Location map from

Guidoboni et al, 2004

Left - Hypothesis 1 Right - Hypothesis 2 from

Guidoboni et al, 2004

(089) 1170 June 29 Eastern Syria and Lebanon

sources 1

Documents

- Amalric I (king), Letter to the Louis VII (king of France), July-August 1170, in Mayer (1989, p.484)

- Amalric I (king), Grant, 1170, in Delaville Le Roulx (1894-1906, I, no.411, pp.284-6)

- Alexander III (pope), Appeal, Tuscolo, 8 December 1170, in Hiestand (1985, no.198, pp.393-4)

Annals and chronicles

- Will. Tyre, Chron., pp.934-6

- Marag. Bern., Ann., pp.49-50

- Ann. Vizel., pp.228-9

- Rob. Torig., Chron., p.519

- Ann. Floreff , p.625

- Chron quod dicitur [W.Godel], in Rob. Aux., Chron., p.240

- Ann. Colon. max., pp.120-1

- Ann. Gastin

- Ann. Magdebur., p.193

- Ann. Admunt., p.584

- Mich. Syr., 19.6, Chron., IV, pp.695-6

- Mich. Syr. Arm., Chron., pp.464-6

- Ibn al-Athir, al-Ta`rikh, p.145

- Ibn al-Athir, al-Kamil, XI, pp.254-5

- Sibt ibn al-Jawzi, Mir'at, VIII, pp.174-5

- Benjamin Tud., Itin.

- Neoph. Enkl., in Delehaye (1907), pp.211-2

- Chron. min. Arm., 1.3, p.76

- 11.24, p.502

sources 2

- Ann. Pegay., p.260

- Chron. univ. Metten., p.518

- Vinc. Beaux, Spec. hist., p.1191a

- Martin Tropp., Chron., p.437

- Martin Tropp., Liber, II, p.450

- Flores temp., p.239

- Will. Nang., Chron.

- Riccob. Ferr., Pomar. , cols.125, 174

- Riccob. Ferr., Compil., co1.240

- Tol. Lucca, Ann., pp.66-7

- Tol. Lucca, Hist., co1.1108

- Pipino, Chron., co1.627

- Dandolo, Chron., p.249

- Bezanis, Cron., p.28

- Palmieri Matteo, Liber, p.97

- Cron. Ramp., II, pp.32-3, 43

- Est. de Eracles, I/I, pp.971-3

- Chron. Terre Sainte, p.7

- Ann. Terre Sainte, p.432

- Cron. Varign., II, p.4

- Sanudo, Le cite, p.272

- Amadi, Chron.

- Chron. ad 1234, p.169

- Bar Hebr., Chron., p.339

- Ibn al-Adim, Zubdat , II, p.330

- Abu Shama, al-Rawdatayn , I, p.184

- Ibn Wasil, Mufarraj , I, p.185

- Ibn Shaddad, al-Nawadir, p.43

- Ibn Qadi Shuhba, al-Kawakib, p.189

historiography

- Rohricht (1898)

- Delaville Le Roulx (1904)

- King (1931)

- Hakobyan (1956)

- Elisseeff (1967)

- Ducellier (1980)

- Mayer (1989)

- Hild and, Hellenkemper (1990)

- Molin (2001)

literature

- Taher (1979)

- Poirier et al. (1980)

- Ambraseys and Barazangi (1989)

- Ambraseys and Jackson (1998)

- Guidoboni et al. (2004)

catalogues d.

- a. Manetti [1457)

- Lycosthenes (1557)

- Bonito (1691)

- Seyfart (1756)

- von Hoff (1840)

- Perrey (1850)

- Mallet (1853)

- Sieberg (1932a)

- Grumel (1958)

- Step`anyan (1964)

- *Ben-Menahem (1979, 1991)

- Amiran et al. (1994)

- *Ambraseys et al. (1994)

catalogues p.

- Ergin et al. (1967)

- Poirier and Taher (1980)

- al-Hakeem (1988)

- Bektur and Alpay (1988)

- Khair et al. (2000)

History of the earthquake's interpretation

The earthquake of 29 June 1170 is one of the largest seismic events ever to occur along

the northern part of the Dead Sea Transform Fault System (DSTFS), the c.1000-km. long

western boundary of the Arabian plate.

The importance of the earthquake on 29 June 1170 has left an indelible mark upon the

scholarly and scientific seismological tradition. The first references to it can in fact be

found in the earliest Mediterranean area catalogue, namely that of the humanist

Giannozzo Manetti [1457]. In the scientific seismological tradition this earthquake

has had a variety of interpretations, even contradictory ones, which have persisted

until now.

The correct dating of the shock on 29 June 1170 already appears - though not without

some uncertainty - in the main descriptive catalogues of the 19th century.

However, the persistence of discrepancies and uncertainties among the various catalogue

authors has led to a "multiplication" of the event and the generation of shocks for

which there was no evidence in the sources. These flawed data have then been transferred

unaltered into some second-generation catalogues as well - to modern parametric

catalogues, that is to say. Thus, a survey of the parametric catalogues of the

last 25 years provides an overview of the different interpretations which still survive.

In Ben-Menahem's catalogue (1979), which is subdivided into geographical and tectonic

areas, the 1170 earthquake is correctly dated to 29 June and is placed in the section

devoted to the northern end of Levant Fault System (p.278, event 14). The

parameters reported are those of a high energy earthquake (M

L = 7.9), and the

description of effects is limited to the regions lying between the Lebanon and southwestern

Syria, though the damage zone is extended to Israel and Caesarea. In a second

work, Ben-Menahem (1991, pp.20, 203) slightly downsizes the parameters of the

event (M

L = 7.5 and I

0 = X-XI) and gives the epicentral coordinates recorded by

Ambraseys and Barazangi (1989), thus shifting the area of greatest effects further

north. The information relating to the effects remains, however, substantially the

same as for the previous catalogue, with the addition of information about the

destruction of Antioch and the damage and victims in the Orontes Valley. Poirier and

Taher (1980, p.2192) correctly date the events to 12 Shawwal of the year 565 of the

Hegira, but give 30 June instead of 29 June 1170. Amongst the worst-hit locations,

only Aleppo, Antioch and Damascus are listed. Another work of the same year, Poirier

et al. (1980), provides more detail, but the damage area cannot be distinguished from

the felt area.

Al-Hakeem (1988, p.22, event 185) also mistakenly dates the earthquake to 30 June

1170 and estimates its epicentral intensity at grade IX MM. A further three 12th century

events, also recorded in this catalogue, are given without the month or day, and

could be duplications of the earthquake of 29 June 1170, perhaps inherited from some

19th century catalogues.

Bektur and Alpay (1988, p.41, event 88) record the earthquake with the correct date

and with I

0 = IX MSK-64. According to them, the shock caused many thousands of vic-

tims and was felt in Cyprus. A further three earthquakes are also recorded in this cat-

alogue, with misdatings probably resulting from transcription errors in previously

used texts.

In Amiran et al. (1994, p.270) the dates are largely gleaned from previous catalogues

(including that of Ben-Menahem, 1979) and Islamic sources. The earthquake is correctly

dated to 29 June 1170 and, according to the picture provided by the authors,

was devastating in Syria, causing damage in Tyre and hundreds of deaths in

Palestine. The main shock parameters (magnitude and intensity) remain uncertain,

along with the most seriously affected locations. The information provided in the catalogue

of Ambraseys et al. (1994, p.36 and p.101) is very limited because the event

falls outside its scope. As to the effects of the 1170 earthquake in the Egyptian area,

already recorded by Ben-Menahem (1979, 1991) and before that by Mallet (1853) and

Sieberg (1932a), Ambraseys et al. (1994) express some doubts because the local

sources for that period have been lost.

