Lachish

Aerial View of Lachish

Aerial View of LachishUssishkin et. al. (2014)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Lachish | Hebrew | לכיש |

| Tel Lachish | Hebrew | תל לכיש |

| Lakis, Lakisa, Lakisi | el-Amarna Letters | |

| Lakisu | Assyrian Akkadian | |

| Lachis | Greek | Λαχίς |

| Lachis | Latin | |

| Tell ed-Duweir | Arabic | تل الدوير |

Lachish was an ancient Canaanite and Israelite city in the Shephelah ("lowlands of Judea") region of Israel, on the south bank of the Lakhish River, mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. The current tell (ruin) by that name, known as Tel Lachish or Tell ed-Duweir, has been identified with the biblical Lachish. The earliest occupation comes from the Neolithic ( Wikipedia).

- from Ussishkin (1978)

During the first half of the first millennium B.C., at the period of the Kingdom of Judah, Lachish was again a fortified city, and in fact it was the most important Judean city after Jerusalem. It played a special role in 701 B.C., when Sennacherib king of Assyria invaded Judah, and conquered all the fortified cities except Jerusalem. His royal camp — as we learn from the Old Testament — was situated near Lachish, which he stormed and conquered. A unique set of stone-reliefs portraying in detail the conquest of Lachish was placed by Sennacherib in a special centrally situated room in his royal palace at Nineveh. These reliefs are now exhibited in the British Museum in London. The detailed reliefs and their position in the royal palace show that the conquest of Lachish was of singular importance. This was, perhaps, the most important military achievement of Sennacherib — undoubtedly the most powerful ruler of this part of the world — during the earlier part of his reign. In 588/6 B.C., Lachish was stormed and burnt again, this time by Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon, who conquered Jerusalem and destroyed the temple. After that, when the country was under Persian domination in the fifth-fourth centuries B.C., Lachish served as a district capital, and then finally was deserted.

- from Ussishkin (1978)

The excavations came to an end in 1938, shortly after Starkey was brutally murdered by Arab marauders while on his way from Lachish to the opening ceremony of the Palestine Archaeological Museum in Jerusalem. After Starkey's death, his assistant Olga Tufnell worked for twenty years on the data and finds of the excavations, and produced a meticulous excavation report.

The mound remained untouched till the present excavations, except for a small dig carried out by Professor Yohanan Aharoni of Tel Aviv University in the eastern part of the mound to investigate some of his theories concerning the Judean shrine at Arad.

- from Ussishkin (1978)

The excavations are planned on a long-term basis, and aim at systematically studying the history of Lachish and its material remains. So far, five excavation seasons have been carried out in 1973-1977, and the next one will take place in the summer of 1978. In the future, we plan to start an archaeological survey in the region of Lachish and to build an expedition camp nearby. Also, we hope to turn the mound into a national park, this way preserving the ancient remains and opening them to the public.

When selecting our excavation areas on the huge mound, we had to take three factors into account: firstly, the difficulties of digging a large mound on a relatively small scale; secondly, the need to continue the work in the old excavation areas and follow the results of the previous excavations; and thirdly, the special importance of this Judean city. After many deliberations we decided to work in three areas (Fig. 3): the Judean palace-fort and the Canaanite buildings underneath (under the supervision of Mrs. Christa Clamer); the area of the Judean city gate (under the supervision of Mr. Y. Eshel); and a section area at the western part of the mound (under the supervision of Mr. G. Barkay). The areas of the palace-fort and the city gate were partly dug by Starkey and here we are continuing his work. The section area is a relatively narrow trench which cuts through the edge of the mound and will eventually extend to the lower slope. Here we plan to penetrate the lower levels of the mound, and get a sectional view of the various levels down to the natural rock, following the pattern set by Dame Kathleen Kenyon in her excavations at Jericho.

- Aerial View of Tel Lachish

from the east from BibleWalks.com

- Fig. 12.31 - Aerial View of

the Palace-Fort and the Southern Annex during excavations from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.31

Fig. 12.31

The Palace-Fort, the large courtyard on the eastern side and the Southern Annex during excavation; view from the south.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 1 - Aerial View of

Tel Lachish in 1934 from Vaknin et al. (2024)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Aerial view of Tel Lachish from the north, photographed on July 18, 1934 (Ussishkin 2004b: 24 Fig. 2.3); note the excavated area along the Outer Revetment Wall on the northern and western slopes of the mound

Vaknin et al. (2024) - Lachish in Google Earth

- Lachish on govmap.gov.il

- Map of the mound and

excavation areas from Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

Lachish: map of the mound and excavation areas

Lachish: map of the mound and excavation areas

Stern et al (1993 v. 3) - Fig. 2 - Plan of the

mound from Vaknin et al. (2024)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The plan of Tel Lachish according to the TAU expedition (based on Ussishkin 2004b: 34, Fig. 2.9), showing the location of the mudbrick wall of the tower-buttress sampled for this study (LC08);

- outer gate

- Level IV–III inner gate

- the Outer Revetment Wall marked all around the mound, excluding the gate area and a gap in the northeastern corner of the mound

- the main city wall

- the siege ramp

Vaknin et al. (2024) - Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 2 - Plan of the mound

from Ussishkin (2024)

Fig. 2

Map of Tel Lachish:

- the outer gate

- the inner gate

- the outer revetment

- the main city wall

- the Palace-Fort

- Area S

- the Great Shaft

- the well

- the Assyrian siege ramp

- the counter ramp

- the Solar Shrine

- the Fosse Temple

- The Acropolis Temple

(reproduced from Ussishkin 2004: Vol. 1, Fig. 2.9).

Ussishkin (2024)

- Map of the mound and

excavation areas from Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

Lachish: map of the mound and excavation areas

Lachish: map of the mound and excavation areas

Stern et al (1993 v. 3) - Fig. 2 - Plan of the

mound from Vaknin et al. (2024)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

The plan of Tel Lachish according to the TAU expedition (based on Ussishkin 2004b: 34, Fig. 2.9), showing the location of the mudbrick wall of the tower-buttress sampled for this study (LC08);

- outer gate

- Level IV–III inner gate

- the Outer Revetment Wall marked all around the mound, excluding the gate area and a gap in the northeastern corner of the mound

- the main city wall

- the siege ramp

Vaknin et al. (2024) - Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 2 - Plan of the mound

from Ussishkin (2024)

Fig. 2

Map of Tel Lachish:

- the outer gate

- the inner gate

- the outer revetment

- the main city wall

- the Palace-Fort

- Area S

- the Great Shaft

- the well

- the Assyrian siege ramp

- the counter ramp

- the Solar Shrine

- the Fosse Temple

- The Acropolis Temple

(reproduced from Ussishkin 2004: Vol. 1, Fig. 2.9).

