. Two primary sources from the Byzantine period contradict this assumption, however. Eusebius states that in his day there was a village named Ʌoβαvα (Lobana, meaning white) in the vicinity of Eleutheropolis (Beth Guvrin) (Onom. 120, 25). On the Medeba map, on the other hand, there is a place called CΑΦΙΘΑ (Safita), which is identified with Tel Zafit. The mound was therefore already known by the name it bears today, and a settlement called Labana was then situated near Beth Guvrin. White cliffs are also found on the slopes of other mounds in the vicinity. In light of these facts, Z. Kallai returned to the early suggestion of C. W. M. Van de Velde and V. Guerin to search for a place in the vicinity with a name like Mizpeh, which could have undergone a change to Safita. W. F. Albright suggested that Tel Zafit should be equated with biblical Makkedah (Jos. 10:10). There have been other suggestions as well, but current archaeological research tends to prefer the original proposal identifying it with Gath.

In 1899, excavations were conducted on the mound sponsored by the British Palestine Exploration Fund, under the direction of Bliss, with the assistance of R. A. S. Macalister. The expedition originally intended to excavate mainly at Tel Zafit. However, the license granted by the Ottoman authorities permitted them to excavate an area of 10 sq km, so the expedition also excavated the nearby mounds of Tell Zakariya (Azekah), Tell Judeideh, and Tell Sandahanna (Mareshah). Tel Zafit was excavated for two seasons in 1899. The results of the excavations were published in a comprehensive report in 1902. The account was written by Bliss, and the summary of the findings was compiled by Bliss and Macalister.

When the excavators arrived at the mound, they realized that the areas suitable for excavation were very limited. In the southern part of the summit, the natural place for the acropolis, there was a holy maqam, surrounded by a cemetery that it was also impossible to excavate. To the north, on the main part of the mound, were the houses of the Arab village and, behind them on the east, another cemetery that stretched over the remainder of the summit. The excavations were therefore confined to small, noncontiguous sections that were part of five main areas:

- area A, a narrow strip across the width of the summit between the maqam and the village

- area B, a second section in the same place, east of area A, toward the center of the mound

- area C, the city wall~traced on the south and west slopes

- area D, the east side of the mound

- area E, the remains of the Crusader fortress in the southern cemetery

Following the conclusion of the excavations by F. J. Bliss of the British Palestine Exploration Fund, little archaeological exploration was conducted at Tel Ẓafit for close to a century. Only limited surveys and illicit excavations had taken place, despite the site’s apparent importance in ancient times and the ongoing controversy over its identification. Since 1996, the Tell es-Ṣafi/Gath Archaeological Project, headed by A. M. Maier of the Institute of Archaeology of Bar-Ilan University, has been conducting a long-term research project at the site. In 1996–2002, seven seasons of research and excavation, the first phase of this project, took place.

A preparatory season in 1996 included a comprehensive surface survey of the site, aerial photography, photogrammetric mapping, and ground penetrating radar. The main objectives of this season were to determine the periods represented at the site, best ascertain the size of the site in different periods, and determine whether it would be possible to easily access the pre-Classical period strata on the site.

The results of the initial season demonstrated that the site had been settled virtually continuously from the Chalcolithic period until recent times. The size of the site was determined to be 100–125 a., much larger than previously thought, and large portions of it were shown to be not covered by Classical and post-Classical period remains, making it easier to arrive at earlier Bronze and Iron Age layers. The survey also enabled a more explicit periodization of the site, with episodes of intense settlement shown to have occurred in the Early Bronze Age II–III, Late Bronze Age, Iron Age I–IIA, Persian period, and Crusader period. Although in subsequent seasons the Crusader remains could not be excavated, an accurate plan of the fortress was made during the survey and a Crusader period quarry was discovered on the northwestern slope of the tell. Finally, aerial photography reconnaissance revealed the existence of a unique man-made feature surrounding the tell, most probably the remains of a siege trench.

The actual excavations commenced in a trial excavation conducted in 1997. Based on the results of the 1996 survey, it was decided that the primary excavation area (area A) would be on the eastern appendage of the tell—a large flat terrace where few post-Iron Age remains were revealed in the survey. Indeed, Iron Age remains were encountered immediately upon commencing excavations. The Bronze and Iron Age levels in this area would prove to be in a very good state of preservation.

The primary excavations in the 1998–2002 seasons have been conducted in the same general area. Area A was subsequently expanded, and area E was opened on an adjacent lower terrace to the east. Several investigations were carried out surrounding the tell (areas C1–C6) in an attempt to study the man-made feature mentioned above; area C6 was of particular interest in this regard. During excavations, intensive surface survey of the tell and its vicinity continued, and geomorphological soundings were conducted on and around the tell.

- Fig. 1 Map with location of

Tell es-Sâfi Gath from Schniedewind (1998)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Topography of southern coast and Judaean Shephelah

Schniedewind (1998) - Fig. 1.33 Aerial View of Upper

and Lower cities of Gath from Maeir (2020)

Figure 1.33

Figure 1.33

Aerial view, looking west, of Tell es-Safi/Gath

- the Upper City

- the Lower City

Maeir (2020) - Tell es-Sâfi Gath in Google Earth

- Tell es-Sâfi Gath on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 5.1 Aerial photo of Area F

and surroundings from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 8 Aerial View of Tell es-Sâfi Gath

and environs from Ackerman et. al. (2005)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Aerial View of Tell es-Sâfi Gath

Ackerman et. al. (2005) - Aerial View of Gath from

BibleWalks.com

Aerial View of Gath

Aerial View of Gath

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Used with permission from Biblewalks.com

- Fig. 1.33 Aerial View of Upper

and Lower cities of Gath from Maeir (2020)

Figure 1.33

Figure 1.33

Aerial view, looking west, of Tell es-Safi/Gath

- the Upper City

- the Lower City

Maeir (2020) - Fig. 4 Plan of Tell es-Sâfi Gath

with location of the various excavation areas from Maeir (2017)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Plan of Tell es-Sâfi/Gath with location of the various excavation areas.

Maeir (2017) - Fig. 1 Bliss' (1899) Original plan

of Tell es-Safi from Avissar Lewis (2015)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Original plan of Tell es-Safi

(After Bliss 1899,188, reproduced in Avissar and Maeir 2012, 112, fig. 2B.2)

Avissar Lewis (2015)

- Fig. 1.33 Aerial View of Upper

and Lower cities of Gath from Maeir (2020)

Figure 1.33

Figure 1.33

Aerial view, looking west, of Tell es-Safi/Gath

- the Upper City

- the Lower City

Maeir (2020) - Fig. 4 Plan of Tell es-Sâfi Gath

with location of the various excavation areas from Maeir (2017)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Plan of Tell es-Sâfi/Gath with location of the various excavation areas.

Maeir (2017) - Fig. 1 Bliss' (1899) Original plan

of Tell es-Safi from Avissar Lewis (2015)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Original plan of Tell es-Safi

(After Bliss 1899,188, reproduced in Avissar and Maeir 2012, 112, fig. 2B.2)

Avissar Lewis (2015)