In the study by Khair et al. (2000) on the seismic zonation of the Dead Sea fault area,

all the known strong (M

S 5.9) earthquakes that occurred along the DSTFS during

the past four millennia are listed. As far as we know, this list is the latest available

catalogue. The data contained in it are, however, based only on previous works and

other historical catalogues, i.e. not on original sources. In their proposed seismic

zonation scheme, the 1170 earthquake (p.68) is located in the Karasu seismogenic

zone, i.e. the northernmost portion of the DSTFS, in the region straddling the present-

day Syro-Turkish border. The M

L (7.5) and epicentre (35.9°N, 36.4°E) values are

taken from Ben-Menahem (1991) and Ambraseys and Barazangi (1989).

The variety of interpretations substantially derives from the nature of the texts providing

the basic data used by the various authors: these are mostly scientific works and

historical catalogues of the 19th and 20th centuries, from which we may have inherited

errors as well as omissions. Exceptions to this are Poirier and Taher (1980) and Al-

Hakeem (1988), who used primary sources, but solely from the Arabic tradition. This

group of sources, although very important and authoritative (see below), constitutes

only one of the three main independent cultural-linguistic traditions relevant to the

1170 earthquake (Latin, Syriac and Arabic). The data used by Poirier and Taher

(1980) are based on the accounts of two historians: Sibt ibn al-Jawzi (but erroneously

referred to as Ibn al-Jawzi, who was in fact his uncle), and Ibn al-Athir (1160 - 1231).

The latter is one of the most authoritative Arabic sources for this earthquake, although

the picture he provides is incomplete.

Since the historical sources used are direct and authoritative but belong to a single cultural

and linguistic area, it is clear that the reconstruction of the event is necessarily limited,

and that, at best, they can provide only a partial interpretation.

Worthy of mention among more recent studies is that of Ambraseys and Jackson

(1998), in which there is a list of historical and recent Eastern Mediterranean earthquakes

associated with surface fault breaks. On the basis of a previous catalogue

by Ambraseys and some vaguely defined "unpublished data", the event of 29 June

1170 is listed (p.392, event 32) as a large shock (7.0 M

S < 7.8), located in the

Afamiyah (ancient Apamea, now Qalat al Madiq) area, in the Orontes Valley (western

Syria), with the epicentre at 35.5°N and 36.5°E. Our survey of the seismological

literature clearly shows that the earthquake lacks an agreed and reliable interpretation.

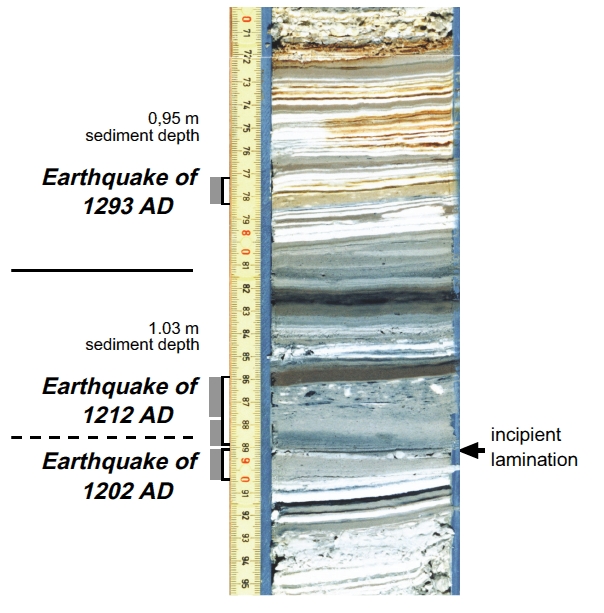

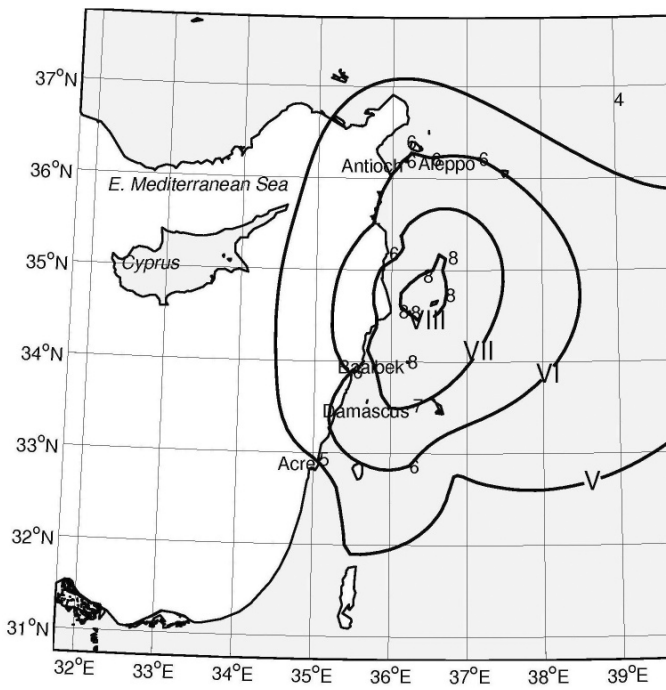

Figure 40 illustrates the different locations of the epicentre as indicated

by the various authors in the catalogues and studies cited. A piece of research

on this specific subject (Guidoboni et al. 2004) has revealed a more complex and better

documented situation, and hence allowed an assessment of 16 additional localities.

It is within this context that the two-earthquake hypothesis has been formulated.

Chronology: one or more events?

According to contemporary sources, the earthquake occurred at about 06:00 local time,

that is to say, about 03:45 UT. The detailed account by William of Tyre explicitly

records it "around the first hour of the day", in terms of the canonical hours. All the

texts analysed give 29 June 1170 as the date of the main shock. The Latin sources

date it to the third day before the Calends of July or the feast of St.Peter and Paul, in

the seventh year of the reign of Amalric I (King of Jerusalem from 1163 to 1174). The

Syriac sources give 29 Haziran in the year 1481 (of the Greeks); the Arabic sources

give 12 Shawwal in the year 565 of the Hegira. These different styles of dating all

correspond to 29 June 1170. In spite of this agreement, it is legitimate to ask whether

there was in fact one or more than one earthquake. Leaving aside the geological features

of the area, it is the extent of the effects area that suggests the answer. From

this specific standpoint we have analysed all the contemporary sources, attempting to

highlight any element that may be help to provide an answer. We have focused on the

terms with which the selected contemporary sources defined the chronology of the

event, seeing whether the terms used are singular or plural and how the date is stated.

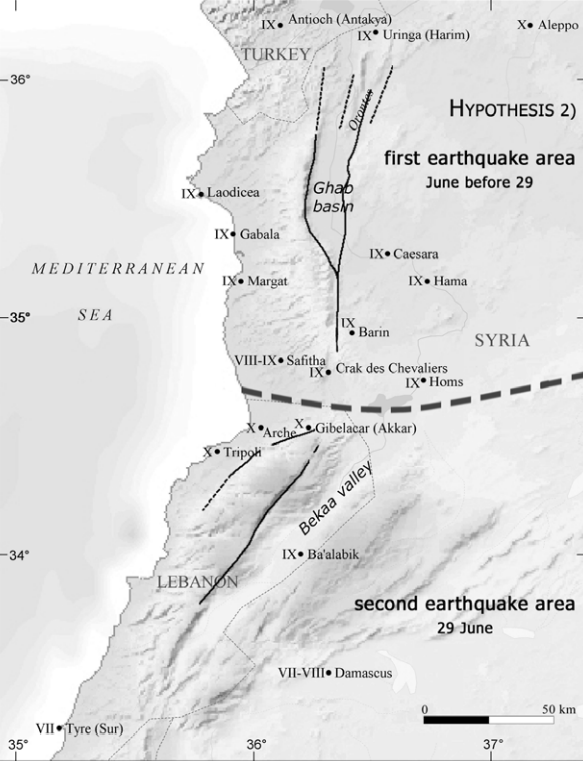

Although it is hard to be quite sure, we think that only William of Tyre contains

anything which would allow us to suppose that there were two events: one generically

dated to June 1170, the other more specifically to 29 June 1170. While remaining

critically cautious, we can observe in his text a narrative sequence supporting this

hypothesis. Indeed, in the first part of the text he says that in June 1170 an earthquake

affected seven cities very badly (in order of mention: Antioch, Gabala, Laodicea,

Aleppo, Schayzar, Hama, Emesa (Hims). They are located north of Tripoli and correspond

to the historical region that the author calls Coelesyria. Then on 29 June

Tripoli and Tyre were struck (the area is called Phoenicia by the author, and corresponds

to present-day Lebanon).

