Tel Ateret/Vadum Jacob

Aerial Drone shot of fortress at Tel Ateret, view from the north

Aerial Drone shot of fortress at Tel Ateret, view from the northClick on image to open a high res magnifiable image in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tel Ateret | ||

| Metzad ‘Ateret | Hebrew | מצד אטרט |

| Vadum Jacob | Crusader | |

| Vadi Iacob | Latin | |

| Vadum Iacob | Crusader | |

| Chastellet | Crusader | |

| Le Chastelez | 13th century CE | |

| Bayt al-Ahzan | 12th century CE Arabic | بايت الأهزان |

| al-mashhad al-yaʿqūbī | Arabic | |

| makhāḍat al-aḥzā | Arabic | for the Ford - not the castle |

| Qasr al-'Ata | Modern Arabic | قاسر الء'اتا |

| Qasr al-'Atara | Modern Arabic | قاسر الء'اتارا |

| Kaiser Attrah | Anglicized Arabic ? |

Tel Ateret is situated atop a structural high that oversees a crossing of the Jordan River. It's military/strategic value has led to multiple occupations which

from bottom up include an Iron Age II fortification, a Hellenistic Complex, a medieval Crusader Castle known as Vadum Jacob, and

the last structure - a Mumluk and Ottoman pilgrimage site with a mosque (

Ellenblum, et al, 2015). The Hellenistic settlements dating from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BCE may have been Pharanx Antiochus captured by Hasmonean

King Alexander Jannaeus in 81 BCE

(Ellenblum et. al., 2015

citing Ma'oz, 2013). In some traditions (e.g. 12th century Muslim), the site was associated with the dwelling place of the Biblical Patriarch Jacob

when he learned of the disappearance of his son Joseph (

Ellenblum, 2003). Structures built on the site straddle the active Jordan Gorge Fault thus providing a unique location to resolve slip from earthquake events.

Note: Some papers refer to the fault intersecting the structures as the Dead Sea Fault (DSF). This refers to the Jordan Gorge Fault (JGF) segment which is one of several large active faults

comprising the Dead Sea Transform.

- from Marco (2009:35-38) citing Ellenblum (1998)

Vadum Jacob dominated the only crossing of the Jordan River south of the Hulah swamps and north of the deep Jordan canyon. The site is a day’s walk from Damascus and half day, according to Al-Muqadasi, from Tiberias or Safad.

The castle was built above the west banks of the River Jordan in the place commonly called “Jacob’s ford”. According to the 13th century Frankish chronicler Ernoul, the place was in the Muslim and not in Frankish territory. The Franks built their castle because they wanted to weaken the most vulnerable part of the Muslim’s frontier.

The other possible crossing from Syria to Palestine north of the Sea of Galilee was near the city of Banyas, which was held by the Muslims. It is also possible that Vadum Iacob was even planned to threaten the Muslim center of Damascus.

The King (which king?) made a general call to arms, gathered the whole army in Vadum Iacob and stayed there from the beginning of October, 1178 until the second week of April, 1179. The beginning of the works in October might be attributed to climatic considerations as the heat in the upper Jordan Valley from June to the end of September is unbearable. The temperatures decrease considerably in October. The rainy seasons also starts by the end of October and the rains reach their peak in December, January and February. This schedule left the builders with two months of intensive work in mild weather before the beginning of the rainy season.

William of Tyre stresses that the construction of the castle was already completed when the king left for Jerusalem in the beginning of April, 1179. In other words, he claims that the monumental castle was finished after only six months of work. William was not an eye-witness, since he had left the country several months earlier on his way to Rome, but he also writes that in mid-April 1179, following a battle between Franks and Muslims near Banyas, the Franks carried the dying Constable, Humphrey of Turon, “to the new castle which was still under construction.” This statement was interpreted as proof that the castle was not finished when the king left for Jerusalem.

Our excavations reveal that the construction of the castle was not completed at the time of its destruction in August, 1179. Remains of construction works were excavated throughout the castle. We unearthed a complete inventory of medieval working tools: spades, hoes, picks, a wheelbarrow, plastering spoon, scissors, etc. A dramatic find adjacent to one of the gates was a heap of lime with working tools imbedded in it, which was covered by Muslim arrowheads. That clearly demonstrates how the builders where interrupted by the sudden attack.

A similar discrepancy is found in the description of the construction of the castle of Safad, which was built between 1240 and 1260. Benoit, the Bishop of Marseille wrote that when he left the site, after less than six months of work, the castle was already finished, and was in a defensible state. However, when he himself returned there 20 years later, he was impressed by the outer wall, which was added to the castle since his first visit. He himself does not explain how a castle can be “finished and in a defensible state” while the outer wall was only added later.

We can assume that the construction of the inner curtain wall was completed by then, and the four hot months of summer were devoted to improving the conditions of life inside the castle and to preparing for an intensive building season, planned, without doubt, for the cool autumn and winter months.

According to Ibn Abi Tayy, [as quoted by Abu Shama] Salah al-Din tried to buy the castle from the knights Templars and negotiated possible terms. The Franks, so it seems, were willing to consider the destruction of the castle if the Muslims paid the estimated cost of its construction. The Sultan offered 60,000 dinars and was even willing to offer 100,000 dinars because “the Templars provided it generously with garrison, provision and arms of all kinds”. Salah al-Din promised his men to destroy the castle by himself, once it was taken.

It seems that Salah al-Din was reluctant to challenge the entire Frankish army and dared to attack only when the army was no longer present. He visited the site immediately after the departure of the king in April 1179, accompanied by a representative of the Khalif, Qadi al-Fad’il. He probably considered the advance of the works, weighing the possibilities of taking it by force, or buying it. Immediately after the failure of the negotiations, in May 16th 1179, Salah al-Din attacked the site for the first time. He stayed there for five days and failed to take it by surprise.

The decisive attack on the castle commenced on Saturday, 19th Awal, 575\August 24th 1179, the Muslim forces being commanded by Salah al-Din himself and his best generals. Salah al-Din realized that it will be difficult to take the castle by assault and opted for digging under the walls. The result of the first attempts was very poor. The tunnel was 30 feet in depth and 3 feet in width, whereas the width of the wall was 12 feet. The timber that supported the tunnel was set on fire but the wall did not collapse. Salah al-Din was in a hurry; he could not wait for the fire to be extinguished gradually. He therefore promised a dinar for every skin full of water, which will be poured onto the flames.

When the fire was extinguished and the sappers dug to a deeper and wider tunnel, which they set on fire once again on Wednesday. Finally, on sunrise, Rabi’ I 575 [=29 August 1179], the Muslim sappers succeeded in breaking through the walls which collapsed to the applause of the Muslims. The Franks erected a temporary timber wall, but strong wind strengthened the flames and the tents, timber and many of the Frankish warriors caught fire. The Muslim sources describe in amazement how the commander of castle jumped into the flames. The rest of the Franks asked for surrender terms.

The Muslim armies entered the castle killing many of the Frankish marksmen and taking many captives. Saladin took the armors of about 1000 knights and sergeants, 100,000 weapons and many animals as booty. The captives were led to Damascus.

The Muslim soldiers then destroyed the castle and threw the corpses of the defenders into a deep cistern. This last careless operation was probably the cause of a plague, which started within 3 days of the conquest. Saladin and his men left the site on their way to Damascus. The Frankish army in Tiberias saw their fortress caught ablaze and covered with deep smoke.

- Figure 1b - Location Map

from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 1b

Figure 1b

Location of Ateret on the trace of the Jordan Gorge Fault between the basins of the Hula and the Sea of Galilee. Solid lines mark strike-slip faults; gray lines mark faults at subsurface according to Schattner and Weinberger [2008] and Politi [2011]. Dotted lines mark normal faults. Black arrow west of Ateret shows the location of paleomagnetic declinations and geo-chronology studies of basalt flows that found counterclockwise block rotations about vertical axes of 11.4° ± 4° per million years [Heimann and Ron, 1993].

Base map:GMRT

Ellenblum et al (2015) - Figure 3.1 - Road Map

from Raphael (2023)

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1

The three roads that crossed the Golan Heights and led to Damascus via:

- Banias

- Jacob’s Ford

- Qaṣr Bardawīl (Wadi ʿAlʿāl

(Map by Shai Scharfberg)

Raphael (2023) - Fault Map and Geologic Map

of Tel Ateret area from Vadum Jacob Research Project website.

Left

Left

Dead Sea Transform zone in the study area, showing main faults (solid lines) and secondary, mostly normal, faults (slim lines).

(partly after Bartov, 1979)

Right

Geologic map of Ateret area showing Pliocene to Pleistocene basalt flows with K-Ar ages (Goren-Inbar and Belitzky, 1989; Heimann and Ron, 1993) , Quaternary lacustrine sediments of Gadot and Benot Ya’akov Formations, and Holocene alluvium (partly after Belitzky, 1987)

Vadum Jacob Research Project website - Figure 18.7 - Hypothesized

fault traces from the 1759 CE Safed and Baalbek Earthquakes from Raphael (2023)

Figure 18.7

Figure 18.7

The settlements mentioned by the Damascene chronicles as being struck by the double 1759 earthquake and the assumed rupture zones of the earthquakes. The orange line traces the 25 November mainshock extent, 100 km. long, inferred from the report of the French Consul to Saida.

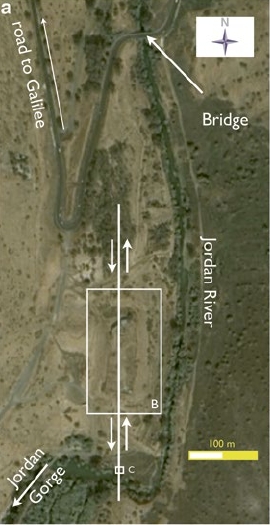

Raphael (2023) - Figure 8.5a - Annotated

Satellite photo (Google Earth) of Tel Ateret – Benot Ya’aqov bridge from Agnon in Garfunkel et al (2014).

Fig. 8.5a

Fig. 8.5a

A satellite photo (Google Earth) of Tel Ateret – Benot Ya’aqov bridge. Vadum Iacob castle straddles the fault trace, that runs through an aqueduct system south of the castle.

JW: White box labeled B encompasses the archaeological site

Agnon in Garfunkel et al (2014) - Annotated Satellite Photo

of Tel Ateret and environs from BibleWalks.com.