- Fig. 5.2 Plan of Area F-Upper

and F-Lower from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2

Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.1 Aerial photo of Area F

and surroundings from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

- Fig. 5.2 Plan of Area F-Upper

and F-Lower from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2

Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.1 Aerial photo of Area F

and surroundings from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

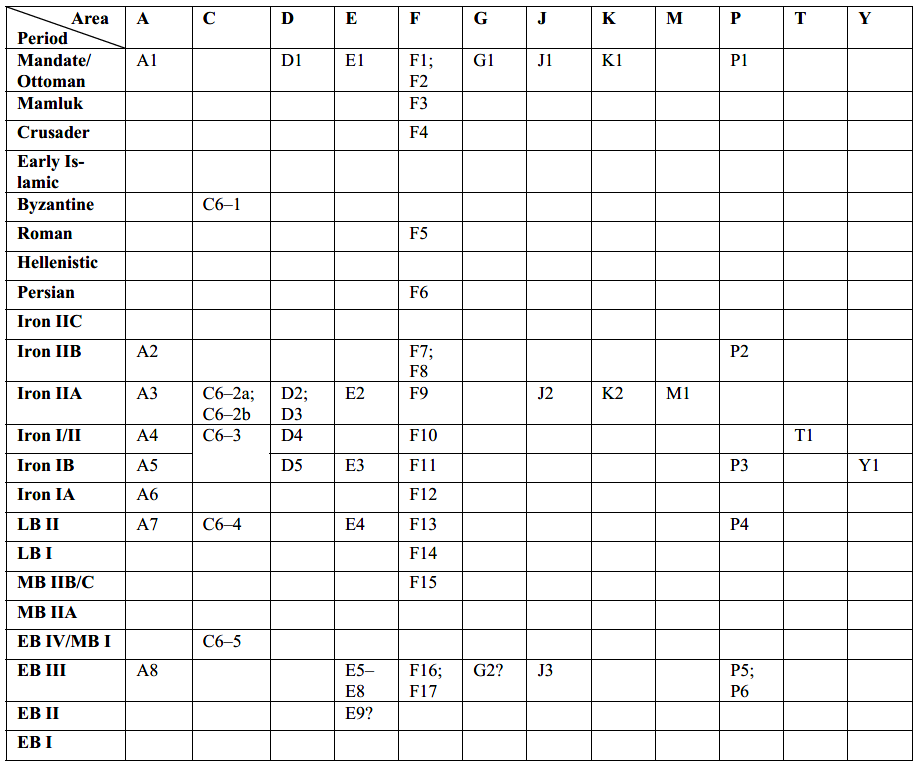

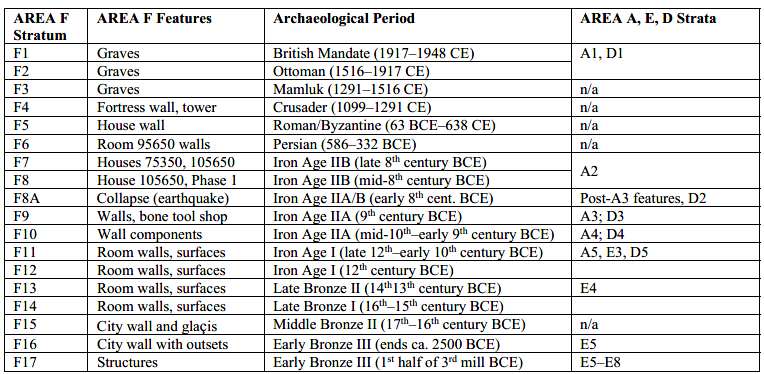

- from Maeir (2020)

Table 1.1

Table 1.1Comparative stratigraphy and dating of the various excavation areas.

Maeir (2020)

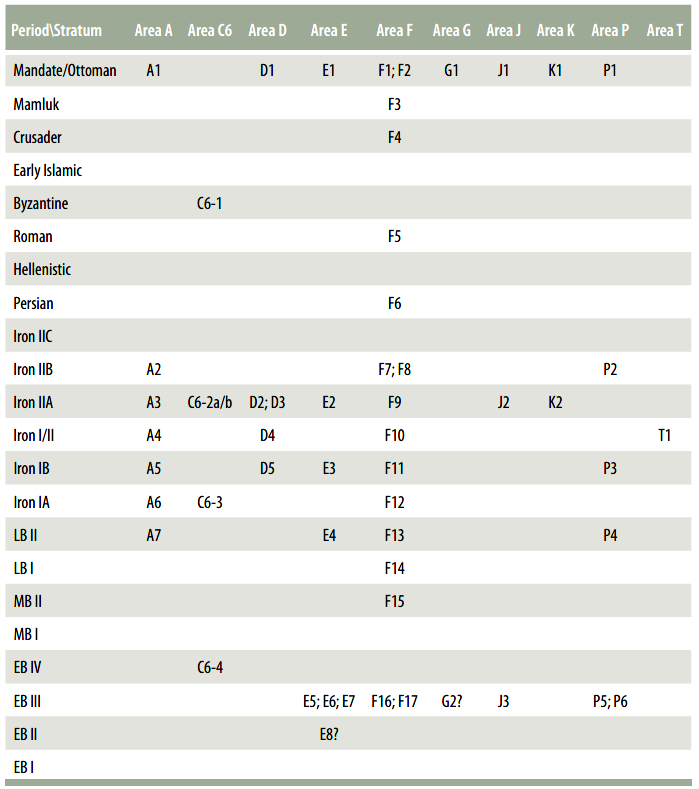

- from Maeir (2017)

Figure 5

Figure 5Comparative stratigraphic table of the excavations areas at Tell es-Sâfi Gath.

Maeir (2017)

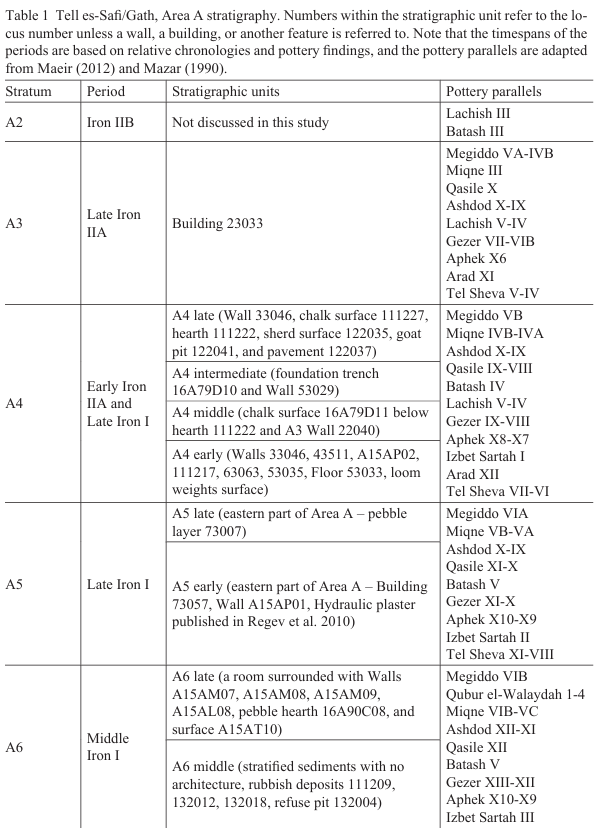

- from Aren M. Maeir in Stern et al (2008 v. 5)

- preliminary stratigraphy kept as a reference for earlier publications

Preliminary Stratigraphy of Tel Zafit

Preliminary Stratigraphy of Tel Zafit

Stern et al (2008 v. 5)

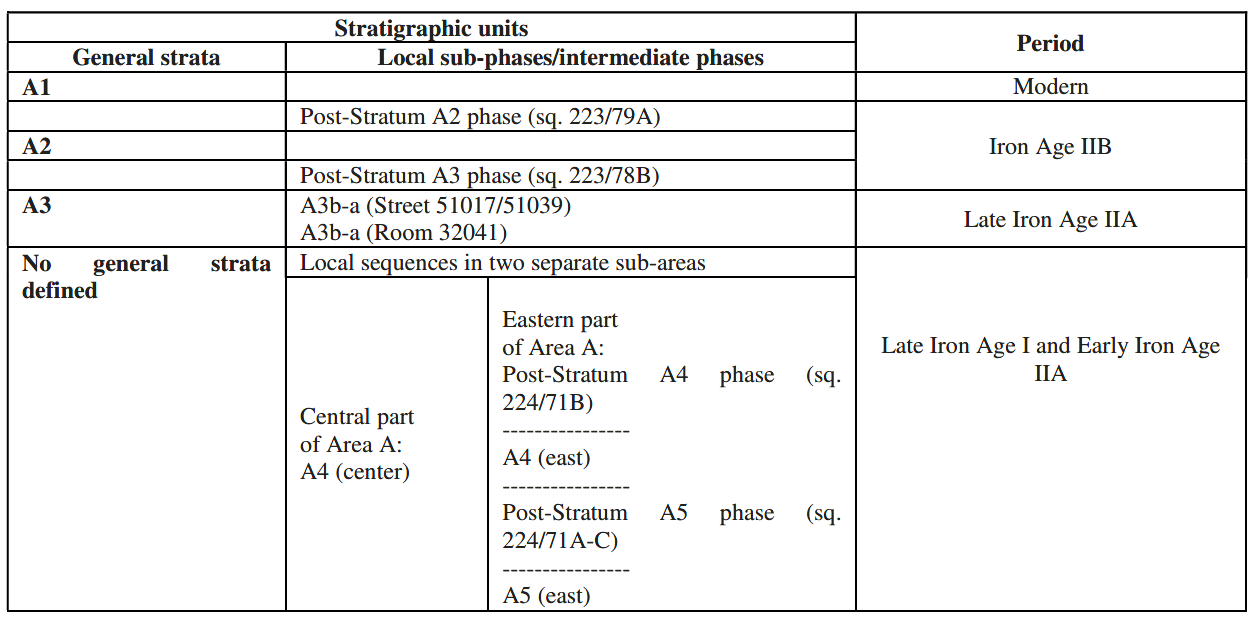

Table 5.1

Table 5.1Stratigraphy of Area F as of the 2016 Season.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

