Mamshit/Mampsis

Aerial View of Mamshit

Aerial View of MamshitClick on Image to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Biblewalks.com

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Mamshit | Hebrew | ממשית |

| Kurnub | Modern Arabic | كورنوب |

| Kurnub | Nabatean ? | |

| Kurnub | Arabic | |

| Mampsis | Byzantine Greek | Μαμψις |

| Memphis | Ancient Greek | Μέμφις |

Mampsis was initially occupied at least as early as the 2nd century BCE when it was a station on a secondary part of the Incense Road (Avraham Negev in Stern et al, 1993). It appears on the Madaba Map as Μαμψις (Mampsis). It went into decline or was abandoned in the 7th century CE.

Kurnub (Mampsis) is in the central Negev desert, 40 km (25 mi.) southeast of Beersheba at the junction of the Jerusalem-Hebron-AHa (Elath) road and the road to Arabah and Edom (map reference 156.046). In antiquity there were probably also roads that connected Mampsis with Gaza and Oboda. Medieval Arabic lexicons explain the name Kurnub - the Arabic name by which the site is known today - as a kind of food made of palm dates and milk. Some of them suggest that the noun and verb may have come from the Nabatean language. R. Hartman's suggestion to identify Kurnub with Mampsis is generally accepted.

Mampsis is first mentioned in the mid-second century CE by Ptolemy (Geog. V, 16, 10), where Μαψ (other readings Μαψις, Μαψα) and 'Ελουσα [Elusa] are listed with the cities in ldumea. The city is later mentioned in Late Roman and Byzantine sources. Eusebius (Onom. 8, 8) relates that the village and military post of Thamara (probably 'En Haseva) is one day's journey from Μαμψις, on the road from Hebron to Aila. In Saint Jerome's translation of this passage the site is called Mampsis. It seems that Mampsis also appears in the sixth century tax edict of Beersheba (Alt, GIPT, no. 1, the date is uncertain). Hierocles (Synecdemos 721.8; c. 530 CE) and Georgius Cyprius (Descriptio orbis Romani 1049; c. 600 CE) list Mampsis with the other cities in the province of Palaestina Tertia. On the Medeba map, an arched gateway flanked by towers, above which a red-roofed building rises, possibly the city's cathedral, appears under the name Μαμψις.

There is another reference to Μαμψις in one of the Nessana papyri (P Nessana no. 39, probably of the mid-sixth century CE). This papyrus contains two rosters of cities together with sums of money. In the first list, Mampsis appears fourth in the list, preceded by Nessana and followed by Oboda, with slight differences in amounts between the three. The scholar who published the document suggested that the sums of money in the list refer to taxes on agricultural products paid by wealthy farmers and the limitanei. According to this writer, this is unlikely because Mampsis's arable land is only a small fraction of that at Nessana and Oboda, and the estimated population of Mampsis (around 1,500) was far smaller than Nessana's (around 4,000) and half of Oboda's. This writer suggests that the list originated in an imperial or provincial office and records the annona militaris (military rations sometimes reckoned in money) paid to army units and units of the militia recruited in the three above-mentioned fortified cities.

Some scholars have identified Mampsis with mmst on lamelekh seal impressions from the Iron Age II. There is, however, no archaeological proof for such an identification because no Israelite pottery has been found at Mampsis or its surroundings. It is, furthermore, not at all certain that mmst is indeed the name of a town. The modern Hebrew name Mamshit was not adopted on the strength of this identification, but in an attempt to restore the original Semitic form of the name Mampsis.

In a marginal note on the map of U. J. Seetzen's voyage (1807) the name Kurnupp appears with the Arab names of the other Negev towns. At Kurnupp, Seetzen saw the remains of a fortress at the foot of a low hill, as well as traces of vineyards and orchards. E. Robinson viewed the site from a distance in 1838 and described it as a city built of cut stones. He subsequently distinguished what appeared to be churches or other public buildings. E. H. Palmer visited the site in 1871 but left only a short description of the ruins. The first detailed description of the site was provided by A. Musil (l901), who also drew a plan of the ruins. Musil noted that the city was surrounded by a wall flanked by towers and had churches in both its western and eastern parts. On Musil's plan the Eastern Church is shown in a separate walled area shaped like a triangle. The description is of particular importance because this eastern area was subsequently damaged by later building activity. Musil also noted the large tower in the western part of the town and the well in the valley to its south. C. L. Woolley and T. E. Lawrence drew up another plan of the remains in 1914 but without furnishing much detail. They did, however, record the dams and watchtowers around the city. They described the city as rather weakly defended against the Bedouin. They also noted both the gates of the city and, in its western part, remains of a large building near the tower. A large structure north of the Eastern Church is called the serai by them. In their opinion, the public buildings occupied about one quarter of the total area of the city. J. H. Illife visited Kurnub in 1934 and found Nabatean pottery and terra sigillata ware.

The most recent and most detailed survey was carried out by G. E. Kirk and P.L.O. Guy in 1937, on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund, following the construction of a police station on the site. Dissatisfied with Woolley and Lawrence's plan, they drew up a new, more detailed one. North of the town, near the northern gate, they found the remains of two very large buildings that had been covered by dunes. They also discovered a cemetery about one km (0.6 mi.) north of the town, with Nabatean pottery, terra sigillata ware, and black-glazed sherds on the surface. In the city proper, the surveyors noted two large ashlar buildings (appearing on their plan as A and B) and attributed them to the Roman rather than the Byzantine period. They further established that the two churches had probably been squeezed into a town plan that already existed before their construction. In the eastern quarter of the city, the surveyors noted a large building about 40 m long, with a row of rooms on either side of a central corridor.

In 1956, S. Applebaum, on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, carried out trial soundings near the inner side of the city's western wall. He discovered nine levels in four occupational strata, as follows:

- level II: fifth to seventh centuries CE

- level V: fourth to fifth centuries CE

- level VIII: fourth century CE

- level IX: third century CE or earlier

From September 1965 to October 1967, and again in 1971-1972, excavations were carried out at Kurnub, on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, under the direction of A Negev. The excavations were conducted in five main areas: the city fortifications, the western quarter, the eastern quarter, the caravanserai, and the Nabatean and Roman cemeteries. The pottery and building remains date from the Middle Nabatean period (the end of the first century BCE and the first century CE), the Late Nabatean period (second and third centuries CE), the Late Roman period (fourth century CE), the Byzantine period, and the Early Arab period.

Excavations were resumed in 1990, on behalf of the Hebrew University, again under the direction of A. Negev. Excavations were carried out in some of the buildings partially excavated from 1965 to 1967, and in two newly discovered buildings north of the city.

[Mampsis had] three major phases, turning from a guarded roadside caravanserai in the Nabatean period (1st century BC–1st century AD) into a flourishing and rich Middle Roman city (2nd–3rd centuries AD) and eventually becoming a Christian Byzantine city with two impressive churches (4th–mid-6th centuries AD).

The recent identification of a military camp and commander residency point to a military attendance at Mampsis already in the Nabatean Period. Two Latin inscriptions from the military cemetery, dated to Trajan and Hadrian eras, identify two of the burials: a Legio III centurion and an eques of the Cohors I Augusta Tracum.

Based on the sums of money specified in the Nessana Papyrus 39, dated to the mid-6th century AD, it seems that the city’s financial sustenance was based upon payments given by the authorities to the limitanei for their military service. Once this support ceased by Iustinian, probably after AD 532, and no money was available to pay the Saracens off, they invaded Mampsis burning down its main gate.

... Mampsis is situated on the southern margins of a valley in the northeastern Negev Highlands, c. 40km southeast of Be’er Sheva‘ and 5km southeast of Dimona (map ref. 206/548; 460–478 m asl). Three ancient roads led to the city (Figure 2): the road leading from the prosperous Nabatean region around the southern end of the Dead Sea towards Be’er Sheva‘, the road leading from the copper mining district of Faynan (Phaino) by way of Mezad Hazeva, and the road that connected Mampsis with Oboda.

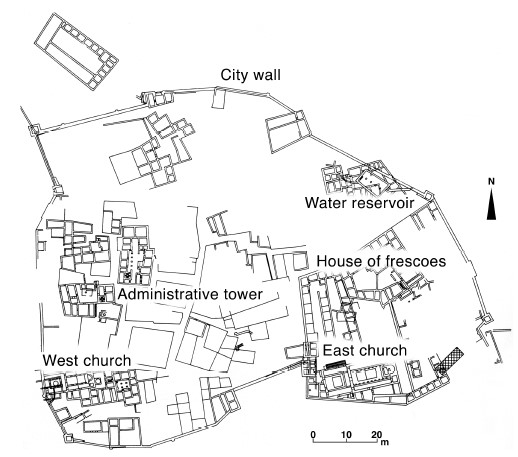

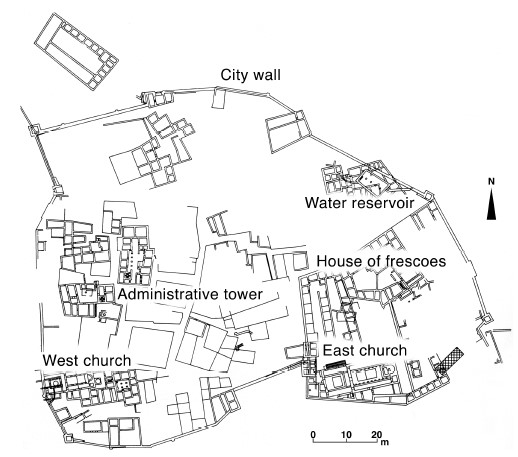

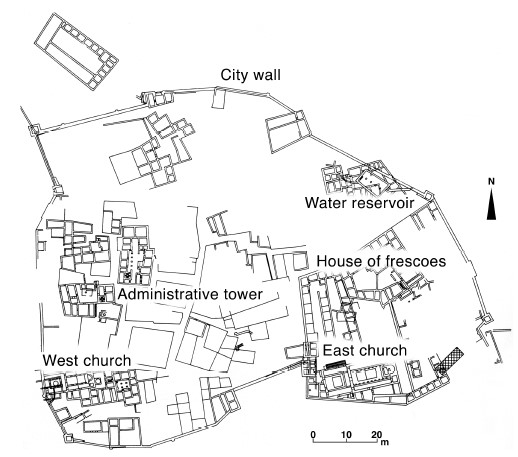

The city (130 × 150–270m), spanning over 10.5 acres, is set on two hills, eastern (6.5 acres) and western (4 acres, Figure 3), with a ravine running between them, and is bordered by two shallow ravines on the east and the west. A deep seasonal streambed, Nahal Mamshit, runs along the southern margins of the city, then turning to the southeast, cutting through the hard dolomite rock of the Ẓafit Formation along the Hatira anticline and exposing rocks that served as building material in the city.

... The residential area covers 15,245sq. m and including public structures sums to 24,540 sq. m (c. 60% of the city territory). The city is divided into four quarters: western, central, southwestern, and eastern. Outside the city wall are a caravanserai (VIII) and buildings that Avraham Negev suggested to be an architecture school (XXIII) and a gymnasium (XXII). A large area (40%) within the city remained unbuilt and the empty grounds between the huge buildings served as streets, alleys and piazzas (Figure 5: 1–10).

Buildings were well-preserved and the quality of workmanship exceeds any other city in the Negev.

- Incense Road Map with Mamshit

from BibleWalks.com

- Fig. 1.6 - Towns and Forts

in the Central Negev and Arava Valley during Early Roman through Byzantine periods from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.6

Figure 1.6

Towns and Forts in the Central Negev and Arava Valley. Early Roman through Byzantine periods.

Erickson-Gini (2010)

- Incense Road Map with Mamshit

from BibleWalks.com

- Fig. 1.6 - Towns and Forts

in the Central Negev and Arava Valley during Early Roman through Byzantine periods from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.6

Figure 1.6

Towns and Forts in the Central Negev and Arava Valley. Early Roman through Byzantine periods.

Erickson-Gini (2010)

- Fig. 8 - Aerial View of Mampsis

from Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Mampsis, looking west (photo G. Fitoussi).

