Khirbet Tannur

APAAME

- Reference: APAAME_20141019_DLK-0146.jpg

- Photographer: ?

- Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

- Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

Click on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Khirbet et-Tannur | Arabic | خربة التنور |

- Russian Nesting Dolls

Russian Nesting Dolls (aka Matryoshka dolls)

Russian Nesting Dolls (aka Matryoshka dolls)

© BrokenSphere / Wikimedia Commons

is close to the King's Highway and is 7 km (4 mi.) north of another temple, Khirbet edh-Dharih, in Wadi La'ban(Marie-Jeanne Roche in Meyers et. al., 1997). Khirbet edh-Dharih is apparently architecturally and stylistically similar to Khirbet Tannur but is better dated which can help sort Khirbet Tannur chronology.

Khirbet et-Tannur is situated on top of Jebel et-Tannur in Jordan (550 m above sea level, map reference 217.042). It is an isolated mountain between Wadi el-Hesa (Zared) and Wadi el-'Aban. The site is approached from the southeast by a single path with ancient banking that is cut in the rock. It may also have had a flight of steps in its upper part. The top of Jebel et-Tannur is fairly flat. The temple, situated on the east side, is the only building on it.

In 1937, excavations were carried out at the site by a joint expedition of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the Jordan Department of Antiquities, under the direction of N. Glueck. Several outside rooms and walls remained unexcavated.

- Fig. 2 - Location Map

from Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map showing the location of Khirbet et-Tannur, other Nabataean sites, and the King’s Highway

Whiting and Wellman (2016) - Location Map from Meyers et al (1997)

Wadi el-Hasa

Wadi el-Hasa

Map of Wadi el-Hasa Archaeological Survey territory

(Courtesy B. MacDonald

Meyers et al (1997)

- Fig. 2 - Location Map

from Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Map showing the location of Khirbet et-Tannur, other Nabataean sites, and the King’s Highway

Whiting and Wellman (2016) - Location Map from Meyers et al (1997)

Wadi el-Hasa

Wadi el-Hasa

Map of Wadi el-Hasa Archaeological Survey territory

(Courtesy B. MacDonald

Meyers et al (1997)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Khirbet

Tannur from Meyers et. al. (1997)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Plan of the site

Courtesy ASOR/Nelson Glueck Archive—Semitic Museum, Harvard University

Meyers et. al. (1997) - Fig. 6.4 - Plan of Khirbet

Tannur from McKenzie et al (2013)

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4

Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal

Mckenzie et al (2013) - Fig. 1 - Axonometric reconstruction

of Khirbet Tannur from Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction

(Sheila Gibson)

Whiting and Wellman (2016) - Fig. 54 - Axonometric reconstruction

of Inner Temple of Khirbet Tannur from Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54

Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform

(Sheila Gibson)

Whiting and Wellman (2016)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of Khirbet

Tannur from Meyers et. al. (1997)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Plan of the site

Courtesy ASOR/Nelson Glueck Archive—Semitic Museum, Harvard University

Meyers et. al. (1997) - Fig. 6.4 - Plan of Khirbet

Tannur from McKenzie et al (2013)

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4

Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal

Mckenzie et al (2013) - Fig. 1 - Axonometric reconstruction

of Khirbet Tannur from Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction

(Sheila Gibson)

Whiting and Wellman (2016) - Fig. 54 - Axonometric reconstruction

of Inner Temple of Khirbet Tannur from Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54

Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform

(Sheila Gibson)

Whiting and Wellman (2016)

- Plate 112a - Inclined Wall

from Glueck (1965)

Plate 112a

Plate 112a

Sub-II pavement laid against base of north side of Altar-Pedestal of Period I

Glueck (1965)

