Tiberias in the Ottoman Period

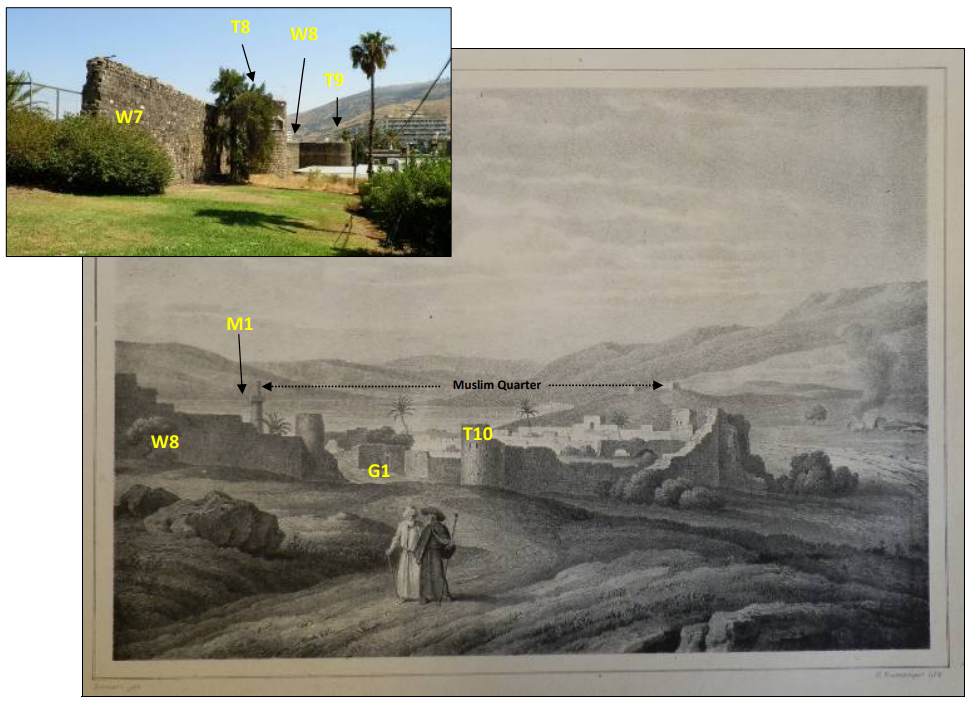

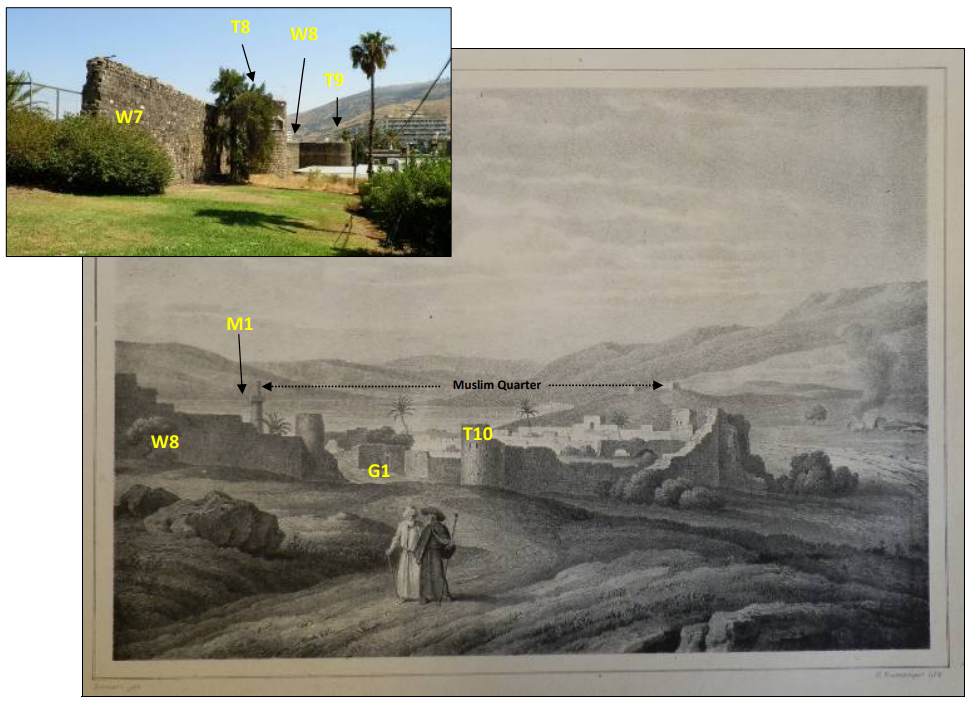

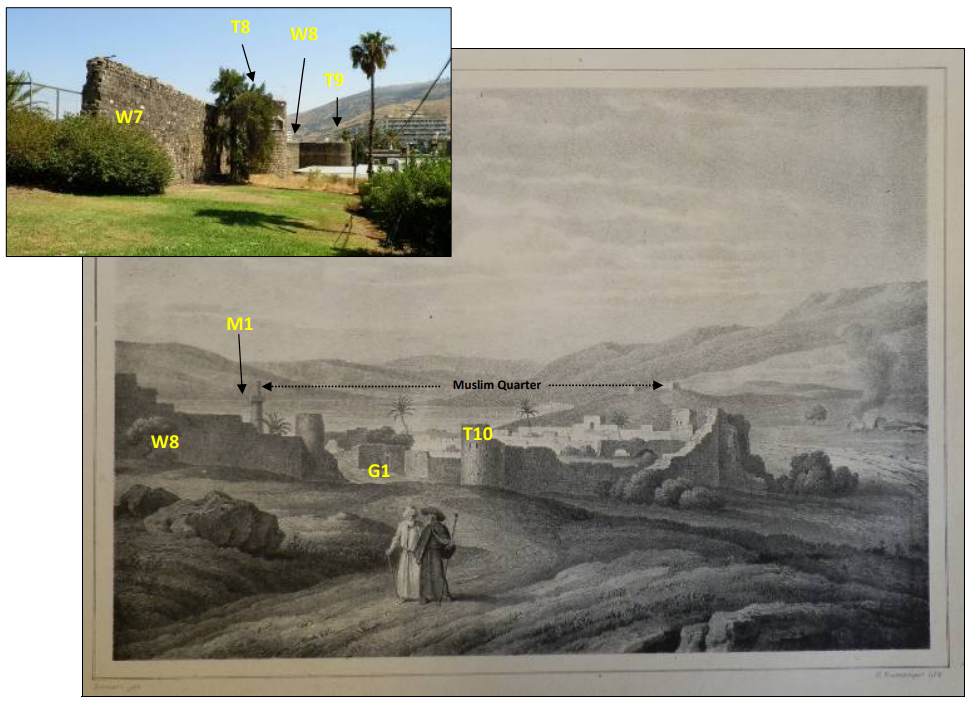

Painting of Tiberias by David Roberts in 1839 CE

Painting of Tiberias by David Roberts in 1839 CEclick on image to access a high resolution magnifiable image

David Roberts (1839) - Cleveland Museum of Art - from Wikipedia

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tverya | Hebrew | טיבריות |

| Ṭabariyyā | Arabic | طبريا |

| Rakkath | Biblical Hebrew (Joshua 19:35) | רקבת |

| Chamath | Ancient Israelite (Jewish tradition) | חמת |

| Tiberiás | Ancient Greek | Τιβεριάς |

| Tiveriáda | Modern Greek | Τιβεριάδα |

| Tiberiás | Latin | Tiberiás |

| Tiberias | English | Tiberias |

- from Zohar (2017)

The prosperity of the Jewish community did not last long and sometime at the beginning of the seventeenth century the Jews were forced to leave due to Ottoman tyranny (Roger 1646, De Thévenot 1971). The turning point for Tiberias was the rule of Dahir al-Umar of the Bedouin Zaydan family. Close to the mid-eighteenth century he gained control of Tiberias and other Galilean regions and gradually accumulated massive power. His dominancy did not escape the eyes of Suleiman, the Pasha of Damascus, who decided to overthrow Dahir’s rule by besieging Tiberias three times: in 1738, 1742 and 1743. The first two sieges were failures and during the last attempt Suleiman died of an intestine illness (Bnayahu 1946, Heyd 1969, Nachshon 1980). The son of Dahir, Chulaybi, had fewer confrontations but, like his father, kept strengthening Tiberias and in 1750 also built a citadel on a hill at the northwest corner of the city (Hasselquist 1766). In October and November 1759, the walls and the Citadel were severely hit by two consecutive earthquakes (Ambraseys and Barazangi 1989, Ambraseys 2009), but were gradually restored towards the end of the nineteenth century (Mariti 1791).

In October 1831 the Egyptian Ibrahim Pasha invaded Palestine on his way north and in May 1833 he completed the conquest of Syria and Palestine. In 1834 another damaging earthquake struck Palestine but no damage to Tiberias or northern Palestine was reported (Ambraseys 2009). In the same year a Fellahin rebellion erupted in the mountainous areas of Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Nablus, Transjordan and northern Galilee. The rebels took over Tiberias for a short period but the Egyptians, with reinforcements from the south, eventually managed to gain back control of the city (Ben-Zvi 1954). From that year until the 1837 earthquake the city remained under Egyptian rule.

