Fig. 16. Map of intensity distribution for May 20, 1202 earthquake

(Ambraseys and Melville, 1988). Shaded zone is the most affected

region. (from

Sbeinati et al, 2005)

AD 1202 May 20 Baalbek

A large earthquake occurred in the Middle East around

daybreak on 20 May 1202. It was felt across an area of

radius 500 km: from the Nile Delta in the south to Lesser

Armenia in the north and from Cyprus in the west to the

eastern parts of Syria.

It caused widespread damage in Syria. In Tyre,

everything, with the exception of three towers and some

outlying fortifications, was destroyed. A third of Acre

was probably destroyed, with considerable damage to the

royal palace and the walls, although the Knights Templar

complex in the southwest of the city was spared. At least

some repairs took place in both cities.

Inland, in Samaria (Shamrin) and Hauran, dam-

age was equally severe. It was reported that Safa was

partially destroyed, resulting in the deaths of all but the

son of the garrison commander. Also Hunin (Chastel

Neuf), Baniyas (Paneas) and Tibnin (Toron) were badly

affected. The walls at Bait Jann collapsed. A landslide

reportedly razed a village near Busra to the ground and

Nablus was totally flattened, except for a few walls, and

may have sustained further damage in an aftershock.

Most of the towns of the Hauran were so badly damaged

as to be rendered unidentifiable.

Jerusalem suffered relatively little, but further

north Damascus was strongly shaken. Many houses

apparently collapsed and major buildings near the citadel

were damaged. The Ummayad mosque lost its eastern

minaret and 16 crenellations on its north wall. One man

died when the Jirun (eastern) gate fell and the lead

dome split in two and one of the other minarets fissured.

The adjacent Kallasa mosque was ruined, killing

two people, and the nearby Nur ed Din Hospital was

completely flattened. People fled to the safety of open

spaces.

Further north, houses collapsed in Jubail

(Gibelet), the battlements of the walls of Beirut had

to be repaired and Batun was damaged, but this damage

may have been due, at least partially, to military attacks.

Rock falls on Mt Lebanon killed 200 people and nearby

Baalbek was almost totally ruined.

Damage to Tripoli was probably substantial, since

it is said that there was loss of life. The castles of Arches

(`Arqa) and Arsum (`Arima?) were almost destroyed,

and Chastel Blanc (Safitha) was badly weakened, while

the castles of Margat (Marqab), Krak (Hisn al-Akrad)

and Barin suffered some damage but remained secure.

Tarsus (Tortosa) largely escaped damage, however.

At Hims (Homs, Emessa) the earthquake caused

a castle watchtower to collapse. In Hamah there were

two shocks, the first lasting for a long time, then a second,

stronger shock, which destroyed the castle and many

other buildings.

The earthquake was felt in Aleppo and other

regional capitals, and less strongly in Antioch. It was perceptible

at a few places further away, such as Mosul and

in Mesopotamia, at Akhlat and from Qus on the Nile.

In Egypt, the shock was felt in Alexandria and in Cairo

woke sleepers and shook buildings, threatening the collapse

of tall structures.

In Cyprus the earthquake was felt, causing no

damage, but it was felt strongly on the east coast of the

island, where a seismic sea wave flooded the eastern coast

of Cyprus and the coast of Syria.

The death toll is uncertain bacause the earthquake

coincided with famine and plague, but it must have

been high, since it struck at daybreak when most people

were still in bed.

Aftershocks lasting at least four days were

reported in Hamah, Damascus and Cairo. For an attempt

to locate a probable coseismic surface fault break the

basis of exclusively on geomorphology, see Ellenblum

et al. (1998) and Daeron et al. (2005)

This earthquake has been examined by

Ambraseys and Melville (1988). However, new data

have been found, and the intensity has been re-evaluated

using a modified version of the MSK intensity scale,

which takes into account the high vulnerability of the

building stock in the region, necessitating a review of the

original conclusions. Also because of the importance of

the event and for the sake of completeness, a summary

and full translations of the most important sources are

given here.

This was a major earthquake in the upper Jordan

and Litani Valleys, responsible for tens of thousands of

casualties in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Owing to

the Crusader presence in the Levant, information on the

effects of the earthquake is available from both Chritian

and Muslim authors. Both sets of data naturally

refer most particularly to the territory belonging to their

respective sides, but they complement each other to a

large degree.

It is clear that most of the chronological confusion

surrounding the event has been caused by the uncritical

use of Muslim chronicles. It is also remarkable that hardly

any use has been made of western sources, which are far

more accessible to most European authors and unambiguously

resolve the dating of the earthquake. These

works, though largely ignored by earthquake cataloguers,

are of course well known to the historians of the Crusades

(e.g. Rehricht 1898).

The political context of the earthquake is briefly

outlined in Mayer (1972; 1989; see also [1, 2]) and more

fully in Cahen (1940), Runciman (1951; 1952; 1954; 1965)

and Setton (1969), where detailed reference is made to

the narrative sources available. The Crusader states had

been greatly reduced by Saladin's campaign of 1187 and

only partially reconstituted by the Third Crusade, most of

their defenses being in a vulnerable state of repair.

Regarding the non-Muslim accounts, it is unfortunate

that the main political and military developments at

this time were taking place outside the Levant, in preparation

for the ill-fated Fourth Crusade. The focus is not,

therefore, so clearly on events in the east, where the Crusader

states were on the defensive and greatly reduced

in terms of their sphere of operations. Most of the few

places retained by the Christians are mentioned in European

accounts, all in the truncated kingdom of Jerusalem

and the county of Tripoli, on or near the coastal strip.

No details of wider effects in the Syrian hinterland

are given in Christian sources. Similarly, no details of

the shock further north, in the principality of Antioch, are

provided, beyond the indications that it was not severe

there.

The two letters from the Hospitaller and Templar

Grand Masters published in Mayer (1972) contain

the fullest occidental accounts and refer particularly to

the possessions of their respective Orders. Very few

additional details are found in other sources (among

them the references to Jubail in various texts of the

Annales de Terre Sainte).

As demonstrated by Mayer, the near contemporary

account of Robert of Auxerre (died

1212) has many points of similarity with Philip du

Plessis' description. Variations of date occur in the

Christian sources, but not concerning the year. William

of Nangis (died c. 1300) gives 30 May, three days before

Ascension (which was in fact on 23 May in 1202). Felix

Fabri (fl. 1480) has 30 March. The Barletta manuscript

(Kohler 1901, 401) appears to read 3 March. Most of

these sources are telegraphic, containing only general

information.

Arabic sources from the Muslim areas surrounding

the Christian states naturally offer a broader perspective

and provide the most information. Just as both the

contemporary European letters date the earthquake to

Monday 20 May 1202, so do a comparable pair of Arabic

letters from Hamah and Damascus. These were received

by `Abd al-Latif b. al-Labbad al-Baghdadi, who was in

Cairo at the time of the earthquake and wrote his account

in Ramadan 600/May 1204, two years after the event.

Both he and the letters he transcribes give the date as

early on the morning of Monday 26 Sha'aban 598 hijri

(Muslim calendar = 21 May 1202, which was a Tuesday)

or 25 Pashon (Coptic calendar = Monday 20 May). A discrepancy

of one day is common when converting from

the Muslim calendar. As noted above, the latter date is

confirmed by the contemporary European accounts. Abu

Shama, quoting the testimony of al-'Izz Muhammad b.

