Shechem

Aerial view of Tell Balâṭah/Ancient Shechem

Aerial view of Tell Balâṭah/Ancient ShechemClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Dr. Avishai Teicher - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 4.0

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Sekem | Hebrew | שְׁכֶם |

| Shechem | Hebrew | שְׁכֶם |

| Sichem | Hebrew | שְׁכֶם |

| Šăkēm | Samaritan Hebrew | |

| Sekem | Ancient Greek | Συχέμ |

| Tell Balâṭah | Arabic | تل بلاطة |

Ancient Shechem, located at the hub of a major crossroad in the hill country of Ephraim, 67 km (40 mi.) north of Jerusalem was an important cultic and political center. Biblical and classical references to the site converge to place it between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim in the central hill country. Vespasian's foundation of Neapolis, or "new city," in 72 CE, at the western opening to the same pass yielded the Arabic name Nablus, and many have sought the ruins of ancient Shechem there. However, what covers ancient Shechem is the village and mound named Balâṭah, at the eastern end of that pass. The slightly elevated 15-a. mound of Balâṭah is sited on the lowest flanks of Mount Ebal. It rises some 20 m above the 500 m contour passing through the village at the lowest point of the valley. Abundant water comes from springs emerging all along the north and east flanks of Mount Gerizim. It looks out upon a fertile plain to the east and south - one of the most pleasant in the central hills and one that constitutes a natural system of ancient settlement. The modern village runs up onto the southern one-third of the ancient mound, but the open two-thirds remains accessible for research.

The road system from Jerusalem on the spine of the hill country divides at Balatah to circumvent Mount Ebal. Its western arm gives access to the Coastal Plain and north to Samaria/Sebaste and Dothan. The eastern arm gives access to the Jordan River via Wadi Far'ah and north past Tell el Far'ah (North) to Dothan.

H. Thiersch is credited with finding Tell Balatah. In 1903, he observed a stretch of an exposed fortification wall at the west of the mound and a heavy scattering of sherds. He put that together with the location of the weli called Qubr Yusef (Joseph's Tomb) at the eastern edge of the modern village, to confirm the identification. Not much farther east is the traditional location of Jacob's Well, connected with the story in John 4:1-42. Looming over the site is Tell er-Ras, on a forward salient of Mount Gerizim (q.v.), which contains the ruins of a temple dedicated to Zeus Olympus. The Hellenistic remains that constitute the uppermost strata at Tell Balatah indicate the location of Shechemin Hellenistic times. It remains an open question how the name Sychar in John 4 fits with all of this, especially because there is a modern village called 'Askaron a Hellenistic and Roman ruin just to the north of Balatah on Mount Ebal. Excavation has established, in any case, that Neapolis = Nablus) flourished in Roman times, whereas pre-Roman Shechem was at Tell Balatah.

Prior to excavation, Shechem was known from texts that seem clear enough but require interpretation. Egyptian references in the later set of Execration texts and the Khu-Sebek inscription, both from the nineteenth century BCE, seem to designate both a city and a territory - in short, a city-state - in the Middle Bronze Age IIA. A number of the mid-fourteenth century BCE Amarna letters point to a city-state center at Shechem ruled by Lab'ayu - a center that had an impact on Megiddo, Jerusalem, Gezer, the Hebron region, and Pella across the river, via the passes to the Jordan Valley. Biblical passages mentioning Shechem relate Abraham (Gen. 12:6), Jacob (Gen. 33:18-20, 35:1-4), Jacob's whole family (Gen. 34), and Joseph (Gen. 37:12-17) to the old city, but these stories are filled with curious ingredients and leave open many questions about the city. The same is true of the reference in Genesis 48:22 to "one Shechem" which Israel (=Jacob) is said to have taken by force from the Amorites. Then there are references to the city or its setting in Deuteronomy 27 and in the Deuteronomistic histories in Joshua 8:30-35, Judges 9, Joshua 24:32, Joshua 24:1, and I Kings 12. Taken together, these passages make at least some things clear: that in Israelite lore Shechem was a prominent sanctuary center related to Israel's heritage through the patriarchs and hence was a place to return to; that covenant making and renewing were powerful ingredients in the religious significance of Shechem; that Canaanites and Israelites encountered one another here, but the encounter does not seem to have resulted in military conflict - at least at the time of the Joshua "conquest" (cf. Gen. 34); and that Shechem was so prominent that it was the place to go to establish one's right to rule the region (Abimelech in Jg. 9; Rehoboam and Jeroboam in I Kg. 12). It is thought to have been the capital of Solomon's first district (I Kg 4:8) and is named as the city Jeroboam built and occupied (I Kg. 12:25), the first capital of the Northern Kingdom. Reminiscences of its prominence are found in Hosea 6:9 and Jeremiah 41:5. It was a city of refuge (Jos. 20:7) and as such part of the Levitic allotment (Jos. 21:21), and it is a key marking point on the boundary between Ephraim and Manasseh (Jos. 17:7). Mentioned as one of the districts that provisioned Samaria in the Samaria ostraca, presumably from the first half of the eighth century BCE, it appears in a cluster of names in Joshua 17:2 that closely approximate the roster on the ostraca and define Manasseh's allotment. Evidence that Shechem returned to prominence in the Hellenistic period comes from Ecclesiasticus 50:26 and from a critical assessment of Josephus' various references to the city and to Mount Gerizim, most notably in Antiquities (XI, 340 ff.), where it is said to be the chief Samaritan city.

Because the texts mentioning Shechem speak of the environs as well as the city, there has been an impulse to explore the region around Shechem, as well as the city ruin itself. G. Welter excavated a Middle Bronze Age II structure on the slopes of Gerizim above Balatah at Tananir (1931) and the Church of Mary Mother of God (Theotokos) on the summit of Mount Gerizim (1928). The American Joint Expedition studied the rock-cut tombs in Shechem's cemetery on the flanks of Mount Ebal, and modern road expansion has revealed others, one of them the cave tomb T-3 excavated by C. Clamer. The number of tombs identified is now about seventy. R. Boling of the American expedition reexcavated Tananir in 1968, and R. Bull excavated ell er-Ras from 1964 to 1968. In 1964, the American Joint Expedition began a more systematic regional survey, intended to examine the Shechem basin as a system. Fifty-four sites were explored in this effort, and 29 more were explored by German and Israeli teams, notably by the Deutsche Evangelische Institut, prior to 1967; by the Israel Survey in 1967-1968; and by I. Finkelstein and A. Zertal since. In addition, a series of chance discoveries in Nablus have been salvaged archaeologically in the past fifteen years, filling out the archaeological history of the pass in Roman times. I. Magen is at work on the major Hellenistic settlement on Mount Gerizim, which spreads south and west from the summit, and various sites in Roman Neapolis, and Zertal has excavated a probable Iron Age sanctuary and altar at el-Burnat on Mount Ebal (q.v.). The result has been to understand Shechem as a regional center, recognizing how the various points of access to the basin were guarded, how secure the population must have been to spread out into villages around the valley's flanks - where military posts and secondary market towns may be located - and what relationship Shechem may have had to such cities as Tappuah, Tirzah, Tubas, and Samaria.

E. Sellin began a systematic excavation at Tell Balatah in the fall of 1913. He returned in the spring of 1914. He focused first on the outcrop of fortification wall that Thiersch had noticed ten years earlier, tracing it northward to the northwest gate and south to where it gave out. He then found a second circumvallation inside the first and traced it to the gate. Sellin used long, 5-m-wide trenches from the mound's edge toward its center, to test the overall stratigraphy. He discerned four major periods in the site's history in the stratified buildings his narrow trenches revealed. He first dated them as Hellenistic, Late Israelite, Early Israelite, and Canaanite. In fact, they turned out to be Hellenistic, Israelite, Middle Bronze, and earlier - the earliest phase being equivalent to what he had found at Jericho, the Early Bronze and Chalcolithic periods. Sellin returned in 1926 and 1927 for four campaigns. He used his long, narrow trenches to explore the city's interior in the southeast and from the eastern perimeter inward. The former area, trench K, followed up on a remarkable chance discovery made by Balatah villagers in 1908: bronze weaponry, including a sickle sword. From this trench also came two cuneiform tablets, one a witness list and the other a text W. F. Albright deciphered as a teacher's appeal for remuneration. The other trench, designated L, revealed fortifications on the east side of the city, which were traced to the east gate. Sellin had by now seen that the fortification system was in several phases and would be a complex puzzle to work out.

Much of the rest of Sellin's work was concentrated on the west of the mound, in what would prove to be the acropolis. Just inside the arc of the city wall, he discerned what he called the palace, extending on either side of the northwest gate, and the massive structure of the Migdal Temple and its forecourt, altars, and pillar sockets, enclosed within what he termed the temenos wall (wall 900). Work within the elbow of the temenos wall brought the Germans to the uppermost of a series of courtyard complexes; some soil in the interiors of rooms was scooped out, but work was carried no deeper. Welter was appointed to replace Sellin as director, but only produced some plans, although excellent ones, and explored Mount Gerizim, as noted above. The expedition failed to record find spots carefully, to report stratigraphy in any detail, and to bring the account of the work to a synthetic presentation. Sellin regained the directorship and mounted a final season in 1934. He worked on his final report until l943. His records and his manuscript, along with many artifacts, were destroyed in Berlin during World War II.

