Petra - Wadi Sabra Theater

The theatre of Wâdî Sabrah in 1828, as published by L. de Laborde (1830: pl. 34)

Tholbecq et. al. (2016)

Right - Figure 49

View of the theater from the north:

- below, the orchestra overgrown with vegetation

- on the right, the stone bleachers preserved in situ

- on the left, the wall of the large cistern behind the theatre

- up, the cliff of the massif that borders Wadi Sabra and the natural fault from which the water comes in case of rain

Tholbecq et al (2019)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Wadi Sabra | Arabic | وادي سابرا |

- from Chat GPT 5.2, 14 January 2026

The theater was carved directly into the limestone at the mouth of a small tributary wadi and takes advantage of the natural slope of the valley. Its modest scale, rock-cut cavea, and close spatial relationship with the sanctuary distinguish it from Petra’s urban theater and place it within a broader Near Eastern tradition of theaters integrated into peri-urban and cultic landscapes rather than dense city centres.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the theater was constructed during the Roman period, probably in the 2nd century CE, and underwent significant modification and functional reorganisation during the 3rd century CE, including alterations to the orchestra and circulation systems.

The Sabra site is approximately 6.5 km as the crow flies southwest of central Petra. Its ruins extend over around twenty hectares (ca. 600 x 300 m), on either side of the Wadi Sabra, a narrow valley linking the southern suburbs of Petra to the Wadi Arabah and which, therefore, constitutes the one of the major accesses to the Nabataean capital. The site has several complexes built in masonry and rock installations, in particular a theater associated with hydraulic installations built at the foot of Jabal al-Jathum. It was rediscovered in 1828 by Louis Maurice Adolphe Linant de Bellefonds (1798-1883) and by Léon de Laborde (1807-1869), returning from a visit to Petra. Several travelers reported it at the end of the 19th century and during the 20th century but it was not until the 1970s and the initiative of Manfred Lindner that archaeological exploration began, under the auspices of the Naturhistorische Gesellschaft Nürnberg (NHG).

- from Petra - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 23 - Location Map

from Tholbecq et al (2018)

Fig. 23

Fig. 23

Satellite view of Petra with location of spa buildings.

Baths associated with a house in green

baths associated with a religious complex in red

(MAFP / Ifpo - Th. Fournet 2018, with a Google Basemap).

Tholbecq et al (2018) - Fig. 1 - Location Map

from Fournet & Tholbecq (2015)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Sabra site plan published by Léon de Laborde with locations of the sanctuary and baths

(LABORDE 1830, pl. 33)

Fournet & Tholbecq (2015)

