Yotvata

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Aerial view of the [Roman] fort, with east at the top.

Davies and Magness (2015)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Yotvata | Hebrew | יׇטְבָתָה |

| Iutfata | Arabic | يوتفاتا |

| Ein Ghadian | Arabic | يين عهاديان |

Yotvata is located in a small oasis about 40 km. north of

Eilat. The modern name Yotvata is based on

Jotbathah, one of the stops of the Israelites in the

journey of the Exodus (Deuteronomy 10:7 and

Numbers 33:33-34). There is as yet no

proof for this identification (Zeev Meshel in Stern et al, 1993).

Due to Yotvata's water source and location at a crossroad, it has been settled during different periods although

there is no mound or multiperiod central site

(Zeev Meshel in Stern et al, 1993).

Yotvata is the modern name of a small oasis located on the western edge of the southern Arabah on the main road to Elath, about 40 km (25 mi.) north of the city (map reference 155.923). Before the establishment of the state of lsrael in 1948, the oasis consisted mainly of a few shallow pits, from which the upper groundwater ran, and a small grove of tamarisks and date palms. In Arabic it was called 'Ein Ghadian, probably after the haloxylon bush (ghada in Arabic), commonly found in the surrounding sands. Another possibility is that the Arabic name is derived from ad-Dianam, possibly the site's name in the Roman period (see below). Today Kibbutz Yotvata, a regional center, and a road station stand on the site.

The modern name Yotvata is based on the site's possible identification of the oasis with "Jotbathah, a land with brooks of water" (Dt. 10:7), one of the Israelites' encampments in their desert wanderings, before Ebronah and Ezion-Geber (Num. 33:33-34). There is as yet no proof for this identification; some scholars have suggested the Israelites' route here ran from north to south and have found support for this hypothesis in the Arabic names Sabkhat et-Taba and Bir et-Taba of the Yotvata saline marshes (today bisected by the Israel-Jordan border) and the well on their eastern edge.

The water source and the crossroad here made Yotvata a focus for settlement at different periods, and although there is no mound or multiperiod central site, there are a number of sites in different places. Their remains can be divided into four main groups:

- remains related to water or agriculture

- tombs

- remains of settlements or encampments

- remains associated with copper production

The settlements excavated so far date to the Chalcolithic period, the Early and Middle Bronze Ages, the beginning of the Iron Age, and the Nabatean, Roman, and Early Arab periods. The sites from the last four periods were probably fortresses or way stations.

Two of the sites at the oasis were briefly described in the early twentieth century. The large "mother well" (today by the side of the road north ofYotvata) was described by A. Musil, who called it Hafriat Ghadian and correlated it with the water supply. T. E. Lawrence described the Roman fortress (but mistakenly dated it to the Byzantine period). In the early 1930s, F. Frank and N. Glueck described the aforementioned Hafriat Ghadian, the phenomenon of the chain wells, and the Roman fortress, which Frank correctly identified as a Roman castellum and Glueck believed to be a Nabatean khan. Glueck returned to Yotvata in the 1950s and investigated the early Iron Age fortress discovered by kibbutz members. He erroneously identified it as belonging to the series of Negev fortresses "from the time of King Solomon." Y. Aharoni surveyed the site in the 1950s and was the first to describe the Early Arab period site (which he identified as Roman-Byzantine), and Evenari's team carried out the first extensive survey of the chain wells systems. In the following years, B. Rothenberg surveyed the area as part of his Arabah Survey, but he was unable to establish the exact dates of some of the sites. Partial surveys were later undertaken by U. Avner, Z. Meshel, and Y. Porath. Porath also carried out a short trial excavation at the site which is considered to be the oasis's central settlement in the Roman-Nabatean period (map reference 1543.9214). The main structure here (c. 30 by 35m) has a central courtyard and parts of it are built of ashlars. Only further excavation will confirm whether this is another fortress in the series found at the oasis or a ritual structure, possibly a temple, which, according to the Roman Tabula Peutingeriana, could have stood here.

Since 1974, excavations have been carried out (at the sites described below) on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University, as part of a research project on the history of the Yotvata oasis. The excavations are under the direction of Z. Meshel and co-directed by B. Sass and E. Ayalon.

- Fig. 2.1 Map of Yotvata and

environs from Singer-Avitz and Ayalon(2019)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Map of the surveyed roads in the Eilat region - most sites are Nabatean-Roman but the same roads were used in all periods

(adapted from Fig. 1 in Avner, 2108)

Singer-Avitz and Ayalon (2019) - Yotvata environs in Google Earth

- Yotvata environs on govmap.gov.il

- Roman Fort at Yotvata in Google Earth

- Roman Fort at Yotvata on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 2 Aerial view of the

Arava Valley with the Yotvata fort in the foreground from Davies and Magness (2015)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Aerial view of the Arava Valley, looking north, with the Yotvata fort in the foreground.

