Jerusalem - City of David

City of David from the southeast

City of David from the southeastBiblePlace Blog - 18 July 2021

BiblePlaces.com

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| City of David | English | |

| Ir David | Hebrew | עיר דוד |

| Wadi al-Hilweh | Arabic | |

| Silwan | Arabic | سلوان |

| Ophel | ||

| Zion - not to be confused with modern Mount Zion | Hebrew | צִיּוֹן |

The conquest of the stronghold of Zion and its becoming the City of David are described in 2 Samuel 5:6-9 as a daring deed on the part of the king [David], but in I Chronicles 11:4-7 it is ascribed to Joab, who thus gained his lofty position under David. It can be assumed that David took Jerusalem early in his reign, prior to the events around the pool at Gibeon (2 Sam. 2:12-32) and the death of Abner (2 Sam. 3:20-27). Joab was already the commander of the Judean army, and the foreign enclave between Judah and Benjamin had already been eliminated. The Jebusites were not wiped out but rather continued to live "with the people of Benjamin in Jerusalem to this day" (Jg. 1:21).

David seems to have transferred his seat from Hebron to the new capital at Jerusalem some seven years after he had conquered the stronghold of Zion. During this period several events occurred that led to the strengthening of David's kingdom. The new capital became the royal estate, thus forging a bond between the City of David and the Davidic Dynasty. This bond was a decisive factor in the history of the kingdom for many generations.

There are few references in the Bible to David's building activities. His principal efforts - "And he built the city round about from the Millo in complete circuit" (1 Chr. 11:8; 2 Sam. 5:9) - should be ascribed to his early years in the city. The construction of the House of Cedar (apparently on the Millo) by craftsmen sent by Hiram, king of Tyre, apparently took place later (2 Sam. 5:11).It is assumed that David extended the fortified city on the north, toward the Temple Mount. This seems to have led to the breaching of the older city wall north of the stronghold of Zion, until Solomon "closed up the breach of the City of David his father" (1 Kg. 11:27), strengthened the Millo, and began to erect his new acropolis, including the magnificent structures on the Temple Mount itself.

The Valley Gate apparently stood on the west of the spur, in the vicinity of the later gate in the western wall of the City of David discovered in J. W. Crowfoot's excavations. The term Millo may have designated the terraces on the eastern slope of the southeastern spur that formed retaining walls for the structures above. It seems to have been here that the more splendid of the buildings in the City of David were built, such as the "house of the mighty men" (Neh. 3:16), the "house of cedar" (2 Sam. 7:2), and the "tower of David" (Song 4:4). Both man and nature worked toward the obliteration of these structures, and even in the period of the monarchy it was necessary to repair the Millo from time to time. Finds from the zenith of the period of the monarchy were discovered in the excavations carried out in the City of David by K. M. Kenyon and Y. Shiloh.

David brought the Ark of the Covenant, symbol of the unity of the tribes and of the covenant between the people and God, to Jerusalem when it became the royal city of Israel, and high officials and a permanent garrison were stationed here. Thus, he established Jerusalem as the metropolis of the entire people and the cultic center of the God of lsrael. In the latter years of his reign, David built an altar on the Temple Mount; according to the tradition recorded in the Bible, David purchased the threshing floor of Araunah the Jebusite, upon God's command, for this purpose. lt is clear that this site was held sacred even prior to David, for an elevated, exposed spot at the approaches to a city often served as the local cultic spot. The sanctity of Jerusalem, atop the Temple Mount, is already inferred in the Book of Genesis (Mount Moriah), although this is anachronistic. The tale of the connection between Abraham and Melchizedek, king of Salem and "priest of God Most High"- who blessed the patriarch and assured him of victory over his adversaries, receiving "a tenth of everything" (Gen. 14:18-20) - is the outstanding example. Psalm 110 indicates the importance placed by tradition upon Melchizedek as an early ideal ruler. It uses his prestige to strengthen the claim on the city and the legitimacy of his successors here, the Davidic line,. The story of the sacrifice of Isaac (Gen. 22) is also revealing. The spot on one of the mountains in the land of Moriah, where Abraham built his altar, was the place called "the Lord provides," the site on which David built his altar much later. Thus, David is regarded as having rebuilt the altar of Abraham on this sacred spot.

Because the 1st century CE historian Josephus mistakenly identified a structural high sometimes called the western hill southwest of what is now the old city of Jerusalem as the Mount Zion of King David's time, this area in the modern city of Jerusalem is currently called Mount Zion. Nearby, close to the Jaffa Gate, is a structure known as the Tower of David or the Citadel. Neither the western hill (mistakenly called Mount Zion) or the Citadel (mistakenly called the Tower of David) bear any relation to the Mount Zion or the Tower of David from the time of King David.

- from Jerusalem - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 2 - Map of Iron Age Jerusalem

from Finkelstein et. al. (2011)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Map of Jerusalem showing the possible location of the supposed mound on the Temple Mount, the City of David and the line of the Iron IIB-C city-wall.

Finkelstein et. al. (2011) - Map of Jerusalem at the

end of the First Temple period from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Map of Jerusalem at the end of the First Temple period

Map of Jerusalem at the end of the First Temple period

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Map of Jerusalem at the

end of the Second Temple period from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Map of Jerusalem at the end of the Second Temple period

Map of Jerusalem at the end of the Second Temple period

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 1.2 - Border between

Benjamin and Judah from Reich and Shukron (2021)

Fig. 1.2

Fig. 1.2

Border between the tribes of Benjamin and Judah

Reich and Shukron (2021)

- Fig. 2 - Map of Iron Age

Jerusalem from Finkelstein et. al. (2011)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Map of Jerusalem showing the possible location of the supposed mound on the Temple Mount, the City of David and the line of the Iron IIB-C city-wall.

