Heshbon

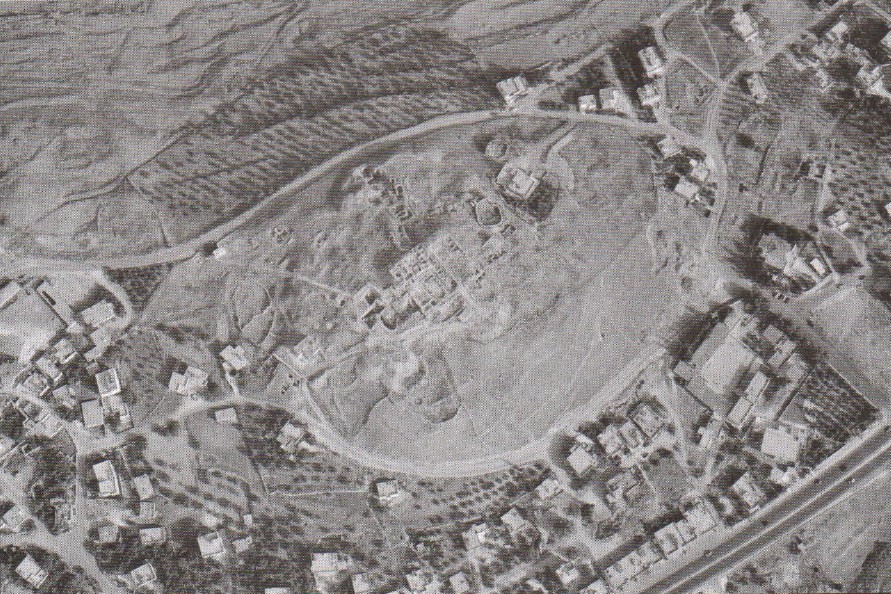

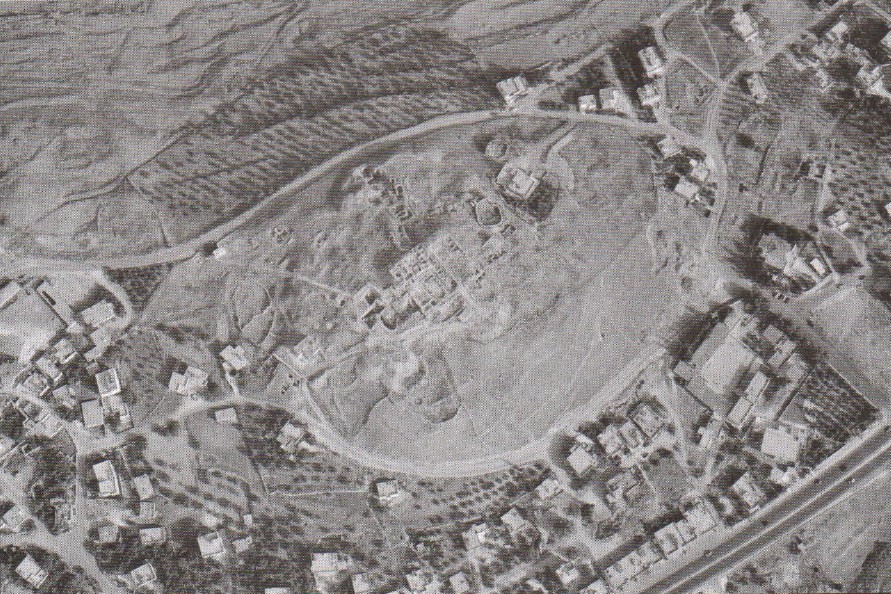

APAAME

- Reference: APAAME_20211022_FB-0048

- Photographer: Firas Bqain

- Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

- Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

Click photo for high res magnifiable image

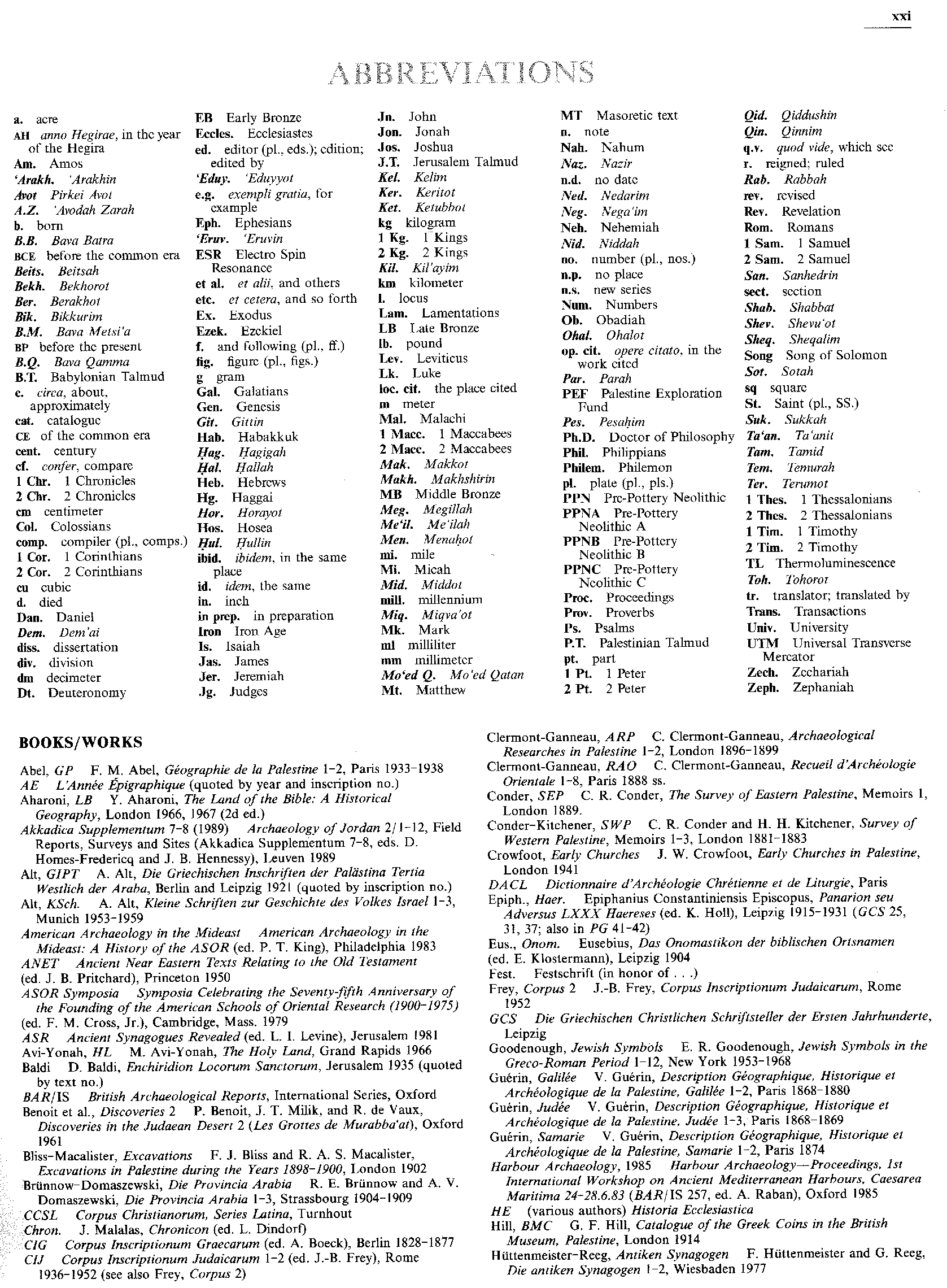

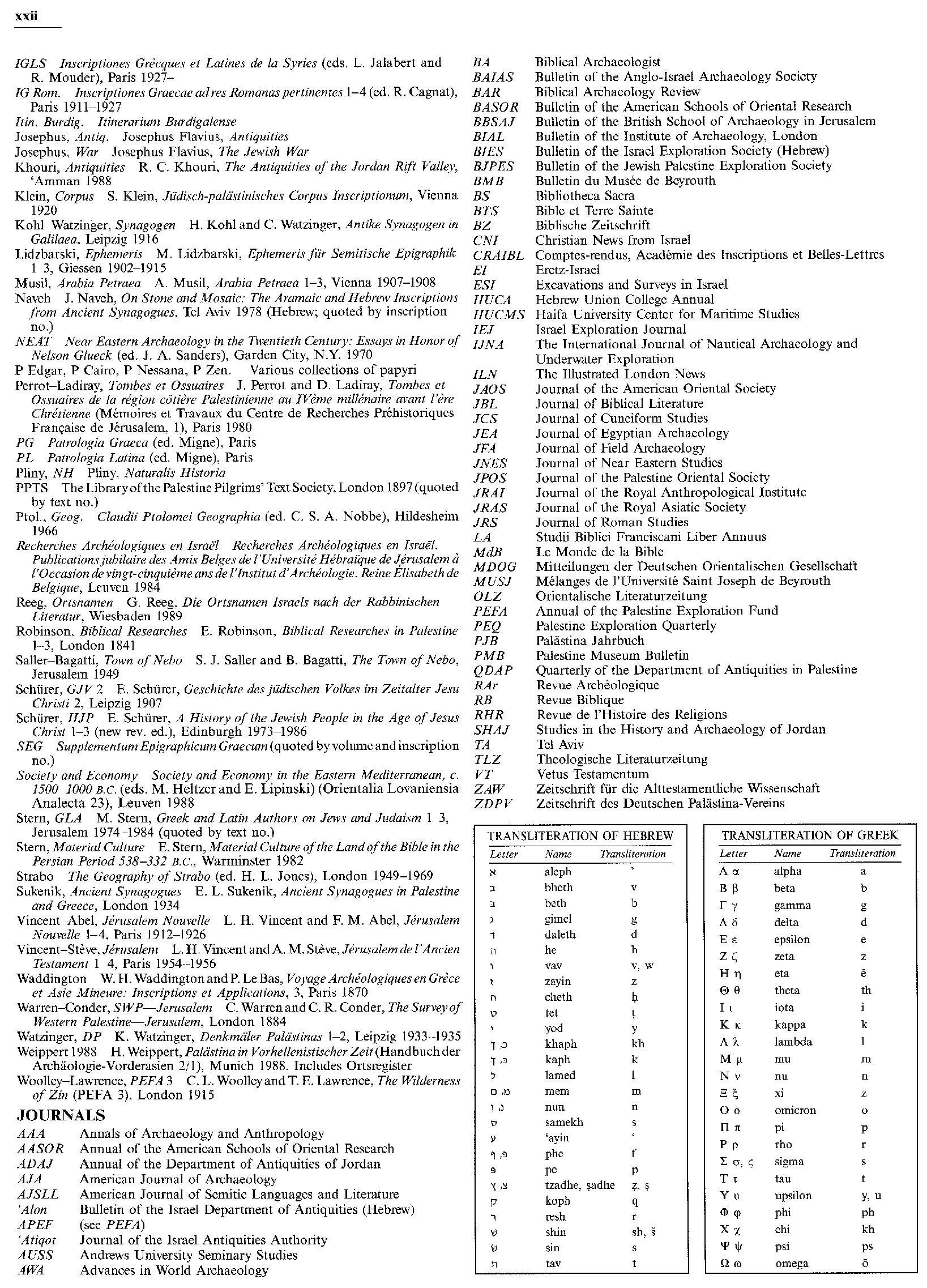

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Hesban | | |

| Heshbon | Biblical Hebrew | חשבון |

| Heshbon | Arabic | حشبون |

| Tell Hisban | Arabic | تيلل هيسبان |

| Tell Ḥesbān | Arabic | تيلل هيسبان |

| Esebus | Latin | |

| Esbus | Latin | |

| Hesbonitis | Greek | Εσεβωνιτις |

| Hesebon | Ancient Greek | Ἐσεβών |

| Esbous | Ancient Greek | Ἐσβούς |

| Exbous | Ancient Greek | Ἔξβους |

| Esbouta | Ancient Greek | Ἐσβούτα |

| Essebōn | Ancient Greek | Ἐσσεβών |

| Esb[untes] |

For both geographical and linguistic reasons, Heshbon is identified with Tell Hesban, an 895-m-high, 15-a. mound guarding the northern edge of the rolling Moabite plain. Here, a southern tributary to Wadi Hesban begins to cut sharply down toward the Jordan River, about 25 km (15.5 mi.) to the west (map reference 226.134). Eusebius locates "Hessebon, now called Hesbous" 20 Roman miles (c. 30 km) east of the Jordan River, in the mountains opposite Jericho (Onom. 84:5). A ground course from the Jordan River would place the approximate location of Tell Hesban, here. Several milestones along the Roman road from the Jordan Valley and the Bible's reference to Heshbon's location confirm this identification. It is about 60 km (37 mi.) east of Jerusalem, 20 km (12 mi.) southwest of 'Amman, 9 km (5.6 mi.) north of Medeba, 8km (5 mi.) northeast of Mount Nebo, and 3 km (2 mi.) southeast of (and 200 m higher than) 'Ain Hesban, the perennial spring with which it is associated.

The excavations at Tell Hesban have so far produced no evidence for an occupation earlier than the twelfth century BCE. This poses a problem for locating Sihon's capital (see below) here. It may not have been found because it is elsewhere on the site, which is unlikely, or, which is more likely, because its seminomadic (impermanent) nature left no trace to be discovered. More extreme options are to consider the biblical account unhistorical or at least anachronistic (now favored by such scholars as J. M. Miller, H. 0. Thompson, and others) or to seek the Amorite capital at another location - for example, Jalul (an identification favored by S. H. Horn) or 'Umeiri (a view favored by R. D. Ibach). Most, at least, would identify Tell Hesban with Greco Roman Hesbus, based on numismatic and milestone evidence coupled with the geographical specifications as provided by Ptolemy and Eusebius. If F. M. Cross's reading of the Ammonite ostracon (A.3), found at the site in 1978, is accepted, it would support such an identification for Iron Age Heshbon, as well.

Heshbon is first mentioned in the Bible in Numbers 21:21-30 (cf. Dt. 2:16-37), where it is referred to as the city of Sihon, king of the Amorites, whose kingdom extended "from Aroer, which is on the edge of the valley of Arnon, and from the middle of the valley as far as the river Jabbok, the boundary of the Ammonites, that is, half of Gilead" (Jos. 12:2; cf. Jos. 13:10, Jg. 11:22). Numbers 21:26-31 may be - in the writer's opinion - an attempt to justify Israel's occupation, under Moses, of territory claimed at various times by Moab. This passage claims that at least the southern half of Sihon's kingdom, the tableland known in Hebrew as the Mishor (Dt. 3:10, 4:43), had indeed been Moabite but that Sihon had earlier wrested it from Moabite control (Num. 21:26). As proof, the so-called Song of Heshbon (Num. 21:27-30), ostensibly an Amorite war taunt, was inserted in the narrative. This claim was again made in Judges 11:12-28, where Jephthah denies the Ammonites ownership of the region between the Jabbok and Arnon on the basis that Israel originally took it from the Amorites and not the Ammonites.