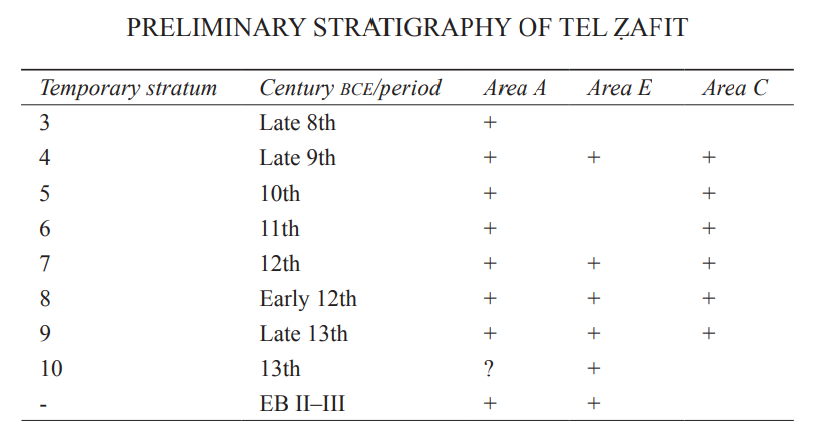

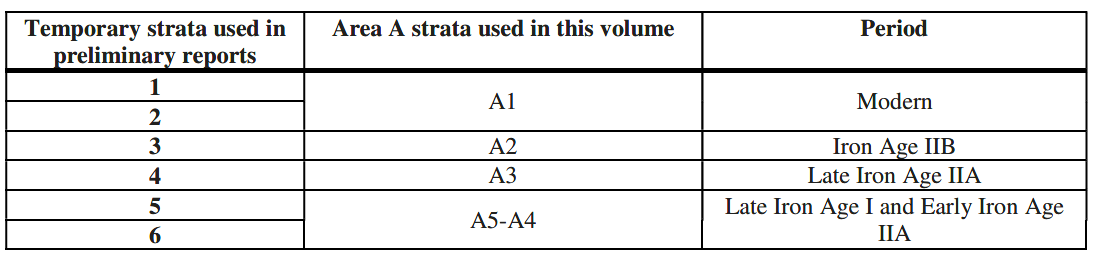

Table 9.1

Table 9.1Stratigraphy of Area A.

Zuckerman and Maeir (2012)

Table 9.2

Table 9.2Summary of the Area A stratigraphy described in this chapter.

Zuckerman and Maeir (2012)

- Figure 1

View of Area F Square 18D with collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake from Chadwick and Maeir (2018:48)

Figure 1

Figure 1

View east toward Area F Square 18D where a low cut section of 18C reveals collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake atop Stratum F8 Judahite house surface.

Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2008.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 2

Section drawing of the low cut section in Area F Square 18C showing collapsed bricks from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Section drawing of the low cut section in Area F Square 18C showing Philistine wall W95613 (Stratum F9) and the bricks (106507) which slid northward from the wall and collapsed during the Stratum F8A earthquake. The Philistine destruction debris (105613) and decades of natural erosion (105611) lie beneath the collapse. Above the collapse is the thinner layer of post-earthquake erosion deposits (105608), covered over by the Stratum F8 fill (105604) and surface (105616) held in place by Judahite retaining wall W85204.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 3

Section west view in Area F Square 17D showing collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake. from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Section west view in Area F Square 17D, showing collapsed bricks (left) of the Stratum F8A earthquake. The collapse was cut by a foundation trench (center) for the Crusader terrace wall (right) of Stratum F4. A Stratum F8 surface, marked by a string, sat just atop the earthquake collapse.

Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2012.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 4

Section east/south view in Area F Square 17C, showing collapsed bricks from the Stratum F8A earthquake from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Section east/south view in Area F Square 17C, showing collapsed bricks and their plaster coatings from the Stratum F8A earthquake. Strata F8/F7 banked up and over the collapsed bricks in the area outside the photo (bottom).

Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2010.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 5

Plan of Stratum F8 Judahite House 105650, erected ca. 750 B.C.E. from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Plan of Stratum F8 Judahite House 105650, erected ca. 750 B.C.E. The remains were only partially recovered due to a large Crusader fortress wall that obliterated the Iron Age remains in the squares south of 18C and 18D. Note the kitchen/bakery area north of the house, including milling station 95203 and cooking hearth 95207.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 6

Plan of Stratum F7 Judahite House 75350 (left), erected ca. 710 B.C.E., and House 105650 from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Plan of Stratum F7 Judahite House 75350 (left), erected ca. 710 B.C.E., and House 105650 in its altered architectural form of Stratum F7 (right). The remains of House 75350 were obliterated by a Crusader terrace wall in the north half of Square 17D. These two four-room style houses were destroyed in the 701 B.C.E. Assyrian campaign against Judah.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) uncovered collapsed walls of what was a then abandoned domestic dwelling in Area F. Brick collapses were all found to be sloping northward

having shifted violently and simultaneously north off their stone foundations.They added that

in some cases the lower courses of brick wall superstructures were still intact, and in one instance (figs. 1 and 2) the flat course lines of a wall showed where its second course had sheared cleanly away from its foundation course, lying slanted over a meter north of its original line.They report that

consulting engineers Oded Rabinovitch (The Technion, Israel Institute of Technology) and Amos Shiran estimated it would have taken 1 g-force of energy to move the walls off their foundations in this manner.This equates to a local Intensity of ~IX using the equation of Wald et. al. (1999) (see Calculator below).

A bit below the collapse layer was Stratum F9 - dated as Iron IIA and interpreted as reflecting Philistine occupation. Above this layer

two successive debris layers were found: a layer of destruction debris from the attack of Hazael (r. 842-796 BCE)'s Aramean forces, and atop that another layer of eroded brick detritus, winter rain-wash, and wind-blown soilswhich had

all accumulated as the abandoned houses decayed over several decades.Collapse Layer F8A was found above this detritus and was overlain by a

much thinner layer of winter rain-wash and wind-blown soilwhich in turn was covered by Judahite structures dated by ceramics to the 8th century BCE and which were probably built

as early as the mid-eighth century B.C.E.and were designated as Stratum 8 which

was discerned across the entire area.Because the Judahites buried the F8A

earthquake collapses under new terraces and fills in Area F, the chronology of seismic destruction was preserved enabling the excavators to supply a confident date of the early to middle part of the 8th century BCE for this seismic shaking in Stratum F8A.

In addition to the collapsed wall in Area F, Chadwick and Maeir (2018) report that

walls collapsed by the earthquakewere also found in

in Area A, on the flatter terrain of Gath's lower east side, and in Area D of the northern lower city.

| Variable | Input | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| g | Peak Horizontal Ground Acceleration | ||

| Variable | Output - Site Effect not considered | Units | Notes |

| unitless | Conversion from PGA to Intensity using Wald et al (1999) |

- Figure 1

View of Area F Square 18D with collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake from Chadwick and Maeir (2018:48)

Figure 1

Figure 1

View east toward Area F Square 18D where a low cut section of 18C reveals collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake atop Stratum F8 Judahite house surface.

Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2008.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 2

Section drawing of the low cut section in Area F Square 18C showing collapsed bricks from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Section drawing of the low cut section in Area F Square 18C showing Philistine wall W95613 (Stratum F9) and the bricks (106507) which slid northward from the wall and collapsed during the Stratum F8A earthquake. The Philistine destruction debris (105613) and decades of natural erosion (105611) lie beneath the collapse. Above the collapse is the thinner layer of post-earthquake erosion deposits (105608), covered over by the Stratum F8 fill (105604) and surface (105616) held in place by Judahite retaining wall W85204.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 3

Section west view in Area F Square 17D showing collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake. from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Section west view in Area F Square 17D, showing collapsed bricks (left) of the Stratum F8A earthquake. The collapse was cut by a foundation trench (center) for the Crusader terrace wall (right) of Stratum F4. A Stratum F8 surface, marked by a string, sat just atop the earthquake collapse.

Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2012.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 4

Section east/south view in Area F Square 17C, showing collapsed bricks from the Stratum F8A earthquake from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Section east/south view in Area F Square 17C, showing collapsed bricks and their plaster coatings from the Stratum F8A earthquake. Strata F8/F7 banked up and over the collapsed bricks in the area outside the photo (bottom).

Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2010.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 5

Plan of Stratum F8 Judahite House 105650, erected ca. 750 B.C.E. from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Plan of Stratum F8 Judahite House 105650, erected ca. 750 B.C.E. The remains were only partially recovered due to a large Crusader fortress wall that obliterated the Iron Age remains in the squares south of 18C and 18D. Note the kitchen/bakery area north of the house, including milling station 95203 and cooking hearth 95207.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018) - Figure 6

Plan of Stratum F7 Judahite House 75350 (left), erected ca. 710 B.C.E., and House 105650 from Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Plan of Stratum F7 Judahite House 75350 (left), erected ca. 710 B.C.E., and House 105650 in its altered architectural form of Stratum F7 (right). The remains of House 75350 were obliterated by a Crusader terrace wall in the north half of Square 17D. These two four-room style houses were destroyed in the 701 B.C.E. Assyrian campaign against Judah.

Chadwick and Maeir (2018)

Chadwick and Maeir (2018:48) described mid 8th century BCE earthquake evidence discovered at Tel es-Safi/Gath

The earthquake was first identified in Area F, on the upper west side of the city, during the 2008 excavation season (fig. 1). Because this was a residential area built upon a complex system of terraces, the collapsed brick walls of the Philistine ghost town were particularly identifiable where they fell over terrace lines. In every square of Area F where Iron II remains were recovered, evidence of the earthquake was present (figs. 1-4). After the discoveries in Area F, walls collapsed by the earthquake were subsequently able to be identified in Area A, on the flatter terrain of Gath's lower east side, and in Area D of the northern lower city. But in Area F we actually gave the collective earthquake collapses a specific stratigraphic designation: Stratum F8A. This identified the earthquake as a separate event in time between two occupational phases we had already discerned and tagged: the terminal Iron IIA Philistine layer (Stratum F9) and the initial Iron IIB Judahite layer (Stratum F8).Chadwick and Maeir (2018:48-50) discussed the stratigraphy as follows:

Earthquake StratigraphyChadwick and Maeir (2018:50-53) discussed the archaeology as follows:

The stratigraphic sequence of the recovered remains in Area F told their own story (fig. 2). Atop the terminal Iron IIA Philistine surfaces of Stratum F9, two successive debris layers were found: a layer of destruction debris from the attack of Hazael's Aramean forces (fig. 2, 105613), and atop that another layer of eroded brick detritus, winter rain-wash, and wind-blown soils were found (fig. 2, 105611), which had all accumulated as the abandoned houses decayed over several decades. On top of the erosion layers the brick collapses were found (fig. 2, 105607), all sloping northward, having shifted violently and simultaneously north off their stone foundations. In some cases the lower courses of brick wall superstructures were still intact, and in one instance (figs. 1 and 2) the flat course lines of a wall showed where its second course had sheared cleanly away from its foundation course, lying slanted over a meter north of its original line. Consulting engineers Oded Rabinovitch (The Technion, Israel Institute of Technology) and Amos Shiran estimated it would have taken 1 g-force of energy to move the walls off their foundations in this manner, and our project seismologist, Amotz Agnon (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), judged that this amount of force would indicate an earthquake of factor 8 on the Richter scale (Chadwick and Maeir, forthcoming; Maeir 2012: 49). This compares closely to the factor 7.8 to 8.2 estimate of Austin et al. 2000 for the event, which would make it the most powerful quake known in the region's ancient geologic history (p. 667).

On top of the brick collapses of the earthquake (Stratum F8A) was found another much thinner layer of winter rain-wash and wind-blown soil (fig. 2, 105608), accumulated during the apparently much shorter period between the earthquake itself and the building of the Judahite structures, which probably occurred as early as the mid-eighth century B.C.E. The new Judahite building phase, Stratum F8, was discerned across the entire area. Remains of two different four-room houses and other structures were unearthed. To prepare for construction on the upper west side of the city, the incoming Judahites built new terrace walls (fig. 2, 85204) around collapsed Philistine ruins, deposited fills (fig. 2, 105604) inside them over the piles of broken brick and other debris, and flattened the fills to prepare new surfaces (fig. 2, 105616) atop which they built their houses. The Judahites' decision to bury the earthquake collapses under new terraces and fills in Area F, rather than level them out and simply build directly atop them, provided excellent preservation of the sequence of events before and after the quake. In many of our excavated sections, the earthquake debris was neatly sandwiched between the ninth century B.C.E. Philistine layers and the eighth century B.C.E. Judahite layers (figs. 1 and 2).

Judahite Gath's Household Archaeology

The household archaeology of Area F at Gath has given us a significant initial understanding of living conditions at Judahite Gath, and also a better understanding of the site's complicated ancient political history. Two different four-room houses were partially recovered by excavations in the area, and numbered as House 75350 and House 105650. These houses were only partly recovered because the south end of House 105605 was obliterated by the deep foundation trench of an twelfth century C.E. Crusader fortress wall (fig. 3), and the north end of House 75350 was removed when a Crusader terrace wall was constructed parallel to the fortress. But the Crusaders also deposited a deep fill between their medieval fortress and terrace walls, creating a sloped moat-revetment that angled upward to the fortress wall, and that also preserved the surviving Iron Age remains in an 8 m-wide alleyway throughout the length of Area F. Thus, where not disturbed by medieval intrusions, the Philistine, earthquake, and Judahite layers were found in quite pristine condition.

There were actually two distinct Judahite occupation layers discerned in Area F, designated as Stratum F8 (fig. 5) and Stratum F7 (fig. 6). Both of these yielded ceramics typical of the eighth century B.C.E. Judahite horizon, comparable to those of Lachish Level III (Zimhoni 2004), including fragments of Iron IIB "torpedo" storage jars, red-slipped wheel-burnished kraters and bowls, typical Iron IIB cooking pots, small black-burnished juglets, and lightly footed oil lamps. A LMLK-stamped handle was also found on surface just outside the Area F excavation area. Stratum F8 was the earlier Judahite phase, dating to a chronological window beginning perhaps as early as 750 B.C.E., when King Uzziah took control1 of Gath and "brake down" its wall (see 2 Chr 26:6). In the lower part of Area F the remains of the city wall, which had surrounded Gath's summit from MB II until Hazael's siege, were broken up and reused by the Judahites. The wall's brick superstructure, which had largely collapsed in the earthquake, was scraped away and stones from the wall's massive foundation were robbed for use in building the new Judahite houses. Even the hardened yellow kurkar sand of the old MB II glacis beneath the city wall was broken up and crushed again into sand, then formed into hardened yellow bricks for use in new Judahite terrace walls. The first phase of House 105650 (fig. 5) belongs to this period. It featured pillar bases in its north long room and its central long-room court. These presumably supported a pillars and floor beams for a second-story wide room at the structure's east end.

The Kitchen/Bakery

On the north side of the house, below its terrace wall, a kitchen and bakery area was found (figs. 5, 7). It featured several installations for ceramic vessel storage as well as a large millstone station and rectangular hearth (see Gur-Arieh, this issue) which extended 1.5 m out from the terrace wall. The milling station sported a heavy, well-carved basalt saddle quern, some 70 cm long and 35 cm wide, with a thick ridge at its upper end. Two hand-held basalt upper grinders, a 15 cm-long one-hander and a 40 cm-long two-hander, were found lying parallel to the quern on either side (fig. 7). A large seven-handled barrel pithos, nearly a meter in diameter, and likely used to hold grain, was found just next to the grinding station in shattered pieces. An intact dipper juglet was found immediately beside it, bringing to mind the biblical image of "the barrel of meal" and "the cruse of oil" (see 1 Kgs 17:14). Numerous other vessels were found in the kitchen, including a LMLK-style storage jar (without seal), other storage jars and hole-mouth jars, platters, a Judahite black-burnished juglet, and what was probably a thin, stone baking tray. Inside the hearth were compacted layers of ash, and its stones were burn-darkened on their interior edges.