Finkelstein et. al. (2011) - Map of Jerusalem at the

end of the First Temple period from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Map of Jerusalem at the end of the First Temple period

Map of Jerusalem at the end of the First Temple period

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Map of Jerusalem at the

end of the Second Temple period from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Map of Jerusalem at the end of the Second Temple period

Map of Jerusalem at the end of the Second Temple period

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 1.2 - Border between

Benjamin and Judah from Reich and Shukron (2021)

Fig. 1.2

Fig. 1.2

Border between the tribes of Benjamin and Judah

Reich and Shukron (2021)

- Annotated old aerial

photograph of The City of David, Silwan, etc. from a now deleted blog post titled "Deciphering Zechariah 14:5"

Annotated Old Photograph showing Silwan, En Rogel, and the City of David (aka the Original City) from a now deleted blog post titled Deciphering Zechariah 14:5.

Annotated Old Photograph showing Silwan, En Rogel, and the City of David (aka the Original City) from a now deleted blog post titled Deciphering Zechariah 14:5.

Note: the original blog post is preserved in the Notes section for the Amos Quakes. - City of David in Google Earth

- City of David on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated old aerial

photograph of The City of David, Silwan, etc. from a now deleted blog post titled "Deciphering Zechariah 14:5"

Annotated Old Photograph showing Silwan, En Rogel, and the City of David (aka the Original City) from a now deleted blog post titled Deciphering Zechariah 14:5.

Annotated Old Photograph showing Silwan, En Rogel, and the City of David (aka the Original City) from a now deleted blog post titled Deciphering Zechariah 14:5.

Note: the original blog post is preserved in the Notes section for the Amos Quakes. - City of David in Google Earth

- City of David on govmap.gov.il

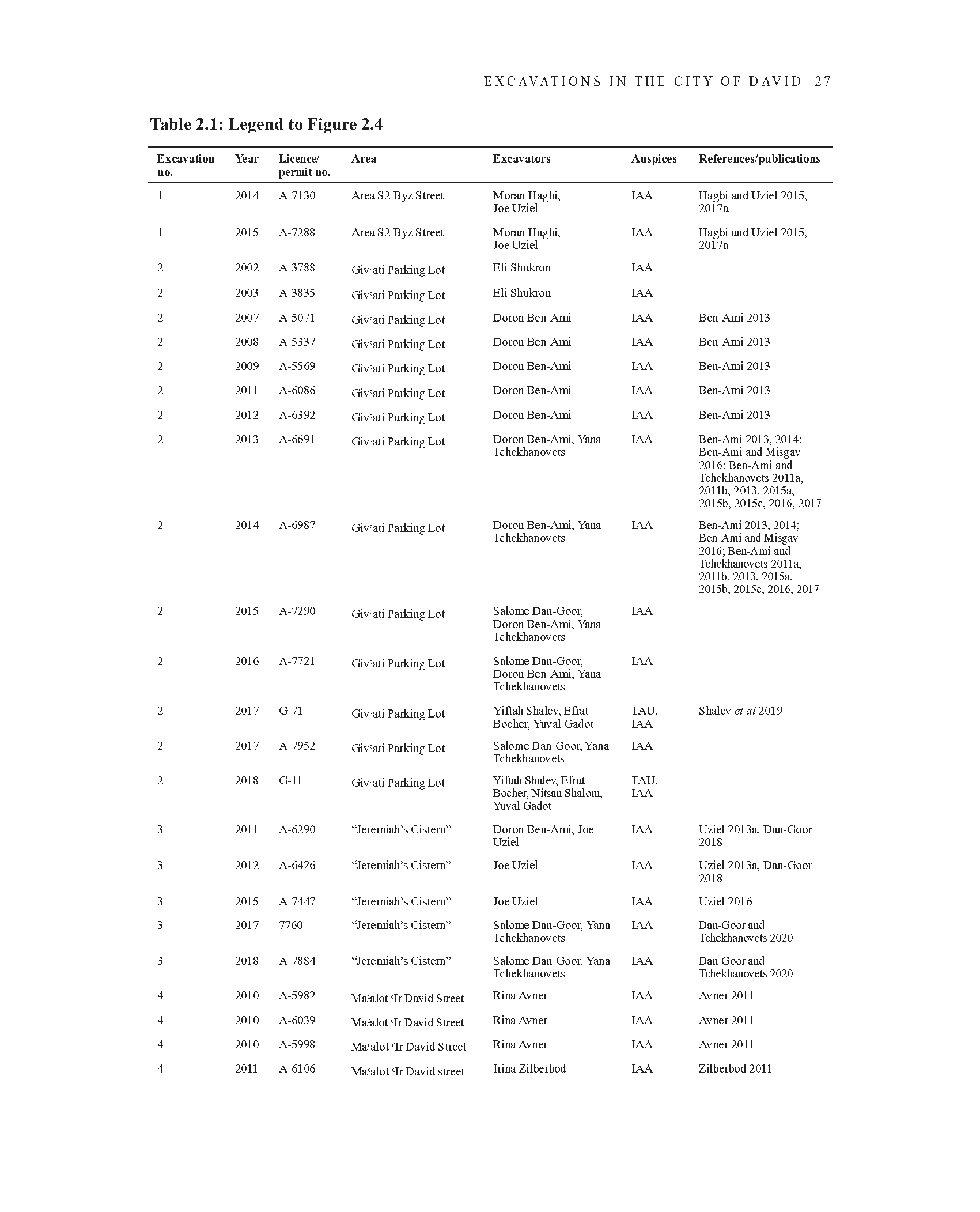

Fig. 2.4

Fig. 2.4Location of the excavation areas on the Southeastern Hill. See appended map.