The Joint Expedition to Shechem began in 1956 as the cooperative effort of Drew University in Madison, New Jersey and McCormick Theological Seminary, in Chicago, under the direction of G. E. Wright and B. W. Anderson. Conceived as a teaching excavation for young American, Canadian, and European scholars, it took into the field teams of as many as thirty researchers, a well-conceived recording system, and a plan to combine the soil deposition technique being perfected by K. M. Kenyon at Jericho with comparative ceramic knowledge based on W. F. Albright's work. A major aim was to recover as much as possible from the materials unearthed by Sellin and Welter and to tie the mound's story together. Methods became more and more sophisticated as the expedition continued and many more institutions became partners. The excavation at Shechem was the first to introduce cross-disciplinary research, including an association with geologist R. Bullard. The expedition, chiefly through its director, G. E. Wright, kept to the task of relating textual evidence to archaeological finds. The expedition entered the field with a reconnaissance season in 1956, and worked in 1957, 1960, 1962, 1964, 1966, and 1968. In the fall of 1968, Boling reexcavated Tananir, and in 1969 J.D. Seger tied the acropolis stratigraphy to an area of fine houses just to the north of the acropolis (field XIII). Salvage and clean-up work in 1972 and 1973 were carried out by W. G. Dever, who made several important discoveries in Sellin's "palace" precinct. Work reached bedrock in two locations and identified a total of twenty-four distinct strata, from the Chalcolithic to the Late Hellenistic period. Four major periods of abandonment were interspersed.

- Fig. 7 Map of the Nablus

region from Bull and Campbell (1968)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Map of the Nablus region showing the line of the stairway from the valley to the temple site.

JW: Also showing the location of Ancient Shechem center right

Bull and Campbell (1968) - Fig. 13 Map of the Shechem

environs from Bull and Campbell (1968)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of the Shechem environs locating the sites visited in the area survey.

Bull and Campbell (1968) - Roads and cities during

the Israelite period, 12th to 7th century BC from biblewalks.com

Roads and cities during the Israelite period, 12th to 7th century BC

Roads and cities during the Israelite period, 12th to 7th century BC

(based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

BibleWalks.com

- Fig. 7 Map of the Nablus

region from Bull and Campbell (1968)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Map of the Nablus region showing the line of the stairway from the valley to the temple site.

JW: Also showing the location of Ancient Shechem center right

Bull and Campbell (1968) - Fig. 13 Map of the Shechem

environs from Bull and Campbell (1968)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of the Shechem environs locating the sites visited in the area survey.

Bull and Campbell (1968) - Roads and cities during

the Israelite period, 12th to 7th century BC from biblewalks.com

Roads and cities during the Israelite period, 12th to 7th century BC

Roads and cities during the Israelite period, 12th to 7th century BC

(based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

BibleWalks.com

- Tel Balatah Archaeological Park in Google Earth

- Tel Balatah Archaeological Park on govmap.gov.il

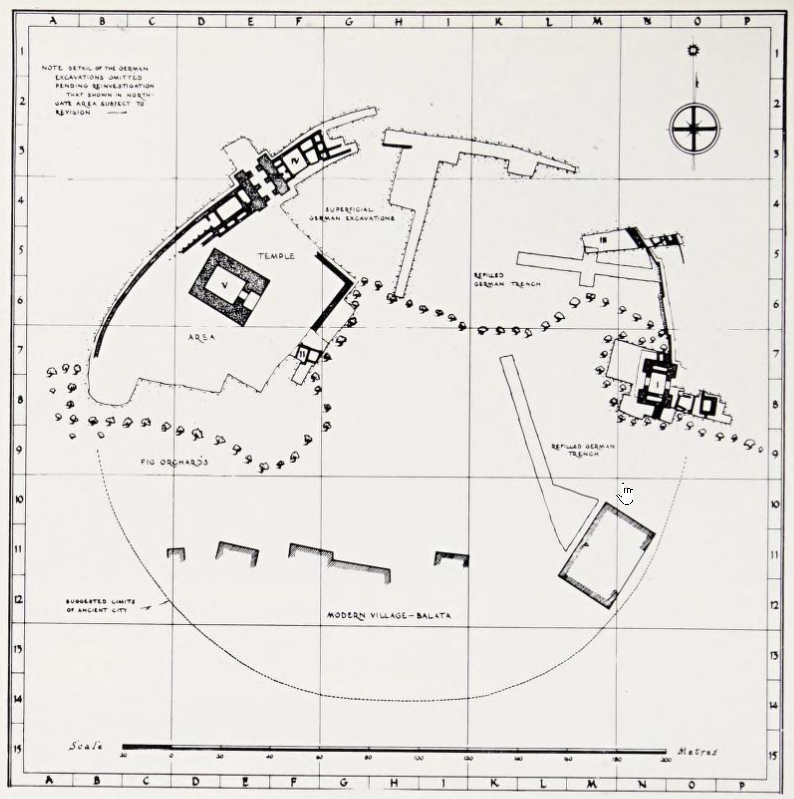

- Plan of the mound

of Tell Balatah from Stern et al (1993 v.4)

Tell Balatah: map of the mound, excavation areas, and plan of the principal

remains.

Tell Balatah: map of the mound, excavation areas, and plan of the principal

remains.

Stern et al (1993 v. 4) - Fig. 13 Plan of Shechem

tell with Fields (excavation areas) from Wright (1965)

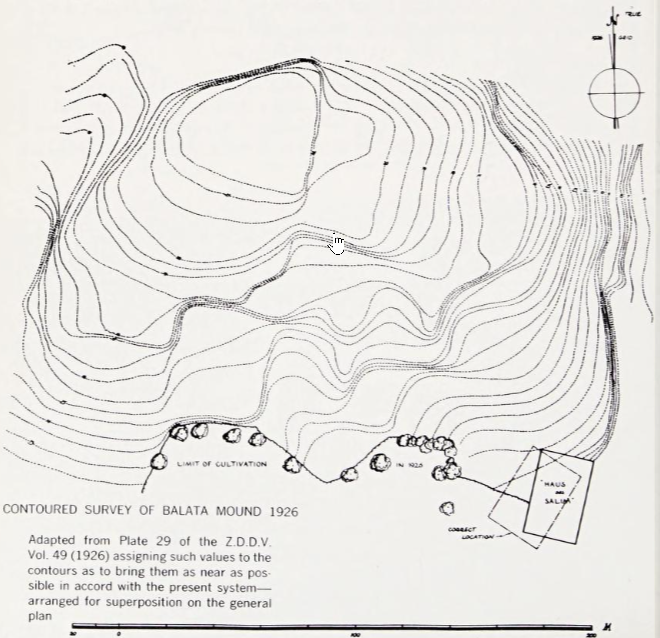

- Fig. 7 Contour Map of the Tell from Wright (1965)

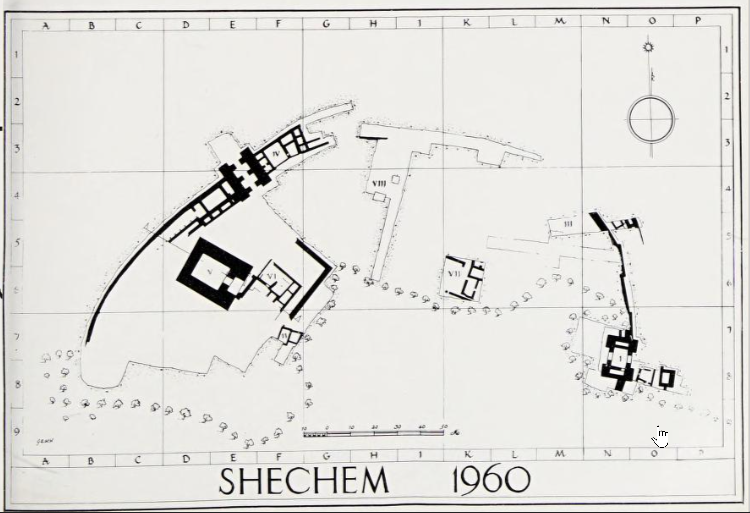

- Fig. 20 1960 Plan of Shechem

tell with Fields (excavation areas) from Wright (1965)

- Plan of the mound

of Tell Balatah from Stern et al (1993 v.4)

Tell Balatah: map of the mound, excavation areas, and plan of the principal

remains.

Tell Balatah: map of the mound, excavation areas, and plan of the principal

remains.

Stern et al (1993 v. 4) - Fig. 13 Plan of Shechem

tell with Fields (excavation areas) from Wright (1965)

- Fig. 7 Contour Map of the Tell from Wright (1965)

- Fig. 20 1960 Plan of Shechem

tell with Fields (excavation areas) from Wright (1965)

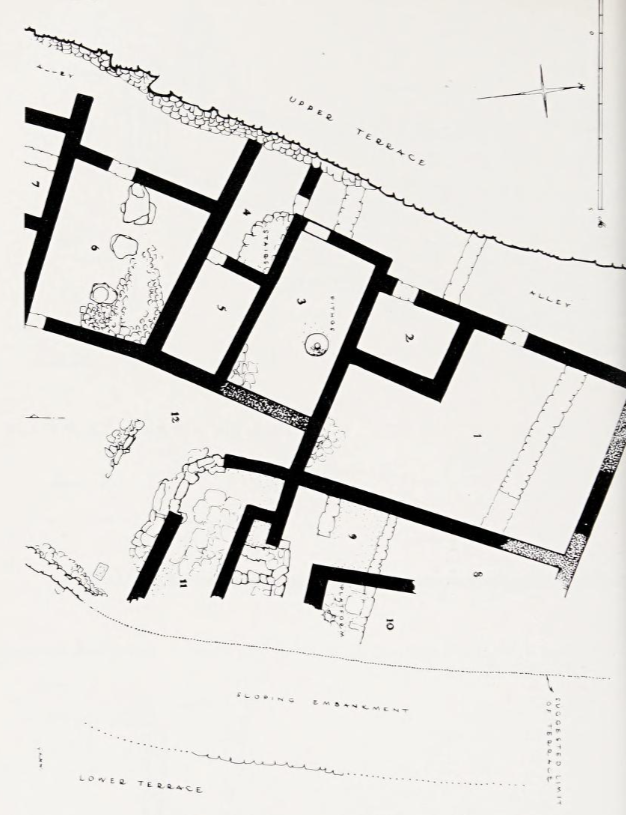

- Fig. 75 Plan of middle

terrace of Stratum IX B and A in Field VII from Wright (1965)

- Fig. 75 Plan of middle

terrace of Stratum IX B and A in Field VII from Wright (1965)

- from Edward F. Campbell in Stern et al (1993 v.4)

- based on the (American) Joint Expedition to Shechem which ran from the 1950s to the early 1970s.