Ussishkin (2024)

- Artist's rendition of Lachish

in the 8th century BCE from biblewalks.com

Artist's rendition of Lachish in the 8th century BCE

Artist's rendition of Lachish in the 8th century BCE

Drawing by BibleWalks

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Fig. 6 - Artist's rendition

of Lachish Level III on the eve of the Assyrian siege from Vaknin et al. (2024)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Suggested reconstruction of Lachish Level III according to the TAU expedition (Ussishkin 2004c: 85, Fig. 3.1; drawing by Judith Dekel); note the Outer Revetment Wall encircling the mound at mid-slope

Vaknin et al. (2024)

- Artist's rendition of Lachish

in the 8th century BCE from biblewalks.com

Artist's rendition of Lachish in the 8th century BCE

Artist's rendition of Lachish in the 8th century BCE

Drawing by BibleWalks

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Fig. 6 - Artist's rendition

of Lachish Level III on the eve of the Assyrian siege from Vaknin et al. (2024)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Suggested reconstruction of Lachish Level III according to the TAU expedition (Ussishkin 2004c: 85, Fig. 3.1; drawing by Judith Dekel); note the Outer Revetment Wall encircling the mound at mid-slope

Vaknin et al. (2024)

- Fig. 11.2 - The Fortified City

of Level IV from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 11.2

Fig. 11.2

The fortified city of Level IV:

- outer gate

- inner gate

- outer revetment wall

- main city wall

- Palace B

- Enclosure Wall and houses at its edge

- Great Shaft

- well

- concentration of cult vessels in the area of the Solar Shrine

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 1 - The Fortified City

of Levels III-IV from Ussishkin (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Tel Lachish, Levels IV–III

- The Bastion

- Inner gate

- Outer revetment

- Main city wall

- Palace-Fort

- Area S – the main section of Tel Aviv University renewed excavations

- Great Shaft

- Well

- Assyrian siege ramp

- Counter-ramp

- Solar Shrine

- Fosse Temples

- Acropolis Temple.

Ussishkin (2023)

- Fig. 11.2 - The Fortified City

of Level IV from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 11.2

Fig. 11.2

The fortified city of Level IV:

- outer gate

- inner gate

- outer revetment wall

- main city wall

- Palace B

- Enclosure Wall and houses at its edge

- Great Shaft

- well

- concentration of cult vessels in the area of the Solar Shrine

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 1 - The Fortified City

of Levels III-IV from Ussishkin (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Tel Lachish, Levels IV–III

- The Bastion

- Inner gate

- Outer revetment

- Main city wall

- Palace-Fort

- Area S – the main section of Tel Aviv University renewed excavations

- Great Shaft

- Well

- Assyrian siege ramp

- Counter-ramp

- Solar Shrine

- Fosse Temples

- Acropolis Temple.

Ussishkin (2023)

- Fig. 12.20 - Plan of Palace

B of Level IV from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.20

Fig. 12.20

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace B.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.29 - Plan of Palace

C of Level IV from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.29

Fig. 12.29

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace C.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.31 - Aerial View

of the Palace-Fort and the Southern Annex during excavations from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.31

Fig. 12.31

The Palace-Fort, the large courtyard on the eastern side and the Southern Annex during excavation; view from the south.

Ussishkin (2014)

- Fig. 12.20 - Plan of Palace

B of Level IV from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.20

Fig. 12.20

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace B.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.29 - Plan of Palace

C of Level IV from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.29

Fig. 12.29

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace C.

Ussishkin (2014)

- Fig. 12.4a - Plan of the

Level III city gate from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4a

Fig. 12.4a

Plan of the Level III city gate.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4c - Reconstruction

of the Level III city gate from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4c

Fig. 12.4c

The Level III city gate, proposal for reconstruction.

Ussishkin (2014)

- Fig. 12.4a - Plan of the

Level III city gate from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4a

Fig. 12.4a

Plan of the Level III city gate.

Ussishkin (2014)

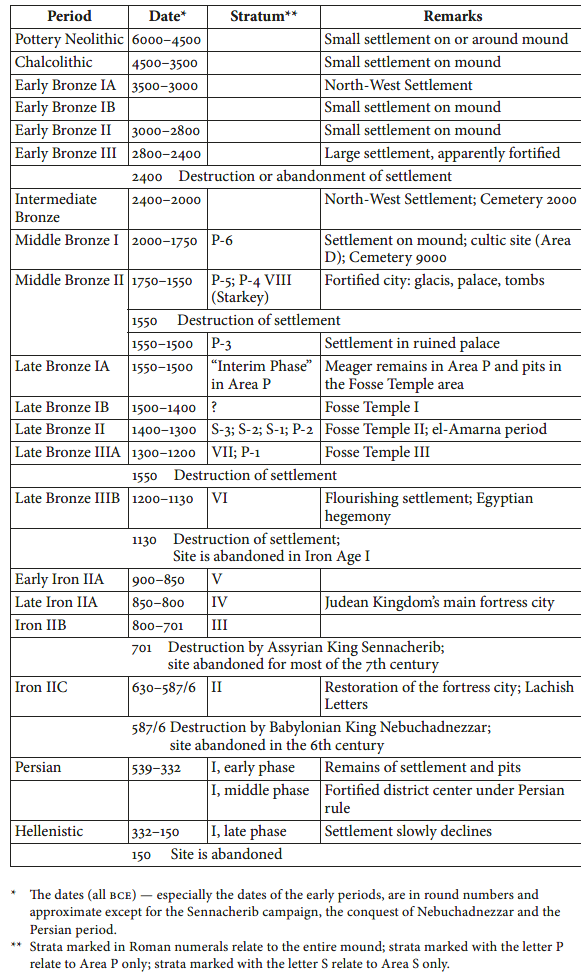

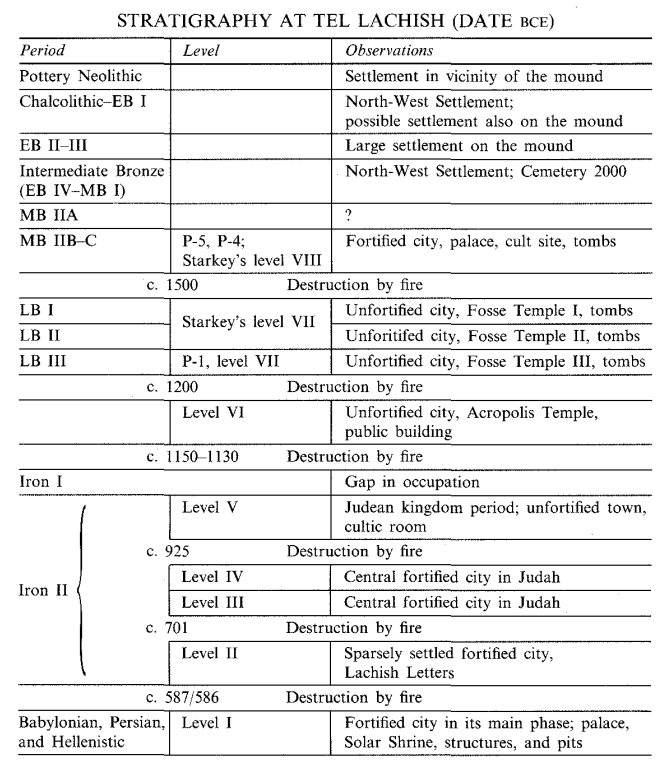

In order to ensure continuity between the various excavations at the site and to keep the stratigraphic terminology standardized, the Institute's excavations adopted the divisions determined by Starkey for levels VI-I. Because it is impossible to include all the Middle and Late Bronze Age phases excavated in the new excavations within the framework ofStarkey's levels VIII and VII, these layers will be renumbered when the excavation of the section in areaS is complete. The level excavated in the section beneath level VI has so far been labeled VII, while those layers excavated in area P, below level VI, have been temporarily termed P-1-P-5.

