Avdat/Oboda

Left

LeftOrthophoto of Avdat

Click on Image to open a high resolution magnifiable map in a new tab

www.govmap.gov.il.

Right

Oblique Aerial View of Avdat Acropolis

Click on Image to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Etan Tal (איתן טל) - German Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Avdat | Hebrew | עבדת |

| Abdah, Abde | Arabic | عبدة |

| Oboda | Ancient Greek | Ὀβόδα |

| Ovdat | ||

| Obodat |

Avdat started out in the 3rd or 4th century BCE as a Nabatean way station on the Incense Road (Avraham Negev in Stern et al, 1993). By the 1st century BCE, the town was named Oboba after Nabatean King Obodas I. It was occupied continuously until it was abandoned perhaps as late as the 9th or 10th centuries CE. Situated at the end of a ~4 km. long ridge, Avdat may have suffered from seismic amplification during past earthquakes as it may be subject to a topographic or ridge effect.

Oboda was named for a Nabatean king, whose name has been preserved in the Arabic 'Abdah. The Tabula Peutingeriana shows Oboda to have been situated on the main Aila (Elath)-Jerusalem road. It has been identified by all scholars with Eboda of Arabia Petraea mentioned by Ptolemy (V, 17, 4). However, according to this writer, Ptolemy's Eboda was a village east of the Arabah and thus, this identification is unacceptable. Oboda ('Οβοδα) is also mentioned by Uranius, quoted by Stephanus of Byzantium. It appears in a papyrus from Nessana (no. 39), tentatively dated to the sixth century CE. Its identification with 'Abdah is certain, in view of the similarity of the ancient and the Arabic names and the geographical locations. Furthermore, the name Oboda occurs in third-century CE Nabatean-Greek inscriptions found at Oboda. The site lies in the Negev desert on a spur of a mountain ridge running from southeast to northwest (map reference 1278.0228). At its highest point it is 655 m above sea level

Oboda was founded at the end of the fourth or the beginning of the third century BCE as a station on a junction on the caravan routes from Petra and Aila to Gaza. Temples were constructed there during the reigns ofObodas III (30-9 BCE) and Aretas IV (9 BCE-40 CE). During that period it became an important center for sheep, goat, and camel breeding and the manufacture of Nabatean pottery. The military camp for the camel corps guarding the caravan routes, which stood northeast of the town, may also date from that time. During the reign of Malichus II (40-70 CE), Oboda suffered destruction at the hands of pre-Islamic Arab tribes. Under Rabbel II (70-106 CE), agricultural projects were developed in the vicinity, as is evidenced by dedicatory inscriptions on libation altars found there.

Oboda was not adversely affected by the annexation of the Nabatean kingdom and the rest of the Negev into the Provincia Arabia in 106 CE. The second and third centuries were a period of great prosperity for the town, and in the third century CE a suburb was constructed on the southern spur of the city's ridge, in part on the ruins of Nabatean residences. An old Nabatean temple was dedicated to the local Zeus (Zeus Oboda) and a shrine to Aphrodite was built on the acropolis, apparently on the spot where a former Nabatean sanctuary had stood. A large catacomb (en-Nusrah) was dug into the southwestern slope. Construction in the Late Roman town went on as late as 296 CE.

In the time of Diocletian, the town was incorporated in the defense system of the eastern Roman Empire. Early in his reign, a fortress was built on the eastern half of the acropolis hill. Part of the local population was mobilized to serve as a militia against threatening Arab tribes. The payments from the imperial military treasury helped in the town's economy. With the advent of Christianity in the Negev, by the middle of the fourth century, two churches and a monastery replaced the pagan temples. Most of the remains of agricultural works in the town's vicinity belong to this period, when its economy rested, at least in part, on the cultivation of a fine variety of grapes and wine production. Oboda was abandoned after the Arab conquest in 636 CE

U. J. Seetzen was the first traveler to reach 'Abdah (l807). In 1838, E. Robinson located Oboda at 'Auja el-Hafir (later identified as Nessana). The town was surveyed by E. H. Palmer and T. Drake in 1870. In the summer of 1902, A. Musil conducted a more detailed survey, and in the winter of 1904 'Abdah was thoroughly explored by A. Jaussen, R. Savignac, and L. H. Vincent on behalf of the Ecole Biblique et Archeologique in Jerusalem. In 1912, the site was visited by a team headed by C. L. Woolley and T. E. Lawrence, on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. W. Bachmann, C. Watzinger, and T. Wiegand, serving as officers of the unit for the Preservation of Monuments attached to the German-Turkish army, came to the area in 1916 and drew precise sketches of the churches and some architectural details. In 1921, A. Alt published a corpus of the Oboda inscriptions known at that time.

The exploratory soundings made at 'Abdah by the Colt expedition brought to light the large Late Nabatean building at the southern end of the town and investigated the southwestern tower of the Late Roman-Byzantine fortress, which they identified as Hellenistic. Extensive excavations were undertaken from April 1958 until June 1961 by theN ational Parks Authority. The 1958 excavations were directed by M. Avi-Yonah and those of 1959-1961 by A. Negev. In 1975, 1976, and 1977, excavations at Oboda were conducted on behalf at the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums, directed by Negev and R. Cohen. In 1989, excavations were again conducted on behalf of the Hebrew University, directed by Negev.

In 1999–2000 an area located east of the Byzantine town wall and the north tower at Oboda was excavated on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The excavation was directed by T. Erickson-Gini. It revealed a residential quarter with a series of dwellings covering an area of approximately 0.25 a

- Annotated Satellite Image (google) of

Avdat from biblewalks.com

- Fig. 1 Aerial Overview of

Avdat from Zion et al (2022)

Figure 1

Avdat, looking east

- Army Camp from Roman Period

- Residential District

- Acropolis

- Cave City Avdat - W slope

- Cave City Avdat - E slope

- Orchards and Winepresses ?

- Orchards

- Orchards

- Orchards

- "Cave of the Saints"

(Photogrammetry: Yaakov Shmidov).

Zion et al (2022) - Avdat/Oboda in Google Earth

- Avdat/Oboda on govmap.gov.il

- Plan of Avdat from biblewalks.com

- Avdat Settlement Plan from

Zion et al (2022)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Avdat Settlement Plan

Zion et al (2022) - Avdat/Oboda General Plan

from Avraham Negev in Stern et al, 1993

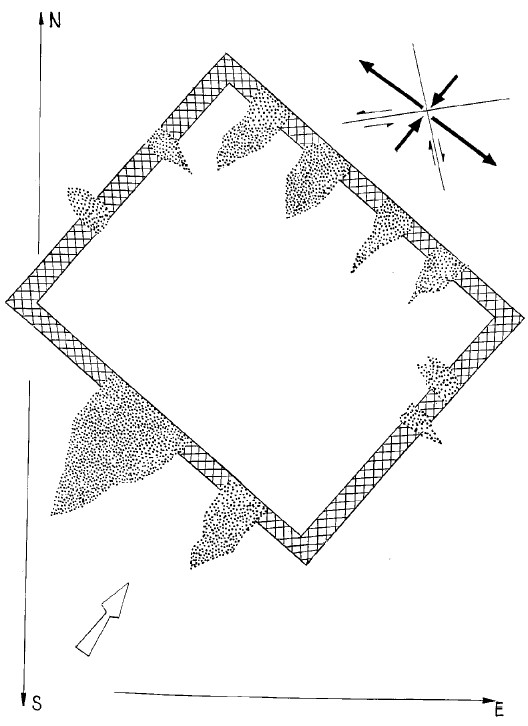

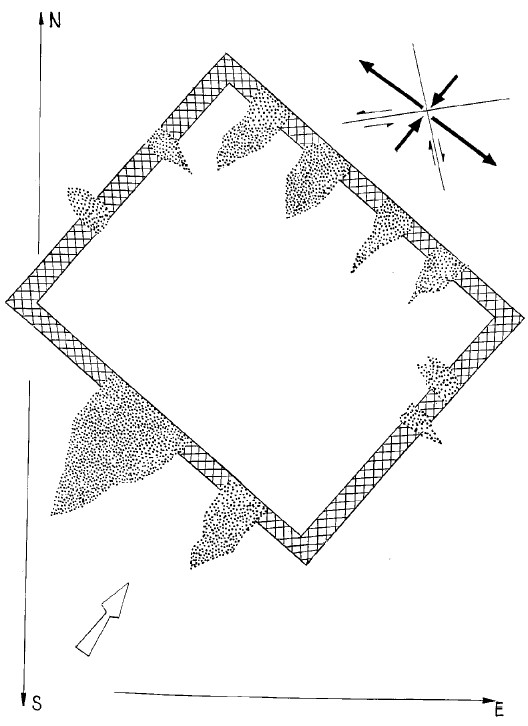

Oboda: general plan of the site and military camp.

Oboda: general plan of the site and military camp.

Stern et al (1993)

- Plan of Avdat from biblewalks.com

- Avdat Settlement Plan from

Zion et al (2022)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Avdat Settlement Plan

Zion et al (2022) - Avdat/Oboda General Plan

from Avraham Negev in Stern et al, 1993

Oboda: general plan of the site and military camp.

Oboda: general plan of the site and military camp.

Stern et al (1993)