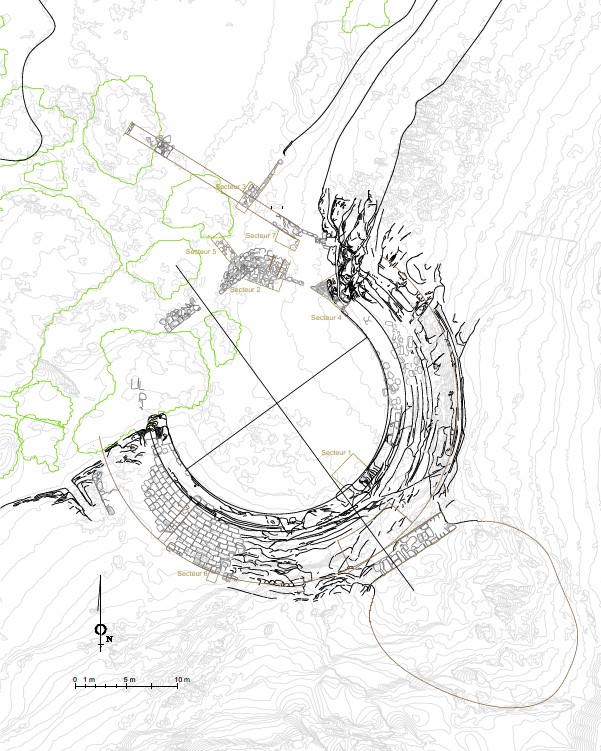

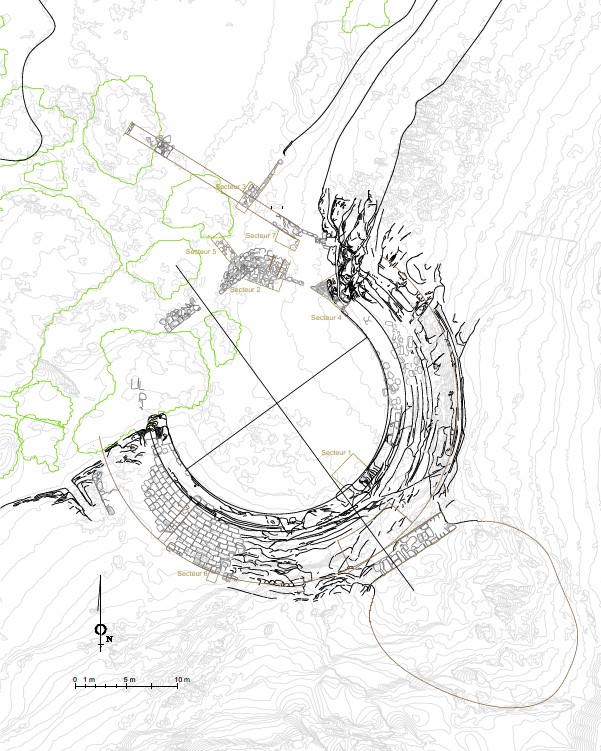

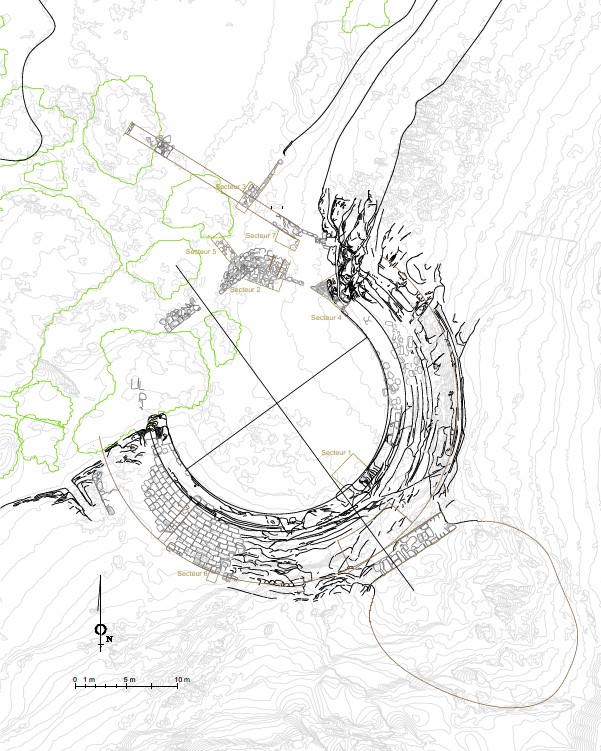

- Fig. 7 - General Plan from

Tholbecq et al (2019)