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Fig. 7 - Aerial photo of

the eastern hill - from Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 7

Figure 7

The eastern hill, looking northeast (photo G. Fitoussi).

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Fig. 10 - Aerial photo

of Commander residency - from Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Commander residency (photo G. Fitoussi).

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Fig. 14 - Aerial photo

of Western Church Compound - from Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Western church compound, looking north (photo G. Fitoussi).

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Mamshit in Google Earth

- Mamshit on govmap.gov.il

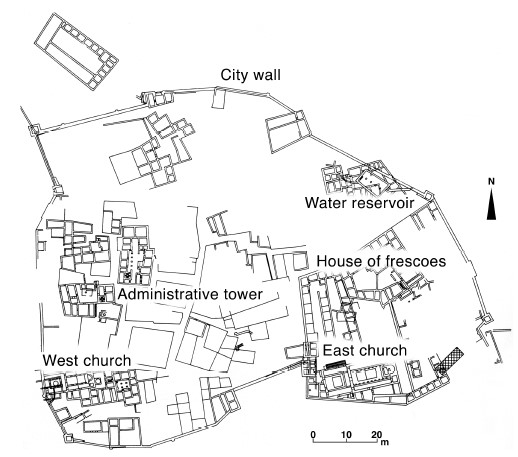

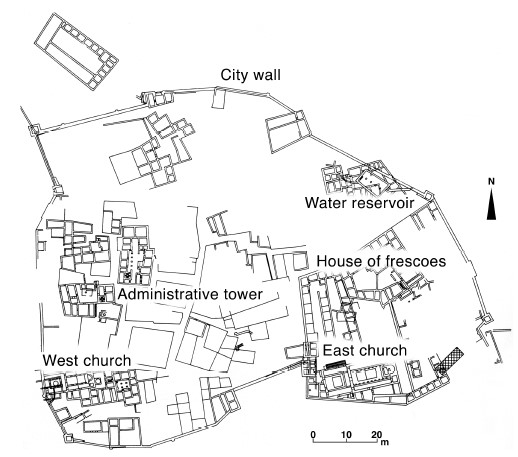

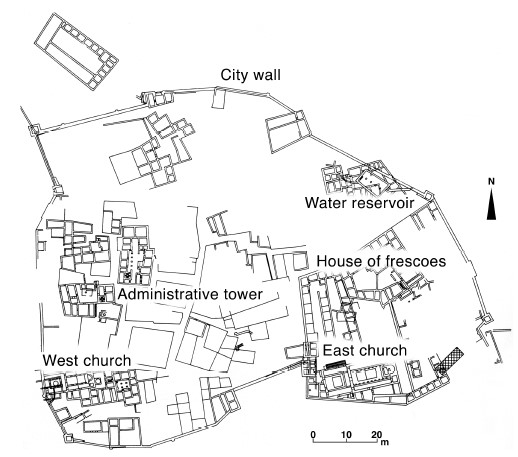

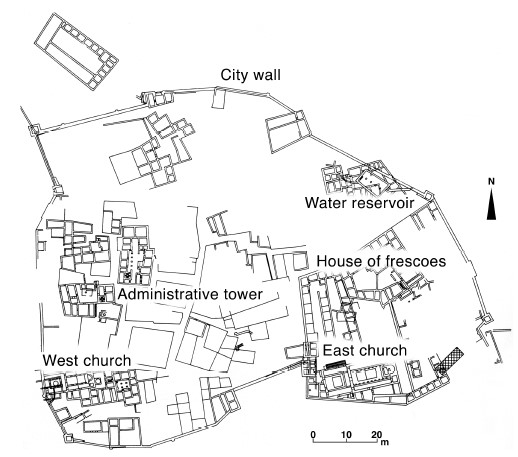

- Plan of Mamshit from

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Kurnub [aka Mamshit]: plan of the town.

Kurnub [aka Mamshit]: plan of the town.

- Building I, palace

- Building II, tower

- Western Church

- Building XV

- Building V, bathhouse

- Building VII, pool

- Building XII

- Eastern Church

- Main gate

- Water gate

- Building VIII, caravanserai

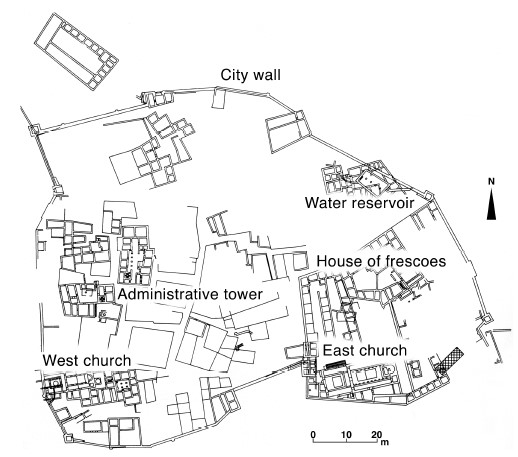

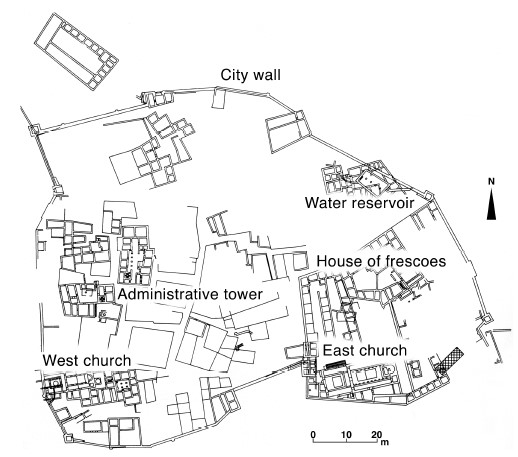

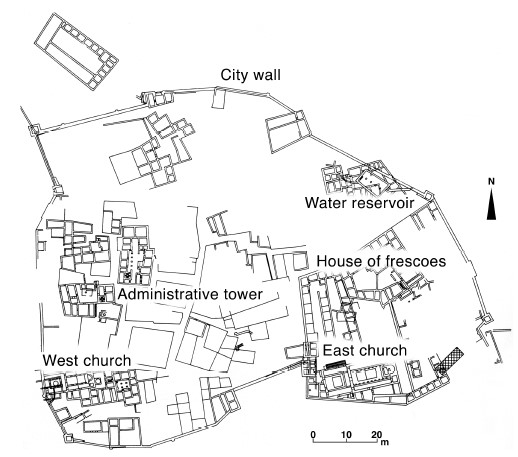

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 2a - City plan from

Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003)

Figure 2a

Figure 2a

City plan of ancient Mamshit

Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) - Fig. 5 - City Plan from

Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 5

Figure 5

City plan (O. Sion, S. Israeli and D. Porotsky).

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Fig. 6 - Plan of Mampsis

by period - from Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Insulae and Structures according to periods (O. Sion, S. Israeli and D. Porotsky).

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Site plan of Mamshit

from BibleWalks.com

- Plan 1 - Site plan of

Mamshit from Negev (1988b)

Plan 1

Plan 1

General plan of Mampsis

Negev (1988b)

- Plan of Mamshit from

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Kurnub [aka Mamshit]: plan of the town.

Kurnub [aka Mamshit]: plan of the town.

- Building I, palace

- Building II, tower

- Western Church

- Building XV

- Building V, bathhouse

- Building VII, pool

- Building XII

- Eastern Church

- Main gate

- Water gate

- Building VIII, caravanserai

Stern et. al. (1993 v.3) - Fig. 2a - City plan from

Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003)

Figure 2a

Figure 2a

City plan of ancient Mamshit

Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) - Fig. 5 - City Plan from

Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 5

Figure 5

City plan (O. Sion, S. Israeli and D. Porotsky).

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Fig. 6 - Plan of Mampsis

by period - from Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Insulae and Structures according to periods (O. Sion, S. Israeli and D. Porotsky).

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Site plan of Mamshit

from BibleWalks.com

- Plan 1 - Site plan of

Mamshit from Negev (1988b)

Plan 1

Plan 1

General plan of Mampsis

Negev (1988b)

- Fig. 9 - Plan of army camp

from Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Plan of army camp and commander residency (O. Sion and D. Porotsky).

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Fig. 9 - Plan of army camp

from Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Plan of army camp and commander residency (O. Sion and D. Porotsky).

Sion and Israeli (2022)