As the Temple at Khirbet Tannur was built in a seismically active area, it is thought that most rebuilding episodes were initiated soon after earthquakes damaged parts of the Temple. Glueck (1965:128) and Glueck (1965:138) identified three separate building phases (Periods I, II, and III) and a post-Temple Byzantine squatter occupation. McKenzie et al (2013) redated Periods I, II, and III utilizing an improved understanding of the chronology that can be derived from pottery as well as comparison to other excavated sites in the region. Both Glueck (1965:138) and McKenzie et al (2013) anchored their chronology to the start of Period II which was then extrapolated to starting dates for Periods I and III. Glueck (1965:138) dated the start of Period II to the last quarter of the 1st century BCE based on a dedicatory inscription found during excavations. The inscription created a terminus ante quem of 8/7 BCE as it referred to the second year of a Nabatean King whose wife was named Huldu. This would refer to Aretas IV whose first wife was Huldu and whose reign began in 9 BCE. McKenzie et al (2002:50), however, noticed that the the inscription was not found in situ and that a bowl found underneath paving stones that were put in place soon before Period II construction dates to the late first century CE along with two other bowls which date to the first half of the second century CE. This pottery and comparison to other sites led them to date Period II construction to the first half of the second century CE. McKenzie et al (2013:72) considered it likely that the inscription with a 7/8 BCE date referred to the Period I Temple rather than the Period II Temple as was assumed by Glueck (1965:138). It is unclear why McKenzie et al (2013) date initial Nabatean worship at the site to the late 2nd century BCE if the inscription suggests that Period I construction began shortly before 8/7 BCE. Perhaps initial worship at the site preceded construction of surviving structures. McKenzie et al (2013)'s dates are used in the phasing table.

- from McKenzie et al (2013)

- Glueck's (1965) original dates and observations are included in the Comments for reference

| Period | Start Date | End Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Late 2nd century BCE | 1st half of 2nd century CE |

|

| II | 1st half of 2nd century CE | 3rd century CE |

|

| III | 3rd century CE | 363 CE |

|

| Byzantine | 363 CE | 634 CE ? |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Period I Altar

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

Plate 112a

Plate 112aSub-II pavement laid against base of north side of Altar-Pedestal of Period I Glueck (1965) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ornate pylon of the east facade of the raised inner temple enclosure

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

|

|

|

Period II altar near the northeast corner of the forecourt

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

colonnades of the Court

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

various locations

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

|

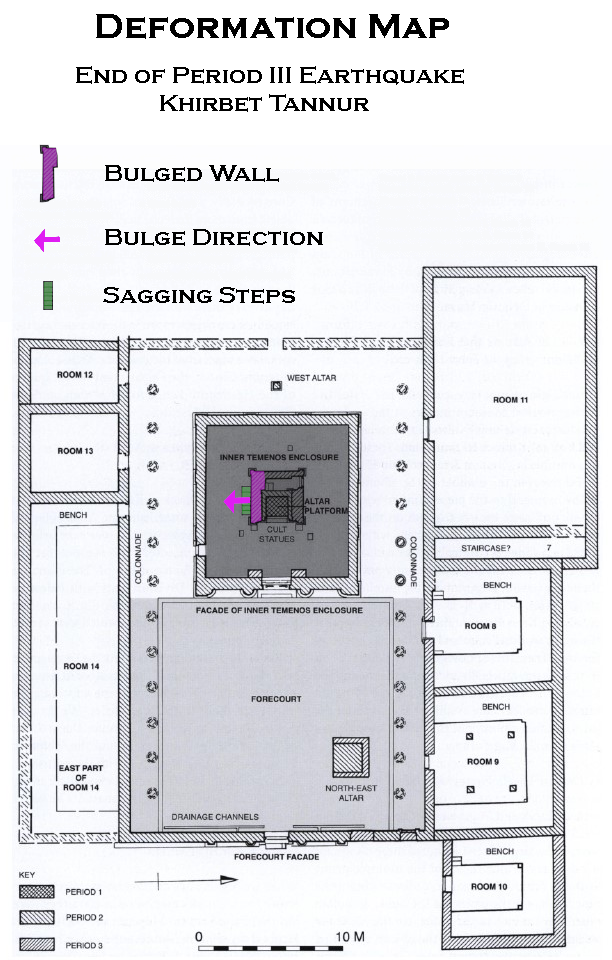

- Modified by JW from Fig. 6.4 of McKenzie et al (2013)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 6.4 of McKenzie et al (2013)

