Masada

Aerial View of Masada looking south. In the foreground is the northern section discussed by Netzer (1991)

Aerial View of Masada looking south. In the foreground is the northern section discussed by Netzer (1991)Wikipedia - Andrew Shivta - SA 4.0

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Masada | Hebrew | מצדה |

| Hebrew | מִדְבַּר יְהוּדָה | |

| Arabic | صحراء يهودا | |

| Hamesad | Aramaic | |

| Marda | Byzantine Greek | |

| Masada | Latin |

According to Josephus (in his book The Jewish War), the fortress at Masada was first built in Hasmonean times. Afterwards, King Herod built or rebuilt both a fortress and a refuge on the site. Masada's location, a veritable island atop steep walled cliffs, made it almost impregnable - until the Romans arrived. Again, according to Josephus, during the first Jewish war against Rome, the "Zealots" commandeered the fortress and were the last holdouts in that war when they collectively committed mass suicide rather than be taken captive in the spring of 74 CE. Afterwards, the Romans stationed a garrison on the site. The Romans eventually moved on and later a Byzantine Church and monastery were built there (Stern et al, 1993). After that, it was left abandoned and desolate until modern times. Masada may be subject to seismic amplification due to a topographic or ridge effect as well as a slope effect for those structures built adjacent to the site's steep cliffs.

Masada is situated on the top of an isolated rock cliff, on the border between the Judean Desert and the Dead Sea Valley, about 25 km (15.5 mi.) south of En-Gedi. On the east, the rock falls in a sheer drop of about 400 m to the Dead Sea. Its western side is about 100m above the surroundings. The cliff top is a rhomboid, measuring about 600 m north to south and 300m east to west in the center. Its highest parts are in the north and west. Masada's natural approaches are difficult: the White Rock on the west (the Leuke of Josephus, War VII, 305), the cliffs southern and northern sides, and the winding, so-called Snake Path on the east (Josephus, War VII, 282). The name Masada appears only in Greek (Μασαδα) or Latin transcriptions. It may be an Aramaic form of hamesad, "the fortress."

The only sources that describe Masada in detail are the writings of Josephus Flavius. According to War (VII, 285), the high priest Jonathan built the first fortress (φρουριον) at the site and called it Masada. Some scholars consider this Jonathan to have been Alexander Jannaeus, but in another passage (War IV, 399), the foundation of Masada is attributed to "ancient kings," referring to the Hasmoneans. This would point to Jonathan Maccabaeus, who became high priest in 153 or 152 BCE (1 Mace. 10: 15-21; Josephus, Antiq. XIII, 43- 46).

In 40 BCE, Herod, in flight from the pretender Antigonus and the Parthian army, led his family to the fortress of Masada, the defense of which he committed to his brother Joseph, with a following of eight hundred men (Antiq. XIV, 361-362; War I, 264, 266). During the siege by Antigonus, they escaped dying of thirst when a sudden rainfall filled the cisterns on the summit. Herod, on his return from Rome in 39 BCE, succeeded in rescuing them (Antiq. XIV, 390-391; 396, 400; War I, 286-287, 292-294). According to War VII, 300,

Herod furnished this fortress as a refuge for himself, suspecting a twofold danger: peril on the one hand from the Jewish people, lest they should depose him and restore their former dynasty to power; the greater and more serious from Cleopatra, queen of Egypt.Thus, he probably began building his fortress between 37 and 31 BCE. Although there is no information about Masada immediately after Herod's death, it seems probable that a Roman garrison was stationed here. In any event, such was the case in 66 CE, when the site was captured "by stratagem" by Zealots and its armory plundered by one of their leaders, Menahem, the son of Judah the Galilean (War II, 408, 433). After Menahem was murdered in Jerusalem, his nephew, Eleazar son of Jair, son of Judah, fled to Masada and was its "tyrant" until its fall in 74 CE (War II, 447; VII 252-253). During this time, Masada served as a refuge for the persecuted. Simon the son of Giora, another rebel leader, also stayed here for a time (War II, 653). In 73 CE, the Roman governor Flavius Silva marched against Masada with the Tenth Legion, its auxiliary troops, and thousands of Jewish prisoners of war. After Masada's conquest in spring 74, Silva left a garrison at the site (War VII, 252, 27 5-279, 304-407). Masada is also briefly mentioned by Pliny in Natural History (V, 73).

The extensive preparations made by Flavius Silva to conquer Masada are still visible in the fortress's surroundings: the siege wall (circumvallation), camps, and assault ramp. S. Gutman excavated part of camp A, and trial soundings were made by Yadin's expedition in camp F, the large camp northwest of the rock and Silva's command headquarters. The main aim of the expedition was to determine the date of the smaller camp, situated in the southwest corner of camp F. It was established that this small camp was built by the garrison left at the site after the conquest of Masada. All the finds from the second (upper) of its two floors are attributed to the end of the first and beginning of the second centuries. The latest coin found here is from 105 CE.

Part of the garrison was also stationed on the summit of Masada. Stratigraphic evidence of the fall of Masada was provided by occupation levels above the conflagration layers, found mainly in buildings IX and VII, in the large bathhouse, and in some of the casemates, particularly on the northwest side.

In other places, signs of the destruction apparently carried out by the Roman garrison were noted. A group of silver coins from those levels was discovered on the north side of building VII. The latest coin in this group dates to 111 CE, attesting to the length of the Roman occupation. In various places on the summit some Nabatean bowls were found that are to be attributed either to the period of the revolt or to the Roman garrison. Large quantities of this type of pottery were also discovered in all the Roman camps. It seems likely that the garrison and siege troops included Nabatean soldiers, and that this pottery was used at least until 73 CE.

Masada was correctly identified for the first time with the rock es-Sebba in May 1838 by the Americans E. Robinson and E. Smith. They did not visit Masada but viewed its northern cliff through a telescope from En-Gedi. Smith suggested identifying the site with Masada. Robinson believed that the building visible on the northern cliff was Herod's palace. In 1842, the American missionary S. W. Wolcott and the English painter Tipping visited Masada and left amazingly accurate descriptions and drawings. In April 1848, an expedition sent by the American naval officer J. W. Lynch visited the site, anchoring off the Dead Sea coast. They were the first to identify the "holes" in the northwestern cliff as water reservoirs and noted the "square structure" (that is, the lower terrace of the Northern Palace). The French antiquarian F. de Saulcy visited Masada in January 1851. He dug in the Byzantine chapel, finding remains of its mosaic floor. He also drew the first plan of Masada and the Roman camps. The Frenchman, E. G. Rey, visited Masada in January 1858, and correctly attributed the mosaic remains from the upper terrace to Herod's palace.