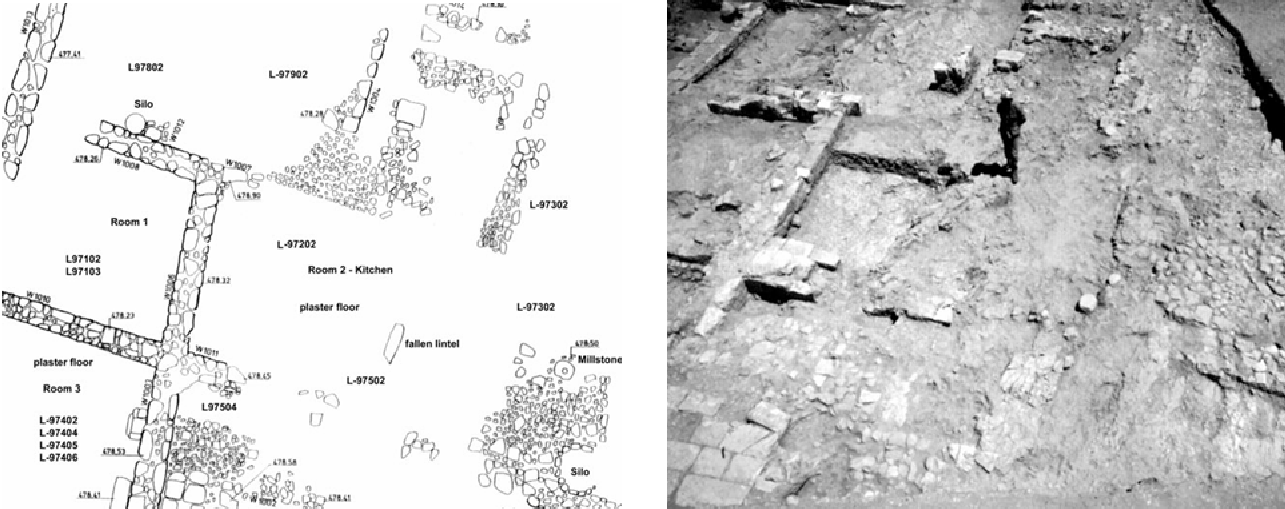

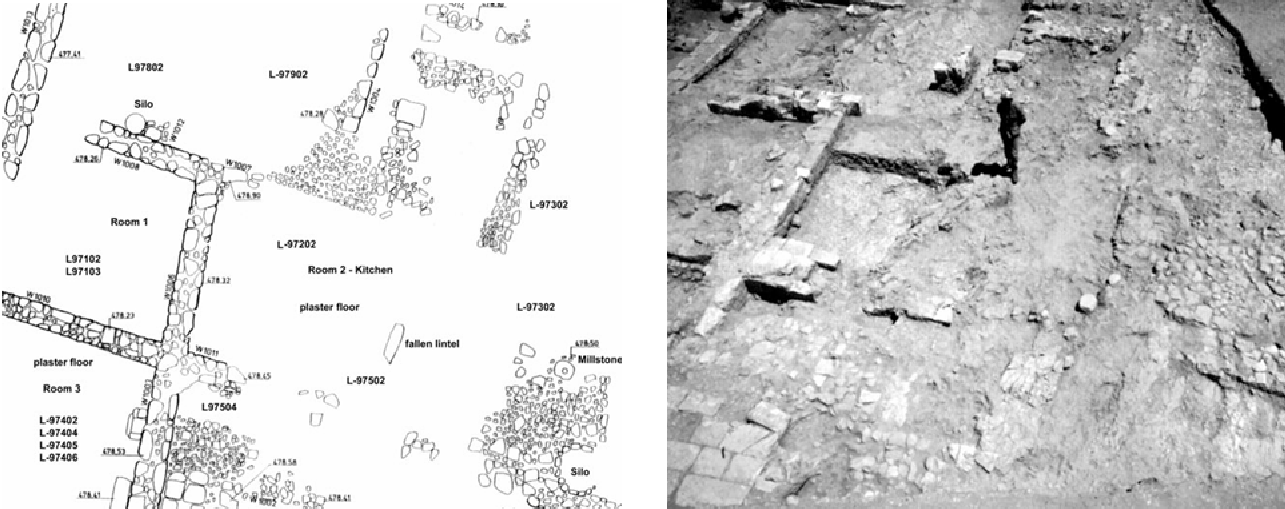

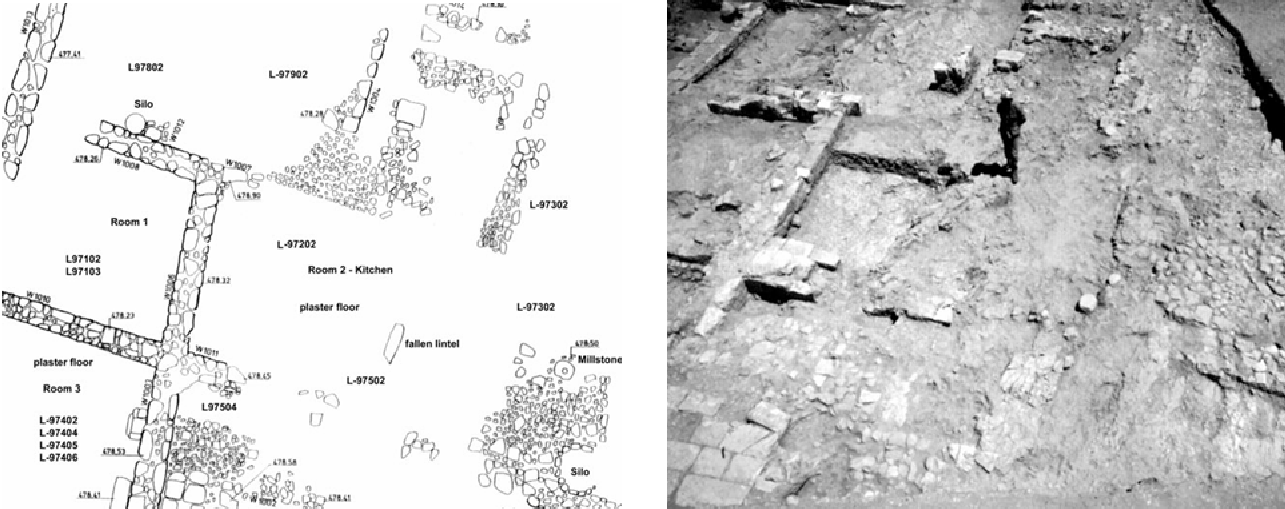

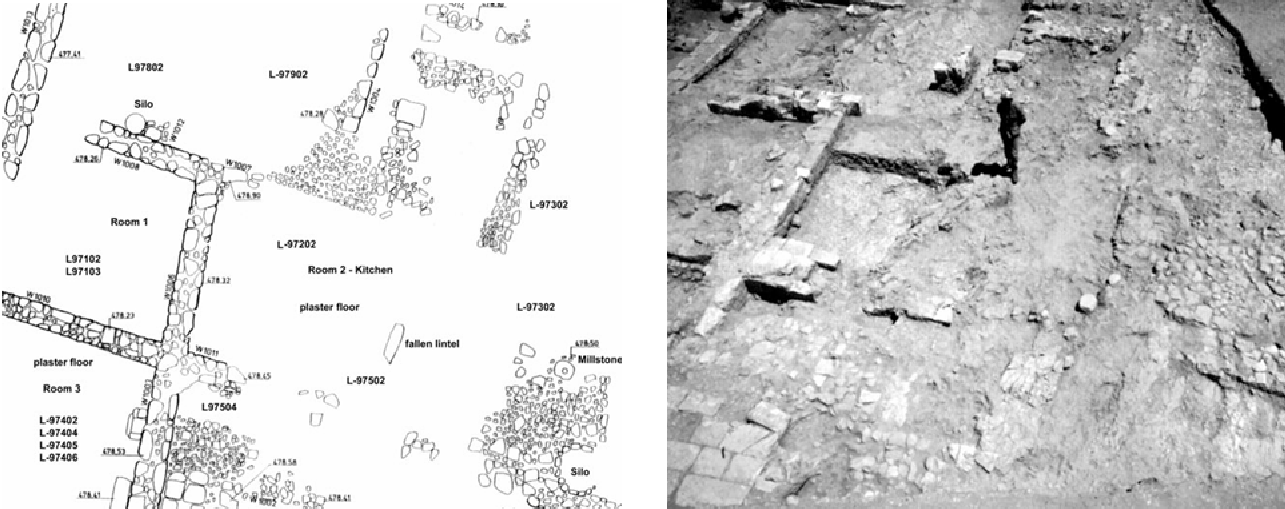

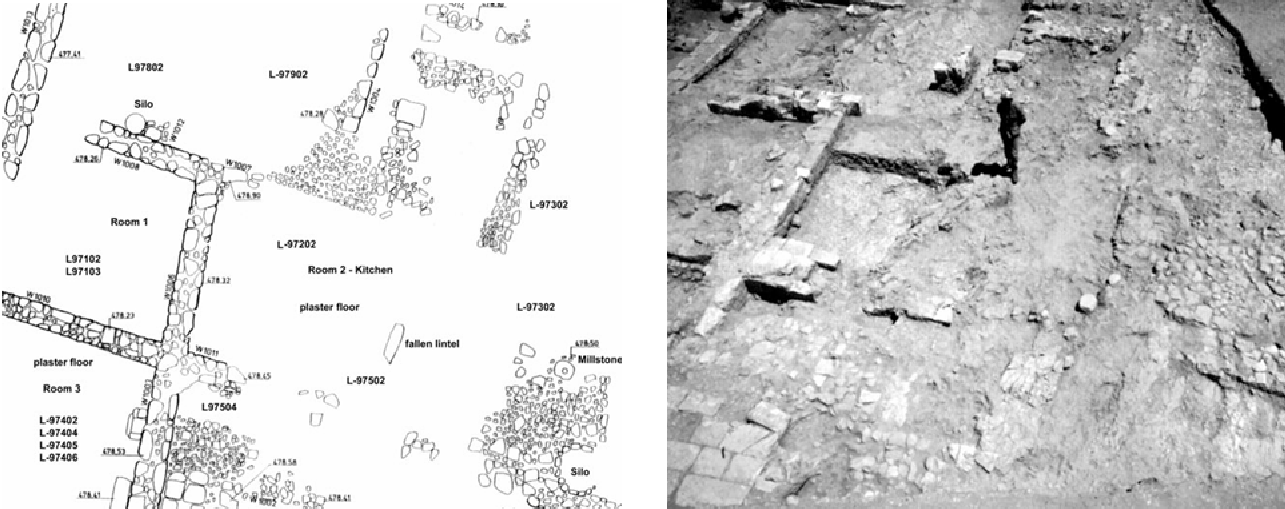

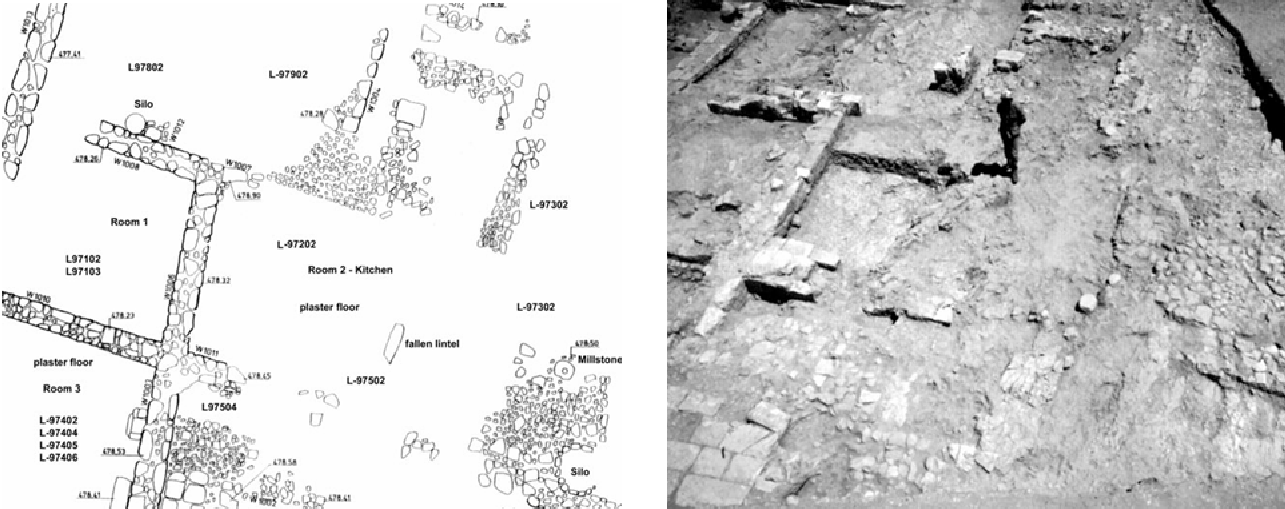

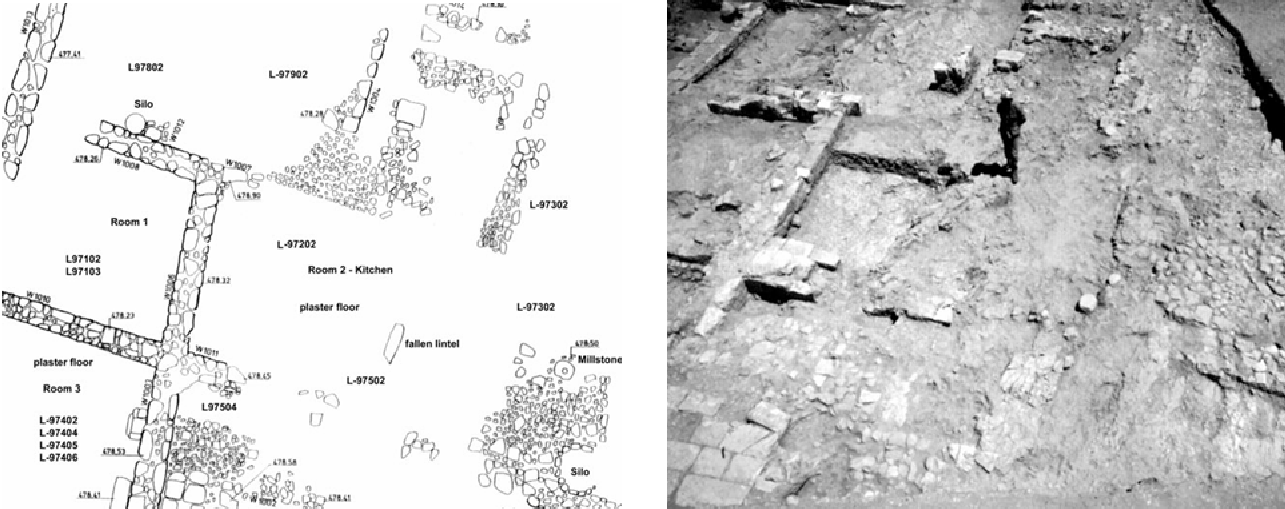

- Fig. 1.64 Plan and

Aerial View of Building XXV from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.64

Figure 1.64

Mampsis, Building XXV, plan and photo to east

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Fig. 1.64 Plan and

Aerial View of Building XXV from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.64

Figure 1.64

Mampsis, Building XXV, plan and photo to east

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Fig. 1.68 Plan of Building XII

South from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.68

Figure 1.68

Mampsis, Area Building XII South

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Fig. 1.68 Plan of Building XII

South from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.68

Figure 1.68

Mampsis, Area Building XII South

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Image courtesy of www.HolyLandPhotos.org