We could not find any other evidence suggesting two events, and the other contemporary

sources agree in identifying 29 June as a single event. Although the two-event

interpretation has a sound scientific basis, we have to point out that the historical

sources of the period had cognitive limitations. For in the 12th century world-view,

systematic analysis was not a key element: at that period the availability of day-to-day

data on the shocks that were felt was not the only variable. Taking account of the particular

cultural picture which the contemporary sources, provide, we have formulated

two hypotheses:

- that the identified effects can be interpreted as those of a single earthquake; it is on

this basis that the parameters have been interpreted (see fig. 42 a and b)

- that there were two strong earthquakes; for this hypothesis the parameters cannot

be calculated because the two areas are not easily differentiated and so there may well

be zones with overlapping effects (see fig. 43).

The historical context

Our research aim has been to paint a broad picture of the earthquake's effects, beginning

with the territorial divisions in medieval Syria, which included what is now the

Lebanon and Israel and was then divided into three Latin states. These territories

were formed after the military conquest by the Crusaders. From north to south these

territories were: the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of

Jerusalem; to the north was the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. The rest of the territory

was under Muslim domination (see map in fig. 41).

The production of sources for the 1170 earthquake at the time or immediately afterwards

was thus fostered by the particular historical period in which the earthquake

took place, that is to say, between the second (1147-1149) and the third Crusade (1189-

1192). These circumstances explain why such an earthquake is documented by

sources in different languages which complement one another from the point of view of

the territories struck. This evident fact, however, escaped the notice of the authors

cited above, who drew on the tradition of the Arabic texts.

The earthquake's propagation zone was enormous: it struck Al-Mawsil, Sinjar, Nisibin,

Al-Ruha, Harran, Ar-Raqqah, and Mardin, reaching as far as Baghdad, Basra and

other towns in Iraq; but the sources do not specify in detail the effects in these localities.

The earthquake was strongly felt at the monastery of Mar Hananya, but the

building did not suffer any damage. There was no damage in Palestine.

The earthquakes lasted for three or four months, or perhaps longer. There were times

when three or four or even more shocks were felt by day or night.

Effects of the earthquake

By selecting the data according to the importance and authoritativeness of the various

authors, it has been possible to outline a general picture of the damage and felt effects

of this large earthquake. It is important to note, however, that this reconstruction is

not without its omissions and problems, due to the type of text to be interpreted, the

availability of the sources, as well as the difficulty of identifying toponyms: indeed, in

the sources the same place is given different names in different languages. In spite of

the difficulties and constraints, mainly resulting from the historical time that separates

us from the event in question, our analysis has highlighted previously unknown

effects at 16 locations.

The whole territory belonging to the cities of Antioch to the north and Tripoli to the

south, both along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, and in the hinterland, along the

Bekaa Valley and the River Orontes up to the area of Aleppo was seriously affected,

with widespread destruction.

On the coast of modern Lebanon, in what used to be the County of Tripoli (now

Tarabulus), the fortified settlements of Archis (also called 'Arco., present-day Mathanat

ad Dulbah), Gibelacar (modern Akkar al Atiqah), and even the city of Tripoli itself were

completely destroyed. The latter suffered such extensive damage that most of the

inhabitants were killed. The contemporary sources agree in describing the state of

devastation at Tripoli: William of Tyre called it "untidy piles of stones"; Amalric I, in

his letter to Louis VII of France, described it as being destroyed "down to its very foundations",

with the death of nearly all the people living there.

In Amalric's letter, the fortresses of Archis and Gibelacar are also said to have been

"destroyed from their very foundations". Apart from the particular aims of the letter

(mentioned above), we think these dramatic expressions may also be idioms of

the time. Medieval Latin sources in fact use such terms to indicate the "complete

functional loss" of a building, rather than its total destruction. In any case, we

believe that such an expression, even if used in a contingent and perhaps somewhat

generic manner, could only refer to very serious and extensive damage. At Baalbek,

in the Bekaa Valley in present-day northern Lebanon, the city walls and citadel collapsed.

Farther north, in the territory of the County of Tripoli, there was serious damage to

the castle of Margat (present-day al-Marqab), and Crak des Chevaliers (now Qalat al-

Hisn). The latter was an important fortified castle, an imposing structure of dark

basalt built on a spur of Gebel Alawi, about 750 m above sea-level. It dominated the

road to the Crusader port of Valenie/Banyas, and thus controlled the coastal road

which ran north from Tripoli to the Principality of Antioch (Molin 2001). This

fortification is referred to in the Muslim sources as Hisn al-Akrad, now Qalat al-Hisn.

The sources say that it suffered the "complete" collapse of the walls. The texts

describe it as "sinking beneath the waves of the earthquake" (Abu Shama), and it was

written of the walls - perhaps without exaggeration - "there remained no trace"

(Sibt Ibn al-Jawzi). It is understandable that the Muslim sources perhaps exaggerated

such devastation, for the castle was an enemy fortification. However, the dam-

age was certainly extensive. According to Molin (2001), who also assessed it from an

archaeological standpoint, Crak des Chevaliers underwent profound transformations

following the destruction caused by the various earthquakes, including that of 1170,

which struck it at the end of the 12th and the beginning of the 13th century. The

famous and imposing fortress rises high even today, so well preserved as to be considered

the greatest medieval fortress in the world. However, it is the result of radical

modifications and reconstructions carried out from the last decades of the 12th century

to around 1220 (see fig. 44). From these we can understand the complexity and

remarkable size of the fortress.

There was further destruction at Ba`rin (known by the Crusaders as Montferrand or

Mons Ferrandus), where the city walls collapsed, as well as at the Frankish-Crusader

citadel of Safita (also known by its Frankish name of Chastel Blanc), situated between

Crak des Chevaliers and the Mediterranean coast. The historian Abu Shama (the only

one who cites this location) records Safita as having "subsided": this is another term

used by the narrators of the times, often to indicate landslides and the subsidence or

collapse of buildings.

In the hinterland territory around the River Orontes, then controlled by the Muslims,

the earthquake caused serious damage to the walls and citadels of Hims (ancient

Emesa), Hamat (Hamah) and Shayzar. Even though the last of these is in a poor

state of preservation, it still rises from a rocky spur overlooking the left bank of the

Orontes.

Along the Mediterranean coast between Tripoli and Antioch there was destruction in

the territories of the states controlled by the Crusaders. In the Principality of

Antioch, the ports of Laodicea (present-day A1-Ladhiqiya) and nearby Gabala (modern

Jablah) were struck. According to Michael the Syrian, the latter collapsed entirely.

Further north, the earthquake caused extensive destruction in Antioch and Aleppo,

two great cities which were enemies at that time.

Antioch (Antakya) was an important city of ancient origins (founded in 301 BC by

Seleucus I), and the capital of the Frankish Principality of Antioch. The fortified city

rose along the slopes of Mount Silpius. Its walls, dating back to the early Byzantine

period (they were probably built after the violent earthquake of 526 AD, see Guidoboni

et al. 1994), were 18 km long, and formed a triangle at the top of which a tenth-century

citadel was built on a mountain peak to defend the whole city (Cuneo 1986; Molin

2001). The earthquake in Antioch must have been highly destructive if it is true that,

as the sources report, it caused the collapse of the towers and walls, famous at the time

for their strength. It is nonetheless true that to say "the walls had been destroyed"

was a sort of literary topos, intended to convey that there were gaps in the walls (owing

to collapses of a greater or lesser extent) and that their defensive function could no

longer be guaranteed. Thus they no longer existed as a fortification.

Furthermore, many buildings and churches in Antioch also collapsed, in particular the

cathedral of St.Peter; the collapse of this church was considered by many Catholic

Christians in a highly ideological light and was contrasted with the "resistance" of the

three churches of the Mother of God, St.George and St.Barsauma. What had happened?

