Fig. 1. Location map of the earthquake of 14 January 1546. Solid circles show sites where the shock was

reported felt or caused damage. Large open circles indicnte other localities mentioned in the text.

Small open circles show some other places where reported damage my not be associated with the

1546 earthquake. Shading shows estimated extent of epicentral region. Arrows show extent of coast

affected by the associated seismic sea-wave.

Ambraseys and Karcz (1992)

The earthquake of 1546 in the Holy Land is considered to be one of the most important shocks known to have occurred in the Middle East to which modern writers assign a magnitude ML 7.0 and an epicentral intensity of X-XI (Ben Menahem 1979). However, the available evidence suggests that this was not a major earthquake and it must be classed as one of those which excite widespread interest rather on account of the geographical location than because of their special violence.

This event is presented in some detail not only because it is imperfectly known and its effects are usually grossly exaggerated, but also because it occurred in what appears today to be a seismically quiescent region of a densely populated and fast-developing part of the Middle East.

Early catalogues ignore the 1546 earthquake. Bonito (1691) gives, without details, an earthquake in Judaea in 1541, and the event is mentioned briefly by Hoff (1840) on the authority of Bernherz (1616), whose primary source is Rivander Bachmann (1607), itself a secondary source. Perrey (1850) follows Hoff (1840) and Mallet (1852) quotes Rivander Bachmann. Schmidt (1879) notes the earthquake briefly and quotes Anonymous of Wittenberg (1546), a primary source. Arvanitakis (1903b), on the authority of Dositheos (1715), dates the event to 1543, and Willis (1928) copies the earthquakes of 1534 and 1546 from Arvanitakis (1903b) and Perrey (1849), respectively, thus duplicating the event. Sieberg (1932a; 1932b) and later authors, with the exception of Braslayski (1938), who should be given credit for using a number of original sources, add nothing but confusion. Finally, Ben Menahem (1979) and Rotstein (1987), who do not give their sources of primary information, regard this event, with little justification, as one of the most destructive in the Jordan rift zone.

The information on the effects of the earthquake of 1546 retrieved so far comes from both occidental and oriental sources. Among these is the account of an anonymous Venetian, who was probably an eye-witness. Other contemporary or near-contemporary sources include the continuator of Mujir al-Din’s history, as well as Hebrew, Greek and Turkish material and the accounts left by travellers. The event may be reconstructed using these accounts as the foundation. Other late -sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sources that preserve information on the 1546 earthquake that are considered as original are also taken into account. The earthquake of 1546 occurred only 30 years after the Ottoman conquest of Syria and Egypt (1516–17), as a result of which Palestine became a province of the Ottoman Empire. This undoubtedly had an effect on the production of local dynastic chronicles in Arabic, both in Egypt and in Syria. The sources of local information for this period are, therefore, chiefly in Hebrew and Turkish, mainly private and state correspondence, as well as archival material from local Sharia courts and, to a lesser extent, the accounts left by travellers. The correspondence from Cyprus and Constantinople in the archives of Venice containing news from Palestine was also examined, as were Greek church sources originating from Jerusalem.

The earliest information about the 1546 earthquake comes from a letter written to a nobleman in Venice and published the same year in Wittenberg. The original letter was written in Italian, probably originating from a town on the coast of Palestine. It says that

About noon, on the 14th of January AD 1546 there was a terrific earthquake in Jerusalem. As a result the vault of the Holy Tomb sunk and the walls and tower of the Temple were damaged and parts of them collapsed. The same happened in Damascus and great damage was done to other towns and villages; many people perished at sea and on land. Four towns in particular, Rama, Joppe, ‘Zozilgip and Sichem were totally destroyed by this earthquake to the extent that, with the exception of Damascus and Joppe, one can no longer recognise that there had been towns on these sites. And there exist no other places in these regions that would not have been damaged. On the same day, blood was flowing out from a fountain, named after the Prophet Eliseo, from which always water was drawn off. And at the beginning of this, flames coming out from the fountain were seen, and this lasted for four days. On the day of the earthquake the river Jordan dried up for two days and so did all the streams around Joppe that fall into the sea, which stopped flowing for three days. And when they began to flow again, the water was red. The sea near Joppe retreated to a distance of a full days’ walk off shore (sic.), so that one could walk with dry feet on the sea bed. A great many people, about 10 000, who ventured on foot offshore were drowned when the sea came back. At the same time, unusually strong winds got up so that near Tripoli they brought up a lot of sand and clay from the south that drifted into mounts. At the same time, equally strong winds caused great damage to the city of Famagusta in Cyprus and ruined its vineyards, something that also happened at San Sergio’ (Anon. 1546).