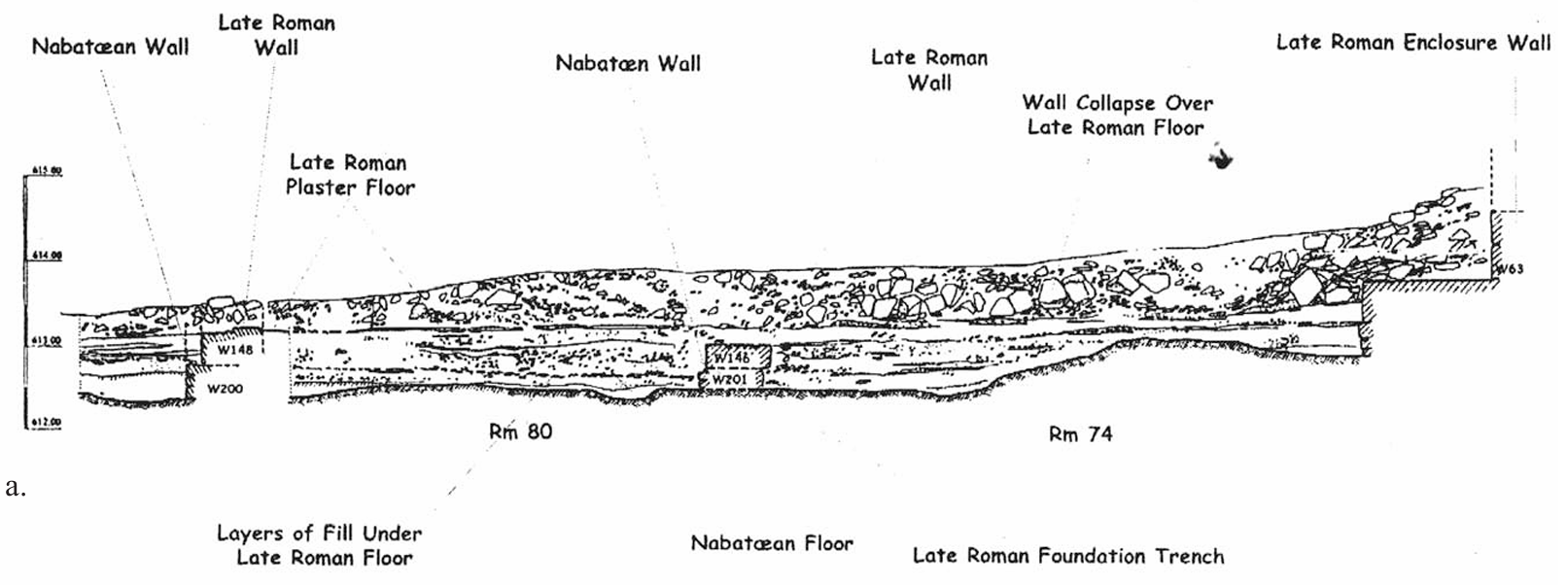

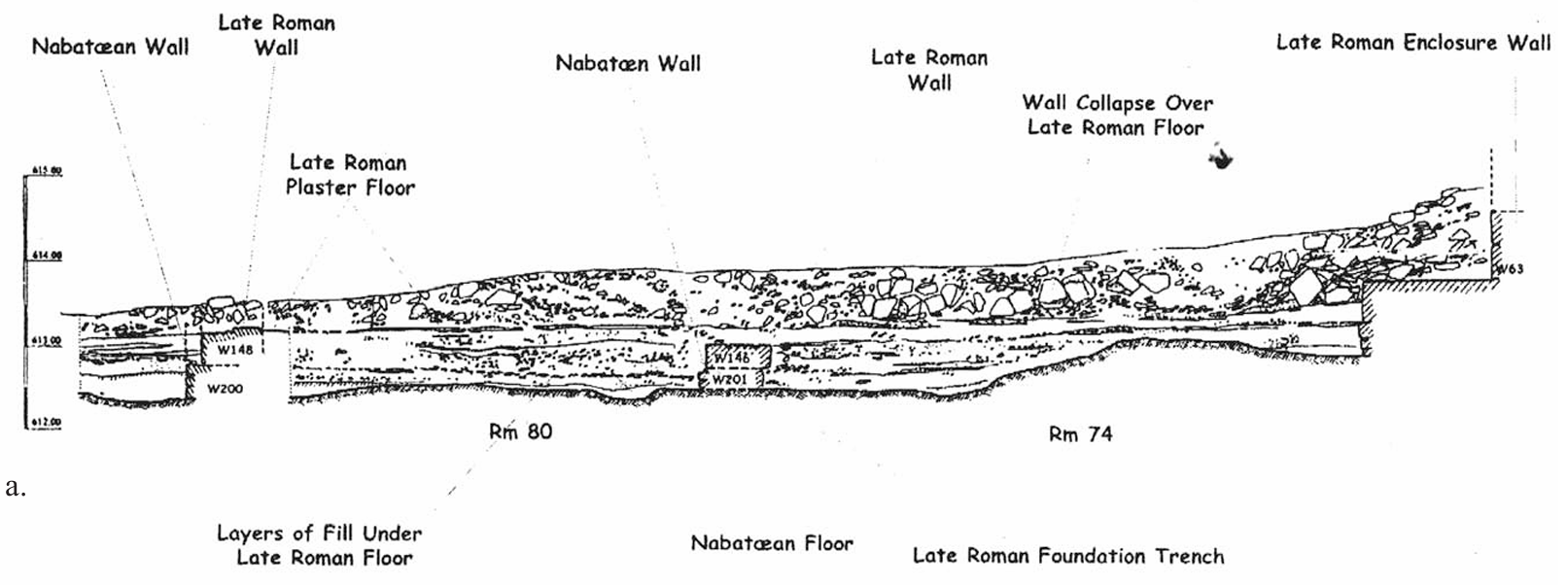

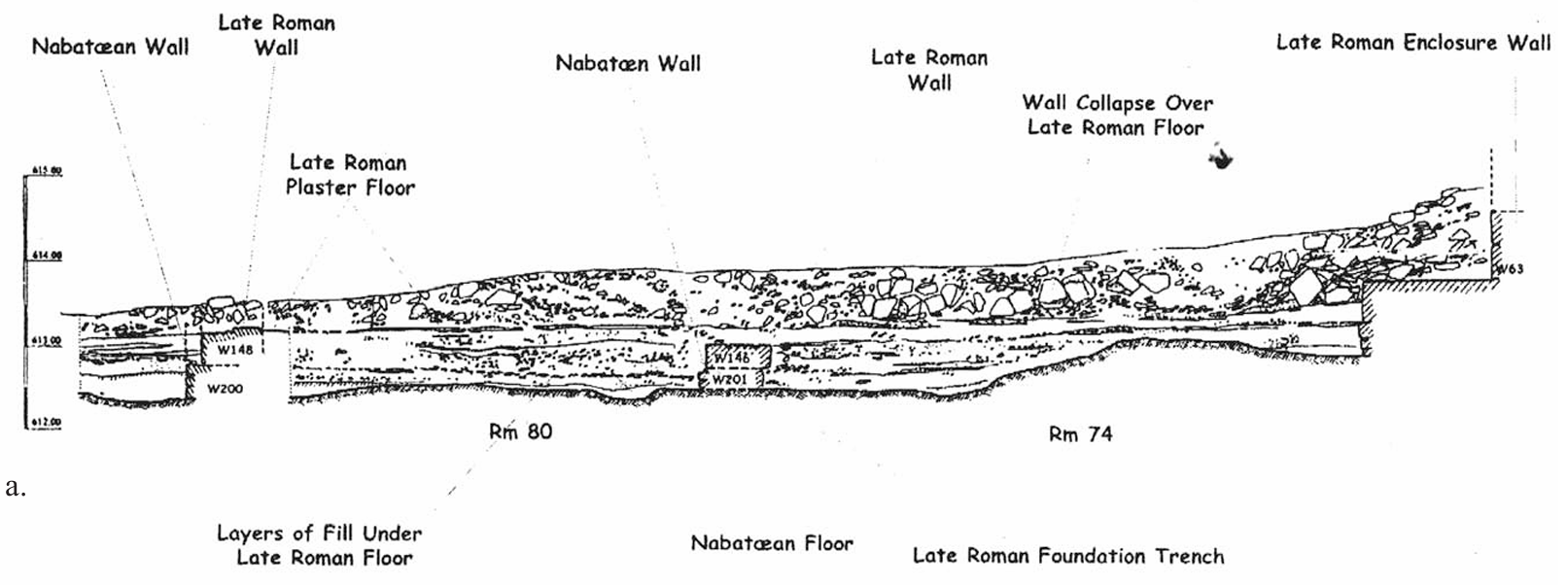

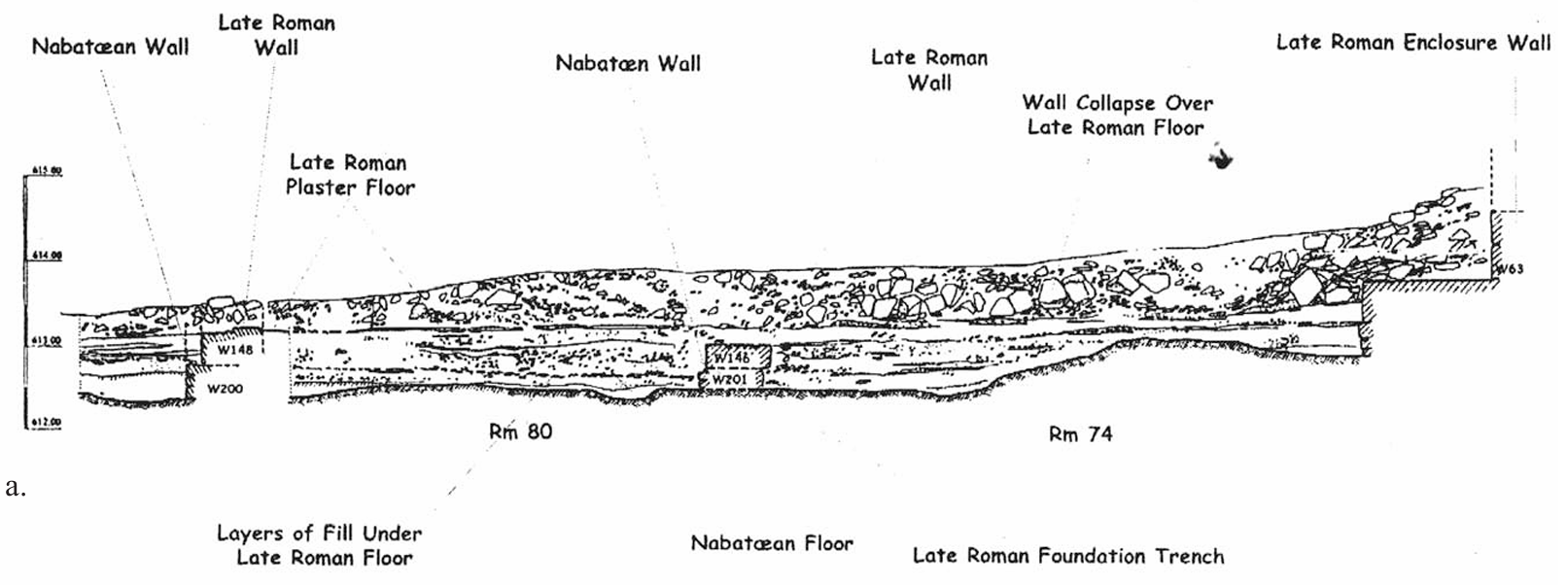

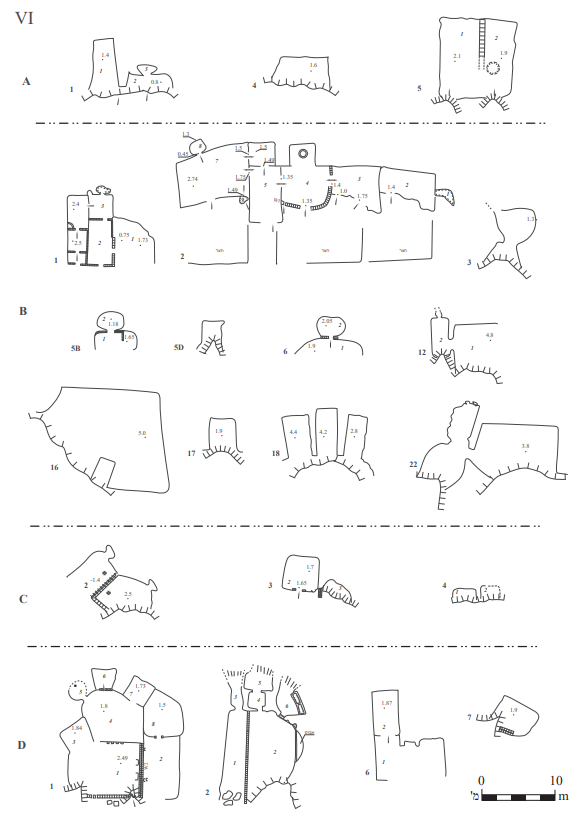

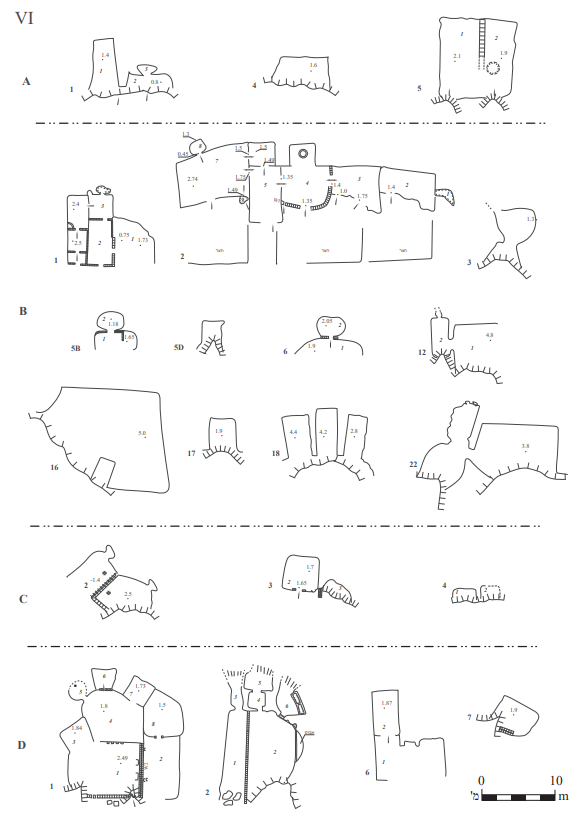

- Late Roman/early Byzantine

quarter occupational phases and room from Stern et al (2008)

