Safed

View of Safed from the NE with the Sea of Galilee in the distance

View of Safed from the NE with the Sea of Galilee in the distanceBeivushtang - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Safed | English | |

| Zefat | English | |

| Tzfat | Hebrew | צְפַת |

| Tzephath | Hebrew - Talmud | |

| Safad | Arabic | صفد |

| Seph | mentioned by Josephus in The Jewish War (II,573) | |

| Tziphoth | possibly Safed in Egyptian hieratic M.S. called ‘Travels of a Mohar’ (‘Records of the Past,’ vol. ii. p. 62) |

Safed is located on a chalky hill of the Upper Galilee and has been continuously inhabited since c. 2000 BCE - the Middle Bronze Age (Damati, Stepansky, and Barbe in Stern et al, 2008:2025-2027). Josephus fortified the site in 67 CE in preparation for an anticipated Roman invasion and it was later fortified by a host of political entities including the Crusaders, Mamelukes, and Ottomans (Damati, Stepansky, and Barbe in Stern et al, 2008:2025-2027). In the 1500s, it became a center for the mystical Jewish Kabbalah movement and contained large Muslim and Jewish communities (Wikipedia). The city was devastated by the 1837 CE Safed Earthquake and appears to have suffered during historical earthquakes suggesting a possible site effect (Ridge Effect) and geotechnical instability which, according to Katz and Crouvi (2007:59), is exacerbated by up to 10 meters of anthropogenic fill which can lead to both seismic amplification and Earthquake Induced Landslides (EILS).

Ancient Safed is located on a chalky hill in the mountainous eastern area of Upper Galilee. On the summit of the hill, 834 m above sea level, is an elongated ancient mound, c. 10 a. in area, settled from the Middle Bronze Age onward. In the Crusader and Mameluke periods, towering citadels were built on the hill. A number of medieval and Ottoman quarters, still partly preserved, extended along the slopes of the hill surrounding the citadel. The site is first mentioned by Josephus (War II, 573) as Seph, a site he fortified between Achbara and Yamnit. It is thereafter referred to in numerous Jewish and Arab sources and became the main urban center in the Galilee in the second millennium CE.

Surveys and archaeological excavations of the mound and its slopes have revealed that Safed was first settled in the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000 BCE) and has since been continuously inhabited into modern times. The site may have already been fortified in the second and first centuries BCE, possibly as one of the Hellenistic fortresses and later as one of the Hasmonean garrisons conquered by Herod during his campaign against the Jews of Galilee in 39 BCE (Josephus, War I, 238–239, 314–316; Antiq. XIV, 297–298). Josephus fortified the site in 67 CE in preparation for the anticipated Roman invasion. However, no definite architectural remains of these fortifications have been found. During the Late Roman and Byzantine periods, Safed was probably a medium-sized Jewish town, mentioned once in the Jerusalem Talmud. According to Jewish literary and epigraphic sources, a community of one of the 24 priestly families, Yakim-Pashchur (the twelfth priestly course), lived in Safed. In the Early Islamic period, a Jewish community in Safed is documented in the Cairo Geniza. In the eleventh century CE, just before the Frankish conquest, Arab sources mention the existence of a single tower, Burj el-Yatim. The earliest fortification of the site by the Franks is recorded as dating to 1101/02 CE; this fortress was handed over to the Templars in 1168. Safed was surrendered to Saladin by the Franks in 1188, and the fortress remained in Muslim hands until 1240. Safed was then returned to Frankish rule and a large citadel was built, described as the largest Crusader castle in the East; the details of its building are described in a Latin source, De Constructione Castri Saphet, dated to the year 1264 and attributed to the bishop of Marseilles, Benoît of Alignan. In 1266, the Mamelukes, under the command of Baybars, besieged the fortress, which was surrendered after a six-week siege. According to the historical sources, the Mameluke Sultan undertook reconstruction work as early as 1266–1267, building an outer fortification wall, as well as a huge round tower, 120 cubits (60 m) high and 70 cubits (35 m) in diameter, and fitted with a spiral ramp. Safed, dominated by its castle, became a provincial capital and eventually one of the largest cities in the country. During the sixteenth century, it was a world-renowned center of Jewish thought and mysticism, with a prosperous Jewish quarter on its western slope that encompassed about half the city’s total population (c. 20,000). In 1759 and 1837, earthquakes severely damaged the city, while further hardships in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, together with the development of the coastal cities, brought about an eventual decline in the city’s population and importance, a situation relieved only after the 1948 War of Independence.

Although described by numerous travelers throughout the second millennium ce, Safed’s archaeological remains and ancient buildings were first documented by European explorers and artists in the nineteenth century. A survey of the citadel conducted by the Palestine Exploration Fund produced its first detailed plan. Until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, however, no formal excavations were conducted within ancient Safed. The excavations described below were carried out mainly under the auspices of the Israel Department of Antiquities (IDA) and, since 1990, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).

The first excavations were undertaken in 1951 by M. Dothan and in 1962 by A. Druks within the confines of the citadel, below it, and to the south and southwest of the summit. In 1967 (D. Bahat), and again in 1987 (E. Damati and Y. Stepansky), Middle Bronze Age I–II and Late Bronze Age burial caves were excavated on the southern slope of Mount Canaan, 500 m east of the citadel. During the 1980s, a series of soundings was directed by Damati in different parts of the citadel, and pottery surveys of the mound and its environs were conducted on behalf of the Archaeological Survey of Israel (by R. Frankel et al.) and the IDA (archaeological survey by Y. Stepansky). In the early 1990s, an emergency survey and a salvage excavation of Middle Bronze Age cairns were carried out by Damati and Stepansky prior to the construction of the Ramat Razim and Menachem Begin quarters in the eastern part of Safed’s municipal area. In 1996, a salvage excavation was directed by Damati at the site of Khan haYehudim (Khan el-Pasha) on the southern fringes of the Jewish Quarter. A long-range project for the excavation, preservation, and reconstruction of the southern part of the citadel was initiated in 2001, directed at first by Damati and continued by H. Barbé. Preservation evaluations and architectural surveys of ancient buildings and monuments were also carried out in the Old City by the IAA Conservation Department. In 2002, a small-scale salvage excavation was conducted by Damati in the Artists’ Quarter near the Rimonim Hotel, in front of the Zawiyet Banat Hamid Mameluke mausoleum. A salvage excavation was directed by M. Cohen on the southern fringes of the Mameluke-Ottoman Quarter of Harat el-Wata (a modern neighborhood in the southern section of Safed) and a limited sounding within the compound of Machon Alta on the northwestern slope of the citadel was conducted by Stepansky

- Annotated Satellite Photo

of Safed from BibleWalks.com

- Fig. 1 - Aerial View of Safed

showing location of the fortress from Delali-Amos (2013)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location Map

Delali-Amos (2013) - Fig. 1 - Water Supply

Map of Safed and surroundings from Shivtiel et al (2022)

Figure 1

Figure 1

The supply of water to Safed and its surroundings.

used with permission from Yinon Shivtiel

Shivtiel et al (2022) - Safed in Google Earth

- Safed on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 2a -

Geological Map of Area from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2a

Geological map of the studied area (Levitte, 2001; anthropogenic material mapped in the frame of this work). The current Zefat city limits are marked by a blue solid line

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2b -

Geological Map of Safed from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2b

The core (historical) city area. The core city extended from the Citadel, westwards to the old cemetery (α). Sites of field-observed slope instability are marked by black arrows. Also shown are upslope limits of EILS area in the 1759 and 1837 earthquakes (β and γ, respectively) according to reported damage to synagogues (marked by close squares where

- Sefaradic Ari

- Banea

- Hagadol/Abuhav

- Greek pilgrimages/Ashkenazic Ari

- Karo

- Elshiech

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2c -

Geological cross section from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2c

West– East (A–A') geological cross section through the Citadel and the core city of Zefat; location is shown in a (the thickness of the anthropogenic talus is approximated).

