Tell Saidiyeh Archaeoseismic Site

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tell Saidiyeh | Arabic | |

| Tell Es-Sa'idiyeh | Arabic |

- from Pritchard (1965c)

1. AASOR, XXV-XXVIII (1951), 340 ff.

2. AASOR, VI (1926), 46.

3. Geographie, Vol. II, p. 448.

- from Tubb (1998:40-42)

The Pennsylvania excavations came to a close in 1967, with the war of that year, and were not subsequently resumed. In 1985, the author resumed excavations at Tell es-Sa'idiyeh on behalf of the British Museum, and one of the main objectives of the new campaign was to examine in detail the Early Bronze Age occupation of the Lower Tell.

Tell es-Sa'idiyeh, in common with many sites in northern Canaan, shows some degree of continuity from the Chalcolithic to the Early Bronze Age. A deep sounding placed towards the centre of the Lower Tell produced a small quantity of Chalcolithic pottery resting on bedrock and, directly above it, material which could be related to the first phase of the Early Bronze Age. The Early Bronze I settlement was clearly extensive. Remains of a city wall have been found at two locations on the perimeter of the mound where it appears as a well-constructed double defensive circuit with a passageway between — similar in many respects to the fortification system at Ta'anach mentioned above. The most fully excavated phase of the Early Bronze Age occupation at Sa'idiyeh belongs to the Early Bronze II period, which would date to between about 2900 and 2650 BC. Remains of this period were found in three main areas on the Lower Tell: towards the centre, on the south-west side and in an area which lies 30 m south of the central area. Altogether. four levels of Early Bronze Age occupation have been identified. The uppermost level is a squatter phase, named Stratum 11. Below Stratum 11, the more substantial mud-brick architecture of two previous phases, known as Strata 12 and 13, has been defined, and it is with these two phases that the following discussion is mainly concerned.

Stratum 12 was found to be associated with dense destruction debris (ashes, burnt mud-brick rubble, and charred timber), but both Strata 12 and 13 were apparently built on the same plan. In contrast to the continuity of the architecture of these phases the walls of the earliest occupation level, Stratum 14, where expcsed, appear to follow a different layout.

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from Petit & Kafafi (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location Map

Petit & Kafafi (2016) - Location Map from

Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Deir 'Alla region, based upon topographic map 1947

