Fig. 1a - Damage distribution in Ottoman Palestine and its close surroundings

caused by the 1837 earthquake (Ambraseys 1997, 2009) and classified by

the degree of severity (Zohar et al. 2013) - from Zohar (2017)

covered up to a great depth with the ruins of many others. Katz and Crouvi (2007) examined slope stability in Safed and concluded that landslides occurred during earthquakes in 1759 and 1837 CE. The earthquake was reported to have been felt from Antioch to Egypt and aftershocks continued for months. In the Galilee, some villages were reported to have been destroyed while nearby ones were barely affected suggesting site effects were at play. Ambraseys (1997) estimated a Magnitude (MS) of 7.0-7.1 and suggested that it may have been a multiple event. Ambraseys (2009) suggested it was a shallow event that may have broken along or in the vicinity of the Roum Fault. Nemer and Meghraoui (2006) also suggested that this earthquake may have been due to slip along or near to the Roum Fault.

| Text (with hotlink) | Original Language | Biographical Info | Religion | Date of Composition | Location Composed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damage Reports from Textual Sources | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| The Times | English |

Background

|

n/a | March and April 1837 CE | London | The Times generated two news reports for the 1837 CE Safed Quake. The first, published on 1 March 1837 CE, included a letter from the British Consul in Beirut and estimated 3000 victims and extensive destruction in Safed, Tiberias, and surrounding villages, The second report, published on 12 April 1837 CE, contained an extensive list of towns, cities, and villages affected along with estimates of structural damage and the number of people killed - which had more than doubled from the initial report. |

| Article in the Missionary Herald by William McClure Thomson | English |

Biography

|

Protestant Christian | November 1837 CE | William McClure Thomson experienced the earthquake in Beirut and engaged in a relief mission to a number of towns and villages affected by the earthquake reaching Safed 17 days after the main shock. He wrote up an extensive description of the damage and human suffering in the Missionary Herald 10 months later. | |

| Edward Robinson | English |

Biography

|

1838 CE | Edward Robinson visited Safed and other affected towns about 18 months after the 1837 CE Safed Quake. He supplied many observations of seismic effects. He also reported second hand accounts that a large mass of bitumen the size of an island or a house was discovered floating on the Dead Sea and the castle at Hunin was rendered uninhabitable - both after the 1837 CE Safed Earthquake. | ||

| The Land and The Book by William McClure Thomson | English |

Biography

|

Protestant Christian | 1857 CE based on first hand recollections 20 years earlier. | William McClure Thomson experienced the earthquake in Beirut and engaged in a relief mission to a number of towns and villages affected by the earthquake reaching Safed 17 days after the main shock. He wrote up an extensive description of the damage and human suffering in The Land and the Book 20 years later. It contains some additional details that were not present in his original report in the Missionary Herald. | |

| Other Authors | ||||||

| Text (with hotlink) | Original Language | Biographical Info | Religion | Date of Composition | Location Composed | Notes |

´ Seismic Effects from Amiran et al (1994)

Reported damaged localities from

Zohar et al. (2016: Table 3)

Nabatiya

Qana

el-Fara

el-Salha

Jish

Marun Al-Ras

Bint-Jbeil

Malkiyya

Qadas

Yaâtar

Tebnine

Hunin Castle

Baniyas [Israel]

Metula

Zeqqieh

Deir Mimas

el-Khiam

el-Tahta

Deir Mar-Elias

Qaddita

Jibshit

Gaza

Arraba

Attil

Qaqun

Tubas

Ajloon

Nablus

Zeita

Harithiya

Jerusalem

Kfar Birâim

Lake Tiberias

Hasbaya

Kafr Aqab

Jeresh.

Areopolis

Hula

Tarshiha

Dallata

Jaffa

Mrar

Ein-Zeitun

Tyre

Atlit

Meron

Eilabun

Akko

Migdal

Irbid

Reina

Safed

Tiberias

Hadatha

Haifa

Zemah

Kafr Kanna

Kafr

Sabt

Lubiya

Nazereth

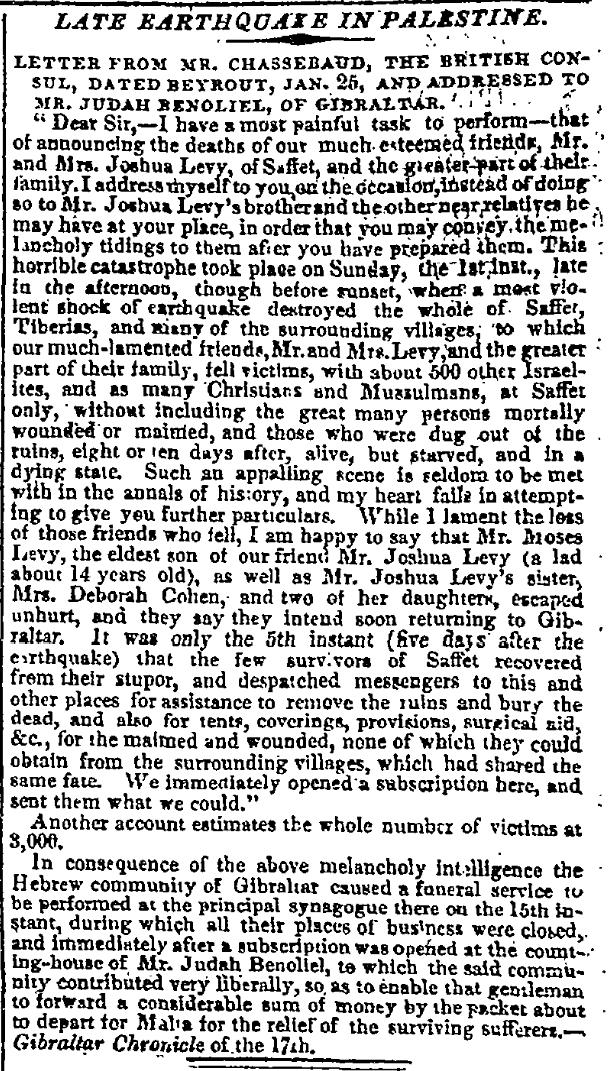

" Dear Sir, —I have a most painful task to perform — that of announcing the deaths of out much esteemed friends Mr. and Mrs. Joshua Levy, of Saffet, and the greater part of their family. I address myself to you on the occasion, instead or doing so to Mr. Joshua Levy's brother and the other near relatives he may have at your place, in order that You may convey the melancholy tidings to them after you have prepared them. This horrible catastrophe took place on Sunday, the [latlnat?], late in the afternoon, though before sunset, where a most violent shock of earthquake destroyed the whale of Saffet, Tiberias, and many of the surrounding villages, to which our much-lamented friends, Mr.and Mrs. Levy, and the greater part of their family, fell victims, with about 500 other Israelites, and as many Christians and Mussulmans, at Saffet only, without including the great many persons mortally wounded or maimed, and those who were dug out of the ruins, eight or ten days after, alive, but starved, and in a dying state. Such an appalling scene is seldom to be met with in the annals of history, and my heart fails in attempting to give you further particulars. While I lament the lots of those friends who fell, I am happy to say that Mr. Moses Levy, the eldest son of our friend Mr. Joshua Levy (a lad about 14 years old), as well as Mr. Joshua Levy's sister Mrs. Deborah Cohen, and two of her daughters, escaped unhurt, and they say they intend soon returning to Gibraltar. It was only the 5th instant (five days after the earthquake) that the few survivors of Saffet recovered from their stupor, and dispatched messengers to this and other places for assistance to remove the ruins and bury the dead, and also for tents, coverings, provisions, surgical aid, etc., for the maimed and wounded, none of which they could obtain from the surrounding villages, which had shared the same fate. We immediately opened a subscription here, and sent them what we could."Another account estimates the whole number of victims at 3,000.

| Year | Reference | Corrections | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late in the Afternoon on Sunday 1 January 1837 CE | Sunday late in the afternoon though before sunset on the 1st of January | none |

January 13, 1837. The first day of

this year will be long remembered as the

anniversary of one of the most violent

and destructive earthquakes which this

country has ever experienced. The shock

occurred at half past four o’clock, P. M.,

and was neither preceded or followed by

any remarkable phenomena. A pale smoky haze

obscured the sun and have a touch of

sadness to the scene, and a lifeless and

almost oppressive calm settled down upon

the face of nature; but these appearances

are not uncommon in this country.