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2 a, b, and c -

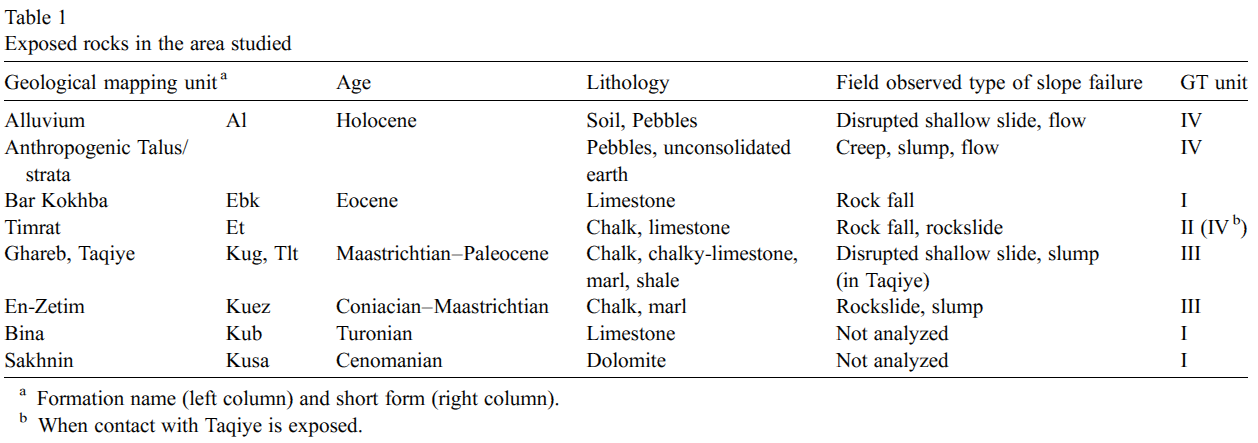

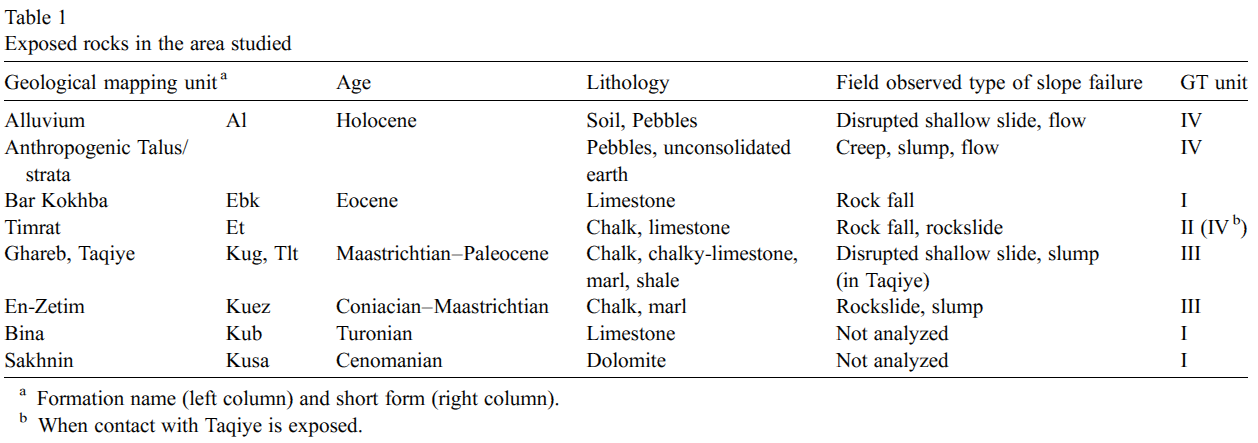

Legend from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Legend for Figure 2 a, b, and c

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 5 -

Geotechnical Map from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

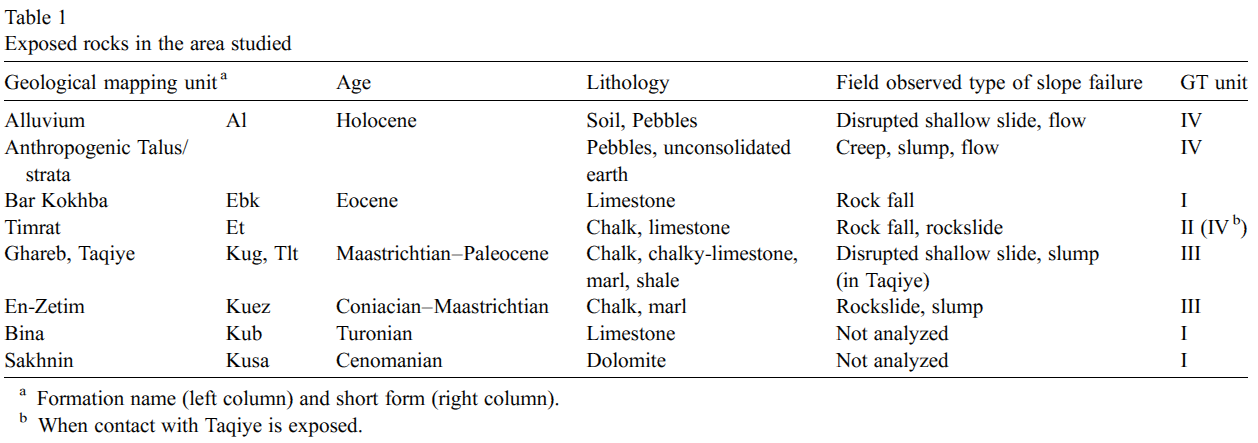

Map of the geotechnical units in the area studied (for details see Tables 1 and 2). The core (old) city extends from the citadel (marked by a triangle) westwards toward the city limits.

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 5 -

Legend from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 5 Legend

Fig. 5 Legend

Legend for Figure 5

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 6 -

Map of calculated critical acceleration from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Map of calculated critical acceleration in the study area. The core (old) city extends from the citadel (marked by a triangle) westwards toward the city limits

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 6 -

Legend from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Critical Acceleration Map Legend

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 7a -

Newmark displacement map for 1759 Safed Quake (area) from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 7a

Fig. 7a

Calculated Newmark displacement maps of two historical earthquakes used to calibrate the mechanical model, (a–b) October 1759 Mw = 6, R= 15 earthquake

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 7b -

Newmark displacement map for 1759 Safed Quake (city) from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 7b

Fig. 7b

Calculated Newmark displacement maps of two historical earthquakes used to calibrate the mechanical model, (a–b) October 1759 Mw = 6, R= 15 earthquake.

For inferred location of epicenter see text and Fig. 1. Also shown are upslope limits of EILS area in the 1759 and 1837 earthquakes ( β and γ, respectively, see Fig. 2) traced according to reported damage to synagogues (marked by numbered close squares, see Fig. 2).

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 7c -

Newmark displacement map for 1837 Safed Quake (area) from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 7c

Fig. 7c

Calculated Newmark displacement maps of two historical earthquakes used to calibrate the mechanical model, (c–d) January 1837 Mw = 7, R= 10 earthquake.

For inferred location of epicenter see text and Fig. 1. Also shown are upslope limits of EILS area in the 1759 and 1837 earthquakes ( β and γ, respectively, see Fig. 2) traced according to reported damage to synagogues (marked by numbered close squares, see Fig. 2).

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 7d -

Newmark displacement map for 1837 Safed Quake (city) from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 7d

Fig. 7d

Calculated Newmark displacement maps of two historical earthquakes used to calibrate the mechanical model, (c–d) January 1837 Mw = 7, R= 10 earthquake.

For inferred location of epicenter see text and Fig. 1. Also shown are upslope limits of EILS area in the 1759 and 1837 earthquakes ( β and γ, respectively, see Fig. 2) traced according to reported damage to synagogues (marked by numbered close squares, see Fig. 2).

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 9a -

Newmark displacement map for MW = 6 earthquake from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 9a

Fig. 9a

Examples of calculated Newmark displacement maps (EILS hazard) in scenario earthquakes.

- MW = 6

- R= 10 km, 25 km, 50 km and 100 km

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 9b -

Newmark displacement map for MW = 7 earthquake from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 9b

Fig. 9b

Examples of calculated Newmark displacement maps (EILS hazard) in scenario earthquakes.

- MW = 7

- R= 10 km, 25 km, 50 km and 100 km

Katz and Crouvi (2007)

- Plan of the Citadel

from Stern et al (2008)