Mamshit in the Byzantine Period

Mamshit in the Byzantine PeriodImage courtesy of www.HolyLandPhotos.org

- Fig. 1.65 Building XXV section

from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.65

Figure 1.65

Mampsis, Building XXV section

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Fig. 1.65 Building XXV section

from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.65

Figure 1.65

Mampsis, Building XXV section

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Fig. 1.69 Building XII South

Section from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.69

Figure 1.69

Section drawing and debris layers in Area Building XII South, Mampsis

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Fig. 1.69 Building XII South

Section from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.69

Figure 1.69

Section drawing and debris layers in Area Building XII South, Mampsis

Sion and Israeli (2022)

- Fig. 1.66a In situ unguentarium

in Phase 2 from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.66a

Figure 1.66a

In situ unguentarium in Phase 2

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Fig. 1.66b in situ braziers

found in Phase 3, 363 CE from Building XXV from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.66b

Figure 1.66b

in situ braziers made of inverted “Gaza” wine jars found in Phase 3, 363 CE from Building XXV, Mampsis

Sion and Israeli (2022) - Fig. 1.67 Finds from the

kitchen in Phase 3 of Building XXV destroyed in the 363 CE earthquake from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Figure 1.67

Figure 1.67

Finds from the kitchen in Phase 3 of Building XXV destroyed in the 363 CE earthquake at Mampsis

Sion and Israeli (2022)

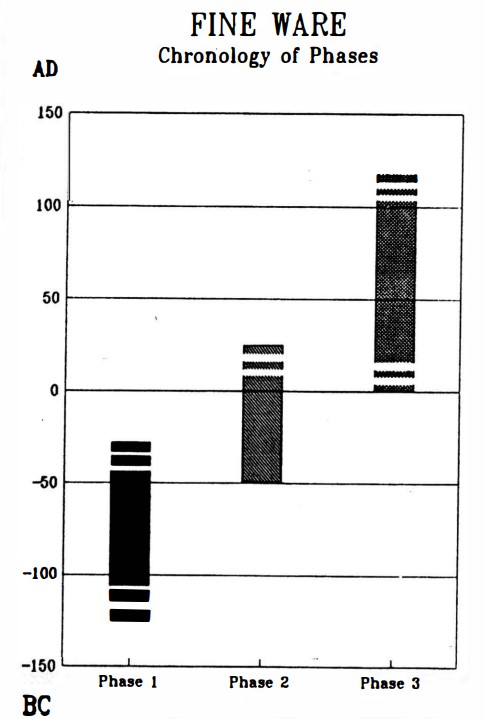

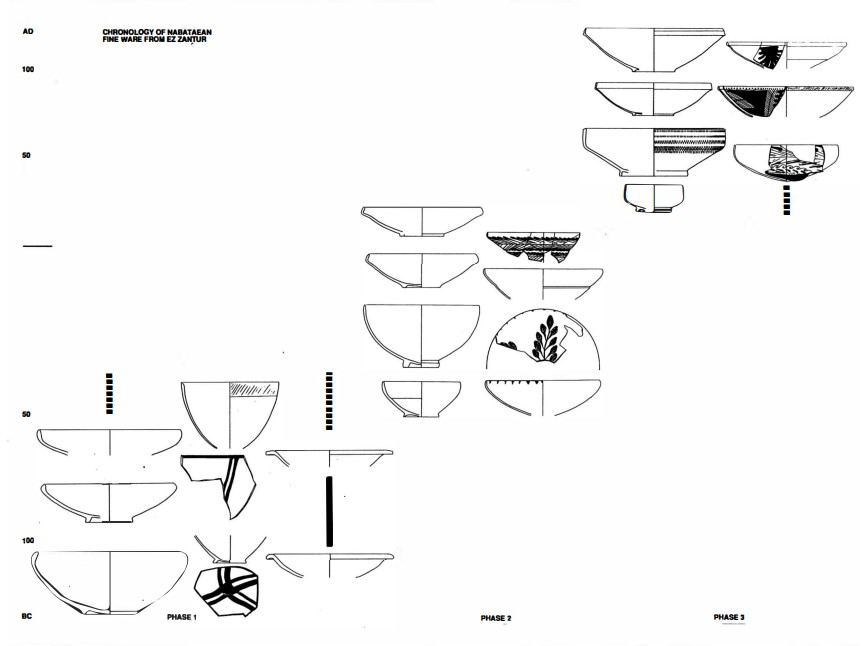

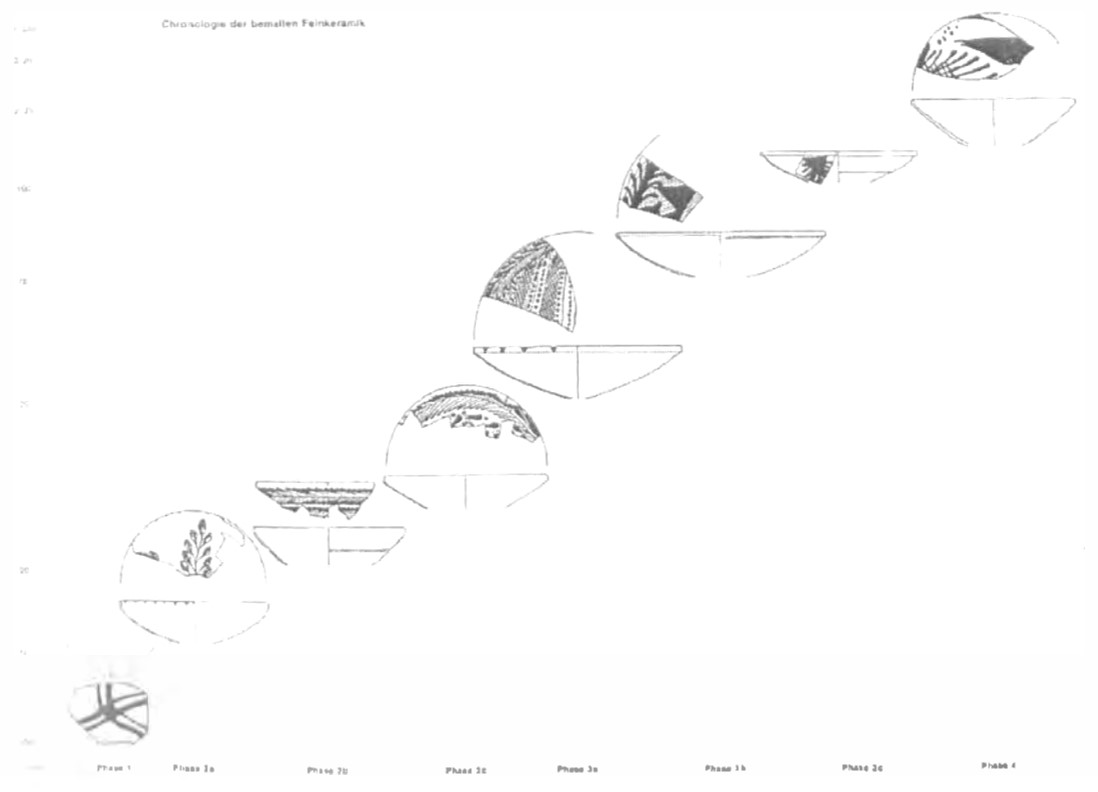

- from Schmid (1995)

Left

Chronology of Nabatean finewares

Right

Typology and chronology of the Nabataean fine ware

Both from Schmid (1995)

- from Dolinka (2006) citing Schmid (2000)

Figure 1.3

Figure 1.3Typo-chronology for the NPFW bowls developed by Schmid (2000: abb. 98)

Dolinka (2006)

Sion and Israeli (2022:252 n. 6) note that the urban development [i.e. Phasing Table] is based on Negev’s publications and

chronology, updated, and slightly revised by

Erickson-Gini (2010: 83–86)

.

| Period | Time Span | Discussion |

|---|---|---|

| Nabatean | 30 BC— AD 106 |

Discussion

|

| Middle Roman | AD 106-300 |

Discussion

History

Following the death of the Nabatean king Rabel II in AD 106, the Romans annexed the Nabatean kingdom to the

Roman Empire and founded the new Provincia Arabia. New security arrangements led to the construction of a

new road—the Via Trajana Nova—completed at AD 114-116. The III Cyrenaica Legion paved the road network

in the province and Mampsis appears to have been renovated in the late 1st to early 2nd centuries AD (Negev 1971b).7

Footnotes

7 Tali Erickson-Gini suggests that earthquake destruction in the late 1st or early 2nd century AD prompted a wave of construction at Mampsis and Oboda (Erickson-Gini 2014: 100; Erickson-Gini and Tuttle 2017: 141).

The Western Quarter

Twenty-one houses were constructed on the western hill (Figures 3, 6). Insulae A and B included

9 and 3 structures, respectively. Three pairs (G, F, E) and three single structures (C, D, I), mostly

residential (10 of 15), occupied the quarter. Structure D (Building I; Figure 8), dated to the Middle

Roman period (2nd-3rd centuries AD), was identified as a palace with a reception hall and special

decorative architectural elements (Negev 1988a: 66; 50-77). Structure F/2 (Building II) was an

administrative center containing a tower, a courtyard, halls, and storage rooms (Negev 1988a: 77-78).

Structure O/1 (Building XI) had an upper floor, stables, and a private shrine. It was partly destroyed in

the second half of the 4th century AD, probably during the earthquake of AD 363, whereafter the western

church was built (Negev 1988a: 88-109). Eastwards, Structure O/2 (Building XIa) was probably constructed in

the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD (Negev 1988a: 109–110). In Structure S (Building VIII), arches were constructed in a

new direction during the 2nd half of the 3rd century AD. Structure A/5 (Building XVI), southeast of the northern

city gate, was dated to the current period based on its masonry carving style. Structure F/1 (Building XVII)

was identified as stores and workshops of the period along with three rooms in Structure C (Building XVIII),

located northwest of Building I (Negev 1988a: 191-197). The so-called gymnasium (T; Building XXII),

a one-story structure, has many rooms surrounding a court (Negev 1993: 246-261).

The Eastern Quarter

The eastern quarter is located on

the high ground which observes the city and its environment. Its complexes (R, P, Q)

are of public nature. Insula P has two Middle Roman period structures (P/1, P/4),

over which a bathhouse (P/3) and a pool (P/2) were

built later.8 Structure Q, attached to the city wall and

excavated at its northern part, is 25m long and has rooms on its eastern

and western sides with a courtyard in between. At the southern high ground of the hill are two

structures surrounded by a wall (R/1, R/2; Figures 9-10). The first was well preserved, while

the other was destroyed in the 4th century AD, when the Eastern Church was erected. Negev assumed

that Structure R/1 (Building XII) was the governor's house, while Structure R/2 (Building IV) was a market (Negev 1988a: 75-78). |

| Byzantine | 4th— 6th c. AD |

Discussion

History

In the Late Roman period during the reign of Diocletian, the city was surrounded by a wall,

dated, based on coins revealed at its foundations and related architecture to around AD 300

(Negev 1988a: 64; 1988b: 9-29; Erickson-Gini 2010: 84-85).

The Central Quarter

Eighteen structures were observed in two insulae (L, M) at the central quarter,

and in the ravine between both hills, out of which 5 and 8 structures (respectively) were identified.

Most of these structures are domestic and they are relatively small and rather poorly built.

Larger structures (L/1 — 925sq. m; L/2 — 750sq. m) have spacious rooms and their plan and

location next to the city gate may indicate that they were storage facilities. Outstanding is

Structure J, which is poorly built and Structure N/22, which is rather small (320 Sq. m).

Footnotes

9 However, later excavations by Erickson-Gini in the courtyard entrance of Building XII revealed ceramic evidence dated to the 2nd half of the 6th and the early 7th centuries AD (Erickson-Gini 1999b: 101; Figs. 17: 6; 18: 5; 21: 3). Subsequent excavations in Building III between 2017–2020 substantiate the presence of ceramic wares beyond the mid-sixth century AD (Erickson-Gini pers. comm. 9.9.21). |

Figure 6

Figure 6Insulae and Structures according to periods (O. Sion, S. Israeli and D. Porotsky).

