Samaria/Sebaste

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Samaria | Hebrew | שֹׁומְרוֹן |

| Sebaste | Greek | Σεβαστή |

| Somron | Biblical Hebrew | שֹׁמְרוֹן |

| Shomron | Biblical Hebrew | שֹׁמְרוֹן |

| as-Sāmirah | Arabic | السامرة |

| House of Khomry | Assyrian | |

| Bet Ḥumri | Early (Assyrian?) cuneiform inscriptions | |

| Samirin | Cuneiform inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III (ruled 745–727 BCE) and later | |

| Shamerayin | Aramaic |

Samaria, the capital of the kingdom of Israel and center of the region of Samaria, bears the name of the hill of Samaria on which Omri, king of Israel, built his city. The site is identified with the village of Sebastia (c. 10 km. northeast of Shechem). The place was renamed Sebaste by Herod when he rebuilt the city. The town lay on a high hill (430 m above sea level), towering over its surroundings. It was situated at a crossroads near the main highway running northward from Shechem, in a fertile agricultural region. Its topographic and strategic advantages were probably why the site was chosen for the capital of the kingdom of Israel, even though it lacked an adequate water supply.

The Bible records the foundation of Samaria: "In the thirty-first year of Asa king of Judah, Omri began to reign over Israel, and reigned for twelve years; six years he reigned in Tirzah. He bought the hill of Samaria from Shemer for two talents of silver; and he fortified the hill, and called the name of the city which he built, Samaria, after the name of Shemer, the owner of the hill" (1 Kings 16:23-24). Even after the fall of Israel, the Assyrians called it the house of Khomry, after Omri, the founder of the dynasty and of Samaria. Omri succeeded in strengthening the kingdom, but because of his failures in his wars with Aram, he was forced to cede to the king of Aram "streets" in Samaria for merchants to set up their bazaars (1 Kg. 20:34).

Ahab, Omri's son, reigned from 873 to 852 BCE. Toward the end ofhis reign, Samaria was besieged by Ben-hadad II, king of Aram, and his allies (1 Kg. 20: 1). Ahab struck back at Ben-hadad, at the gates of Samaria. Later, following a decisive battle at Aphek (1 Kg. 20:26-30), he obtained the return to Israel of the cities previously captured by the Arameans. He also acquired trade concessions in the markets of Damascus (1 Kg. 20:34). In the battle with the Assyrians at Qarqar (853 BCE), Ahab occupied an important position among the twelve members of the coalition. According to Assyrian sources, his army consisted of two thousand cavalry and ten thousand foot soldiers. In the last year of his reign, Ahab and his ally, the Judean king Jehoshaphat, waged war with the Arameans to recapture Ramoth-Gilead for Israel. Before setting out to battle, the two kings sat on the threshing floor at the entrance to the gate at Samaria and asked the prophets to ask God what lay before them ( 1 Kg. 22:1-1 0). In the battle of Ramoth-Gilead, Ahab was fatally wounded. His body was brought to Samaria and his chariot was washed of his blood in the pool ofSamaria (l Kg. 22:33-38). With the marriage of Ahab and Jezebel, the daughter of Ethbaal, king of Tyre, the alliance with Tyre was consolidated, and its cultural influence on Israel increased. For his wife, Ahab built a sanctuary to Baal and Astarte in Samaria (1 Kg. 16:32-33; 2 Kg. 10:21) and a temple in the city of Jezreel, thus arousing the wrath of the prophets of lsrael, especially Elijah's. The statement in the Bible "Now the rest of the acts of Ahab, and all that he did, and the ivory house which he built, and all the cities that he built. .. " (1 Kg. 22:39) suggests that Ahab was a man of unbounded energy and a zealous builder.

The reign of Joram, the son of Ahab, witnessed a decline in the political and economic position of the kingdom of Israel. Samaria was put under heavy siege by the Aramean king Ben-hadad, and famine spread through the city (2 Kg. 6:24~30). In connection with this great famine, the Bible relates that the "gate of Samaria" was the marketplace for food (2 Kg. 7:1). When Joram renewed the war against Aram for Ramoth-Gilead, Jehu, the commander of his army, who had been anointed king by the prophet Elisha, revolted against Joram. Jehu annihilated Ahab's family and put an end to the cult of Baal in Samaria. He paid tribute to the Assyrians in 841 BCE. His submission is related on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III. On the obelisk Jehu is referred to as the "Son of Omri," that is, king over the land of the House of Omri (which was Israel). Jehu lost large tracts of land east of the Jordan. In the days of the great Israelite king, Jeroboam II (784~ 748 BCE), Samaria reached the zenith of its prosperity and expansion. Jeroboam conquered Damascus, extending the borders of his kingdom from Hamath to the sea of the Arabah (2 Kg. 14:23~29). In the days of Samaria's greatness, a powerful aristocracy emerged that pursued a life of luxury. Instances of injustice appeared, causing the prophet Amos to protest strongly against the luxuries in the palaces and "ivory houses" in Samaria and against the pomp of the cult at Bethel (Am. 3:9~15, 4:4).

The beginning of the decline and disintegration of the kingdom of Israel followed the death of Jeroboam. Menahem, king of lsrael, had to pay heavy tribute to the Assyrians in 783 BCE. Large territories were split from the country during the military expeditions of Tiglath-pileser III in 734 and 733 BCE. Pekah and Hoshea attempted to revolt against the Assyrians, but Shalmaneser V marched against Samaria and held it under siege for three years. In 722 BCE, Sargon II conquered the city and many of its inhabitants were deported to remote districts in the Assyrian empire (2 Kg. 17:5-6, 18:9-10). Samaria became the center of the province of the same name and the seat of the Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian governors. The Assyrian kings settled colonists there from various countries (2 Kg. 17:24). They mixed with the local Israelite population, creating an increasing cultural and religious amalgamation. During a period of Assyrian weakness, Josiah, king of Judah (2 Kg. 23:8), raided the towns of Samaria and destroyed the high places (bamot) set up by the kings of lsrael. This event encouraged those in Samaria who had remained faithful to the Lord, and many of them went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem after its conquest by Nebuchadnezzar (Jer. 41:5). Nevertheless, in the course of time, a Samaritan community arose in Samaria that broke away from the people of Israel. Sanballat the Horonite, the Persian governor of Samaria, stood at the head of the opposition to the building of the city wall in Jerusalem in the time of Nehemiah.

When the Persian empire fell to Alexander the Great, Samaria too was conquered (332 BCE), and thousands of Macedonian soldiers were settled here. Samaria became a Greek city, differing in its ethnic, cultural, and religious point of view from the provincial cities of the Samaritans, whose religious center was Mount Gerizim. During the reigns of the Hellenistic kings, Samaria experienced a number of wars and conquests, but no destruction so complete as that inflicted upon it by the Hasmoneans under John Hyrcanus in 108 BCE. According to Josephus, Hyrcanus razed the city and sold its inhabitants into slavery.

In the time of Pompey (63 BCE), Samaria was annexed to the Roman province of Syria, and under Gabinius (57 BCE) the city revived. In 30 BCE, the emperor Augustus granted it to King Herod, who rebuilt it, adorned it with buildings, and named it Sebaste, in honor of Augustus (in Greek Sebastos = Augustus) (Josephus, Antiq. XV, 246). Herod, too, settled foreign soldiers here, and again the complexion of the city's population changed. During the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, from 66 to 70 CE, the city was once more destroyed. Septimius Severus granted it the status of a Roman colony with all the inherent privileges in 200 CE. Although the city had already begun to decline when Christianity became dominant, in the fourth century CE Sebaste became the seat of a bishop. A popular tradition locating the tomb of John the Baptist here lent the site a certain importance in the eyes of the Christians, who built churches here. After the Arab conquest, various travelers described the many extant ruins

- from Gibson (2014)

Two major archaeological expeditions excavated at Samaria. From 1908 to 1910, an expedition from Harvard University excavated here, first on a small scale, underthedirectionofG. Schumacher, and later more extensively under G. A. Reisner and C. S. Fisher. This expedition unearthed the western part of the fortress (the acropolis) from the time of the dynasties ofOmri and Jehu, includingthecasematewalls, the royal residence, and the storehousewithin its precincts. Especially noteworthy finds are the ostraca (see below). Also uncovered were the ruins of the Hellenistic fortifications of the acropolis, the Roman city wall, thewestgate,houses, the temple of Augustus, the forum, the basilica, and the stadium. The second expedition was a consortium of five institutions that worked at the site from 1931 to 1935: Harvard University, the British Palestine Exploration Fund, the British Academy, the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The director of the excavations was J. W. Crowfoot, with E. L. Sukenik as assistant field director. K. Lake represented Harvard University. K. M. Kenyon and G. M. Crowfoot also participated in the expedition, assuming a major role in the publication of the excavation report, as well as N. Avigad and the architect J. Pinkerfeld. The Joint Expedition extended the area previously excavated by clearing the fortress of the Israelite kings. The finds from the royal quarter included a collection of ivory carvings. A burial cave and a cult place(?) from the Israelite period were also uncovered. Smaller projects included the exploration of the Hellenistic fort, the colonnaded street, the forum, and the stadium. Also discovered were the remains of a temple dedicated to the goddess Kore, a theater, Roman tombs, and a church; the water system of the Roman city was investigated.

