| Introduction |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

| Jerash - Introduction |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

| Jerash - North Gate |

unlikely to possible |

|

Russell (1985)

speculated that a civic dedication found from the north gate of Jerash may reflect imperial aid

Roman Emperor Trajan supplied to aid reconstruction after a disastrous earthquake.

Kraeling (1938:47) dated construction of the new north gate

of Jerash to 115 CE based on a dedicatory inscription. Kraeling (1938:401)

discovered the inscription in 6 fragments which once reassembled referred to Trajan as the savior and founder of the city. However,

Kraeling (1938:47) attributed the

dedication to the improvement of the roads out of Jerash; in particular the Road to Pella

which enabled direct connections to the coastal cities of Caesarea and

Ptolemais (aka Acre). This contention may be supported by the plan

of the north gate whose northern face is angled towards Pella. If the

Incense Road

Earthquake was caused by a fault break on the Araba fault, seismic damage at Jerash would likely have been light. |

| Heshbon |

possible |

≥ 8 |

Stratum 14 Earthquake (Mitchel, 1980) - 1st century BCE - 2nd century CE

Mitchel (1980) identified a destruction layer in Stratum 14

which he attributed to an earthquake. Unfortunately, the destruction layer is not precisely dated. Using some assumptions,

Mitchel (1980) dated the

earthquake destruction to the 130 CE Eusebius Mystery Quake,

apparently unaware at the time that this earthquake account may be either

misdated as suggested by Russell (1985) or mislocated as

suggested by Ambraseys (2009).

Although Russell (1985) attributed the destruction layer

in Stratum 14 to the early 2nd century CE Incense Road Quake, a number of

earthquakes are possible candidates including the 31 BCE Josephus Quake.

Mitchel (1980:73) reports that a

majority of caves used for dwelling collapsed at the top of

Stratum 14 which could be noticed by:

bedrock surface channels, presumably for directing run-off water into storage facilities, which

now are totally disrupted, and in many cases rest ten to twenty degrees

from the horizontal; by caves with carefully cut steps leading down into

them whose entrances are fully or largely collapsed and no longer

usable; by passages from caves which can still be entered into formerly

communicating caves which no longer exist, or are so low-ceilinged or

clogged with debris as to make their use highly unlikely — at least as

they stand now.

Mitchel (1980:73) also noticed

that new buildings constructed in Stratum 13 were leveled over a jumble of broken-up bedrock .

Mitchel (1980:95) reports that Areas B and D

had the best evidence for the massive bedrock collapse - something he attributed to the "softer" strata in this area, more prone to

karst features and thus easier to burrow into and develop underground dwelling structures.

Mitchel (1980:96) reports discovery of a coin

of Aretas IV (9 BC – 40 AD) in the fill of silo D.3:57 which he suggests was placed as part of reconstruction

after the earthquake. Although Mitchel (1980:96)

acknowledges that this suggests that the causitive earthquake was the 31 BCE Josephus Quake,

Mitchel (1980:96)

argued for a later earthquake

based on the mistaken belief that the

31 BCE Josephus Quake had an epicenter in the Galilee.

Paleoseismic evidence from the Dead Sea, however, indicates that the

31 BCE Josephus Quake had an epicenter in the vicinity of the

Dead Sea relatively close to Tell Hesban. Mitchel (1980:96-98)'s

argument follows:

The filling of the silos, caves, and other broken—up bedrock installations at the end of the Early Roman period was apparently carried out

nearly immediately after the earthquake occurred. This conclusion is based on the absence of evidence for extended exposure before filling

(silt, water—laid deposits, etc.), which in fact suggests that maybe not even one winter's rain can be accounted for between the earthquake

and the Stratum 13 filling operation. If this conclusion is correct, then the Aretas IV coin had to have been introduced into silo D.3:57

fill soon after the earthquake. which consequently could not have been earlier than 9 B.C.

The nature of the pottery preserved on the soft, deep fills overlying collapsed bedrock is also of significant importance to my argument

in favor of the A.D. 130 earthquake as responsible for the final demise of underground (bedrock) installations in Areas B and D.

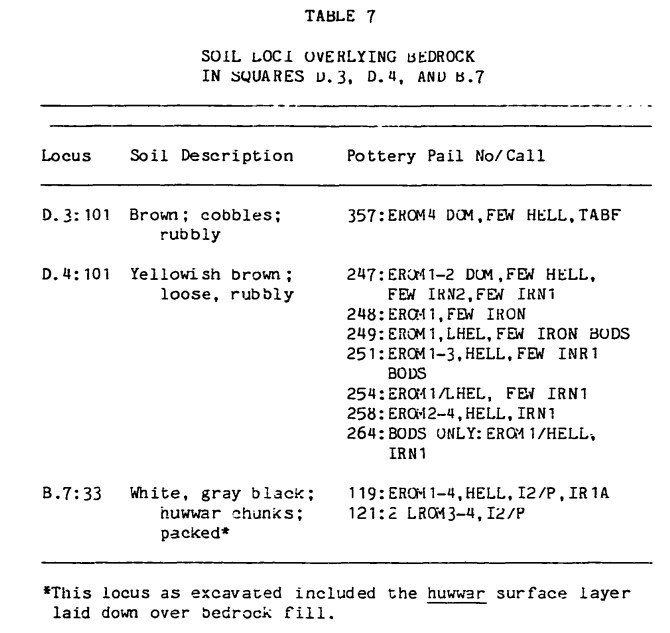

Table 7

provides a systematic presentation of what I consider to be the critical ceramic evidence from loci in three adjacent squares,

D.3, D.4, and B.7. The dates of the latest pottery uniformly carry us well beyond the date of the earthquake which damaged Qumran,

down, in fact, closer to the end of the 1st century A.D. or the beginning of the 2nd.

In addition to these three fill loci, soil layer D.4:118A (inside collapsed cave D.4:116 + D.4:118) yielded Early Roman I-III sherds,

as well as two Late Roman I sherds (Square D.4 pottery pails 265, 266). Contamination of these latter samples is possible, but not

likely. I dug the locus myself.