- Modified by JW from Fig. 6.4 of McKenzie et al (2013)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 6.4 of McKenzie et al (2013)

- Modified by JW from Fig. 6.4 of McKenzie et al (2013)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 6.4 of McKenzie et al (2013)

- Modified by JW from Fig. 6.4 of McKenzie et al (2013)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 6.4 of McKenzie et al (2013)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Period I Altar

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

Plate 112a

Plate 112aSub-II pavement laid against base of north side of Altar-Pedestal of Period I Glueck (1965) |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ornate pylon of the east facade of the raised inner temple enclosure

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

|

|

|

|

Period II altar near the northeast corner of the forecourt

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

|

|

aesthetically attractive but architecturally weaknoting shoddy internal construction particularly the bottom foundation stones (Glueck, 1965:107). Glueck (1965:106) was also unsure that an earthquake damaged Period II structures stating that

earthquake tremors or age or both may have brought about the collapseof the Period II Altar-Base. Considering this, the Intensity estimate is downgraded to VI-VII (6-7).

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

colonnades of the Court

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

various locations

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.4Khirbet et-Tannur, plan with the terms used here for the parts of the site, and their equivalents in Glueck's journal Mckenzie et al (2013)

Figure 1

Figure 1Khirbet et-Tannur, axonometric reconstruction (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016)

Figure 54

Figure 54Khirbet et-Tannur, reconstruction of Inner Temenos Enclosure and Altar Platform (Sheila Gibson) Whiting and Wellman (2016) |

|

|

Glueck, N. (1965). Deities and Dolphins. - open access at archive.org

McKenzie, J., et al. (2002). "Reconstruction of the Nabataean Temple Complex at Khirbet Et-tannur." Palestine exploration quarterly 134: 44-83.

McKenzie, J. S., Reyes, A. T., and Greene, J. A., “The Context of the Khirbet et-Tannur Zodiac, Jordan” ARAM 24 (2012 [2014]): 379–420.

McKenzie, J. S., et al. (2013)

The Nabataean Temple at Khirbet et-Tannur, Jordan, Volume 1

Architecture and Religion. Final Report on Nelson Glueck's 1937 Excavation. Annual of ASOR. 67

McKenzie, J. S., et al. (2013). The Nabataean Temple at Khirbet et-Tannur, Jordan, Volume 2 —

Cultic Offerungs, Vessels, and other Specialist Reports. Annual of ASOR. 68 - at JSTOR

Avi-Yonah, Michael. "Oriental Art in Roman Palestine." In Avi-Yonah's Art in Ancient Palestine: Selected Studies, pp. 119-211 , pis. 23 -

3 0 . Jerusalem, 1981 . Landmark study on Nabatean art, originally

published in 1961 , which develops die concept of "orientalizing" art

Glueck, Nelson. Deities and Dolphins: The Story of the Nabataeans. New

York, 1965 . Synthesis of Nabatean civilization focused on Khirbet

et-Tannur; replaces the final report, although the preliminary reports

provide useful additional information.

Glueck, Nelson. The Other Side of the Jordan. Rev. ed. Cambridge,

Mass., 1970 . General presentation of Glueck's survey in Transjordan, with a concise description of the temple of Khirbet et-Tannur.

McKenzie, Judith. "The Development of Nabataean Sculpture at Petra

and Khirbet Tannur." Palestine Exploration Quarterly 120 (1988) :

81-107 , Fig.s 1-15. Recent work on Nabatean sculpture critiquing

Glueck's three phases of the temple building; based on a detailed

stylistic analysis.