A turning point in the exploration of Masada came with the British Survey of Western Palestine. In 1867, C. Warren climbed Masada from the east, tracing the Snake Path for the first time. After surveying the site in March 1875, C. R. Conder published more accurate plans of the buildings and the Roman camps. It was Conder who first suggested identifying (erroneously) the western building with Herod's palace.

The first detailed study of the Roman camps was carried out by the German scholar A. V. Domaszewski. In 1909, he and R. E. Brunnow published their studies in Die Provincia Arabia. Domaszewski mainly studied camps Band C (see below). Another German, G. D. Sandel, visited Masada in 1905. He noted the water reservoirs in the northern cliff and observed that they were fed by canals that collected rainwater from the wadis. In 1929, the Englishman C. Hawkes advanced the study of the Roman camps, which he examined with the aid of aerial photographs.

However, the principal turning point in the investigation of the site was made by the German A. Schulten, who spent a whole month at Masada in 1932. His plans of the building and of the Roman camps laid the foundation for all later studies. Schulten, however, made some fundamental mistakes in his conclusions. He attempted, for example, to locate the Snake Path in the north, concluding that the buildings on the three terraces in the north were fortifications connected with it. He also agreed with Conder's mistaken proposal that Herod's palace, described by Josephus, should be identified with the western building.

Later studies of Masada, which culminated in the excavation of the site, were carried out by enthusiastic Israeli scholars and amateurs, foremost among them S. Gutman. He traced the exact line of the Snake Path and, together with A. Alon, examined Herod's water system (1953). Gutman also discovered and restored the gate of the Snake Path and partly excavated and reconstructed the Roman camps (A and C). A.M. Livneh and Z. Meshel, in 1953, published the first nearly accurate plans of the buildings on the northern terraces, correctly identifying them with Herod's palace. As a result of these discoveries, survey expeditions were organized on behalf of the Israel Exploration Society, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums. One expedition, directed by M. Avi-Yonah, N. Avigad, J. Aviram, Y. Aharoni, S. Gutman, and I. Dunayevsky, surveyed the site for ten days in March 1956. These investigations confirmed the identification of the structures on the northern cliff with Herod's palace and added to the information on the storehouses and "the western building." A new detailed map of Masada was also prepared.

Excavations were conducted at Masada under the direction of Y. Yadin from October 1963 to April 1964 and again from December 1964 to March 1965. The permanent staff members included D. Bahat, M. Batyevsky, A. Ben-Tor, I. Dunayevsky, G. Foerster, S. Gutman, E. Menczel (Netzer), and D. Ussishkin. In these excavations almost all of the built-up area of Masada was uncovered, and a trial sounding was made in camp F.

By the time the final report on the Masada excavations was published, in 1991, a clearer and somewhat different picture had emerged of the stratigraphy and development of its buildings. It was concluded that the history of construction on Masada under Herod could be divided into three phases. This conclusion was corroborated both by a few additional soundings conducted here by Netzer in 1989 and by work at other sites (mainly at the winter palaces from the Second Temple period in the western Jericho Valley).

Supplementary excavations were conducted by E. Netzer and G. Stiebel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem upon the summit of Masada over several seasons spanning 1995–2000, as part of a development project undertaken by the Israel Ministry of Tourism and the Nature and Parks Authority. It followed a short season conducted by Netzer in 1989. Main discoveries in the latest excavations at Masada are floors and assemblages datable to the Herodian period. The rich epigraphic finds include bilingual (Greek and Latin) inscriptions and ostraca from the time of the First Jewish Revolt. These may shed further light on the rebels’ communal life. New information has emerged concerning the entrances to the “acropolis” and on the area adjacent to the synagogue and cistern 1901.

The siege apparatus built by Flavius Silva as part of his campaign against the Masada rebels is one of the best preserved from ancient times. Its three main components (eight siege camps, circumvallation wall, and assault ramp) are still visible and well-preserved today, providing evidence for the Roman army’s methods of operation. The siege works indicate careful planning and adaptation to the region’s extreme climate and topography. The Roman army presumably arrived at the site during the more hospitable winter season. Upon their arrival, the eight siege camps were erected at strategic points around the fortress. A siege or circumvallation wall, 1.5 m wide and 4.6 km long, was then constructed, connecting the camps while encircling the entire outcrop of Masada. The northern and eastern portions of this array were strengthened by roughly 13 watchtowers to compensate for the flat terrain. The purpose of this wall was to isolate the fortress and give the Romans complete control over movements to and from the blockaded area. Access was provided by means of gateways in the wall just opposite camp C, and apparently also near the “engineering yard” west of the assault ramp.

Two symmetrical sectors of the siege works can be observed. The eastern sector consists of a relatively flat area, c. 400 m below the top of the fortress. This sector was enclosed by the circumvallation wall and towers extending from the main rift-line north of Masada, along the edge of the deeply furrowed marl plains and back to the rift-line southeast of the fortress. Three small siege camps (A, C, D) were built along this stretch of the circumvallation at key points, from which the paths descending from Masada and the riverbeds around it could be observed. A larger camp (B) was set up further back from the siege line, behind camp A. It probably served as the main command post and logistical center for the entire eastern sector.

The western sector consisted of the entire relatively high area located above the fault-line cliff, extending from above the northernmost point of the eastern sector, through the furrowed and undulating area west of Masada to the fault-line southeast of the fortress. On this side, the circumvallation occasionally rises to elevations higher than even Masada itself. In this spot, as in the eastern sector, four siege camps were erected. Three small camps (E, G, and H) connected by the circumvallation wall were located at key points from which necessary crossing points could be observed. Also in the western sector a fourth larger camp was built, at some distance to the rear of the circumvallation. This camp has commonly been identified as the command post of the Roman general Flavius Silva. The most prominent component of the siege installations in the western sector is the assault ramp. It appears as a whitish, earthen rise, broad at the bottom and narrowing as it rises at a uniform slope and ends c. 13 m below the top of Masada’s precipice. The assault ramp was a vital element in the Roman offensive.