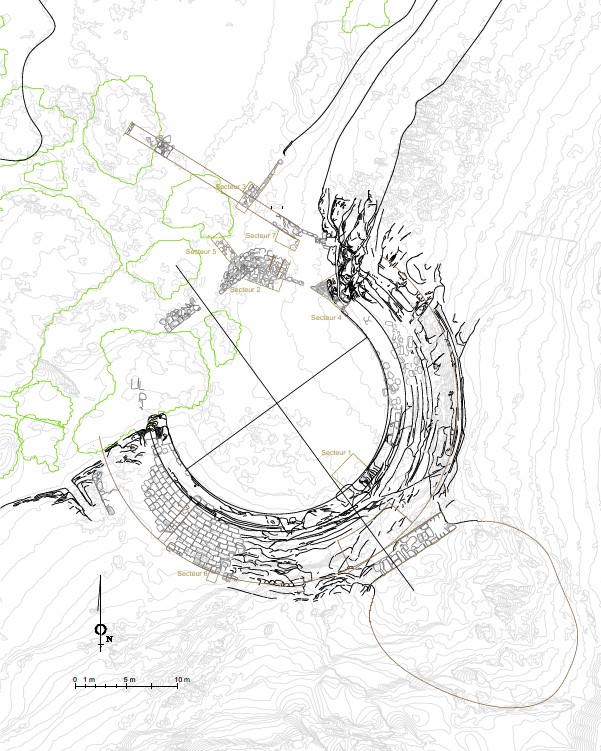

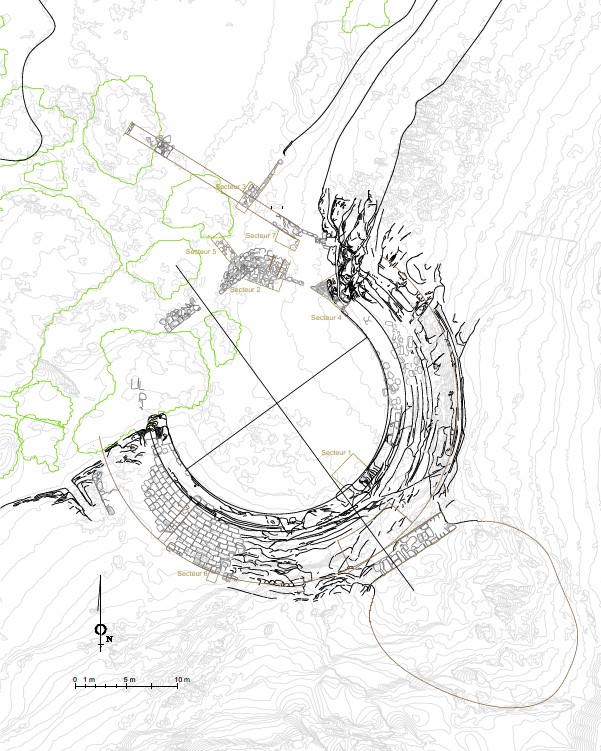

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

General plan of the theater, based on a photogrammetric survey, with location of soundings (M. Kurdy).

Tholbecq et al (2019) - Fig. 14 - Plan of theater

from Tholbecq et. al. (2016)

Fig. 14

Fig. 14

Wadì Sabrah : a partial top plan of the theatre and associated remains, 2014

(G. Dumont, N. Paridaens, S. Delcros).

Tholbecq et. al. (2016) - Fig. 3 - Plan of theater

and the caravanserai/fortress from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

