756 CE BY NO MEANS MILD QUAKE(S)

March 756 CE

by Jefferson Williams

Introduction & Summary

The By No Means Mild earthquake gets its name because in some translations of Theophanes he describes it as an earthquake that was "by no means mild". Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre, who appears to be a contemporaneous source, describes the same earthquake but provides more details than Theophanes - stating that three villages on the north Mesopotamian Khabur River collapsed and many other places in Jazira were destroyed. Theophanes merely specifies that the earthquake struck Syria and Palestine. The earthquake likely struck in March 756 CE. Although calendaric inconsistencies in Thephanes' entry indicate it could have struck in the years 756, 757, 758, or, less likely, 759 CE, Halley's comet appeared in 760 CE and was described by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre and Theophanes 4 years after their earthquake accounts - thus fixing the date of this earthquake to 756 CE. There is a slight disagreement between Pseudo-Dionysius and Theophanes on the exact day. Pseudo-Dionysius says it struck on the 3rd of March while Theophanes says it struck on the 9th. Pseudo-Dionysius also says that it struck in the middle of the night and on a Tuesday. Arabic sources speak of an earthquake which struck around 756 CE in Mopsuestia which could be related to the event described by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre and Theophanes. There is also a Muslim tradition that the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem was destroyed by an earthquake that, based on textual sources, struck between 754 and 785 CE although a more likely date range may be between 754 and 775 CE. Although some have attributed this seismic destruction to the By No Means Mild Quake, this attribution has two problems. The epicentral region that can be derived from Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre's account seems too far away to have destroyed Al Aqsa and the date for the By No Means Mild Quake may be too early.Intensity Estimates

Textual Evidence

| Text (with hotlink) | Original Language | Biographical Info | Religion | Date of Composition | Location Composed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre | Syriac |

Biography

|

Eastern Christian | 750-775 CE | Zuqnin Monastery | Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre described a powerful, terrible and dreadful earthquakeon Tuesday 3 March 756 CE which took place in the middle of the night in the land of the Jazira. Three villages on the Khabur collapsed, and many people perished inside them, like grapes in a wine press. Many other places were also destroyed by this earthquake. 3 March 756 CE fell on a Wednesday. |

| Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre, Theophanes, and the Comet of 760 CE | Halley's Comet appeared in May and June of 760 CE and was both observed and recorded by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre and Theophanes. This precise time marker can be used to anchor the year of the By No Means Mild Quake in both accounts to 756 CE. | |||||

| Article by Neuhauser et al (2021) on the Comet of 760 CE | Neuhauser et al (2021) identified Halley's Comet (1P/Halley) as the comet described by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre (Chronicle of Zuqnin), Theophanes, Agapius of Menbj, Nu'aym ibn Ḥammmad, Michael the Syrian, and Chinese, Japanese and Korean sources. They performed astronomical calculations (least squares fitting of Keplerian orbital solutions) to fit "corrected" historical reports paying close attention to the month and day of astronomical observations in the sources. Despite chronological inconsistencies (year and month) among the various sources (possibly due to scribal errors) which they had to "correct", they identified the comet as 1P/Halley and obtained a precise perihelion time (760 May 19.1 ± 1.7) and an inferior conjunction between the comet and Sun (June 1.8) which is about one day different from a previously published orbit (760 May 31.9, Yeomans and Kiang, 1981). Based on their orbital model and philological arguments, Neuhauser et al (2021:7) suggest that Pseudo-Dionysius drew the comet, 3 stars (Ari), and two planets (Mars and Saturn) in his text in the early morning (before sunrise) on 25 May 760 CE. | |||||

| Theophanes | Greek |

Biography

|

Orthodox (Byzantium) | 800-814 CE | Vicinity of Constantinople | Theophanes (c. 758/60-817/8) wrote that on 9 March 756 CE an earthquake that was by no means mildstruck Palestine and Syria. |

| al-Masudi | Arabic |

Biography

|

Muslim - Shi’ite | mid-10th century CE | Egypt ? | al-Masudi wrote that Caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775-785 CE) rebuilt Jerusalem, which had been devastated by earthquakes |

| Muslim Writers - Description of Syria including Palestine by al-Maqdisi | Arabic |

Biography

|

Muslim | ca. 985 CE | Jerusalem ? | In "Description of Syria including Palestine", native Jerusalemite

al-Maqdisi wrote that earthquakes (plural) threw down the main building

of Al Aqsa Mosque, except for the Mihrab, in the days of the

Abbasids (who began their rule on 25 Jan. 750 CE). The Caliph of the dayfinanced rebuilding by having each Governor build a colonnade. The days of the Abbasides dates this to after 25 January 750 CE. |

| Muslim Writers - The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions by al-Maqdisi | Arabic |