Reich and Shukron (2021)

- Map of the Excavated Areas

of the City of David from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

City of David: map of the excavated areas

City of David: map of the excavated areas

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 1 - Excavation Areas in the City of David

from Finkelstein et. al. (2011)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the City of David indicating main excavation areas mentioned in the article.

Finkelstein et. al. (2011) - Fig. 1 - Excavation Areas in the City of David

from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the City of David showing the location of the current excavation.

(prepared by J. Uziel)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Fig. 1 - Location Map

showing excavations from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location map showing the topography of the City of David and the areas of Shiloh's excavations.

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Plan of the City of David

around Gihon Spring from Stern et al (2008)

City of David: Plan of the remains around Gihon Spring

City of David: Plan of the remains around Gihon Spring

Stern et al (2008) - Archeological Areas

In Silwan from Shaveh (2017)

Archeological Areas In Silwan

Archeological Areas In Silwan

Shaveh (2017)

- Map of the Excavated Areas

of the City of David from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

City of David: map of the excavated areas

City of David: map of the excavated areas

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 1 - Excavation Areas

in the City of David from Finkelstein et. al. (2011)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the City of David indicating main excavation areas mentioned in the article.

Finkelstein et. al. (2011) - Fig. 1 - Excavation Areas

in the City of David from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the City of David showing the location of the current excavation.

(prepared by J. Uziel)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Fig. 1 - Location Map

showing excavations from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location map showing the topography of the City of David and the areas of Shiloh's excavations.

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Plan of the City of David

around Gihon Spring from Stern et al (2008)

City of David: Plan of the remains around Gihon Spring

City of David: Plan of the remains around Gihon Spring

Stern et al (2008) - Archeological Areas

In Silwan from Shaveh (2017)

Archeological Areas In Silwan

Archeological Areas In Silwan

Shaveh (2017)

- Fig. 1 - Map of Area U in relation to other remains

from Chalaf and Uziel (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location of the excavation in relation to remains found near the Gihon Spring, including Kenyon's walls, the Warren Shaft system and the spring fortifications.

(Israel Antiquities Authority, after Gadot and Uziel 2017: Fig. 2)

Chalaf and Uziel (2018) - Fig. 2 - Plan of the Iron Age II-III remains

discovered in Area U from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Iron Age II-III remains discovered in Area U

(prepared by V. Essman)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

- Fig. 1 - Map of Area U

in relation to other remains from Chalaf and Uziel (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location of the excavation in relation to remains found near the Gihon Spring, including Kenyon's walls, the Warren Shaft system and the spring fortifications.

(Israel Antiquities Authority, after Gadot and Uziel 2017: Fig. 2)

Chalaf and Uziel (2018) - Fig. 2 - Plan of the

Iron Age II-III remains discovered in Area U from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Iron Age II-III remains discovered in Area U

(prepared by V. Essman)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Area E

from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Schematic plan showing the Sub Areas

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Plan 33b -

Plan of Area E South from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 33b

Plan 33b

Area E South, Str. 12B (north)

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Plan 40 - Area E South section

showing fill from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 40

Plan 40

Area E South, section s-s.

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

- Fig. 2 - Plan of Area E

from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Schematic plan showing the Sub Areas

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Plan 33b -

Plan of Area E South from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 33b

Plan 33b

Area E South, Str. 12B (north)

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Plan 40 - Area E South section

showing fill from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 40

Plan 40

Area E South, section s-s.

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

- Fig. 3 - View of Building 17081,

looking north from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

View of Building 17081, looking north.

(photo by J. Uziel)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Fig. 4 - View of fallen stones

overlying vessels in situ, looking north from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

View of fallen stones overlying vessels in situ, looking north

(photo by 0. Chalaf)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Fig. 5 - View of vessels in situ,

looking west from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

View of vessels in situ, looking west

(photo by 0. Chalaf)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Photo 40 - Photo of Area E South

(wide shot) from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Photo 40

Photo 40

The deep drilling carried out in 1987 for the stone wall of the archaeological park south of Area E, looking west.

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Photo 39 - Photo of Area E South

(medium shot) from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Photo 39

Photo 39

General view of Area E South, looking west. (YS).

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Photo of Area E (aka City Walls) by Jefferson Williams

Stratification of the City of David

Stratification of the City of DavidYigal Shiloh in Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Scheme of Strata - City of David Excavations (1978-1985)

Scheme of Strata - City of David Excavations (1978-1985)De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

- Fig. 1 -

Excavation Areas in the City of David from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the City of David showing the location of the current excavation.

(prepared by J. Uziel)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Fig. 1 -

Map of Area U in relation to other remains from Chalaf and Uziel (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location of the excavation in relation to remains found near the Gihon Spring, including Kenyon's walls, the Warren Shaft system and the spring fortifications.

(Israel Antiquities Authority, after Gadot and Uziel 2017: Fig. 2)

Chalaf and Uziel (2018) - Fig. 2 -

Plan of the Iron Age II-III remains discovered in Area U from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan of the Iron Age II-III remains discovered in Area U

(prepared by V. Essman)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

- Fig. 3 -

View of Building 17081, looking north from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

View of Building 17081, looking north.