Obviously, this post-31 B.C. pottery could have been deposited much later than 31 B.C.. closer, say, to the early

2nd century A.D., but the evidence seems to be against such a view. I personally excavated much of locus D.4:101

(Stratum 13). It was a relatively homogeneous, unstratified fill of loose soil that gave all the appearances of

rapid deposition in one operation. From field descriptions of the apparently parallel loci in Squares D.3 and B.7.

I would judge them to be roughly equivalent and subject to the same interpretation and date. And I repeat, the

evidence for extended exposure to the elements (and a concomitant slow, stratified deposition) was either missed

in excavation, not properly recorded, or did not exist.

This case is surely not incontrovertible but seems to me to carry the weight of the evidence which was excavated at Tell Hesban.

Mitchel (1980:100)'s 130 CE date for

the causitive earthquake rests on the assumption that the "fills" were deposited soon after bedrock collapse. If one discards this assumption,

numismatic evidence and ceramic evidence suggests that the "fill" was deposited over

a longer period of time - perhaps even 200+ years - and the causitive earthquake was earlier. Unfortunately, it appears that the terminus ante quem

for the bedrock collapse event is not well constrained. The terminus post quem appears to depend on the date for lower levels of Stratum 14 which seems to have

been difficult to date precisely and underlying Stratum 15

which Mitchel (1980:21) characterized as

chronologically difficult.

|

| Caesarea |

possible |

6-7 |

Late 1st/ Early 2nd century CE Earthquake

Using ceramics, Reinhardt and Raban (1999) dated

a high energy subsea deposit inside the harbor

at Caesarea to the late 1st / early 2nd century CE. This, along with other supporting evidence, indicated that the outer harbor breakwater must have

subsided around this time. They attributed the subsidence to seismic activity.

L4 — Destruction Phase

The first to second century A.D. basal rubble unit (L4) was found on the carbonate cemented sandstone bedrock (locally known as kurkar)

and was characteristic of a high-energy water deposit (Fig. 2

). The rubble was framework supported with little surrounding matrix

and composed mainly of cobble-sized material, which was well rounded, heavily encrusted (e.g., bryozoans, calcareous algae), and

bored (Lithophaga lithophaga, Cliona) on its upper surface. The rubble had variable lithologies including basalts, gabbros, and

dolomites, all of which are absent on the Israeli coastal plain and were likely transported to the site as ship ballast (probably from Cyprus).

The surrounding matrix was composed of shell material (mainly Glycymeris insubricus), pebbles, and coarse sand.

The pottery sherds found in this unit were well rounded, encrusted, and dated to the first to second century A.D. The

date for this unit and its sedimentological characters clearly records the existence of high-energy conditions within the inner

harbor about 100-200 yr after the harbor was built. This evidence of high-energy water conditions indicates that the outer

harbor breakwaters must have been severely degraded by this time to allow waves to penetrate the inner confines of the harbor (Fig. 3, A and B).

Indication of the rapid destruction of the outer harbor breakwaters toward the end of the first century A.D. is derived from additional data

recovered from the outer harbor. In the 1993 season, a late first century A.D. shipwreck was found on the southern submerged breakwater.

The merchant ship was carrying lead ingots that were narrowly dated to A.D. 83-96 based on the inscription "IMP.DOMIT.CAESARIS.AUG.GER."

which refers to the Roman Emperor Domitianus (Raban, 1999). The wreck was positioned on the harbor breakwater, indicating that this

portion of the structure must have been submerged to allow a ship to run-up and founder on top (Raban, 1999; Fig. 3B). Because

Josephus praised the harbor in grand terms and referred to it as a functioning entity around A.D. 75-79, and yet portions of the

breakwater were submerged by A.D. 83-96, we conclude that there was a rapid deterioration and submergence of the harbor, probably

through seismic activity.

Later they suggested that the subsidence had a neotectonic origin.

Evidence for neotectonic subsidence of the harbor has been reinforced by separate geologic studies (stratigraphic analysis of boreholes,

Neev et al., 1987; seismic surveys, Mart and Perecman, 1996) that recognize faults in the shallow continental shelf and in the proximity of Caesarea;

one fault extends across the central portion of the harbor. However, obtaining precise dates for movement along the faults is difficult.

Archaeological evidence of submergence can be useful for dating and determining the magnitude of these events:

however, at Caesarea the evidence is not always clear.

Neotectonic subsidence is unlikely. As pointed out by

Dey et al(2014), the coastline appears to have been stable for the past ~2000 years

with sea level fluctuating no more than ± 50 cm, no pronounced vertical displacement of the city's Roman aqueduct

( Raban, 1989:18-21), and harbor constructions

completed directly on bedrock

showing no signs of subsidence. However,

Reinhardt and Raban (1999)

considered more realistic possibilities for submergence of harbor installations such as seismically induced liquefaction, storm scour, and tsunamis.

The submergence of the outer harbor break-waters at the end of the first century A.D. could have also been due to seismic liquefaction of the sediment.

Excavations have shown that the harbor breakwaters were constructed on well-sorted sand that could have undergone

liquefaction with seismic activity. In many instances the caissons are tilted (15°-20° from horizontal; Raban et al., 1999a) and at different elevations,

which could be due to differential settling (area K; Fig. 1). However, the tilting could also be due to undercutting by current scour from large-scale

storms (or tsunamis) and not exclusively seismic activity.

Our data from the inner harbor cannot definitively ascribe the destruction of the harbor at the end of the first century A.D. to a seismic event,

although some of the data support this conclusion. However, regardless of the exact mechanism, our sedimentological evidence from the inner harbor

and the remains of the late first century A.D. shipwreck indicate that the submergence of the outer breakwater occurred early in the life of the

harbor and was more rapid and extensive than previously thought.

Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015) examined and dated cores taken seaward of the harbor and identified 2 tsunamite deposits

(see Tsunamogenic Evidence) including one which dates to

to the 1st-2nd century CE. Although, it is tempting to correlate the 1st-2nd century CE tsunamite deposits of

Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015) to the L4 destruction phase identified in the harbor (

Reinhardt and Raban, 1999), the chronologies presented

by Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015) suffer from some imprecision

due to the usual paucity of dating material that one encounters with cores. Further, the harbor subsidence and breakwater degradation dated by

Reinhardt and Raban (1999)

may not have been caused by seismic activity. If it was related to seismic activity,

the early 2nd century CE Incense Road Quake is a better

candidate than the 115 CE Trajan Quake

because it would have produced higher intensities in Caesarea.