- from Zohar (2017:6-12)

- Table 1 Localities reported

as damaged in 1837 CE Safed Quake and Legend/Key to sites in the Map in Figure 6 - from Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1

Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

- Symbol: identification of the structure (as mapped in Figure 6)

- Damage: a rough estimation of the scope of the damage

- N (no damage)

- S (slight damage)

- P (partial damage)

- T (total destruction)

Zohar (2017) - Fig. 6 Map of Tiberias

before the 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1).

The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848).

Zohar (2017) - Fig. 7 3D reconstruction

of Tiberias before and after the 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

3D view of Tiberias

- Before the earthquake, superimposed on a topographic (DEM) surface

- after the earthquake overlain on a geological surface layer

- Al: Alluvium, colluvium, soil

- Nbg: Bira and Gesher formations

- Pβc: cover basalt

Prominent features (Table 1) are labelled in black. Note that the majority of Tiberias is located on basalt rocks and note the extensive damage along the fault that crosses the western walls.

Zohar (2017)

- Table 1 Localities reported

as damaged in 1837 CE Safed Quake and Legend/Key to sites in the Map in Figure 6 - from Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1

Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

- Symbol: identification of the structure (as mapped in Figure 6)

- Damage: a rough estimation of the scope of the damage

- N (no damage)

- S (slight damage)

- P (partial damage)

- T (total destruction)

Zohar (2017) - Fig. 6 Map of Tiberias

before the 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1).

The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848).

Zohar (2017) - Fig. 7 3D reconstruction

of Tiberias before and after the 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

3D view of Tiberias

- Before the earthquake, superimposed on a topographic (DEM) surface

- after the earthquake overlain on a geological surface layer

- Al: Alluvium, colluvium, soil

- Nbg: Bira and Gesher formations

- Pβc: cover basalt

Prominent features (Table 1) are labelled in black. Note that the majority of Tiberias is located on basalt rocks and note the extensive damage along the fault that crosses the western walls.

Zohar (2017)

Much of the sources divide their descriptions of the city by the existing ethnic groups at the time, i.e., Jews, Muslims and Christians. Along almost the entire nineteenth century each of these groups resided in a different and separated area within the city. Consequently, the reconstruction of the Tiberias cityscape and the following damage analyses was carried out in light of this sub-division of the city. A summary of the prominent structures, the reconstructed 2D map and the 3D models appear in Table 1, Figures 6 and 7, respectively.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Tiberias was a desolated city situated on the western shores of the Sea of Galilee (Figure 6) (Volney 1788, Richardson 1822, Irby and Mangles 1823). Roughly, the city was divided into three quarters:

- the Muslims resided mainly at the northwestern area

- the Jews occupied an isolated quarter at the eastern side close to the shore

- several dozen Christians lived in the southern end of the city (Avissar 1973, Schur 1987, Ben-Yaakov 2001).

The city was surrounded by the mid-eighteenth century walls repaired by Dahir al-Umar and his son Chulaybi. Their thickness ranged between 80 and 120 cm and Birav (Bnayahu 1946) reported that they were so high that ladders were needed to climb over them. Other western travellers estimated their height between 6 and 8 m (Pococke 1745, Hasselquist 1766, Spilsbury 1823, Robinson and Smith 1856). The walls were flanked by 21 circular turrets standing at unequal distances between each other (Irby and Mangles 1823, Jowett 1826). According to Jacotin’s map and Burckhardt’s sketch, there were only two gates to the city: a western main gate and a small southern gate (Jacotin 1799, Burckhardt 1822). Like other Ottoman cities, the citadel on the northern hill of Tiberias protected the town from outer invasions (Pococke 1745, Hasselquist 1766, Clarke 1810– 1823).

There were two mosques in the city: the largest was the al-Zaydani (al-Umari), named after Dahir’s family name, while the other was al-Bahri (the sea mosque), and located south of the Jewish quarter. The Church of St. Peter was situated north of the Jewish quarter but the house of the Catholic priest, however, was at the southern end of the city.

Additional Ottoman buildings, located in the Muslim quarter close to the western gate, were the houses of the Aga (governor house or Seraiah), the Kadi, the Imam and the army commander (Schur 1987, Abbasi 2006) . A small bazaar decorated by massive vaults was located in the centre of the city. Other vaulted arches were located at the southern shoreline facing the sea (Burckhardt 1822).

The Jewish quarter occupied a portion of the city close to the shore. It was surrounded by a high wall with a western entrance gate, which was regularly shut at sunset. Apparently, there were at least two synagogues and a ‘Kolell’ (a Jewish school) within the quarter and probably another one at the southern end of the city: Stephens reported on two synagogues and two schools and Jowett reported on two schools and three synagogues. I assume that the ‘Kollell’ reported in 1833 in the letter of Rabbi Yaa’kov Menlis, is the ‘Reysin’ Kollell, located close to Menahem Mendel’s house (Stephens 1839, Jowett 1826, Robinson and Smith 1856, David Debith Hillel in Ya’ari 1976, pp. 512–514, Scholz 1822, de Gramb 1840, Schur 2002). Although Christians lived mainly in southern Tiberias, there were also a few dwellings of Jews there: von Puckler Muskau reported that a wealthy Jew (Hayim Weisman?) had 21 houses to let. He does not mention their exact location but since there are no reports of hotels in the Jewish quarter, I assume they were located in the southern part of the city (Pueckler-Muskau 1844). Located about half a kilometre south of the city were the Jewish and Muslim cemeteries and about one kilometre further south the thermal baths for local and touristic use (Seetzen 1810, Robinson and Smith 1841). North of the city there were several sacred tombs (Mendel 1839, Robinson and Smith 1856, Guerin 1880) and west of it a small agricultural area. One major road led to the city from the south and two others from the west (Jacotin 1799, Buckingham 1822, Olin 1844).

- from Tiberias - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 1a Regional Damage

Distribution from the 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1a

Damage distribution in Ottoman Palestine and its close surroundings caused by the 1837 earthquake (Ambraseys 1997, 2009) and classified by the degree of severity (Zohar et al. 2013);

Zohar (2017) - Fig. 6 Map of Tiberias

before the 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848).

Zohar (2017) - Fig. 8 Map of damage in

Tiberias due to 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

The spread of the earthquake damage that resulted in Tiberias by comparing the two HGIS models of before and after the earthquake (Figure 7).

Zohar (2017)

- Fig. 1a Regional Damage

Distribution from the 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1a

Damage distribution in Ottoman Palestine and its close surroundings caused by the 1837 earthquake (Ambraseys 1997, 2009) and classified by the degree of severity (Zohar et al. 2013);

Zohar (2017) - Fig. 6 Map of Tiberias

before the 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848).

Zohar (2017) - Fig. 8 Map of damage in

Tiberias due to 1837 CE Safed Quake from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

The spread of the earthquake damage that resulted in Tiberias by comparing the two HGIS models of before and after the earthquake (Figure 7).

Zohar (2017)

- Fig. 1b Satellite View of

the Old City of Tiberias from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1b

General overview of the old city of Tiberias.

Zohar (2017) - The "Old City" of Tiberias in Google Earth

- The "Old City" of Tiberias on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 1b Satellite View of

the Old City of Tiberias from Zohar (2017)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1b

General overview of the old city of Tiberias.

Zohar (2017)

Chronology is well established as damage and destruction in Tiberias due to the 1837 CE Safed Quake was described and recorded by several contemporaneous sources based on first hand accounts - some of which are listed below:

| Source | Report | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Article in the Missionary Herald by William McClure Thomson | The first day of this year (1837 CE) will be long remembered as the anniversary of one of the most violent and destructive earthquakes which this country has ever experienced |

|

| The Times (of London) | A LIST OF TOWNS ETC., DESTROYED OR INJURED IN SYRIA BY THE EARTHQUAKE ON THE 1st OF JANUARY |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Damaged and Tilted Walls | Citadel Walls (P1) and turrets (T4-T7)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2bthe Citadel in Tiberias where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017)