Table 1.1

Table 1.1Stratigraphy at Lachish

Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

- Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

(magnified) from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 11.2 - The Fortified City of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 11.2

Fig. 11.2

The fortified city of Level IV:

- outer gate

- inner gate

- outer revetment wall

- main city wall

- Palace B

- Enclosure Wall and houses at its edge

- Great Shaft

- well

- concentration of cult vessels in the area of the Solar Shrine

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 1 - The Fortified City of Levels III-IV

from Ussishkin (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Tel Lachish, Levels IV–III

- The Bastion

- Inner gate

- Outer revetment

- Main city wall

- Palace-Fort

- Area S – the main section of Tel Aviv University renewed excavations

- Great Shaft

- Well

- Assyrian siege ramp

- Counter-ramp

- Solar Shrine

- Fosse Temples

- Acropolis Temple.

Ussishkin (2023) - Fig. 12.20 - Plan of Palace B of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.20

Fig. 12.20

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace B.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.29 - Plan of Palace C of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.29

Fig. 12.29

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace C.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.31 - Aerial View of the Palace-Fort

and the Southern Annex during excavations from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.31

Fig. 12.31

The Palace-Fort, the large courtyard on the eastern side and the Southern Annex during excavation; view from the south.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4a - Plan of the Level III city gate

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4a

Fig. 12.4a

Plan of the Level III city gate.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4c - Reconstruction of the Level III city gate

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4c

Fig. 12.4c

The Level III city gate, proposal for reconstruction.

Ussishkin (2014)

- Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

(magnified) from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 11.2 - The Fortified City of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 11.2

Fig. 11.2

The fortified city of Level IV:

- outer gate

- inner gate

- outer revetment wall

- main city wall

- Palace B

- Enclosure Wall and houses at its edge

- Great Shaft

- well

- concentration of cult vessels in the area of the Solar Shrine

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 1 - The Fortified City of Levels III-IV

from Ussishkin (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Tel Lachish, Levels IV–III

- The Bastion

- Inner gate

- Outer revetment

- Main city wall

- Palace-Fort

- Area S – the main section of Tel Aviv University renewed excavations

- Great Shaft

- Well

- Assyrian siege ramp

- Counter-ramp

- Solar Shrine

- Fosse Temples

- Acropolis Temple.

Ussishkin (2023) - Fig. 12.20 - Plan of Palace B of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.20

Fig. 12.20

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace B.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.29 - Plan of Palace C of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.29

Fig. 12.29

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace C.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.31 - Aerial View of the Palace-Fort

and the Southern Annex during excavations from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.31

Fig. 12.31

The Palace-Fort, the large courtyard on the eastern side and the Southern Annex during excavation; view from the south.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4a - Plan of the Level III city gate

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4a

Fig. 12.4a

Plan of the Level III city gate.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4c - Reconstruction of the Level III city gate

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4c

Fig. 12.4c

The Level III city gate, proposal for reconstruction.

Ussishkin (2014)

Ussishkin (2014:203-204) noted that

little is known about Lachish Level Vand

no findings were unearthed in the excavation that can dateit. He estimated a date of

the latter part of the tenth century or the fist part of the ninth century BCE [the early stage of Iron Age IIA, according to a division proposed by Ze’ev Herzog and Lily Singer-Avitz]based on

general considerations and the chronology of parallel sites in the southern Land of Israel.

- Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

(magnified) from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 11.2 - The Fortified City of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 11.2

Fig. 11.2

The fortified city of Level IV:

- outer gate

- inner gate

- outer revetment wall

- main city wall

- Palace B

- Enclosure Wall and houses at its edge

- Great Shaft

- well

- concentration of cult vessels in the area of the Solar Shrine

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 1 - The Fortified City of Levels III-IV

from Ussishkin (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Tel Lachish, Levels IV–III

- The Bastion

- Inner gate

- Outer revetment

- Main city wall

- Palace-Fort

- Area S – the main section of Tel Aviv University renewed excavations

- Great Shaft

- Well

- Assyrian siege ramp

- Counter-ramp

- Solar Shrine

- Fosse Temples

- Acropolis Temple.

Ussishkin (2023) - Fig. 12.20 - Plan of Palace B of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.20

Fig. 12.20

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace B.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.29 - Plan of Palace C of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.29

Fig. 12.29

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace C.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.31 - Aerial View of the Palace-Fort

and the Southern Annex during excavations from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.31

Fig. 12.31

The Palace-Fort, the large courtyard on the eastern side and the Southern Annex during excavation; view from the south.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4a - Plan of the Level III city gate

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4a

Fig. 12.4a

Plan of the Level III city gate.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4c - Reconstruction of the Level III city gate

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4c

Fig. 12.4c

The Level III city gate, proposal for reconstruction.

Ussishkin (2014)

Ussishkin (2014:207-208) noted that

We have no archaeological data to determine the date of the founding of Level IV at the end of the tenth century or the beginning of the ninth century BCE. We should raise the possibility here that the fortified city was established by King Asa (908–867 BCE) or King Jehoshaphat (870–846 BCE), each of whom ruled for prolonged periods. We will also mention that 2 Chronicles (14:5–6; 17:12) says they both built fortified cities in Judah. The problematic piece of biblical information that must be mentioned here is the description of the fortifications of Rehoboam (928–911 BCE) presented in detail in 2 Chronicles 11:5–12,23:Ussishkin (2014:214-215) wrote the following about the end of Level IV:And Rehoboam dwelt in Jerusalem, and built cities for defence in Judah. He built even Beth-lehem, and Etam, and Tekoa, and Beth-zur, and Soco, and Adullam and Gath, and Mareshah, and Ziph and Adoraim, and Lachish, and Azekah, and Zorah, and Aijalon, and Hebron, which are in Judah and in Benjamin, fortified cities. And he fortified the strongholds, and put captains in them, and store of victual, and oil and wine. And in every city he put shields and spears, and made them exceeding strong… And he dealt wisely, and dispersed of all his sons throughout all the lands of Judah and Benjamin, unto every fortified city; and he gave them victual in abundance. And he sought for them many wives.Based on the above text, some scholars — among them Aharoni, Yadin and William Dever — have proposed that the fortified city of Level IV was built by Rehoboam. Others disagree over the dating of the list of that king’s fortification work: Nadav Na’aman attributed it to the era of Hezekiah’s kingdom, Volkmar Fritz to the period of Josiah, while Israel Finkelstein dated it to the Hellenistic period. Indeed, based on the above verses, it is difficult to attribute the construction of Lachish Level IV to Rehoboam. Even if we assume that this is a reliable historical source, Lachish is depicted there in the same breath as a series of other cities fortified by Rehoboam. However, those are all cities of secondary importance while the fortifications of Lachish Level IV show that it was a particularly important city compared to other cities in Judah.