Fritsch and Ben-Dor (1961) reported the following from an early underwater exploration of Caesarea's harbor.

At the very deepest spot where the airlift penetrated, beneath huge

stone blocks which teetered precariously above the divers' heads, was uncovered a large wooden beam. Beneath its protective cover the divers found

the only whole amphora of our dig. This proved to be a second century

Roman vessel. The fact that it was found under the tumbled beam and

masonry would indicate that these things were catapulted into the sea at

the same time. Since there is a strong earthquake recorded in the area of

Caesarea in the year A.D. 130, it may possibly be that the harbor installations of Herod were destroyed at that time.

Other finds recovered from the original bottom, now under fifteen

feet of sand, included numerous sherds of second century amphorae, corroded bronze coins, ivory hairpins, colorful bits of glass and other objects

of the Roman period. Two objects were of special significance. One was a

small lead baling seal with a standing winged figure. It has a pinpoint hole

near its center, and a rather deep, depressed line on the back of it, as though

made by a wire.3

The other object was probably the most important thing discovered at

Caesarea this past summer. It was a small commemorative coin or medal

made of an unidentified alloy, about the size of a ten-cent piece, with two

holes drilled through it as if it might have been worn as a pendant. Upon

the face of it there is the representation of the entrance to a port flanked

by round stone towers surmounted by statues. Arches border the jetty on

either side of the towers, and two sailing vessels are about to enter the

harbor. Two letters, KA, may well be the abbreviation for the word Caesarea. The other side of the coin shows the figure of a male with a long beard

and a tail like a dolphin, with a mace-like object in his hand. Coin experts

who have seen this piece agree that it is unique, and that it undoubtedly

depicts the ancient port of Caesarea. It may have been issued to commemorate some important occasion at Caesarea in the first or second century A.D.

Footnotes

3. This object may be an amulet, the winged figure representing Horus, the Egyptian sun

god who wards off lurking evils. Cf. E.A.W. Budge, Amulets and Superstitions (London, 1930) 166.

A close examination of the original piece, however, leads one to conclude that it is a baling seal.

|

| Masada |

possible |

≥ 8 |

Masada may be subject to seismic amplification due to a topographic or ridge effect as well as a

slope effect for those structures built adjacent to the site's steep cliffs.

2nd - 4th century CE Earthquake

Netzer (1991:655) reports that a great earthquake [] destroyed

most of the walls on Masada sometime during the 2nd to 4th centuries CE.

In an earlier publication, Yadin (1965:30) noted that the

Caldarium was filled as a result of earthquakes by massive debris of stones .

Yadin concluded that the finds on the floors of the bath-house represent the last stage in the stay of the Roman garrison at Masada .

The stationing of a Roman Garrison after the conquest of Masada in 73 or 74 CE

was reported by Josephus in his Book

The Jewish War where he says in Book VII Chapter 10 Paragraph 1

WHEN Masada was thus taken, the general left a garrison in the fortress to keep it, and he himself went away to Caesarea; for there were now no enemies

left in the country, but it was all overthrown by so long a war.

Yadin (1965:36)'s evidence for proof of the stationing of the Roman garrison follows:

We have clear proof that the bath-house was in use in the period of the Roman garrison - in particular, a number of "vouchers" written in Latin and coins

which were found mainly in the ash waste of the furnace (locus 126, see p. 42). Of particular importance is a coin from the time of Trajan,

found in the caldarium, which was struck at Tiberias towards the end of the first century C.E.*

The latest coin discovered from this occupation phase was found in one of the northern rooms of Building VII and dates to 110/111 CE (Yadin, 1965:119)**.

Yadin (1965:119) interpreted this to mean that, this meant that the Roman garrison stayed at Masada at least till the year 111 and most probably several years later.

Russell (1985) used this 110/111 coin as a

terminus post quem for the

Incense Road Earthquake while using a dedicatory inscription at Petra for a

terminus ante quem of 114 CE.

Footnotes

*Yadin (1965:118) dated this coin to 99/100 CE -

This would be coin #3808 -

Plate 77 - Locus 104 -

Caldrium 104 - Square 228/F/3

**perhaps this is coin #3786 which dates to 109/110 CE -

Plate 77 -

Locus 157 - Building 7 Room 157 - Square 208/A/10

|

| Khirbet Tannur |

possible |

≥ 8 |

End of Period I Earthquake - 1st half of 2nd century CE - Glueck (1965:92) found Altar-Base I from Period I severely damaged

probably by an earthquake which may have precipitated the rebuild that began Period II.

McKenzie et al (2013:47) dated Period II construction, which would have occurred soon after the End of Period I

earthquake, to the first half of the 2nd century CE.

McKenzie et al (2002:50) noted that a bowl found underneath paving stones that were put in place soon before Period II construction

dates to the late first century CE along with two other bowls which date to the first half of the second century CE.

This pottery and comparison to other sites led them to date Period II construction to the first half of the second century CE. |

| Emmaus/Nicopolis |

no evidence |

|

There is no evidence that I am aware of |

| Aqaba/Eilat - Introduction |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

| Aqaba - Aila |

probable |

≥ 8 |

Earthquake VII - Nabatean/Early Roman - Early 2nd century CE - Earthquake VII was dated to the second century CE from

Nabatean pottery

found in the collapse layer and the layer below.

There is a question whether the collapse layer was caused by human agency or earthquake destruction. The Romans annexed Nabatea in 106 CE and the authors

noted that there is debate about the degree of Nabataean resistance to the annexation that might have resulted in destruction by human agency in this period

(Bowersock 1983: 78-82; Parker 1986: 123-24; Fiema 1987; Freeman 1996) .