Fig. 16

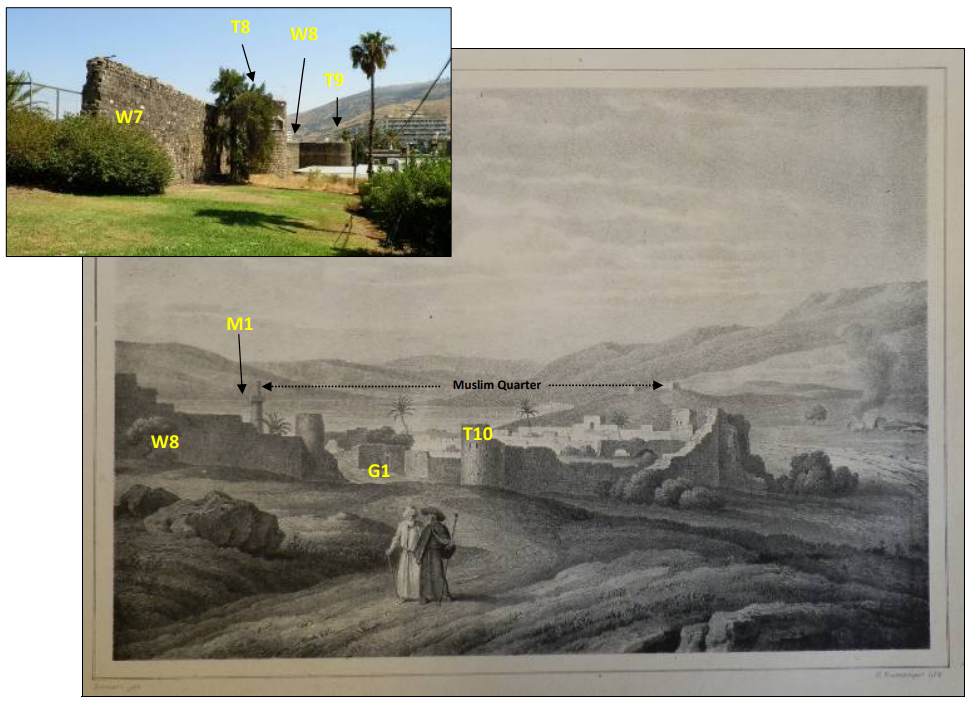

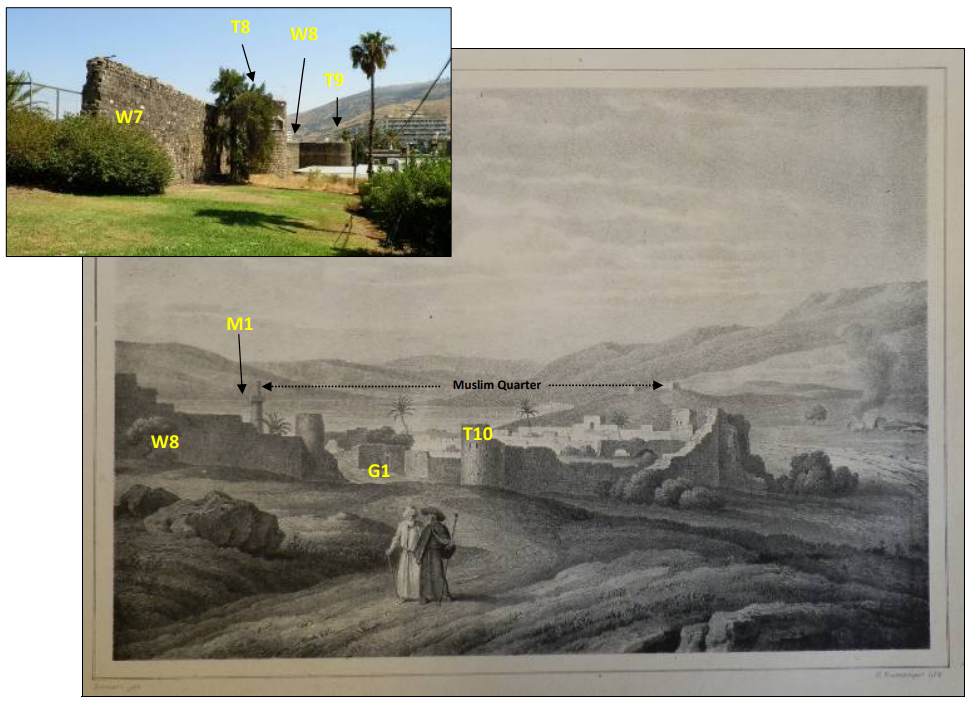

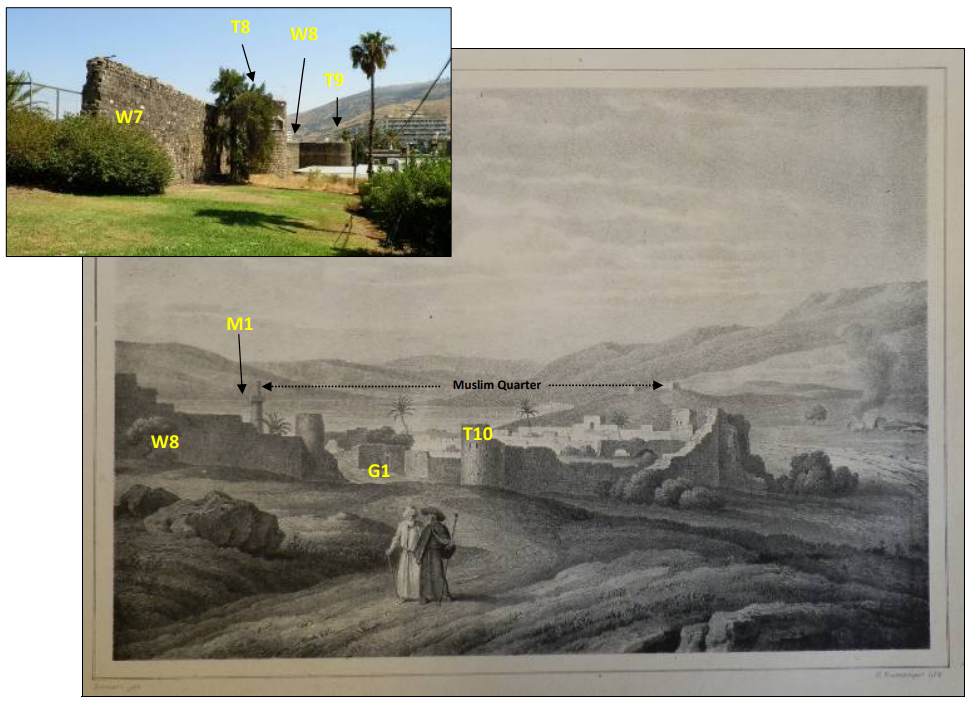

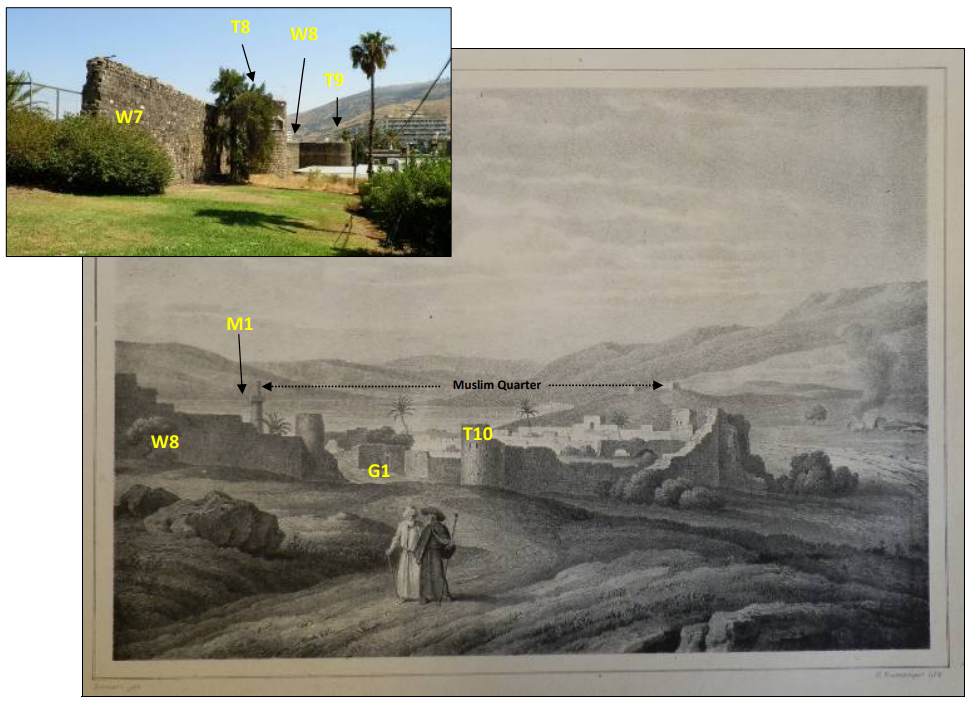

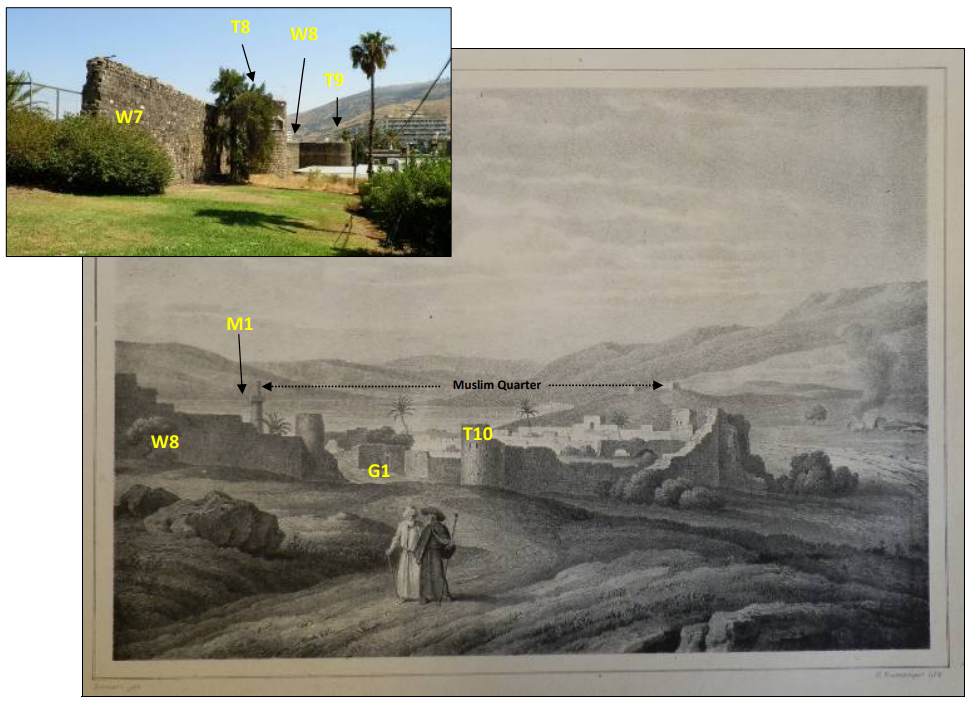

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19. 1839a: Damage to the citadel and walls. Note the completeness of the Seraiah (P2) and the presence of the minaret of al-Zaydani mosque (M1) (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 20