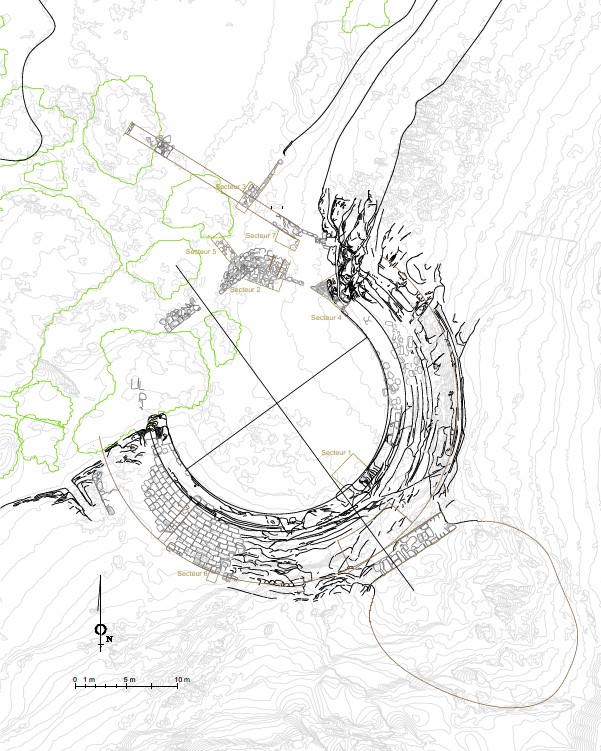

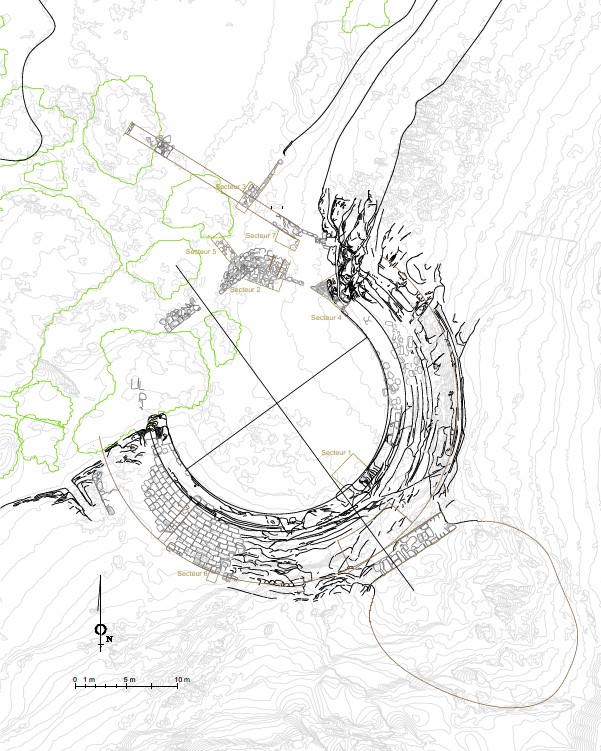

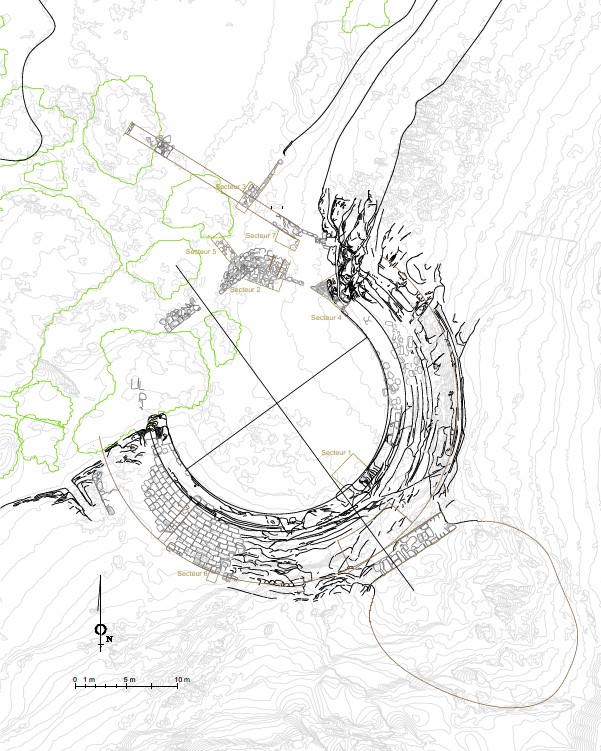

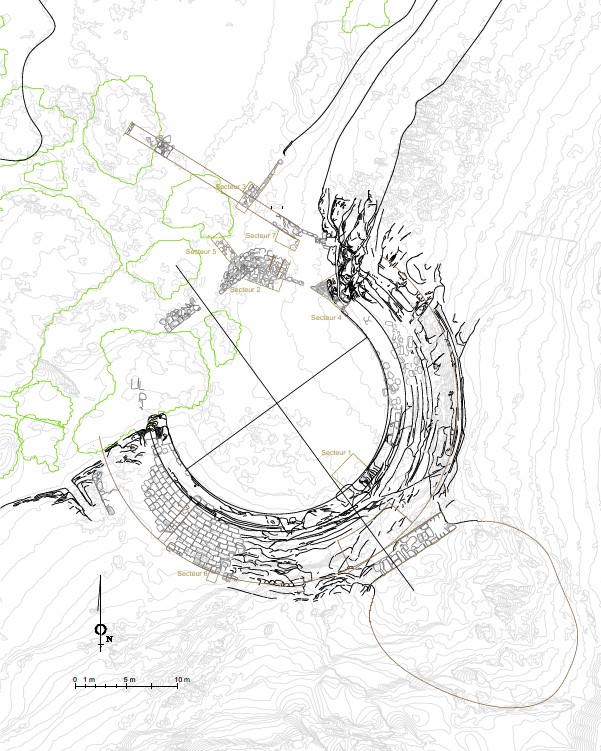

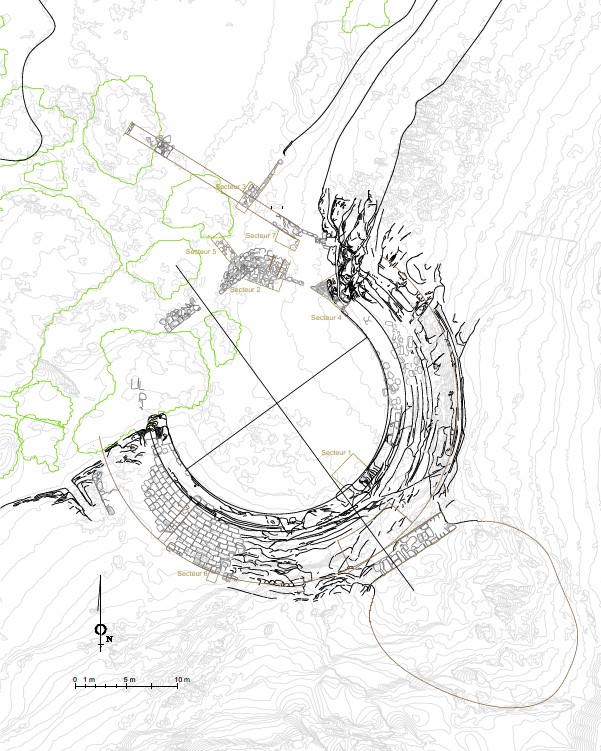

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Plan of the theater and the caravanserai/fortress with the location of the sectors excavated in

- 2018 (in yellow)

- 2021 (in blue)

- 2022 (in red)

(recorded by N. Paridaens, L. Tholbecq, B. Van Nieuwenhove, P. Thiolas; background plan S. Delcros, W. Abu Azizeh, P. Rieth, L. Vallières; DAO N. Bloch, M. Kurdy & N. Paridaens).

Tholbecq et al. (2022)

- Fig. 7 - General Plan from

Tholbecq et al (2019)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

General plan of the theater, based on a photogrammetric survey, with location of soundings (M. Kurdy).

Tholbecq et al (2019) - Fig. 14 - Plan of theater

from Tholbecq et. al. (2016)

Fig. 14

Fig. 14

Wadì Sabrah : a partial top plan of the theatre and associated remains, 2014

(G. Dumont, N. Paridaens, S. Delcros).

Tholbecq et. al. (2016) - Fig. 3 - Plan of theater

and the caravanserai/fortress from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Plan of the theater and the caravanserai/fortress with the location of the sectors excavated in

- 2018 (in yellow)

- 2021 (in blue)

- 2022 (in red)

(recorded by N. Paridaens, L. Tholbecq, B. Van Nieuwenhove, P. Thiolas; background plan S. Delcros, W. Abu Azizeh, P. Rieth, L. Vallières; DAO N. Bloch, M. Kurdy & N. Paridaens).

Tholbecq et al. (2022)