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Stern et al (2008) - Fig. 1.72 Plan and Photo

of Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.72

Fig. 1.72

Oboda Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter, 1999-2000 excavations, plan and photo

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.73 Plan of

of Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter with Phases and Rooms from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.73

Fig. 1.73

Oboda Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter, occupational phases and rooms

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.77 Detailed Plan of

Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.77

Fig. 1.77

Oboda Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter, 1999-2000 excavations

Erickson-Gini (2010)

- Late Roman/early Byzantine

quarter occupational phases and room from Stern et al (2008)

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Stern et al (2008) - Fig. 1.72 Plan and Photo

of Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.72

Fig. 1.72

Oboda Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter, 1999-2000 excavations, plan and photo

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.73 Plan of

of Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter with Phases and Rooms from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.73

Fig. 1.73

Oboda Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter, occupational phases and rooms

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.77 Detailed Plan of

Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.77

Fig. 1.77

Oboda Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter, 1999-2000 excavations

Erickson-Gini (2010)

- Fig. 1 Excavation Areas A, B,

and D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The excavation areas

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 1 Area A from

Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 1

Plan 1

Area A

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 2 Area B, plan

and sections from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 2

Plan 2

Area B, plan and sections

Erickson-Gini (2022)

- Fig. 1 Excavation Areas A, B,

and D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The excavation areas

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 1 Area A from

Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 1

Plan 1

Area A

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 2 Area B, plan

and sections from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 2

Plan 2

Area B, plan and sections

Erickson-Gini (2022)

- Fig. 1 Excavation Areas A, B,

and D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The excavation areas

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 3 plan of dipinti

Cave in Area D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 3

Plan 3

Area D, plan of the Dipinti Cave.

Erickson-Gini (2022)

- Fig. 1 Excavation Areas A, B,

and D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The excavation areas

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 3 plan of dipinti

Cave in Area D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 3

Plan 3

Area D, plan of the Dipinti Cave.

Erickson-Gini (2022)

- Fig. 1.70 Army Camp from

Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.70

Fig. 1.70

The 1999 excavation of the army camp at Oboda

Erickson-Gini (2010)

- Fig. 1.70 Army Camp from

Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.70

Fig. 1.70

The 1999 excavation of the army camp at Oboda

Erickson-Gini (2010)

- Fig. 1.71a Cross section of

the principia in the army camp from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.71a

Fig. 1.71a

Cross section of the principia in the army camp at Oboda

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.79 Photo and section of

Room 23 in Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.79

Fig. 1.79

Room 23 in situ plaster on wall 55, and b. section drawing of the room

Erickson-Gini (2010)

- Fig. 1.71a Cross section of

the principia in the army camp from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.71a

Fig. 1.71a

Cross section of the principia in the army camp at Oboda

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.79 Photo and section of

Room 23 in Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.79

Fig. 1.79

Room 23 in situ plaster on wall 55, and b. section drawing of the room

Erickson-Gini (2010)

- Fig. 2 Warped external wall

in Area A from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Area A, the warped external western wall (W1), looking southeast.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 3 arch springer along

the northern interior of Wall W1 in Area A from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Area A, the arch springer along the northern interior of W1, looking northwest

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 4 remains of earlier

wall over which Wall W1 was constructed in Area A from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Area A, remains of earlier wall over which W1 was constructed and the line of stones (W5), looking west

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 5 southern wall (W3)

and the foundation of original western Wall W1 on the right in Area A from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Area A, the southern wall (W3) and the foundation of original western W1 on the right, looking south

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 6 repairs in the

northern wall (W2) in Area A from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Area A, repairs in the northern wall (W2), looking north.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 8 Collapsed arches

and ceiling slabs in Room 1 of Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Area B, collapsed arches and ceiling slabs in Room 1, looking west.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 9 Rotated Blocks in

Room 1 of Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Area B, signs of rotation in the arch springer along W1 in Room 1.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 10 Arch Stone from

Room 1 in Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Area B, arch stone with incised, red-painted frame from the collapse in Room 1.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 11 Arch Stone from

Room 1 in Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Area B, arch stone with incised, red-painted lines and frame from the collapse in Room 1.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 15 Remains of pantry

in L2/01 of Room 2 in Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

Area B, remains of pantry in L2/01, looking southeast.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 16 Collapsed bedrock

shelf fronting cave above Dipinti Cave from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

Area D, collapsed bedrock shelf fronting the cave above the Dipinti Cave, looking north.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 18 probe in front of

Dipinti Wall in Area D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Area D, eastern extension of probe in front of Dipinti Wall, looking east toward W2.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 19 blocked entrance of

Dipinti Cave in Area D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

Area D, blocked entrance of Dipinti Cave, looking north

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 1.78a Fallen arch

attributed to 363 CE earthquake in Room 4 Phase 3 of Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.78a

Fig. 1.78a

Fallen arch under the floor of Room 4, Phase 3, sublevel, 363 CE

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.78b Crushed Pottery

attributed to 5th c. CE earthquake in Room 7 Phase 3 of Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.78b

Fig. 1.78b

Vessels crushed under the collapse of Room 7, phase 3, early fifth c. CE

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.80a Fallen lintel on

the floor of Room 22 of Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.80a

Fig. 1.80a

Fallen lintel on the floor of Room 22

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Fig. 1.80b In situ brazier

made from a “Gaza” wine jar on the floor of Room 22 of Late Roman/Early Byzantine Quarter from Erickson-Gini (2010)

Fig. 1.80b

Fig. 1.80b

In situ brazier made from a “Gaza” wine jar on same floor [Room 22]

Erickson-Gini (2010) - Photo 6 So-called Potter's

Workshop and Khan from Negev (1997:5)

Photo 6

Photo 6

The khan, potter's workshop

Negev (1997:5) - Photo of so-called Potter's

Workshop (?) by Jefferson Williams

So-called Potter's workshop at Avdat/Oboda

So-called Potter's workshop at Avdat/Oboda

(JW: or so I thought at the time - I could be wrong)

Photo by Jefferson Williams

Archeological excavations have uncovered several earthquakes which struck Avdat/Oboda. Erickson-Gini, T. (2014) noted approximate dates and Intensities:

Substantial destruction in the early 2nd century CE

Some damage due to an earthquake in 363 CE.

A massive earthquake in the early 5th century CE

A massive earthquake in the early 7th century CE

[JW: recent work (2022) may suggest this should revised to the 7th century rather than the early 7th century]

Erickson-Gini, T. (2014) described the early 2nd century earthquake as follows:

There is indirect evidence of a more substantial destruction in the early 2nd century CE in which residential structures from the earliest phase of the Nabataean settlement east of the late Roman residential quarter were demolished and used as a source of building stone for later structures. Destruction from this earthquake is well attested particularly nearby at Horvat Hazaza, and along the Petra to Gaza road at Mezad Mahmal, Sha'ar Ramon, Mezad Neqarot and Moyat `Awad, and at `En Rahel in the Arava as well as at Mampsis (Korjenkov and Erickson-Gini 2003).Erickson-Gini and Israel (2013) added

Evidence of an early second-century CE earthquake is found at other sites along the Incense Road at Nahal Neqarot, Sha'ar Ramon, and particularly at the head of the Mahmal Pass where an Early Roman Nabataean structure collapsed (Korjenkov and Erickson-Gini 2003; Erickson-Gini 2011). There is ample evidence of the immediate reconstruction of buildings at Moyat ‘Awad, Sha'ar Ramon, and Horvat Dafit. However, this does not seem to be the case with the Mahmal and Neqarot sites.Erickson-Gini and Israel (2013) discussed seismic damage at Moyat ‘Awad due to this earthquake

The Early Roman phase of occupation in the site ended with extensive damage caused by an earthquake that took place shortly before the Roman annexation of the region in 106 CE (Korjenkov and Erickson-Gini 2003). The building in Area C and the kiln works were destroyed, and the cave dwellings were apparently abandoned as well. Reconstruction was required in parts of the fort. At this time, deposition from its floors was removed and thrown outside of the fort and a new bath as well as heating were constructed in its interior. Along its eastern exterior and lower slope, rooms were added. Thus, the great majority of the finds from inside the fort and its ancillary rooms date to the latest phase of its occupation in the Late Roman, post-annexation phase, the latest coins of which date to the reign of Elagabalus (219–222 CE).

- Fig. 1 Aerial Overview of

Avdat from Zion et al (2022)

Figure 1

Avdat, looking east

- Army Camp from Roman Period

- Residential District

- Acropolis

- Cave City Avdat - W slope

- Cave City Avdat - E slope

- Orchards and Winepresses ?

- Orchards

- Orchards

- Orchards

- "Cave of the Saints"

(Photogrammetry: Yaakov Shmidov).

Zion et al (2022) - Late Roman/early Byzantine

quarter occupational phases and room from Stern et al (2008)

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Stern et al (2008)

- Fig. 1 Aerial Overview of

Avdat from Zion et al (2022)

Figure 1

Avdat, looking east

- Army Camp from Roman Period

- Residential District

- Acropolis

- Cave City Avdat - W slope

- Cave City Avdat - E slope

- Orchards and Winepresses ?

- Orchards

- Orchards

- Orchards

- "Cave of the Saints"

(Photogrammetry: Yaakov Shmidov).

Zion et al (2022) - Late Roman/early Byzantine

quarter occupational phases and room from Stern et al (2008)

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Stern et al (2008)

At Oboda (Eboda/Abde/Avdat) the Colt Expedition excavated an isolated ‘villa’ located south of the town, but they never published their results. The plans and a description of this structure were later published by Negev, who dated it (on the basis of architectural features) to the second and third centuries CE (Negev 1997: 73-79). The Colt Expedition also excavated and published a structure located between the South Church and the Byzantine Citadel, described as a “Hellenistic building” (Colt 1962: 45-47, Pl.LXVIII, Negev 1997: 24-25). P.L.O. Guy reported that the expedition carried out some preliminary work on the bathhouse that was left unfinished (Guy 1938: 13).

