Gezer

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Gezer or Tel Gezer | Hebrew | גֶּזֶר |

| Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari | Arabic | تل الجزر |

| Ga-az-ru | Assyrian Akkadian | |

| Gazara | ||

| Gadara ? | Josephus |

Gezer is located in the Shephelah - a transition region between the Judean Mountains and the coastal plain. Roughly halfway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, it had a long history of occupation starting at least at the end of the 4th millennium BCE in the Chalcolithic. Although there were later occupations, it's heyday appears to have ended in the Iron Age ( William J. Dever in Stern et al, 1993 v. 2).

The earliest mention of the site is in an inscription of Thutmose III (c. 1490- 1436 BCE) on the walls of the great Temple of Amon at Karnak. There, a scene commemorating this pharaoh's victories on his first campaign to Asia in 1468 BCE portrays bound captives from Gezer. A short inscription of Thutmose IV (c. 1410-1402 BCE) in his mortuary temple at Thebes refers to Hurrian captives from a city, the name of which is broken but is almost certainly Gezer. During the tumultuous Amarna period, in the fourteenth century BCE, Gezer figures prominently among Canaanite city-states under nominal Egyptian rule. In the corpus of the el-Amarna letters are ten from three different kings of Gezer. Perhaps the best-known Egyptian reference to Gezer is that of Merneptah (c. 1207 BCE) in his "Israel" stela, in which it is claimed that Israel has been destroyed and Gezer seized. The conquest of Gezer is also celebrated in another inscription of this pharaoh, found at Amada.

A relief of Tiglath-pileser III, king of Assyria (c. 745-728 BCE), found on the walls of his palace at Nimrud, depicts the siege and capture of a city called Ga-az-ru. This is undoubtedly Gezer in Canaan, and the background would be the campaign of the Assyrian monarch in Philistia in 734-733 BCE. References to Gezer in the Bible itself are not as numerous as might be expected. However, that simply reflects the reality that, on the one hand, Gezer had already passed the peak of its power by the Iron Age and that, on the other, it lay on the periphery of lsrael's effective control until rather late in the biblical period. In the period of the Israelite conquest, it is recorded that the Israelites under Joshua met a coalition of kings near Gezer in the famous Battle of Makkedah, in the Ayalon Valley. Although Horam, the king of Gezer, was killed, the text does not say specifically that Gezer itself was captured (Jos. 10:33, 12:12). Later, according to several passages, "Gezer and its pasture lands" were allotted to the tribe of Joseph (or "Ephraim", cf. Jos. 16:3, 10; Jg. 1:29; 1 Chr. 6:66, 7:28). However, the footnote that the Israelites "did not drive out the Canaanites, who dwelt in Gezer" makes it clear that the Israelite claim was more imaginary than real. Gezer was also set aside as a Levitical city (Jos. 21:21), but again it is unlikely that it was actually settled by Israelites. The same ambiguity is reflected in several references to David's campaigns against the Philistines, where Gezer is usually regarded as in the buffer zone between Philistia and Israel, although it is implied that it was actually the farthest outpost of Philistine influence (2 Sam. 5:25; 1 Chr. 14:16, 20:4). The most significant biblical reference to Gezer - and now confirmed as the most reliable historically - is 1 Kings 9:15-17, where it is recorded that the city was finally ceded to Solomon by the pharaoh as a dowry in giving his daughter to the Israelite king in marriage. Thereafter, Solomon fortified Gezer, along with Jerusalem, Megiddo, and Hazor.

There are no further references until post-biblical literature, in which Gezer appears to have played a significant role in the Maccabean wars. The Seleucid general Bacchides fortified Gezer (by then known as Gazara) along with a number of other Judean cities (1 Macc. 9:52). In 142 BCE, Simon Maccabaeus besieged Gezer and took it, after which he refortified it and then built himself a residence there (1 Macc. 13:43;--48). His son, John Hyrcanus, made his headquarters at Gezer when he became commander of the Jewish armies the next year (1 Macc. 13:53).

- from Webster et al. (2023:2-4)

- Number in brackets refer to references in Webster et al. (2023)'s paper

Gezer was well-known to the Egyptians since at least the 18th Dynasty. During the 15th century BC, this town appears in the topographic list of Thutmose III, and Thutmose IV claims to have captured Hurrians nearby [1]. The chronology of these rulers is supported by radiocarbon dating, with accession years estimated in the range 1518–1501 BC and 1434–1420 BC respectively (95.4% probability) [2–4]. By the 14th century BC, Gezer was one of the dominant city-states in central-southern Canaan, its rulers featuring prominently in the Amarna correspondence [5, 6]. Towards the end of the Late Bronze Age, Merneptah (accession 1241–1219 BC, 95.4%) launched a campaign into southern Canaan, evidently to quell a rebellion that broke out at the end of Ramesses II’ long reign [7, 8]. Gezer is one of few sites singled out as having been captured. In his stele we read:

“Carried off is Canaan with every evil, Brought away is Ascalon, taken is Gezer, Yenoam is reduced to non-existence; Israel is laid waste having no seed.” [9]The historicity of Merneptah’s southern Levantine campaign and his attack on Gezer (dated to his 5th year) enjoys wide acceptance [10]. Further evidence comes from the Amada Stela, where the king proudly titles himself as the “subduer of Gezer” [9] and the event may even be depicted in a battle relief at Karnak [11].

Whether the biblical text preserves memories of Gezer as a prominent Canaanite centre is debated [12, 13]. The Bible is a major source for the Iron Age southern Levant, and though written down centuries later, most scholars consider that it reflects some early realities. The overall evidence suggests that by the early Iron Age, Gezer lay at the border between emerging coastal and highland polities and was a frontier for conflict: “there arose a war with the Philistines at Gezer” (1 Chr. 20:4; see also 2 Sam. 5:25 and 1 Chr. 14:16).

During the timeframe of the debated ‘United Monarchy’, Gezer appears in several intriguing texts. 1 Kings 9:15–17 mentions Gezer’s capture, burning and presentation as a wedding gift by Solomon’s father-in-law–an unnamed Egyptian king; it then claims that Solomon proceeded to build up Gezer, along with Megiddo, Hazor and other towns. Scholarly views vary regarding the composition and redaction of this text and the mix of early and/or later realities reflected (e.g. [14–16]). For those who would see a historical capture of Gezer during the 10th century BC, Siamun of the 21st Dynasty has most often been suggested as the unnamed king [17–20].

Sheshonq I, the Libyan founder of the 22nd Egyptian dynasty (accession 988–945 BC, 95.4%), left a toponym list and triumphal relief at Karnak that includes many southern Levantine sites; toponym no. 11 or 12 may be Gezer, though there are alternate readings (Makkedah and Gaza respectively) [19, 21–27]. While the textual and archaeological evidence does not support viewing the Karnak relief simply as a list of sites attacked or destroyed by Sheshonq I [25], most scholars consider that a campaign into the southern Levant did occur, perhaps partly (or primarily?) aimed at disrupting or controlling the copper trade [28–30].

Sheshonq I is commonly equated with biblical “Shishak king of Egypt”, who is described as attacking Jerusalem in the 5th regnal year of Solomon’s son Rehoboam (1 Kings 14:25–26; 2 Chron. 12:2–9) [19–32]. If the rulers are indeed equivalent, and an attack on Jerusalem historical, then Gezer likely also came under pressure since it guards the western end of the main route leading up to Jerusalem [32, 33].

The last major reference to Gezer during the Iron Age occurs in contemporary Assyrian sources: a siege of Gezer (Ga-az-ru) by Tiglath-pileser III, dated by textual evidence to 734 BC, is depicted in a palace relief at Nimrud [34–36].

- from Webster et al. (2023:4-7)

- Number in brackets refer to references in Webster et al. (2023)'s paper

Fig 2.

Fig 2.Location of the Tandy excavation relative to previous archaeological fieldwork at Gezer.

Image adapted from [41] (front plan) under a CC BY license, with permission from J. Seger, original copyright 2013.

Webster et al. (2023)

Figure 2

Gezer has been the subject of archaeological fieldwork for over a century, with many parts of the site investigated (Fig 2). Macalister was the first to excavate (1902–1909) [37], but his rudimentary excavation methods seriously limit our ability to integrate the findings into a reconstruction of the site’s history [38]. This is unfortunate, since he excavated nearly 60% of the tell – a fact that leaves few locations available to modern excavators. Nonetheless, Macalister exposed a number of key structures that should be associated with the Late Bronze and Iron Age cities. These include portions of city gates and fortification walls along the southern edge of the site, in the saddle area between Gezer’s western and eastern mounds [37, 39, 40].

Following projects of limited scope by Weill in 1912–1913 and 1923–1924 [42], and Rowe in 1934 [43–45], the next expedition to undertake extensive excavation, this time using careful stratigraphic methods, was by Hebrew Union College (HUC) under the direction of Wright, Dever, Lance and Seger between 1964 and 1974. Remains of the late LBA and Iron Age were explored particularly in Fields II [46, 47], Field III [48, 49], Field VI [50] and Field VII [51, 52]. In the saddle area, Field VII presented the most detailed Iron Age sequence, while Iron II fortification systems and part of an administrative building were explored in Field III. Exploration of features initially exposed but misdated by Macalister revealed six- and four-chambered city gates and a casemate wall.

Dever returned to Gezer for two additional seasons in 1984 and 1990 in an effort to clarify the date of the ‘Outer Wall’ and lower gateway, and to explore the Iron II administrative building west of the six-chambered gate in Field III [53–57].

Fieldwork at Gezer was renewed between 2006 and 2017 by Ortiz and Wolff, focused on creating a wide exposure of the Iron Age city between HUC Fields VII and III (Fig 3). Ten seasons of excavation under the auspices of the Tandy Institute of Archaeology (Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary) revealed continuous occupation through three strata of the late LBA to Iron I and four of Iron II (cf. [58–61], final publication in preparation) (Table 1). The plans attest to the changing nature of activity near the city gate–sometimes domestic and at other times administrative. Earlier periods (LBA–Iron I) were represented mainly in the western portion of the excavated area, and Iron II in the east. For convenience, the excavation project is referred to throughout this article as the Tandy expedition, but note that during the publication phase the project was moved to the Lanier Center for Archaeology at Lipscomb University.

From 2010–2018, an excavation by Warner, Yannai and Tsuk under the auspices of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary (NOBTS) and the Israel National Parks Authority (INPA) revisited Field IV and the adjacent water system. The main goal was to re-expose the water system (previously known to Macalister), clarifying its date (now considered MBA) and how it functioned [62, 63].

Throughout this article, site-wide strata are denoted with Roman numerals and those of single excavation fields with Arabic numerals. The latter refer to the Tandy Expedition except where otherwise specified.

Gezer’s archaeology has played a significant role in many debates related to the chronology of the southern Levant during the late LBA through Iron Age (Table 2). Key issues at Gezer that have remained unclear until recently include:

- The extent and date of destruction at the end of the LBA, which the excavators suggest may be associated with Merneptah. HUC attributed limited burnt remains and smashed pottery in Field II and large-scale trenching in Field VI (the acropolis) with Stratum XV and the end of the LBA [47, 50]; much clearer evidence has now come from the excavations of the Tandy expedition. Still, our ability to securely set the absolute date of the destruction and test the viability of potential historical correlations using solely pottery and finds is severely limited.

- The chronology of so-called ‘Philistine’ material culture [2, 64–72]. Gezer is not a core Philistine-related site, but characteristic pottery appears quite suddenly in Stratum XIII, making up 5% of the relevant pottery assemblage in Fields VI [50] and the Tandy excavation. It first occurs as Philistine 2 (Bichrome) ware, and no indisputable examples of Philistine 1 (Monochrome) are known ([73, 74] contra [75]). A single sherd of Philistine 1 has been identified in the Tandy excavation (S. Gitin, personal communication). Determining the absolute chronology of when ‘Philistine’ influence first reached Gezer is of considerable interest, since it could enhance our understanding of social interactions during the LBA to Iron Age transition.

- The date of the ‘Outer Wall’ and lower gateway to either the LBA or Iron Age [55–57, 76– 82]. The existence or lack of a fortification system at Gezer during the LBA has been vigorously debated, and fortification during the early Iron Age was also unclear until the Tandy expedition.

- The date and political association of monumental building activity in Stratum VIII, with its casemate wall, six-chambered gate and large administrative building. This marked change at Gezer was traditionally dated to the 10th century BC [49, 53–55, 59–61], the gate initially featuring in chronological discussions due to Yadin’s association of six-chambered gates at Gezer, Hazor and Megiddo with 1 Kings 9:15 and Solomonic building activity [39]. The now well-recognised wide distribution of such gates shows that the style was not restricted to a particular kingdom nor were they necessarily built at the same time [83, 84]. Following a low chronology for the Iron I to IIA transition, Finkelstein and others dated Stratum VIII to the 9th century BC and suggested associating it with the northern Israelite kingdom under the Omride dynasty [81, 85–88]. Recent intense archaeological research in the Shephelah shows Gezer Stratum VIII to be part of a pattern indicative of political expansion. Various models have been proposed, and the phenomena is usually seen as the result of westward expansion by Judah or polities based in Jerusalem or the Benjamin plateau [89–93].

- The date and possible historical association for the destruction of Stratum VIII. HUC and the Tandy expedition placed the destruction in the second part of the 10th century BC, drawing an association with Shishak / Sheshonq I. A low chronology scenario, on the other hand, would put the event well inside the 9th century BC, and Finkelstein has suggested associating it with the ca. 830 BC campaign of the Aramaean ruler Hazael [75].

Table 2

Table 2Iron Age chronology of the southern Levant

Webster et al. (2023)

Table 2

The first intensive exploration of Tel Gezer was conducted by R. A. S. Macalister during the years 1902–1905 and 1907–1909, under the auspices of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF). Macalister published the results of these early excavations in three volumes (1912). Macalister excavated nearly 40 percent of the tel. Unfortunately, the methods of excavation were very primitive, as Macalister dug the site in strips and backfilled each trench. As a result of his excavations, he distinguished eight levels of occupation.