Taj al-Umana' (died a.H. 643/AD 1245), also had Monday

26 Sha'ban, 598 or 20 Ab (Syriac calendar = August

(sic.) 1202).

There can thus be no doubt that the correct Muslim

year is 598 a.H. which runs from 1 October 1201

to 19 September 1202. Unfortunately other later Arabic

texts contain variations on the date of the earthquake and

in some cases split its effects into accounts of separate

events in different years. The most influential of these

alternative texts is that of Ibn al-Athir of Mosul (died

1233), who has a general account of the earthquakes felt

throughout Mesopotamia, Egypt, Syria and elsewhere,

dated Sha'ban 597 a.H. which is a year early. It is not

clear whether he refers to the same event. His account

is followed almost verbatim in the Syriac Chronicle of

Bar Hebraeus (Abu 'l-Faraj, died 1286), and in greatly

abbreviated form by Abu 'l-Fida (died 1331), under 597

a.H. Another early source, Abu 1-Fada'il of Hamah (c.

1233) has a brief notice of the shock under 597 a.H.

It is of interest that he does not refer to the shock in

Hamah, but mentions that it destroyed most of the towns

belonging to the 'Franks'. Reconciling these accounts is

no problem; it is simply that an error of one year has

occurred.

A greater problem is introduced since Ibn al-

Athir has another, shorter but similar, account of the

(same) earthquake under the year 600 a.H. (10 September

1203 to 28 August 1204), without specifying the

month. He says that the shock destroyed the walls of Tyre

and also affected Sicily and Cyprus. This 'second' earthquake

is once more reported by Bar Hebraeus and Abu

'l-Fida. A similar account, with the addition of new information

that the shock was felt in Sabta (Ceuta), is given

by Ibn Wasil (died 1298). Since Ibn Wasil was a native

of Hamah, it is surprising that he does not have access to

independent local information. Neither does he have any

reference to the shock under 597 or 598 a.H.

It is not clear why Ibn al-Athir should duplicate

his account under the dates 597 and 600 a.H., but it is

perhaps sufficient to note that this sort of duplication is

not uncommon in both European and Islamic medieval

chronicles. Within this repetition, there must be some

echo of large aftershocks or a prolonged period of seismic

activity.

Two separate notices are also found in the chronicle

of Sibt b. al-Jauzi (died 1256), this time under 597

and 598 a.H. The first account, under Sha'ban 597 a.H.

echoes that of `Abd al-Latif, while mentioning a few additional

places. The date, however, is the one given by

Ibn al-Athir. Sibt b. al-Jauzi supports this date by saying

(480) that after these earthquakes in a.H. 597/AD 1201,

both 'Imad al-Din (the historian whose work he had earlier

quoted for an account of the famine in Egypt that

year) and the author's own grandfather (the historian Ibn

al-Jauzi) died. It is generally accepted that both men did

indeed die in this year and thus 'before the earthquake'.

This is awkward to explain, but the author is probably

trying to rationalise two conflicting pieces of chronological

data. He is not so much dating the deaths by reference

to the earthquake as accommodating the false date that

he has accepted for the earthquake within the sequence

of other events that year. Under the correct year, 598

a.H. he has a much briefer account, describing damage

to the castles at Hims and Hisn al-akrad. He says the

shock extended to Cyprus and destroyed what was left

of Nablus (i.e. after the first earthquake). This implies

two shocks. On the other hand, Sibt b. al-Jauzi's second

account is not unlike Ibn al-Athir's second account

(under 600 a.H.), and may again simply be an attempt to

accommodate the conflicting dates. It is significant that

Sibt b. al-Jauzi has no report of an earthquake under

600 a.H. Abu Shama, who quotes Sibt b. al-Jauzi's

accounts under 597 and 598 a.H. in turn, in both cases

cites the additional testimony of al'Izz b. Taj al-umana',

a descendant of Ibn `Asakir and continuator of the latter's

Biographical History of Damascus (Cahen, 1940).

It is clear that the first part of Sibt b. al-Jauzi's 597

a.H. account also follows al-'Izz. Under 598 a.H. al-'Izz

records the effect of the shock in northern Syria and in

Damascus, with some minor details in addition to those

provided by `Abd al-Latif.

A1-Suyuti summarises the dating confusion found

in his sources, by entering the earthquake under 597

a.H. (quoting al-Dhahabi, `Ibar and Sibt b. al-Jauzi), 598

a.H. (quoting Sibt b. al-Jauzi) and 600 a.H. (citing Ibn

al-Athir). Later sources add no details. It is worth noting

that the Aleppo author Ibn al-'Adim (died 1262) makes

no reference to the earthquake under any of the years

found elsewhere.

Despite the conspicuous duality of accounts in

almost all Muslim sources, probably reflecting protracted

aftershock activity, there remains no evidence of more

than one principal but multiple earthquake. Apart from

the silence of contemporary occidental and oriental

authors, `Abd al-Latif was in a position to record separate

earthquakes in both 597 and 600 a.H. had they

occurred. The amalgamation of these several accounts

therefore removes much of the mystery surrounding the

a.H. 598/AD 1202 event, and allows a coherent identification

of its effects and the area over which it was

felt. Many sources speak of strong effects and significant

damage along the Mediterranean littoral of Syria,

affecting both the 'Franks' and the 'Saracens' (Abu

'l-Fada'il, fol. 113a-b; Hethum Gor'igos, 480, Ibn al-

Furat, 240). Specifically, the two main Christian centres,

Acre and Tyre, were severely damaged, with loss of life.

Contemporary letters (Mayer 1972) speak of damage to

walls and towers in both cities, including the palace at

Acre. The house of the Templars in Acre (in the southwest

of the city, see Enlart 1928, 23) was, however, fortunately

spared. All but three towers and some outlying

fortifications were destroyed in Tyre, together with

churches and many houses. The English chronicler Ralph

of Coggeshall (died 1228) says that most of Tyre and

one third of Acre were overthrown (Cogg. 141-2). Muslim

sources largely confirm this, `Abd al-Latif stating that

the greatest part of Acre and one third of Tyre were

destroyed. Intensities in Tyre may be assessed as having

been higher than those in Acre, respectively about IX

and VIII. Funds were made available for both cities to be

reconstructed (L'Estoire de Eracles, 245; Sanuto ii, 203),

though no specific indication of the extent of these repairs

is available (Enlart 1928, 4, Deschamps 1939, 137).

Inland from the Christian territories, in Shamrin

(Samaria) and Hauran, damage was equally serious. It

was reported that Safad was partially ruined, with the loss

of all but the son of the garrison commander; also Hunin

(Chastel Neuf), Baniyas (Paneas) and Tibnin (Toron)

were badly affected. At Bait Jann (Bedegene), not even

the foundations of walls remained standing, everything

having been 'swallowed up'. Two possibilities present

themselves for the identification of Bait Jann out of the

three noted by de Sacy in `Abd al-Latif (446), both being

known to the Crusaders (see Dussaud 1927, 7, 391). The

first is 10 km west of Safad and the second on the road

between Damascus and Baniyas (see Ibn Jubayr (300),

who described it as situated in between the mountains).