The End of the Fortified City of Level IV

It is not at all clear why the fortified city of Lachish Level IV came to an end and Level III was built. The data is as follows: Between Level IV and Level III, the following changes took place:

- the superstructure — but not the foundations — of the Level IV Palace-Fort (Palace B) was destroyed; in Level III the foundations of the Palace-Fort were expanded and a new palace (Palace C) was built on those expanded foundations.

- The Northern Annex of Level IV continued to serve unchanged in the Palace-Fort of Level III, but the Southern Annex of Level IV was now replaced by a similar building, twice the size, and a large courtyard was built in front of the palace.

- The Enclosure Wall of Level IV was partly replaced by the new Enclosure Wall built in Level III along the same lines.

- The city walls seem to have continued in use unchanged.

- The Level IV city gate also continued in use in Level III but underwent significant changes: A massive tower was added in the corner of the outer gatehouse and the superstructure of the inner gatehouse was apparently rebuilt on the foundations of the previous gatehouse. The floors of the gate’s courtyard and the inner gatehouse were raised.

- The Level IV dwelling uncovered in Area S was demolished and in Level III, a house with a similar plan was built, with additional domestic dwellings nearby.

And so it was that most of the Level IV structures — except for the city walls — were replaced by new structures that resembled their predecessors. Numerous clay vessels were found in the Level IV domestic dwelling excavated in Area S, but no evidence of intentional destruction was discerned. No such evidence or signs of fire were found in any of the other areas, either.

These data show clearly that on the one hand, there was continuity between Level IV and Level III but on the other, a break ensued between the two levels following some event that caused the destruction of most of the buildings and their replacement with new ones. The assemblage of vessels found in the Level IV domestic dwelling also alludes to sudden destruction, but there too, nothing was found that would indicate that this destruction had been intentional or that an enemy had set fire to it. All of this data conforms to the proposal raised by Moshe Kochavi in 1976, when he visited the excavation — that Level IV was destroyed by a powerful earthquake that necessitated the rebuilding of most of the structures. As will be recalled, during the reign of King Uzziah, in 760 BCE, and perhaps a few years before, a major earthquake took place, which is mentioned in the book of Amos (1:1):The words of Amos, who was among the herdmen of Tekoa, which he saw concerning Israel in the days of Uzziah king of Judah, and in the days of Jeroboam the son of Joash king of Israel, two years before the earthquake.Ze’ev Herzog and Lily Singer-Avitz proposed that this event be viewed as the end of the later stage of the Iron Age IIA at other sites as well. However, there is a great deal to be said for the proposal that Stratum A3 at Gath, which is characterized by a similar pottery assemblage, was destroyed as early as the end of the ninth century. The latter proposal seems to contradict the suggestion that Level IV in nearby Lachish reached its end several decades later. Lacking direct written evidence from the sites themselves, it is difficult to decide among the various possibilities.

- Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 5.2 - Excavation Grids

(magnified) from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

- The general grid, on a northern axis

- The British grid, deviating by a few degrees from the north

- The four “local” grids in the excavation areas

- S - the main trench at the edge of the mound

- GE, GW - the gate

- R - the Assyrian assault point

- P, Pal, D - the Palace-Fort

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 11.2 - The Fortified City of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 11.2

Fig. 11.2

The fortified city of Level IV:

- outer gate

- inner gate

- outer revetment wall

- main city wall

- Palace B

- Enclosure Wall and houses at its edge

- Great Shaft

- well

- concentration of cult vessels in the area of the Solar Shrine

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 1 - The Fortified City of Levels III-IV

from Ussishkin (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Tel Lachish, Levels IV–III

- The Bastion

- Inner gate

- Outer revetment

- Main city wall

- Palace-Fort

- Area S – the main section of Tel Aviv University renewed excavations

- Great Shaft

- Well

- Assyrian siege ramp

- Counter-ramp

- Solar Shrine

- Fosse Temples

- Acropolis Temple.

Ussishkin (2023) - Fig. 12.20 - Plan of Palace B of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.20

Fig. 12.20

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace B.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.29 - Plan of Palace C of Level IV

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.29

Fig. 12.29

The Palace-Fort, schematic plan of Palace C.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.31 - Aerial View of the Palace-Fort

and the Southern Annex during excavations from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.31

Fig. 12.31

The Palace-Fort, the large courtyard on the eastern side and the Southern Annex during excavation; view from the south.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4a - Plan of the Level III city gate

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4a

Fig. 12.4a

Plan of the Level III city gate.

Ussishkin (2014) - Fig. 12.4c - Reconstruction of the Level III city gate

from Ussishkin (2014)

Fig. 12.4c

Fig. 12.4c

The Level III city gate, proposal for reconstruction.

Ussishkin (2014)

Ussishkin (1977:52) dated the destruction layer in Level III to the siege, conquest, and destruction of Lachish by Sennacherib of Assyria in 701 BCE.

Ussishkin (1977:52) noted the following:

Level IV apparently came to a sudden end, but it seems clear that this was not caused by fire. On the other hand, the lower house of Level III and the rebuilt enclosure wall followed the lines of the Level IV structures, while the Level IV city wall and gate continued to function in Level III; these facts point towards the continuation of life without a break. Considering that the fortifications remained intact, we can hardly identify this level with the city which was stormed and completely destroyed in the fierce Assyrian attack. Here we may mention M. Kochavi's suggestion (made during a visit to the excavation in 1976 and quoted here with his kind permission) that the end of the Level IV structures may have been caused by an earthquake. A natural catastrophe of this sort would, perhaps, be compatible with the above findings. Of interest in this connection is the earthquake mentioned in Amos 1:1 and Zech. 14:5, which occurred around 760 B.C.E. during the reign of Uzziah, king of Judah.Ussishkin (1977:43) noted that:

Many of the floors of the main building were covered with relatively large quantities of pottery, including both intact and broken vessels - an indication of sudden destruction. On the other hand, there is only a very small amount of ash remains, lying either on the floors or above them. The layer of debris accumulated above the floors and separating them from the Level III floors was relatively thin, usually less than 50 cm.; in some cases pottery vessels lying on the earlier floors could be discerned while still cleaning the later floors.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 26 June 2025

- from Ussishkin (2024)

Among these, only one is explicitly proposed to have a possible seismic cause. Ussishkin states that the transition from Level IV to Level III, during the Iron IIA to Iron IIB period (9th–early 8th century BCE), was "possibly caused by an earthquake." This hypothetical earthquake would have preceded the well-attested Assyrian destruction of Level III in 701 BCE.