The next excavator at Gezer was Raymond-Charles Weill, known for his excavations in Jerusalem before and after World War I (1913–1914 and 1923–1924) under the patronage of Baron Rothschild. In 1914 and again in 1924, Weill excavated lands around Tel Gezer that had been acquired by Baron Rothschild. Not much was reported on these excavations until a recent publication by Aren Maeir (2004). In 1934, renewed excavations were conducted under the direction of Alan Rowe under the auspices of the Palestine Exploration Society. This excavation was terminated after a short season. Only preliminary reports were produced, but the data from the excavation is available at the offices of the Palestine Exploration Fund and the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The American Gezer Project began in 1964 under the auspices of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion and the Harvard Semitic Museum, with Nelson Glueck and Ernest Wright as advisors. William G. Dever led the Phase I excavations (1964–1971) of the HUC-Harvard excavations. Phase II was led by Joe D. Seger (1972–1974). These excavations distinguished twenty-one stratigraphic levels from the Late Chalcolithic to the Roman period. Currently, five large final report volumes have been produced (Dever, Lance, and Wright 1970; Dever 1974; Gitin 1990; Dever, Lance, and Bullard 1986; and Seger, Lance, and Bullard 1988), with two more on the small finds and the Middle Bronze Age fortifications of Field IV in advanced stages of publication. Two additional seasons by Dever were conducted in 1984 and 1990.

The main results of Phase I were

- redating the city defenses such as Macalister’s “inner wall, “outer wall,” and the “Maccabean castle”

- dating the famous “high place”

- clarifying the Middle and Late Bronze Age domestic levels

- illuminating the “Philistine” Iron Age I horizon

The current Tel Gezer Excavation project is a long-term project directed by Dr. Steven M. Ortiz of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and Dr. Samuel Wolff of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The excavation is sponsored by the Tandy Institute for Archaeology at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and receives financial support from a consortium of institutions: Ashland Theological Seminary, Clear Creek Bible College, Marian Eakins Archaeological Museum, Lancaster Bible College, Lycoming College, Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, St. Mary’s University College, and New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. The excavations are carried out within the Tel Gezer National Park and benefit from the cooperation of the National Parks Authority. The excavation project also receives support from Kibbutz Gezer and the Karmei Yosef Community Association. The project is affiliated with the American Schools of Oriental Research. The project consists of a field school where an average of sixty to ninety students and staff participate each season. To date, students and staff have come from the United States, Denmark, Canada, Korea, India, Palestinian Territories, and Israel.

The first excavations at Gezer were conducted between 1902 and 1909 by R. A. S. Macalister for the Palestine Exploration Fund. The findings were published in three substantial volumes in 1912. These excavations were the largest yet undertaken by the fund or anyone else in Palestine, not surpassed in size or importance until the Germans worked at Jericho and the Americans at Samaria in 1908. Macalister began at the eastern end of the mound with a series of trenches, each about 10 m wide, running the entire width of the mound. Hedugeach trench down to bedrock(as deep as 13 m in some places). Then, proceeding to the next trench, he dumped the debris into the trench he had just completed. Although his notion of stratification was primitive-- even judged by the standards of the day - he was able to recognize as many as nine strata. In the excavation report he combined his architectural remains into six large plans. Each purports to represent a coherent stratum but is actually a composite of elements several centuries apart. The pottery was grouped according to seven general periods, some covering as many as eight hundred years: Pre-Semitic, First through Fourth Semitic, Hellenistic, and Roman-Byzantine. The remaining material was published by categories rather than by chronological periods - all the burials together, all the domestic architecture, all the cult objects, all the metal and lithic objects - and scarcely a single item can be related to the general strata, let alone to specific buildings.

What was to have been the beginning of a second series of excavations was sponsored at Gezer by the Palestine Exploration Fund in the summer of 1934, under the direction of A. Rowe. He opened an area just west of the acropolis, which both Macalister and he were unable to touch because of the Muslim cemetery and the shrine of a holy man, a weli. However, bedrock was reached in a short time, and the excavations were abandoned. The only significant exposure, apart from an Early Bronze Age cave, was a Middle Bronze Age tower that probably belongs to the inner wall (see below).

In 1964, G. E. Wright initiated a new ten-year project at Gezer, sponsored by the Hebrew Union College Biblical and Archaeological School (later the Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology) in Jerusalem and supported chiefly by grants from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., with some assistance from the Harvard Semitic Museum. The project was directed in 1964-1965 by Wright (thereafter, he was adviser to it), from 1966 through 1971 by W. G. Dever, and from 1972 to 1974 by J.D. Seger. H. D. Lance was associate director, and Glueck was adviser to it from 1964 through 1971. Dever directed the final seasons in 1984 and 1990.

- Map of Major Iron Age

sites of the coastal plain, Shephelah, and hill country of Judah from Ortiz and Wolff (2017)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Major Iron Age sites of the coastal plain, Shephelah, and hill country of Judah.

Ortiz and Wolff (2017) - Location Map from

BibleWalks.com

The cities and roads around Gezer – during the Canaanite and Israelite periods with Gezer marked as a red point

The cities and roads around Gezer – during the Canaanite and Israelite periods with Gezer marked as a red point

(Bible Mapper 3.0)

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Fig. 1 Location Map

from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Location of Gezer and sites mentioned in the text.

Webster et al. (2023)

- Map of Major Iron Age

sites of the coastal plain, Shephelah, and hill country of Judah from Ortiz and Wolff (2017)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Major Iron Age sites of the coastal plain, Shephelah, and hill country of Judah.

Ortiz and Wolff (2017) - Location Map from

BibleWalks.com

The cities and roads around Gezer – during the Canaanite and Israelite periods with Gezer marked as a red point

The cities and roads around Gezer – during the Canaanite and Israelite periods with Gezer marked as a red point

(Bible Mapper 3.0)

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Fig. 1 Location Map

from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Location of Gezer and sites mentioned in the text.

Webster et al. (2023)

- Oblique Aerial View of Tel Gezer

from BibleWalks.com

Aerial View of Tel Gezer

Aerial View of Tel Gezer

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Used with permission from Biblewalks.com - Annotated Aerial View of

Tel Gezer from BibleWalks.com

- Tel Gezer in Google Earth

- Tel Gezer on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 2 Site plan from

Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 2.

Fig 2.

Location of the Tandy excavation relative to previous archaeological fieldwork at Gezer.

Image adapted from [41] (front plan) under a CC BY license, with permission from J. Seger, original copyright 2013.

Webster et al. (2023) - Plan of the mound and

excavation areas from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Gezer: plan of the mound, excavation fields, and principal remains.

Gezer: plan of the mound, excavation fields, and principal remains.

Stern et al (1993 v. 3) - Plate 4 - Plan of Tel Gezer

from Younker (1991)

Plate 4

Plate 4

Plan of Tel Gezer

Younker (1991)

- Fig. 2 Site plan from

Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 2.

Fig 2.

Location of the Tandy excavation relative to previous archaeological fieldwork at Gezer.

Image adapted from [41] (front plan) under a CC BY license, with permission from J. Seger, original copyright 2013.

Webster et al. (2023) - Plan of the mound and

excavation areas from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Gezer: plan of the mound, excavation fields, and principal remains.

Gezer: plan of the mound, excavation fields, and principal remains.

Stern et al (1993 v. 3) - Plate 4 - Plan of Tel Gezer

from Younker (1991)

Plate 4

Plate 4

Plan of Tel Gezer

Younker (1991)

- Plate 19 - Hand drawn plan

of Outer and Inner Walls in Field XI (North Wall) from Younker (1991)

Plate 19

Plate 19

Detail of Field XI (after Macalister). Note approximate locations of Squares 21 and 22.

Younker (1991) - Plate III.1 - Plan of Inner and

Outer Walls in Field XI from Dever (1992)

Plate III.1

Plate III.1

E/23. Field XI, Areas 20-22

Dever (1992)

- Plate 19 - Hand drawn plan

of Outer and Inner Walls in Field XI (North Wall) from Younker (1991)

Plate 19

Plate 19

Detail of Field XI (after Macalister). Note approximate locations of Squares 21 and 22.

Younker (1991) - Plate III.1 - Plan of Inner and

Outer Walls in Field XI from Dever (1992)

Plate III.1

Plate III.1

E/23. Field XI, Areas 20-22

Dever (1992)

- Fig. 3 Photo/Plan of fields

III and VII (South Gate) from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 3

Fig 3

Aerial view of the Tandy excavations, with a wide exposure of iron age strata on the central-southern edge of the Gezer mound between fields VII and III of Hebrew Union College.

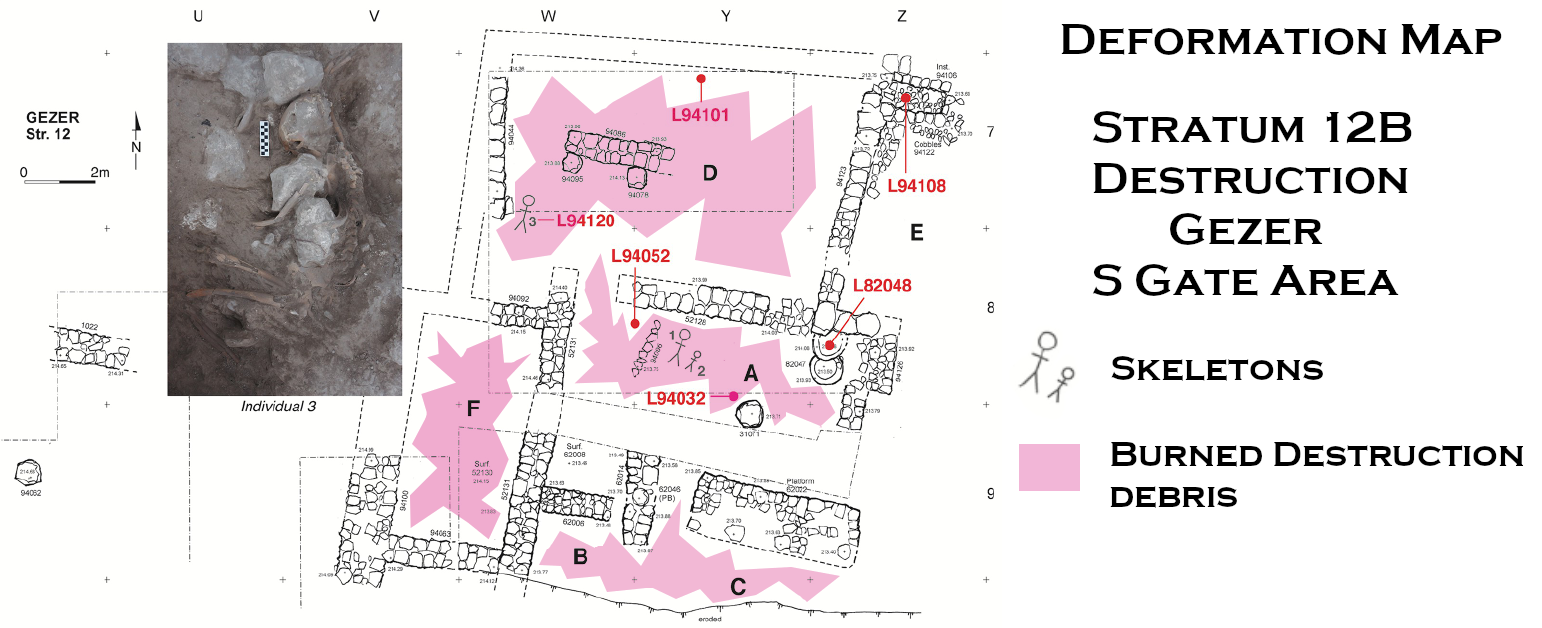

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Plan of Stratum 12B

elite residence in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 4

Fig 4

Plan of Tandy excavation stratum 12B elite residence with radiocarbon dated contexts marked. The insert shows Individual #3.

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 6 Plan of Strata 10A & 9

in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 6

Fig 6

Plan of Tandy excavation strata 10A and 9 with radiocarbon dated contexts marked.