The excavators met with considerable difficulty in distinguishing between the various strata because the town had been destroyed several times. The builders had dismantled previous structures, reused their stones, and deepened foundations down to bedrock. Building foundations from different periods were therefore frequently found side by side, rather than superimposed. Foundation trenches that penetrated several strata of construction disturbed the stratigraphy and the deposits. The conditions on the site forced the excavators to dig according to the strip system: the earth removed from every excavated strip was dumped into the previously excavated strip, a system with numerous disadvantages.

From 1965 to 1967, small-scale excavations were conducted at Samaria under the sponsorship of the Jordan Department of Antiquities, directed by F. Zayadine. These investigations were concentrated mainly in the area of the theater, the colonnaded street, the west gate, and the temple of Augustus. An Iron Age tomb was also uncovered. In 1968, the western sector of the mound was briefly examined by J. B. Hennessy, who exposed several strata from the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

- Fig. 4 - Location Map from

Tappy (2014)

Figure 4.18

Figure 4.18

Map of Israel

(Ron E. Tappy)

Tappy (2014)

- Fig. 4 - Location Map from

Tappy (2014)

Figure 4.18

Figure 4.18

Map of Israel

(Ron E. Tappy)

Tappy (2014)

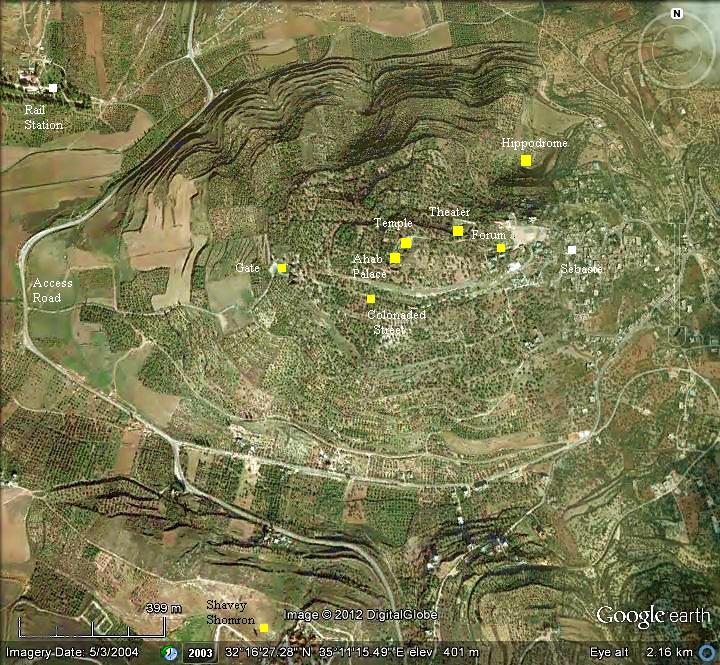

- Annotated Aerial View of

Samaria/Sebaste from BibleWalks.com

- Samaria/Sebaste in Google Earth

- Samaria/Sebaste on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated Aerial View of

Samaria/Sebaste from BibleWalks.com

- Samaria/Sebaste in Google Earth

- Samaria/Sebaste on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 4.15 - Site plan of

Samaria-Sebaste from Tappy (2014)

Figure 4.15

Figure 4.15

Site plan of Samaria-Sebaste

(Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London)

Tappy (2014) - Fig. 4.16 - Summit plan of

Samaria from Tappy (2014)

Figure 4.16

Figure 4.16

Summit plan of Samaria

(Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London; adapted by Ron E. Tappy)

Tappy (2014) - Fig. 20 - Google Earth

view of Samaria, indicating the main elements that make up the site from Finkelstein (2013)

Figure 20

Figure 20

Google Earth view of Samaria, indicating the main elements that make up the site.

Finkelstein (2013)

- Fig. 4.15 - Site plan of

Samaria-Sebaste from Tappy (2014)

Figure 4.15

Figure 4.15

Site plan of Samaria-Sebaste

(Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London)

Tappy (2014) - Fig. 4.16 - Summit plan of

Samaria from Tappy (2014)

Figure 4.16

Figure 4.16

Summit plan of Samaria

(Courtesy of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London; adapted by Ron E. Tappy)

Tappy (2014) - Fig. 20 - Google Earth

view of Samaria, indicating the main elements that make up the site from Finkelstein (2013)

Figure 20

Figure 20

Google Earth view of Samaria, indicating the main elements that make up the site.

Finkelstein (2013)

- Fig. 22 - Architectural

section through the southern side of the Acropolis and lower platform at Samaria from Finkelstein (2013)

Figure 22

Figure 22

An architectural section through the southern side of the Acropolis and lower platform at Samaria

Finkelstein (2013)

Although

Austin et. al. (2000) state that according to Yadin et al. (1960:36),

traces of the middle-eighth-century earthquake were found at Samaria

no such reference is to be found [by JW] in

Yadin et al. (1960:36),

Yadin et al. (1960),

Yadin et al. (1958),

or Yadin et al. (1961).

Austin et. al. (2000) noted that no detailed excavation report [of Samaria-Sebaste] has been published concerning this period

and added the following observation

Samaria was the capital of Israel at the time of the earthquake. The biblical records indicate that Samaria received severe damage to palace-fortresses, walls, and houses (Amos 3:11; 4:3; 6:11). Pride in Israel’s royal citadel and fear of an Assyrian invasion would have been incentives for Samaria to upgrade quickly from the fallen mud brick to stronger hewn stone (Isaiah 9:9,10 [Heb. 9:8,9]).

Assuredly,

Thus said the Sovereign GOD:

An enemy, all about the land!

He shall strip you of your splendor,

And your fortresses shall be plundered.

לָכֵ֗ן כֹּ֤ה אָמַר֙ אֲדֹנָ֣י יֱהֹוִ֔ה צַ֖ר וּסְבִ֣יב הָאָ֑רֶץ וְהוֹרִ֤יד מִמֵּךְ֙ עֻזֵּ֔ךְ וְנָבֹ֖זּוּ אַרְמְנוֹתָֽיִךְ

And taken out [of the city]—

Each one through a breach straight ahead—

And flung on the refuse heap

—declares GOD

וּפְרָצִ֥ים תֵּצֶ֖אנָה אִשָּׁ֣ה נֶגְדָּ֑הּ וְהִשְׁלַכְתֶּ֥נָה הַהַרְמ֖וֹנָה נְאֻם־יְהֹוָֽה

For GOD will command,

And the great house shall be smashed to bits,

And the little house to splinters.

כִּֽי־הִנֵּ֤ה יְהֹוָה֙ מְצַוֶּ֔ה וְהִכָּ֛ה הַבַּ֥יִת הַגָּד֖וֹל רְסִיסִ֑ים וְהַבַּ֥יִת הַקָּטֹ֖ן בְּקִעִֽים

“Bricks have fallen—

We’ll rebuild with dressed stone;

Sycamores have been felled—

We’ll grow cedars instead!”

לְבֵנִ֥ים נָפָ֖לוּ וְגָזִ֣ית נִבְנֶ֑ה שִׁקְמִ֣ים גֻּדָּ֔עוּ וַאֲרָזִ֖ים נַחֲלִֽיף

So GOD let the enemies of Rezin

Triumph over it

And stirred up its foes—

אֲרָ֣ם מִקֶּ֗דֶם וּפְלִשְׁתִּים֙ מֵאָח֔וֹר וַיֹּאכְל֥וּ אֶת־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל בְּכׇל־פֶּ֑ה בְּכׇל־זֹאת֙ לֹא־שָׁ֣ב אַפּ֔וֹ וְע֖וֹד יָד֥וֹ נְטוּיָֽה

The Holy Spirit was showing by this that the way into the Most Holy Place had not yet been disclosed

as long as the first tabernacle was still functioning. This is an illustration for the present time,

indicating that the gifts and sacrifices being offered were not able to clear the conscience of the worshiper.

τοῦτο δηλοῦντος τοῦ πνεύματος τοῦ ἁγίου, μήπω πεφανερῶσθαι τὴν τῶν ἁγίων ὁδόν, ἔτι τῆς πρώτης σκηνῆς ἐχούσης στάσιν·

ἥτις παραβολὴ εἰς τὸν καιρὸν τὸν ἐνεστηκότα, καθ' ἣν δῶρά τε καὶ θυσίαι προσφέρονται μὴ δυνάμεναι κατὰ συνείδησιν τελειῶσαι τὸν λατρεύοντα,

- from Crisler (2004)

By Vern Crisler

Copyright, 2004

Rough Draft

1. INTRODUCTION:

We’ve discussed some of the major foundations for the New Courville chronology of the ancient world. First, the MB1 pottery strata was matched to the Exodus & Conquest (c. 1445-1405 BC); second, the MB2c pottery strata was matched to the time of Abimelech (c. 1175 BC); third, the heap of stones at Ai, which provides what could be described as in-your-face proof that the Conquest took place at the end of the Early Bronze Age; fourth, that the last walls of EB3 Jericho (both the massive wall and the hastily built structure on top of it) fell at the time of Joshua’s Conquest; fifth, that Judge Deborah could be correlated to the time of Hammurabi based upon the identification of Jabin 2 with Jabin, king of Hazor, mentioned in the Mari letters; and sixth, the Iron age bit hilani building could be moved down to the 9th century on the basis of the Low Chronology of the Iron age, and provide a correlation with the building program of Hiel the Bethelite.