The context in which Bait Jann is mentioned by `Abd al-

Latif allows either alternative to be acceptable, but the

second .is preferred here because the location was better

known as marking the boundary between Muslims and

Franks before the conquests of Saladin (cf. Deschamps

1939, 146). In Nablus there was total destruction except

for some walls in the 'Street of the Samaritans', while in

Hauran province most of the towns were so badly damaged

that they could not be readily identified (`Abd al-

Latif, 417, Sibt b. al-Jauzi, 478). It is said that one of the

villages around Busra was completely destroyed, perhaps

by landslides (Ibn al-Athir, xii, 112).

To the south of this area, Jerusalem suffered

lightly, according to the information available to `Abd al-

Latif (415, 417). His account indicates that further north,

however, Damascus was strongly shaken. A number of

houses are reported to have collapsed and besides the

destruction in town, major buildings near the citadel were

damaged. The Umayyad mosque lost its eastern minaret

and 16 ornamental battlements along its north wall. One

man was killed in the collapse of the Jirun (eastern) gate

of the mosque. The lead dome of the mosque was split

in two and one other minaret fissured (cf. Le Strange

1890, 241). The adjacent Kallasa mosque was ruined,

killing a North African and a Mamluk slave (Abu Shama,

29, quoting al-'Izz). This building had been founded in

1160 by Nur al-Din and restored by Saladin in 1189 after

its destruction by fire (Elisseeff 1967, 294). West of the

mosque, Nur ad Din's hospital was completely destroyed.

People fled for the safety of open spaces. The shock

in Damascus was of long duration and old men could

not recall ever .having felt such a severe tremor (`Abd

al-Latif, 416-417). Previous destructive earthquakes had

occurred in 1157 and 1170. Another slight shock was felt

early the following morning (Abu Shama, 29), and aftershocks

continued for at least four days (`Abd al-Latif,

417). Further north, houses are said to have collapsed

at Jubail (Gibelet), which had recently been recovered

by the German Crusade (1197), restoring the land link

between the Kingdom of Acre and the County of Tripoli

(Annales de Terre Sainte, 435, Chronique de Terre Sainte,

16). The walls of Beirut, also regained in 1197, are said

to have been repaired at about this time following earthquake

damage (variant readings in L'Estoire de Eracles

(244-245) incorrectly under 1200; likewise Ernoul, 338).

The fact that the Prince of Batrun, a Pisan, granted his

compatriots remission of taxation early in 1202 indicates

that this town too suffered damage (Muralt 1871, 264).

The extent of the destruction is not easy to assess in these

places. The walls of Jubail were dismantled by Saladin

in 1190 and were probably not rebuilt after the Christian

takeover. Wilbrand of Oldenburg, who visited Jubail

in 1211, found only a strong citadel, and a similar situation

in Beirut and Batrun (166-167; cf. Rey 1871, 121).

There is therefore the danger that the extensive military

operations in the period before and during the Third Crusade

are misreported as earthquake damage, and even if

this is not the case, some of these castles may have been

rendered more vulnerable by acts of warfare. Inland rock

falls from Mt Lebanon, however, overwhelmed about 200

people from Baalbek who were gathering rhubarb. Baalbek

itself was destroyed despite its strength and solidity

(`Abd al-Latif, 416).

In the County of Tripoli, the Christian sources disagree

slightly on the degree of damage to Tripoli itself,

though both main accounts refer to heavy loss of life

(Mayer 1972). Ibn al-Athir (xii, 112) also refers to the

heavy damage there, suggesting intensities not less than

VIII. Other strongholds were severely shaken. The castle

of 'Arco (Arches) was ruined and deserted villages

in the area were taken by Philip du Plessis to indicate

heavy loss of life, but perhaps this simply implied the

flight of the inhabitants, since famine and sickness were

also rife. It may be noted that Rey (1871, 92) cites `Abd

al-Latif and Robert of Auxerre concerning an earthquake

in Sha'ban 597 (sic.)120 May 1202 that destroyed Jebel

`Akkar and Chastel Blanc, falsely equating `Archas'

with `Akkar, which the occidentals called Gibelcar. The

destruction of `Arqa is also mentioned by Arab writers

(`Abd al-Latif, 417, Abu Shama, 29). Philip du Plessis

records the complete destruction of the castle at `Arsum',

which is not satisfactorily identified but perhaps refers to

`Arima. Mayer (1972, 304) is reluctant to identify Arsum

but points to the possibility of Arsuf, near Caesarea. Support

for this is found in the account of the pilgrimage

of Wilbrand of Oldenburg, who in 1212 found the small

ruined town of `Arsim' (Arsuf) on his way to Ramla

(184). As Mayer mentions, however, the letter seems to

refer rather to a place in Tripoli, and `Arima is suggested

on the grounds (1) that it probably belonged to the Templars

and (2) it was one of the few strongholds retained

by the Christians in the truce that ended the Third Crusade

(Setton 1969, i. 664). It is situated a few miles south-southwest

of Chastel Blanc. Philip further reported that

the greater part of the walls of the Templar stronghold

Chastel Blanc (Safitha) had fallen and the keep had been

weakened to such an extent that it would have been better

had it collapsed completely. `Abd al-Latif (417) also

mentions the destruction of the castle. The castle keep

was probably rebuilt using existing materials (Deschamps

1977, 257-258). Tortosa (Tartus), however, its Templar

citadel and notably the Cathedral of Notre Dame seem

largely to have been spared (Berchem and Fatio 1914,

323; Enlart 1928, 397).

The Grand Master of the Hospitallers (Geoffrey

of Donjon) wrote that their strongholds at Margat (Marqab)

and Krak were badly damaged but could probably

still hold their own in the event of attack. Damage to

Krak (Hisn al-akrad) is also mentioned in the account of

Sibt b. al-Jauzi (510). In the same vicinity, but in Muslim,

hands, the castle of Barin (Montferrand), despite its compactness

and fineness, was also damaged (`Abd al-Latif,

416).

There is little additional evidence to help assess

the intensities indicated by these reports. Authors

of studies of military architecture (e.g. Rey 1871,

Deschamps 1934; 1977) on the whole use documentary

evidence of earthquakes to support the chronology and

identification of building phases at the castles, rather than

documentary or archaeological evidence of rebuilding to

indicate the extent of earthquake damage. Indeed, it is

interesting that Deschamps, unaware of the reports of

earthquake damage at Marqab in 1202, makes no reference

to this specific period as being one of substantial

building at the castle (Deschamps 1977, 282-284),

whereas in the case of Krak, damage done by the earthquake

is thought to have been responsible for some of

the reconstruction work analysed (Deschamps 1934, 281).

Even so, the fact that the knights of Krak were frequently

on the offensive in the next few years after 1203, and

were joined by the knights from Marqab, is thought to

indicate that both castles Were 'already in a perfect state

of defence'. These raids may rather suggest that attack

was the best form of defence. Nevertheless, the circumstantial

testimony by Geoffrey can be taken at face value

and is supported by the fact that Marqab successfully

resisted a counter-attack by al-Malik al-Zahir, amir of

Aleppo, in a.H. 601/AD 1204-1205 (Ibn Wasil, iii. 165).