Between the years 1958 and 1961, Avi-Yonah and Negev, sponsored by the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, directed excavations at Oboda in conjunction with the restoration project instigated by the National Parks Authority. This work produced a large quantity of important Nabataean, Aramaic, Nabataean Greek and Byzantine Greek inscriptions, many of which were translated and published by Negev (Negev 1961: 127-138,1963a: 113-124).

Negev was appointed to supervise on site work under Avi Yonah’s supervision in 1958, and in 1959 he took over the project (Negev 1997: X). Negev carried out excavations throughout the site between 1958-1961 and in 1989. The results of these excavations were published in many small articles and in two books: The Late Hellenistic and Early Roman Pottery of Nabatean Oboda (Negev 1986) and The Architecture of Oboda (Negev 1997), (Fig. 1.17). Negev’s work at the site concentrated on areas of the acropolis such as the two Byzantine churches, the Byzantine Citadel and a structure inside the temenos area that he identified as a temple. This last structure was the same “Hellenistic Building” studied by the Colt Expedition (Negev 1997: 24-38). Negev also studied the western side of the temple platform and adjoining structures (Negev 1997: 38-61). During the course of these excavations several important Nabataean and Greek inscriptions were discovered. These inscriptions date to two primary periods: the late first century BCE and the second half of the third century CE. The earliest inscription dates to the second regnal year of Aretas IV, 8/7 BCE (Negev 1997: 3). Eight Greek inscriptions that appear to have been engraved on the lintel over the main entrance to the platform portico date to the later phase of the temple in the third century. These include a dedicatory inscription dating to 267/8 CE. Although the inscriptions are written in the Greek language, the names of the worshippers appear to be Nabataean (Negev 1997: 53). Near the southeastern corner of the portico a small space was discovered, which appears to have served as the temple treasury. An inscription, engraved on a marble plaque found in the southwestern staircase tower, records the names of three of Aretas’ IV children (Negev 1961: 127 128, 1997: 51). In addition, a hoard of bronze figurines and other objects were also found in this area (Negev 1997: 51, Rosenthal-Heginbottom 1997: 192-202).

Negev also excavated buildings that he described as the ‘Roman Quarter’ located south of the acropolis, including the Roman tower first discovered by Musil in 1902, the en Nusra burial cave, the Byzantine bathhouse, a Byzantine dwelling and the Saints’ Cave located below the acropolis. Inscriptions from the Roman tower and the en-Nusra burial cave were of particular importance in reconstructing the history of the site. This inscription, engraved on the lintel of the entrance into the tower, dates to 293/4 CE and describes the builder as a Nabataean mason named Wa’il from Petra (Negev 1981a: 26-27, no. 13). Inscriptions found in the en-Nusra burial cave date to the mid third century and according to Negev they appear to relate exclusively to women buried there. The earliest inscription dates to July 23, 241 CE (Negev 1981a: 24-25, no.10). On the eastern edge of the site, Negev excavated a pottery workshop that he believed to have functioned between 25 BCE to around 50 CE (Negev 1974, 1986: XVII). He reported that only two coins were found in the structure. The first dates to the reign of Trajan and the second I dated generally to the third or fourth centuries CE (Negev 1986: XVIII). Contrary to Negev's initial belief that Nabataean fine painted wares were produced in this workshop, subsequent neutron activation analysis of the posttery has indicated that it was produced in or near the area of Petra (Gunneweg et al 1988: 342). Likewise, Negev's designation of another example of early fine ware discovered in the structure and elsewhere at Oboda, as "Nabataean Sigillata," proved to be a form of Eastern terra sigillata, called ETS II by Gunneweg and Cypriote Sigillata by Hayes (Gunneweg et al 1988, Hayes 1977). The fact that the pottery workshop abuts a second to third century CE caravanserai (see below) on the north and a heavy midden on the south cast serious doubts about the dating of the structure to the early first century CE. A recent study by Fabian and Goren (2008) refutes Negev's identification of the structure as pottery workshop.

Between 1975-1977, Negev, sponsored by the Hebrew University at Jerusalem, carried out joint excavations with R. Cohen from the Israel Department of Antiquities. They carried out trial excavations in the large military camp located northeast of the acropolis, a structure identified as a caravanserai south of the military camp, and a fourth century CE farmhouse complex east of the town (Cohen and Negev 1976: 55-57; Negev 1977a: 27-29; 1997: 7). The final report of the excavations has not yet been published (Negev 1997: XI). However, some preliminary findings were published by Cohen (Cohen 1980a: 44-46). Negev subsequently claimed that the military camp was constructed by the Nabataeans and functioned in the first century CE, a conclusion not shared by Cohen (Cohen 1982a: 45).

According to Cohen, the caravanserai found abutting the pottery workshop on the eastern side of the site dates to the second and third century CE. This structure measures 22.5 by 31 m. and is made up of a series of rooms located around a central courtyard. This structure was rich in ceramic finds and particularly Nabataean painted ware bowls and other vessels dated to the early third century. Cohen pointed out that these bowls, which appear to be a debased version of the Nabataean fine ware tradition in decoration, form and texture, are identical to a bowl found next door in the pottery workshop, dated by Negev to the early first century CE, and in the Nabataean necropolis at Mampsis. Coins found on the floors of the structure included several dated to the late second through the third quarter of the third century CE. Above the collapse layer of the caravanserai at least 80 coins dated to the second half of the fourth c. CE were found (Cohen 1982a: 45 46), (Fig. 1.18). During the 1975 excavations, Negev discovered a large house dated to the first century CE less than 100 meters from the military camp. Sixteen rooms of this structure were cleared. At least one room served as a kitchen with large ovens. Negev, impressed with the fact that several small cubicles were found throughout the structure and the poor quality of the architecture, claimed that the structure was probably a tavern or hostel (Negev 1996: 83-84). Elsewhere at the site, a pouch with coins and semi-precious stones from the region of the Indian Ocean were found in graves dated to the early first centuries of the first millennium CE (Negev 1977a: 29).

In the same excavation season, a large structure located east of the “Roman Quarter” (the Byzantine town) was also investigated. This structure proved to be a farmhouse complete with a finely constructed wine press and cooking facilities dated to the fourth and fifth centuries CE. Negev reports that the building appears to have been built over an earlier Nabataean structure. Pieces of a large stone libation altar bearing a Nabataean inscription were found in the courtyard of the building. In a room next to the winepress two large jars were found sunk into the floor, which Negev believed to have been used to store wine that may have been tasted before its purchase by buyers. Elsewhere in the building plaques made from camel bones were found bearing lines of Greek script written in ink. One inscription apparently contains receipts concerning the hiring of camels and donkeys for transporting grapes from nearby vineyards (Negev 1977a: 28).

Further excavations were carried out at Oboda in the 1990s by archaeologists of the Israel Antiquities Authority. These include excavations by Katz and Tahal in structures in the ‘Roman Quarter” and the excavation by Tahal of the large Byzantine period winepress located next to the southern side of the acropolis and Saints’ Cave (Tahal 1994: 112 114). The exterior of the bathhouse and the pools next to the bathhouse well were excavated by Tahal in 1992 (Tahal 1994: 114-115). The excavation of the well area was resumed by Erickson-Gini in 1993. The area around the pool produced evidence that the bathhouse and the well were constructed in the fourth century CE and continued in use, after substantial renovations due to earthquake damage, in the Byzantine period. The earthquake probably occurred in the early fifth century CE, and damage related to it was detected elsewhere in the site.

In 1993-1994, P. Fabian, of the Israel Antiquities Authority, excavated a domestic dwelling in the ‘Roman Quarter,’ Building “T,” and he conducted several trial excavations along the town wall east of the acropolis. Fabian’s work demonstrated that the structures in the area described by Negev as the “Roman Quarter” dated to the Byzantine period. He also discovered that Building “T” was destroyed by a devastating earthquake in the early seventh century that demolished the entire site of Oboda (Fabian 1996).

In 1999, the military camp east of the town, previously excavated by Negev and Cohen, was excavated extensively by Fabian and Erickson–Gini, revealing over fifty percent of the total area of the camp (Fig.1.19). Results of the excavation indicate that the camp was a Roman military camp and not Nabataean as proposed by Negev (Erickson Gini 2002), (Fabian 2001: 18; 2005). Further excavations were carried out by the author in a domestic quarter in Oboda dating to the fourth century CE that was destroyed in an earthquake sometime in the early fifth century CE (Fig. 1.20). In addition, remains of two earlier structures were found on the eastern side of the quarter. One structure dates to the second and early third centuries CE and it appears to have been abandoned abruptly with the contents of the household left intact, possibly as the result of an epidemic that struck the town in the first half of the third century CE. Three rooms of a second structure appear to belong to a large villa dating to the first century CE located on the eastern edge of the excavation area (Erickson-Gini 2001a: 6; 2001b: 374-375).

The Nabataean fort, Mezad Nahal Avdat, (12280/1810), measuring 17.5×17.5 m., was excavated in 1986 by Y. Lender (Lender 1988: 66-67), (Fig. 1.21). Nabataean pottery dated to the first and second centuries CE. An ostrakon in Nabataean script and a coin of Trajan were found in the fort. Near the fort a second building measuring 10×13.5 was excavated, producing pottery dated to the first century CE. ...

The site of Oboda is situated on a plateau overlooking Nahal Zin a few kilometers south of the springs of ‘En Avdat and ‘En Aqev. It is located several kilometers south of the communities of Kibbutz Sede Boqer and Midreshet Ben Gurion on the modern Mizpe Ramon highway leading to Eilat.

It appears that Oboda was first occupied by the Nabataeans in the Hellenistic period until around 100 BCE. No structural remains have been found at the site dating to this period. However, pottery and coins dating to the late Hellenistic period have been found in most areas of the plateau. In this early period the site appears to have been primarily used for seasonal occupation as a camping ground in conjunction with the transport and trade of incense resins between Petra and Gaza. In the Hellenistic period the main road linking Oboda with the central Arava valley and Petra was the Darb es-Sultan, the “Way of the King” by way of Moa, Mezad ‘En Rahel, ‘En Orahot and Mezad ‘En Ziq. Along with other early Nabataean sites dating to this period, Oboda appears to have been abandoned for several decades in the first century BCE in wake of the Hasmonaean conquest of Gaza by Alexander Jannaeus at the beginning of that century. Oboda was reoccupied in the last decades of the first century BCE, possibly during the reign of Obodas III or Malichus I (Negev 1997:3). At that time a temple platform and temples were constructed at the site and the town was named after the deified Nabataean king Obodas II. In the late first century BCE a new road with caravansaries, forts and cisterns was constructed between Moyat 'Awad and Oboda by way of the Ramon Crater.

The site was occupied continuously from that period until the early seventh century CE. Seismological studies carried out at the site indicate that the final destruction there was caused by a compressional seismic wave originating only 15 km. south, south-west of Oboda, probably in the area of the Nafha Fault zone (Korjenkov and Mazor 1999a: 27-28).

