Left - Various political states in 1200 CE (wikipedia- ExploretheMed - CC BY-SA 3.0)

Right - Hypothetical Intensity map for 1202 CE Earthquakes on the Lebanese Restraining Bend (from Fig. 4 Hough and Avni , 2011).

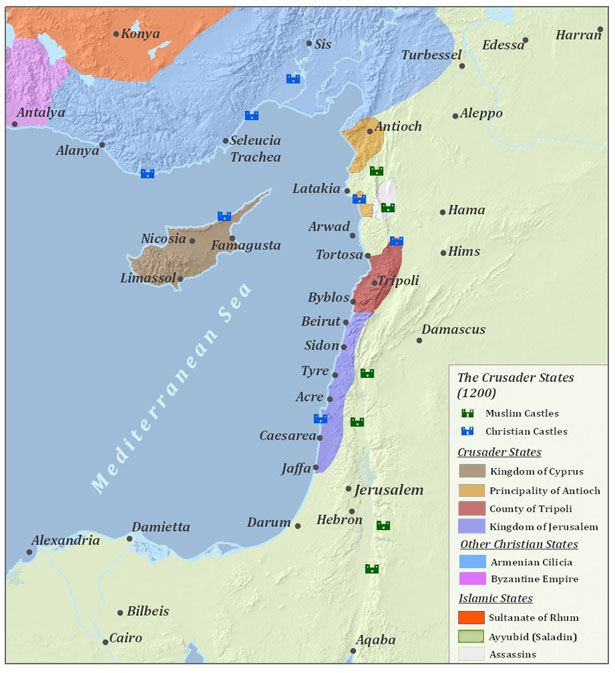

Shortly before the Fourth Crusade, a powerful earthquake struck a vast region encompassing Egypt, Cyprus, and the Levant at daybreak on 20 May 1202 CE. The event is documented by both Western and Muslim sources, several of whom were contemporary eyewitnesses. Letters written about a month later by Geoffrey of Donjon and Philipe Du Plessis describe an earthquake that struck at or just before dawn, devastating Acre, Tyre, Tripoli, Arqa, Krak, Margat, Arsum, and Chastel Blanc. A later account by Robert of Auxerre repeats much of the information provided by Philipe du Plessis.

Ibn al‑Latif al‑Baghdadi experienced the earthquake in Cairo and wrote about it approximately two years later. Like Geoffrey of Donjon and Philipe du Plessis, he described a powerful shock that struck in the early morning. As with several other Muslim authors, the date he recorded in the Islamic calendar corresponds to 21 May 1202 CE; however, he also provided a date in the Coptic calendar equivalent to 20 May 1202 CE. In addition, he noted that the earthquake occurred on a Monday—yet 21 May 1202 CE fell on a Tuesday, whereas 20 May 1202 CE fell on a Monday. This confirms that the correct date for the main shock was 20 May 1202 CE and suggests that the Islamic calendar in use at the time differed slightly from the modern one.1

Al-Baghdadi reported that the initial early morning shock in Cairo consisted of three violent tremors and lasted a long time. It was followed by a weaker shock around midday. In letters he reproduced from Hamat (Hama) and Damascus, the first shock was described as striking at dawn or in the early morning. In Hamat, the initial tremor was said to have lasted an hour, followed by a second that was shorter in duration but stronger in intensity—perhaps a triggered earthquake nearer to Hama. The time of this second shock was not specified. In Damascus, the first shock was also said to have lasted a long time; one observer claimed it endured as long as it takes to recite Surat al-Kahf, roughly thirty minutes. The Damascene historian Abu Shama, born about a year after the event, wrote that “for an hour the ground was like the sea.” Accounts describing shaking lasting between half an hour and an hour likely refer to the main shock followed by a sequence of powerful aftershocks or secondary triggered earthquakes. Sibt ibn al‑Jawzi, who experienced the earthquake in Damascus, stated that the initial tremor lasted about forty-five seconds—“as long as it took to read” Surat al-Kafirun. Among the Muslim authors, several report aftershocks that continued for up to four days, and four Western accounts2 describe multiple earthquakes rather than a single event. This pattern probably reflects continuing aftershocks or a cluster of triggered earthquakes. The widespread destruction across Egypt, Lebanon, Cyprus, and Syria; the near-simultaneous occurrence around daybreak in Cairo, Damascus, and Hama; and the reports of multiple violent shocks together suggest that two or more fault ruptures were triggered within a short interval—minutes or hours. Shocks recorded a day or more later may indicate additional events. Ambraseys (2009) noted that this pattern resembles the triggered sequence of the Baalbek earthquakes of 1759, which occurred about a month apart.

The reports that strong shaking was felt in Egypt (including Cairo) while Jerusalem was spared major damage are intriguing. This can likely be explained by the fact that al-Baghdadi did not mention any building collapses or fatalities, indicating that Egypt experienced intense shaking but avoided catastrophic damage—similar to Jerusalem. If, however, later writers who describe widespread destruction and casualties in Egypt are correct3, this might suggest the occurrence of a secondary fault rupture farther south, perhaps in the southern Gulf of Aqaba or the Red Sea region.

The death toll reported for the 1202 CE earthquake was exaggerated by several authors. For example, Sibt ibn al‑Jawzi claimed that 1.1 million people perished. While the number of casualties was undoubtedly high, it is impossible to estimate accurately, as the earthquake struck during a time of widespread crisis—when a deadly plague was spreading and the Nile’s failure to overflow had led to famine. Several Muslim authors also described a tsunami, usually said to have struck the western, Crusader-controlled island of Cyprus. This tsunami may have resulted from an offshore slope failure, and it may likewise have impacted the Lebanese coast, though neither Muslim nor Western sources provide clear accounts of such a wave there.

In addition, several Muslim chroniclers mention a landslide that reportedly killed many people in the mountains outside Baalbek. Numerous contemporaneous and local Muslim sources give detailed descriptions of destruction in Damascus, including damage to the Great Mosque of Damascus. Sibt ibn al-Jawzi, who lived in Damascus at the time, described residents fleeing into the public square—an instinctive response to powerful earthquakes. Such eyewitness details lend credibility to his report and suggest that many people remained outdoors, fearful or unable to re-enter their damaged homes.4

Older earthquake catalogues misdated or duplicated the event, assigning it to the years 1201, 1202, 1203, or 1204 CE. These inconsistencies likely stem from erroneous dates in the medieval sources. A close analysis of the earliest accounts, however, provides an unambiguous date: 20 May 1202 CE. Nonetheless, duplicate dates in some chronicles5 could indicate the occurrence of a powerful foreshock, aftershock, or triggered earthquake separated by months or even years from the main event.

Descriptions of the damage cover a wide geographic area, which tends to expand in later sources written further in time from the event. According to the earliest writers, Jerusalem, Iraq, Antioch, Armenia, and Tortosa were spared or suffered only minor effects. These earlier, more conservative reports should be given greater weight. The collapsible panel titled “Areas Affected” lists localities mentioned in the earliest accounts. There is both paleoseismic evidence (e.g., the Kazzab Trenches and Bet Zayda) and archaeoseismic evidence (e.g., al-Marqab Citadel, Chastel Blanc, and Tel Ateret) supporting earthquake activity from this period. Paleoseismic evidence from the southern Araba dated to around this time has often been attributed to the earthquakes of 1068 or 1212 CE, though a connection to the 1202 CE event cannot be excluded.