In Beyroot itself but little injury was

sustained, although very many of the

houses were badly cracked, but on the river

flat, east of the town, the houses

were greatly injured, some thrown down,

and a few persons wounded. For several days

succeeding the shock flying reports from

various quarters gave frightful accounts of

towns and villages overthrown and lives lost;

but so slow does authentic information travel

in this country, that it was not until eight days

had elapsed, that any reports which ‘could be relied on were received.

Letters arrived on that day from Safet, stating that the

place was utterly destroyed, not a house remaining of any

description; and that Tiberias and many other places

had shared the same deplorable fate. Some of the letters

stated that not more than one out of a hundred of the

inhabitants had escaped, while others more correctly

declared that out of a population of 10,000 at least

6,000 had perished.

As soon as these awful facts were sufficiently ascertained to

justify it, collections were taken up at Beyroot to relieve

the survivors, and persons appointed to proceed to the scene

of distress and superintend the distribution of the articles and

assist in taking care of the wounded. To aid in this work,

and also to obtain accurate information, so that further

measures and more effectual might be adopted to relieve

their distress, Mr. Calman and myself left our homes this

morning for Safet. Seven hours hard riding brought us to

this noted locality, where the great whale cast forth the

rebellious prophet. So tradition declares; and as no one can

prove the contrary, and the smooth sand beach renders the place

altogether adapted to the purpose, the people rest quite assured

of the fact.

I do not remember any occasion when I left my family with greater

anxiety than on the present. So large a circle, with so many cares,

my own work already so accumulated upon my hands, my health doubtful,

while the season promised nothing but bad roads, storms of rain and snow,

and on the mountains fierce cold. He, however, in whom our life is,

can easily protect all concerned, both at home and abroad, from every

evil, and render our journey prosperous and profitable. My ardent desire

is to promote the glory of God and honor the gospel amongst the Jews

and Moslems of that region, by alleviating the sufferings of the poor,

the sick, the wounded, and orphan; and this will be cheaply purchased

at any expense of time, toil, and danger.

Spent a large portion of this evening in reading and explaining the history

of Jonah to a Turk. I read also and examined the third chapter of John to

him, and endeavored to convince him that there was no savior but Christ, and no

possibility of reaching the kingdom of heaven without a new heart.

He listened more patiently than any Moslem I have conversed with, but was very

loth to admit the doctrines taught; perhaps the more so as several Maronite

Christians were present.

14. Leaving a sleepless couch long before it was light, we made an early start,

and crossing the little river called Nehar II Owel, and passing through the rich

and beautiful gardens which environ that ancient and great city, we entered Sidon.

here we were joined by the English consular agent, seignor Abello, and his two sons.

After a hasty breakfast we set off for this place, but so slow do animals and Arabs

move in this country, that it was not until ten o'clock at night that we reached Tyre.

Cold, muddy, and hungry, we lay down without a fire, in a house so terribly shattered

by the earthquake as to promise a grave rather than a shelter. The owner of the house,

the United States consular agent, would on no account consent to sleep in it. At Sidon

from seventy to one hundred houses had been altogether, or in part, thrown down, and nearly

all were badly cracked, while seven persons were reported to have been killed. In this place

the destruction is far greater. We rode into town last night over the prostrate wall.

The road was nearly blocked up with ruins, and every where the wind, now blowing almost

a hurricane, growled through shattered walls and broken windows; while half suspended

shutters and unclosed doors were creaking, clattering, and banging in dreadful 'confusion.

My horse absolutely refused to enter the frightful place, until I descended, and quieting her

fears, led her into town.

15. Spent this morning in prayer and reading the Scriptures, after which we took a survey of

the place, gave medicine to the wounded; and although it was the Lord's day, we proposed to leave

for Safet. The accounts from that place are so distressing as to leave no doubt on our minds

that it is a work of mercy to hasten to the relief of the sufferers, even by traveling on this sacred

day. Tyre is considered by the inhabitants as nearly ruined, and not even the best houses will be

habitable without tearing down and rebuilding a large part of what remains. Twelve persons were killed

at the time of the earthquake and thirty wounded.

16. Slept at Kahnah last night, a village about three hours from Tyre, The earthquake has not been

very destructive in this place or vicinity, but the people are afraid to sleep in their shattered houses,

especially as the earth still continues to tremble. Our ride yesterday evening was delightful and

refreshing. The wind, which had hitherto been strong and cold, had now settled into a soft southern breeze,

the sky had cleared up, and all nature smiled. The road took us over Alexander's famous causeway,

passed a strong castle dreadfully shattered and partly fallen, and then I leaving the sweet sea-beach

for the fertile plain, we reached the mountains in a little more than an hour, by a very gradual ascent.

This lovely plain has been a thousand times deluged with the blood of Europe, Asia, and Africa.

This peaceful pasture-field for Syrian goats has often trembled with thundering chariots and

thundering cannon, and the dreadful shock of countless cohort's rushing into battle. And these gently,

gracefully swelling hills have witnessed deeds that made heaven weep and hell laugh, from the thirteen

years siege of Babylon's haughty king, and the two thousand crucified victims of Alexander's brutal rage,

down to the scarcely less cruel acts of the self-styled holy crusaders. How changed! Not a soul is seen

of all these countless hosts, not a trophy remains to tell who fought, who conquered, and who died.

Nature has kindly thrown her sweetest mantle of green over the scene; and the impertinent long-eared

goat fattens on the best blood of the old world. These scenes

formed the theme of conversation as we

quietly pursued our way over sloping hills and up winding valleys to Kahnah; and I have seldom found

natives so well informed, or so well disposed for serious

conversation, as our companions. Both

father and son had read the Bible with I much attention and profit, and although Catholics, were far more enlightened

and liberal than the common mass of that bigoted community. One of the sons, in particular, was quarreling

out-right with Paul's view of divine sovereignty, yet still in such a manner as to show clearly that he had a conscience

and a heart, upon which truth had made a strong impression; and this is what we so rarely meet with in this country as to excite double interest.

Near to a village called Hannany we passed some very old ruins, and amongst other things, that which most interested me was a tomb,

said to be the last resting-place of king David's good friend Hiram. Whether it be so or not, the very thought was interesting.

To meet with a spot that hears the name of an old acquaintance, in so lonely a place as this, formed quite an agreeable incident

in the evening's ride, while the tomb itself was curious and unique. On a platform of large stones, raised several feet high, is

placed a huge block of limestone rock, eight or ten feet square, rudely cut, and bearing evident marks of very great antiquity.

This is the tomb, or sarcophagus; and it is covered with a large flat stone, without the slightest ornament of any kind. If there

ever were houses near, they have all disappeared; and this grey weather-beaten pile stands amidst a few straggling olive trees,

an appropriate memento of death and olden times.

17. We came to Ramash; here we bad a melancholy confirmation of those letters which came from Safet. The place is utterly ruined,

and the people are living in tents, made of broken boards, old mats, brush, grass, mud, in short every thing that could be put

up to shelter them from the cold and rain. Thirty people in this small village were killed, and no doubt the destruction

would have been greater, had not the inhabitants been generally in church at afternoon prayers, and only a small part

of the church fell. We visited the wounded, distributed charity to the poor, and then passed on to Kefr Bureyatun,

where fourteen perished, and a great number were wounded. From this to Jish is about an hour, at which place we

stopped for the night. Not a house of any kind remains standing. Amongst the survivors is the shiekh of the village,

who spent the evening in my tent. He gave a very particular account of the overthrow, but it is too long to repeat.

He had returned to the pasha the names of two hundred and thirty-five, who perished. The remainder, amounting to

nearly sixty in all, had gone to other places; so that he, and five others remained to have the property dug out from

under the ruins, to bury the dead, and prepare to desert the place. Here, as well as at Ramesh, the people were at prayers

in church; but alas! they shared a very different fate. The whole church fell at once, and all, except the priest, who

was in the recess of the altar, perished. Thus more than one hundred and thirty died at their very altars. I visited and

examined the ruined church; and it is perfectly obvious, that not one of the people in the body of the edifice could

possibly have escaped. Fourteen bodies still lay unburied amongst the ruins, and the atmosphere was so infected as to

render it very unpleasant to examine them.

18. In the morning, after distributing charity to a number of the poor who had been sent for, and leaving medicine with the

shiekh and others for the wounded who had been removed to other villages, I took a ramble over the hill on which the place

was built. A very slight examination convinced me that it was entirely of volcanic origin. All the houses had been erected

of volcanic stone, and the rock strata is cast about in utter confusion. On my return to the tent I was much affected by

a very simple incident. Our servant had shot several very beautiful pigeons, and upon inquiring why he had dune it, he said that

the shiekh directed him to do it, as they were now wild, and left without any owners to fly about the miserable ruins.