No structural collapse patterns or damage diagnostics are described in detail to support the earthquake hypothesis, but the abrupt rebuilding phase and architectural changes provide circumstantial support for seismic activity. Elsewhere in the article, earthquakes are not cited as causes for the better-documented earlier or later destruction layers, which are all attributed to military action or deliberate burning.

This makes the proposed Iron Age earthquake prior to the 701 BCE siege the only archaeoseismic event mentioned, though it is treated cautiously as a possible cause rather than a confirmed one.

- Figure 3 - Time-stratigraphic correlation chart

of Iron IIb excavations throughout an extensive region of Israel and Jordan from Austin et. al. (2000)

FIG. 3

FIG. 3

Time-stratigraphic correlation chart of Iron IIb excavations throughout an extensive region of Israel and Jordan. Datum for correlation is earthquake debris or rebuilding horizons assigned to a single, 750 B.C. seismic event. Locations of cities are shown in Figure 1. Strata names at each site are from primary archaeological reports.

Symbols

- P = pottery date

- C-14 = radiocarbon date

- T = dated text material

- D = military destruction layer with historical date assigned

- A = historically dated architectural style

- E = earthquake destruction layer

- E ? = probable earthquake destruction layer (significant rebuilding horizon without evidence of military conquest)

Austin et. al. (2000)

18. Lachish

Lachish, first identified with Tell el-Hesi (Condor) but later connected by W. F. Albright with Tell ed-Duweir sat upon a route between the Coastal Plain and the Hebron Hills attesting to its many layers of occupation. Level V, dating to the Iron IIA and likely destroyed at the hands of Shishak around 925 BCE gave way to a large fortified city though the exact beginning of this building period (Level IV) is unclear, Ussishkin argues that it should be linked to an early Judean king (Rehoboam, Asa, or Jeohoshapat).112 Level IV consists of an outer reventment wall with a glacis, imposing gate and palace-fort and according to the excavators, except for the house in Area S (the area extends between the city wall and the palace-fort) and the city walls, all the monumental structures were destroyed at the end of Level IV, though it is unclear when the destruction dates. This uncertainty is reflected in how Lachish IV became associated with earthquake damage, quoting Ussishkin:

Level IV apparently came to a sudden end, but it seems clear that this was not caused by fire. On the other hand, the lower house of Level III and the rebuilt enclosure wall followed the lines of the Level IV structures, while the Level IV city wall and gate continued to function in Level III; these facts point towards the continuation of life without a break. Considering that the fortifications remained intact, we can hardly identify this level with the city which was stormed and completely destroyed in the fierce Assyrian attack. Here we may mention M. Kochavi's suggestion (made during a visit to the excavation in 1976 and quoted here with his kind permission) that the end of the Level IV structures may have been caused by an earthquake. A natural catastrophe of this sort would, perhaps, be compatible with the above findings. Of interest in this connection is the earthquake mentioned in Amos 1: 1 and Zech. 14:5, which occurred around 760 B.C.E. during the reign of Uzziah, king of Judah.113Thus, Moshe Kochavi, who had begun digging at Hazor with Yadin in 1955, and was no doubt influenced by the earthquake damage he saw at Hazor, provided the suggestion to Usshiskin, a suggestion that was based more on a process of elimination (not caused by fire, outer walls still standing so no military incursion), than by diagnostics associated with earthquake damage. To Usshiskin’s credit he has remained neutral regarding the ambiguous evidence both in the preliminary reports as well as his article twenty years later in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land.114 The conclusion reached by William Dever in 1992, however, would argue that Hazor and Lachish were two of the few sites that have put forward “concrete” evidence of earthquake damage and in his view the evidence at Lachish is “perhaps the strongest.”115 Dever does not elaborate on what he sees as evidence of seismic damage. Since that time the final reports from the 1973-1994 excavations at Lachish have been published but there is nothing to change the state of Ussishkin’s conclusions. He writes:

Pottery was found upon the floors of the Level IVa buildings, but there was no evidence for destruction by fire. It is quite possible that this phase was destroyed by an earthquake rather than intentionally destroyed by human attackers, though no unequivocal proof of this is available. Further support, however, may be seen in the fact that the builders of Level III attempted to restore the destroyed city, behaviour which might be considered as an indication that the builders of Level III were no new, intrusive population.116While the evidence remains up for debate the evidence in the archaeological and historical record, as well as the excavators’s comments on the destruction, may point to internal reasons for the destruction. 2 Kings 14 recounts the flight of Amaziah, son of Joash from Jerusalem to Lachish (14:19 and 2 Chron 25:27) where he was captured and subsequently killed. The text lists the conspirators in the plural

[וַיִּשְׁלְח֤וּ אַחֲרָיו֙ לָכִ֔ישָׁה וַיְמִתֻ֖הוּ שָֽׁם׃]Amaziah’s life, as depicted by the Deuteronomist, was filled with challenge and misfortune that is characterized by frequent confrontation and political scheming.117 To my knowledge, little attention has been given to exploring the implications of Amaziah fleeing to Lachish.118 When Amaziah fled he would have taken a close cohort of trusted advisors and bodyguards with him to Lachish where he appears to have barricaded himself in the city. The conspirators were likely organized by Azariah, as Anson Rainey notes, “it (the conspiracy) could hardly have been done without the knowledge and even the consent of Azariah [aka King Uzziah].”119 Further, the local population who were against the high places that Amaziah kept also aided in his overthrow. In sum, when Amaziah fled the capital city for Lachish he was not met by trusted loyalists in his kingdom but by conspirators from Azariah as well as locals against his rule.

“But they sent after him to Lachish and they killed him there.”

With this historical reconstruction in mind, we can return to the archaeology of Lachish and suggest an alternate interpretation that factors in the apparent destruction, but lack of military incursion, and quick rebuilding between levels IV and III. One interpretation of the evidence could be a smaller attack focused on dislodging Amaziah from Lachish and ending his reign that would not result in evidence of a large scale military incursion. Following his disposal, as the monumental buildings were destroyed but not the fortifications, it appears to be a conscious choice by the attackers who were focused on removing monarchial influence while retaining administrative strength. At the same time, as Usshishkin explains, “by the time of Level III the entire area between the palace-fort and the brick city wall south of the enclosure wall had become densely populated, being occupied by relatively poor houses.”120 In this way, the monarchial air that Amaziah filled was soon burst by the reversal of fortunes as housing was now placed where he formally held his last stand. This would account for the rather quick restoration that Barkai and Ussishkin asserted “were no new, intrusive population.”