According to the sources (Michael the Syrian, Ibn al-Athir and William of

Tyre), the Franks perceived it as divine intervention because the Orthodox Christian

patriarch was officiating at mass with the clergy when the earthquake occurred. Fifty

people died altogether and Antioch is described as being half-destroyed.

Aleppo (Alab) lay to the east of Antioch. Along with Damascus and Cairo, it was one

of the main political, economic and cultural centres of the Mediterranean Muslim

world. It was an important and highly populated city, with a fortified citadel, high and

imposing defensive walls, and large mosques. From the descriptions in the sources,

the severity of effects in the city become clear. The historian Ibn al-Athir recalls that

in Aleppo "the effects of the earthquake could not stand comparison with those of the

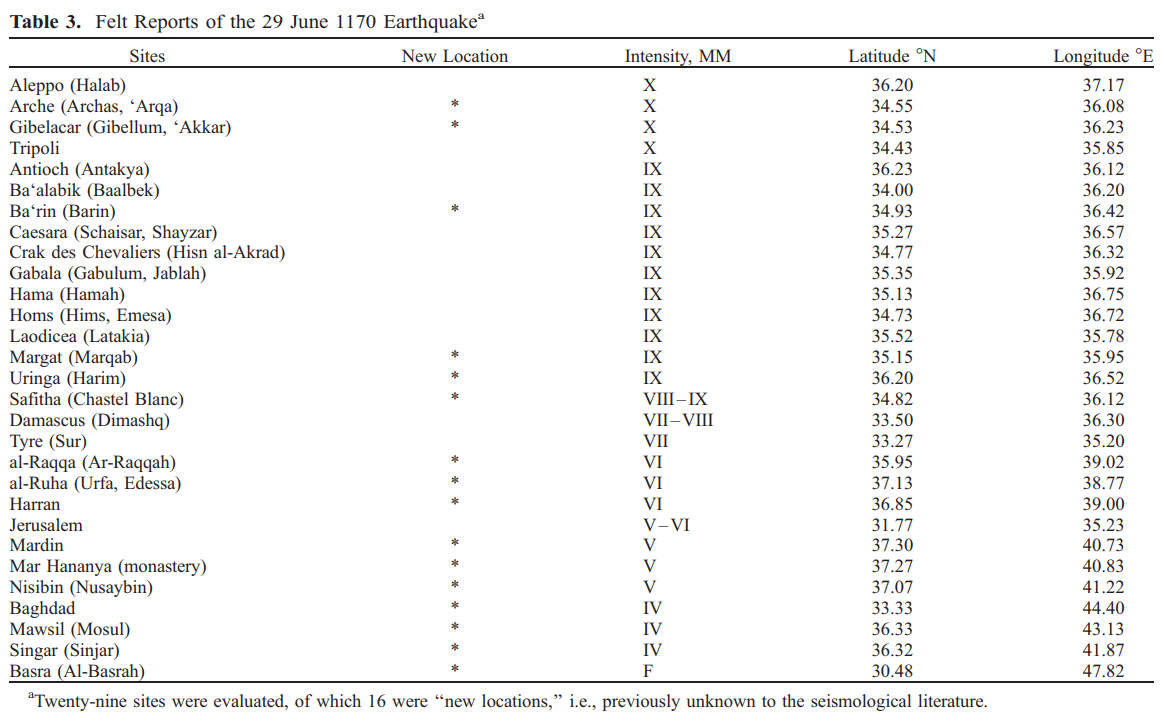

fig. 43 Earthquakes on June 1170: hypothesis 2): probable areas of two different seismic events

separated by the dashed black line, according to the interpretation that we have given to the

text by William of Tyre, coeval Latin source (elaborated after Guidoboni et al. 2004).

other cities", leaving us to suppose that effects were perhaps more serious than at

Antioch, Damascus or Tyre; he then states that "the survivors were still prey to panic,

which prevented them from returning to the places that were unscathed". The presence

of "unscathed" places suggests differentiated effects, as always happens in large

Urban areas. According to the historian Sibt Ibn al-Jawzi, the citadel that dominated

Aleppo only partially collapsed; he then adds, as confirmation of the severity of the

effects, that there was great damage to the city and that 80,000 of its inhabitants perished.

In the Syriac sources there are expressions that may appear to be contradictory, but it

should be borne in mind that the earthquake was a sign of divine wrath. Source narratives

might therefore stress that the damage was limited, particularly in regard to

powerfully symbolic buildings such as the churches, especially in that scenario of military

and religious conflict. Michael the Syrian, the most important of the Syriac

sources, refers to Aleppo in two different passages in the following terms: i) "the whole

city became a waste hill" and "the whole town fell down"; ii) the Catholic church of the

city remained intact and "not a single stone [of the church] fell down". We believe that

the effects of the earthquake at Aleppo were very serious and destructive, presumably

not lower than grade X MCS, with some areas of the city perhaps less damaged than

others, as is normally the case.

Bernardo Maragone (c.1108 - c.1188), diplomat and authoritative Italian author of the

Annales Pisani, reports that there were also serious collapses in the castle of Uringa.

According to Mayer (1989), this is the medieval and modern Arab town of Harim

(Harenc in Latin), situated in present-day northern Syria near the Syro-Turkish border,

between Antioch and Aleppo.

The earthquake also caused damage in Damascus and Tyre (now Sur), although

significantly less than in the other centres mentioned above. In Damascus, the balconies

of the Umayyad Great Mosque collapsed along with the tops of the minarets;

there is mention of the death of just one person hit by a falling stone. In Tyre, situated

on the coast of southern Lebanon, about 150 km south of Tripoli, several towers

collapsed, but without causing much serious inconvenience for the inhabitants. The

earthquake had a vast area of propagation. North-eastwards it affected present-day

Turkish territory, being felt in Al-Ruha (Edessa in the Latin sources, present-day

Urfa), Harran, Mardin, and Nisibin (present-day Nusaybin, in the Turkish province

of Mardin Ili, near the Syrian border). From the very fact that they are mentioned,

we deduce that the earthquake must have been strongly felt at these locations, and

the damage threshold of V-VI MCS may have been approached. To the south of this

area it spread in the desert of eastern Syria, where al-Raqqa (Ar-Raqqah) is mentioned,

on the banks of the Euphrates; it was felt as far east as present-day Iraq, in

Singar (modern Sinjar), Mosul (Al-Mawsil), and to the south, as far as Baghdad,

Basra (Al-Basrah) and "other cities", not specified by the sources. The historian Sibt

Ibn al-Jawzi (the only source to mention these locations) does not specify the level of

effects. In attributing an intensity level we have taken account of two criteria: i) the

types of source and the context of the narratives, which lead us to believe that such

places would not have been mentioned if the earthquake had not been felt fairly distinctly;

ii) the geographical situation, i.e. the distance of these cities from the epicentral

area.

This decision has been reinforced by an analysis of the valuable witness report by

Michael the Syrian: he in fact testifies that the earthquake was also strongly felt in the

monastery of Mar Hananya, but that the building suffered no damage. This monastery

is now Dair az-Zalaran (also known as Kurkmo Dayro in Syriac and Deyrulzafran in

Arabic), and .is situated about 6 km south east of the city of Mardin, in south-eastern

Turkey. The account by William of Tyre is clear in indicating that in Palestine there was

neither damage nor victims. Further confirmation of that comes from another Latin

source, the Chronicon quod dicitur Guillelmi Godelli (see the Latin sources), from which

it can be deduced that the main shock on 29 June 1170 in Jerusalem was strongly felt,

but without any damage of note ("the holy city of Jerusalem shook strongly, but did not

collapse thanks to God's goodness"). In our opinion, the shaking at Jerusalem can bE

confirmed at V-VI MCS, as indicated by Ben-Menahem (1979, 1991); but we do not havE

any confirmation for the suggested damage at Caesarea, on the Mediterranean coast

about 230 km south of Tripoli - also mentioned by Ben-Menahem.