(photo by J. Uziel)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Fig. 4 -

View of fallen stones overlying vessels in situ, looking north from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

View of fallen stones overlying vessels in situ, looking north

(photo by 0. Chalaf)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Fig. 5 -

View of vessels in situ, looking west from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

View of vessels in situ, looking west

(photo by 0. Chalaf)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

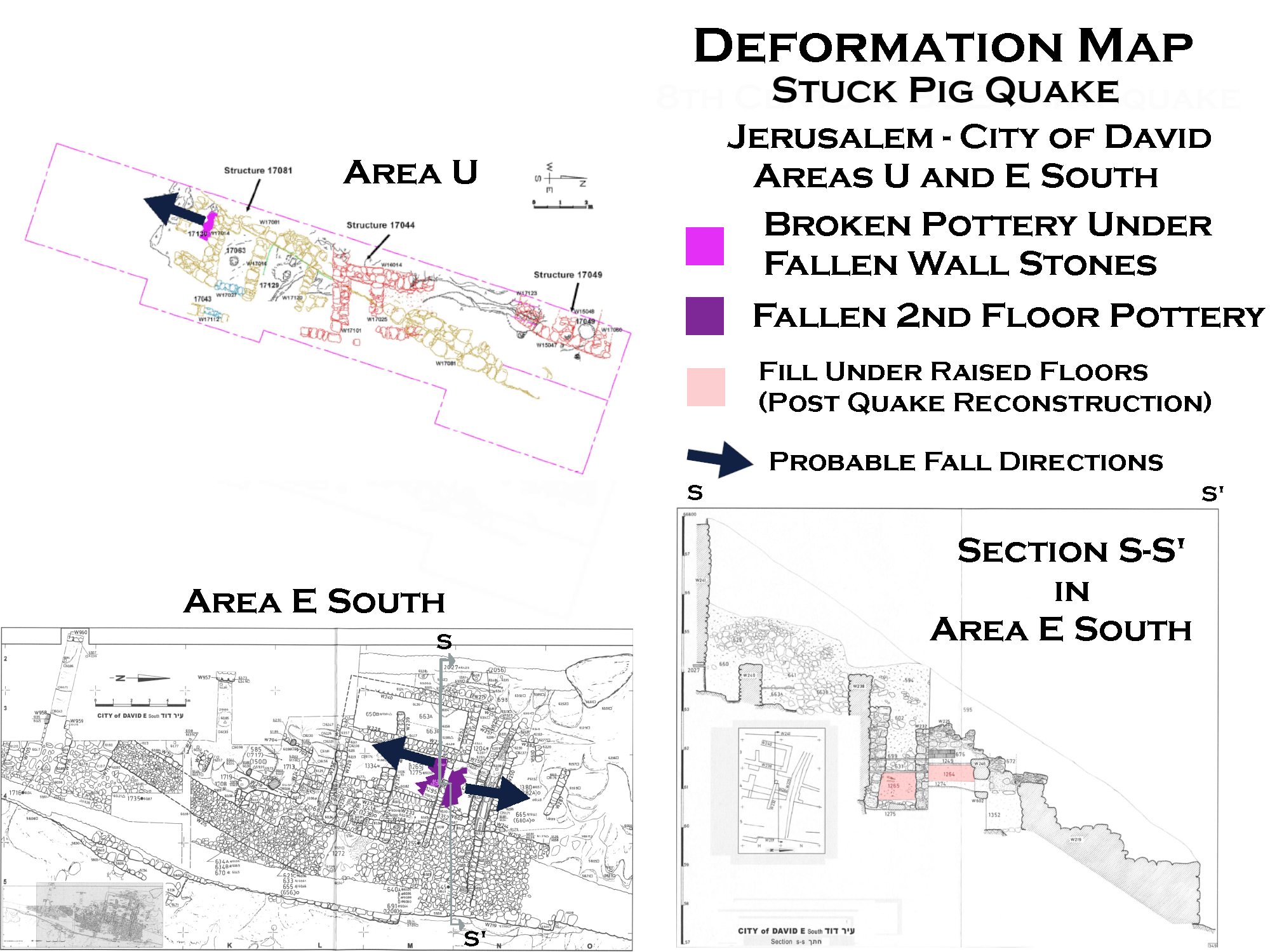

Uziel and Chalaf (2021:55*) discovered what appears to be a seismic destruction layer in the earliest layer of Building 17081 in Area U which they described as follows:

The earliest layer of Building 17081, directly overlying the bedrock, yielded evidence of a destruction layer. Although this layer did not show signs of fire, other factors could be noticed which suggested the building had been damaged in a traumatic event. This was most notable on the earliest floor of the southernmost room (Room 17130). In this room, a row of smashed vessels was uncovered along its northern wall, above which fallen stones had been found (Fig. 4). It appears that these stones were the upper part of the walls of the room, which had collapsed, destroying the vessels which had been set along the wall. The assemblage consisted of a variety of vessel types, including bowls, lamps, large kraters, cooking vessels, holemouths, storage jars and jugs (Figs. 5, 6). Interestingly, the vessels are quite varied, with no two vessels resembling one another. One of the restored vessels is a large krater-barrel with five handles, decorated with a plastic decoration, depicting faces of what seem to be an animal, possibly a bird (Fig. 7).The assemblage includes forms typical of the Iron Age IIB, i.e., eighth century BCE. The assemblage is comparable to Shiloh's Str. 12B (De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg 2012). Of particular interest was the discovery of the complete skeleton of a small pig trapped between the vessels, in upright position, signifying it was not intentionally interred in this location, rather it had found its demise while stuck between the vessels. It appears that whatever catastrophe occurred in this building caught the pig in this room, possibly trying to find its escape (see Sapir-Hen, Chalaf and Uziel 2021).Uziel and Chalaf (2021:54*-55*) described Building 17081 as follows:

The earliest structure (Building 17081) was built directly on a rock step, located just above the rock-cut rooms, exposed by Parker (Vincent 1911) and later by Reich and Shukron (Reich and Shukron 2011), overlying earlier rock-cut installations. The walls of the structure, 50-70 cm thick, were built of medium-size fieldstones. They were preserved to a height of more than 2m above the bedrock (Fig. 3). The current excavation revealed four rooms of this structure, although it is possible that the structure continued to the west, beyond the borders of the excavation. These rooms included three longitudinal rooms (17129, 10063 and 17130 from north to south), and a broad room (17043). The rooms are quite narrow, their width measuring from 0.70 m (17043) to 1.60 m (17129). The lower parts of the walls of 17129 were quarried out of the rock, in a similar fashion to the rock-cut rooms. In the first phase of Building 17081, a doorway was located along its eastern wall (W17027), opposite another doorway in W17112, the western wall of the rock-cut rooms. These doorways were apparently used for passage between the rock-cut rooms and Building 17081. At a later phase, these doorways were blocked and the eastern and the northern rooms were filled with soil and went completely out of use.

In Rooms 17063 and 17130, 10 continuous, superimposed floors were found, the earliest of which belonged to the first phase of the structure, dating to the eighth century BCE, parallel to Stratum 12 of the Shiloh excavations (Shiloh 1984; De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg 2012) and to Stratum 8 of Szanton and Uziel's excavations of Area C (Uziel and Szanton 2015). The seriation of floor levels, with ceramics indicative of the terminal phases of the Iron Age on the uppermost floor, attests to the continuity of use from the eighth century BCE until the Babylonian destruction in 586 BCE (Shalom et al. 2019).

- Fig. 1 -&

Excavation Areas in the City of David from Uziel and Chalaf (2021)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the City of David showing the location of the current excavation.

(prepared by J. Uziel)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021) - Fig. 1 -

Location Map showing excavations from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location map showing the topography of the City of David and the areas of Shiloh's excavations.

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Fig. 2 -

Plan of Area E from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Schematic plan showing the Sub Areas

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Plan 33 -

Plan of Area E South from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 33b

Plan 33b

Area E South, Str. 12B (north)

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Plan 40 -

Area E South section showing fill from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 40

Plan 40

Area E South, section s-s.

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

- Photo 40 -

Photo of Area E South (wide shot) from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Photo 40

Photo 40

The deep drilling carried out in 1987 for the stone wall of the archaeological park south of Area E, looking west.

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) - Photo 39 -

Photo of Area E South (medium shot) from De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Photo 39

Photo 39

General view of Area E South, looking west. (YS).

De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Uziel and Chalaf (2021:60*-61*) re-interpreted evidence from Stratum 12B at the "Terrace House" in Area E South in the City of David. They suggested that vessels that appear to have fallen from the second story of a building may have fallen due to an 8th century BCE earthquake. They also suggested the building was renovated after the Stratum 12B earthquake as evidenced by the placement of 60 cm. of fill underneath the raised floor.

We carefully suggest that the effects of this earthquake were likely felt at other parts of the city as well. Most significant are the detailed descriptions of Y. Shiloh's excavations in Area E, just south of the current excavation area. The comprehensive report published by De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) details events which seem comparable to the findings in Area U. Of particular importance is the excavation of the "Terrace House" in Area E South. Here several pieces of evidence would suggest a destructive event, despite the fact that the excavators did not define a destruction for Str. 12B. Most notable are two assemblages that yielded restored vessels. The first was found in Room 1274 which yielded an assemblage of some 10 complete vessels. The second, found in the adjacent room, is described as having collapsed from the upper story of the building (De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg 2012: 52). The floors of the building were raised by a significant fill of some 60 cm (ibid.: Plan 40), which likely served the renovation of the building after its Str. 12B collapse.De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012:52) described the fallen pottery as follows:

Stratum 12B (Plan 33)

The Middle Zone

...The ceramic assemblage of floor L1275 included bowls, jugs, a lamp, haters, cooking pots, and storage jars (Vol. VIIB, Figs. 4.27, 4.28). The vessels were restored with pottery deriving from fill L1265, which overlay the floor, and it is particularly noteworthy that a cooking pot (Vol. VIIB, Fig. 4.28:2) was restored with a potsherd from Basket 5877 from L640D, a floor at elevation 60.60 m east of W233. This implies that at least part of the pottery from L1275 originated on the second story, which collapsed at some point, pitching the pottery into the two lower rooms.

- from Chat GPT 4o, 31 July 2025

- from Steiner (2022)

The article contains detailed architectural descriptions, recovery of luxury and utilitarian finds, and context for the final phases of occupation. None of the reported observations mention structural collapse patterns, deformation, or diagnostic seismic effects such as tilted walls, fallen masonry, or rapid debris deposition consistent with earthquake damage.