One other piece of evidence strengthens this explanation. Amihai Mazar and Nava Panitz-Cohen suggest the transition between Lachish IV and III is earlier than normally thought, based on their excavations at Timnah.121 The large assemblage of pottery from Timnah Stratum III includes a number of pottery types that are found at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, which dates to c. 800 BCE.122 Also, a number of Stratum III types are found at Tel ‘Eton, dated to 850-750 BCE. At the same time, large numbers of LMLK jars found in Stratum III led Mazar and Panitz-Cohen to identify a main Stratum III as well as a later Stratum IIIB. This distinction is important as Orna Zimhoni argued that Tel Batash Stratum III is a transitional phase between Lachish Levels IV and III.123 However, based on the typology above, it makes better sense to fit the transition from Tel Batash Stratum IV-III to around the time of transition in rule from Amaziah to Uzziah. This would coincide with the transition from Lachish IV to III. Hence, if there is an ideological reason for destroying government buildings because they represent the king, this event may stand behind the pottery changes at Lachish between Levels IV and III. In short, a massive overhaul in the material culture could be due to the political struggle. Also, modern ethnographic studies have demonstrated that residents often attack authority centers following a coup d’état.124 This scenario, then, provides an alternate perspective on a reevaluation of the historical and archaeological evidence at Lachish that takes into account destruction without fire or clear military incursion as well as the quick rebuilding that attempted to restore the damaged city.

112 David Ussishkin, “Lachish,” NEAHL 3: 897-911.

113 David Ussishkin, “The Destruction of Lachish by Sennecherib and the Dating of the Royal Judean Storage Jars,”

TA 4 (1977): 28-60. See also Ussishkin’s statement concerning Area S, Level IV (43), “Many of the floors of the

main building were covered with relatively large quantities of pottery, including both intact and broken vessels - an

indication of sudden destruction. On the other hand, there is only a very small amount of ash remains, lying either on

the floors or above them. The layer of debris accumulated above the floors and separating them from the Level III

floors was relatively thin, usually less than 50 cm.; in some cases pottery vessels lying on the earlier floors could be

discerned while still cleaning the later floors.”

114 In Ussishkin, “The Destruction of Lachish,” 51, he wrote, “The transition from Level IV to Level III is

characterized by both continuation and some clear-cut changes and rebuildings.” In his encyclopedia article, he

simply notes that, “M. Kochavi has suggested that the destruction was caused by an earthquake.”

115 Dever, “The Earthquake,” 28*, 35*.

116 Gabriel Barkey and David Ussishkin, “Area S: The Iron Age Strata,” in The Renewed Archaeological

Excavations at Lachish (1973-1994) (5 vols.; Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 2004), 2:447.

117 J. Maxwell Miller and John H. Hayes, A History of Ancient Israel and Judah (2d ed.; Louisville: John Knox,

2006), 352, simply mention that Amaziah was apparently, “involved in some political scheme, fled to Lachish, and

there was put to death.”

118 M. Haran, “Observations on the Historical Background of Amos 1:2-2:6,” IEJ 18 (1968): 201-12, focuses on the

effects of Amaziah’s victory over the Edomites and the dating of sections in Amos that mention Edom. Anson

Rainey, “The Biblical Shephelah of Judah,” BASOR 251 (1983): 1-22, “If Amaziah had hoped to gain the support of

a local governor at Lachish (perhaps a member of the royal family), he was sadly mistaken.”

119 Rainey, “The Biblical Shephelah,” 14, 16.

120 Ussishkin, “The Destruction of Lachish,” 44.

121 I would like to thank Kyle Keimer for strengthening my argument about the transition between Lachish IV and

III by pointing me to the evidence at Timnah.

122 Amihai Mazar and Nava Panitz-Cohen, “” in Timnah (Tel Batash) II: the Finds from the First Millennium BCE

(2 vols.; Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 2001), 156–160.

123 Orna Zimhoni, Studies in the Iron Age Pottery of Israel: Typological, Archaeological and Chronological Aspects

(OP 2; Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 1997), 141–156.

124 See, for example, the numerous accounts of governmental overthrow and the destruction of government buildings

in Jonathan Kandall, “Iraq’s Unruly Century,” Smithsonian Magazine 34 (May 2003): 44–52.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broken Pottery (found in fallen position ?) | Area S (domestic dwellings)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

Ussishkin (2014) |

|

|

|

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Discussion | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broken Pottery (found in fallen position ?) | Area S (domestic dwellings)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2The renewed excavation areas and the various grids:

Ussishkin (2014) |

|

VII+ | |

|

|

|

VIII+ |

Austin, S. A., et al. (2000). "Amos's Earthquake: An Extraordinary Middle East Seismic Event of 750 B.C."

International Geology Review 42(7): 657-671.

Ben-Menahem, A. (1991). "Four Thousand Years of Seismicity along the Dead Sea rift."

Journal of Geophysical Research 96((no. B12), 20): 195-120, 216.

Danzig, D. (2011). A Contextual Investigation of Archaeological and Textual

Evidence for a Purported mid-8thCentury BCE Levantine Earthquake Book of Amos, Dr. Shalom Holtz.

Dever (1992). A Case-Study in Biblical Archaeology: The Earthquake of ca. 760 B.C.E: PERA.

Finkelstein, I. and Piasetzky, E. 2010. The Iron I/IIA Transition in the Levant: A Reply

to Mazar and Bronk Ramsey and a New Perspective. Radiocarbon 52: 1667-1680.

Marco, S. (2008). "Recognition of earthquake-related damage in archaeological sites:

Examples from the Dead Sea fault zone." Tectonophysics 453(1-4): 148-156.

Mazar, A. and Bronk Ramsey, C. 2008. 14C Dates and the Iron Age Chronology of Israel: A Response.

Radiocarbon 50: 159-180.

Rainey, A. F. (1983). "The Biblical Shephelah of Judah."

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research(251): 1-22.

Roberts, R. N. (2012). Terra Terror: An Interdisciplinary Study of Earthquakes in

Ancient Near Eastern Texts and the Hebrew Bible. Near Eastern Languages and Cultures.

Los Angeles, University of California - Los Angeles Doctor of Philosophy.

Ussishkin, D., 1977, The destruction of Lachish by Sennacherib and the dating of the

royal Judean storage jars: Tel Aviv, v. 4, p. 28-60.

Ussishkin, D. (2014) Biblical Lachish; A Tale of Construction, Destruction, Excavation and Restoration, Israel Exploration

Society, Jerusalem - open access at academia.edu

Ussishkin, D. (2011) "On Biblical Jerusalem, Megiddo, Jezreel and Lachish -

open access at academia.edu

Ussishkin, D. (2023) The City Walls of Lachish: Response to Yosef Garfinkel, Michael Hasel, Martin Klingbeil, and their Colleagues

Published in Palestine Exploration Quarterly 155, 2023, pp. 91-110

Ussishkin, D. (2024) "The Massive Fortifications of Canaanite and Judean Lachish" – open access at academia.edu

Vaknin, Y., et al. (2024). "Archaeomagnetic Dating of the Outer Revetment Wall at Tel Lachish."