In the intermediate period, Oboda appears to have been an important caravan station on the Petra – Gaza road until a decline in international trade occurred throughout this area in the early third century CE. The town appears to have been revitalized at the end of the third century CE during the Diocletianic military build-up in the region. In 293/4 CE, a watch tower was constructed at the south end of the town. Further north a second tower, located near the acropolis, (as yet unexcavated) was probably constructed in the same period. In this period a large army camp measuring 100 x 100 m. was constructed northeast of the acropolis on the plateau (Erickson-Gini 2002). The size and nature of this installation indicates that it may have been occupied by a Roman cavalry force the size of a cohort. The camp was abandoned in an orderly fashion after a short period of occupation, possibly as the result of military arrangements under Constantine I. The results of recent excavations indicate that the site sustained some damage in the 363 earthquake and more devastating damage in an earthquake sometime around the beginning of the early fifth century as discuss here above.

The Byzantine town was constructed over the remains of the former settlement south of the acropolis and a town wall was constructed around the Byzantine period town, including the large complex of caves that were utilized as dwellings. Two churches were built inside the temenos area constructed from stones of the destroyed temples that formerly stood there. In the fifth century a citadel, quite similar to that constructed in the same period at Nessana, was constructed next to the temenos. From the fourth through the sixth century the primary occupation of the town’s inhabitants appears to have been agriculture and particularly the manufacture of wine. Five wine presses have been found in and around the site dating to this period (Negev 1997:7). It also appears that some of the caves and particularly one designated the “Saints Cave,” were used to store and ferment wine (Negev 1997:165-167).

Regarding the abandonment of the town, A. Negev points out that the churches were both destroyed by fire, sometime after 617 CE, the latest burial found in the South Church (Negev 1997: 9). More recent investigations have revealed that the town was destroyed by a severe local earthquake in the early seventh century, around 630 CE, and subsequently abandoned (Fabian 1996; Korjenkov and Mazor 1999a).

Between March and December 1999, the army camp situated north-east of the acropolis was excavated by P. Fabian and the writer on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority as part of a project initiated by the Ministry of Labor and Welfare and in order to facilitate further development of the site for tourism (Fig.1.70).1

The ceramic material and small finds found in the excavation of the camp was sorted and registered by the writer and a final report of the excavation will be produced by Fabian.2 A preliminary publication of the excavation of the camp, including the stratigraphy, was prepared by the author entitled: ‘Nabataean or Roman? Reconsidering the Date of the Camp at Avdat in Light of Recent Excavations’, (Erickson-Gini 2002).

A few rooms in the camp had been previously excavated by Negev and Cohen between 1975 and 1977. Negev proposed that the camp was constructed by the Nabataeans in the mid-first century CE (Negev 1977:622-624). His co-excavator, Cohen deemed the scope of the excavation insufficient in determining whether the camp was occupied only in the first century or after the Roman annexation in 106 CE (Cohen 1980:44, 1982a:245). The new excavations uncovered over fifty percent of the total area of the camp, including the main gate located on the east side of the camp, four blocks of barrack rooms, two rows of casemate rooms along the interiors of the eastern and southern walls, and what appears to have been the principia, or camp headquarters, along the interior western wall of the camp.

The camp measures approximately 100 x 100 meters with corner towers and interval towers as well as towers guarding the main access to the camp on the east and south sides. In the recent excavations the remains of stairs were found leading up to the southeast and southwest towers. It is assumed that the interval and guard towers were accessed by means of wooden stairs or ropes that are no longer extant. The casemate rooms along the southern and eastern walls of the camp do not appear to have been roofed over and these rooms may have been used as stables and storerooms. A single pilaster was found along the center of the back wall in each casemate room, presumably used as a base for a wooden pillar holding up a wooden rampart or parapet along the walls. Evidence for this type of construction was found in casemate rooms along the southeast part of camp. Walls that survived to their full height in this section were offset along the upper row of stones, providing support for a wooden construction such as a rampart. The upper half of a Gaza wine jar, dated to the fourth century CE, was found embedded in the floor of Room 66, a casemate room near the southwest corner of the camp.

The rooms in the barracks measured approximately 20 square meters of floor space. It is estimated that the room could have accomadated between 4 and 8 men per room depending on the type of sleeping arrangements. The rooms do not appear to have been roofed with stone slabs as is commonly found in most buildings from this period in the region. No arch springers were found in any of the rooms and it is assumed that the roofing was made of wooden beams covered with organic material and mud plaster. The spaces between the stones on the exterior walls were covered with a hard hydraulic plaster to prevent seepage during rain. The same type of construction was found in the sixth century CE fort of Mezad Ma’ale Zin excavated by the writer in 1999 (Israel and Erickson-Gini 1999). No specific activities were found in the barrack rooms other than evidence in one room of lead fragments probably used to repair tools or weapons.

A series of rooms along the western side of the camp appear to have served as the principia or headquarters (Fig.1.71). While some rooms, constructed out of regular large building stones, survived in the southern side of this section, the rooms further north appear to have been constructed from fine ashlar blocks, presumably stones in secondary use collected from earlier buildings at the site.

Many of these stones were stripped out to the foundation. One block, in secondary use, was found among the stones of a collapsed wall and it bears part of a Nabataean inscription with the name Rabbel, presumably that of Rabbel II, the last Nabataean king (70-106 CE). The rest of the inscription awaits translation.

The principia contained a long room (Room 80) facing the eastern gate, the main gate of the camp, this being the only room in the camp with a plaster floor. Pottery found over this floor included a Late Roman cooking pot, one of the few restorable vessels found in the camp, as well as fragments of Beit Natif lamps dated to the third and fourth century and rims of Gaza Wine jars dated to the fourth century Excavation in this room provided clear evidence that some of the walls were constructed over and offset to earlier walls of a Nabataean building dated by coins and pottery to the last quarter of the first century CE. Coins of the Jewish Revolt from 68 CE were found over the floor surface of this early structure in Room 74 by the author.

The camp appears to have been used for a short amount of time and it was abandoned in an orderly fashion. During its occupation it was well maintained with a minimum amount of buildup of debris throughout the camp. The confusion concerning the date of its construction appears to be the result of copious amounts of Nabataean pottery sherds and coins, dating to both the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods, found throughout the camp. This material was discovered from the surface down to deposits of collapsed stones over the floors, as well as under the dirt floor surfaces. In some cases foundation trenches of the walls were cut directly into Hellenistic and Early Roman middens, particularly in the southeast side of the camp. At least one Hellenistic lamp was found in a layer of ash in one of the barrack rooms on the east side of the camp, only a few centimeters below the floor surface of the room. In the eastern side of the street, oriented east to west along the southern side of the camp, a heavy layer of crushed limestone was used to seal heavy deposits of ash from middens dating to the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods.

Two hundred and seventy coins were found in the camp, one hundred and forty-three of which were identified after cleaning. The overwhelming amount of coins and pottery found in the camp date to the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods. However, coins dated to the late third and early fourth century CE were found in key locations over floor surfaces and streets and also below the floor surface of one of the interval towers. The coins from this period made up the second largest group of coins found in the camp. Only a small amount of pottery from that period was found in the camp, as described here above.

The co-excavator of the site, P. Fabian has proposed that the camp was constructed by the Roman army in wake of the Roman annexation of Nabataea in 106 CE. He proposes that the camp was occupied until the Bar Kochba Revolt (132-135 CE) and evacuated when Roman forces were deployed in Judaea (Fabian 2001; 2005). However, only one Roman coin from the early second century was found in the camp.

Due to the fact that only one occupational phase was indicated by the architecture of the camp, I propose that the camp was constructed in the late third or early fourth century and abandoned sometime in the first half of the fourth century CE. In my opinion, the Hellenistic and Early Roman Nabataean pottery and coins found in the camp are derived, from soil used in the construction of the camp, the source of which may be found in the middens covering the area around and under the camp itself. In order to prove this hypothesis, micromorphological analysis of soil obtained in sections in the barrack rooms and inside of unexcavated walls, as well as in the middens outside the camp, were examined in the laboratories of Cambridge University, UK. These samples, which have not yet been officially published, have revealed traces of microscopic pieces of ceramics, ash, charcoal, bones and other organic matter found in middens (B. Pittman, pers. comm.).

1 The numismatic finds were examined by H. Sokolov of the IAA. These

and other finds were cleaned by the laboratories of the IAA under the

direction of E. Altmark. The ceramic and small finds were drawn by A.

Dudin and plans and sections of the excavation were drawn by V. Essman

and S. Persky. C. Amit and T. Segiv photographed the excavation and the

finds. The ceramic finds were sorted by the writer.

2 An alternative interpretation of the excavation and the date of the

construction and occupation of the camp may be found in Fabian's

unpublished doctoral dissertation (2005)

In addition to the army camp, an area near the north tower situated east of the acropolis and the town wall was excavated by the writer on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority as a continuation of the work project sponsored by the Ministry of Labor and Welfare. A few years earlier, in 1994, a series of probes were carried out along the town wall north of the tower by P. Fabian on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, the results of which are Figure 1.76a. Oboda Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter, Phase 2 building facing West, early third c. CE Figure 1.76c. Oboda Late Roman / Early Byzantine Quarter, Room 6, Pantry with in situ pottery as yet unpublished. My excavation joined up with one of these probes, located east of the town wall next to the north tower. My new excavation covered an area of approximately 4 dunams (one acre) revealing a series of dwellings with over thirty rooms (Fig. 1.72).1

Three major phases of construction were found in this area: the earliest phase dates to the first century CE, the second phase dates to the second century CE and the third phase dates to the late third or early fourth century CE.

The earliest phase of construction includes three rooms of an early structure excavated on the eastern edge of the investigated area (Fig. 1.73). This building was constructed around a large central courtyard utilizing a few massive dressed stones similar to Nabataean buildings found in isolated areas west of Oboda (Haiman 1993:15). This structure appears to have been in use in the first and second century CE and in the fourth century. Debris was dumped in some of the rooms on its south end.

The structure constructed in the second phase was found in the eastern part of the excavated area and coins found under the floor level of this dwelling indicate that it was constructed in the second century CE (Fig. 1.74). The latest coins from this structure date to the late second and early third century CE. The date of the pottery found in this building indicates that it was occupied through the second century and into the first half of the third century when it was abandoned.

Four extant rooms and an adjoining courtyard were found in this building. The building was accessed through a doorway facing east. A second doorway along the western wall of the building was blocked, possibly when the room was filled after the building was abandoned. Two rooms, including the room on the east side of the building, Room 13, appear to have been purposely filled to nearly their full height. The walls in these rooms were the highest extant structures found in the excavation area. The fill was clean for the most part but a rather large amount of second and early third century pottery was found in the upper layers of the room (Fig. 1.75). The ‘entrance’ room leading into the structure from the east had a floor made of small sized field stones over which earth was placed. In the earthen floor of the next room, Room 12, a ceramic krater was found sunk into the soil partially below the surface.