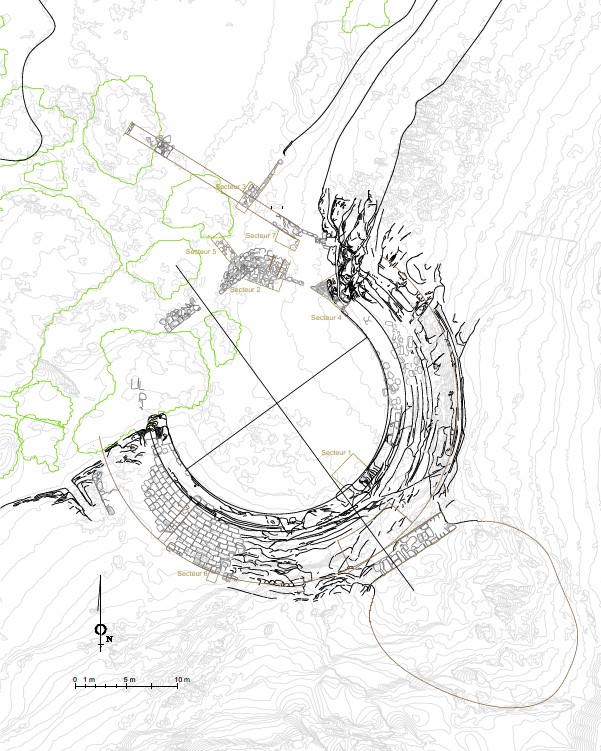

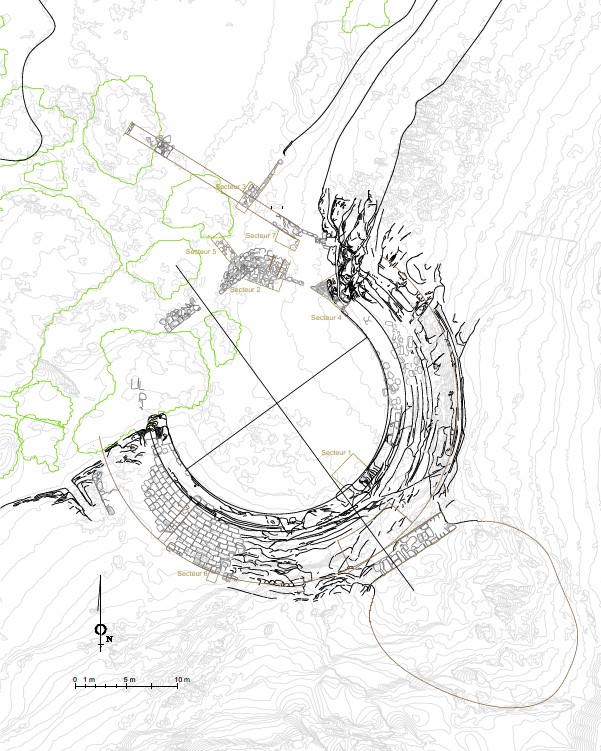

- Fig. 3 - Plan of theater

and the caravanserai/fortress from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Plan of the theater and the caravanserai/fortress with the location of the sectors excavated in

- 2018 (in yellow)

- 2021 (in blue)

- 2022 (in red)

(recorded by N. Paridaens, L. Tholbecq, B. Van Nieuwenhove, P. Thiolas; background plan S. Delcros, W. Abu Azizeh, P. Rieth, L. Vallières; DAO N. Bloch, M. Kurdy & N. Paridaens).

Tholbecq et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 - Plan of the

caravanserai/fortress from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

General plan of the caravanserai/fort with the location of the sectors excavated in 2021 and 2022

(surveys N. Paridaens, B. Van Nieuwenhove; DAO N. Paridaens).

Tholbecq et al. (2022) - Fig. 7 - Plan of the

SE part of the caravanserai/fortress from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Map of the sectors excavated in 2021 and 2022 with the location of the principal (rooms ?, sectors ?)

(surveys and DAO N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al. (2022)

- Fig. 3 - Plan of theater

and the caravanserai/fortress from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Plan of the theater and the caravanserai/fortress with the location of the sectors excavated in

- 2018 (in yellow)

- 2021 (in blue)

- 2022 (in red)

(recorded by N. Paridaens, L. Tholbecq, B. Van Nieuwenhove, P. Thiolas; background plan S. Delcros, W. Abu Azizeh, P. Rieth, L. Vallières; DAO N. Bloch, M. Kurdy & N. Paridaens).

Tholbecq et al. (2022) - Fig. 6 - Plan of the

caravanserai/fortress from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

General plan of the caravanserai/fort with the location of the sectors excavated in 2021 and 2022

(surveys N. Paridaens, B. Van Nieuwenhove; DAO N. Paridaens).

Tholbecq et al. (2022) - Fig. 7 - Plan of the

SE part of the caravanserai/fortress from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Map of the sectors excavated in 2021 and 2022 with the location of the principal (rooms ?, sectors ?)

(surveys and DAO N. Paridaens)

Tholbecq et al. (2022)

- Fig. 24 - Plan of Acropolis,

Sanctuary, and Baths in Wadi Sabra from Tholbecq (2016)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

Plan of surveyed areas and archaeological remains within the site of Wadi Sabra.