Although its pottery vessels were found broken, the kitchen showed no other signs of violent destruction. In fact, it was still neatly ordered; the milling station had been left with its hand-held grinders lying neatly in place following their last usage (fig. 7). The scene seemed to be one of sudden and immediate abandonment. Later, at the outset of the subsequent Stratum F7 phase, the kitchen vessels of Stratum F8 were deliberately broken and the whole kitchen buried under 50 cm of brown sediment, which covered the hearth, the milling station, and all the associated vessels. In Stratum F7 the area seems again to have been used for some type of food preparation, but on a smaller scale, with only a single installation.

The interior of House 105650 also seems to have been abandoned for a short time at the phase end of Stratum F8. Its domestic surfaces yielded only small Iron IIB sherds, but no large fragments of broken pottery or other destruction evidence, and those surfaces were deliberately covered over with a 20 cm layer of brown soil to produce new surfaces for the house's Stratum F7 usage. The central court pillar base of Stratum F8 was completely buried, and a stone-ringed hearth was built atop it in the Stratum F7 phase. This indicates that the house no longer required the pillar as an upper floor support. Another pillar base in the north long room was incorporated into a stone floor pavement. The burial of the earlier kitchen, and the architectural reconfiguration of the house itself, were evidence enough to posit two distinct strata of the Judahite settlement in this house and the surrounding area, rather than merely two phases of a single settlement. Another reason was the building of an additional house in the empty yard directly to the west (fig. 5).Footnotes1. Due to the late composition date for the Chronicles account, the excavators have previously held that the Judahite settlement at Gath probably began during the reign of King Hezekiah, sometime after 715 B.C.E., but no earlier than the reign of his father King Ahaz, which began ca. 735 B.C.E. (Maeir 2012: 51), even though the biblical reference in 2 Chr 26:6 alludes to King Uzziah (Azariah in 2 Kgs), who reigned ca. 786-742 B.C.E., as having conquered the area. But there is also good reason to believe that the Chronicles account of this era "has given more faithful details from the original Chronicles of the Kings of Judah" than did the Deuteronomist (Rainey and Notley 2006: 214). And the relatively thin layer of wind-blown and winter-wash soil atop the earthquake collapses in Area F at Gath suggests that not more than a decade passed after the ca. 760 B.C.E. earthquake before the filling actions of the Judahites began to take place. This would place the origin of the Judahite town at Gath closer to 750 than 735 or 715 B.C.E. (Chadwick and Maeir 2012: 512).

- Fig. 5.1

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.2

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2

Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.3

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3

Brick Collapse 85309 in Square 18C, view to south (2005 season).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.4

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4

Brick Collapse 115607 seen in the eastern section of Square 18C (2008 season).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.5

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.5

Diagram of Brick Collapse 115607 in Square 18C, eastern section (2008).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.6

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6

Brick Collapse 115607 seen in the section line of Squares 18C and 18D (2009 season).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.7

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.7

Brick Collapse 115607, Square 18D, 25 cm east of the line of Squares 18C/18D (2010 season).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.8

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.8

Brick Collapse 115607 in Square 18C, excavation exposure (2010 season).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.9

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.9

Figure 5.9

Brick Collapse 135903 in the southeast corner of Square 17C (2010 season).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.10

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.10

Figure 5.10

Brick Collapse 135903 (155403) in the southwest corner of Square 17D (2012 season).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.11

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.11

Figure 5.11

Plan of House 105650, initial phase, Stratum F8.

Chadwick and Maeir (2020) - Fig. 5.12

from Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.12

Figure 5.12

House 105650, with surface partially excavated to reveal Collapse 115607 (2008 season).

Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

STRATUM F8A: THE COLLAPSE OF ABANDONED IRON AGE IIA STRUCTURES

During the 2005 season, a 1.5 m square sounding was excavated beneath the Stratum F7 surface (75316) of the northeast room of House 75350 in Square 18C (see Stratum F7 below). Because the designations of Strata F8 and F9 had already been assigned to architectural strata, prior to the discernment and understanding of the earthquake and collapse evidence, the several related brick collapses were collectively designated as a separate stratum, of non-human origin, between F9 and F8 — namely Stratum F8A.

Beneath the thin, ephemeral "open area" surface of Stratum F8 (see Stratum F8 below), a mass of collapsed mud bricks (85309) was encountered, nearly 70 cm deep (see Fig. 5.3). The bricks were brownish-red in color, and seem to have been low-fired, since they were largely intact and showed no signs of erosion or degradation due to weather. The bricks were lying in a disarticulated pile, having collapsed in a way which left them all pointing in all different directions. Corners of some of the bricks had been broken off in the collapse, leaving clean, angular edges at the break points. Greyish-brown wind-blown sediment had accumulated between the bricks, filling in the irregularly shaped gaps between them.

As Squares 18C and 17D were excavated down to Iron Age IIA levels during the 2006 season, a 3 m long section of this brick collapse was dug away, revealing the Stratum F9 (=A3) destruction layer beneath it. The destruction debris included the remains of a bone tool workshop destroyed in the 9th century BCE Aramean attack on Gath. Stratum F9 will not be discussed in this chapter, but will be treated in a subsequent volume (see Horwitz et al. 2006; Maeir et al. 2009, for a discussion on the bone tool workshop; for a discussion on the nature of the 9th century BCE destruction of Tell es-Safi/Gath and its attribution to the Aramaeans, see, e.g., Maeir 2012). The collapsed bricks that were removed had fallen northward from their original position atop a Stratum F9 wall socle (95315). The general upper level of the brick collapse in the western part of Square 18C was 202.90, and the general lower level was 202.20 masl.

Another small area of brick collapse was excavated in 2006 in the eastern part of Square 18C, to the east of Wall 95309, where the surface existed on a higher terrace (height 202.80 masl). The shape of the brick collapse on the upper terrace, sloping from south to north, was evident in the eastern section of the square. In 2006, that eastern section was cut a full meter west of the grid line between Squares 18C and 18D in order to preserve a medieval grave for proper excavation.

The nature and dynamic of the brick collapse, and the attribution of the collapse to an earthquake, became understood during the 2008 season. The eastern section of Square 18C was cut back to the designated balk line, 25 cm west of the grid line between Squares 18C and 18D (Fig. 5.4). The specific goal in this action was to explore the nature of the brick collapse on this line. A complicated series of superimposed layers was encountered. The layer of destruction debris (115613) from the Aramean destruction of late Iron Age IIA Gath (Stratum F9 = A3) was found at a general level of 202.80 masl. This debris included ash, debris of chalk plaster (degraded and fallen exterior wall plaster), and ceramic sherds, the latest of which date to the Iron Age IIA. Above this debris was a thin layer of soft, clean sediment (115611), representing natural wind-blown deposits and eroded sediment from winter rains, which had settled over the destruction remains. Directly above this were the collapsed bricks (115607), which had been first noticed in the above-mentioned section in 2006. These bricks were sitting in a disarticulated pile, oriented in all different directions, and wind-blown sediment had filled in the irregular gaps between them. The brick pile was sloped, descending in height irregularly from south to north. The bricks had fallen from a 0.90 m wide wall socle (95316). When the section was cleanly and completely cut, it was noted that the south side of the collapse featured a straight line of bricks that had adhered to one another from when they were sitting upright on the wall socle. This straight line represented the interior face of the brick wall (95316) when it was still standing. The brick line, originally vertical, was now pointing upward diagonally toward the north. Its bottom level was located 1.25 m north of its original position (the south line of Wall 95316), suggesting that the brick superstructure of the wall had shifted suddenly northward during an earthquake which collapsed the bricks. In the section, it was discernible that a single course of bricks had remained atop the wall socle (95316), suggesting that the brick superstructure which moved north and collapsed was dislodged from the wall above the first brick course, having slid suddenly northward from that master course. The socle of Wall 95316 remained completely intact, and there was no evidence of rutting, guttering, or any type of water erosion or other natural erosion or damage to the base of the wall that could have caused the collapse.

During the 2009 season, the eastern section of Square 18C was cut 25 cm back (eastward) from the designated balk line to the actual grid line between Squares 18C and 18D, in an effort to expose a different section of Brick Collapse 115607. The result was a view that showed fallen bricks in different orientations than the 2008 section (Fig. 5.6), demonstrating that the brick collapse was indeed a disarticulated pile with an undulating shape.

In 2010, another 25 cm cut of this eastern section was undertaken, which moved the section face into Square 18D itself (25 cm east of the grid line), providing yet another glimpse of Brick Collapse 115607 (Fig. 5.7). Again, the orientation of the bricks was different, demonstrating the undulating dynamic of the collapse.