Fig. 201839b: Tiberias from the south. Note the arched vaults (P8), al-Zaydani mosque and minaret but no dome, the ruined citadel (P1), the Seraiah (P2), a Synagogue (Etz Hayim?, S1), turret T1 in the water, and St. Peter church (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 25

Fig. 251841: Ruins of Tiberias. The citadel (P1) is depicted as slightly damaged (Munk, 1845). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 26

Fig. 261842a: Tiberias and its citadel in a drawing drawn from the north (Bartlett in Stebbing, 1847). Note the similarity of T4 and T5 to their recent state (upper left corner) and the accuracy of the hatch (red square) as drawn by Bartlett Zohar (2017)

Fig. 30

Fig. 301842e: sketch of Tiberias from the west. Large breaches appear in the western and southern walls of the city (Bartlett, 1850). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 35

Fig. 351851-52: Tiberias from the south (Van de Velde, 1857). Zohar (2017) |

|

| Sheared Wall | Southern turret in Southern Wall

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2f

Fig. 2fone of the southern damaged turrets in Tiberias’s walls. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017)

Sheared turret in Tiberias' southern Wall

Sheared turret in Tiberias' southern WallPhoto by Jefferson Williams on 11 June 2023

Fig. 38

Fig. 381863: Tiberias from the western road leading to the main gate. Note the possible identification of turret T17 (Unknown, 1867). In my opinion the drawing was copied from Munk (1845). Zohar (2017) |

|

| Dome collapse | al-Zaydani Mosque (M1)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2aal-Zaydani Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017)

Fig. 4

Fig. 41814: al-Zaydani mosque drawn from close range within the city itself (Light, 1818). Note the relatively large dome also present in other pre-1837 drawings (e.g., Buckingham, 1822; Marilhat in de Laborde, 1837; Wilson, 1823). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19. 1839a: Damage to the citadel and walls. Note the completeness of the Seraiah (P2) and the presence of the minaret of al-Zaydani mosque (M1) (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 20

Fig. 201839b: Tiberias from the south. Note the arched vaults (P8), al-Zaydani mosque and minaret but no dome, the ruined citadel (P1), the Seraiah (P2), a Synagogue (Etz Hayim?, S1), turret T1 in the water, and St. Peter church (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 22

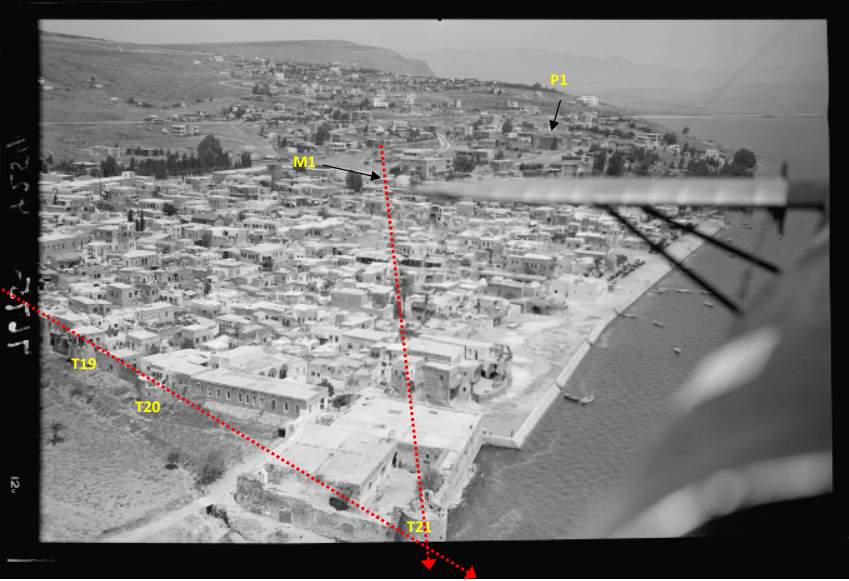

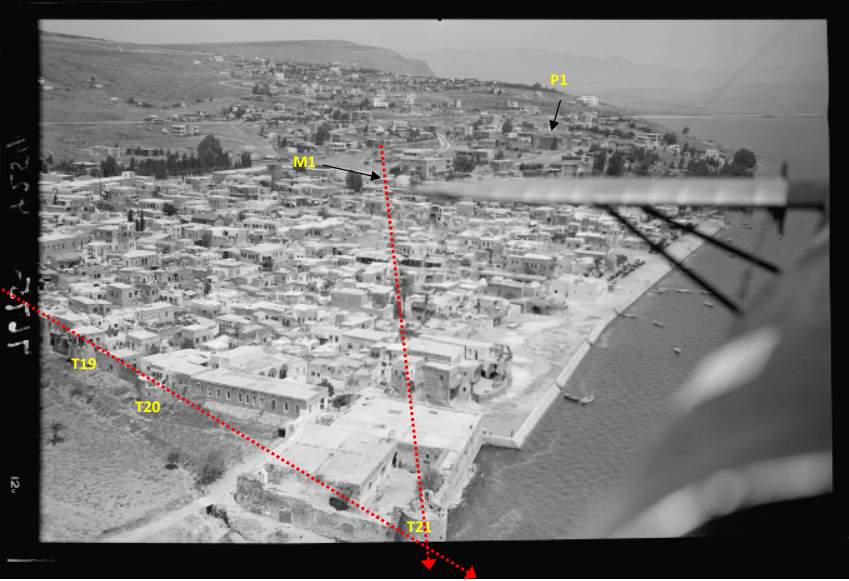

Fig. 221839d: The citadel (P1) is depicted partially ruined; the Seraiah (P2); the walls that are partially ruined, al-Zaydani mosque without a dome (Roberts, 1842-1849). Note turret T21 leaning towards the east and its lower supporting belt (noted by red arrow). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 25

Fig. 251841: Ruins of Tiberias. The citadel (P1) is depicted as slightly damaged (Munk, 1845). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 32

Fig. 321848: Tiberias from the north, probably drawn somewhere on the hill of the citadel (Lynch, 1849). Prominent features:

Zohar (2017)

Fig. 33

Fig. 331849: the road from Safed leading to Tiberias, the citadel and the walls (Spencer, 1850). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 35

Fig. 351851-52: Tiberias from the south (Van de Velde, 1857). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39c.1870: a photograph probably taken from the hill of the citadel (Bonfils, 1878?). The northern region was not populated. No minaret of al-Bahri mosque, no dome to al-Zaydani. Zohar (2017) |

|

| Minaret Collapse | al-Bahri Mosque (M2)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2cal-Bahri Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017)

Fig. 35

Fig. 351851-52: Tiberias from the south (Van de Velde, 1857). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39c.1870: a photograph probably taken from the hill of the citadel (Bonfils, 1878?). The northern region was not populated. No minaret of al-Bahri mosque, no dome to al-Zaydani. Zohar (2017) |

|

| Vault Destruction - completely or badly destroyed | Vaulted Bazaar (P7)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dremains of the massive vaults in southern Tiberias (noted by red arrow). Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

|

| Damaged Arches | Vaulted Arcs (P8)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 20

Fig. 201839b: Tiberias from the south. Note the arched vaults (P8), al-Zaydani mosque and minaret but no dome, the ruined citadel (P1), the Seraiah (P2), a Synagogue (Etz Hayim?, S1), turret T1 in the water, and St. Peter church (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 45

Fig. 451898-1914: (ACPD, 1898-1914b) Zohar (2017) |

|

| Collapsed Walls | dwellings

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

|

| Damaged Walls | City Walls (W1-21)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 71828: Tiberias from the south in the book of Leon de Laborde. The latter visited Palestine in 1828 but his book on Syria, Lebanon and Palestine was published only in 1837. The book contains also other artist’s drawings. This drawing was drawn by Marilhat and considered realistic. For example, the number of turrets and location of the citadel are accurate in light of our current knowledge of the Tiberias morphology (Marilhat in de Laborde, 1837) Zohar (2017)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15Prior to 1837: Tiberias from the south (Leitch & Foster, 1855). In my opinion, this is probably a copy of the sketch after Marilhat (de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17Before 1837: The drawing portrays Tiberias prior to the earthquake but the date of painting is unresolved. It appears only in the 5th edition of Lindsay (1858). Lindsay visited Palestine twice and only after the earthquake (1837 and 1847) and thus, in my opinion, the drawing is a copy of a previous one, perhaps of Lehoux (de Laborde, 1837) Zohar (2017)

Fig. 35

Fig. 351851-52: Tiberias from the south (Van de Velde, 1857). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

|

| Damaged Walls | Turrets (T1-20)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

|

|

| Tilted Wall | Leaning Turret (T21)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 31