Lastly, our research has not found any evidence to suggest that the earthquake was fell

in Egypt, as was argued by Ben-Menahem (1979) but questioned by Ambraseys et al

(1994).

Social and economic effects

The accounts of the two Arab historians Sibt ibn al-Jawzi and Ibn al-Athir also provide

some information about the effects that the earthquake caused on the anthropic context

In Aleppo, the surviving inhabitants sought refuge in the surrounding countryside; man:

fig. 44 Crak des Chevaliers, one of the most famous medieval castles in the Mediterranean area,

was damaged in the 1170 earthquake. Plan of the castle, which stands 750 m above sea level.

Note the extensive and complex internal articulation and.the fortifications. The double external

wall and the complicated entry system made access difficult (from Molin 2001).

survivors, however, were also terrified of remaining outside the city, for fear of an attack

by the Franks. The governor of Aleppo and Damascus, the famous Nur al-Din (Elisseeff

1967), having taken note of the very serious damage that had struck Aleppo, set up camp

nearby and personally directed the work of reconstructing the walls and buildings, also

taking into account the fact that the city could be treacherously attacked by the

Crusaders. By way of confirmation of the seriousness and extent of the damage, the

sources report that the cost of the reconstruction work was extremely high. Another

location visited by Nur al-Din was the city of Ba`rin. The Syrian governor was indeed

worried for his own safety, given that the location was very close to the Crusaders' military

outposts. The historian Ibn al-Athir records that there was frantic repair work in

the Crusaders' territories as well, since they feared an attack from Nur al-Din ("both parties

rushed to reconstruct, each one fearing the other"). Indeed, the reconstruction was

immediate and required enormous sums of money in Antioch too. At Crak des

Chevaliers (Hisn al-Akrad) the work went on for a long time. As has been mentioned

above, Amalric I donated the castles of Archis and Gibelacar to the Hospitaller Knights

in order to improve his shaky finances, on condition that they rebuilt them. In

Damascus, most of the population was panic-stricken and, fearing new shocks, abandoned

the city and sought refuge in the desert.

Historical sources: an overall view

The earthquake struck during the period between the Second and Third Crusades.

The serious damage it caused remained impressed on the memories of contemporaries,

and was passed down to later generations. Hence the large number of sources which

record it, each adding to the information provided by the others.

Three independent source traditions can be distinguished: Latin (including Italian and

French), Syriac and Arabic. Another small and more heterogeneous group consists of

Armenian, Greek and Hebrew sources. The corpus of sources set out here is the same

as that used in Guidoboni et al. (2004), where those in Latin have been shown to make

a fundamental contribution to our understanding of the event.

The most important Latin sources are three documents: a letter and a document from

Amalric I, an appeal from pope Alexander III and the chronicle of William of Tyre. He

was a contemporary writer, and indeed the most important Latin author in the Holy

Land. He was in Syria from 1162 onwards, and was appointed archbishop of Tyre in

1175. The letter from king Amalric I of Jerusalem to king Louis VII of France (1137-

1180) was written in July-August 1170. The document of 1170, also from Amalric I,

certifies that the castles of Archas (Arche) and Akkar (Gibelacar) are ceded to the

Knights of the Order of St.John of Jerusalem (the Hospitallers), on condition that they

are rebuilt. The appeal to the Church of France for funds was drawn up on 8 December

1170 on the orders of pope Alexander III (1159-1181).

The other Latin sources are much briefer and in more general terms than the above,

so we only list those which date to the 12th century:

- Annales Pisani of Bernardo Maragone, a politician and ambassador of Pisa

- Annales Vizeliacenses from the abbey of Vezelay: they go back to the middle of the 12th

century, and were continued up to 1343

- Chronica of Robert of Torigny (or Robertus de Monte), a monk at the abbey of Bec from

1128 to 1154, and subsequently abbot of Mont-St-Michel

- Annales Floreffienses, from the abbey of Floreffe

- Chronicle mistakenly attributed to William Godel but in fact compiled by an unidentified

author who belonged to the entourage of the archbishop of Sens

- Annales Colonienses maximi, drawn up in the 1170s by a canon of Cologne cathedral,

and continued up to 1220

- Annales Gastinenses, a shortened version of the Annales Uticenses, which was continued

from 1161 to 1226 by the monks of the abbey of Gatines

- Annales Magdeburgenses, compiled in the monastery of Kloster Berge, near

Magdeburg, up to 1188, and continued up to the mid-15th century

- Annales Admuntenses from the abbey of Admont, compiled by various hands from the

second half of the 12th century up to 1250

As far as Syriac sources are concerned, the most important is the chronicle compiled by

Michael the Syrian, a contemporary writer. His text was used by Bar Hebraeus, a 13th

century writer, in his chronicle. There is also a brief reference to the earthquake in

the Chronicon ad annum Christi 1234, compiled in the first half of the 13th century.

Of the Arabic sources, the most informative are Ibn al-Athir, a historian from Mosul

who visited Baghdad and Aleppo, and Sibt ibn al-Jawzi, who settled at Damascus.

Both these writers lived in the second half of the 12th century and the first half of the

13th. Reports of the earthquake in the works of 13th century writers are much briefer

and more telegraphic. The writers concerned are: the historian and biographer Ibn al-

Adim, a native of Aleppo; the historian and textual scholar Abu Shama, from

Damascus; the historian Ibn Wasil, who was also an ambassador; and the historian and

geographer Ibn Shaddad, a native of Aleppo who later lived in Egypt. Of later writers,

we pick out Ibn Qadi Shuhba, a Syrian who lived in the second half of the 14th century

and the first half of the 15th.

The earthquake is recorded not only in the above-mentioned three traditions, but also

in one contemporary Jewish source, the traveller Benjamin of Tudela, a native of Spain,

in one contemporary Greek source, namely the work of Neophytus Enkleistus, a

Cypriot saint and hagiographer; and it gains a passing mention in a few Armenian

sources: namely, what are known as the Annals of King Het`um (Chron. min. Arm., 1.3,

p.76) and a brief anonymous chronicle (Chron. min. Arm., 11.24, p.502).

Latin sources

ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTS

A few weeks after the earthquake, in July-August 1170, king Amalric I of Jerusalem

sent a letter to king Louis VII of France (1137-1180). It has been published in Mayer

(1989, p.484):

To Louis by the grace of God the most Christian king of the Franks, most dear lord and

father, from Amalric, by the same grace of God king of Jerusalem, greetings. Amidst

the daily torments of our enemies, which have so weakened the eastern church that it

is close to ruin, there has come an extraordinary disaster through the just but hidden

judgment of God. For on the day of the passion of the apostles Peter and Paul [29 June],

a terrible earthquake suddenly and unexpectedly reduced the city of Tripoli to ruins,

killing almost everyone who was there. It also shook Margat, Gabulum [Gabala] and

Laodicea, and almost all the castles and towns between Tripoli and Antioch in such an

amazing and indescribable way that no trace of buildings can be seen. In Antioch, too,

quite apart from the fact that houses and other buildings were torn apart and almost

all reduced to ruins, so that we are bound to speak with a deep groan of grief, town walls

were damaged to such an extent that they seem to be beyond repair, and indeed they

are. The result is that Antioch and Tripoli and their dependent provinces will be occupied

by the enemies of the Cross of Christ, if Tripoli, Archas [Archis], Gibellum

[Gibelacar], Laodicea, Margat and Antioch do not receive clandestine aid. But by the

will of God, the land of the Gentiles is all laid waste, and their towns and fortresses have

been more widely destroyed, not without some of their people being killed.