Van der Kooij (2006) - Jordan Valley Sites from

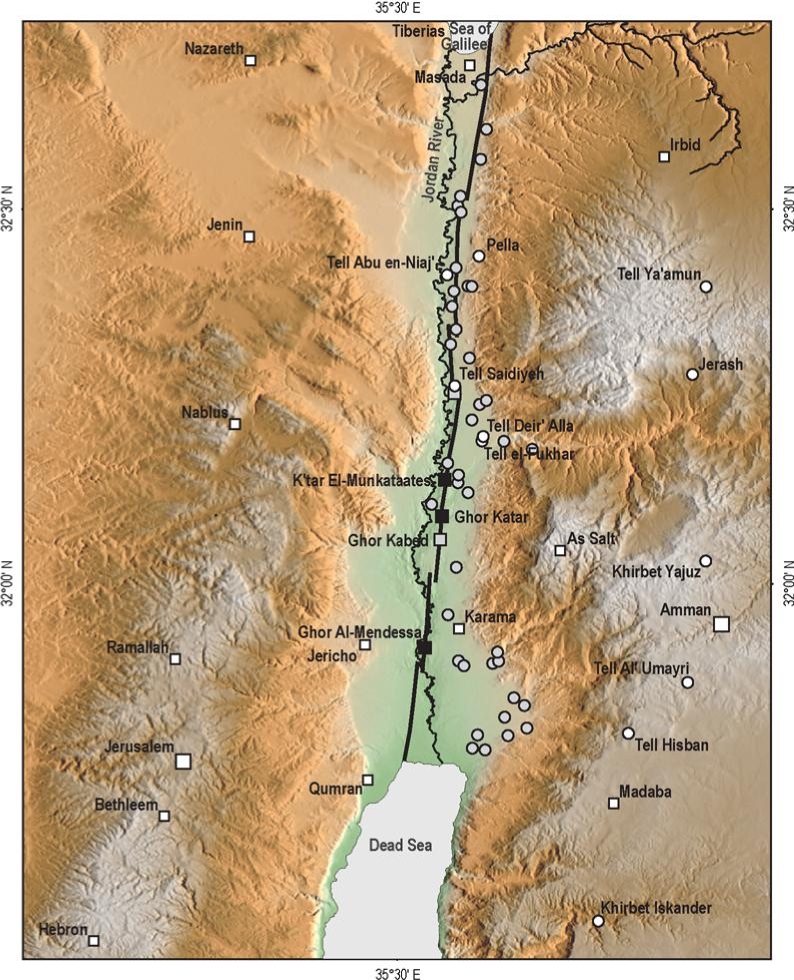

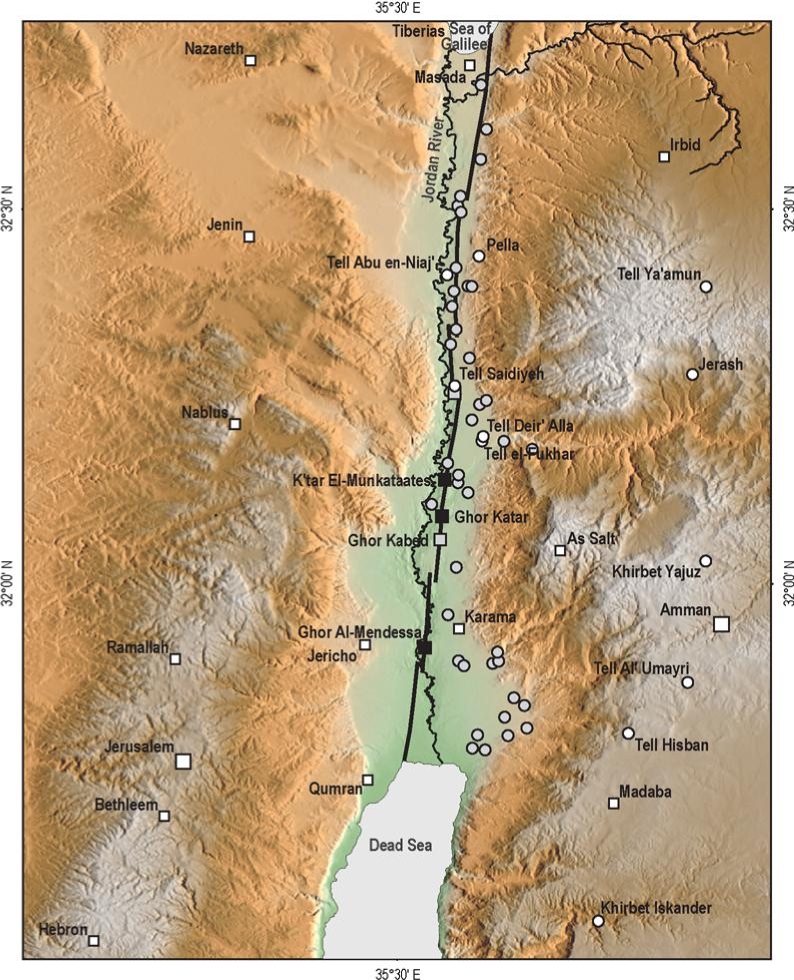

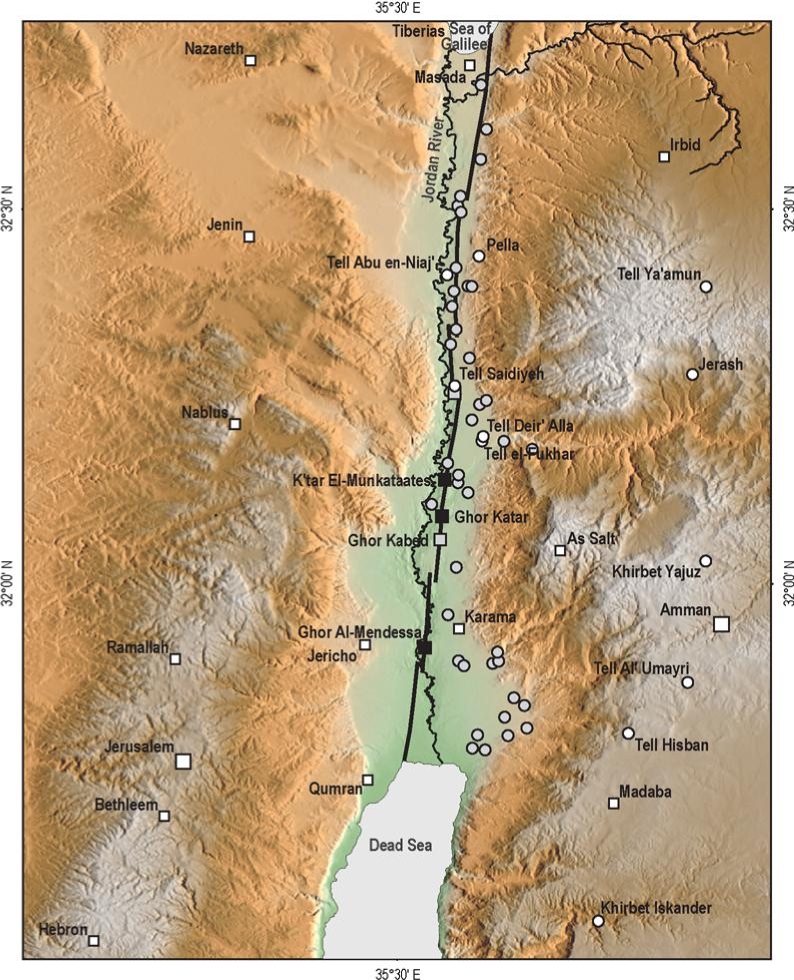

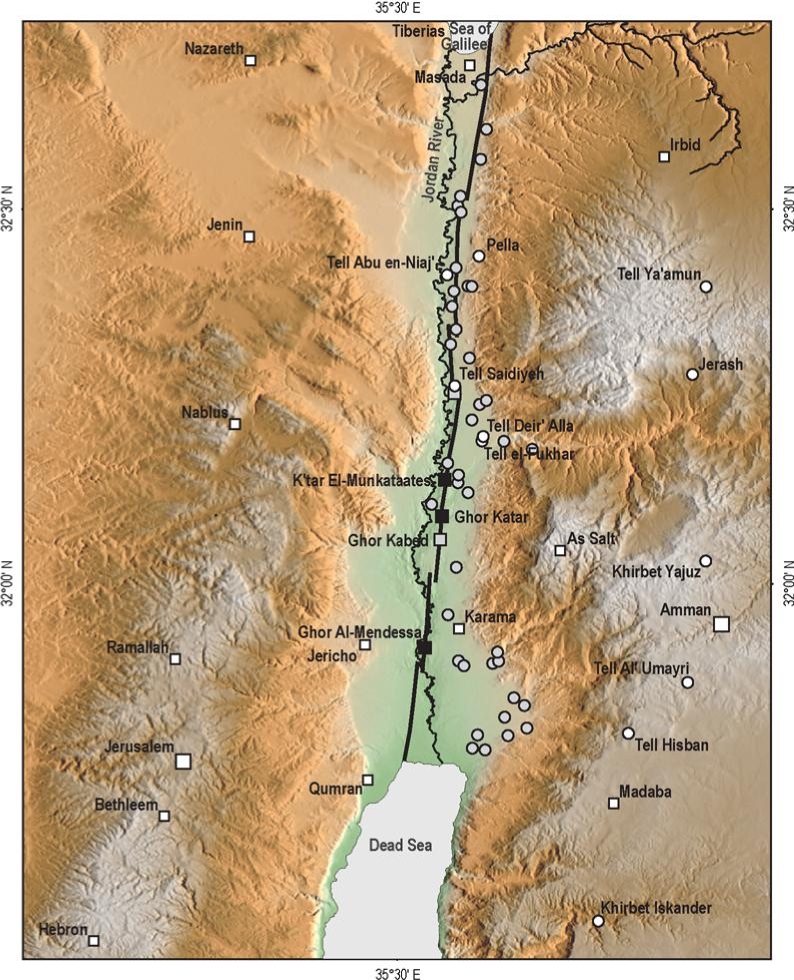

Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Archaeology of the Jordan Valley.

- White squares, main populated areas cited in historical documents

- white dots, archaeological sites visited and reappraised in this study

- gray dots are archaeological sites not studied here (lack of evidence and/or available literature) but of potential interest for future studies

- gray squares, paleoseismic sites

- black squares, geomorphological sites studied by Ferry et al. (2007)

Ferry et al. (2011)) - Fig. 2 Map of Iron Age I

sites in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Jordan Valley with Iron Age I sites mentioned in the thesis. The open circles are modern cities.

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 4.1 Map of sites

in central and northern Israel and Jordan from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Map of major archaeological and historical site in central and northern Israel and Jordan

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Fig. 1b Fault segments

in the Jordan Valley from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 1b

Figure 1b

Detailed map of the JVF (Jordan Valley Fault) segment between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea. The segment itself is organized as six 15-km to 30-km-long right-stepping sub segments limited by 2 km to 3 km wide transpressive relay zones. The active trace of the JVF (Jordan Valley Fault) continues for a further ~10 km northward into the Sea of Galilee (SG) and ~20 km southward into the northern Dead Sea (DS).

Ferry et al. (2011) - Fig. 3a Geomorphology of

the Jordan Valley fault from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 3a

Figure 3a

Geomorphology of the Jordan Valley fault

Central section of the JVF (Jordan Valley Fault) (see location on Fig. 1b), showing drainage (outlined) that is systematically left-laterally displaced at the passage of the fault. The active trace of the JVF (Jordan Valley Fault) is pointed out by the arrows.

Ferry et al (2011)

- Location Map from

Van der Kooij (2006)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of Deir 'Alla region, based upon topographic map 1947

Van der Kooij (2006) - Jordan Valley Sites from

Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Archaeology of the Jordan Valley.

- White squares, main populated areas cited in historical documents

- white dots, archaeological sites visited and reappraised in this study

- gray dots are archaeological sites not studied here (lack of evidence and/or available literature) but of potential interest for future studies

- gray squares, paleoseismic sites

- black squares, geomorphological sites studied by Ferry et al. (2007)

Ferry et al. (2011)) - Fig. 2 Map of Iron Age I

sites in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map of the Jordan Valley with Iron Age I sites mentioned in the thesis. The open circles are modern cities.

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 13 Map of Iron Age sites

in the Jordan Valley from Halbertsma (2019)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Map of Iron Age sites discussed in this chapter

(after Van der Steen 1999, 179).

Halbertsma (2019) - Fig. 4.1 Map of sites

in central and northern Israel and Jordan from Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Map of major archaeological and historical site in central and northern Israel and Jordan

Mazar et. al. (2020 v.1) - Fig. 1b Fault segments

in the Jordan Valley from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 1b

Figure 1b

Detailed map of the JVF (Jordan Valley Fault) segment between the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea. The segment itself is organized as six 15-km to 30-km-long right-stepping sub segments limited by 2 km to 3 km wide transpressive relay zones. The active trace of the JVF (Jordan Valley Fault) continues for a further ~10 km northward into the Sea of Galilee (SG) and ~20 km southward into the northern Dead Sea (DS).

Ferry et al. (2011) - Fig. 3a Geomorphology of

the Jordan Valley fault from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 3a

Figure 3a

Geomorphology of the Jordan Valley fault

Central section of the JVF (Jordan Valley Fault) (see location on Fig. 1b), showing drainage (outlined) that is systematically left-laterally displaced at the passage of the fault. The active trace of the JVF (Jordan Valley Fault) is pointed out by the arrows.

Ferry et al (2011)

- Fig. 8b Aerial View

showing Jordan Valley Fault and Tell from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 8b

Figure 8b

the satellite imagery shows the relationship between the active fault trace (thick line), the archaeological site (LT, lower tell; UT, upper tell), and geomorphology (white outline represents the extent of the microtopographic survey in Fig. 3b).

Ferry et al. (2011) - Tell Saidiyeh in Google Earth

- Fig. 1 Site plan with

excavation areas from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Contour Plan of the site showing excavation areas

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 1 Site plan with

survey grid from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Contour Plan of the site with survey grid showing positions of areas investigated in 1993

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 1 Site plan with

excavation areas from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Contour Plan of the site showing excavation areas

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 1 Site plan with

survey grid from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Contour Plan of the site with survey grid showing positions of areas investigated in 1993

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 2 Location plan for

areas on Upper Tell from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Location plan for areas on Upper Tell

Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 2 Location plan for

areas on Upper Tell from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Location plan for areas on Upper Tell

Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 2 Grids for Areas

AA and EE on Upper Tell from Tubb & Dorrell (1991)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the AA-EE linkage area showing configuration of trenches and their relationship to the main grid.

Tubb & Dorrell (1991) - Fig. 5 Composite plan

of stratum V Areas AA and EE on Upper Tell from Tubb & Dorrell (1991)

Figure 5

Figure 5

stratum V. Composite plan of Areas AA and EE (Grid squares 22, 23, 32, and 33) incorporating the southern part of Pritchard's exposure(taken from Pritchard 1986, fig. 79). Again, note that this plan has been simplified for the purposes of this report.

Tubb & Dorrell (1991)

- Fig. 2 Grids for Areas

AA and EE on Upper Tell from Tubb & Dorrell (1991)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the AA-EE linkage area showing configuration of trenches and their relationship to the main grid.

Tubb & Dorrell (1991) - Fig. 5 Composite plan

of stratum V Areas AA and EE on Upper Tell from Tubb & Dorrell (1991)

Figure 5

Figure 5

stratum V. Composite plan of Areas AA and EE (Grid squares 22, 23, 32, and 33) incorporating the southern part of Pritchard's exposure(taken from Pritchard 1986, fig. 79). Again, note that this plan has been simplified for the purposes of this report.

Tubb & Dorrell (1991)