Safed: Plan of the Citadel

Safed: Plan of the Citadel

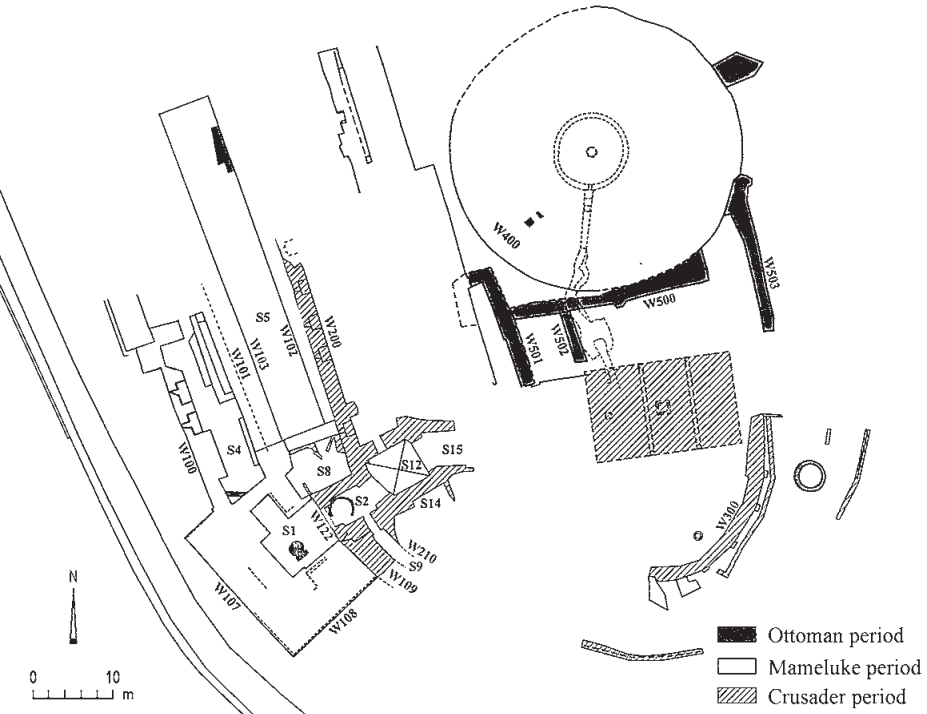

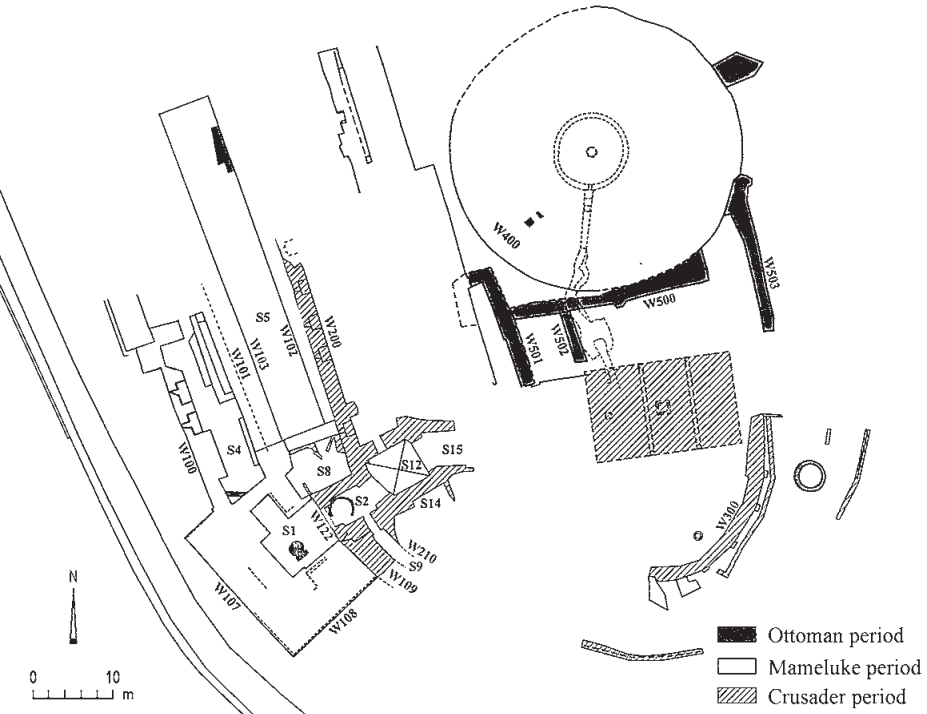

Stern et al (2008) - Fig. 1 - Plan of the

S and SW corners of the fortress from Barbé and Damati (2005)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Schematic plan of archaeological remains in the southern and southwestern sectors of the fortress.

Barbé and Damati (2005) - Plan of the Citadel

in Safed from the PEF Survey of Palestine map (1871-1877) - from Wikipedia

Kulat Safed from the 1871-77 Palestine Exploration Fund Survey of Palestine

Kulat Safed from the 1871-77 Palestine Exploration Fund Survey of Palestine

Palestine Exploration Fund - Wikipedia - Public Domain

- Pl. I - Drawing of the Castle of Safed

by Wilson in 1880 - from Huygens (1981)

Plate I

Drawing of Wilson (1880), see note 47

Note 47 - The other (Plate IV) is in the book by EW Schulz, Reise in das gelobte Land, Mülheim ad Ruhr, 1852, between p. 64 and 65. The engraving is interesting because it shows the castle up close, seen from the southwest. By contrast, the view of the fortress found in CW Wilson, Picturesque Palestine, II, London, 1880, p. 91 [= G. Ebers and H. Guthe, Palastina, 1, Stuttgart, 1882, p. 341], beautiful as it is (plate I), presents no detail of comparable value, any more than the description of Safed on pages 74 and 92-93; the engraving showing the Jewish quarter (p. 90), was reproduced by Y. Ben-Arieh (see below, n. 51), p. 228.

Huygens (1981) - Pl. I - Closeup on the Citadel of

Drawing of the Castle of Safed by Wilson in 1880 - from Huygens (1981)

Plate I Closeup

Drawing of Wilson (1880), see note 47

Note 47 - The other (Plate IV) is in the book by EW Schulz, Reise in das gelobte Land, Mülheim ad Ruhr, 1852, between p. 64 and 65. The engraving is interesting because it shows the castle up close, seen from the southwest. By contrast, the view of the fortress found in CW Wilson, Picturesque Palestine, II, London, 1880, p. 91 [= G. Ebers and H. Guthe, Palastina, 1, Stuttgart, 1882, p. 341], beautiful as it is (plate I), presents no detail of comparable value, any more than the description of Safed on pages 74 and 92-93; the engraving showing the Jewish quarter (p. 90), was reproduced by Y. Ben-Arieh (see below, n. 51), p. 228.

Huygens (1981) - Pl. III - Drawing of Safed

from the northeast by (Bartlett-) Willmore in 1851 - from Huygens (1981)

Plate III

Safed seen from the northeast, engraving by (Bartlett-) Willmore (1851), see p. 21-22.

What makes Bartlett's book important for us is that between p. 208 and p. 209 is an engraving (by A. Willmore): among the views of the castle that I know, it is one of the two that are of real interest (note 47) . It betrays enough of the romantic era, but although it singularly mistreats the perspective of the landscape, it is of all importance for a few details. The ruined fortress is there on the right on the hill (see plate iii). One notices there first, seen from the North-East, an enclosure; the visible part has eight towers, seven of which are circular. Only the eighth, the leftmost, may not be. It must be the first enclosure, because the thin remains which in the foreground are observed on the deforested hill, lower than the enclosure with the eight turns, could not be taken for those of the first enclosure. Neither the first nor the second ditch can be distinguished. Inside the fortress there are considerable remains of a distinctly square keep, well in the architectural traditions of the Templars, together with those of another square tower and a large building to the right. The dungeon is to the south, near Tiberias48. In the background, in the plain, also on the south side, we still see a large square work with two equally square towers. Between this work and the castle extends the white city of Safed. To the left of the city, on a hill overlooking the lake, there is a small tower, which was undoubtedly to ensure the connection between the castle and the city of Tiberias by means of fire signals49.

Huygens (1981) - Pl. III - Closeup on the Citadel of

Drawing of Safed from the northeast by (Bartlett-) Willmore in 1851 - from Huygens (1981)

Plate III Closeup

Safed seen from the northeast, engraving by (Bartlett-) Willmore (1851), see p. 21-22.

What makes Bartlett's book important for us is that between p. 208 and p. 209 is an engraving (by A. Willmore): among the views of the castle that I know, it is one of the two that are of real interest (note 47) . It betrays enough of the romantic era, but although it singularly mistreats the perspective of the landscape, it is of all importance for a few details. The ruined fortress is there on the right on the hill (see plate iii). One notices there first, seen from the North-East, an enclosure; the visible part has eight towers, seven of which are circular. Only the eighth, the leftmost, may not be. It must be the first enclosure, because the thin remains which in the foreground are observed on the deforested hill, lower than the enclosure with the eight turns, could not be taken for those of the first enclosure. Neither the first nor the second ditch can be distinguished. Inside the fortress there are considerable remains of a distinctly square keep, well in the architectural traditions of the Templars, together with those of another square tower and a large building to the right. The dungeon is to the south, near Tiberias48. In the background, in the plain, also on the south side, we still see a large square work with two equally square towers. Between this work and the castle extends the white city of Safed. To the left of the city, on a hill overlooking the lake, there is a small tower, which was undoubtedly to ensure the connection between the castle and the city of Tiberias by means of fire signals49.

Huygens (1981) - Pl. IV - Drawing of Safed

from the southwest by Schulz in 1852 - from Huygens (1981)

Plate IV

Safed seen from the southwest, engraving by Schulz (1852), see note 47.

Note 47 - The other (Plate IV) is in the book by EW Schulz, Reise in das gelobte Land, Mülheim ad Ruhr, 1852, between p. 64 and 65. The engraving is interesting because it shows the castle up close, seen from the southwest. By contrast, the view of the fortress found in CW Wilson, Picturesque Palestine, II, London, 1880, p. 91 [= G. Ebers and H. Guthe, Palastina, 1, Stuttgart, 1882, p. 341], beautiful as it is (plate I), presents no detail of comparable value, any more than the description of Safed on pages 74 and 92-93; the engraving showing the Jewish quarter (p. 90), was reproduced by Y. Ben-Arieh (see below, n. 51), p. 228.

Huygens (1981)

- Aerial Photo of the Ruins at the Citadel in Safed

from BibleWalks.com

Aerial View of the Citadel in Safed showing the SW side of the hill showing main

visible fortifications, including the south gate. The lower section of the gate and the upper section on the

summit are Mamluke ruins, while the middle range are walls from the Crusaders period.

Aerial View of the Citadel in Safed showing the SW side of the hill showing main

visible fortifications, including the south gate. The lower section of the gate and the upper section on the

summit are Mamluke ruins, while the middle range are walls from the Crusaders period.

(click on photo to open up a high resolution magnifiable image)

used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Link to YouTube Video of the Castle Area from BibleWalks.com

- Photo of the Ruins at the Citadel in Safed

as of 2008 - from Wikipedia

Safed Citadel in 2008

Safed Citadel in 2008

Almog - Wikipedia - Public Domain - Pl. II - 1947 photo of a round tower

on the Citadel in Safed - from Huygens (1981)

Plate II

Remains of a round tower embedded in a tower of Daher el Omar, see note 41

Note 41 - See plate II (remains of a round tower embedded in a tower of Daher el Omar. Northwestern part of the hill, photo taken August 7, 1947. Photo Israeli Department of Antiquities and Museums in Jerusalem).

JW: Note broken "corner" in the center of the photo aligned with a joint in the encasing tower.

Huygens (1981) - Fig. 7 - Deformed Ottoman Arch

on the Citadel in Safed - from Delali-Amos (2013)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Wall 2 from the Mamluk period below the vault from the Ottoman period, looking north.

JW: Note distorted arch and protruding voussoir

Delali-Amos (2013) - Corridor in the Castle at Safed

showing fractured stones and through-going joints - from BibleWalks.com

Corridor in the Castle at Safed showing fractured stones and through-going joints.