Davies and Magness (2015) - Fig. 3.1 Yotvata Hill where

the Iron I fortress is located from Singer-Avitz and Ayalon(2019)

Fig. 3.1

Fig. 3.1

Yotvata Hill, looking northwest

(photo Uzi Avner)

Singer-Avitz and Ayalon (2019)

- Fig. 3.2 Plan of Yotvata Hill

from Singer-Avitz and Ayalon(2019)

Fig. 3.2

Fig. 3.2

Plan of Yotvata Hill:

- Iron I casemate wall

- earthen rampart

- section in earthen rampart

- Nabataean built tomb

- Early Islamic building

Singer-Avitz and Ayalon (2019) - Fig. 3.2 Aerial photograph of

Yotvata Hill from Singer-Avitz (2019)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Aerial photograph of Givat Yotvata (Yotvata Hill):

- fence wall (Yotvata Hill)

- dirt embankment

- cut in the dirt embankment

- Nabataean tomb structure

- a building from the Early Islamic period

(Photo: Uzi Avner)

Singer-Avitz (2019) - Plan of the "castle" from

Iron Age I - from Singer-Avitz (2019)

Plan of the "castle" from Iron Age I

Plan of the "castle" from Iron Age I

Singer-Avitz (2019) - Fig. 4 Plan of Nabatean

structure from Erickson-Gini (2012a)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Plan

Erickson-Gini (2012a) - Fig. 5 Plan of the Roman

fortress from Davies and Magness (2015)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Plan of the fort, indicating the excavation area and room numbers.

Davies and Magness (2015) - Plan of the Early Arab

structure in its main phase from Stern et. al. (1993 v.4)

Plan of the main Early Arab structure in its main phase

Plan of the main Early Arab structure in its main phase

Stern et. al. (1993 v.4)

- Plan of the "castle" from

Iron Age I - from Singer-Avitz (2019)

Plan of the "castle" from Iron Age I

Plan of the "castle" from Iron Age I

Singer-Avitz (2019) - Fig. 4 Plan of Nabatean

structure from Erickson-Gini (2012a)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Plan

Erickson-Gini (2012a)

- Fig. 3.16 Fragmented storage

jars in Casemate Room 20A of Iron Age Fortress on Yotvata Hill from Singer-Avitz and Ayalon(2019)

Fig. 3.16

Fig. 3.16

Fragmented storage jars in Casemate Room 20A, looking south

Singer-Avitz and Ayalon (2019)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

Singer-Avitz (2023:168-169) report that the Iron I "fortress" at Yotvata was violently destroyed.

They concluded this based on evidence of fire in many of the casemate rooms in the short-lived

settlement of Yotvata, as well as the recovery of complete pottery vessels within them

.

Singer-Avitz (2023:170) concluded that the site was probably short-lived, and it

can be assumed that it did not exist until the end of the Iron Age I, i.e., beyond the mid-11th century.

The suggested that the Yotvata "fortress" was built only in the early Iron I

.

Singer-Avitz (2023:166) reports that the method used for dating the Yotvata "fortress" is based

upon pottery typology and a comparison of material culture of various sites to create a cultural-chronological horizon.

- Fig. 4 - Plan of Nabatean structure

from Erickson-Gini (2012a)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Plan

Erickson-Gini (2012a) - Fig. 7 - Aqaba Ware jar, crushed in situ

from Erickson-Gini (2012a)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Aqaba Ware jar, crushed in situ, looking north.

Erickson-Gini (2012a) - Fig. 8 - Collapsed ceiling slabs

from Erickson-Gini (2012a)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Upright, collapsed ceiling slabs (F2), looking north

Erickson-Gini (2012a)

Erickson-Gini (2012a) report archaeoseismic evidence in a Nabatean structure at 'En Yotvata

Three walls of a structure (W1–W3; Fig. 4) were revealed during the 2005 season. The walls were constructed from hard limestone blocks (average size 0.25×0.35 m). The only complete wall was W2 in the west, oriented north–south (length 12.5 m), which was preserved to at least two courses high above the surface. A possible entrance is indicated along this wall, slightly west of its center. The other two walls appear to have been of the same length. The structure had entirely collapsed in the earthquake of the early second century CE.

... The structure, which was apparently a two-story building, appears to have been stripped for building stones, probably after the earthquake destruction. In the collapse of the upper storey (L100, L500, L600), potsherds dating to Late Hellenistic period were discovered, including painted fine-ware bowls (Fig. 5:1, 3, 4), a bowl of the fish-plate tradition (Fig. 5:9), as well as painted fine-ware bowls of the Early Roman period (Fig. 5:5–7). Large fragments of a fine-ware painted bowl of the second half of the first century CE were discovered, in situ, in the middle of the building (L100; Fig. 5:8).