The tribes of Reuben and Gad requested the territory that had been encompassed by Sihon's kingdom for their tribal allotment on the basis of its being good for their cattle (Num. 32: 1-5). It was, however, actually Reuben that built Heshbon and other nearby towns (Num. 32:37) which, according to the difficult and cryptic next verse, "changed as to name ... and they called by (other?) names the names of the cities which they built." Joshua 13:15-23 confirms the allotment of Heshbon to Reuben, although the next few verses (24-28) indicate it was contiguous with Gad's allotment. When Heshbon became a Levitical city, it was considered a city of Gad (Jos. 21:34-40; cf. 1 Chr. 6:8) - apparently because Reuben lost its tribal identity and was absorbed by Gad.

Although Heshbon is not mentioned by name in connection with the history of the United Monarchy, 1 Kings 4:19 puts "the land of Gilead, the country of Sihon king of the Amorites" in Solomon's twelfth district. The Mesha Stone (ninth century BCE) does not mention Heshbon, but because Medeba, Nebo., and Jahaz all came back into Moabite hands at that time, presumably Heshbon did as well. At least by the close of the eighth century and into the seventh century BCE, Heshbon appears to be under firm Moabite control, for it figures in both extant recensions of a prophetic oracle against Moab (Is. 15:4, 16:8-9; Jer. 48:2, Jer. 48:34-35), where its fields, fruit, and harvest are mentioned. In Jeremiah 49:3, Heshbon appears again in the oracle against the Ammonites; perhaps it had changed hands again. Heshbon's final biblical mention is in Nehemiah 9:22, where it is part of a historical allusion to the Israelite conquest.

In the post-biblical literary sources, Heshbon is commonly called Hesbus (although there are many variant spellings). Josephus relates that in the second century BCE, Tyre of the Tobiads was located "between Arabia and Judea, beyond Jordan, not far from the country of Hesebonitis (Εσεβωνιτις)" (Antiq. XII, 233). Further on he lists Heshbon among the cities (perhaps the capital) of the Moabites (Antiq. XIII, 397). The Maccabean John Hyrcanus captured the cities of Medeba and Samaga in 129 BCE (Antiq. XIII, 255). Even though Hesbus is not specifically mentioned, it probably came into the hands of John Hyrcanus at this time because it is listed among the Jewish possessions in Moab during the reign of Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BCE), not as a city captured by him (Antiq. XIII, 397).

Josephus includes Hesebon among several fortresses and fortified cities built by Herod the Great to strengthen his kingdom (Antiq. XV, 294); he populated it with veterans, probably to protect his border with the Nabateans. Under Herod's son, Antipas (4 BCE-39 CE), Jewish Peraea was on the south "bounded by the land of Moab, and on the east by Arabia, Hesebonitis, Philadelphia, and Gerasa" (War III, 4 7). At the beginning of the [1st] Jewish War (66 CE), the Jews sacked Heshbon (War II, 458). When the Roman province of Arabia Petraea was created in 106 CE, Hesbus was certainly a part of it; at least it is assigned to Arabia in Ptolemy's Geography (V, 17, 6).

W. Vyhmeister has summarized the evidence with regard to the Roman road: "Around 129-130, in preparation for the visit of the Emperor Hadrian, a road was built to connect Esbus with Livias, Jericho, and Jerusalem ... " Three milestones (5-7) recording distances from Hesbus have been discovered. Two bear inscriptions naming several emperors and are so dated to the years 219,307 and 364-375 (no. 5) and 162,236 and 288 (no. 6). The mention of Hesbus as caput viae in Greek and Latin is an indication of its relative importance in this period.

Elagabalus (218-222 CE) raised Hesbus to municipal status, and in the early third century it minted its own bronze coins inscribed "Aurelia Esbus" (BMC Arabia, XXXIII, 29-30). At the turn of the century the town is frequently mentioned in Eusebius' Onomasticon as a reference for locating other towns in its district. In the next century, Hesbus appears for the first time as an episcopal see in the Acts of the Council of Nicaea. Again Hesbus sent its bishop to the Councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (457). Some correspondence of Pope Martin I(649) shows that Hesbus was still an important bishopric in the middle of the seventh century (R. Le Quien, Oriens Christianus, II, cols. 863-864).

A number of Greek Christian inscriptions were discovered at Heshbon (IGLS, Jordanie, nos. 58-62). Moreover, the town is represented in two eighth-century mosaic pavements featuring cities of Palestine, Arabia and Egypt, at Ma'in and Umm er-Rasas.

After the eighth century, the name Hesbus disappears from literary and epigraphic sources, reappearing only in its Arabic form, Hesban. It is mentioned in the Abbasid period by the Arab geographer, Yaqut - who says there was a strong fortress here in the early ninth century- and Abu Dja'far Muhammad at-Tabari (839-923). The next clear reference to Hesban as an inhabited place comes in 1184, in connection with a campaign of Saladin recorded by Beha ed-Din. In the fourteenth century, Hesban became the capital of the Belqa district and is mentioned by Ibn Fadl Allah al-'Umari (1301-1348), Dimishqi (d. 1327), Abu el-Feda (d. 1331), and several others. Finally, several Western travelers and explorers visited Hesban, particularly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from U. J. Seetzen in 1806 to N. Glueck in the early 1930s.

Six seasons of excavations have been carried out at Tell Hesban, the first five by the Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan, and the last by the Baptist Bible College, Clarks Summit, Pennsylvania, both with the cooperation of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the Jordan Department of Antiquities. The first three seasons (1968, 1971, 1973) were directed by S. H. Horn, and the fourth and fifth (1974 and 1976) by L. T. Geraty. R. S. Boraas provided continuity throughout as chief archaeologist. In 1978, J. Lawlor directed the continued excavation of the northern Byzantine church (found two years earlier), with the assistance of Geraty as senior advisor and L. G. Herr as chief archaeologist.

In the first season of excavation, the site was marked off by a major north-south and east-west pair of axes centered on the summit. The initial strategy was to cut a series of squares along the west and south lines of the intersection, providing a continuous stratigraphic connection from the west perimeter of the mound up to the center of the summit, then down the south slope to the edge. Eventually this was accomplished through the gradual expansion of four work areas (areas A-D, with 32 squares). These were carried down to bedrock and augmented in later seasons by investigations scattered around the perimeter of the site (22 squares), by tomb research carried out in four widely separated cemeteries (43 tombs), by a sounding at Umm es-Sarab to the north, and by a survey team seeking sites within a 10-km (6-mi.) radius of Tell Hesban (155 sites). On the mound itself, a series of nineteen superimposed, distinguishable strata was identified. These covered a period from about 1200 BCE to 1500 CE, with only two primary gaps in occupation in evidence: Persian and Early Hellenistic (c. 500-250 BCE) and Ottoman (c. 1500-1870).

- from Stern et. al. (2008)

...

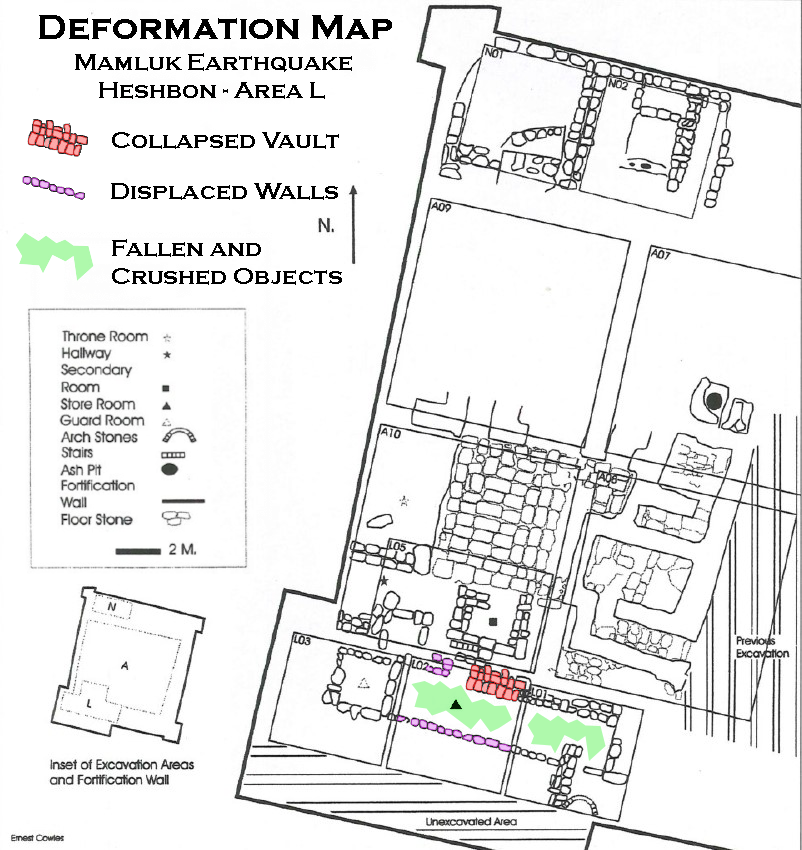

The renewed excavations at Heshbon (Ḥisban) took place between 1996 and 2001. The results rectify some of the impressions left by the 1970s excavations at the site, in which the Early Islamic period was mainly represented by provisional ovens and pottery. The present excavations not only uncovered clear Umayyad architectural activity at the tell (field N, to the northwest), but also material evidence of its continued use throughout the Abbasid period. Another highlight is that the residence of the Mameluke governor of the Belqa is believed to have been found. Heshbon was the administrative capital of the region, mainly due to its geographically advantageous location. The structure exposed includes rooms organized around an open courtyard, with a defensive tower and a bathhouse. The archaeological value of the above findings is further enhanced by the fact that the Mameluke layer was sealed by the building collapse as a result of an earthquake in the late fourteenth–early fifteenth century. This collapse helped preserve in situ the contents of a storeroom on the southern side of the residence, full of sugar jars and glazed wares, including the typical molded ware usually decorated with inscriptions.

- Heshbon in Google Earth

- Fig. 3 - Aerial Photo of Heshbon

from Walker et al (2017)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Aerial photo of Tall Hisban a mediaeval village below (courtesy of Ivan LaBianca)

Walker et al (2017)

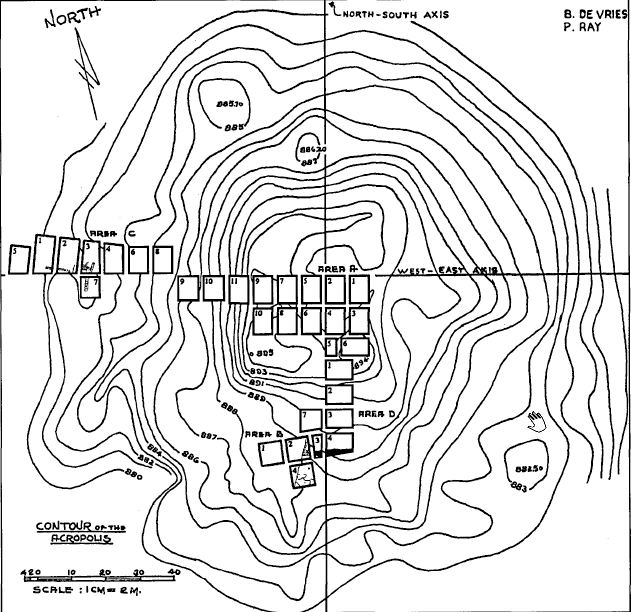

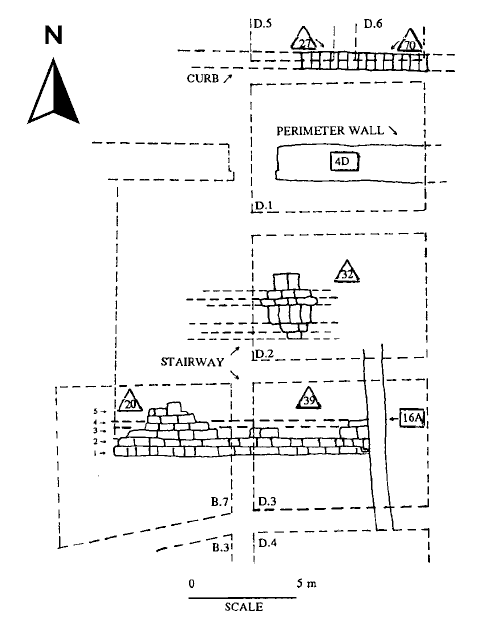

- Fig. 1.2 Site Plan with excavation areas from Ray (2001)

- Site Plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2)

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

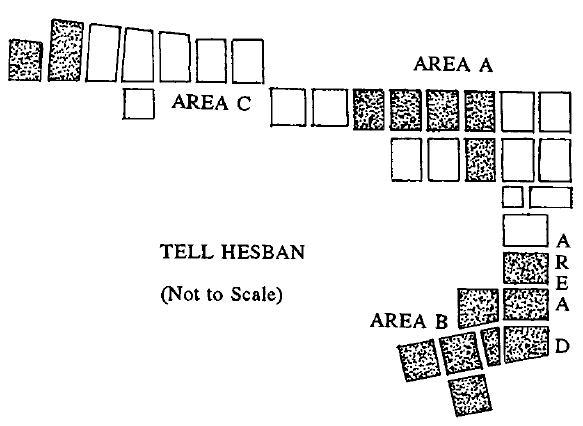

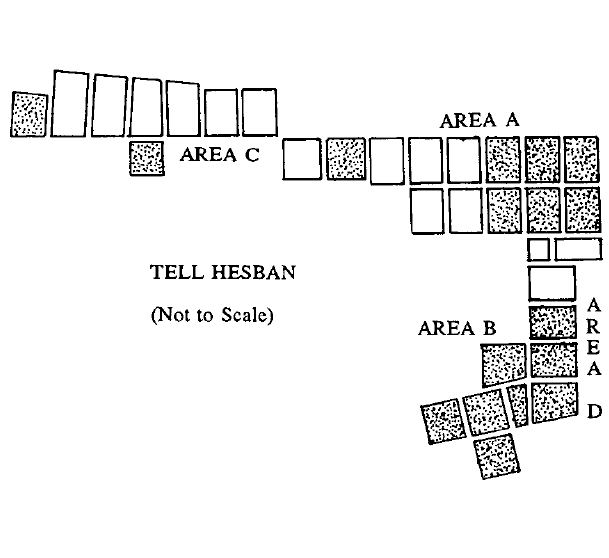

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 2 - Areas of excavations

at Tell Heshbon from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Areas of excavations (Bert de Vries, Calvin College; Paul Ray, Jr., Andrews University; Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University; and Marvin Bowen, Andrews University).

Walker and LaBianca (2003) - Fig. 2 - Area Map from

Walker et al (2017)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Fields of excavation (courtesy of Qutaiba Dasouqi)

Walker et al (2017)

- Fig. 1.2 Site Plan with excavation areas from Ray (2001)

- Site Plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2)

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 2 - Areas of excavations

at Tell Heshbon from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Areas of excavations (Bert de Vries, Calvin College; Paul Ray, Jr., Andrews University; Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University; and Marvin Bowen, Andrews University).