Corridor in the Castle at Safed showing fractured stones and through-going joints.

(click on photo to open up a high resolution magnifiable image)

used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Vault Damage in the Tunnels near the

home of Aharon Botzer in the Old City (Jewish Quarter) in Safed

Vault Damage in the Tunnels near the home of Aharon Botzer.

The damage repair traverses where the lightbulb is.

According to Aharon Botzer, this displacement occurred during the 1837 CE earthquake.

Vault Damage in the Tunnels near the home of Aharon Botzer.

The damage repair traverses where the lightbulb is.

According to Aharon Botzer, this displacement occurred during the 1837 CE earthquake.

Photo by Jefferson Williams on 18 May 2023

Chronology is well established and is based on historical reports some of which are listed below:

| Source | Report | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Letter from the French Consul in Saida | Safed and Nablus have been completely ruined and overthrown |

|

| Letter written by Archbishop of Saida Boutros Jalfaq | struck especially in Safed in Galileeand Safad, 2000 dead, but the surrounding countryside is unscathed |

|

| Letters written by Dr. Patrick Russell | totally destroyed, together with the greater part of the inhabitants |

|

| La Gazette de France 1760 | overthrew the City of Safetand Tripoli in Syria is no more than a heap of ruins as are Saphet, ... |

Chronology is well established and is based on historical reports some of which are listed below:

| Source | Report | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Article in the Missionary Herald by William McClure Thomson | The first day of this year (1837 CE) will be long remembered as the anniversary of one of the most violent and destructive earthquakes which this country has ever experienced |

|

| The Times (of London) | A LIST OF TOWNS ETC., DESTROYED OR INJURED IN SYRIA BY THE EARTHQUAKE ON THE 1st OF JANUARY |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Safed |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Safed |

|

|

|

Jewish Quarter of Safed |

|

|

|

Jewish Quarter of Safed |

|

|

|

|

||

| Collapse | The Castle |

|

|

| Landslide | Jewish Quarter on the western slope |

|

|

| Widespread Casualties |

|

||

| Heavy Damage in Safed |

|

||

| Aftershocks |

|

||

| Rebuilding |

|

||

| Some parts of town spared | the Muhammedan quarter, The southern quarter |

|

- Fig. 2a -

Geological Map of Area from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2a

Geological map of the studied area (Levitte, 2001; anthropogenic material mapped in the frame of this work). The current Zefat city limits are marked by a blue solid line

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2b -

Geological Map of Safed from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2b

The core (historical) city area. The core city extended from the Citadel, westwards to the old cemetery (α). Sites of field-observed slope instability are marked by black arrows. Also shown are upslope limits of EILS area in the 1759 and 1837 earthquakes (β and γ, respectively) according to reported damage to synagogues (marked by close squares where

- Sefaradic Ari

- Banea

- Hagadol/Abuhav

- Greek pilgrimages/Ashkenazic Ari

- Karo

- Elshiech

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2c -

Geological cross section from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2c

West– East (A–A') geological cross section through the Citadel and the core city of Zefat; location is shown in a (the thickness of the anthropogenic talus is approximated).

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2 a, b, and c -

Legend from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Legend for Figure 2 a, b, and c

Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Katz and Crouvi (2007:65) report that

the core city was severely damagedin the earthquakes of 1759 CE

with about 150 fatalities, most of them in the earlier shock (Schiller, 2002; Ya'ari, 1943). They further report that

the majority of the damage occurred in the downhill (western) parts of the core city (Fig. 2b), apparently due to landslides (Yizrael, 2002a). They added that

the synagogues of the Sefaradic Ari and Banea that were damaged in the 1759 earthquake (probably the first) mark the upper landslide boundary (β in Fig. 2b), while the more eastern ones, the Greek pilgrimage and Hagadol (the big) synagogues, were not damaged (Yizrael, 2002a).

- Ruins from the Abuhav Synagogue from zissil.com

Ruins from original Abuhav structure

Ruins from original Abuhav structure

zissil.com

zissil.com reports that all existing synagogues in Safed were destroyed in 1759 CE except for the Alsheich synagogue. zissil.com supplies the following about damage to the Abuhav Synagogue in 1759 CE:

Some historians believe that the original Abuhav Synagogue was built in the 15th century near the base of the mountain, above the cemetery and was rebuilt in its present site, on Abuhav Street after the 1759 earthquake. Others say the original synagogue existed in its present site and was rebuilt in the same location after the earthquake. Both versions relate that the southern wall which held the Ark of the Torah scrolls did not collapse after the 1759 earthquake.

One of the Torah scrolls in the Ark had been written in the 15th century by Rabbi Yitzchak Abuhav. According to Safed legend, Rabbi Abuhav warned that the Torah scroll was not be removed from the Ark other than ritual Torah-reading times. After the 1759 earthquake, ten men immersed in a mikva -- ritual bath -- so as to remove the Torah scroll and place it in a safe place as the synagogue was rebuilt. They succeeded in moving the scroll to safer quarters but within a year, all ten men died.

- Fig. 2a -

Geological Map of Area from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2a

Geological map of the studied area (Levitte, 2001; anthropogenic material mapped in the frame of this work). The current Zefat city limits are marked by a blue solid line

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2b -

Geological Map of Safed from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2b

The core (historical) city area. The core city extended from the Citadel, westwards to the old cemetery (α). Sites of field-observed slope instability are marked by black arrows. Also shown are upslope limits of EILS area in the 1759 and 1837 earthquakes (β and γ, respectively) according to reported damage to synagogues (marked by close squares where

- Sefaradic Ari

- Banea

- Hagadol/Abuhav

- Greek pilgrimages/Ashkenazic Ari

- Karo

- Elshiech

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2c -

Geological cross section from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2c

West– East (A–A') geological cross section through the Citadel and the core city of Zefat; location is shown in a (the thickness of the anthropogenic talus is approximated).

Katz and Crouvi (2007) - Fig. 2 a, b, and c -

Legend from Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Legend for Figure 2 a, b, and c

Katz and Crouvi (2007)

Katz Crouvi (2007:65) report that this earthquake "caused severe damage to the core city of Zefat (Vered and Striem, 1976) with more than 1000 lives lost (Ben-Horin, 1952)". Katz Crouvi (2007:65) added the following:

An eyewitness of the destruction reported rents and cracks in the rocks and earth of the hill and related that the uppermost row of houses fell on the next one below, which then fell upon a third (Thomson, 1873). Wachs and Levitte (1981), considered the above a description of landslides morphology and dynamics. The landslide extent of this earthquake was apparently larger than that of 1759 (γ in Fig. 2b). The synagogues of the Sefaradic Ari and Banea were damaged again in the 1837 earthquake, as were the more eastern Ashkenazic Ari and Abuhav ones built in the locations of the Greek pilgrimage and Hagadol synagogues that were not damaged in the 1759 shocks (Yizrael, 2002a). The synagogue of Yosef Karo was also damaged and the Elshiech synagogue was spared. The part of the core city situated on the hill backbone, south of the Citadel (Fig. 2a), was reported to have suffered only minor damage (i.e., no landslides) during this earthquake (D. Wachs, unpublished).

The downhill (western) damage in the 1837 earthquake was probably further down from the current western limit of the core city (Fig. 2b). Yizrael (2002a), stated that customarily, the main spiritual center (Sefaradic Ari synagogue) would not have been built on the outskirts of the city, on the border of the cemetery (α in Fig. 2b); thus it is probable that in the past the city extended further down beyond the current cemetery area. Yizrael (2002b), showed that there are no pre-1837 tombs in the upper cemetery area (bordering the current western city limit). He suggested that the most eastern pre-1837 tombs bordered the western city limit of that time. This builtup part, now at the upper cemetery area, was damaged during the 1759 earthquake, rebuilt and damaged again in the 1837 shock and never rebuilt again.

- from Huygens (1981:18-20)

EUGENE ROGER, The Holy Land or very special topographical description of the holy places, and of the Land of Promise, Paris, 1646, book I, p. 66-67: It is now only a town, fortified with a castle, whose lower walls bear witness to great antiquity... Since the Emir Fechrreddin made himself master of Galilee, about l n the year one thousand six hundred and eighth, he had this castle restored for the residence of Emir Ali, his eldest son, who fortified it, and put this city back on its feet. But in the year one thousand six hundred and thirty three he was defeated, wanting to resist an army of forty thousand men of the Great Lord led by the Bacha of Damascus... Since that time it has been under the domination of the Bacha of Damascus, who there maintains a Mousalem, who commands this fortress, in which there are two companies of Yanissaries.

O. DAPPER43 , Naukeurige Beschrijving vangantsch Syria, in Palestijn, of Heilige Lant, Amsterdam, 1677, p. 131-132: The castle is large, roughly oval in shape, and one of the finest and strongest seen among ancient castles. The works or fortresses were not built in a modern way, nor are they regular, but they would still be good and solid, if they were all still intact. There are still magnificent and well intact remains. One climbs to the castle by wide vaulted paths which in several places open onto stores, chambers, halls and similar rooms. There is still a large octagonal hall, which receives its light only through a dome or cupola: this one is round, entirely open and without any other roof. This room could have once been the church or the chapel of the castle. On the other side of the castle, towards the north, there were also beautiful and tall buildings, but which nowadays are destroyed or dilapidated. These were covered, to the north, by a high square tower, of which only one of the four walls remains, which from its foundations to the top is still straight and solid. Below, at the foot of the mountain, to the east and west or near the enclosure, there are water sources and in the city there are many cisterns.