Poor little lonely creatures, the hand that scattered their daily supply of wheat and pulse is crushed and broken, and those

who once delighted to witness their innocent sport, and listen to their lively chatter, are now all mouldering in the cold grave.

I called the shiekh to ascertain whether some one had not survived the overthrow to whom those pretty birds would

properly belong; and after sometime he recollected an old woman, a distant relative of the lost family; leaving a present for

her, we mounted our horses and hurried away from a scene of such dreadful wretchedness.

The shiekh sent a man to shew us a large rent in the mountain, a little to the east of the village. It may now be about a foot wide and fifty feet long; probably it has

gradually closed up, as from their accounts it was wider when first discovered after the shock. The road to Safet carried us over

an elevated plain entirely covered with volcanic rock, of a very ancient and weather-beaten

character. A small lake or pond on the highest part, I suppose, marks the site of a long extinguished crater.

We passed a village called Cudditha nearly destroyed; and in the valley immediately under Safet, Ayne-Zatoon in utter ruin;

but we did not stop to examine them. We met many Jews going out to Mottenna, a village two hours from Safet, to pray to

a celebrated saint of theirs. Poor refuge in times of such distress! Just before we began to ascend the mountain of Safet,

we met our consular agent of Sidon, returning home with his widowed sister. His brother-in-law, a rich merchant of Safet,

had been buried up to his neck by the ruins of his fallen house, and in that awful condition remained several days, begging and

calling for help, and at last died before any one was found to assist him! As we ascended the steep mountain we saw several

dreadful rents and cracks in the earth and rocks, giving painful indications of what might be expected above. But all anticipations

were utterly confounded, when the reality burst upon our sight.

Up to this moment I had refused to credit the account, but one frightful glance convinced me that it was not in the power of language

to over state such a ruin. Suffice it to say that this great town, which seemed to me like a beehive four years ago, and was still more

so only eighteen days ago, is now no more. Safet was, but is not. The Jewish portion, containing a population of five or six thousand,

was built around and upon a very steep mountain; so steep, indeed, is the hill, and so compactly built was the town, that the roof of

the lower house formed the street of the one above, thus rising like a stairway one over another. And this, when the tremendous shock

dashed every house to the ground in a moment, the first fell upon the second, the second upon the third, that on the next, and so on to

the end. And this is the true cause of the almost unprecedented destruction of life. Some of the lower houses are covered up to a great

depth with the ruins of many others which were above them. From this cause also it occurred that a vast number, who were not instantaneously

killed, perished before they could be dug out; and some were taken out five, six, and one I was told, seven days after the shock, still alive.

One solitary man, who had been a husband and a father, told me that he found his wife with one child under her arm, and the babe with the

breast still in its mouth. He supposed the babe had not been killed by the falling ruins, but had died of hunger, endeavoring to draw

nourishment from the breast of its lifeless mother! Parents frequently told me that they heard the voices of their little ones crying

papa papa, mamma, mamma, fainter and fainter, until hushed in death, while they were either struggling in despair, to free themselves, or

laboring to remove the fallen timber and rocks from their children. 0 God of mercy! what a scene of horror must have been that long

black night, which closed upon them in half an hour after the overthrow! without a light, or possibility of getting one, four fifths

of the whole population under the ruins, dead or dying with frightful groans, and the earth still trembling and shaking as if terrified

with the desolation she had wrought!

What a dismal spectacle! As far as the eye can reach, nothing is seen but one vast chaos of stone and earth, timber and boards, tables,

chairs, beds, and clothing, mingled in horrible confusion. Men every where at work, worn out and wo-begone, uncovering their houses in

search of the mangled and putrefied bodies of departed friends; while here and there I noticed companies of two or three each, clambering

over the ruins, bearing a dreadful load of corruption to the narrow house appointed for all living. I covered my face and passed on through

the half living, wretched remnants of Safet. Some were weeping in despair, and some laughing in callousness still more distressing.

Here and old man sat solitary on the wreck of his once crowded house, there a child was at play too young to realize that it had neither

father nor mother, brother nor relation in the wide world. They flocked around us — husbands that had lost their wives, wives their husbands,

parents without children, children without parents, and not a few left the solitary remnants of large connections. The people were scattered

abroad above and below the ruins in tents of old boards, old carpets, mats, canvass, brush, and earth, and not a few dwelling in the open air; while

some poor wretches, wounded and bruised, were left amongst the prostrate buildings, every moment exposed to death, from the loose rocks around and above them.

As soon as our tent was pitched, Mr. C. and myself set off to visit the wounded. Creeping under a wretched covering, intended for a tent, the first we came

to, we found an emaciated young female lying on the ground, covered with the filthiest garments I ever saw. After examining several wounds, all in a state

of mortification, the poor old creature that was waiting on her, lifted up the cover of her feet, when a moment's glance convinced me that she could not

possibly survive another day. The foot had dropped off, and the flesh also, leaving the leg-bone altogether bare! Sending some laudanum to relieve the

intolerable agony of her last hours, we went on to other but equally dreadful scenes. Not to shock the feelings by detailing what we saw, I will only

mention one other case; and I do it to show what immense suffering these poor people have endured for the last eighteen days. clambering over a pile of ruins,

and entering a low vault by a hole, I found eight of the wounded crowded together under a vast pile of crumbling rocks. Some with legs broken in two or

three places, others so horribly lacerated and swollen as scarcely to retain the shape of mortals; while all, left without washing, changing bandages,

or dressing the wounds, were in such a deplorable state as rendered it impossible for us to remain with them long enough to do them any good. Although

protected by spirits of camphor, breathing through my hand-kerchief dipped in it, and fortified with a good share of resolution, I was obliged to retreat.

Convinced that while in such charnel houses as this, without air but such as would be fatal to the life of a healthy person, no medicines would afford relief,

we returned to our tent, resolving to erect a large shanty of boards, broken doors, and timber, for the accommodation of the wounded. The remainder of our

first day was spent in making preparations for erecting this little hospital.

19. This has been a very busy day, but still our work advanced slowly. We found the greatest difficulty to get boards and timber, and when the carpenters

came, they were without proper tools. In time, however, we got something in shape of saws, axes, nails, and mattocks, and alt of us laboring hard, before night

the result began to appear. The governor visited and greatly praised our work, declaring that he had not thought such a thing could have been erected; and

that the government had not been able to obtain half so good a place for its own accommodation. Some of the wounded were brought and laid down before us,

long before any part of the building was ready for their reception, and are now actually sheltered in it, although it is altogether unfinished. After dark

I accompanied the priest, to visit the remainder of the christian population of Safet. They were never numerous, and having lost about one half of their number,

are now crowded into one great tent. Several were wounded; to these we gave medicine. Some were orphans, to whom we gave clothing, and the poor people had

their necessities supplied as well as our limited means would justify. Amongst the survivors is a worthy man, who has long wished to be connected with us,

and in whom we have felt much interest. He applied about a year ago to have his son admitted to our high school, but he was then too young. When I left

Beyroot it was my intention to bring this lad with me on my return, should he be alive; but alas! his afflicted father has to mourn not only his death,

but that of his mother and all his lovely family but one.

The earth continues to tremble and shake. There have been many slight, and some very violent shocks since we arrived. About three o'clock today, while I was on

the roof of our shanty nailing down boards, we had a tremendous shock. A cloud of dust arose above the falling ruins, and the people all rushed out from them

in dismay. Many began to pray with loud and lamentable cries; and females beat their bare breasts with all their strength, and tore their garments in despair.

The workmen threw down their tools and fled. Soon, however, order was restored, and we proceeded as usual. I did not feel this shock, owing to the fact that

the roof of the shanty was shaking all the time. Once, however, the jerk was so sudden and violent as to affect my chest and arms precisely like an electric shock.