Sion and Israeli (2022)

Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) analyzed damage patterns at Mampsis utilizing 250 cases of 12 different types of deformation patterns

which they were able to resolve into two separate earthquake events on the basis of

the age of the buildings which showed damage. The fact that the two different events showed distinct directional patterns - the first earthquake with an indicated epicenter to the

north and the second with an epicenter to the SW - was taken as confirmation that they had successfully separated out archeoseismic measurements for each individual event. The first earthquake, according to

Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) struck around the end of the 3rd/beginning of the 4th century CE

and the second struck in the 7th century CE - at the end of the Byzantine period

. They

provided the following comments regarding dating of the earthquakes

To determine exact ages of the destructive earthquakes, which destroyed the ancient Mamshit, was not possible by methods used in given study. It has to be a special pure archeological and historical research by specific methods related to that field. Age of the first earthquake was taken from a work of Negev (1974) who has conducted main excavation activity in the site. As concern to the second earthquake – the archeological study reveals that the seismically destroyed Byzantine cities were not restored. So, most probably, one of the strong earthquakes in VII Cent. A.D. caused abandonment.Deciphering chronology at Mampsis has unfortunately been problematic.

Mamshit thrived, in spite of its location in a desert, thanks to runoff collecting dams, and storage of the precious rain water in public ponds and private cisterns. These installations were most probably severely damaged during the earthquake, cutting at once the daily water supply, forcing the inhabitants to seek refuge in the more fertile regions. This situation was most probably followed by looting by local nomads, turning a temporal seek of shelter into permanent abandonment.

Russell (1985) cited Negev (1971:166) for evidence of early second century earthquake destruction at Mamphis. Negev (1971) reports extensive building activity in Mamphis in the early second century AD obliterating much of the earlier and smaller infrastructure. However, neither a destruction layer nor an earthquake is mentioned. Citing Erickson-Gini (1999) and Erickson-Gini (2001), Korzhenkov and Erickson-Gini (2003) cast doubt on Russell (1985)'s assertion of archeoseismic damage at Mamphis stating that recent research indicates a continuation of occupation throughout the 1st and 2nd cent. A.D.. Continuous occupation could indicate that seismic damage was limited rather than absent.

Erickson-Gini (2010:83) reports that the Mampsis appears to have experienced extensive damage

in one of the

363 CE Cyril Quakes while noting that

the damage predates structural changes in buildings at the site and the construction of two churches

.

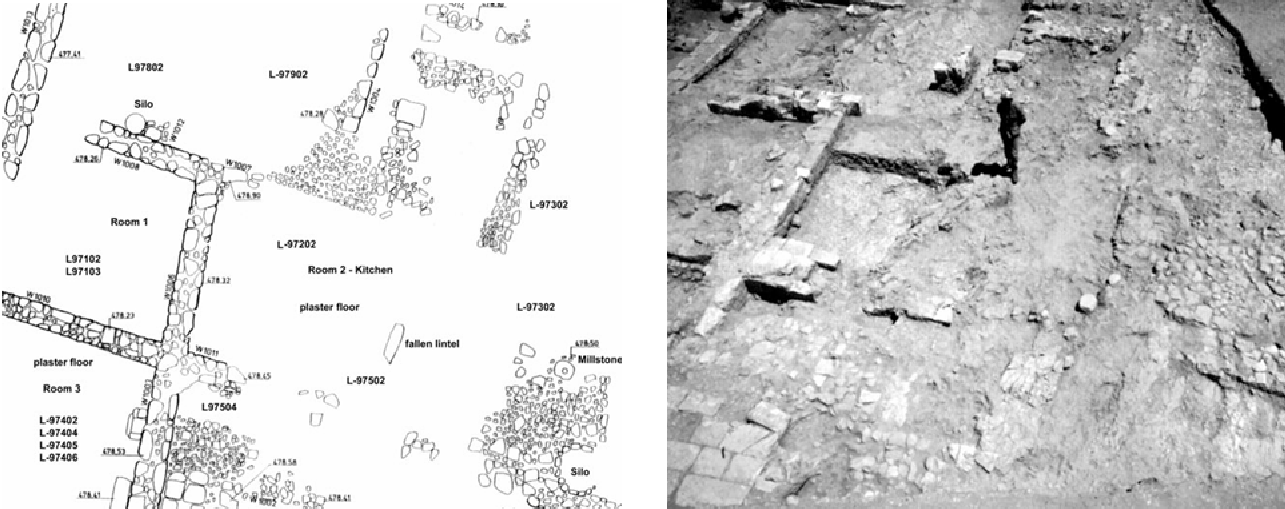

Building XXV was said to have been particularly hard hit. This building, according to

Erickson-Gini (2010:129), sustained such heavy damage that it was abandoned and never rebuilt

. Room 2, apparently

used as a kitchen, preserved a rich lode of pottery sealed and found in situ on the floor of the collapsed room. Some of the pottery

was interpreted as having fallen from shelves in the "kitchen".

Erickson-Gini (2010:80) reports that in situ coins were found in the earthquake debris in Building XXV.

Erickson-Gini (2010:129) reports that the walls of adjacent Rooms 1 and 2 ("kitchen") of Building XXV were rather insubstantial

additions to the original structure

which were constructed in a shallow layer of soil

which

appears to have contributed to the collapse of the kitchen.

The first excavations at Mampsis were carried by S. Applebaum in 1956 and 1959. Applebaum investigated an area near the walls of the western side of the town, revealing occupation layers dating no earlier than the third century CE (Applebaum 1956:191-192; 1959:30-52).

The most extensive excavations of the site were carried by A. Negev, sponsored by the Hebrew University at Jerusalem, between 1965 and 1967, and again in 1990. His investigations were carried out in the site’s two Byzantine churches and in several large residential structures constructed in the second century CE that remained in use into the Byzantine period. Negev also excavated a Nabataean/Early Roman fort (Building XIV) and a Nabataean/Early Roman caravanserai located outside the city walls (Negev 1993: 241-264). Other investigations at the site included the excavation of a public bathhouse (Building V) and a public reservoir (Building VII). The architectural features of the town were published in two volumes in 1988 in The Architecture of Mampsis, Vols. 1 & 2 (Negev 1988a; 1988b). In the largest residential structure excavated at the site, Building XII, Negev discovered a hoard of 10,800 silver coins, the latest of which dated to the reign of Elagabalus (218-222 CE), (Negev 1988a: 145). Negev also excavated a Nabataean necropolis dating to the first through early fourth century CE located east of the town (Negev 1971: 110-121; Negev and Sivan 1977). A Roman military cemetery also located outside the town revealed two Latin epitaphs belonging to a centurion of the Legio III Cyrenaica and a cavalryman of the Cohors I Augusta Thracum (Negev 1969: 9). Other studies of the site included those of the dams in Nahal Mamshit carried out by A. Kloner (Kloner 1973: 248-275; 1975: 167-170). Further excavations were carried out by O. Katz of the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1992 and Erickson-Gini in 1993 1994. The latest excavations at the site were carried out in three areas: in a midden located north of the town walls dated to first and early second centuries CE, in an area next to Building XII and inside the building (L428), and in the area under and east of the British Police building. This last area revealed a previously unknown structure, Building XXV, constructed in the late first or early second centuries CE, that was occupied in three phases until its destruction in the fourth century by an earthquake (Erickson-Gini 1995:95-96; 1997:133-134; 1999), (Fig. 1.30). ...

The site of Mampsis is situated on a low hill, 479 m. above sea level, overlooking the steep gorge of Nahal Mamshit, a few kilometers southeast of the modern town of Dimona. The location appears to have been a natural key point along ancient tracks leading up from the Dead Sea and the Arava Valley (by way of Ma’ale Tsafir), and it was well situated with defensive advantages provided by the steep gorge on its southern edge and its commanding view of the area north and east of the site.

The site was first settled by the Nabataeans as a major caravan station along the route leading from the Dead Sea to the northern Negev in the mid-first century CE (Erickson Gini 1999:95). This road connected Nabataean sites at the southern end of the Dead Sea in the region of ‘En Tamar with Mampsis by way of the Tamar station. Mampsis stood at the junction of this major road and the Ma’ale Tsafir (Scorpions Pass) Road leading from the central Arava at ‘En Hazeva. From Mampsis the road passed by other Nabataean stations at Aroer and Malhata, where material evidence of their presence has been found, leading from these points to Be’ersheva and the Hebron hills into Judaea (Hershkovitz 1992; Erickson-Gini 1999:95).

The town was built up extensively in the later half of the second century CE, following its inclusion in the Roman Provincia Arabia. Evidence of the presence of Roman military officials in the second century associated with the III Cyrenaica legion and Cohors I Augusta Thracum have been found at the site (Negev 1969:9). The town underwent a revival in the late third century under Diocletian when a town wall with towers was constructed around most of the buildings at the site (Negev 1988b: 4). In this period the town was an active station connecting the fort at ‘En Hazeva with the Be’ersheba region and Judaea by way of the Scorpions Ascent road. It was mentioned by Eusebius as being located a days journey from the “soldier’s post” of Tamara (probably ‘En Hazeva), (Eus. On. 8). It may also have been the post of the Cohors Quarta Palaestinorum placed at Thamana and listed in the Notitia Dignitatum (Dodgeon and Lieu 1991:344). During the reign of Diocletian several small forts were constructed along the road between the large fort at ‘En Hazeva and Mampsis in proximity to Ma’ale Tsafir (the Scorpions Pass) at Mezad Sayif, Rogem Tsafir, Horvat Tsafir, Mezad Tsafir and Mezad ‘En Yorqeam (Cohen 1983c: 65-67; Cohen 2000:100-103).

The town appears to have experienced extensive damage in the earthquake of May 19, 363 CE. The damage predates structural changes in buildings at the site and the construction of two churches.1 During the Byzantine period, it does not appear to have enjoyed the same level of prosperity as that of the large towns in the west central Negev. The site covers an area of forty dunams and in spite of enjoying a higher average rainfall (135 mm as compared to 100 mm in the west central Negev), the surrounding region has the lowest total area of terraced farmlands in the Negev, consisting of only 6,200 hectares (Bruins 1986:15, 24). It has been suggested that in the fifth and sixth centuries the inhabitants of the town were dependent almost entirely on stipends provided by the Byzantine authorities and that site was largely abandoned when these payments ceased and the town was exposed to Saracen incursions (Negev 1990:356-357).

1 Unlike Oboda where extensive reconstruction of the site took place, together with the construction of churches, after a devastating earthquake in the early fifth century CE described here above.

Two seasons of excavations were carried out by the author on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1993 and 1994 in order to facilitate the development of the site by the National Parks Authority. Two of the excavated areas revealed remains dating to the third and fourth centuries (Fig. 1.26). These include Building XXV, a previously unknown structure, situated between the south-east tower of the town wall and Building XIV, and Area Building XII South, an area of debris covering a late second century structure that was partially destroyed in order to make way for the construction of Building XII, the largest domestic structure found in Mampsis.2

Building XXV contained three phases of occupation and construction dating to the late first or early second century CE, the late second through third century and the fourth century until 363 CE (Fig. 1.64-65). At that time, the building was destroyed by an earthquake and the area abandoned. In its earlier phases, the primary structure underwent innovations and additional construction in the late second century C.E. and remained in use throughout the subsequent period. A Nabataean piriform unguentaria dated to the second century CE and a glass vessel were placed below the flagstone floor in Phase 2, apparently as a foundation offering (Fig.1.66). Foundation offerings in the form of ceramic unguentaria or bowls have been found elsewhere at Nabataean sites including the forts of ‘En Erga and ‘En Rahel in the Arava Valley, under the altar in the open shrine Qasra and more recently in the Great Temple in Petra (Joukowsky 2002:319).

In the early fourth century CE a service wing consisting of two rooms and cobbled exterior area were constructed between the primary structure and the town wall. A wall extended between the service wing and the town wall, constructed in the late third century. One room of the service wing was a kitchen, the contents of which were found in situ from the moment of the destruction in 363 CE (Fig.1.66, lower). This building was partially stripped of building stones and abandoned, and the immediate area was cut off from the rest of the town by the construction of a wall extending from the East Church to Building XII.