Ludovico dei gratia christianissimo Francorum regi, domino et patri karissimo,

Amalricus per eandem gratiam Iherosolimorum rex salutem. Cotidianis, quibus

Orientalis ecclesia usque ad sui defectum contunditur, inimicorum infestationibus,

inusitata celitus iusto, sepe tamen oculto, dei iudicio accessit calamitas. In passione

namquam apostolorum Petri et Pauli subitus et hactenus inauditus terre motus totam

Tipolim funditus delevit et omnem fere in ea carnem suffocavit. Similiter Margat,

Gabulum, Laodiciam et omnia pene castella et civitates, que suet a Tripoli usque

Anthiochiam, miro et ineffabili modo excussit, ut nec edificiorum vestigia appareant. In

Anthiochia quoque, quod non sine gravi gemitu loquimur, edificiorum et domorum, que

ferme omnes corruerunt, discidium tacentes, tanta murorum ruina facta est, ut

inreparabilis esse videatur et sit. Constat ergo quia Anthiochia et Tripolis cum

provintiis sibi suffraganeis, nisi celitus .eis subveniatur, ab inimicis crucis Christi

occupabuntur: Tripolis, Archas, Gibellum, Laodicia, Margat et Anthiochia. Sed deo

disponente terra gentilium miserabilitus tota dissipata est urbesque et munitiones non

sine suorum occisione latius deiecte.

According to a document dating to 1170 (published in Cartulaire de l'Ordre de St.Jean

de Jerusalem), Amalric I ceded the castles of Archis (Arche) and Gibelacar to the

Hospitallers, on condition that they were rebuilt:

In the name of the holy and indivisible Trinity, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

Since it is our duty devoutly to seek the common benefit of the Christian community

by means of wise justice and intuitive reasoning, and to excel in many other good

works, we have taken steps, in accordance with the dictates of Divine Clemency, to

ensure that the castles of Arche and Gibelacar, which have been reduced to ruins by the

earthquake, are not lost to the Christians. Let it therefore be known that [...] I,

Amalric, by the grace of God, fifth king of the Latins of Jerusalem and regent of the

County of Tripoli, have given to God and to the holy House of the Hospital and to

Gilbert, by the grace of God, the venerable Master of the House, the above-mentioned

castles of Arche and Gibelacar, in perpetuity with all their rights and appurtenances,

in order that they shall be rebuilt [...]. In the year of the Incarnation of the Lord 1170,

in the first indiction".

In nomine summe et individue trinitatis, patris filiii et spiritus sancti, amen. Quoniam

communi christianitatis utilitati pie providere censura justicie et rationis intuitu ceteris

etiam bonis operibus precellere dinoscitur, castro quod dicitur Arche et Gibelacar, terre

motu funditus eversis, prout divina nobis administravit dementia, ne christiculis

amitterentur subvenire curavimus Patet igitur scire volentibus quod ego Amalricus,

Dei gratia Jerosolimorum rex Latinorum quintus, Tripolis comitatum procurans, Deo et

sanctae domui Hospitalis Jerusalem, et Giberto, Dei gratia domus ejusdem venerabili

magistro prenominata castra, Archas videlicet et Gibelacar, restauranda

perhenniterque cum suis omnibus pertinentiis et juribus possedenda donavi Anno

dominice incarnationis M C L XX, indiction prima.

As the editor of the letter points out, its dating presents some problems, for Gilbert

d'Assailly, Grand Master of the Order of Hospitallers, proves to have resigned from this

post around September 1169. However, negotiations to resolve the crisis at the head

of the Order may well account for his still appearing formally in that position in 1170,

and hence being the legal recipient of a royal deed of gift. Furthermore, his successor,

Caste de Muriols, was certainly elected some time in 1171, though the exact date is not

known (Delaville Le Roulx 1904, pp.78-9; king 1931, pp.98-9).

Worries over the situation resulting from the earthquake are evident in an appeal to

the Church of France, drawn up on 8 December 1170 on the orders of pope Alexander

III (1159-1181) to gather funds for the earthquake-stricken towns and castles in the

Holy Land, and especially for the Church of Nazareth:

Bishop Alexander, servant of the servants of God. Beloved sons, to all the faithful in

the realm of France, [we give] apostolic blessing and [we wish them] good health. You

will all have been able to learn, from the accounts of travellers, of the trials, tribulations,

sufferings and troubles experienced by the towns, castles and other places in the Eastern

Lands; nevertheless, it has seemed appropriate to us, not without much concern, to

remind you of these things, and to urge you even more insistently to exercise your charity

in the face of these disasters. By the inscrutable will of God, many towns and castles

have been wholly or partly reduced to ruins or razed to the ground by the earthquake,

and a multitude of people have lost their lives in the ruins. And emboldened by

this, the enemies of Christ have tyrannically occupied some Christian places. Amongst

these is a large and populous village belonging to the Church of Nazareth, where, for

their sins, clergy and other inhabitants have been taken prisoner. For this reason, and

because of other troubles, the canons of the above-mentioned church find themselves in

a state of such want and poverty that, unless the other faithful come to their aid, they

will no longer be able to remain in His church and pay their Creator his tribute. [-J.

Issued at Tuscolo on the sixth day before the Ides of December [8 December]".

Alexander episcopus servus servorum Dei. Dilectis filiis universis fidelibus per regnum

Francie constitutis salutem et apostolicam benedictionem. Civitatum, castellorum et

aliorum locorum, terre Orientalis desolationem, tribulationes et angustias, pariter et

dolores, licet ex relatione commeantium vestra potuerit universitas didicisse, vobis

tamen non sine merore necessarium duximus significare et ad compassionem tantorum

malorum vestram sollicitare studiosius caritatem. Divino siquidem et occulto iudicio

faciente ex terre motu plures civitates et oppida, quedam ex toto, quedam ex parte diruta

et funditus evulsa, in ruina quorum ingens hominum multitudo est suffocate. Unde

quidam inimici contrarii Christi audaciam assumentes nonnulla loca Christianorum

invasion tyrannica occuparunt; inter quae magnum et populosum casale ecclesie

Nazarene peccatis exigentibus capientes clericos et ceteros habitatores in captivitatem

duxerunt. Inde est, quod canonici prescripte ecclesie turn ex hoc, turn ex aliis malis et

angustiis supervenientibus ad tantam devenere inopiam et paupertatem, quod nisi a

Dei fidelibus adiuventur, in ecclesia sua non poterunt diutius ad summi conditoris

obsequium permanere. Datum Tusculano VI idus decembris.

ANNALS AND CHRONICLES

As we have already pointed out, the most important Latin source is the chronicle of

William of Tyre (pp.934-6), which provides a long and detailed description of the

earthquake:

A very great earthquake struck almost the whole of the East, and destroyed some very

ancient cities. The following summer, that is to say in the seventh year of king

Amalric's reign [king Amalric I of Jerusalem, 1163-1174], in the month of June, there

was an earthquake of such violence in eastern parts that none greater is known to the

memory of man in this century. It reduced to ruins some of the most ancient and best

fortified cities in all the East, plunging their inhabitants into disaster and reducing

buildings to rubble, with the result that there were very few survivors. From one end

of these lands to the other, there was no place where families did not lose a member or

suffer some domestic tragedy: lamentations and funerals were everywhere. Amongst

these places, even cities in our provinces of Coelesyria and Phoenicia - great cities

ennobled by their centuries-old history, have collapsed in ruins. In Coelesyria, the

earthquake totally destroyed the city of Antioch, the capital of many provinces and

once the head of many realms, killing its inhabitants. Its walls and the very strong

towers along their circuit - a work of incomparable strength - were shaken with such

violence, together with churches and other buildings, that even today, in spite of continuous

work, enormous expenditure, constant care and devoted zeal, they can scarcely

be said to have been restored to an acceptable condition. The coastal towns of

Gabulum [Gabala] and Laodicea in the same province were also destroyed, as well as

other inland towns held by the enemy: Verea - also called Halapia [Aleppo] - Cesara

[Shayzar], Hama, Emissa [Hims] and many others; not to mention countless smaller

places. In Phoenicia, furthermore, on the third day before the Calends of July [29

June], towards the first hour of the day, the noble and populous city of Tripoli was suddenly

shaken by so violent an earthquake that scarcely anyone who was there escaped

alive. The whole city became a heap of rubble, burying the inhabitants, and crushing

them beneath this public tomb. At Tyre, the most famous city in the province, on the

other hand, an even more violent earthquake proved to be no danger to the population,

though it did cause the collapse of some very solidly built towers. In enemy territory

as well as our own, towns were seen to be half in ruins, and therefore helpless before

the wiles and attacks of their enemies. Consequently, as long as each one feared to

bring down upon himself the wrath of the stern judge, he took care not to injure his

neighbour. Each had his own sufficient troubles, and since domestic affairs brought

their own problems, harming one's neighbour was abandoned. A brief truce was

arranged, thanks to the efforts of men, and a treaty was drawn up out of fear of divine

judgment. And since each man expected due heavenly punishment for his sins, he held

back from hurling himself upon the usual objects of his hostility, and curbed his aggression.