A 50 cm high segment of the brick collapse, measuring 50 cm (west to east) by 2.5 meters (south to north), was excavated in three dimensions (rather than as a mere section) between Wall 95316 on the south and Terrace Wall 85204 on the north, removing the layers of Fill 115604 and Natural Deposit 115608, exposing the tops and sides of collapsed bricks. The result was a remarkable view of some of the collapsed bricks in a three-dimensional exposure (Fig. 5.8). The top of one entire brick was successfully exposed, allowing it to be measured for length and width. Its dimensions were 54 x 38 cm, and its thickness was approximately 12 cm. The three-dimensional excavation of these bricks revealed that their top exposed edges had suffered some degree of erosion, probably from winter rains in years between the collapse event and the natural deposit which covered them over. A small basin carved of white chalk (B1356058) was found sitting atop the brick collapse, just north of the most complete brick excavated. The basin may have been sitting in a niche or on a shelf of the superstructure of Wall 95316 at the time the wall collapsed.

An initial professional assessment of the excavated evidence of the brick collapse in Squares 17D, 18C, and 18D as being related to a seismic event was given by three specialists who visited Area F during the 2010 season. These were Prof. Amotz Agnon, a seismologist from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Prof. Oded Rabinovitch, a structural engineer from the Technion, Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, and Amos Shiran, an independent engineer. Rabinovitch posited that the energy necessary to move a brick superstructure (of the size commensurate to the socle of Wall 95316) off its foundation to a point over a meter northward would be equivalent to 1 g-force, and Shiran agreed with the suggestion of 1 g-force. Agnon explained that this level of g-force energy would equate to an earthquake measuring about 8 on the Richter Scale — a remarkably powerful seismic event.

In addition to tracing the brick collapse through three squares (17D, 18C, and 18D) and over two terrace levels from west to east, additional evidence of wide spread brick collapse was identified in other squares of Area F. During the 2010 season, an area of collapsed bricks (135903), consistent in size, color, and disarticulation with the collapsed bricks described above, was found in the southeast corner of Square 17C, one terrace level down (and westward) from the level of Squares 17D and 18C (Fig. 5.9). Collapse 135903 ran beneath the westward extension of medieval Terrace Wall 85420 (see Stratum F4 below). The collapse in this area sloped downward to the north, and either terminates at Wall 135908 (the south wall of an Iron Age IIB room in Square 17C) or runs under that wall (to be determined upon further excavation). In either case, Collapse 135903 is assigned to Stratum F8A on ceramic evidence, since no sherds later than Iron Age IIA were found in the sediment around or under the collapse. The upper level of the collapsed bricks in Square 17C was 202.20 masl, with the lower level yet to be excavated.

During the 2012 season, in the southwestern corner of Square 17D, the eastern extent of Collapse 135903 in Square 17C was found east of the balk, in Square 17D, where it was numbered as 155403 (Fig. 5.10). The upper level of the collapse in Square 17D was 202.30 masl, but its lower level awaits excavation. The 0.75 m wide balk which still exists between Squares 17C and 17D would seem to contain the connecting portion of the collapse on this terrace level. In Square 17D, the north edge of the collapse was excavated away during the Crusader period when the foundation trench (105407) for the Crusader Terrace Wall 85420 was dug.

At present, the excavated evidence of the collapse of brick walls of at least three different structures, on three different terraces, extending over 15 m through four squares from west to east, suggests a unified event which destroyed the walls of those structures at the same point in time, toppling the bricks of those walls in a north or north-northwest direction. The lack of any evidence of erosion of the wall foundations, or any other traumatization of the wall foundations, suggests that the superstructures of the walls did not collapse due to foundation failure, but rather were violently shifted northward off those foundations by an earthquake of approximately eight on the Richter Scale. Because the brick collapses from this event sit above the destruction layers of Stratum F9 (dated to the late 9th century BCE) and below the construction activities of Stratum F8 (mid-8th century BCE) and a Stratum F4 Crusader terrace wall (which cut into Stratum F8 material), and allowing for periods of natural sediment accumulation below and above the brick collapses (both wind-blown and winter-rain-caused), it is suggested that the earthquake which toppled the eroded walls of the abandoned buildings of Stratum F9 must have occurred at some point in the early-to-mid 8th century BCE. The earthquake mentioned in the biblical reference of Amos 1:1 (and hinted at in other biblical texts as well) seems a strong potential candidate for this event. Evidence of the 8th century BCE earthquake of Amos has been identified at other sites in Israel, including Hazor Stratum VI (Yadin 1975:150-51; Dever 1992; Freedman and Welch 1994; Austin et al. 2000; Ambraseys 2005a; 2005b; Fantalkin and Finkelstein 2006; Nur and Burgess 2008; Salamon 2010).1

1 It should be noted that recent studies have shown that there were at least two earthquakes in the mid-8th cent. BCE. See Agnon 2014: 233, table 8.1.

15. Tel es-Safi

Based upon work during the 2009 season, excavators at Tel es-Safi suggested they found eighth century seismic damage which excavation during the 2010 season further explored.104 In sum, five to six meters in length of collapsed mud bricks in Area F have been uncovered that slid north off their foundation about one meter before collapsing. While the area is located near the summit of the tel, according to the excavators, there is no evidence of fill pressure or foundation failure. The 5-6 meter east to west length of the damage and the possible imbricate arrangement of the mud bricks are consistent with seismic damage rather than a disorganized pattern of fallen mud bricks that would indicate slow deformation.105 These results are also important since field evaluation came not just from archaeologists, but from seismologists from Hebrew University and engineers from The Technion—Israel Institute of Technology. While the Safi evidence is not conclusive, the collaborative effort provides a good step forward. More evidence from areas away from the summit of the tel, thereby eliminating any type of fill pressure, will help provide further support to their work.

104 Jeff Chadwick, "The Earthquake of Amos and the Establishment of Judean Gath in the Eighth Century B.C.E."

(paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research, New Orleans, LA., 20 November 2009).

105 On imbricate pattern of mud bricks see Marco, "Recognition of Earthquake," 151.

| Period | Age | Site | Damage Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | Tell es-Safi/ Gath | in Area F on top of the abandoned level, a 20 m long brick wall was revealed, collapsed in a uniform direction and manner. Before it collapsed it shifted about a meter north of the wall’s foundation. It collapsed in a wavy haphazard manner that is often found in earthquakes. “This collapse can be closely dated… quite securely, to somewhere between the early 8th and the third quarter of the 8th century BCE (Maeir 2012: 245). At the time of this earthquake, the site had already been deserted (Maeir 2012: 247). |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Wall | Area F

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares. Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood. Chadwick and Maeir (2020) |

Fig. 1.29

Figure 1.29

Figure 1.29View, looking southeast, of a section of the collapsed brick wall (115607; Center) in Area F – probable evidence of the mid-8th century BCE earthquake. To the right is the stone foundation of W95316, from which the bricks had collapsed. Maeir (2012) Fig. 1

Figure 1

Figure 1View east toward Area F Square 18D where a low cut section of 18C reveals collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake atop Stratum F8 Judahite house surface. Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2008. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Fig. 2

Figure 2

Figure 2Section drawing of the low cut section in Area F Square 18C showing Philistine wall W95613 (Stratum F9) and the bricks (106507) which slid northward from the wall and collapsed during the Stratum F8A earthquake. The Philistine destruction debris (105613) and decades of natural erosion (105611) lie beneath the collapse. Above the collapse is the thinner layer of post-earthquake erosion deposits (105608), covered over by the Stratum F8 fill (105604) and surface (105616) held in place by Judahite retaining wall W85204. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Fig. 3

Figure 3

Figure 3Section west view in Area F Square 17D, showing collapsed bricks (left) of the Stratum F8A earthquake. The collapse was cut by a foundation trench (center) for the Crusader terrace wall (right) of Stratum F4. A Stratum F8 surface, marked by a string, sat just atop the earthquake collapse. Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2012. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Fig. 4

Figure 4

Figure 4Section east/south view in Area F Square 17C, showing collapsed bricks and their plaster coatings from the Stratum F8A earthquake. Strata F8/F7 banked up and over the collapsed bricks in the area outside the photo (bottom). Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2010. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Figs 5.3,4,6-10,12

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3Brick Collapse 85309 in Square 18C, view to south (2005 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4Brick Collapse 115607 seen in the eastern section of Square 18C (2008 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6Brick Collapse 115607 seen in the section line of Squares 18C and 18D (2009 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.7Brick Collapse 115607, Square 18D, 25 cm east of the line of Squares 18C/18D (2010 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.8Brick Collapse 115607 in Square 18C, excavation exposure (2010 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.9