Biography

|

Muslim | ca. 985 - 990 CE | Jerusalem ? | In his famous book "The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions", thought to have been written

after "Description of Syria including Palestine", native Jerusalemite al-Maqdisi wrote

that in the days of the ‘Abbäsides an earthquake [singular] occurred which threw down most of the main building [Al Aqsa Mosque]; all, in fact, except the part around the mihrab. The days of the Abbasides dates this to after 25 January 750 CE and since the destruction is described as total (the entire mosque except for the mihrab) and not just two walls, this appears to refer to the 2nd earthquake that struck Al-Aqsa after the Holy Desert Quake in 749 CE. This passage is almost identical to what al-Maqdisi wrote in "Description of Syria including Palestine" except that in "The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions", al-Maqdisi refers to one earthquake while in "Description of Syria including Palestine", he refers to earthquakes (plural). |

| Ibn al-Athir | Arabic |

Biography

|

Sunni Muslim | ~ 1200 - 1231 CE | Mosul | According to Taher (1996), Ibn al-Athir reports earthquakes in al-Massîsa (Mopsuestia) in A.H. 140 (25 May 757 - 13 May 758 CE). According to Ibn al-Athir, the surrounding wall was weakened. Reconstruction of the wall and construction of a large mosque was ordered by Caliph al-Mansûr. |

| Ibn al-Adim (aka Kemal ad-Din) | Arabic |

Biography

|

Muslim | before 1260 CE | Aleppo or Cairo | Ibn al-Adim (aka Kemal ad-Din) wrote that

Masisah (Mopsuestia) suffered from the earthquake of the year A.H. 140 (25 May 757 - 13 May 758 CE). |

| Earthquake in Mopsuestia in A.H. 139 according to an unknown Muslim source | Arabic | Muslim | Le Strange (1905:130-131), without citing a source, wrote that

Massisah (Mopsuestia) had been partially destroyed by earthquake in [A.H.] 139 (5 June 756 to 24 May 757 CE). |

|||

| Jamal ad Din Ahmad | Arabic |

Biography

|

Muslim | 1351 CE | Jerusalem ? | Jamal ad Din Ahmad wrote that the western and eastern parts of Al Aqsa mosque were damaged during the

earthquake of A.H. 130.

Caliph Al-Mansur (r. 754-775 CE ordered repairs made.

The repairs were financed by stripping plates of silver and gold which had covered the Mosque's doors.

A subsequent earthquake caused the repaired mosque to fall to the ground. The mosque was still in ruins when Caliph Al-Mahdi (r. 775-785 CE) ordered a rebuild but to different dimensions. |

| Mujir al-Din | Arabic |

Biography

|

Hanbali Sunni Muslim | ca. 1495 CE | Jerusalem | Mujir al-Din described an earthquake which damaged Al Aqsa Mosque in A.H. 130 (11 Sept. 747 - 30 Aug. 748 CE) which led to a repair during the reign of Caliph Al-Mansur (ruled 754-775 CE). A second undated earthquake is described as destroying the repaired Mosque leading to a second reconstruction to different dimensions during the reign of Caliph Al-Mahdi (ruled 775-785 CE). |

| Text (with hotlink) | Original Language | Biographical Info | Religion | Date of Composition | Location Composed | Notes |

- Part 4

- from Harrak (1999:197)

- Map showing the location of the Khabur River

Syria 2004 CIA map

Syria 2004 CIA map

Wikipedia - קרלוס הגדול - CC BY-SA 3.0

The earth shall totter exceedingly,2

the earth shall shake violently,

and it shall sway like a hut.

This is what our sins are able to do: to shake the ground beneath us!

| Year | Reference | Corrections | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| middle of the night 2 or 3 March 756 CE |

|

none |

-

Three villages on the Khabur collapsed, and many people perished inside them, like grapes in a wine press.