Figure 3.20 News from Wittemberg about the earthquake of 14

January 1546 in Palestine and strong winds that caused great

damage to the city of Famagusta in Cyprus. JW: Original Image from Ambraseys (2009) has been replaced

with an image from an online digital copy of the manuscript.

However, confirmation of this identification must await the retrieval of the original Italian version of the Venetian letter. The French version does not mention Zozilgip at all, and differs in some details from the German version. It attributes to a tempest the collapse of part of the walls of the Sepulchre in Jerusalem, of one third of the temple of Solomon, i.e. one of the mosques on Temple Mount, and of all the bell towers in Judea; in addition it implies that the coast was flooded by the sea all the way from Gaza to Jaffa (Techener 1861). The number of people drowned by the seismic sea wave is, obviously, grossly exaggerated.

More striking differences in location and on the date of damage have led to a controversy over the provenance of a sixteenth-century Spanish manuscript that describes the same event. This document, annotated as News of ‘46’, and obviously a contemporary copy from an unknown original, is indeed very similar in content to the Wittenberg version. However, it places the earthquake on 8 January 1546, does not mention Zozilgip and Sichem, and reports instead the destruction of Cifayde and Cigle. It also says that the whole province of Damascus was affected but that the city itself, and yet another city, did not suffer any damage. Beinert (1955 and personal communication 1991), who has read the manuscript, believes that these differences, as well as the phrasing, indicate that this is a first-hand account of the earthquake, experienced by a Spanish monk or pilgrim. He suggests that Cifayde stands for Safed in Galilee, a town not mentioned in the other versions. On the other hand, Braslavski (1956) and Shalem (1955) assume that this document is no more than a somewhat careless translation of the German or French versions, with errors in copying the transliteration of geographical names; Shalem argues that Cigle stands for Sichem, i.e. Nablus in Samaria, and Braslavski identifies Cifayde as Jaffa. An obviously independent contemporary account of the earthquake is found in the anonymous continuator of the chronicle by Mujir al-Din, in Mayer (1931). Though this sequel (dhail) covers events that took place between 1497 and 1509, that is before Mujir al-Din’s death in a.H. 927 (1521), it begins with the description of three earthquakes that followed one another during the period a.H. 952–953 (AD 1546). The part of this chronicle that refers to this sequence says that

On Thursday afternoon, 10th of Dhu’l-Qa’da 952, there occurred a great earthquake in Jerusalem, al-Khalil [Hebron], Gaza, al-Ramlah, alKarak, as-Salt, and Nablus which extended to Damascus. It lasted a short while and calmed down, and generally there was not a tall house in Jerusalem that was not left destroyed or fissured, and the same in al-Khalil [Hebron]. In Gaza the madrasa of Qayitbey was destroyed as well as the south part of his madrasa in Jerusalem, and its north and east sides; also, the top of the minaret over the Bab as-Silsila was destroyed. In Nablus the earthquake was stronger than elsewhere, and 500 lives were lost under the ruins.Although many of the details in the sequel to Mujir al-Din’s chronicle resemble those in the Venetian letter, which refers quite clearly to the 1546 earthquake, their inclusion at the beginning of a historical account that describes events that belong to the period 902–914 (AD 1497–1509) raised some doubt regarding the actual year of these events. Mayer recognised that this complication might be due to a mere slip of the pen of a scribe, who, whilst turning marginal notes into the sequel of Mujir al-Din’s chronicle, copied later events first and a series of earlier events, running consecutively, later (Mayer 1931).

Then, on Sunday night, 10th of Muharram, 953 [= 13 March 1546] there was another alarm, the noise of which was greater before it died out.

Then, on Wednesday afternoon, 12th Rabi’ I of the year 953 [= 13 May 1546], there occurred another shock felt by some people more than others, apart from the continuous shocks of previous days, some of which occurred at night and some during the day . . .

However, Mayer was more inclined to think that what he had in his hands was a faithful copy of the dhail as written by Mujir al-Din himself, and that the events described are in the right chronological order, that is, that there was an error in the years, which should read 902 and 903 rather than 952 and 953. However, another reason why Mayer was more inclined to think that there was an error in the years of these events was that he could find no evidence for an earthquake in either Syria or Palestine in the year a.H. 952 (1546). Obviously, he was not aware of the Venetian letter and of the other sources which we have retrieved that now remove any ambiguity about the actual date of the event. The incorrect year given by Mayer was thus propagated in later catalogues. Reading the years of the earthquake sequence in Mujir’s dhail as a.H. 952 and 953, the date of the main shock, Thursday 10 Dhu’l Qa’da 952, corresponds to 13 January 1546, which was a Wednesday. A discrepancy of one day is common in converting the Muslim calendar. For instance, a sigil in the Khaladiyye Library in Jerusalem (1856, vol. 17, 437), dated 21 Dhu’l-Qa’da a.H. 952, says briefly