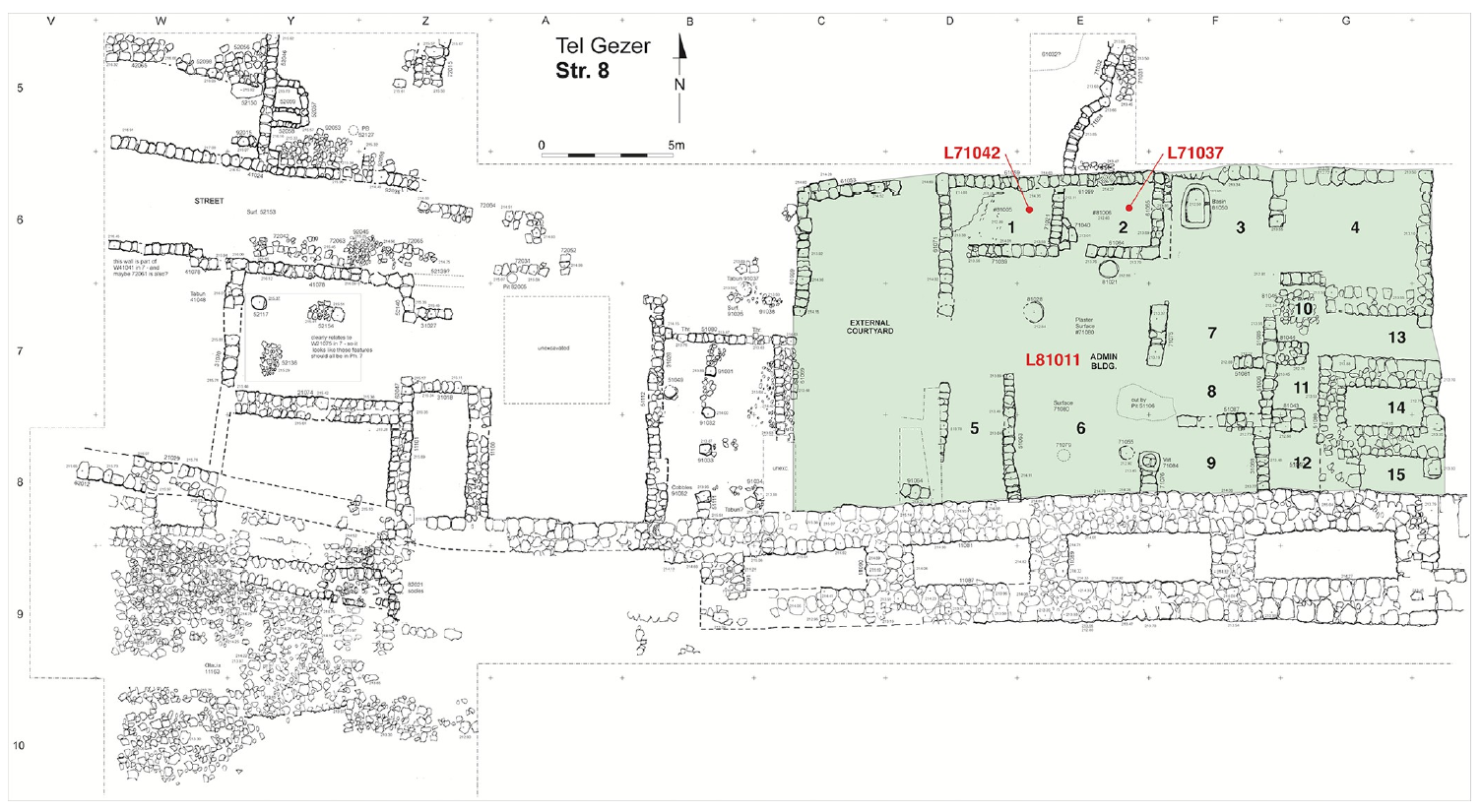

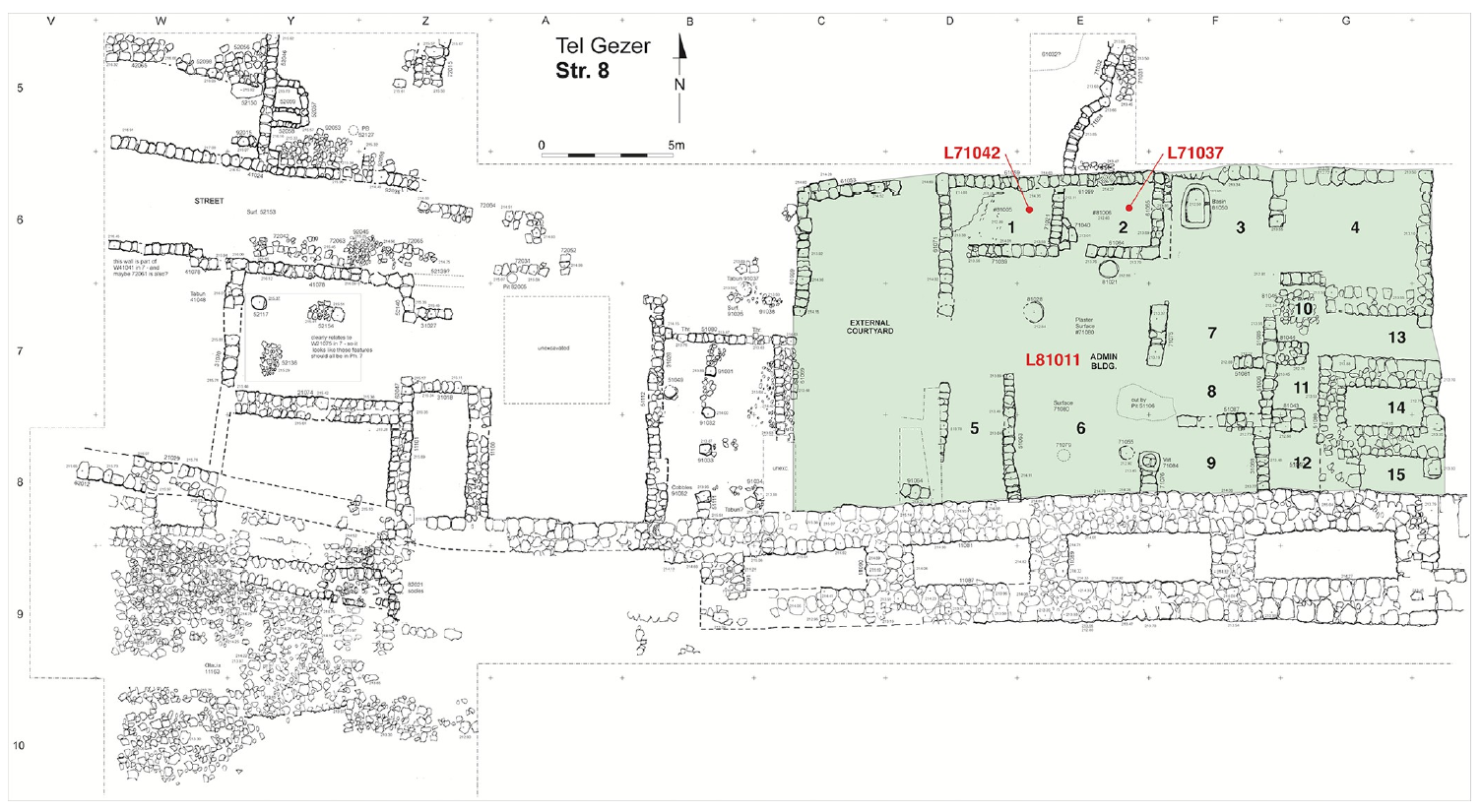

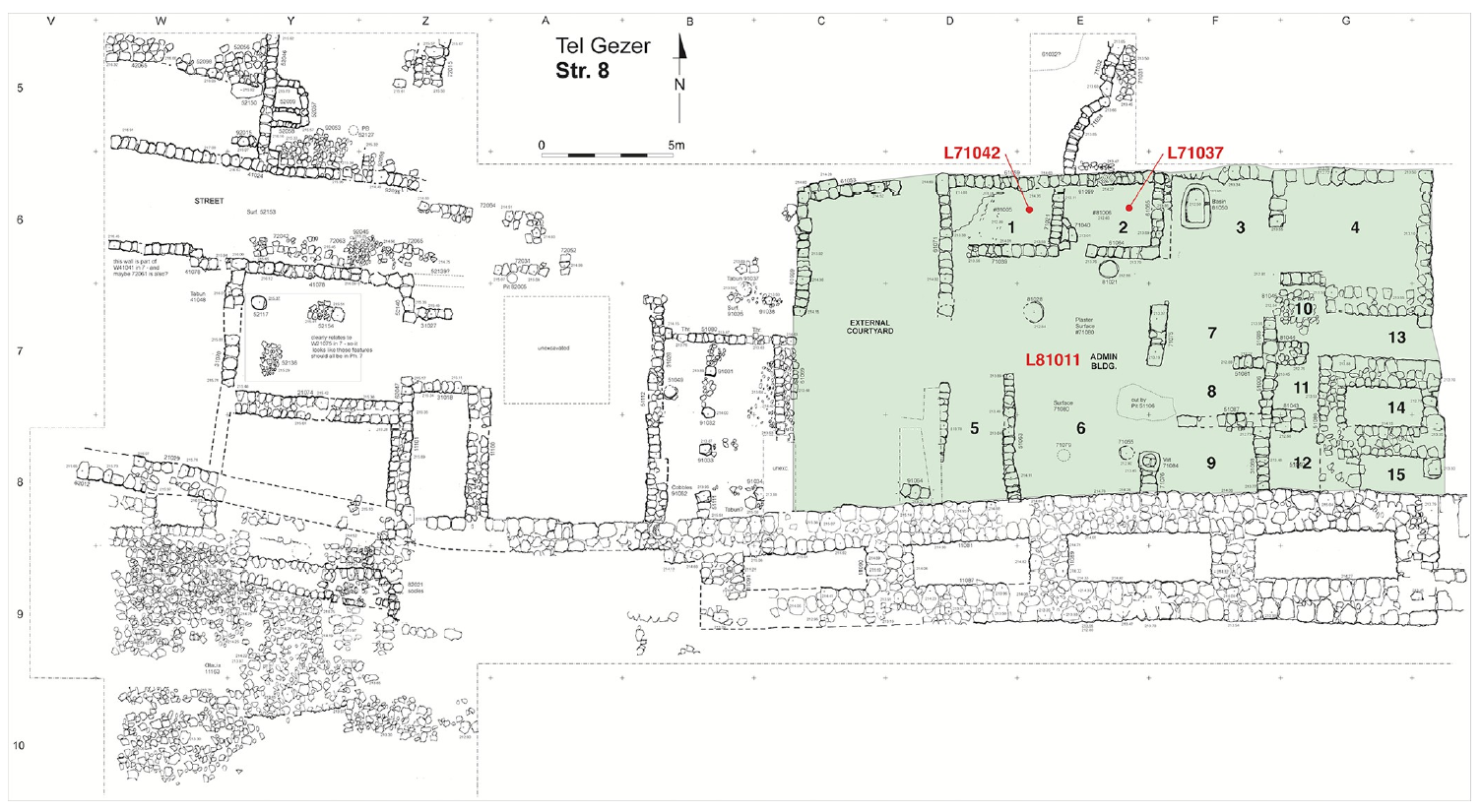

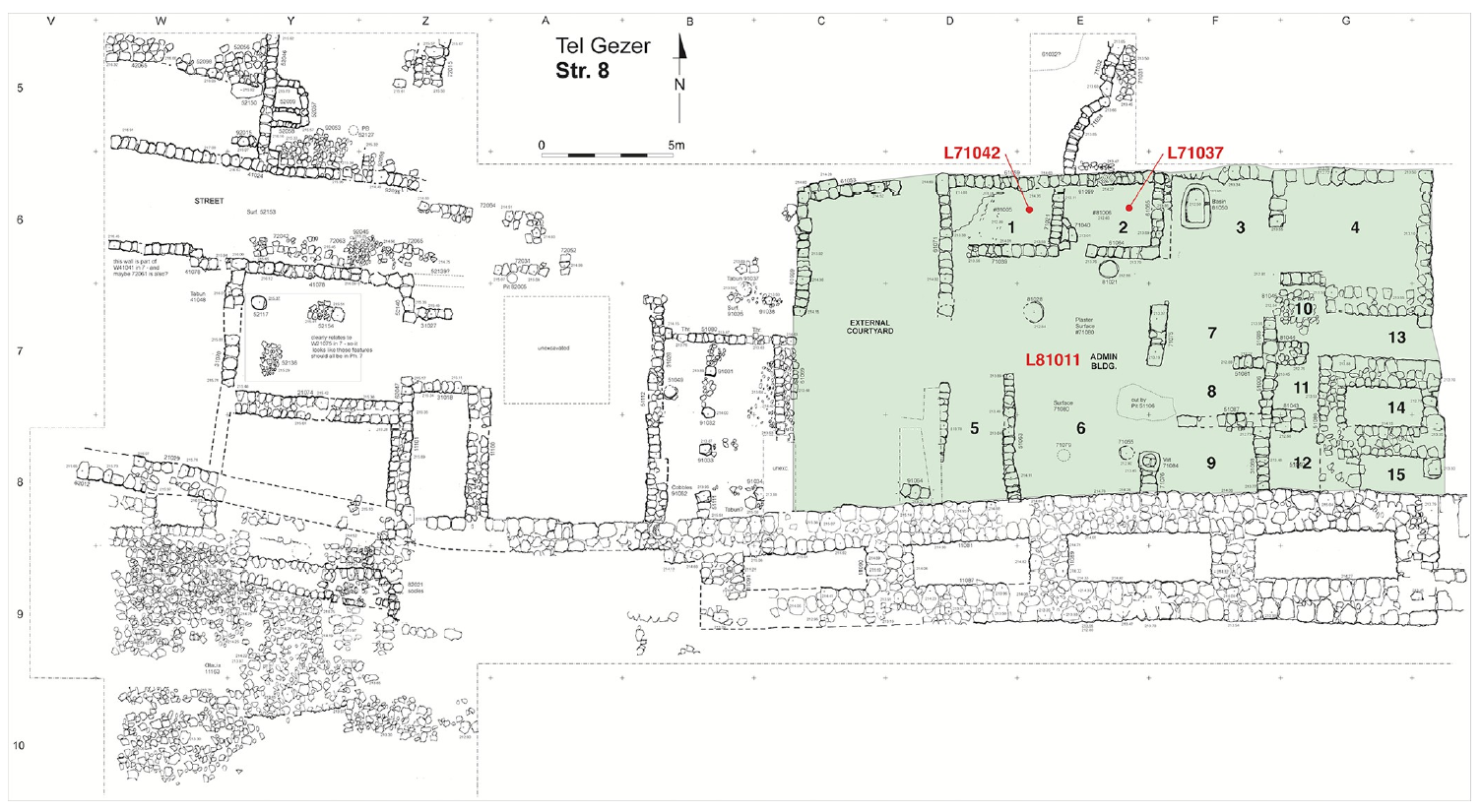

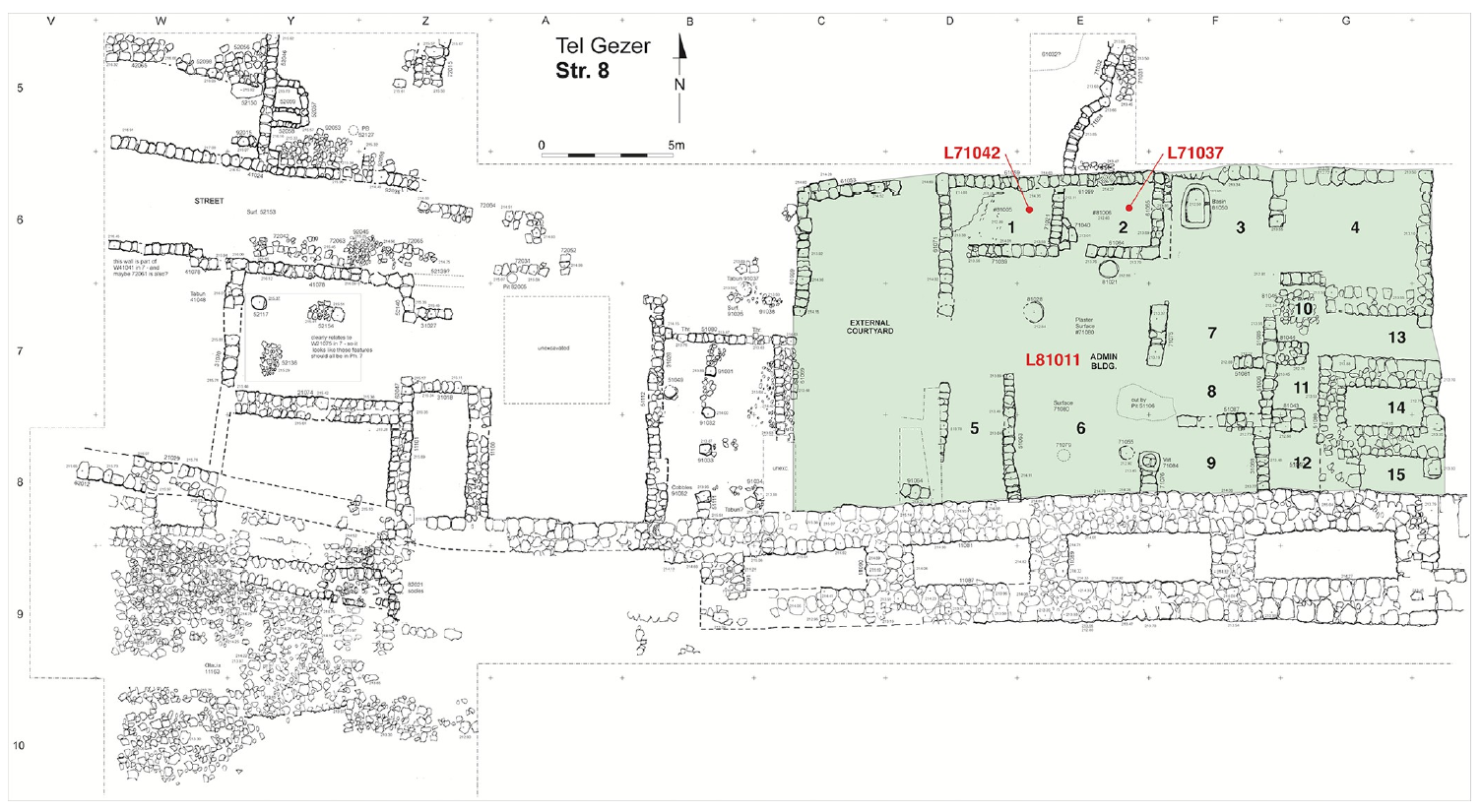

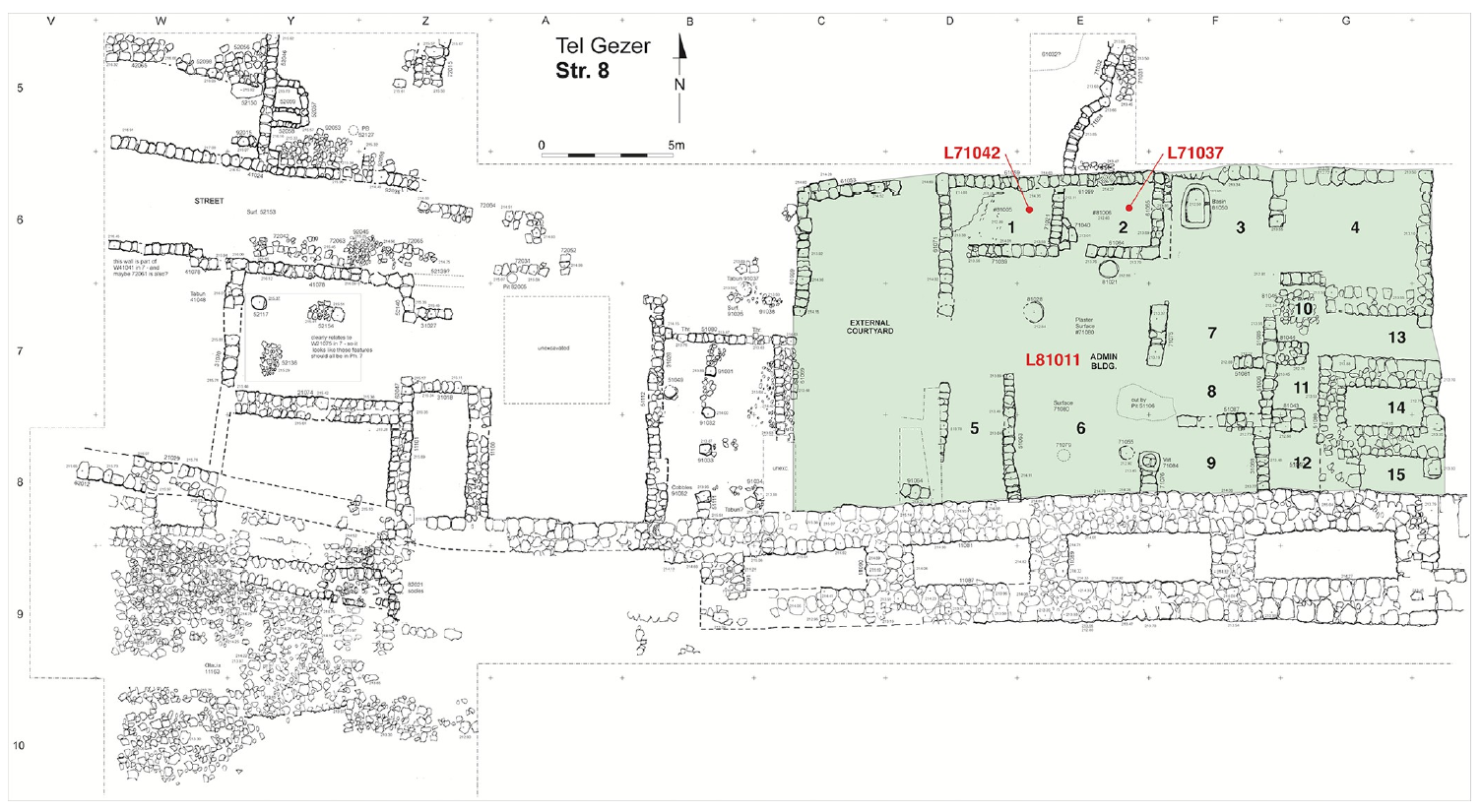

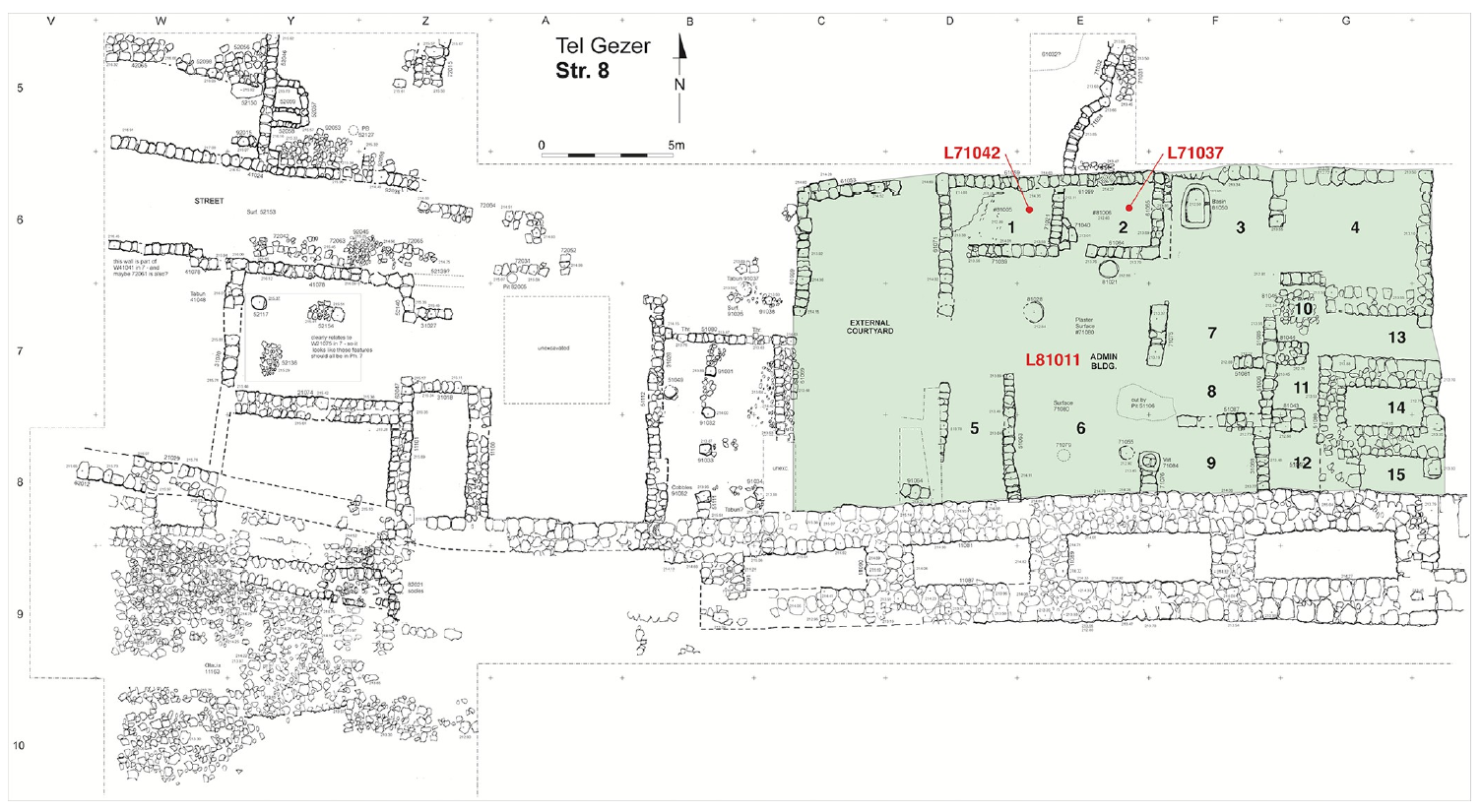

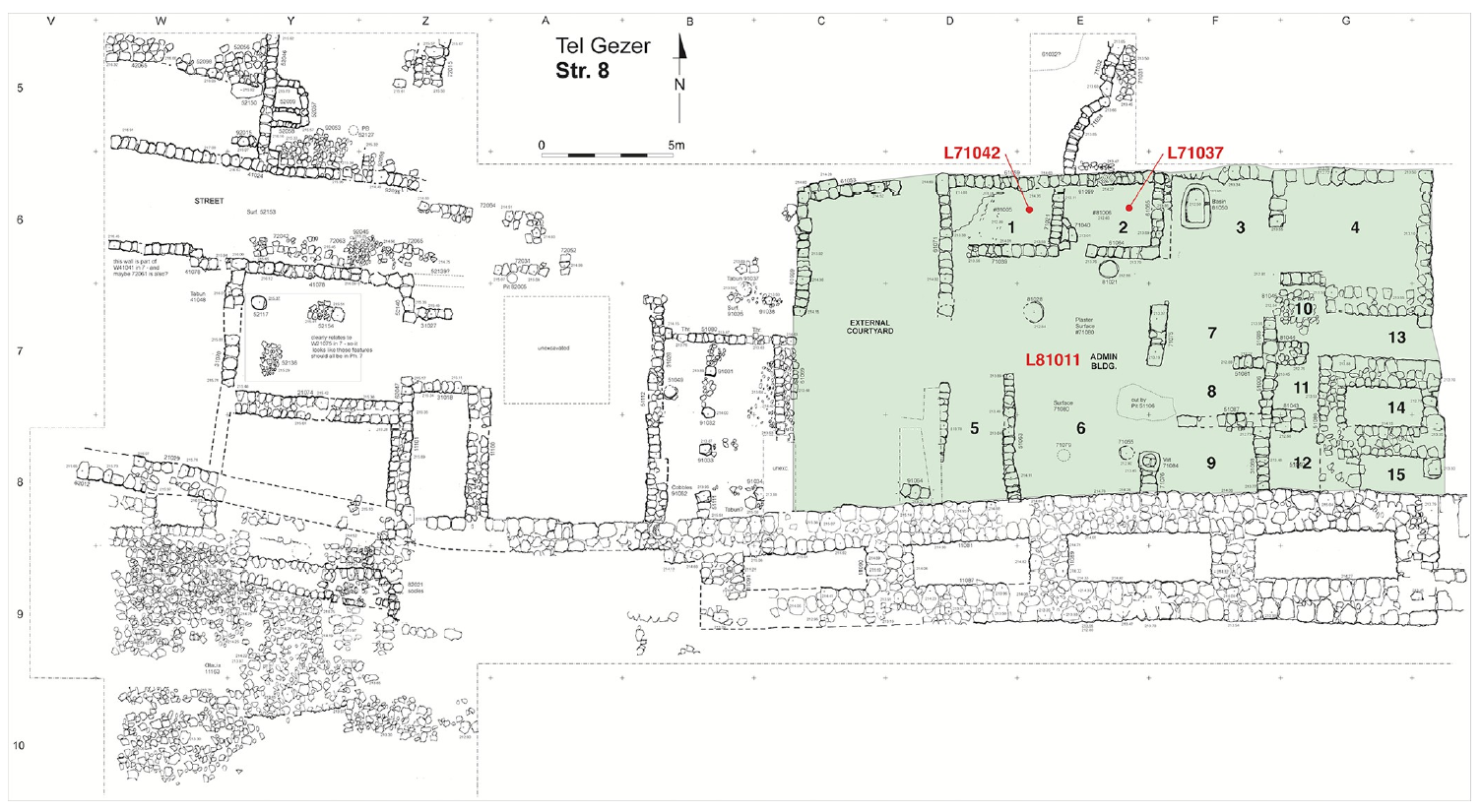

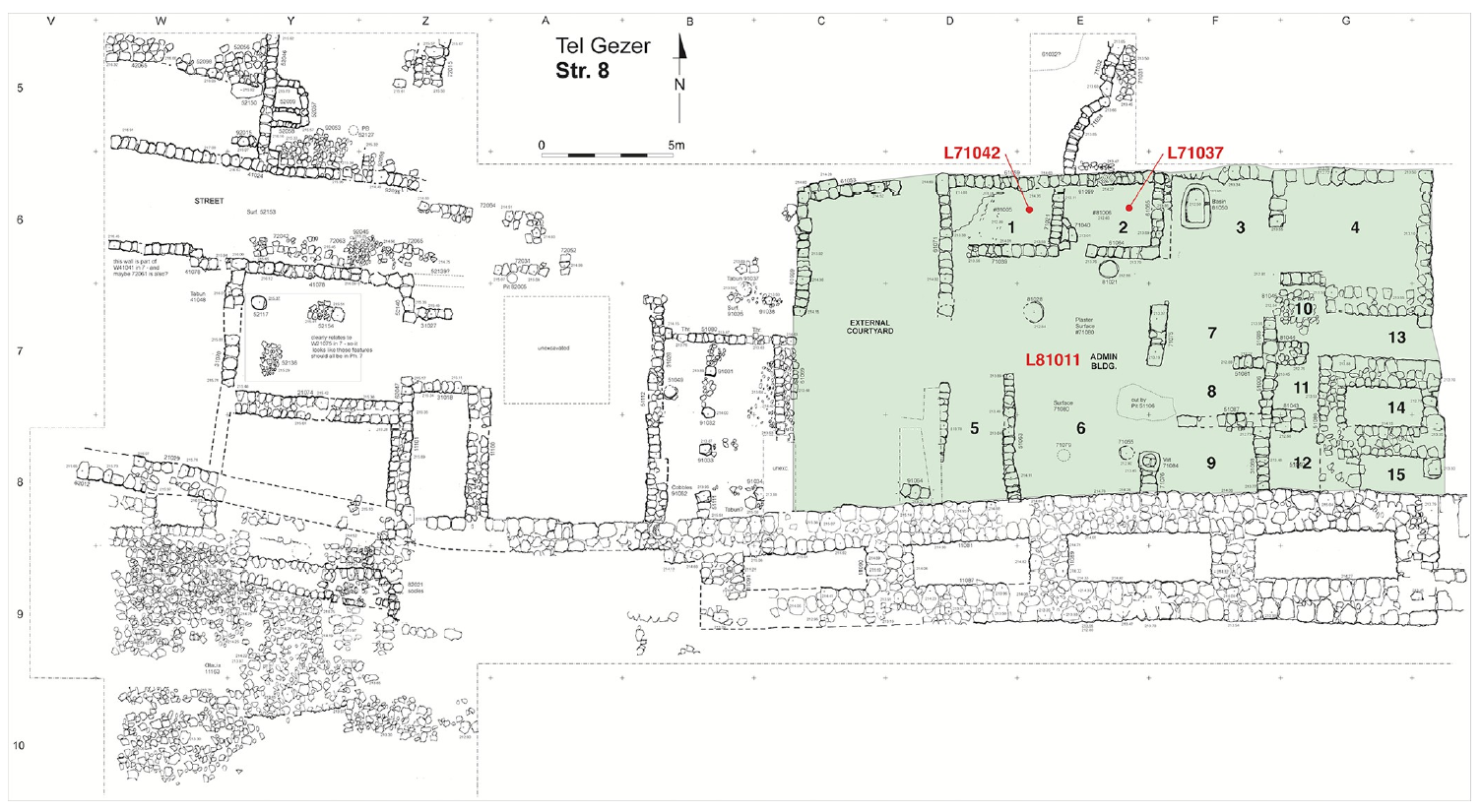

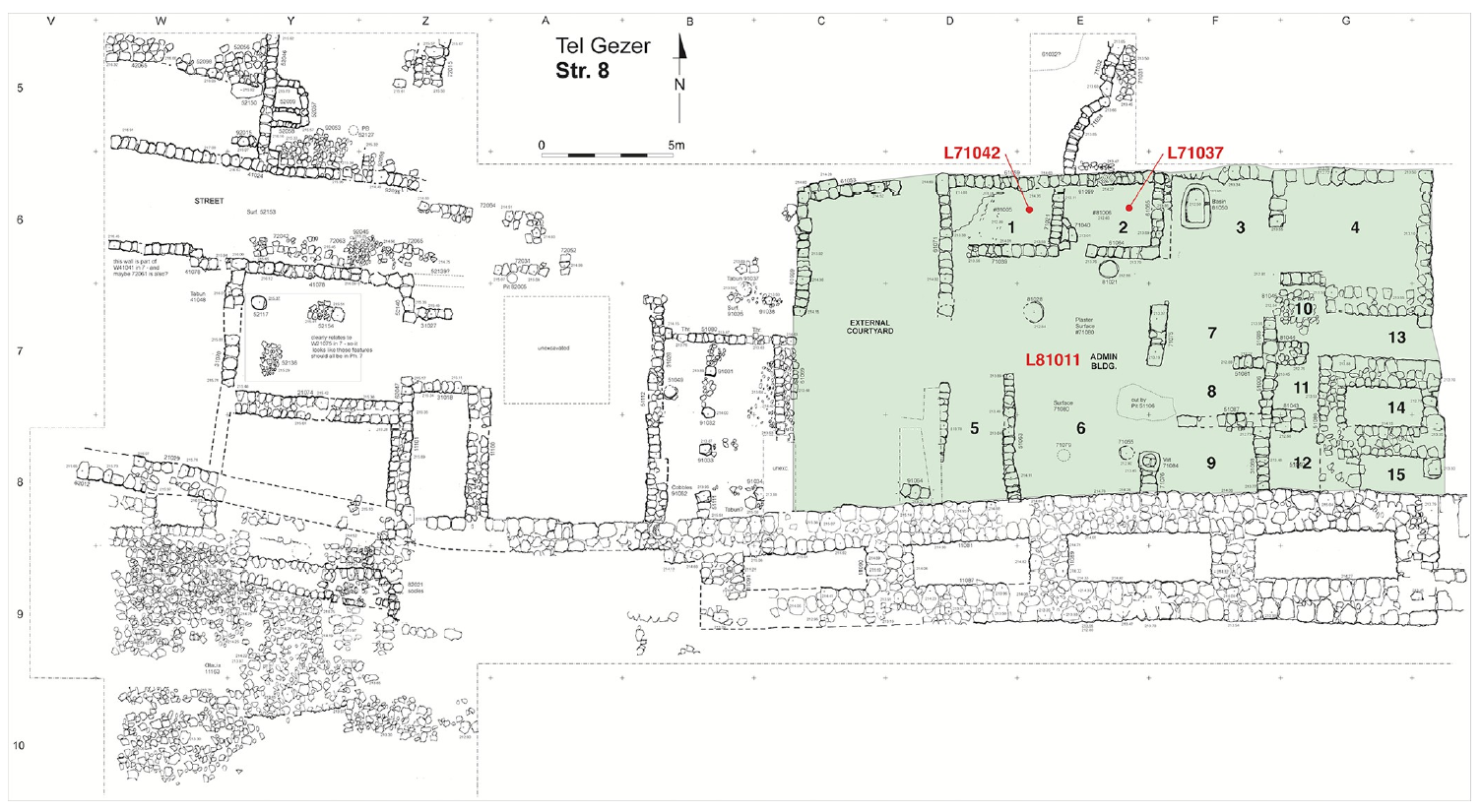

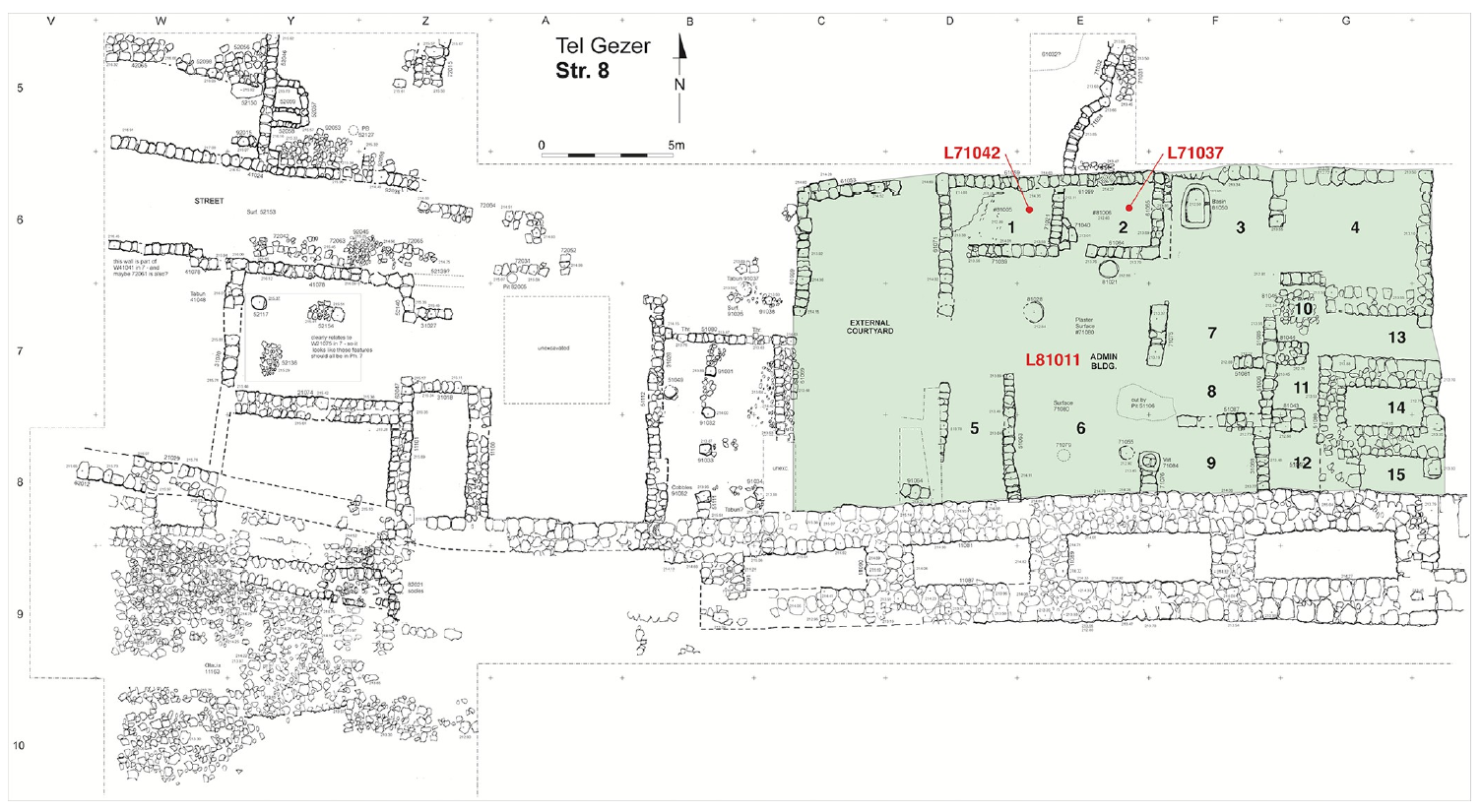

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 7 Plan of Stratum 8

in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 7

Fig 7

Plan of Tandy excavation stratum 8 with radiocarbon dated contexts in the courtyard-type administrative building marked.

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 8 Plan of Stratum 7

in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 8

Fig 8

Plan of Tandy excavation stratum 7 domestic units with radiocarbon dated contexts marked.

Webster et al. (2023)

- Fig. 3 Photo/Plan of fields

III and VII (South Gate) from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 3

Fig 3

Aerial view of the Tandy excavations, with a wide exposure of iron age strata on the central-southern edge of the Gezer mound between fields VII and III of Hebrew Union College.

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Plan of Stratum 12B

elite residence in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 4

Fig 4

Plan of Tandy excavation stratum 12B elite residence with radiocarbon dated contexts marked. The insert shows Individual #3.

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 6 Plan of Strata 10A & 9

in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 6

Fig 6

Plan of Tandy excavation strata 10A and 9 with radiocarbon dated contexts marked.

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 7 Plan of Stratum 8

in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 7