The courtyard was situated on the northern side of the structure and enclosed along its eastern side with a wall containing an entrance. Remains of a stone water channel were found in the courtyard leading away from the structure to the west. On the western side of the building, a small chamber, measuring 1.5 x 2 m. under a stairwell of the structure, appears to have served as a pantry and nearly 80 whole and complete pottery and glass vessels were found stacked inside the room along with large animal bones that were apparently the remains of pieces of salted meat hanging under the stairs and above the shelves (Fig.1.76). The shelves, probably made of wood, had long since disintegrated. The findings suggest that the abandonment of the pantry with its contents intact may indicate a rapid desertion of the building, possibly as the result of an epidemic. The two main rooms of the structure were filled to nearly their full height sometime after the abandonment of the house. In the fourth century thin plaster floors were constructed above the fill (Fig.1.75). Only one room of the structure (Room 7) appears to have been utilized in the fourth century and it apparently collapsed in the 363 earthquake. Above the collapse layer, which filled the room to its full height, the surface was used in the late fourth century. Restorable pottery vessels of the type found in the pantry were found in the fill of the abandoned rooms of the house, Rooms 12 and 13. Among these vessels a small bronze statuette (Figs. 3.1-2) and part of a ceramic female figurine were found. The bronze statuette is similar to fragments of a bronze statuette found in the ruins of the temple treasury on the acropolis at Oboda (Rosenthal Heginbottom 1997: Pl.1:5-6). The ceramic figurine of a pregnant female appears to have been of Nabataen origin: an identical fragment was found by the writer at nearby H. Hazaza and complete examples have been found at Jerash (Iliffe 1945:Pl.IV: 55). In Phase 3, in the late third or early fourth century, the area between the structures described above and the tower was built up and occupied, probably in wake of the construction of the tower in the late third century (Fig. 1.77). Some evidence was found suggesting that the buildings in Phase 3 sustained structural damage, possibly as a result of the earthquake of 363. In Room 4 a row of fallen arch stones were found buried beneath the latest floor of the room (Fig. 1.78, upper). Doorways leading from this room into Rooms 3 and 7 were blocked and Room 7 was found filled with collapsed building stones, loose soil, rubble and air pockets. Two intact vessels were found in a protected corner of the floor of Room 7 (Figs. 4.7, 4.26) and coins and other items over the floor show that the room, built in Phase 2 of the building, was later floor surface, remains of reoccupied and utilized until around 363 CE.

Above the collapse layer of Room 7, braziers and in situ pottery were found, approximately at the same level as the plaster floor surface found in the latest phase of occupation overlying Room 13 (Fig. 1.78). Blocked doorways were also found between Rooms 10 and 17 on the north side of the complex and between Rooms 5 and 15. Traces of an earlier sublevel dating to the fourth century were found in Rooms 5 and 17.

The latest occupation of the Phase 3 complex displays a narrow walkway that ran from east to west towards the tower and at least five simple dwellings that were constructed on either side of the walkway. These dwellings had irregular plans with the main feature being a raised central courtyard surrounded by rooms constructed at a lower level. Rooms at lower levels were accessed by way of stairs. This feature was noted by the writer in fourth century CE structures in the Roman camp in Humayma in southern Jordan during a tour there with the excavator, J.P. Oleson, in 2001.

Courtyards in the buildings and outside of the complex appear to have been used for cooking and industrial purposes. The stone foundation of a large oven was found in the corner of Room 38, which appears to have been a courtyard. A stone bench was found along the western wall of the courtyard opposite the oven. A courtyard area to the north of Room 11 contained two large clay tabuns. The central courtyards in each dwelling appear to have been used for cooking and the inverted upper halves of Gaza wine jars were found throughout the dwellings in use as braziers in courtyards and also in Room 16.

The dwellings in Phase 3 were quite simple and only a few rooms contained evidence of a higher quality of construction. Most of the rooms had dirt floors or traces of thin plastered floors. The exception was Room 11, which had a stone paved floor and a lintel stone containing a tabula ansata lacking any writing but with traces of what appears to be a man working an olive press. The lintel stone was found thrown onto the floor of the room. The only room with plastered walls was that of Room 23 in which a Nabataean inscription was found on pieces of the plaster written in ink by the plasterer himself (Fig.1.79). This room also contained arch springers along the walls. Arch springers were found along the walls of many but not all of the rooms in the complex and a few in situ stone slabs and a lintel were found in the collapse of Room 22 (Fig.1.80). It is assumed that many building stones and particularly ceiling slabs were stripped from the structure after its destruction. Numismatic and ceramic evidence found in the fourth century dwellings indicate that they were destroyed in a violent earthquake sometime in the late fourth or early fifth century CE and not as previously assumed in the earthquake of 363. Intact pottery vessels, braziers and oil lamps, such as a collection of oil lamps found in Room 16, were found in situ throughout the structures (Figs.1.81-1.82). Similar to Building XXV at Mampsis, the dwellings in this area were robbed out for building stone and left abandoned. The town wall and stone fences for livestock were later constructed above the ruins of the buildings on the western edge of the excavated area.

1 The numismatic finds were examined by H. Sokolov of the IAA. The coins and other metal finds were cleaned by the laboratories of the IAA under the direction of E. Altmark. Plans of the site were drawn by V. Essman and S. Persky. The glass finds from the excavation were examined and are being published by Y. Gorin-Rosen. The ceramic and small finds were drawn by A. Dudin and pottery reconstruction was carried out by S. Lavi. The faunal material from Room 6 is being examined by R. Kahatti. Photographs of the excavation and the finds were produced by C. Amit and T. Segiv. N.S. Paran and L. Shilov assisted in directing the excavation and sorting the finds.

On May 19th, 363 CE, a massive earthquake struck the East, causing great damage to cities and towns along the Syrian-African rift and as far away as the Mediterranean coast. Compared to other earthquakes in ancient times, this particular event was well documented in historical sources and in the archaeological record. In situ evidence from this event has been found in several sites in our region, at Petra and in the Negev sites at Mampsis, ‘En Hazeva and Oboda. This earthquake, whose epicenter was probably located in the northern Arava valley, did not destroy whole sites but caused considerable damage and subsequent reconstruction that can be identified in the archaeological record (Mazor and Korjenkov 2001: 130, 133).

The clearest in situ evidence for this event was found in Building XXV at Mampsis. This entire building, situated as it was on a hilltop, sustained such heavy damage that it was abandoned and never rebuilt. One room in this house was used as a kitchen that was apparently in use when the earthquake struck. As a result, nearly the entire contents of the kitchen was found in situ, at floor level, including evidence of objects that fell to the floor from shelves along two walls. The walls of the kitchen (Room 2) and an adjoining room (Room 1) were rather insubstantial additions to the original structure and unlike the earlier Nabataean walls constructed on bedrock, these walls were constructed in a shallow layer of soil. This inferior construction technique appears to have been a major contribution to the collapse of the kitchen.

‘En Hazeva was situated in the Arava valley itself, in close proximity to the epicenter. The effects on this site were truly devastating, and the Late Roman fort and army camp underwent massive renovations. This was particularly true in the case of the cavalry camp situated below the fort. The walls in this camp were constructed on shallow foundations in soil and as a result, the original structure appears to have been completely shattered. The bathhouse adjoining the camp was built more solidly, although it too contains substantial cracks and subsequent renovations. The fort, which was founded on the walls of earlier buildings on the tell, withstood the earthquake to some extent, but whole floors with crushed in situ pottery appear to have been abandoned and covered by new floor surfaces in the subsequent phase of occupation.

Oboda was situated much further from the rift valley and although it was affected by the earthquake in 363, recent excavations have shown that this damage was limited in scope. In the Late Roman Quarter, some structural damage and renovations were noted, but this event did not create massive devastation at the site as was earlier thought to have occurred.

The 363 earthquake has left valuable evidence of pottery and other finds from the mid-fourth century CE that will be discussed here. An examination of this evidence makes it immediately apparent that few pottery types survived the transition from the third century CE. However, much of the pottery, and particularly the lamps found at the three Negev sites, were still produced in the region of Petra and southern Jordan as in earlier centuries. This in itself implies a continuation of material and cultural ties between the Negev and southern Jordan, a relationship that was undoubtedly rejuvenated by the activity of the Late Roman army in the region in wake of the transfer of the Tenth Legion from Jerusalem to Aila.

Other forms of vessels, such as fine ware bowls and amphorae, were brought from abroad, usually from the Eastern Mediterranean region. The one overwhelming type of vessel in fourth century assemblages throughout the Negev was the Gaza wine jar, corresponding to Majcherek’s Form 2, dated 300-450 CE (Majcherek 1995:Pl.5, 167-168). This type of jar was produced in the Gaza and Ashkelon region as has recently been proved on the basis of recent petrographic studies (Fabian and Goren 2002:148-149). Gaza jars were circulating in the Central Negev to such a great extent that by 363 CE it was common to find it in secondary use as braziers.

Evidence of Roman military presence can be detected in the distribution of a small, wide-mouthed storage jar that appears to have been designed to ration out wine or some other liquid. This type of jar was found extensively at the fort in ‘En Hazeva, but also at Oboda.

In the examination of the historical sources concerning the third and fourth centuries it is obvious that although general information concerning developments in the East exists, very little of this information pertains to the history of the central Negev. In the face of this dearth of historical data, archaeological findings provide details with which to trace the development of the region in a crucial phase of its history. The following are the results of an examination of the archaeological evidence and the implications of this evidence as it pertains to the accelerated growth in settlement and agriculture that took place in the fourth century CE.

The Results of an Examination of the Material Evidence

Material evidence has been presented here from three sites: Mampsis, Oboda and Mezad ‘En Hazeva dating to the period between the early third and the early fifth century CE. This evidence, mainly in the form of ceramic assemblages, is important in different ways. First of all, the contexts in which the main assemblages were found were primary, “Pompeii-type” deposits, i.e. the material was deposited together, abandoned and sealed as opposed to deposits of archaeological material added to over a number of years in a tomb, or thrown as refuse into a well or midden. Sealed, primary deposits provide rare data on the actual quantity and types of wares used simultaneously. Secondly, when the material from these three assemblages are studied together, patterns emerge that can shed light on economic and cultural trends. These patterns and other clues derived from the archaeological record mount in importance when historical evidence, particularly at a local level, is lacking for a particular region, as in this case the central Negev during the period under discussion. The results of studying these assemblages may be summed up as follows (Figs.1.90-91):

- The pottery assemblage dated to the first half of the third century CE is radically different in type and quality from the assemblage of the mid-fourth century. Vessels from the earlier assemblage reflect the international long distance trade of luxury goods passing through the central Negev, and particularly unguents produced and packaged in Petra. Nabataean fine wares produced in Petra, Eastern Terra Sigillata wares produced abroad and glass vessels from as far away as Nubia and Dura Europos were circulating through the region until the early to middle third century CE.

- Material evidence in the form of inscriptions found at Oboda and the continuous archaeological record found at Mampsis both indicate that the settlements in the central Negev were not abandoned during the third century. A tradition of local pottery production continued throughout this period and some local plain ware types survived well into the fourth century CE. The region appears to have been cut off from international trade and fine wares produced abroad were no longer reaching the area until after the Diocletianic period (Figs.1.64-65).

- The ceramic assemblage in the fourth century reflects new economic activity that replaced the long distance trade of the earlier period. The new economy was based on inter-regional trade of agricultural produce and particularly the production of wine. Wine jars produced in the region of Gaza and Ashkelon circulated with increased frequency through the region by the mid-fourth century and these jars are among the through the region by the mid-fourth century and these jars are among the most common vessels found at sites throughout the region in this period. Other vessels produced outside the Negev, such as African Red Slipped wares and Beit Natif style lamps, begin to appear in the Negev towards the middle of the century.

- The economic and cultural ties between the Negev and Petra continued in the fourth century and were revitalized by the regional build-up of the Roman army from the time of Diocletian. Pottery of a lower quality produced in Petra continued to flow into the Negev towns until the earthquake of 363 CE.