Walker and LaBianca (2003) - Fig. 2 - Area Map from

Walker et al (2017)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Fields of excavation (courtesy of Qutaiba Dasouqi)

Walker et al (2017)

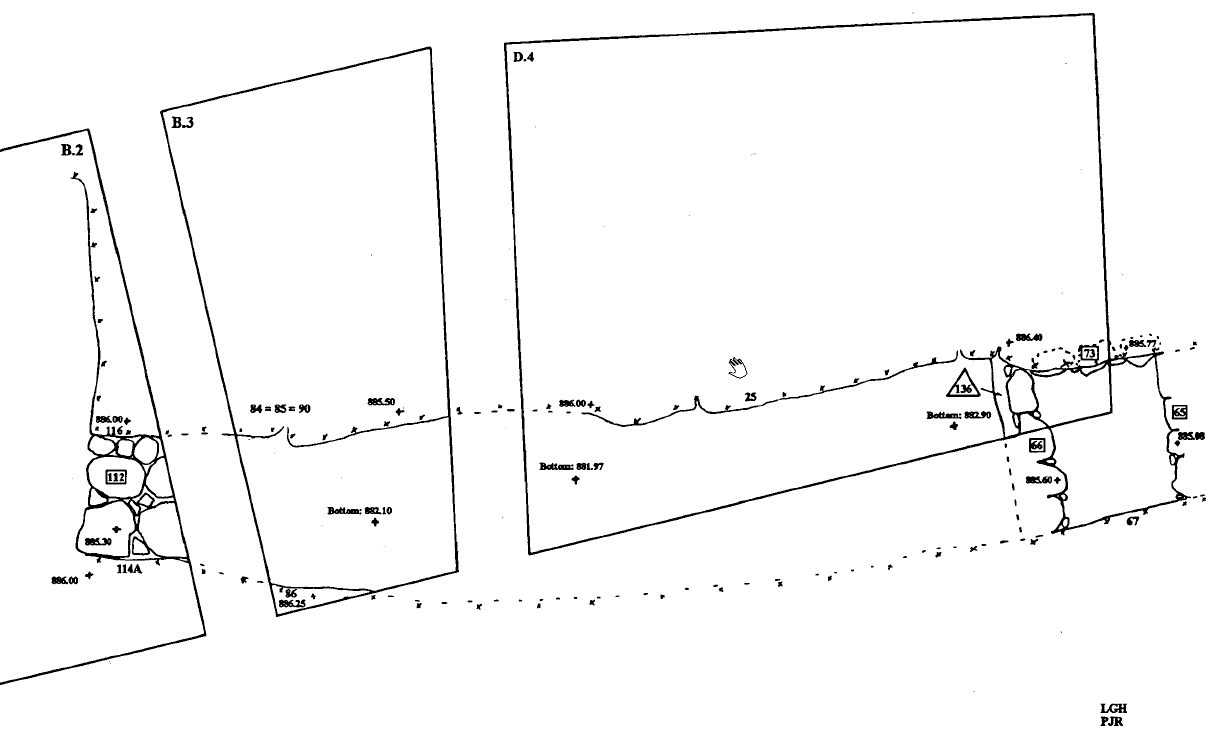

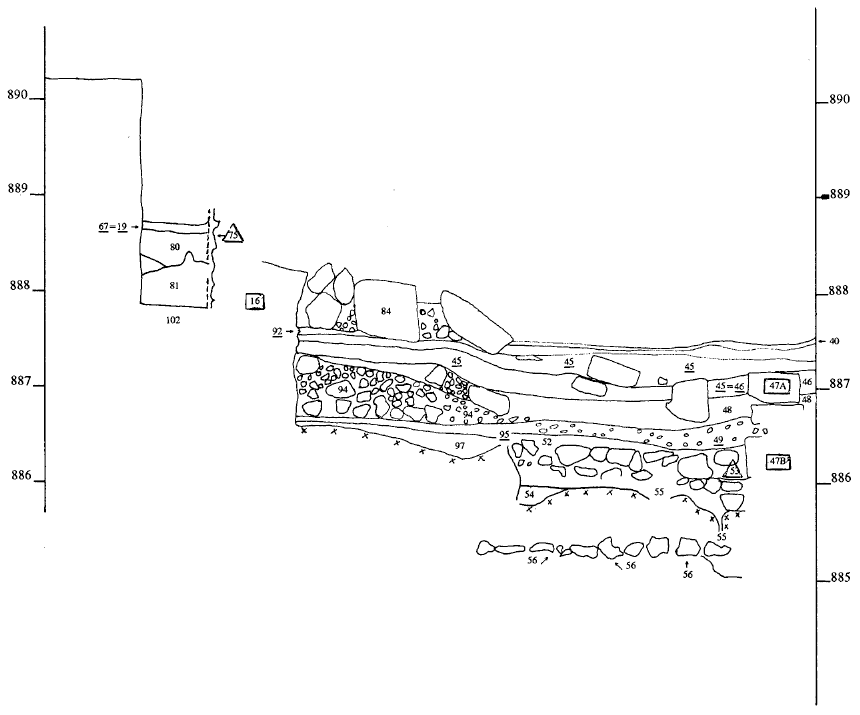

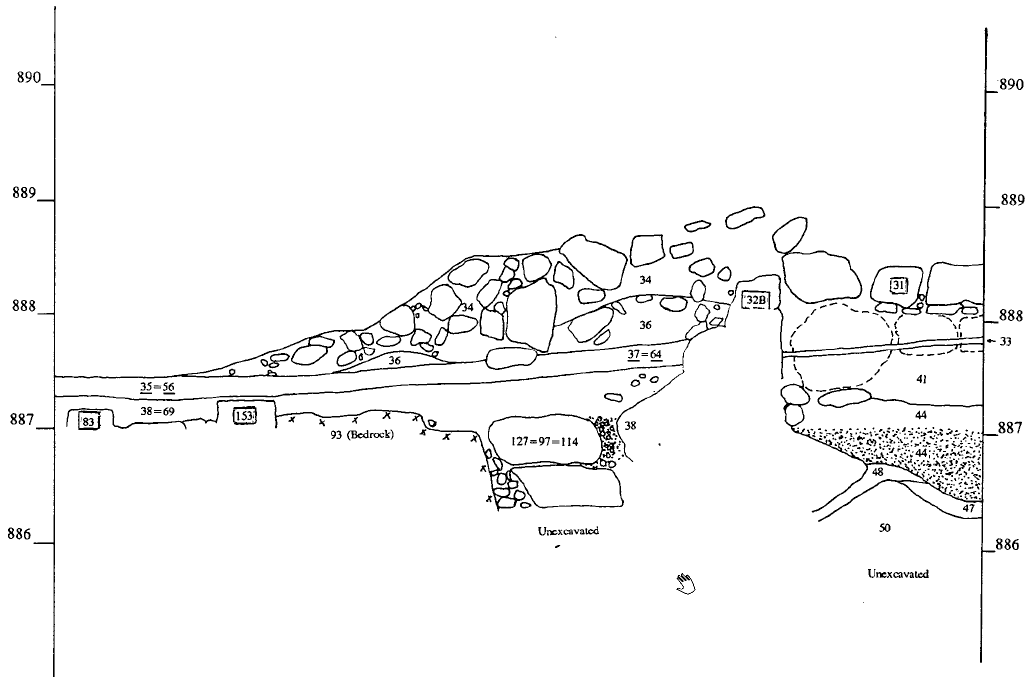

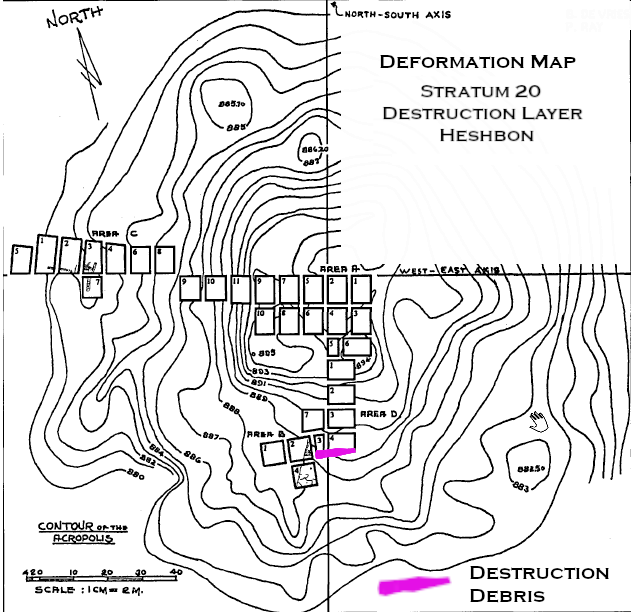

- Fig. 5.10 Stratum 20

Bedrock Trench from Ray (2001)

- Fig. 5.10 Stratum 20

Bedrock Trench from Ray (2001)

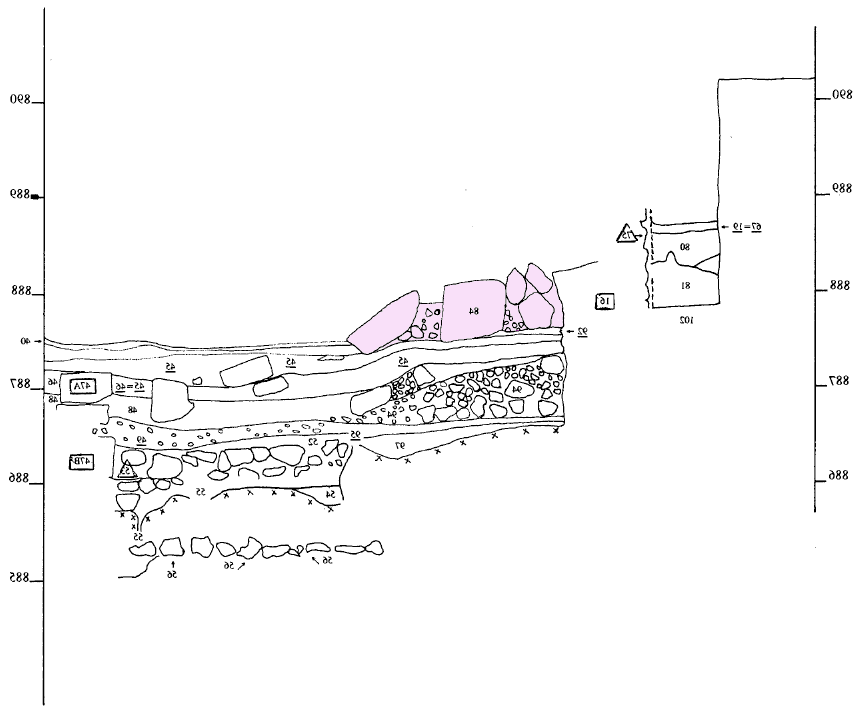

- Fig. 3.1 Stratum 14 Significant Remains from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 3.1 Stratum 14 Significant Remains from Mitchel (1992)

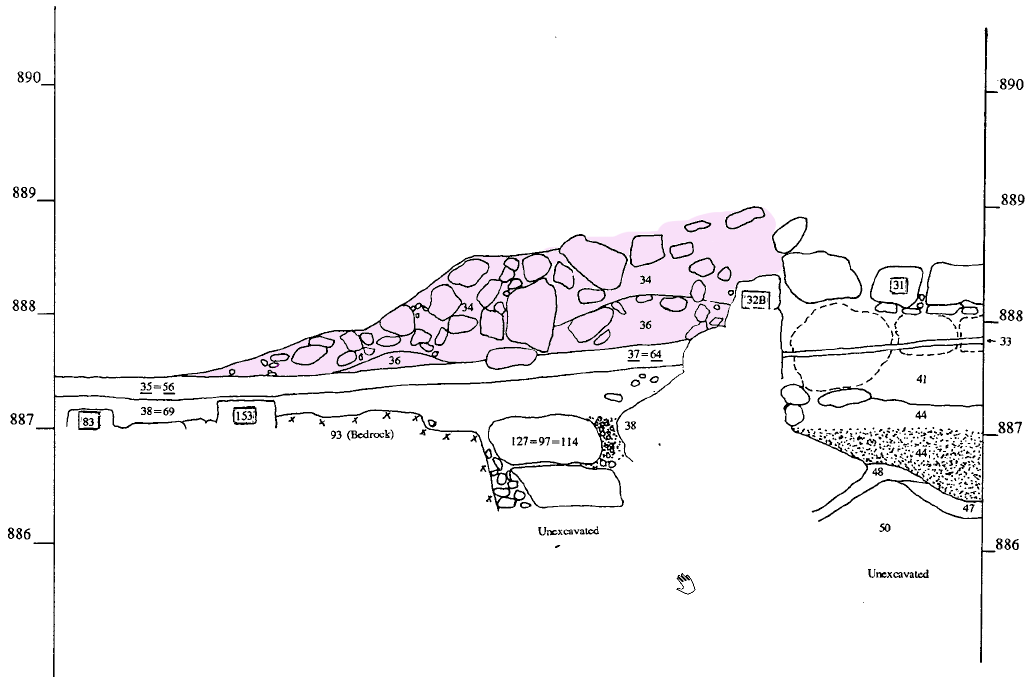

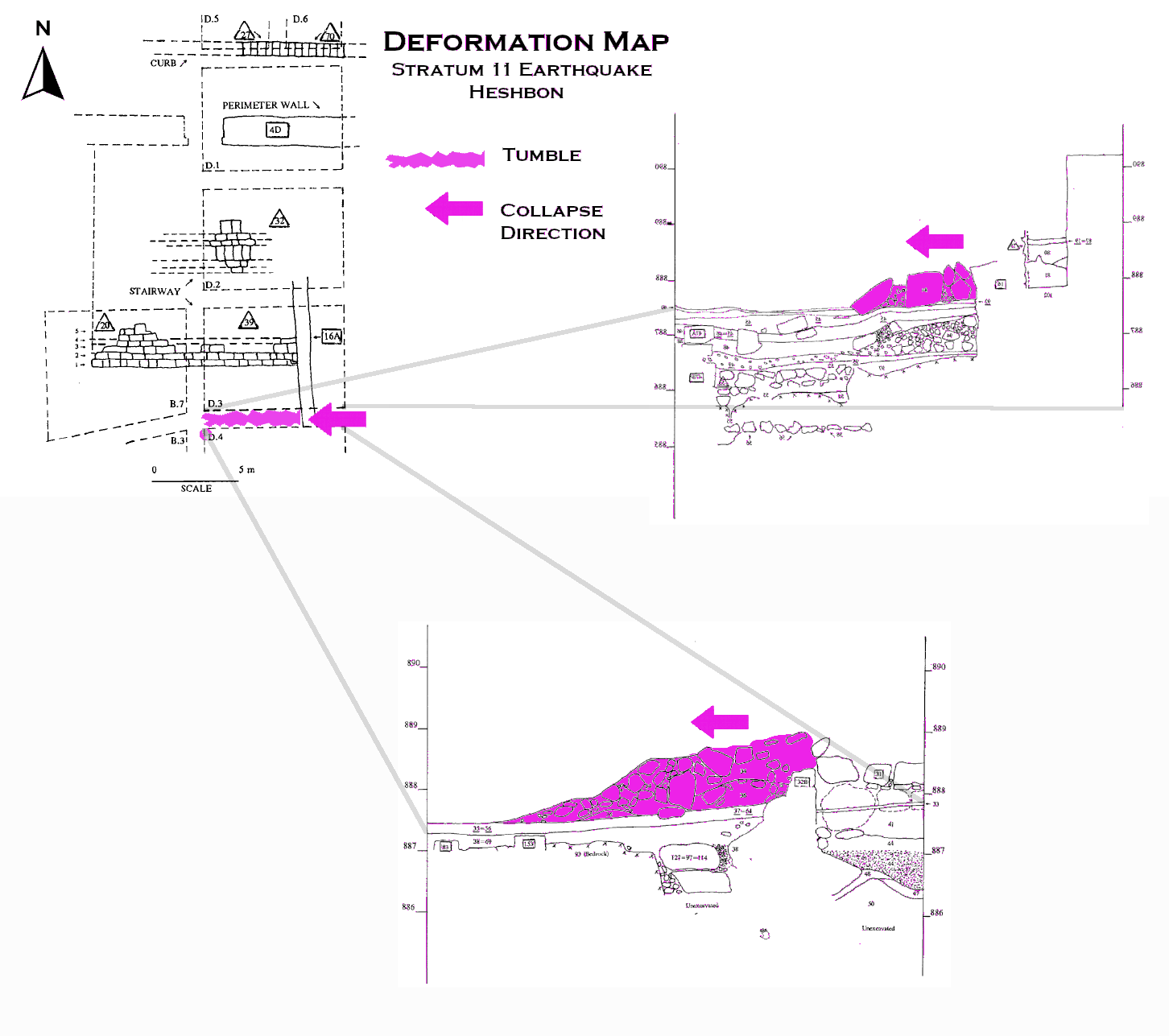

- Fig. 6.1 Stratum 11 Significant Remains from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.3 Collapsed Monumental Stairway of Stratum 11 from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.1 Stratum 11 Significant Remains from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.3 Collapsed Monumental Stairway of Stratum 11 from Mitchel (1992)