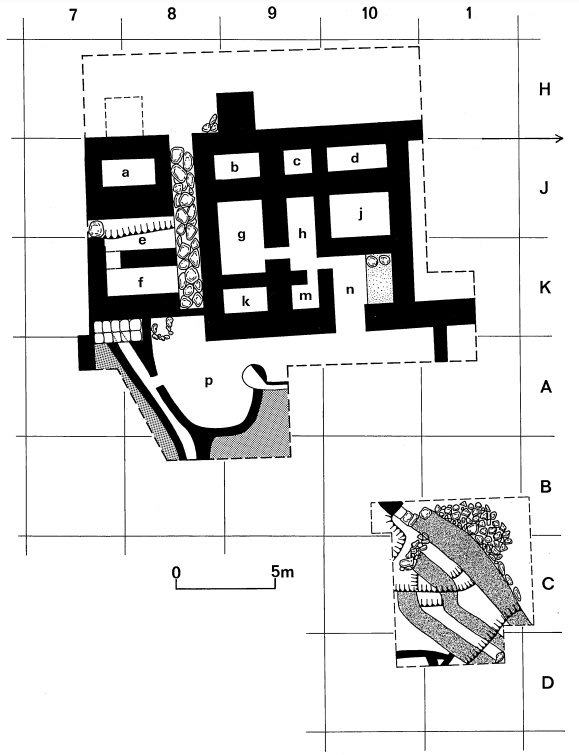

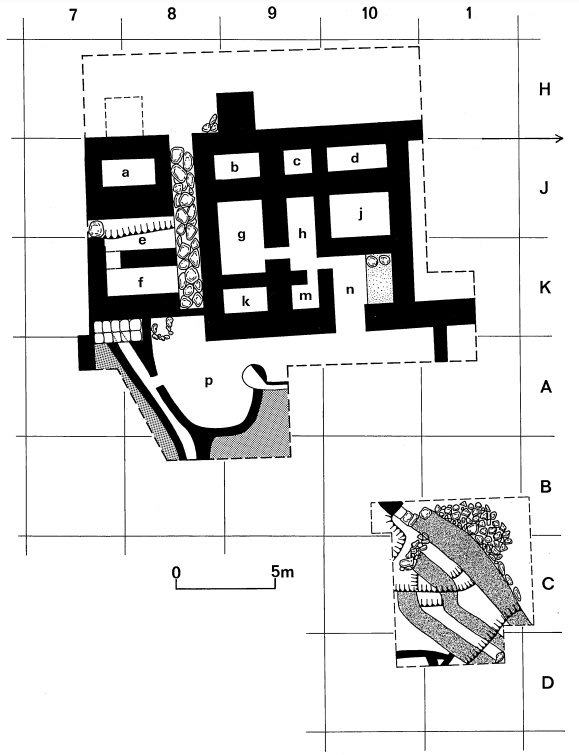

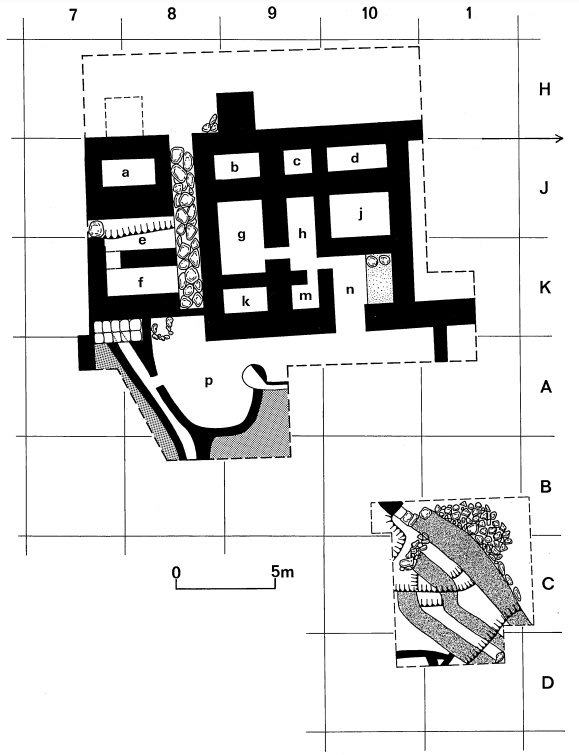

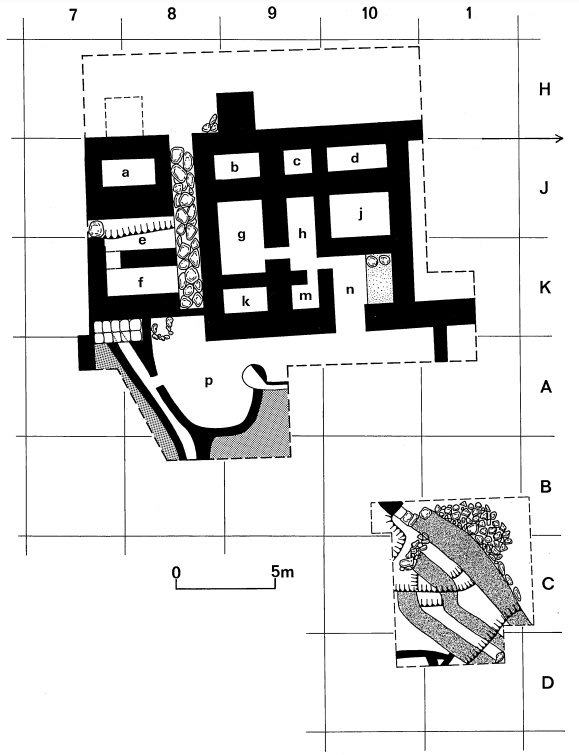

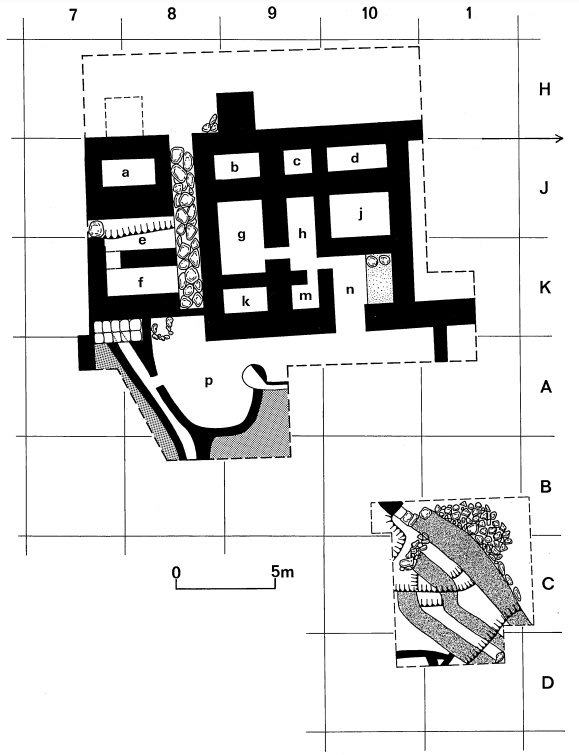

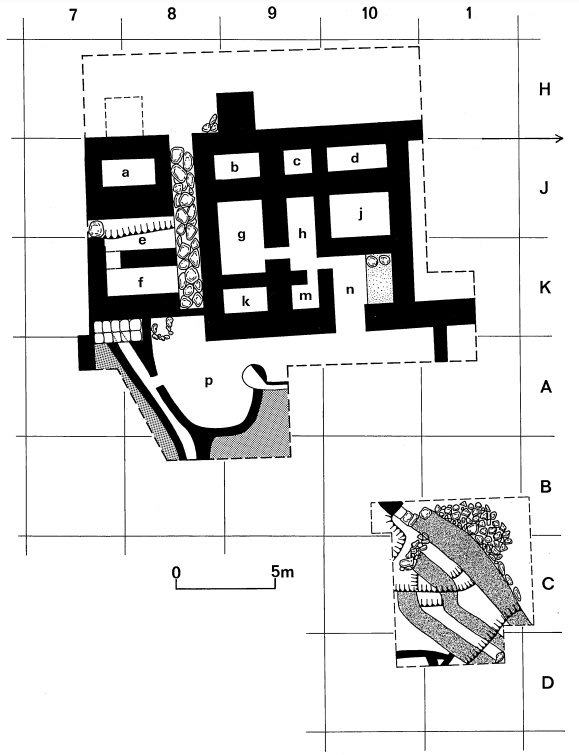

- Fig. 8 Plan of "Palace"

complex in Area EE in stratum XII from Tubb (1990)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Area EE, stratum XII: plan of "Palace" complex.

Tubb (1990)

- Fig. 8 Plan of "Palace"

complex in Area EE in stratum XII from Tubb (1990)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Area EE, stratum XII: plan of "Palace" complex.

Tubb (1990)

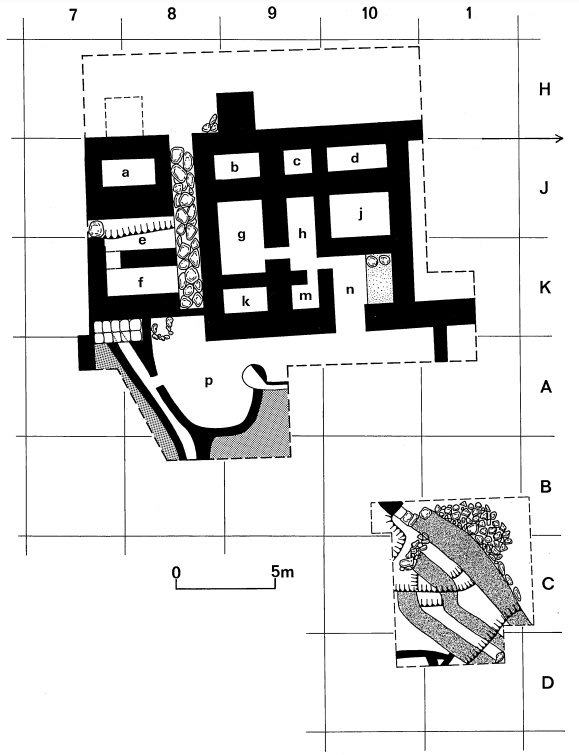

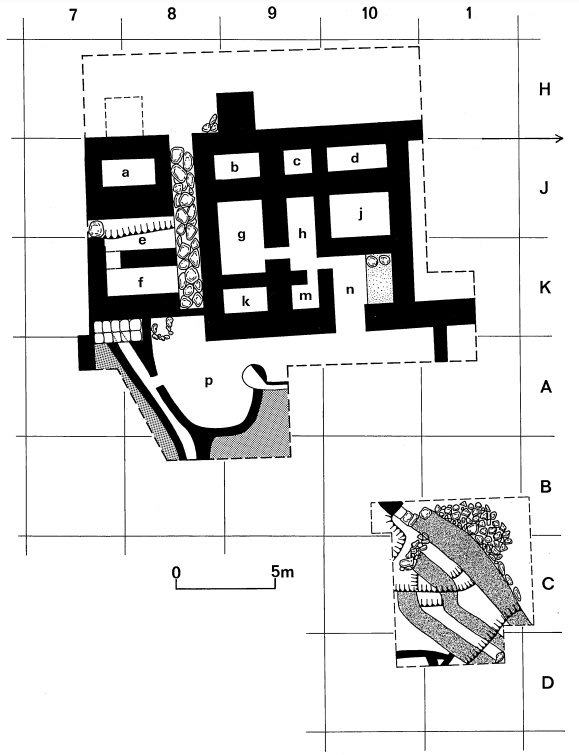

- Fig. 10 Plan of Western

Palace complex in Area EE from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Plan of the Western Palace complex in Area EE (Area 32-A/B-7/10, Area 33-H/K-7/10) and the 'Aqueduct' in AA goo (Area 32-B/D-IO, Area 23-B(D-l/2).

Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 10 Plan of Western

Palace complex in Area EE from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Plan of the Western Palace complex in Area EE (Area 32-A/B-7/10, Area 33-H/K-7/10) and the 'Aqueduct' in AA goo (Area 32-B/D-IO, Area 23-B(D-l/2).

Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 24 Stratum XII

alleyway and associated building in area KK from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

Figure 24

Figure 24

Area KK: Remains of Stratum XII alleyway and associated building and part of the underlying phase (Stratum XIII).

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

- Fig. 24 Stratum XII

alleyway and associated building in area KK from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

Figure 24

Figure 24

Area KK: Remains of Stratum XII alleyway and associated building and part of the underlying phase (Stratum XIII).

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

- Fig. 7 Plan of Stratum

VII bathroom in AA 1300 from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Plan of the Stratum VII bathroom in AA 1300 (Area 32-E-7).

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 8 Axonometric

reconstruction of Stratum VII bathroom from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Axonometric reconstruction of Stratum VII bathroom.

Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 7 Plan of Stratum

VII bathroom in AA 1300 from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Plan of the Stratum VII bathroom in AA 1300 (Area 32-E-7).

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 8 Axonometric

reconstruction of Stratum VII bathroom from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Axonometric reconstruction of Stratum VII bathroom.

Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 3 Plan of Hellenistic

building (Stratum IIA) in Area 32 from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Plan of Hellenistic building (Stratum IIA) in Area 32. The plan is a composite, drawing together Pritchard's work in E/G-8, the excavation of AA 700 in 1989(H/J-8), and the most recent results from AA 1300 (E/G-6/7).

Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 3 Plan of Hellenistic

building (Stratum IIA) in Area 32 from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Plan of Hellenistic building (Stratum IIA) in Area 32. The plan is a composite, drawing together Pritchard's work in E/G-8, the excavation of AA 700 in 1989(H/J-8), and the most recent results from AA 1300 (E/G-6/7).

Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 2 Plan of the

Persian period Residency in Area 31 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the Persian period Residency in Area 31 (taken from Pritchard 1985, fig. 185) showing position of the 1993 sounding.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 2 Plan of the

Persian period Residency in Area 31 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the Persian period Residency in Area 31 (taken from Pritchard 1985, fig. 185) showing position of the 1993 sounding.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 8 Plan of Field I

from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Overall plan of Field I showing the possible relationship between the Early Bronze Age architecture of Area BB 100-600, and that of Areas BB 700/DD.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 3 Plan of Field I

from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Overall plan of Field I (Lower Tell) showing architecture relating to the Early Bronze Age complex(es) in Areas BB and DD (revised since 1995).

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

- Fig. 8 Plan of Field I

from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Overall plan of Field I showing the possible relationship between the Early Bronze Age architecture of Area BB 100-600, and that of Areas BB 700/DD.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 3 Plan of Field I

from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Overall plan of Field I (Lower Tell) showing architecture relating to the Early Bronze Age complex(es) in Areas BB and DD (revised since 1995).

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

- Fig. 13 Location plan for

areas on Upper Tell from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 13

Plan of Square BB 700 (Grid F/G-1/2) at Phase L2. The numbered artifacts are:

- store-Jar

- store-Jar

- open-mouth vessel

- Juglet

- Jug

- store-Jar

- store-Jar

- beaker

- jug

- door-socket

- bowl

- jug

- platter

- flint scraper

- Juglet

- platter

- platter

- Jug

- Juglet

- juglet

- bowl

- juglet

- group of 3 juglets

- open-mouth vessel

- store-jar

- store-Jar

- Jug

- sunken stone bowl

Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 13 Location plan for

areas on Upper Tell from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 13

Plan of Square BB 700 (Grid F/G-1/2) at Phase L2. The numbered artifacts are:

- store-Jar

- store-Jar

- open-mouth vessel

- Juglet

- Jug

- store-Jar

- store-Jar

- beaker

- jug

- door-socket

- bowl

- jug

- platter

- flint scraper

- Juglet

- platter

- platter

- Jug

- Juglet

- juglet

- bowl

- juglet

- group of 3 juglets

- open-mouth vessel

- store-jar

- store-Jar

- Jug

- sunken stone bowl

Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

- Fig. 16 Plan of Stratum

L2 in Area BB 700 from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 16

Figure 16

Plan of Stratum L2 in Area BB 700 (Area 35-F/H-I/3).

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 12 Plan of Stratum

L2 in BB 700 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 12

Figure 12

Plan of Stratum L2 (revised 1993) in BB 700.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 16 Plan of Stratum

L2 in Area BB 700 from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 16

Figure 16

Plan of Stratum L2 in Area BB 700 (Area 35-F/H-I/3).

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 12 Plan of Stratum

L2 in BB 700 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 12

Figure 12

Plan of Stratum L2 (revised 1993) in BB 700.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 17 Plan of Stratum

L2 in Area BB 700 from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 17

Figure 17

Plan of Stratum LI in Area BB 700 (Area 35-F/H-1/3)

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 10 Plan of Stratum

LI in BB 700 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Plan of Stratum LI (revised in view of 1993 excavations) in BB 700.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 17 Plan of Stratum

L2 in Area BB 700 from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 17

Figure 17

Plan of Stratum LI in Area BB 700 (Area 35-F/H-1/3)

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 10 Plan of Stratum

LI in BB 700 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Plan of Stratum LI (revised in view of 1993 excavations) in BB 700.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 9 Sketch of the

Early Bronze Age complex in BB 700 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Sketch reconstruction of the Early Bronze Age complex in BB 700 looking north-east (not to scale).

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 9 Sketch of the

Early Bronze Age complex in BB 700 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Sketch reconstruction of the Early Bronze Age complex in BB 700 looking north-east (not to scale).

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 4 Location plan

for general loci within areas BB 700 and DD from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Location plan for general loci within areas BB 700 and DD.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

- Fig. 4 Location plan

for general loci within areas BB 700 and DD from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Location plan for general loci within areas BB 700 and DD.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

- Fig. 7 Area DD: Covered

drain and bath installation associated with Stratum L2 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Area DD: Covered drain and bath installation associated with Stratum L2.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

- Fig. 7 Area DD: Covered

drain and bath installation associated with Stratum L2 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Area DD: Covered drain and bath installation associated with Stratum L2.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1996)

- Fig. 13 Plan of 'scullery'

area in DD900 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Plan of 'scullery' area in DD900.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

- Fig. 13 Plan of 'scullery'

area in DD900 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Plan of 'scullery' area in DD900.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

- Fig. 46 - Iron age Section

above stratum XII in Area AA from Tubb et al. (1990)

Fig. 46

Fig. 46

Drawing of the main east section in Area AA showing complicated sequence of Iron Age occupation phases above stratum XII

(photo:JNI)

Tubb et al. (1990) - Fig. 4 AA 1300 (Area 32-E/G-6/7)

West Section from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 4

Figure 4

AA 1300 (Area 32-E/G-6/7) West Section

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 6 AA 1000/1100 (Area 32-C/E-7/9)

South Section from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 6

Figure 6

AA 1000/1100 (Area 32-C/E-7/9) South Section

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 2 North Section BB 900-1000

showing two phases of destruction of Stratum L2 staircase and evidence of faulting through seismic activity from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Area BB 700: North Section BB 900- 1000 showing two phases of destruction of Stratum L2 ' staircase and evidence of faulting through seismic activity

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 4 South and West

sections of 31-H-7 showing the stratigraphic sequence of phases below Stratum III from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 4

Figure 4

South and West sections of 31-H-7 showing the stratigraphic sequence of phases below Stratum III.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 46 - Iron age Section

above stratum XII in Area AA from Tubb et al. (1990)

Fig. 46

Fig. 46

Drawing of the main east section in Area AA showing complicated sequence of Iron Age occupation phases above stratum XII

(photo:JNI)

Tubb et al. (1990) - Fig. 4 AA 1300 (Area 32-E/G-6/7)

West Section from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 4

Figure 4

AA 1300 (Area 32-E/G-6/7) West Section

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 6 AA 1000/1100 (Area 32-C/E-7/9)

South Section from Tubb and Dorrell (1993)

Figure 6

Figure 6

AA 1000/1100 (Area 32-C/E-7/9) South Section

Tubb and Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 2 North Section BB 900-1000

showing two phases of destruction of Stratum L2 staircase and evidence of faulting through seismic activity from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Area BB 700: North Section BB 900- 1000 showing two phases of destruction of Stratum L2 ' staircase and evidence of faulting through seismic activity

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 4 South and West

sections of 31-H-7 showing the stratigraphic sequence of phases below Stratum III from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 4

Figure 4

South and West sections of 31-H-7 showing the stratigraphic sequence of phases below Stratum III.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

- Fig. 8a and 8b Photo of tell

and its relationship to the Jordan Valley Fault from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 8a and 8b

Figure 8a and 8b

Tell Saydiyeh archaeological site. (a,b) General view of the site and satellite imagery (inset) showing its relationship to the fault. The archaeological site is composed with a lower and an upper tell that were occupied at different periods. The original site was a limited mound that looked over the region and has grown with the successive addition of settlement layers, each related to a specific period.The obvious proximity of the JVF is marked by the active fault scarp. In (b), the satellite imagery shows the relationship between the active fault trace (thick line), the archaeological site (LT, lower tell; UT, upper tell), and geomorphology (white outline represents the extent of the microtopographic survey in Fig. 3b).

Ferry et al. (2011) - Fig. 8c Burn layer at

tell from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 8c

Figure 8c

Tell Saydiyeh archaeological site. Open pit at the top of the tell showing conspicuous ~5-cm-thick black burnt layers. Those layers contain broken pottery, charred wood, and ashes and are remnants of a widespread intense fire.

Ferry et al. (2011) - Fig. 8d 12th century

BCE olive processing area (Palace) that displays signs of destruction from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 8d

Figure 8d

The twelfth century B.C. olive processing area (Palace) that displays signs of destruction

(from Tubb, 1998)

Ferry et al. (2011) - Fig. 8e Blocked doorway

and broken vessel interpreted as a direct result of earthquake shaking from Ferry et al. (2011)

Figure 8e

Figure 8e

Blocked doorway and broken vessel interpreted as a direct result of earthquake shaking

(from Tubb, 1988)

Ferry et al. (2011) - Fig. 9 overhead view

of "Palace" in Area EE, stratum XII from Tubb (1990)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Area EE, stratum XII: overhead view of "Palace"

Tubb (1990) - Fig. 10 Crushed pottery

adjacent to water channel in westernmost plastered room of Area EE, stratum XII from Tubb (1990)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Area EE, stratum XII: water channel in westernmost plastered room. The crushed pottery vessel near to the scale is that shown on Fig. 14:1.