Prominent studies of the Masada siege array have been conducted by R. E. Brünnow and A. von Domaszewski (1909), C. Hawkes (1929), A. Schulten (1933), I. A. Richmond (1962), S. Gutman (1965), and Y. Yadin (1966). Most of these are theoretical, historical, and comparative studies based on an analysis of general plans, measurements, and aerial photos, rather than on results of actual comprehensive and detailed archaeological research. Limited excavations of the siege installations were carried out by Gutman at camp A and Yadin at camp F. New survey and excavations of the siege array were initiated during the summer of 1995 by B. Arubas, H. Goldfus, and G. Foerster on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and by J. Magness on behalf of Tufts University. Excavations have thus far taken place at camp F and on the assault ramp.

- Annotated Satellite Image

of Masada from biblewalks.com

- Masada in Google Earth

- Masada on govmap.gov.il

- Model of Masada from

biblewalks.com

- Model of Herod's Palace from

biblewalks.com

- Fig. 10 Model of Camp A

from Ashkenazi et al. (2024)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Camp A (arrows mark staircases)

(After Gutman 1965, 109)

Ashkenazi et al. (2024)

- Map of Masada from

. Wikipedia

Site Plan

- Snake Path gate

- Rebel dwellings

- Byzantine monastic cave

- eastern water cistern

- rebel dwellings

- mikvah

- southern gate

- rebel dwellings

- southern water cistern

- southern fort

- swimming pool

- small palace

- round columbarium tower

- mosaic workshop

- small palace

- small palace

- stepped pool

- Western Palace: service area

- Western Palace: residential area

- Western Palace: storerooms

- Western Palace: administrative area

- tanners' tower

- western Byzantine gate

- columbarium towers

- synagogue

- Byzantine church

- barracks

- Northern complex: grand residence

- Northern complex: quarry

- Northern complex: commandant's headquarters

- Northern complex: tower

- Northern complex: administration building

- Northern complex: gate

- Northern complex: storerooms

- Northern complex: bathhouse

- Northern complex: water gate

- Northern Palace: upper terrace

- Northern Palace: middle terrace

- Northern Palace: lower terrace

- ostraca cache found in casemate

- Herod's throne room

- colorful mosaic

- Roman breaching point

- coin cache found

- ostraca cache found

- three skeletons found

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 - Fig. 18 Plan of Masada

from Magness ((2019)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Plan of Masada

Magness ((2019) - Site Map of Masada

from Israel Nature and Parks Authority

Site Map of Masada

Site Map of Masada

Israel Nature and Parks Authority - Fig. 1 Masada circumvallation

wall and its sections from Ashkenazi et al. (2024)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Masada circumvallation wall and its sections

(Drawing by H. Ashkenazi, Base Map after Netzer 1991, Plan A.)

Ashkenazi et al. (2024)

- from Wikipedia

- Map of Masada from

Wikipedia

Site Plan

- Snake Path gate

- Rebel dwellings

- Byzantine monastic cave

- eastern water cistern

- rebel dwellings

- mikvah

- southern gate

- rebel dwellings

- southern water cistern

- southern fort

- swimming pool

- small palace

- round columbarium tower

- mosaic workshop

- small palace

- small palace

- stepped pool

- Western Palace: service area

- Western Palace: residential area

- Western Palace: storerooms

- Western Palace: administrative area

- tanners' tower

- western Byzantine gate

- columbarium towers

- synagogue

- Byzantine church

- barracks

- Northern complex: grand residence

- Northern complex: quarry

- Northern complex: commandant's headquarters

- Northern complex: tower

- Northern complex: administration building

- Northern complex: gate

- Northern complex: storerooms

- Northern complex: bathhouse

- Northern complex: water gate

- Northern Palace: upper terrace

- Northern Palace: middle terrace

- Northern Palace: lower terrace

- ostraca cache found in casemate

- Herod's throne room

- colorful mosaic

- Roman breaching point

- coin cache found

- ostraca cache found

- three skeletons found

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 - Fig. 18 Plan of Masada

from Magness ((2019)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Plan of Masada

Magness ((2019) - Site Map of Masada

from Israel Nature and Parks Authority

Site Map of Masada

Site Map of Masada

Israel Nature and Parks Authority - Fig. 1 Masada

circumvallation wall and its sections from Ashkenazi et al. (2024)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Masada circumvallation wall and its sections

(Drawing by H. Ashkenazi, Base Map after Netzer 1991, Plan A.)

Ashkenazi et al. (2024)

- Plan of Roman camps

F1 and F2 from Stern et. al. (2008)

Plan of Roman camps F1 and F2

Plan of Roman camps F1 and F2

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Plan of Roman camps

F1 and F2 from Stern et. al. (2008)

Plan of Roman camps F1 and F2

Plan of Roman camps F1 and F2

Stern et. al. (2008)

- from Netzer (1991:xv)

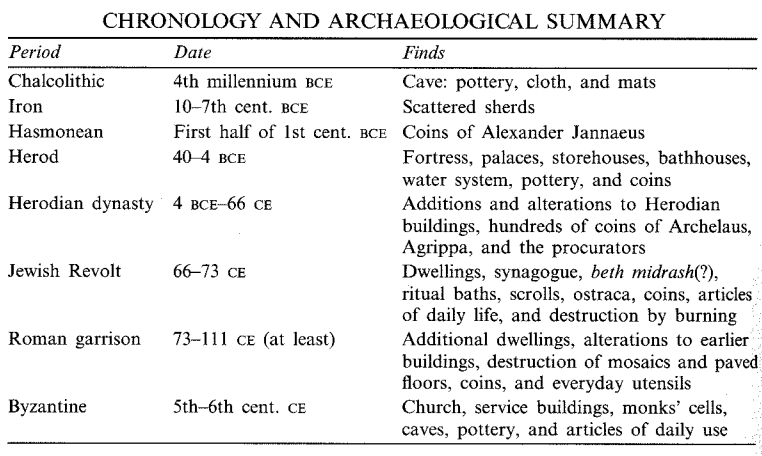

| Period | Start Date | End Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hasmonean | The phase of Masada's existence about which very little is known as yet |

||

| Early Herodian building phase | ca. 37 BCE | ca. 30 BCE | the proposed datessubdividing the Herodian period are tentative |

| Main Herodian building phase | ca. 30 BCE | ca. 20 BCE | |

| Late Herodian building phase | ca. 20 BCE | ca. 4 BCE | The reign of Archelaus (4 BCE -6 CE), Herod's son, should, for all practical purposes, be included in the Herodian period. |

| Procurators | 6 CE | 66 CE | from the year 6 CE (the end of Archelaus' reign) to 66 CE, the year of Masada's occupation by the Zealots. This period includes the brief reign of Agrippa I in Judea from 41-44 CE. |

| Zealots | 66 CE | 73 CE | from the arrival of the Zealots in 66 CE to the site's destruction ca. 73 CE |

| Post-Zealot | 73 CE | the occupation of Masada by the Roman garrison after it's destruction in ca. 73 CE |

|

| Byzantine |

during which Masada was occupied by a monastic community Yadin (1965:30) indicates that the Byzantine occupation occurred after the earthquakes. |