The sealed contexts of the latest occupation of Building XXV provide valuable material evidence dating to the time of the earthquake in 363 CE (Fig.1.67). In Area Building XII South, the remains of one of the earliest structures at the site, dated to the mid-first through late second century were uncovered (Figs. 1.68-69). This structure, and others due eastwards excavated by Negev, was destroyed sometime in the second half of the second century when the large villa, Building XII, was constructed. In order to carry out the construction of Building XII, covering an area of approximately 1000 m., the bedrock on the hillside was leveled in terraces. This type of manipulation of the bedrock appears to be a hallmark of Nabataean construction and it has been detected more recently in the excavation of the Great Temple at Petra (Joukowsky 2002: 326). The south wall and foundation trench of Building XII cut through the floor of the earlier structure found on the southern exterior of the building, only a few centimeters from the tabun of one of the rooms. The tabun had been stopped up with fieldstones, presumably in order to create an even surface close to the wall. Several layers of debris were found built up over the remains of the earlier structure between the late second century and the Late Byzantine period. Pottery dating to the third century was found in the layers deposited immediately above the abandoned structure.

2 The numismatic evidence found in the 1993-1994, as well as other metal finds, were cleaned by the laboratories of the Israel Antiquities Authority under the direction of E. Altmark. The numismatic finds were identified and a report has been prepared for their publication by R. Kool. The ceramic and small finds, as well as the plans and sections in the excavation were drawn by Y. Kasabi. The ceramic finds were photographed by Y. Lavi.

On May 19th, 363 CE, a massive earthquake struck the East, causing great damage to cities and towns along the Syrian-African rift and as far away as the Mediterranean coast. Compared to other earthquakes in ancient times, this particular event was well documented in historical sources and in the archaeological record. In situ evidence from this event has been found in several sites in our region, at Petra and in the Negev sites at Mampsis, ‘En Hazeva and Oboda. This earthquake, whose epicenter was probably located in the northern Arava valley, did not destroy whole sites but caused considerable damage and subsequent reconstruction that can be identified in the archaeological record (Mazor and Korjenkov 2001: 130, 133).

The clearest in situ evidence for this event was found in Building XXV at Mampsis. This entire building, situated as it was on a hilltop, sustained such heavy damage that it was abandoned and never rebuilt. One room in this house was used as a kitchen that was apparently in use when the earthquake struck. As a result, nearly the entire contents of the kitchen was found in situ, at floor level, including evidence of objects that fell to the floor from shelves along two walls. The walls of the kitchen (Room 2) and an adjoining room (Room 1) were rather insubstantial additions to the original structure and unlike the earlier Nabataean walls constructed on bedrock, these walls were constructed in a shallow layer of soil. This inferior construction technique appears to have been a major contribution to the collapse of the kitchen.

‘En Hazeva was situated in the Arava valley itself, in close proximity to the epicenter. The effects on this site were truly devastating, and the Late Roman fort and army camp underwent massive renovations. This was particularly true in the case of the cavalry camp situated below the fort. The walls in this camp were constructed on shallow foundations in soil and as a result, the original structure appears to have been completely shattered. The bathhouse adjoining the camp was built more solidly, although it too contains substantial cracks and subsequent renovations. The fort, which was founded on the walls of earlier buildings on the tell, withstood the earthquake to some extent, but whole floors with crushed in situ pottery appear to have been abandoned and covered by new floor surfaces in the subsequent phase of occupation.

Oboda was situated much further from the rift valley and although it was affected by the earthquake in 363, recent excavations have shown that this damage was limited in scope. In the Late Roman Quarter, some structural damage and renovations were noted, but this event did not create massive devastation at the site as was earlier thought to have occurred.

The 363 earthquake has left valuable evidence of pottery and other finds from the mid-fourth century CE that will be discussed here. An examination of this evidence makes it immediately apparent that few pottery types survived the transition from the third century CE. However, much of the pottery, and particularly the lamps found at the three Negev sites, were still produced in the region of Petra and southern Jordan as in earlier centuries. This in itself implies a continuation of material and cultural ties between the Negev and southern Jordan, a relationship that was undoubtedly rejuvenated by the activity of the Late Roman army in the region in wake of the transfer of the Tenth Legion from Jerusalem to Aila.

Other forms of vessels, such as fine ware bowls and amphorae, were brought from abroad, usually from the Eastern Mediterranean region. The one overwhelming type of vessel in fourth century assemblages throughout the Negev was the Gaza wine jar, corresponding to Majcherek’s Form 2, dated 300-450 CE (Majcherek 1995:Pl.5, 167-168). This type of jar was produced in the Gaza and Ashkelon region as has recently been proved on the basis of recent petrographic studies (Fabian and Goren 2002:148-149). Gaza jars were circulating in the Central Negev to such a great extent that by 363 CE it was common to find it in secondary use as braziers.

Evidence of Roman military presence can be detected in the distribution of a small, wide-mouthed storage jar that appears to have been designed to ration out wine or some other liquid. This type of jar was found extensively at the fort in ‘En Hazeva, but also at Oboda.

In the examination of the historical sources concerning the third and fourth centuries it is obvious that although general information concerning developments in the East exists, very little of this information pertains to the history of the central Negev. In the face of this dearth of historical data, archaeological findings provide details with which to trace the development of the region in a crucial phase of its history. The following are the results of an examination of the archaeological evidence and the implications of this evidence as it pertains to the accelerated growth in settlement and agriculture that took place in the fourth century CE.

The Results of an Examination of the Material Evidence

Material evidence has been presented here from three sites: Mampsis, Oboda and Mezad ‘En Hazeva dating to the period between the early third and the early fifth century CE. This evidence, mainly in the form of ceramic assemblages, is important in different ways. First of all, the contexts in which the main assemblages were found were primary, “Pompeii-type” deposits, i.e. the material was deposited together, abandoned and sealed as opposed to deposits of archaeological material added to over a number of years in a tomb, or thrown as refuse into a well or midden. Sealed, primary deposits provide rare data on the actual quantity and types of wares used simultaneously. Secondly, when the material from these three assemblages are studied together, patterns emerge that can shed light on economic and cultural trends. These patterns and other clues derived from the archaeological record mount in importance when historical evidence, particularly at a local level, is lacking for a particular region, as in this case the central Negev during the period under discussion. The results of studying these assemblages may be summed up as follows (Figs.1.90-91):

- The pottery assemblage dated to the first half of the third century CE is radically different in type and quality from the assemblage of the mid-fourth century. Vessels from the earlier assemblage reflect the international long distance trade of luxury goods passing through the central Negev, and particularly unguents produced and packaged in Petra. Nabataean fine wares produced in Petra, Eastern Terra Sigillata wares produced abroad and glass vessels from as far away as Nubia and Dura Europos were circulating through the region until the early to middle third century CE.

- Material evidence in the form of inscriptions found at Oboda and the continuous archaeological record found at Mampsis both indicate that the settlements in the central Negev were not abandoned during the third century. A tradition of local pottery production continued throughout this period and some local plain ware types survived well into the fourth century CE. The region appears to have been cut off from international trade and fine wares produced abroad were no longer reaching the area until after the Diocletianic period (Figs.1.64-65).

- The ceramic assemblage in the fourth century reflects new economic activity that replaced the long distance trade of the earlier period. The new economy was based on inter-regional trade of agricultural produce and particularly the production of wine. Wine jars produced in the region of Gaza and Ashkelon circulated with increased frequency through the region by the mid-fourth century and these jars are among the through the region by the mid-fourth century and these jars are among the most common vessels found at sites throughout the region in this period. Other vessels produced outside the Negev, such as African Red Slipped wares and Beit Natif style lamps, begin to appear in the Negev towards the middle of the century.

- The economic and cultural ties between the Negev and Petra continued in the fourth century and were revitalized by the regional build-up of the Roman army from the time of Diocletian. Pottery of a lower quality produced in Petra continued to flow into the Negev towns until the earthquake of 363 CE.

- By the early fifth century CE, the ties with Petra and southern Jordan began to wane and local pottery production increased. There are some indications that more pottery began to arrive from of what is central and northern Israel and Transjordan. The circulation of Gaza wine jars in the towns of the central Negev increased to such a great extent that they are often found in secondary use as braziers. Rare evidence of the survival of Nabataean language and religion is found at Oboda.

Negev (1974) dated the first earthquake to late 3rd/early 4th century via coins and church architectural styles however he dates construction of the East Church, where some archaeoseismic evidence for the first earthquake was found, to the 2nd half of the 4th century CE.

The date for the second earthquake also seems tenuous as

Negev (1974:412) and Negev (1988) indicate that Mampsis

suffered destruction by human agency long before the official

Arab conquest of the Negev

and the town ceased to exist

as a factor of any importance after the middle of the 5th century

.

However, Magness (2003) pointed out that there is evidence for some type of occupation at

Mampsis beyond the middle of the 5th century CE.

The small amount of Byzantine pottery published to date from Mamshit also indicates that occupation continued through the second half of the sixth and seventh centuries. There are examples of dipinti on amphoras of early fifth to mid seventh century date. Early Islamic presence is attested by Arabic graffiti on the stones of the apse of the East Church (Negev, 1988). More recently published evidence for sixth to seventh century occupation, as well as for early Islamic occupation, comes from a preliminary report on the 1990 excavations. The description of Building IV, which is located on the slope leading to the East Church, states that "the building continued to function in the Early Islamic period (7th century c.E.) with no architectural changes 122. The large residence, Building XII, contained mostly material dating to the fifth century, but pottery of the "Late Byzantine and Early Islamic periods" was also present 123. In 1993-94, T. Erickson-Gini conducted salvage excavations in several areas at Mamshit, under the auspices of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The pottery she found includes Fine Byzantine Ware Form lA bowls, and examples of Late Roman "C" (Phocean Red Slip Ware) Form 3, African Red Slip Ware Form 105, and Cypriot Red Slip Ware Form 9 (Erickson-Gini, 2004). This evidence indicates that the occupation at Mamshit continued through the late sixth century and into the seventh century. The Arabic graffiti on the apse of the East Church reflect some sort of early Islamic presence at the site, the nature of which is unclear.Considering this dating difficulty, I am labeling the date for the second earthquake as "5th -7th centuries CE ?".Footnotes122 S. Israeli, Mamshit-1990, Excavations and Surveys in Israel 12 (1994) 103.