In this case, divine wrath manifested itself not just once, as usually happens, but

for three or four months or more; three or four times a day, and perhaps even more, by

day and night, an awesome shaking of the earth was felt. Every shock was regarded

with apprehension, and nowhere was it possible to live in calm and safety. And even

the minds of those who slept were so cast down by the fears of waking hours, that the

calm of sleep was broken, and their bodies suddenly shook in agitation. However, our

upper provinces - Palestine, that is to say - with all that they contain, were spared

these great ills by the grace of God".

Terremotus maximus pene universum concutit Orientem et urbes deicit antiquissimas.

Estate vero sequente, anno videlicet domini Amalrici septimo, mense Iunio, tantus

tamque vehemens circa partes Orientales terremotus factus est, quantus qualisque

memoria seculi presentis hominum nunquam legitur accidisse. Hic universi Orientalis

tractus urbes antiquissimas et munitissimas funditus diruens, habitatores earum ruina

involvens edificiorum casu contrivit, ut ad exiguam redigeret paucitatem. Non erat

usque ad extremum terre locus, quem familiaris iactura, dolor domesticus non angeret:

ubique luctus, ubique funebria tractabantur. Inter quas et provinciarum nostrarum

Celessyrie et Phenicis urbes quam maximas et serie seculorum antiquitate nobiles,

solotenus deiecit: in Celessyria multarum provinciarum metropolim olimque multorum

moderatricem regnorum Antiochiam cum populo in ea commorante, stravit funditus,

menia et in eorum circuitu turres validissimas, incomparabilis soliditatis opera,

ecclesias et quelibet edificia tanto subvertit impetu, quod usque hodie multis laboribus,

sumptis inmensis, continua sollicitudine et indefesso studio vix possint saltem ad

statum mediocrem reparari. Ceciderunt in eadem provincia urbes egregie, de maritimis

quidem Gabulum et Laodicia, de mediterraneis vero, licet ab hostibus detinerentur,

Verea, que alio nomine dicitur Halapia, Cesara, Hamam, Emissa et alie multe,

municipiorum autem non erat numerus. In Phenice autem Tripolis, civitas nobilis et

populosa, tercio Kalendas Iulii tanto terremotus impetu circa primam diei horam subito

concussa est, ut vix uni de omnibus, qui infra eius ambitum reperti sunt, salutis via

pateret: facta est tota civitas quasi agger lapidum et oppressorum civium tumulus et

sepulchrum publicum. Sed et Tyri, que est eiusdem provincie metropolis famosissima,

terremotus violentior, absque tamen civium periculo, turres quasdam robustissimas

deiecit. Inveniebantur tam apud nos quam apud hostes opida semiruta, insidiis et

hostium viribus late patentia, sed dum quisque districti iudicis iram sibi metuit, alium

molestare pertimescit. Sufficit cuique dolor suus et dum quemlibet cura fatigat

domestica, alii differt inferre molestias: facta est, sed brevis, pax, hominum studio

procurata, et foedus compositum, divinorum iudiciorum timore conscriptum, et dum

indignationem peccatis suis debitam expectat quisque desuper, ab his que hostiliter

solent inferri manum revocat et impetus moderatur. Nec ad horam, ut plerumque solet,

fuit ista ire dei revelatio, sed tribus aut quattuor mensibus, vel etiam eo amplius, ter aut

quater vel plerumque saepius vel in die vel in nocte sentiebatur motus ille tam

formidabilis. Omnis motus iam suspectus erat et nusquam tuta quies inveniebatur, sed

et dormientis animus plerumque, quod vigilans timuerat perhorrescens, in subitum

saltum, rupta quiete, corpus agitari compellebat. Superiores tamen nostre provincie,

Palestine videlicet, horum omnium domino protegente fuerunt expertes malorum.

The fact that the author draws attention to the greater violence of the earthquake at Tyre,

without the city suffering much damage, may reflect a desire on his part to emphasise

both the solidity of its buildings and the divine protection bestowed upon it. Of the other

Latin sources listed above, we quote only the Annales Pisani of Bernardo Maragone:

In the year of our Lord 1171, in the third indiction. Since the times of Dathan and

Abiron and of Sodom and Gomorrah, there have never been such amazing and disturbing

prodigies as those which then took place in the land of Jerusalem. The city of Tripoli

with its great church dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and all its people, and half

the city of Antioch, with the church of St.Peter the Apostle, where the the saint's throne

was preserved, as well as many villages and castles belonging to the above cities, were

destroyed by an earthquake on the very day of the feast of St.Peter, which falls on the

third day before the Calends of July [29 June]. And the earthquake caused the death of

at least forty thousand Christians and many animals. On the same day, Aleppo, Cesara

[Shayzar] and Hama, large towns belonging to the Saracens, together with their depend-

ent villages and castles, including the great castle of Uringa [Harim], were destroyed by

the earthquake. It caused the death of more than two hundred thousand Saracens".

Anno Domini MCLXXI, indictione III. A temporibus Dathan et Abiron et Sodome et

Gomorre non fuerunt tam miranda et stupenda prodigia, qualia evenerunt in terra

Ierosolimitana. Civitas Tripoli cum magna ecclesia dedicata ad honorem beate

Virginis Marie, cum toto populo, et medietas civitatis Antioche cum ecclesia beati Petri

apostoli, in qua cathedra eius fuit, et cum aliquantis villis et castellis predictarum

civitatum, ipsa sollempnitate sancti Petri, que est III Kalendas Iulii, a terre motu

subverse sunt. De quo terre motu XL milia hominum chrisitanorum et ultra perierunt,

et bestie multe. Similiter eodem die Alap, Cesaria, Emma, civitates magne

Sarracenorum, cum parte villarum et castrorum earum, et Uringa castrum magnum, a

terre motu subverse sunt. De quo terremotu CC milia Saracenorum et ultra perierunt.

Syriac sources

The most important Syriac source is the chronicle of Michael the Syrian, which records:

In the same year fourteen hundred and eighty-one [of the Greeks, 1170], on Monday 29

Haziran [June], there was a violent earthquake, and the earth trembled like a boat on

the sea [the beginning of Michael the Syrian's account is missing in the original Syriac,

and so the opening sentence has been supplied from the parallel passage in Bar

Hebraeus] [...] We were in the monastery church of Mar Hananya, and lay prostrate

before the altar, to which we clung and were tossed about from one side to the other [...]

when we saw and heard and were assured that there was absolutely no damage in the

monastery nor in the whole region. And when we heard what horrors had taken place

in the lands and in the cities [...] In this earthquake, the city of Berotha, that is to say

Aleppo, collapsed in ruins... And those who said that God could not save or deliver the

prisoners from their hands [i.e. from the Arabs], were suddenly heaped up in piles by the

earthquake: their walls and their houses were reduced to ruins, and the air and the water

became infected by (the bodies of) the suffocated. The whole city was rent asunder and

became a series of cracks and fissures. The black ones (?) went up on them. The whole

city became a heap of ruins. And what shows most clearly that the sword of anger had

been drawn against it, is that nowhere else was there such horror. The seaward wall of

Antioch collapsed, and the great church of the Greeks collapsed completely. The sanctuary

of the great church of St.Peter collapsed, as well as houses and churches in various

places. About fifty souls died in Antioch. Jabala completely collapsed. And in Tripoli

a large part (of the city) and the great church similarly collapsed. And in the other

coastal cities, and at Damascus, Homs and Hama, and in all the other towns and villages,

the earthquake caused major disasters; but nowhere else had a disaster similar to that

which had happened to Aleppo been seen or heard of [...] Although the whole town of

Aleppo collapsed, our church was preserved and not a single stone fell from it. And in

Antioch three churches were saved for us: that is to say, the church of the Mother of God,

and those of St.George, and St.Barsauma. In Jabala, too, the little church we had was

preserved, and the same is true of the churches in Laodicea and Tripoli.