RICHARD POCOCKE, A Description of the East and some other Countries, vol. first part, London, 1745, p. 76: ... its situation is very high, and commands the whole country round; on the very summit of the hill are great ruins of a very strong old castle, particularly of two fine large round towers that belonged to it.

JOHAN AEGIDIUS VAN EGMOND VAN DER NYENBURG and JOHANNES HEYMAN, Reizen door een gedeelte van Europa, klein Asien, verscheide Eilanden van de Archipel, Syrian, Palestina of het H. Land, Aegypten, den Berg Sinai, enz. (in two parts, 1, Leiden, 1757, and) ii, Leiden, 1758, p. 43-45 (translation):... (the castle) which was the most beautiful thing to see here. Although it is so dilapidated nowadays that one can hardly recognize its primitive form, it must be considered as one of the oldest surviving antiquities in these countries. The said castle is on the top of the mountain, around which the city was built; once it was a mighty fortress, as the many remaining pieces still clearly indicate. The periphery would have been more than a thousand and a half.

Now it is like this: imagine a high mountain, the summit of which is crowned by a round castle with incredibly thick walls, and a corridor or vaulted passage in the middle of the wall and rising from bottom to top in the manner of a spiral . I counted twenty of my paces there, for the thickness of the wall was twenty paces including the corridor or vaulted passage, and all was of hewn stone, of which there were some which numbered no less than eight or nine spannen 45 length. At the time, the interior of this castle was still more or less intact; it was a hexagonal room with six arches, which received its light from above the terrace, where there was an orifice. Near this castle we also discovered the ruins or destroyed remains of several cisterns, towers and other buildings, but which can hardly be recognized nowadays; there is also still a well with water, although at the time it was filled with stones. In addition, this castle was once surrounded by great works, as it results from two masonry ditches, several walls, bastions, towers, etc., all very solidly and strongly built, and around these ditches, namely a little lower , there were still heavy buildings, in which there were corridors or vaulted passages, as around the castle itself, so that one can rightly wonder how one could seize, in these times far away, from such a powerful fortress... But what really deserves the most attention here is a large freestone building, erected in the shape of a dome and which once seems to have served as a Temple. The stones, for the most part white, are of an appalling size and thickness: some are found among them which are twelve long and five spannen thick . Inside there are niches everywhere in the walls to place idols as well as small adjoining rooms. All around there is also a vaulted gallery, of very solid and strong construction. We climbed on this dome or cupola, where we still discovered some vestiges of another building which must have been on it, and from this point we had the most beautiful panorama that one could wish...

d. L. BURCKHARDT, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land, London, 1822 (the visit to Safed dates from June 21, 1812), p. 317: ... it is a neatly built town, situated round a hill, on the top of which is a castle of Saracen structure. The castle appears to have undergone a thorough repair in the course of the last century, it has a good wall, and is surrounded by a broad ditch. It commands an extensive view over the country towards Akka, and in clear weather the sea is visible from it. There is another but smaller castle, of modern date, with half ruined walls, at the foot of the hill.

WILLIAM JOWETT, Christian Researches in Syria and the Holy Land, London, 1825 (the visit to Safed dates from November 13 and 14, 1823), p. 183-184: We next ascended the castle-hill; and here, whatever disgust we had conceived from the narrowness and dirtiness of the streets and houses of Safet, all was obliterated by the magnificent prospect from this spot. Although the castle is in ruins, yet part of it still affords a residence to the Governor: the extend of the walls, the perfect condition of some parts of them, and the high glittering towers visible to all the region round about, show that this must have been a spot often contested in war.

43 The Dutchman Dapper was only a conscientious compiler, who without traveling himself

composed many descriptions of distant countries; see Van der Aa, Biographisch Woordenboek,

iv, 1859, p. 18-19. The first part of what he says about Safed is based on Roger's data.

The passage which I reproduce in translation will be largely confirmed by (Van Egmond and)

Heyman; but it differs from their account in some important details which must have been

taken from a source which has remained unknown to me. Although I have reviewed all the

authors named by Dapper in his introduction, I have not been able to discover the story

he used to describe the ruins of Safed. I must therefore quote my compatriot instead of

his source, wishing the best of luck to my readers.

44 I also thought I had to translate the following description, most of my readers not being,

I suppose, familiar with the Dutch language. Van Egmond and Heyman recorded their impressions

in letters that were published after their deaths by JW Heyman. In the non-paginated preface

(1, p. 12), he mentions that his uncle traveled from 1700 to 1709, Van Egmond from 1720-1723.

To avoid repetitions, the editor took Heyman's letters as the basis of his book, completing

the story of one with that of the other. But it is impossible to say whether the description

of the castle that we are about to read is by Heyman's hand or that of Van Egmond. Let us

therefore retain the first quarter of the eighteenth century as the date.

45 The span was a measure that indicates the distance between the tips of the thumb

and the little finger, that is to say a good twenty centimeters.

- from Huygens (1981:20-32)

ROBINSON and SMITH, Biblical Researches in Palestine. . . A journal of Travels in the years 1838 and 1852, second edition, London, 1856, vol. ii, p. 419-422 (the visit to Safed dates from 1838): Crowning the rocky summit, above the whole town, was the extensive Gothic castle, a remnant of the times of the Crusades, forming a most conspicuous object at a great distance in every direction , except towards the north. Thought already partially in ruins before the earthquake, it was nevertheless sufficiently in repair to be the official residence of the Mutesellim; and on a former visit to Safed, my companion had paid his respects to that officer within its walls. The fortress is described as having been strong and imposing, with two fine large round towers46; it was surrounded by a wall lower down, with a broad trench... (p. 423) Nearly eighteen months had now elapsed since the calamity, when we visited Safed... The castle remained in the same state in which it had been left by the earthquake, a shapeless heap of ruins; so shapeless indeed, that it was difficult to make out its original form.

WILLIAM HENRY BARTLETT, Footsteps of Our Lord and His Apostles in Syria, Greece and Italy, London, 1851, p. 209-210 (summarizes the previous notice). What makes Bartlett's book important for us is that between p. 208 and p. 209 is an engraving (by A. Willmore): among the views of the castle that I know, it is one of the two that are of real interest47. It betrays enough of the romantic era, but although it singularly mistreats the perspective of the landscape, it is of all importance for a few details. The ruined fortress is there on the right on the hill (see plate iii). One notices there first, seen from the North-East, an enclosure; the visible part has eight towers, seven of which are circular. Only the eighth, the leftmost, may not be. It must be the first enclosure, because the thin remains which in the foreground are observed on the deforested hill, lower than the enclosure with the eight turns, could not be taken for those of the first enclosure. Neither the first nor the second ditch can be distinguished. Inside the fortress there are considerable remains of a distinctly square keep, well in the architectural traditions of the Templars, together with those of another square tower and a large building to the right. The dungeon is to the south, near Tiberias48. In the background, in the plain, also on the south side, we still see a large square work with two equally square towers. Between this work and the castle extends the white city of Safed. To the left of the city, on a hill overlooking the lake, there is a small tower, which was undoubtedly to ensure the connection between the castle and the city of Tiberias by means of fire signals49.

CWM VAN DE VELDE, Narrative50 of a journey through Syria and Palestine in 1851 and 1852, t. if, London, 1854, p. 408-409: ... the castle min on the top of the mountain, from which one enjoys that noble panorama of Southern Galilee and the Sea of Gennesareth... Should you ever come to Safed, neglect not, above garlic things, to climb to the castle; the indescribably magnificent views from that point will amply repay you for your trouble.

E. ISAMBERT, Descriptive itinerary; historical and archaeological history of the Orient, Paris (Guides-Joanne), 1861, p. 701: Safed is today a city of 4000 inhabitants. approximately, including a third of the Jews, originating from Poland or Russia ...51 The most interesting object of Safed is the old citadel, which crowns the summit of the N. This fortress was formed of a vast oval enclosure and a large central quadrangular building, on the top of which one can still climb through the rubble. Everything was turned upside down, shaken or cracked by the earthquake of 1837.

Until then, the moutesselim of the region had made his residence there. Today it is no more than a picturesque ruin. One notices there the opening of underground passages which seem to have a great depth. From the top of the citadel, we discover an immense panorama, which alone deserves to attract the traveler to this place. To the SE one sees developing at its feet the majestic sheet of water from Lake Tiberias, blue as the eastern sky, whose sudden appearance charms the eyes of the traveler tired of the arid and parched aspect of the region. ...