Fig 7

Plan of Tandy excavation stratum 8 with radiocarbon dated contexts in the courtyard-type administrative building marked.

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 8 Plan of Stratum 7

in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 8

Fig 8

Plan of Tandy excavation stratum 7 domestic units with radiocarbon dated contexts marked.

Webster et al. (2023)

- Plate VIII - Map of

the surroundings of Gezer from Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate VI

Plate VI

Plan of Hellenistic Period [JW: Dever (1992) says this is Iron Age]

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plan of the excavations

from Macalister (1912 v. 3)

Key Plan of the Excavations showing their relation to the area of the city

Key Plan of the Excavations showing their relation to the area of the city

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate II - Plan of

1st Semitic Period from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate III

Plate III

Plan of 1st Semitic Period

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate III - Plan of

2nd Semitic Period from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate III

Plate III

Plan of 2nd Semitic Period

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate IV - Plan of

3rd Semitic Period from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate IV

Plate IV

Plan of 3rd Semitic Period

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate V - Plan of

4th Semitic Period from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate V

Plate V

Plan of 4th Semitic Period

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate VI - Plan of

Hellenistic Period [JW: Dever (1992) says this is Iron Age] from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate VI

Plate VI

Plan of Hellenistic Period [JW: Dever (1992) says this is Iron Age]

Macalister (1912 v. 3)

- Plate VIII - Map of