Tubb (1990) - Fig. 12 mud-brick paving

in room of "Palace" complex in Area EE, stratum XII from Tubb (1990)

Figure 12

Figure 12

Area EE, stratum XII: mud-brick paving in room of "Palace" complex

Tubb (1990) - Fig. 13 pottery vessels

on burnt floor of "Palace" in Area EE, stratum XII from Tubb (1990)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Area EE, stratum XII: pottery vessels on burnt floor of "Palace", close to tabun constructed of krater sherds

Tubb (1990) - Fig. 4 Area AA 900 showing

stalls and depressed stone-paved surface of stratum VII from Tubb and Dorrell (1991)

Figure 4

Figure 4

AA 900 from the west. The stratum V stalls are on the left of the photograph, and on the right is the depressed stone-paved surface of stratum VII.

Tubb and Dorrell (1991) - Fig. 16 Brick Collapse and

destruction debris in BB700 (Early Bronze II) from Tubb and Dorrell (1991)

Figure 16

Figure 16

Deposit of Early Bronze II pottery, in situ, showing nature of overlying brick collapse and destruction debris (BB 700).

Tubb and Dorrell (1991) - Fig. 17 Early Bronze II pottery

(in situ) on the floor of the stratum L2 building in BB 700 from Tubb and Dorrell (1991)

Figure 17

Figure 17

Deposit of Early Bronze II pottery, in situ, on the floor of the stratum L2 building in BB 700.

Tubb and Dorrell (1991) - Fig. 5 Deep storage

pit of Stratum IV in AA 1300 from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 5

Figure 5

AA 1300. Deep storage pit of Stratum IV. The rim of another such pit is shown at the top of the photograph.

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 9 Basalt tripod-stand

on floor of Stratum VII bathroom from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Basalt tripod-stand on floor of Stratum VII bathroom.

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 11 View over Area

AA 900 Stratum XII from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 11

Figure 11

View over Area AA 900 from the southwest, showing the walls, passageways and revetment of the 'Aqueduct' of Stratum XII.

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 12 Stone revetment

against western wall of aqueduct in AA 900 from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 12

Figure 12

Stone revetment against western wall of aqueduct in AA 900.

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 13 Part of Area EE

Stratum XII from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Part of Area EE from the south, showing the Stratum XII pool with its inlet and riser on the north side.

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 14 Broken Jars in

Area EE Stratum XII from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Egyptian style jars adjacent to the drainage channel of the Stratum XII pool in Area EE.

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 15 Area BB 700

from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 15

Figure 15

General view of excavations in Area BB 700, looking north-west. Room d is in the foreground

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 18 Broken and fallen

in situ Early Bronze II pottery in Room b of Area BB 700 Stratum L2 from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 18

Figure 18

Early Bronze II pottery in situ in Room b (Area BB 700, Stratum L2).

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 19 Cracked steps

leading down into Room d of Area BB 700 Stratum L2 from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 19

Figure 19

Area BB 700. Steps leading down into Room d (Stratum L2).

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 20 Tilted Wall in

Area BB 700 from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 20

Figure 20

Area BB 700. Angle between Walls H and P, showing L1 addition to L2 walls.

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 21 Area BB 700

Stratum L2 from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 21

Figure 21

Area BB 700. Dish in niche in Wall H (Stratum L2)

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 22 Platter broken

in situ on the floor of Room e from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 22

Figure 22

Area BB 700. Platter broken in situ on the floor of Room e (Stratum L1).

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 23 Fire pit in Area BB 700

from Tubb & Dorrell (1993)

Figure 23

Figure 23

Area BB 700. Fire pit in Lr levels of Rooms e and h.

Tubb & Dorrell (1993) - Fig. 14 Collapse in BB700

and Stratum L2 from Tubb and Dorrell (1991)

Figure 14

Figure 14

BB 700: stratum L2 building from the west.

Tubb and Dorrell (1991) - Fig. 5 Disrupted wall

of Stratum IIIB-C at 31-H-7 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 5

Figure 5

View of 31-H-7 showing disrupted north-south wall of Stratum IIIB-C.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994) - Fig. 11 Stone-lined pit

of Stratum LI in BB 900 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Stone-lined pit of Stratum LI in BB 900 (partially revealed in 1992).

Tubb & Dorrell (1994) - Fig. 13 Sunken store-room

in the Early Bronze Age complex in BB 700 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Sunken store-room in the Early Bronze Age complex in BB 700, showing entrance and steps.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994) - Fig. 14 Smashed storage

jars on the floor of the Early Bronze Age sunken room from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Large store-jars, smashed on the floor of the Early Bronze Age sunken room.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994) - Fig. 15 Mud-brick paved

staircase on the north side of the Early Bronze Age complex (Stratum L2) from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 15

Figure 15

Mud-brick paved staircase on the north side of the Early Bronze Age complex (Stratum L2).

Tubb & Dorrell (1994) - Fig. 16 Small room of

Stratum L3 in BB 1000 from Tubb & Dorrell (1994)

Figure 16

Figure 16

Small room of Stratum L3 in BB 1000, showing niche (on right hand side) and crushing basin with associated channel.

Tubb & Dorrell (1994) - Fig. 3 Early Bronze II

pottery assemblage in situ in area BB 700 from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Area BB 700: Early Bronze II pottery assemblage in situ in BB 1100.

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 4 Area DD

from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Area DD: General view looking east showing the extent of the season's excavations (DD 700-900).

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 5 Exposed Wall

in Area DD from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Area DD: View of the exposed wall which provides the linkage between the architecture of Area DD and that of Area BB 700 (DD 900).

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 6 Drainage installation

in Area DD from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Area DD: View from south of the Early Bronze Age drainage installation, consisting of a plaster lined 'bath' with its own drain leading into a larger drain (DD 700).

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 16 Area AA

from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 16

Figure 16

Area AA: General view from east during excavation of Stratum XIII showing, on the left, the remains of the stone terracing of Stratum XII. The tannur installation belongs to Stratum XIB.

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 17 Area AA

from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 17

Figure 17

Area AA: Mud-brick and stone blocking of northern entrance to the Stratum XII Egyptian Governor's Residency. Part of the Stratum XIII occupation surface is visible in the foreground.

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 18 Area AA

from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 18

Figure 18

Area AA: General view from South looking into the 1995 season's excavation area.

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 19 Area AA

from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 19

Figure 19

Area AA: Limestone slab in situ blocking entrance to the underground favissa most likely to be associated with the small Stratum XIA temple excavated in the 1986 season.

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 21 View of

Tell es-Saeidiyeh and Area KK from Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996)

Figure 21

Figure 21

Area KK: View of Tell es-Saeidiyeh and Area KK from the south.

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996) - Fig. 5 Faulted floor

from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Example of faulting on floor surface, a feature also visible in the section behind (BB 1000).

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 6 General view

of BB 1000 showing original features of Stratum L2 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 6

Figure 6

General view of BB 1000 showing original features of Stratum L2.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 7 in situ pottery

on the surface of the upper storey collapse in BB 1300 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 7

Figure 7

BB 1300, showing pottery in situ on the surface of the upper storey collapse.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 8 stone-lined pit

in BB 1100 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 8

Figure 8

BB 1100: stone-lined pit set into first-floor surface.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 9 east-west wall

showing the effects of slippage and faulting in BB 1100/I300 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 9

Figure 9

BB 1100/I300: substantial east-west wall showing the effects of slippage and faulting.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 10 Stratum L1

occupation resting on western wall of Stratum L2 'scullery' in DD 900 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 10

Figure 10

DD 900: Poorly preserved remains of Stratum L1 occupation resting on western wall of Stratum L2 'scullery'.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 11 Area DD 900

from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 11

Figure 11

General view of rooms excavated on the south side of Area DD (DD 900) in 1996.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 12 Broken platters

and vessels in 'scullery' area in DD 900 from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 12

Figure 12

View from the north of 'scullery' area in DD 900, showing platters and other vessels on surface.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 14 Stack of bowls

in situ in scullery area from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Stack of bowls in situ in scullery area.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 15 Room to south of

'scullery' from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 15

Figure 15

Room to south of 'scullery', showing well-preserved entrance on south side.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 16 Plaster-lined bin

in a small room of 'western complex' (DD 700) from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 16

Figure 16

Plaster-lined bin in a small room of 'western complex' (DD 700).

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 17 General view of

Area NN, west of the Lower Tell from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 17

Figure 17

General view of Area NN, west of the Lower Tell.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 18 Early Bronze I

city wall in Area NN from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 18

Figure 18

Badly weathered Early Bronze I city wall in Area NN.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 23 City wall (Stratum 13)

in west section of Area KK from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 23

Figure 23

City wall (Stratum 13) in west section of Area KK.

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Fig. 24 Part of Stratum

14 building in Area KK from Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997)

Figure 24

Figure 24

Part of Stratum 14 building in Area KK, showing cobble floor with inset pottery bowl (latethirteenth century B.C.).