20. Tiberias. Having finished our work, collected the wounded, distributed medicine and clean bandages for dressing the wounds, and hired a native physician to

attend the hospital, we left Safet about half past one o'clock, P. M.; and, after a pleasant ride of five hours and a half, encamped before the ruins of this

celebrated city. It was truly refreshing to breathe once more the pure air of the open country, freed from the horrible sights which have been ever before me,

both waking and sleeping, during our stay at Safet. We passed rapidly down the steep mountain under the at rock where Jeremiah is said to have hid the ark,

across the fertile vale of Gennesaret, through the miserable village of Migdol, and along the shore of the beautiful lake, whose sweet waters dashed with gentle

murmurs on the sacred shore. A train of emotions stole over the heart, more agreeable than sad, although the eye was filled with tears at the recollection of

what we had already witnessed, and at the thought of that which we had in prospect. I shall not soon lose the impression of this ride. Not a breeze stirred

the smooth surface of the Gennesaret, nor a leaf trembled on the topmost bough of the mountain pine. The sun settled quietly down behind the hills of Nazareth,

and the full pale moon shone dimly through a hazy atmosphere on lake and land, faintly revealing the mountains of Bashan, the snows of Jible II Sheikh, and the

place where Safet was, that “city set upon a hill which could not be hid” — and the mountain, where the Savior preached the best sermon the world ever heard,

and near which he is said to have fed the five thousand with the five barley loaves. These and many other places, rich in sacred associations, were seen in

misty outline stretching far away from Gennesaret, sweet Gennesaret, lovely shore. While the tinkling bell, the lowing kine, the bleating flocks, and the

barking dogs struck a chord oft struck before at home — my father’s, mother’s, boyhood’s home.

21. The destruction of life at Tiberias has not been so great, in proportion to the population, as at Safet, owing mainly to the fact, that Tiberias is built

on a level plain, and Safet on the declivity of the mountain. Probably about seven hundred perished here, out of a population of twenty-five hundred; while

at Safet four thousand out of five thousand Christians and Jews were killed; and not far from one thousand Mussulmans.

We visited all the wounded to-day, and find them much more comfortably arranged in tents than at Safet. There has been better order and more enterprise

amongst the people, who are said to be of a higher character than those of Safet, and less affected by those violent party divisions which agitate the Jewish

community. As an instance of the confusion and wretchedness that prevailed during the first days after the earthquake, take the case of the only Jewish

physician in Tiberias. He is immensely wealthy; his wife and children were killed at his feet, his own leg broken off below the knee, and held fast by the

rocks which had fallen upon it. In this

condition he continued two whole days, begging and crying for some one to

come and take away the few stones that were upon him and set him free. He rose in his offer to three hundred dollars:

but to no effect; every one had his own wife, or children, or friends in the same condition, and none would attend. At length the flies got to his wife and

children, and to his own wound, when in

despair he seized a pole which lay near him and tried to bring down upon his

head some stone that lay above him, in

order to end both his life and sufferings

at the same time. Still, this man is now

doing well, and promises soon to recover, In the afternoon we went down to the

hot baths, which are not injured in the

least, although not more than a mile and

a half, from the city, where every wall is

thrown down. The rooms attached to

the bath are filled with wounded, some

of them in a most deplorable condition, to whom we gave medicine and clothes.

We all took the bath, but the water was

too hot to be either agreeable or healthy. As the thermometer rose to the top of the scale instantly. I have no means of

ascertaining how great the heat in the spring is. To me it seemed hotter than when I was here four years ago, and the sulphurous gas escaping from the surface

much more offensive. The people informed me that at the time of the earthquake, and for some days subsequent to it, the quantity of water was immensely

increased; and it was so hot as to render it impossible to pass along the road across which it flows. This I suppose

to have been the fact, but the numerous stories about smoke and boiling water issuing from many places, and fire in

others, I believe were mere fabrications. I could find no one who had actually seen these phenomena, although nearly all had heard of them.

22. Nazareth. We spent this morning in distributing charity to the poor, and medicine to the sick, and then set off for this place. Our road for the first

two hours carried us over a very fertile country, covered with volcanic stones. The houses of Tiberias are entirely built of this stone; and there can be but

little doubt that the lake itself was formed by a volcano. One hour and a half from Tiberias we turned aside from the road to examine the spot where tradition

states that our Savior fed the hungry multitude with the barley loaves. The situation is very well adapted to the narrative, at least so far as "much grass" is

concerned. Indeed I have seldom seen richer pastures, even in America, than on the hills and plains of Galilee. The Mount of Beatitudes is but 'a small distance from

this to the west, and the hill of Safet rises in bold relief to the northeast, beyond a most lovely plain. This elevated plain, owing to the different states of

cultivation and the various kinds of grain and grass which covered it, was most beautifully variegated, like a rich carpet. So striking was the resemblance, that

even our Arab attendants called out to us to look at the "sejady keberry" — the great carpet. After we had broken off some specimens from the rock upon which our

Savior is said to have stood when he taught the people, we proceeded on our way, and in an hour reached Luby. At this village I slept four years ago. Now it is

one ghastly heap of ruins. One hundred and forty-three of the poor people were killed. The old sheikh escaped, while his whole family, eleven in number, perished.

This was once a considerable place, and the prospect is particularly interesting, taking in a large part of Galilee, and extending over the lake to the snow capt

mountains of the Haooran. After visiting the wounded, and distributing some clothing and money to the poor, we hurried on to Segara, about an hour further west,

and close to the northern base of mount Tabor. Before we reached this place, it is worthy of remark, that the lava entirely disappeared, and a hard, whitish

lime-stone rock took its place, the land being extremely fertile. We passed over the battle-field where general Kleber sustained for half a day the attack of the

whole Turkish force, twenty or thirty times greater than his own, until Bonaparte, learning his critical situation, hurried to his relief with a small reinforcement,

when the Turks fled in utter confusion. The French were encamped in this village for a considerable time, and one old man, who remembers Kleber well, interested

me exceedingly by his animated descriptions of the numerous battles and skirmishes in which they were constantly engaged. He wanted to know whether there were any

such bold men now in the world as those Frenchmen, and gave it as his opinion that a few thousand of them would conquer all Syria. — Segara lost fifty of its two

hundred inhabitants by the earthquake; and, like Luby, the houses were all destroyed.

From this to Nazareth is three hours, and our road led us along the base of a low mountain, to Kefr Kenna, which we reached in an hour and a half. We started a

great many partridges, foxes, and jackals, and saw gazelle bounding over the plain below. Tabor, covered with trees and under brush, is said to abound with wild hogs,

which are often hunted, more for sport than use, as their flesh is an abomination to the Turk and Jew, and not very good for any body. Kefr Kenna sustained no injury

from the earthquake; and as we were anxious to reach Arana before dark, we did not stop to examine either the house where the wedding was celebrated, or the broken

water-pot deposited in the church, or the fountain from which the water was drawn, or any other wonder of the place; still our haste was of small account, for it was

quite dark before we reached the ruins of Arana; and as the houses were all destroyed, the people had mostly left for other places. About one hundred and ninety

persons perished under the ruins, and many were wounded. As we could not remain there over night, we left word for the poor to meet us at Nazareth, which is only a

half an hour distant, and we would attend to them in the morning. Greatly wearied and chilled with the mountain dew, we reached Nazareth about seven o'clock, and were

hospitably entertained by one of our companions, Ibrahim II Cuprasy — Abraham the Cypriot — who had assisted in our work for the last five days. The whole upper story

of our host's house fell in at the time of the earthquake, but a merciful providence had so ordered it, that not one of the family was above at the moment. Had they been

in their usual sitting room, all must have perished. The lower part, consisting of strong vaults, was not even cracked, and here we were received and entertained while

many tons of earth and rock lay piled above our heads. As the earth still trembles and shakes, we preferred sleeping in our tents, although it was quite cold.

Nazareth has sustained but little injury. Our friend's house, and the great Latin convent suffered most. Only five persons were killed, four of them, if I remember correctly,

at the convent. This beautiful building is terribly shattered in many places, and it would not have required much more to have brought it all down upon the heads of the monks.

Many workmen are busily employed repairing the terraces and broken walls; and, if not interrupted, they will soon obliterate any trace of the fearful earthquake.

According to appointment, many poor came from Arana, who being all known by our host, we were in no danger of imposition. We distributed the remainder of our clothing amongst

them, sent medicine for some of the wounded, and leaving a small sum of money with our friend to be expended for the benefit of the needy, we left Nazareth about noon, and

turned our face towards home.