the surroundings of Gezer from Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate VI

Plate VI

Plan of Hellenistic Period [JW: Dever (1992) says this is Iron Age]

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plan of the excavations

from Macalister (1912 v. 3)

Key Plan of the Excavations showing their relation to the area of the city

Key Plan of the Excavations showing their relation to the area of the city

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate II - Plan of

1st Semitic Period from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate III

Plate III

Plan of 1st Semitic Period

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate III - Plan of

2nd Semitic Period from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate III

Plate III

Plan of 2nd Semitic Period

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate IV - Plan of

3rd Semitic Period from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate IV

Plate IV

Plan of 3rd Semitic Period

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate V - Plan of

4th Semitic Period from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate V

Plate V

Plan of 4th Semitic Period

Macalister (1912 v. 3) - Plate VI - Plan of

Hellenistic Period [JW: Dever (1992) says this is Iron Age] from and according to Macalister (1912 v. 3) (follow link to bigger image)

Plate VI

Plate VI

Plan of Hellenistic Period [JW: Dever (1992) says this is Iron Age]

Macalister (1912 v. 3)

- Artist's Rendition of Gezer

during the Iron Age from BibleWalks.com

Artist's Rendition of Gezer during the Iron Age. View from the South.

Artist's Rendition of Gezer during the Iron Age. View from the South.

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com

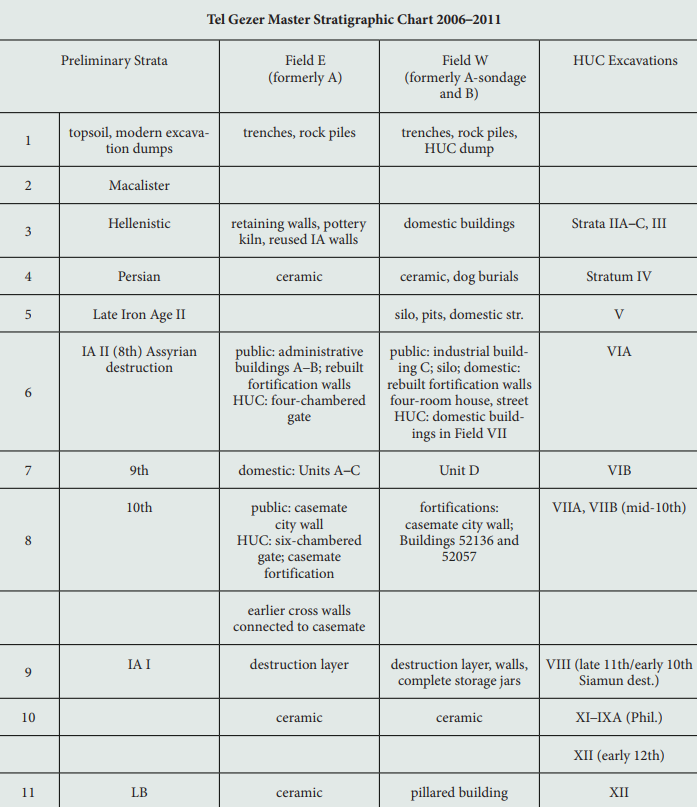

Table 1

Table 1Stratigraphy of the Gezer Tandy excavation, with reference to HUC (Hebrew Union College) stratigraphy.