Nonetheless,

Thomas et al (2007) noted that a complete section of

collapsed wall might suggest earthquake destruction . |

| Petra - Introduction |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

| Petra - el-Katute |

possible |

≥ 7 |

1st century CE Destruction -

Parr (1960:129) reports a partial destruction of interior walls from a

building outside of the

"monumental structure" at Katute. A tentative 71 CE terminus ante quem for the date of destruction

is suggested from numismatics.

Parr, P. J. (1960:129), reported the following from excavations at Trench I in Katute:

Only in two restricted areas, both outside the building, have the original floors been reached, and until more evidence

is forthcoming the date of its construction must remain uncertain. But from the secondary surfaces within the building,

some of them laid down after the partial destruction of the interior walls, a series of coins gives a firm date for the

latest occupation of the structure. Of eight coins so far studied, two are of

Malichus II and Shaqilath II

(c. A.D. 40-71), five are of Rabbel II and

Gamilath (A.D. 71-106, but late in the period, since Gamilath is Rabbel's second consort),

and one is of Rabbel with either Shaqilath or Gamilath, this being uncertain. The significance of these coins is

increased when it is noted that four of Rabbel II and Gamilath come from the same layer of make-up

beneath one of the secondary floors. There can be little doubt, therefore, that the building was in use at

the end of the 1st century A.D., and probably right up until the Roman conquest of A.D. 106,

though the apparent lack of Roman Imperial coins suggests that it soon feel out of use then.

Judging from the fact that the secondary surfaces from which the coins come in some cases seal the first destruction

levels of the building, a date in the first half of the 1st century A.D. for its construction is not,

perhaps, unlikely. An earlier date than this for the rebuilding of the main wall is precluded by

the discovery of a coin of Aretas IV and

Shaqilath I (c. 9 B.C-A.D. 40) in a level immediately

underlying the construction level associated with that rebuilding.

|

| Petra - Temple of the Winged Lions |

possible |

≥ 7 |

Early 2nd century CE Earthquake - see Area I near the Temple of the Winged Lions. |

| Petra - Near Temple of the Winged Lions |

possible |

≥ 7 |

Early 2nd Century CE Earthquake

Erickson-Gini and Tuttle (2017)'s analysis

suggests that, although early 2nd century CE earthquake evidence is present in Petra and other sites of the Nabateans,

some of Russell (1985)'s

phasing was off by up to a couple of centuries. Some excerpts follow:

The conclusions to be presented here include a revision of the dating of the Early House in Area I and the ceramic assemblages

uncovered its antechamber and the upper and lower levels of the structure to the late 2nd and early 3rd c. CE when the structure

was abandoned. This revised dating is supported by evidence from other parts of the AEP excavations such as the Painters' Workshop

and important find spots near the temple that are presented in this paper as well as material from other parts of the

Provincia Arabia in the post-annexation period.

...

The use of a revised ceramic chronology in dating these assemblages will undoubtedly prove to be controversial,

however we believe that such a revision is long overdue and is in itself an important tool for the

re-examination of the phasing of structures and occupational layers in Petra and other sites in the Provincia Arabia,

the vast majority of which have been erroneously dated to the later 1st to early 2nd c. CE.

...

In 1977, Russell prepared a tentative phasing of the stratigraphy in Area I. The final phasing prepared by him in

1978 indicates the presence of twenty archaeological phases (Phases XX—I) and the remains of successive domestic

structures of the Early Roman (pre-annexation, i.e., the Roman annexation of Nabataea in 106 CE), Middle Roman (post-annexation)

and Byzantine periods. He designated these structures the "Early House", the "Middle House", and the "Late House".

...

The earliest archaeological material discovered in Area I, uncovered below the earliest architectural remains and in ancient falls, dates to

the Hellenistic period. The latest material belongs to an overlying cemetery that Russell dated to the Late Byzantine or Early Islamic periods.

...

As we shall see below, the abandonment of the Early House in Area I and abandoned hoards in rooms of the Temple of

the Winged Lions complex were probably the result of an epidemic that occurred sometime in the 3rd c.

rather than the early 2nd c. earthquake as claimed by Russell.

...

EVIDENCE OF AN EARTHQUAKE EVENT IN THE EARLY SECOND CENTURY CE

Russell's misreading of the archaeological evidence led him to attribute the end of the occupation of the Early House in

Phase XV to earthquake destruction that he dated to 113/114 CE based on the discovery of the single coin

found in the antechamber, a brass sestertius

commemorating Trajan's alimenta italiae endowment

dated to the period between 103 and 117 CE, together with the hoard of unguentaria and other ceramic vessels

(Russell, 1985:40-41).

Although the Early House was not destroyed and abandoned by an earthquake

in the early 2nd c., evidence of earthquake damage is discernible with the renovations that took place in its final

occupation in Phase XVI.

...

Subsequent research carried out in several sites

, including Petra itself, indicate that an early 2nd c. earthquake did indeed take

place (Erickson-Gini 2010:47)

65.

An examination of the records and photographs of the western side of the

Temple of the Winged Lions complex also reveals evidence of earthquake damage that precedes that of the

363 CE earthquake. This evidence includes the blockage of doorways with architectural fragments

that appear to have been derived from the temple, for instance in Area III.8 (SU 113; W2; Aug. 2, 1977),

that were also used in the construction of the pavement in WII.1W. Revetments adding support to walls were

photographed in Area III.7 (AEP 83900). In addition, a hoard of vessels of the late 1st c. BCE

and first half of the 1st c. CE was discovered in the AEP 2000 season in a spot next to the eastern corridor in

Area III.10 (SU 19). This assemblage of restorable vessels included several plain fineware, carinated bowls

that correspond to later forms of Schmid's Gruppe 5 dated to the second half of the 1st c. BCE (2000 AEP RI. 41), (2000: Abb. 41)

together with early forms of his Gruppe 6 dated to the 1st c. CE (2000 AEP RI. 11), (2000: Abb. 50)

and two early painted ware bowls (2000 AEP RI. 42) corresponding to Schmid's Dekorgruppe 2a

(2000: Abbs. 80=81) dated to the end of the 1st c. BCE and early 1st c. CE.