Syria 2004 CIA map

Syria 2004 CIA map

Wikipedia - קרלוס הגדול - CC BY-SA 3.0 Many other places were also destroyed by this earthquake

- on the Khabur

- Many other places

Pseudo-Dionysius states that the earthquake struck on a Tuesday in the middle of the night on the 3rd of Adar in what appears to be 756 CE. When one makes Julian day calculations to arrive at the day of the week, 3 Adar (March) 756 CE falls on a Wednesday. This calculation is valid for Universal Time - i.e. the time in Greenwich, England - the same time zone as London. Northern Syria and Mesopotamia are 2 or 3 hours ahead of London depending on location (longitude). Below is a table of days of the week in Universal Time for 3 March (Pseudo-Dionysius) and 9 March (Theophanes) in 756 and 757 CE. Days began at sundown in the Syriac version of the A.G. calendar used by Pseudo-Dionysius (Sebastian Brock, personal communication 2022).

| Date | Day of the Week |

|---|---|

| 3 March 756 CE | Wednesday |

| 3 March 757 CE | Thursday |

| 9 March 756 CE | Tuesday |

| 9 March 757 CE | Wednesday |

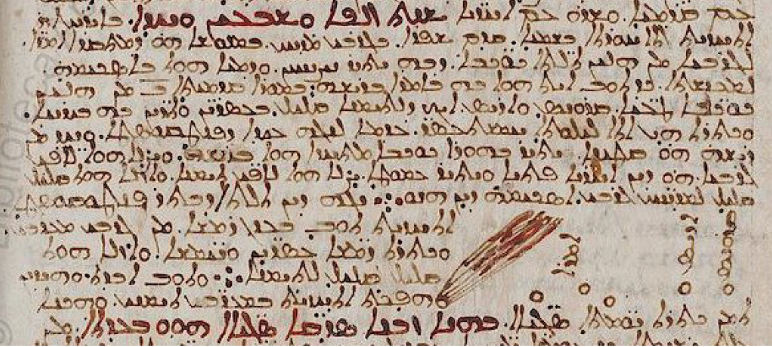

Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre drew a picture of a comet in 760 CE which suggests that Harrak (1999) is correct that Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre is a contemporaneous source. This also assists in deciphering the chronology of the By No Means Mild Quake. In Pseudo-Dionysius' entry for A.G. 1071, we can read in Harrak (1999:198)'s translation:

759-760 The year one thousand and seventy-one: In the month of Adar (March), a shining sign was seen in the sky1 before dawn on the northeast side which is called Ram in the Zodiac, to the north of the three most shining stars. Its shape resembled a broom. On the twenty-second day of the month, it was still in the Ram at its head, in the first degree (of the Zodiac circle), the second after the wandering stars Kronos and Ares,2 somehow slightly to the south. The sign remained for fifteen nights, to the eve of the Pentecost feast. At one of its ends, which was narrow and more shining*3 a star was seen and was turning toward the North. The other side, which was large and darker, was turning toward the South. The sign was moving little by little toward the Northeast. This was its form (Vat.sir.162 137r-136v):Hayakawa et al (2017:11-12) suggests that this was a description of Halley's comet.

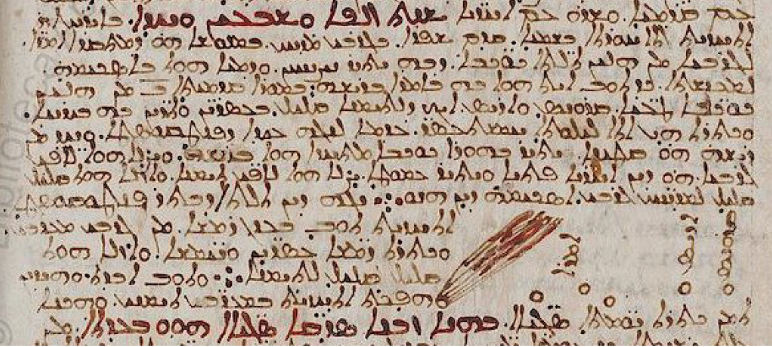

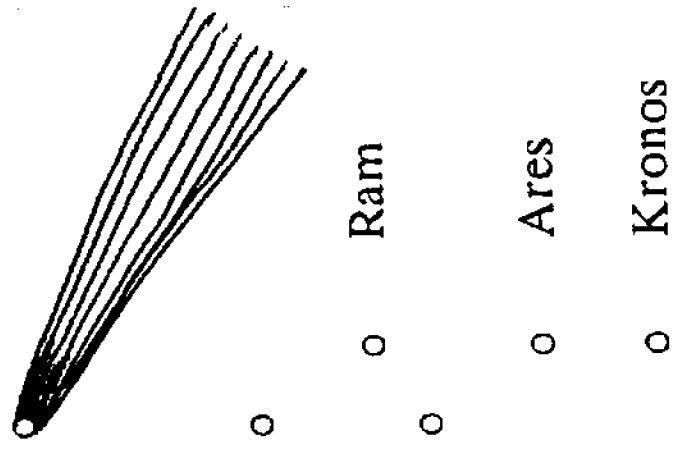

Left - original drawing of a comet in 760 CE by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre (Vat.sir.162 137r-136v)

Right - redrawn comet by Harrak (1999:198)

On the eve of the third day after Pentecost*, the sign was seen again in the evening in the Northwest, and it remained for twenty five evenings. It moved little by little to the South and then it disappeared. Then it reappeared in the southwest, where it remained in this way for many days.