Webster et al. (2023)

- from Webster et al. (2023:8-13)

- Number in brackets refer to references in Webster et al. (2023)'s paper

| South Gate Stratum (Tandy excavation) |

Site-wide stratum (HUC excavation) |

Period | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12B | XV | LB IIB |

Discussion

Stratum 12B (XV; LB IIB) is the earliest horizon for which a wide exposure has been

achieved and features a large building (ca. 15 m x 20 m) (Fig 4). The building extends all the

way to the slope edge and has partially eroded away, such that the southern closing wall can

only tentatively be reconstructed. There are two major room units (A–C and D) and a courtyard (E); Room F forms an auxiliary western room or part of an adjacent building. Working

Room A includes a stone vat and a well-worn disc-shaped working surface that was initially

interpreted as a pillar base; small finds here included a scarab of Amenhotep III, a cylinder seal

and several gold foil pieces. Several key finds were also retrieved from Room D, particularly a

bifacial plaque with the cartouche of Thutmose III – a typical 19th Dynasty product commemorating the 18th Dynasty ruler. The overall nature and function of the Phase 12B building is

uncertain, but the excavators suggest it served as an elite residency [58]. |

| 12A | XIV | Iron IA |

Discussion

Stratum 12A (XIV; Iron IA). The inhabitants of Gezer evidently quickly re-established themselves following the destruction, as is indicated by a minor rebuild of the elite residency, and by similar re-use of architecture in Field II (local Str. 12) [47]. This phase is dated to Iron IA. |

| 11 | XIII–XII | Iron IA/B |

Discussion

In Stratum 11 (XIII–XII; Iron IA/B) the layout changed completely (Fig 5 left). Gezer was apparently fortified during Iron I: a portion of the city wall was revealed along the edge of the slope, directly over the remains of Stratum 12. Little is known regarding the city gate or other elements of this fortification system. Against the northern face of the city wall, a row of irregularly sized units (1–5) was built, interpreted as storage rooms and perhaps forming a precursor to the Iron II casemate system. Further inside the city some 150 m2 of a building complex was exposed; this includes a large pillared room (D) and other partially-defined spaces to the north (A) and east (B, C, E, F). Stratum 11 has been dated to Iron IA/B. Notably, Philistine pottery (‘Philistine 2’ ware) appears for the first time in this horizon. |

| 10 | XI–IX | Iron IB |

Discussion

Stratum 10 (XI–IX; Iron IB) with its two sub-phases reflects modifications to the plan of

the Stratum 11 complex (Fig 5 right). Surfaces were replaced and dividing walls added or

removed until an arrangement of four spaces (A–D) was reached in Stratum 10A (Fig 6 left).

In this last sub-phase an east-west street is evident, running along the northern wall of the

complex. The fortification wall and row of units adjoining the complex to the south were used

in Stratum 10 without modification. |

| 9 | Iron I/IIA |

Discussion

Stratum 9 (Iron I/IIA) is an ephemeral phase that comprises the rebuild of a domestic structure (Fig 6 right). The builders were well aware of the destroyed Stratum 10 horizon and built directly on its architecture, integrating or reusing some architectural elements (e.g. Room 4 walls of Stratum 10). Stratum 9 seems to be associated with a new city wall that was subsequently further transformed in Stratum 8. The stratum may belong to late Iron I or early Iron IIA. |

|

| 8 | VIII | Iron IIA |

Discussion

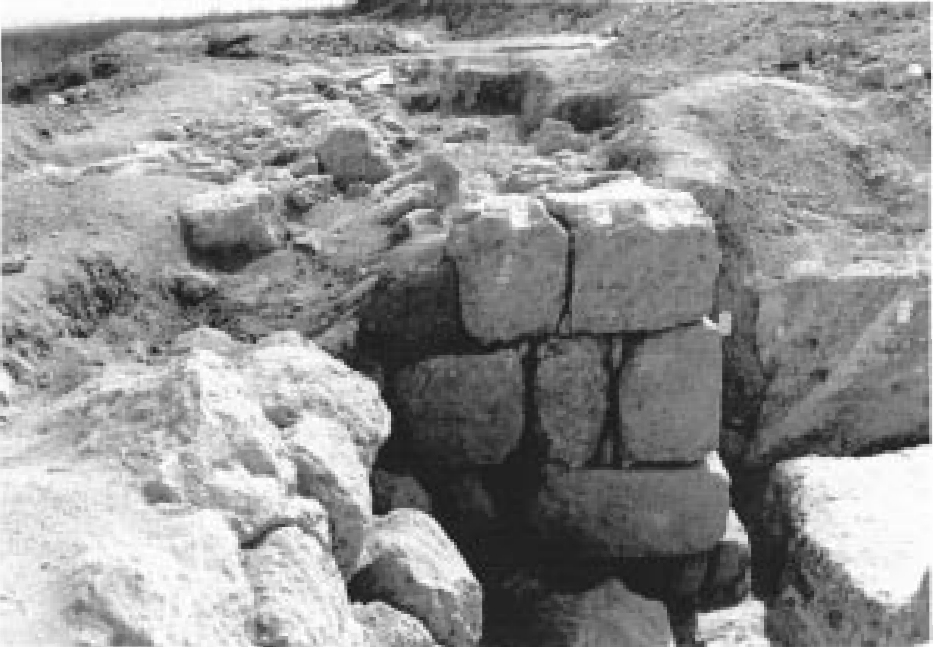

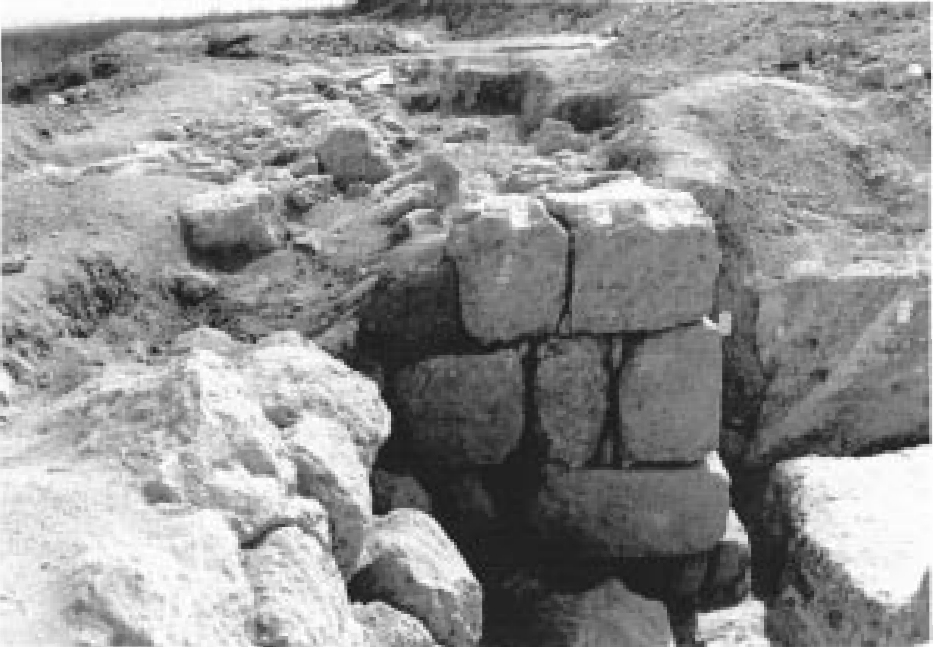

Stratum 8 (VIII; Iron IIA) signals a major transformation at Gezer, with the appearance of

monumental architecture (Fig 7). A new fortification system featuring a massive six-chambered gate, casemate wall and new stone-covered glacis was built in this part of the site, and a

large administrative building laid out close by. Macalister encountered the gate and casemate

but misdated them to the Hellenistic period [37]. Both were investigated stratigraphically by

HUC after Yadin identified the gate’s partial plan in Macalister’s drawings–similar to gates at

Hazor (X) and Megiddo (Str. VA–IVB) [39, 48, 49]. The Tandy expedition re-exposed ca. 27

m of the casemate wall west of the gate (after which it gives way to a single wall line) and identified an accompanying stone-covered glacis. To the fortification system of Stratum 8, HUC

would add the Outer Wall and lower gateway [55], but the stratigraphic associations of these

elements is debated. Finkelstein [75] has associated the construction of both with Stratum VII

(= Tandy Stratum 7). |

| 7 | VII | Iron IIA |

Discussion

In Stratum 7 (VII; Iron IIA) the character of the gate area changed from administrative to

domestic, and adjoining units were built along the north face of the city wall (Fig 8). One fully

excavated building unit (D) includes a main pillared room and an interconnected group of

storage and work rooms. The casemate wall was re-used but the gate was rebuilt with a fourchambered plan [48, 49]. |

| 6 | VI | Iron IIB |

Discussion

In Stratum 6 (VI; Iron IIB) the character of the architecture changed again, and three major public buildings were erected west of the city gate. In the northwestern part of its excavation, the Tandy expedition exposed a Four Room House [123], similar to but significantly larger than others found in adjacent Field VII [51]. The domestic buildings show clear evidence of destruction by fire, and the end of the stratum has been associated with the historically well-known campaign of the Assyrian monarch Tiglath Pileser III [35, 60]. |

Figure 10A

Figure 10ABayesian 14C model A for the Tandy excavation

The models use OxCal’s outlier analysis. Model A includes all data.

- Individual probability distributions before and after modelling are shown in light and dark grey respectively.

- Calculated transition boundaries are colored green, while date estimates for strata are red.

- Highest posterior density (hpd) ranges after modelling (68.3% and 95.4%) are marked with bars below each result.

- Prior and posterior outlier probabilities are indicated in square brackets after the laboratory number and locus.

- The OxCal code is provided in S1 Appendix.

Webster et al. (2023)

Figure 10B

Figure 10BBayesian 14C model B for the Tandy excavation

The models use OxCal’s outlier analysis. Model B excludes two outliers in Tandy Stratum 8 (Beta-436538 and Beta-436540).

- Individual probability distributions before and after modelling are shown in light and dark grey respectively.

- Calculated transition boundaries are colored green, while date estimates for strata are red.

- Highest posterior density (hpd) ranges after modelling (68.3% and 95.4%) are marked with bars below each result.

- Prior and posterior outlier probabilities are indicated in square brackets after the laboratory number and locus.

- The OxCal code is provided in S1 Appendix.

Webster et al. (2023)

Figure 10

Figure 10Bayesian 14C models (A and B) for the Tandy excavation

The models use OxCal’s outlier analysis. Model A includes all data. Model B excludes two outliers in Tandy Stratum 8 (Beta-436538 and Beta-436540).

- Individual probability distributions before and after modelling are shown in light and dark grey respectively.

- Calculated transition boundaries are colored green, while date estimates for strata are red.

- Highest posterior density (hpd) ranges after modelling (68.3% and 95.4%) are marked with bars below each result.

- Prior and posterior outlier probabilities are indicated in square brackets after the laboratory number and locus.

- The OxCal code is provided in S1 Appendix.

Webster et al. (2023)

Figure 11

Figure 11Comparison of 14C dated transitions at Gezer with key data from nearby sites and the Egyptian chronology.

The 14C - based Egyptian chronology follows Dee [3] and Manning [4] and is updated with IntCal20 [137]. It assumes the ultra-high reign lengths of Aston [144] for Thutmoses III through Ramesses II and reign lengths from Schneider [145] for all others. Absolute date estimates based on traditional methods are shown for Schneider (same line as the 14C - based estimates) and Kitchen [146] (separate line below). Key results from sites neighboring Gezer are colored brown. Source models and data references for these sites are provided in S1 Appendix.

Webster et al. (2023)

- from Webster et al. (2023:13-14)

- links take you to online version of this paper

Short-lived organic materials (primarily charred seeds) suitable for radiocarbon dating were collected throughout the ten Tandy excavation seasons, found in association with floors, installations, phytolith layers, burials and destruction layers. During the 2017 field season, the lead author worked with the team to improve the retrieval rate of smaller seeds/fragments from the most secure contexts (i.e. low likelihood of residual or intrusive material) by using targeted fine dry sieving. Samples for dating were selected to represent the series of overlying occupation horizons, where possible using multiple contexts and at least three measurements per stratum. Priority was given to contexts with evidence of in situ burning or larger concentrations of organic material (seed clusters, phytolith layers). Almost the whole late LBA through Iron IIA stratigraphy, from Stratum 12B through 7 was addressed (Table 3), with data lacking only for Stratum 12A. We initially chose not to radiocarbon date Stratum 6 because its expected chronological position (destroyed in 734 BC) would place it on the Hallstatt Plateau [124].

Samples for Stratum 12B derive from a wide variety of contexts across the elite residency (Fig 4). Charred seeds were obtained from the burnt contents of a tabun (L94101; Room D), from ash-filled contents (L94108) of a bin (L94106; Room E) and burnt destruction debris on the floor of Room A (L94032, L94052). L94052 is a concentration of charred seeds found together with restorable pottery. Also associated with Stratum 12B are seeds obtained from Vat L82047 (contents L82048); destruction debris within the vat was generally unburnt, making the charred seeds from this context somewhat less secure. The unburnt fully articulated skeleton of Individual #3 (L94120) provided bone collagen for dating. Overall, the samples may be expected to represent the use of the building, predominantly its last years. No dateable material was obtained for the subsequent rebuild of the elite residency (Str. 12A).

Samples from Stratum 11 derive from organic-rich deposits spread across a plaster floor (L92030 and L92040; Room D), and from a foundation deposit (L92008; Room B) (Fig 5 left). Stratum 10B is represented by a concentration of charred olive pits (L92010) on cobbled surface L82064, immediately adjacent to bin L92020 in Room A; three measurements were made from L92010 (Fig 5 right). Stratum 10A samples come from seeds on the plaster floor (L82040) of Room B, and a seed concentration associated with storage jars in Room A (L82026; Fig 6 left). Just one sample was identified that can reliably date Stratum 9: seeds on cobbled surface L82023 (Fig 6 right).