66

In spite of the presence of these early vessels, the AEP 2000 season finds registries records nearly all of

them as dating to 363 CE.

...

Russell was correct in dating the early form of the Early House

(Phase XVII) to the 1st c. ceramic vessels of that period

...

The Early House was obviously renovated, prior to its final form in Phase XVI, similar to other buildings

discovered in Petra. Some Nabataean communities, such as Mampsis and Oboda, underwent a wave of new

construction in the newly-organized Roman Province of Arabia while sites such as

'En Rahel and 'En Yotvata were destroyed and never re-built.

Renovations in wake of structural damage evident in structures in many sites

in the years following the annexation, as well as the construction of new buildings,

point to a widespread earthquake event in southern Transjordan and the Negev in the

early 2nd c. CE. The event may have influenced or even prompted the Roman

annexation that occurred soon afterwards. At Petra, the Early House was not destroyed at that time but rather

it was renovated and occupied until the early 3rd c. when it was abandoned,

possibly in the wake of an epidemic.

...

Conclusions

The primary issue concerning the Early House is the date and manner of its abandonment.

An outstanding difficulty in Russell's phasing in Area I is the two hundred year period between the

renovations that supposedly took place in the Early House in the early 2nd c. CE (Phase XVI)

and the construction of the Middle House in the early 4th c. CE (Phase XII).

This gap in the archaeological record is largely artificial and can be attributed to

the fact that a single coin was used to date the critical ceramic assemblage found in Room 2 (antechamber)

of the Early House (SU 176, 800, 803) to the very beginning of the 2nd c. Rather than its destruction by earthquake

in the early 2nd c., the body of evidence points to its abandonment sometime in the early

3rd c. similar to sites along the Petra—Gaza road.

|

| Petra - The Great Temple |

possible |

≥ 8 |

Phase VI Earthquake - Early 2nd century CE -

Joukowsky and Basile (2001:50), using a different phasing than

Joukowsky (2009), discussed archeoseismic evidence from the early 2nd century CE at the Great Temple.

Dated to the mid-second century, Nabataean-Roman Phase IV follows a minor collapse when the uppermost course of the

propylaea stairs was built to provide access to the

Lower Temenos, and when the Lower

Temenos east

cryptoportico,

which may have seen collapse, was filled in.

|

| Petra - Pool Complex |

possible |

≥ 8 |

Pre Phase III Earthquake - early 2nd century CE

Renovations during Phase III dated to the early 2nd century CE may have been a response to seismic damage most of which may have been cleared by renovations. The re-use of

building elements may be reflective of this response. It should be noted that these building elements could have come from another structure - for example the nearby Great Temple where

Joukowsky and Basile (2001:50) report an early 2nd century CE earthquake in Phase VI.

Bedal (2003:74) estimated an early 2nd century CE terminus post quem for the start of

Phase III

based on pottery found associated with various structures that were part of the renovations.

According to the refined pottery sequence from ez-Zantur, the type 3c Nabataean painted ware was produced in a brief span of

time, between ca.100 and 106/114 CE. Based on this pottery

evidence, it is possible to assign the floor bedding and by direct

association the bridge with a terminus post quem of the early 2nd

century CE.

...

However, a single rim sherd also found embedded in the floor mortar (Fig. 18)

may be more closely identified with a type 4 painted bowl from ez-Zantur,

dated post-106/114 CE (Schmid 1996:166, 208, abb. 704), in which case the Phase II

renovations in the Pool-Complex must be dated to a period following the annexation of Petra into the Roman Empire.

|

| Petra - ez Zantur |

possible |

≥ 7 |

Early 2nd century CE Earthquake - Debated Chronology

Kolb (2002:260) reported on excavations of a large residential structure (i.e. the mansion) in ez-Zantur in Petra. They dated the earliest phase of the structure

to the 20's CE based on fragments of Nabatean fine wares, dating to 20-70/90 CE, found in the mortar below the opus sectile flooring in rooms 1,10, and 17

as well as in the plaster bedding of the painted wall decorations in room 1 . Earthquake induced structural damage led to a

remodeling phase which was dated to the early decades of the 2nd century CE (Kolb, 2002:260-261).

A terminus post quem of 103-106 CE for the remodel was provided by a coin

struck under King Rabbel II found in some rough plaster (rendering coat) in Room 212 of site EZ III

(Kolb, 1998:263).

Erickson-Gini, T. and C. Tuttle (2017) propose re-dating the relevant ez-Zantur phasing to later dates.

A re-examination of the Zantur fineware chronology by the writer has revealed that it contains a number of serious

difficulties.25 The main difficulties in the Zantur chronology center on Phase 3,

which covers most of the 1st through 3rd c. CE. Zantur Phase 3 is divided into three sub-phases:

3a (20-80 CE), 3b (80-100 CE) and 3c (100-150 CE). The dating of Phase 3 is based on a very small amount of

datable material, for example, the main table showing the datable material (Schmid 2000: Abb. 420)

shows that no coins were available to date either Phase 3a or Phase 3c. Moreover, the earliest sub-phase, 3a,

was vastly underrepresented.26 At Zantur, there appears to be little justification for the beginning dates

for either Phase 3b (80 CE) or 3c (100 CE) or their terminal dates (100 CE and 150 CE respectively).

No `clean' loci, i.e., sealed contexts, were offered to prove the dating of Phases 3b and 3c and the

contexts are mixed with both earlier (3b) and later (3c) material (ibid., 184). This raises the question as to why a

terminal date of 100 CE was fixed for Sub-phase 3b. The coin evidence for Sub-phase 3b is scanty

and some of the coins could date as late as 106 CE while there is a discrepancy between the dates of the

coins and the imported wares, many of which date later than 100 or 106 CE. In order to date Phase 3 in

Zantur, there was a heavy dependence an a very small quantity of imported fineware sherds,

mainly ESA. Of the forms used, Hayes 56 is listed in both Phase 3b and 3c (ibid.) and since this

particular form dates later than 150 CE (Hayes 1985: 39) the majority of the forms and motifs of both

sub-phases 3b and 3c should be assigned to the later 2nd and early 3rd centuries.

with its purported range of 60 years.