Both Marqab and Krak were visited in 1211 by Wilbrand

of Oldenburg and seemed to his probably unprofessional

gaze to be very strong, the latter housing 2000 defendants

(169-170). Few details are available about Barin, which

was finally dismantled in 1238-39 (Deschamps 1977, 322).

It seems unlikely that intensities exceeding VII coupled

with a long duration of shaking were experienced at any

of these strongholds.

In neighbouring Muslim territory, the shock

was experienced at similar intensities in Hims (Hons,

Emessa), where a watchtower of the castle was thrown

down (Sibt b. al-Jauzi, 510), and Hamah, where the earthquake

was experienced as two shocks, the first lasting 'an

hour' and the second shorter but stronger. Despite its

strength, the castle was destroyed, together with houses

and other buildings. Two further shocks followed in the

afternoon (`Abd al-Latif, 416). Considerable damage to

houses in both towns is implied by Ibn al-Athir (xii,

112).

Further north, the earthquake is said to have been

felt in Aleppo and other regional capitals (Sibt b. al-Jauzi,

478), and also in Antioch, though less strongly (Geoffrey

of Donjon). It was also reported as being perceptible

in Mosul and throughout the districts of Mesapotamia,

as far as Iraq. Azerbaijan, Armenia, parts of Anatolia

and the town of Akhlat are said to have experienced the

earthquake (Ibn al-Athir, xii, 112; Sibt b. al-Jauzi, 478).

In the south, the shock was felt throughout Egypt

from Qus to Alexandria. Sibt b. al-Jauzi (478, probably

quoting al-'Izz) says that the shock came from al-Sa'id

and extended into Syria, al-Sa'id being the region south

of Fustat (Old Cairo) down to Aswan (Yaqut, iii, 392).

In Cairo, the shock was of long duration and aroused

sleepers, who jumped from their beds in fear. Three violent

shocks were reported, shaking buildings, doors and

roofs. Only tall or vulnerable buildings were particularly

affected, and those on high ground, seemed on the verge

of collapse (`Abd al-Latif, 414-415). The details provided

indicate that Egypt experienced shaking of long duration,

as is typical of other large earthquakes occurring at great

epicentral distances away (Ambraseys 1991; 2001).

Another earthquake, probably of considerable

magnitude, was felt at about midday the same morning,

probably the one reported from Hamah at midday on

Tuesday 27 Sha'ban (21 May). It should have been a large

shock but its effects cannot be separated from those of the

main shock.

The shocks were felt in Cyprus, which had been

under Frankish rule since 1191, the earthquake causing

some damage to churches, belfries and other buildings

(Annales 5689, fol. 108b; `Abd al-Latif, 415; Ibn al-Athir,

xii, 130). Damage to buildings is not, however, very well

attested and it is noteworthy that most of the `cypriot

chronicles' refer only to damage on the mainland. In the

words of the Arabic authors, the sea between Cyprus and

the coast 'parted and mountainous waves were piled up,

throwing ships up onto the land'. It is said that the eastern

parts of the island and of the Syrian coast were flooded

and numbers of fish were left stranded (`Abd al-Latif,

415; Ibn Mankali in Taher 1979). The significance of this

seismic sea wave is discussed below.

The loss of life caused by this earthquake and its

aftershocks is difficult to estimate. A figure frequently

quoted in Arab sources is 1 100 000 dead (e.g. al-Dhahabi,

iv, 296, al-Suyuti, 47) for the year 597-598 a.H. (AD

1201-2). This specifically includes those dying of famine

and the epidemic consequent on the failure of the Nile

floods, graphically described by `Abd al-Latif, who notes

111 000 (sic.) deaths in Cairo alone between 596 and 598

a.H. (412). More realistically, the figure of 30 000 casualties

is given, primarily, it would seem, in the Nablus area

(Sibt b. al-Jauzi, 478). No reliance can be placed on such

figures, but the fact that the main shock occurred at dawn,

when most people were in bed, without noticeable foreshocks,

probably contributed to a high death toll.

Aftershocks were reported from Hamah, Damascus

and Cairo, for at least four days (`Abd al-Latif, 417;

Abu Shama, 29), one of which, apparently felt in Cairo

and Hamah, must have been a large event. There remains

the possibility that the aftershock sequence was terminated

with a destructive shock that totally destroyed what

was left of Nablus, but it seems preferable to consider

both reports by Sibt b. al-Jauzi as referring to the same

shock. Whatever the exact sequence of events, the cumulative

effects of the earthquake were clearly very serious.

Most of the sites affected in the epicentral region

must have needed total reconstruction or major repairs,

although in most cases the evidence is circumstantial, not

specific.

More information can be found in Abu Shama

(Dhayl 18v, 29r), Alexandre (1990, 170), Rohricht (1893,

1114); Alb. Mil., Amadi, Fabri, Ibn al-Furat (k. 132),

Het'um (Chron.), Ibn al-Dawadari, Katib Celebi, Mem.

Edm. Abb.; Nuwairi (118v) and Sal. Ad. 23 (see below).

In contrast to authors of earlier studies, who

assign to the event an excessive radius of perceptibility of

over 1000 km, we find that in fact the area within which

the earthquake was generally felt was confined to an area

of radius only about 500 km.

To the south and close to the epicentral area

Jerusalem suffered lightly. There is no evidence that the

shock was felt west of Cyprus, that is on Crete, the

Aegean Islands, or mainland Greece, and this during

a period for which occidental and local sources from

coastal areas are not lacking. Also the shaking reported

in and around Constantinople on or after 1 March

1202 obviously was not from the earthquake of 20 May

(Nicetas, 701 (19).

Moreover, no evidence for an earthquake has

been recovered in the western Mediterranean area. The

earthquake is said to have been felt as far away as Sicily

(Ibn al-Athir, xii, 130) and Ceuta (Ibn Wasil, iii, 161),

but this lacks confirmation in the annals of the Muslim

west, which was dominated by the Almohads during this

period.

The occurrence of a seismic sea wave between

Cyprus and the Syrian coast, 50-100 km from the epicentral

region, is difficult to understand. It may be explained

by invoking the generation of a large-scale subaqueous

slide from the continental margin of Syria by the earthquake.

North of Acre the continental shelf narrows to a

few kilometres and off the coast of Lebanon the continental

slope steepens from near Acre northwards to an

average of 10°. Under these circumstances, the principal

cause of a seismic sea wave could be submarine sliding

and slumping. The whole of that coast is certainly prone

to slumping because of evaporites in the sedimentary

section.