the day before today, Thursday the 10th of the month, after the noon prayer, a disaster came from the sky and a great earthquake occurred in the name of God.For the date of the second shock Mayer considers Mujir al-Din’s date to be the ‘night of 11 Muharram’, which would have been Sunday 14 March, although the Arabic text says ‘Sunday night 10 Muharram’ 953, which corresponds to Saturday 13 March 1546. This is correct since Sunday night in the Muslim calendar means the night starting on Saturday, since the Muslim day starts at sunset and day follows night. However, the Khaladiyye manuscript of the dhail gives 13 Dhu’l-Qa’da, that is, three days after the main shock. For the third shock in Mujir’s sequel, Wednesday afternoon 12 Rabi I 953 corresponds to 13 May, which was a Thursday. There can thus be little doubt that the details in Mujir’s chronicle refer to the earthquake sequence of 1546, and that the dhail must have been added by a later scribe or by a copyist. Indeed, Mayer himself says that in the copy of the dhail kept in the Khaladiyye Library, which has not been viewed, the earthquakes are described in an additional note on the last page.

Contemporary Hebrew documents provide an additional, independent source of information about the earthquake. A Hebrew manuscript notice written by Sussman ben Rabbi Abraham Carit, who arrived in Jerusalem in 1545 two months before the earthquake, states that

in the month of Shvat the Almighty has shown us signs and wonders that none of our forefathers ever witnessed, and on the 11th of that month, on Thursday, about one in the afternoon . . . [because] of the quake many towers fell down, almost the third of their height, and the tower of “A. A.” was one of them. About ten gentiles were killed in Jerusalem but none of the Jews, and in the town of Nablus the earthquake was so strong that at least three hundred gentiles, and three or four Jews were killed. There were also further shocks after that, but not so strong, and to this day we are in constant fear of an earthquake all day and night (Braslavski 1938).The 11th of Shvat corresponds to 14 January 1546, which was a Thursday. Klein (1939) suggests that ‘A. A.’ stands for ‘Avraham Avinu’, i.e. our Father Abraham, and refers to the tower over Abraham’s Tomb in Hebron. This locality is mentioned in Mujir al-Din’s sequel as al-Khalil, the Arabic name used for Hebron because of Abraham’s sanctuary, the Friend of Allah. The disagreement as to when the copy of this document was made and by whom (Braslavski 1938; Turnianski 1984) does not detract from the authenticity of its contents. Sussman died about 20 years after the earthquake, and the phrasing suggests that he wrote the note shortly after the event.

A more detailed description of the effects of the earthquake, about 18 lines long, is found in a copy of another Hebrew document, appended to a booklet called Ot nafshi, in 1625, or in 1562, according to Klein (1939), belonging to one Isaac Levy, and apparently copied by him from an unknown source. According to this document,

On Thursday 11th, of the month Shevat, year Hashav [14 January 1541], at one in the afternoon, there was a great earthquake and there was almost total destruction of Jerusalem, there is no house that was not destroyed or cracked, and even from the new city wall there fell a scythe in height, such as at the Gate of Mercy. And also fell the Ishmaelite mosques as well as the cupola of alAqsa, and so did the Holy Sepulchre, a building full of windows, that some say was built by Nabuchadnezar king of Babylon and even the Ishmaelites are wondering since it was a very strong building. And the gentiles say that there never was such an earthquake in Jerusalem . . . and in contrast, praise be to God, our synagogue was left undamaged. About 12 Ishmaelites perished, and none of the Jews. But in Nablus about 560 Ishmaelites perished of the townfolk, but nobody knows of the villagers, since they still may be buried under the rubble; three Jews died in Nablus. And in Hebron, 16 Ishmaelites perished and 70 were injured with broken arms and legs. And the gentiles report that the river Jordan is dry and they crossed it on dry land and that this lasted three days. Worse than the fall of their houses, they lamented their [loss of] water, . . . which turned into blood for three or four days. And . . . the Jordan was dry and desolate because two big hills fell into the river, and others say that the earth cracked and swallowed up the waters of the Jordan. It is also said that the gentiles in Jerusalem offered monies to the Ishmaelites to allow them to rebuild a church, but to no avail, and what fell, remained fallen. There is no house in Jerusalem that did not crack in the earthquake, and also, many mosques have collapsed . . . (Braslavski 1939).The words

but nobody knows how many of the villagers [perished] since they still may be buriedsuggest that this document was written immediately after the event. However, the penultimate sentence, regarding the refusal of the Ottoman authorities to approve the reconstruction of churches, implies that this document was not composed so soon after the earthquake. Internal evidence suggests that this notice was written sometime after the event.