Starcky, Jean. "Le temple nabateen de Khirbet Tannur: A propos d'un

livre recent." Revue Biblique 7 5 (1968) : 206-235 , pis. 15-20 .

Penetrating critique of Glueck's Deities and Dolphins, challenging many

of his conclusions.

Zayadine, Fawzi. "Sculpture in Ancient Jordan," In The Art of Jordan:

Treasures from an Ancient Land, edited by Piotr Bienkowski, pp. 51 -

5 7 . Liverpool, 1991 . Includes a short classification of Khirbet etTannur's sculptural styles.

N. Glueck, AJA 41 (1937), 361-376; id., BASOR 65 (1937), 15-19; 67 (1937), 6-16; 69 (1938), 7-18; 85

(1942), 3-8; 126 (1952), 5-10; 141 (1956), 22-23; id., El7 (1964), 40*-43*; 8 (1967), 37*-41 *; id., Deities

andDolphins,NewYork 1965;id., Die Nabataar(ed. H. J. Kellner), Munich 1970, 31-34

R. Savignac, RB

46 (1937), 401-416; id. (and J. Starcky), ibid. 64(1957), 215-217

P. Thomsen, Archivfiir Orientforschung

12 (1937-1939), 93, 184-185

M. Avi-Yonah, QDAP 10 (1944), 114-118; id., Oriental Art in Roman

Palestine, Rome 1961, 49-50

J. Starcky, RB 75 (1968), 206-235

R. D. Barnett, NEAT, 327-330

A. Negev, PEQ 106 (1974), 77-78; American Archaeology in the Mideast, 98, 107

J. S. McKenzie, PEQ

120 (1988), 81-107.

M. -J. Roche, ACOR Newsletter 5/2 (1993), 10; id., ASOR Newsletter 45/2 (1995), 21–22; id., OEANE, 5,

New York 1997, 153–155; id., Transeuphratène 13 (1997), 187; 18 (1999), 59–69

A. Negev, Aram 6 (1994),

419–448; id., EI 25 (1996), 105*–106*

J. Dentzer-Feydy, SHAJ 5 (1995), 161–171

K. S. Freyberger,

Damaszener Mitteilungen 9 (1996), 143–161; id., Topoi. Orient-Occident 7 (1997), 851–871; id., Die Frühkaiserzeitlichen Heiligtümer der Karawanenstationen im hellenisierten Osten: Zeugniss eines kulturellen

Konflikts im Spannungsfeld zweier politscher Formationen (Damaszener Forschungen 6), Mainz am Rhein

1998

J. Patrich, Judaea and the Greco-Roman World in the Time of Herod in the Light of Archaeological

Evidence, Göttingen 1996, 197–218

L. Tholbecq, Topoi. Orient-Occident 7 (1997), 1069–1095

L. J. Ness,

Astrology and Judaism in Late Antiquity (Ph.D. diss., Miami 1990), Ann Arbor, MI 1998

J. S. McKenzie,

BASOR 324 (2001), 97–112; id. (et al.), ADAJ 46 (2002), 451–476; id., PEQ 134 (2002), 44–83; id., Petra

Rediscovered: Lost City of the Nabataeans (ed. G. Markoe), London 2003, 164–191

R. Rosenthal-Heginbottom, Measuring and Weighing in Ancient Times (Reuben & Edith Hecht Museum Catalogues 17), Haifa

2001, 51*–54*; id., ibid., new ed., Haifa 2005, 51*–54*

T. Weber, Gadara-Umm Qes I (Abhandlungen

des Deutschen-Palästina-Vereins 30), Wiesbaden 2002

E. Netzer, Nabatäische Architektur: Insbesondere

Gräber und Tempel (Sonderbände der Antiken Welt; Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie), Mainz am Rhein

2003, 89–91

F. Villeneuve & Z. al-Muheisen, Petra Rediscovered: Lost City of the Nabataeans (ed. G.

Markoe), London 2003, 83–100.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master kmz file | various |