From the Stratum 8 Courtyard-type Administrative Building, several charred seeds were found on the plastered floors of Rooms 1 and 2 (L71042 and L71037), and others above the courtyard surface of Room 6 (L81011) (Fig 7). Plentiful charred seeds for dating Stratum 7 were obtained from rooms in Unit D, most notably destruction debris (L81002) in Room 5 and the burnt contents of a tabun (L81034) in Room 6 (Fig 8). Additional seeds were found while dismantling the plaster surface of Room 5 (L81025) and within a dog burial north of Unit C (L91050).

Table 3

Table 3Radiocarbon dates from the Tandy excavation at Tel Gezer.

All measurements were made on charred seeds, with the exception of SANU-60015 (bone collagen). Adjacent pairs of results marked with an asterisk (*) were measured on the same seed. hpd = highest probability density.

Webster et al. (2023)

- from Webster et al. (2023:14, 17)

- links take you to online version of this paper

A total of 35 radiocarbon dates were run from seven strata / sub-strata, most represented by at least four measurements (Table 3). Multiple measurements were made for several contexts with large seed concentrations (e.g. Str. 12 17/94052, Str. 10B 16/92010, Str. 10A 15/82040 and Str. 7 15/81034). 14C measurement by Accelerator Mass Spectrometer (AMS) was carried out at five laboratories, primarily the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) (15 dates), the University of Groningen (9 dates) and BETA Analytic (9 dates). All measurements were made on single entity charred seeds, except for one measurement on bone collagen (SANU-60015, Australian National University facility). Samples were pretreated using an Acid-Base-Acid (ABA) protocol to remove carbon-bearing contaminants [126, 127]; in one case the measurement was made on the humic acid component (GrM-13317). Following ABA, the bone collagen was extracted using a gelatinization and ultrafiltration protocol [128]. Pretreated samples were combusted and the resultant CO2 converted to graphite, a portion of which was used to determine δ13C by Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) for isotopic fractionation correction. AMS 14C measurement, along with standards and blanks, was made using a MICADAS (IonPlus®) accelerator at Groningen and ETH Zürich [129, 130], the ANTARES 10MV, STAR 2MV HVEE or VEGA 1MV NEC accelerators at ANSTO [131–133] and the Single Stage AMS at ANU [134].

Radiocarbon ages are reported in 14C years before present (BP) following international convention [135, 136]. Calibrated ages in calendar years were obtained using OxCal v 4.4 [118] and IntCal20 [137] interpolated to yearly intervals (Resolution = 1). Age ranges are given at 68.3% and 95.4% highest probability density (hpd; or ‘highest posterior density’ for modelled ranges).

Five ANSTO dates (prefix ‘OZX’) were revised by the laboratory after unstable current was noted in the AMS run, the correction giving younger ages by approximately 50 14C years BP. This was validated by additional measurements (prefix ‘OZZ’) on the same seed or context.

- from Webster et al. (2023:17-18)

- links take you to online version of this paper

To obtain more precise chronological information, radiocarbon data was combined with a priori knowledge of relative stratigraphic order using a Bayesian approach [116–118]. Using OxCal v 4.4, dates were arranged in a sequence of ‘phases’ according to the archaeological strata. No internal order was assumed between dates inside the same phase. Single boundaries indicate phases that are contiguous (i.e. strata thought to follow one another without a gap), while an extra boundary and empty phase were introduced where radiocarbon data is lacking (e.g. Stratum 12A). Between Phases 9 and 8 an extra boundary was used due to the especially marked change in architecture and possible gap, and the low data quantity (single date) representing Phase 9. Weighted averages were applied only for measurements from the same seed and only when these pass the χ2 test. Note that the Bayesian models use only radiocarbon data and stratigraphic order within the Tandy excavation field; no constraints from historical information were applied.

There are two approaches to addressing outliers in OxCal [138]. A common strategy has been to iteratively remove dates with the lowest agreement index from the model until the overall model agreement index exceeds 60%. This can sometimes result in the complete exclusion of a substantial portion of data. A second approach utilises OxCal’s outlier functionality to automatically identify and downweigh poorly fitting data. The probability of a date being an outlier is assumed to follow a Student’s t distribution (the so-called ‘General’ model) and an initial 5% prior probability is assumed. The model subsequently calculates posterior outlier probabilities for all dates based on the model fit. These assumptions are appropriate for short-lived materials, which comprise all the Tandy excavation radiocarbon samples. The second approach to outliers–which is the one primarily employed here–is preferable because it generally reduces the need to manually eliminate dates from models. It is, however, sometimes still prudent to test the effect of fully excluding those dates identified as probable outliers, to ensure they are not unduly influencing the model. For robust modelling, both approaches to outliers should yield very similar results. For the purpose of comparison we provide a model using agreement indices in the supplementary data.

- from Webster et al. (2023:18)

- links take you to online version of this paper

The set of independently calibrated radiocarbon dates from Tandy Strata 12B–7 generally reflect the stratigraphic order well (Table 3, Fig 9). The great majority of results are consistent within each stratum/sub-stratum, bearing in mind effects due to the shape of the calibration curve. Dates from multiple laboratories and AMS runs show good agreement, including five pairs of measurements on fragments of the same olive pit (marked blue in Fig 9 and by an asterisk in Table 3).

Two dates in Stratum 8 (Beta-436538 and Beta-436540) seem to be outliers; these seeds were found close to surfaces but not in large clusters and hence the risk of residual material is higher. Two Stratum 12B dates (GrM-13317 and GrM-13321) also appear somewhat early (though with better overlap), but these samples are from large seed concentrations that were certainly burnt in situ and should be reliable; we suspect this may be simply a matter of measurement statistics, or the seeds include material from slightly earlier in the life of Stratum 12B.

- from Webster et al. (2023:18-21)

- links take you to online version of this paper

Constraining the radiocarbon data with stratigraphic order using a Bayesian approach, Fig 10 Model A utilises all dates and applies OxCal’s ‘General’ outlier model with 5% prior outlier probabilities. The prior and posterior outliers are displayed for each date, after the laboratory code and locus. Only Beta-436538 and Beta-436540 of Stratum 8 show distinctly elevated posterior probabilities of being outliers (44% and 66% respectively). Since these two samples fit poorly with the surrounding data and their contexts are less secure (not seed clusters or burnt in situ, though found on floors), we opted to run a second version of the Bayesian model in which they are fully excluded (Fig 10 Model B). This does not have a major impact on model outcomes but does provide narrower and arguably more realistic estimates for Stratum 8 and its boundaries; hence we prefer this model.

For the purpose of comparison, a model that uses the alternate approach to outliers (i.e. agreement indices and manual, iterative removal of dates) is provided (Model C, S1 Fig). The results are very similar to Models A and B. To reach an overall model agreement index >60%, three dates were iteratively removed, including the same two Stratum 8 dates, and OZ-V267 of Stratum 7.

The output from all models is provided in S1 and S2 Tables, and the OxCal code in S1 Appendix. All elements of the models converged at ≥95%. In the following discussion, results are cited from our preferred model (B) unless specified otherwise. Table 4 summarises key results from Model B: phase transitions and use-length estimates, the latter obtained using OxCal’s ‘Date’ function.

The Bayesian models place Stratum 12 in the 13th century BC, although we cannot yet reliably ascertain when this occupation horizon began. This must await further excavation, particularly of underlying Stratum 13. The end of Stratum 12B is more easily ascertained: constrained with the help of overlying strata, the destruction of the elite residence is placed 1218–1172 BC (68.3% highest posterior density, hpd). The subsequent rebuild of the residence (Str. 12A), though lacking direct data, evidently belongs to the first half of the 12th century BC, and soon gave way to the completely new architecture of Stratum 11 (Start, 1183–1136 BC, 68.3% hpd). Stratum 11 characterised the second half of the 12th century BC, with the modifications of Stratum 10 continuing into the first part of the 11th century BC (10B: 1116–1077 and 10A: 1090–1048, 68.3% hpd). The destruction of Stratum 10A is estimated at 1080–1021 BC (68.3% hpd).

Intermediary Stratum 9, though represented by just one direct data point, is essentially constrained to the second part of the 11th century BC. The transformation of Gezer in Stratum 8, with the erection of fortifications and the Courtyard-type Administrative Building, likely began in the early part of the 10th century BC (998–957 BC, 68.3% hpd). If the two outliers Beta-436538 and Beta-436540 are included in the model (i.e. down-weighted rather than omitted), the start boundary of Stratum 8 includes the late 11th century BC (Model A: 1041–967, 68.3% hpd). Stratum 8 was used during the first part of the 10th century BC, until its destruction near the middle of the century (969–940 BC, 68.3% hpd). While we would ideally like to have additional radiocarbon dates for Stratum 8, the chronological position of this horizon is hard to dispute thanks to constraint provided by overlying Stratum 7.

Stratum 7, with its shift to domestic architecture in the gate area, was used primarily during the later part of the 10th century BC. It was not particularly long-lived, as the site once again fell prey to a destructive event near the close of the 10th century BC or early decades of the 9th century BC (927–885, 68.3% hpd).

- from Webster et al. (2023:21-22)

- links take you to online version of this paper

The existence and effect of small radiocarbon offsets relative to the calibration curve have recently been a focus of investigation [139–143]. These can arise due to differences in region and growing season of the dated sample compared to the northern hemisphere tree data underlying IntCal; a further contribution can also come from measurement factors (e.g. AMS versus decay-counting). How the regional and growing offsets varied through time is not yet well understood, but all evidence indicates they are small in magnitude, around one to two decades at most. S2 Fig provides a test case whereby a hypothetical offset of 19±5 years is applied to Model B, by using the Delta_R function to shift dates before calibration. 19±5 years is likely an over-estimate, noting that most measurements were made on olive pits, which have a similar (summer) growing season to the northern hemisphere trees underlying IntCal20. The effect of such an offset on the Gezer results is modest, shifting results later by not more than a few decades.

- from Webster et al. (2023:22-27)

- links take you to online version of this paper

The new radiocarbon series from the Tandy expedition allows us to better establish the absolute chronology of Gezer from the close of the LBA through Iron Age IIA. Since relatively few sites in this region were continuously occupied during the LBA to Iron Age transition (and even fewer of these are well-dated with radiocarbon), a key contribution is made to understanding the archaeology of the Shephelah and coastal plain. Gezer’s strategic position and frequent appearance in textual sources, and the availability of a radiocarbon-based chronology for Egypt, provides a rather unique opportunity to re-examine the impact on Gezer of the complex political changes that occurred in the region during the LBA to Iron Age transition. Bearing in mind the limitations of texts and questions of historicity, we may use the independent radiocarbon chronology of Gezer to test–from a strictly chronological point-of-view–the viability of proposed direct correlations between archaeological remains and recorded events or phenomena.

Fig 11 summarises the 14C-based dates of stratigraphic transitions at Gezer (using the preferred Model B), plotting them alongside radiocarbon results from other southern Levantine sites as well as the 14C-based and traditional accession dates for Egyptian rulers Ramesses II through Sheshonq I. Note that the New Kingdom model follows Dee [3] and Manning [4] and has been updated with IntCal20 [137]. Combining radiocarbon data with known regnal order and lengths (but no traditional absolute data), the model assumes Aston’s ultra-high reign lengths for Thutmoses III through Ramesses II [144], and reign lengths from Schneider [145] for all other rulers. 14C-based results from other southern Levantine sites were obtained using single-site models, for which OxCal code and data references are provided in S1 Appendix.

Radiocarbon data from the Tandy excavation confirms that Gezer was continuously occupied from the 13th through 10th centuries BC, despite multiple disruptive events and rebuilding episodes. The elite residency of Stratum 12B, with its signs of wealth and links to Egypt, provides a window on Gezer during the 13th century BC that is currently only available in this part of the site. The sudden and fiery destruction of this building, in which multiple individuals were killed, occurred in the timeframe 1218–1172 BC (68.3% hpd; or 1244–1148 at 95.4% hpd). The impact of the event on the rest of the town is uncertain, though it may also have left traces in Field II. Various human or natural causes could be invoked to explain the destruction, but we note that the date is compatible with Merneptah’s campaign and his claim to have conquered Gezer (Fig 11). The 14C-based Egyptian model puts his accession at 1241–1219 BC (95.4% hpd) and that of Seti II at 1232–1209 (95.4% hpd). (Models using other reign length assumptions yield similar or slightly higher accession dates for these rulers.) Using the traditional approach to Egyptian chronology, Kitchen would date Merneptah’s reign at 1213–1203 BC [146], while Schneider would place it at 1224–1214 BC [145]. Applying a hypothetical offset of 19±5 year tends to weaken the fit between the Stratum 12B destruction (1198–1152 BC, 68.3% hpd; 1213–1131, 95.4% hpd) and Merneptah, whose reign in the Egyptian 14C-based model does not change by more than a few years.

The destruction of Stratum 12B fits well with radiocarbon data for destructive/disruptive events at other sites in the southern Levant [2]. It is notably similar to the destruction of Lachish–another major LBA city-state just 33 km to the south. Lachish Level VII shows evidence of widespread destruction and is well-dated by radiocarbon to 1218–1191 BC (68.3% hpd; Fig 11) [2]. While the direct causes of destruction or disruption at individual sites probably varied, and the events may have been separated by some years, the overall pattern is commonly viewed as part of a period of turmoil (the so-called ‘Crisis Years’) that affected the wider eastern Mediterranean region [147, 148]. Merneptah’s campaign and attempts to retain control of the southern Levant, appear to be a response to city-states and towns who were rebelling against Egyptian rule. Lachish is not mentioned by Merneptah but given its importance and proximity to Gezer we may speculate that it joined the rebellion or was targeted for its loyalty to Egypt; the latter is perhaps suggested by the strengthening Egyptian influence evident in the architecture and material culture of subsequent Level VI [149].

Gezer evidently recovered quickly with the rebuild of Stratum 12A in the first part of the 12th century BC. The site’s status within the next (last) phase of Egyptian rule in the southern Levant is uncertain, but it does not appear to have had the elevated status of sites like Lachish (VI) and Azekah, which show accumulating wealth and strengthened ties with the Egyptian administration [150]. Perhaps for this reason, Gezer did not share the fate of Lachish and Azekah, which suffered impressive site-wide destructions in the second part of the 12th century BC, after which they were abandoned for more than a century [2, 91, 108, 150, 151].