Fig. 311842f: the leaning turret (T21) and the citadel (P1) (Bartlett, 1850). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 22

Fig. 221839d: The citadel (P1) is depicted partially ruined; the Seraiah (P2); the walls that are partially ruined, al-Zaydani mosque without a dome (Roberts, 1842-1849). Note turret T21 leaning towards the east and its lower supporting belt (noted by red arrow). Zohar (2017) |

|

| Collapsed Wall | Main Gate (G1)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 11

Fig. 111835: The town from the north. Note the turrets and the two minarets of al-Zaydani and al-Bahri mosques (Harding, 1835). The drawing was probably copied from the drawing of Marilhat (in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 18

Fig. 181837: Tiberias from the north, after the voyage of Bernatz and Schubert (Bernatz & Schubert, 1839). The drawing seems to be realistic as prominent features (e.g., W8 and T10) are depicted in similar shape and size as they are today. JW: Gate G1 is 'missing' Zohar (2017) |

|

| Damaged Walls | Southern Gate (G2)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 71828: Tiberias from the south in the book of Leon de Laborde. The latter visited Palestine in 1828 but his book on Syria, Lebanon and Palestine was published only in 1837. The book contains also other artist’s drawings. This drawing was drawn by Marilhat and considered realistic. For example, the number of turrets and location of the citadel are accurate in light of our current knowledge of the Tiberias morphology (Marilhat in de Laborde, 1837) Zohar (2017) |

|

| Collapsed Walls | Walls of the Jewish Quarter (JW1-2)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

|

|

| Collapsed Walls | Gate of the Jewish Quarter (JG1)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

|

|

| Collapsed Walls | Etz-Ha'yim ('Sephardim') Synagogue (S1)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2e

Fig. 2eEtz-Hay’im Synagogue in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

|

| Collapsed Walls | Hasidim' Synagogue (S2)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

|

|

| Casualties | Tiberias

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

|

- Table 1 from Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

- Symbol: identification of the structure (as mapped in Figure 6)

- Damage: a rough estimation of the scope of the damage

- N (no damage)

- S (slight damage)

- P (partial damage)

- T (total destruction)

Zohar (2017)

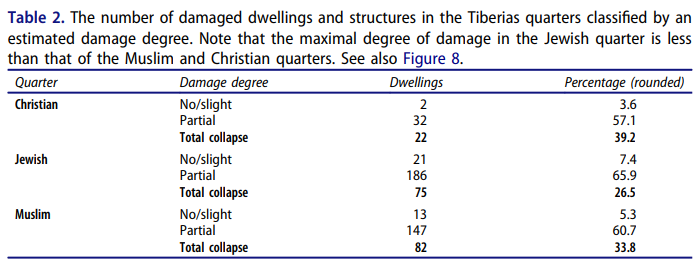

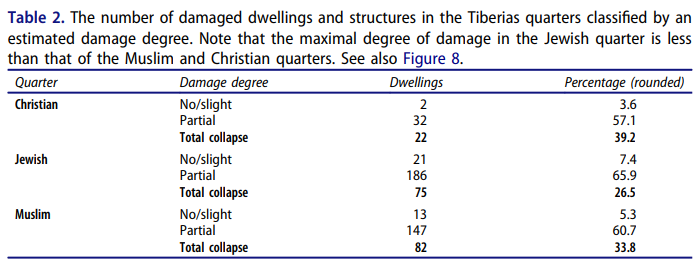

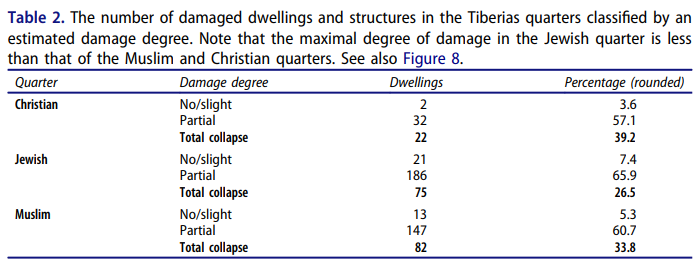

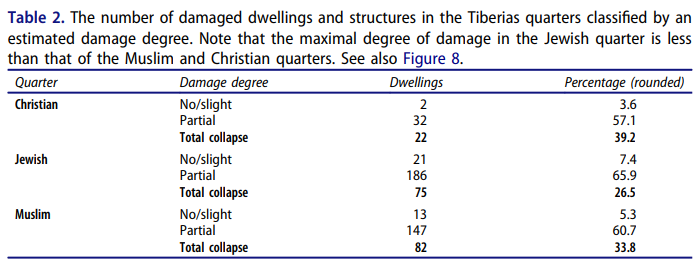

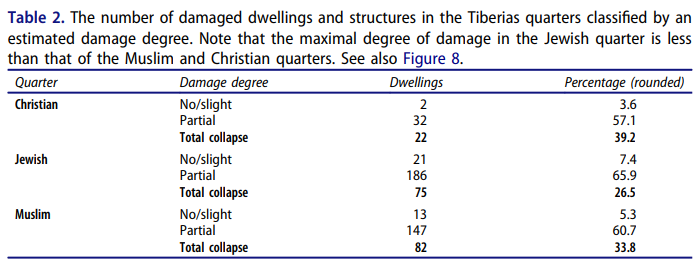

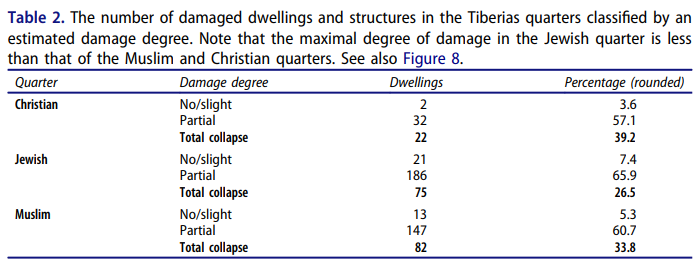

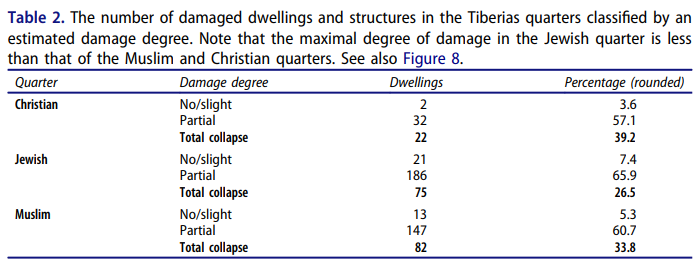

- Table 2 from Zohar (2017)

Table 2

Table 2The number of damaged dwellings and structures in the Tiberias quarters classified by an estimated damage degree. Note that the maximal degree of damage in the Jewish quarter is less than that of the Muslim and Christian quarters. See also Figure 8.

Zohar (2017)

- from Zohar (2017:13-15)

| Image | Figure | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2aal-Zaydani Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2a | al-Zaydani Mosque in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2bthe Citadel in Tiberias where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2b | the Citadel in Tiberias where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2cal-Bahri Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2c | al-Bahri Mosque in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dremains of the massive vaults in southern Tiberias (noted by red arrow). Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2d | remains of the massive vaults in southern Tiberias (noted by red arrow) |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2e

Fig. 2eEtz-Hay’im Synagogue in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2e | Etz-Hay’im Synagogue in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2f

Fig. 2fone of the southern damaged turrets in Tiberias’s walls. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2f | one of the southern damaged turrets in Tiberias’s walls where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent |

Zohar (2017) |

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

Zohar (2017) |

Table 1 | Damage Table | Zohar (2017) |

Table 2

Table 2The number of damaged dwellings and structures in the Tiberias quarters classified by an estimated damage degree. Note that the maximal degree of damage in the Jewish quarter is less than that of the Muslim and Christian quarters. See also Figure 8. Zohar (2017) |

Table 2 | Damage in the Quarters | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 6 | Tiberias before the 1837 CE Safed Quake | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 73D view of Tiberias

Zohar (2017) |

Figure 7 | 3D reconstruction of Tiberias before and after the 1837 CE Safed Quake |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 8

Fig. 8The spread of the earthquake damage that resulted in Tiberias by comparing the two HGIS models of before and after the earthquake (Figure 7). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 8 | Map of damage in Tiberias due to 1837 CE Safed Quake | Zohar (2017) |

Rotating the models enabled a 360° examination of damage from almost any direction, even from spots that were not covered by the nineteenth century artists, such as an eastern spot in the Sea of Galilee or aerial views. The two models of before and after the earthquakes were compared (Figure 7) in order to identify the structural damage and examine its spread (Figure 8). It seems that although the Tiberias area was relatively small, the spread of the damage as well as its severity was not uniform. This is clearly observed particularly along the walls and between the residential quarters of the city. In general, such variability in damage within a small area may imply different local site attributes, whereas the distance from the epicentre and the directivity effect are almost identical in any spot within that area. Among the most influencing site attributes, one can count the construction quality, surface geology and topography (Zaslavsky et al. 2000). The latter two can hardly explain the differences whereas almost the whole of Tiberias is situated on basalt rocks (Pβc) and apart from the moderate northern slopes, the city lies on a flat plain (Figures. 7(a,b)). The construction quality, however, varies and manifests several structural styles for residential dwellings, religious structures and government buildings (Figure 2). Unfortunately, at this stage there is no reasonable understanding of the vulnerability and resistance of these structures to earthquake shaking. Yet, it is still possible to classify Tiberias’s structures into two groups.