- Figure 4.8 - Aerial View

of fortress from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.8

Figure 4.8

Looking southwest, a stretch of the eastern curtain wall

Raphael (2023) - Aerial view of fortress

at Tel Ateret from BibleWalks.com

Aerial Drone shot of fortress at Tel Ateret, view from the north

Aerial Drone shot of fortress at Tel Ateret, view from the north

Click on image to open a high res magnifiable image in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Figure 4.2 - Aerial

View of Tel Ateret from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.2

Figure 4.2

The fortress at Jacob’s Ford

(photo: Itai Hinch SAR Unit Me’voot Ha’hermon)

Raphael (2023) - Tel Ateret in Google Earth

- Tel Ateret on govmap.gov.il

- Figure 4.10 - Site Plan

from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.10

Plan of the Templar fortress at Jacob’s Ford The Mamluk–Ottoman mosque is shown in green The capital letters indicate the excavation areas

(plan renewed by Jay Rosenberg)

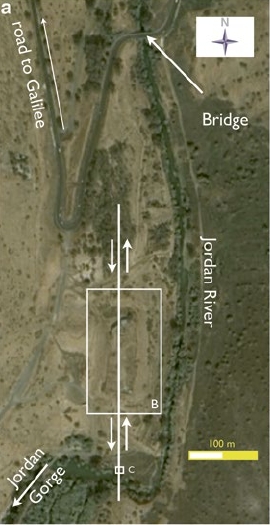

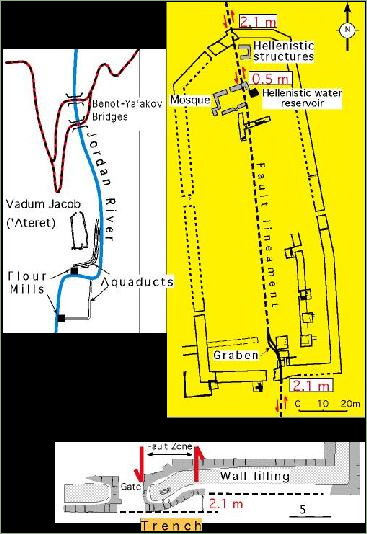

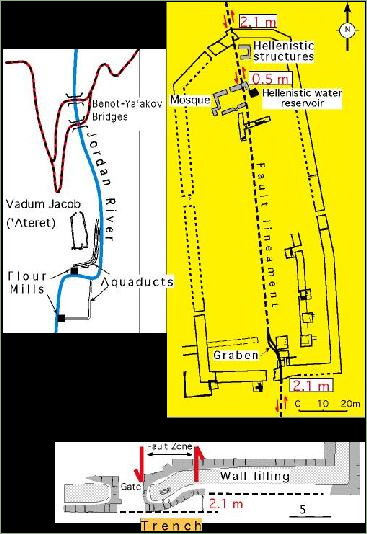

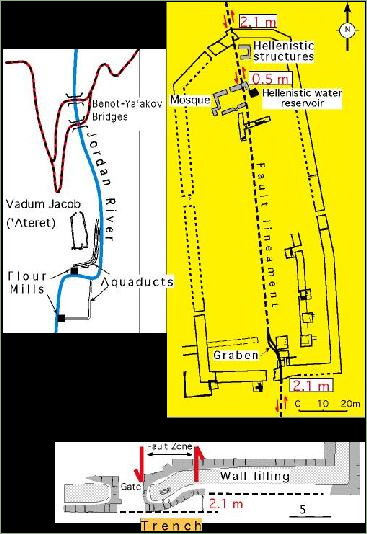

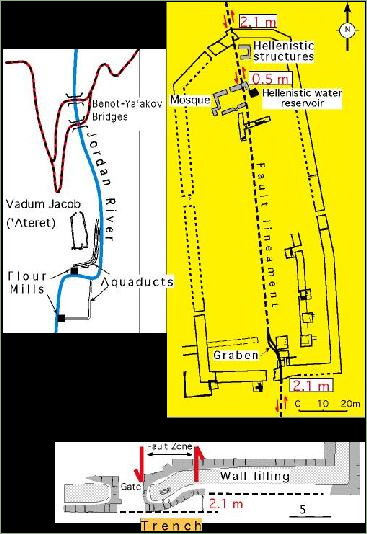

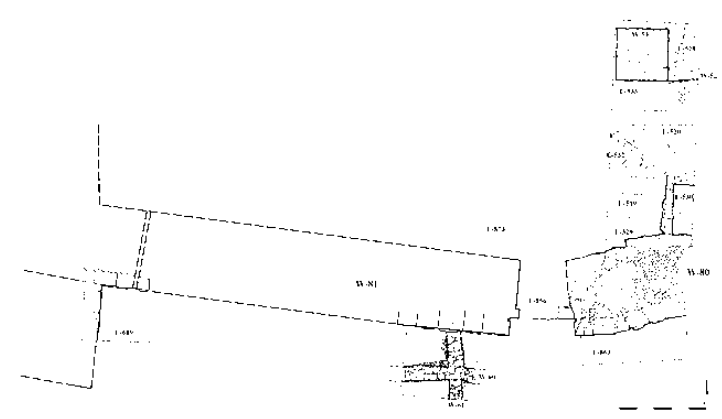

Raphael (2023) - Figure 2a and b - Plan of

Vadum Jacob fortress with offsets from Ellenblum et al (1998)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Location of offset human-made linear structures.

- Plan of Vadum Jacob fortress. Solid lines mark well-exposed parts of walls; dotted lines denote unexposed or partly exposed walls.

- Map of southern wall showing displacements and rotations of masonry.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section

Ellenblum et al (1998) - Plan of Vadum Jacob fortress

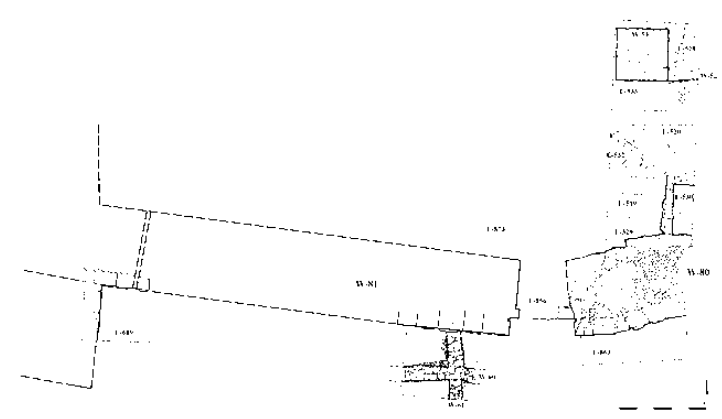

with offsets from Vadum Jacob Research Project website.

Top-Left

Top-Left

Location map

Top-Right

Plan of Vadum Jacob (Ateret) fortress. Solid lines mark well-exposed parts of walls, dotted lines denote unexposed or partly exposed walls. Note Hellenistic walls terminating at fault zone.

Bottom

Detailed map of the fault zone in the southern wall

Vadum Jacob Research Project website - Figure 1d - Oblique air

photo of site with structures identified from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 1d

Figure 1d

An oblique north looking air-photo showing Tell Ateret. Gray line marks the DSF (ie the Jordan Valley Gorge segment of Dead Sea Transform).

Ellenblum et al (2015)

- Figure 4.10 - Site Plan

from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.10

Plan of the Templar fortress at Jacob’s Ford The Mamluk–Ottoman mosque is shown in green The capital letters indicate the excavation areas

(plan renewed by Jay Rosenberg)

Raphael (2023) - Figure 2a and b - Plan of

Vadum Jacob fortress with offsets from Ellenblum et al (1998).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Location of offset human-made linear structures.

- Plan of Vadum Jacob fortress. Solid lines mark well-exposed parts of walls; dotted lines denote unexposed or partly exposed walls.

- Map of southern wall showing displacements and rotations of masonry.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section

Ellenblum et al (1998) - Plan of Vadum Jacob fortress

with offsets from Vadum Jacob Research Project website.

Top-Left

Top-Left

Location map

Top-Right

Plan of Vadum Jacob (Ateret) fortress. Solid lines mark well-exposed parts of walls, dotted lines denote unexposed or partly exposed walls. Note Hellenistic walls terminating at fault zone.

Bottom

Detailed map of the fault zone in the southern wall

Vadum Jacob Research Project website - Figure 1d - Oblique air

photo of site with structures identified from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 1d

Figure 1d

An oblique north looking air-photo showing Tell Ateret. Gray line marks the DSF (ie the Jordan Valley Gorge segment of Dead Sea Transform).

Ellenblum et al (2015)

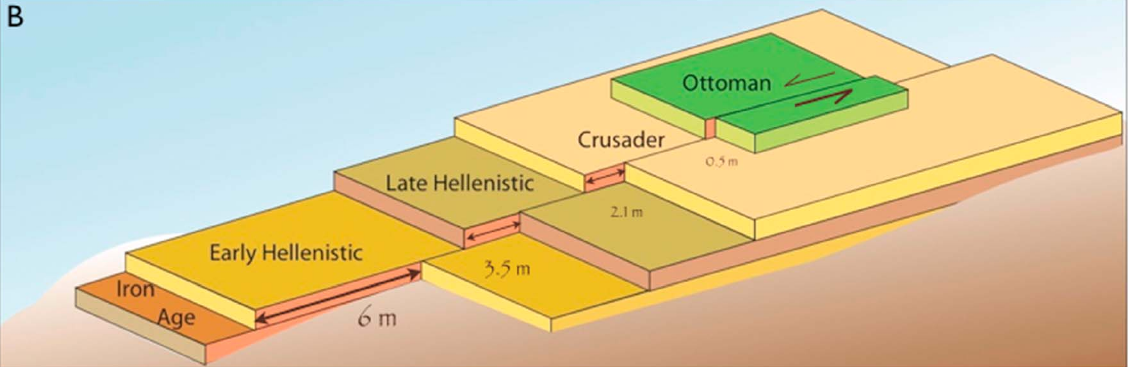

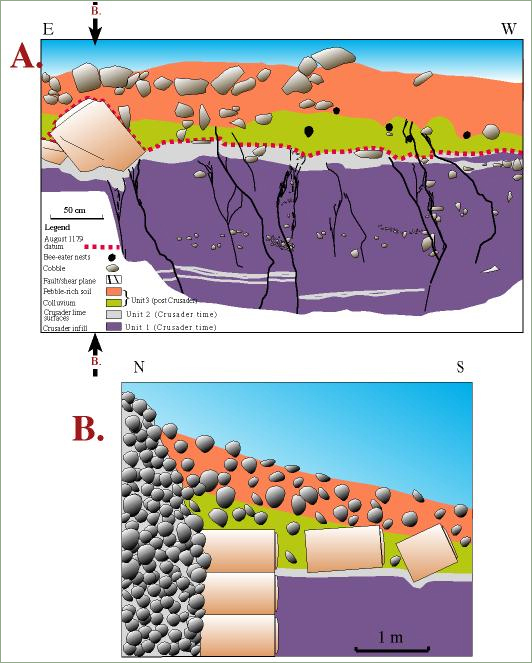

- Figure 1c - Hellenistic

complex of Tel Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 1c

Figure 1c

An oblique south looking photomosaic showing the Hellenistic complex during the excavations. The Iron Age wall is marked with blue dots, green dots mark the early Hellenistic wall that we use for measuring displacement, and yellow dots mark a late Hellenistic wall.

Ellenblum et al (2015) - Figure 1e - Hellenistic

walls in the southern part of Tel Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 1e

Figure 1e

The Hellenistic walls south of the Crusader fortress (pink dotted lines).

The dated Early Hellenistic walls are highlighted with green lines; Late Hellenistic walls with yellow lines.

Ellenblum et al (2015) - Figure 3a - Best Fit

Curves for kinematic analysis in the southern part of Tel Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 3a

Figure 3a

Map of the excavation in the southern part of Tell Ateret (see Figure 1e for location) showing the best fit curves in red, axes in blue, which we use for the kinematic analysis (equation (2)). In the analysis of deformation above buried faults the walls are assumed originally linear and trending E-W, perpendicular to faults. Angles denote βmax, rotation relatively to E-W. Faults are assumed parallel. Ruptures on the same fault are assumed to reach upward (unlock) to the same depth. Orange circle shows the location of the bronze coin hoard. Blue circles show inset-offset architecture in the Iron Age wall. Black circle shows a 70 cm left-lateral offset of the Iron Age curtain wall that predates the Hellenistic structures. This is a part of the larger offset and bending that exceeds 8 m. Measured elevations are denoted with small digits (m above sea level).