Tubb, Dorrell, & Cobbing (1997) - Seismic Faulting under

Early Bronze Age debris from Pritchard (1965b)

Fault produced by an earthquake that disturbed the striations of the virgin soil immediately under the debris of the Early Bronze Age

Fault produced by an earthquake that disturbed the striations of the virgin soil immediately under the debris of the Early Bronze Age

Pritchard (1965b)

- from Pritchard (1965a) and Tubb (1990) and others

- This is an incomplete construction

| Stratum | Age | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| XV | Stratum XV showed evidence for having been destroyed ... Strata XIV and XV, should be dated to the end of the thirteenth and the very beginning of the twelfth centuries B.C.- Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996:24-30) |

||

| XIV | Strata XIV and XV, should be dated to the end of the thirteenth and the very beginning of the twelfth centuries B.C.- Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996:24-30) |

||

| XIII | dating in the second quarter of the twelfth century would seem to be indicated- Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996:24-30) |

||

| XII |

|

||

| XI |

|

||

| X |

|

||

| IX |

|

||

| VIII |

|

||

| VII | late 9th-early 8th century BCE |

|

|

| VI | |||

| V | |||

| IV | |||

| III | |||

| II | |||

| I |

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

Excavation reports such as Tubb (1988), Tubb (1990),

Tubb and Dorrell (1991), Tubb and Dorrell (1993),

Tubb and Dorrell (1994), Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1996),

Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1997), and, apparently

Pritchard (1965a) report and document widespread collapse, fire, and possible localized faulting and displacement in Stratum L2 on the Lower Tell of Tell Saidiyeh. L2 was dated, based on pottery,

to Early Bronze II (~2900-~2650 BCE according to Tubb, 1998:41). Although the destruction layers in Area BB and DD were significantly disturbed and displaced by site erosion and later activities such a grave cutting, significant evidence

for widespread destruction and fire remained. Destruction debris included ashes, burnt mud-brick rubble, charred timber, and crushed and fallen pottery.

Fault displacement was reported with displacements of 25 and up to 50 cm. along with folding of some mud-brick walls. Although excavators entertained the possibility that some of the faulting may be due

to settlement, the lower tell is located less than 150 m from the active Jordan Valley Fault

(Ferry et al., 2011:Fig. 8a & 8b).

This, in turn, may suggest that the Lower Tell was in the epicentral region when the earthquake struck.

In some parts of the lower tell, two burnt destruction layers were identified which was interpreted as a manifestation of two storey collapse rather than two seperate events.

In one room designated as the 'scullery' in Area DD, Tubb, Dorrell, and Cobbing (1997:62) found

a 'table setting' containing 11 stacked bowls - some with food residue, 11

Abydos

mugs, 11 flint blades, and 11 long, narrow bone points (possibly tooth picks?)

. This was interpreted as tableware from a meal which was waiting to be cleaned when the earthquake struck.

| Excavator's Date | Proposed Cause of Destruction | Probability of an earthquake | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7th-6th century BCE | Fire | Low |

|

| mid 8th century BCE | Anthropic postearthquake ? | Average |

|

| 1150-1120 BCE | Fire | High |

|

| Late early Bronze I - ~2900 BCE | Unknown | High |

|

| Period | Age | Site | Damage Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| EB II | 3000-2700 BCE | Tell es-Sa'idiyeh | faults and slips, as great as 0.5 m. Floors turned into ledges and steps (Area B). Lines of slippage and faulting detected in Area DD in the mudbrick houses. Collapse of houses in the lower tell and signs of a strong fire (Tubb et al. 1997: 58, 62). |

| Iron I | 1200-1000 BCE | Tell es-Sa'idiyeh | late 12th century BCE. Thick debris from city walls, public and private buildings and signs of fire (Stratum XII) were noted at the site. The excavators’ impression was that people had time to escape (Tubb 1988: 41). Building in Area AA suffered severe faulting; five intersecting cracks, the largest responsible for a stratigraphic downshift of nearly 50 cm (Tubb and Dorrell 1993: 58-59). |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | Tell es-Sa'idiyeh | houses (Stratum VI) from the mid-8th century BCE may have been destroyed by an earthquake, and were leveled in order to prepare the ground for new buildings (Ferry et al. 2011: 56; Tubb 1988: 26). |

- from Tubb (1990:28-29)

Elsewhere in area EE, the heavily burned floor surfaces of the various rooms produced a repertoire of pottery types similar to, yet somewhat more extensive than the stratum XII material from area AA recovered in 1987 (Figs. 13- 14). Certainly, the previously suggested date of 1150 B.C. for the destruction of stratum XII can, on the basis of the material recovered from the Western Palace this season, be fully substantiated.

Before proceeding to discuss the linking together of areas AA and EE on the Upper Tell, and in order that the significance of this operation may be appreciated, it will be necessary to review briefly the stratigraphic situation in both areas.

In 1985-87, Area AA had consisted of a relatively small area situated in the south-eastern corner of Pritchard's large exposure of the 1960s(see Tubb 1988, 28). Here, excavations revealed poorly preserved and fragmentary remains of stratum VI, a phase which in fact Pritchard had partially exposed before his work was terminated in 1967. Below were found the better preserved and architecturally coherent remains of stratum VII, a city level of the ninth-eighth century B.C. which had been extensively revealed by the Pennsylvania expedition in the area lying just to the north of Area AA (see Pritchard 1985,fig. 177and Tubb 1988,fig. 4).

Stratum VIII, a non-architectural phase of industrial usage, was characterized by fine ashy deposits, extremely dense in places, emanating from areas of intense heat generation which had been created by the rough modification of the abandoned architectural elements of stratum IX. In places, for example, stratum IX walls had been re-used to form the backs of scooped out, level platforms, which had then served as the sites for some industrial process, the nature of which is still unknown. Whatever the process might have been, it produced a large volume of ashy waste, and this was seen to have covered the abandoned remains of stratum IX, lying thickly where it had slumped into the various rooms and chambers, but appearing as little more than a thin greyish-black band where it had risen over more elevated ground.

Below stratum VIII, and above the large public building of stratum XII excavated at the end of the 1987 season, three architectural phases were isolated, the uppermost, stratum IX, as mentioned above, having been abandoned. Although stratum IX had suffered considerable damage through weathering and erosion, two phase (IXA and IXB) of a quite large building were found, together with part of its associated, wellconstructed, stone-paved courtyard (Tubb 1988, 34- 35).

Stratum X was also characterized by a well-built stone courtyard, but in this case it was associated with unusual, partially sunken, stone-lined structures which were interpreted as pens for livestock. The courtyard was found to belong to a massive, stone-constructed building, only one small corner of which was revealed within the excavation area, the remainder lying to the north and west (Tubb 1988, 35-37).

A similar but less massive building clearly occupied the same position in stratum XIA, but here, to the south-east, and separated from it by a north-south street, was found a small bi-partite building which, on the basis of various internal installations and finds, could be interpreted as a temple (see Tubb 1988, 37-39).

Stratum XIA was found to have been built on a dense layer of silting which in turn covered the deep deposit of intensely burnt destruction debris overlying the architecture of stratum XII. Excavation of stratum XII in 1987 uncovered the remains of a large public building which, to judge from its Egyptian-style plan and construction method, must be seen as yet another example of a so-called 'Egyptian Governor's Residency'. The building had clearly been abandoned following its destruction, and, to. judge from the depth of silt overlying the collapsed debris, some considerable period of time must have elapsed before the construction of stratum XIA, perhaps as much as one hundred years.

Within two of the rooms of the residency, evidence was found for a phase of squatter or camp-site occupation immediately following the destruction. The collapsed debris appeared to have been levelled, and rough surfaces had been made within the confines of the still standing walls. Represented only by hearths and grinding stones, this phase is referred to as stratum XIB (see Tubb 1988, 39-40).

In 1989, Area AA was greatly expanded to the west, and a large extent of the stratum VII city was cleared (see Fig. 3: Houses 73-79). The expansion also demonstrated that stratum VI, defined and excavated by Pritchard in the area to the north of AA 100-500, did not extend to the western side of the tell, but terminated along an approximately north-south line in AA 800/1100 (see Tubb 1990, 21-26 for details of the 1989 season).

Preliminary Stratigraphy of Area AA

Preliminary Stratigraphy of Area AATubb and Dorrell (1991)

Excavations in Area EE in 1986-89 had produced a rather different, or more accurately, a greatly compressed sequence. For here, stratum VI was found to be absent, and no evidence at all was found for strata VIII, IX, X or XI. Indeed stratum VII was found to overlie stratum XII directly, and it was clear in places that a levelling operation had been conducted prior to the construction of stratum VII, a process which had truncated the wall tops of the western public building complex to almost uniform heights. This levelling process would, of course, have removed all traces of strata VIII, IX, X and XI, especially if, as seems likely, these phases had been built on the internal downslope created by the destruction of the massive stratum -XII city wall and 'palace' complex. In other words, it is. impossible from the evidence in Area EE to establish whether strata VIII, IX, X and XI had been cut out by the levelling operation for stratum VII, or whether these phases had simply never existed on this western side of the site.

To a large extent, excavations in 1990have answered this important question. In AA 900, and in its westward extension 950 (below the level of the stratum III cutting-see below), excavations first revealed remains of stratum V (Fig. 4). Two small, rectangular, partially sunken structures were found, built of poor quality mud-brick (see Fig. 5: 23-B/C-l). The eastern room, which had a finely paved stone floor, measured only 1·52 m. (north-south) by 1·20m. (east-west). A small stone door socket found close to the external south -east corner suggests a door opening outwards, and one which most probably occupied the whole width of the room. The western room was somewhat larger, with internal dimensions of 1·76 m. (north-south) by 1·30 m. (eastwest). The floor in this case was of beaten earth, and no evidence was found for the doorway. The eastern room contained the partially articulated skeleton of a young equid, and the western room contained the more fragmentary skeletal remains of a similar, but adult animal. It would seem reasonable to suggest an interpretation for these two small rooms as stalls, the unfortunate animals presumably having been abandoned and killed during the destruction of stratum V.

In theory, the eastern of the two 'stalls' ought to have been excavated and recorded by Pritchard, since it lies well within the area cleared by him down to stratum V (see Pritchard 1985, fig. 179-square 23-C-l). The reason for its omission from his plan lies in the fact that stratum V, at this particular point, appears to have been founded at a lower level than elsewhere. Pritchard had simply not excavated deeply enough. As will be seen below with regard to stratum VII, the depression /of stratum V at this point was due to the subsidence of the underlying stratigraphy, resulting ultimately from the unusual configuration of stratum XII. In any event, it is now possible to. add the two stalls to the south of Pritchard's House 25, where they would presumably have bordered the east~west street in 23-(B)C/G-l, 32- (B)C/G-I0 (see Pritchard 1985, fig. 179).