... A group of collapsed stone ceiling slabs (F2), standing nearly upright, was uncovered in the middle of the L601 square (Fig. 8)

... The building was apparently destroyed in an earthquake in the early second century CE. Evidence of this disaster could be seen in the collapsed upper floor in both squares, the collapsed ceiling slabs and in the collapse of the structure’s exterior walls. In addition, parts of the same Nabataean Aqaba Ware jar, found in the last season, were discovered deep in L502, somewhere above the surface of the lower floor. The coins recovered from the debris of the upper floor are Nabataean coins of the first century CE. The pottery assemblage includes forms of the earliest Nabataean painted wares of the Late Hellenistic period, Nabataean painted ware bowls of the Early Roman period, and plain ware Nabataean vessels, spanning the Late Hellenistic and Early Roman periods. The latest datable pottery vessels discovered in the structure are the Nabataean Aqaba Ware jars, dated to the early second century CE.

Fig. 7

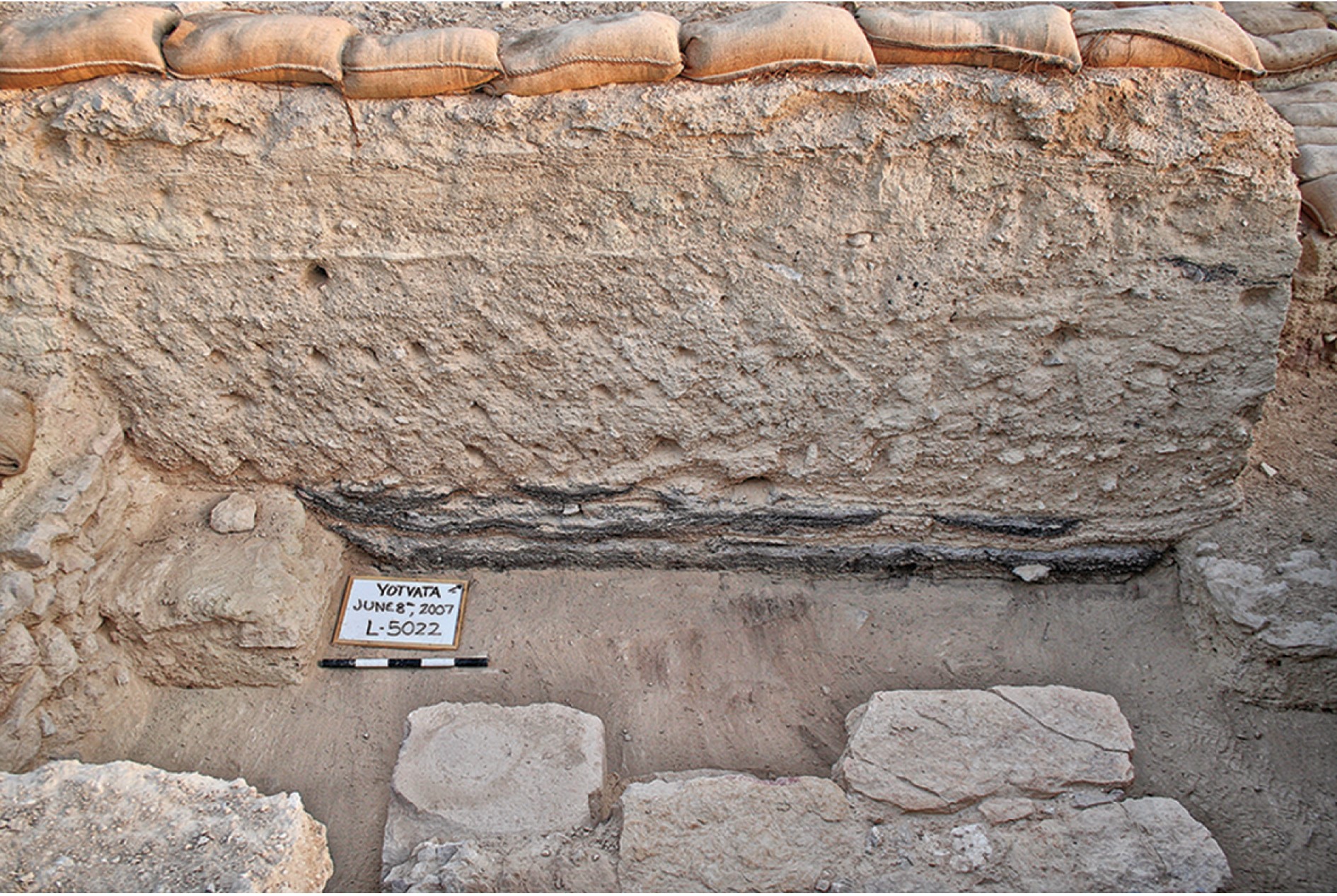

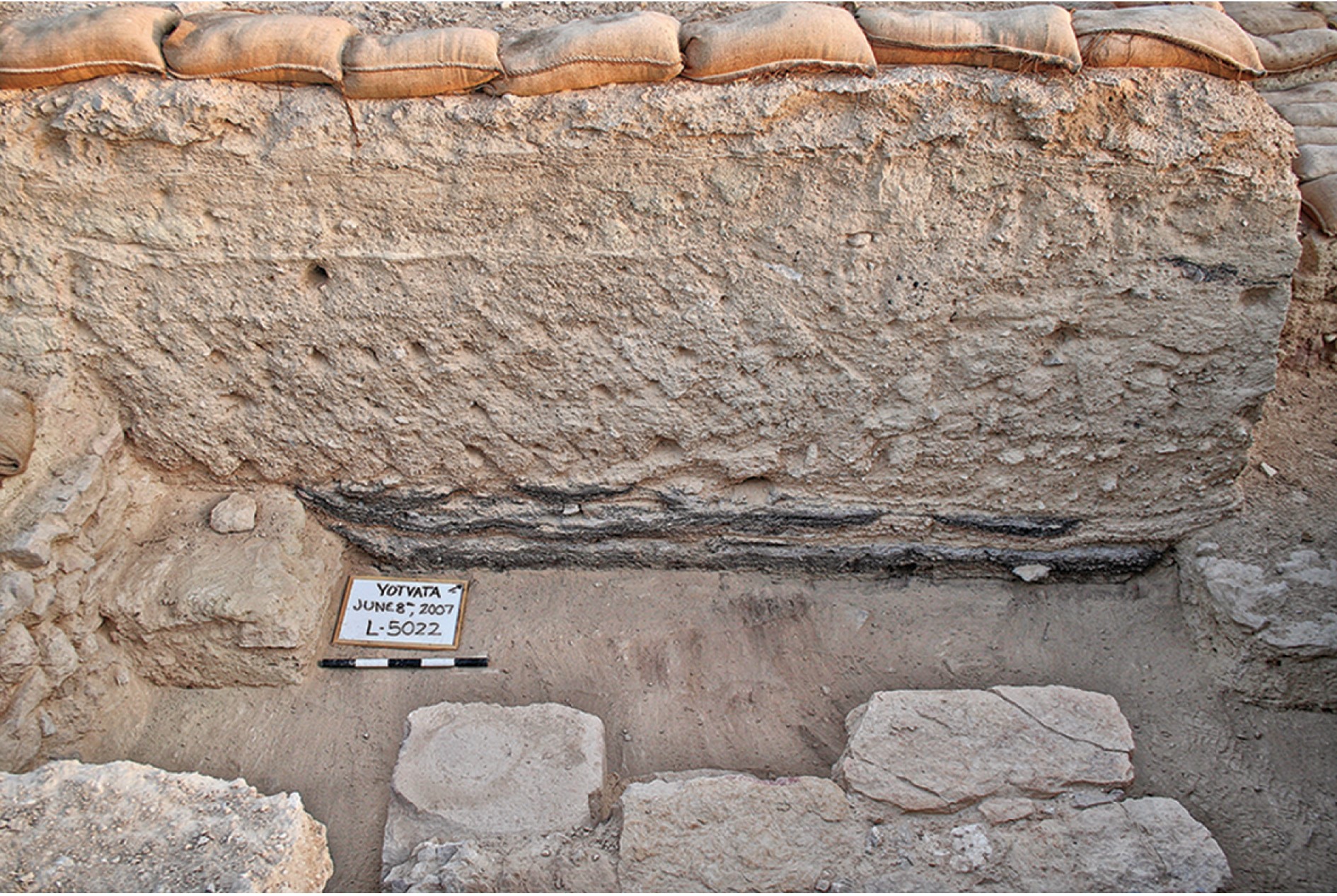