A contemporary Hebrew ode, ‘piut’, composed by a certain Moshe Meali, and found in the Cairo Geniza by Razabi (1982), describes a plague, earthquake, famine and locust infestation that befell Jerusalem. The earthquake, it says, caused houses and shops to collapse. Two synagogues fell apart and so did two churches that adjoined each other. Severe damage was caused to the Holy Sepulchre and to the Dome of the Rock. The people left their houses and stayed in the city cemeteries.

This poem, which was composed some time after these calamities, extends their occurrence over several years, starting with AD 1542/3 (‘hashab’). The earthquake is placed in the midst of a Passover feast of the following year, that is, sometime in the spring of 1543 or 1544. It would appear that the poet, who was writing some time after these events, erred in the year, and that the association of the earthquake with the Passover is purely decorative.

Additional information about the effects of the earthquake can be gleaned from the narrative of European travellers who happened to be in the Holy Land shortly after the 1546 earthquake. Anonymous of Douai (1714), most probably a Franciscan friar, left France in October 1545. The copy of his narrative made in 1714 is incomplete and starts in the middle of a phrase describing the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, concerning which he does not mention any earthquake damage. From Jerusalem he proceeds to Bethlehem, then Ramla, and he is in Jaffa on 7 June 1546, from where he sails off to Cyprus and Venice, where he arrives on 29 August. Therefore, he should have arrived in the Holy Land a few months after the earthquake and probably would have experienced the aftershock of 13 May 1546. However, nowhere in the extant part of his narrative is there any explicit mention of the effects of the 1546 earthquake. His truncated account contains nothing about the effects of the earthquake in Jerusalem. He travels to the Jordan river and the Dead Sea, and it is after leaving the monastery of St Joachim that he describes (fol. 14r) a site called ‘Donny’, previously a natural arch cut through rock forming a bridge, which had been destroyed by earthquakes. From there he proceeds to the site of the ‘trois montagnes’, which were dangerous on account of the rocks that earthquakes cause to roll down from the summit, and arrives in Jericho, which he finds in ruins.