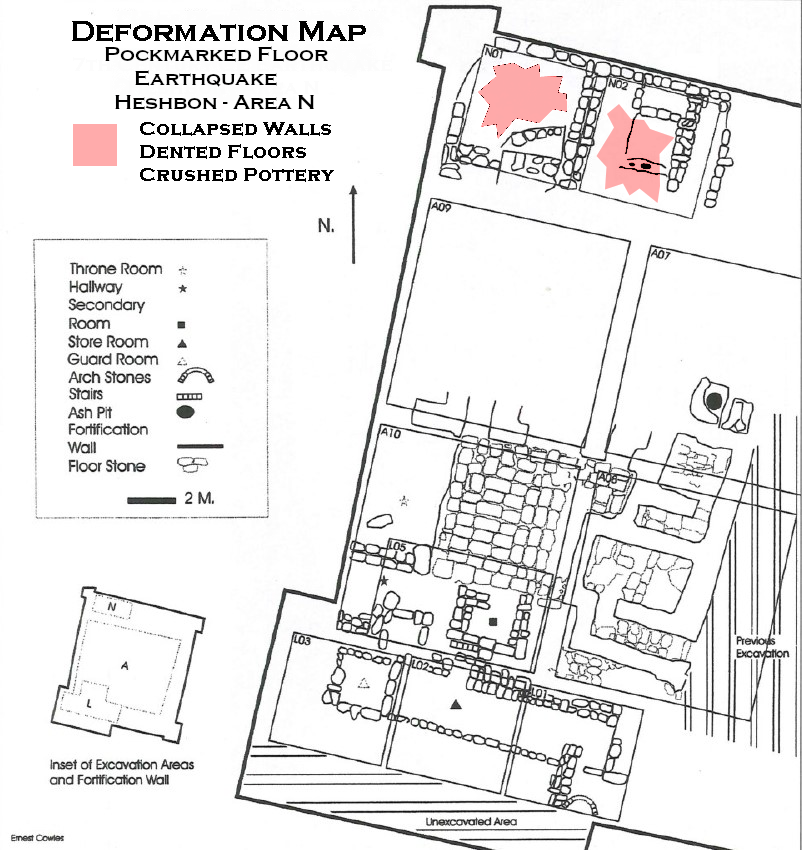

- Fig. 4 - Floor plan of Mamluk

and Umayyad buildings from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Floor plan of Mamluk and Umayyad buildings, 2001 season (map by Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University). The bathhouse is the three-room structure occupying A08.

Walker and LaBianca (2003)

- Fig. 4 - Floor plan of Mamluk

and Umayyad buildings from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Floor plan of Mamluk and Umayyad buildings, 2001 season (map by Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University). The bathhouse is the three-room structure occupying A08.

Walker and LaBianca (2003)

- Fig. 6.4 Square D.3 South Balk with Tumble Layer Colored from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.5 Square D.4 North Balk with Tumble Layer Colored from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.4 Square D.3 South Balk from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.5 Square D.4 North Balk from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.4 Square D.3 South Balk with Tumble Layer Colored from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.5 Square D.4 North Balk with Tumble Layer Colored from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.4 Square D.3 South Balk from Mitchel (1992)

- Fig. 6.5 Square D.4 North Balk from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.13 Square D.3

South Balk, West Section (A.I. Enhanced) from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.14 Square D.4 North Balk (A.I. Enhanced) from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.15

Huwwar Layers

South of Stairway (A.I. Enhanced) from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 25A East Margin

of Monumental Stairway in Square D.3 (A.I. Enhanced) from Mitchel (1980)

- Pl. 6.13 Square D.3 South Balk, West Section from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.14 Square D.4 North Balk from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.15 Huwwar Layers South of Stairway from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 25A East Margin

of Monumental Stairway in Square D.3 from Mitchel (1980)

- Stairs at Heshbon - photo by JW

- Stairs at Heshbon - photo by JW

- Rooms N.1 and N.2 (?) - photo by JW

- Pl. 6.13 Square D.3

South Balk, West Section (A.I. Enhanced) from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.14 Square D.4 North Balk (A.I. Enhanced) from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.15

Huwwar Layers

South of Stairway (A.I. Enhanced) from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 25A East Margin

of Monumental Stairway in Square D.3 (A.I. Enhanced) from Mitchel (1980)

- Pl. 6.13 Square D.3 South Balk, West Section from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.14 Square D.4 North Balk from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 6.15 Huwwar Layers South of Stairway from Mitchel (1992)

- Pl. 25A East Margin

of Monumental Stairway in Square D.3 from Mitchel (1980)

- Stairs at Heshbon - photo by JW

- Stairs at Heshbon - photo by JW

- Rooms N.1 and N.2 (?) - photo by JW

Dating earthquakes at this site before the 7th century CE is messy. Earlier publications provide contradictory earthquake assignments, possibly due to difficulties in assessing stratigraphy and phasing, but also due to uncritical use of older error prone earthquake catalogs. A number of earlier publications refer to earthquakes too far away to have damaged the site. Dates provided below are based on my best attempt to determine chronological constraints based on the excavator's assessment of primarily numismatic and ceramic evidence. Their earthquake date assignments, at the risk of being impolite, have been ignored.

| Stratum | Political periodization | Cultural Period | Absolute Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Late Ottoman-modern | Late Islamic IIb-modern Pioneer, Mandate, and Hashemite |

1800 CE-today |

| II | Middle Ottoman | Late Islamic IIa Pre-modern tribal |

1600-1800 CE |

| IIIb | Early Ottoman | Late Islamic Ib Post-Mamluk - Early Ottoman |

1500-1600 CE |

| IIIa | Late Mamluk (Burji) | Late Islamic Ia | 1400-1500 CE |

| IVb | Early Mamluk II (Bahri) | Middle Islamic IIc | 1300-1400 CE |

| IVa | Early Mamluk I (Bahri) | Middle Islamic IIb | 1250-1300 CE |

| IVa | Ayyubid/Crusader | Middle Islamic IIa | 1200-1250 CE |

| V | Fatimid | Middle Islamic I | 1000-1200 CE |

| VIb | Abbasid | Early Islamic II | 800-1000 CE |

| VIa | Umayyad | Early Islamic I | 600-800 CE |

| VII | Byzantine | Byzantine | 300-600 CE |

| VIII | Roman | Roman | 60 BCE - 300 CE |

| IX | Hellenistic | Hellenistic | 300-60 BCE |

| X | Persian | Persian | 500-300 BCE |

| XIb | Iron II | Iron II | 900-500 BCE |

| XIa | Iron I | Iron I | 1200-900 BCE |

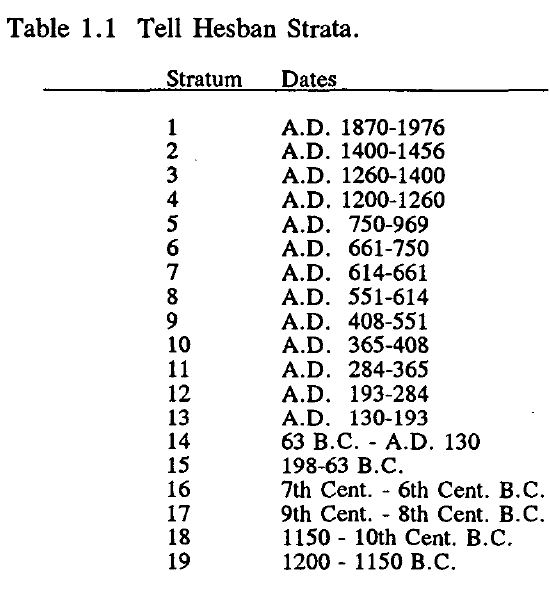

| Stratum | Period | Dates | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | LB/Iron I Transition–Iron IA | 1225–1150 B.C. | Very little exists from the first recognizable settlement that was built on Tell Hesban. The extant remains consist of ceramic material found within dump layers on the western side of the mound. Nevertheless, this evidence, when compared with that of some other tells in the immediate region as well as sites in the Central Hill Country of Cisjordan, suggests that a small village of Reubenites existed on the tell during the Late Bronze Age/Iron Age I transition. |

| 20 | Iron IA–IB | 1150–1100 B.C. | Tell Hesban appears to have been a large fortified village during this stratum. Though the tell was naturally defensible on three sides because of its steep sides and deep wadis, the occupants of this early settlement dug a trench in bedrock on the weak southern side of the mound. This feature appears to have functioned as a dry moat. Large amounts of stone within the destruction debris found in the trench suggest the possibility that a fortification wall may also have originally stood above it. The ceramic evidence would again suggest that the village was inhabited by Reubenites. |

| 19 | Iron IB | 1100–1050 B.C. | Stratum 20 seems to have been destroyed [JW: Ray (2001:93)

suggests the destruction was due to milary activity]. The moat went out of use, apparently leaving the now smaller village without fortifications.

A wall was built across the trench possibly as part of a new reservoir. The little that is available of the remains of Stratum 19 would

suggest that its character and ethnic makeup remained pretty much the same as the previous settlement. The villages of Strata 21 through 19 appear to have relied upon a medium intensity food production regime, which consisted of a mixed agro-pastoralism, heavily dependent on cereal cultivation and the products from sheep and goats. Cottage industries seemed to have played a major role among the economic activities. |

| 18 | Iron IB–IIA | 1050–925 B.C. | The Reubenite village of Stratum 19 appears to have grown into a small town during Stratum 18 under the auspices of the kingdom of Solomon.

A large reservoir was built at this time. The sophistication of the ashlar masonry of the extant wall of this feature suggests that it

was built under royal patronage. There is also evidence for a basement structure of a house dug into the upper layers of the bedrock

trench. It is possible that the town had a peripheral belt of houses surrounding it that functioned as a kind of a fortification during

this stratum. The settlement at this time appears to have had a high intensity food production regime. Though still producing large amounts of grain and keeping herd animals, it was also in the process of extending its repertoire into olive, fruit, and wine production. Though still basically a subsistence-oriented economy, evidence of mercantile activities and a fairly wide trade network indicate the beginnings of a market-oriented economy. Its position at the crossroads of the main north-south highway and the east-west trunk road from Cisjordan allowed it to dominate the caravan traffic along these roads. |

| 17 | Iron IIB | 925–700 B.C. | Iron Age IIB Hesban appears to have been rather sparsely inhabited and would seem to have been a Moabite squatter settlement as indicated by its ceramic makeup. I have suggested that an early Moabite occupation toward the end of the tenth century B.C. was expanded (slightly) by either Mesha or still later Moabites. They appear to have extended their territory north to Hesban and made use of its dominating position at the crossroads of the major highways to gather tolls. I have further suggested that they cleaned out and replastered the reservoir and used it for its capacity to hold large amounts of water. On the basis of the faunal remains, the occupants of the tell at this time seem to have been mainly pastoralists. Thus, this period appears to have been one of abatement, when the inhabitants of the site returned to range-tied pastoralism and a low to medium intensity food regime. |

| 16 | Iron IIC/Persian | 700–500/450 B.C. | Probably in the beginning of the seventh century B.C., in the Iron IIC/Persian period, Tell Hesban became Ammonite, under the dominance of the Assyrians and then later the Babylonians and Persians. The site once again grew to the size of a small town extending even beyond the size of the Stratum 18 settlement, as an offset-inset wall was built on the western shelf. Water needs were taken care of by the addition of several new feeder channels to the reservoir. Stratum 16 was the most prosperous of the Iron Age settlements on the tell. It moved to a market-oriented economy heavily involved in wine production. The latter is indicated, besides evidence from the seeds, by a number of silos, which appear to have been used for wine storage. Evidence, including weights, jewelry, ostraca, and seals, indicates mercantile activities and a fairly wide trade network. The location of the site on the crossroads of the main north-south highway and the east-west trunk road from Cisjordan would seem to have helped the site, as at earlier times, to continue to dominate the caravan traffic which traveled through the region. Seed and faunal evidence indicate a return to a high intensity food production regime. |

- from Storfjell (1993)

- from Storfjell (1993)