The next major foundation for the New Courville chronology is the archaeology of Samaria. Courville himself recognized the importance of Samaria as providing a valuable chronological clue. He says,

“There is probably no incident in all Bible history that is regarded as more solidly synchronized with archaeological evidences than is the case of the building of the city of Samaria by Omri, king of Israel (dated by Thiele 885-876 B.C.).” (The Exodus Problem and Its Ramifications, Vol. 2, p. 213)

Expectations for a match between the Bible and archaeology would seem to have been particularly high given the biblical description of Samaria’s founding.

“In the thirty-first year of Asa king of Judah, Omri became king over Israel, and reigned twelve years. Six years he reigned in Tirzah. And he bought the hill of Samaria from Shemer for two talents of silver; then he built on the hill, and called the name of the city which he built, Samaria, after the name of Shemer, owner of the hill. Omri did evil in the eyes of the LORD, and did worse than all who were before him.” (1Kings 16:23-25.)

Courville says, “It has been inferred from the Scriptural account that the city built by Omri was on a site not previously occupied, though admittedly the account does not say so. If this assumption is correct, then the lowest city to be observed from an archaeological examination of the site should be readily identifiable as that built by Omri. The pottery in association with that city could then be dated to the era of Omri’s reign, and this pottery could then be used as an index type for dating levels in other mounds of Palestine containing similar pottery.” (Courville, Vol. 2, p. 215.)

Nothing would seem to be more straightforward than to associate the time of Omri with the earliest archaeological material showing extensive building on the site at Samaria. The resulting index pottery could then be synchronized with a great deal of similar material across Palestine. Courville says, “With such a solid synchronism between Scripture and archaeology, it would seem that the proof of the general correctness of the currently accepted chronological structure of the ancient world could be considered as virtually settled, at least back to the incident of the Exodus.” (Idem.)

Nevertheless, expectations of a typology that could be directly tied to the time of Omri could not be fulfilled. That is because any synchronism between the relevant pottery on the site with the time of Omri turned out to be in contradiction to the dating of the pottery established elsewhere to the “tenth century” by conventional chronology. The New Courville chronology would then agree with Courville that the conventional chronology has once again made it impossible for archaeologists to come to a correct interpretation of the archaeology of Samaria:

“With the numerous anachronisms and anomalies to which attention has been called in this work, the question must logically be regarded as still open to debate as to whether or not the era of the origin of Samaria has been properly correlated with the corresponding era of other Palestinian sites.” (Idem.)

2. SAMARIA IN THE BIBLE & AFTER

After Solomon’s death, the kingdom of Israel was divided into two kingdoms, the northern tribes, who were referred to as “Israel,” and the southern tribes, who were called “Judah” (or later “Judea”). The city of Samaria would eventually became the de facto capital of the northern kingdom, just as Jerusalem was the capital of the southern kingdom.

Hayim Tadmor argues that the name “Samaria” predated the time of Omri, the king who built the city of Samaria as recorded in the Bible. (“Some Aspects of the History of Samaria During the Biblical Period,” The Jerusalem Cathedra, 1983, Jerusalem, Vol. 3, p. 3.) His reasoning is that if Omri had purchased a bare, unnamed hill, he would have named it after himself, just as Assyrian king Sargon perpetuated his own name in calling his new capital, Dur-Sharrukin (Sargon’s Fort). (Idem.)

Yet there are few, if any, instances of Hebrew kings naming cities after themselves. While it’s true that Jerusalem was called the “city of David,” this only means that Jerusalem had an alternative designation. The term “Jerusalem” is the actual name of the city of Jerusalem, and the term “city of David” is not a name but rather a definite description. Thus, there is no a priori reason that Omri would name a city after himself, and this leaves very little reason to think that the name “Samaria” predates the time of Omri.

It might be argued that 1 Kings 13:32 gives evidence of a pre-Omride use of the name. We read, starting from verse 29, the following:

“And the prophet took up the corpse of the man of God, laid it on the donkey, and brought it back. So the old prophet came to the city to mourn, and to bury him. Then he laid the corpse in his own tomb; and they mourned over him, saying, ‘Alas, my brother!’ So it was, after he had buried him, that he spoke to his sons, saying, ‘When I am dead, then bury me in the tomb where the man of God is buried; lay my bones beside his bones. For the saying which he cried out by the word of the LORD against the altar in Bethel, and against all the shrines on the high places which are in the cities of Samaria, will surely come to pass.’ After this event Jeroboam did not turn from his evil way, but again he made priests from every class of people for the high places; whoever wished, he consecrated him, and he became one of the priests of the high places.” (Emphasis added.)

Even though the content of the book of Kings was written during or close to the time of the historical occurrences mentioned, the final compilation and editing only took place during the Exile. This is based on internal evidence, e.g., 2 Ki. 25:27. For time indicators showing the earliness of the book’s contents, see 1 Ki. 8:8, describing the poles of the ark of the covenant: “So they are there to this day”; also 1 Ki. 12:19: both Israel and Judah still in existence; also 2 Ki. 2:22: water remains healed to this day; also 2 Ki 10:26; 17:18, 23, etc.

There is no indication that the biblical editors felt any difficulties with adding to or paraphrasing the quotations from actual speakers, if they thought it would help the reader better to understand the text. Because of these historical “commentaries” on the ancient texts, the possibility of anachronism arises. An historical anachronism would be something like this: “Columbus discovered America.” Obviously, this is not strictly correct, since the land was not called “America” when first discovered, but we let it go because we know what it means. In other words, we (ordinarily) know the difference between use and mention of a word. In a similar way, biblical references are sometimes anachronistic when a later editor adds an explanatory gloss to a text. This is what has happened in 1 Kings 13:32. Indeed, the indication is that the gloss was written at a time when the northern tribes were referred to in general as “Samaria” (the cities of Samaria).

The second anachronistic reference is 1 Kings 16:22-24:

“But the people who followed Omri prevailed over the people who followed Tibni the son of Ginath. So Tibni died and Omri reigned. In the thirty-first year of Asa king of Judah, Omri became king over Israel, and reigned twelve years. Six years he reigned in Tirzah. And he bought the hill of Samaria from Shemer for two talents of silver; then he built on the hill, and called the name of the city which he built, Samaria, after the name of Shemer, owner of the hill” (Emphasis added.)

Here we have the same “Columbus discovered America” type of anachronism. The historian is referring to the hill of “Samaria” even though it was not called by that name until Omri named it Samaria after a tribal kinsman named Shemer. The fact that the Bible goes out of its way to explain the origin of the name of the city is a strong historical indicator that the hill lacked a name before Omri’s time. And this would only be the case if the hill was an empty hill, i.e., a hill with no already existing city on top of it with a name of its own.

During later times, Samaria was besieged by Shalmaneser 5 and finally captured by Sargon 2, who deported its inhabitants, and resettled the land (2 Ki. 17:24). Thereafter, the city of Samaria was in possession of the Assyrians, the Persians, the Grecians, and then the Romans. Herod expanded the city and called it Sebaste. In New Testament times, Jesus would compare the acts of charity and piety of the despised Samaritans to the moral display and ethical indifference of the Pharisees.

3. KENYON’S EXCAVATIONS

Kathleen Kenyon was part of the Joint Expedition to Samaria headed by J. W. Crowfoot in 1931. Since that time, she became the premier British archaeologist in Holy Land archaeology, known primarily for her work at Samaria, Jericho, and Jerusalem. Her “debris analysis” methodology – or the Wheeler-Kenyon method – is an accepted part of archaeological field work to this day. This method involved the creation of catwalks or “balks” followed by painstaking stratigraphic analysis. It has been criticized for that very reason, that it takes too long. The Kenyon method is now often combined with the “Israeli” method, which focuses more on whole architectural units. (For an overview, see the article by Joe Seger, “Prominent British Scholar Assesses Kathleen Kenyon,” BAR, Jan/Feb., 1981.)

Hershel Shanks, the editor of Biblical Archaeology Review, once implied that Kenyon’s “anti-Zionism” might have influenced her archaeological work. (Cf., “Kathleen Kenyon’s Anti-Zionist Politics – Does it Affect Her Work?” BAR, Sept. 1975, 1:3.) It seems to me that his criticism amounted to little more than “emphasis” criticism. He purported to find anti-Zionism in what Kenyon “stresses and what she ignores.” Yet he himself admits that it would be wrong to “search for political bias in all the disagreements between Miss Kenyon and Israeli archaeologists.” Kenyon replied with an indignant letter, and of course she certainly had grounds for being upset. Shanks’ criticism sounded a lot like the politician who promises with respect to his opponent that, “I don’t support the suggestion that my opponent is an axe-murderer.”

While we understand the sensitivity behind Shanks’ questions about anti-Zionism, we cannot really find it, or even a hint of it, in Kenyon’s archaeological work. In those cases where she might have made negative evaluations of Israelite culture and history, we believe that such negativity stems from conventional chronology rather than from political bias. It is conventional chronology that brings many archaeologists to deny the historical nature of Israel’s history, or to ascribe its culture to Canaanite influence, or to leave Israel unexemplified in the archaeological record except by Iron 1 squatters.