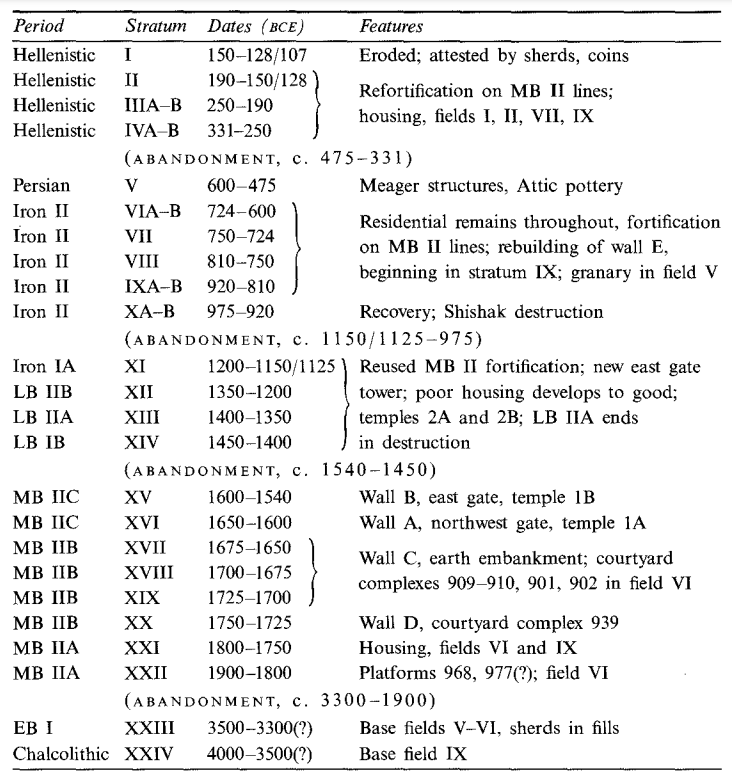

Phasing

PhasingStern et al (1993)

- from Crisler (2003)

New Courville—Tentative Correlation of Shechem strata with BC dates and events:

|

Date, c |

Stratum |

Description |

|

150-107 BC |

1 |

last city on tell, destroyed by John Hyrcanus |

|

190-150 BC |

2 |

|

|

225-190 BC |

3a |

|

|

250-225 BC |

3b |

|

|

300-250 BC |

4a |

|

|

331-300 BC |

4b |

Samaritans |

|

537-331 BC |

5 |

Israelite & Persian occupation |

|

587-538 BC |

6a & b |

Nebuchadnezzar resettles land; “Assyrian Palace Ware” (i.e., Babylonian) |

|

604-587 BC |

7 |

Destruction by Nebuchadnezzar |

|

731-604 BC |

8 |

First Assyrian deportation and occupation of Israel |

|

783-732 BC |

9a |

Rebuilding of city; grain warehouse built over LB temple |

|

850-783 BC |

9b |

Destroyed by the earthquake of Uzziah’s day, c. 783 |

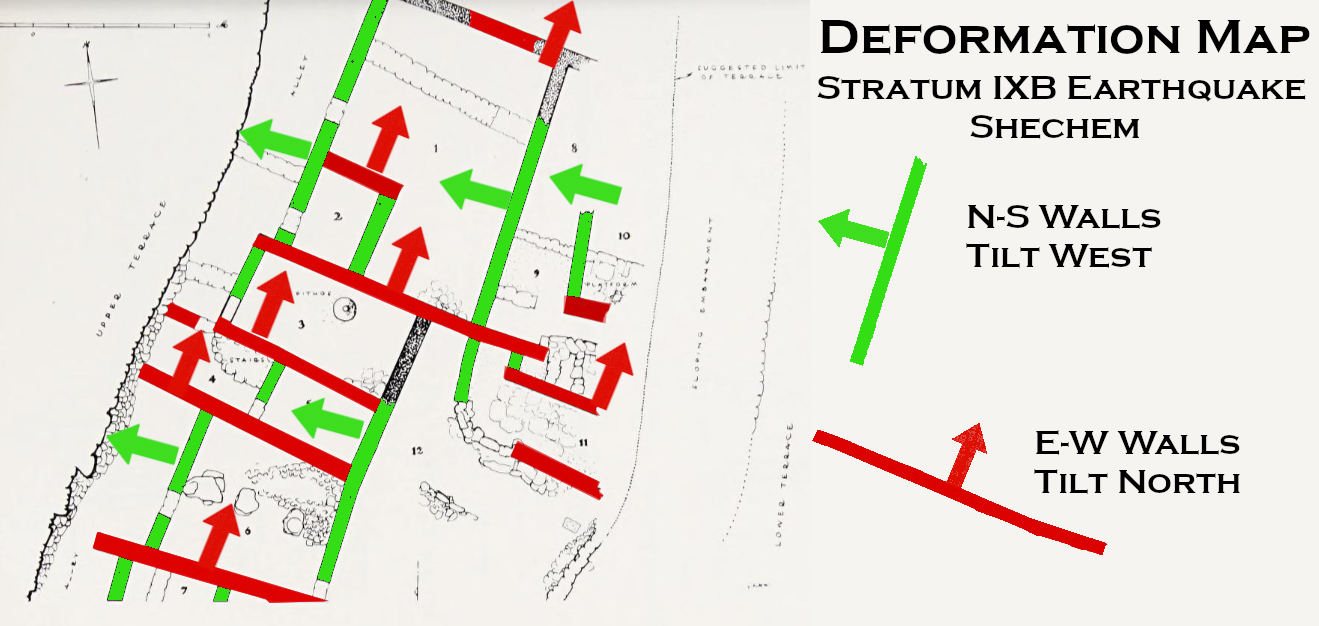

Our evidence for this stratum comes solely from Field VII, and the dating, while approximate, is tentative. In this sector the city of the ninth to eighth centuries sloped southeastward in the direction of the East Gate. Terraces were constructed to give the houses solid foundations, and one of them happened to cross in the center of Field VII (Fig. 75). It was between 13 and 14 m. wide, and it appears to have held that width throughout Strata IX through VII. This was because the terrace walls established in IX were rebuilt and reused three times before the destruction visited upon the city by the Assyrian army. Preceding IX and at the end of VII, the destructions visited upon the city are so massive as to cause major rebuilding and a change in city plans.

The reconstructed ground plan of IX B divides itself into three sectors (Fig. 75). The terrace wall to the left, 70 cm. wide, held the earth of the upper terrace in place. To the right of it on the middle terrace there was a narrow street which gave access to the complex, Rooms 1-5. Room 1 is over 5 m. wide, and it must thus have been an unroofed court with a small enclosure, Room 2, set into its southeast corner. Rooms 3-5 were presumably living quarters. Room 4 had a nicely built stone structure in one corner which may have been part of a stairway to a second story. Room 3 had the top part of a large jar sunk in its floor, neck and rim down. We assumed, of course, that it was a drain, except that there did not appear to be any outlet for the water (Fig. 75). Assistant supervisor Albert Glock, however, noted clear traces of burning around the periphery of the vessel, and called our attention to a similar installation in Stratum V A at Hazor (dated ca. 745-732 B.C.) and another from the latter part of the seventh century at Mesad Hashavyahu on the coastal plain. In these cases, it is quite clear that the vessels were ovens. It was a quick way to make an oven: simply to cut a large storage jar in two parts, and use the upper part, presumably because of the wide shoulders. The more typical house oven of any period is more complex; it is made of a special clay mixed with coarse binding material, and outside and inside layers of large sherds may be stuck into the mixture. A round pit in the ground was prepared; the material was formed in place around it and permitted to extend a few inches above ground. A fire built in it would then have hardened the walls.

Between Rooms 4-5 and 6 there is a wall, 7 m. long, which blocks passage southward. Rooms 6 and 7, accordingly, must be entered from another alley, access to which was somewhere south of our excavated area. Room 6 is a court, half roofed over on the northern side. Two wooden pillars on stone bases once supported the shelter. These bases are large boulders, crudely cut to cubic forms, ca. 50 cm. in diameter, two forming each base. The upper stones on the plan are quite crude and belong to Stratum IX A, as does also the large flat stone on an uneven base next to the door.

The third sector is along the eastern edge of the terrace, including Rooms 8-12. They rest on a kind of platform created to hold them up, but the edges are unclear because they have crumbled away down the slope. Later building has left the rest fragmentary, though more detail may make matters clearer when excavation here is completed.

The walls are only one stone in thickness, and they appear very insubstantial, though they remain standing to a height of 1 m., and in some places to 1.50 m. As we shall note subsequently, however, this type of wall is typical in houses of the ninth and eighth centuries at Shechem. While occasionally walls may be two stones in thickness, the single-stone wall, only some 40 cm. thick, is the more common. However, by the time a covering of 12 to 25 cm. of mud-plaster was put on each side, the wall width was more substantial, between 64 and 90 cm., probably representing 1 1/2 or 2 cubits.