Ellenblum et al (2015) - Figure 4.16 - Plan of

the main gate from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.16

Figure 4.16

Plan of the main gate. The eastern side was partially destroyed by the 1202 earthquake. Smaller walls south of the gate (W60 and W61), date to the Iron Age.

Raphael (2023)

- Figure 1e - Hellenistic

walls in the southern part of Tel Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 1e

Figure 1e

The Hellenistic walls south of the Crusader fortress (pink dotted lines).

The dated Early Hellenistic walls are highlighted with green lines; Late Hellenistic walls with yellow lines.

Ellenblum et al (2015) - Figure 3a - Best Fit

Curves for kinematic analysis in the southern part of Tel Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 3a

Figure 3a

Map of the excavation in the southern part of Tell Ateret (see Figure 1e for location) showing the best fit curves in red, axes in blue, which we use for the kinematic analysis (equation (2)). In the analysis of deformation above buried faults the walls are assumed originally linear and trending E-W, perpendicular to faults. Angles denote βmax, rotation relatively to E-W. Faults are assumed parallel. Ruptures on the same fault are assumed to reach upward (unlock) to the same depth. Orange circle shows the location of the bronze coin hoard. Blue circles show inset-offset architecture in the Iron Age wall. Black circle shows a 70 cm left-lateral offset of the Iron Age curtain wall that predates the Hellenistic structures. This is a part of the larger offset and bending that exceeds 8 m. Measured elevations are denoted with small digits (m above sea level).

Ellenblum et al (2015) - Figure 4.16 - Plan of

the main gate from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.16

Figure 4.16

Plan of the main gate. The eastern side was partially destroyed by the 1202 earthquake. Smaller walls south of the gate (W60 and W61), date to the Iron Age.

Raphael (2023)

- Figure 4.9 - E-W section

across the width of the fortress from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.9

Figure 4.9

Schematic west-east section across the width of the fortress

(drawn by Tania Melsten)

Raphael (2023)

- Figure 4.9 - E-W section

across the width of the fortress from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.9

Figure 4.9

Schematic west-east section across the width of the fortress

(drawn by Tania Melsten)

Raphael (2023)

Top-Left

Top-LeftLocation map

Top-Right

Plan of Vadum Jacob (Ateret) fortress. Solid lines mark well-exposed parts of walls, dotted lines denote unexposed or partly exposed walls. Note Hellenistic walls terminating at fault zone.

Bottom

Detailed map of the fault zone in the southern wall which shows the location of the trench

Vadum Jacob Research Project website

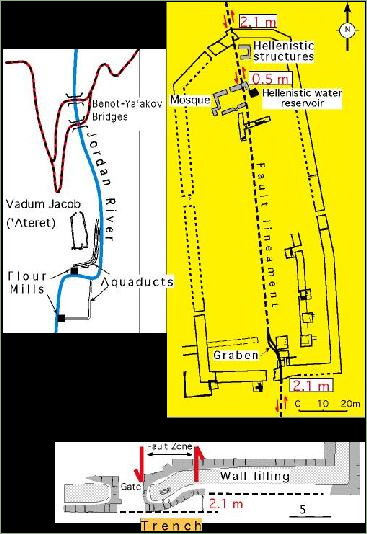

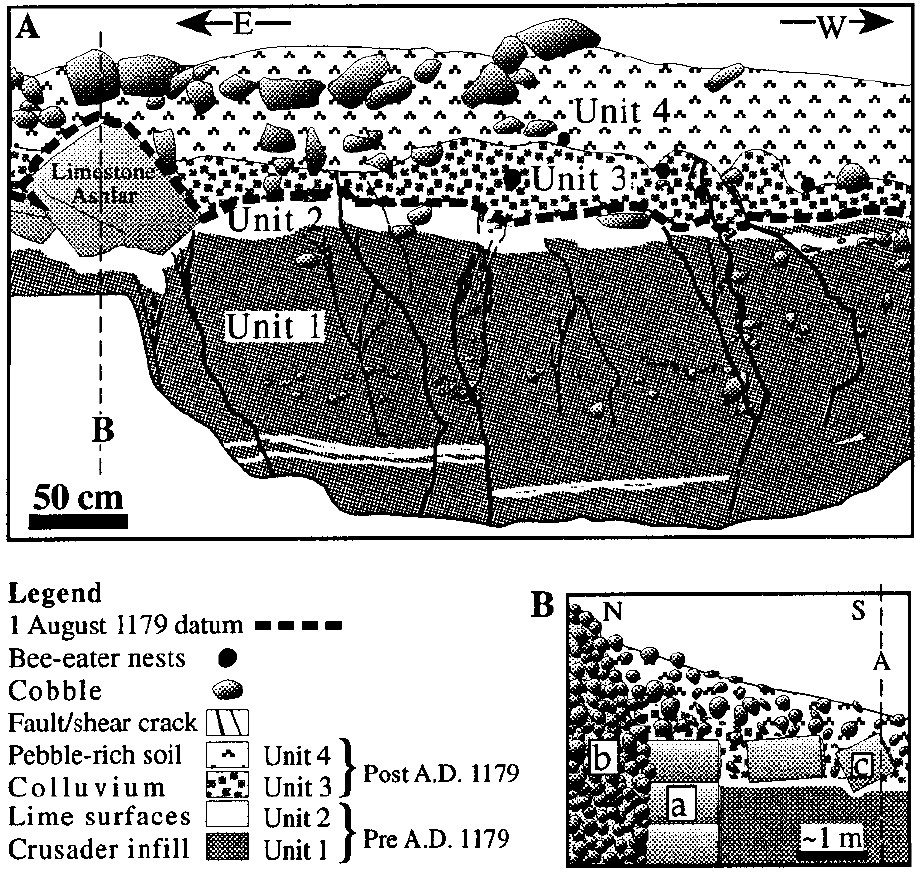

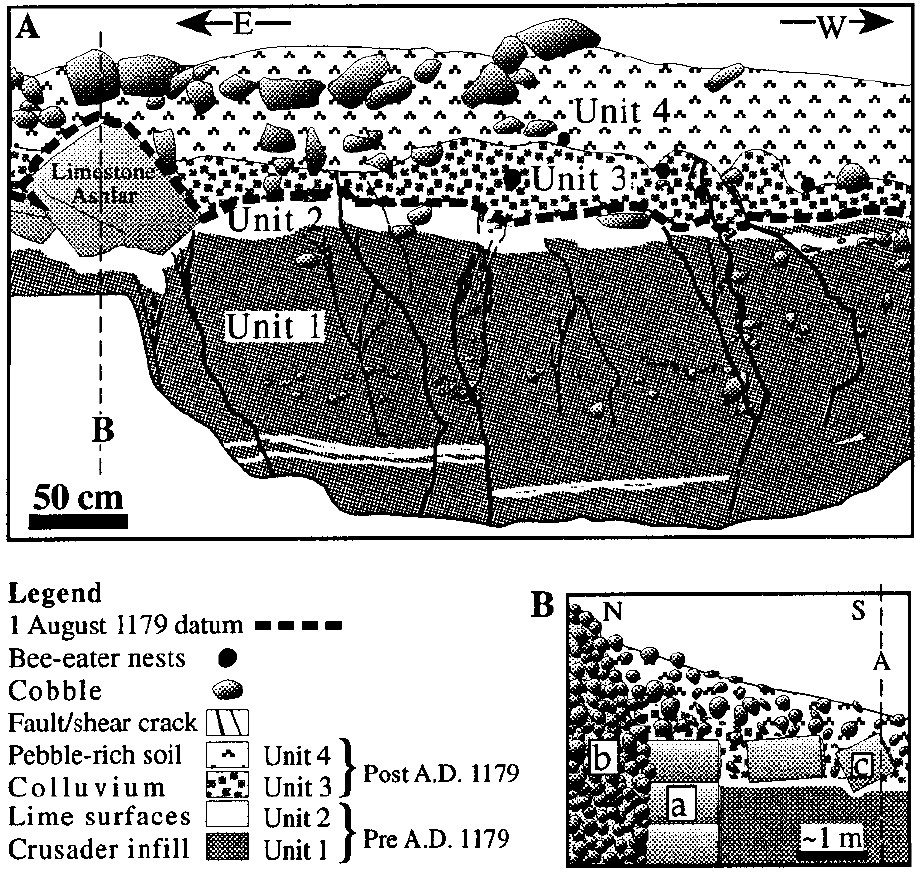

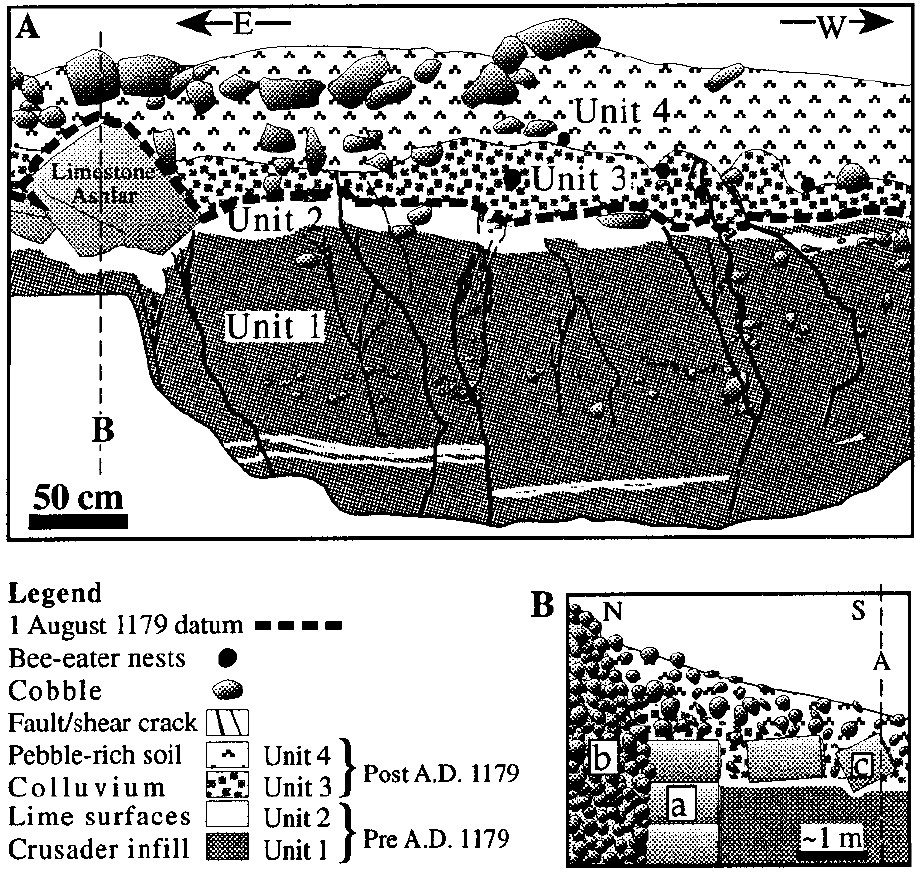

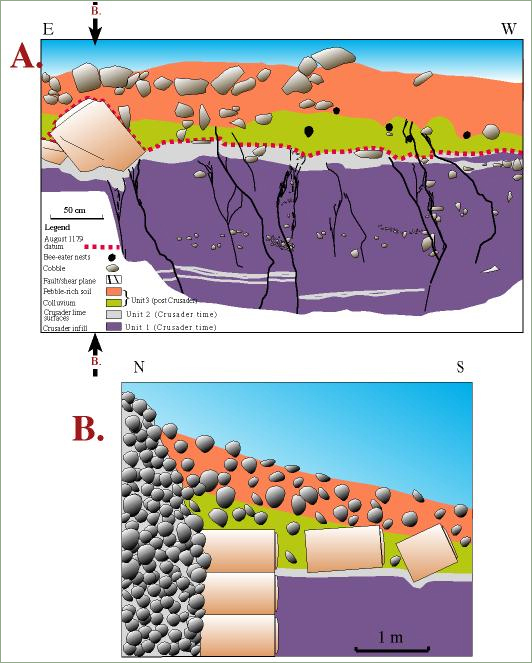

- Log of a trench wall, parallel southern face of castle. Unit 1, composed of pressed alluvium, and unit 2, a lime pavement, were laid by Crusader masons as wall was built and were used as a ramp for hauling heavy building blocks. Unit 2 was at the surface on the day of the Muslim conquest and provides a horizon precisely dated as 30 August 1179 (dashed solid line). Unit 3 started to accumulate after conquest of castle. The degradation of wall infill is apparent in abundance of basaltic cobbles. Masoned limestone ashlars on left were fallen or tumbled there by Muslims who destroyed castle in 1179. Unit 4 is a cobble-rich, A-soil in which pedogenic processes are intense. Two sets of faults (solid) and shear cracks (slim lines) are evident: One terminates at top of unit 2 or lowermost few centimeters of unit 3; second crosses unit 3 entirely. Active bioturbation in unit 4 hinders preservation of cracks.