The destruction is consistently interpreted as the result of military assault and not of natural seismic activity. Therefore, this report provides no archaeoseismic evidence, either primary or indirect, for the Iron Age II destruction levels at the site.

| Effect | Location | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Room 17130 in Area U

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Plan of the Iron Age II-III remains discovered in Area U (prepared by V. Essman) Uziel and Chalaf (2021) |

Figure 4

Fig. 4

Fig. 4View of fallen stones overlying vessels in situ, looking north (photo by 0. Chalaf) Uziel and Chalaf (2021) Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Fig. 5View of vessels in situ, looking west (photo by 0. Chalaf) Uziel and Chalaf (2021) |

|

|

Room 1274 and adjacent room in the "Terrace House" in Area E south

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Schematic plan showing the Sub Areas De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 33b

Plan 33bArea E South, Str. 12B (north) De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 40

Plan 40Area E South, section s-s. De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 2 of Uziel and Chalaf (2021) and Plans 33b and 40 of De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Room 17130 in Area U

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Plan of the Iron Age II-III remains discovered in Area U (prepared by V. Essman) Uziel and Chalaf (2021) |

Figure 4

Fig. 4

Fig. 4View of fallen stones overlying vessels in situ, looking north (photo by 0. Chalaf) Uziel and Chalaf (2021) Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Fig. 5View of vessels in situ, looking west (photo by 0. Chalaf) Uziel and Chalaf (2021) |

|

|

|

Room 1274 and adjacent room in the "Terrace House" in Area E south

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Schematic plan showing the Sub Areas De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 33b

Plan 33bArea E South, Str. 12B (north) De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012)

Plan 40

Plan 40Area E South, section s-s. De Groot and Bernick-Greenberg (2012) |

|

|

Chalaf O. and Uziel J., 2018, Beyond the Walls: New Findings on the Eastern Slope of the City of David and their

Significance for Understanding the Urban Development of Late Iron Age Jerusalem, in E. Meiron (ed.), City of David Studies of Ancient Jerusalem 13: 17*-32*.

Dan-Goor S., 2017 Jerusalem, City of David, Preliminary Report, Hadashot Arkheologiyot 129.

De Groot A. and Bernick-Greenberg H., 2012, Excavations at the City of David 1978-1985 directed by Yigal Shiloh VII, TEXT (Qedem 53), Jerusalem.

De Groot A. and Bernick-Greenberg H., 2012, Excavations at the City of David 1978-1985 directed by Yigal Shiloh VII, PLANS (Qedem 53), Jerusalem.

Finkelstein, I., Koch, I., and Lipschits, O. 2011. The Mound on the Mount: A Solution to the “Problem with Jerusalem”. Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 11.

Finkelstein, I. (2022) The Iron Age Complex in the Ophel, Jerusalem: A Critical Analysis

. Tel Aviv 49(2): 191-204.

Hagbi M. and Uziel J., 2017, Jerusalem, City of David, Shalem Slopes, Hadashot Arkheologiyot 129.

Steiner, Margeret (2022) A Closer Look: The Houses on the Southeastern Hill of Jerusalem in Economic Perspective

, in “No Place Like Home: Ancient Near Eastern Houses and Households"

Edited by Laura Battini, Aaron Brody, Sharon R. Steadman, Archaeopress, p. 181-194.

Uziel, J., and Chalaf, Ortal (2021). "Archaeological Evidence of an Earthquake in the Capital of Judah." City of David Studies of Ancient Jerusalem.

Uziel, J. and Szanton, N. (2015) Recent Excavations Near the Gihon Spring and Their Reflection on the Character of Iron II

Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, 42:2, 233-250

Vukosavović, F., Uziel. J, and Chalaf, O. (2021) Jerusalem, City of David Preliminary Hadashot Arkheologiyot 133

City of David website

Traveler's Map - CityOfDavid.org

Ancient Silwan (Shiloah) [Siloam] in Israel and The City of David

- contains excellent old photographs

City of David at BibleWalks.com

The City of David Excavations Final Reports (Excavations at the City of David 1978–

1982) [Y. Shiloh Excavations], 1: Interim Report of the First 5 Seasons (Qedem 19; ed. Y. Shiloh), Jerusalem

1984

2: Imported Stamped Amphora Handles, Coins, Worked Bone and Ivory, and Glass (Qedem 30

ed.

D. T. Ariel), Jerusalem 1990

ibid. (Review) PEQ 126 (1994), 71–72

3: Stratigraphical Environmental, and

Other Reports (Qedem 33

eds. A. de Groot & D. T. Ariel), Jerusalem 1992

ibid. (Reviews) AJA 98 (1994),

569–570. — PEQ 126 (1994), 74–75. — Bibliotheca Orientalis 52 (1995), 800–803

4: Various Reports

(Qedem 35

eds. D. T. Ariel & A. de Groot), Jerusalem 1996

ibid. (Reviews) BASOR 309 (1998), 84–85.

— Levant 30 (1998), 221. — ZDPV 114 (1998), 190–193. — PEQ 131 (1999), 193. — JNES 59 (2000),

299–303

5: Extramural Areas (Qedem 40

eds. D. T. Ariel et al.), Jerusalem 2000

ibid. (Reviews) LA 50

(2000), 587–589. — BASOR 321 (2001), 85–86. — ZDPV 118 (2002), 87–92. — JNES 62 (2003), 209–210;

6: Inscriptions (Qedem 41

ed. D. T. Ariel), Jerusalem 2000

ibid. (Reviews) LA 50 (2000), 590–591. —

BASOR 323 (2001), 100–101. — ZDPV 118 (2002), 92–99

Z. Abells & A. Arbit, The City of David Water

Systems, Jerusalem 1995

In Search of the Temple Treasures: The Story of the Parker Expedition 1909–1911,

Jerusalem 1998 (Heb.)

The City of David: Discoveries from the Excavations (ed. G. Hurvitz), Jerusalem

1999

Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period (Society of Biblical Literature Symposium Series 18

eds. A. G. Vaughn & A. E. Killebrew), Leiden 2003

The City of David: Revisiting Early

Excavations (ed. H. Shanks

archaeological commentary: R. Reich), Washington, DC 2004

G. Gilmour, The

1923–1925 P.E.F. Excavations at the City of David, Jerusalem, Final Report (in prep.).