All of the walls shown in Fig. 75 were peculiar in that the east-west walls tilted to the north, and the north-south walls tilted to the west. To field supervisor Horn this suggested that an earthquake may have been the cause; otherwise why was the tilting so consistent? Ashy destruction layers were present, though not found consistently throughout the stratum. If earthquake was the sufficient natural cause for the end of IX B, then we cannot date it other than to say that it probably occurred during the period approximately 880 to 830 B.C. It is of interest to note, however, that another Israelite provincial city, Hazor, has in its Stratum IX a city contemporary with ours. If a political interruption in the life of Israel is to be sought as the explanation for the end of Shechem IX B and Hazor IX, then it was probably the war between Ben-hadad of Damascus and Ahab of Israel (1 Kings 20). Ben-hadad had succeeded in taking his army into the heart of Israel and had invested Samaria itself. Ahab had gathered all of his provincial officers and troops, thus presumably leaving the provincial capitals virtually defenseless, before a severe defeat was visited upon Ben-hadad. We are not informed of the date of this event, but since it occurred before Damascus and Israel were allied against Assyria in the battle of Qarqar in 853 B.C., we will not be far wrong if we assume it to have been in the period between 860 and 855 B.C.23

23 For discussion see Benjamin Mazar, BA XXV, 1962, pp. 106-109.

Following some sort of violent disaster which befell IX B, radical measures were needed to shore up foundations and to rebuild house superstructures. In so doing, rearrangements of space were occasionally undertaken. A heavy accumulation of debris was leveled over the earlier floors. New ones were installed 20 in. above the lower floors on top of the debris, some of very fine flagstones. Others of tamped earth show on occasion several resurfacings. Doors were blocked. Court 1 was subdivided into rooms. The alley to the east of it had supporting walls running across it to the terrace wall. Room 6 was reused, but large flat slabs were placed on top of the earlier pillar bases, and another was installed next to the door, so that there were now three new flat bases for pillars to support the roof over the half-open court. To the east the platform at the edge of the terrace was kept in good repair, but the surviving architecture thus far is too fragmentary and complex to give a clear picture as to the nature of the rooms here. At the southeastern corner of the middle terrace the people of Stratum VI (seventh century) had dug through eighth-century levels down as far as IX B in some places.

The disentangling of Strata IX and VIII was so intricate a task that again we are left without clear evidence as to what brought the city of IX A to an end. Whatever it was, destruction was so bad that the people of City VIII had to rebuild completely, and they did so on an entirely new plan, disregarding the IX house walls entirely. In this case we surely can look to the wars between the Aramaean state of Damascus and Israel for the cause. Before an Assyrian army of Adad-nirari III destroyed Damascus in 805 B.C., Hazael, the Aramaean king whom the Assyrians called a “son of nobody” (i.e., a commoner), dealt blow after blow upon both Israel and Judah, until by about 810 B.C. Judah even had to pay tribute to him while Israel was completely at his mercy (2 Kings 12:17–13:23). Megiddo, Hazor and Tirzah all had a severe disrupting of city life at this time, and the end of Shechem IX A is probably to be attributed to the same disasters.

Ambraseys (2009) wrote "Crisler considers that ‘The destruction of Samaria

[Shechem] was probably due to Uzziah’s earthquake of 783 BC’

(Crisler 2003;

2004).

Uzziah's earthquake also known as the Amos Quakes struck around 760 BCE however multiple lines of evindence indicates there were

a couple of earthquakes around this time.

- from Crisler (2003)

By Vern Crisler

Copyright, 2003, 2006

Rough Draft

Donovan Courville was the first to note the difficulties that archaeologists have had in interpreting the archaeology of Shechem. [Courville, The Exodus Problem and its Ramifications, 1971, Vol. 2, pp. 172ff.] The most recent interpretation by Lawrence Stager, writing in Biblical Archaeology Review (Vol. 29, #4, p, 26), only highlights the problems pointed out by Courville.

I would agree with Stager’s conclusion that the Fortress Temple (Temple 1) was the temple destroyed by Abimelech, but we arrive at this conclusion on the basis of different premises. Stager’s basic conclusion is true, but his premises are false. (It’s possible in logic to have false premises and a true conclusion because the conclusion may be true for other reasons than those given in the false premises.) The premiss of New Courville is that the end of the Middle Bronze Age (specifically MB2c) should be downdated to the time of Abimelech, whereas Stager thinks that the excavators of Shechem invented a Late Bronze Age temple, and that the MB2c Fortress Temple actually survived down to Iron Age times (the strata in which the period of the Judges is placed according to conventional chronology). Thus, in Stager’s view, the MB2c Fortress Temple was destroyed by an Iron Age Abimelech.

2. SHECHEM IN THE BIBLE

Before discussing the archaeology of Shechem, let us see what the biblical text has to say about the city of Shechem.

a. The Time of Abraham:

Shechem is first mentioned in Genesis 12. Abraham had left Ur with his father Terah and had lived in Haran until the LORD called him to leave his country and kin. Abraham journeyed to the land of Canaan and there passed through Shechem. Obviously, the village or town was not called Shechem at that time since it was named after an individual living in Jacob’s time, but the Bible does not give us the original name of the village. It is not even clear that a town or village existed during Abraham’s day. It may have been little more than a watering-stop for those passing through on their way south. The biblical text says Abraham passed through the land to the place of Shechem (Gen. 12:6), rather than to the city of Shechem. So it’s possible that Shechem at this time was only a small religious center. This is indicated by the presence of a sacred tree¾the oak or terebinth tree of Moreh. This tree may have been repaired to often by the Canaanites in the land for liturgical purposes. On the other hand, it’s also possible that the sacred tree was from a later time, and the writer is giving a contemporary geographic location for where Abraham stopped. Whatever the case may be, we do know that after Abraham received the promise that his posterity would inherit the land of Canaan, he,

“built an altar to the LORD, who had appeared to him” (Gen. 12: 7).

The text seems to indicate that this altar was built near the terebinth tree, for Abraham went “as far as the terebinth tree of Moreh” (Gen. 12:6) where he received the promise, and thus it’s likely that he built the altar near the sacred oak.

b. The Time of Jacob:

We next see Shechem during the time of Abraham’s grandson, Jacob (Gen. 34). We are told that Jacob came to the city of Shechem (Gen. 33:18). Moreover, he “pitched his tent before the city,” and “bought the parcel of land, where he had pitched his tent, from the children of Hamor, Shechem’s father, for one hundred pieces of money” (Gen. 33:19). It is to be noted here that Jacob did not pitch his tent inside the city of Shechem, nor did he purchase land within the city of Shechem. The text says that he pitched his tent before the city, that is, somewhere close by, apparently within walking distance or within eyesight. Probably remembering what his grandfather had done, Jacob,

“erected an altar there and called it El Elohe Israel” (Gen. 33:20).

Since Jacob pitched his tent somewhere before the city, and purchased the parcel of land where he pitched his tent, and built an altar on this land, it follows that the altar was not built in the city, but before it. In fact, when Hamor came to visit Jacob, he went out to Jacob to speak with him (Gen. 34: 6). When Hamor had finished making covenant with the sons of Jacob (after the Dinah incident), he and his son Shechem came to the gate of their city, and spoke with the men of their city (Gen. 34:20). When Simeon and Levi effected their revenge on Shechem they came boldly upon the city and killed all the males (Gen. 34:25).

All of these location references show that Jacob and his sons were not living in Shechem, but were living somewhere close to it. After the killing of the Shechemites, Jacob could no longer stay in the land he had purchased but was divinely instructed to go to the city of Bethel and build an altar there to God (Gen. 35:1). Before leaving, Jacob commanded his household and all who were with him to put away any idols they had, and to purify themselves. When this was accomplished Jacob took the cultic paraphernalia and buried it all underground beneath the canopy of the sacred tree. This is the same tree that was mentioned in the text recounting Abraham’s encounter with God at the place of Shechem, as far as the “terebinth tree of Moreh.” The text, in describing what Jacob did with the idols, says,

“Jacob hid them under the terebinth tree which was by Shechem” (Gen. 35:4; emphasis added).

It’s likely that the parcel of land that Jacob had purchased contained this sacred tree, and provides the main motivation for Jacob’s purchase of the land, and his pitching his tent on the parcel of land. So it would seem then that a place just before the city, within walking distance, or within eyesight, was of great importance to Jacob, and would therefore be of great importance to Jacob’s descendents, the tribes of Israel. Whether or not the sacred tree was on Jacob’s land, it seems clear that the city of Shechem¾built by Hamor for his son¾was not built around the sacred tree but somewhere by it.

c. The Time of Joshua:

Shechem was appointed as a city of refuge after the Conquest of Canaan by the Israelites (Josh. 20:7). It was also the place where Joshua renewed the covenant with the tribes of Israel, and where they pledged to “serve the LORD” (Josh. 24:21). We are told that Joshua set up a large stone (what archaeologists call a masseba) and,

“set it up there under the oak that was by the sanctuary of the LORD” (Josh. 24:26).

Moreover, the bones of Joseph were,

“buried at Shechem, in the plot of ground which Jacob had bought from the sons of Hamor the father of Shechem….” (Josh. 24:32).

Something new appears to have been added to the sacred area (or “temenos”) where the sacred oak was located. Joshua placed a large stone at the foot of the tree, which was by the sanctuary of the LORD. It is not clear whether this sanctuary incorporated Abraham or Jacob’s old altars, or whether a new structure had been built. In any case, we can see that a new “temenos” had grown up around the sacred oak, and the important thing to notice about this temenos is that it is not inside the city of Shechem. We know this because in our previous discussion we noted that the sacred tree was by the city, not in it, and hence the temenos must also have been by the city.

d. The Time of Abimelech:

One of Gideon’s concubines, who had been living in the city of Shechem, bore a son to him by the name of Abimelech. Israel entered into a state of apostasy after the death of Gideon, and the history of Abimelech is an illustration of this. During their time of apostasy, the Israelites worshiped the baals, specifically “Baal-Berith”¾Baal of the Covenant. It’s possible that “El-Berith”¾“God of the Covenant”¾was another name used to describe this god, cf., Judg. 9:46. (There is no need for fanciful source theories to explain this.) When Abimelech was grown, he entered into a conspiracy with the men of Shechem to kill all of the sons of Gideon. So he persuaded his Shechemite brothers (born to Gideon’s Shechemite wife) to convince the men of Shechem to join him. The men of Shechem took money from the “temple of Baal-Berith” and gave it to Abimelech to murder his seventy brothers at Ophra. Abimelech hired a few worthless men and together they killed sixty-nine of the sons of Gideon. One of the sons of Gideon escaped and later prophesied on Mount Gerizim regarding the future destruction of both Abimelech and Shechem. Abimelech was made king at the temenos that had grown up around the sacred tree. Let us note very carefully the language of the text:

“And all the men of Shechem gathered together…and they went and made Abimelech king beside the terebinth tree at the pillar that was in Shechem” (Judg. 9:6).