- Schematic N-S section in southern wall of castle:

- exterior wall support

- Wall infill of cemented, mainly basaltic, cobbles

- Masoned limestone blocks that fell from exterior wall.

A. Log of a trench wall, parallel southern face of castle.

- Unit 1, composed of pressed alluvium

- Unit 2, a lime pavement, were laid by Crusader masons as wall was built and were used as ramp for hauling heavy building blocks. Unit 2 was at surface on day of Muslim conquest and provides a horizon precisely dated as 30 August 1179 (bold dashed line)

- Unit 3 started to accumulate after conquest of castle. Degradation of wall infill is apparent in abundance of basaltic cobbles. Masoned limestone ashlars on left were fallen or tumbled there by Muslims who destroyed castle in 1179

- Unit 4 is cobble-rich A-soil in which pedogenic processes are intense

B. Schematic north-south section in southern wall of castle:

- exterior wall support

- wall infill of cemented, mainly basaltic, cobbles

- masoned limestone blocks that fell from exterior wall.

Ellenblum et al (1998)

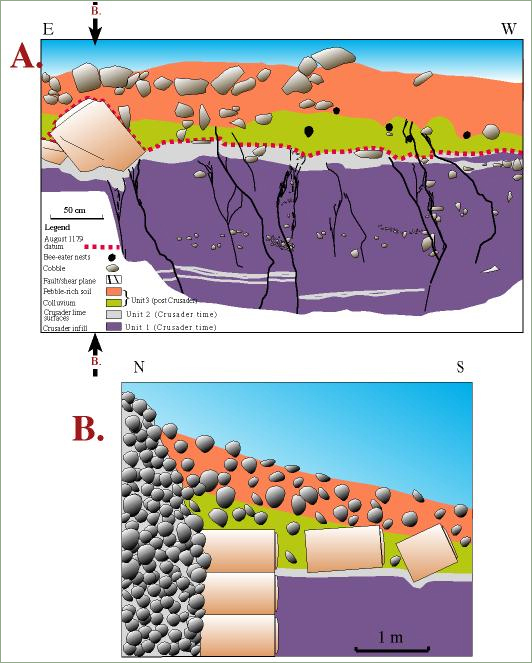

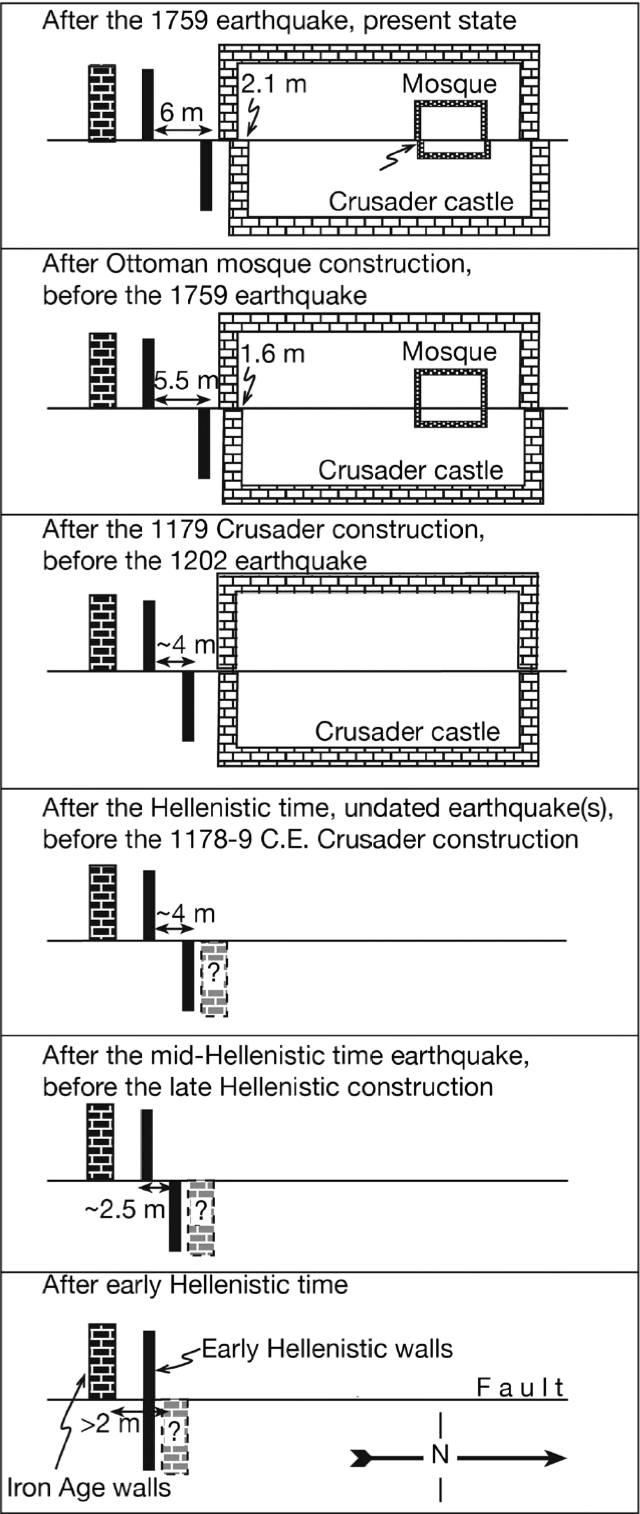

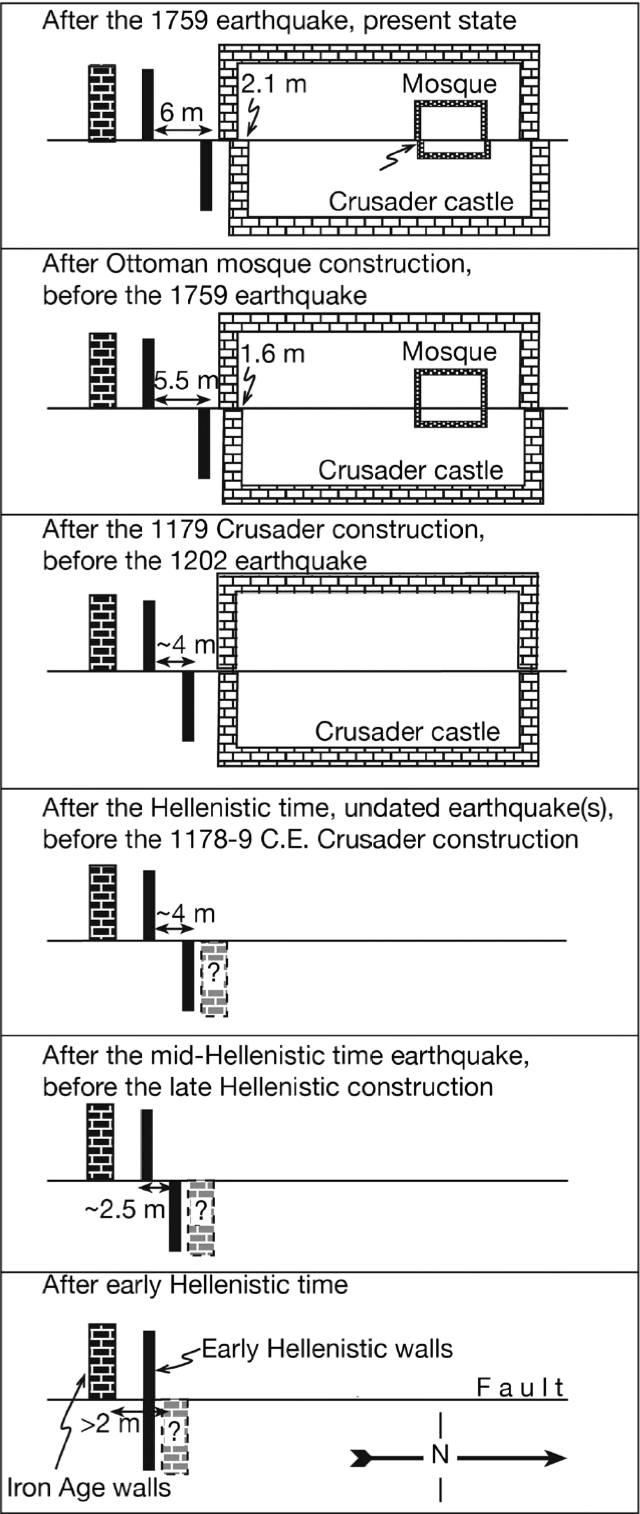

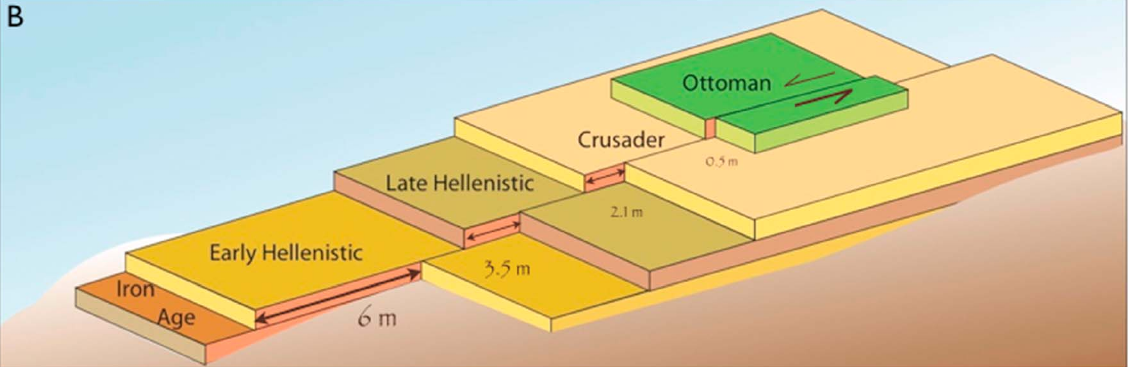

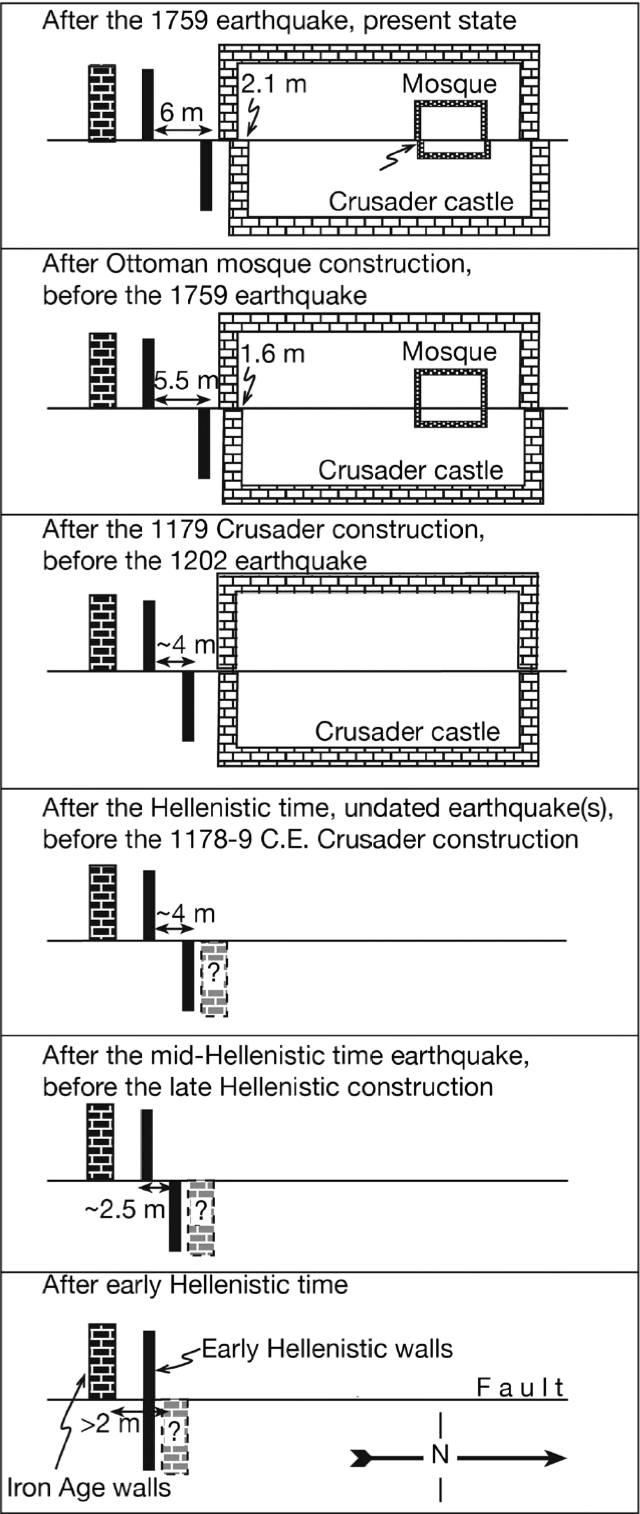

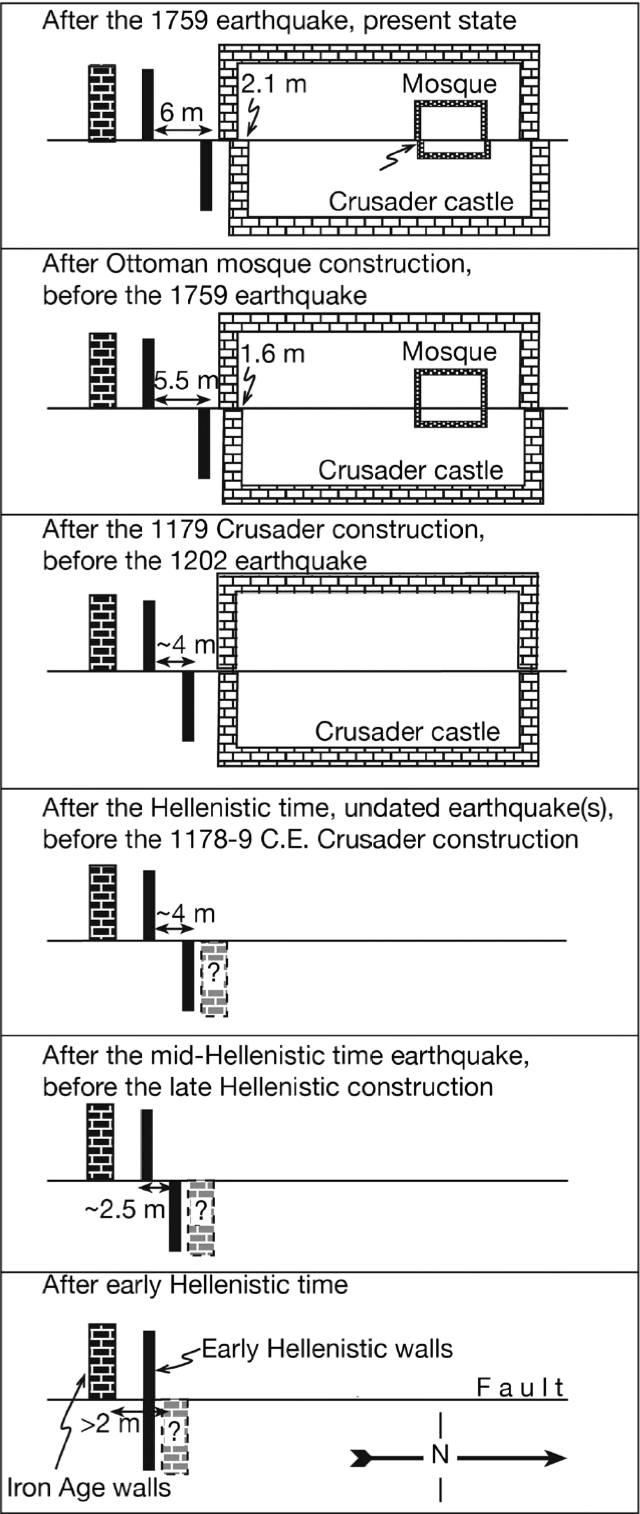

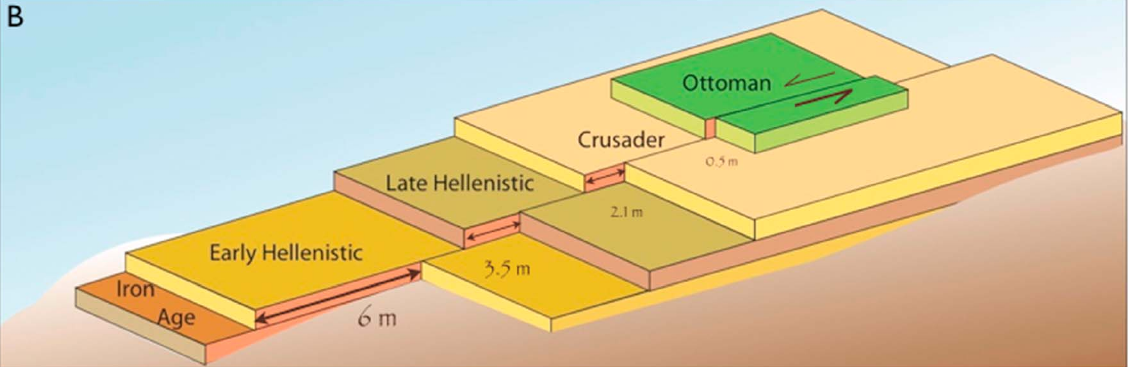

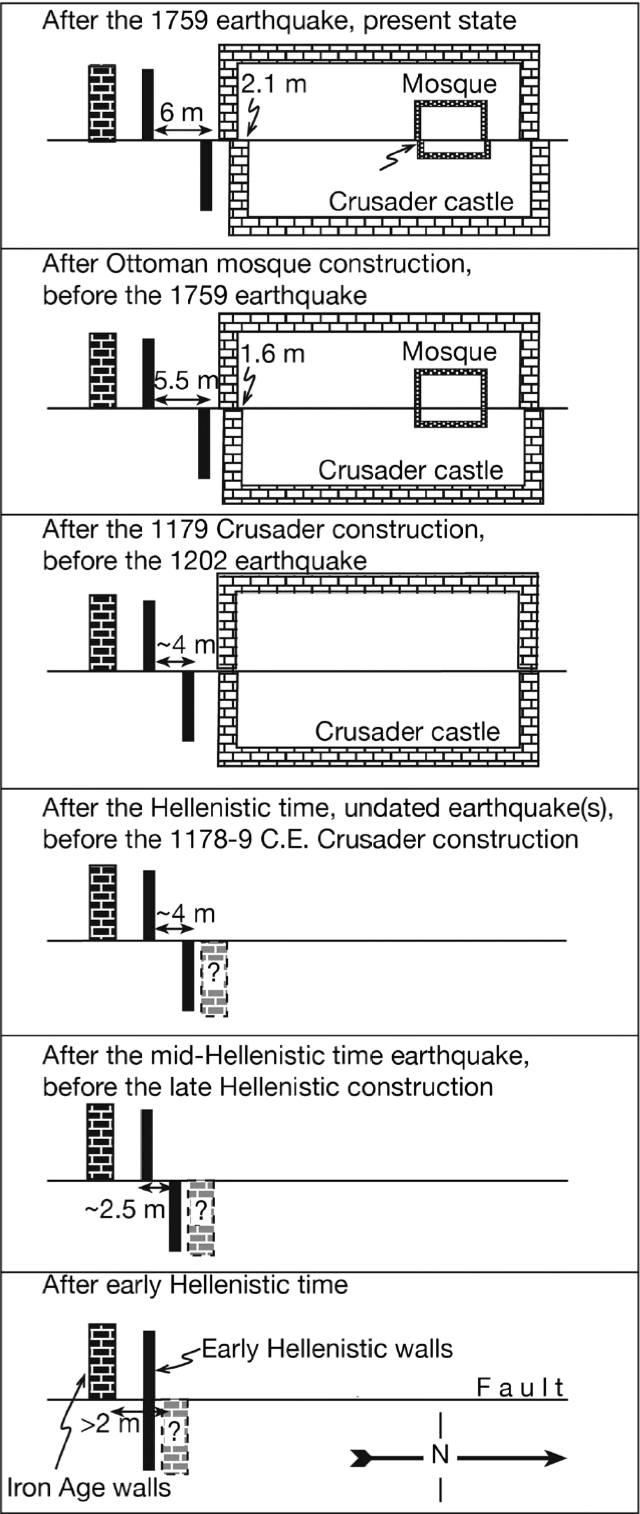

- Figure 4 - Schematic

illustration of stages of slip accrual at Tell Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 4

Figure 4

Schematic illustration of the stages of slip accrual (values are rounded) in the Ateret structures, timeline from bottom to top.