Kenyon needs no defenders when it comes to her importance as an archaeologist. And yet, some have denigrated her professional competence, and not for reasons involving political bias. This negative evaluation of Kenyon is easily seen as deriving from her archaeological findings at Samaria. G. E. Wright provided the first substantial criticism of Kenyon’s observations at Samaria, and this began a methodological dispute that hasn’t ended yet. It provides a point of departure for the debate over the High or Low Chronology of the Iron Age, which we hope to describe in the near future.

4. METHODOLOGICAL DISPUTE

The archaeological history of Samaria from its beginnings to the Assyrian conquest was divided by Kenyon into six phases. (I have used Thiele’s dates for standardization.) The phases are as follows:

| Period

per Kenyon |

Dates BC

|

Kings |

| I | 885-874 | Omri |

| II | 874-853 | Ahab |

| III | 841-814 | Jehu, et al. |

| IV | 793-753 | Jeroboam 2 et al. |

| V-VI | 753-721 | Menahem, et al. to Sargon 2 |

In his BASOR essay (155, 1959, pp. 13 ff), G. E Wright argued two main points, a) that Omri could not have built Samaria period 1 in his short reign, and b) that the pottery of Samaria periods 1 & 2 belongs to the 10th century rather than to the 9th century. On the first point, Wright assumes that a city like Samaria could not have been built within 6 years, but he offers no proof for this conclusion. Moreover, it’s not likely that Omri waited until the 6th year of his twelve-year reign to begin the construction of Samaria. Archaeologists now believe that Omri built the city early in his reign, and only moved into it when it was completed. Nahman Avigan says:

“[I]t is highly improbable that Omri would have established his residence in a city that was not walled and in which there were no quarters suitable for a king. In all probability, he began the fortifications of the hill and the building of his palace while still living in his first capital, Tirzah. He would have transferred his capital to Samaria only after the site had been prepared—that is, after the main buildings had been wholly or nearly finished.” (article on Samaria, The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, 4:1303.)

The second main point, that Samaria 1 & 2 pottery belongs to the 10th century rather than to the 9th, as Kenyon had argued, shows either that Kenyon has misdated the pottery of Samaria by a hundred years, or that the conventional chronology’s assignment of similar pottery to the 10th century, is a hundred years too early. In order to sustain the conclusion that the pottery is 10th century rather than 9th century, Wright had to argue that Omri did not purchase a bare hill but that he purchased one with a “hill with a village on it, one which Mazar suggests was the estate of an Issachar family.” (Wright, p. 20.)

Wright notes that the pottery from Samaria 1 & 2 is virtually the same pottery:

“No distinction is observed to differentiate Pottery Periods I and II.” (Wright, p. 21, ftn. 24.)

It is this pottery that is used as the fill under the first two building phases. This means that the pottery from Samaria period 1 & 2 not only antedated the second archaeological building phase at Samaria but also antedated the first building phase at Samaria. This seems a radical position to take, but it’s logical given Wright’s premises. Since he believes Samaria period 1 & 2 pottery shows a “considerable mixture of pottery ranging between the 11th and 9th cent[uries]” (p. 22, ftn. 24, cont.), and since he agrees with Kenyon’s 9th century date for the first two major archaeological phases, he has no choice but to assign the pottery to an early date than both of the building phases. He says,

“While in the last analysis only the excavator knows all the facts needed for final decision, this writer concludes from the published report only that the stratified debris of Pottery I and II says no more about Building Periods I and II than that the latter are later than the former.” (Wright, p. 22.)

It should be noticed that Wright distinguishes between Building Periods and Pottery Periods. It does not appear that Kenyon accepted this distinction save as a scholarly courtesy perhaps. In her 1964 essay, “Megiddo, Hazor, Samaria and Chronology,” (Institute of Archaeology, London 4), Kenyon distinguishes between pottery and building phases, but in her book, Royal Cities of the Old Testament, published in 1971, she no longer uses this distinction, and makes her disagreement with Wright pretty clear:

“Excavations have confirmed that he [Omri] built on a virgin site. There had been some occupation on the hill in the late 4th millennium [sic, EB1], but from then on there were no buildings until those of the period of Omri.” (p. 73).

As we have pointed out, Wright’s argument for separating the pottery from the building periods is due to the fact that he feels constrained by the conventional dating of this pottery. He says,

“When one examines the pottery attributed to Periods I and II according to the chronology reviewed at the beginning of this paper, his immediate conclusion is that this is the type of thing that we have hitherto been dating to the 10th century B. C. That observation has been made also by W. F. Albright and Lawrence A. Sinclair, as well as by two members of the Hazor Expedition, Ruth Amiran and Y. Aharoni. The last two are surely correct, therefore, when they forthrightly state that Pottery Periods I-II at Samaria prove that a settlement existed there in the 10th or early 9th century, ‘but was completely razed by the great building operations of Omri and Ahab.’ The evidence certainly suggest that Omri purchased, not a bare hill, but a hill with a village on it, one which Mazar suggests was the estate of an Issachar family.” (Wright p. 20.)

In a footnote, Wright says with regard to the use of the terminology of Pottery Periods 1 & 2, that “This is the writer’s suggested terminology for the Samaria pottery stratification to distinguish it from the ‘Building Periods.’ It is the contention of this article that the two are not necessarily to be identified” (ftn. 21).

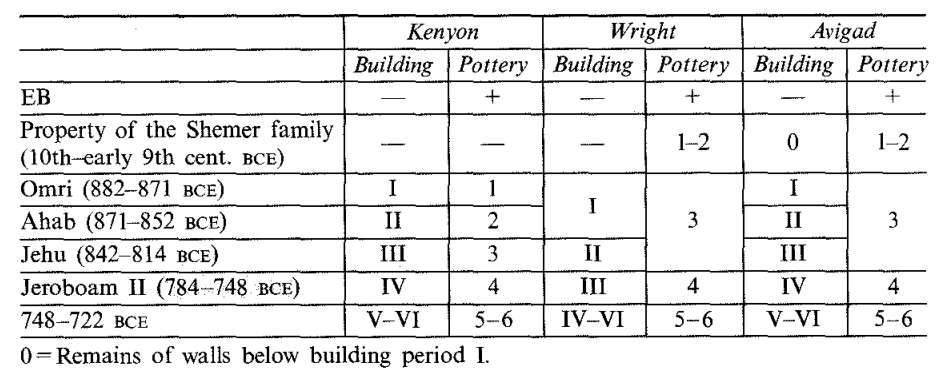

The following represents a chart of current views regarding how the buildings periods and pottery periods should be related. It is based on Avigad’s chart on p. 1303 of his New Encyclopedia article on Samaria:

| Kenyon | Wright | Avigad | |

| Building Pottery | Building Pottery | Building Pottery | |

| EB | |||

| Shemer Family | 1-2 | 1-2 | |

| Omri | I 1 | I 3 | I 3 |

| Ahab | II 2 | I 3 | II 3 |

| Jehu | III 3 | II 3 | III 3 |

| Jeroboam 2 | IV 4 | III 4 | IV 4 |

| to Sargon 2 | V 5-6 | IV-VI 5-6 | V-VI 5-6 |

In order to sustain his contention, Wright had to find a way to explain how a field archaeologist could have gotten it so wrong. Unfortunately, Wright set a difficult task for himself, for Kenyon was not just any field archaeologist; she was, in fact, as Wright admits, “one of the leading field archaeologists of our generation” (Wright, p. 17). With respect to her excavations at Samaria, he affirmed, “the Kenyon work at Samaria is one of the most remarkable achievements in the history of Palestinian excavation” (Idem). So in order for his own conclusion to go through, or sound plausible at least, Wright had to challenge not her work, but rather her methodology.

He seized upon a statement she made in her report wherein she explains how she dated the buildings at Samaria. “It is therefore only the pottery of the period of construction that can safely be associated with a building, and not that of the succeeding period of occupation” (from Samaria-Sabaste III, pp. 94, 98-107; quoted by Wright, p. 21.) Kenyon came to this methodological conclusion based upon her observation that stone buildings at Samaria do not produce a continuous sequence of deposits as do mud-brick buildings in other towns. Thus, the only safe way to date the time of construction of Samaria’s buildings was by means of the fill used as construction material beneath the floors. Wright points out, however, that the material below a floor could very well contain indicia from much earlier periods than the building. In his argument against Kenyon’s methodological principle, Wright offers another:

“In this [Kenyon’s] view, then, the pottery under a floor or ancient surface level dates the time when the floor or surface was first prepared, as also the walls with which it was associated. This may be true for certain of the latest elements under a floor; but the debris there may also contain much earlier material, and on a priori grounds one can have little confidence in an assumption like that used for the Samaria stratification when it becomes a principle for archaeological work in stone houses. A much safer principle would appear to be the one commonly used by other archaeologists: namely that, barring evident disturbance, the material lying on a floor comes from the time when the floor was last used…. If the interval between the disuse of a given floor and the construction of a new one is not great, then the latest pottery below a given floor may indeed indicate the approximate time when the floor was laid.” (Wright, p. 21.)

Wright needed to argue this point because his contention is that the fill beneath the 9th century buildings goes back to the 10th century, and for this reason, he needs to cast doubt on Kenyon’s argument that the pottery beneath a stone building can safely date the period of construction of the building. Wright thinks instead that the pottery on top of a floor represents the last use of that particular building phase (destroyed in an earthquake or by an army or by fire, etc.), and that this last use can give an approximate date for when the new floor is laid.