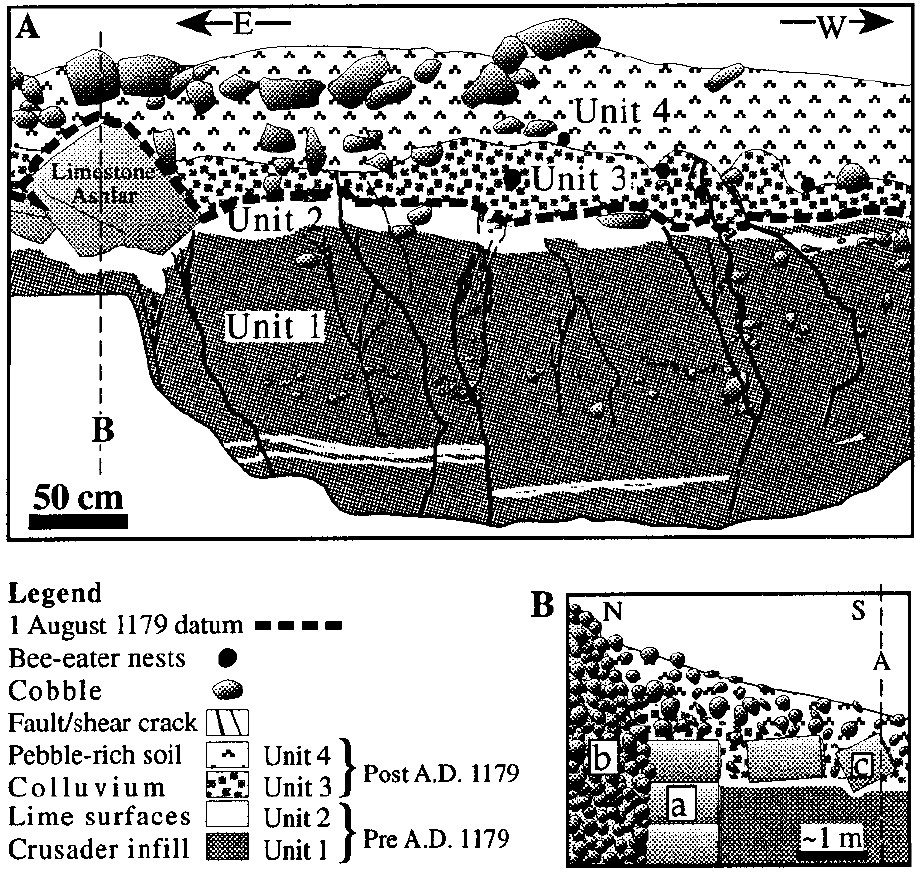

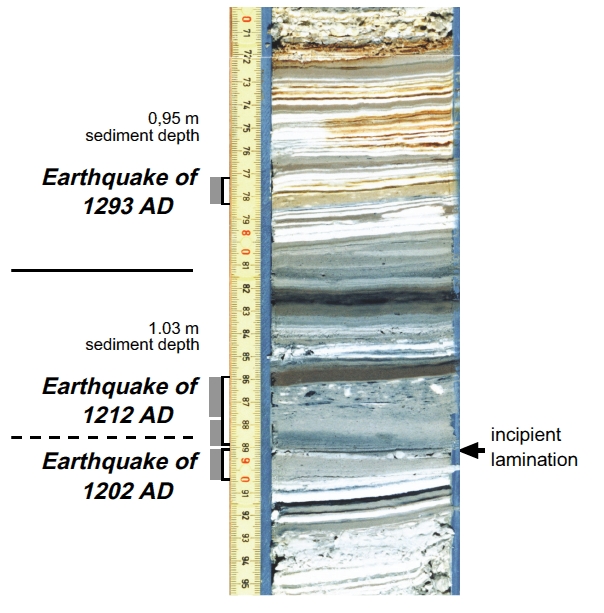

Its epicentral region, within which intensities were

high, forms a narrow inland strip about 200 km long and

40 km wide extending from Nablus in the south to 'Arca

in the north. The number of sites at which intensities can

be assessed is obviously insufficient to allow the construction

of a proper isoseismal map (but cf. Sieberg 1932b).

However, it would appear that the maximum effects of

the earthquake were experienced inland away from the

coast, in the upper Jordan and Litani valleys, as well as

the upper reaches of the Orontes river, in the vicinity

of Baalbek. Several thousand people perhaps perished in

this area. Without further details, it is difficult to indicate

more precisely the exact location of the epicentral region.

The vague details of severe damage in the Hauran district

may suggest that the rupture zone was wide. Since most of

the aftershocks were reported from the north (Hamah), it

may be conjectured that the event nucleated in the south,

near Nablus, and that it was completed by a second rupture

that originated in the Tyre-Baalbek segment of the

meizoseismal area. Apart from the statement that largescale

landslides occurred on Mt Lebanon, there is no

historical indication that this event was associated with

faulting. However, field evidence suggests surface faulting

that is perhaps associated with this and the earthquake

of 1759 (Daeron et al. 2005).

The 20 May 1202 earthquake(s) may, however, be

compared with the earthquake sequence between June

1759 and January 1760, which had almost exactly the

same epicentral region. One important aspect of the 1759

earthquake, which is much better documented, is that

it was associated with a 95-km-long fault break in the

Bekaa, on the west side of the valley, many metres wide

in places (Archives Nationales, 1759). It is not possible

to assess the tectonic effects of the 1202 earthquake,

which seems to have been multiple and comparable to

the shock of 1759 in terms of location and the extent of

faulting.

Notes

To the most excellent Lord, and most outstanding benefactor,

Sancho, by grace of God the glorious king of Navarre: from

Brother Geoffrey, humble master of the house of the Jerusalem

Hospital, with all his brethren, greetings and the fellowship of

devoted prayer. As Your Majesty's ears are no strangers to the

sorrows and miseries of the kingdom of the Promised Land, we

are reluctantly obliged to relate to Your Highness the lamentable

afflictions, which have recently occurred in that place.

While everything was silent, and night was running her

course, on the 20th day of May, which is named after the moon

[i.e. Monday], at the hour when sleep caresses tired eyes, a little

before first light, the wrath of God engulfed us, and there was

a great earthquake. Of the cities and fortresses of the East, as

well pagan as Christian, some were overthrown, some destroyed,

and others, on account of the damage caused by the shocks, were

threatened with ruin. The city of Acre, a most convenient port,

suffered an unspeakably dreadful and death-dealing blow: some

of the towers, the ornate royal palace and walls were ruined, and

there was death among rich and poor. O lamentable occurrence!

Tyre, a city of strength and a refuge of Christians, which always

freed the oppressed from the hands of evil-doers, suffered so great

an overthrow of its walls, towers, churches and houses that no

man living now could expect to see it restored in his lifetime. What

should we write about the death of the men of that city, when

death took them without number in the ruins of their homes? This

sorrow, this death, lamentable before [all] other things, and this

unfortunate event adds shudders [of terror] to our fear. The most

splendid city of Tripolis, although suffering considerable harm to

its walls and houses, and death to its citizens, underwent less of

an upheaval [than Tyre]. The towers, walls, houses and fortifications

of Arches [`Arqa] were razed; their people were killed,

and the localities are deserted: one would think that they had

never been inhabited. Our fortresses of Krak [Hisn al-'Akrad]

and Margat [Marqab] suffered considerable damage, but in spite

of the heavy shaking they received from the divine wrath, could

still hold out against enemy attacks. Antioch and parts of Armenia

were shaken by this earthquake, but did not suffer damage to

the same lamentable extent.

The pagan cities and peoples bewailed the fact that they

had received incurable wounds from this unforeseen fate. Especially

when our hearts were afflicted with so many sorrows, food

was extremely expensive, and a plague fatal to animals added further

misery to all the remaining Christians.