- By the early fifth century CE, the ties with Petra and southern Jordan began to wane and local pottery production increased. There are some indications that more pottery began to arrive from of what is central and northern Israel and Transjordan. The circulation of Gaza wine jars in the towns of the central Negev increased to such a great extent that they are often found in secondary use as braziers. Rare evidence of the survival of Nabataean language and religion is found at Oboda.

In 1999–2000 an area located east of the Byzantine town wall and the north tower at Oboda was excavated on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The excavation was directed by T. Erickson-Gini. It revealed a residential quarter with a series of dwellings covering an area of approximately 0.25 a.

Three definitive architectural phases were revealed in the residential quarter. To the first phase belong three rooms of an early structure (rooms 24, 27–28, 44) located on the eastern edge of the area and dated to the first century CE, possibly a Nabatean caravansary or residential structure. Some of the stones used in this structure were very large and the building appears to have covered an area of at least 40 sq m, including a large central courtyard.

A house and courtyard 19 from the second phase (rooms 6–7, 12–13) were uncovered a few meters west of this early building. The walls were preserved to almost their full height and a stone-lined channel was located in the courtyard. A coarse ware krater of a type generally dated to the later first century CE was buried below the earthen floor in an interior room. Coins found below floors of other rooms in the house date to the late second–early third centuries CE. The pottery recovered in the building indicates that it was occupied from the late first or early second centuries CE until its abandonment in the early third century. A small bronze statuette was found in room 13. A small chamber located under a stairwell in this structure appears to have served as a pantry (room 6). It contained at least 60 complete pottery and glass vessels that appear to have been stacked on wooden shelves, including late Nabatean painted ware bowls, Nabatean unguentaria, and Eastern terra sigillata wares, together with vessels dated to the early third century CE. Several Nabatean and Late Roman cooking pots were also uncovered. Large animal bones were found in the upper layer of this deposit, possibly cuts of salted meat that hung above the shelves. The material finds from this phase belong to the latest period of international trade along the Petra–Gaza road and include the latest form of Nabatean unguentaria, used to package perfumed oils produced at Petra before the collapse of international trade routes through Arabia, Egypt, and Syria in the third century CE.

The architecture and material finds from the third occupational phase, dating to the fourth century CE, differ radically from those found in earlier phases. The change appears to be the result of the shift in the economic base of the inhabitants of the site by the end of the third century CE, when they were compelled to turn to agricultural production following the col lapse of international trade through the region. In this phase, three rooms of the earlier house were completely filled in, and thin plaster floors were laid over the fill (rooms 6, 12–13). Only one room of the earlier structure appears to have been utilized in the fourth century CE (room 7), and it apparently collapsed in the 363 earthquake. The surface above the collapsed debris, which filled this room to its full height, was used late in that century.

Also during this phase, starting around 300 CE, the area between the earlier structures and the northern tower, which was probably constructed in the late third century CE, was built up and occupied. A narrow alley ran from east to west towards the tower; at least five simple dwellings were constructed on either side of it. These dwellings had irregular plans, their main feature being a raised central courtyard surrounded by rooms cut into the bedrock. Earthen floors over bedrock were encountered in all the rooms except for one (room 11), which was stone paved. A stone lintel with a tabula ansata was found on the floor of this room. A primitive depiction of a man working an olive-oil press was scratched onto the stone. Several rooms contained arch springers and evidence of ceilings constructed of stone slabs. Glass windowpanes were found near one of the dwellings. Some structural damage, probably resulting from the 363 CE earthquake, is evident in the blockage of a few doorways and the collapse of one of the rooms, as described above (rooms 4, 7, 17). On one of the plaster walls of room 23 were several lines of Nabatean script written in black ink. This inscription, found in a context dated to the late fourth or early fifth century CE, is the latest known Nabatean inscription in the Negev. The translation of the inscription reads: “In good memory and peace from Dushara. To our Lord Senogovia. [?]. Gadio his son. Plasterer. Nani.”

A courtyard area to the northeast of these dwellings contained two large clay tabuns. In the courtyard of one dwelling (room 38), the stone base of a large oven and stone workbench were found. The central courtyards of the dwellings were apparently used for food preparation, as the upper halves of Gaza wine jars dating to the fourth century CE were used as braziers in all the courtyards. Intact pottery vessels and oil lamps were found in situ throughout the houses. Other finds from this phase include grinding stones, bronze spatulae, and glass bracelets. fully integrated into the inter-regional trade of agricultural produce, particularly wine, by the end of the fourth century.

The numismatic and ceramic evidence uncovered in this third phase indicate that the dwellings were destroyed in a violent earthquake several decades after that of 363 CE. Following this second, local earth quake, the area was abandoned and many of the building stones were robbed. The town wall, encountered above the ruins of the buildings on the western edge of the excavated area, was later constructed sometime in the early fifth century CE.

The 1999–2000 excavation of the residential quarter has provided a wealth of information about the site in the Early Roman through early Byzantine periods, during which the site appears to have been occupied continuously. In addition, the excavations revealed information concerning the important transitional phase in its history, when its inhabitants were forced to abandon their principal means of livelihood with the cessation of international trade through the region in the third century CE. The succeeding period in the fourth century CE witnessed the rapid expansion of agricultural production and inter-regional trade of agricultural products, particularly wine, in the wake of the large-scale Late Roman military build-up in the eastern provinces. At Oboda this military build-up may be reflected in the erecting of the southern and possibly northern tower around 293/4 CE, as well as the construction of the large military camp located northeast of the acropolis. (This camp was excavated extensively in 1999–2000 on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority.)

An examination of the ceramic finds reveals that the economic transition that took place in the third and early fourth centuries CE did not affect ties between the inhabitants of the site and Petra and southern Jordan. A decline in wares originating in southern Jordan found at Oboda in the later fourth century appears to have occurred in the period following the 363 CE earthquake. By the beginning of the fifth century CE, when the residential quarter was destroyed and abandoned, Oboda had already become fully integrated into the inter-regional economic network of southern Palestine.

Erickson-Gini (2010:87-88) reports that

Avbat/Oboda sustained some damage in the 363 earthquake

. In the Late Roman/Early Byzantine Residential Quarter,

Erickson-Gini (2010:91-95) reports that Room 7

apparently collapsed in the 363 earthquake

as it was found filled with collapsed building stones, loose soil, rubble and air pockets.

Further structural damage was indicated in

Room 4 where a row of fallen arch stones were found

and doorways between Room 4 and Rooms 3 and 7 were blocked.

Tali Erickson-Gini in Stern et al (2008:1984-1985)

also reported a blocked doorway(s) in Room 17 and possibly Room 7 as well. Dating of the collapse in Room 7 may have been assisted via pottery, coins, and other items which were recovered in a protected corner

of the room (Erickson-Gini, 2010:91-95).

- Fig. 1 Aerial Overview of

Avdat from Zion et al (2022)

Figure 1

Avdat, looking east

- Army Camp from Roman Period

- Residential District

- Acropolis

- Cave City Avdat - W slope

- Cave City Avdat - E slope

- Orchards and Winepresses ?

- Orchards

- Orchards

- Orchards

- "Cave of the Saints"

(Photogrammetry: Yaakov Shmidov).

Zion et al (2022) - Late Roman/early Byzantine

quarter occupational phases and room from Stern et al (2008)

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Stern et al (2008)

- Fig. 1 Aerial Overview of

Avdat from Zion et al (2022)

Figure 1

Avdat, looking east

- Army Camp from Roman Period

- Residential District

- Acropolis

- Cave City Avdat - W slope

- Cave City Avdat - E slope

- Orchards and Winepresses ?

- Orchards

- Orchards

- Orchards

- "Cave of the Saints"

(Photogrammetry: Yaakov Shmidov).

Zion et al (2022) - Late Roman/early Byzantine

quarter occupational phases and room from Stern et al (2008)

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Late Roman/early Byzantine quarter occupational phases and rooms

Stern et al (2008)

- Fig. 1 Excavation Areas A, B,

and D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The excavation areas

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 3 plan of dipinti

Cave in Area D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 3

Plan 3

Area D, plan of the Dipinti Cave.

Erickson-Gini (2022)

- Fig. 1 Excavation Areas A, B,

and D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The excavation areas

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 3 plan of dipinti

Cave in Area D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 3

Plan 3

Area D, plan of the Dipinti Cave.

Erickson-Gini (2022)

- Fig. 1 Excavation Areas A, B,

and D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The excavation areas

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 1 Area A from

Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 1

Plan 1

Area A

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 2 Area B, plan

and sections from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 2

Plan 2

Area B, plan and sections

Erickson-Gini (2022)

- Fig. 1 Excavation Areas A, B,

and D from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

The excavation areas

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 1 Area A from

Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 1

Plan 1

Area A

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Plan 2 Area B, plan

and sections from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Plan 2

Plan 2

Area B, plan and sections

Erickson-Gini (2022)

- Fig. 2 Warped external wall

in Area A from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Area A, the warped external western wall (W1), looking southeast.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 8 Collapsed arches

and ceiling slabs in Room 1 of Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Area B, collapsed arches and ceiling slabs in Room 1, looking west.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 9 Rotated Blocks in

Room 1 of Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Area B, signs of rotation in the arch springer along W1 in Room 1.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 10 Arch Stone from

Room 1 in Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Area B, arch stone with incised, red-painted frame from the collapse in Room 1.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 11 Arch Stone from

Room 1 in Area B from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Area B, arch stone with incised, red-painted lines and frame from the collapse in Room 1.

Erickson-Gini (2022) - Fig. 16 Collapsed bedrock

shelf fronting cave above dipinti Cave from Erickson-Gini (2022)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

Area D, collapsed bedrock shelf fronting the cave above the Dipinti Cave, looking north.