It’s obvious that neither one of these methods can give us an absolutely certain date for the time of a building’s construction. Wright is surely correct that the pottery beneath a building can be from a much earlier time period than the building. Yet this is a problem, too, with material above a floor, since there is no a priori way of telling how long the interval is between the destruction of the building and when it is reused. In his essay, “Archaeological Fills and Strata” (Biblical Archaeologist, 25, 1962, 2, pp. 34.ff), Wright shows how difficult it can be to date buildings by means of fill. He points out that Yadin wanted to date the MB2c Temple at Shechem to the Late Bronze age based on the use of MB2c fill beneath the Fortress-Temple. “This sounds eminently reasonable,” says Wright, “except that it did not fit the facts of the situation at Shechem” (p. 35). He points out that the fill beneath a 3rd-2nd century house was LB and IA1, i.e., from a much earlier period:

“When we began to dig this fill, it was thought to be introducing us to a stratum. Yet the peculiar alternation of layers, most of which had the two periods of pottery mixed together, was troublesome. Finally we came to a layer of pure Late Bronze, when suddenly it gave way to another below which was almost pure Iron I A; and below that there was more mixture with a coin of Ptolemy I (ca. 300 B.C.)! From this experience we became skeptical of any generalizations regarding fills, and decided that each one would have to speak for itself.” (Wright, BA, p. 35.)

Wright concludes: “In the Shechem excavation we have decided on only one definite rule regarding fills: that each one is a special case….Hence it appears to us that the study of the nature of each fill requires a combination of stratigraphic and ceramic study. Neither stratigraphy nor ceramics can be made the ruling principle in itself.” (Ibid., p. 39.)

Wright appears to assume that Kenyon did not know all of this. However, even after Wright’s arguments were published, Kenyon did not accept the existence of Wright’s “phantom village.” Our view is that it should surely be up to the field archaeologist to weigh the situation at the relevant site and make dating determinations based on the total facts of the archaeological situation. Wright did not allow outside challenges to his fieldwork at Shechem—and rightly so—but one could also say the same thing of Kenyon. Why should she adopt the views of someone who had not been at the site? Should we place more confidence in an outside methodological argument, or on Kenyon’s own expertise in dating her finds?

It is the contention of the New Courville theory, that this methodological dispute is really a smokescreen for a much larger problem in Holy Land archaeology, and that is the dependence of pottery dating on what we regard as an overstretched Egyptian chronology. Thus, New Courville has no difficulty in accepting Kenyon’s dating for the 1st and 2nd phases at Samaria, and no difficulty in moving “10th century” indicia down to the 9th century, i.e., redescribing the pottery and archaeology as Omride rather than Solomonic. Conservative archaeologists fear doing this in that it would rob Solomon’s kingdom of any significant material and architecture. Since we place Solomon at the end of the Late Bronze Age, and greatly reduce the time of the Iron 1 period, this is not a problem for the New Courville theory.

5. LOW CHRONOLOGY

A full discussion of the Low Chronology of the Iron Age will be left to a subsequent discussion, but a summary of its basic concepts will be useful.

As noted above, when Kenyon reported her work at Samaria, it was soon realized that her Samaria 1 & 2 pottery was parallel to similar pottery hitherto dated to the 10th century. The Low Chronologists are those archaeologists who do not agree with Wright and others in their dispute with Kenyon. Remarkably, in 1990, the American Schools of Oriental Research opened its distinguished Bulletin to the thesis of the Low Chronology. Walter Rast, in an editorial, invited contributors to respond to G. J. Wightman’s essay, “The Myth of Solomon.” Among the contributions were those by Israel Finkelstein (pro) and William Dever (con).

The debate involved in part a discussion of the defense system of the city of Gezer, and its proper dating, and included, as Rast says, “more far-reaching matters such as the interpretation of pottery styles, cross-comparisons of stratification and architecture at sites with key material for these two centuries [10th & 9th BC], and the role of the military activities of the Egyptian pharaoh Sheshonq I (Shishak [sic]) in interpreting archaeological remains at a number of sites linked to this period.” (BASOR, 1990, 277/278, p. 1.)

What he means is that if the Low Chronology is right, then the archaeology and pottery styles now regarded as “Solomonic” would have to be regarded instead as Omride or Ahabic, and furthermore, that Shoshenq 1 can no longer be considered the biblical Shishak. It is significant that David Ussishkin, in the same BASOR issue, pointed out that the fragment of Shoshenq 1 was not found in a stratigraphically relevant area. He says:

“The beginning of Fisher’s excavations was marked by the discovery of a fragment of a large stone stele of Pharaoh Shoshenq I (ca. 945-924 B.C. [sic]), obviously erected during his campaign to Israel and Judah ca. 925 B.C. [sic]. The fragment was found in one of Schumacher’s dumps, near the eastern edge of the mound [of Megiddo]….” (Ussishkin, “Notes on Megiddo, Gezer, Ashdod, and Tel Batash in the Tenth to Ninth Centuries B.C.,” BASOR, 1990, 277.278, p. 71.)

He quotes the excavator, Fisher, who in 1929, said, “The fragment of the Shishak [sic] stela…came from one of the old surface dump heaps near the eastern edge.” Ussishkin goes on, “According to Guy [excavator writing in 1931] the fragment ‘was found by Fisher’s foreman in the rubbish heap’ beside ‘a minor trench of Schumacher’….[T]he limestone stele had been broken into building blocks and the uncovered fragment was one of them. It seems to have been incorporated in secondary use in one of the buildings that Schumacher had partly uncovered, and to have been removed by his workmen from the trench to the dump.” (Idem.)

The significance of this was not lost on Rast:

“Ussishkin’s conclusions about the stele of Shishak [sic] found at Megiddo, if accepted, would place under question the only piece of written evidence from Palestine supporting a connection between the archaeological data and Shishak.” (BASOR, 277/278, pp. 1-2.)

Many alternative chronologists have pointed out that the identification of Shishak with 22nd Dynasty Pharaoh, Shoshenq 1, is a major foundation for conventional chronology. This identification goes back to Champollion, who in 1828 read the inscriptions on the Bubastite Portal at Karnak as referring to Shoshenq 1. Thereupon, the Frenchman claimed that Shoshenq 1 was none other than the biblical Shishak.

There is no archaeological data to support this conclusion, however, and the possibility that Shishak may have been another Pharaoh (Merneptah under New Courville) rules out any a priori identification of Shoshenq 1 with the Shishak of the Bible. As it stands, the lack of a stratigraphically safe dating of the Shoshenq stele means that there is no support for conventional chronology from this source, and it does not stand in the way of the Low Chronology’s redating of “10th century” archaeological and pottery types down to the 9th century.

6. REDATING THE PERIODS OF SAMARIA

In our opinion, Wright’s basic distinction between building periods and pottery periods is correct, but his delineation of them is not helpful. In fact, it’s very confusing. This is because Wright distinguished the pottery from the building periods, but he kept the same numbering (i.e., Pottery Period 1, Building Period 1, Pottery Period 2, Building Period 2, and so on). However, this fails to convey that Pottery Periods 1 & 2 are virtually the same pottery, and that Pottery Periods 4 & 5/6, though not the same, are also very close in ceramic style.

In order to take this into account, the suggestion is here offered to adopt Wright’s idea of distinguishing pottery and building periods, but to do so with a new terminology in place of Wright’s. A new terminology will give a better understanding of the relation between building and pottery periods, but will also prevent confusion between Wright’s interpretation of the archaeology of Samaria, and our own.

The term “ceramic phase” will be used in place of “pottery period”—and to distinguish them further, ordinal numbering (first, second, third, etc.) will be used in place of cardinal numbering (1, 2, 3, etc.). The following is a table of the ceramic phases in comparison with Wright’s pottery periods and Kenyon’s building periods:

| Kenyon | Wright | New Courville | |

| Building Pottery | Building Pottery | Building Ceramic | |

| EB | |||

| Shemer Family | 1-2 | ||

| Omri | I 1 | I 3 | I 1st |

| Ahab | II 2 | I 3 | II 1st |

| Jehu | III 3 | II 3 | 2nd |

| Jeroboam 2 | IV 4 | III 4 | III 2nd |

| to Sargon 2 | V 5-6 | IV-VI 5-6 | IV 3rd |

| to Nbcdnzzr 2 | V-VI 3rd |

As can be seen from the chart, there are only three real ceramic phases for the history of Samaria from Omri to Nebuchadnezzar 2. The fill used for the first two building periods was made up of the same basic pottery type, and hence we designate it as the 1st Ceramic Phase. Kenyon held that the similarity in pottery style for both building periods indicated a short time span between them—and this is consistent with the view that Omri inaugurated Building Period 1 and that Ahab inaugurated Building Period 2.

Wright says that the pottery from his Pottery Period 3 is “sufficiently different” from Pottery Periods 1 & 2 as to suggest a “sizeable interval of separation” from the latter. (Wright, p. 19.) This interval under New Courville is the time between Ahab’s reign and the beginning years of Jeroboam 2’s reign.