Footnotes

25 "Problems and Solutions in the Dating of Nabataean Pottery of the Roman Period," presented on February 20, 2014 in the

2nd Roundtable "Roman Pottery in the Near East" in Amman, Jordan on the premises of the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR).

26 In the words of the report: "Unfortunately, so far only a few homogeneous FKs (find spots/loci) have been registered with

fineware exclusively from Phase 3a. After all, if the Western Terra Sigillata form, Conspectus 20, 4 from FK 1122

(Abb. 420, 421 Nr. 43) accurately reflects the duration of Phase 3a, we can thus estimate [the period] as from 20 to 70/80 CE"

(Schmid 2000: 38).

Grawehr M. (2007:399) described a destruction layer at a bronze workshop at ez-Zantur

Room 33 is the work-shop proper. This is indicated by the finds that were encountered in a thick and seemingly undisturbed

destruction layer, sealed by the debris of the rooms arched roof. While any indication for the cause of this destruction

evades us, the dating of the event is clear. Through the evidence of the coins an the floor we arrive at a terminus post

quem of 98 AD. As there is plenty of fine ware in the destruction level, belonging to Schmid's phase 3b, but none of

phase 3c, which according to him starts ±100 AD, the destruction must have taken place at the end of the first

or early in the second century AD.

Kolb B. and Keller D. (2002:286) also discussed archeoseismic evidence at ez-Zantur

Stratigraphic excavation in square 86/AN unexpectedly brought useful data on the history of the mansion' s construction phases

and destruction. The ash deposit in Abs. 2 with FK 3524 and 3533 provided clear indications as to the final destruction in 363.

A further chronological "bar line" — a some-what vaguely defined construction phase 2 in various parts of the terrace in the

late first or second century AD — received clear confirmation in the form of a thin layer of ash.

The lamp and glass finds from the associated FK 3546 date homogeneously from the second century AD,

and confirm the assumption of a moderately severe (not historically documented) earthquake that led to the structural

repairs observed in various places and the renewal of a number of interior decorations.

|

| Petra - Wadi Sabra Theater |

|

|

Phase 3 earthquake - 2nd - 3rd century CE -

Tholbecq et al (2019) report that various clues suggest that the theater underwent violent destruction during this phase. This happened

no later than the 3rd century CE . |

| Avdat/Oboda |

possible |

|

Early 2nd century earthquake

Erickson-Gini, T. (2014) described the early 2nd century earthquake as follows:

There is indirect evidence of a more substantial destruction in the early 2nd century CE in which residential structures from the earliest

phase of the Nabataean settlement east of the late Roman residential quarter were demolished and used as a source of

building stone for later structures. Destruction from this earthquake is well attested particularly

nearby at Horvat Hazaza, and along the Petra to Gaza road at Mezad Mahmal, Sha'ar Ramon, Mezad Neqarot and Moyat `Awad, and at `En Rahel

in the Arava as well as at Mampsis (Korjenkov and Erickson-Gini 2003).

Erickson-Gini and Israel (2013) added

Evidence of an early second-century CE earthquake is found at other sites along the Incense Road at Nahal Neqarot, Sha'ar Ramon,

and particularly at the head of the Mahmal Pass where an Early Roman Nabataean structure collapsed

(Korjenkov and Erickson-Gini 2003; Erickson-Gini 2011). There is ample evidence of the immediate reconstruction of

buildings at Moyat ‘Awad, Sha'ar Ramon, and Horvat Dafit. However, this does not seem to be the case with the Mahmal and Neqarot sites.

Erickson-Gini and Israel (2013) discussed seismic damage at

Moyat ‘Awad due to this earthquake

The Early Roman phase of occupation in the site ended with extensive damage caused by an earthquake that took place

shortly before the Roman annexation of the region in 106 CE (Korjenkov and Erickson-Gini 2003). The building in Area

C and the kiln works were destroyed, and the cave dwellings were apparently abandoned as well.

Reconstruction was required in parts of the fort. At this time, deposition from its floors was removed and

thrown outside of the fort and a new bath as well as heating were constructed in its interior.

Along its eastern exterior and lower slope, rooms were added. Thus, the great majority of the finds from

inside the fort and its ancillary rooms date to the latest phase of its occupation in the Late Roman,

post-annexation phase, the latest coins of which date to the reign of Elagabalus (219–222 CE).

|

| Mampsis |

possible |

|

Deciphering chronology at Mampsis has unfortunately been problematic.

Before the First Earthquake - Early 2nd century CE earthquake

Russell (1985)

cited Negev (1971:166) for evidence of early second century earthquake destruction at Mamphis.

Negev (1971) reports extensive building activity in Mamphis in the early second century AD

obliterating much of the earlier and smaller infrastructure. However, neither a destruction layer nor an earthquake is mentioned.

Citing

Erickson-Gini (1999) and

Erickson-Gini (2001),

Korzhenkov and Erickson-Gini (2003) cast doubt on Russell (1985)'s

assertion of archeoseismic damage at Mamphis stating that recent research indicates a continuation of occupation throughout the 1st and 2nd cent. A.D..

Continuous occupation could indicate that seismic damage was limited rather than absent.

|

| Moje Awad |

possible |

≥ 8 |

End of Early Roman Phase earthquake - early 2nd century CE - Erickson-Gini and Israel (2013) discussed the early

2nd century earthquake at Moje Awad as follows:

The Early Roman phase of occupation in the site ended with extensive damage caused by an earthquake that took place shortly before

the Roman annexation of the region in 106 CE

(

Korzhenkov and Erickson-Gini, 2003). The building in Area C and the kiln works

were destroyed, and the cave dwellings were apparently abandoned as well. Reconstruction was required in parts of the fort.

At this time, deposition from its floors was removed and thrown outside of the fort and a new bath as well as heating were

constructed in its interior. Along its eastern exterior and lower slope, rooms were added.