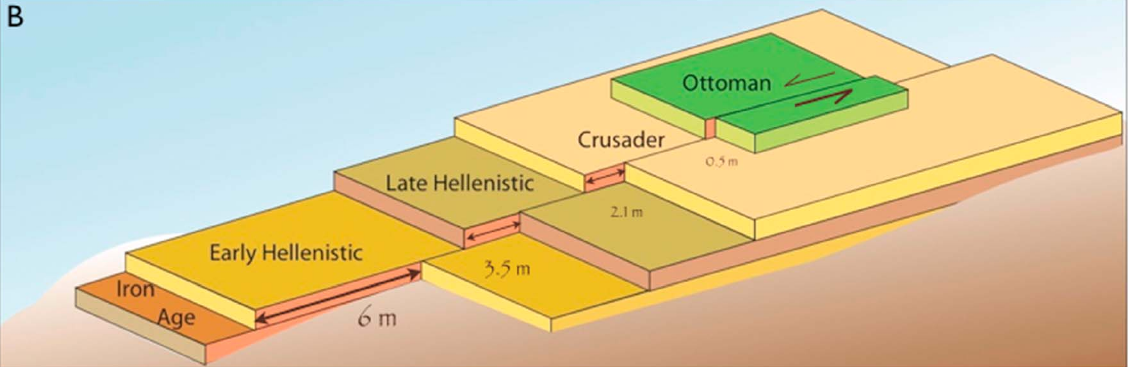

Ellenblum et. al. (2015) - Figure 3b - Schematic

illustration of slip history of Tell Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 3b

Figure 3b

A schematic illustration of the archaeological strata at Tell Ateret offset by the Dead Sea Fault. The older the strata the larger the offset

Ellenblum et. al. (2015) - Figure 4.37 - Reconstruction

of the kitchen from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.37

Figure 4.37

Reconstruction of the kitchen

(drawn by Tania Meltsen)

Raphael (2023)

- Figure 4 - Schematic

illustration of stages of slip accrual at Tell Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 4

Figure 4

Schematic illustration of the stages of slip accrual (values are rounded) in the Ateret structures, timeline from bottom to top.

Ellenblum et. al. (2015) - Figure 4.37 - Reconstruction

of the kitchen from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.37

Figure 4.37

Reconstruction of the kitchen

(drawn by Tania Meltsen)

Raphael (2023)

- Figure 4.33 - Collapsed vault

from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.33

Figure 4.33

The collapsed vault, sealing the entire gallery (Area E, L456)

Raphael (2023) - Figure 4.36 - Collapsed vault

from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.36

Figure 4.36

Remains of the collapsed vault on the kitchen floor (Area E, looking east)

Raphael (2023) - Figure 4.7 - Collapsed vault

on the kitchen floor in Area E from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.7

Figure 4.7

Remains of the collapsed vault on the kitchen floor in Area E, looking east. Note the ashlar casing and basalt core (marked with yellow arrows)

Raphael (2023) - Figure 4.49 - kitchen and

basalt platform with the remains of the collapsed vault from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.49

Figure 4.49

The kitchen and basalt platform with the remains of the collapsed vault, looking south

Raphael (2023) - Figure 4.15 - Aerial view

of Main Gate from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.15

Figure 4.15

The main gate, looking west

Raphael (2023) - Figure 4.17 - Western wing

of main gate from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.17

Figure 4.17

The main gate, western wing, looking southwest

Raphael (2023) - Figure 4.18 - Eastern wing

of main gate from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.18

Figure 4.18

The main gate, eastern wing, looking southeast, partially destroyed by the 1202 earthquake.

Raphael (2023) - Figure 4.55 - The mosque

from Raphael (2023)

Figure 4.55

Figure 4.55

The mosque, looking south

Raphael (2023) - Figure 18.2 - Aerial

photo showing displaced structures from Raphael (2023)

Figure 18.2

Figure 18.2

An aerial photo of Vadum Iacob showing displacements of structures used in the Crusader period. The fault bisects the castle. The man-made structures are indicated. The walls of the Crusader castle are displaced by 2.1 m, the Mamluk mosque is displaced by 0.5 m and one of the aqueducts (below) is displaced by 1.5 m

Raphael (2023) - Figure 18.3 - Displaced

walls in Area E from Raphael (2023)

Figure 18.3

Figure 18.3

Looking east, displacement of the Frankish walls of Vadum Iacob in Area E.

Raphael (2023) - Figure 18.4 - Displaced

northern wall from Raphael (2023)

Figure 18.4

Figure 18.4

The displacement along the northern wall of the fortress. The amount of displacement is identical to that measured along the southern wall.

Raphael (2023) - Figure 18.5 - Displaced

northern wall from Raphael (2023)

Figure 18.5

Figure 18.5

Ronnie Ellenblum with a 50 cm. scale bar right after the excavation of the faulted northern wall, in 1994.

Raphael (2023)

Ellenblum et. al. (2015:6)

uncovered Iron Age IIA remains (ca. 980-830 BCE) to the south and partially beneath the Hellenistic ruins in the southern part of the site. Preliminary dating was based on

architectural style and pottery typologies.

Ellenblum et. al. (2015:6) estimated

that the Iron Age IIA wall was displaced 8 m across the fault with 6 m of displacement taking place after the early Hellenistic period. This left 2 m of displacement in an

unknown number of events during the first millennium BCE prior to the 142 BCE earthquake

.

- Figure 1e - Hellenistic

walls in the southern part of Tel Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 1e

Figure 1e

The Hellenistic walls south of the Crusader fortress (pink dotted lines).

The dated Early Hellenistic walls are highlighted with green lines; Late Hellenistic walls with yellow lines.

Ellenblum et al (2015) - Figure 3a - Best Fit

Curves for kinematic analysis in the southern part of Tel Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 3a

Figure 3a

Map of the excavation in the southern part of Tell Ateret (see Figure 1e for location) showing the best fit curves in red, axes in blue, which we use for the kinematic analysis (equation (2)). In the analysis of deformation above buried faults the walls are assumed originally linear and trending E-W, perpendicular to faults. Angles denote βmax, rotation relatively to E-W. Faults are assumed parallel. Ruptures on the same fault are assumed to reach upward (unlock) to the same depth. Orange circle shows the location of the bronze coin hoard. Blue circles show inset-offset architecture in the Iron Age wall. Black circle shows a 70 cm left-lateral offset of the Iron Age curtain wall that predates the Hellenistic structures. This is a part of the larger offset and bending that exceeds 8 m. Measured elevations are denoted with small digits (m above sea level).

Ellenblum et al (2015) - Figure 3b - Schematic

illustration of slip history of Tell Ateret from Ellenblum et al (2015).

Figure 3b

Figure 3b

A schematic illustration of the archaeological strata at Tell Ateret offset by the Dead Sea Fault. The older the strata the larger the offset

Ellenblum et. al. (2015)

Ellenblum et. al. (2015:5) estimated a displacement of ~2.5 m from this event which, though dated from the 3rd century BCE - ~142 BCE, probably struck around ~142 BCE. Ellenblum et. al. (2015:3) described two Hellenistic building phases - one early and one late - with the later phase built atop the earlier one. Although the Northern Hellenistic Complex was too heavily damaged to allow tracing of walls across the fault zone, the southern complex in Area E allowed for such analysis which is described as follows:

Two building phases are discernible in this excavated Hellenistic compound with crosscutting relations that determine their temporal relations. The walls of both phases are deformed and truncated at the fault immediately south of the faulted Crusader wall.Ellenblum et. al. (2015:4) interpreted the coin hoard as

... The walls of the earlier phase are invariably straight along 20 m except for within the fault zone, where they are crooked left laterally. Heaps of cobbles at the bottom of the walls, which have fallen from the upper parts of the early phase walls, buried indicative artifacts including candles, vessels, cooking pots, decorated fishplates, and relief bowls, as well as imported Hellenistic wares and a hoard of coins. All these findings unambiguously belong to the Hellenistic period. The most special finding is a hoard of 45 small bronze coins buried within the debris of the older walls. A numismatic analysis of the 32 well-preserved datable coins limits the range of the hoard to 150s-140s BCE. The latest dated coin was minted in 143/142 BCE. About 60% of the coins cluster close to this date.

consistent with a scenario of sudden collapse of the wall, possibly triggered by an earthquake, adding:

The types and the arrangement of the walls indicate that the two successive construction periods were separated by a destruction event within the Hellenistic period, which left a considerable amount of debris along the fault. Based on the stratigraphy and lateral displacement, we attribute the termination of the older phase to an earthquake that tore apart the earlier phase during the second century BCE. The latest dated coin in the hoard, minted in 143/142 BCE, provides a lower bound for the date of this earthquake [i.e. a terminus post quem], after which the late Hellenistic walls were built. In another two-phase Hellenistic settlement some 20 km north of Ateret - Tell Anafa, an abrupt termination of a well-developed settlement with elaborate construction [Sharon Herbert in Stern et al (1993:58-61, v. 1)], may be re-interpreted as a result of an earthquake destruction.Ellenblum et. al. (2015:5) estimated slip from earthquake events by measuring displacement of walls across the fault:

The Hellenistic walls are bent immediately south of the faulted Crusader wall. Reconstruction of the early wall to its original straight disposition requires about 6 m (Figures 3a & 3b - above). The later wall (highlighted yellow), dated to the late 2nd - 1st century BCE, is exposed along ~8 m. It is also curved leftward at the center by about 20°. The builders of the Crusader wall destroyed the eastern segment of the late Hellenistic wall, making direct measurement of the displacement impossible.The 6 m of displacement represents slip from the Late Hellenistic Earthquake and all subsequent earthquakes. Ellenblum et. al. (2015:5) estimated a displacement of ~2.5 m for just the Late Hellenistic Earthquake. Using the scaling laws of Wells and Coppersmith (1994), this corresponds to a magnitude of 7.1 - 7.4 (see Calculator).

Ellenblum et. al. (2015) estimate ~1.5 meters of fault slip occurred on the site between its abandonment probably in the middle of the first century BC and when a Crusader fortress was built at the end of the 12th century CE. Due to the sites abandonment and lack of identified new constructions during this time, it is difficult to resolve the ~1.5 meters of slip into individual earthquake events. However, abandonment of the site may have been precipitated by an earthquake. The latest Hellenistic coin excavated from the site dates to 65/64 BCE indicating desertion of the site occurred afterwards.

Ellenblum et. al. (2015) estimate ~1.5 meters of fault slip occurred on the site between its abandonment probably in the middle of the first century BC and when a Crusader fortress was built at the end of the 12th century CE. Due to the sites abandonment and lack of identified new constructions during this time, it is difficult to resolve the ~1.5 meters of slip into individual earthquake events.

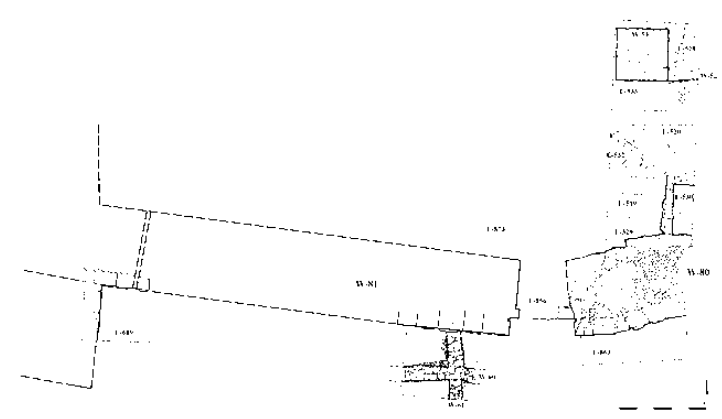

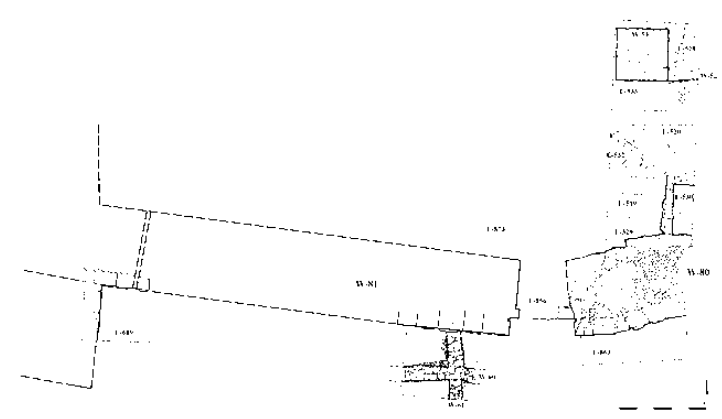

- Figure 2a and b - Plan of

Vadum Jacob fortress with offsets from Ellenblum et al (1998).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Location of offset human-made linear structures.