During this interval, the 1st Ceramic Phase under Omri and Ahab gradually gave way to the 2nd Ceramic Phase. The pottery of this second phase made up the fill for Building Period 3. The fourth building period represents the city that was eventually captured by Sargon 2. This building period saw only limited repair work in the courtyard building and a portion of the casemate wall. (Wright, p. 19.) During this phase of the city, the 2nd Ceramic Phase gradually gave way to the 3rd Ceramic Phase. The 3rd Ceramic Phase was in use during Samaria 4 when the city was captured by Sargon (not destroyed as Wright thinks), and it continued on as the last ceramic phase in use at the time when the 5/6th city was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar 2.

In the Shechem essay it was argued that the end of Shechem 9b correlates to the end of Samaria Building Period 2. Excavations at Shechem 9b yielded evidence that it had been destroyed by an earthquake, and this was interpreted as the level destroyed by the earthquake of Uzziah’s day. Since the end of Samaria 2 correlates to the end of Shechem 9b, this means the destruction of Samaria 2 could well have resulted from the same earthquake. Wright describes the destruction of Samaria 2 (which required a rebuilding under Samaria 3):

“In Period III a wholesale rebuilding of the structure adjacent to the northern enclosure walls, and also of the royal palace to the west, suggests that a catastrophe had brought Period II to a close….The stones employed for this purpose were re-used from earlier buildings; some still had plaster adhering to them. The date for this period is given as ca. 840-800 B.C. [sic].” (BASOR, 155, pp. 18-19.)

The 2nd ceramic phase in use at the time of the earthquake (as we are interpreting it) was used as fill for Jeroboam’s rebuilding operations—i.e., Building Period 3. From this point on until the destruction of Samaria, the 3rd Ceramic Phase developed. This is enough time to allow for Wright’s view that the difference between Pottery Periods 3 & 4 was of a “similar interval” to the difference between Pottery Periods 2 & 3. The time would be from 783 BC to 721 BC—62 years, the date of Sargon’s capture of the city.

Note: The idea that Sargon 2 destroyed Samaria is merely a supposition—and is based on a confusion of the archaeology of the Assyrians with the archaeology of the Neo-Babylonians, as was argued in our Shechem essay. There is little evidence, however, that the Assyrians destroyed Samaria; instead, they repopulated captured cities with people of their own choosing; or gave the cities to their allies. Thus, we cannot follow Wright in placing the destruction levels of Samaria 5 & 6 at the time of Sargon 2.

7. THE DATE OF UZZIAH’S EARTHQUAKE

According to Wright, the Ostraca House of Samaria correlates with Building Period 3. Wright says, “They belong in Building Period III from the first half of the eighth century.” (“Samaria,” Biblical Archaeologist, 1959, 3, p. 71, 78; cf also BA, 1957, pp. 158-9.) In his article, “The Samaria Ostraca: An Early Witness to Hebrew Writing,” Ivan T. Kaufman points out that the ostraca were not found on the floor of the Ostraca House but were found in the fill underlying it.

“The ostraca have been associated with a building called the Ostraca House….In my earlier study, I concluded that the ostraca were found in the fill which made up the floor of the long corridors behind the Ostraca House proper [citing, The Samaria Ostraca, dissertation, 1966:107]….This evidence refutes the notion that the ostraca were found on the floor of the Ostraca House complex as part of destruction debris.” (Biblical Archaeologist, Fall, 1982, p. 231.)

This was affirmed also by Anson F. Rainey, who said, “By using Reisner’s notebooks Kaufman has succeeded admirably in locating the exact findspots of the clusters of ostraca; all of them were within a fill below the floor level of the so-called ‘Ostraca House’….” (“Toward A Precise Date for the Samaria Ostraca,” BASOR, 1988, 272, p. 69.)

From this, we can infer that the ostraca were found in the fill of Building Period 3, and hence would correlate to our 2nd ceramic phase. If the 2nd ceramic phase was brought to an end by Uzziah’s earthquake, as we have argued, then it may be possible to link the ostraca to the earthquake. This is of considerable importance, because one thing we know about these ostraca is that they can be dated. Some of the ostraca are dated to the 15th year of an unnamed king, and some are dated to the 9th or 10th years of an unnamed king. The lack of any intervening years, among other things, led Kaufman and Rainey to regard these years as belonging to a single date of two co-regent kings, rather than to different dates of one king (cf., Kaufman, p. 235.) We cannot go into great detail about it, but the conclusion of Anson Rainey’s discussion of these finds is that they should be dated to 784/783 BC, during the time of Jeroboam 2.

“Jehoash began his reign in 798 (accession year reckoning) which brings his 15th year down to 783/782. Jeroboam II began his reign as coregent (without accession year) in 793 B.C. which means that his 9th and 10th years fell in 785/784 and 784/783 respectively….So there is a cluster of years from 785 to 782 B.C. with a central cluster from 784 to 783. It is during the years of this latter cluster that we now suggest the date for the inscribing of the year dates on the Samaria ostraca.” (Ibid., pp. 70-71.)

Thus, the ostraca are something like a stopped watch during an accident or explosion. Just as the watch gives the actual time of the accident or explosion, so the ostraca provide, on our theory, the actual year of the earthquake, c. 783 BC.

Courville himself dated the earthquake of Uzziah’s day to 751-750 B.C, based on a legend reported by Josephus. (Exodus Problem, 2:122-23.) The prophet Zechariah is quoted as a source indicating the severity of the earthquake:

“Then you shall flee through My mountain valley, for the mountain valley shall reach to Azal. Yes, you shall flee as you fled from the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah. Thus the LORD my God will come, and all the saints with You.” (Zech. 14:5; NKJ)

Josephus claimed that the earthquake was God’s judgment on Uzziah for his attempt to burn incense to the Lord, a rite reserved to the priests alone (2 Chr. 26:17-18). Josephus speaks of a rent made in the temple, and bright sunlight falling on the king’s face, as he was seized with leprosy. The king’s son, Jotham, perforce had to become the acting king, c 750 B.C., while Uzziah remained in a quarantined house for the rest of his reign. Courville concludes from this that the earthquake must have happened in the year 751-750 B.C.

Of course, this would only be the correct date if the earthquake could be associated with the judgment upon Uzziah, that is, only if Josephus’s account could be proven true that the earthquake occurred at the same time that Uzziah was stricken with leprosy. While the Zechariah quotation is suggestive, it does not specifically associate the earthquake with God’s judgment on the king, and we cannot follow either Josephus or Courville’s attempts at a correlation without further evidence.

Courville goes on to correlate this earthquake with other catastrophic events, such as the eruption of Thera, etc. (EP, 2: 124ff.) He can only do this because he brings the late, Late Bronze age down to the time of Uzziah, a view we must reject. Courville was too much in thrall to Velikovsky to free his mind from the latter’s impossible chronology for late Israelite history.

If we adopt the New Courville view, however, the placement of Uzziah’s earthquake at the end of Samaria 2 can be correlated with a wave of destruction that hit the Holy Land at this stratigraphic level. Since conventional chronology (erroneously) places this level at the time of Shishak (923 B.C.), and correlates it with Pharaoh Shoshenq’s campaign through the Holy Land, the destruction is regarded as the result of the latter’s incursion. However, our view is that these destructions should be correlated to the earthquake of Uzziah’s day, or rather, to the days of Jeroboam 2. Speaking of these destructions, Amihai Mazar says,

“Some of the numerous destructions of this period can be ascribed to Shishak’s [sic] campaign: Timnah (Tel Batash, Stratum IV), Gezer (Stratum VIII), Tell el-Mazar, Tell el-Hama, Tell el Sa`idiyeh (these last three sites in the Jordan Valley), Megiddo (Stratum IVB-VA), Tell Abu Hawam (Stratum III), Tel Mevorakh (Stratum VII), Tel Michal, and Tell Qasile (Stratum VIII). Megiddo was apparently only partially destroyed—as the six-chamber gate seems to have continued in use in the following period, and Shishak [sic] erected a victory stele there, a fragment of which was found in the excavations.” (Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, p. 298.)

As we’ve pointed out, however, this stele was found in a dump rather than in a relevant stratigraphic context, so the evidence from Shechem 9b, correlated to all of the above destruction levels, is consistent with an earthquake during the time of Jeroboam 2, dated to c. 783 B.C. It is hoped that further excavations at these sites will focus on the question of earthquake damage rather than on “Shishak’s” supposed destruction of sites during this archaeological level.

8. THE OSORKON JAR

An important synchronism for conventional chronology is the fragment of an alabaster jar bearing the name of an Egyptian pharaoh. Andre Parrot says:

“The Harvard University expedition had found some ivory fragments, all lying on the floor of the court of Ahab’s palace. One of them was picked up along with a fragment of alabaster inscribed with the name of the Pharaoh Osorkon II (870-847 [sic]). This gave a valuable synchronism with the reign of Ahab (869-850).” (Samaria: The Capital of the Kingdom of Israel, 1958, pp. 63-64.)

In addition to the ivories, a collection of ostraca was found between the palace of Omri and the western casemate wall. This, too, was synchronized with the Osorkon 2 fragment:

“In the first flush of the discovery, and relying on the presence in this sector of the jar-fragment bearing the name of the Pharaoh Osorkon II (870-874 [sic]), the conclusion was reached that the ostraca belonged to the reign of Ahab….The resumption of excavation by Crowfoot’s expedition…necessitated the lowering of the date of the ostraca, so that it is now generally agreed that they should be assigned to the period of Jeroboam (786-746 B.C.).” (Ibid., p. 77.)