The Tandy excavation shows a substantial re-organization and planning of the city quarter and construction of a city wall in the timeframe 1183–1136 BC (68.3% hpd, Start Stratum 11). In this new setting, we see the arrival of so-called ‘Philistine’ pottery at Gezer, as type 2 / bichrome. Assuming the ware was indeed associated with the founding and main use of Stratum 11, the radiocarbon result suggests this pottery may have reached Gezer around the mid-12th century BC. It was almost certainly present by the last decades of the century (Stratum 11 phase estimate: 1162–1112 BC, 68.3% hpd).

Gezer provides one of the most robust 14C-based estimates currently available for Philistine 2 pottery and its first occurrence at the borders of Philistia. The result closely matches recent 14C results from Ashkelon (Start 19B: 1173–1131 BC, 68.3% hpd) [111] and is compatible with Tell es-Safi (Gath) (Start A6: 1220–1138 BC, 68.3% hpd) (Fig 11) ([104], see analysis in [2]). Available data from Tel Miqne (Ekron) and Beth Shemesh give distinctly lower estimates for the strata in which Philistine 2 pottery first appear: Start Miqne VIB at 1118–1059BC and Start Beth Shemesh 6 at 1081–989 BC (both 68.3% hpd). However, a close review (for details, see [2]) suggests that the discrepancy may be due to data limitations: key strata at Tel Miqne are represented by single contexts [98], and measurements for Level 6 at Beth Shemesh come from a single olive pit [152].

Occupation at Gezer continued well into the 11th century BC. There are indications of multiple disruption episodes in other parts of the site that are contemporary with Strata 11–10, notably Field VI (local Str. 6 ‘Granary’ and local Str. 5 Courtyard Houses) [50]. Unfortunately, these lack 14C data, but they may reflect Gezer’s position during Iron I, in a border/conflict region between emerging polities. In the southern part of the Gezer mound, destruction came in the timeframe 1080–1021 BC (68.3% hpd; or 1097–999 at 95.4% hpd), with the end of Tandy Stratum 10 (Stratum IX). This event seems to have been site-wide, reflected in nearby Field VII, local Str. 8 and perhaps also Field VI, local Str. 4.

HUC’s correlation of Stratum IX with Solomon’s era or Siamun, judged solely from the chronological point-of-view, seems improbable. The end of Tandy Stratum 10A is estimated by 14C within the 11th century BC, contemporary with the 21st Dynasty of Egypt but too early for Solomon by any estimate. There is limited overlap with the 14C-based estimate for the accession year of Siamun (1019–977 BC, 95.4% hpd) and none with traditional estimates for his reign (978–959 BC [146] or 995–976 BC [145]). Aside from any specific historical association at Gezer, the Tandy 14C results indicate that stamp seal impressions of the type found in the destruction can predate the reigns of Siamun and Sheshonq I. Indeed, the latest analysis of these seals associates them more broadly with the 21st Dynasty (i.e. 1110–945 BC, 95.4% hpd by the 14C Egyptian chronology) [153].

The construction of Stratum VIII (Tandy Stratum 8) likely occurred in the first part of the 10th century BC (Start 8: 998–957 BC, 68.3% hpd; 1023–942 BC, 95.4% hpd). The data and model–with constraints provided by overlying Stratum 7 –rule out a 9th century BC date for Stratum VIII (contra [81, 85–88]). The start of Stratum 8 provides an estimate for the Iron I to IIA material culture transition in this geographic area. The transition cannot be later than Stratum 8, since this horizon is unambiguously Iron IIA, however it could (at least in theory) be slightly earlier since the attribution of intermediate Stratum 9 may be Iron I or Iron IIA. The results for Strata 9 and 8 fit acceptably with 14C results from transitional Iron I/IIA strata at other sites in the same region: Khirbet Qeiyafa [91, 109, 110], Khirbet al-Rai (Level VII) [91] and Beth Shemesh (Level 4) [106, 107]. Note that the boundaries shown in Fig 11 were calculated using independent single-site models that do not equate strata a priori based on pottery (cf. [154]). The earlier dates for the Iron I to IIA transition emerging from southern sites stand in contrast to later estimates from sites in the north such as Dor [98] and Rehov [103], suggesting the need for a more nuanced approach to the chronology of this period that explores potential delays in material culture change in different parts of the country.

The Iron I/IIA transition sees the onset of monumental buildings and fortifications indicative of central administration and the development or expansion of polities. Notably, radiocarbon shows that the phenomena appeared at Gezer and Khirbet Qeiyafa in a similarly early timeframe: late 11th or early 10th century BC. The start of Khirbet Qeiyafa should be treated somewhat cautiously since this is a single occupation horizon (thus with less constraint available for modelling) and most of the dates likely pertain to the later part of the stratum; nonetheless the founding of this well-fortified site, like Gezer, cannot date beyond the first part of the 10th century BC. Other 14C-dated strata with indications of central administration may be somewhat later. The nature and fortification of Lachish V is disputed [91, 155–157] and its start date is not well-defined by 14C, but probably falls in the 10th century BC [2, 91]. More definitive evidence of central administration at Lachish (Level IV) and Beth Shemesh (Level 3) is 14C-dated to the second part of the 10th or first part of the 9th century BC (Fig 11). The radiocarbon evidence thus suggests a prolonged process of expansion in the Shephelah.

The Shephelah region during the Iron I and Iron IIA is generally seen as a ‘middle ground’ between coastal (‘Philistine’) and highland polities [158]. Bunimovitz and Lederman define this region as a buffer zone that experienced “alternating prosperity and decline” [159]. Some scholars have discussed ‘Canaanite resistance’ [160] or a ‘Canaanite enclave’ [90] in the Shephelah, though identities are speculative and hard to access archaeologically; indeed, at a border site such as Gezer, identities or political alignments may have changed multiple times. To explain the growth in settlements and appearance of sites with monumental architecture and fortifications during Iron IIA, various models have been proposed: a westward expansion of a nascent Judah [89–91, 161] or another polity based in Jerusalem or the Benjamin Plateau [92, 93], formation of localised chiefdoms [162], the economic influence of the strong coastal (‘Philistine’) site of Gath [163], or a combination of these factors. The 10th century BC 14C-based date for early expansion in the Shephelah notably rules out an association with the northern Israelite Omride dynasty (contra [88]), however it is chronologically compatible with Saul, David and/or Solomon, whose text-based dating (albeit approximate) falls in the 10th century BC (perhaps also the late 11th century BC). While scholars can debate the degree to which the accounts of these early highland rulers reflect historical memories, extra-biblical evidence indicates they were real historical figures [164–166], and most scholars see an early historical foundation to the later narrative development of the texts [167–172].

We propose that Gezer Stratum VIII represents a shift in political alignment of the city, corresponding to current models of state development in the region during the Iron Age IIA. (For a recent summary of the various theories of state development see [173]). The Tandy excavation directors consider that the most logical historical reconstruction based on the archaeological remains and 14C dates is the westward expansion of a nascent Judah already in the 10th century BC (cf. [174] and [175] which confine Judah’s expansion to the 9th century BC). The refined dating of Stratum 7 demonstrates that the Aijalon Valley was still a contested area at the end of the 10th century BC and that the polity represented by the Stratum 8 monumental city was short-lived.

Stratum 8 came to an end already in the mid-10th century BC (969–940 BC at 68.3% hpd; or 991–930 BC at 95.4% hpd). Radiocarbon suggests that Khirbet al-Rai and perhaps also Khirbet Qeiyafa were destroyed before Gezer Stratum 8 (Fig 11), consistent with the pottery evidence. The pottery assemblages at Khirbet Qeiyafa and Khirbet al-Rai are classified by the excavators as early Iron IIA [176, 177] but by other scholars as Iron I [178, 179] or transitional Iron I/IIA [154].

A comparison of the Stratum 8 destruction with the traditional and radiocarbon-based chronologies of Sheshonq I shows that this stratum may have come to an end during his reign (Fig 11). A 14C-based estimate for Sheshonq I puts his accession at 988–945 BC (95.4%) and the end of his reign at 967–934 BC (95.4%). (The traditional Egyptian chronology puts Sheshonq I’s reign at 945–924 BC [146] or 962–941 BC [145].) We do not, however, reach good agreement between 14C-based dates for Stratum 8 and Sheshonq I on the one hand, and the commonly cited historical-biblical date for Shishak’s campaign on the other: 925 BC based on Rehoboam’s 5th year and synchronisms between later Israelite/Judahite reigns and Assyrian chronology. The discrepancy is modest, however: <10 years at 95.4% and <20 years at 68.3%. This is insufficient to rule out a convergence of the Egyptian sources, the Bible and radiocarbon, since we are conscious that:

- There may well be leeway of 10–20 years for the Stratum 8 to 7 transition, given the limited number of Stratum 8 measurements.

- There is room to debate the biblical date for Shishak’s campaign. Estimates for the 5th year of Rehoboam are generally placed between ca. 930 and 915 BC [180–183] but one could potentially argue for dates as high as ca. 970 BC [184].

- Sheshonq I is located at the tail end of the New Kingdom radiocarbon model. The quantity of 14C data for the 21st Dynasty is limited (13 dates, of which 9 are from one reign: Amenemnisu) and small inaccuracies in New Kingdom reign lengths (often based on maximum attested regnal years) could cumulatively pull this reign too high.

The 14C-based results from Stratum 7 open another possibility for correlation with Shishak / Sheshonq I. The end boundary (927–885 BC, 68.3% hpd) includes the common biblical date for Shishak’s campaign, but does not fit well with current 14C-based estimates for Sheshonq I. In any case, the previously held historical association of Stratum 7 with the Aramean ruler Hazael in the second part of the 9th century BC is firmly ruled out. The end boundary does not include the highest historical date for the campaign (ca. 830 BC) even at 95.4% hpd (970–857 BC). Comparison with 14C data at other sites shows that the event is unlikely to be contemporary with destructions at Tell es-Safi (Gath) and Tel Zayit Level I (Fig 11). There is minimal overlap at 68.3% between the end boundaries of Stratum 7 and Tell es-Safi Level A3, and none with Tel Zayit Level I even at 95.4% hpd. Unlike the situation at Gezer, the 14C evidence at Gath–the only city specifically mentioned in 2 Kings 12:17 as having been attacked by Hazael–converges well with Hazael’s campaign: a simple Bayesian model places the end of Tell es-Safi A3 at 887–798 BC (68.3% hpd). The Tel Zayit Level I destruction dates as much as a century after Tandy Stratum 7, perhaps even later than Hazael’s reign (end of Level I: 796–772 BC, 68.3% hpd). These outcomes raise caution concerning the tendency in scholarship to tightly group destruction layers based on pottery and historical sources; in reality these events may be associated with a wider variety of conflicts (recorded and unrecorded) and spread over a longer period of time. For Tandy Stratum 7, we ought to consider other skirmishes between Judah, Israel and their neighbors during the late 10th and early 9th centuries BC (e.g. 1 Kings 15:16–22), as well as non-military causes.

Gezer does not seem to have suffered any major destruction between ca. 900 BC and the second part of the 8th century BC. The town may have been much reduced in size and importance during this time and, given the earlier-than-expected date of Stratum 7, we should consider whether there was an occupation gap (at least on the southern edge of the site) between Tandy Strata 7 and 6.

For the date of Stratum 6 we must rely for now on the evidence of the pottery and finds [35]. In view of the higher-than-expected date for Stratum 7, adding 14C data for Stratum 6 may in fact be worthwhile, helping to assess its founding date and confirming that the destruction did not occur substantially before 734 BC (e.g. early 8th century BC, before the Hallstatt Plateau).

A debate over the Iron Age at Gezer arose during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Several scholars challenged the outer wall conclusions of the HUC excavations: Kempinski (1972, 1976) and Kenyon (1977) in their reviews of Gezer I (Dever, Lance, and Wright 1970) and Gezer II (Dever 1974), followed a few years later by Zertal (1981), Finkelstein (1981), and Bunimovitz (1983). Most proposed that the outer wall dated to the Iron Age IIB, although Kenyon dated the wall to the Hellenistic period and Zertal to the post-Assyrian period. During the 1990s an issue of Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research focused on the archaeology of Solomon. While the archaeological data of the Iron Age was primarily discussed, the debate centered on methods and historical correlations. This was the foreshadowing of the “low chronology” proposal that came five years later.

While the issues and debates associated with Solomon at Gezer are complex, some summary observations are in order. Most scholars date the fortifications to the Iron Age period. Most note that the two wall lines (casemate and outer wall) as well as the two gates are an integrated system of defense. Scholars are divided as to whether there are two phases (tenth century and a later rebuilding during the ninth or eighth centuries B.C.E.) or only one. Dever attempted to answer the critics by conducting two single-season excavations in 1984 and 1990, but it is clear that these were not adequate to address the complex stratigraphic issues of Tel Gezer. These stratigraphic issues are compounded by later Hellenistic rebuilding and Macalister’s excavations.

- from Fall et al. (2023)

Table 1

Table 1Traditional and revised Early and Middle Bronze Age chronologies for the Southern Levant. (Traditional chronology based on Dever 1992; Levy 1995:fig. 3; revised chronology based on Regev et al. 2012; Fall et al. 2021; Höflmayer and Manning 2022.)

Fall et al. (2023)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

- Fig. 3 Photo/Plan of fields

III and VII (South Gate) from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 3

Fig 3

Aerial view of the Tandy excavations, with a wide exposure of iron age strata on the central-southern edge of the Gezer mound between fields VII and III of Hebrew Union College.

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Plan of Stratum 12B

elite residence in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 4

Fig 4

Plan of Tandy excavation stratum 12B elite residence with radiocarbon dated contexts marked. The insert shows Individual #3.

Webster et al. (2023)

- Fig. 3 Photo/Plan of fields

III and VII (South Gate) from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 3

Fig 3

Aerial view of the Tandy excavations, with a wide exposure of iron age strata on the central-southern edge of the Gezer mound between fields VII and III of Hebrew Union College.

Webster et al. (2023) - Fig. 4 Plan of Stratum 12B

elite residence in South Gate area from Webster et al. (2023)

Fig 4

Fig 4

Plan of Tandy excavation stratum 12B elite residence with radiocarbon dated contexts marked. The insert shows Individual #3.

Webster et al. (2023)

Webster et al. (2023:9) report that the Stratum 12 B Building