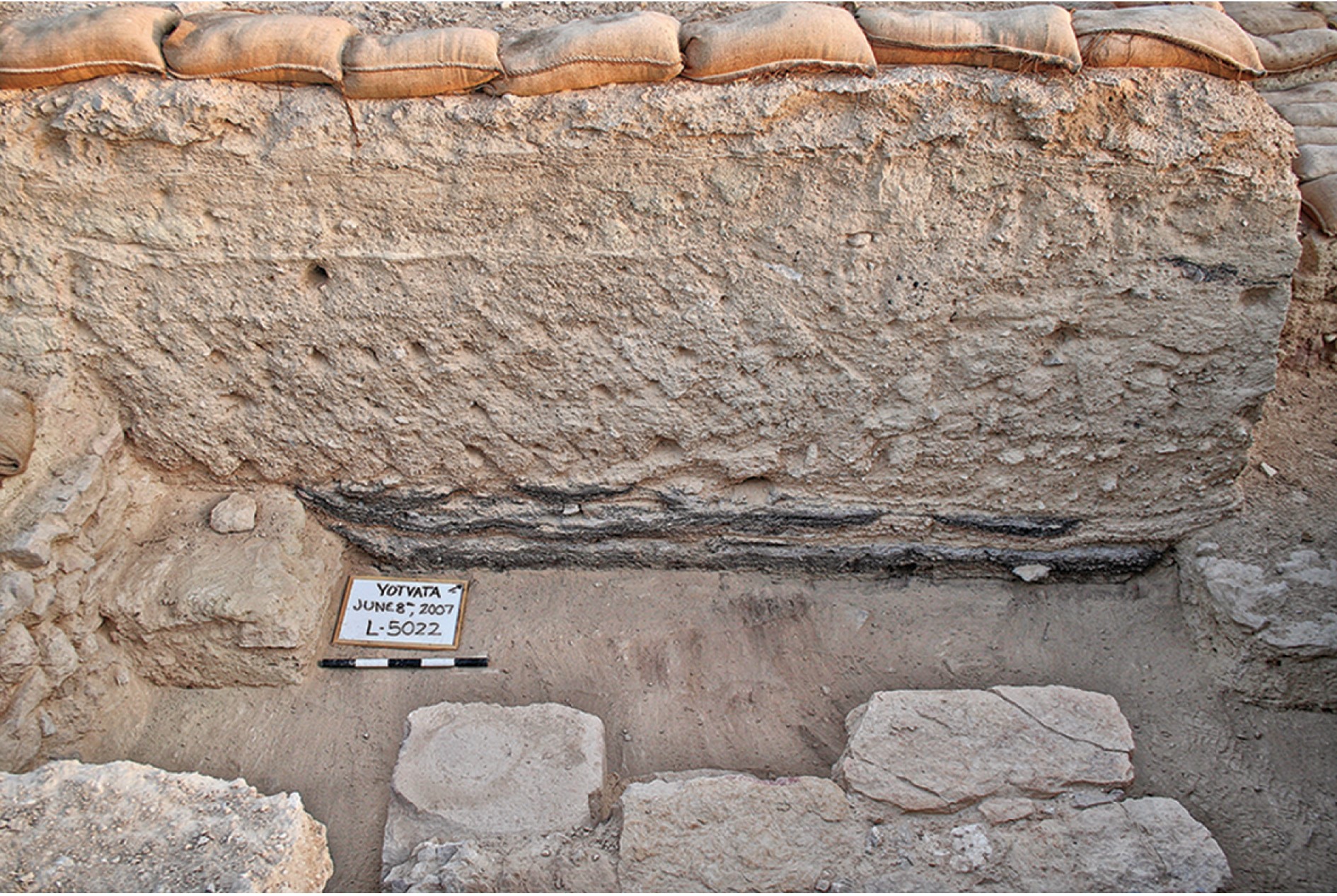

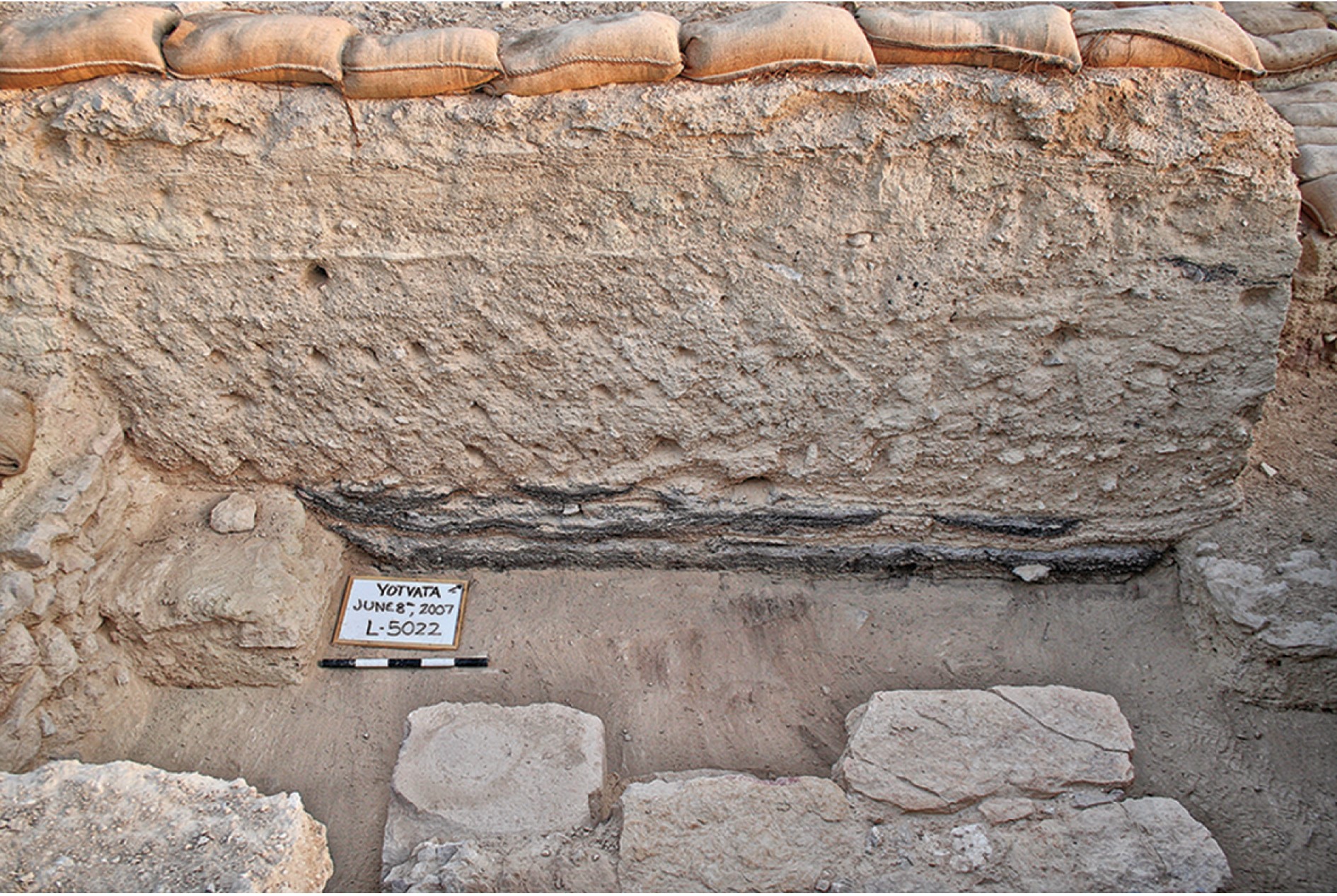

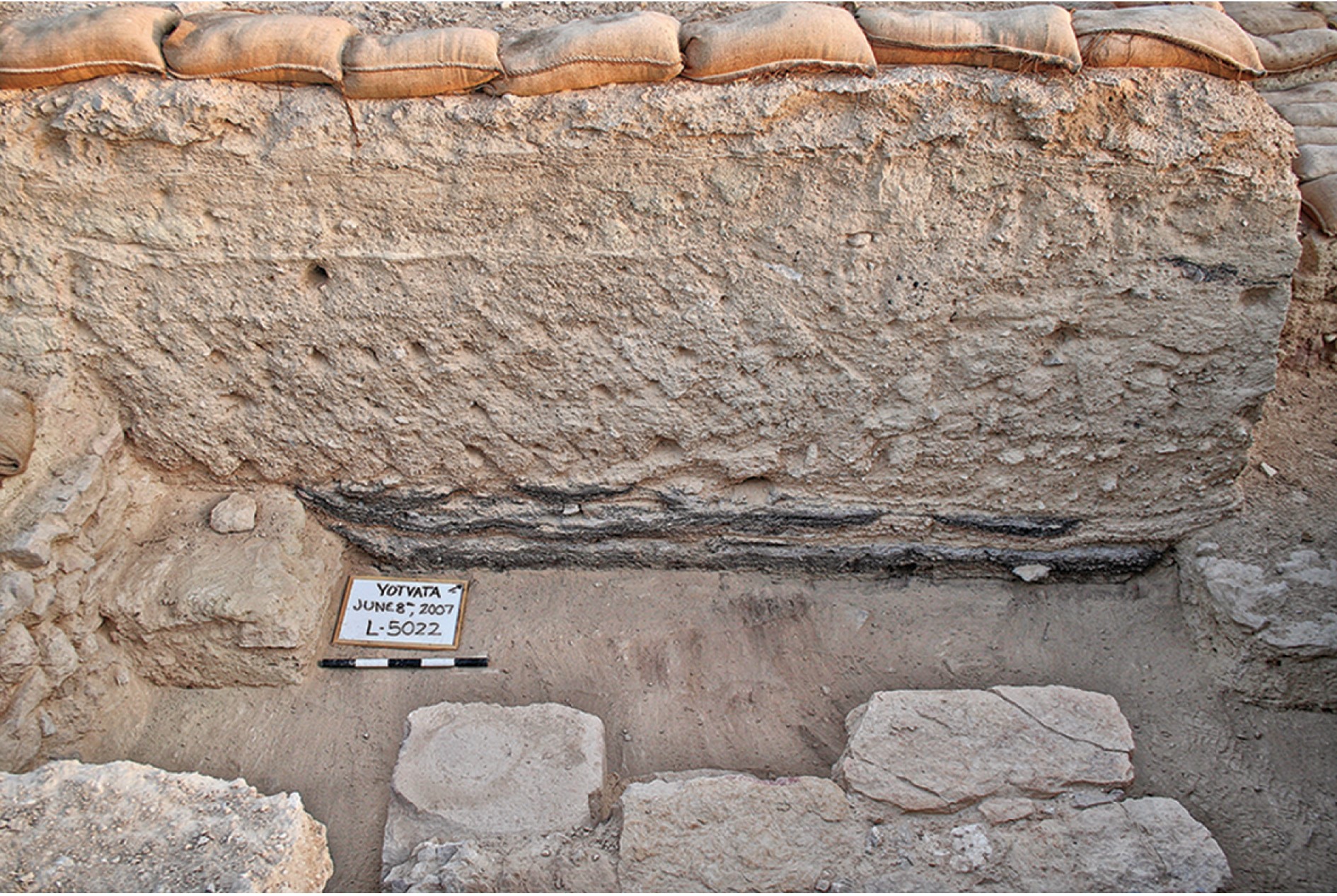

Fig. 7West baulk of Room 4, showing the mud-brick collapse

JW: Stratigraphy of Yotvata - burnt layer at bottom is overlain by mud brick collapse layer and sedimentation until the top Early Islamic layer

Davies and Magness (2015)

Davies et al (2015) excavated a Roman Fort at Yotvata from 2003-2007. A monumental Latin inscription discovered earlier (1985) outside of the east gate

suggests that the fort at Yotvata was built when Diocletian transferred the Tenth Legion Fretensis from Jerusalem to Aila in the last decade of the third century.Two destruction layers were described after establishment of the fort - a burned layer and a collapse layer. The authors noted that

the first phase of Roman occupation at our fort, which is associated with coins that go up to ca. 360, ended with a violent destruction evidenced by intense burning throughout.Reconstruction is said to have occurred immediately after this destruction as documented by a

series of successive floor layers throughout. The cause of the burned layer was not established but the authors suggested a