Below stratum V excavations revealed further remains of stratum VII (see also Fig. 4). ...

The excavation of Area BB 700 was started in 1989 primarily to determine how far the lower tell cemetery, which is still being excavated in BB 100-600, extended to the south and to examine the nature and density of burials in this area. It has become clear that the number of burials was lessthan in the more central area, 30 m. to the north: only five graves were found in 1989 and another two this year (graves 386 and 394, see Appendix for details).

The upper 50-100 cm. of the area was composed of mixed, silty material, probably wash from higher up the slope to the north, and possibly disturbed by ploughing. Within the lower part of this stratum were numbers of mud-bricks, fallen on their sides and still lying en echelon, as though from a collapsed wall. There were also patches of cobbles, but it was not possible to establish any connection between these and the collapsed walls, nor to date either. Presumably they post-date the main occupation phases of the tell.

Below this level were series of bricky and ashy strata following, approximately, the slope of the present tell surface. These ran over the eroded tops of several walls which proved, on further excavation, to be of Phase L2, identified elsewhere as the final construction phase of the Early Bronze Age on the site. These walls were standing to heights of up to 1·5 m., and the spaces between them were filled with destruction debris, undisturbed save for a few grave cuts. This stratum of undisturbed material is far deeper than the equivalent level on the summit of the lower tell, where close, and in many cases overlapping, grave cuts of the Late Bronze/Ear ly Iron Age have so churned up the earlier deposits that only a few pinnacles of L2 material in situ could be found above foundation level. It also seems likely that the erosional regimes of the two areas were rather different. There is strong evidence that the L2 settlement was extensively destroyed by an intense fire. Following this event the site was abandoned save for local squatter occupation. Erosion of loose material and ash apparently occurred over the whole lower tell down to the underlying strata of packed, hard-burnt debris and fire-baked standing walls. Thereafter erosion went on more slowly and selectively-the more so perhaps as the tell became covered in vegetation- and decayed mud-brick was eroded from the summit of the tell and deposited down-slope, giving protective cover to these lower areas.

Although there is, as yet, no direct stratigraphic connection between the destruction levels in BB 700 and those in Area DD (first excavated in 1985) and in parts of BB 100-600, their relative heights, types of brick, architecture, and the intensity of their destruction all suggest that they were contemporary. Both in BB 700 and in Area DD there is evidence of a short phase of later occupation, without significant building activity. In BB 700 this phase-L1-is represented by a fire-pit dug slightly into the destruction levels of L2 and backed against the upper part of a surviving wall of that phase. The fire-pit is in the centre of a rough semi-circular enclosure, some 2 m. in diameter, formed partly by a line of heavy stones and partly by a vertical surface cut into the rubble. Where the top of the wall was missing it was repaired with a couple of un-burnt bricks. The impression is of a roughly-built wind-break or the footings for a temporary shelter. Several pits were dug into the rubble beyond the semi-circle. It seems likely that this was a phase of squatter-occupation, possibly by survivors of the destruction. There was no pottery that could be unequivocably assigned to the phase.

Beneath this phase lay 1-1.5 m. of debris, with many heavily-burnt bricks, large fragments of reed-impressed roofing clay and mortar, and charcoal. There were also discontinuous patches of carbonized cereals, perhaps from grain that had been spread out to dry on a flat roof. The area of most intense heat seems to have been to the north-east of the square, and walls and debris were more heavily burnt-some appeared almost vitrified--on this side of the square than they were on the other.

A plan of the underlying structure is shown in Figs. 13-14. A well-built wall, (Wall D) runs almost east-west across the square, turning northward near the west baulk at a little less than a right-angle (Wall C). Within this latter section is a doorway with a door socket indicating that the door opened inward, and with a low step down to the west. The north jamb of this doorway continues westward as a low wall c.40 cm. high (Wall F). In the angle thus formed there may have been a bin, accessible through a hatch-way in the northern part of Wall C, but its form will be determinable only when the north baulk is removed. Wall D seems to continue into the east baulk, but the area has been disturbed by Ll pits. Another, narrow wall (Wall B) runs north-south dividing the space north of Wall D into two rooms, neither of which are wholly within the square. Wall B stops short of meeting Wall D, giving a doorway between the two rooms with two shallow steps down from east to west. A platform c. 10 cm. high occupies the south-west corner of the western room. All these walls, including the returns of doorways and the top of Wall F, were smoothly plastered and are now burnt to a rock like hardness. Brick sizes average 42 x 22 x 7 cm., Walls D and C being header-built and as thick as the length of a brick, and Wall B stretcher-built, as thick as one width. It seems likely that Wall B was a partition rather than a load-bearing wall. Both rooms were floored with fine plaster, curved up the walls and carried smoothly down the steps and over the platforms. Beyond the doorway in Wall C the surface is compacted plaster and pebbles and this area was probably exterior to the building.

In the southern part of the square a narrow, roughly built wall (Wall E) runs from the south-west to join Wall D at an acute angle. It appears to have been built later than Wall D, being cut into it and the angle buttressed with stones. Behind Wall E, in the south -east corner of the square, there may have been a large bin, but the area was so disturbed by Ll pits that certainty must await excavation to the east.

The south-west corner of the square contains a somewhat puzzling structure: two mud-brick platforms, one slightly curved, with a narrow channel, c. 10 cm. wide, between them. The platforms are of similar height, c. 20 cm., and both are unplastered. The surface bounded by the walls and the platforms is of patchy and decayed plaster and slopes down from east to west at a gradient of c. 1 in 8,5. Within the angle formed by Walls D and E is a stone basin, set in the floor, at the bottom of a shallow funnel of pebbles and mortar (Fig. 15). The basin is some 12 cm. in diameter, cut into a larger block, and c. 10 cm. deep, almost hemispherical, and highly polished. It is not easy to determine, nor even to imagine, the function of this area. The unprotected surfaces of the platforms suggest that it was covered by some sort of shelter, and the slope and channel suggest drainage. The only function that comes to mind is slaughtering or butchery, with the basin serving to catch the blood, but there is no real evidence.

An assemblage of pottery was found in situ on the floors of the two rooms (Figs. 16-17). Many of the larger vessels had been crushed by the destruction and the plot of their positions in Fig. 13 may not represent their true sizes and proportions. They include typical Early Bronze II red-slipped and burnished platters, 'ribbon-painted' store jars, simple bowls, large open-mouth vessels with both ledge and lug handles, and a series of jugs and juglets based on the Abydos type. Many of the jugs and juglets might have fallen from pegs or shelves, and the three large platters, in the middle of the floor, might well have slipped or fallen from some other position. The store-jars and the open-mouth vessels, however, were certainly still in situ, and several of them were still on pot-stands of stone or mud-brick. A selection of the pottery vessels is shown on Fig. 18.

Overall the impression is of two store-rooms with ready access to stores-a larder in fact. The number of vessels, and their arrangement, also suggests very strongly that they served a building or complex of more than domestic size, and somewhere near at hand there should be a cooking-area of equal scale. The layout indicates that access to both rooms was usually from the north, and the main part of the complex might well lie in that direction. Obviously.however, more of the buildings also lies to the east, and it is intended to extend the excavation in both directions. Further excavation northward will move towards the higher density area of the cemetery, and presumably towards· the thinner protective wash deposits of the lower tell summit. It can only be hoped that there will remain sufficient undisturbed strata of this exceptionally rich phase.

Excavations on the Upper Tell in 1992 were continued in three main areas (see Figs. 1 and 2): in AA 1300, an area initiated in 1990, lying to the south of the main area of AA, the investigation of which had, in that season, revealed the substantial foundations of a building most probably dating to the Hellenistic period (see Tubb and Dorrell 1991, 75-76); in AA 900, the most westerly extension of Area AA in which remains of stratum VII overlying stratum XII had been excavated in the previous season; and in Area EE, where the removal of the overlying strata V and VII in 1990 had provided a greater area for the continued investigation of stratum XII.

Taking these areas in turn, the objectives in 1992 were: in AA 1300, to more fully examine the Hellenistic building, and to extend the excavations in depth in order to provide a further stratigraphic correlation with the sequence previously established by Pritchard; in AA 900, to reveal the remains of stratum XII; and in EE, to investigate further the stratum XII public building or palace complex, the excavation of which began in 1986.

Further investigation of the surface remains in this area has enabled a coherent plan to be developed (Fig. 3) which incorporates the stone foundations recovered in AA 700 in the 1989 season (see Tubb 1990, 20-22), together with the surface features previously recorded and published by Pritchard in Area 32 (see Pritchard 1985, Fig. 189). The resultant plan, although by no means complete, provides evidence not for a series of service rooms relating to the Hellenistic 'fortress' excavated by Pritchard, as previously suggested (Tubb and Chapman 1990, 116), but rather for an independent building which, in many respects, reflects the general character of that previously excavated building. It is possible indeed that the building in AA 1300 is a second, similar public building which is presumably later, since neither traces of mud-brick superstructure nor any intact floor surfaces were found. Furthermore, removal of the stone foundations at the western end of the area revealed the remains of an earlier phase of architecture on a slightly different line and orientation which can almost certainly be related to Pritchard's Hellenistic building of stratum II. Only a small exposure of this earlier phase has so far been made, but enough to demonstrate that its walls are preserved with their mud-brick superstructure, and more significantly, that associated floor surfaces also exist. As a clarification and correction to the 1990 season report, it is indeed now possible to relate the kitchen surface then excavated not to the upper phase of stone foundations, but rather to the earlier architectural phase. Further stretches of related surface were isolated this season, and in all cases they were associated with patches of black ashes and burnt mud-brick debris. It is for this reason that it is suggested that this earlier phase of architecture corresponds to Pritchard's fortress to the east, a building which also showed clear evidence of having been destroyed (see Pritchard 1985, 69-75). On the basis of these results, therefore, it is proposed to subdivide stratum II into two sub-phases; IIA for the building represented in Fig. 3 (foundations only), and lIB for the underlying building in AA 1300 and Pritchard's 'fortress' or public building. The material published in Tubb and Dorrell 1991, fig. 10 should therefore be assigned to stratum lIB.