Our route brought us to Saphoory in about an hour, the direction being nearly north from Nazareth. This is a considerable village, with an old castle commanding the hill,

and a sweet vale spread around its base. The earthquake did no injury here. Crossing the fertile plain of Zabulon, we took the wrong road, which led us out amongst some

wild hills, covered with bushes and luxuriant grass; and after wandering up and down for some time without any path, we ascended a hill, which, overlooking all the rest,

gave us a splendid view of the sea, the city, and vast plain of Acre stretching far away to the northwest, and at the same time a glimpse of our road, in a deep valley

to the right of us. Without much more trouble we got down to it, where also we met our muleteers, not far from Abilene, a large village pleasantly situated on a low

mountain to the left of the road. Abilene is distinguished from most mountain villages by a high minaret, indicating a moslem population. Soon the narrow valley down

which our road lay, opened into the splendid plain of Acre; but not wishing to enter the city, we turned directly north along the head of the plain, now and then crossing

a little spur of the mountain, covered with shrubbery, and generally adorned with a small village. The first was called Themera, and the next Damona, which seems to have

once been strongly fortified, parts of the old wall still remaining in many places. They are favored with but one well of water, which is deep and brackish besides.

Here a man was constantly employed in drawing up the water, aided by one of the simplest pieces of machinery imaginable, which he turned with his feet. Deut xi, 10.

All the villagers seemed to enjoy the fruit of his labor without distinction. Birwy is another considerable village, about half an hour to the north of Damona,

distinguished by a very large and beautiful mound, near the fountain which supplies it with water. This is the largest artificial mound I ever saw. It cannot be less

than eighty rods in circumference at the base, and is nearly one hundred feet high. Two or three mounds of a similar character are seen in other parts of the plain,

generally near and commanding some fountain of water. These were probably erected before the time of Joshua, and were intended to command this fertile plain; and

before the invention of cannon, they might have answered the purpose very well. Near this fountain I found a number of columns, of the rudest form, and most antique

appearance of any that I have examined. From Birwy we ascended a hill, and came to a Moslem village called Jedaidy. It was now very dark, and we inquired the way to

Kefr Yooseph, where we intended to sleep. We soon, however, lost our road; and after wandering about for some time, succeeded in getting back to Jedaidy. By dint of money,

begging, and scolding, we succeeded in obtaining a guide; and leaving word for our muleteers to follow us, hurried forward towards our sleeping place, for it was now cold,

and we were not a little fatigued and hungry. The sheikh of Kefr Yooseph, whom we had met in Safet, received us with boisterous welcome, and soon our room was filled with

half the village. After waiting a long time for our muleteers in vain, we got a cold supper of olives, oil, cheese swimming in oil, and coarse bread; but to the hungry

soul every bitter thing is sweet. Our kind host supplied us with a sort of bed, and we lay down on the floor to fight flees until morning.

23. Not knowing what had become of our servants we set off early in pursuit of them, still keeping along the head of the plain. In two hours we passed Kwoikat, Gabzia,

Sheikh Daood, Masookh, Bussa, and two or three other villages, whose names I forget. At Masookh, we crossed a considerable stream, which I suppose is the river Belus,

and whose banks were adorned with large patches of sugar-cane. There are many flouring mills here, and gardens of orange and lemon trees. Near this place is the great

mountain whose waters conducted across the plain in an arched aqueduct for eight or ten miles, supplies Acre with an abundance of that indispensable article. The plain betwixt

Masookah and cape Blanco is devoted almost exclusively to the raising of grain. Thousands of acres were already green with the promise of a future harvest, while thousands more

had just received the precious seed, and numerous ploughs were actively engaged in turning up the remainder, and preparing it for the sower that soweth the seed. We saw

eighteen or twenty gazelle at one time, and some of our company gave chase to them, but in vain. They capered and bounded in mere sport, far ahead of the fleetest of our horses.

Deer are much more numerous than in America, but not so large or beautiful. At the foot of cape Blanco we found an English gentleman from India, accompanied by Said Ali, one of

the young men whom Mohammed Ali sent to England several years ago to be educated. He is still a Moslem, speaks English very correctly, and is altogether a most agreeable and well

informed young man.

After referring incidentally to the contemplated post route between the Mediterranean and India, by way of the Euphrates and the Persian Gulf, Mr. Thomson remarks upon the country on

the river just named and the importance of that channel of communication.

The valley of the Euphrates is becoming more and more important and promising, as a field of missionary exertion. For some time past I have become acquainted with a priest of the

Chaldean church, from Mosul, from whom I have received ample corroborations of former reports. He gives a particular account of several hundred thousand Nestorian Christians

residing in the mountains north of Mosul; and there are, he says, an equal number of Christians of the Chaldean church. Besides these there is a large sect, called Dowasen,

whom he describes as worshipers of the devil. They have no books, not even the knowledge of letters. He says there are a thousand villages of them in the mountains between

Mordin and the great lake Ooroomiah. The road to all these is by the way of Aleppo, Beer, and Mordin, the precise route of the Euphrates expedition. The road, which has generally

been dangerous on account of wandering Arabs, is now open, and caravans pass regularly from Mosul, Mordin, and the regions beyond, to Orfa, Beer, and Aleppo. Since the establishment

of English mercantile houses in Aleppo, their goods have been extensively introduced through all that part of the valley. My informant confirms the account given of these oriental

Christians by Mr. R., the Arabic translator and corrector of the Malta proofs, that they would gladly receive the Holy Scriptures and send their children to schools. Mr. R. is himself

a native of Mosul, where his father was a priest, well known to my informant. I have long felt a deep interest in this people, which increases in proportion as more accurate information

is obtained. And as the language is pure Arabic, I look to that valley as promising a great outlet to our books. The first step towards this will be the establishment of a

strong missionary station at Aleppo.

But to return from this digression, Mr. Stewart, who is returning from Jerusalem, confirmed the reports from that place, which I had heard in Safet. Little injury had been sustained

in that region; but at Nabloos the shock had been very violent. The town itself was nearly destroyed, but not more than one hundred and fifty persons perished. Many villages in the

surrounding mountains are reported as overthrown, but these reports need confirmation. In company with our two friends we clambered over the frightful rocks of cape Blanco, along the

astonishing pass cut in the white rock overhanging the blue sea; refreshing ourselves a while at the great fountain called Scandaroon, and passing the still greater one of Kass el Ayne,

which pours forth a river of sweet water at the very margin of the sea, we entered Soor as the dews and shadows of evening began to fall upon us. Here we found our muleteers, who had lost

their road and wandered about nearly the whole night; and thinking that we were ahead of them, they had hurried on all day, hoping to overtake us.

We found that all the inhabitants of Soor had forsaken their houses, and were living in tents. The earth still continued to tremble and the houses not fallen are so badly cracked as to render

it very dangerous to occupy them. Some of the people had drawn up their fishing boats on shore, and covering them like a tent with the sails, transformed them into houses. Others had military

tents, and many had purchased boards, and were erecting wooden shanties. Poor Tyre has been declining for many years, as I learn from the inhabitants. Her trade is entirely taken by Beyroot,

and having received this terrible shock, I fear she will not soon recover.

Dim is her glory, gone her fame;24. We had a slight shock of earthquake last night; and in fact the earth has not been at rest twenty-four hours since we left home. Blessed be the Preserver of life and the Father of mercies, no evil has befallen us. We wake this morning in vigorous health and cheerful spirits. In two hours we crossed the river Kasmia on a strong stone bridge, and the road which was very muddy fourteen days ago is now excellent, so that we had a very pleasant ride of nine hours to Sidon, which we reached at sunset, and took our English friend to see some caves in the side of the mountain, about four hours from Tyre, which I had examined before. Near them are a great number of vaults for sepulchres, hewn out of the hard lime-stone rock. They are all of the same form, having a square door opening into a room about six feet square, arranged to accommodate three persons. The doors are all gone, and not a bone is left. How very ancient must be the date of these expensive works. In the plain below are vast piles of stone, and many old wells, proving the existence at some former period of a large city. In fact a great part of the coast between Tyre and Sidon is covered with ruins, and even in some places, the beautiful mosaic Boors of their palaces remain unbroken. The site of ancient Sarepta is ascertained by large quantities of rubbish lying in the plain three hours to the south of Sidon, and there is a small village still bearing that name, on the mountain a mile or two to the east.

Her boasted wealth has fled;

On her proud ruck, alas! her shame,

The fisher’s net is spread.

The Tyrian harp has slumber’d long,

And Tyria’s mirth is low;

The timbrel, dulcimer, and song

Are hush’d or wake to wo!