Chronology and Archaeological Summary of Masada

Chronology and Archaeological Summary of Masada

Yigal Yadin in Stern et al (1993 v. 3)

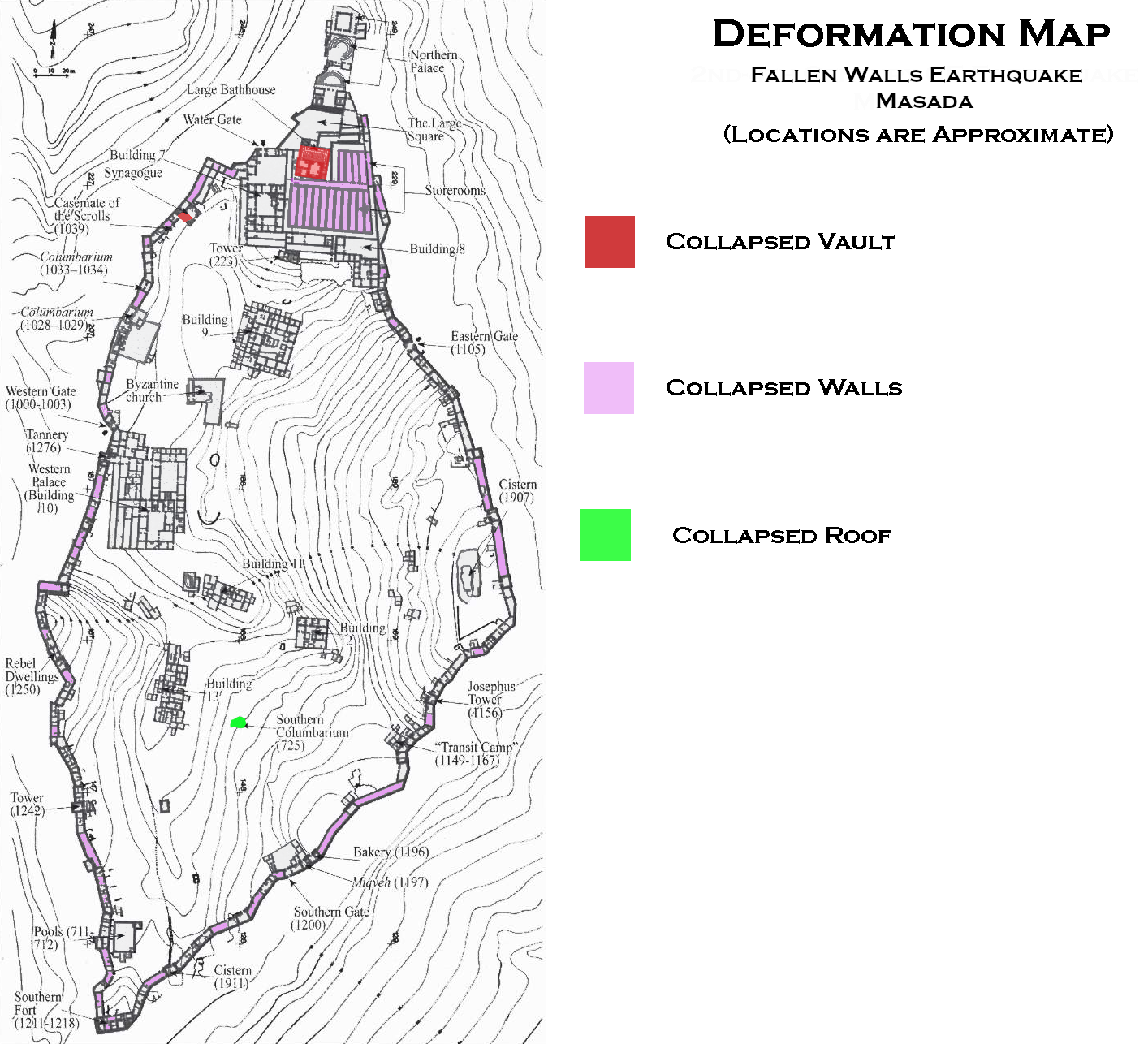

Netzer (1991:655) reports that a great earthquake [] destroyed

most of the walls on Masada sometime during the 2nd to 4th centuries

CE.

In an earlier publication, Yadin (1965:30) noted that the

Caldarium was filled as a result of earthquakes by massive debris of stones

.

Yadin concluded that the finds on the floors of the bath-house represent the last stage in the stay of the Roman garrison at Masada

.

The stationing of a Roman Garrison after the conquest of Masada in 73 or 74 CE

was reported by Josephus in his Book

The Jewish War where he says in Book VII Chapter 10 Paragraph 1

WHEN Masada was thus taken, the general left a garrison in the fortress to keep it, and he himself went away to Caesarea; for there were now no enemies left in the country, but it was all overthrown by so long a war.Yadin (1965:36)'s evidence for proof of the stationing of the Roman garrison follows:

We have clear proof that the bath-house was in use in the period of the Roman garrison - in particular, a number of "vouchers" written in Latin and coins which were found mainly in the ash waste of the furnace (locus 126, see p. 42). Of particular importance is a coin from the time of Trajan, found in the caldarium, which was struck at Tiberias towards the end of the first century C.E.*The latest coin discovered from this occupation phase was found in one of the northern rooms of Building VII and dates to 110/111 CE (Yadin, 1965:119)**. Yadin (1965:119) interpreted this to mean that, this meant that

the Roman garrison stayed at Masada at least till the year 111 and most probably several years later.Russell (1985) used this 110/111 coin as a terminus post quem for the Incense Road Earthquake while using a dedicatory inscription at Petra for a terminus ante quem of 114 CE.