During this time, many schisms took place in the church because of leadership. The eastern monasteries made John Patriarch, while neither the cities of the Jazira nor all the monasteries approved him. The people of the West and Mosul approved George. Because of this the entire Church became troubled.4Footnotes1 A brief mention in Theophanes 431: A.M. 6252 (760-761).

2 Following Ptolemy, the ancients believed that there were seven "wandering stars", Syriac | | (i.e. planets): The Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars (=Ares), Jupiter and Saturn (= Kronos), all revolving around the earth.

3 | | : See Manna, Dalil, 54, for its meaning.

4 See above pp. 193ff and 216ff.

This should be the record of Halley’s Comet, which has an orbital period of about 75 years. According to Yeomans and Kiang (1981), Halley’s Comet was at perihelion on day 20.671 (UT) of May 760 CE. The comet was also observed by Chinese astronomers. There is a record in JiùTángshū (旧唐书), one of the official histories of the Táng Dynasty, stating that the comet was first observed on May 16, 760 CE within Aries and continued to be visible for about 50 days (JiùTángshū (旧唐书), Astronomy II: p. 1324). The observed period and the association with Aries are consistent between the Chinese and the Syriac records.The discrepancy in months was discussed by Hayakawa et al (2017:11)

Firstly, we discuss its date and time. According to the text, the event was in the month ādār (March), so it should be March of 760 CE. The event was first seen on the 22nd of the month, remained 15 nights until the dawn of the Pentecost feast, appeared again on the third day after Pentecost, and remained another 25 days. From the text, it is also clear that the event was seen during the night. The time and the duration of the event as well as its shape, which we discuss below, are consistent with the interpretation that it was a large comet. The date of the event, on the other hand, is rather confusing. It is written that this event was seen on March 22 and lasted 15 nights up to the eve of Pentecost, but the date of the Pentecost of that year is May 25 (Grumel, 1958), so it cannot be 15 nights after March 22. A probable explanation for this inconsistency is a miswriting of MayIf we accept that Pseudo-Dionysius dates this to May, the Macedonian reckoning gives the correct year consistent with what Sebastian Brock (personal communication - 2021) relates - that Macedonian reckoning with a New Year starting on 1 October would be the standard for Syriac sources of the time.ܐܝܪ(eyar)as Marchܐܕܪ(adar)in the manuscript as there only one letter difference between them in the Syriac letter system. After a short break, this event reappeared on the eve of the third day after Pentecost and lasted another 25 nights. Thus, we conclude that this event started around 22 May 760 CE and lasted until early July of 760 CE.

| Year | Reference | Corrections | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 760 CE | A.G. 1071 | none | Macedonian Reckoning dates A.G. 1071 to 1 October 759 - 30 September 760 CE |

| 761 CE | A.G. 1071 | none | Babylonian Reckoning dates A.G. 1071 to 2 April 760 - 1 April 761 CE |

[A.M. 6252, AD 759/60]Theophanes' regnal years and his A.M.a dates are all consistently 4 years apart from the comet of 760 CE. Thus, it would appear that Halley's comet of 760 CE also fixes Theophanes earthquake date to 756 CE. By extension, this also indicates that Theophanes' date for the Talking Mule Quake (one of the Sabbatical Year Quakes) in A.M.a 6241 places that earthquake in 749 CE....

- Constantine, 20th year

- Abdelas, 6th year

- Paul, 6th year

- Constantine, 7th year

II In the same year a very bright comet appeared for ten days in the east and another twenty-one days in the west. II

Cook, D. (1999). "A Survey of Muslim Material on Comets and Meteors." Journal for the History of Astronomy 30(2): 131-160. - open access

Hayakawa, H., et al. (2016). "The earliest drawings of datable auroras and a two-tail comet from the Syriac Chronicle of Zuqnin."

Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 69. - open access

Neuhäuser, D. L., et al. (2021). "Orbit determination just from historical observations? Test case:

The comet of AD 760 is identified as 1P/Halley." Icarus 364: 114278. - open access

Grumel (1958:310) lists the Easter date as Sunday 6 April in 760 CE. Since the Pentecost is exactly 7 weeks after Easter, this would indicate that the Pentecost was on

Sunday 25 May in 760 CE.

Julian Calendar in 760 CE

Neuhauser et al (2021:7) report that the text of Pseudo-Dionysius

reports that "the white sign" (i.e. the comet) was seen for "15 nights until dawn of the feast of Pentecost".