25. Not wishing to be detained in the morning until the gates were opened, we did not enter Sidon, but pitched our tent at Nehor El Owel - first river —

a considerable stream coming down from lower Lebanon, which is crossed on a high bridge. From this to Beyroot is ten hours, where we arrived in good health,

rejoiced to meet our friends, and mingle our thanksgivings with theirs, for our mutual preservation during a time of unusual anxiety and alarm. Letters had

also been received from Jerusalem, assuring us of the safety and welfare of our dear friends there. We had heard that Ramla was sunk, and many other places

destroyed; and after waiting with — uneasiness nearly two weeks for letters from some one in Jerusalem, we dispatched a courier to ascertain the rea]

state of the case, with directions to meet

me at Safet; and I left home with the

understanding, that, if necessary, |

should proceed directly from Safet to

Jerusalem. Our friends there, for a

similar reason, sent off an express to

Beyroot, and our couriers passed each

other on the road. The truth is that the

violence of the earthquake spent itself

about half way between Beyroot and

Jerusalem; and while all our accounts

from the south seemed to increase our

fears about Jerusalem, they could hear

nothing from the north but frightful stories of ruin and death. But the Lord has

mercifully preserved our lives and the cities where we dwell from this awful

destruction, and blessed be his holy name.

One of the most remarkable circumstances in relation to the earthquake is, that some villages entirely escaped, although directly between two places

which were utterly overthrown. For

example, Jaish is a total wreck, not a

fragment of a house is left standing; but

a small village to the south, and almost

within gun-shot of it, was not injured at all. But the next place is again entirely

destroyed. And so on the road from Tiberias to Nazareth, Segara is overthrown,

Kefr Kenna (Cana of Galilee), a little to

the west, has not a house cracked; while

Arana, just beyond it, is a vast pile of

ruins; but the next village, Saphoory,

escaped entirely. These villages are

situated on the same hills, with no visible impediment between them; and upon

what principle these astonishing exceptions can be accounted for I know not.

One thing, I think, is certain, that all

this region has been thrown up by volcanic fire. The strata incline into the valleys on every side, shewing that they have been forced up in the centre by

some mighty power acting beneath. Now I would venture to inquire whether

it might not result in such a mighty upturning of the foundations, that certain

places become insulated, separated from the surrounding rock, and the intervals

filled up with earth and soft substances; and as these would break the violence of the concussion, villages erected upon

them might escape, although in close vicinity to others which are entirely destroyed. This is the fact, however it

may be accounted for.

As to the extent of the injury wrought

by the earthquake, nothing like accurate information has been ascertained. Much

has been reported, but little that can be

depended upon of the destruction of villages in Anti-Lebanon. It has certainly been very violent in that quarter as we

learn from Huslayah and Rashaiah, the

two most important towns in Anti- Lebanon. At Tiberias I ascertained that

all the villages on the east shore of the

lake were in ruins; and the same was

true as far east in the land of Gilead and Bishan as we had any information from.

The shock was felt in Egvpt, and at

Mount Sinai, as we are informed by the

English travelers who were there at the

time. The lake of Tiberias is undoubtedly the centre of this mighty concussion,

and it would not be at all surprizing if a fresh volcano should break out in some of the surrounding mountains.

Isaiah says, “When thy judgments are

in the earth the inhabitants of the world

will learn righteousness.” — The world

that reads and hears of them may learn

righteousness, but I fear those who are

exercised thereby are most commonly

hardened. As he says of the Israelites in another place, when suffering afflictions, “They shall fret themselves, and

curse their king and their God and look

upward.” There is something in the

very magnitude of great calamities which

seems to harden the heart. Certainly

what I have witnessed during the last

two weeks has exhibited human nature

in a more odious light than I had before

viewed it. There is no flesh in the

stoney heart of man. Such foul specimens of dishonesty, robbery, cruelty,

avarice, and amazing selfishness I never heard or read of. Nothing but dreadful

punishments, oft inflicted, preserved the

ruined places from becoming scenes of indiscriminate plunder. Taking advantage of their necessities, no man would

work except for enormous wages. The

head rabbi of Tiberias told me that they

had to pay about sixty dollars for every burial, although it required only an hour

or two to accomplish it. He had paid

out of the public purse upwards of,

seventy thousand piastres for this purpose alone. Nor are the Jews a whit

behind the Moslems in this cold-hearted

villany. I never saw a Jew helping another Jew, excepting for money. After

our hospital was finished, we had to pay a high price to have the poor wounded

creatures carried into it. Not a Jew, Christian, or Turk lifted a hand to assist

us, except for high wages.

Syria and the Holy Land

| Year | Reference | Corrections | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 430 pm 1 Jan. 1837 CE | The shock occurred at half past four o’clock, P. M.and the first day of this year (1837 CE) will be long remembered as the anniversary of one of the most violent and destructive earthquakes which this country has ever experienced |

none |

1 Seetzen in Zach's Monatl. Corr. XVIII. p. 441. Burckhardt, p. 394. English. Lane's Mod. Egypt. IL p. 372.

2 The Kuntar is about 98 lbs.

More definite and trustworthy

3. W. M. Thomson in Biblioth. Sacra, 1846, p. 203.

Setting off again at 7.30

2 Elliott l. c. p. 353, "As the hill on which the town is built is precipitous,

and the roofs are flat, public convenience has sanctioned the conversion of these

into thoroughfares; so that, both on mules and on foot, we repeatedly passed over

the tops of dwellings."

3 Jowett Chr. Res. in Syria, p. 180. Lond.

4 Nau in 1674 speaks of seven synagogues; p. 561. So too Von Egmond and Heyman,

and afterwards Pococke; the former also mention the high school and printing

office; Reisen II. p. 41. Pococke II. i. p. 76. Schulz in 1755 gives the number

of Jews at two hundred; the number of students in the school at twenty; and says

the printing office had been in the village 'Ain ez-Zeitun in the valley

north, but was then given up. Leitungen, etc. Th. V. pp. 211, 212.

In 1833 Mr Hardy mentions two presses at work, and two others in the

course of erection. The type and furniture were said to be made here

under the direction of the master. The execution of the works printed was

quite respectable; and near thirty persons were employed in the different

departments of composing, press work, and binding. See Hardy's Notices,

p. 244. Comp. Monro II. p. 13. See more further on.

1 Van Egmond and Heyman II. p. 43 sq. Pococke II. i. p. 76. Burckhardt p. 317.

2a Is. 1, 6.

1a It would not be at all surprising, if this estimate of the destruction of life were

found to be considerably exaggerated. Compare the varying estimates of the population of

Safed above, p. 420, note. See Mr Thomson's Report, referred to in the next note.

2b Mr Thomson visited all these places in the course of his journey; see his

Report, Miss. Herald Nov. 1837. pp. 442, 44

Safed lies on a high isolated hill

| Year | Reference | Corrections | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Jan. 1837 CE | Jan. 1st, 1837 CE | none |

on the first day of January, 1837, the new year was ushered in by the tremendous shocks of an earthquake, which rent the earth in many places, and in a few moments prostrated most of the houses, and buried thousands of the inhabitants of Safed beneath the ruins.- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

The castle [in Safed] was utterly thrown down- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

the Muhammedan quarter, standing on more level ground and being more solidly built, were somewhat less injured- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

when the terrific shock dashed their dwellings [in the Jewish Qarter on the western slope of Safed] to the ground, those above fell upon those lower down ; so that, at length, the latter were covered with accumulated masses of ruins.- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

Slight shocks continued at intervals for several weeks- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

Many were killed outright by the falling ruins; very many were engulfed and died a miserable death before they could be dug out; some were extricated even after five or six days- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

According to the best accounts, there perished, in all, not far from five thousand persons; of whom about one thousand were Muhammedans and the rest chiefly Jews (footnote: It would not be at all surprising if this estimate of the destruction of life were found to be considerably exaggerated.).- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

the place [Safed] was still [18 months later] little more than one great mass of ruins.- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

In the eastern quarter [of Safed], where we had pitched our tent, many of the houses had been again built up; though more still lay around us level with the ground.- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

The southern quarter [of Safed] was perhaps the least injured of all- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

The castle [on the Citadel in Safed] remained in the same state in which it had been left by the earthquake, a shapeless heap of ruins; so shapeless indeed, that it, was difficult to make out its original form- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

Safed appears obviously to have formed the central point of this mighty concussion, and to have suffered more, in proportion, than any other place; except perhaps the adjacent villages of 'Ain ez-Zeitun and el-Jish.- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

the destruction, as we have seen, extended more or less to Tiberias and the region around Nazareth; many of the villages in the region east of the lake were likewise laid in ruins; many houses were thrown down in Tyre and Sidon, and several were cracked and injured even in Beirut- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

In Nablus, also, the shock was severely felt, and a number of persons were killed.- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

It is a remarkable circumstance, that some villages remained entirely unaffected by the earthquake, although situated directly between other places, which were destroyed. Thus a small village near to el-Jish and Safed was uninjured. On the way from Tiberias to Nazareth, esh-Shajerah was overthrown; Kefr Kenna received no harm; er-Reineh was levelled to the ground; Nazareth sustained little damage; and Seffurieh escaped entirely. All these places lie upon the same range of hills, with no visible obstruction to break the shocks between them; and the exceptions are therefore the more wonderful- Robinson (1856 v.2:420-424)

after the earthquake of Jan. 1st, 1837, a large mass of bitumen (one said like an island, another like a house) was discovered floating on the [Dead] sea, and was driven aground on the west side, not far to the North of Usdum

since the great earthquake of January 1837, no part of the castle [at Hunin] has been habitable

1 "Earthquake! earthquake!"