Something has changed here. The sacred tree and masseba are no longer by the city, or before the city. Instead, they are in the city. It would seem that the old city of Shechem¾patriarchal Shechem¾was no longer in existence, and that a new city had been built up around the sacred tree and temenos. It is the position of the New Courville chronology that patriarchal Shechem was indeed destroyed sometime after the Conquest, and that the new city of Shechem was built up thereafter around the temenos plot that had originally been purchased by Jacob. This is why Abimelech can be crowned by the sacred tree in Shechem. Three years after he was crowned king, however, Abimelech and the men of Shechem had a falling out (Judg. 9:22). Gaal, the son of Ebed, came to Shechem with his brothers, and bragged that if only the men of Shechem would make him governor, he could rid the Shechemites of Abimelech’s rule. The actual governor of the city, Zebul, heard these words and warned his overking, Abimelech, that Ebed and his brothers are,

“fortifying the city against you” (Judg. 9:31).

Fortifying a city would consist of strengthening the walls and the gates, or repairing weaknesses, or building new defensive walls, etc. It came to pass that Abimelech grew tired of Gaal and his boasts, and he and his men ambushed Gaal’s army and chased them to the gate of the city, where,

“many fell wounded, even to the entrance of the gate” (Judg. 9:40).

Evidently, Abimelech was prepared to defeat an army in the open, but the gate of the city was too strong for the forces he had on the field, so he was only able to chase Gaal’s army to the gate. Some time must have passed. Gaal and his men had time to lick their wounds, and while doing that, they probably limited their boasts just to replacing Governor Zebul, being careful not to mention Abimelech. In the meantime, Abimelech took up residence at Arumah. Zebul, however, found that he could no longer tolerate Gaal, and drove him and his brothers out of the city. The next morning, the people of Shechem went out into their fields to work, and spies told Abimelech about it. He and his men laid in wait the next day and when the people of Shechem came out again to work in the fields, Abimelech and the company that was with him,

“rushed forward and stood at the entrance of the gate of the city; and the other two companies rushed upon all who were in the fields and killed them” (Judg. 9:44).

When the leaders of Shechem, “the men of the tower” heard that the gate had been taken, they entered into the stronghold of the temple of El-Berith, along with a number of others until about a thousand men and women had made it into the “protection” of the Temple. When Abimelech heard about it, he took his men up to Mount Zalmon and instructed them to cut some wood. They brought the wood back and set the boughs around the great temple of El-Berith, and,

“set the stronghold on fire above them, so that all the people of the tower of Shechem died, about a thousand men and women” (Judg. 9:49).

Though it doesn’t give a strict chronological order, i.e., the order of battle, the Bible summarizes all these events, and the fate of the city on that day, by saying,

“So Abimelech fought against the city all that day; he took the city and killed the people who were in it; and he demolished the city and sowed it with salt” (Judg. 9:45).

Abimelech tried to do the same thing to the city of Thebez. Like Shechem, Thebez also had a “strong tower in the city” (Judg. 9:51). It was to this tower that all the people of Thebez fled to escape Abimelech. Nevertheless, when he tried to burn down the tower, a woman dropped a millstone from the tower¾like Wormtongue dropping the Palantir in Lord of the Rings!¾and it critically wounded Abimelech in his head. Abimelech did not want it to be said that he had been killed by a woman, so he had his armorbearer run him through with a sword. The death of Abimelech and of the men of Shechem is stated to be in fulfillment of the prophecy of Jotham, the last surviving son of Gideon (Jerubbaal), in repayment for their treachery against the sons of Gideon.

Special Note: The “Diviners’ Terebinth Tree” mentioned by Gaal in Judges 9:37 was a different tree from the one Abimelech was crowned at, since Gaal was looking outward from the gate of the city to men coming down the hillside in the distance. The terebinth tree where Abimelech was crowned was inside the city next to the masseba (Judg. 9:6).

e. The Time of Jeroboam, and later:

The Bible says that Jeroboam built Shechem and Penuel. The Hebrew word “banah” can mean either build or repair (i.e., refortify). For instance, we are told that Solomon “built” Gezer (1 Ki. 9:17), but Gezer had a long history before Solomon’s time (Josh. 10:33). This means that Jeroboam’s building of Shechem could just as easily have been a repair of, or enlargement of, the city. Thus, there is little reason to adopt Courville’s suggestion that Shechem lay in ruins from Abimelech’s time to the time of Jeroboam (cf. Exodus Problem, p. 174). Indeed, it is the position of New Courville that Labayu rebuilt the city of Shechem during the Amarna period, and that Jeroboam was enlarging or repairing Labayu’s old city. Apparently, Shechem was only a temporary capital for Jeroboam, for he seems to have moved eventually to Tirzah (compare 1 Ki. 14:2, 7, 11, 12, 17). Moreover, the Bible says the city was in existence during the time that Jeroboam was still in Egypt, i.e., before he had become king:

“Now Rehoboam went to Shechem, for all Israel had gone to Shechem to make him king. So it was, when Jeroboam the son of Nebat heard it (he was still in Egypt, for he had fled from the presence of King Solomon and had been dwelling in Egypt), that they sent and called him” (1 Ki. 12:1-3).

Somebody must have rebuilt the city of Shechem from scratch, and it doesn’t appear to have been either Jeroboam or Rehoboam. Indeed, Shechem was in existence during David’s time, since David rejoices in the fact that he will divide, or portion out, Shechem (as one portions out spoil, cf., Psalm 60:6 & 108:7). Thus, the city must have been rebuilt from scratch sometime between the time of Abimelech and the time of David, about a 164 year stretch. The only other mention of Shechem after Jeroboam’s refortification of the city is in Jeremiah 41:5, where were are told,

“that certain men came from Shechem, from Shiloh, and from Samaria, eighty men with their beards shaved and their clothes torn, having cut themselves, with offerings and incense in their hand, to bring them to the house of the LORD.”

This shows that the city was in existence during Jeremiah’s day, in the 6th century.

3. THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF SHECHEM

a. Site Location:

Neapolis¾Jerome placed Shechem at Neapolis, a Roman city meaning New City, pronounced today as Nablus. (Cf. G. E. Wright, Shechem: the Biography of a Biblical City, 1964, p. 5.). Both the explorer Edward Robinson and the British Survey of Western Palestine agreed that ancient Shechem was under Neapolis. A German scholar, A. Eckstein, wondered whether “this new city [Neapolis] was built on the site of ancient Shechem or in its vicinity….” (Ibid., p. 6). Gabriel Welter, one of the excavators of Balatah, believed that ancient Shechem was under Neapolis (Ibid., p. 29).

Tell Balatah¾Church historian, Eusebius, in his Onomasticon (dictionary of biblical sites), as well as a pilgrim in an account of his travels, regarded ancient Shechem to be located near Balatah. The sixth century Madeba mosaic map directs pilgrims to Balatah. In 1903, German scholar Hermann Thiersch uncovered the ruins of Tell Balatah, and believed that “the earlier supposition (Nablus) is refuted” (Ibid., p. 2). Since then, excavators from Ernst Sellin to G. E. Wright, have regarded Tell Balatah as the site of ancient Shechem. Wright says,

“The problem of the location of a great city was solved. Eusebius was right after all, and Jerome was wrong” (Ibid., p. 8).

We have occasion, however, to believe that perhaps both were right. In the New Courville chronology, the Israelites were the bearers of MB1 pottery, and during their re-urbanization phase, adopted the new MB2a pottery, which became the prototype for the pottery of Canaan until the end of the Middle Bronze age. However, not all went well for the Israelites after the Conquest. Within a few years of the Conquest, sometime during the MB2a period, the Egyptians of the reign of Sesostris 3 came up against Shechem and defeated it, for,

“his majesty reached a foreign country of which the name was skmm. Then skmm fell, together with the wretched Retenue” (Ibid., p. 5).

In our opinion, the fall of the old city to the Egyptians must have left the city in ruins, and the sacred area by the old city¾the temenos¾became the center of a new city. Thus, those who believed the ancient city of Shechem was under Nablus were probably correct, and future excavations at Nablus (if there are any) should reach Early Bronze 3 levels¾the time of Jacob per NCI. At the same time, those who believe ancient Shechem was located at Tell Balatah are correct, for this was the city of Shechem from the early settlement period down to the time of Abimelech, and later of Jeremiah.

Note: For an overview of all the sites in the Shechem area, see “The Shechem Area Survey,” BASOR, 190, p. 19, prepared by Edward F. Campbell. Early Bronze pottery is found at some sites, such as Khirbet Kefr Kuz, Tell Sofar, etc. Ephraim Stern points out that Khirbet Makhneh el-Fauqa, about 2.5 miles south of Balatah has EB3 pottery and concludes that “the region’s Early Bronze Age town must have been there.” (New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, 4: 1347.) It is curious that Campbell failed to mention that this town contained EB3 pottery. It should be noted, however, that none of the sites (sans Balatah and Nablus) that were surveyed by the Campbell team were actually excavated. The results were based on a “surface survey” and Campbell warns about drawing conclusions about the existence or non-existence of a site (during a particular archaeological period) on the basis of the absence of pottery, or the presence of a rare sherd or two, which could easily have been dropped by a passing shepherd (p. 21). Our view is that patriarchal Shechem may lie under present-day Nablus, and might be found given more thorough excavations. However, since it’s a modern city, it may be hard to do a thorough excavation, and it is also possible that the Romans cleared the site down to bedrock before building their New City. It is also possible that patriarchal Shechem is not under present-day Nablus, and that a more thorough excavation of the other 39 sites around the Nablus-Shechem area might turn up EB3 pottery indicia—the period we have correlated with the patriarchs. If Nablus turns out not to be the best site, then our second choice would be el-Fauqa as noted above.

b. Excavations

Ernst Sellin began the first excavations of Tell Balatah. Besides discovering gates and walls, the most important discovery was the house of the Covenant-God (El-berith) that Abimelech had destroyed. This was a “migdal” or fortress temple, and corresponds to what later excavators would call Temple 1.