- The first, which was probably more resistant to earthquake shaking, includes the Citadel, walls, turrets and government buildings such as the Seraiah and Kadi houses Most of them, although badly damaged, remained partially standing, even in cases where they were located on a hill in the north of the city. This is, of course, no surprise for these structures were built in advance to withstand outer attacks and thus were probably quite stable. Yet, there is a prominent exception that deserves attention: The western part of the walls (between turrets T-12 and T-16), although built of the same materials and quality as the rest of the walls, collapsed completely, while the northern part, built on a slope, was only slightly damaged. Figure 8 portrays the spread of the damage in relation to the surface geology and suspected active faults. Accordingly, the majority of Tiberias is located on a single geologic foundation of basalt rocks but close to the western walls, there is a fault. This fault, suspected to be active (Sagy et al. 2013), crosses the southern walls between T16–T17 and runs parallel to the western walls for about 200 m within the proximity of only 50 m. In addition, the fault runs in between the basalt and alluvium lithologies and perhaps this transition zone contributed to the increase of the damage. However, further site-specific investigation, which is beyond the scope of this study, is needed to verify the mechanical role of this fault and the lithological contrast in the stability of the western walls and the nearby structures.

- The second group includes dwellings and residential houses, most of which were completely damaged beyond repair. The damage in this category varies. The Jewish quarter seems to be slightly less damaged than the other quarters (Table 2) although the number of Jewish victims was greater (Robinson and Smith 1841). The explanation for this contradiction is not clear at this stage. Located along the shores of the lake, the Jewish quarter was more populated and clustered than the others and thus the dwellings in it were most likely of different architectural styles. In addition, a large part of the Muslim quarter in the north end of the city was located on a sloped hill whereas the Jewish and Christian quarters were located on a plain surface (Figure 7(a)). Thus, these factors also may have influenced the resistance to damage, but until the Ottoman construction styles are fully characterized, resolving this damage differentiation is rather complex.

- from Fig. 8 of Zohar (2017)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8The spread of the earthquake damage that resulted in Tiberias by comparing the two HGIS models of before and after the earthquake (Figure 7).

Zohar (2017)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damaged and Tilted Walls | Citadel Walls (P1) and turrets (T4-T7)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2bthe Citadel in Tiberias where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017)

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19. 1839a: Damage to the citadel and walls. Note the completeness of the Seraiah (P2) and the presence of the minaret of al-Zaydani mosque (M1) (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 20

Fig. 201839b: Tiberias from the south. Note the arched vaults (P8), al-Zaydani mosque and minaret but no dome, the ruined citadel (P1), the Seraiah (P2), a Synagogue (Etz Hayim?, S1), turret T1 in the water, and St. Peter church (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 25

Fig. 251841: Ruins of Tiberias. The citadel (P1) is depicted as slightly damaged (Munk, 1845). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 26

Fig. 261842a: Tiberias and its citadel in a drawing drawn from the north (Bartlett in Stebbing, 1847). Note the similarity of T4 and T5 to their recent state (upper left corner) and the accuracy of the hatch (red square) as drawn by Bartlett Zohar (2017)

Fig. 30

Fig. 301842e: sketch of Tiberias from the west. Large breaches appear in the western and southern walls of the city (Bartlett, 1850). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 35

Fig. 351851-52: Tiberias from the south (Van de Velde, 1857). Zohar (2017) |

|

VII + |

| Sheared Wall | Southern turret in Southern Wall

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2f

Fig. 2fone of the southern damaged turrets in Tiberias’s walls. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017)

Sheared turret in Tiberias' southern Wall

Sheared turret in Tiberias' southern WallPhoto by Jefferson Williams on 11 June 2023

Fig. 38

Fig. 381863: Tiberias from the western road leading to the main gate. Note the possible identification of turret T17 (Unknown, 1867). In my opinion the drawing was copied from Munk (1845). Zohar (2017) |

VIII + | |

| Dome collapse | al-Zaydani Mosque (M1)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2aal-Zaydani Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017)

Fig. 4

Fig. 41814: al-Zaydani mosque drawn from close range within the city itself (Light, 1818). Note the relatively large dome also present in other pre-1837 drawings (e.g., Buckingham, 1822; Marilhat in de Laborde, 1837; Wilson, 1823). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19. 1839a: Damage to the citadel and walls. Note the completeness of the Seraiah (P2) and the presence of the minaret of al-Zaydani mosque (M1) (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 20

Fig. 201839b: Tiberias from the south. Note the arched vaults (P8), al-Zaydani mosque and minaret but no dome, the ruined citadel (P1), the Seraiah (P2), a Synagogue (Etz Hayim?, S1), turret T1 in the water, and St. Peter church (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 22

Fig. 221839d: The citadel (P1) is depicted partially ruined; the Seraiah (P2); the walls that are partially ruined, al-Zaydani mosque without a dome (Roberts, 1842-1849). Note turret T21 leaning towards the east and its lower supporting belt (noted by red arrow). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 25

Fig. 251841: Ruins of Tiberias. The citadel (P1) is depicted as slightly damaged (Munk, 1845). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 32

Fig. 321848: Tiberias from the north, probably drawn somewhere on the hill of the citadel (Lynch, 1849). Prominent features:

Zohar (2017)

Fig. 33

Fig. 331849: the road from Safed leading to Tiberias, the citadel and the walls (Spencer, 1850). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 35

Fig. 351851-52: Tiberias from the south (Van de Velde, 1857). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39c.1870: a photograph probably taken from the hill of the citadel (Bonfils, 1878?). The northern region was not populated. No minaret of al-Bahri mosque, no dome to al-Zaydani. Zohar (2017) |

|

VIII + |

| Minaret Collapse | al-Bahri Mosque (M2)

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2cal-Bahri Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017)

Fig. 35

Fig. 351851-52: Tiberias from the south (Van de Velde, 1857). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39c.1870: a photograph probably taken from the hill of the citadel (Bonfils, 1878?). The northern region was not populated. No minaret of al-Bahri mosque, no dome to al-Zaydani. Zohar (2017) |

|

VI-VII + |

| Vault Destruction - completely or badly destroyed | Vaulted Bazaar (P7)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dremains of the massive vaults in southern Tiberias (noted by red arrow). Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

|

VIII + |

| Damaged Arches | Vaulted Arcs (P8)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017)

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

|

Fig. 20

Fig. 201839b: Tiberias from the south. Note the arched vaults (P8), al-Zaydani mosque and minaret but no dome, the ruined citadel (P1), the Seraiah (P2), a Synagogue (Etz Hayim?, S1), turret T1 in the water, and St. Peter church (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 45

Fig. 451898-1914: (ACPD, 1898-1914b) Zohar (2017) |

|

VI + |

| Collapsed Walls | dwellings

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

|

VIII + |

| Damaged Walls | City Walls (W1-21)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 71828: Tiberias from the south in the book of Leon de Laborde. The latter visited Palestine in 1828 but his book on Syria, Lebanon and Palestine was published only in 1837. The book contains also other artist’s drawings. This drawing was drawn by Marilhat and considered realistic. For example, the number of turrets and location of the citadel are accurate in light of our current knowledge of the Tiberias morphology (Marilhat in de Laborde, 1837) Zohar (2017)

Fig. 15

Fig. 15Prior to 1837: Tiberias from the south (Leitch & Foster, 1855). In my opinion, this is probably a copy of the sketch after Marilhat (de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 17

Fig. 17Before 1837: The drawing portrays Tiberias prior to the earthquake but the date of painting is unresolved. It appears only in the 5th edition of Lindsay (1858). Lindsay visited Palestine twice and only after the earthquake (1837 and 1847) and thus, in my opinion, the drawing is a copy of a previous one, perhaps of Lehoux (de Laborde, 1837) Zohar (2017)

Fig. 35

Fig. 351851-52: Tiberias from the south (Van de Velde, 1857). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

|

VII-VIII + |

| Damaged Walls | Turrets (T1-20)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

|

VII + | |

| Tilted Wall | Leaning Turret (T21)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 31

Fig. 311842f: the leaning turret (T21) and the citadel (P1) (Bartlett, 1850). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 22

Fig. 221839d: The citadel (P1) is depicted partially ruined; the Seraiah (P2); the walls that are partially ruined, al-Zaydani mosque without a dome (Roberts, 1842-1849). Note turret T21 leaning towards the east and its lower supporting belt (noted by red arrow). Zohar (2017) |

|

VI + |

| Collapsed Wall | Main Gate (G1)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 11

Fig. 111835: The town from the north. Note the turrets and the two minarets of al-Zaydani and al-Bahri mosques (Harding, 1835). The drawing was probably copied from the drawing of Marilhat (in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017)