* ["Kefr Bur'iam was for many centuries a place of Jewish pilgrimage. It was said in the twelfth century to contain the tombs of

Barak the conqueror of Slsera, and Obadiah the prophet ; to these was added that of Queen Esther, In the sixteenth century.

Round these shrines the Jews of Safed were wont to assemble each year on the feast of Purlm, to eat, drink, and rejoice —

a few Individuals of special sanctity still make a passing visit to the spot, to pray over tombs so traditionally holy"

- [Handbook for Syria and Palestine, p. 440).— Ed.]

It was just before sunset on a quiet Sabbath evenin

| Year | Reference | Corrections | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| just before sunset 1 Jan. 1837 CE | just before sunset on a quiet Sabbath evening — January 1, 1837 | none |

|

the earthquake of 1837 prostrated a large part of [Tiberias'] walls, and they have not yet been repaired, and perhaps never will be

Other locationsFootnotes1 Thomson (1861:396) stated

The temperature of the fountains varies in different years, and at different seasons of the same year. According to my thermometers, it has ranged within the last twenty years from 136° to 144° (Farenheit). I was here in 1833, when Ibrahim Pasha was erecting these buildings, and they appeared quite pretty. The earthquako which destroyed Tiberias in 1837 did no injury to the baths, although the fountains were greatly disturbed, and threw out more water than usual, and of a much higher temperature. This disturbance, however, only temporary, for when I came here about a month after the earthquake, they had settled down into their ordinary condition.

it is said that waves flooded the coast of Lake Tiberias but it is not clear whether this happened before, during, or after the earthquake (Shkelov, 1837; Kerhardene, 1859).

Abbasi, M., 2006. The Tabri family and leadership of the Arab community of Tiberias during late

Ottoman and British Mandate periods. Cathedra, 120, 183–200.

Avi-Yonah, M., 1951. Historical geography of Eretz Israel. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute.

Avi-Yonah, M., 1980. In the days of Rome and Byzantium. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute.

Avissar, O., 1973. The book of Tiberias. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House Ltd.

Ben-Arieh, Y., 1997. Painting the Holy Land in the nineteenth century. Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi

Publications.

Ben-Arieh, Y., 2001. The view of Eretz Israel as reflected in biblical painting of the 19th century. In:

R. Aharonson and H. Lavsky, eds. A land reflected in its past. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University

Magnes Press and Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Press, 255–279.

Ben-Yaakov, M., 2001. The immigration and settlement of North African Jews in nineteenth century

Eretz-Israel. Thesis (PhD). The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Ben-Zvi, I., 1954. Eretz-Israel under Ottoman rule. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute.

Bnayahu, M., 1946. Rabbi Yaa’kov Birav - Zimrat Haa’retz. 5th ed. Jerusalem: Mekorot-Eretz Israel.

Buckingham, J.S., 1822. Travels in Palestine through the countries of Bashan and Gilead. London:

Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

Burckhardt, L.J., 1822. Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. London: J. Murray.

Calman, S.E., 1837. Description of part of the scene of the late great earthquake in Syria. London:

Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields.

Carne, J., 1826. Letters from the East. London: H. Colburn.

Clarke, E.D., 1810–1823. Travels in various countries of Europe, Asia and Africa. London: Printed for T.

Cadell and W. Davies.

Davie, F.M. and Frumin, M., 2007. Late 18th century Russian Navy maps and the first 3D visualization of the walled city of Beirut. E-Perimetron, 2 (2), 52–65.

de Aveiro, P., 1927. Itinerario da Terra Sancta, e Suas Particula

de Gramb, M.J., 1840. A pilgrimage to Palestine, Egypt, and Syria. London: H. Colburn.

de Thévenot, J., 1971. The travels of Monsieur de Thévenot into the Levant. Newly done out of French.

Farnborough: Gregg.

Gil, M., 1983. Eretz Israel during the first Islamic period. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University.

Guerin, V., 1880. Description Geographique, Historique et Archeologique de la Palestine. Paris:

L’Imprimerie nationale.

Hasselquist, F., 1766. Voyages and travels in the Levant in the years 1749, 50, 51, 52. London: L. Davis

and C. Reymers.

Heyd, U., 1969. Dah’r al-Omar. Jerusalem: Rubin Mass Ltd.

Horne, T.H., 1836. Landscape illustrations of the bible: consisting of views of the most remarkable

places mentioned in the old and new testaments. London: J. Murray.

Irby, C.L. and Mangles, J., 1823. Travels in Egypt and Nubia, Syria and Asia Minor during the years

1817 & 1818. London: T. White and Co.

Jacotin, P., 1799. Carte topographique de l’Egypte et de plusieurs parties des pays limitrophes. . .

Construite par M. Jacotin, 1:100000. Paris: Jacotin, P.

Jowett, W., 1826. Christian researches in Syria and the Holy Land in 1823 & 1824 in furtherance of the

objects of the church missionary society. Boston, MA: The Society by L. B. Seeley and J. Hatchard.

Karniel, G. and Enzel, Y., 2006. Dead Sea photographs from the nineteenth century. In: Y. Enzel, A.

Agnon, and M. Stein, eds. New frontiers in Dead Sea paleoenvironmental research. Boulder, CO:

Geological Society of America, 231–240.

Kinglake, A.W., 1848. Eothen, or, Traces of travel brought home from the East. New York, NY: George

P. Putnam.

Levin, N., Kark, R., and Galilee, E., 2010. Maps and the settlement of southern Palestine, 1799-1948:

an historical/GIS analysis. Journal of Historical Geography, 36, 1–18.

Light, H., 1818. Travels in Egypt, Nubia, Holy Land, Mount Lebanon and Cyprus in the year 1814.

London: Printed for Rodwell and Martin.

Maden, R.R., 1829. Travels in Turkey, Egypt, Nubia and Palestine in 1824, 1825, 1826 and 1827.

London: Henry Colburn.

Madox, J., 1834. Excursions in the Holy Land, Egypt, Nubia, Syria. Including a visit to the unfrequented

district of the Haouran. London: Richard Bentley.

Mariti, G., 1791. Travels through Cyprus, Syria, and Palestine. London: G. J. and J. Robinson.

Mendel, M., 1839. The book of ‘Korot HaI’tim of Yeshuron’ in Eretz Israel. Jerusalem: Anshine M.,

1930.

Nee’man, A., 1837. Arieh Nee’man’s letter from Safed to Amsterdam about the earthquake in Safed.

In: A. Ya’ari, ed. Letters of Eretz Israel. Tel-Aviv: Gazit, 363–367.

Nir, Y., 1985. The beginnings of photography in the Holy Land. Cathedra, 38, 67–80.

Olin, S., 1844. Travels in Egypt, Arabia Petra, and the Holy Land. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Pococke, R., 1745. A description of the east and some other countries. London: Bowyer, W

Pueckler-Muskau, H.L.H.F., 1844. Aus Mehemed Ali’s Reich. Stuttgart: Hallberger.

Richardson, R., 1822. Travels along the Mediterranean and Parts Adjacent: in Company with the Earl

of Belmore, during the Years 1816-17-18. London: Printed for T. Cadell.

Robinson, E. and Smith, E., 1841. Biblical researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea. A

journal of travels in the year 1838. London: J. Murray.

Robinson, E. and Smith, E., 1856. Biblical researches in Palestine, and in the adjacent regions. A

journal of travels in the year 1838 & 1852. London: J. Murray.