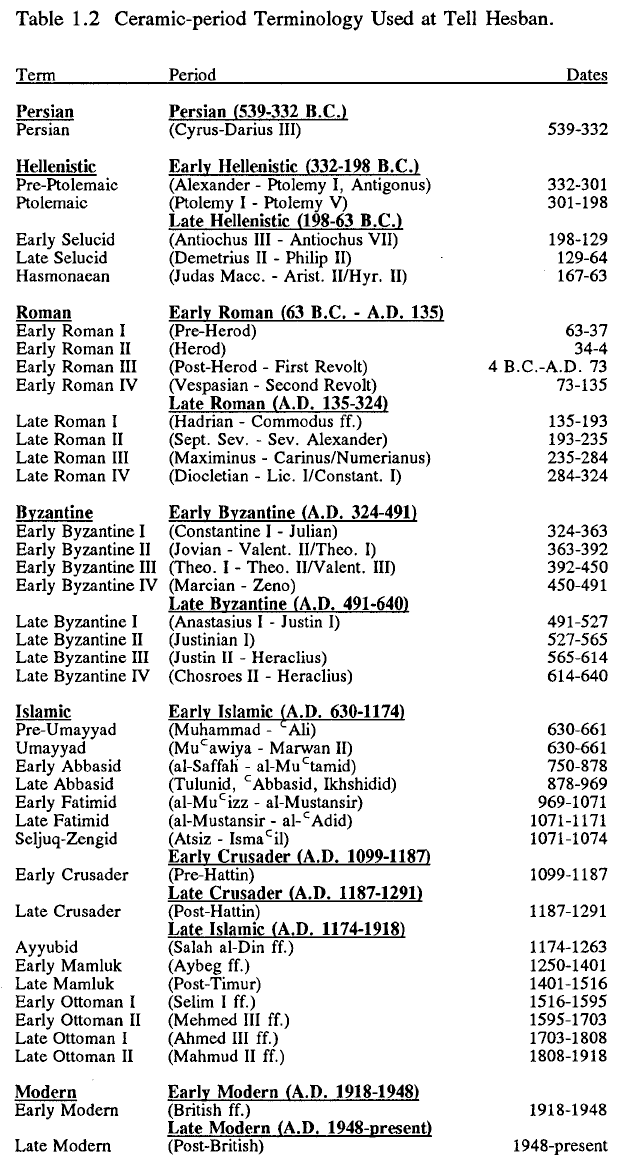

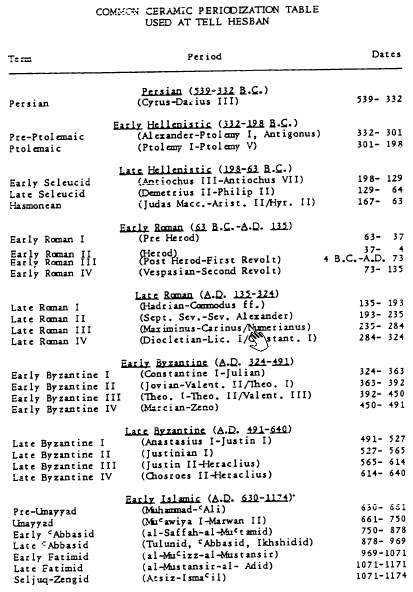

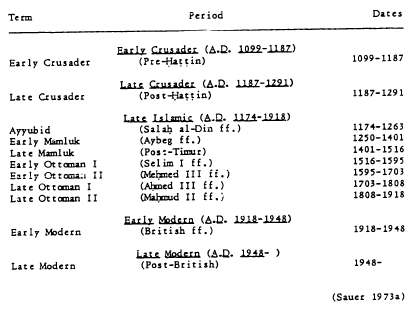

Table 2

Table 2Common Ceramic Periodization Table used at Tell Hesban

Click on image to open in a new tab

Storfjell (1983)

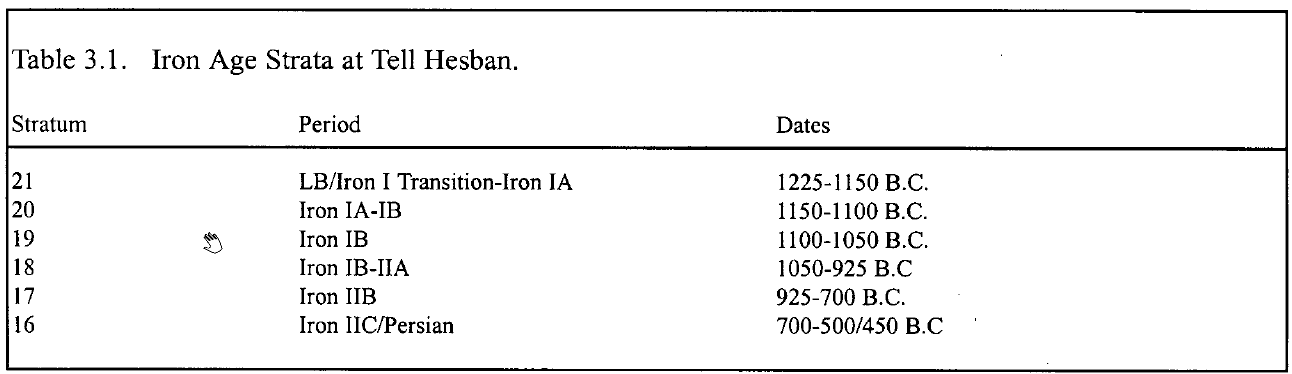

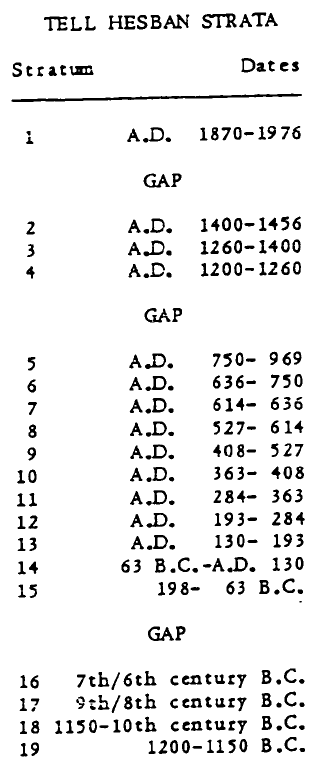

- Mitchel (1980:9) provided a list of 19 strata encountered over 5 seasons of excavations between 1968 and 1976.

- Mitchel (1980) wrote about Strata 11-15.

| Stratum | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1870-1976 CE | |

| 2 | 1400-1456 CE | |

| 3 | 1260-1400 CE | |

| 4 | 1200-1260 CE | |

| 5 | 750-969 CE | |

| 6 | 661-750 CE | |

| 7 | 614-661 CE | |

| 8 | 551-614 CE | |

| 9 | 408-551 CE | |

| 10 | 365-408 CE | |

| 11 | 284-365 CE | Stratum 11 is characterized by another building program. On the temple grounds a new colonnade was built in front (east) of the temple, perhaps a result of Julian's efforts to revive the state cult. |

| 12 | 193-384 CE | Stratum 12 represents a continuation of the culture of Stratum 13. On the summit of the tell a large public structure was built; partly following the lines of earlier walls. This structure is interpreted to be the temple shown on the reverse of the so—called "Esbus Coin", minted at Aurelia Esbus under Elagabalus (A.D. 218 — 222). |

| 13 | 130-193 CE | Stratum 13 began with a major building effort occasioned by extensive earthquake destruction [in Stratum 14] The transition from Stratum 13 to Stratum 12 appears to nave been a gradual one. |

| 14 | 63 BCE - 130 CE | the overall size of the settlement seems to have grown somewhat. Apart from the continued use of the fort on the summit, no intact buildings have survived. A large number of underground (bedrock) installations were in use during Stratum 14 The stratum was closed out by what has been interpreted as a disastrous earthquake |

| 15 | 198-63 BCE | architecture interpreted to be primarily a military post or fort, around which a dependent community gathered |

| 16 | 7th-6th century BCE | |

| 17 | 9th-8th century BCE | |

| 18 | 1150-10th century BCE | |

| 19 | 1200-1150 BCE | |

The meager remains of this stratum are confined to a bedrock trench on the southern shelf (in Squares B.2, B.3, and D.4; figs. 5.4-9) and a cistern along with its bottommost soil layer on the Acropolis in Square D.1.

The bedrock trench in Squares B.3 and D.4 was filled to the top with debris. This material contained a mixture of Iron Age IA and IB pottery along with the destruction debris of Stratum 20 which were found in loci B.3:74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 80, 81, 82, 83, 89, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 99; D.4:111?, 124, 125, 126, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, and 152. These layers consist of superimposed, and sometimes alternating, layers of soil, ash (B.3:74, 77, 94; D.4:126, 128, 129, 131, 132, 137, 145, 147, 149, and 151), and rock tumble (B.3:78, 80, 83, 92; D.4:144) (Sauer 1976: 60-61; 1978: 48; Herr 1979a: 9). A mortar, a door socket, four spindle whorls, and five pottery discs (pl. 5.2) which could have been blanks for other spindle whorls or alternatively may have served as jar stoppers or lids (Kotter 1979: 8; London 1991: 414, 417), spindle rests (Platt 1983: 3), game pieces, "bats" for the production of pottery or counters for accounting and business exchange (London 1991: 414, 417) were found within these layers.

Because of its depth and relative narrowness, the bedrock trench, which is the most notable feature of this stratum, is somewhat enigmatic, and exact parallels seem to be lacking. Therefore, a number of suggestions have been made regarding its function (Sauer 1976: 49; Geraty 1993: 628), most of which (dry storage and subterranean habitation) have been dismissed (Herr 1979a: 7–8). Although the so-called "Israelite shrine (?)" at Samaria (Crowfoot, Kenyon and Sukenik 1942: 23–24, fig. 11; pl. 1, feature 27, see also Steiner 1997: 19–21) remotely resembles the trench, this trapezoid-shaped feature is too dissimilar both in terms of its dimensions (4.00–6.00 m in width) and date (Iron Age II) to be a feasible parallel (Herr 1979b: 4). Other suggestions include water channel and dry moat (defensive cut) options (Fisher 1994: 86–87; Sauer and Herr 1997: 233).

Herr (1979a: 8) has suggested that this feature is a water channel. In favor of this proposal is the .80 cm decline of the trench from east (882.90 m) to west (882.10 m), suggesting that water flowed in this direction to a possible reservoir farther west (Herr 1979a: 5, 8). Herr did, however, note a number of problems with his own suggestion, the most significant being the irregularity of the bottom of the trench (e.g., it slopes to 881.97 m in one spot on the western end of Square D.4). He has also noted the lack of water-laid silt that would be expected to have been deposited in a facility bearing water. Although, on the basis of a suggestion from John Holladay (Herr 1979a: 8 n. 4), he attempted to explain the depth of the channel as being necessary because of the height of the bedrock at this spot, he pointed out that it would have been easier to cut the channel around the bedrock spur to the south (1979a: 8). Further, it should be noted that two of the feeder channels (B.4:242 and 244) for the large (ca. 17.5 m × 17.5 m, depth 7.00 m) reservoir, which was built later in the Iron Age and estimated to have had a capacity of 2,200,000 p (Sauer 1978: 48; Merling 1994: 215), were only ca. 0.25 m and 0.20 m wide and 0.25 m and 0.15 m deep, respectively. The former was plastered while the latter was not (Sauer 1976: 57). Though some of this bedrock area has collapsed since the Iron Age, it has been estimated that channel B.4:275C would have been ca. 0.65 m wide and ca. 0.55 m in depth (Sauer 1976: 58). Two factors mitigate against the suggestion that the bedrock trench was designed as a water channel. First, there was an easier route for channeling of water available only a short distance away. Second, the trench’s width and depth would suggest that another solution needs to be reached.

Another early suggestion for the function of the bedrock trench was that it was a defensive cut (Sauer 1978: 49) or dry moat. This was rejected by Herr (1979a: 7) partially because the trench was deeper than other Iron Age dry moats in the region. Iron Age sites with dry moats in the immediate region include Khirbet ʿAyun Musa (el-Meshhed; Site 108 of the Hesban Survey) (Glueck 1935: 110; 184, pl. 22, Site 238; Ibach 1987: 25), Khirbet Mekhayyat (Glueck 1935: 110–11, Site 239; Sailer and Bagatti 1949: 2, fig. 2) and Khirbet ʿAtarus (Musil 1907: 395–396, fig. 189). Outside of this region, sites with dry moats include Khirbet el-Medeinet South (ʿAliya) (Glueck 1934: 52; 98, pl. 12; Routledge 1995: 236 plan; 2000: 41, fig. 4; 48–49; Mattingly 1996: 355–57, fig. 3), Khirbet el-Medeinet North (Mukarradjeh) (Olavarri 1983: 166, fig. 1; J. M. Miller 1991: 71) and Khirbet el-ʿAlckuzeh (Glueck 1939: 61–62, 84, 90; J. M. Miller 1991: 158–60; Mattingly 1996: 363–64, fig. 9). However, since as yet none of these moats have been thoroughly investigated, their exact depth is unknown. Therefore, their potential relationship to the bedrock trench at Hesban can only be inferred in a general way. Since Herr made his original proposal (1979a), he himself has found a dry moat that is quite similar, in terms of its depth, to the bedrock trench at Tell Hesban at Tell el-ʿUmeiri, on its western side in Field B. Here the Iron Age inhabitants of the site reused the top 4.00 m of an almost 5.00 m deep and ca. 6.00 m wide dry moat originally dug in the Middle Bronze Age (Herr et al. 1991b: 159; Clark 1994: 142; 1997: 54, 63, fig. 4.9, 85, 87; Herr et al. 1994: 153; Herr 1998: 251–52, 254; 2000: 171; LaBianca et al. 1995: 102).

In another draft of his paper, Herr (1979b: 4) noted a further reason for rejecting the dry moat interpretation of the bedrock trench in that no trace of the trench was found on the western side of the mound, which means that it did not completely encircle the site. Shea (1979: 20–21), however, postulated that it did just that. Picking up on Herr’s suggestion that there was a subsidiary cut in the trench to the north, he extended this cut along an imaginary line on the western side of the tell just below the acropolis, and suggested that it might have been missed archaeologically in an unexcavated portion of Square C.10. While I agree that the dry moat interpretation has merit as the possible function of the bedrock trench, I believe that it is unlikely, indeed even unnecessary, for the trench to extend to the north on the western side or for that matter anywhere else on the mound.

Like most natural hills, the shape of tells appears to be the result of a combination of slope decline and parallel retreat (A. Rosen 1986: 27). According to slope evolution studies, at least one steep slope, often the one facing northwest, will usually develop. This occurs because it is exposed to the direct erosional agents of wind and rainfall. If it is flanked by a wadi, its steepness will be further accentuated by the removal of erosional debris at its base. The result is a phenomenon known as parallel retreat, where there is equal weathering along the entire face of the slope. A low, more gentle slope will develop on the other side of the mound where the rain strikes the surface obliquely and thus produces less vegetation. In other words, this side of the mound will erode through the process of slope decline caused by soil creep from its upper to lower portions (i.e., declining in height and lengthening out; A. Rosen 1986: 29, 31–33).

Irrespective of the accumulated sediments of cultural material which developed later, the first inhabitants of Tell Hesban evidently settled on a mound which had the same basic shape as is found at present. This is because Hesban is not a true tell (Geraty 1983: 247), but rather a natural hill formed on the basis of geological activities. Conforming to the model described above, geomorphologically speaking, a cross-section of Tell Hesban would look asymmetrical, with relatively steep slopes on three sides and a gentle slope on the other. The large gradually sloping shelf, upon which the acropolis sits in its center, drops rapidly on all sides of the mound except the southwest, which consists of a long slope. Contributing to the steepness of the other slopes of the mound are the Wadis el-Marbat and Majar flanking its east and west sides respectively (Boraas and Horn 1969a: 97–98; Younker 1994b: 55). Thus, the mound, even to its earliest inhabitants, would seem to have been defensible on all sides except the south. To the extent that it has been excavated, it is on this southern vulnerable side of the mound where the bedrock trench was found. The later Hellenistic (Sauer 1975a: 148; 1976: 54; 1978: 46; 1994: 250) or Early Roman (Mitchel 1992: 51–55) defense wall (B.1:17 = B.2:62), which ran roughly parallel but slightly south of the bedrock trench, is evidence that even later inhabitants saw a need for additional defense at this side of the tell.

Both Clark (1994: 141) and Hen (1997b: 15) have noted that it is likely that the moat at Tell el-ʿUmeiri probably existed only on its vulnerable western side of the tell. This seems to have been the case with all of the other contemporaneous dry moats mentioned above as well. Although they occur at different directions of their respective tells, each of these moats has been found only on its one gently sloping side. It would seem then that these tells also exhibit the same asymmetrical geomorphology described above. The difference in the direction of their gently sloping side, which necessitated the construction of a dry moat on that same slope in each case, is due to the complex topography of the region, impacted by locally altered wind patterns among the hills and valleys as well as the direction of flow of the deeply incised wadis (A. Rosen 1986: 31).