Tholbecq (2016)

- Fig. 24 - Plan of Acropolis,

Sanctuary, and Baths in Wadi Sabra from Tholbecq (2016)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

Plan of surveyed areas and archaeological remains within the site of Wadi Sabra.

Tholbecq (2016)

- Fig. 13 - Drawing of Wadi Sabra

Theater from 1828 from Tholbecq et. al. (2016)

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

The theatre of Wâdî Sabrah in 1828, as published by L. de Laborde (1830: pl. 34)

Tholbecq et. al. (2016)

- from Tholbecq et al (2019)

- There appears to be evidence for two earthquake destructions

| Phase | Phase Label | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Digging and development of the cavea | no later than the 2nd century CE |

|

| 2 | Closure of the theatrical space and monumentalization of the facade | 2nd century CE |

|

| 3 | Partial destruction and reassignment | 2nd-3rd century CE |

|

| 4 | Construction of a barrier wall to the south of the theater and new secondary facilities. | Late Roman or Byzantine |

|

- from from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

- Phasing is a bit messy - gleaned from various sections in the report where chronology is not always explicitly tied to a phase

| Phase | Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2nd century CE - |

|

| Burning Event | 2nd half of the 2nd century CE - beginning of the 3rd century CE |

|

| 2 |

|

|

| Burning Event | middle of the 3rd and the 4th century CE |

|

| 3 |

|

|

| Falling Event |

|

A second, later phase of abandonment is perceptible on the grounds of the caravanserai. Already observed during the 2022 campaign, it is attributable to the end of the 4th century, probably following the earthquake of 363 (with consistent radiocarbon dates), corroborating the idea of a general abandonment of the Sabra wadi in this chronological horizon.

The site of Sabra extends over ca. 20 ha in a narrow valley 6.5 km south of Petra. It includes a major Nabataean-Roman sanctuary, a rock-cut theater, and a small settlement. In 2022, a team representing Université libre of Brussels (ULB, Belgium) carried out a second excavation season on a ca. 23 by 14.5 m structure lying in the bed of the Wadi Sabra, ca. 45 m west of the theater (Fig. 1). The objective was to determine the nature of the building and to compare its chronology with the phasing of the theater defined during previous excavation seasons (Tholbecq et al. 2020).

Three major conclusions can be drawn. First, the newly excavated building is constructed on top of massive late 1st/early 2nd -century AD dumps connected to banquets (table vessels), although there is no way to establish if these dumps are in situ or were brought there through terracing activities linked with the initial phase of the building. Nevertheless, they provide a terminus for the construction of the building, likely contemporary to the post-annexation development of the sanctuary and its associated bath complex (Fournet and Tholbecq 2015). Secondly, a rectangular sandstone structure, probably supplied with water from a nearby aqueduct, was built on flintstone foundations. This early building was severely destroyed by heavy flooding and its destruction seals archaeological finds securely dated to the first half of the 3rd century AD. Its function remains unknown, but one may tentatively suggest a caravanserai, mansio, or hospitalia connected to the sanctuary. Third, its ruins were then refurbished, using specific yellow limestone blocks bonded with lime mortar; several small rooms were distributed around a central paved courtyard, and the building was equipped with small latrines. Since there is possible evidence of a military installation in other parts of the site (e.g., fortification of the “acropolis,” construction of a corner tower topping the site, and Late Roman melting activities), we believe that the 2nd - century AD building, ruined around the mid-3rd century, was reallocated to military purposes and transformed into a small fort in the mid- or second half of the 3rd century. The fort was finally destroyed by fire in the mid-4th century, probably following the earthquake of 363, a date confirmed by several converging 14C analyses. In other words, the occupation sequence of this building echoes the phasing of the 2nd -century AD theater, with a rapid abandonment of its original function, followed by the closure of its orchestra, likely connected to the presence of a small local garrison in the last century of its existence.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description/Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recycled Building Elements suggests Collapsed Walls |

Blockade Walls (aka analemmata) ?