M. Broshi, Les Dossiers d’Archéologie (Special Issue) March 1992, 16–23

R. L. Chapman, III,

PEQ 124 (1992), 4–8: H. J. Franken (& M. L. Steiner), ZAW 104 (1992), 110–111

id., Leiden University,

Dept. of Pottery Technology Newsletter 14–15 (1996–1997), 19–23

D. C. Liid, ABD, 6, New York 1992,

183–184

A. M. Maeir, OJA 11 (1992), 39–54

A. Mazar, Les Dossiers d’Archéologie (Special Issue) March

1992, 24–31

id., New Studies on Jerusalem 10 (2004), 43*–44*

D. Tarler (& J. M. Cahill), ABD, 2, New

York 1992, 52–67

A. D. Tushingham, BASOR 287 (1992), 61–65

BH 30 (1993), 30–31

J. P. Floss, ZionOrt der Begegnung (L. Klein Fest.

eds. F. Hahn et al.), Bodenheim 1993, 413–437

J. -L. Huot, RA 1993/1

116–117 (Review)

K. Prag, Levant 25 (1993), 224–226 (Review)

B. Sass, Studies in the Archaeology and

History of Ancient Israel, Haifa 1993, 22*

M. L. Steiner, BAT II, Jerusalem 1993, 585–588

id., Bibliotheca

Orientalis 50 (1993), 250–252 (Review)

id., IEJ 44 (1994), 13–20

id., New Studies on Jerusalem 2 (1996),

3–8

id., Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 11 (1997), 16–28

12 (1998), 26–33, 62–63

id., Currents in Research: Biblical Studies 6 (1998), 143–168

id., Studies in the Archaeology of the Iron Age in

Israel and Jordan, Sheffield 2001, 280–288

id., Jerusalem in Ancient History and Tradition (JSOT Suppl.

Series 381

Copenhagen International Seminar 13

ed. T. L. Thompson), Sheffield 2003, 68–79

Y. Billig,

ESI 14 (1994), 96–97

110 (1999), 62*

J. M. Cahill (& D. Tarler), Ancient Jerusalem Revealed: Archaeology in the Holy City 1968–1974 (ed. H. Geva), Jerusalem 1994, 31–45

id., BAR 23/5 (1997), 48–57

24/4

(1998), 34–41, 63

30/6 (2004), 20–31, 62–63

id., New Studies on Jerusalem 7 (2001), 6*–7*

id., Jerusalem

in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period (Society of Biblical Literature Symposium Series 18;

eds. A. G. Vaughn & A. E. Killebrew), Leiden 2003, 13–80

id., ASOR Annual Meeting 2004, www.asor.org/

AM/am.htm

G. Finkielsztejn, PEQ 126 (1994), 71–72 (Review)

D. Gill, BAR 20/4 (1994), 20–33, 64

T. J.

Kleven, ibid., 34–35

S. B. Parker, ibid., 36–38

T. Schneider, Ancient Jerusalem Revealed: Archaeology in

the Holy City 1968–1974 (ed. H. Geva), Jerusalem 1994, 62–63

Y. Shoham, ibid., 55–61

id., EI 26 (1999),

234*

F. Zayadine, Levant 26 (1994), 225–229 (Review)

Z. Abells & A. Arbit, PEQ 127 (1995), 2–7

H.

Shanks, BAR 21/1 (1995), 59–67

25/6 (1999), 20–35

26/5 (2000), 38–41

29/3 (2003), 52–58

31/5 (2005),

16–23

D. Bahat, Royal Cities of the Biblical World (Bible Lands Museum

ed. J. Goodnick Westenholz),

Jerusalem 1996, 287–306 (with G. Hurvitz), 307–326

D. Gavron, Ariel, Eng. Series 102 (1996), 6–12

A. De

Groot, ESI 15 (1996), 75–77

id., New Studies on Jerusalem 7 (2001), 7*, 9*

10 (2004), 49*–50*

A. R. Millard, BH 32 (1996), 71–74

J. Murphy-O’Connor, Holy Land 16 (1996), 59–62

K. Reinhard & P. Warnock,

Illness and Healing in Ancient Times (Reuben and Edith Hecht Museum Catalogue 13), Haifa 1996, 20–23;

“Schatzhaus”-Studien (Kamid el-Luz 16

Saarbrücker Beiträge zur Altertumskunde 59

ed. R. Hachmann),

Bonn 1996, 228–241

N. Avigad, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals (Publications of the Israel Academy

of Sciences and Humanities, Section of Humanities

rev. B. Sass), Jerusalem 1997

E. Mazar, BAR 23/1

(1997), 50–57, 74

H. J. Muszynski, Jerozolima w Kulturze Europejskiej (eds. P. Paszkewicz & T. Zadrozny),

Warszawa 1997, 27–33

N. Na’aman, BAR 24/4 (1998), 42–44

id., Biblica 85 (2004), 245–254

A. E. Shimron et al., New Studies on Jerusalem 4 (1998), iii–xvi

id., BAR 30/4 (2004), 14–15

D. Barag, EI 26 (1999),

227–228*

E. Eisenberg & A. De Groot, ibid., 5*

E. A. Knauf, TA 27 (2000), 75–90

F. M. Cross, Jr., IEJ 51

(2001), 44–47

Wasser im Heiligen Land: Biblische Zeugnisse und Archäologische Forschungen (Schriftenreihe der Frontinus Gesellschaft Suppl 3

ed. W. Dierx), Mainz am Rhein 2001, 153–158

P. Beck, Imagery

and Representation, Tel Aviv 2002, 423–427

A. Faust, BAR 29/5 (2003), 70–76

I. Finkelstein, MdB 148

(2003), 21–24

J. K. Hoffmeier, Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period (Society of

Biblical Literature Symposium Series 18

eds. A. G. Vaughn & A. E. Killebrew), Leiden 2003, 285–289

L.