Tel Aviv 51: 73-94. - open access

Ussishkin, D. (1978), "Lachish Renewed Archaeological Excavations"

David Ussishkin (1983) Excavations at Tel Lachish 1978—1983: Second Preliminary Report, Tel Aviv, 10:2, 97-175 -

open access at academia.edu

Ussishkin, D. Third preliminary report 1985-1994

Ussishkin, D. (2004) The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973-1994), 5 volumes

W. F. Albright, ZAW, N.F. 6 (47) (1929), 3

D. W. Thomas, PEQ 72 (1940), 148~149

G. W. Ahlstrom, ibid. 112 (1980), 7~9; 115 (1983), 103~104

G. I. Davies, ibid. 114 (1982), 25~28; 117 (1985), 92~96.

W. F. Albright, BASOR 68 (1937), 22~26; 74 (1939), 11~23; 87 (1942), 32~38

N. Na'aman, VT29 (1979), 61~86; id., BASOR 261 (1986), 5~21

V. Fritz, Eretz-Israel 15 (1981), 46*~53*.

J. L. Starkey, PEQ 65 (1933), 190~199; 66 (1934), 164~175; 67 (1935), 198~207; 68 (1936),

178~189; 69 (1937), 171~179, 228~241

C. H. Inge, ibid. 70 (1938), 240~256

0. Tufnell et al., Lachish II, The Fosse Temple, London 1940; id., Lachish III, The Iron Age, London 1953; id., Lachish IV. The Bronze

Age, London, 1958

Y. Aharoni, Investigations at Lachish: The Sanctuary and the Residency ( Lachish V), Tel Aviv 1975

D. Ussishkin, TA 5 (1978), 1~97; 10 (1983), 97~175.

D. L. Risdon, Biometrika 35 (1939), 99~165

B.S. J. Isserlin and 0. Tufnell, PEQ 82 (1950), 81~91

R. D. Barnett, IEJ 8 (1958), 16H64

0. Tufnell, PEQ 91 (1959), 90~105

J. R. Bartlett, ibid. 108 (1976), 59~61

E. Stern, 'Atiqot 11 (1976), 107~109

D. Ussishkin, BASOR223 (1976), 1~13; id., TA 4 (1977), 28~60; 17 (1990), 53~86; id., The Conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib, Tel Aviv 1982; id.,

Palestine in the Bronze and Iron Ages: Papers in Honour of Olga Tujnell (ed. J. N. Tub b), London 1985,

213~230

C. Clamer, TA 7 (1980), 152~162

I. Eph'al, ibid. 11 (1984), 60~70

Y. Yadin, BAR 10/4 (1984), 65~67

S. A. Rosen, TA 15~16 (1988~1989), 193~196

S. Shalev and P. Northover, ibid., 197~205

Y. Shiloh, AASOR 49 (1989), 97~105

P. Magrill, BAlAS 9 (1989~1990), 41~45

W. G. Dever, BASOR 277~278 (1990), 121~130

G. J. Wightman, ibid., 5~22

0. Zimhoni, TA 17 (1990), 3~52

R. Hestrin, BAR 17;5 (1991), 50~59.

H. Torczyner et al., Lachish I: The Lachish Letters, London 1938

D. Diringer, PEQ 73 (1941), 38~56, 89~106; 74 (1942), 82~103; 75 (1943), 89~99

A. Lemaire, RB 81 (1974), 63~72; id., TA 3 (1976), 109~110; 7 (1980), 92~94; id., Inscriptions hebrai'ques 1: Les ostraca, Paris 1977, 83~143

M. Gilula, TA 3 (1976), 107~108

0. Goldwasser, ibid. 9 (1982), 137~138; 11 (1984), 77~93; 18 (1991), 248~253

F. M. Cross, Jr., ibid. 11 (1984), 71~76

E. Puech, ibid. 13~14 (1986~1987), 13~25

K. A. D. Smelik, PEQ 122 (1990), 133~138.

O. Zimhoni, Lachish Levels V and IV: Comments on the Material Culture of Judah in the

Iron Age II in the Light of the Lachish Pottery Repertoire (M.A. thesis), Tel Aviv 1995

D. Ussishkin et al.,

The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994) I–V (The Emery & Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology; Tel Aviv University Sonia & Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series

22), Tel Aviv 2004; ibid. (Reviews) BAR 31/4 (2005), 36–47. — BASOR 340 (2005), 83–86

D. Milson, Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen

Landes 2 (1990), 15–21

B. Brandl, The Nile Delta in Transition, Tel Aviv 1992, 441–477

Y. Dagan, Map of

Lakhish (98) (Archaeological Survey of Israel), Jerusalem 1992; id., The Settlement in the Judean Shephelah

in the 2nd and 1st Millennium B.C.: A Test-Case of Settlement Processes in a Geographic Region (Ph.D.

diss.), Tel Aviv 2000 (Eng. abstract)

D. Ussishkin, ABD, 4, New York 1992, 114–126; id., TA 23 (1996),

3–60; id., OEANE, 3, New York 1997, 317–323; id., Culture Through Objects: Ancient Near Eastern Studies (P. R. S. Moorey Fest.; Griffith Institute Publications; eds. T. Potts et al.), Oxford 2003, 207–217; id.,

Saxa Loquentur, Münster 2003, 205–211

S. Bunimovitz & O. Zimhoni, IEJ 43 (1993), 99–125

P. J. King,

Jeremiah: An Archaeological Companion, Louisville, KY 1993; id., BAR 31/4 (2005), 36–47

J. M. Russell,

Narrative and Event in Ancient Art (Cambridge Studies in New Art History and Criticism

ed. P. J. Holliday),

Cambridge 1993, 55–73

J. Woodhead, BAT II, Jerusalem 1993, 589–597

U. Hartung, MDAI Abteilung Kairo

50 (1994), 107–113

J. S. Holladay, Jr., ASOR Newsletter 44/2 (1994), n.p.

M. Kochavi (& I. Beit Arieh),

Map of Rosh ha-’Ayin (78) (Archaeological Survey of Israel), Jerusalem 1994

R. Krauss, Mitteilungen der

Deutschen Orientalischen Gesellschaft 126 (1994), 123–130

W. Zwickel, Der Tempelkult in Kanaan und

Israel (Forschungen zum Alten Testament 10), Tübingen 1994

G. A. Klingbeil, AUSS 33 (1995), 77–84; N.

Na’aman, ZAW 107 (1995), 179–195; id., PEQ 131 (1999), 65–67; id., BASOR 317 (2000), 1–7

G. Barkay

& A. G. Vaughn, TA 22 (1995), 94–97; 23 (1996), 61–74; id., BASOR 304 (1996), 29–54

G. Barkay, TA

22 (1995), 75–82; L. Nigro, Ricerche sull’architettura palaziale della Palestina nelle eta del bronzo e del

ferro (Contributi e Materiali di Archeologia Orientale 5), Roma 1995

M. Finkelberg (et al.), TA 23 (1996),

195–208; id., The Aegean and the Orient in the 2nd Millennium. Proceedings of the 50th Anniversary Symposium, Cincinnati, 1997 (eds. E. H. Cline & D. Harris-Cline), Liege 1998, 265–271; A. H. Levy, TA 23