We also felt obliged to bring to Your Gracious Lordship's

ears that while the harvest was green, showing that an abundance

of crops was coming to us once more, a cloud overshadowed

the sprouting ears [of wheat] on the Feast of St Gregory,

so that when the crops were harvested they were found to be very

blighted: we have a surfeit of paupers and our land is afflicted

with an influx of beggars. Therefore, Lord of Virtues, most excellent

King, may the Land of the Lord's Nativity, sunk in sorrow

and misery, and almost annihilated by calamities, be revived by

your generosity, and by your counsel be comforted in her desolation.'

(Geoffrey of Donjon, in Mayer 1972, 306-308).

To his venerable father and beloved friend, by the grace

of God, the abbot general of the Order of Cistercians: Philip

de Plessis, humble master of the Knights Templar, sends greeting

trusting more in the Lord than in man, Amen. Believing in

you heartfelt concern for the good and well-being of the Eastern

Lands, it behoves me to relate to you the terrible misfortunes,

unheard-of calamities, unspeakable plagues and punishment as

of God, which has come upon us in punishment for our sins.

[First two disasters: Christian population of County of Tripoli

threatened, farmers take refuge in castles and cities; "fog" comes

down and ruins three quarters of crops.]

The third [calamity], which was more sorrowful and terrible

than the others: on the 20th day of May, at the crack of dawn,

a terrible sound was heard from heaven, and there was a dreadful

roar from the earth and an earthquake, such as has never been

from the beginning of the world, such that most of the walls and

houses of Acre were razed to the ground and a countless multitude

of the inhabitants were killed. God, in his mercy to us,

preserved our houses [i.e. those of the Knights Templar] intact.

As for the city of Tyre, all the towers except three and the walls,

except for the outer barbican, and all the houses with their people,

save a few, fell to the ground. A very large part of the city

of Tripolis collapsed, killing a great number of people. The castle

of Arches ['Arqa], with all its houses, walls and towers was fattened,

and the castle of Arsum [Arima?] was razed to the ground.

Most of the walls of Chastel Blanc [Safitha], and the larger tower

[of the latter], which we believed was surpassed by none in the

strength and compactness of its construction, was weakened by

cracks and shaking: it would have been better for us if it had collapsed

totally, than remained standing in that condition. The city

of Tortosa [Tarsus], however, and its fortress with its towers and

walls and people and all was preserved by divine mercy. [Fourth

calamity: plague] [Valedictory]' (Philippe de Plessis, in Mayer

1972,308-310)..

(1202) In that year there was a great earthquake in Syria,

in which cities and towns were engulfed.' (Sal. Ad. 23).

(a.1202) There was a great earthquake which ruined

Acre, Tyre, Giblet, Arzer and a great part of Tripolis, together

with many other lands of the Christians and infidels.' (Amadi,

91f.).

In 1202 there was a great earthquake which struck Acre,

Tyre, Gibelet and Arches, and several other cities.' (Annales

6447).

The region of Outremer was afflicted by a great disaster:

on 20th May, around daybreak, a terrible sound was heard

in the sky and an awful rumble from the earth, and there were

earthquakes so violent that the most part of the city of Acre, with

its ramparts, houses and even the royal palace, was razed to the

ground, and countless persons were wiped out. Similarly the city

of Tyre, the most [strongly] fortified in those parts, was almost

completely overturned, while all of its towers bar three collapsed,

and the ramparts, as high as they were solid, were either badly

damaged or almost thrown to the ground, except for some forewalls

which they call barbicans; all the houses and the buildings,

with a few exceptions, were shaken. Likewise in the region

of Tripolis the castle of Arqa, a great fortress, was razed to the

ground with its towers, ramparts, houses and people. A great part

of the city of Tripolis fell too, and many people were killed. Similarly

most of the ramparts and towers of Chastel-Blanc [Safitha]

were thrown to the ground. There were few coastal cities which

did not suffer some damage: the city of Antaradus, which is also

called Tortosa, escaped this disaster unharmed and intact.' (Rob.

Aux. 264).

And in this year [a.H. 597/1200] there was great scarcity

in Egypt, for the Nile did not overflow according to custom. And

men ate the bodies of dead animals and also of men. And then

pestilence followed upon famine closely. And there was also an

earthquake and it destroyed many buildings and high walls in

Damascus, and Emesa, and Hamath, and Tripoli, and Tyre, and

Akko, and Shemsin [Samaria], and it reached Beth Rhomaye,

but it was not violent in the East.' (Abu'l-Faraj 351/407).

There was a great earthquake in Tyre, on the 3rd [ ]'

(MS Barletta, Kohler 1901, 42/401).

1203. There was an earthquake in almost all of Palestine,

overturning cities and houses.' (Ann. Uticenses, see also Alexandre

1990,170).

In that year [1202] a great earthquake happened in the

land of Jerusalem, such as has not occurred from the Lord's Passion

until now: for almost the whole of Tyre, that famous city, was

overthrown with its inhabitants, and a third of Ptolemais, that is

Acre, with its castle and towers, and other castles were also overthrown,

as many in the Christian territory as in that of the Saracens.

This particular earthquake even affected several places in

England.' (Cogg. 141-142).

In 1202 there was a great earthquake which demolished

many houses in Acre, Tyre, Giblet, Tripoli, Arches, and many

other houses belonging to the Christians and Saracens.' (Gestes

Chypr. RHC 59/663).

. . . earthquakes occurred in the land and brought down

the walls of Tyre, Beirut and Acre, much of which was rebuilt.'

(Ernoul, 31).

. . . there were earthquakes: they broke down the walls of

Tyre and Acre, which were [partly (MS difference: see 245 n. 6)]

rebuilt.' (Estoire 244-245).

[30 March 1202] There was the greatest earthquake ever

seen in Syria. The city of Acon, with all its palaces and many other

buildings, was overthrown, and a similar fate befell many other

cities.' (Fabri, i. 283b/ix. 350).

(a.Arm. 651) Second earthquake. A large number of

cities were overturned on the Sahel [littoral].' (Het'um Chron.

480).

In 1202 the violent earthquake happened which

destroyed Ak'a, Sur, ?plet', Arka and the great part of Trapawl

[Soy], and many other cities.' (Het'um Pat. Het. Chron. n. 61).

AD 1202 . . In the same year there was a great earthquake

in Syria, in which cities and towns were engulfed; and virtually

the whole city of Tyre collapsed . . .' (Alb. Mil. 654).

(1202) On the 30th day of May there was an earthquake

in Outremer, three days before the Ascension of the Lord, and

a terrible sound was heard: a great part of the city of Acre collapsed

with the royal palace, and many people died, almost all

of Tyre was overthrown and Arches, a very well fortified town,

was razed to the ground. Most of Tripolis collapsed, and a great

many people died. Ancharadus ... came out of it unscathed. And

after this the land was barren, and many people died.' (Will.

Nang.).

God showed himself to be [the] master of hours and

times, and that he either speeds or hinders the journeys of men,

for the floor by the Emperor's bed gave a little and a crack of

considerable size opened in it. The emperor surprisingly escaped

this danger . . (Choniat Bonn 701).

Hence we reached Famagusta, a city built close to the

sea, with a good harbour, slightly fortified. Here is the third suffrage

see of the lord bishop of Nicosia. Near it is the site of the

same city now destroyed, from which, they say, came that famous

and blessed Epiphanius (Wilb. Old. xxvii/180/Excerpta 14).