123 S. Israeli, Mamshit-1990, Excavations and Surveys in Israel 12 (1994) 103.

- from Lower parts of buildings (built in Nabatean and Roman Periods)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Tilting of Walls | E of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Entire Site |

3a

Figure 3a

Figure 3aTilted walls. South side of the north wall of a room east of the west Church, the wall has a trend of 86° and the average inclination is 79°. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 3b

Figure 3b

Figure 3bTilted walls. North side of the same wall, the lower stone rows are tilted northward by up to 60° Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 3c

Figure 3c

Figure 3cTilted walls. Summary of measurements: direction of tilting patterns observed at the lower parts of walls at Mamshit (Tab. 1), as a function of the direction of the walls, revealing that out of 30 cases of walls trending ENE (55° to 105°), 26 were found to be tilted northward, 180 and only 4 cases are tilted southward, whereas the perpendicular walls (trending 145° to 185°) show only 9 tilting cases with no preferred direction Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 3d

Figure 3d

Figure 3dTilted walls. Stress directions concluded from the observed tilting patterns Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: tilted walls or wall segments (Figs. 3 a. b). By convention, the direction of tilting is defined by the direction pointed by the upper part of the tilted segment. Only cases of tilting of most of the wall were included in this study.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Lateral Shifting of Building Elements | E of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

4

Figure 4

Figure 4Lower stone of a N-S trending (175°) arch, shifted 8cm northward (the original position is marked by dashed lines). This is the fourth arch of the eastern line of fodder-basins of the Stables. The lowest stone of the arch has been severely cracked during the seismically caused shifting Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: northward shifting by 8 cm, as well as severe cracking of the lowest stone in a 175° trending arch (Fig.4). Thus, a large building element was shifted, and in addition slightly rotated clockwise. The location is at the eastern line of fodder-basins of a complex of stables, at a residential quarter east of the West Church.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Rotation of Wall Fragments around a Vertical Axis | ENE of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Near Frescoes House

Figure 2c

Figure 2cEast Church and House of Frescoes Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Entire Site |

5a

Figure 5a

Figure 5aRotation patterns at walls of the Roman period. Clockwise rotation of stones of the lowest row of a 172° trending wall of a room ENE of the West Church; stone A was rotated by 5° and stone B by 10°, the horizontal displacement of the two stones being 21.5cm. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 5b

Figure 5b

Figure 5bRotation patterns at walls of the Roman period. A 2° counterclockwise rotation of stones in the lower part of a 59° trending wall at a yard near the Frescoes House. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 5c

Figure 5c

Figure 5cRotation patterns at walls of the Roman period. Angle of rotation as a function of wall trends: SES (150°-185°) trending walls reveal mainly clockwise rotation, whereas walls trending NEN (60°-95°) reveal mainly counterclockwise rotations Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 5d

Figure 5d

Figure 5dRotation patterns at walls of the Roman period. Stress directions concluded from the observed rotation patterns Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: 1. An example of clockwise rotation of stones within a wall trending 172°, in a room located ENE of the West Church (Fig. 5 a). Stone A was rotated 5° clockwise and stone B was rotated 10° clockwise, the horizontal displacement between these rotated stones being 21.5 cm.. An example of a counterclockwise rotation in the northern wall of the Frescoes House (Fig. 5 b); the trend of the wall was 59° and the azimuth of the rotated wall fragment is 57°.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Cracking of Door Steps, Staircases and Lintels | Administrative Tower

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) E of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Entire Site |

6a

Figure 6a

Figure 6aCracks in the southern (left) edge of a doorstep and the southern doorpost, at an entrance trending N-S (175°), leading to a room west of the Administrative Tower. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 6b

Figure 6b

Figure 6bA similar set of cracks in the entrance to a room east of the Administrative Tower. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 6c

Figure 6c

Figure 6cStress directions concluded from the observed cracked patterns, disclosing movement of the adjacent walls Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 7a

Figure 7a

Figure 7aOpen cracks at the bottom and closed cracks at the top of a E-W (83°) trending staircase inside a Late Nabatean Building, and tilted side walls Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 7b

Figure 7b

Figure 7bStress directions concluded from the observed open and closed crack patterns, disclosing northward movement of southern walls. Thus the seismic push arrived from north Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 8

Figure 8

Figure 8Number of cracks observed in doorsteps, staircases and lintels as a function of the direction of the latter. The number of observations in N-S structures is three times greater than the observations in the perpendicular walls, leading to the conclusion that the seismic shock arrived from north Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: A 175° trending doorstep of the entrance into one of the rooms of the Administrative Tower was cracked at its southern part (Fig. 6 a) and a similar damage pattern is seen in the doorstep of another room, located eastward within the same building (Fig. 6 b).- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Slipped Keystones of Arches | W of Eastern Church

Figure 2c

Figure 2cEast Church and House of Frescoes Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Stables - E of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

9a

Figure 9a

Figure 9aKeystone, slipped down 6cm in a N-S (174°) trending arch in a room west of the Eastern Church Korjenkov and Mazor (2003)

Dropped Keystone of Mamshit

Dropped Keystone of MamshitRear View Long Shot Photo by Jefferson Williams 12 Jan. 2023 9b

Figure 9b

Figure 9bTwo central stones, slipped 3cm down in an N-S (175°) trending arch above the third fodder-basin in the Stables Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 9c

Figure 9c

Figure 9cDiagram of the operating stresses, leading to the conclusion that the seismic wave propagation was approximately parallel to the damaged arches, i.e. along a N-S direction Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: A 174° trending arch, located in a room west of the Eastern Church, exhibits a keystone that slipped 6cm down of its original position, as can be seen in Fig. 9 a. A pair of keystones slipped 3cm down in a 175° trending arch located above the third fodder-basin in the Stables (Fig. 9 b). An important auxiliary observation is that in these cases the arches themselves were not deformed.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Jointing | Administrative Tower

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

10a

Figure 10a

Figure 10aExamples of jointing A 88cm joint crossing two adjacent stones in the West wall (175° trending) of the Administrative Tower Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 10b

Figure 10b

Figure 10bExamples of jointing A 70cm joint crossing the lower part of a 178° trending arch support in a courtyard west of the Administrative Tower. Such joints are indication of a strong earthquake, around VII–VIII in the EMS-98 scale Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: At the western wall of the Administrative Tower, trending 178°, an 88cm long joint is seen crossing two stones (Fig.10 a). A 70cm long joint is seen at the lower support stone of a 178° trending arch, located in a room west of the Administrative Tower (Fig.10 b).- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Pushing of Walls by Connected Perpendicular Walls | Entire site | 11

Figure 11

Figure 11Both, clockwise and counterclock-wise rotations of adjacent stones in a wall, caused by a strong seismic push of a connected perpendicular wall Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: Clockwise and counterclockwise rotations of adjacent stones in a wall, caused by a push of a connected perpendicular wall (Fig. 11).- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Percentage of Heavily Damaged Buildings | Entire site | The destroyed Roman buildings were rebuilt and, thus, many of the destroyed building parts were cleared away. The large number of deformation patterns that seen in the remaining parts of the Roman period buildings makes room to the assessment that practically all houses were damaged. Thus, the intensity of the tremor was IX EMS-98 scale or more.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

|

|

Building XXV

Figure 1.64

Figure 1.64Mampsis, Building XXV, plan and photo to east Sion and Israeli (2022) |

Figure 1.66b

Figure 1.66bin situ braziers made of inverted “Gaza” wine jars found in Phase 3, 363 CE from Building XXV, Mampsis Sion and Israeli (2022)

Figure 1.67

Figure 1.67Finds from the kitchen in Phase 3 of Building XXV destroyed in the 363 CE earthquake at Mampsis Sion and Israeli (2022) |

JW: Building XXV was said to have been particularly hard hit. This building, according to

Erickson-Gini (2010:129), sustained such heavy damage that it was abandoned and never rebuilt. Room 2, apparently used as a kitchen, preserved a rich lode of pottery sealed and found in situ on the floor of the collapsed room. Some of the pottery was interpreted as having fallen from shelves in the "kitchen". Erickson-Gini (2010:80) reports that in situ coins were found in the earthquake debris in Building XXV. Erickson-Gini (2010:129) reports that the walls of adjacent Rooms 1 and 2 ("kitchen") of Building XXV were rather insubstantial additions to the original structurewhich were constructed in a shallow layer of soilwhich appears to have contributed to the collapse of the kitchen. |

- from Upper parts of buildings (repaired and built in the Byzantine Period)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tilting of Walls | S of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Entire Site |

12a

Figure 12a

Figure 12aUpper stones tilted 75° westward at a N-S (176°) trending wall, located at the west in a room south of the West Church Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 12b

Figure 12b

Figure 12bTilting westward of upper stones of the N-S (174°) trending east wall in a room south of the main premises of the West Church – stone A has a dip of 61° and stone B has a dip of 74° Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 12c

Figure 12c

Figure 12cTilting direction of the upper parts of walls of the Byzantine period, as a function of the wall directions – an overwhelming portion of the SES trending walls has been tilted to the WNW, and significantly less cases are seen in the perpendicular walls and with no direction preference Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 12d

Figure 12d

Figure 12dIndicating the seismic push arrived from SW Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: The upper row of stones of a N-S (176°) trending wall, in a room south of the West Church, is tilted westward by an angle of 75° (Fig. 12 a). The upper stones of a wall trending N-S (174°), in a room south of the premises of the West Church, are also tilted westward, in an angle of 75° (Fig. 12 b).- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Rotation of Wall Fragments around a Vertical Axis | E of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) House of Frescoes

Figure 2c

Figure 2cEast Church and House of Frescoes Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Entire Site |

13a

Figure 13a

Figure 13aExamples of rotation Clockwise rotation (on 4°) of stones in the upper part of a N-S (172°) trending wall in a room at the Late Nabatean Building Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 13b

Figure 13b

Figure 13bExamples of rotation Counterclockwise rotation (on 5°) of a part of a ENE (62°) trending wall at the House of Frescoes. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 13c

Figure 13c

Figure 13cExamples of rotation Direction and angle of rotation observed at the upper parts of walls, the Byzantine period, as a function of the trend of the walls – a clear directional preference is observable, leading to the conclusion. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 13d

Figure 13d

Figure 13dExamples of rotation Indicating the seismic push arrived from SW Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: A 4° clockwise rotation is seen in the upper part of a N-S (172°) trending wall, situated in a room of the Late Nabatean Building (Fig. 13 a). In contrast, a counterclockwise rotation of 5° is seen in part of an E-W (62°) trending wall in the House of Frescoes (Fig. 13 b).- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking of Entrances | West City Wall

Figure 2a

Figure 2aCity plan of ancient Mamshit Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) XII quarter

Figure 2c

Figure 2cEast Church and House of Frescoes Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

14a

Figure 14a

Figure 14aExamples of rebuilding Blockage by smaller stones to support a damaged entrance at the west city wall, close to the SW corner – tilted stones at the south (right) side of the entrance indicate damage (marked by dashed lines) during a previous earthquake. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 14b

Figure 14b

Figure 14bExamples of rebuilding Blocking of an entrance in the east wall of a room in the XII quarter, in order to support the lintel that was cracked (marked by arrows) at an earlier earthquake. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observation: Fig. 14 a depicts a gate in the western city wall, close to its SW corner, that was blocked by smaller stones. The wall edge is tilted towards the former entrance, disclosing that the latter was blocked in order to support the wall that was damaged, most probably by an earthquake. The blocking stones are tilted as well, possibly disclosing the impact of another earthquake. Fig. 14 b shows an entrance in the eastern wall of a room of the XII quarter that was blocked to support the lintel that was cracked (marked by arrows), most possibly during a former earthquake.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Mismatch of Lower Stone Rows and Upper Parts of Buildings | E of East Church

Figure 2c

Figure 2cEast Church and House of Frescoes Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

15

Figure 15

Figure 15Rebuilding disclosed by the protrusion of the lowest row of stones at the west wall of a room, east of the East Church (the recent restoration line is higher above – marked by arrows) Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observation: The lower row of stones of the western wall of a room, east of the East Church, protrudes from the plane of the rest of the wall (Fig. 15).- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Supporting Walls | South City Wall

Figure 2a

Figure 2aCity plan of ancient Mamshit Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

16

Figure 16

Figure 16A 66° trending section of the south city wall, tilted by 81° to SES (marked by a dashed line), supported by an added wall (shown by an arrow). Part of the support wall was dissembled during the archeological excavations, to expose the tilting of the original wall Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observation: Fig. 16 discloses a section of the southern city wall (trending 66°) that is tilted by 81° to SES (marked by a dashed line), and connected to it are seen the remains of a special support wall (shown by an arrow). Part of the support wall was dissembled during the archeological excavations, to expose the tilting of the original wall.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Secondary Use of Building Stones | East Church

Figure 2c

Figure 2cEast Church and House of Frescoes Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

17a

Figure 17a

Figure 17aExamples of secondary use of building stones Section of a column reused as part of a bench along the west wall of the main hall of the East Church. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 17b

Figure 17b

Figure 17bExamples of secondary use of building stones E wall of a room at East Church Quarter: the lower-right part protrudes 7 to 12cm, as compared to the upper-left part, that is built of reused smaller stones (the contact is marked by + signs) Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observation: Fig. 17 a shows a secondary use of a segment of a column, western wall of the main hall of the East Church. Fig. 17 b displays the eastern wall of a room at the East Church quarter, disclosing a lower- right part that protrudes 7 to 12cm, as compared to the upper-left part that is built of reused smaller stones, disclosing a stage of repair and rebuilding.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Incorporation of Wooden Beams in Stone Buildings | Administrative Tower