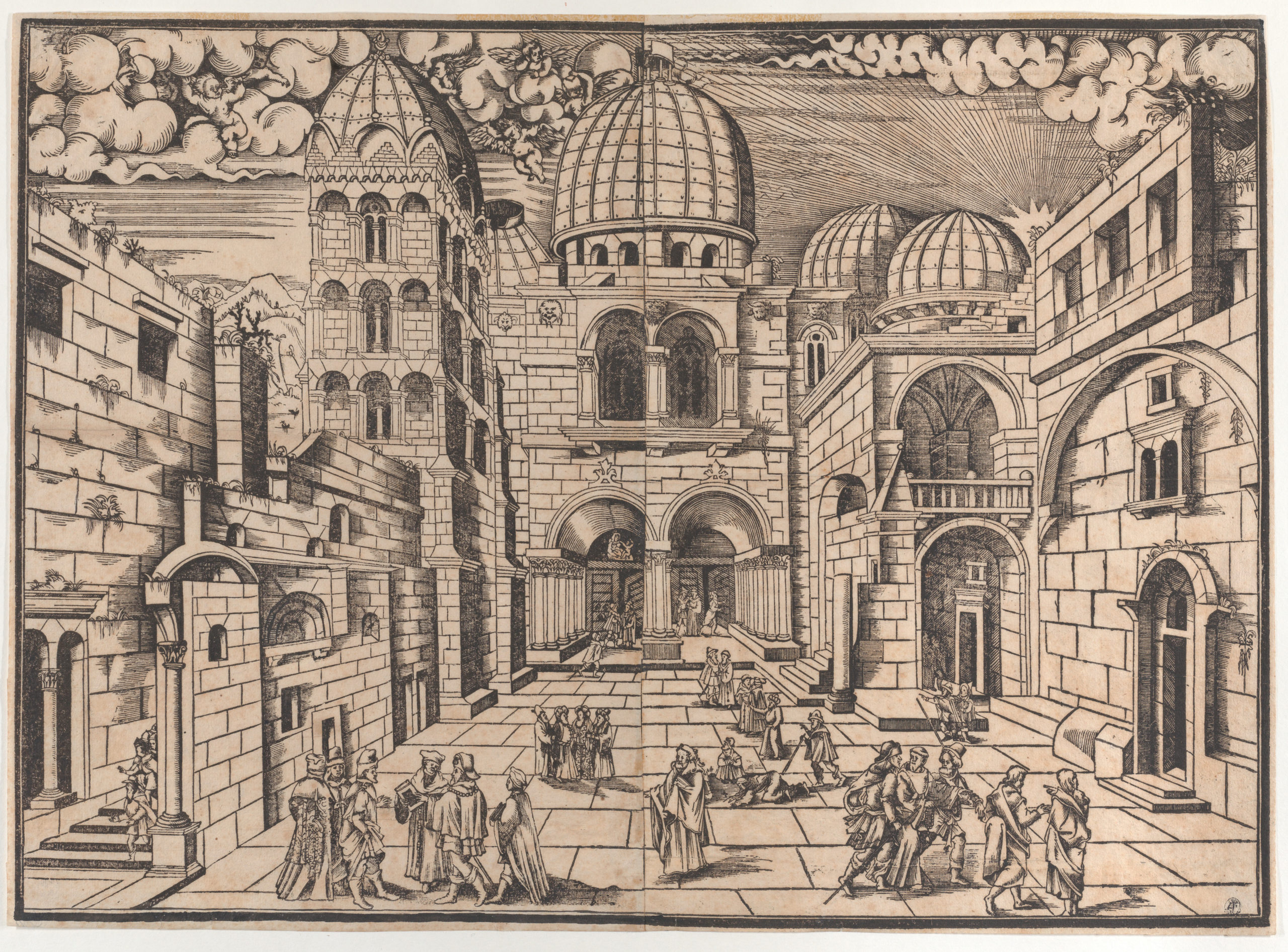

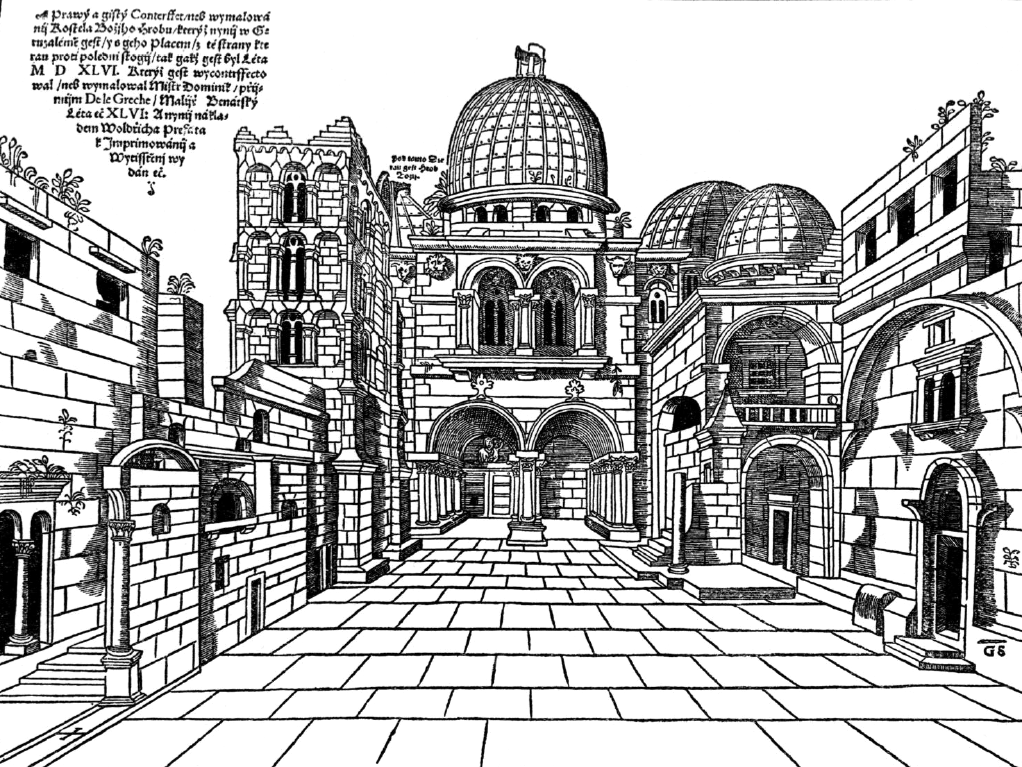

Figure 3.21 Voldrich's Jerusalem, drawn by Dominik de la Greche in the summer of 1546, seen from the east. It shows the bell

tower of the Holy Sepulchre with its top part missing, with no other recognisable destruction caused by the 1546 earthquake

(Vit Karnik). Red arrow (added by Williams) points to the broken bell tower of the Holy Sepulchre

(left) A drawing by de la Greche apparently of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre before the earthquake when the Bell Tower to the left was still intact - from The Met - NYC (right) Figure 3.22 from Ambraseys (2009) - A view of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and its square seen from the south side, drawn by Dominik de la Greche a few months after the earthquake of 1546. Notice the missing top part of the bell tower (Vit Karnik).