`(1202) A great and terrible earthquake occurred in the

Land of Jerusalem.' (Mem. Edm. Abb. 11).

On Monday 26th Shaban, which was 25th Pashons,

early in the morning, a violent earthquake was felt which caused

terror among men. Seized with terror, everyone leapt down from

his bed and cried out to the all-powerful God. The shaking lasted

for a long time: the shocks were like the movement of a sieve,

or like that of a bird lowering and lifting its wings. In all there

were three violent shocks, which shook buildings, caused doors to

tremble and roof-joists to crack: [these shocks] threatened to ruin

buildings in poor repair or on an elevated or very high site. There

were further shocks around midday of the same day; but only a

small number of people felt them, because they were weak and did

not last long. On that night there was extreme cold, which obliged

one to cover up more than usual. This was followed in the day by

extreme heat, and a violent, pestilential wind which stopped people's

breathing and suffocated them. It is rare for Egypt to suffer

an earthquake as violent as that.

Then we received news, which had passed from one to

another, that the earthquake was felt at the same time in far countries

and in very distant cities. I think that it is most certain that at

the same time a great part of the earth felt the shock, from Qus as

far as Damietta, Alexandria, the sea coast of Syria, and the whole

of Syria in its entire length and breadth. Many settlements disappeared

totally without leaving the slightest trace, and an innumerable

multitude of men perished. I know of not a single city in

Syria which suffered less in this earthquake than Jerusalem: this

city sustained only very slight damage. The ravages caused by this

event were far greater in the regions inhabited by the Franks, than

in the Muslim territories.

We have heard it said that the earthquake was felt as far

as Akhlat and in the neighbouring districts, as well as on the

island of Cyprus. The rising of the sea and agitation of the waves

was a most terrible sight to behold, something quite unrecognisable:

the waters parted in diverse places, and divided up into

masses like mountains; boats found themselves on dry land, and

a great quantity of fish was thrown on to the shore.

We also received letters from Syria, Damascus and

Hamat, which contain details of this earthquake. I personally

received two, which I will report in exactly the same way as that

in which they were written..

Copy of the letter from Hamat

On Monday 26th Shaban, in the early morning, it was as

if the earth had moved and the mountains were being agitated in

different ways. Everyone imagined that this was the earthquake

which should precede the Last Judgement. The earthquake was

felt twice on that day: the first time it lasted about an hour; the

second shock was not so long, but stronger. Many fortresses were

damaged by it, among which was the fortress of Hamah, in spite

of the solidity of its construction; that of Barin, even though it

was tightly furbished and light, was also damaged, as well as the

fortress of Baalbek, notwithstanding its strength and firmily.

As yet we have received no news to give from the cities

and fortresses far from here.

On Tuesday 27th of the same month, around the time

of midday prayer, there was another earthquake which was felt

by all men, whether awake or asleep; we suffered another shock

on the same day at the time of afternoon prayer. From the news

which we then received from Damascus it was learnt that the

earthquake destroyed the eastern minaret of the great mosque, the

largest part of the building, called the Kallaseh, and the entire hospital,

together with many houses which fell on their inhabitants,

killing them..

Copy of the letter from Damascus

"I have the honour to write to you-this letter, to inform

you of the earthquake which took place during the night of Monday

26th Shaban, at the break of dawn, and which lasted for quite

some time. One of us said that it lasted long enough to read the

surat of the Koran entitled 'The Cavern'. One of the oldest men

of Damascus attests that he had never felt anything equal to it.

Among other damage caused by it in the city, sixteen crenellations

of the great mosque and one of the minarets fell; another was split,

as well as the leaden dome. The building called the Kallaseh was

swallowed up, as the earth was open, and two men died; a man

also died at the gate called the Gate of Jirun. There were several

cracks in diverse parts of the mosque, and a great number of the

city's houses fell.

The following details were reported to us regarding the

countries occupied by the Muslims. Paneas and Safet were partly

overthrown; in the latter town only the son of the governor sur-

vived. Tebnin suffered the same fate. In Nablus not a wall remains

upright, except in the Street of the Samaritans. It is said that

Jerusalem, thanks be to God,, has suffered nothing. As for Beit-

Jan, not even the foundations of the walls remain, everything having

been swallowed up in the ground. Most of the cities in the

province of Hauran have been destroyed, and of none of them can

it be said, 'Here was a certain town'. It is said that the greater part

of Acre has been overthrown, as well as a third of the city of Tyre.

Irka and Safith have been swallowed up. On Mt Lebanon, there is

a defile between the two mountains where people go to pick green

rhubarb: we are told that the two mountains came together and

swallowed up the men who were there, numbering almost 200.

In all, many things are said about this earthquake. On the four

days following shocks continued to be felt day and night."' (`Abd

al-Latif, r.e. 262/414).

(a.H. 597) ... 30 000 victims were buried under the ruins

and Acre was destroyed together with Tyre and all the coastal

citadels. The earthquake spread as far as Damascus and caused

the exterior minaret of the mosque to fall, as well as the greater

part of al-Kalasa, and the Baymaristan of Nureddin. Most of the

houses in Damascus were destroyed, with few exceptions. People

fled to the square, sixteen of the crenellations fell from the

mosque, and the dome of Nasr split in two before men's eyes.

Walkers had left Baalbek to pick currants in the mountains of

Lebanon, and the two mountains closed over them and they were

wiped out. The citadel of Baalbek was destroyed in spite of its

careful construction.

The earthquake also spread towards Homs, Hamah and

Aleppo, and all the capitals. It tore through the sea towards

Cyprus and there were some very high waves, [as a result of

which] boats were driven on to the shore and shipwrecked. The

earthquake continued in the direction of Akhlat and Armenia,

Azerbaijan and al-Jazirah. The number of victims in that year

reached I 100 000 men and it lasted for the time taken to read

the Surat al-Kahf, then there was a succession of further shocks.'

(Sibt ibn al-Jauzi, Mir'at 8/331).

(a.H. 598) In the month of Sha'aban a prodigious earthquake

took place and Homs was destroyed with its citadel, and

the watchtower which also dominates Hisn al-Akrad. The earthquake

spread as far as Cyprus, Nablus and the neighbouring

regions.

This earthquake affected three of the coastal cities, viz.

Tyre, Tripolis and `Araqa, and it caused considerable destruction

in the Muslim territories in the north. It was felt as far as Damacus,

where it shook the tops of the minarets of the mosque, and

several crenellations of the north wall.

A maghrebin was killed at Kalasa and also a Mamluk

Turk, [the latter] a slave of an official who lived in the

Street of the Samaritans: this occurred at daybreak on Monday

26th Sha'aban (20th Ab in the Syrian calendar). The earthquake

lasted until the following morning.' (Sibt ibn al-Jauzi, Mir'at 8/

331).

(a.H. 599/20 September 1202] At the beginning of

Muharram, on the night of Saturday, shooting stars appeared

in the sky, from the east to the west: they looked like locusts

spread from right to left. Such a phenomenon had never been

seen, except at the birth of the Prophet, then in a.H. 241 and 600.'

(Sibt ibn al-Jauzi, Mir'at 8/333).