In 1956, G. E. Wright led the most modern, scientific excavation of Tell Balatah. This is known as the Drew-McCormick Excavations, and consisted of Wright, Dean Anderson, Lawrence Toombs, Robert Bull, and Douglas Trout. This was the first truly modern excavation at Shechem using the techniques pioneered by Kathleen Kenyon at Jericho. The results of these excavations were reported in several BASOR articles, usually titled, “First Campaign at Tell Balatah (Shechem),” “Second Campaign,” etc., all the way up to “Eighth Campaign” published in 1971. In the meantime, Wright published the results of the work up to 1965, titled Shechem: the Biography of a Biblical City. These publications provide the most scientific analysis of the stratigraphy of Tell Balatah (though excavations are continuing).

c. The Fortress Temple

In my opinion, to talk about Shechem and its relation to the Bible, one must talk not only about the Fortress Temple, but also about the fortifications of Shechem. Lawrence Stager discusses the Temple, but he fails to discuss the fortifications of the city. The reason the fortifications are important is that the Bible says Abimelech not only destroyed the Temple, but also destroyed the city itself, and sowed it with salt. We should expect then, that the Temple and the fortifications of the city would be destroyed at the same time. Failure to keep this correlation in mind makes it impossible to understand the history of Shechem.

Stager realizes what the problem is with respect to the Temple. He agrees that Sellin found the Fortress Temple destroyed by Abimelech, but since this Temple is dated to the MB2c strata, which is much too early for Abimelech’s time on conventional chronology (about a 450 year difference), he has to find a way to get the Temple out of the Middle Bronze Age and bring it down to the Iron Age 1 period. (Readers should remember that conventional chronology mutilates the biblical period of the Judges, reducing it by about 200 years.) Stager says,

“There is no question that Shechem in antiquity was crowned by an impressive Fortress-Temple. The problem concerns the date. Wright and Bull dated the construction of the Temple to the end of the Middle Bronze Age, about 1650-155 B.C.E. [sic]. They called this building Temple 1 but gave it a lifespan of only about 100 years; they believed that Temple 1 had been replaced after a gap in occupation…by a much smaller and completely different temple¾Temple 2¾built on the ruins of Temple 1. This very simple and modest Temple 2 became Wright’s candidate for the temple of El-berith mentioned in Judges 9¾a rather strange mistake for him to have made…If the tragic story of Abimelech and the Shechemites had any realistic elements in it, one would have considered Temple 1 a much better candidate for the charnel house in which one thousand Shechemites were incinerated than the undersized Temple 2” (Biblical Archaeology Review, 2003, Vol. 29, No. 4, p. 29).

I agree to a certain extent with Stager’s point here, but then he says,

“In my view, Temple 2 is wholly illusory, and Shechem’s mighty Fortress-Temple lasted well into Iron Age I (1200-1000 B.C.E. [sic]), the period of the Judges [sic] and the Biblical episodes involving Abimelech. Temple 1 was not destroyed until about 1100 B.C.E. Once this great temple is redated, we can see a variety of correlations between the archaeological remains and the Biblical text” (Ibid., p. 29).

Here is what must be regarded as a desperate move by a conventional chronologist, one who recognizes that Temple 1 is the Fortress Temple destroyed by Abimelech, but who cannot reconcile its MB2c date to the period of Abimelech as described in the Bible. So what does he do? He in effect attacks the competence of the excavators! This is not the first time this has happened. Kathleen Kenyon’s methodology at Samaria was initially attacked by archaeologists [such as Wright!] because they found the archaeology of the city to be out of accord with the biblical text, as interpreted through the lenses of conventional chronology. So now we have the same thing happening. So glaring is the anachronism between the archaeology of Shechem and the biblical text, as interpreted through the lenses of conventional chronology, that Stager is willing to challenge, in effect, the competence of the field excavators of Shechem. He says,

“How Wright and Bull misdated the temple is an interesting study in archaeological analysis” (Ibid., p. 29)

Now Stager is a scholar, and his essay was first published in a Festschrift for one of the Shechem excavators, Edward F. Campbell, in the book Realia Dei, 1999. Since Stager is a scholar, one needs to respect his contributions on these topics. However, respect for Stager’s status as a scholar doesn’t mean non-scholars have to slavishly follow everything he says. This is especially true if he’s attacking other scholars, and specifically, the experts who did the field work at Shechem. We have to evaluate the putative evidence he presents against the conclusions of these men, and determine whether it holds up under scrutiny.

Alarmingly enough, Stager devotes two whole paragraphs to challenging the Drew-McCormick view that a Late Bronze age temple came between the Fortress Temple and the Iron age grain warehouse. In the first paragraph, he disagrees with Wright and Bull’s distinction between the walls of the LB temple, and the walls of the IA warehouse, and he claims that Temple 2 was “conjured into existence” (Ibid, p. 31). In the second paragraph, he attempts to refute Wright’s distinction between walls. The reason wall 5704 is wider than the one above it, 5904, is that the latter had been either “partially robbed out” in antiquity or “partially eroded.” The different appearance of wall 5703 from wall 5903 above it, noted by the excavators, is denied by Stager, who says he’s “not convinced that there is a really significant difference between these two course,” and that the real difference is that softer limestone was used for the granary walls and the Temple 2 walls from what had been used in Temple 1 (cf. Ibid., p. 31).

Stager refers to Wright committing a “strange mistake” in not recognizing Temple 1 as the Temple destroyed by Abimelech. It should be noted, however, that as early as 1956 Wright believed that Temple 1 was the Fortress Temple of Abimelech’s time. He said that Shechem “contained the largest temple so far known in pre-Roman Palestine. This structure, some 21 m. long by 26 m. wide [about 86 ft, 6 in.], had walls ca. 5.30 m. thick [about 16 ft. 8 in.], the thickness of a city fortification; it must surely have been the temple of ba’al berit (“Lord of the Covenant”) mentioned in the Abimelech story….” (G. E. Wright, “The First Campaign at Tell Balatah (Shechem),” BASOR, 1956, Number 144, p. 9). Thus the 1956 G. E. Wright would have been an ally of Lawrence Stager. Note what Wright says. He says that Temple 1 “must surely have been” the temple destroyed by Abimelech. He seems to have had very little doubt about it.

In 1956, Wright said that the Shechem Fortress Temple could not be dated, but believed that it “was probably still in existence during the twelfth century or early in the period of the Judges, when it was known as the temple of the ‘Lord of the Covenant’ (Baal-berith…) which Abimelech destroyed” (G. E. Wright, The Biblical Archaeologist, 1957, Vol 20: 1, p. 25). He further argued that the grain warehouse was on top of Temple 1: “Over the ruins of the temple…a new building was erected….[T]his new thick-walled building was a granary….” (Ibid., p. 25).

Even as late as 1961, both Wright and Toombs were holding out that Temple 1 was the one destroyed by Abimelech: “The temple on the city’s western side, together with its immediate surrounding, is referred to as Field V. This great structure, which must certainly be identified with the ‘house of Baal-berith’ (Judg. 9:4; or ‘El-berith,’ 9:46), was completely unearthed by Sellin in 1926” (L. Toombs, G. Wright, “The Third Campaign at Balatah (Shechem),” BASOR, 1961, Number 161, p. 13). However, in the same issue, p. 28ff., field supervisor Robert Bull reported on the presence of a structure above Temple 1. This structure, Temple 2, “undoubtedly falls within the LB period, judging from the quantities of LB pottery associated with the building of the podium in its first phase.”

The evidence for an LB temple must have been so overwhelming that Wright eventually had to give up Temple 1 as the temple of Abimelech. This view is completely at odds with the archaeological evidence, but was forced on Wright by the straightjacket of conventional chronology. By the time he wrote his book on Shechem, he no longer identified Temple 1 as the temple destroyed by Abimelech, but opted for Temple 2 (cf. Shechem, p. 101).

Thus, Stager, in so far as he thinks Wright was eager to “conjure” up a building between the Fortress Temple and the grain warehouse, simply fails to note the history of Wright’s views on the archaeology of Shechem. If anyone wanted to associate the Fortress Temple with Abimelech, it was Wright. Eventually, however, he had to take the archaeological evidence seriously, and give up his previous views, views that Stager is now trying to resurrect. So we must assert here that there is reasonable doubt about who is making the “strange mistake” in his interpretation of the stratigraphy of Shechem. Wright devotes 8 pages of his book to discussing the Late Bronze Age temple, and anyone who wants to compare his discussion with Stager’s two paragraph discussion is welcome to do so. (The BASOR articles are also helpful.) As an example, Wright and Bull didn’t just find differences in the walls between the LB temple and the grain warehouse. They also found different floors (Wright, Shechem, p. 98). Moreover, not only were they able to find the LB temple below the grain warehouse and above Temple 1, they were also able to distinguish two phases of it, LB phase 1 and LB phase 2!

I note also that Stager is inconsistent. On the one hand, he implicitly attacks the competence of the archaeologists when they discover an LB2 temple between the Fortress Temple and the grain warehouse. At the same time, however, Stager praises the archaeologists for their work in excavating and describing Temple 1 (cf., BAR, p. 31).

Courville, in his discussion of Shechem, argued that Wright should have kept to his earlier view that Temple 1 was the Fortress Temple of Abimelech’s time (cf. Exodus Problem, p. 185). Unlike Stager, however, I agree with Courville that the best solution would be to date the Temple down to the era of Abimelech by dating MB2c down to the era of Abimelech. Unfortunately, conventional chronologists still have their heads stuck in the sand, because they don’t¾as one politician used to say it¾have the courage to change.

What is missing from Stager’s discussion is any kind of acknowledgement of just how seriously the archaeology of the fortifications of the city of Shechem contradict an Iron Age destruction of Shechem. Wright could only say that the fortifications of Shechem “during the subsequent Israelite and Samaritan periods is shrouded with many obscurities” (Shechem, p. 79).