At a depth of only 25 cm. below the well-defined floors of stratum lIB was found a somewhat ephemeral surface, or more correctly package of surfaces, belonging to stratum IV (see Fig. 4 for West Section drawing). This appeared as a tightly layered series of trampled surfaces, the uppermost bearing a thick (2 cm.) deposit of dense black ashy material. As in previous exposures of stratum IV (see Pritchard 1985, 34-42; Tubb 1990, 22-23; Tubb and Dorrell 1991,74) this rather enigmatic phase was found to be devoid of architectural elements but contained instead a number of well-dug but unlined storage pits (Fig. 5). Analysis of deposits of an extremely fine white material found at the bases of two such pits indicate that they had been used to contain the chaffy residues of threshing, most probably intended for animal fodder.

The stratum IV pits had been cut into the destruction debris and architecture of the underlying stratum V. Destroyed by fire towards the end of the eighth century B.C., stratum V illustrates an intelligently planned and well-constructed Iron Age settlement, well documented by the large expanse now revealed by both the Pennsylvania and British Museum expeditions (see especially Pritchard 1985, Fig. 179 and Tubb and Dorrell 1991, fig. 5). The limited sounding in AA 1300 produced but one wall, running east-west, together with an associated stone-paved courtyard to the north (the wall undoubtedly forms a part of the south-central housing block as represented by Pritchard's rooms 14 and 16). Not unusually for stratum V, the wall was built without stone foundations.

Below the stratum V wall, and running on almost the same line, was found an earlier wall constructed of rather poor quality yellowish mud-bricks. Associated with this wall was a thinly plastered floor surface to the north which bore a heavy deposit of largely unburnt mud-brick debris. These remains can be attributed to stratum VI, a phase which was well defined by Pritchard in the area to the north of AA 1300, but which has hardly been encountered by the current expedition in any of the more westerly exposures. Indeed evidence was found in 1989 to indicate that stratum VI was a somewhat restricted settlement confined to an inner zone of the tell's surface. The westward termination point of stratum VI can clearly be seen in the south section of Area AA 1000/ 1100, the drawing of which was completed this season (Fig. 6: see Fig. 2 for location, and also see Tubb 199°,24 for an extramural burial of stratum VI). Perhaps the most interesting finding in AA 1300 in 1992 was made below stratum VI. For in the underlying stratum VII, again a well documented city phase of the ninth-eighth century B.C. (see Pritchard 1985, fig. 177; Tubb and Dorrell 1991, fig. 3), were found the remains of a housing block as represented by Pritchard's rooms 14 and 16). Not unusually for stratum V, the wall was built without stone foundations.

Below the stratum V wall, and running on almost the same line, was found an earlier wall constructed of rather poor quality yellowish mud-bricks. Associated with this wall was a thinly plastered floor surface to the north which bore a heavy deposit of largely unburnt mud-brick debris. These remains can be attributed to stratum VI, a phase which was well defined by Pritchard in the area to the north of AA 1300, but which has hardly been encountered by the current expedition in any of the more westerly exposures. Indeed evidence was found in 1989 to indicate that stratum VI was a somewhat restricted settlement confined to an inner zone of the tell's surface. The westward termination point of stratum VI can clearly be seen in the south section of Area AA 1000/ 1100, the drawing of which was completed this season (Fig. 6: see Fig. 2 for location, and also see Tubb 199°,24 for an extramural burial of stratum VI).

Perhaps the most interesting finding in AA 1300 in 1992 was made below stratum VI. For in the underlying stratum VII, again a well documented city phase of the ninth-eighth century B.C. (see Pritchard 1985, fig. 177; Tubb and Dorrell 1991, fig. 3), were found the remains of a bathroom complete with toilet, basin and drainage system (see Figs. 7 and 8). The bathroom, which is situated in the south-west corner of House 72 (see stratum VII plan in Tubb and Dorrell 199 I, fig. 3), was approached by three stone-built steps, presumably constructed in order to gain sufficient height for the water outflow. Against the south wall was a plastered bench, and extending northwards from this, against the west wall, was a wide plaster-lined channel connected to the base of the basin. The toilet was set on a mud-brick pedestal and had a plastered seat. An outflow hole led from the base of the toilet to a narrow plastered channel which took the effiuent to a small conduit in the east wall and into a brick covered soak-away in the courtyard below. On the floor to the north of the toilet was found a finely worked basalt tripod-stand (Fig. 9). The east-west wall on the south side of the bathroom is the exterior wall of House 72, and to the south of this was found a small expanse of an east-west street with a further housing unit beginning to the south. As noted previously, the exterior walls bordering the street had been provided with raised stone footings to protect the foundation courses.

Excavations in AA 900 in 1990 had revealed a substantial depression of the stratigraphy in this area, resulting most probably from earthquake faulting with related subsidence. As a consequence of this general lowering it had been possible to identify and reveal architectural features relating to stratum V which had literally been overlooked by the Pennsylvania expedition (see Tubb and Dorrell 1991, 72 and fig. 5 for additions to the stratum V plan). Operations had concluded in 1990 with the excavation and removal of the underlying remains of stratum VII, which included a probable temple (Tubb and Dorrell 1991, fig. 3). This building (House 80) was found to overlie directly dense and intensely burnt destruction debris which, from the previously undertaken excavations in area EE (see below), was known to be associated with stratum XII, the important twelfth century B.C. Egyptian phase of occupation represented by the Residency building in area AA, the Western Palace complex and city wall in area EE, the water system staircase on the north slope, and the Lower Tell cemetery. Operations in 1992, therefore, were aimed at revealing further architectural remains of this period.

The excavation of this area proved to be extremely complicated. Not only had it suffered considerably from the effects of faulting (there were no less than five intersecting cracks, the largest of which had been responsible for a stratigraphic downshift of nearly 50 em.), but the levelling operation in preparation for the construction of stratum VII had removed much of the architecture to foundation level. Had this occurred in any other stratum the problem would not have been so severe, since the foundation courses would have been preserved. However, a peculiarity of the architecture of stratum XII is that it does not use stone foundations, but relies instead on a dense matrix of pi see to support the embedded wall foundations. Nevertheless, it was eventually possible to isolate and establish the extraordinary plan shown in Figs. 10-11. It essentially consists of two passageways or channels, each stepping in a series of terraces or internal steps down towards the south-west, contained to the south-east by two walls of extremely poor quality mud-brick and to the north-west by a heavier construction composed entirely of pisee. It was presumably the use of this building material that necessitated the massive stone revetment against its western face (Fig. 12). The southernmost wall appears to terminate against a terrace edge or step, at which point the more southerly passage develops into an open space. The more northerly passage continues, however, beyond the point at which it was at some stage blocked by large boulders. At the western end of the area a small doorway gives entry to the northern passage from the west. Dense mud-brick destruction debris was encountered on the south-east side of the area, and the southern and central walls were extensively fire-damaged. The passageways themselves showed little evidence of burning. Both were thickly plastered (up to 8 cm. thick in places), and in both cases there were dense deposits of water-laid silt covering the surfaces. These points alone would indicate some water-related function for the unusual construction, but more suggestive and interesting still is the orientation of the excavated features. For, as can clearly be seen on Fig. 10, to the south-west the passageways, or perhaps more correctly channels, are in direct alignment with the pool and bath complex of the Western Palace in area EE. More remarkable yet is that if the line of the channels is projected to the north-east it coincides exactly with the top of the water system staircase on the north slope (see Pritchard 1985, 57-59 and Tubb 1988, 46, 84-87 for details of the staircase and the water system). It seems possible, therefore, that the unusual structures revealed in AA 900 represent a type of aqueduct conveying water from the spring-fed water system on the north side of the city to the bath and pool complex of the Western Palace. The gradient and stepping of the passages suggest that if water had been emptied at the top of the water system staircase it would have flowed to the Western Palace quite easily. However, since the passages contained large quantities of sherds of Egyptian-style jars (identical to those found in the pool of the Western Palace), the passages might equally have been used to transport the water manually.

There were three main objectives in Area EE in 1992, all directed towards the Western Palace Complex, a large building of stratum XII situated directly behind the city wall of this phase. The first objective was to try to establish the position and the character of the outside face of the stratum XII city wall. The interior face had been isolated as long ago as 1986, and indeed appears on the previously published plans (Tubb 1988, fig. 2 I; 1990, fig. 8). The outside face, however, had managed to resist all attempts at definition despite numerous scraping operations on the western slope. In 1992, therefore, a more drastic course of action was decided upon and a series of horizontal wedges was cut into the western side of the tell.

The second objective, related to the first, was to investigate by means of a series of trial trenches and probes a number of problems which had remained unresolved since 1989 (when the last plan of Area EE was drawn) in an attempt to clarify the somewhat confusing layout of the complex.

The final objective was to examine further the unusual pool which had been investigated in 1989 and which appeared at that time to lack any form of architectural containment.

The results of all three investigations can clearly be seen on the revised plan of EE, shown together with AA 900 in Fig. 10. The outside face of the stratum XII city wall was established, as was also the manner in which the wall had been founded. A near vertical-sided trench had been cut down into the slope of the mound, and in the bottom of this were placed large flat stones. Above these had been poured a thick layer (about 35 to 40 cm.) of pisee, and it was into this bedding matri-x that the lowest courses of brickwork had been set. As had been stated in 1987 (Tubb 1988,41 and 44-45) but subsequently denied (Tubb 1990,26-27) the city wall of stratum XII is indeed a casemate system with small compartments filled entirely with mud-brick rubble. These casemates had been missed in 1989, leading to the impression that the city wall was of solid construction. The external wall of the casemate system is I. 10m. wide, and the width of both the casemate compartments and the internal wall is 1.20 m., giving a total effective width of the stratum XII city wall of 3.50 m. A buttress was also found this season flanking the stone-paved passageway in ]/K-8 (note that the dotted buttress in H-7/8 is hypothetical) .

Other revisions to the previously published plan based on this season's work are mostly concerned with the internal subdivision of some of the rooms and the provision and position of doorways.