- Plan of Vadum Jacob fortress. Solid lines mark well-exposed parts of walls; dotted lines denote unexposed or partly exposed walls.

- Map of southern wall showing displacements and rotations of masonry.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section

Ellenblum et al (1998) - Figure 3 - Trench Log from

Vadum Jacob fortress from Ellenblum et al (1998)

Figure 3

A. Log of a trench wall, parallel southern face of castle.- Unit 1, composed of pressed alluvium

- Unit 2, a lime pavement, were laid by Crusader masons as wall was built and were used as ramp for hauling heavy building blocks. Unit 2 was at surface on day of Muslim conquest and provides a horizon precisely dated as 30 August 1179 (bold dashed line)

- Unit 3 started to accumulate after conquest of castle. Degradation of wall infill is apparent in abundance of basaltic cobbles. Masoned limestone ashlars on left were fallen or tumbled there by Muslims who destroyed castle in 1179

- Unit 4 is cobble-rich A-soil in which pedogenic processes are intense

B. Schematic north-south section in southern wall of castle:- exterior wall support

- wall infill of cemented, mainly basaltic, cobbles

- masoned limestone blocks that fell from exterior wall.

Ellenblum et al (1998) - Trench Log in color from

Vadum Jacob Research Project website.

- Log of a trench wall, parallel southern face of castle. Unit 1, composed of pressed alluvium, and unit 2, a lime pavement, were laid by Crusader masons as wall was built and were used as a ramp for hauling heavy building blocks. Unit 2 was at the surface on the day of the Muslim conquest and provides a horizon precisely dated as 30 August 1179 (dashed solid line). Unit 3 started to accumulate after conquest of castle. The degradation of wall infill is apparent in abundance of basaltic cobbles. Masoned limestone ashlars on left were fallen or tumbled there by Muslims who destroyed castle in 1179. Unit 4 is a cobble-rich, A-soil in which pedogenic processes are intense. Two sets of faults (solid) and shear cracks (slim lines) are evident: One terminates at top of unit 2 or lowermost few centimeters of unit 3; second crosses unit 3 entirely. Active bioturbation in unit 4 hinders preservation of cracks.

- Schematic N-S section in southern wall of castle:

- exterior wall support

- Wall infill of cemented, mainly basaltic, cobbles

- Masoned limestone blocks that fell from exterior wall.

Vadum Jacob Research Project website - Figure 2c - Photo of deformation

in northern wall of Castle of Vadum Jacob from Ellenblum et al (1998)

Figure 2c

Figure 2c

Photo of deformation in northern wall of Castle of Vadum Jacob. Line marks prefaulting location of wall.

Ellenblum et al (1998) - Figure 3 - Faulted wall

of the Ottoman mosque from Marco (2009)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Picture taken in 1994, before the excavation.

Marco (2009)

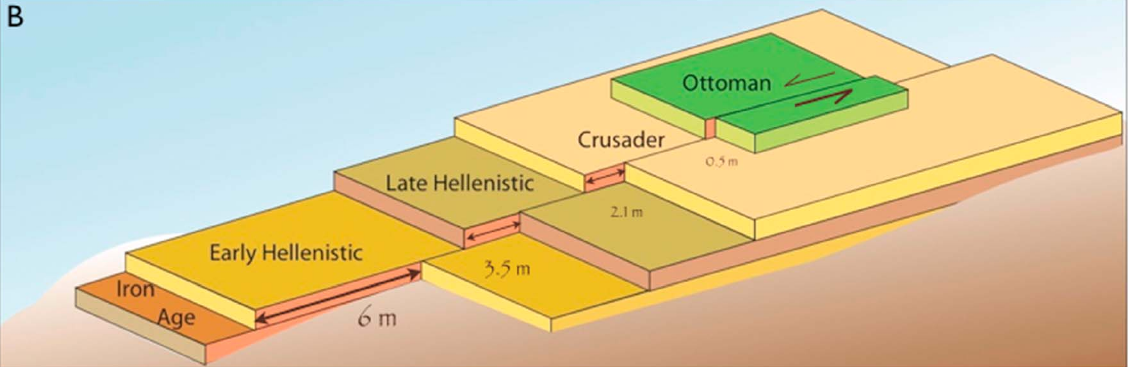

Ellenblum et al (1998:304) report, based on historical sources (e.g. William of Tyre, Abu-Shama, Ibn-al-Athir, and 'Imad al-Din al-Isfhani), that

the foundation stone of the castle [of Vadum Jacob] was laid in October 1178 CE. The castle, only partially constructed at the time,

was besieged and destroyed 11 months later, on 30 August 1179 CEproviding a terminus post quem of 1179 CE for its seismic destruction. Up to ~2.1 m of lateral slip was observed in the southern and northern defense walls (Fig. 2c - Ellenblum et. al., 1998) along with up to 10 cm. of vertical slip. 0.5 m of the lateral slip was attributed to a later seismic event which damaged an Ottoman Mosque which was later built on the site (Fig. 3 - Marco, 2009).

This left ~1.6 m of slip between the military destruction of the castle in 1179 CE and the seismic event that damaged the Ottoman mosque. In order to produce a terminus ante quem for initial seismic damage to Vadum Jacob, a trench was dug parallel to the southern face of the castle in which 4 units were identified. Units 1 and 2 were recorded as having been deposited on or prior to the castle's military destruction on 30 August 1179 CE. A fallen ashlar block on top of Unit 2 was presumed to have fallen immediately after the Muslim conquest as a historical source document (Abu-Shama) details partial dismantling of the castle soon after it was conquered. Colluvial Unit 3 was dated from 1179 CE to present and was presumed to have accumulated in the centuries after the Muslim conquest. Unit 4 is a modern bioturbated soil horizon. Faults within the trench were associated with seismic displacement of the Crusader wall and a later seismic event. Ellenblum et al (1998:305) described the faults as follows:

The faults extend to two different stratigraphic levels: One group of faults displaces the alluvium of unit 1 and the limy level of unit 2, but extends only a few centimeters into post-1179 unit 3; the second group of faults breaks much higher into the colluvial wedge, up to the base of the modern soil horizon, and possibly to the surface. These observations suggest that at least two earthquakes produced the 2.1 m offset of the southern wall that is now observed. One event occurred soon after the outer ashlar wall was removed, i.e., very soon after 1179. The second post-1179 earthquake also produced rupture at Vadum Jacob, but well after removal of the wall and the accumulation of the colluvium, probably much closer to the present.Although a strict terminus ante quem was not established, the trench suggests that an earthquake struck soon after military destruction of the castle leaving the 1202 CE earthquake as the most likely candidate.

- Figure 3 - Faulted wall

of the Ottoman mosque from Marco (2009)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Picture taken in 1994, before the excavation.

Marco (2009)

Ellenblum et al (1998:305) described archaeoseismic evidence from Mamluk and Ottoman mosques built on the site as follows:

In the northern part of the castle, we also unearthed a Muslim mosque whose northern wall is displaced sinistrally by 0.5 m. A mikhrab (the Muslim praying apse) is well preserved in the southern wall. According to the study of the pottery, the mosque was built, destroyed, and rebuilt at least twice: the initial structure was built in the Muslim period (12th century) and later rebuilt once or twice during the Turkish Ottoman period (1517-1917). The 0.5 m displacement is observed in the northern wall of the latest building phase (Figure 3, Marco, 2009).The latest rebuilding phase was not dated. Ellenblum et al (2015) suggested that the 30 October 1759 CE Safed Quake was responsible while Ellenblum et al (1998:305) and Marco et al (1997) entertained the possibility that the 1837 CE Safed Quake is also a possible candidate.

Left

LeftFigure 4

Schematic illustration of the stages of slip accrual (values are rounded) in the Ateret structures, timeline from bottom to top.

Right

Figure 3b

A schematic illustration of the archaeological strata at Tell Ateret offset by the Dead Sea Fault. The older the strata the larger the offset

Both Figures from Ellenblum et. al. (2015)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Folded and displaced walls | immediately south of the faulted Crusader wall

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

Figure 1e

Figure 1eThe Hellenistic walls south of the Crusader fortress (pink dotted lines). The dated Early Hellenistic walls are highlighted with green lines; Late Hellenistic walls with yellow lines. Ellenblum et al (2015)

Figure 3a

Figure 3aMap of the excavation in the southern part of Tell Ateret (see Figure 1e for location) showing the best fit curves in red, axes in blue, which we use for the kinematic analysis (equation (2)). In the analysis of deformation above buried faults the walls are assumed originally linear and trending E-W, perpendicular to faults. Angles denote βmax, rotation relatively to E-W. Faults are assumed parallel. Ruptures on the same fault are assumed to reach upward (unlock) to the same depth. Orange circle shows the location of the bronze coin hoard. Blue circles show inset-offset architecture in the Iron Age wall. Black circle shows a 70 cm left-lateral offset of the Iron Age curtain wall that predates the Hellenistic structures. This is a part of the larger offset and bending that exceeds 8 m. Measured elevations are denoted with small digits (m above sea level). Ellenblum et al (2015) |

|

| Debris and fallen stones indicating wall damage | South of the faulted Crusader wall ?

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Offset walls | southern and northern defense walls

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

Figure 2c

Figure 2cPhoto of deformation in northern wall of Castle of Vadum Jacob. Line marks prefaulting location of wall. Ellenblum et al (1998) |

|

| Graben | North of the southern main gate

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Offset walls | A Muslim-style room interpreted as a mosque

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

Figure 3

Figure 3Picture taken in 1994, before the excavation. Marco (2009) |

|

| Fallen stones suggesting some wall collapse | A Muslim-style room interpreted as a mosque

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

|

- Lightly modified by JW from Fig. 3a of Ellenblum et al (2015)

- some offset is due to later earthquakes

Deformation Map

Deformation Maplightly modified by JW from Fig. 3a of Ellenblum et al (2015)

- Modified by JW from Fig. 2a of Ellenblum et al (1998)

Deformation Map

Deformation Mapmodified by JW from Fig. 2a of Ellenblum et al (1998)

- Modified by JW from Fig. 2a of Ellenblum et al (1998)

Deformation Map

Deformation Mapmodified by JW from Fig. 2a of Ellenblum et al (1998)

Ellenblum et al (2015) found 8 m of accumulated slip at Tel Ateret since the construction of an Iron Age IIA fortification early in the 1st millenium BCE. They were able to resolve this slip into a sequence of time periods summarized below. In a few cases, they were able to estimate the slip of individual earthquake events allowing for an estimate of Moment Magnitude (MW) using the scaling laws of Wells and Coppersmith (1994)

| Date | Slip1 (m) |

Slip2 (m) |

Moment3 Magnitude MW |

Intensity4 I |

Intensity5 I |

Slip2 Velocity (m/s) |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 980 BCE - 142 BCE | >2 | n/a | unresolved | unresolved | n/a | n/a | At least 2 m of slip displaced Iron Age IIa walls in an unknown number of events |

| probably ~142 BCE | ~2.5 | n/a | 7.1 - 7.4 | ≥ 9 | n/a | n/a | Excavated coins suggest this event occurred around and no earlier then 142 BCE |

| ~50 BCE - 1178/9 CE | ~1.5 | n/a | unresolved | unresolved | n/a | n/a |

|

| probably 20 May 1202 CE | ~1.6 | 1.25 | 7.0 - 7.2 | ≥ 9 | 9 | 3 | Crusader Fortress Vadum Jacob Damaged |

| Ottoman period | ~0.5 | 0.5 | 6.6 - 6.8 | ≥ 8 | 7 | 1 | Ottoman Mosque was damaged |

1 from

Ellenblum et al (2015)

2 from

Schweppe, et al (2021) - Schweppe et al (2021) used detailed laser scans of the site and discrete element models to estimate slip at depth and slip velocity for the last two events.