*Yadin (1965:118) dated this coin to 99/100 CE -

This would be coin #3808 -

Plate 77 - Locus 104 -

Caldrium 104 - Square 228/F/3

**perhaps this is coin #3786 which dates to 109/110 CE -

Plate 77 -

Locus 157 - Building 7 Room 157 - Square 208/A/10

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Vault | Room 162 in the SW corner of Building No. 7

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

|

|

| Collapsed Walls | Storeroom Complex

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

Ill. 58

Ill. 58Core of Storeroom Complex at very beginning of excavations, looking west. Netzer (1991) |

|

|

Tepidarium 9

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

Ill. 258

Ill. 258Eastern wall of Tepidarium 9, looking southeast Netzer (1991) |

|

| Collapsed Vault | Caldarium

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

Ill. 145

Ill. 145Fallen section of barrel-vaulted ceiling of caldarium (104), looking northeast Netzer (1991) |

|

| Collapsed Roof | Columbarium Tower 725

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

Ill. 586

Ill. 586Wooden beams found in debris in the eastern half of Columbarium Tower 725, looking north. Netzer (1991) |

|

|

Cistern 1063 - Northwestern section of casemate wall

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

|

|

|

Room (Tower) 1260 - Southwestern section of casemate wall

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

|

|

| Collapsed walls | Walls of Masada

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 18 of Magness (2019)

- Only some archaeoseismic evidence was located

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Vault | Room 162 in the SW corner of Building No. 7

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

|

VIII + | |

| Collapsed Walls | Storeroom Complex

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

Ill. 58

Ill. 58Core of Storeroom Complex at very beginning of excavations, looking west. Netzer (1991) |

|

VIII + |

|

Tepidarium 9

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

Ill. 258

Ill. 258Eastern wall of Tepidarium 9, looking southeast Netzer (1991) |

|

|

| Collapsed Vault | Caldarium

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

Ill. 145

Ill. 145Fallen section of barrel-vaulted ceiling of caldarium (104), looking northeast Netzer (1991) |

|

VIII + |

| Collapsed Roof suggesting displaced walls | Columbarium Tower 725

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

Ill. 586

Ill. 586Wooden beams found in debris in the eastern half of Columbarium Tower 725, looking north. Netzer (1991) |

|

VII+ |

|

Cistern 1063 - Northwestern section of casemate wall

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

|

|

|

|

Room (Tower) 1260 - Southwestern section of casemate wall

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

|

|

|

| Collapsed walls | Walls of Masada

Fig. 18

Fig. 18Plan of Masada Magness ((2019)

Kordas - Wikipedia - SA 3.0 |

|

VIII + |

Ashkenazi H, Ze’evi-Berger O, Gross B, Stiebel GD. (2024) The Roman siege system of Masada: a 3D computerized analysis of a conflict landscape. Journal of Roman Archaeology

. Published online 2024:1-26. - open access

Hall, J. and Welch, J.W. (1997) Masada and the world of the New Testament - open access at archive.org

Kirkbride, D. (1960). A Short Account of the

Excavations at Petra in 1955-1956. Annual of the

Department of Antiquities of Jordan 4-5: 117-122.

Magness, J. (2019). Masada

From Jewish Revolt to Modern Myth, Princeton University Press. - at JSTOR

Netzer, E. (1997). "Masada from Foundation to Destruction: an Architectural History,”." Hurvitz, G.(szerk.):

The Story of Masada. Discoveries from the Excavations. Provo, UT: BYU Studies: 33-50.

Yadin, Y. (1966) Masada Herod's Fortress and the Zealouts Last Stand, London - can be borrowed with a free account from archive.org

Yadin, Y. (1965). "The excavation of Masada 1963-64,preliminary report." Israel Exploration J. 15(1-120).

Masada I - The Aramaic and Hebrew Ostraca and Jar Inscriptions, The Coins of Masada,

The Yigal Yadin Excavations 1963-1965 Final Reports, Israel Exploration Society. Yadin and Naveh (1989), Meshorer (1989)

Masada II - The Latin and Greek Documents,

The Yigal Yadin Excavations 1963-1965 Final Reports, Israel Exploration Society. Cotton and Geiger (1989)

Masada III: The Buildings, Stratigraphy and Architecture,

The Yigal Yadin Excavations 1963-1965 Final Reports, Israel Exploration Society. Netzer, E. (1991).

Masada IV Textiles, Lamps, Basketry and Cordage, Wood Remains, Ballista Balls, Appendum - Human Skeletal Remains

The Yigal Yadin Excavations 1963-1965 Final Reports, Israel Exploration Society.

Masada V - Art and Architecture,

The Yigal Yadin Excavations 1963-1965 Final Reports -

Israel Exploration Society, Jerusalem, Foerster, G. (1995)

Y. Yadin, Masada, London 1966; Masada 1-3, The Yigael Yadin Excavations 1963-

1965: Final Reports (The Masada Reports), Jerusalem 1989 to date:

Y. Yadin and J. Naveh, The Aramaic and Hebrew Ostraca and Jar Inscriptions

Y. Meshorer, The Coins of Masada (Masada 1), Jerusalem 1989

H. M. Cotton and J. Geiger, The Latin and Greek Documents (Masada 2), Jerusalem 1989

E. Netzer, The Buildings, Stratigraphy and Architecture (Masada 3), Jerusalem 1991.

Robinson, Biblical Researches 2

S. W. Wolcott, Bibliotheca Sacra 1, 1843 (also The History

of the Jewish War by Flavius Josephus, A New Translation, by R. Traill, Manchester 1851)

J. W. Lynch,

Narrative of the U.S. Expedition to the Jordan and the Dead Sea, Philadelphia 1849

S. W. M. VandeVelde,

Syria and Palestine, Edinburgh and London 1854

F. de Saulcy, Round the Dead Sea and in the Bible Lands,

London 1854

E. G. Rey, Voyages dans le Haouran et aux hordes de Ia Mer Marte, Paris 1860

R. Tuch,

Masada, die herodianische Felsenfeste nach Flavius Josephus und neuern Beobachten, Leipzig 1863