In 1863, Rey inaugurated the era of Safed's more conscientious investigations. Unfortunately, it is already too late: he found there only what earthquakes and men had left of the Frankish castle, already ruined before, but restored or rather partially rebuilt by the Arabs. The great specialist in Crusader castles therefore left us with an impression rather than an exact description of what he found. Nevertheless, as we will see, it still contains many useful elements:

The citadel is roughly oval in shape. It is four hundred meters long, ninety-five wide. Its walls, still about ten meters high, form a double enclosure separated by a ditch carved into the living rock. The facing stones are of very large apparatus and cut with bosses. In 1863, one saw on the central reserve of this fortress the remainders of two considerable buildings; the first was a square dungeon and the other seems to have been a large dwelling... Arab chronicles speak of a very deep well which supplied the garrison with water. Outside the current city are still the remains of two advanced works of the castle. They were also built in huge boss-hewn blocks. But, like those of the castle, these ruins, dismembered every day by the inhabitants, who have made veritable quarries of them, will soon have disappeared. In 1870, mm. Mieulet and Derrien found another recognizable oblong tower, forming one of the flanks of the work located to the south, in front of the citadel, on the other side of the pass, covered with gardens, where the road from Safed to Tiberias52.Twelve years after Rey, on November 14 and 15, 1875, the indefatigable Victor Guérin also went to Safed:

Safed's mountain peak sits 818 meters above the Mediterranean; it is crowned by the ruins of a large elliptical enclosure, the entrance to which is towards the south and surrounded by a ditch, partly dug in the living rock and three-quarters filled in. This enclosure, still called today el-Kala'h, was flanked by about ten towers, which lost, as well as itself, their coating of cut stones. All that remains is the interior blockage. Inside reigns a second ditch, then beyond the castle itself offers nothing more than a confused mass of rubble; it was flanked by towers at the corners and was provided with large and deep cisterns. It is being destroyed day by day, and it is, like the outer enclosure, a veritable quarry, from which the inhabitants of the city continually extract ready-made materials to build new houses. A powerful isolated tower or dungeon, circular in shape, measuring 34 meters in diameter, dominated the castle, which itself dominated the whole city: there are still some lower foundations arranged in a slope on the outside and composed of regular blocks, arranged with many care. Inside we notice the remains of a vaulted gallery, built with similar blocks. The horizon which one enjoys from the top of this dungeon, three-quarters razed as it is, is incomparable in extent and beauty. You can see almost the whole of Upper and Lower Galilee, and a vast expanse of the Transjordan countries, beyond the Houleh and Tiberias lakes, which unfold at your feet. to the northeast and southeast, by two other, much smaller fortresses of more recent times, which are also falling into ruin.However imperfect the data transmitted by Rey and Guérin may be, they agree quite well and their contradictions seem to me only apparent. Guérin speaks of a circular dungeon, Rey found it square. According to Rey, the advanced works were built like the castle in enormous blocks cut with bosses, therefore of Frankish construction, according to Guérin they were of more recent times, therefore of Arab construction. As for these advanced works, even without knowing the observation of Rey, one would know by their very positions that they were indeed of Frankish origin, since they commanded, to the south-east, the road to Tiberias and the approach to the castle, to the north-east the road from Damascus to the sea: this last work was therefore on the road from the castle to the "Ford of Jacob", to the north-east of Safed, where the Chastellet commanded the road from Damascus to the point where it crosses the Jordan. Now we know that in the eighteenth and eighteenth centuries the Arab princes in revolt against the Turkish authority made important repairs to the castle (see plate it); they were certainly not the first to do them and it is obvious that the advanced works were also restored. This state of affairs also appears in the (too) brief notice of the castle that we owe to the English lieutenant(s) (Kitchener and) Conder in the Survey of Western Palestine 54 . It reads: “This was originally a Crusading castle, but of that there remains but little. Vaults and entrances to cisterns still show Crusading work, but the principal remains are those of the castle that Dhâher el 'Amr built here at the time that he defied the Turkish Government, and governed this part of the country by force. Excavation might show Crusading remains hidden beneath the modern ruins... A vault... large vaults... (see below)... The rest of the remains of the castle are of small rubble masonry faced with well-dressed stones of small size, and are the work of Dhâher el 'Amr”. In this same Survey there is a meritorious but quite insufficient plan, which bears the legend: "Crusading and Saracenic Remains" (between p. 248 and p. 249), but which establishes no distinction between these two sorts of ruins. This inevitably leads to the same conclusion as all the notices quoted a little above, namely that towards the end of the axis century one could hardly distinguish the authentically Frankish constructions any more. As for the plan itself, it only indicates a single enclosure that has largely disappeared, which by its position must have been the first. On both sides of this enclosure is a hatching, which could represent the ditches. In the middle of the plan is a part of the fortress higher than the rest; in the southeast corner of this part are the remains of walls, probably belonging to the dungeon, which thus must have dominated the entrance to the castle (to the south in the first enclosure). The sketch of these remains on the plan explains the contradiction pointed out between Rey and Guérin: they can just as easily be interpreted as the remains of a circular tower as of a square tower. Let us not forget, moreover, that our observers found themselves in front of and among ruins, which they had to interpret under primitive circumstances. As for the diameter, it seems quite surprising that Rey, who nevertheless speaks of a "considerable" keep, did not realize, after having visited, examined and drawn so many castles, its exceptional dimensions. Because indeed the diameter of 34 m, mentioned by Guérin (including the thickness of the walls?) would make it the largest known tower of the Middle Ages55. Moreover, there is nothing to judge how exactly Guérin established this diameter, where he was when measuring it and what exactly he was measuring. These uncertainties, added to the implausibility of his observation, incline me not to retain this one. As for the shape of the dungeon, I also lean towards Rey's opinion, which is confirmed by Bartlett's engraving. Even if the keep had not been rebuilt on the foundations of the first period (see below), a square keep did not seem excluded in 1240. Let us not forget that in the great fortresses built by the Order of the Temple: Tortose (Tartous), Chastel-Blanc (Safita), Chastel-Pèlerin (Athlit), the number of square towers so far dominates that of the circular constructions, that it would be truly astonishing that, in a castle which was to present so many characteristics in common with them, the Order would no longer have followed the same principles of fortification. The text of De constructione (lines 182-184) speaks moreover of (the altitudo, of the spissitudo and of) the latitude of the towers. As nothing authorizes to translate this word by “diameter”, I do not see what it could indicate if it is not a square or oblong tower.

As for the dimensions of the castle, the measurements are indicated, in the Latin text, in cannae. Paul Deschamps, considering as the author of text the Bishop of Marseille Benoît d'Alignan himself, who is the hero, saw in it the Provençal cane, a measurement of 1.956 m. But even if the author had really been a Provençal, which nothing indicates, he must have obtained his data in the Holy Land, most probably at the castle itself, where they will undoubtedly have been expressed in these canes which were of use there. Nothing proves that it was the Provençal cane. Joshua Prawer, in his History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, counts by Cypriot canes (approximately 2.20 m) 56 . He does not state his reasons for doing so, but these must be based on the multiple relationships between the Holy Land of a century and the neighboring island governed by the Lusignans. I believe I can confirm the accuracy of his point of view. Rey and Guérin speak of the fortress as affecting a roughly oval shape which according to Rey was four hundred meters long by ninety-five wide. The explorer may have made a mistake in evaluating these measurements. However, the fact that he speaks of 95 m and not approximately 100 m suggests that he calculated with precision. How? This is again a question that will not receive an answer, but the indication itself seems to be done dutifully. An ellipse can be constructed. We give it an axis 400 m long, another 95 m long, and we calculate the periphery of the resulting diamond. We then obtain a periphery of 4 x 205.5 m = 822 m. Based on the dimensions given by Rey, the periphery of the castle cannot therefore have been less than this number. If we construct the ellipse exactly to scale and then measure its periphery, we find approximately 840 m. According to the Latin text (lines 176 and 178) the periphery of the first enclosure was 375 cannae. The 822-840 m therefore representing 375 cannae, it is necessary to deal with Cypriot canes, which give a periphery of 375 x 2.20 m = 825 m. But our ellipse was necessarily a perfect ellipse, while the castle was only elliptical, which leaves a certain margin. I repeat further that we can no longer control Rey's figures or even affirm that those transmitted in the Latin text, assuming that they have not been corrupted, are already not more or less (in)accurate estimates . But while emphasizing these uncertainties, I believe I have established a point of support. If now we consider one last time the plan of the Survey of Western Palestine, we see that the ratio between the length of the fortress and its width is only about 2 / 2: 1 instead of 4: 1 (Rey) . For my part, I believe I should stick to Rey's indications by considering the Survey 's ellipse as too short and too wide. As for the second enclosure, the plan shows no trace of it. Only one tower (barlong) is drawn as completely recognizable, to the west of the entrance to the castle, to the south-west in the first enclosure; three other towers (circular these) are indicated in dotted line N-NO and a another, also circular and dotted, to the NE. These towers are at about the same distances from each other, that is, still according to the plan, a little more than 40 m. If there is nothing to doubt these indications, it should all the same be underlined that nothing allows us to know whether we are dealing with towers of Frankish construction, or of Arab construction or rehandling.