3 computed from

Ellenblum et al (2015)'s slip using

Wells and Coppersmith (1994)

4 Estimated by Jefferson Williams primarily using Earthquake Archeological Effects chart of

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

5

Schweppe, et al (2021) converted slip velocity to Intensity using

using Wald et al (1999)

Note -

Schweppe, et al (2021) also produced Magnitude estimates which are in fairly good agreement

with the table above but because their Magnitude estimates required an input of presumed fault rupture length,

they are not repeated in the interest of avoiding circular reasoning.

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folded and displaced walls | immediately south of the faulted Crusader wall

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

Figure 1e

Figure 1eThe Hellenistic walls south of the Crusader fortress (pink dotted lines). The dated Early Hellenistic walls are highlighted with green lines; Late Hellenistic walls with yellow lines. Ellenblum et al (2015)

Figure 3a

Figure 3aMap of the excavation in the southern part of Tell Ateret (see Figure 1e for location) showing the best fit curves in red, axes in blue, which we use for the kinematic analysis (equation (2)). In the analysis of deformation above buried faults the walls are assumed originally linear and trending E-W, perpendicular to faults. Angles denote βmax, rotation relatively to E-W. Faults are assumed parallel. Ruptures on the same fault are assumed to reach upward (unlock) to the same depth. Orange circle shows the location of the bronze coin hoard. Blue circles show inset-offset architecture in the Iron Age wall. Black circle shows a 70 cm left-lateral offset of the Iron Age curtain wall that predates the Hellenistic structures. This is a part of the larger offset and bending that exceeds 8 m. Measured elevations are denoted with small digits (m above sea level). Ellenblum et al (2015) |

|

VII+ |

| Debris and fallen stones indicating wall damage and collapse | South of the faulted Crusader wall ?

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

|

VIII+ |

Ellenblum et al (2015) found 8 m of accumulated slip at Tel Ateret since the construction of an Iron Age IIA fortification early in the 1st millenium BCE. They were able to resolve this slip into a sequence of time periods summarized below. In a few cases, they were able to estimate the slip of individual earthquake events allowing for an estimate of Moment Magnitude (MW) using the scaling laws of Wells and Coppersmith (1994). The Intensity estimate for the Vadum Jacob Earthquake is 9.

| Date | Slip1 (m) |

Slip2 (m) |

Moment3 Magnitude MW |

Intensity4 I |

Intensity5 I |

Slip2 Velocity (m/s) |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 980 BCE - 142 BCE | >2 | n/a | unresolved | unresolved | n/a | n/a | At least 2 m of slip displaced Iron Age IIa walls in an unknown number of events |

| probably ~142 BCE | ~2.5 | n/a | 7.1 - 7.4 | ≥ 9 | n/a | n/a | Excavated coins suggest this event occurred around and no earlier then 142 BCE |

| ~50 BCE - 1178/9 CE | ~1.5 | n/a | unresolved | unresolved | n/a | n/a |

|

| probably 20 May 1202 CE | ~1.6 | 1.25 | 7.0 - 7.2 | ≥ 9 | 9 | 3 | Crusader Fortress Vadum Jacob Damaged |

| Ottoman period | ~0.5 | 0.5 | 6.6 - 6.8 | ≥ 8 | 7 | 1 | Ottoman Mosque was damaged |

1 from

Ellenblum et al (2015)

2 from

Schweppe, et al (2021) - Schweppe et al (2021) used detailed laser scans of the site and discrete element models to estimate slip at depth and slip velocity for the last two events.

3 computed from

Ellenblum et al (2015)'s slip using

Wells and Coppersmith (1994)

4 Estimated by Jefferson Williams primarily using Earthquake Archeological Effects chart of

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

5

Schweppe, et al (2021) converted slip velocity to Intensity using

using Wald et al (1999)

Note -

Schweppe, et al (2021) also produced Magnitude estimates which are in fairly good agreement

with the table above but because their Magnitude estimates required an input of presumed fault rupture length,

they are not repeated in the interest of avoiding circular reasoning.

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Walls - Offset walls | southern and northern defense walls

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

Figure 2c

Figure 2cPhoto of deformation in northern wall of Castle of Vadum Jacob. Line marks prefaulting location of wall. Ellenblum et al (1998) |

|

VII+ |

| Graben - seismic uplift/subsidence | North of the southern main gate

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

|

VI+ |

Schweppe et al (2021) performed numerical simulations to examine 1.75 m of slip observed on the northern fortification wall of the Crusader fortress where 1.25 m of slip was assumed to be due to the earlier presumed 1202 CE earthquake and 0.5 m of slip was due to the later Ottoman Mosque Earthquake. They estimated a slip velocity for the earlier (assumed 1202 CE) earthquake of 3 m/s and a corresponding PGA of 11.3 m/s2 which translates, using the transform of Wald et al (1999), to an Intensity of IX.

Ellenblum et al (2015) found 8 m of accumulated slip at Tel Ateret since the construction of an Iron Age IIA fortification early in the 1st millenium BCE. They were able to resolve this slip into a sequence of time periods summarized below. In a few cases, they were able to estimate the slip of individual earthquake events allowing for an estimate of Moment Magnitude (MW) using the scaling laws of Wells and Coppersmith (1994). The Intensity estimate for the Ottoman Mosque Earthquake is 7.

| Date | Slip1 (m) |

Slip2 (m) |

Moment3 Magnitude MW |

Intensity4 I |

Intensity5 I |

Slip2 Velocity (m/s) |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 980 BCE - 142 BCE | >2 | n/a | unresolved | unresolved | n/a | n/a | At least 2 m of slip displaced Iron Age IIa walls in an unknown number of events |

| probably ~142 BCE | ~2.5 | n/a | 7.1 - 7.4 | ≥ 9 | n/a | n/a | Excavated coins suggest this event occurred around and no earlier then 142 BCE |

| ~50 BCE - 1178/9 CE | ~1.5 | n/a | unresolved | unresolved | n/a | n/a |

|

| probably 20 May 1202 CE | ~1.6 | 1.25 | 7.0 - 7.2 | ≥ 9 | 9 | 3 | Crusader Fortress Vadum Jacob Damaged |

| Ottoman period | ~0.5 | 0.5 | 6.6 - 6.8 | ≥ 8 | 7 | 1 | Ottoman Mosque was damaged |

1 from

Ellenblum et al (2015)

2 from

Schweppe, et al (2021) - Schweppe et al (2021) used detailed laser scans of the site and discrete element models to estimate slip at depth and slip velocity for the last two events.

3 computed from

Ellenblum et al (2015)'s slip using

Wells and Coppersmith (1994)

4 Estimated by Jefferson Williams primarily using Earthquake Archeological Effects chart of

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

5

Schweppe, et al (2021) converted slip velocity to Intensity using

using Wald et al (1999)

Note -

Schweppe, et al (2021) also produced Magnitude estimates which are in fairly good agreement

with the table above but because their Magnitude estimates required an input of presumed fault rupture length,

they are not repeated in the interest of avoiding circular reasoning.

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Walls - Offset walls | A Muslim-style room interpreted as a mosque

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

Figure 3

Figure 3Picture taken in 1994, before the excavation. Marco (2009) |

|

VII+ |

| Fallen stones suggesting some wall collapse | A Muslim-style room interpreted as a mosque

Figure 2

Figure 2Location of offset human-made linear structures.

JW: B is a plan view. It is not a cross-section Ellenblum et al (1998) |

|

VIII+ |

Schweppe et al (2021) performed numerical simulations to examine 1.75 m of slip observed on the northern fortification wall of the Crusader fortress where 1.25 m of slip was assumed to be due to an earlier (presumed 1202 CE) earthquake and 0.5 m of slip was due to the later Ottoman Mosque Earthquake. They estimated a slip velocity of 1 m/s and a corresponding PGA of 3.14 m/s2 which translates, using the transform of Wald et al (1999), to an Intensity of VII.

Source -

Wells and Coppersmith (1994)

| Variable | Input | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| cm. | Strike-Slip displacement | ||

| cm. | Strike-Slip displacement | ||

| Variable | Output - not considering a Site Effect | Units | Notes |

| unitless | Moment Magnitude for Avg. Displacement | ||

| unitless | Moment Magnitude for Max. Displacement |

Agnon, A. (2014). Pre-Instrumental Earthquakes Along the Dead Sea Rift. Dead Sea Transform Fault System: Reviews.

Z. Garfunkel, Z. Ben-Avraham and E. Kagan. Dordrecht, Springer Netherlands: 207-261.

Barber, Malcolm (1998)

Frontier Warfare in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem: The Campaign of Jacob’s Ford, 1178-79,

in: J. France, W.G. Zajac (eds), The Crusades and Their Sources:

Essays Presented to Bernard Hamilton, Aldershot 1998, pp. 9-22

Ellenblum, R., 1998,

Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem: Cambridge,

England, Cambridge University Press, 321 pp.

Ellenblum, R., et al. (1998). "Crusader castle torn apart by earthquake at dawn, 20 May 1202." Geology 26(4): 303-306.

Ellenblum, R. (2003), Frontier activities: The transformation of a Muslim sacred site into

the Frankish Castle of Vadum lacob, Crusades, 2, 83-97.

Ellenblum, R., et al. (2015). "Archaeological record of earthquake ruptures in Tell Ateret, the Dead Sea Fault." Tectonics 34(10): 2105-2117.

Maʿoz, Z. U. (2013). "A Note on Pharanx Antiochus." Israel Exploration Journal 63(1): 78-82.

Marco, S. et. al., (1997). "817-year-old walls offset sinistrally 2.1 m by the Dead Sea Transform, Israel." J. Geodyn. 24: 11.

Marco, S. (2009). The history of the Frankish Castle of Vadum Iacob. Dead Sea Workshop, pp. 35-41

Schweppe, G., et al. (2021). "Reconstructing the slip velocities of the 1202 and 1759 CE earthquakes based on faulted archaeological

structures at Tell Ateret, Dead Sea Fault." Journal of Seismology.

Abu-Shama, 1872-1906, Le livre des deux jardins. Histoire des deux regnes, celui de Nour ed-Din et celui de Salah ed-Din, in

Recueil des historiens des croisades, Historiens orientaux: Acadèmie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Paris, v. 4, p. 194-208.

Ibn al-Athir, 1872-1906, Extrait de la chronique intitulée Kamel-altevarykh, par Ibn-Alatyr, in Recueil des historiens des croisades,

ed. Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres: Paris, Historiens orientaux, p. 189-744.

’Imad al-Din al-Isfahani, 1971, Bundari, Sana al-barq al-Shami, abridged by al-Bundari, Part 1: Beirut, R. Sesen.

William-of-Tyre, 1986, Willelmi Tyrensis Archiepis-copi Chronicon (ed. R.B.C. Huygens): Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis,

63-63a, Turnhout, book 21, chapter 25 (26), p. 997.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Tel Ateret kmz file | various |