a possible connection with the Saracen revolt against Rome led by Queen Mavia, ca. 375–378noting the documented successes of her forces against Roman field armies and that

the inclusion of former foederati among her troops suggest that her forces would have been capable of taking and destroying the fort at Yotvata.Whatever the specific cause, the excavators strongly believed that human agency rather than the southern Cyril Quake of 363 AD was the general cause noting that there was no visible evidence of structural damage or a collapse layer. One of the excavators, Gwyn Davies (personal communication, 2020) noted that

We are confident that the fort was destroyed in a violent attack as we encountered signs of intense burning across most contexts and, even more suggestively, the stone frame of the main gate was fire-seared as well. If the fire had been more localized and associated with signs of toppling collapse, then ‘natural causes’ may have been more persuasive or, indeed, that this represented an accidental destruction. Instead, the evidence suggests to us that the fort was put to the torch quite deliberatelyAnother of the excavators, Jodi Magness (personal communication, 2020) related the following

In addition to the lack of evidence of visible structural damage that could be attributed to an earthquake in the earliest destruction level, the absence of whole (restorable) pottery vessels and other objects in that level suggests an earthquake did not cause the destruction, as one would expect these artifacts to be buried in a sudden collapse. Therefore, we attributed the destruction by fire to human agents.As for the collapse layer, it is dated to after the abandonment of the fort in the late 4th century.

The Late Roman occupation ended with an orderly evacuation and abandonment, as indicated by the fact that the rooms were cleared out. The absence of a reference to a fort at Osia [i.e. the fort excavated near Yotvata] in the Notitia Dignitatum, together with a reference to the ala Constantiana being stationed at Toloha (Or. 34.34), ca. 110 km to the north of Yotvata, suggest that our fort was abandoned by the early fifth century. Soon thereafter an earthquake—perhaps the earthquake of 419—toppled the walls of the fort. An ephemeral Byzantine period occupation was established on top of the collapse, without any attempt at leveling.A limited amount of debris between the fort's presumed abandonment and the collapse layer led the authors to suggest the Monaxius and Plinta Earthquake of 419 AD as a possible cause of the collapse layer. Although the ensuing ephemeral Byzantine period occupation was undated due to a lack of recovered pottery, significant sediment accumulated between the Byzantine layer and the well dated Early Islamic layer suggesting that these two layers are

a century or two apart. This eliminates several potential local earthquake candidates - e.g. the Inscription at Areopolis Quake (late 6th century), the Sign of the Prophet Quake (613-622 CE), and the Sword in the Sky Quake (634 CE). Archeoseismic evidence at Yotvata for the 419 CE Monaxius and Plinta earthquake should be considered as possible to probable. The excavators say possible and I say possible to probable.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Exterior Walls and Ceiling slabs | Upper Storey - Loci L100, L500, and L600