Figure 5.9Brick Collapse 135903 in the southeast corner of Square 17C (2010 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.10

Figure 5.10Brick Collapse 135903 (155403) in the southwest corner of Square 17D (2012 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.12

Figure 5.12House 105650, with surface partially excavated to reveal Collapse 115607 (2008 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020) Screen shot from a youtube video

Screenshot of video of Aren Maeir describing evidence of 8th cent. BCE earthquake at Tell es-Safi/Gath, Israel

Screenshot of video of Aren Maeir describing evidence of 8th cent. BCE earthquake at Tell es-Safi/Gath, Israel

youtube |

|

| Sheared Wall | Area F

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares. Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood. Chadwick and Maeir (2020) |

Fig. 1

Figure 1

Figure 1View east toward Area F Square 18D where a low cut section of 18C reveals collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake atop Stratum F8 Judahite house surface. Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2008. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Fig. 2

Figure 2

Figure 2Section drawing of the low cut section in Area F Square 18C showing Philistine wall W95613 (Stratum F9) and the bricks (106507) which slid northward from the wall and collapsed during the Stratum F8A earthquake. The Philistine destruction debris (105613) and decades of natural erosion (105611) lie beneath the collapse. Above the collapse is the thinner layer of post-earthquake erosion deposits (105608), covered over by the Stratum F8 fill (105604) and surface (105616) held in place by Judahite retaining wall W85204. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) |

|

| Broken Corners | Area F

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares. Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood. Chadwick and Maeir (2020) |

|

|

| Collapsed Walls | Area A, the flatter terrain of Gath's lower east side, and Area D

Figure 1.33

Figure 1.33Aerial view, looking west, of Tell es-Safi/Gath

Maeir (2020)

Figure 4

Figure 4Plan of Tell es-Sâfi/Gath with location of the various excavation areas. Maeir (2017) |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Discussion | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Wall | Area F

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares. Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood. Chadwick and Maeir (2020) |

Fig. 1.29

Figure 1.29

Figure 1.29View, looking southeast, of a section of the collapsed brick wall (115607; Center) in Area F – probable evidence of the mid-8th century BCE earthquake. To the right is the stone foundation of W95316, from which the bricks had collapsed. Maeir (2012) Fig. 1

Figure 1

Figure 1View east toward Area F Square 18D where a low cut section of 18C reveals collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake atop Stratum F8 Judahite house surface. Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2008. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Fig. 2

Figure 2

Figure 2Section drawing of the low cut section in Area F Square 18C showing Philistine wall W95613 (Stratum F9) and the bricks (106507) which slid northward from the wall and collapsed during the Stratum F8A earthquake. The Philistine destruction debris (105613) and decades of natural erosion (105611) lie beneath the collapse. Above the collapse is the thinner layer of post-earthquake erosion deposits (105608), covered over by the Stratum F8 fill (105604) and surface (105616) held in place by Judahite retaining wall W85204. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Fig. 3

Figure 3

Figure 3Section west view in Area F Square 17D, showing collapsed bricks (left) of the Stratum F8A earthquake. The collapse was cut by a foundation trench (center) for the Crusader terrace wall (right) of Stratum F4. A Stratum F8 surface, marked by a string, sat just atop the earthquake collapse. Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2012. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Fig. 4

Figure 4

Figure 4Section east/south view in Area F Square 17C, showing collapsed bricks and their plaster coatings from the Stratum F8A earthquake. Strata F8/F7 banked up and over the collapsed bricks in the area outside the photo (bottom). Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2010. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Figs 5.3,4,6-10,12

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3Brick Collapse 85309 in Square 18C, view to south (2005 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.4

Figure 5.4Brick Collapse 115607 seen in the eastern section of Square 18C (2008 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.6

Figure 5.6Brick Collapse 115607 seen in the section line of Squares 18C and 18D (2009 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.7

Figure 5.7Brick Collapse 115607, Square 18D, 25 cm east of the line of Squares 18C/18D (2010 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.8

Figure 5.8Brick Collapse 115607 in Square 18C, excavation exposure (2010 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.9

Figure 5.9Brick Collapse 135903 in the southeast corner of Square 17C (2010 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.10

Figure 5.10Brick Collapse 135903 (155403) in the southwest corner of Square 17D (2012 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.12

Figure 5.12House 105650, with surface partially excavated to reveal Collapse 115607 (2008 season). Chadwick and Maeir (2020) Screen shot from a youtube video

Screenshot of video of Aren Maeir describing evidence of 8th cent. BCE earthquake at Tell es-Safi/Gath, Israel

Screenshot of video of Aren Maeir describing evidence of 8th cent. BCE earthquake at Tell es-Safi/Gath, Israel

youtube |

|

VIII+ |

| Sheared Wall | Area F

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares. Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood. Chadwick and Maeir (2020) |

Fig. 1

Figure 1

Figure 1View east toward Area F Square 18D where a low cut section of 18C reveals collapsed bricks of the Stratum F8A earthquake atop Stratum F8 Judahite house surface. Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2008. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) Fig. 2

Figure 2

Figure 2Section drawing of the low cut section in Area F Square 18C showing Philistine wall W95613 (Stratum F9) and the bricks (106507) which slid northward from the wall and collapsed during the Stratum F8A earthquake. The Philistine destruction debris (105613) and decades of natural erosion (105611) lie beneath the collapse. Above the collapse is the thinner layer of post-earthquake erosion deposits (105608), covered over by the Stratum F8 fill (105604) and surface (105616) held in place by Judahite retaining wall W85204. Chadwick and Maeir (2018) |

|

IX |

| Broken Corners | Area F

Figure 5.2

Figure 5.2Plan of Area F-Upper, showing major features uncovered and excavated squares. Chadwick and Maeir (2020)

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1Aerial photo of Area F and surroundings – view to the east (2013). Area F-Upper consists of the 13 open squares on the eastern (upper) terrace. The platform at upper left is where the Blanche Garde fortress stood. Chadwick and Maeir (2020) |

|

VI+ | |

| Collapsed Walls | Area A, the flatter terrain of Gath's lower east side, and Area D

Figure 1.33

Figure 1.33Aerial view, looking west, of Tell es-Safi/Gath

Maeir (2020)

Figure 4

Figure 4Plan of Tell es-Sâfi/Gath with location of the various excavation areas. Maeir (2017) |

|

VIII+ |

| Variable | Input | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| g | Peak Horizontal Ground Acceleration | ||

| Variable | Output - Site Effect not considered | Units | Notes |

| unitless | Conversion from PGA to Intensity using Wald et al (1999) |

Ackerman et. al. (2005) A unique human-made trench at Tell es-Safi/Gath, Israel: Anthropogenic impact and landscape response

March 2005 Geoarchaeology 20(3):303 - 327

Asscher, Y. et al. (2015) Radiocarbon Dating Shows an Early Appearance of Philistine Material Culture in Tell es-Safi/Gath, Philistia

, Radiocarbon v. 57 Number 5, pp. 825-850

Avissar, Rona S. (2004) Reanalysis of the Bliss and Macalister Excavations at Tell es-Safi in 1899 (M.A. thesis), Ramat-Gan

2004 (in Hebrew with Eng. abstract).

Avissar Lewis, Rona S. and Maeir, Aren M. (2017) New Insights into Bliss and Macalister's Excavations at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,

Near Eastern Archaeology

Vol. 80, No. 4, The Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Archaeological Project (December 2017), pp. 241-243 (3 pages)

Avissar Lewis, Rona (2015) Bliss and Macalister Work at Tell es-Safi: A Reappraisal in Light of Recent Excavations in

Villain or Visionary? R.A.S. Macalister and the Archaeology of Palestine: Proceedings of a Workshop held at the Albright

Institute of Archaeological Research, Jerusalem, on 13 December 2013

Chadwick, Jeff (2009) "The Earthquake of Amos and the Establishment of Judean Gath in the Eighth Century B.C.E."

(paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research, New Orleans, LA., 20 November 2009).

Finkelstein, I. (2022) A Battle between Joahaz and Hazael?

