| Heshbon |

possible |

≥ 8 |

Stratum 15 Destruction Layer (Mitchel, 1980) - 2nd - 1st century BCE

Mitchel (1980:21) noted chronological difficulties dating Stratum 15.

Though evidence for Stratum 15 occupation at Tell Hesban occurs in the form of ceramic remains found across the entire site,

evidence of stratigraphic value is greatly limited in quantity and extent.

Mitchel (1980:47) noted that there was limited evidence

for destruction and/or abandonment in Stratum 15 though most of the evidence was removed by subsequent building activities particularly in Stratum 13. Destruction layers were

variously described as debris, a rubble layer, or tumble. Due to slim evidence ,

Mitchel (1980:70)

did not form firm conclusions about the nature of the end of Stratum 15

The transition to Stratum 14 may be characterized as a smooth one, although the evidence is slim. There is currently no evidence

of a destroying conflagration at the end of Stratum 15. In fact, I do not believe it is likely that we shall know whether Stratum 15

Heshbon was simply abandoned or destroyed by natural or human events.

Stratum 14 Earthquake (Mitchel, 1980) - 1st century BCE - 2nd century CE

Mitchel (1980) identified a destruction layer in Stratum 14

which he attributed to an earthquake. Unfortunately, the destruction layer is not precisely dated. Using some assumptions,

Mitchel (1980) dated the

earthquake destruction to the 130 CE Eusebius Mystery Quake,

apparently unaware at the time that this earthquake account may be either

misdated as suggested by Russell (1985) or mislocated as

suggested by Ambraseys (2009).

Although Russell (1985) attributed the destruction layer

in Stratum 14 to the early 2nd century CE Incense Road Quake, a number of

earthquakes are possible candidates including the 31 BCE Josephus Quake.

Mitchel (1980:73) reports that a

majority of caves used for dwelling collapsed at the top of

Stratum 14 which could be noticed by:

bedrock surface channels, presumably for directing run-off water into storage facilities, which

now are totally disrupted, and in many cases rest ten to twenty degrees

from the horizontal; by caves with carefully cut steps leading down into

them whose entrances are fully or largely collapsed and no longer

usable; by passages from caves which can still be entered into formerly

communicating caves which no longer exist, or are so low-ceilinged or

clogged with debris as to make their use highly unlikely — at least as

they stand now.

Mitchel (1980:73) also noticed

that new buildings constructed in Stratum 13 were leveled over a jumble of broken-up bedrock .

Mitchel (1980:95) reports that Areas B and D

had the best evidence for the massive bedrock collapse - something he attributed to the "softer" strata in this area, more prone to

karst features and thus easier to burrow into and develop underground dwelling structures.

Mitchel (1980:96) reports discovery of a coin

of Aretas IV (9 BC – 40 CE) in the fill of silo D.3:57 which he suggests was placed as part of reconstruction

after the earthquake. Although Mitchel (1980:96)

acknowledges that this suggests that the causitive earthquake was the 31 BCE Josephus Quake,

Mitchel (1980:96)

argued for a later earthquake

based on the mistaken belief that the

31 BCE Josephus Quake had an epicenter in the Galilee.

Paleoseismic evidence from the Dead Sea, however, indicates that the

31 BCE Josephus Quake had an epicenter in the vicinity of the

Dead Sea relatively close to Tell Hesban. Mitchel (1980:96-98)'s

argument follows:

The filling of the silos, caves, and other broken—up bedrock installations at the end of the Early Roman period was apparently carried out

nearly immediately after the earthquake occurred. This conclusion is based on the absence of evidence for extended exposure before filling

(silt, water—laid deposits, etc.), which in fact suggests that maybe not even one winter's rain can be accounted for between the earthquake

and the Stratum 13 filling operation. If this conclusion is correct, then the Aretas IV coin had to have been introduced into silo D.3:57

fill soon after the earthquake. which consequently could not have been earlier than 9 B.C.

The nature of the pottery preserved on the soft, deep fills overlying collapsed bedrock is also of significant importance to my argument

in favor of the A.D. 130 earthquake as responsible for the final demise of underground (bedrock) installations in Areas B and D.

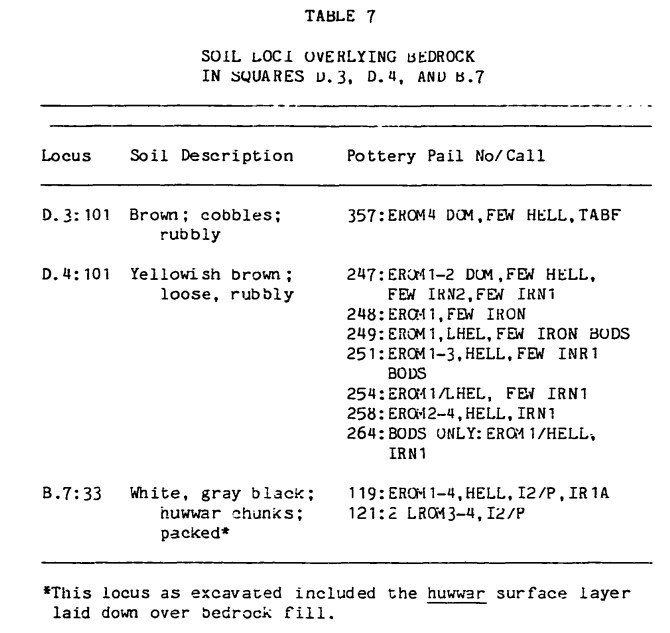

Table 7

provides a systematic presentation of what I consider to be the critical ceramic evidence from loci in three adjacent squares,

D.3, D.4, and B.7. The dates of the latest pottery uniformly carry us well beyond the date of the earthquake which damaged Qumran,

down, in fact, closer to the end of the 1st century A.D. or the beginning of the 2nd.

In addition to these three fill loci, soil layer D.4:118A (inside collapsed cave D.4:116 + D.4:118) yielded Early Roman I-III sherds,

as well as two Late Roman I sherds (Square D.4 pottery pails 265, 266). Contamination of these latter samples is possible, but not

likely. I dug the locus myself.

Obviously, this post-31 B.C. pottery could have been deposited much later than 31 B.C.. closer, say, to the early

2nd century A.D., but the evidence seems to be against such a view. I personally excavated much of locus D.4:101

(Stratum 13). It was a relatively homogeneous, unstratified fill of loose soil that gave all the appearances of

rapid deposition in one operation. From field descriptions of the apparently parallel loci in Squares D.3 and B.7.

I would judge them to be roughly equivalent and subject to the same interpretation and date. And I repeat, the

evidence for extended exposure to the elements (and a concomitant slow, stratified deposition) was either missed

in excavation, not properly recorded, or did not exist.

This case is surely not incontrovertible but seems to me to carry the weight of the evidence which was excavated at Tell Hesban.

Mitchel (1980:100)'s 130 CE date for

the causitive earthquake rests on the assumption that the "fills" were deposited soon after bedrock collapse. If one discards this assumption,

numismatic evidence and ceramic evidence suggests that the "fill" was deposited over

a longer period of time - perhaps even 200+ years - and the causitive earthquake was earlier. Unfortunately, it appears that the terminus ante quem

for the bedrock collapse event is not well constrained. The terminus post quem appears to depend on the date for lower levels of Stratum 14 which seems to have

been difficult to date precisely and underlying Stratum 15

which Mitchel (1980:21) characterized as

chronologically difficult.

|