Now, let's try to summarize all these heterogeneous and often painfully imprecise data (the Latin text, let's remember, was composed, and then transcribed, by men who apparently knew nothing about military architecture) . As in Tartous, Safita and Athlit, fortresses also belonging to the Temple, there were two enclosures. The first was elliptical in shape (Dapper, Rey, Guérin, Isambert, Survey) like that of Safita, certainly not round (Heyman). Its periphery was 375 Cypriot canes, or some 825 m (against approximately 700 m for the Crac des Chevaliers). As in Tartous, there were two ditches partly dug in the living rock (Rey, Guérin); the first preceded the first enclosure, probably crossed by a causeway leading to the only entrance, which was to the south (Guérin). The other ditch reigned within the fortress. In 1745, Pococke reported only two "fine large round towers", an indication that Robinson would take up again in 1838; in 1851, the engraving of Bartlett-Willmore indicates eight towers in the first enclosure, seven of which at least are circular, in 1852, that of Schulz only shows a section of wall belonging to a single tower; in 1875, Guérin speaks of "about ten" towers without specifying their shape, and in 1881 the plan of the Survey shows only one (barlong) as completely recognizable as well as the traces of four others, circular ones. As for the seven towers mentioned in the Latin text, we will talk about them later in connection with the second enclosure. The first enclosure was 10 rods high (22 m); as in Safita (and elsewhere), the wall was doubtless lined with an embankment. I apply these data to the first enclosure: the Latin text (lines 175-176) speaks only of antemuralibus et scamis, que habent in altitudine X cannas et in circuitu CCCLXXV. Now, if these words leave no doubt as to their interpretation, it seems that they are of a nature to put us on guard against the terminology of the author. It is the second gap which must have been the deepest and the widest: . .fossalis, que habent in profundo rugis VII cannas (15.40 m) and VI (13.20 m) in lato (lines 173-174). The efforts in this field of which we were capable then, can still be best observed at the Château de Saone (Qalaat Sahyoun or Salahadin), where the ditch, entirely dug in the rock, is 130 meters long, 20 meters wide and 28 meters depth57. The second enclosure formed reduced. The castle properly speaking” (Guérin) was, according to this same traveler, flanked by towers at the angles; its walls had a height of 20 canes or 44 m (lines 174-175) and at the top the thickness of a cane and a half or 3.30 m58. In my opinion, the 22 m height of the first enclosure was counted above the edge of the first ditch, but I have no doubt that the 44 m of the walls of the second enclosure included the 15.40 m depth of the second ditch (which must therefore have had a masonry glacis as one always observes in Safita)59: these walls then dominated the 28.60 m ditch and the first 6.60 m enclosure, a difference which seems to have eliminated the angles dead. Dapper's source speaks of wide arched paths leading to the castle and opening into stores, chambers, halls, etc. Heyman and Masterman (note 54) also speak of a corridor or vaulted passage leading up to the castle: this passage was made in the wall, which was not less thick than twenty man's paces, including the passage described. It can hardly be anything other than a ramp like there is still one at the Crac des Chevaliers (cf. the text quoted p. 7, line 22). In 1863 Rey noted that "the" walls were still about ten meters high. Despite Guérin, it seems that the keep, which to the south (Bartlett, Schulz, Survey) dominated the entrance to the castle (Survey), was square (Bartlett, Schulz, Rey). This keep could well be essentially that of the first castle built in the twelfth century. When in 1218 al-Mu'azzam had the fortress dismantled, it is likely that the keep was not completely demolished, which would have involved too great a cost. The keep would therefore have been repaired from 1240 (because, if as the in dist: “chastel abatuz est demi refez”)60 and the round towers of the first enclosure would have been raised then. Bartlett reports yet another square tower, Schulz two (or three), Dapper speaks of only one square tower, which he places north of the fortress. One could wonder if the immense building with a diameter of 34 m that Guérin interprets as the keep, was not rather identical to another considerable construction, pointed out by Heyman, Bartlett, Rey and Isambert (“a large central building of quadrangular”) and which Rey very likely considers as a large dwelling. Dapper still speaks of a large octagonal room, provided with a dome, perhaps the chapel, Heyman saw one which was hexagonal, without it being possible to affirm that they speak of the same room. There were important underground passages (croie) and vaulted galleries, indicated by Heyman, Guérin and Isambert; compare also what we read in the notice of the Suroty of Western Palestine (p. 249): “A vault that runs in a circular direction round the top of the castle shows good Crusading masonry... Underneath this there are large vaults, at present inaccessible...» The seven towers mentioned in the Latin text (182-4) must be those of the second enclosure, perhaps including the dungeon: their dimensions do not allow us to apply to the first enclosure the measurements transmitted by our text. Guérin speaks of "corner towers", but that does not mean that there were only four. These towers had 22 (xxit) canes or 48.40 m in height (at the 12 (mi) canes of the manuscript P an x is obviously missing), 10 canes or 22 m wide and at the top 2 canes or 4.40 m d 'thickness. These towers were therefore 4.40 m higher than the wall of the second enclosure; they dominated the first enclosure by 11 m, and the second ditch by 33 m. From such cyclopean towers, which were so many forts almost as imposing as the keep, there must have emanated an impression of power capable of striking the imagination of contemporaries as much as they strike ours when we realize that they surpassed everything what remains to us today: Sahyoun, Marqab, Crac and Tartous, Cursat and Kerak, Nemroud, Safita, whose keep is 31 m high and 18 m wide, the ruins of Athlit, where one of the two large square towers still raise a section of high wall of some 35 m - and so on. The testimonies full of admiration of medieval travelers61 prove, moreover, that the masses of the castle were most imposing: occupied as the fortress was by the Arab forces, they could probably only contemplate it from quite a distance, but they were all struck by it, two of them even more than they had been by any other castle they had seen.

Like all the castles built by the Order of the Temple, that of Safed was in huge blocks (Heyman, Rey); Rey further mentions that the facing stones were of very large apparatus and cut into bosses. Naturally the castle was equipped with large cisterns62; the latin text (lines 230-231) also indicates windmills inside the castle63 . Two advanced works (Burckhardt, Rey, Guérin) were also built in enormous blocks cut with bosses (Rey). Bartlett's engraving shows that the work to the south was square and had (still?) two towers of the same shape, while Rey reports that in 1870 two travelers still found there "a recognizable oblong tower" which formed one of the flanks.

Of all this there is nothing left. Paul Deschamps, who visited Safed in 1936, found only scattered stones there, on which spruce trees were growing and which it was impossible for him to interpret, and the remains of towers whose facing had been torn off64. In 1951, only a few lines were published65 about the excavations undertaken in 1950: “At Safed, a public garden within the precincts of the ancient citadel is being planned. Before the execution of this project, the Department of Antiquities instituted a trial excavation in the southern part of the area under the supervision of Mr Dothan. He unearthed remains of a polygonal wall, consisting of several courses of dressed stones with engaged pilasters at the corners (Fig. 12)66. This seems to have been part of the outer wall of a Crusader fortress. The investigation is to be continued”. Currently, if we take our eyes off the splendid panorama, we find only insignificant remains of the curtain at the top of the rock and lower down traces of a ditch and a postern (?): the site of the castle , which was once the glory and pride of the Order of the Temple, has been converted into a public park, where a very simple monument recalls the last siege of Safed and the battles of May 10, 1948.

46 See the description of Pococke quoted above.

47 The other (plate tv) is in the book by EW Schulz, Reise in das gelobte Land, Mülheim ad Ruhr,

1852, between p. 64 and 65. The engraving is interesting because it shows the castle up close,

seen from the southwest. By contrast, the view of the fortress found in CW Wilson,

Picturesque Palestine, n, London, 1880, p. 91 [= G. Ebers and H. Guthe, Paliistina, 1,

Stuttgart, 1882, p. 3411, beautiful as it is (plate t), presents no detail of comparable

value, any more than the description of Safed on pages 74 and 92-93; the engraving showing

the Jewish quarter (p. 90), was reproduced by Y. Ben-Arieh (see below, n. 51), p. 228.

48 These same details: square keep in the southern part of the fortress, can be seen on

Schulz's engraving. Between p. 204 and p. 205 there is another engraving by Willmore,

depicting a view of Tiberias from the lake side. We see there, closer, the same

fortifications that, from afar, we can see on the engraving of Safed. In the

background rises the castle of Tiberias dominating the city.

49 Such towers still exist in fairly large numbers, Crusaders and Arabs having

used them extensively. The best preserved that I know is that which corresponded

with the castle of Marqab (Margat), some 60 km south of Latakia, to the right

of the road leading from (Tripoli by) Tartous to this city (Bordj es Sabi).

50 The original edition appeared in Utrecht, the same year as the English translation,

which I quote here as more practical. The Dutch title is Reis door Syrii en Palestina in 1851 in 1852.

51 The 1882 edition adds to these words: “The inhabitants are fanatical and quarrelsome.

In 1875, they attacked the small expedition led by Mr. Conder and more or less seriously

wounded all its members” (cf. CR Conder, Tent Work in Palestine, London, 1889, p. 297:

“On Saturday, 10th July, 1875, the Survey party marched to Safed, where they were

endangered by a fanatical attack by the Moorish settlers of the town. The Survey was

suspended in consequence (cf. p. xii of the Introduction: "After the attack on the

party at Safed in 1875, the work was suspended for a year") and the spread of choiera

necessitated the withdrawal of the party from Palestine. The chief offenders were however

imprisoned at Acre, and a sum of L. 270 was paid as a fine to the Committee of the Palestine

Exploration Fund”) (In the edition published in 1878, vol. II, p. 190-203, the episode is

told in detail). As for Lieutenant Conder, we will find him later in connection with the

Surie of Western Palestine, which he led for a long time. On this subject, as on the

subject of a large number of other explorers, one will henceforth consult Yehoshua

Ben-Arieh, The Rediscouery of Me Hot) , Land in Me Nineteenth Cenitay, Jerusalem-Detroit

(Michigan, usit), 1979 (on Conder and Survey of Western Palestine, pp. 209 et seq.).

52 The Frankish colonies of Syria in the 12th and 10th centuries, Paris, 1883, p. 445-446.

53 Geographical, historical and archaeological description of Palestine, 3rd part: Galilee, t. ii, Paris, 1880, p. 420-421.