H. B.

Tristram, The Land of Israel, London 1865, passim

id., The Land of Moab, London 1873

ConderKitchener, SWP 3, 417-421

G. D. Sandel, ZDPV30 (1907), 96f.

Briinnow-Domaszewski, Die Provincia

Arabia 3, 220-244

C. Hawkes, Antiquity 3 (1929), 195-260;A. M. Schneider, OriensChristianus6(1931),

251-253

W. Bmie, JPOS 13 (1933), 140-146

A. Schulten, ZDPV 56 (1933), H85

0. Ploger, ZDPV71

(1955), 14H 72

M. Avi-Yonah et al., IEJ 7 (1957), 1-60

I. A. Richmond, JRS 52 (1962), 142-155;

Y. Yadin, IEJ 15 (1965), 1-120

id., The Ben Sira Scroll from Masada, Jerusalem 1965

id., Archaeology

(Israel Pocket Library), Jerusalem 1974, 150-164

id., Masada Revisited (4th Annual Louis A. Pincus

Memorial Lecture), New York 1977

id., ASR, 19-23

G. Cornfeld, This is Masada: A Guide Book, Tel

Aviv 1972

L. H. Feldman, Christianity, Judaism and Other Greco-Roman Cults (M. Smith Fest.) 3, Lei den

1975, 218-248

G. Foerster, Journal of Jewish Art 3-4 (1977), 6-11

id., ASR, 24-29

id., MdB 57 (1989),

9-14

A. Segal, Antike Welt 8 (1977), 21-28

D. Chen, BASOR 239 (1980), 37-40

J. Briend, MdB 17

(1981), 22-27

L. Liphschitz (et al.), IEJ31 (1981), 230-234

id. (and S. Lev-Yadun), BASOR 274 (1989),

27-32

S. J.D. Cohen, Journal of Jewish Studies 33 (1982), 385-405

Y. Tsafrir, Jerusalem Cathedra 2

(1982), 120-145

R. Knoxetal.,IEJ33 (1983), 97-107

R. Maddinetal., ibid., 108-109

C. Saulnier, MdB

29 (1983), 14-17

C. Newsome andY. Yadin, IEJ34 (1984), 77-88

J.P. Kane, BAlAS (1984-1985), 14-

19

E.-M. Laperrousaz, Revue des Etudes Juives 144 (1985), 297-304

id., Archeologie, Art et Histoire de Ia

Palestine: Colloque du Centenaire de Ia Section des Sciences Religieuse, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes,

Sept.1986, Paris 1988, 149-165

G. J. Brooke, Revue de Qumran 13/49-52(1988), 225-237

Weippert 1988

(Ortsregister)

H. M. Cotton and J. Geiger, Masada 2 (Review), Journal of Roman Archaeology 4 (1991),

336-344

G. Garbrecht and J. Pe1eg, Antike Welt 20/2 (1989), 2-20

J. Naveh, IEJ 40 (1990), 108-123;

D. B. Small, Levant 22 (1990), 139-147

D. Barag, Roman Glass: Two Centuries of Art and Invention (eds.

M. Newby and K. Painter), London 1991, 137-140

E. Netzer, BAR 17/6 (1991), 20-32.

Masada: The Yigael Yadin Excavations 1963–1965, Final Reports, IV: Lamps, Ballista

Balls, Wood Remains

Basketry, Cordage and Related Artifacts; Textiles; Human Skeletal Remains, by D.

Barag et al., Jerusalem 1994

ibid. (Reviews) Dead Sea Discoveries 3 (1996), 329–332. — JAOS 116 (1996),

539–540. — JRA 9 (1996), 355–357. — BAR 23/1 (1997), 58–63. — Orientalistische Literaturzeitung 93

(1998), 47–51

V: Art and Architecture, by G. Foerster, Jerusalem 1995

ibid. (Reviews) Biblica 77 (1996),

582–584. — JRA 9 (1996), 354–357. — BAR 23/1 (1997), 58–63. — Journal for the Study of Judaism 28

(1997), 105–110. — BAIAS 16 (1998), 85–95. — Bibliotheca Orientalis 55 (1998), 520–526. — Orientalistische Literaturzeitung 93 (1998), 47–52. — PEQ 130 (1998), 168–170. — Dead Sea Discoveries 6 (1999),

205–207

VI: Hebrew Fragments from Masada

The Ben Sira Scroll from Masada, by S. Talmon & Y. Yadin,

Jerusalem 1999

ibid. (Reviews) Dead Sea Discoveries 3 (1996), 329–332

9 (2002), 274–276. — JRA 9

(1996), 355–357. — Orientalistische Literaturzeitung 93 (1998), 47–51. — MdB 123 (1999), 73. — BAR

26/3 (2000), 60, 62. — BASOR 319 (2000), 81–82. — NEA 63 (2000), 114–115. — Orientalia 69 (2000),

186–188. — Revue de Qumran 21/(81) (2003), 125–128

VII: The Pottery of Masada, by R. Bar-Nathan,

Jerusalem 2006

N. Ben-Yehuda, The Masada Myth: Memory and Mythmaking in Israel, Madison, WI 1995;

ibid. (Review) SCI 17 (1998), 252–255

id., Sacrificing Truth: Archaeology and the Myth of Masada, New

York 2002

ibid. (Review) Archaeology 56/2 (2003), 56

J. F. Hall & J. W. Welch, Masada and the World of

the New Testament (Brigham Young University Studies 36/3), Provo, UT 1996–1997

D. Gil et al., Shallow

Geophysical Surveys to Determine the Thickness of the Roman Assault Ramp at Masada (The Geological

Survey of Israel GSI/39/2000

Geophysical Institute of Israel Report 808/89/01), Jerusalem 2000

Masada:

Proposed World Heritage Site by the State of Israel, Jerusalem 2000

Y. Max, The Glass Vessels from Masada

from the End of the First Century BCE to the Early Second Century CE (Ph.D. diss.), Jerusalem (in prep.).

G. Foerster, MdB 79 (1992), 23–28, 29–31

id., BA 56 (1993), 143–144

id., Judaea and the GraecoRoman World in the Time of Herod in the Light of Archaeological Evidence, Göttingen 1996, 55–72

id.,

Michmanim 14 (2000), 16*–17*

K. G. Holum, BAR 18/5 (1992), 4–10 (Review)

J. Magness, BAR 18/4

(1992), 58–67

id., Revue de Qumran 16/63 (1994), 397–419

id., BA 59 (1996), 181

id., ASOR Newsletter

47/3 (1997), 10

id., The First Jewish Revolt, London 2002, 189–212

MdB 79 (1992), 2–32

E. Netzer, BAR

18/2 (1992), 18

id., MdB 79 (1992), 3–12

id., ESI 13 (1993), 111–112

id., Die Paläste der Hasmonäer

und Herodes’ des Grossen (Antike Welt Sonderhefte

Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie), Mainz am Rhein

1999

id., Roman Baths and Bathing, 1: Bathing and Society (JRA Suppl. Series 37), Portsmouth, RI 1999,

45–55

id., Wasser im Heiligen Land: Biblische Zeugnisse und Archäologische Forschungen (eds. W. Dierx

et al.), Mainz am Rhein 2001,195–204

id., The Aqueducts of Israel, Portsmouth, RI 2002, 353–364

id.,

One Land—Many Cultures, Jerusalem 2003, 277–285

id., IEJ 54 (2004), 218–229

id., The Architecture

of Herod, the Great Builder, Tübingen (forthcoming)

D. Gil, Nature 364 (1993), 569–570

id., BAR 27/4

(2001), 22–31

J. F. Healey, PEQ 125 (1993), 84 (Review)

J. Patrich, JRA 6 (1993), 473–475 (Review)

Y.