It would seem that a moat would be a necessity at Tell Hesban. At this site the gently sloping side of the tell is on the south-southwest. The bedrock trench was found in that area and thus conforms to the pattern of dry moat placement seen at other sites. The one weakness of this argument is that the moat at Tell Hesban is rather high up on the tell instead of at its base.

It should also be noted that the moats at the sites previously referenced appear to have been much wider (6.00 m +) than the bedrock trench at Hesban and to have had walls in connection with them. Although the 2.00–2.50 m width of this feature is certainly not as impressive as the dry moats found at these other sites, it nevertheless could possibly have served a defensive function as a deterrent against military attack, especially in combination with its 4.00 m depth. Its narrow width might reflect the limited manpower of Iron Age I Tell Hesban. Another possibility is that what has been found represents a moat that was never finished (Herr 1979a: 9; Shea 1979: 21).

It is also true that no walls have been found in connection with this trench. While there was a large amount of rock tumble in the western part of the trench (in Square B.3), which perhaps might have once been part of a defense wall or some other structure near it, there is no way of knowing for sure if that was the case. Since very little remains of this stratum, one could easily over- or underestimate the value of that which was not found. Nevertheless, unlike these other sites with dry moats, which were shorter lived, Hesban was occupied almost continuously up to modern times, with ongoing removal and robbing of earlier occupational features. Thus, the possibility exists that there originally was a wall or that one was intended, but never built before the trench went out of use. Further, it should also be pointed out that if such a wall did exist, the evidence indicates that it was not placed around the periphery of the mound, as the site was settled only on the Acropolis and its upper slopes at this time. Hesban is larger than the above-mentioned sites, and its Iron Age I inhabitants were unable to occupy all of its available space, a situation roughly analogous to Iron Age I and early Iron Age II Hazor (Yadin et al. 1989: 165–66; Ben-Tor 1995: 65–66), which also had a dry moat (Yadin et al. 1989: 53).

These same factors (the large size of the mound and the restricted area of settlement) may also account for the placement of the moat in a location higher up, on one of the shelves of the mound, rather than at its base as is typical of the other dry moats in the region. Though designed to deal with sherd distribution, the tell formation model of Portugali (1982: 171–72, fig. 1; cf. A. Rosen 1986: 47, fig. 14) may help to illustrate the point. Most of the above-mentioned sites with dry moats appear to be sealed structures and would seem to lend themselves to dry moat placement at the base of the tell. Both ʿUmeiri and Hesban are shelved structures although the location of the dry moat at ʿUmeiri is also at the base of the tell. This was necessary because the vulnerable side of the tell leading up to the acropolis, where the Iron Age settlement was located, is joined to a saddle connecting to a nearby ridge (Clark 1994: 140). The shelves, however, are located on the steep sides of the tell. At Hesban, on the other hand, the acropolis is located in the center of the mound with one of the shelves on its weak side. It is on that shelf that the bedrock trench is located. The settlement, restricted basically to the acropolis, was thus a considerable distance from the base of the mound, making the location of a dry moat in that position an impractical solution. Regardless of its placement on the shelf, the bedrock trench or moat appears to have cut off the settlement from its approach on the southwest and thus functioned in the same manner as if it had been located at its base.

With the exception of an intrusive Early Roman pit (D.4:117) which contained loose rock, the bedrock trench was completely filled with debris from this stratum. The ceramic material was mixed Iron Age IA and IB and includes collared-rim store jars, incurved bowls, and strainer-spouted jugs (Sauer 1986: 10-11, fig. 11; 1994: 235, 236 pl.; cf. chapter 3, figs. 3.2.1-8; 3.3.2, 16 above). As in the previous stratum, there are also “Manassite” bowls (fig. 3.3.3, 5-6, cf. fig. 3.1.11) and small carinated bowls (fig. 3.3.7-9; cf. fig. 3.1.14). Both the debris and the ceramic remains were homogeneous, containing no surfaces, wind, and water-sorted soil layers or flat-lying pottery, which indicates a rather quick filling process (Herr 1979a: 10). This, along with numerous ash layers (see above and Sauer 1976: 62 on B.3:94) and one human bone (D.4:142 cf. Sauer 1978: 48, n. 18), would suggest the destruction of the site (Herr 1979a: 10-11, contra Sauer 1994: 237). Thus, irrespective of whether the trench was finished or not and whether or not there were accompanying walls, the site would seem to have been attacked and destroyed rather early in its existence.

It is impossible to know for sure the identity of those who attacked and destroyed Hesban. A very tentative suggestion based, as all proposed perpetrators of ancient destructions are, on textual evidence is that of the desert peoples. The Midianites, Amalekites, and other tribes from the desert to the east plundered both eastern (Judg 8:4-11) and western Palestine, sometimes on an annual basis (Judg 6:1-3) during Iron Age I and there is ample analogy throughout the history of the Middle East of this kind of activity. It is possible, therefore, that Hesban was destroyed by some group of nomadic raiders as they moved about from place to place plundering the settled population. Another possibility is that it was the Ammonites (or other nearby neighbors) who began a short period of military expansion about this time (Judg 10:7-12:7).

As we have seen, the tell was naturally defensible and if the bedrock trench was indeed a dry moat (whether just underway or completed), fortification seems to have been at least attempted. Further, the coordination of the labor involved in digging the bedrock trench would seem to have necessitated a socioeconomic sophistication beyond the means of the small village of the previous stratum. Tell Hesban is located at the crossroads of the main north-south (or King’s Highway) and the so-called Way of Beth-Jeshimoth (Josh 12:3), the precursors to the Via Nova Traiana and the Esbus-Livias Road (Waterhouse and Ibach 1975: 217; Ibach 1994: 65). Assuming that this advantage was exploited, something on the scale of a large village could easily be posited. While London (1992: 72) is surely correct that a full-blown central place theory is not applicable for ancient Palestine (eastern as well as western), Dever’s suggestion (within a tentative typology of tells) that Tell Hesban was a small (border) town (1996: 39, table 1; cf. Younker 1994b: 59) might be a little premature for this early in the history of the settlement. We therefore suggest that the site was a large village of Reubenites (cf. above p. 125 and Num 32:37; Josh 13:15, 17), which contained some sort of shrine (cf. the chalices, fig. 3.3.10-11), and perhaps with smaller satellite settlements (Josh 13:17) at this time.

The steepness of most of the slopes of Tell Hesban, as already mentioned, gives it a natural defensive position. Recent studies on visibility and settlement strategy indicate that the viewshed of Tell Hesban contained 27 percent of its 10 km surrounding region (Christopherson and Guertin 1996: 9). It is possible that a number of smaller sites served as watchtowers in its immediate vicinity and would have acted as an early warning system.

Though one cannot say much from the few remains that have been located from this stratum, it would nevertheless appear that there was perhaps a bit of growth in prosperity from the previous stratum. This supposition is supported by a limestone (possibly mizzi yahudi) door socket that was found in locus D.4:142, which may suggest the presence of a public building (Reich 1992: 2, 13). Further, the two fish bones (one stone bass, Polyprion americanus and one sea bream, Sparus auratus) that were found in the soil layers (D.4:135 and 138) of this stratum would seem to have been “imported” from the Mediterranean Sea (von den Driesch and Boessneck 1995: 100; Lepiksaar 1995: 182-88), which confirms trade connections with entities in Cisjordan.

Hesban’s location at the junction of three topographical zones (the highlands, the Madaba Plains [the Mishor], and the mountains of Abarim) (Younker 1994b: 56) provided it with an ample food supply. Carbonized seeds of cultivated plants from the debris layers of this stratum included wheat (Triticum aestivum), barley (Hordeum vulgare), lentils (Lens sp.), grapes (Vitis vinifera), figs (?), and peas (Pisum sp.). Seeds from uncultivated plants included rye grass or tares (Lolium temulentum) and an unidentified wild grass (Gramineae), both probably used as fodder for animals (Crawford 1986: 80-90). Bones of domesticated animals used by the residents of the tell during this stratum included the better represented cattle, sheep, goats, and pig, with smaller numbers of camel, horse, donkey, and chicken, with only the last normally used as food. Represented wild species include fish, occasional imports from the Mediterranean coast, and gazelle.

It would appear from the above that the subsistence economy of Tell Hesban during Stratum 20 was a mixed agro-pastoral one, heavily dependent on grain production (cf. also the mortar for grain preparation found in Locus B.3:93) and the products from sheep and goats. The central role of cereals in the diet also seems to throw light on the high proportion of cattle (22.33 percent) reflected in the faunal assemblage (cf. Table 5.2). They were evidently used as draft animals for cereal cultivation (B. Rosen 1994: 343), though possibly also for food production (LaBianca 1990: 146). These subsistence strategies were occasionally supplemented with wild fish and game. A number of spindle whorls and pottery discs, which may have been blanks for other spindle whorls, are evidence for the continuation of the cottage industry begun already in the previous stratum. Two other seed species found at the tell suggest the possible sophistication of its occupants. Though their presence does not necessarily mean they were used in this way, knotweed (Polygonum sp.) can be used medicinally to make poultices (Crawford 1986: 80) and heliotrope (Heliotropium sp.) can be cultivated for ornamental purposes (Gilliland 1986: 131).

- Site Plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2)

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 2 - Areas of excavations

at Tell Heshbon from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Areas of excavations (Bert de Vries, Calvin College; Paul Ray, Jr., Andrews University; Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University; and Marvin Bowen, Andrews University).

Walker and LaBianca (2003)

- Site Plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2)

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 2 - Areas of excavations

at Tell Heshbon from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Areas of excavations (Bert de Vries, Calvin College; Paul Ray, Jr., Andrews University; Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University; and Marvin Bowen, Andrews University).

Walker and LaBianca (2003)

In most of the excavated areas at the site, the evidence for the destruction and/or abandonment of Stratum 15 had been removed by subsequent building activities (notably in Stratum 13). In Areas B and D some possible Stage A loci survived. In two cases, capstones sealed off store silos. Stratum 15/14 Capstone D.2:86 (pl. 2.19) sealed Silo D.2:77, with locus D.2:77A representing a small amount of pre-sealing debris. Capstone B.3:70 closed off Silo B.3:64. In Silo B.3:59, Stratum 14 fill-loci were preceded by one Stratum 15 rubble layer (B.3:63). In G.1 the store silo (or cistern) was filled up with Stratum 15 debris (G.1:48) and covered by tumble (G.1:42). Store Silo B.3:47 was filled up (loci B.3:50 = B.3:51 + B.3:52) in Stratum 15. In G.1, Wall G.1:41 was put out of use by Soil Layer G.1:35. Layer G.1:34, which is possibly a dung layer, lies under Stratum 13 Rubble Layer G.1:30; it may or may not belong to Stratum 15.

Given what we know from the written sources, along with the facts of the site's location, it is possible to make some synthesizing suggestions even though the remains for Stratum 15 are meager. We do know a number of key things: (1) the summit of the tell was stripped to bedrock, at the least over the entire extent in which Area A was excavated to bedrock, and probably a much larger expanse; (2) the summit was surrounded by a massive fortification wall nearly 2 m thick, which may well have from the beginning followed that outline traced by the Heshbon Expedition’s surveyor/architects (fig. 2.3); (3) at some distance from the so-called “perimeter” wall itself, a succession of soil layers and/or surfaces with a few walls have been excavated, namely in Probes G.1 and G.12 on the southeast and south sides of the summit mound, respectively.

From this fragmentary information, I would conjecture that Hellenistic Heshbon began its life as a type of border fort. The military nature of early Esbus (Strata 15–14) is certainly underlined, in relative terms, by the occurrence of objects of a military nature (armor scales, slingstones, maceheads, arrowheads). These have been tabulated by raw count and percent of total objects from each stratum (table 2.4). The highest percentages of such objects occur precisely in Stratum 15.

Interestingly enough, one of the highest concentrations of slingstones on the site came from Stratum 15 loci (Kotter 1979: 8). This datum must not be overinterpreted, since I do not believe it is known when these missiles were first made and used, but it is possible that this higher number does in fact reflect the predominantly military nature of the settlement (as well as the military activity in the area in that time period).

The construction of such an installation would have motivated the enormous debris-hauling operation which resulted in an estimated 2,000 m³ of Iron Age remains being dumped into the Area B reservoir. This would have resulted in trustworthy fortification-wall foundations based on bedrock, as well as setting up a clear field-of-fire on the southern approach to the summit, one of the most accessible routes to the top of the tell. In addition it should be noted that a garrison would probably not require more water than could be stored in cisterns available on the summit of the mound itself (i.e., inside the confines of the perimeter wall).

Such a major building operation might also explain the east-west bedrock cut in Area D, Squares D.1 and D.2, which has been a matter of discussion in the preliminary reports (Herr 1978a: 110–112). It is possible that this bedrock cutting represents quarrying activity to supply stone for the building operations of Stratum 15. However, earlier Iron Age quarrying might provide a better explanation, given the fact that surviving Late Hellenistic architecture uses field stone or semi-dressed stone exclusively (compare the dressed stones in the Stratum 17 header-stretcher reservoir wall in B.2; Boraas and Geraty 1976: pl. 4:A).

After a period of time (or maybe almost from the beginning of Stratum 15) a small population sprang up around the military post, at least on its south slopes. Further excavation to the north and west of the summit enclosure might answer the question of Hellenistic period occupation elsewhere around the top of the tell outside the perimeter wall. This occupation entailed at least a little architecture as well on the western slope (C.7:44 = C.3:26), though the nature and purpose of such architecture is not recoverable. As suggested above, the reuse of store silos in Stratum 15 may not of itself imply non-military occupation of the site. But the presence of a relatively large number of spinning and weaving implements certainly argues for more normal domestic occupation—at least later in the period represented by Stratum 15.

The transition to Stratum 14 may be characterized as a smooth one, although the evidence is slim. There is currently no evidence of a destroying conflagration at the end of Stratum 15. In fact, I do not believe it is likely that we shall know whether Stratum 15 Heshbon was simply abandoned, or destroyed by natural or human events. Stratigraphy from Square A.11 would point strongly toward a gradual transition from Stratum 15 to Stratum 14. There Stratum 14 Floor A.11:45 follows Stratum 15 Floor A.11:47 and Fill Layer A.11:46. In Square D.2, Stratum 15/14 Soil and Occupation Surfaces D.2:84, D.2:83, D.2:82, D.2:76, D.2:74, D.2:92, north of Wall D.2:64, and Fill Layers D.2:108 and D.2:109 south of it, are succeeded by Stratum 14 Soil Surface D.2:67 (Wall D.2:26 probably formed the north wall of this room). Finally, in Square B.4, where in Pool B.4:265 two Stratum 15 Layers (B.4:249 and B.4:229) are followed by what appears to be a Stratum 14 floor (B.4:228).

- Site Plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2)

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 2 - Areas of excavations

at Tell Heshbon from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Areas of excavations (Bert de Vries, Calvin College; Paul Ray, Jr., Andrews University; Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University; and Marvin Bowen, Andrews University).