Pentecost takes place on a Sunday and in AG 1071, most Christian churches (including churches under the Byzantine Patriarchate)

celebrated Pentecost on 760 May 25, but some eastern churches celebrated Pentecost one week later on June 1

(Neuhauser et al, 2021:7). This, according to

Neuhauser et al (2021:7), is further evidence that

Iyyar (May) was the correct month for the comet not Adar (March).

Neuhauser et al (2021:7) further noted that:

The reason for the two different Pentecost (and Easter) dates in AD 760 is the difference between two ecclesiastical Easter calendars: in AD 760, the first computed (cyclic) full moon after the start of spring (defined for March 21 at the AD 325 Council of Nicaea) was on Saturday Apr 5 according to the 532-year cycle constructed by Irion in AD 562 for the Byzantine Patriarchate (based on a previous 200-year cycle by Andreas of Byzantium for AD 353-552), so that the Byzantines celebrated Easter on Apr 6 (like also the Roman church following the 532-year Easter calendar by Dionysius Exiguus starting in AD 532), while the Armenian, Jacobite, and Nestorian churches followed a different 532-year Easter table, namely the Armenian scholar Anania Siralcaci's (AD 610-685) reform (early AD 660ies) of Andreas' Easter table, according to which the paschal full moon in AD 760 would be on Sunday Apr 6, so that Easter has to be dated Apr 13 (see Sanjian, 1966, Mosshammer, 2008, pp. 257-277). This dispute is also reflected in the Chronicle of Zuqnin (Harrak, 1999):The year (SE) 1070: Lent was confused. Some of the Easterners introduced Lent on the 18th of: Sebat (Feb) and ended it on the 6th of Islisdn (Apr). Others introduced Lent on the 25th of Sebat (Feb) and ended it on the 13th of Nisan (Apr). All of the Christians were confused, when in one place they celebrated Easter, in another place Palm Sunday; in one place it was Passion week, in another place Easter.(With the above expression "some of the Easterners" for the other churches, our author probably refereed to the Byzantine Patriarchate or other churches west of the Euphrates.)

Our Chronicle reported the Easter dating problem for SE 1070, i.e. AD 758/9; in AD 759, Easter Sunday was on April 22, in AD 760 on April 6 or 13 (see above); hence, the above given end date of lent (Apr 6 or 13) points to AD 760; the given introduction of lent on Feb 18 or 25 would be a Monday in 760, i.e. the correct weekday for the start of lent in the Syriac churches (where there is no Ash Wednesday). There is also a brief mention of this problem by Theophanes, who dates it to AD 760. Hence, all the evidence points to AD 760 for the report on the Easter dating problem misdated to AD 759 in the Chronicle of Zuqnin. The same problem also happened in AD 570 and 665 (Mosshammer, 2008, pp. 276-277).14

The monastery of Zuqnin belonged to the Syriac Orthodox church, informally known as the Jacobite Church; this is known, because our chronicler listed bishops and patriarchs, which were also listed by the 12th century Michael the Syrian (e.g. Chabot, 1899-1910), who clearly identified them as to belong to the Syriac Orthodox patriarchate (Jacobite). Hence, it is clear that Easter was on Apr 13 and Pentecost on June 1 at the monastery of Zuqnin: since it is reported that the comet was seen "for fifteen nights, until dawn of the feast of Pentecost", it was first detected on May 18 "before early twilight". This is well consistent with the fact that the Chinese sources give May 17 for the first detection (Section 3.1).Footnotes14 The Chronicle of Zuqnin does not report any Easter dating problems for AD 570 nor 665; this problem, called "crazatik" or "Erroneous Easter", was resolved only in AD 1824 (Mosshammer, 2008, p. 277). Our Chronicle narrates one other Easter confusion for SE 857 (i.e. Easter AD 546, but correct year is AD 547, see Mosshammer, 200E, p. 256), when three different dates for lent and Easter are mentioned to have been followed by different parts of the population. For a discussion of the Easter problem and Easter tables, see McCluskey (1998, pp. 84-87) and for the Eastern churches also Sanjian (1966) and Mosshammer (2008).

The comet described by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre is not explicitly described as a comet in the text. Rather, it is referred to variously as "the white sign" or "broom". Neuhauser et al (2021:7-8) provided the following for why they viewed as a description of a comet:

2.4. The "white sign" as comet Criteria

In transmitted texts on celestial transients, using a pheno-typical description, it is often uncertain which kind of celestial phenomenon is meant: in our text the phenomenon is not called "comet", and even if it would be called that way, it may still be uncertain whether a comet in today's sense is meant. Five criteria are developed (timing, position/di-rection, colour/form, motion/dynamics, and duration/repetition) for various kinds of celestial phenomena, see, e.g., Neuhauser and Neuhauser (2015a) and D.L. Neuhauser et al. (2018a) for criteria for aurora borealis and D.L. Neuhauser et al. (2018b) for meteor showers (and aurorae).