Sapir, JSRS 3 (1993), xvi–xvii

N. A. Silberman, A Prophet from Amongst You: The Life of Yigael Yadin,

Reading, MA 1993

id., Archaeology 47/6 (1994), 30–40

id., Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 3/1–2 (1999), 9–15

H. Eshel, JSRS 4 (1994), 110–113

I. Nielsen, Hellenistic Palaces: Tradition

and Renewal (Studies in Hellenistic Civilization 5), Aarhus 1994

M. Coogan, BAR 21/3 (1995), 46

M.

Gichon, Bulletin du Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherches Aériennes 18/2 (1995), 25–27

id., JSRS 5

(1995), xv–xvi

H. Granger-Taylor, Halı: The International Journal of Oriental Carpets and Textiles 17

(1995), 77

Z. Meshel, Cathedra 76 (1995), 198–199

id., EI 25 (1996), 105*

id., IEJ 47 (1997), 295–297;

id., BAR 24/6 (1998), 46–53, 68

id., JSRS 12 (2003), xi

13 (2004), ix

A. Ovadiah, 5th International Colloquium on Ancient Mosaics, Bath, England, 5–12.9.1987 (eds. P. Johnson et al.), Ann Arbor, MI 1995, 67–77;

J. Roth, SCI 14 (1995), 87–110

J. Yellin, Trends in Analytical Chemistry 14 (1995), 37–44

BAR 22/6 (1996),

27

25/1 (1999), 20

K. Fittschen, Judaea and the Graeco-Roman World in the Time of Herod in the Light of

Archaeological Evidence, Göttingen 1996, 139–162

H. Geva, EI 25 (1996), 100*

O. Guri-Rimon, Cathedra

82 (1996), 191

M. Hershkovitz, EI 25 (1996), 101*–102*

id., Judaea and the Graeco-Roman World in

the Time of Herod in the Light of Archaeological Evidence, Göttingen 1996, 171–176

O. Lernau & H. M.

Cotton, Ichthyoarchaeology: Fish and the Archaeological Record (Archaeofauna 5), Madrid 1996, 35–41;

N. Mendecki, Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny 49 (1996), 164–170

P. Richardson, Herod: King of the Jews and

Friend of the Romans (Studies on Personalities of the New Testamenet), Columbia, SC 1996

id., Building

Jewish in the Roman East (Suppls. to the Journal for the Study of Judaism 92), Waco, TX 2004, 253–269;

Sacred Realm: The Emergence of the Synagogue in the Ancient World (Yeshiva University Museum

ed. S.

Fine), New York 1996, 21–27

H. Watzman, Archaeology 49/6 (1996), 27

50 (1997), 19

G. W. Friend &

S. Fine, OEANE, 3, New York 1997, 428–430

A. Grossberg, JSRS 7 (1997), xi

id., Cathedra 85 (1997),

189–190

A. S. Issar & D. Yakir, BA 60 (1997), 101–106

Le opere fortificate de Erode il Grand, Firenze

1997

S. Rozenberg, Roman Wall Painting: Materials, Techniques, Analysis and Conservation. Proceedings of the International Workshop, Fribourg 7–9.3.1996 (eds. H. Béarat et al.), Fribourg 1997, 63–74

H.

Shanks, BAR 23/1 (1997), 58–64

B. G. Wright III, The Archaeology of Israel, Sheffield 1997, 196–199;

N. Ben-Yehuda, BAR 24/6 (1998), 30–39

D. M. Jacobson, BAIAS 16 (1998), 85–95

17 (1999), 67–76;

id., PEQ 134 (2002), 84–91

M. J. Ponting, Archaeometry 40 (1998), 109–122 (with I. Segal)

44 (2002),

555–571

id., Archaeological Sciences 1999: Proceedings of the Archaeological Sciences Conference, University of Bristol 1999 (BAR/IS 1111

ed. K. A. Robson Brown), Oxford 2003, 111–116

N. Porat & S. Ilani,

Israel Journal of Earth Sciences 47 (1998), 75–85

D. W. Roller, The Building Program of Herod the Great,

Berkeley, CA 1998

A. Speransky-Marshak & B. Yuzefovsky, IEJ 48 (1998), 190–193

D. Stacey, PEQ 130

(1998), 83 (Review)

J. Zias, BAR 24/6 (1998), 40–45, 64–66

id., The Dead Sea Scrolls, 50 Years After Their

Discovery: Major Issues and New Approaches. An International Congress, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem,

20–25.7.1997 (eds. L. H. Schiffman et al.), Jerusalem 2000, 732–738

P. Dec, Ruch Biblijny I Liturgiczny

52 (1999), 251–258

R. Hachlili, EI 26 (1999), 229*

I. Kempel, MdB 118 (1999), 72

A. Lichtenberger, Die

Baupolitik Herodes des Grossen (Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 26), Wiesbaden 1999

J.

R. Rea, SCI 18 (1999), 121–124

C. Woofitt, Conservation News 69 (1999), 41–42

Archaeology International 3 (1999–2000), 7

M. Bietak & K. Kopetzky, Synchronisation, Wien 2000, 116

G. Davies, Anatolian

Studies 50 (2000), 151–158

W. Klassen, Text and Artifact in the Religions of Mediterranean Antiquity (P.

Richardson Fest.

Studies in Christianity and Judaism 9), Waterloo, Canada 2000, 456–473

J. Sudilovsky,

BAR 26/6 (2000), 47

P. Donceel-Voute, La mosaïque gréco-romaine 8: Actes du 8. Colloque International

pour l’Étude de la Mosaïque Antique et Médiévale, Lausanne, 6–11.10.1997 (Cahiers d’archéologie romande

86

eds. D. Paunier & C. Schmidt), 2, Lausanne 2001, 490–509

Y. Hirschfeld, BAIAS 19–20 (2001–2002),

119–156

id., SCI 23 (2004), 69–80

R. Reich, ZDPV 117 (2001), 149–163

119 (2003), 140–158

E. M.

Smallwood, The Jews Under Roman Rule from Pompey to Diocletian: A Study in Political Relations, Boston

2001 (index)

H. Goldfus & B. Arubas, Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Roman Frontier

Studies, Amman, Jordan, 2–11.9.2000 (BAR/IS 1084

eds. P. Freeman et al.), Oxford 2002, 207–214

D.