Walker and LaBianca (2003)

- Site Plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2)

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 2 - Areas of excavations

at Tell Heshbon from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Areas of excavations (Bert de Vries, Calvin College; Paul Ray, Jr., Andrews University; Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University; and Marvin Bowen, Andrews University).

Walker and LaBianca (2003)

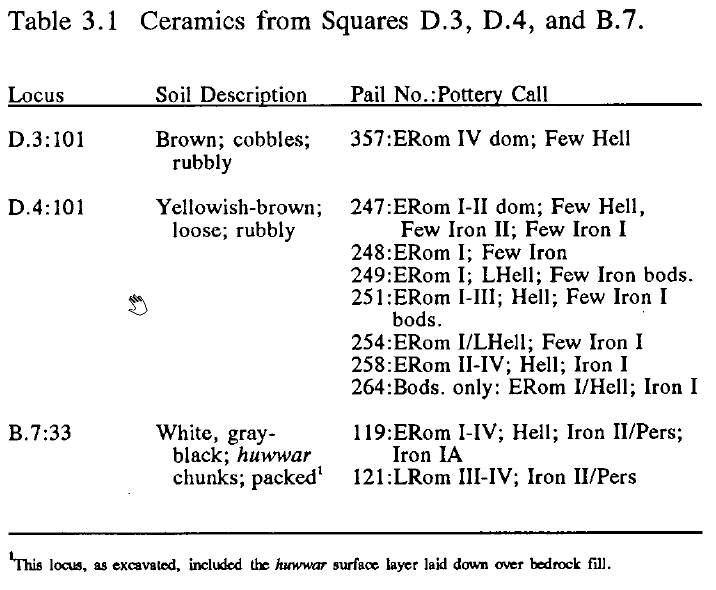

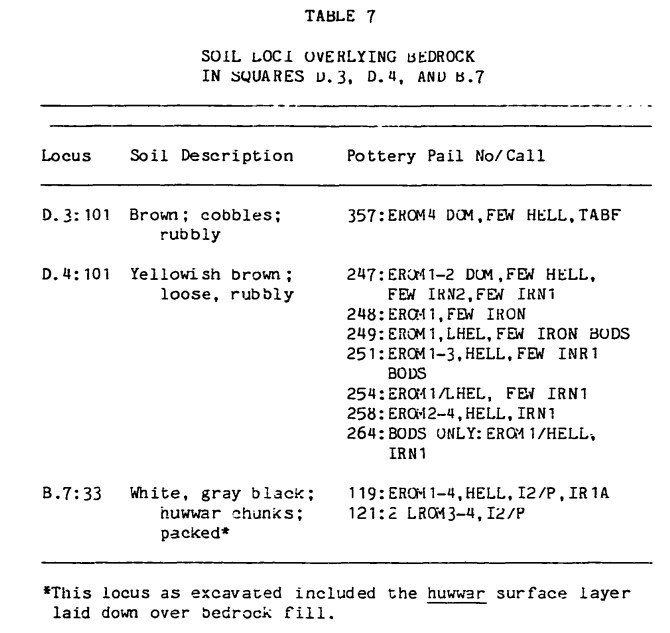

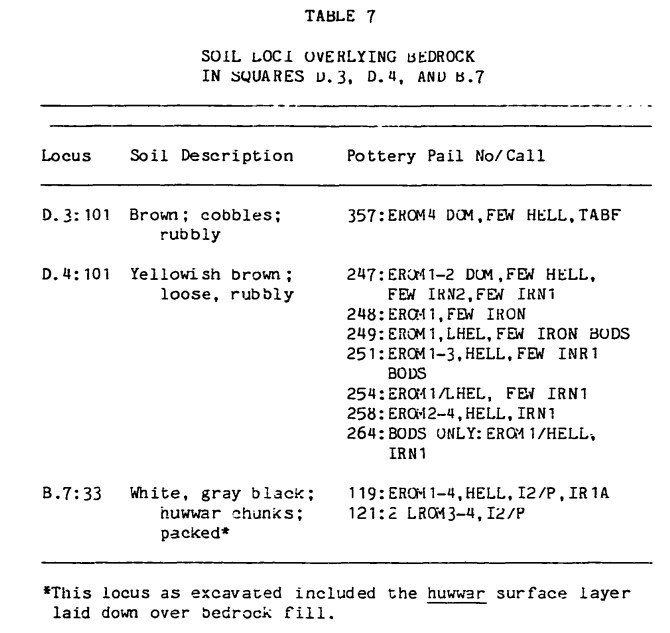

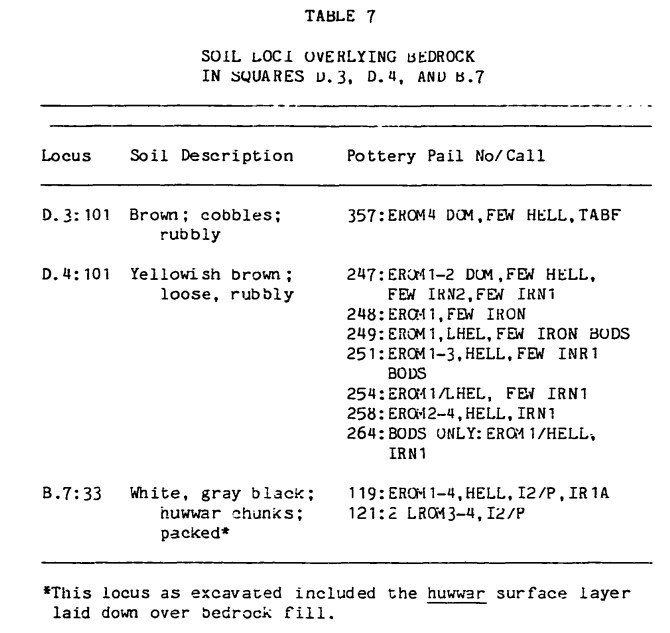

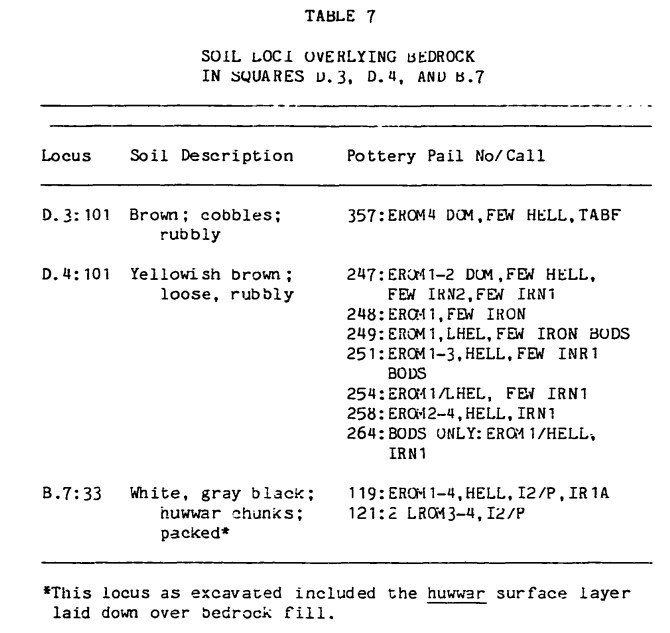

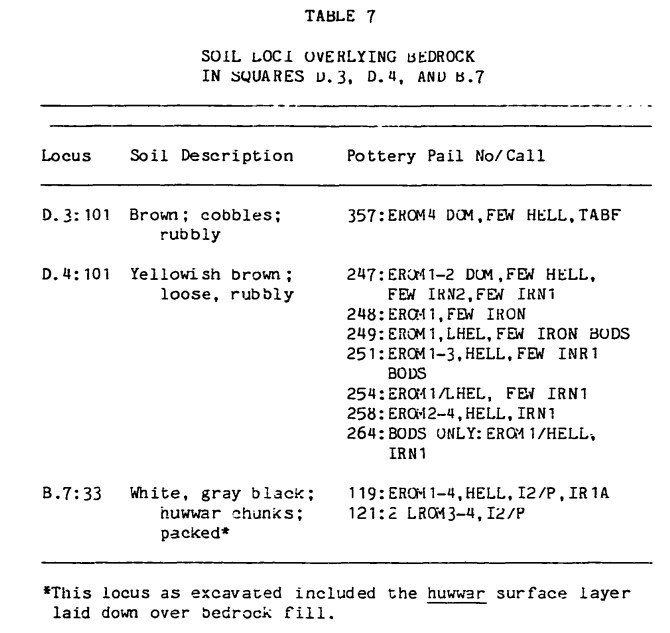

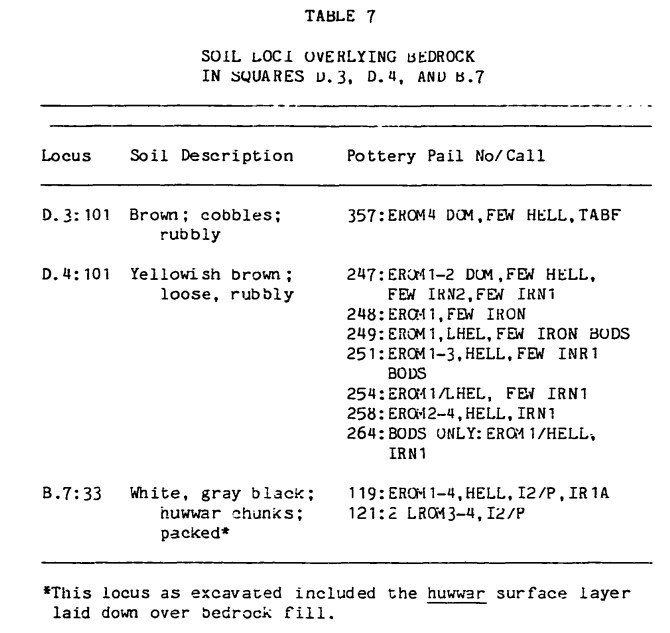

- Table 7 from Mitchel (1980)

Table 7

Abbreviations

- DOM = Dominant

- TABF = Tabun Fragment

- BOD = Body Sherd

- IRN1 = Iron Age I

- IRN1A = Iron Age IA

- IRN2 = Iron Age II

- I2/P = Iron Age II/Persian

- HELL = Hellenistic

- LHEL = Late Hellenistic

- EROM = Early Roman

- Iron Age I - 1200-1000 BCE*

- Iron Age IA - 1200-1150 BCE*

- Iron Age II - 1000-586 BCE*

- Iron Age II/Persian - 1000*-332 BCE

- Hellenistic - 332-63 BCE

- Late Hellenistic - 198-63 BCE

- Early Roman I - 63-37 BCE

- Early Roman II - 37-4 BCE

- Early Roman III - 4 BCE-73 CE

- Early Roman IV - 73-135 CE

Mitchel (1980)

Evidence for Stratum 14 occurs virtually all over the tell, either in primary or secondary contexts. Most of the Stratum 14 remains in Area C appear to be secondary deposits, probably the result of Stratum 13 clearing operations on the tell summit. For the same reason, Area A has few connected remnants of Stratum 14 occupation. In Area D most of the loci of Stratum 14 come from beneath the bedrock fill of Stratum 13, though Square D.2 does have a good series of Stratum 14 surfaces (or floors). The same picture tends to hold for Area B, with the exception of some occupation evidence over Stratum 15 reservoir fill in Square B.4, and to a lesser extent in Square B.2.

It appears that the Stratum 14 occupants of Tell Hesban made more extensive use of underground living and/or storage facilities than did succeeding occupants (until the late Islamic period). The apparent change in dwelling preference following this period may not be due simply to the collapse at the end of Stratum 14 of many such bedrock installations, especially in Areas B and D. It may also signal a shift in dwelling patterns away from underground homes such as the shift suggested to be desirable by a Herodian king in probable reference to the Trachonitis farther north (Avi-Yonah 1977: 91).

As suggested in the discussion of Stratum 15, the transition into Stratum 14 at Tell Hesban was to all appearances a smooth, perhaps gradual, one. The end of the stratum, however, was of quite a different nature. Over a wide area, indicated by the stretch from northern Square D.3 into southern Square B.4, some event caused the majority of caves in bedrock to collapse. This is noted by bedrock surface channels presumably for directing run-off water into storage facilities, which are now totally disrupted and in many cases rest 10–20 percent from the horizontal; by caves with carefully cut steps leading down into them whose entrances are fully or largely collapsed and no longer usable; by passages from caves that excavators could enter which obviously were once linked to caves which no longer exist, or are so low-ceilinged or clogged with debris as to make their use highly unlikely at least as they stand now.

Only one agency presents itself as adequate to account for this widespread bedrock disruption: earthquake. After presenting the field evidence for Stratum 14, we shall return to the question of a date for such an event. But whatever or whenever this event, the break between Strata 14 and 13 is clear and distinct in Areas A and D, where loose fill was used by the builders of Stratum 13 Esbus to level out the jumble of broken-up bedrock, and totally new buildings were erected.

Though there are a number of loci which witness to the destruction of Stratum 14, the clearest probably being a sequence in the northeast corner of Square D.2 (loci D.2:79, D.2:78, D.2:70, D.2:59 [pl. 3.22]), the major evidence for the termination of this stratum resides in the massive bedrock collapse in Areas B and D (as has already been described). It is probable that a related set of factors makes this so. First, the bedrock in that specific sector of the site appears to have been softer (or at least to have had softer strata) and was thus naturally more subject to the natural production of karsts. This very softness would invite artificial (i.e., human) expansion of these underground caves and passages, which leads to the second factor. Not only would the bedrock be naturally less resistant to seismic shock, the resistance would be severely reduced by the very fact of its being honey-combed with chambers and passages. Alternatively, the resistance of the bedrock layers and/or the apparent reduced amount of underground building activity could explain the absence of collapsed Stratum 14 underground facilities and the continued use of these cave systems which survived in Areas A and C, for example the caves in Squares A.1 and C.7.

The earthquake which destroyed bedrock installations and closed out Stratum 14 occupation at Tell Hesban has been identified as possibly the earthquake of 31 B.C. (Sauer 1973a: 50; cf. Kallner-Amiran 1950, 1951). While this date is not impossible, given the evidence for destruction at Khirbet Qumran about 35 km east-southeast, the 31 B.C. earthquake was centered more in Galilee (Kallner-Amiran 1950: 225). In my judgment the observed destruction at the end of Stratum 14 at Tell Hesban seems more severe than that indicated for Khirbet Qumran in 31 B.C.

More troublesome to the 31 B.C. date, however, is the evidence of certain remains at the site. For one, a late coin was found in the fill of Silo D.3:57 (Object No. 1740, D.3:57C). The coin is of Aretas IV (9 B.C.–A.D. 40) and comes from the last (uppermost) layer of fill in the silo (subsidiary section drawing of balk 74:71a, fig. 3.8). This evidence by itself would suggest a date later than 31 B.C. for the destructive earthquake of Stratum 14 Stage A. (Though in fairness it must be admitted that the coins recovered at Tell Hesban have correlated poorly with associated pottery. More on this coin, and Tell Hesban coins in general, may be found in volume 12 of this series.) But the point must be argued further.