On the left side of the square, as you face the door of the church, on the eastern side, there is a tall square tower attached to the church built of hewn stone, with many windows. As we were told, the upper part of the tower collapsed during a strong earthquake that took place in Jerusalem just before the feast of the Three Kings [Epiphany: 14 January]. The truss was all vaulted up to the top and it was covered with sheets of lead. However, it all collapsed together with a good piece of the tower and still lies in ruins; nobody is repairing it.In his detailed description of the Holy Sepulchre and of its interior, Voldrich does not mention any other earthquake damage. He appends a view of the church, drawn by Dominik de la Greche shortly after the earthquake (see Figures 3.21–3.24) with the following caption:

This is the correct and true picture of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, with its square, seen from the south side, as it was in the year 1546, drawn by Master Dominik de le Greche, Venetian painter, in the year 46, and now printed under the care of Woldrich Prefat.He also mentions the damage caused by the earthquake in Bethlehem. After describing the basilica, he says that

in the same premises there used to be another vaulted and relatively large church, but the earthquake, we were told, destroyed it, so that its vault and base collapsed completely. There are still a few pillars, pieces of the vault and walls still to be seen, covered with debris. This was the church of St Jeronymus. Several other adjoining buildings, cells, a part of the refectory and the cloister were also badly damagedHe continues with the description of the monastery and of other buildings in Bethlehem that survived the earthquake without damage.

He notices other ruined buildings for which, however, he does not give the cause of their destruction. In Ramla he notices several small chapels badly damaged and says that parts of the town walls were always ruined. On the way from Ramla to Jaffa he saw a church with the upper part of its belfry destroyed. Near Ramla he found the remains of a monastery that had also been destroyed. On the road from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, on a hill, there was a tower, the upper part of which was heavily damaged. Near Bethlehem he saw a chapel that had collapsed completely; however, a church in a nearby field was not damaged. Between Bethlehem and Bet Jala he found another church that had collapsed, but its tower was still standing. Near Battir, a small half-ruined town, he found a chapel near a cave that had collapsed. On his return from Bethlehem, near the place where John the Baptist was born, he saw a church that was partly ruined, as well as another church and a monastery nearby that had suffered considerable damage. Also a square tower and a few houses in Bethany were heavily damaged. On the Olivet Mount he found the remains of a church and a monastery, with some walls still standing. Jericho was in ruins and the church, allegedly built by St Helen, damaged. On the way from the Dead Sea to Jericho, on a hill on the left-hand side of the road, he saw another church, which he says was that of St John the Baptist, which was damaged. On travelling from Bethlehem to Hebron he noticed another small church, a part of which had collapsed. Hebron and Jaffa, he says, were in ruins, but this he attributes to the Egyptians and to the recent wars.

Figure 3.23 A view of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and its square in the early part of the nineteenth century. JW:

Ambraseys (2009) original image was replaced for a clearer image of the same artwork. Info about the drawing is available

here.

Figure 3.24 Pre-existing cracks in the masonry of the wall of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre enlarged by the earthquake of 11 February 2004 in the northeast of the Dead Sea (Ms 5.0) (A. Salamon) - from Ambraseys (2009) with photos replaced with originals courtesy of A. Salamon

as a result of the earthquake in the time of Germanos, the cupola of the copper tower of the belfry of the Holy Sepulchre fell on the nearby church of the Resurrection and caused the collapse of its dome that remains in ruins to the present day. The same earthquake destroyed the bell-tower of the Saint Bethlehem, its ruins left as seen today . . . these were the only two belfries left standing by the Arabs that fell in this earthquake.The date of the event is not mentioned, but the description of the damage sustained by the church of the Resurrection bears a strong resemblance to that given for the damage of the two churches adjoined to each other as given in the Hebrew ‘piut’.

A very similar description is found in Papadopulos-Kerameus (1898), who cites an anonymous Greek document, written in Jerusalem in the early nineteenth century and deriving from earlier sources. It says that

in the year 1545 (sic.) 14 January there was a frightful earthquake in the Holy City and throughout Palestine which caused the top of the beautiful bell-tower of the church situated between those of Adelphotheou and of St Tessarakonta to fall and destroy the dome of the church; also in Bethlehem the earthquake destroyed the bell-tower, the only one left standing by the Agarini [i.e. the Arabs] (Papadopoulos-Kerameus 1898, iv. 40)The churches of Adelphotheou or Adelphopoeitou and of St Tessarakonta were chapels in the compound of the Holy Sepulchre next to the bell tower.