Tatum, ibid., 291–306

C. Arnould-Béhar, Transeuphraténe 28 (2004), 33–39

G. Davies, Ancient Hebrew

Inscriptions, 2: Corpus and Concordance, Cambridge 2004, 1–10, 27–29

L. J. Mykytiuk, Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200–539 B.C.E. (Society of Biblical Literature Academia

Biblica 12), Atlanta, GA 2004, 139–152

J. Yellin & J. M. Cahill, IEJ 54 (2004), 191–213

E. Lefkovitz,

Artifax 20/3 (2005), 1, 3

20/4 (2005), 4

O. Lipschitz, The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: The History of Judah

Under Babylonian Rule, Winona Lake, IN 2005 (index)

D. Ussishkin, BAR 31/4 (2005), 26–35.

Excavations by K. M. Kenyon in Jerusalem 1961–1967, 3: The Settlement in the Bronze

and Iron Ages (Copenhagen International Series 9

ed. M. L. Steiner), Sheffield 2001

ibid. (Review) BAR

29/3 (2003), 52–58, 70

4: The Iron Age Cave Deposits on the South-East Hill and Isolated Burials and

Cemeteries Elsewhere (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology 6

eds. I. Eshel & K. Prag), Oxford

1995

ibid (Reviews) BAR 22/4 (1996), 17–18. — AJA 101 (1997), 170–171. — BASOR 306 (1997), 92–94.

— AfO 44–45 (1997–1998), 516–520. — PEQ 130 (1998), 51–62. — JNES 62 (2003), 308–310

H. J.

Franken, A History of Pottery and Potters in Ancient Jerusalem: Excavations by K. M. Kenyon in Jerusalem

1961–1967, London 2005

K. Prag, On Scrolls, Artefacts and Intellectual Property (Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha, Suppl. Series 38

eds. T. H. Lim et al.), Sheffield 2001, 223–229

P. R. S. Moorey, Idols of the People:

Miniature Images of Clay in the Ancient Near East (The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy 2001),

Oxford 2003, 52–58

M. Steiner, Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period (Society of

Biblical Literature Symposium Series 18

eds. A. G. Vaughn & A. E. Killebrew), Leiden 2003, 347–363.

R. Reich, EI 19 (1987), 83*

id., IEJ 37 (1987), 158–167

id., ASOR Annual Meeting Abstract Book, Boulder,

CO 2001, 30

id., Journal of Israeli History (in press)

R. Reich & E. Shukron, ESI 18 (1998), 91–92

19

(1999), 60*–61*

20 (2000), 99*–9100*

109 (1999), 77*–78*

110 (1999), 63*–64*

112 (2000), 82*–83*;

113 (2001), 81*–82*

114 (2002), 77*–78*

115 (2003), 51*–53*

id., BAR 25/1 (1999), 22–33, 72

id.,

Ancient Jerusalem Revealed, repr. & exp. ed. (ed. H. Geva), Jerusalem 2000, 327–339

id., New Studies

on Jerusalem 6 (2000), 5*

id., RB 107 (2000), 5–17

id., The Armenians in Jerusalem and the Holy Land

(Hebrew University Armenian Studies 4

eds. R. R. Ervine et al.), Leuven 2002, 195–203

id., BASOR 325

(2002), 75–80

id., Cura Aquarum in Israel, Siegburg 2002, 1–6

id., EI 27 (2003), 291*

id., Jerusalem in

Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period (Society of Biblical Literature Symposium Series 18

eds.

A. G. Vaughn & A. E. Killebrew), Leiden 2003, 209–218

id., PEQ 135 (2003), 22–29

id., ZDPV 119 (2003),

12–18

id., Levant 36 (2004), 211–224

id., Journal of Israeli History (in press)

id., Levant 36 (2004),

211–223

id., A. Mazar Fest. (eds. A. Maeir & P. de Miroschedji), Ramat Gan (in press)

D. Pardee, OEANE,

5, New York 1997, 41

E. Shukron & R. Reich, New Studies on Jerusalem 6 (2000), 5*

E. Meiron, Cura

Aquarum in Israel, Siegburg 2002, 7–13

BAR 29/6 (2003), 18

A. Faust, BAR 29/5 (2003), 70–76

A. Frumkin et al., Nature 425, 11.9.2003, 169–171

A. E. Killebrew, Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First

Temple Period (Society of Biblical Literature Symposium Series 18

eds. A. G. Vaughn & A. E. Killebrew),

Leiden 2003, 329–345

Science News 164/14 (2003), 221

R. Bouchnik et al., New Studies on Jerusalem 10

(2004), 50*

H. Shanks, BAR 31/5 (2005), 16–23.

D. Ussishkin, The Village of Silwan, Jerusalem 1993

ibid. (Reviews) Bibliotheca Orientalis 52 (1995),

803–807. — PEQ 127 (1995), 83–84. — Syria 72 (1995), 281–283. — JNES 58 (1999), 220–222

S. Rosenberg, The Siloam Tunnel Revisited (M.A. thesis), London 1996

- Excavators Joe Uziel and Ortal Chalaf describing evidence of 8th cent. BCE earthquake in Area F

- from youtube

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master Jerusalem kmz file | various |