Erickson-Gini (2022)

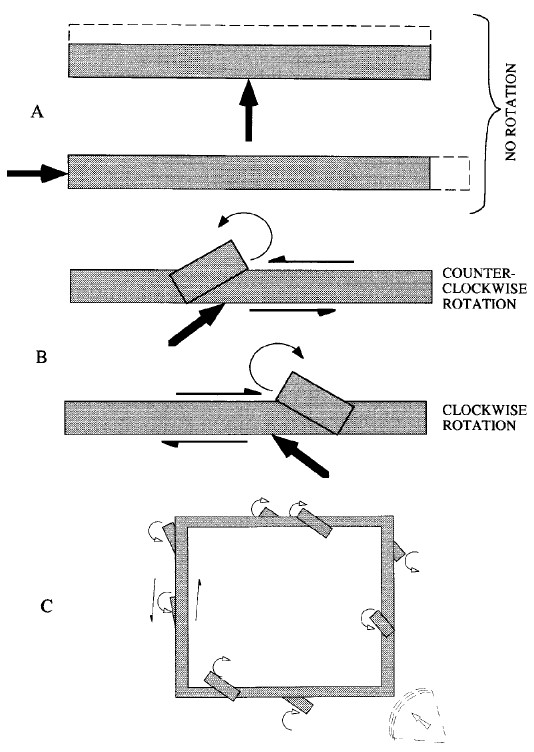

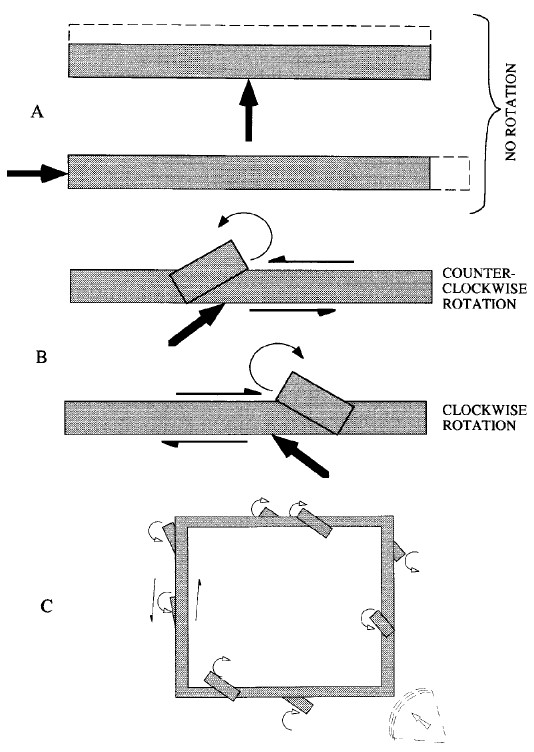

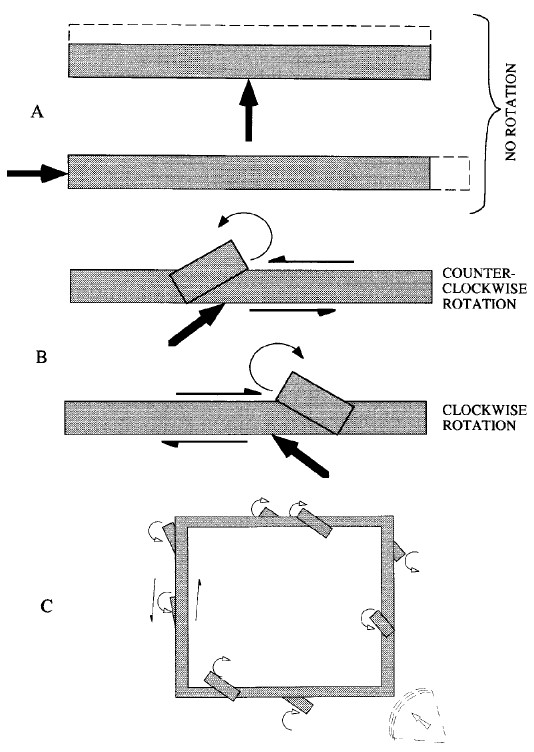

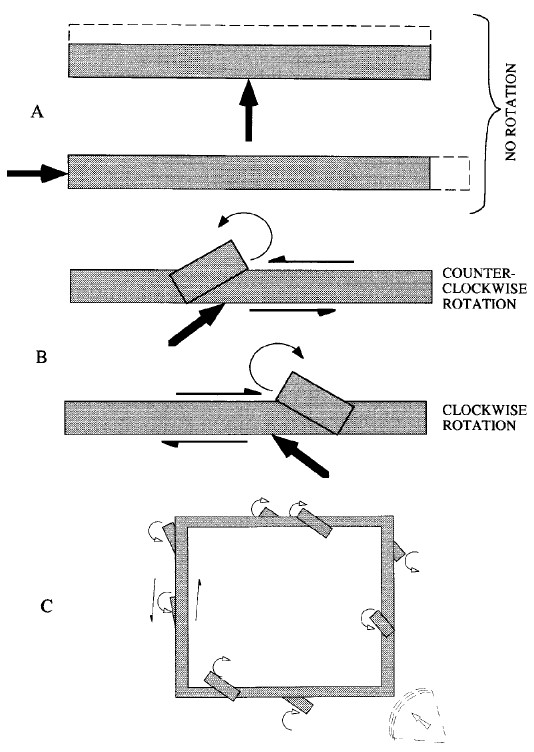

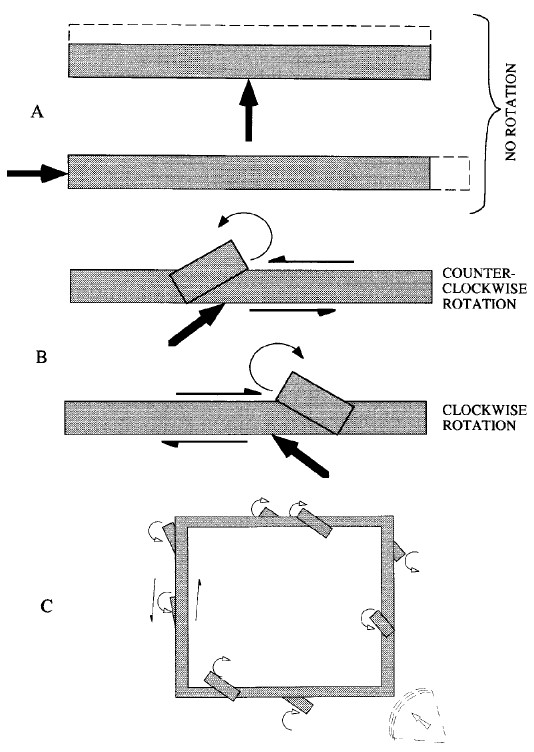

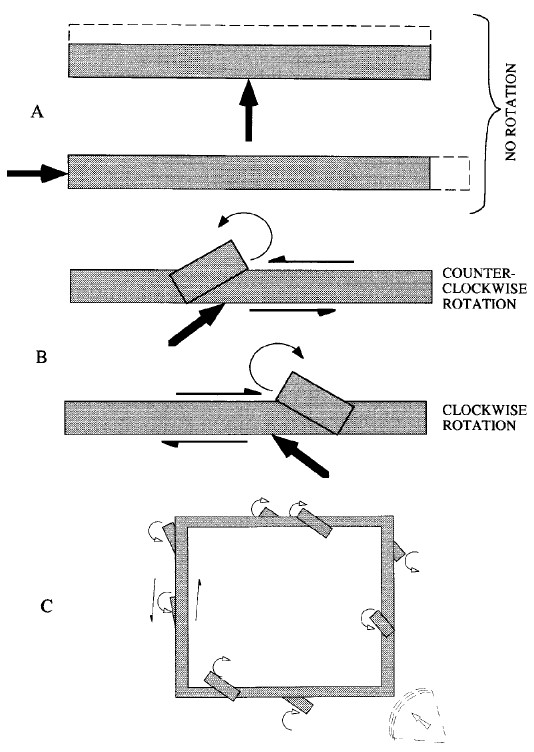

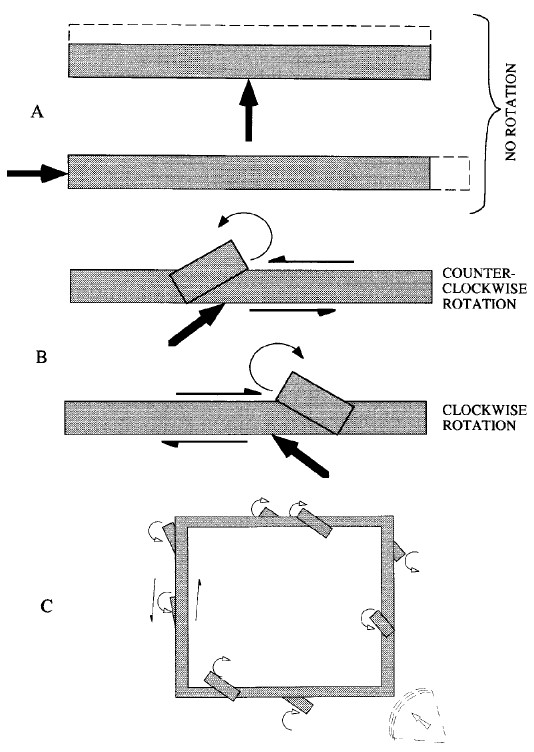

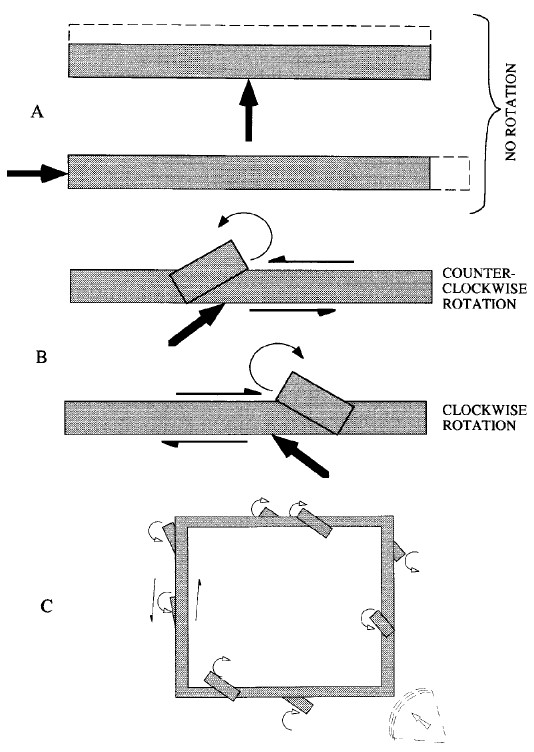

In 2012, salvage excavations were carried out in three areas in ‘Avedat National Park (Fig. 1), near and within the acropolis (Areas A, B; map ref. 178250/522720) and at the foot of the site’s western slope (Area D; map ref. 178188/522584).1 The excavations were initiated to facilitate restoration work (Area A) and following damage to the site when electric lines were dug to provide lighting for the acropolis (Area B).

Area A was opened in the western half of a room in a building located at the northwestern end of the main street of the ‘Roman Quarter’ (henceforce, ‘Roman/Byzantine Quarter’). Area B (50 sq m) was located along the northern exterior of a building south of the acropolis, near the South Church. Here, an exterior courtyard with a baking oven and pantry (Room 2) and the remains of another room (Room 1), were uncovered; all collapsed due to an earthquake sometime in the early seventh century CE. The probe in Area D was conducted along the southern exterior of a wall covered with red-painted dipinti, built in front of a cave.

- from Erickson-Gini (2022)

The ancient town of ‘Avedat (Greek: Oboda; Arabic: Abdeh), located along the Petra–Gaza road (popularly referred to as the ‘Incense Route’), shows evidence of seasonal occupation by the Nabataeans in the third–second centuries BCE, with extensive remains on the upper plateau overlying bedrock. In the late first century BCE, the Nabataeans built a temple dedicated to the deified king Obodas at the western end of the upper plateau, and a town was established on the eastern and southern parts of the site. Hundreds of caves were hewn into the western slope of the site, which was apparently a necropolis in pre-Christian times.

Following an earthquake in the early fifth century CE, settlement in the town shifted westward and many of the caves were converted for use as dwellings and stables. In the late Byzantine period (fifth–seventh centuries CE), two churches were built on the acropolis, where the earlier Western Temple had stood. In this period, a wall was built around the town and a citadel was added to the temenos area of the acropolis (Negev 1997:6–9).

... Evidence of destruction by earthquake, leading to the abandonment of the town in the seventh century CE, was exposed by Fabian in 1993 south of the acropolis in Building T (unpublished; Permit No. A-1991; but see Fabian 1996). In 1999, the author uncovered evidence of an early fifth-century CE earthquake destruction in a residential quarter situated east of the acropolis and the Middle Byzantine (450–550 CE) town wall (Erickson-Gini 2010:91–95).