Fig. 7

Fig. 7General plan of the theater, based on a photogrammetric survey, with location of soundings (M. Kurdy). Tholbecq et al (2019) |

the upper parts of the walls seem to have been destroyed, then rebuilt by recycling collapsed bleacher seats- Tholbecq et al (2019) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description/Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Masonry Blocks ? | Northern masonry of the orchestra - Soundings 2 and 7

Fig. 7

Fig. 7General plan of the theater, based on a photogrammetric survey, with location of soundings (M. Kurdy). Tholbecq et al (2019) |

destruction of the northern masonry of the orchestra- Tholbecq et al (2019) |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description/Comments | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycled Building Elements suggests Collapsed Walls |

Blockade Walls (aka analemmata) ?

Fig. 7

Fig. 7General plan of the theater, based on a photogrammetric survey, with location of soundings (M. Kurdy). Tholbecq et al (2019) |

the upper parts of the walls seem to have been destroyed, then rebuilt by recycling collapsed bleacher seats- Tholbecq et al (2019) |

VIII+ |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description/Comments | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Masonry Blocks ? | Northern masonry of the orchestra - Soundings 2 and 7

Fig. 7

Fig. 7General plan of the theater, based on a photogrammetric survey, with location of soundings (M. Kurdy). Tholbecq et al (2019) |

destruction of the northern masonry of the orchestra- Tholbecq et al (2019) |

VIII+ |

Fournet, T., & Tholbecq, L. (2015). LES BAINS DE SABRĀ: UN NOUVEL ÉDIFICE THERMAL AUX PORTES DE PÉTRA.

Syria, 92, 33–44. - JSTOR

Lindner, M. (1982) “An Archaeological Survey of the Theater Mount and Catchwater Regulation System at Sabra, South of Petra, 1980

”, ADAJ 26, p. 231-242.

Lindner, M. (2005) “Water Supply and Water Management at Ancient Sabra (Jordan)”, PEQ 137.1,

p. 33-52.

Lindner, M. (2006a) "Theater, Theater, Theater ... Zu Forschungen der Naturhistorischen

Gesellschaft in Sabra", Natur und Mensch. Jahresmitteilungen der Naturhistorischen Gesellschaft

Nürnberg, 2006, p. 75-84.

Tholbecq, L. (2016) « Petra. Wadi Sabra Archaeological Project » in G.J. Corbett, D.R.

Keller, B.A. Porter & Ch. P. Shelton (Ed.), « Archaeology in Jordan, 2014 and 2015 Seasons »,

American Journal of Archaeology 120.4, 2016, p. 666-668, fig. 24.

Tholbecq, L., (2016) “Petra. Wadi Sabra Archaeological Project ”, GJ Corbett et al. (Ed.), “Archaeology

in Jordan, 2014 - 2015 ”, AJA 120.4, p. 666-668.

Tholbecq, L., Fournet, T., Paridaens, N., Delcros, S., & Durand, C. (2016). Ṣabrah, a satellite hamlet of Petra.

Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 46, 277–297.

Tholbecq, L., (2022). Théâtres associés à des espaces cultuels au Proche-Orient romain : à propos de quelques travaux récents

Annales du Centre scientifique de l’Académie polonaise des Sciences à Paris, 23, 2022, p. 274-278.

Tholbecq, L. et al. (2024) Petra: Khirbat Sabra

In. Pearce Paul Creasman, Jack Green and China P. Shelton (Eds.), Archaeology in Jordan 4, 2022-2023 Seasons, p. 136-137

L. Tholbecq, T. Fournet, N. Paridaens, S. Delcros, G. Dumont & C. Durand (2015) “The

Nabateo-Roman site of Wadi Sabra: inventory, survey and working hypotheses”, L.

Tholbecq (Ed. ), French archaeological mission of Pétra: Report of the archaeological campaigns 2014

- 2015, Brussels, p. 63-100.

Tholbecq, L., et al. (2019). Mission archéologique française à Pétra. Rapport des campagnes archéologiques 2018-2019.

Tholbecq, L., et al. (2021). Mission archéologique française à Pétra. Rapport des campagnes archéologiques 2021.

Tholbecq, L., et al. (2022). Mission archéologique française à Pétra. Rapport des campagnes archéologiques 2022.

Tholbecq, L., et al. (2023). Mission archéologique française à Pétra. Rapport des campagnes archéologiques 2023.

- from Wikipedia