The filling of the silos, caves, and other broken-up bedrock installations at the end of the Early Roman period was apparently carried out nearly immediately after the earthquake occurred. This conclusion is based on the absence of evidence for extended exposure before filling (silt, water-laid deposits, etc.), which in fact suggests that maybe not even one winter’s rain can be accounted for between the earthquake and the Stratum 13 filling operation. If this conclusion is correct, then the Aretas IV coin had to have been introduced into the Silo D.3:57 fill soon after the earthquake. Consequently, this could not have been earlier than 9 B.C.

Table 3.1 provides a systematic presentation of what I consider to be the critical ceramic evidence from loci in three adjacent squares: D.3, D.4, and B.7. The nature of the pottery preserved on the soft, deep fills overlying collapsed bedrock is also of significant importance to my argument in favor of the A.D. 130 earthquake as responsible for the final demise of underground (bedrock) installations in Areas B and D. The dates of the latest pottery uniformly carry us well beyond the date of the earthquake which damaged Khirbet Qumran, down, in fact, closer to the end of the first century A.D. or the beginning of the second century A.D.

In addition to these three fill loci, Soil Layer D.4:118A (pl. 3.23), inside collapsed Cave D.4:116 (+ D.4:118), yielded Early Roman I–III sherds, as well as two Late Roman I sherds (Square D.4 pottery pails 265, 266). Contamination of these latter samples is possible, but not likely. I dug the locus myself, and am reasonably sure of its provenance.

Obviously, this post-31 B.C. pottery could have been deposited much later than 31 B.C., closer, say, to the early second century A.D., but the evidence seems to be against such a view. I personally excavated much of locus D.4:101 (Stratum 13). It was a relatively homogeneous, unstratified fill of loose soil that gave all the appearances of rapid deposition in one operation. From field descriptions of the apparently parallel loci in Squares D.3 and B.7, I would judge them to be roughly equivalent and subject to the same interpretation and date. And I repeat, the evidence for extended exposure to the elements (and a concomitant slow, stratified deposition) was either missed in excavation, not properly recorded, or did not exist.

This case is surely not incontrovertible, but seems to me to carry the weight of the evidence which was excavated at Tell Hesban. Furthermore, the earthquake of A.D. 130, of those from this general time-period listed in Amiran’s earthquake catalogue, could better account for the massive destruction evidenced at Early Roman Tell Hesban, given the widespread evidence for this earthquake in Transjordan, from Jerash to Petra (Fritsch and Ben-Dor 1961: 55; Stinespring 1934: 15). In Gerasa (Jerash) an arch dedicated to Hadrian fell in the 192d year of the era of Gerasa (October 1, A.D. 129 to October 1, A.D. 130). The incised letters of the inscription on the north (inner) face had apparently been newly painted—perhaps newly finished—when the arch collapsed in an earthquake (Stinespring 1935: 4). It is possible this earthquake can be dated to the spring or summer of A.D. 130. Hadrian apparently made his trip in early summer of A.D. 130 (Weber 1936). Though there is yet some question about the precise date, at Petra there is evidence of a destructive earthquake probably to be dated in the early decades of the second century. Russell actually prefers a date of ca. A.D. 114 (Russell 1980b).

The building projects of Stratum 13 would have been begun soon after the earthquake damage had occurred, the first operation being the levelling out of broken-up bedrock surfaces.

Additional loci attributed to Stage A are: A.1:27; A.5:80; B.3:48; B.4:166, B.4:186, B.4:254, B.4:283E, B.4:283F; C.1:125; C.2:28, C.2:39. Loci which are assigned to Stratum 14, but do not materially contribute to a threefold understanding of the stratigraphy: A.2:46; A.3:51; A.8:38; B.2:106; B.3:56, B.3:57; B.4:152, B.4:204, B.4:221, B.4:233, B.4:255, B.4:263, B.4:283G; C.1:18, C.1:27, C.1:38, C.1:45, C.1:55, C.1:58, C.1:60, C.1:65, C.1:68, C.1:69, C.1:75, C.1:76–80, C.1:82, C.1:83, C.1:85–89, C.1:92, C.1:93, C.1:103–105, C.1:113, C.1:115, C.1:117; C.2:27, C.2:32, C.2:35, C.2:37, C.2:69–71; C.3:31; C.5:52, C.5:86, C.5:102, C.5:105, C.5:107, C.5:109, C.5:110, C.5:112, C.5:117, C.5:119, C.5:129, C.5:131, C.5:150, C.5:168, C.5:178, C.5:179, C.5:213, C.5:227; C.7:69, C.7:73, C.7:76, C.7:79, C.7:107; C.9:57, C.9:59; D.1:51, D.1:92; D.3:107; G.1:46.

Mitchel (1980) identified a destruction layer in Stratum 14

which he attributed to an earthquake. Unfortunately, the destruction layer is not precisely dated. Using some assumptions,

Mitchel (1980) dated the

earthquake destruction to the 130 CE Eusebius Mystery Quake,

apparently unaware at the time that this earthquake account may be either

misdated as suggested by Russell (1985) or mislocated as

suggested by Ambraseys (2009).

Although Russell (1985) attributed the destruction layer

in Stratum 14 to the early 2nd century CE Incense Road Quake, a number of

earthquakes are possible candidates including the 31 BCE Josephus Quake.

Mitchel (1980:73) reports that,

over a wide area from northern square D.3 into southern square B.4, a majority of caves used for dwelling collapsed at the top of

Stratum 14 which could be noticed by:

bedrock surface channels, presumably for directing run-off water into storage facilities, which now are totally disrupted, and in many cases rest ten to twenty degrees from the horizontal; by caves with carefully cut steps leading down into them whose entrances are fully or largely collapsed and no longer usable; by passages from caves which can still be entered into formerly communicating caves which no longer exist, or are so low-ceilinged or clogged with debris as to make their use highly unlikely — at least as they stand now.Mitchel (1980:73) also noticed that new buildings constructed in Stratum 13 were leveled over a

jumble of broken-up bedrock. Mitchel (1980:95) reports that Areas B and D had the best evidence for the massive bedrock collapse - something he attributed to the "softer" strata in this area, more prone to karst features and thus easier to burrow into and develop underground dwelling structures. Mitchel (1980:96) reports discovery of a coin of Aretas IV (9 BC – 40 AD) in the fill of silo D.3:57 which he suggests was placed as part of reconstruction after the earthquake. Although Mitchel (1980:96) acknowledges that this suggests that the causitive earthquake was the 31 BCE Josephus Quake, Mitchel (1980:96) argued for a later earthquake based on the mistaken belief that the 31 BCE Josephus Quake had an epicenter in the Galilee. Paleoseismic evidence from the Dead Sea, however, indicates that the 31 BCE Josephus Quake had an epicenter in the vicinity of the Dead Sea relatively close to Tell Hesban. Mitchel (1980:96-98)'s argument follows:

The filling of the silos, caves, and other broken—up bedrock installations at the end of the Early Roman period was apparently carried out nearly immediately after the earthquake occurred. This conclusion is based on the absence of evidence for extended exposure before filling (silt, water—laid deposits, etc.), which in fact suggests that maybe not even one winter's rain can be accounted for between the earthquake and the Stratum 13 filling operation. If this conclusion is correct, then the Aretas IV coin had to have been introduced into silo D.3:57 fill soon after the earthquake. which consequently could not have been earlier than 9 B.C.Mitchel (1980:100)'s 130 CE date for the causitive earthquake rests on the assumption that the "fills" were deposited soon after bedrock collapse. If one discards this assumption, numismatic evidence and ceramic evidence suggests that the "fill" was deposited over a longer period of time - perhaps even 200+ years - and the causitive earthquake was earlier. Unfortunately, it appears that the terminus ante quem for the bedrock collapse event is not well constrained. The terminus post quem appears to depend on the date for lower levels of Stratum 14 which seems to have been difficult to date precisely and underlying Stratum 15 which Mitchel (1980:21) characterized as chronologically difficult.

The nature of the pottery preserved on the soft, deep fills overlying collapsed bedrock is also of significant importance to my argument in favor of the A.D. 130 earthquake as responsible for the final demise of underground (bedrock) installations in Areas B and D. Table 7 provides a systematic presentation of what I consider to be the critical ceramic evidence from loci in three adjacent squares, D.3, D.4, and B.7. The dates of the latest pottery uniformly carry us well beyond the date of the earthquake which damaged Qumran, down, in fact, closer to the end of the 1st century A.D. or the beginning of the 2nd.

In addition to these three fill loci, soil layer D.4:118A (inside collapsed cave D.4:116 + D.4:118) yielded Early Roman I-III sherds, as well as two Late Roman I sherds (Square D.4 pottery pails 265, 266). Contamination of these latter samples is possible, but not likely. I dug the locus myself.

Obviously, this post-31 B.C. pottery could have been deposited much later than 31 B.C.. closer, say, to the early 2nd century A.D., but the evidence seems to be against such a view. I personally excavated much of locus D.4:101 (Stratum 13). It was a relatively homogeneous, unstratified fill of loose soil that gave all the appearances of rapid deposition in one operation. From field descriptions of the apparently parallel loci in Squares D.3 and B.7. I would judge them to be roughly equivalent and subject to the same interpretation and date. And I repeat, the evidence for extended exposure to the elements (and a concomitant slow, stratified deposition) was either missed in excavation, not properly recorded, or did not exist.

This case is surely not incontrovertible but seems to me to carry the weight of the evidence which was excavated at Tell Hesban.

Mitchel (1980) identified a destruction layer in Stratum 14

which he attributed to an earthquake. Unfortunately, the

destruction layer is not precisely dated. Using some

assumptions,

Mitchel (1980) dated the earthquake destruction to the

~130 CE Eusebius Mystery Quake, apparently unaware at the time that

this account may be misdated, as suggested by

Russell (1985), or mislocated, as argued by

Ambraseys (2009). Although

Russell (1985) attributed the destruction in Stratum 14 to the

early 2nd century CE

Incense Road Quake, other candidates include the

31 BCE Josephus Quake.

Mitchel (1980:73) reports that many caves used for dwelling

collapsed at the top of Stratum 14 in areas from northern square

D.3 into southern square B.4. This was evidenced by

"bedrock surface channels, presumably for directing run-off

water into storage facilities, which now are totally disrupted,

and in many cases rest ten to twenty degrees from the

horizontal; by caves with carefully cut steps leading down into

them whose entrances are fully or largely collapsed and no

longer usable; by passages from caves which can still be

entered into formerly communicating caves which no longer

exist, or are so low-ceilinged or clogged with debris as to

make their use highly unlikely — at least as they stand now."

Mitchel (1980:73) also noted that Stratum 13 buildings were

constructed over a jumble of broken-up bedrock

.

Mitchel (1980:95) reported that Areas B and D showed the

best evidence of massive bedrock collapse, which he attributed

to softer strata prone to karst features and underground

excavation.

Mitchel (1980:96) noted the discovery of a coin of

Aretas IV

(9 BC – 40 AD) in the fill of silo D.3:57, suggesting it was

placed during post-earthquake reconstruction. Although this

might suggest the

31 BCE Josephus Quake as the cause,

Mitchel (1980:96) argued for a later quake

based on the mistaken belief that the

31 BCE Josephus Quake had an epicenter in Galilee. In fact,

Dead Sea paleoseismic evidence places the epicenter near Tell

Hesban.

Mitchel (1980:96–98) argued that "the filling of the silos,

caves, and other broken-up bedrock installations at the end of

the Early Roman period was apparently carried out nearly

immediately after the earthquake occurred." He based this on

"the absence of evidence for extended exposure before filling

(silt, water-laid deposits, etc.), which in fact suggests that

maybe not even one winter's rain can be accounted for between

the earthquake and the Stratum 13 filling operation." He

concluded that the Aretas IV coin had to have been placed in

silo D.3:57 fill soon after the earthquake, "which consequently

could not have been earlier than 9 B.C."

He added that "the nature of the pottery preserved on the soft,

deep fills overlying collapsed bedrock is also of significant

importance to my argument in favor of the A.D. 130 earthquake as

responsible for the final demise of underground (bedrock)

installations in Areas B and D." He pointed to Table 7, which

systematically presents "the critical ceramic evidence from

loci in three adjacent squares, D.3, D.4, and B.7." The latest

pottery from these loci "uniformly carry us well beyond the

date of the earthquake which damaged Qumran, down, in fact,

closer to the end of the 1st century A.D. or the beginning of

the 2nd."

He noted that soil layer D.4:118A, inside the collapsed cave

D.4:116 + D.4:118, yielded Early Roman I–III sherds as well as

two Late Roman I sherds. "Contamination of these latter samples

is possible, but not likely. I dug the locus myself."

He continued, "Obviously, this post–31 B.C. pottery could have

been deposited much later than 31 B.C., closer, say, to the

early 2nd century A.D., but the evidence seems to be against

such a view." He described locus D.4:101 (Stratum 13) as "a

relatively homogeneous, unstratified fill of loose soil that

gave all the appearances of rapid deposition in one operation."

He judged the parallel loci in squares D.3 and B.7 to be

"roughly equivalent and subject to the same interpretation and

date." He concluded, "this case is surely not incontrovertible

but seems to me to carry the weight of the evidence which was

excavated at Tell Hesban."

Mitchel (1980:100)'s date of 130 CE for the earthquake rests

on the assumption that the fills were deposited soon after the

collapse. If this is incorrect, ceramic and numismatic evidence

might suggest a much earlier earthquake, possibly 200+ years

before. The terminus ante quem for collapse is poorly

constrained, and the terminus post quem depends on the date of

Stratum 14, which is itself difficult to date, as

Mitchel (1980:21) had already described Stratum 15 as

chronologically problematic.

- Site Plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2)

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 2 - Areas of excavations

at Tell Heshbon from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Areas of excavations (Bert de Vries, Calvin College; Paul Ray, Jr., Andrews University; Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University; and Marvin Bowen, Andrews University).

Walker and LaBianca (2003)

- Site Plan with excavation

areas from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2)

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Heshbon: map of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 2) - Fig. 2 - Areas of excavations

at Tell Heshbon from Walker and LaBianca (2003)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Areas of excavations (Bert de Vries, Calvin College; Paul Ray, Jr., Andrews University; Ernest Cowles, Oklahoma State University; and Marvin Bowen, Andrews University).

Walker and LaBianca (2003)

- Plate 25A - The Great Stairway

from Mitchel (1980)

Plate 25A

Plate 25A

East Margin of Monumental Stairway, D.3. View East

Mitchel (1980)

In Stratum 11, additions were made to the Roman structure (temple) on the acropolis and a magnificent stairway of monumental size replaced the Stratum 13-12 ramp as the south access route to the acropolis complex. At the foot of the stairway, an even more extensive plaza was laid, which covered that part of Room 3 (in Square D.3) not covered by the stairway. On the western slope of the tell, continued use of earlier buildings and walls is demonstrated by the accumulation of floors and soil layers over Stratum 12 remains.

The date for the beginning of Stratum 11 is somewhat arbitrary. The latest coin in Stratum 12 loci is one probably issued under Elagabalus (B.1:13; Object No. 2104) which would place it around A.D. 222 at latest, with the stratum closing out at some time after that. Since there is no clear stratigraphic break across the tell, the date of A.D. 284 was selected with respect to the beginning of the reign of Diocletian who began a reorganization of the empire of major proportions.