Figure 4

Figure 4Plan Erickson-Gini (2012a) |

Figure 8

Figure 8Upright, collapsed ceiling slabs (F2), looking north Erickson-Gini (2012a) |

|

| Crushed pottery | deep in L502

Figure 4

Figure 4Plan Erickson-Gini (2012a) |

Figure 7

Figure 7Aqaba Ware jar, crushed in situ, looking north. Erickson-Gini (2012a) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Entire fortress ?

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the fort, indicating the excavation area and room numbers. Davies and Magness (2015) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 7West baulk of Room 4, showing the mud-brick collapse JW: Stratigraphy of Yotvata - burnt layer at bottom is overlain by mud brick collapse layer and sedimentation until the top Early Islamic layer Davies and Magness (2015) |

|

| Toppled Steps | Southwest Staircase

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the fort, indicating the excavation area and room numbers. Davies and Magness (2015) |

Fig. 9

Fig. 9Southwest staircase showing toppled steps, looking east Davies and Magness (2015) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 4 of Erickson-Gini (2012a)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 4 of Erickson-Gini (2012a)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Exterior Walls and Ceiling slabs | Upper Storey - Loci L100, L500, and L600

Figure 4

Figure 4Plan Erickson-Gini (2012a) |

Figure 8

Figure 8Upright, collapsed ceiling slabs (F2), looking north Erickson-Gini (2012a) |

|

VIII + |

| Crushed pottery | deep in L502

Figure 4

Figure 4Plan Erickson-Gini (2012a) |

Figure 7

Figure 7Aqaba Ware jar, crushed in situ, looking north. Erickson-Gini (2012a) |

|

VII + |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Entire fortress ?

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the fort, indicating the excavation area and room numbers. Davies and Magness (2015) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 7West baulk of Room 4, showing the mud-brick collapse JW: Stratigraphy of Yotvata - burnt layer at bottom is overlain by mud brick collapse layer and sedimentation until the top Early Islamic layer Davies and Magness (2015) |

|

VIII + |

| Toppled Steps | Southwest Staircase

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Plan of the fort, indicating the excavation area and room numbers. Davies and Magness (2015) |

Fig. 9

Fig. 9Southwest staircase showing toppled steps, looking east Davies and Magness (2015) |

|

VIII + |

Erickson-Gini, Tali (2012), En Yotvata, Hadashot Arkheologiyot, v. 124

Hamai, Y. (2016), Yotvata Final Report, Hadashot Arkheologiyot, v. 128

Porath Y. 1987. Qanats in the ‘Aravah. Qadmoniot 79–80:106–114 (Hebrew).

Porath Y. 2016. Tunnel-Well (Qanat) Systems from the Early Islamic Period

in the ‘Arava. ʽAtiqot 86:1*–81* (Hebrew; English sumary, pp. 113–116).

Singer-Avitz, L (2019) The Iron Age I Yotvata “Fortress” Qadmoniot 52 (157): 18-24 (Hebrew)

Z. Meshel, IEJ 39 (1989), 228-238; I. Roll, ibid., 239-260

A. Kindler, ibid., 261-266.

N. Glueck, AASOR 15 (1934-

1935), 40-41; 18-19 (1939), 95; id., BASOR

145 (1957), 23-24

Z. Meshel and B. Sass, IEJ

24 (1974), 273-274; id., RB 84 (1977), 266-270

J. Kalsbeek and G. London, BASOR 232 (1978),

47-56

G. Avniand U. Dahari, ES/5 (1986), 115

Weippert 1988, 326.

W. Eck, Klio 74 (1992), 395–400

Z. Meshel, IEJ 47 (1997), 295–297

U. Avner (& J. Magness), BASOR 310

(1998), 39–57; id. et al., IEJ 54 (2004), 256–261; id., Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für

Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 10 (2004), 198–199; id., JRA 17 (2004), 405–412

T. Haettner

Blomquist, Gates and Gods: Cults in the City Gates of Iron Age Palestine:

An Investigation of the Archaeological and Biblical Sources (Coniectanea Biblica: Old Testament Series 46), Stockholm 1999, 106–107

M. Bietak & K. Kopetzky, Synchronisation, Wien 2000, 124

J. Magness et al., ASOR Annual Meeting 2004,

www.asor.org/AM/am.htm

G. Davies & J. Magness, IEJ 55 (2005), 227–230.