4. INTERLUDE

In his book, The Exodus Problem and its Ramifications, Donovan Courville called attention to a four hundred year gap that exists in the archaeology of Shechem (p. 177). This was based on statements of Wright and his team that they could not find any evidence of occupation of the city between the 8th and 4th centuries.

“Thus far in two seasons we have found no clear evidence of any occupational debris at Shechem between the eighth and the fourth centuries B. C.” (BASOR, 148, p. 24.)

This was also stated earlier in the same article: “No clear evidence has been found for habitation on the site between the eighth and fourth centuries” (p. 13). This means that no archaeological material was found, not that there was no history of Shechem during this period. Courville says that this view of an archaeological dark age persisted until the end of the excavations in 1963. Wright, in his book Shechem, writing in 1965, says that the 6th, 5th, and 4th centuries were periods of weakness for Shechem (p. 149). He does relate stratum 6 to the 7th century and stratum 5 to the 6th century (pp. 166, 167), but it’s

not clear whether he is revising his earlier view of no occupational debris, or presupposing it. He states that the team early on believed that stratum 5 had been lost or eroded away, but subsequent investigations revealed a round house that they felt could be attributed to stratum 5 (Wright, p. 167). In addition, they discovered a “definite level” for stratum 5, characterized by poverty, which was in their view subsequently destroyed by the Persians.

Thus, it would be a mistake to hold that Wright and company were not able to find anything between the 8th and 4th centuries, despite the paucity of indicia for the levels ascribed to these centuries. Courville gave an explanation for this presumed four hundred year gap in terms of his redating of the MB2c period down to the time of Abimelech. This was based on the statements of E. Campbell that a gap existed in the archaeology of Shechem from the first half of 12th century¾which is about 1175¾to the ninth century (800’s). However, there may be a simpler explanation for the “gaps” in the later history of Shechem. I could not find in the writings of Wright and company much of a discussion as to why stratum 6 was assigned to the 7th century (to be regarded as the strata of the Assyrian occupation). There was little that remained of stratum 6, but Wright dated it by “Assyrian Palace Ware” which he found in considerable quantity (Wright, p. 164). However, Peter James, et al., call attention to the fact that this pottery may be Neo-Babylonian rather than Assyrian (Centuries of Darkness, p. 181). They reference the archaeologist, John Holladay, who wrote the essay “Of Sherds and Strata: Contributions toward an Understanding of the Archaeology of the Divided Monarchy” published in Magnalia Dei [the Mighty Acts of God], a memorial volume for G. E. Wright. Holladay says,

“This regular conjunction of ‘Assyrian’ wares with late seventh-century forms raises the question of the proper dating and historical attribution of the ‘Assyrian Palace Ware’ found in Palestinian sites. In the past, it has generally been attributed to the Assyrian occupying forces of the late eighth century B. C. Recent studies based on the Nimrud excavations, however, suggest that the floruit of ware like that at Tell Jemmeh, Tell el-Far’ah (N), Samaria, Shechem VI, Ramat Rahel VA, En Gedi, etc., should be placed in and following the last days of the Assyrian empire….[T]he presence of these late forms of ‘Assyrian’ ware in unquestionably late seventh-century Palestinian stratification…becomes an embarrassment unless we recognize them as actually post-Assyrian in date. That is, we must recognize them as witnessing to a Babylonian influence in at least the aforementioned sites.” (Magnalia Dei, p. 272.)

If this reassignment of “Assyrian” palace ware to the Babylonian period is correct, then it becomes possible to close up some of the gaps in the later history of Shechem, as illustrated by the following chart:

New Courville—Tentative Correlation of Shechem strata with BC dates and events:

|

Date, c |

Stratum |

Description |

|

150-107 BC |

1 |

last city on tell, destroyed by John Hyrcanus |

|

190-150 BC |

2 |

|

|

225-190 BC |

3a |

|

|

250-225 BC |

3b |

|

|

300-250 BC |

4a |

|

|

331-300 BC |

4b |

Samaritans |

|

537-331 BC |

5 |

Israelite & Persian occupation |

|

587-538 BC |

6a & b |

Nebuchadnezzar resettles land; “Assyrian Palace Ware” (i.e., Babylonian) |

|

604-587 BC |

7 |

Destruction by Nebuchadnezzar |

|

731-604 BC |

8 |

First Assyrian deportation and occupation of Israel |

|

783-732 BC |

9a |

Rebuilding of city; grain warehouse built over LB temple |

|

850-783 BC |

9b |

Destroyed by the earthquake of Uzziah’s day, c. 783 |

The correctness of this revision of the chronology of Shechem would be strengthened if evidence of an earthquake could be found in stratum 9b. Indeed, it was the view of one of the field supervisors, S. Horn, that city 9b was destroyed by an earthquake. Wright says,

“All of the walls shown in Fig. 75 [in Wright’s Shechem] were peculiar in that the east-west walls tilted to the north, and the north-south walls tilted to the west. To field supervisor Horn this suggested that an earthquake may have been the cause; otherwise why was the tilting so consistent? Ashy destruction layers were present, though not found consistently throughout the stratum. If earthquake was the sufficient natural cause for the end of IX B, then we cannot date it other than to say that it probably occurred during the period approximately 880 to 830 B.C. [sic].” (Shechem, p. 153.)

However, since the grain warehouse was built in Jeroboam 2’s time per Wright, there is no reason why the earthquake that destroyed Shechem 9b could not have been as late as Jeroboam and Uzziah’s time, with 9a being the rebuilding of the city after the destructions. The only thing preventing this, I think, is the uncertain chronology brought about by the misdating of the “Assyrian” palace ware, thus pushing all strata to earlier times.

The end of Shechem 9b correlates to the end of Hazor 9, which was destroyed by a “conflagration” (E. Stern, New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Vol 2, p. 606; Wright, Shechem, p. 153). Wright thinks both destructions were due to Ben-hadad’s attacks against Ahab, though the Bible does not mention anything about Shechem in connection with this war. A palace at Megiddo stratum 5a-4b was also destroyed at this time, and a stratum 4a stable was built in its place. Currently, archaeologists adopt the strained view that Megiddo 4a was the time of Solomon and that he demolished a perfectly good palace and put a stable in its place. However, the above revision enables us to see that the palace probably came down as a result of Uzziah’s earthquake, and that it was the 8th century Israelites who decided to put a more functional building in its place. In addition, the end of Shechem 9b would correlate to the end of Building Period 2 at Samaria, which also suffered a catastrophe.

5. THE FORTIFICATIONS

Both Wright and Stager believe that Abimelech destroyed the temple of Shechem circa 1175 BC (or whenever Abimelech lived), but they differ as to which temple was destroyed. Wright believed at first that it was the migdal or fortress temple that was destroyed by Abimelech, but he subsequently gave this view up and adopted the theory that the LB temple was destroyed by Abimelech, and that the migdal was destroyed at the end of the Middle Bronze age. He says:

“It was noted…that Shechem has a gap in its history as a city of nearly a century’s duration, between ca. 1540 and 1450 B.C. [sic]. That Temple 1 was completely destroyed in the destruction of the city by the Egyptians [sic] is indicated by the fact that the rebuilding in the Late Bronze Age, perhaps by a father or grandfather of Lab’ayu, is quite different from the original structure.” (Wright, Shechem, p. 95.)

As we have seen, Stager rejects Wright’s view, and denies the existence of an LB temple. He dates the migdal’s destruction to the Iron age. Thus, both Wright and Stager hold that Abimelech’s destruction of the Shechem temple (whichever it was) took place in the Iron age¾the period usually ascribed to Abimelech in conventional chronology. The view of Courville, however, is that it’s not just the temple that needs to be explained, but also the destruction of the city itself¾its walls and gates. If conventional chronology is correct, why is there no evidence for the destruction of Shechem’s fortifications between the MB2c strata and the Iron 2 strata? Courville says,

“[I]f this assumption [that the migdal survived to Abimelech’s day] were to be considered permissible, then there should be archaeological evidence of an additional and later destruction [of the East gate] between Middle Bronze IIC, in the 16th century, and the much later destruction c. 800 B.C. After all, the Abimelech story emphasizes the total and complete destruction of the city with only incidental mention of the burning of the roof over the heads of the people who had gathered in the hold for refuge.” (Exodus Problem, Vol. 2, p. 181.)

Courville argued that the massive MB2c temple was the temple destroyed by Abimelech, and that the destruction of the city’s fortifications at the end of MB2c should also be ascribed to Abimelech: “The date however is not 1600-1550 B.C. When it is recognized that the proper background for the Conquest belongs to the end of Early Bronze, then this destruction in Middle Bronze II C is to be correlated with the period of the late judges, and this is where the story of Abimelech is found in Scripture.” (Exodus Problem, Vol. 2, p. 186.) It hardly needs to be said that New Courville agrees with this aspect of Courville’s chronology.

If Stager’s claim is false that the MB2c migdal of Shechem survived down to the Iron age, it might be thought that there is evidence for a destruction of temple 2b, the one Wright eventually decided on as the temple destroyed by Abimelech. Wright mentions that he found carbonized material at this level in the LB temple, and it might be inferred from this that some sort of “violent disturbance” took place. The fact is though, whatever may have happened to the LB temple, the excavators found no violent disturbance of the fortifications of the city during the LB/IA transition. Note that it’s very important to distinguish between the temple and the fortifications of the city. If the temple was destroyed, or pulled down, or burned with fire, it must have happened at the end of the Late Bronze Age or beginning of the Iron age since Iron 1A debris was in the pits after the temple’s presumed destruction. (Shechem, p. 102). And if Wright is correct in locating this period in the time of Abimelech, we should also expect to see¾as Courville argued¾the fortifications of the city demolished during this general time period.