(1996), 83–88; A. M. Maeir, EI 25 (1996), 96*

P. Magrill (& A. Middleton), Pottery in the Making (eds. I.

Freestone & D. Gaimster), London 1997, 68–73; id. (& A. Middleton), Antiquity 75/287 (2001), 137–144

id., BAIAS 21 (2003), 105–106

P. Beck, TA 25 (1998), 174–183

id., Imagery and Representation, Tel Aviv

2002, 297–306

380–384

D. Collon, MdB 108 (1998), 64–69

R. Kletter, Economic Keystones: The Weight

System of the Kingdom of Judah (JSOT Suppl. Series 276), Sheffield 1998

G. A. Rendsbourg, Aula Orientalis 16 (1998), 289–291

S. Wimmer, Jerusalem Studies in Egyptology, Wiesbaden 1998, 87–123

Z. Amar,

UF 31 (1999), 1–11

T. Haettner Blomquist, Gates and Gods: Cults in the City Gates of Iron Age Palestine:

An Investigation of the Archaeological and Biblical Sources (Coniectanea Biblica: Old Testament Series 46),

Stockholm 1999, 81–83

W. R. Gallagher, Sennacherib’s Campaign to Judah: New Studies (Studies in the

History and Culture of the Ancient Near East 18), Leiden 1999

P. A. Kaswalder, La Terra Santa Feb. 1999,

25–30

A. Millard, BH 35/4 (1999), 5–12

J. N. Tubb, Minerva 10/2 (1999), 23–26

S. A. Austin et al., International Geology Review 42 (2000), 657–671

M. Bietak (& K. Kopetzky), Synchronisation, Wien 2000,

115

id., Beer-Sheva 15 (2002), 56–85

id., Ägypten und Levante 13 (2003), 13–38

id., Symbiosis, Symbolism, and the Power of the Past, Winona Lake, IN 2003, 155–168, 546

D. Edelman, Biblical Interpretation

8 (2000), 88–103

J. M. Hadley, The Cult of Asherah in Ancient Israel and Judah (University of Cambridge

Oriental Publications 57), Cambridge 2000

A. Mederos Martin, Madrider Mitteilungen 41 (2000), 83–111

G. T. M. Prinsloo, Old Testament Essays 13(2000), 348–363

D. Bar-Yosef, ASOR Annual Meeting Abstract

Book, Boulder, CO 2001, 1

id., Mitekufat Ha’even 35 (2005), 45–52

T. Dezso, Near Eastern Helmets of

the Iron Age (BAR/IS 992), Oxford 2001

L. Kolska Horowitz & I. Milevski, Studies in the Archaeology of

Israel and Neighboring Lands, Chicago, IL 2001, 283–305

W. H. Shea, NEAS Bulletin 46 (2001), 25–42

50

(2005), 1–14

Y. Yekutieli, Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and Neighboring Lands, Chicago, IL 2001,

659–688

J. A. Blakely & J. W. Hardin, BASOR 326 (2002), 11–64

S. Feldman, BAR 28/3 (2002), 46–51

H. Richter, Die Phönizischen Anthropoiden Sarkophage, 2: Tradition, Rezeption, Wander (Forschungen zur

Phönizisch-Punischen und Zyprischen Plastik I/2

ed. S. Frede), Mainz 2002, 243–271

C. Uehlinger, “Like

a Bird in a Cage”: The Invasion of Sennacherib in 701 BCE (JSOT Suppl Series 363

European Seminar in

Historical Methodology 4

ed. L. L. Grabbe), Sheffield 2003, 221–305

H. Huber et al., Ägypten und Levante

13 (2003), 83–105

K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, Grand Rapids, MI 2003 (subject

index)

E. Yannai et al., Levant 35 (2003), 101–116

D. F. Graf & M. J. Zwettler, ibid., 53–89

Y. Goren et al.,

Inscribed in Clay, Tel Aviv 2004, 287–289

H. Katz, TA 31 (2004), 268–277

N. Lalkin, ibid., 17–21

M. G.

Micale & D. Nadali, Iraq 66 (2004), 163–175

S. M. Ortiz, The Future of Biblical Archaeology: Reassessing

Methodologies and Assumptions. The Proceedings of a Symposium, 12–14.8.2001 at Trinity International

University (eds. J. K. Hoffmeier & A. Millard), Grand Rapids, MI 2004, 121–147.

Z. B. Begin, As We Do Not See Azeqa: In Search of the Lachish Letters, Jerusalem 2000 (Heb.).

B. Halpern, BASOR 285 (1992), 83–85 (Review)

H. Sauren, Le Museon 105 (1992), 213–242

R.

A. Di Vito, ABD, 4, New York 1992, 126–128

H. M. Barstad, EI 24 (1993), 8*–12*

S. B. Parker, Uncovering Ancient Stones (H. N. Richardson Fest.; ed. L. M. Hopfe), Winona Lake, IN 1994, 65–78

J. Renz, Die

Althebräischen Inschriften, 1 (Handbuch der Althebräischen Epigraphik), Darmstadt 1995, 74–76, 217–219,

280, 312–315, 405–437, 439

W. Nebe, Zeitschrift für Althebraistik 9 (1996), 48; D. Pardee, OEANE, 3, New

York 1997, 323–324

P. Boudreuil et al., NEA 61 (1998), 2–13

O. Pedersen, Archives and Libraries in the

Ancient Near East: 1500–300 B.C., Bethesda, MD 1998, 227–228

I. M. Young, VT 48 (1998), 408–422;

Z. B. Begin (& A. Grushka), EI 26 (1999), 226*–227*; id., VT 52 (2002), 166–174

P. A. Kaswalder, La

Terra Santa Feb. 1999, 25–30

H. Misgav, EI 26 (1999), 231*

N. Na’aman, PEQ 131 (1999), 65–67; id.,

VT 53 (2003), 169–180

H. Eshel, Zeitschrift für Althebraistik 13 (2000), 181–187

W. M. Schniedewind,

ibid., 157–167

J. A. Emerton, PEQ 133 (2001), 2–15

U. Rueterswörden, Steine-Bilder-Texte: Historische

Evidenz ausserbiblische und biblischer Quellen (Arbeiten zur Bibel und ihrer Geschichte 5; ed. C. Hardmeier), Leipzig 2001, 179–192

F. M. Cross, Jr., Leaves from an Epigrapher’s Notebook: Collected Papers

in Hebrew and West Semitic Palaeography and Epigraphy (Harvard Semitic Studies 51; Harvard Semitic

Museum Publications), Winona Lake, IN 2003, 133–134

R. G. Lehmann, Bote und Brief: Sprachliche

Systeme der Informationsübermittlung im Spannungsfeld von Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit (Nordostafrikanisch/Westasiatische Studien 4; ed. A. Wagner), Frankfurt am Main 2003, 75–101

A. Lemaire, The

Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994), IV (The Emery & Claire Yass Publications

in Archaeology

Tel Aviv University Sonia & Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series 22),

Tel Aviv 2004, 2099–2132.