In the month of Sha'aban of that year the earth shook in

the country of al-Jazirah, and of Sham, Egypt, and other regions

too. The catastrophe was terrible, with the destruction reaching

as far as Damascus, Hims, Hamat and the village; the village of

Busra also collapsed. The Syrian littoral was the worst affected,

with destruction in Tripoli, Tyre, Acre, Nablus and other cities.

The earthquake went as far as the country of Rum [i.e. the Byzantine

borders]; the area least damaged was Iraq, where no houses

were destroyed.' (Ibn al-Athir, al-Kamil 12/110).

At dawn on Monday 26th Sha'aban (25 Bachans) there

was a prodigious earthquake. People were very agitated, leaping

from their beds in great surprise, and calling on God (Subhana).

The cataclysm continued for a long time: one might say that it was

like the shaking of a sieve, or even the beating of a bird's wings. It

stopped after three or four strong shocks: buildings shuddered,

doors banged, roofs creaked and poorly constructed buildings

collapsed. Then it started again on Monday at midday. Not everyone

felt it this time because the shock was weak and brief. The

night was very cold and one had to cover up, which was unusual.

And in the morning, the cold had changed into an extraordinary

heat, and a wind of Sumun got up, so strong that it prevented one

from breathing, and even the most hardy endured it with difficulty.

An earthquake of such force has rarely occurred in Egypt.

News spread by word of mouth of an earthquake at the

same time in distant regions. And, what interests me is that at

the same hour the earth had shaken at the same time in Damietta,

Alexandria, in all the coastal regions and all over Sham.

Cities were ruined, some to the point that they disappeared without

trace. Peoples in great numbers and countless nations were

wiped out: I knew a city, as securely founded as Jerusalem, which,

however, suffered damage such as one would never have foreseen.

The Frankish possessions were worse affected by this earthquake

than those of the Muslims. We have heard it said that this

earthquake was felt as far as Akhlat and its frontiers and as far as

the island of Cyprus. The sea was turbulent and lighthouses suffered

considerable damage. The waters parted and waves came

up like mountains. Boats were grounded and wrecked, and many

fish were thrown up on to the shore.

Messages were received from Damascus and Hamat

announcing [the occurrence of] the earthquake. Here are two

which I have held in my hands and which I have transcribed

[here] word by word:

On 26th Shaaban an earthquake occurred and it was

almost as if the earth had begun to walk; the mountains opened

and everyone thought that this was the Last Hour. There were two

shocks: the first lasted an hour or a little more, and the second

was not as long; but more violent. A few citadels were affected:

the first, Hamat, suffered in spite of the quality of its buildings, as

did Barin, even though it was solid and finely built, and Baalbek

too, notwithstanding its robust strength.

We have received no precise information to mention on

neighbouring countries and citadels. On Tuesday 27th of this

month, at midday, there was an earthquake which everyone felt,

both those who were asleep and those who were awake. Everyone

was shaken, whether standing or sitting. Another shock occurred

too, after afternoon prayer!

We have received from Damascus the following news,

according to which the earthquake had damaged the Eastern

minaret of the mosque and the most part of the Kallasats as well

as the entire hospital (Baimaristan). Several houses had collapsed

on their inhabitants, who were killed. Here is the text of the message:

Thus speaks the Mamluk: An earthquake occurred during

the night of Monday 26 Shaaban at dawn and it lasted for

some time. Some of his aides reckon that [it lasted long enough]

to read the Surat al-Kahf.

Someone from Machaikh in Damascus said that he had

never seen such an earthquake before.

The damage extends as far as the cemetery, and includes

16 crenellations of the mosque, one minaret (the other is cracked),

the lead dome called Nast the Kallasat, which collapsed killing

two men; another man was killed on the gate of Jirun, and there

was widespread destruction in many places, [including that of]

many houses.

The Muslim territories were affected: part of Banyas,

Safad, where only the sons of the governor survive.

Tibnin too, and Nablus, of which only one wall and

Samosata street remain standing.

He stipulates that Jerusalem was spared by the grace of

God.

As for Bayt Jin, only the foundations and the walls

remain, and even then they have crumbled. The country of Huran

has collapsed and one cannot recognise the sites of its villages.

A large part of Acre has been destroyed, and 30 per

cent of Tyre and `Arqa have collapsed: ditto in Safitha. On

Mt Lebanon people had gone out to pick green currants [gooseberries?],

and the mountain collapsed on them. There were nearly

200 victims. People spoke much of this.

For four [days and nights] after this we prayed to God

to protect us. He is our safety and our surest protector.

(Abu'l-Fida al-Mukht. 262-2'70).

(a.H. 600/1203) In that year there was an earthquake in

most countries: Egypt, Sham, Jazirah, the land of Rum [Byzantine

Empire], Sicily and Cyprus. It reached Mosul and Iraq, and

other countries as well. Among the [places] which were ravaged,

the walls of Tyre and most of Sham were very [badly] affected.

The earthquake spread as far as Sebta, in the country of Maghreb,

with the same effects.' (Ibn al-Athir, Kamil xii/198; Ibn al-Wardi;

Tatimmat, 2/122).

[There was] a great earthquake in the Islamic lands.'

(Katib celebi, Takvim, 76).

In that year [a.H. 597] there was a great earthquake in

the month of Shaban [April-May 1201]. It came from the direction

of Upper Egypt and spread over the world in a single hour.

Buildings in Egypt were destroyed and many people disappeared

under the destruction. It reached Syria and the coast, and Nablus

was destroyed: only the walls of the Sumrah quarter were left

standing. 30 000 people perished under the rubble. Likewise Akka

and Tyre were destroyed, along with the fortresses of the coast. It

encompassed Damascus: some of the minarets of the Umayyad

Mosque were destroyed, and most of al-Kallasah and the Nuri

hospital. The people fled to the public spaces. Sixteen galleries fell

from the mosque. The Qubbah al-Nasr split. Banyas and Hunayn

suffered as well. A group of people from Baalbek, travelling on

the road, were buried under a mountain landslide and perished.

Most of the citadel of Baalbek was destroyed. Homs, Hama,

and Aleppo were affected. [The earthquake] crossed the sea to

Cyprus. The sea split and rose like a mountain, hurling ships

on to the shore and breaking up a number of them. It reached

Akhlat, Armenia, Azarbayjan, and al-Jazirah, and also Ajarn.

It was said that thousands or 100 000 perished under the rubble.'

(Ibn al-Dawadari, vii. 149-150).

(a.H. 598) In Shaban [April-May 1202] the earthquake

returned. It destroyed what remained of Nablus. The citadel

of Homs was cracked. It destroyed Hisn al-Akrad. Its effects

reached Cyprus.' (Ibn al-Dawadari, vii. 153).

(a.H. 600/1203-4, quoting from Ibn Wasil] In this year

there was a great earthquake which encompassed Egypt, Syria

and Rum as far as Sicily.' (Ibn al-Dawadari, vii. 158).

bn al-Jauzi has said in his al-Mieat that in the month

of Shaban of [5198 [26 April to 24 May] a very violent earthquake

occurred which split [n. 334; B text has 'tomba'] the citadel

of Hims and caused the observatory of the same to collapse; it

razed Hisan al-Akrad and reached Naplus, destroying everything

which had remained there (ce qui avait subsiste). (Ibn al-Jauzi,

al-Mirat, 8/311).

References

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.