Arabic sources

Arabic sources call this earthquake "the Aleppo earthquake". The account provided by

Ibn al-Athir is rich in detail:

In that same year [565 H.], on 12 Shawwal [29 June], the earth shook a number of

times in a terrifying way: no-one had ever seen anything like it. The earthquake struck

the whole region of Syria, Mesopotamia, Mawsil and Iraq. The most devastating effects

were produced in Syria: there was very serious damage at Damascus, Ba'alabik, Hims,

Hamat, Shayzar, Ba`rin, Aleppo and elsewhere; walls and citadels were destroyed everywhere;

the walls of houses fell on to the inhabitants, who were killed in great numbers.

When Nur al-Din heard about the earthquake, he came to Ba'alabik to rebuild the

ruined walls and citadel, unaware that the earthquake had brought destruction to other

places as well. When he arrived, he was told of the situation in the rest of the country:

town walls destroyed and inhabitants scattered. When he had put someone in charge

of reconstruction and defence at Ba'alabik, Nur al-Din made his way to Hims, in order

to guarantee protection to its people; then he went to Hamat, and then to Ba`rin. The

whole country was in severe danger from the Franks, especially the citadel of Ba`rin,

which was near their positions and had lost all its surrounding walls. So he left part of

his army there under the command of a general, so that reconstruction work could be

carried out night and day. Then he went to Aleppo, where the effects of the earthquake

were beyond comparison with what had happened at other towns. The survivors were

still in a state of panic, which kept them from returning to places that had not been

damaged, for fear of further shocks. Moreover, they were terrified at the idea of remaining

in the countryside near Aleppo, because there was the danger that the Franks might

attack. When Nur al-Din saw the effects of the earthquake on the town and its inhabitants,

he camped outside Aleppo and directed the work of reconstruction himself, overseeing

the work of the labourers and masons until the town walls, mosques and houses

had been rebuilt. The cost of the work was enormous. In the territory of the Franks

as well, - may God destroy them - the earthquake caused a great deal of damage.

They too worked feverishly at reconstruction, fearing an attack by Nur al-Din. In this

way, both sides hurried to rebuild, each out of fear of the other.

Sibt Ibn al-Jawzi also provides a great deal of information:

In the month of Shawwal, there were terrible earthquakes in Syria, causing severe

damage at Damascus: the balconies of the mosque [the Great Umayyad Mosque] collapsed,

as well as the tops of the minarets, which shook like palm trees on a stormy day.

[...] The earthquakes which struck Aleppo were even stronger: half of its citadel collapsed,

and there was severe damage in the city; 80,000 people are reckoned to have

died in the ruins. The walls of all the fortresses were damaged, and the people fled into

the countryside. Hisn al-Akrad collapsed, and no trace of its walls was left. The same

thing happened at Hamat and Hims. When Nur al-Din came to Aleppo, he was worried

that the collapse of its walls would expose it to enemy attack. The earthquake was

felt everywhere. Muslim fortresses were destroyed throughout the province of Syria:

at Aleppo, at other towns, and at Antioch. The earthquake even reached Laodicea and

Jabala, and struck all the coastal towns, as far as Byzantine territory. They say that

the only man to be killed at Damascus was struck by a piece of stone as he climbed the

Jayrun steps, the entire population having fled into the desert. The earthquake then

reached the Euphrates, struck Mawsil, Sinjar, Nisibin, al-Ruha, Harran, Al-Raqqa,

Mardin and other towns as well, reaching as far as Bagdad, Basra and other towns in

Iraq: No-one had ever seen such an earthquake since the beginning of Islam.

The accounts provided by the other four 13th century Arab historians are much briefer.

According to Abu Shama

al-Imad al-Isfahani said:

the Frankish citadels of Hisn al-Akrad, Safita and Arqa, near Ba`rin, collapsed in the waves of the earthquake; the first

of the three, in particular, was left without walls, and rebuilding work kept the Franks

occupied for a long time. From all parts of Syria came news of earthquakes and their

disastrous effects; but one piece of news gladdened hearts in the midst of such desolation:

the damage inflicted on Frankish camps was even worse. For the earthquake

caught them on a feast day, when they had gathered in church. Ceilings collapsed on

their heads, and so punishment came whence they would never have expected it.

Ibn Wasil simple records:

This earthquake came to be known as the earthquake of Aleppo and its region, just as

that of the year 552 was the earthquake of Hamat

Ibn al-Adim reports

Nur al-Din was informed of the earthquakes which had struck Syria, especially the

one which had destroyed Aleppo, and which, because of the continuing shocks, had

caused the inhabitants to abandon the town and take refuge in the country from dawn

on Monday 12 Shawwal [30 June].

Finally, Ibn Shaddad reports:

There was an earthquake at Aleppo which destroyed a large part of that region. It

was on 12 Shawwal in the year 565. Many confuse this earthquake with that of 552.

Hebrew source

A 12th century Jewish traveller, Benjamin of Tudela, a native of Spain, made a long

journey to visit numerous Hebrew communities in the Near East. In his account he

mentions some violent earthquakes that hit Tripoli and Hamah, and that caused the

death of many Jews. The text by Benjamin does not contain any explicit chronological

references, if we exclude the citing of the year 4933 of the Hebrew calendar, corresponding

to 1173 of the Julian calendar, inserted by the author to indicate the year of

his return to Spain. However, the implicit chronological references in this text allow

us to date Benjamin's journey between the first half of the 1160s and 1173. In the passage

that is referred to Tripoli of Syria, Benjamin writes that the earthquake had

occurred "in the past years", and in the one concerning the city of Hamah, "several

years before". According to Prawer (1988, pp.193-4), in both cases Benjamin was referring

to the earthquake of 29 June 1170. The text of the two passages is the following:

Some years ago there was an earthquake at Tripoli, in which many Jews and Gentiles

lost their lives, because houses and walls collapsed on top of them. At that time, the whole

of Tres Isra'el was laid waste, and more than twenty thousand people died there. [...1.

Hamah, that is to say Hamath, is one day's journey [from Hims]; it stands on the banks

of the river Jabboq, at the foot of Mt.Lebanon. Some years ago, there was a great

earthquake in the city and in a single day twenty-five thousand people were killed, of

whom about two hundred were Jews, but seventy survived.

Greek source

We think we can add to our corpus of sources the text of Neophytus Enkleistus, who

was living on the island of Cyprus:

Then [after the Paphos earthquake of c.1165], a short time later, a monk of the great

city of Antioch came to see me, and told me that there had been a tremendous earthquake

in that city; not only, he said, was the earth violently shaken, but it also made a

roaring noise and was split open, and stones were thrown down as though into an

abyss. As the earth joined together again, stones which were on the upper edges were

hurled upwards as though they had been thrown by a ballista. Not only did the town

walls and a large proportion of houses collapse, but also the great church, killing the

patriarch and a great many other people.

In the period of this earthquake, between Syria and Turkey there was also a small

Armenian kingdom (Lesser Armenia or Armenian Cilicia). Presumably some mention of

this earthquake in several Armenian chronicles was due to direct contact with the affected

areas. There are two Armenian texts that contain some reference to this earthquake:

the so-called Annals of King Het`um (Chron. min. Arm., 1.3, 76) and a short anonymous

chronicle (Chron. min. Arm., 11.24, 502), both published by Hakobyan (1951-56).

References

Guidoboni, E. and A. Comastri (2005). Catalogue of Earthquakes and Tsunamis in the Mediterranean Area from the 11th to the 15th Century, INGV.