The "white sign" or "broom" reported in the Chronicle of Zurinin fulfils all five criteria for comets:

Furthermore, our Chronicler connects the sighting of this transient object as negative portent with unfortunate events (e.g. "many schisms"), as was not unusual at this time.

- timing, observed at night-time or twilight: "before early twilight", "fifteen nights", "at evening time", "twenty-five evenings", and stars and planets are mentioned (and shown in the drawing)

- Position of first and/or last sighting: often close to Sun, in or near the ecliptic: "before early twilight, in the north-east" "seen again at evening time, from the north-west", and "in the Zodiac [sign] which is called Aries (emro)"; also tail direction away from the Sun: "[at] its one end/tip, the narrow one, a very bright star (kawkbo) was seen at its head/end/tip. And it was tilting to the north side, but the other wide and very dark one was tilting to the south side"

- colour and form (extension): "white sign", "resembled in its shape a broom", the white broom points to the comet dust tail appearing white due to reflection of sunlight (while the plasma tail would appear bluish and much fainter)

- dynamics, i.e. moving on sky relative to the stars: first "north from these three stars", "it was going bit by bit to the North-East", seen until Pentecost (June 1 morning), then again soon later after conjunction with the Sun, "it was seen again from the north-west", "it was going bit by bit to the south", etc.

- duration: "remained for fifteen nights", "remained for twenty-five evenings", etc.

Neuhauser et al (2021) identified Halley's Comet

(1P/Halley) as a comet described by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre (Chronicle of Zuqnin), Theophanes, Agapius of Menbj,

Nu'aym ibn Ḥammmad, Michael the Syrian, and Chinese, Japanese and Korean sources. They performed astronomical calculations

(least squares fitting of Keplerian orbital solutions) to fit "date corrected" historical reports paying close attention to the

position and locations of celestial objects described in the sky by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre and Chinese sources.

Despite chronological inconsistencies (month and year) among the sources

(possibly due to scribal errors) which they had to "correct", they identified the comet as 1P/Halley and obtained a precise perihelion time (760 May 19.1 ± 1.7) and an inferior conjunction

between the comet and Sun (June 1.8) which is about one day different from a previously

published orbit (760 May 31.9, Yeomans and Kiang, 1981).

Based on their orbital model, philological arguments, and the way the drawing is embedded in the text,