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

18a

Figure 18a

Figure 18aExamples of the incorporation of elastic wooden beams in stone buildings Wooden beam incorporated as second lintel above a door in a room at the Administrative Tower Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 18b

Figure 18b

Figure 18bExamples of the incorporation of elastic wooden beams in stone buildings Wooden beam incorporated at the same building between two doorsteps Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observation: A high quality wooden beam is incorporated as a second lintel above a door in a room at the Administrative Tower (Fig. 18 a). Another beam is incorporated in the same building between two door steps (Fig. 18 b).- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Bulging of Wall Parts | West City Wall

Figure 2a

Figure 2aCity plan of ancient Mamshit Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

19a

Figure 19a

Figure 19aWestward bulging of the central part of the western city wall, trending SES (152°). Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 19b

Figure 19b

Figure 19bThe angles of the displaced stones Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observation: The central part of the western city wall, trending SES (152°), is bulged westwards, as is seen in Fig. 19 in a photo and a sketch.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

| Percentage of Heavily Damaged Buildings | Entire Site | Practically all the buildings of the Byzantine period were damaged, more that 50% are estimated to have been destroyed. Thus, the intensity of the tremor was IX at the EMS-98 scale or more.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

- Fig. 20a - Seismic movement

from NWN in Early Byzantine Quake which does not match observations - from Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003)

Figure 20a

Figure 20a

Analysis of the direction of the epicenter in the devastating earthquake of the 4th cent. Systematic of expected damage patterns

a. If the seismic movement would have arrived from NWN

Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) - Fig. 20b - Seismic movement

from NEN in Early Byzantine Quake which does not match observations - from Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003)

Figure 20b

Figure 20b

Analysis of the direction of the epicenter in the devastating earthquake of the 4th cent. Systematic of expected damage patterns

b. If the epicenter would have been at NEN

Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) - Fig. 20c - Seismic movement

from N in Early Byzantine Quake which matches observations - from Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003)

Figure 20c

Figure 20c

Analysis of the direction of the epicenter in the devastating earthquake of the 4th cent. Systematic of expected damage patterns

c. If the seismic movement came from north – the case met by the observations

Korjenkov and Mazor (2003)

The Lower Parts of the Buildings, Reflecting Mainly the Earthquake of the End of the 3rd cent. or Beginning of the 4th cent.

The walls of the houses of Mamshit had a general orientation of around ENE (~ 75°) and SES (~165°). Hence, a quadrangle of these directions may serve as the basis for a general discussion of the observed damage patterns, in order to deduce the direction of arrival of the seismic movements.

Arrival of the seismic motions from north has been concluded for the 4th cent. event. Let us discuss in this context three possibilities:

- If the strong seismic pulses would have arrived from NWN, the walls perpendicular to this direction (ENE) would experience quantitative and systematic tilting (as well as collapse) toward the epicenter, whereas the perpendicular walls (SES) would have distinctly less cases of tilting and they would be in random to both NEN and NWN (Fig. 20 a). Rotations would be scarce and at random directions. This is not the case of the lower parts of buildings (Roman period) at Mamshit.

- If the strong seismic shocks would have arrived along the bisector of the trend of the walls (i.e. from NEN), the walls trending ENE would have undergone both systematic tilting toward NWN and anticlockwise rotation, whereas the perpendicular walls (trending SES) would experience systematic tilting toward NEN and clockwise rotation (Fig. 20 b), but this is not the case of the lower parts of buildings (Roman period) at Mamshit.

- If the epicenter was at the north, the ENE trending walls would undergo systematic tilting to the NWN and systematic counterclockwise rotations, whereas the SES trending walls would suffer of a few cases of random tilting but systematic clockwise rotations (Fig. 20 c). This combination of damage pattern orientations fits the observations at the lower parts of the buildings at Mamshit, leading to the conclusion that the epicenter of the devastating earthquake at the end of the 3rd cent. or beginning of the 4th cent. was north of Mamshit.

- Fig. 21a - Seismic movement

from WSW in 2nd Earthquake which does not match observations - from Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003)

Figure 21a

Figure 21a

Analysis of the direction of the epicenter in the devastating earthquake of the 7th cent. Systematic of expected damage patterns

a. If the epicenter would be at WSW

Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) - Fig. 21b - Seismic movement

from NEN in 2nd Earthquake which does not match observations - from Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003)

Figure 21b

Figure 21b

Analysis of the direction of the epicenter in the devastating earthquake of the 7th cent. Systematic of expected damage patterns

b. If the seismic waves would have come from NEN

Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) - Fig. 21c - Seismic movement

from SW in 2nd Earthquake which matches observations - from Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003)

Figure 21c

Figure 21c

Analysis of the direction of the epicenter in the devastating earthquake of the 7th cent. Systematic of expected damage patterns

c. If the seismic movement came from SW – the case met by the observations

Korjenkov and Mazor (2003)

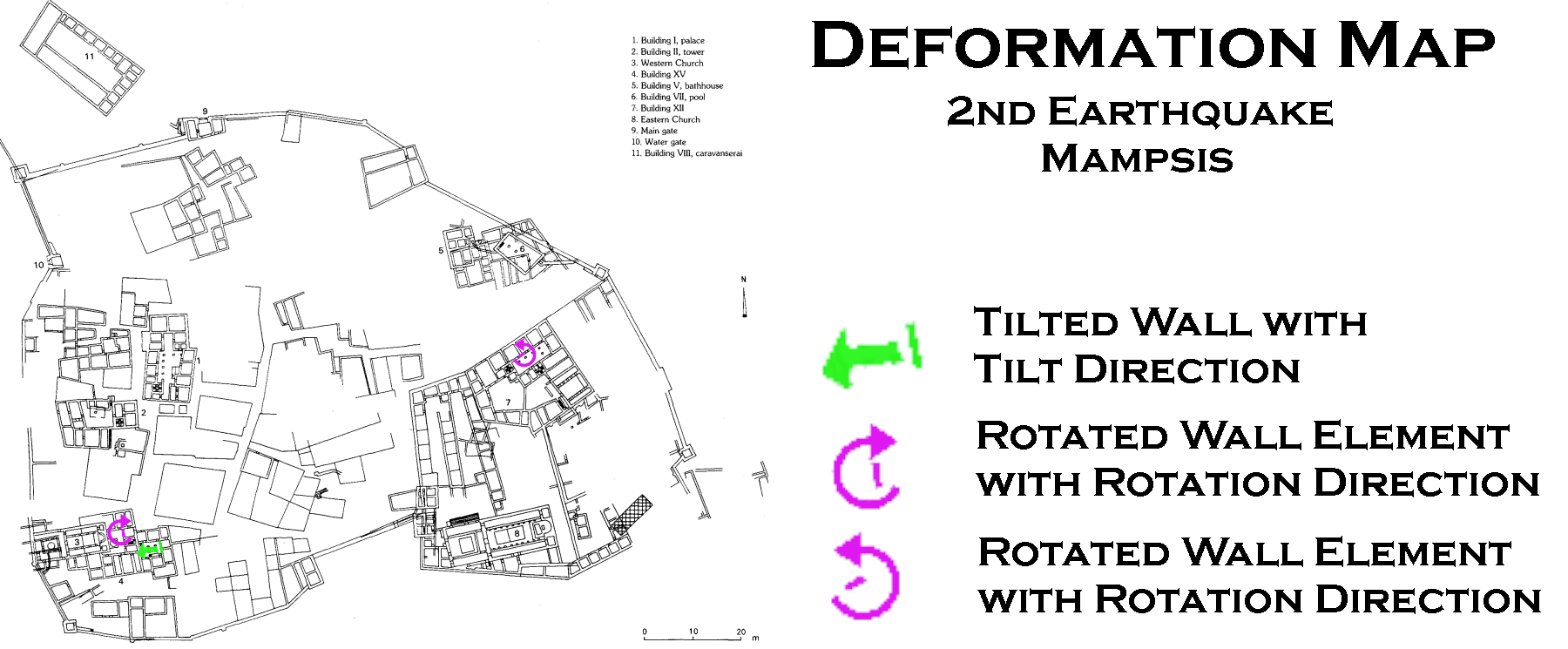

The Upper Parts of the Buildings, Reflecting Mainly the 7th cent. Earthquake [JW: 5th -7th centuries CE ?]

The direction of the epicenter of the 7th cent. strong earthquake has been concluded to have been SW of Mamshit. In this connection let us examine three possibilities, bearing in mind that the walls of the houses of Mamshit had a general orientation of around ENE (~ 75°) and SES (~165°):

- If the strong seismic shocks would have arrived from WSW, the walls perpendicular to this direction (SES) would experience quantitative and systematic tilting toward the epicenter, whereas the perpendicular walls (ENE) would have distinctly less cases of tilting and they would be in random directions and not to the epicenter (Fig. 21 a). Rotations would be scarce and at random directions. This is not the case of the upper parts of buildings (Byzantine period) at Mamshit.

- If the strong seismic pulses would have arrived along the bisector of the trend of the walls (i.e. from SWS), the walls trending ENE would have under¬gone both systematic tilting toward NWN and counterclockwise rotation, whereas the perpendicular walls (trending SES) would experience systematic tilting toward NEN and clockwise rotation (Fig. 21 b), but this is not the case of the upper parts of buildings (Byzantine period) at Mamshit.

- If the epicenter was at SW, the SES trending walls would undergo systematic tilting to the SW and systematic clockwise rotations, whereas the ENE trending walls would suffer of a few cases of random tilting but systematic counterclockwise rotations (Fig. 21 c). This combination of damage pattern orientations fits the observations at the upper parts of the buildings at Mamshit, leading to the conclusion that the epicenter of the devastating seventh century earthquake was SW of Mamshit.

- Modified by JW from Plan 1 of Negev (1988b)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Plan 1 of Negev (1988b)

- Modified by JW from Mampsis site plan in Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Mampsis site plan in Stern et. al. (1993 v.3)

- from Lower parts of buildings (built in Nabatean and Roman Periods)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE) chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Tilting of Walls | E of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Entire Site |

3a

Figure 3a

Figure 3aTilted walls. South side of the north wall of a room east of the west Church, the wall has a trend of 86° and the average inclination is 79°. Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 3b

Figure 3b

Figure 3bTilted walls. North side of the same wall, the lower stone rows are tilted northward by up to 60° Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 3c

Figure 3c

Figure 3cTilted walls. Summary of measurements: direction of tilting patterns observed at the lower parts of walls at Mamshit (Tab. 1), as a function of the direction of the walls, revealing that out of 30 cases of walls trending ENE (55° to 105°), 26 were found to be tilted northward, 180 and only 4 cases are tilted southward, whereas the perpendicular walls (trending 145° to 185°) show only 9 tilting cases with no preferred direction Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) 3d

Figure 3d

Figure 3dTilted walls. Stress directions concluded from the observed tilting patterns Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: tilted walls or wall segments (Figs. 3 a. b). By convention, the direction of tilting is defined by the direction pointed by the upper part of the tilted segment. Only cases of tilting of most of the wall were included in this study.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

VI+ |

| Lateral Shifting of Building Elements (displaced masonry blocks) | E of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

4

Figure 4

Figure 4Lower stone of a N-S trending (175°) arch, shifted 8cm northward (the original position is marked by dashed lines). This is the fourth arch of the eastern line of fodder-basins of the Stables. The lowest stone of the arch has been severely cracked during the seismically caused shifting Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) |

Observed damage pattern: northward shifting by 8 cm, as well as severe cracking of the lowest stone in a 175° trending arch (Fig.4). Thus, a large building element was shifted, and in addition slightly rotated clockwise. The location is at the eastern line of fodder-basins of a complex of stables, at a residential quarter east of the West Church.- Korzhenkov and Mazor (2003) |

VIII+ |

| Rotation of Wall Fragments around a Vertical Axis (displaced masonry blocks) | ENE of West Church

Figure 2b

Figure 2bThe West Church and Administrative Tower Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Near Frescoes House

Figure 2c

Figure 2cEast Church and House of Frescoes Quarters Roman numbers denote residential quarters Arabic numbers the location of Figures Korjenkov and Mazor (2003) Entire Site |

5a

Figure 5a