BN.NF (195): 55-62

Maeir, Aren M. and Chadwick, Jeffrey R. (2018) Judahite Gath in the Eighth Century B.C.E.: Finds in Area F from the Earthquake to the Assyrians,

Near Eastern Archaeology Vol. 81, No. 1, The Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Archaeological Project (March 2018), pp. 48-54 (7 pages)

Published By: The University of Chicago Press

Napchan-Lavon, Sharon, Gadot, Yuval and Lipschits, Oded (2015)

BLISS AND MACALISTER’S EXCAVATIONS AT TELL ZAKARIYA (TEL AZEKAH)

IN LIGHT OF PUBLISHED AND PREVIOUSLY UNPUBLISHED MATERIAL, The Palestine Exploration Fund 2015

Maeir, Aren M. (2017) The Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Archaeological Project: Overview - Near Eastern Archaeology

Vol. 80, No. 4, The Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Archaeological Project (December 2017), pp. 212-231 (20 pages)

Maeir, Aren M. (2004) The Historical Background and Dating of Amos VI 2: An Archaeological

Perspective from Tell e§-Safi/Gath. Vetus Testamentum 54: 319-34.

Raphael, Kate and Agnon, Amotz (2018). EARTHQUAKES EAST AND WEST OF THE DEAD SEA TRANSFORM IN THE BRONZE AND IRON AGES.

Tell it in Gath Studies in the History and Archaeology of Israel Essays in Honor of Aren M. Maeir on the Occasion of his Sixtieth Birthday.

Schniedewind, W. M. (1998) The Geopolitical history of Philistine Gath – #309 pp. 69-77

Uziel, J. (2003) The Tell es-Safi Archaeological Survey (M.A. thesis), Ramat-Gan 2003

Near Eastern Archaeology - Vol. 80, No. 4, December 2017, The Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Archaeological Project

Near Eastern Archaeology - Vol. 81, No. 1, March 2018, The Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Archaeological Project

Publications Relating to the Tell es-Safi/Gath Archaeological Project (1996-2009)

Quarterly statement, 31 1899 – F. J. Bliss First report pp. 188-199

Quarterly statement, 31 1899 – F. J. Bliss Second report pp. 317-333

Quarterly statement, 32 1900 – F. J. Bliss Third report pp. 16-29

Rock cuttings of Tel es-Safi – R.A. S. Macalister pp. 29-39

Maeir, M. ed. (2012) Tell Es-Safi/Gath I The 1996-2005 Seasons

Aren M. Maeir and Joe Uziel ed. (2020) Tell Es-Safi/Gath II Excavations and Studies Volume 2

Shai, Itzhaq, Greenfield, Haskel J., and Maeir, Aren M. ed. (2023) Tell es Safi Gath III The Early Bronze Age, Part 1.

ÄGYPTEN UND ALTES TESTAMENT Studien zu Geschichte, Kultur und Religion Ägyptens und des Alten Testaments Band 122 Zaphon Munster

The Tell es-Safi/Gath Archaeological Project Official (and Unofficial) Weblog

Bibliography on Safi from

The Tell es-Safi/Gath Archaeological Project Official (and Unofficial) Weblog

Aren Maeir's home page on academia.edu

Aren Maeir on Wikipedia

Photo essay on Gath by Aren Maeir

Gath at biblewalks.com

Gath at bibleplaces.com

J. Uziel, The Tell es-Safi Archaeological Survey (M.A. thesis), Ramat-Gan 2003

R. S.Avissar, Reanalysis of the Bliss and Macalister Excavations at Tell es-Safi in 1899 (M.A. thesis), Ramat-Gan

2004 (Eng. abstract).

J. D. Seger, ABD, 2, New York 1992, 908–909

J. A. Blakely, BA 56 (1993), 110–115

C. S. Ehrlich, The Philistines in Transition: A History from ca. 1000–730 B.C.E. (Studies in the History and Culture of the

Ancient Near East 10), Leiden 1996; id., Kein Land für sich allein, Freiburg 2002, 56–69

I. Finkelstein, IEJ 46 (1996), 225–242

T. J. Schneider, ASOR Newsletter 46/2 (1996), 17; id., BA 60 (1997), 250

A. J. Boas (& A. M. Maeir), The Judean Shephelah: Man, Nature and Landscape. Proceedings of the 18th Annual

Conference of the Martin (Szusz) Department of Land of Israel Studies (ed. O. Ackermann), Ramat-Gan

1998, 33–39 id (et al.), ESI 20 (2000), 114*–115*; id. (& A. M. Maeir), Crusades (2004) (in press)

S. Gitin, Mediterranean Peoples in Transition, Jerusalem 1998, 162–186

A. M. Maeir (& A. J. Boas), AJA

102 (1998), 785–786; id., ESI 110 (1999), 68* (with A. J. Boas); 112 (2000), 96*–97*; 97*–98* (with C. S.

Ehrlich); id. (& C. S. Ehrlich), BAR 27/6 (2001), 22–31; id., ASOR Annual Meeting Abstract Book, Boulder,

CO 2001, 17; id., Settlement, Civilization and Culture: Proceedings of the Conference in Memory of David

Alon (eds. A. M. Maeir & E. Baruch), Ramat-Gan 2001, 111–131; id., IEJ 53 (2003), 237–246; id., Shlomo:

Studies in Epigraphy, Iconography, History and Archaeology (S. Moussaieff Fest.; ed. R. Deutsch), Tel

Aviv-Jaffa 2003, 197–206; id., Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft

des Heiligen Landes 10 (2004), 185–186; id., New Studies on Jerusalem 10 (2004), 46*; id., VT 54 (2004),

319–334; id. (et al.), Ägypten und Levante 14 (2004), 125–134; id., ICAANE, 3, Paris 2002, Winona Lake,

IN (forthcoming); id., Philister-Keramik (Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie),

Berlin (forthcoming); id., The Philistines and Other Sea Peoples (eds. A. Killebrew & G. Lehmann), Leiden

(forthcoming)

W. M. Schniedewind, BASOR 309 (1998), 69–77

Y. Dagan, The Settlement in the Judean

Shephelah in the 2nd and 1st Millennium B.C.: A Test-Case of Settlement Processes in a Geographic Region

(Ph.D. diss.), Tel Aviv 2000 (Eng. abstract); id., ESI 114 (2002), 83*–85*

I. Shai, Philistia and the Judean

Shephelah Between the Campaign of Shishaq and the First Assyrian Campaigns to the Land of Israel: An

Archaeological and Historical Review (Ph.D. diss.), Ramat-Gan 2000 (Eng. abstract); id., ASOR Annual

Meeting 2004 www.asor.org/AM/am.htm; id. (& A. M. Maeir), The Pre-LMLK Jars: A New Class of Storage

Jars of the Iron Age IIA, Tel Aviv (forthcoming)

J. Bentley & T. J. Schneider, Computational Statistics

and Data Analysis 32 (2001), 465–483; B. Halpern, David’s Secret Demons (The Bible in its World), Grand

Rapids, MI 2001

A. Ben-David, Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies,

Amman, Jordan, 2–11.9.2000 (BAR/IS 1084; eds. P. Freeman et al.), Oxford 2002, 103–112

N. Na’aman, IEJ 52 (2002), 200–224

H. M. Niemann, Kein Land für sich allein, Freiburg 2002, 70–91

O. Ackermann et al., Catena: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Soil Science, Hydrology-Geomorphology 53 (2003), 309–330;

id., Geoarchaeology 18 (2003); 20 (2005), 303–327; id., JSRS 13 (2004), xxix–xxx; 14 (2005), xxxi; T.

Barako, BAR 29/2 (2003), 27–33, 64, 66; 30/1 (2004), 53–54

M. Cohen, ESI 115 (2003), 73*

T. Dothan, Symbiosis, Symbolism, and the Power of the Past, Winona Lake, IN 2003, 189–213

D. Ben-Shlomo, BASOR 335 (2004), 1–35; id., Pottery Production Centers in Iron Age Philistia: An Archaeological and Archaeometric Study (Ph.D. diss.), Jerusalem 2005

Y. Goren et al., Inscribed in Clay, Tel Aviv 2004, 279–286

N. Lalkin, TA 31 (2004), 17–21; Artifax 20/4 (2005), 8

J. Sudilovsky, BAR 31/6 (2005), 19

J. Uziel (& A. M. Maeir), TA 32 (2005), 50–75.

- Aren Maeir describing evidence of 8th cent. BCE earthquake in Area F

- from youtube

Schniedewind (1998:69) reports that

the identification of Philistine Gath with Tell es-Safi has met with

widespread, though not complete, acceptance.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page NOT AVAILABLE YET

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master Lachish kmz file | various |