No photos of destruction were supplied and it is unclear if earthquake destruction was inferred from rebuilding evidence or

if actual damaged structures were observed. Likewise, it is not clear how

Erickson-Gini and Israel (2013)

dated this earthquake to shortly before Roman annexation in 106 CE. If the pre 106 CE date is based on rebuilding

evidence, it would seem that the earthquake is dated no more precisely than early second century CE. |

| Sha'ar Ramon |

possible |

|

Erickson-Gini and Israel (2013:41-42)

report that evidence was found for an early 2nd century CE earthquake at Sha'ar Ramon perhaps based on rebuilding evidence as

they state that there is ample evidence of the immediate reconstruction of buildings at Moyat Awad, Sha'ar Ramon, and Horvat Dafit. |

| Neqarot Fort |

possible |

≥ 8 |

Erickson-Gini (2012) claims that Nahal Neqarot contains

early 2nd century CE earthquake destruction evidence.

Erickson-Gini and Israel (2013) allude to collapsed structures at Nahal Neqarot that were left unrepaired. Supporting evidence was not presented.

Supporting evidence may be in Erickson-Gini (2010) |

| Ein Rahel |

probable |

≥ 8 |

Early 2nd Century CE Earthquake

Korzhenkov and Erickson-Gini (2003) describe archeoseismic evidence for an early second century CE earthquake as follows:

In the surrounding casemate rooms the latest occupational

phase (dating to the early 2nd cent. A.D.) was sealed by the collapse of

the upper floor of the fort. Sections excavated in these rooms revealed clear

collapse of the ceiling of the lower floor and the upper floor debris sealed by

the upper floor roof. The ceiling and roof of the structure were made from

woven organic matting and mud and were supported by wooden beams.

A rich ceramic assemblage was discovered in the fort as well as extensive organic finds

and included reed-matting and wooden beams, almond shells, nuts and olive and dates stones.

Several wooden lice combs and other wooden objects were found in excellent condition,

as well as many shreds of textiles and leather. Two camel bones were found bearing

inscriptions in black ink in the Nabataean script.

Shamir (1999)

examined the textiles, basketry and cordage and reported that

Preserved by the arid climate, the perishables from `En Rahel include about 300 textile and basketry fragments,

cordage, spindle whorls and needles. The Early Roman date of the material, provided by its archaeological context,

differs slightly from its radiocarbon dating [1]

(Carmi and Segal 1995:55).

[1] In the fall of 1991, a brown goat-hair textile fragment from L13, Basket 129 was submitted to

I. Carmi and D. Segal at the 14C laboratory of the Weizmann Institute of Science, in order to

verify the archaeological conclusions. Their results suggest the fabric was manufactured in the Roman period:

| Sample |

d14C |

d13C |

yrs BP* |

Calendaric Age** |

| RT-1596 |

-209.2 ± 3.9 |

-15.95 |

1885 ± 40 |

82-204 CE |

* Conventional radiocarbon years before 1950.

** Calculated using CALIB 3 (Stuiver and Reimer 1993).

Note by Jefferson Williams : The calendaric age reported in Carmi and Segal 1995:55

is a bit different (and earlier)

| Sample |

d14C |

d13C |

yrs BP* |

Calendaric Age** |

| RT-1596 |

-209.2 ± 3.9 |

-15.95 |

1885 ± 40 |

66-145 CE (87%), 165-186 CE (13%) |

* Conventional radiocarbon years before 1950.

** Calculated using CALIB 3 (Stuiver and Reimer 1993).

Korzhenkov and Erickson-Gini (2003) estimated Intensity of 8-9, epicenter in vicinity of the site in WNW or ESE (~125 degrees)

direction. The proximity of the Arava Fault led them to consider ESE more likely

|

| Mezad Mahmal |

possible |

≥ 8 |

Early 2nd century CE earthquake

Erickson-Gini (2011) excavated 6 meters west of the fort and found remains

which appear to belong to an Early Roman Nabataean caravan station destroyed in the early second century CE by an earthquake. They described what they

found as follows:

Pottery found in the excavation of the building shows that it was founded in the mid-first century CE and continued

to be used until sometime in the early second century CE, when it was evidently destroyed in an earthquake (Fig. 7

). Wall 1 appears to have collapsed northward (Fig. 8

) and the remains of a cooking pot (Fig. 10:8) in L601,

next to the tabun (F-1), had broke and was partially spread eastward next to the interior of W1. Tabun F-1

contained small rocks and a number of potsherds, including an early type of a Gaza wine jar (Fig. 10:11)

that is dated to the first–third centuries CE. Other diagnostic potsherds included parts of Nabataean painted

ware bowls (Fig. 9:1–8), an Eastern Sigilatta ware bowl (Fig. 10:1), undecorated cups and bowls (Fig. 10:2–5, 7),

Nabataean rouletted ware (Fig. 10:6), Nabataean cooking pot (Fig. 10:9), Roman carinated cooking pot (Fig. 10:10),

jars (Fig. 10:12, 13), Nabataean strainer jugs (Fig. 10:14, 15) and a fragment of a Roman lamp with a decorated

discus (Fig. 10:16).

Visual investigation of the area north of the early structure shows traces of possible wall lines and

other rooms. However, no plan of this structure can be determined without carrying out further excavations.

It may be assumed, on the basis of the 2004 excavation, that rooms were situated around an open courtyard.

The structure was badly damaged by an earthquake and appears to have been stripped of masonry stones nearly

to its foundation.

...

In addition to excavations in the early building, the exterior sides of the Roman fort along the eastern,

northern and part of the western side, were excavated to facilitate restoration work on the structure

(L101/L102, L103, L201 and L801). A deep probe along the northeastern corner of the structure (L103)

was excavated down to bedrock. In the foundation trench near bedrock a diagnostic fragment of a Late

Roman-Nabataean debased painted ware bowl (Fig. 9:9) was found. The structure showed signs of

earthquake damage along its northern wall (L201) and the center of this wall had collapsed northward.

A section of collapse at this point of the wall was preserved and left unexcavated.

The current excavation confirmed the discovery that the Mezad Mahmal fort is a Roman and not a Nabataean fort,

as has generally been assumed. The fort was constructed in the later half of the second century CE in the

Late Roman period. It appears to belong to a Roman military initiative of constructing tower forts in the

Severan period elsewhere along the Petra–Gaza road, such as the fort of Horbat Qazra and Mezad Neqarot.