Neuhauser et al (2021:7) suggest that

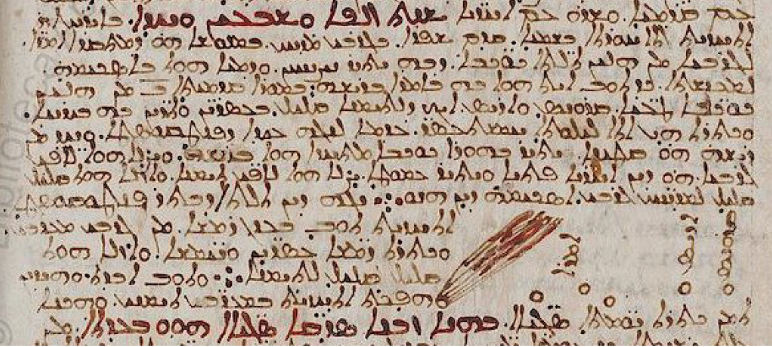

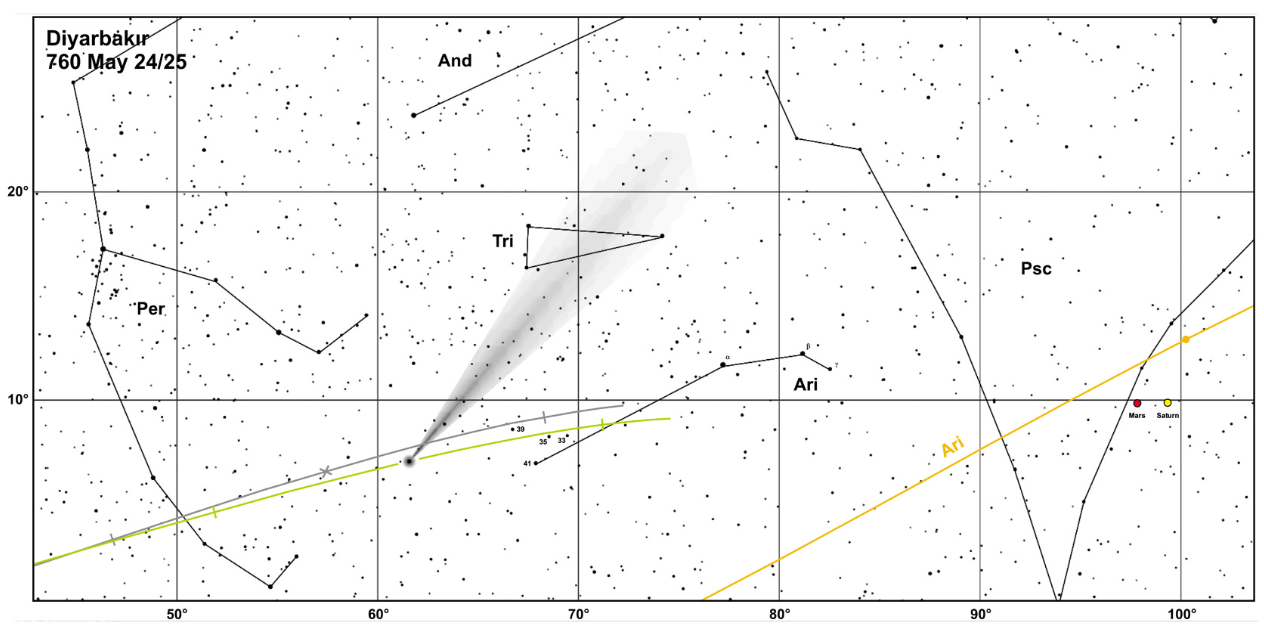

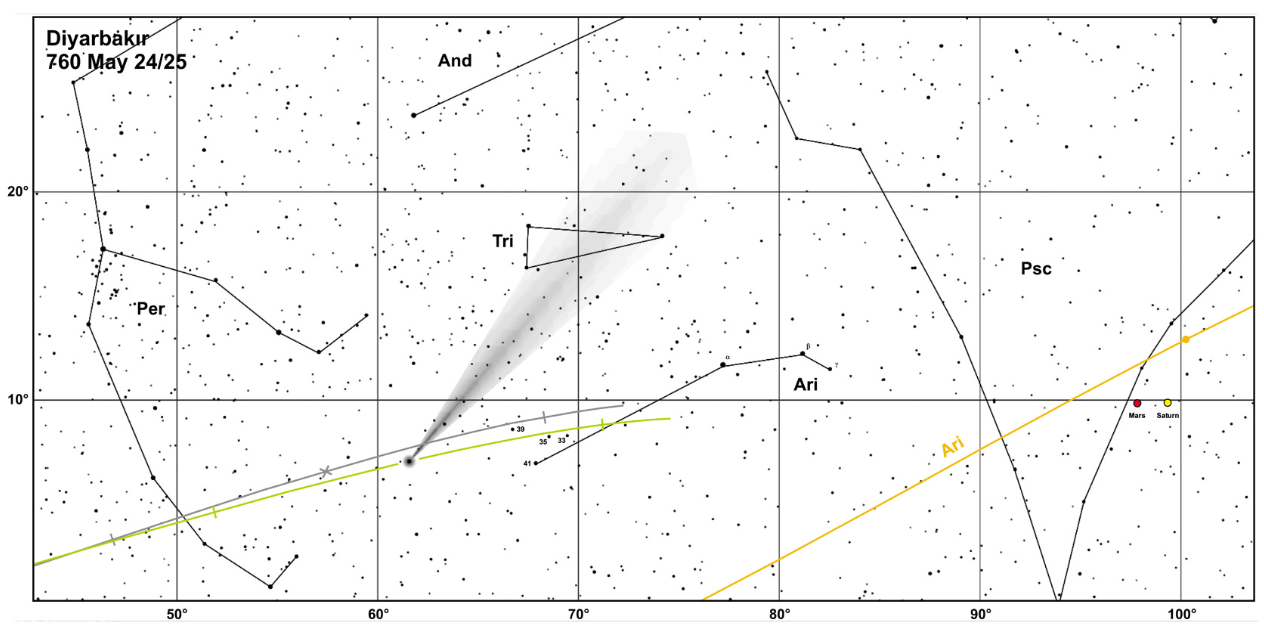

Pseudo-Dionysius drew the comet, 3 stars (Ari aka Aries), and two planets (Mars and Saturn) from an observation made in the early morning (~3 am ?) on 25 May 760 CE.