H. Levy, Mercury 31/2 (2002), 24–29

B. Leyerle, What Athens Has to Do with Jerusalem, Leuven 2002,

349–372

L. B. Kavlie, NEAS Bulletin 49 (2004), 5–14

M. Reddé, Archäologischer Anzeiger 2004/2, 54–56;

L. I. Levine, The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years, 2nd ed., New Haven, CT 2005, 61–63

A.

Lewin, The Archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine, Los Angeles, CA 2005, 126–137

D. R. Schwartz,

SCI 24 (2005), 75–83

G. D. Stiebel, Carnuntum Jahrbuch 2005, 99–108.

H. Gitler, LA 46 (1996), 317–362

The Qumran Chronicle 7 (1997), 65–89

R. Reich, ZDPV 117 (2001),

149–163.

S. Talmon, EI 24 (1993), 235*

id., Minha le-Nahum: Biblical and Other Studies (N. M. Sarna Fest.

JSOT

Suppl. Series 154

eds. M. Brettler & M. Fishbane), Sheffield 1993, 318–327

id., Dead Sea Discoveries 3

(1996), 168–177, 296–314

id., IEJ 46 (1996), 248–256

47 (1997), 220–232

id., Journal of Jewish Studies 47 (1996), 128–139

id., Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 27 (1996), 29–49

id., Boundaries of the

Ancient Near Eastern World (C. H. Gordon Fest.

JSOT Suppl Series 273

eds. M. Lubetzky et al.), Sheffield 1998, 150–161

H. M. Cotton (& J. Geiger), IEJ 45 (1995), 52–54, 274–278

id. (& Y. Goren), JRA 9

(1996), 223–238

id. (& J. Geiger), Judaea and the Graeco-Roman World in the Time of Herod in the Light

of Archaeological Evidence, Göttingen 1996, 163–170

id., ZDPV 115 (1999), 228–247

N. Lewis, IEJ 46

(1996), 256–258

P. Zdun, Piesni Ofiary Szabatowej z Qumran i Masady, Krakow 1996

ibid. (Reviews),

Dead Sea Discoveries 6 (1999), 236–237

P. C. Beentjes, The Book of Ben Sira in Modern Research:

Proceedings of the 1st International Ben Sira Conference, July 1996, Sösterberg, Netherlands (ed. P. C.

Beentjes), Berlin 1997, 95–111

C. Martone, ibid., 81–94

P. Arzt, Archiv für Papyrusforschung 44 (1998),

228–239

E. Tov, Biblical Perspectives: Early Use and Interpretation of the Bible in Light of the Dead Sea

Scrolls: Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium of the Orion Center for the Study of the Dead Sea

Scrolls and Associated Literature, 12–14.5.1996 (Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah 28

eds. M. E.

Stone & E. G. Chazon), Leiden 1998, 233–256

id., Dead Sea Discoveries 7 (2000), 57–73

G. W. Nebe,

ZAW 111 (1999), 622–626

É. Puech, Treasures of Wisdom: Studies in Ben Sira and the Book of Wisdom (M.

Gilbert Fest.

Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 143

eds. N. Calduch-Benages & J.

Vermeylen), Leuven 1999, 411–426

R. Hachlili, These are the Names: Studies in Jewish Onomastics (eds.

A. Demsky et al.), Ramat Gan 2002, 93–108

I. M. Young, Dead Sea Discoveries 9 (2002), 364–390

E.

Eshel, Dead Sea Discoveries 10 (2003), 359–364

E. Ulrich, Emanuel: Studies in Hebrew Bible, Septuagint

and Dead Sea Scrolls (E. Tov Fest.

VT Suppl. 94

eds. S. M. Paul et al.), Leiden 2003, 453–464

E. Netzer,

IEJ 54 (2004), 218–229.

J. Cobet, Babylon: Beiträge zur Jüdischen Gegenwart 10–11 (1992), 82–109

P. Cordente Vaquero, Gerion

10 (1992), 155–170

M. B. Schwartz & K. J. Kaplan, Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 25 (1992),

127–132

K. J. Kaplan & M. B. Schwartz, Journal of Psychology and Judaism 18 (1994), 205–218

R.

Paine, History and Anthropology 6 (1994), 371–409

C. P. Jones, Historia (Stuttgart) 46 (1997), 249–253;

M. Azaryahu & A. Kellerman, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 24 (1999), 109–123

H.

Eshel, Gemeinde ohne Tempel: aur Substituierung und Transformation des Jerusalemer Tempels und seines

Kults im Alten Testament, antiken Judentum und frühen Christentum (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen

zum Neuen Testament 118

eds. B. Ego et al.), Tübingen 1999, 229–238.

- Jodi Magness, Masada: From Jewish Revolt to Modern Myth, Princeton University Press (May 14, 2019)

- Avi-Yonah, Michael et al., Israel Exploration Journal 7, 1957, 1–160 (excavation report Masada)

- Yadin, Yigael. Masada: Herod’s Fortress and the Zealots' Last Stand. London, 1966.

- Yadin, Yigael. Israel Exploration Journal 15, 1965 (excavation report Masada).

- Netzer, Ehud. The Palaces of the Hasmoneans and Herod the Great. Jerusalem: Yed Ben-Zvi Press and The Israel Exploration Society, 2001.

- Netzer, E., Masada; The Yigael Yadin Excavations 1963–1965. Vol III. IES Jerusalem, 1991.

- Ben-Yehuda, Nachman. The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking In Israel, University of Wisconsin Press (December 8, 1995).

- Ben-Yehuda, Nachman. Sacrificing Truth: Archaeology and the Myth of Masada, Humanity Books, 2002.

- Bar-Nathan, R., Masada; The Yigael Yadin Excavations 1963–1965, Vol VII. IES Jerusalem, 2006.

- Jacobson, David, "The Northern Palace at Masada – Herod's Ship of the Desert?" Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 138,2 (2006), 99–117.

- Roller, Duane W. The Building Program of Herod the Great, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998.