54 vol. 1 (Galileo), London, 1881, p. 248-250 (see above, n. 51). On page 250,

in smaller type, Guérin's notice is quoted, translated into English. However,

this in no way means that the lieutenant explorers found it exact, because in

the preface (p. v), it is said: “The notes of these officers are printed exactly

as they were sent in, nothing being added or suppressed. The additions made by

the editors are distinguished by being printed in small type. They will be found

to supplement the information. given by the Surveyors.” — There is another note

in the handwriting of EWG Masterman inserted in Palestine Exploration Fund, Quarterly

Statement for 1914, p. 175-176, where we read: "The great ruined castle with its double

line of ramparts, making a total fortified area of about 350 yards [ca. 320 m] by 150

yards [ca. 137 m], running roughly speaking north and south, though to-day an almost

shapeless mass, still stimulates the imagination to conjure up the vast fortress which

must here have dominated the country. Its previous state of ruin is said to be chiefly

the result of the earthquake of 1759, though doubtless that of 1837 contributed to its

decay. But long before that most of the masonry of its original construction must have

perished, and that building which was destroyed in the eighteenth century was but the

comparatively poor work of Dhahr el-'Omer who dominated Galilee earlier in that century.

Almost all the well-cut masonry above the surface has been carted off, as the place has

been used as a quarry for building stone for centuries; but everywhere below the surface

the remains of the earlier buildings may be found. A thorough excavation of this site

would be of undoubted interest. Near the “Keep” some large cisterns are still visible —

a considerable source of danger to the unwary. There are also vaulted passages in places.

One in the south-west part of the outer moat has recently been opened for some 60 yards

[ca. 55m]. At its north-west end, as far as it has been cleared, it is a fine vaulted

passage, over seven feet [ca. 2.15 m] high and four feet [ca. 1.22 m] wide, with well-cut

stones from one to two feet wide [ca. 30.5-61 cm] and sometimes three feet long [ca. 92cm];

at the other end, where the passage gradually curves east and then somewhat north-east,

running towards (and perhaps under) the inner moat, the passage has been constructed of

small stones, and, as a result of earthquake troubles, it has become extraordinarily twisted,

the center of the arch being diverted to the north, and the whole passage appearing here to

be in imminent danger of collapsing. On the fine masonry of the north-west extremity are

many "Mason's Marks", specimens of which, drawn to scale, I append [= plance vitt]. It

seems to me this passage must belong to the original Crusading work. Where the passage

eventually led to it is impossible to say without actual excavation; at the north-western

extremity there is an embrasure in the outer wall for shooting through, but just before

this, where a strong door was once situated, there are signs of steps leading downwards."

55 Compare Deschamps, The Defense of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, p. 140-141, n. 3: "...

since the keep of Margat rounded on its face is 21 meters wide and the keep of Coucy 31

meters in diameter". This dungeon of Coucy was well known to Rey, who himself compares

it, not to that of Safed, but precisely to the dungeon of Margat (Marqab) (Colonies franques, lc, p. 124).

56 vol. he, p. 292-295. See also Jean Richard, Cyprus under the Lusignans. Cypriot documents

from the Vatican Archives (11th and 15th centuries), Paris, 1962, p. 20.

57 See note 31, and RBC Huygens, Saladin's campaign in Northern Syria (1188), in Symposium Apamea of Syria,

Brussels, 1972, p. 273-284 (pp. 277-278). The builders of the castle of Safed undoubtedly updated

advantage the slope of the hill, which at the same time provided a natural glacis that it was enough to build:

it is the impression which one gains on the spot and which seems to confirm the engraving of Schulz (plate iv).

58 Deschamps, The Defense of the County of Tripoli, p. 146, in its summary of my first edition, confuses,

by mixing them, the measurements of the two enclosures and the towers.

59 Van Egmond-Heyman also speak expressly of two masonry ditches.

60 See William of Tyr, xv, 24, about the construction of the castle of Ibelin (near Yavneh,

north-east of Ashdod) in 1144 (text according to the critical edition that I am preparing

in collaboration with H.-E. Mayer): ... in prefato colle, firmissimo opere, iactis in altum

fundamentis, edificant presidium cum turri bus quattuor, veteribus edificiis, quorum multa

adhuc supererant vestigia, lapidum ministrantibus copiam, puteis quoque vetusti temporis,

qui in ambitu urbis dirute frequentes apparebant, aquarum habundantiam tum ad opens

necessitatem, tum ad usus hominum largientibus. The translator (the Eracles) amplifies:

First the foundations lay, then four twists; stones found enough in this place of

fortresses which had once been there, for, as the saying goes: "Chastel abatuz est

demi refez". Three other passages from William of Tyre, whose analogies both in substance

and in form will be noted, further underline what has just been said. They describe, the

first the construction of the castle of Blanche-Garde, northeast of Ashkelon, in 1144,

the second that of a fortress in the ruins of Gaza in 1149, the third that of the castle

of Darom (Darum = Dar Rûm), not far from Gaza, in 1170: (xv, 25).

... vocatis artificibus simul et populo universo necessaria ministrante edificant solidis fundamentis et lapidibus quadris opidum cum turribus quattuor congrue altitudinis, unde osque in urbem hostium (Ashkelon) liber esset prospectus, hostibus predatum exire volentibus valde invisum et formidabile, nomenque ei vulgari indicunt appellation Blanche Guarda, Latin quod dicitur Alba Specula. Castrum ergo perfectum and omnibus partibus suis absolutum [cf. xv, c. 24] dominus rex in suam suscepit custodiam, et tain victu quam armis sufficienter munitum viris prudentibus et rei mili taris habentibus experientiam... servandum commisit. Porro qui circumcirca possidebant regionem, predictorum confisi munimine et vicini tate castrorum, suburbana loca edificaverunt quam plurima, habentes in eis familias mullas et agrorum cultores, de quorum inhabitatione fada est regio Iota securior et alimentorum mulla lotis finitimis accessit copia; (xvit, 12) ... Gaza civitas antiquissima... edificiis preclara, cuius antique nobilitatis in ecclesiis et amplis domibus, licet dirutis, in marmore et magnis lapidibus, in multitudine cisternarum, puteorum quoque aquarum viterium, multa et grandia exstabant argumenta. Fuerat autem sita in colle aliquantulum edito, magnum salis et diffusum infra muros continens ambitum... partem predicti collis occupant et iactis ad congruam altitudinem fundamentis [cf. xxl, 26] opus muro insignia et turribus edificant... Nec solum urbe predicta, ad cuius lesionem constructum erat illud presidium, useful recalcitrante flees, sed etiam ea devicta quasi regni limes ab austro contra Egyptios pro multo flees regioni tutamine; (xx, 19) ... predictum castrum. fundaverat occasione vetustorum edificiorum, quorum aliqua adhuc ibi supererant vestigia. . Condiderat autem rex ea intentione predictum municipium, ut et fines suos dilataret et suburbanorum adiacentium, que nostri casalia dicunt [cf. xxit, 20], annuos redditus et de transeuntibus statutas consuetudines plenius et facilius sibi posset habere.61 See above, p. 15-16.

62 In August 1947, a few photos (v-vu) were taken during the development of the site (see below). Kindly made available to me by the Israeli Department of Antiquities and Museums in Jerusalem, they show one of the large Frankish cisterns at the top of the hill (another was some 27m away). Plate y: interior of the cistern (depth: 11 m), with (A) masonry resting on the rock and (B) vaulted opening of a tunnel 6 m 20 long opening in the southern part; in C, the carefully fitted cupola. Plate Yi: details of y A and B. Plate VIE the tunnel photographed from inside the cistern in a north-south direction. A brief report (with sketch), made in July 1947 by N. Makhouly and preserved in the archives of the Israeli Archaeological Service, gives some additional details, without however providing precision on the purpose of the tunnel: “It was found that the Municipal laborers were engaged in clearance work of the cistern and cutting a new tunnel in the rock for laying pipes in since about 35 days ago. During that period they have completed the clearance of the high level cistern and the deep shaft passage... to the south. It was discovered that the cistern is connected with the passage by a very high arched opening... The lower two thirds of the cistern-walls are thickly plastered for storing water in, while the remaining top part is domed with regular stones of fine dressing. At the south end of the cistern a narrow opening [v B] leads to the deep shaft which has an opening from the top. The opening and most of the shaft were tightly filled in with stone rubble dipped in mortar. Both sides of the shaft-passage were strongly plastered with a pink-coloured mixture. The masonry below the plaster is made up of large blocks of stones of wall dressing. It undoubtedly belongs to the Crusaders period. Next to the passage to the south came natural rocks”.

63 See also Deschamps, Le Crac des Chevaliers, p. 152.

64 Defense of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, p. 140-141 and the Album, pl. xxxiv D, E.

65 American Journal of Archaeology, Lv, 1951, p. 87 (Archaeological News, Israel Section).

66 A photo of a wall fragment (photo provided by Mr. Dothan) can be found in Mr. Segonne's book (see note 19), p. 157. During the winter of 1961-1962, Mr. Adam Druks also carried out excavations in Safed, but the results have not been published.

- from Robinson and Smith (1856:422)

- Edward Robinson visited and described Safed and the Castle on the Citadel in Safed before and ~18 months after (June 1838 CE) the 1837 CE earthquake

Though already partially in ruins before the earthquake, it was nevertheless sufficiently in repair to be the official residence of the Mutesellim ; and on a former visit to Safed, my companion had paid his respects to that officer within its walls. The fortress is described as having heen strong and imposing, with two fine large round towers ; it was surrounded by a wall lower down, with a broad trench ... Such was Safed down to the close of the year 1836.After

But on the first day of January, 1837, the new year was ushered in by the tremendous shocks of an earthquake, which rent the earth in many places, and in a few moments prostrated most of the houses, and buried thousands of the inhabitants of Safed beneath the ruins. The castle was utterly thrown down ; the Muhammedan quarter, standing on more level ground and being more solidly built, were somewhat less injured