Why wasn’t the Osorkon 2 jar also downdated? If it was used to date the ivories and the ostraca, why wouldn’t their redating to a later time require the Osorkon fragment to be redated to a later time? The reason is simple: the fragment is where it is supposed to be on the basis of conventional chronology. Thus, moving the ostraca downward in time, but assigning the Osorkon fragment to the time of Ahab, is ultimately based on the assumed correctness of conventional chronology.

The Osorkon fragment and ivories were found in the Ahab court north of the Ostraca House (where the ostraca were found). It could be argued in support of conventional chronology that since the ostraca were not found in the same location as the jar and ivories, their downdating would not require the Osorkon jar to be downdated.

“The southern wall of the Osorkon House was built in part over the foundations of the north wall of rooms 406, 407, and 408. The foundations of the assumed northern part of the Ostraca House must have been destroyed previous to the construction of the Osorkon House.” (Reisner, Fisher, & Lyon, Harvard Excavations at Samaria, 1924, Vol. I, p. 131; my emphasis.)

Immanuel Velikovsky was apparently the first to call attention to the Harvard excavation report on the relation between the Ostraca House and the Osorkon House, but he did so in the context of questioning the very science of archaeology itself, which is why archaeologists did not take him seriously at the time (cf. Ramses II and His Times, p. 246). However, the basic problem he describes must be taken seriously. Ron Tappy, in his work on Samaria, concluded that there was no stratigraphically safe way to correlate the Osorkon jar to the time of Ahab or to anyone else. He summarizes Reisner’s findings:

“Reisner concluded that ‘the southern wall of the Osorkon House must have been built over the northern wall of the Ostraca House, as preserved,’ though no direct stratigraphic connection existed between the two buildings. He dated the floor level of the Osorkon House…by means of an Osorkon vase and ivory uraeus found in the makeup beneath the surface. These items [says Reisner] ‘were either in place when the Osorkon House was built or were in the earth used in leveling the floor of that house. The layer in which they were found contained only Israelite objects, mostly potsherds, and appeared to be the same layer of surface debris as that which contained the Israelite ostraca.’” (The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria, Vol 2, The Eighth Century BCE, pp. 501-02.)

For Reisner, the Osorkon jar was found in material used as fill underneath the Osorkon House, thus dating its construction phase to at least the time of Osorkon 2 or after. As Reisner further claims, the Osorkon jar was in the same layer as the ostraca. However, Tappy points out that the jar may have been an heirloom, and also that Reisner “could not establish a direct stratigraphic connection between the layer that contained [the jar and uraeus] and the one that yielded the ostraca.” (Idem.) Tappy concludes:

“Without new stratigraphic and ceramic data pertaining directly to these areas of concern, my opinion remains that neither the date of the Osorkon House nor of the Ostraca House can be established with certainty based on the reasoning presented in the official Harvard report.” (Idem.)

All that we can really tell is that the Osorkon House came after the Ostraca House. It may be possible, on the basis of Reisner’s conclusions, to date the Osorkon jar (and hence Osorkon 2) to Jeroboam 2’s reign. This would be the case because the ostraca have been downdated to the time of Jeroboam 2, and if the Osorkon jar comes after the ostraca, it would entail that Osorkon 2 should be downdated to the time during or after Jeroboam 2. Nevertheless, Tappy’s skepticism should be taken seriously. We will have to await further study of the archaeological situation at Samaria before attempting to date Osorkon 2 to any particular time period.

In conclusion, there is at present no archaeological way to fix the date of the Osorkon jar to the time of Ahab that doesn’t already assume the correctness of conventional chronology, and any appeal to such an alleged synchronism to support conventional chronology is just reasoning in a circle. Since the reign of Jeroboam 2 offers an alternative dating of the Osorkon jar, there can be no a priori use of the Osorkon jar for conventional dating purposes.

Finis

The first expedition distinguished three Israelite building phases: the palace from the time of Omri, the casemate wall and the storehouse from the reign of Ahab, and the buildings west of the casemate wall from the days of Jeroboam II. The Joint Expedition dug a stratigraphic section across the royal quarter. Early Bronze Age I pottery was found on the rock, but the site was not resettled until the Israelite period. Kenyon distinguished eight pre-Hellenistic building and ceramic periods, six of them belonging to the time between the foundation of the city in 876 BCE and its conquest in 721 BCE. This division was based on both architectural and ceramic considerations. According to Kenyon the building periods I-VI coincide with the ceramic periods I-VI, as shown here:

| Period | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Omri: construction of the inner wall and the palace. |

| II | Ahab: construction of the casemate wall and probably also of the east gate. |

| III | Jehu and others: repair of the casemate wall, rebuilding of earlier structures, erection of new buildings. |

| IV | Time of Jeroboam II and others: repair of the casemate wall, alterations in existing buildings, and construction of new ones, probably also of the storehouse. |

| V-VI | Changes and repairs: burned layer attributed to the conquest of Samaria in 721 BCE. |

These conclusions were disputed, however, by W. F. Albright, Y. Aharoni, R. Amiran, G. E. Wright and others, who maintain that the pottery from periods I-II found in the fills of structures I-II predates these buildings. On the grounds of a typological comparison with pottery from other excavations, they date it earlier, to the tenth and beginning of the ninth centuries BCE. In their opinion the pottery attests to the fact that a small settlement existed on the site prior to the foundation of the city of Samaria.

Kenyon did not overlook this problem. Although she noted the discovery of two walls covered by the floors of buildings from period I, when discussing the pottery she stated that there was no trace of occupation from the beginning of the Early Bronze Age until the time of Omri.

Avigad shared the view of those who claim that pottery periods I-II precede building periods I-II and that the pottery of period III, which is richer and more varied than the preceding examples - parallels building periods I-II. Wright has also suggested a correction in the chronology of the walls. In his opinion, Omri, who resided in Samaria for only six years, could not have succeeded in building the first wall and the palace in such a short time. It is difficult as well to assume, according to Wright, that Ahab could have erected a fortification as extensive as the casemate wall during the twenty-two years of his reign. Wright therefore considers that Omri only began the construction of the first wall and that Ahab completed it, whereas Jehu, the founder of the next dynasty, built the casemate wall.

Wright's contentions are not acceptable to this writer. In Avigad's opinion it is highly improbable that Omri would have established his residence in a city that was not walled and in which there were no quarters suitable for a king. In all probability, he began the fortifications of the hill and the building of his palace while still living in his first capital, Tirzah. He would have transferred his capital to Samaria only after the site had been prepared - that is, after the main buildings had been wholly or nearly finished. He could certainly have completed the inner wall, which is a single wall only 1.6 m thick. The building of the casemate wall, on the other hand - for which the summit of the hill had to be widened by an artificial fill - was indeed a major undertaking. It required considerable time and means, as well as the vision of a great builder .It was certainly possible to complete it in the twenty-two years of Ahab's reign. In fact, the work was finished in an even shorter time, because during Ahab's reign Samaria withstood the siege of the Arameans only by virtue of its strong fortifications. (It should be noted that this discussion refers only to the fortifications of the acropolis; in times of emergency, the acropolis could also shelter the inhabitants of the lower city, of whose walls almost nothing is known.) Ahab, who married Jezebel, the daughter of the king of Tyre, certainly received ample assistance from the Phoenicians for this extensive construction project. During his reign, prosperity prevailed in the kingdom of Israel, and the Bible relates that Ahab was a builder of cities and palaces. Archaeological finds from sites other than Samaria also attest that Ahab was a great builder. He erected strong fortifications at Hazor and at Megiddo. At the latter site he probably also built the large stables, an assumption borne out by an Assyrian source recording the considerable number of war chariots that stood at Ahab's disposal. It cannot, therefore, be conceived that in his own capital, Samaria, he would have been satisfied with merely completing the construction of the unpretentious "inner wall" begun by his father.

For these reasons, it is difficult to attribute the construction of the casemate wall to Jehu. Even though Jehu founded a new dynasty, put an end to the cult of Baal, and won the confidence of the prophets, his reign does not seem to have been propitious for such a large building project as this. During his reign, the kingdom of Israel suffered political defeats and lost extensive territory. Jehu was the first Israelite king to pay heavy tribute to the Assyrians. Commercial relations with Tyre were broken off with the killing of Jezebel, and it is hardly likely that the Phoenicians would have nevertheless supplied him with aid to build fortifications. Furthermore, the Bible does not attribute any building activity to Jehu.

Therefore, those archaeologists seem to be correct who have ascribed the building of the casemate wall to Ahab and only its repairs to Jehu and his successors. The following chronological table summarizes the different views on the dating and the correlations between the building and ceramic periods at Samaria, up to its conquest in 722 BCE.

Stratigraphic Comparisons for the Biblical Periods in Samaria

Stratigraphic Comparisons for the Biblical Periods in SamariaStern et al (1993)

Initial excavations of this site were performed by Harvard University without the aid of modern excavation or recording techniques and without a valid chronology of Late Roman Byzantine ceramics (Russell, 1980). Reisner, Fischer, and Lyon (1924: 218) report the following which may indicate earthquake damage:

Restoration - During the Severan period the Basilica and the Forum were entirely reconstructed. The building, like those on the summit, had apparently been in ruins. Many of the columns had been overthrown, and the pedestals carried away.Gibson (2014) reports that Samaria-Sebaste was destroyed during the First Jewish War (66–73 CE), "but was rebuilt and gained the status of a Roman colony from the hands of Septimus Severus in 200 CE. By the time that Christianity became the dominant religion, Sebaste was already deteriorating and after the Arab conquest in the first half of the seventh century CE it was left in ruins". This suggests that the Severan period referred to by Reisner, Fischer, and Lyon (1924) could have lasted from 200 CE until sometime before the middle of the 7th century CE.