Other forts of this type and period are known at Horbat Haluqim (‘Atiqot 11 [ES]:34–50) and Horbat Dafit (ESI 3:16–17).

The primary discovery in this season was the remains of the Nabataean caravan station of the first century CE,

situated at the head of the pass. This structure, which apparently contained a number of rooms located around a

central courtyard, was destroyed in a seismic event in the early second century CE and subsequently, was probably abandoned.

|

| 'En Ziq |

possible |

|

Erickson-Gini (2012)

reports that at the site of ’En Ziq in the Nahal Zin basin near

Sde Boker, the same early 2nd century earthquake which destroyed the Nabatean Fort at Ein Rahel

also destroyed the Nabatean Hellenistic fortress at 'En Ziq. |

| Horbat Hazaza |

possible |

≥ 6-8 |

Erickson-Gini (2019:152,167) reports destruction of the South Wing and subsequent abandonment along with three

fallen arches in Room 2. A 1st century CE terminus post quem was established for the fallen arches based on Nabatean pottery and a terminus ante quem

seems to have been established due to continued occupation of the north wing where pottery as early as the first half of the 2nd century CE was found

(Hayes’ Form P40 fine-ware krater -

Erickson-Gini, 2019:162). |

| Yotvata |

possible |

≥ 8 |

Early 2nd century CE Earthquake

Erickson-Gini (2012a) report archaeoseismic evidence in a Nabatean structure

at 'En Yotvata

Three walls of a structure (W1–W3; Fig. 4) were revealed during the 2005 season.

The walls were constructed from hard limestone blocks (average size 0.25×0.35 m).

The only complete wall was W2 in the west, oriented north–south (length 12.5 m),

which was preserved to at least two courses high above the surface.

A possible entrance is indicated along this wall, slightly west of its center.

The other two walls appear to have been of the same length.

The structure had entirely collapsed in the earthquake of the early second century CE.

...

The structure, which was apparently a two-story building, appears to have been stripped for

building stones, probably after the earthquake destruction.

In the collapse of the upper storey (L100, L500, L600), potsherds dating to

Late Hellenistic period were discovered, including painted fine-ware bowls

(Fig. 5:1, 3, 4), a bowl of the fish-plate tradition (Fig. 5:9),

as well as painted fine-ware bowls of the Early Roman period (Fig. 5:5–7).

Large fragments of a fine-ware painted bowl of the second half of the first century CE were discovered,

in situ, in the middle of the building (L100; Fig. 5:8).

...

A group of collapsed stone ceiling slabs (F2), standing nearly upright, was uncovered in the middle of the L601 square (Fig. 8 )

...

The building was apparently destroyed in an earthquake in the early second century CE.

Evidence of this disaster could be seen in the collapsed upper floor in both squares,

the collapsed ceiling slabs and in the collapse of the structure’s exterior walls.

In addition, parts of the same Nabataean Aqaba Ware jar, found in the last season,

were discovered deep in L502, somewhere above the surface of the lower floor.

The coins recovered from the debris of the upper floor are Nabataean coins of the first century CE.

The pottery assemblage includes forms of the earliest Nabataean painted wares of the Late Hellenistic period,

Nabataean painted ware bowls of the Early Roman period, and plain ware Nabataean vessels, spanning the Late

Hellenistic and Early Roman periods. The latest datable pottery vessels discovered in the

structure are the Nabataean Aqaba Ware jars, dated to the early second century CE.

|

| Rujm Taba |

possible |

|

Surface Survey only. Site not excavated.

Early 2nd century CE Earthquake

Dolinka (2006a) reports the possibility of archaeoseismic evidence at Rujm Taba based on site

delineation and surface collection performed in August 2001

and previous work such as SAAS.

the ceramic evidence gathered by RTAP

suggests that both the village and the caravanserai at

Rujm Taba flourished during the late first century AD,

aptly demonstrated by the fact that half of the NPFW

from the village and nearly half (48%) of the NPFW

from Structure A001 are dated to Dekorphase 3b, or c.

70–100 AD. A high amount of activity at Rujm Taba

during this period seems to call into question the

notion repeated by many scholars (e.g. Bowersock

1983: 156) that the discovery of the monsoon winds in

the mid-first century AD caused a major decline in the

Nabataean overland caravan trade. Quite contrary,

Rujm Taba seems to have thrived in an era of supposed

economic deterioration.

Third, according to the RTAP ceramic repertoire there

seems to have been a decline in activity and occupation

at Rujm Taba during the early to mid-second century

AD, an idea supported by the fact that numbers of

NPFW drop off sharply during this period, with only

8% of the total pottery from Structure A001 and 15% of

the total ceramics from the village dating from Zantur

Dekorphase 3c. Whether or not this decline should be

attributed to the Roman annexation of Nabataea in AD

106, or an earthquake that devastated the Rift Valley

during the early second century AD, is still a matter of

debate among scholars that could easily be resolved

through stratified excavations at Nabataean sites, such

as Rujm Taba, located along the major trade routes that

were in use during the period in question.

|

| Horbat Dafit |

possible |

≥ 8 |

End of Phase 1 Earthquake - early 2nd century CE - Dolinka (2006:130) reports that Phase 1

ended with the earthquake of the early-2nd century AD, and several of the rooms within the structure exhibited

collapse of the architectural elements as well as ashy layers associated with that event.

Dolinka (2006:135-136) further reports that

the earliest levels of [phase 2] are characterized by mudbrick collapse and/or building debris (e.g. Locus 46),

cleaning of the interior of some of the rooms (e.g. Loci 23. 26 and 50), repair to damaged walls (e.g. Locus 45),

and reconstruction of the main entrance and gate (Locus 27). The site appears to be well dated except for in some loci.

Dolinka (2006:155) noted a

difficulty in discerning the division between Phases 1 and 2 in some loci which, it was suggested,

was due to activities associated with the reconstruction of the gate after the earthquake, which likely disturbed

the floor levels from those loci. |

| Other sites in the Negev |

needs investigation |

n/a |

n/a |