Roger, E., 1646. La Terre Saincte, ou, Description Topographique Tres-particuliere des Saincts Lieux &

de la Terre de Promission. Paris: Chez A. Bertier.

Rubin, R., 2006. One city, different views: a comparative study of three pilgrimage maps of

Jerusalem. Journal of Historical Geography, 32, 267–290.

Scholz, J.M.A., 1822. Travels in the countries between Alexandria and Paretonium, the Lebian Desert,

Siwa, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, in 1821. London: Sir Richard Philips & Co.

Schur, A.A., 2002. Letters from 1833 of ‘Hasidey Carlyne’ in Tiberias. Beit Aharon and Israel Corpus,

17 (4), 247–255.

Schur, N., 1987. Tiberias description in 1831. Ariel, 53–54, 62–66.

Schur, N., 1988. The population of Tiberias during the Ottoman period. Mituv Tveria, 6, 11–15.

Seetzen, M., 1810. A brief account of the countries adjoining the lake of Tiberias, the Jordan and the

Dead Sea. London: Meyler and Son, Abbey-Church-Yard.

Shklov, I., 1837. Israel of Shklov’s Letter from Jerusalem to Amsterdam about the earthquake in

Safed. In: A. Ya’ari, ed. Letters of Eretz Israel. Tel-Aviv: Gazit, 357–363.

Spilsbury, F.B., 1823. Picturesque scenery in the Holy Land and Syria, delineated during the campaigns

of 1799 and 1800. London: Howlett and Brimmer.

Stephens, J.L., 1839. Incidents of travel in Egypt, Arabia Petræa, and the Holy Land. London: W. and

R. Chambers.

Thomson, W.M., 1837. Syria and the Holy Land. Journal of Mr. W. M. Thomson on a visit to Safet

and Tiberias. Missionary Herald, 33 (11), 433–447.

Turner, W., 1820. Journal of a tour in the Levant. London: John Murray.

Volney, C.F., 1788. Travels through Syria and Egypt in the years 1783, 1784, and 1785. 2nd ed.

London: G. J. and J. Robinson.

Wilson, W.R., 1823. Travels in Egypt and the Holy Land. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and

Brown.

Ya’ari, A., 1976. Journies of Eretz Israel. Ramat Gan: Massada.

Zohar, M., Salamon, A., and Rubin, R., 2013. Damage patterns of past earthquakes in Israel –

preliminary evaluation of historical sources. Jerusalem: Geological Survey of Israel.

[1] PRO FO 78.316 (Beirut: Moore to Palmerstone) 2.1.1837,

9.1.1837, 2.3.1837 (enclosures 2 and 5 to Palmerstone),

17.1.1837 (Aleppo: Werry to Palmerstone); 17.1.1837

(Aleppo: Werry to Bidwell) and 1.2.1837 (Aleppo: Werry

to Ponsonby).

[2] PRO FO 78.315 (Damascus: Farrer to Palmerstone)

25.1.1837, 20.3.1837, 24.5.1837 and enclosures that are not

dated.

[3] Archives Dipl. Nantes (Turq.) Corr. Cons. (Damas)

15.1.1837 and 22.2.1837; and (Beyrouth) 28.1.1837.

[4] Archives Dept. des Bouches du Rhone (Marseille) 200.33.

[5] Archives Societe de Geographie, Paris, Corr. 1649 (Beyrouth:

Joselle to H. Joselle) 15.1.1837; (Beyrouth: Guys to

H. Joselle) 17.1.1837.

[6] Archives Abdin Palace, Cairo, Corr. 1252, vol. 254, no.

403 (Ibrahim Pasa to Sami Beg) 10.3.1837 (2.12.1252); also

extracts in Rustum (1942).

PATH no. 418, 1837.

PCB vol. 12.305.1837 and vol. 13.150.1838.

PEMS 15.2.1837 and 20.5.1837.

PJS 21.1.1837.

PMR no. 11, 322-341, 1843.

PNH vol. 2, no. 9, 134-135, 1835.

Unpublished Sources

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tiberias | definitive | ≥8 | Zohar (2017) examined textual and visual sources before and after the 1837 CE Safed Quake which was then analyzed using using Historical GIS. A table and map of Damages and Damage distributions was produced as a result of the analysis. |

| Tel Ateret aka Vadun Jacob | possible | ≥7 or ≥8 | Ottoman Mosque Earthquake -

Ellenblum et al (1998:305) described archaeoseismic evidence from Mamluk and Ottoman mosques built on the site as follows:

In the northern part of the castle, we also unearthed a Muslim mosque whose northern wall is displaced sinistrally by 0.5 m. A mikhrab (the Muslim praying apse) is well preserved in the southern wall. According to the study of the pottery, the mosque was built, destroyed, and rebuilt at least twice: the initial structure was built in the Muslim period (12th century) and later rebuilt once or twice during the Turkish Ottoman period (1517-1917). The 0.5 m displacement is observed in the northern wall of the latest building phase. The repetitive building of this site might be due to earthquakes.The latest rebuilding phase was not dated. Ellenblum et al (2015) suggested that the 30 October 1759 CE Safed Quake was responsible while Ellenblum et al (1998:305) and Marco et al (1997) entertained the possibility that the 1837 CE Safed Quake is also a possible candidate. |

| Nimrod Fortress | possible | ≥8 | As this site has not been systematically excavated, the date of the observed seismic damage is conjectural. It happened sometime after the fortress was built in the 13th century CE. However, the 1759 CE Safed and Baalbek Quakes are promising candidates, particularly the 1759 CE Safed Quake which Daeron et al (20015) suggests broke the Rachaiya Fault a mere 2.5 km. away. In addition, the Nimrod Fortress is optimally oriented to experience seismic amplification due to a Ridge Effect from fault breaks on the Rachaiya Fault. Hinzen et al (2016) examined 95 instances of arch deformations on the site and concluded that a preferred damage orientation was not present on the site overall but was present in the Gate Tower and the secret passage in the Gate Tower. Hinzen et al (2016)'s orientation results, however, may suggest the possibility that more than one earthquake damaged the site (e.g., the 30 Oct 1759 CE Safed Quake, the 25 Nov. 1759 CE Baalbek Quake, and/or the 1837 CE Safed Quake). The Earthquake Archaeological Effects Chart suggests a minimum Intensity of 8 and a Discontinuous Deformation Analysis by Kamai and Hatzor (2007) suggests a local Intensity of about 9. Attenuation relationships using postulated Magnitudes and Epicenters from Daeron et al (20015) suggest that site Intensity was between 9 and 11 for the 1759 CE Safed Quake and 7.5 and 11 for the 1759 CE Baalbek Quake. |

| Dhiban | possible | Tristram et al. (1873:135), while speculating on the discovery of the Mesha Stele in 1868 CE, suggested that the Stele was first exposed during the Safed earthquake of 1 January 1837 CE probably unaware that if an earthquake from around that time exposed the Mesha Stele, it would probably have been the 1834 CE Fellahin Revolt Earthquake. | |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Minimum PGA (g) | Likely PGA (g) | Likely Intensity1 | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safed | probable | n/a | n/a | ≥8 | Intensity Estimate is based on post quake descriptions of the Castle at Safed.

These reports indicate that the Castle suffered a major collapse which leads to a minimum Intensity of VIII (8) when using the

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart of

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224). Katz and Crouvi (2007) undertook a GIS based slope stability analysis of Safed in order to estimate current hazard due to seismically induced landslides. They used the 1759 CE Safed Quake and 1837 CE Safed Quake as calibrating events for their model. Their analysis coupled with observations of active creep within in the city suggest that a thick anthropogenic talus has created conditions ripe for slope instability. This in turn suggests that seismic damage in Safed due to the 1759 CE Safed Quake and the 1837 CE Safed Quake was largely due to landslides. The landslides in 1837 CE caused widespread destruction in the Jewish Quarter on the west slope below the Citadel in what is now called the Old City. |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Minimum PGA (g) | Likely PGA (g) | Likely Intensity1 | Comments |

| Location (with hotlink) | Status | Intensity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taninim Creek Dam | possible |

Flame structures - ~1500-~1900 CE

Marco et al (2014) observed zigzaged flame structures atop a permeable lacustrine unit wedged between

two impermeable units. They interpreted the flame structures to be a result of overpressures or liquefaction. They surmised that the liquefaction was either induced directly by seismic shaking or by loading from a