Fig. 18

Fig. 181837: Tiberias from the north, after the voyage of Bernatz and Schubert (Bernatz & Schubert, 1839). The drawing seems to be realistic as prominent features (e.g., W8 and T10) are depicted in similar shape and size as they are today. JW: Gate G1 is 'missing' Zohar (2017) |

|

VIII + |

| Damaged Walls | Southern Gate (G2)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 71828: Tiberias from the south in the book of Leon de Laborde. The latter visited Palestine in 1828 but his book on Syria, Lebanon and Palestine was published only in 1837. The book contains also other artist’s drawings. This drawing was drawn by Marilhat and considered realistic. For example, the number of turrets and location of the citadel are accurate in light of our current knowledge of the Tiberias morphology (Marilhat in de Laborde, 1837) Zohar (2017) |

|

VII + |

| Collapsed Walls | Walls of the Jewish Quarter (JW1-2)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

|

VIII + | |

| Collapsed Walls | Gate of the Jewish Quarter (JG1)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

|

VIII + | |

| Collapsed Walls | Etz-Ha'yim ('Sephardim') Synagogue (S1)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2e

Fig. 2eEtz-Hay’im Synagogue in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

|

VIII + |

| Collapsed Walls | Hasidim' Synagogue (S2)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

|

VIII + |

| Image | Figure | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1aDamage distribution in Ottoman Palestine and its close surroundings caused by the 1837 earthquake (Ambraseys 1997, 2009) and classified by the degree of severity (Zohar et al. 2013); Zohar (2017) |

Figure 1a | Damage Distribution from the 1837 CE Safed Quake | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017) |

Figure 1b | Satellite View of the Old City of Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2aal-Zaydani Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2a | al-Zaydani Mosque in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2bthe Citadel in Tiberias where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2b | the Citadel in Tiberias where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2cal-Bahri Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2c | al-Bahri Mosque in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dremains of the massive vaults in southern Tiberias (noted by red arrow). Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2d | remains of the massive vaults in southern Tiberias (noted by red arrow) |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2e

Fig. 2eEtz-Hay’im Synagogue in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2e | Etz-Hay’im Synagogue in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2f

Fig. 2fone of the southern damaged turrets in Tiberias’s walls. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2f | one of the southern damaged turrets in Tiberias’s walls where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent |

Zohar (2017) |

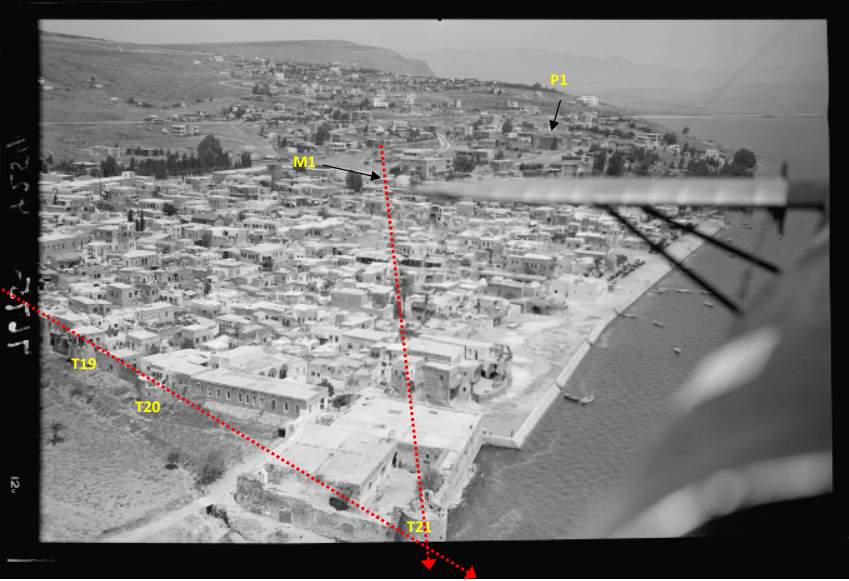

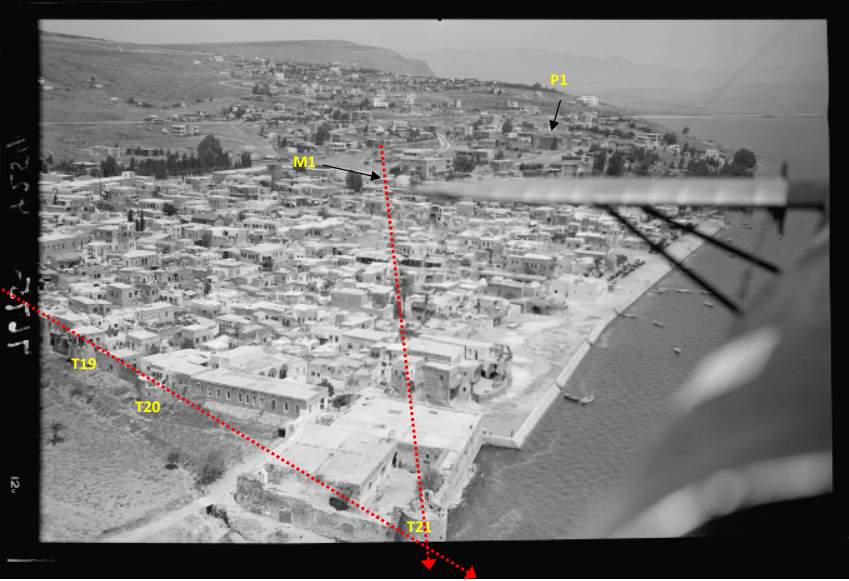

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Visual sources used for reconstructing the landscape. On the right: location and azimuth (angle towards Tiberias from the given point) of the visual sources, i.e., air photos, drawings and photographs (Appendix 1). The map also presents topographic contours. On the left:

Zohar (2017) |

Figure 3 | Visual sources used for reconstructing the landscape | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Detecting Tiberias features in visual sources (example, northern view)

Note the simultaneous detection of the depicted features in Figure C and in the model (Figure D). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 5 | Feature Detection | Zohar (2017) |

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

Zohar (2017) |

Table 1 | Damage Table | Zohar (2017) |

Table 2

Table 2The number of damaged dwellings and structures in the Tiberias quarters classified by an estimated damage degree. Note that the maximal degree of damage in the Jewish quarter is less than that of the Muslim and Christian quarters. See also Figure 8. Zohar (2017) |

Table 2 | Damage in the Quarters | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 6 | Tiberias before the 1837 CE Safed Quake | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 73D view of Tiberias

Prominent features (Table 1) are labelled in black. Note that the majority of Tiberias is located on basalt rocks and note the extensive damage along the fault that crosses the western walls. Zohar (2017) |

Figure 7 | 3D reconstruction of Tiberias before and after the 1837 CE Safed Quake |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 8

Fig. 8The spread of the earthquake damage that resulted in Tiberias by comparing the two HGIS models of before and after the earthquake (Figure 7). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 8 | Map of damage in Tiberias due to 1837 CE Safed Quake | Zohar (2017) |

| Image | Figure | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1aDamage distribution in Ottoman Palestine and its close surroundings caused by the 1837 earthquake (Ambraseys 1997, 2009) and classified by the degree of severity (Zohar et al. 2013); Zohar (2017) |

Figure 1a | Damage Distribution from the 1837 CE Safed Quake | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1bGeneral overview of the old city of Tiberias. Zohar (2017) |

Figure 1b | Satellite View of the Old City of Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2aal-Zaydani Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2a | al-Zaydani Mosque in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2bthe Citadel in Tiberias where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2b | the Citadel in Tiberias where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2cal-Bahri Mosque in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2c | al-Bahri Mosque in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2d

Fig. 2dremains of the massive vaults in southern Tiberias (noted by red arrow). Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2d | remains of the massive vaults in southern Tiberias (noted by red arrow) |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2e

Fig. 2eEtz-Hay’im Synagogue in Tiberias. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2e | Etz-Hay’im Synagogue in Tiberias | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2f

Fig. 2fone of the southern damaged turrets in Tiberias’s walls. Photograph: Motti Zohar, 2015 Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2f | one of the southern damaged turrets in Tiberias’s walls where 1837 earthquake damage is apparent |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Visual sources used for reconstructing the landscape. On the right: location and azimuth (angle towards Tiberias from the given point) of the visual sources, i.e., air photos, drawings and photographs (Appendix 1). The map also presents topographic contours. On the left:

Zohar (2017) |

Figure 3 | Visual sources used for reconstructing the landscape | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Detecting Tiberias features in visual sources (example, northern view)

Note the simultaneous detection of the depicted features in Figure C and in the model (Figure D). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 5 | Feature Detection | Zohar (2017) |

Table 1

Table 1Localities in Tiberias reported to be damaged during the 1837 earthquake.