These accounts seem to be the source of information about the damage to the mediaeval bell towers of the Holy Sepulchre and to the basilica in Bethlehem mentioned by Vincent and Abel (1922) and Harvey and Harvey (1938), who wrongly date the event to 1545.

Evidence for the repair of the damage caused by the earthquake to various buildings can be found in Ottoman archival sources. Some of those that have been retrieved refer to repairs of public buildings, chiefly Christian places of worship in Jerusalem. Although at first the attitude of the local authorities was negative, some repairs were eventually allowed, and gradually more substantial construction work was permitted.

Thus, following a petition dated June 1548 made by the Franciscans of Mt Zion in Jerusalem, permission was granted first to restore several rooms and the damaged northern and eastern halls, and four months later to repair six small rooms in the southern part of the monastery (Cohen 1982).

The archives of the Custodia Terra Sancta in Jerusalem contain numerous contemporary Ottoman documents granting permission for the repair or strengthening of churches and convent property across the land (Castellani 1922; Hussein et al. 1986). However, it is not possible to say whether the damage that required repair was due to the 1546 earthquake or to the war and natural ageing of these structures. These documents refer, for example, to repairs of the walls of the convent in al-Ramla, of the Church in Nazareth, on Mount Zion, restoration of the cupolas and chapels of the Holy Sepulchre, and repairs of the terraces and cupola of the church in Bethlehem. The decision to abandon a convent in Nazareth in 1548 (Cirelli 1918) may have also been the result of the 1546 earthquake.

The repair of buildings damaged by the earthquake apparently continued for almost a decade. An order detailing repair work, issued in Istanbul and addressed to the finance officer (defterdar) of Arabistan, dated 17 Rabi II 959 (12 April 1552), says

the tombs of Abraham the Friend (al-Khalil), Isaac and Jacob [at Hebron] are situated in a mosque which has fallen down in part and has become a ruin. Also the mosque that houses the tomb of the Prophet Moses (Nabi Musa) is in need of repair. And some parts of the wall which is situated on the east side of the Dome of the Rock have been destroyed by earthquakes so that a man can pass through; twice the mosque’s lead has been stolen . . . The repair of all these buildings is necessary and urgent (Heyd 1960).Since this order was issued almost six years after the earthquake, it may be only a supposition that it refers to damage caused by the 1546 earthquake rather than, perhaps, by later shocks. However, this is unlikely, since delays in the Porte’s response to requests for repairs of this nature were long. Moreover, this order refers to the repair of structures that are known from other sources to have been damaged by the 1546 earthquake and no other shocks during the period 1547–52 have as yet been identified.

Archaeological evidence and contemporary documents presented by Burgoyne (1987) also give further indication of the damage to some of the Muslim buildings in Jerusalem, such as the Ribat of ‘Ala’al-Din and Qayitbey’s madrasa (the Ashrafiyya). There is also evidence of damage to the Aminiyya madrasa and the minaret of the Fakhriyya.

The area strongly affected by the 1546 earthquake was, therefore, confined within an area demarcated by Nablus, Ar-Ramla and some point north of Jerusalem, Nablus suffering more than the other sites, Figure 3.21. However, it is rather surprising that despite the alleged heavy damage caused in Nablus – the main centre of the Samaritan community – no reference to this or to any other sixteenth-century earthquake has been found, so far, in the Samaritan chronicles and in the collections of the AB Institute for Samaritan Studies.

Earthquake damage in Jaffa, except for the effects of the seismic sea wave, is difficult to assess because this and other coastal towns were, at that time, in ruins and almost totally deserted (Rauwolff 1738; Schurr 1990). Voldrich Prefat z Vlkanova says that Jaffa ‘used to be a clean town but now everything is in ruins and no house can be seen; there are only two towers, repaired to house the seat of the Turkish commander’ (Voldrich 1563).

Damage in Jerusalem, chiefly to tall structures, was widespread but repairable and undoubtedly not as serious as some of the contemporary exaggerated accounts suggest. The description of Jerusalem left by the pilgrims who visited the city shortly after the earthquake does not give the impression of a destructive earthquake. This impression is, to some extent, confirmed by the detailed view of Jerusalem, drawn by Dominik de la Greche a few months after the earthquake (Figure 3.23) which shows no signs of destruction except for the top of the bell tower of the Holy Sepulchre, which is missing (Voldrich 1563).

In Bethlehem, the only structures that are known to have been destroyed or damaged beyond repair were the bell tower of the basilica, the church of St Jeronymous and a few appended structures.