Russell (1980) reports that later excavations by Crowfoot, Kenyon, and Sukenik (1966:137-38) found evidence of destruction and subsequent rebuilding in a large house found in the eastern insula. Crowfoot et. al. (1966) described the evidence as follows :

No portion of the walls above ground level survived. The foundations show at least two periods. some badly built walls with very rubbly building being added to the better built earlier ones. Nearly all the earlier ones seem to have been partially rebuilt in the worse style, with two or three courses of rubble on the top of their solidly built foundations. This would indicate that the original building had been destroyed to ground level, possibly by an earthquakeAccording to Russell (1980), Crowfoot, Kenyon, and Sukenik (1966) also suggested that the Basilica of the site might have been converted into a cathedral during the 4th century CE (Crowfoot, Kenyon, and Sukenik, 1966: 37).

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls ? | Samaria |

“Bricks have fallen— We’ll rebuild with dressed stone; Sycamores have been felled— We’ll grow cedars instead!” לְבֵנִ֥ים נָפָ֖לוּ וְגָזִ֣ית נִבְנֶ֑ה שִׁקְמִ֣ים גֻּדָּ֔עוּ וַאֲרָזִ֖ים נַחֲלִֽיף So GOD let the enemies of Rezin Triumph over it And stirred up its foes— אֲרָ֣ם מִקֶּ֗דֶם וּפְלִשְׁתִּים֙ מֵאָח֔וֹר וַיֹּאכְל֥וּ אֶת־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל בְּכׇל־פֶּ֑ה בְּכׇל־זֹאת֙ לֹא־שָׁ֣ב אַפּ֔וֹ וְע֖וֹד יָד֥וֹ נְטוּיָֽה" - Isaiah 9:9,10 possibly referring to seismic damage. |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | the original building had been destroyed to ground level, possibly by an earthquake- Crowfoot, Kenyon, and Sukenik (1966:137-38) |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls ? | Samaria |

“Bricks have fallen— We’ll rebuild with dressed stone; Sycamores have been felled— We’ll grow cedars instead!” לְבֵנִ֥ים נָפָ֖לוּ וְגָזִ֣ית נִבְנֶ֑ה שִׁקְמִ֣ים גֻּדָּ֔עוּ וַאֲרָזִ֖ים נַחֲלִֽיף So GOD let the enemies of Rezin Triumph over it And stirred up its foes— אֲרָ֣ם מִקֶּ֗דֶם וּפְלִשְׁתִּים֙ מֵאָח֔וֹר וַיֹּאכְל֥וּ אֶת־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל בְּכׇל־פֶּ֑ה בְּכׇל־זֹאת֙ לֹא־שָׁ֣ב אַפּ֔וֹ וְע֖וֹד יָד֥וֹ נְטוּיָֽה" - Isaiah 9:9,10 possibly referring to seismic damage. |

VIII+ |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | the original building had been destroyed to ground level, possibly by an earthquake- Crowfoot, Kenyon, and Sukenik (1966:137-38) |

VIII+ |

Austin, S. A., et al. (2000) "Amos’s Earthquake:

An Extraordinary Middle East Seismic Event of

750 B.C." International Geology Review 42(7):

657–671

Ben-Tor, A. and R. Bonfil (1997)

Hazor V: An Account of the Fifth

Season of Excavations, 1968,

Israel Exploration Society, The

Hebrew University of Jerusalem

– can be borrowed with a free

archive.org account

Blenkinsopp, J. (2000) Isaiah 1–39: A New Translation

with Introduction and Commentary, Anchor Bible 19,

New York: Doubleday, p. 212.

– can be borrowed with a free

archive.org account

Childs, B. S. (2001) Isaiah, Old Testament Library,

Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Crisler, V. (2004) The Archaeology

of Samaria (rough draft)

Finkelstein, I. (2013) The Forgotten

Kingdom: The Archaeology and History of

Northern Israel, Atlanta

Gibson, S. (2014) "A Visitor at Samaria

and Sebaste." In B. Wagemakers (ed.),

Archaeology in the Land of ‘Tells and

Ruins, Oxford: 61–72

Goldingay, J. (2012) Isaiah, Understanding the Bible

Commentary Series, Grand Rapids: Baker Books.

Roberts, J. J. M. (2015) The First Isaiah: A Commentary,

Hermeneia, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, p. 161.

– can be borrowed with a free

archive.org account

Russell, K. W. (1980) "The Earthquake

of May 19, A.D. 363." Bulletin of the

American School of Oriental Research

238: 47–64

Tappy, R. (2014) "Israelite Samaria:

Head of Ephraim and Jerusalem’s Elder

Sister." In B. Wagemakers (ed.),

Archaeology in the Land of ‘Tells and

Ruins, Oxford: 61–72

Yadin, Y. (1958) Hazor I: An Account

of the First Season of Excavation, 1955

– can be borrowed with a free archive.org

account

Yadin, Y. and S. Angress (1960)

Hazor II: An Account of the Second

Season of Excavations, 1956,

Magnes Press, Hebrew University

– can be borrowed with a free

archive.org account

Yadin, Y. (1961) Hazor III–IV: An

Account of the Third and Fourth

Seasons of Excavations, 1957–1958

– can be borrowed with a free

archive.org account

Reisner, G. A., C. S. Fisher, and

D. G. Lyon (1924) Harvard

Excavations at Samaria, 1908–1910,

Harvard University Press - open acess at archive.org

Crowfoot, J. W., et al. (1942)

Samaria-Sebaste I: The Buildings

at Samaria, Dawsons of Pall Mall

Crowfoot, J. W. and G. M. Crowfoot

(1938) Early Ivories from Samaria

(Samaria-Sebaste II), London

Crowfoot, J. W., G. M. Crowfoot, and

K. M. Kenyon (1957)

The Objects of Samaria

(Samaria-Sebaste III), London

G. A. Reisner, C. S. Fisher, and D. G. Lyon, Harvard Excavations at Samaria ( 1908-

1910), 1-2, Cambridge, Mass. 1924

J. W. Crowfoot and G. M. Crowfoot, Early Ivories from Samaria

(Samaria-Sebaste 2), London 1938

J. W. Crowfoot, K. M. Kenyon, and E. L. Sukenik, The Buildings at

Samaria (Samaria-Sebaste 1), London 1942

J. W Crowfoot, G. M. Crowfoot, and K. M. Kenyon, The

Objects of Samaria (Samaria-Sebaste 3), London 1957.

W G. Masterman, PEQ 57 (1925), 25-30;

Y. Aharoni and R. Amiran,IEJ8 (1958), 171-184

W F. Albright, BASOR !50 (1958), 21-25

0. Tufnell,

PEQ 9! (1959), 90-105

G. E. Wright, BASOR !55 (1959), 13-29

K. M. Kenyon, BIAL 4 (1964), 143-

156

id,, Royal Cities of the Old Testament, New York 1971

P.R. Ackroyd, Archaeology and Old Testament

Study(ed. D. W Thomas), Oxford 1967, 343-354

F. Zayadine, ADAJ 12-13 (1967-1968), 77-80

id., RB

75 (1968), 562-585

id., BTS 121 (1970), 1-15

S.Page, VT!9 (1969), 483-484

K. R. Veenhof, Phoenix 15

(1969), 221-224

BTS 120-121 (1970)

184 (1976)

M. Avi-Yonah, Archaeology (Israel Pocket Library),

Jerusalem 1974, 182-185

Miriam Tadmor, IEJ24 (1974), 37-43

Y Shiloh, BASOR 222 (1976), 67-77;

G. Wallis, VT26 (1976), 480-496

R. Giveon, The Impact of Egypt on Canaan, Freiburg 1978, 34-44

M.

Mallowan, Archaeology in the Levant(K. M. Kenyon Fest.), Warminster 1978, 155-163

S.M. Paul, VT28

(1978), 358-359

Y. Yadin, Archaeology in the Levant, op. cit, 127-135

M. W. Prausnitz, Madrider

Beitrdge 8 (1982), 31-44

H. Tadmor, Jerusalem Cathedra 3 (1983), I-ll

J. Balensi, MdB 33 (1984), 53-

54

Weippert !988 (Ortsregister)

W G. Dever, BASOR 277-278 (1990), 121-130

L Finkelstein, ibid.,

109-119

N. Na'aman, Biblica 71 (1990), 206-225

L. E. Stager, BASOR 277-278 (1990), 93-107

J. H,

Hayes and J. K. Kuan, Biblica 72 (1991), 153-181

B. Becking, The Fall of Samaria: An Historical and

Archaeological Study, Leiden (in prep.).

W F. Albright, JPOS 5 (1925), 38-54

11 (1931), 241-251

D. Diringer, Le

Inscrizioni, Florence 1934,21-68 (with biblio.)

B. Maisler(Mazar),JPOS12(1948), 117-133

S. Moscati,