Zohar (2017) |

Table 1 | Damage Table | Zohar (2017) |

Table 2

Table 2The number of damaged dwellings and structures in the Tiberias quarters classified by an estimated damage degree. Note that the maximal degree of damage in the Jewish quarter is less than that of the Muslim and Christian quarters. See also Figure 8. Zohar (2017) |

Table 2 | Damage in the Quarters | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Tiberias and its major features prior to the 1837 earthquake (for notations see Table 1). The city interior was compiled using pre-1837 drawings (Appendix 1), maps of Palestine (1938), PEF (1918), Burckhardt (1822) and historical accounts (Mariti 1791, Clarke 1810–1823, Light 1818, Turner 1820, Buckingham 1822, Richardson 1822, Scholz 1822, Wilson 1823, Carne 1826, Jowett 1826, Maden 1829, Madox 1834, Horne 1836, Stephens 1839, Kinglake 1848). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 6 | Tiberias before the 1837 CE Safed Quake | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 73D view of Tiberias

Prominent features (Table 1) are labelled in black. Note that the majority of Tiberias is located on basalt rocks and note the extensive damage along the fault that crosses the western walls. Zohar (2017) |

Figure 7 | 3D reconstruction of Tiberias before and after the 1837 CE Safed Quake |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 8

Fig. 8The spread of the earthquake damage that resulted in Tiberias by comparing the two HGIS models of before and after the earthquake (Figure 7). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 8 | Map of damage in Tiberias due to 1837 CE Safed Quake | Zohar (2017) |

| Image | Figure | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 1

Fig. 11681: Tiberias walls before the reconstruction of Dahir al-Umar. Note the church of St. Peter (C1) and the probable location of the Jewish quarter (de-Bruyn, 1702) Zohar (2017) |

Figure 1 | Painting of Tiberias in 1681 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 2

Fig. 21799: Tiberias at the end of the 18th century as mapped by Jacotin for military purposes. Note the roads leading to the city and the fact that there is no road entering Tiberias from the north. See also the location of the main (G1) and southern (G2) gates (Jacotin, 1799) Zohar (2017) |

Figure 2 | Map of Tiberias in 1799 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 31810-12: Tiberias at the beginning of the 19th century (in brackets - identification according to Table 3)

(Burckhardt, 1822) Note that Burckhardt confuses the number of turrets (counts 25 instead of 21) and neglects a northern turret (T1) Zohar (2017) |

Figure 3 | Map of Tiberias in 1810-1812 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 4

Fig. 41814: al-Zaydani mosque drawn from close range within the city itself (Light, 1818). Note the relatively large dome also present in other pre-1837 drawings (e.g., Buckingham, 1822; Marilhat in de Laborde, 1837; Wilson, 1823). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 4 | al-Zaydani Mosque in 1814 CE compared to ~2016 CE |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 5

Fig. 51816: Buckingham draws the citadel (P1) as having only one turret but the other turrets (e.g., T10, T16, T20, T21) seems to be drawn correctly. Note the al-Zaydani mosque (M1) (Buckingham, 1822). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 5 | Painting of Tiberias in 1816 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 6

Fig. 61822: al-Zaydani (M1) and al-Bahri (M2) mosques. The minaret of al-Zaydani is portrayed relatively high above the dome. Note the possible identification of St. Peter church (C1) (Wilson, 1823). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 6 | Painting of Tiberias in 1822 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 7

Fig. 71828: Tiberias from the south in the book of Leon de Laborde. The latter visited Palestine in 1828 but his book on Syria, Lebanon and Palestine was published only in 1837. The book contains also other artist’s drawings. This drawing was drawn by Marilhat and considered realistic. For example, the number of turrets and location of the citadel are accurate in light of our current knowledge of the Tiberias morphology (Marilhat in de Laborde, 1837) Zohar (2017) |

Figure 7 | Painting of Tiberias in 1828 CE compared to ~2016 CE |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 8

Fig. 81828: Tiberias from the west (de Laborde, 1837). Note the accuracy in counting the turrets: six (T16-T21) at the south of the city and six (T10‐T15) at its western side. Zohar (2017) |

Figure 8 | Painting of Tiberias in 1828 CE compared to ~2016 CE |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 9

Fig. 91832: The city drawn from the north (Russell, 1832). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 9 | Painting of Tiberias in 1832 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 10

Fig. 101833: Sketch of Tiberias drawn from northeast of the city. Despite the exaggerated topography one can detect prominent features, e.g., the western main gate (G1) and the surrounding turrets. Note that two minarets appear, probably of the al-Zaydani (M1) and al-Bahri (M2) mosques (Skinner, 1836). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 10 | Painting of Tiberias in 1833 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 11

Fig. 111835: The town from the north. Note the turrets and the two minarets of al-Zaydani and al-Bahri mosques (Harding, 1835). The drawing was probably copied from the drawing of Marilhat (in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 11 | Painting of Tiberias in 1835 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 12

Fig. 12Prior to 1837 (1835?): Tiberias and the Sea of Galilee. No significant identification of features (Thomas Allom in Carne, 1838). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 12 | Painting of Tiberias Prior to 1837 CE (1835?) |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 13

Fig. 13Prior to 1837: Tiberias from the south (Lindsay, 1858). The drawing portrays Tiberias prior to the earthquake but the date is unresolved. The drawing appears only in the 5th edition of the book of Lord Lindsay published in 1858. However, Lindsay visited Palestine only after the earthquake, in 1837 and 1847. Thus, in my opinion, it was copied from a previous drawing, perhaps from Marilhat (de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 13 | Painting of Tiberias Prior to 1837 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 14

Fig. 14Prior to 1837: Tiberias from the north (Leitch & Foster, 1855). In my opinion, this is probably a copy of the sketch after Marilhat (de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 14 | Painting of Tiberias Prior to 1837 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 15

Fig. 15Prior to 1837: Tiberias from the south (Leitch & Foster, 1855). In my opinion, this is probably a copy of the sketch after Marilhat (de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 15 | Painting of Tiberias Prior to 1837 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 16

Fig. 161837: Tiberias after the earthquake drawn from the south. Note the damage to the citadel (P1), to the walls and to its turrets (T4‐T17). The Jewish quarter is depicted as partially destroyed while in the Muslim and Christian quarters there are hardly any standing dwellings. The drawing seems to be realistic: parts of the walls (e.g., W7b, W8a, and W16) and turrets (e.g., T8, T10 and T16) that were drawn as not destroyed still exist till today (Lehoux in de Laborde, 1837). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 16 | Painting of Tiberias in 1837 CE after the earthquake compared to ~2016 CE |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 17

Fig. 17Before 1837: The drawing portrays Tiberias prior to the earthquake but the date of painting is unresolved. It appears only in the 5th edition of Lindsay (1858). Lindsay visited Palestine twice and only after the earthquake (1837 and 1847) and thus, in my opinion, the drawing is a copy of a previous one, perhaps of Lehoux (de Laborde, 1837) Zohar (2017) |

Figure 17 | Painting of Tiberias before 1837 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 18

Fig. 181837: Tiberias from the north, after the voyage of Bernatz and Schubert (Bernatz & Schubert, 1839). The drawing seems to be realistic as prominent features (e.g., W8 and T10) are depicted in similar shape and size as they are today. Zohar (2017) |

Figure 18 | Painting of Tiberias in 1837 CE compared to ~2016 CE |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 19

Fig. 19. 1839a: Damage to the citadel and walls. Note the completeness of the Seraiah (P2) and the presence of the minaret of al-Zaydani mosque (M1) (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 19 | Painting of Tiberias in 1839 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 20

Fig. 201839b: Tiberias from the south. Note the arched vaults (P8), al-Zaydani mosque and minaret but no dome, the ruined citadel (P1), the Seraiah (P2), a Synagogue (Etz Hayim?, S1), turret T1 in the water, and St. Peter church (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 20 | Painting of Tiberias in 1839 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 21

Fig. 211839c: The western walls are drawn as partially ruined (Roberts, 1842-1849). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 21 | Painting of Tiberias in 1839 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 22

Fig. 221839d: The citadel (P1) is depicted partially ruined; the Seraiah (P2); the walls that are partially ruined, al-Zaydani mosque without a dome (Roberts, 1842-1849). Note turret T21 leaning towards the east and its lower supporting belt (noted by red arrow). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 22 | Painting of Tiberias in 1839 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 23

Fig. 231840: Tiberias from the south, probably from a spot close to the thermal baths. The depiction of the city is vague but one can detect the citadel (P1) drawn as slightly damaged and few turrets (T1, T2 and T21) (Egerton, 1841) Zohar (2017) |

Figure 23 | Painting of Tiberias in 1840 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 24

Fig. 241841: Tiberias from the south by Barnes (1841). Although few features are depicted differently, it seems that this drawing was copied from the drawing of Egerton (1841). Yet, note that in this drawing the lean of T1 and T2 is clearly seen. Zohar (2017) |

Figure 24 | Painting of Tiberias in 1841 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 25

Fig. 251841: Ruins of Tiberias. The citadel (P1) is depicted as slightly damaged (Munk, 1845). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 25 | Painting of Tiberias in 1841 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 26

Fig. 261842a: Tiberias and its citadel in a drawing drawn from the north (Bartlett in Stebbing, 1847). Note the similarity of T4 and T5 to their recent state (upper left corner) and the accuracy of the hatch (red square) as drawn by Bartlett Zohar (2017) |

Figure 26 | Painting of Tiberias in 1842 CE compared to ~2016 CE |

Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 27

Fig. 271842b: Tiberias drawn from the thermal baths. Note the four turrets that erect above the others (probably ruined) and remains of damaged walls (Bartlett in Stebbing, 1847). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 27 | Painting of Tiberias in 1842 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 28

Fig. 281842c: Tiberias from the west. Several turrets seem to be relatively higher than the others and in the western walls large breaches appear (Bartlett in Stebbing, 1847). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 28 | Painting of Tiberias in 1842 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 29

Fig. 291842d: Tiberias view drawn from the citadel of Safed. Note the citadel of Tiberias (P1) (Bartlett in Stebbing, 1847). Zohar (2017) |

Figure 29 | Painting of Tiberias in 1842 CE | Zohar (2017) |

Fig. 30