In Hebron the shock caused some damage, mainly to tall buildings, and some casualties, but again here there is no evidence of destruction.

In Gaza, apart from the madrasa of Qayitbay, there is no evidence of serious damage. As-Salt and alKarak must have experienced strong shaking, but also here there is no evidence that the earthquake caused great concern.

There is no indication that the earthquake caused any damage in Nazareth, except that alluded to by Cirelli (1918). Avisar (1973), without quoting his source of information, maintains that the walls of the town of Tiberias, which had been built in 1540, as well as many houses, collapsed in the earthquake of 1546. No historical or archaeological evidence could be found for this.

For Safed, except for the tenuous identification of Cifayde with Safed by Beinert (1955), no reports of damage are available. Safed, at that time, was a prosperous community and a centre of learning and literary activity, so it is unlikely that, had there been earthquake damage, it could have passed unrecorded. Rabbi Yehuda Hallewa, in a text published in Safed a year before the earthquake in 1545(?), does mention the occurrence of earthquake shocks, which apparently caused no damage (Idel 1984), but there are no accounts for the 1546 event. Thus, there is no primary evidence that the shock caused any damage or great concern in northern Israel. This is supported by Braslavski (1959), who does not include the 1546 earthquake in his detailed study of historical earthquakes in Galilee.

The shock was reported from Damascus and its district, a large urban centre, where apparently it caused some concern.

No evidence has been found that the shock was felt in Lebanon or Egypt, nor for that matter is there any indication that it was felt elsewhere.

Modern writers (Oberhummer 1902; Sieberg 1932a; 1932b; Christophides 1969) maintain that the 1546 earthquake was also felt in Cyprus, where it caused damage. Although there is no reason to suppose that the shock was not perceived in the island, contemporary correspondence from Cyprus and Istanbul in the State Archives of Venice does not mention the earthquake of 1546 (Archivio a and b). It is very likely that modern writers have confused the damage caused in Cyprus by strong winds in 1546 and by the earthquake of 10 September 1549, which probably originated on the Hellenic Arc, an event that modern writers erroneously dated to 1547 The discolouration of water and change in the yield of springs, as well as the temporary damming of the Jordan and of streams round Jaffa, most probably, as in other earthquakes in the region, resulted from slumping of the ground and landsliding triggered by the shock (Braslavski 1938). Since the Quaternary marls and fine clastics of the river banks are quite unstable, even a light shock during winter flooding would suffice to set off a landslide.

The seismic sea wave which flooded the coast between Gaza and Jaffa, allegedly causing additional loss of life, was possibly due to a subaqueous slide from the unstable continental margin of Palestine triggered by the shock. The whole of the coast is certainly prone to slumping because of the evaporites in the sedimentary section (Garfunkel et al. 1979). Seismic sea waves are more likely to occur due to the instability of the continental margin rather than as a consequence of the severity of shaking due to an earthquake.

Absolutely no evidence has been found to substantiate Ben Menahem’s assertion that the earthquake of 1546 was associated with surface faulting extending from Damye to the Dead Sea (Ben Menahem 1979).

The silence of travellers about widespread or serious damage caused by the 1546 earthquake in central Israel does bring out the element of exaggeration which is obvious in some of the contemporary accounts of the event. Although accounts left by travellers and pilgrims of that time are brief and of a stereotyped format, it is reasonable to expect that, had there been widespread destruction from a large-magnitude earthquake, some record of it should have been preserved. It is important, therefore, that, with the exception of Anonymous of Douai and Voldrich Prefat z Vlkanova, travellers and pilgrims who traversed the epicentral region or visited the affected area shortly after the earthquake do not mention earthquake damage. The ruins they notice they attribute to wars, or they do not explain their cause. Belon (1588), for instance, in November 1547, on his way from Bethlehem through Bira, Nablus and Nazareth to Damascus, did traverse the epicentral area, but he says nothing about the effects of the earthquake of the previous year. The same applies to Gorynski (1914) and Willart (1548), ´ who spent August of 1548 in this area, and to Chesneau (1887), who passed through the region in July 1549.

This confirms the impression that the damage caused by the earthquake could not have been widespread or great, and was probably quickly repaired; for, had there been serious and extensive damage due to a large-magnitude earthquake, it is unlikely that it could have escaped them, and they would have recorded it, as they did for other places on their travels. This and the fact that the main shock was not reported from epicentral distances greater than about 200 km suggest that the 1546 earthquake was an event in many respects similar to that of 1927 (Vered and Striem 1977), that is, an earthquake of medium magnitude, MS about 6.0, which would be consistent with the short sequence of relatively weak aftershocks reported from the epicentral region.

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.