Here are some basic facts regarding the fortifications of the city:

|

STRUCTURE |

FIRST BUILT |

|

Wall A |

MB2c, late “Hyksos” |

|

Wall B |

MB2c, late “Hyksos” |

|

Wall C |

MB2c, early “Hyksos” |

|

C-Embankment |

MB2c, early “Hyksos” |

|

Wall D |

MB2b, pre-“Hyksos” |

|

Wall E |

MB2c, late “Hyksos” |

|

East Gate |

MB2c, late “Hyksos” |

|

Northwest Gate |

MB2c, late “Hyksos” |

Wall D was the earliest wall and served as the western edge of the sacred acropolis (the temenos area). Eventually, the C-Embankment used wall D as an inner retaining wall and wall C as an exterior retaining wall (both walls apparently covered over when the embankment was later extended). Wall A was connected to the North West gate and seems to have circled the whole city. Later, wall B and the East Gate were added within the wall A system to strengthen it, while wall E was also added for extra strength at the end of the MB2c period.

6. STRATA

Stratum 15: This is the last MB2c level, and provides evidence of massive destruction of the city. There is little need to review all this evidence since it is widely accepted, but there are some curious facts that most scholars, including Courville, have not discussed. If the end of the MB2c strata represents the time of Abimelech, then we should expect to find the inhabitants strengthening the fortifications of the city at the end of MB2c period. During their rebellion against Abimelech, the Israelites living in Shechem, were fortifying the city under the leadership of Gaal ben-Ebed. Judges 9:30-31 says,

“When Zebul, the ruler of the city, heard the words of Gaal the son of Ebed, his anger was aroused. And he sent messengers to Abimelech secretly, saying, ‘Take note! Gaal the son of Ebed and his brothers have come to Shechem; and here they are, fortifying the city against you.’”

According to Wright: “Hence the Wall A system belongs to MB II C, but during the course of the same period it was strengthened on the east and north by the Wall B system” (Shechem, p. 69). Furthermore, “The nature of this fortification system and the fact that in both Fields III and I it is above and just 11 m. (36 ft.) inside Wall A, proves that it was built as a means of strengthening the Wall A system from the Northwest Gate around to the East Gate, and on south beyond the limit of excavations. The fact that the bank between the two in Field III was a cemented glacis is a further support to this conclusion….One would think that this intensive effort would indeed have made an impregnable city.” (Ibid., p. 71.)

No doubt the followers of Gaal ben Ebed thought so themselves. Wright further says, “Wall A and Fortress-temple 1a were erected about 1650 B.C. [sic], during the period of the Fifteenth Dynasty, when concentration of power was great. Yet it was also a time when security was the paramount concern, and the people of Shechem, as elsewhere, were willing to exert themselves to unparalleled efforts in fortification for self-defense.” (Ibid, p. 100.)

All to no avail.

In the first part of this essay (surveying the biblical data for what went on at Shechem), it was noted that there were two attacks on Shechem, one that nearly overran the gate of the city, and the second that succeeded in overtaking the city and burning it to the ground. Judges 9:39-41 says,

“So Gaal went out, leading the men of Shechem, and fought with Abimelech. And Abimelech chased him, and he fled from him; and many fell wounded, to the very entrance of the gate. Then Abimelech dwelt at Arumah, and Zebul drove out Gaal and his brothers, so that they would not dwell in Shechem.”

Here we see some possibilities for explaining the destruction that occurred at the East gate prior to the final destruction of the city, and we also see that the driving out of Gaal may have resulted in some internal destruction to the city. Of the signs of destruction at the East gate, Wright says, “It appears evident that the East Gate suffered destruction some time after it was erected, but, still within the MB II C period, it was reconstructed.” (Ibid., p. 73.) According to Wright, new steps were added and the road was repaired:

“The steps show little evidence of wear….[T]hey cannot have been long in use when they were completely covered by fallen brick debris from the towers above. A fierce battle had taken place and the towers were burned and at least partially destroyed. Rebuilding was evidently rapid. The debris of the gate, including the disarticulated fragments of at least six human bodies, was swept into the step area until its level was raised nearly to the threshold level. A new street was created….Then came a second destruction of much greater violence. It filled the south guardroom stairwell with 2 m. of brick debris which spilled out through the door into the gate’s court….Thick masses of brick and carbonized wood from the large timbers which reinforced the brick fell inside the city when Wall B was destroyed along its entire length. As suggested above, apparently an enemy had pulled out enough brick and beams from the inside foundations to make the whole mass fall inward on the city, instead of outward down the slope.” (Ibid., p. 74.)

From what Wright has said, we can see that the East gate suffered some destruction¾though not total¾just before the final destruction of the whole gate and wall system. When Abimelech chased Gaal back to the city, he could go no farther than the gate in his pursuit. The many men who died at the gate were obviously Gaal’s men, and the remains of some of those who died were covered over by the new steps for the gate. The disarticulated bones of human beings mentioned by Wright above indicate that some sort of military engagement at the gate had taken place. Abimelech went away for a while, and Zebul eventually drove the much weakened Gaal from the city.

The second destruction was the burning of the city by Abimelech (as we are arguing). This is evidenced by the fact that the walls were destabilized from the inside, rather than from the outside. Of course, Wright assigns these destructions to the Egyptians and divides the signs of destruction at the East gate by 10 years (Ibid., p. 75), but the first claim merely assumes the correctness of conventional chronology, and the second is just a guess based on the fact that there is little wear on the rebuilt steps of the East gate. Moreover, the archaeological material can only give relative dating, not absolute dating, and 10 years could as easily be 10 days.

The burning of the migdal by Abimelech must have given him the idea of burning the city gates and walls to the ground. This was made easier by how the walls were constructed. Wright says,

“When it was first destroyed, evidently by the Egyptian army [sic]…the Egyptians [sic] were able to set fire to the wall because there was so much wood in it and in battlements upon it, and to pull sufficient brick from its lower part as to cause it to fall inward, instead of outward down the slope. The great quantity of charcoal remains of the wooden beams indicates an exceedingly hot fire. The distance the fallen debris spread within the city from the wall base was at least 14 to 15 m. (46 to 49 ft.) in Field III.” (Ibid., p. 70.)

Wall E was apparently the last fortification to be built before the MB2c destruction: “Dever detected that still another fortification wall, wall E, which overlay the Middle Bronze Age IIC complexes south of the northwest gate, had been built at the very end of the Middle Bronze Age IIC, probably as a desperate defensive effort against attacks accompanying the expulsion of the Hyksos [sic] by the Eighteenth Egyptian Dynasty (c. 1540 BCE) [sic].” (Article on Shechem by E. Campbell, in E. Stern, ed. The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, [1993], Vol. 4, p.

1351.)

Describing the end of MB2c Shechem, Campbell says, “Everywhere, evidence of destruction, probably in two quickly successive phases, covers the uppermost (stratum XV) Middle Bronze phase. Thus ended a two-hundred year period of prominence as a city-state….” (Ibid., pp. 1351-52.)

The final destruction of the city left a long gap in occupation. “The city was so violently ruined, and so many people were killed by the Egyptians [sic], that nearly a century goes by before the city begins to flourish again.” (Shechem, p. 76). Further, “The greatest disturbance shown in the section [of Field 8] is marked by a layer of dark-brown field soil running across the whole section, roughly separating the Middle from the Late Bronze Ages.” (Ibid., p. 48.) Wright concludes that after the MB2c destruction of the city, it was used for raising crops, “[T]his layer of field soil suggests that the tell was used for farming during the period of the gap” (Ibid., p. 48). Thus, the sowing of the city with salt by Abimelech may have stopped the city from growing again for a long time, but it did not stop the farmers from using the tell as a place to grow their crops, salt or no salt.

While no pottery or other indicia were found that could help date the destruction of the MB2c migdal, it was reasonable for Wright and his colleagues to conclude that its destruction took place at the end of MB2c when the rest of the city was destroyed. “This massive structure (Temple 1) was destroyed at a date which cannot be accurately fixed from the evidence available within the temple, but which probably coincided with the general destruction of the city attested at the East Gate and in Fields III and VIII, about 1550 B.C. [sic]. Subsequently, a less substantial structure (Temple 2) was built on the ruins of the former temple. Its foundation date is uncertain, but undoubtedly falls within the LB period, judging from the quantities of LB pottery associated with the building of the podium in its first phase.” (Wright, BASOR, No. 161, p. 32, section by Field Supervisor Robert Bull; cf., Wright, Shechem, p. 95).

Stager’s attempt to bring the destruction of the migdal down to the Iron age must ultimately fail if Wright, et al. are correct about the existence of an LB temple on the ruins of the MB2c city.

Stratum 14: The city was rebuilt in the LB1b period, perhaps by the ancestors of Lab’ayu. The Northwest and East Gates were rebuilt, and a new temple was built over the strata of the MB2c migdal temple. There is no way of knowing at this point how long the city was in ruins before the rebuilding in LB1b, despite Wright’s claim of a hundred years. Such reckoning ultimately would depend on the connection of the archaeological ages to a supposedly correct Egyptian chronology¾a view that New Courville and other alternative chronologies are challenging.

Stratum 13: This represents the Amarna age (LB2a) when Lab’ayu ruled in Shechem with the support of the Habiru (or Hebrews). This strata represents Shechem at its most prosperous, but there are signs that structures within the city were burned at the end of this period, i.e., in Fields 7, 8, 9, and 13. Nevertheless, while buildings inside the city may have been damaged there is no indication by the excavators that the fortifications of the city were destroyed, and no mention is made of any great disturbance at the temple:

“LB phase 2 is the best conceived and best constructed of the LB phases. Such comparative wealth and civic energy most probably belong to the period when Lab’ayu of Shechem controlled a small empire extending from just north of Jerusalem to the region of Megiddo. The phase ended in a destruction by fire at least of the eastern building; preliminary correlations with Fields VII, VIII and IX indicate that the destruction was general throughout the city. In Field XIII the disaster brought down upper stories and roofs and crushed debris on the lower floors.” (Campbell, Ross, Toombs, “Eighth Campaign,” etc., BASOR, no. 204, p. 14.)