Their reconstruction of the night sky when and where they suggest the comet was drawn is shown below (Fig. 2) along with a reproduction of the drawing and text by Pseudo-Dionysius

(Fig. 1).

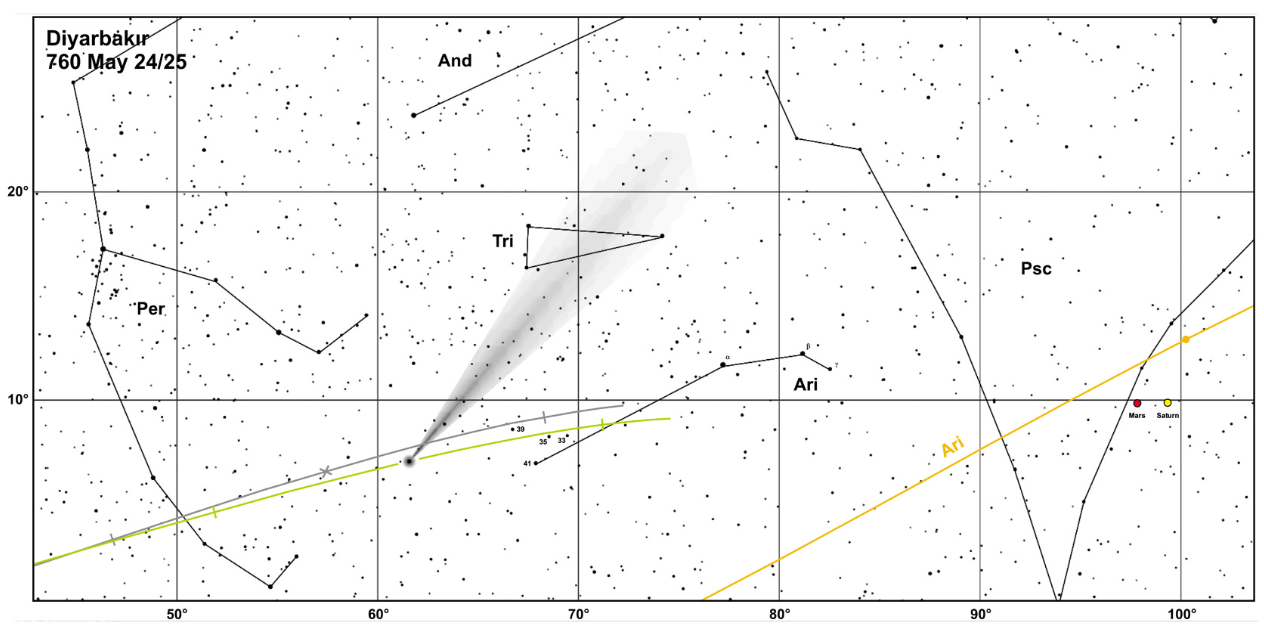

Fig. 2 - A comparison with Fig. 1 shows that the original drawing is for a date around 760 May 25 in the early morning (2:40 h local time, 0 h UT): both Sun (NE) and Moon were under the horizon at that time, 1P/Halley was ~7° above the NE horizon. IAU constellations are indicated in black, the ecliptic in orange with dots at the borders of zodiacal signs. The planets Mars (0.7 mag, red dot) and Saturn (0.5 mag, yellow dot) are still close to each other. The position of the comet is indicated on our own new (green) orbit (and as grey cross on the old orbit, JPL, YK81); both orbits start on May 17. The drawing (Fig. 1) was not used for orbital reconstruction. Here and in all other figures, the comet plasma tail pointing away from the Sun is displayed, while observation and drawing regard the dust tail. This and all other such figures are drawn with Cartes du Ciel (v3.10).

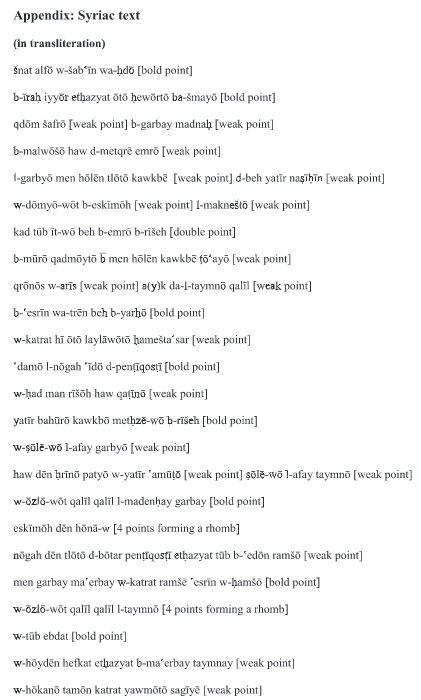

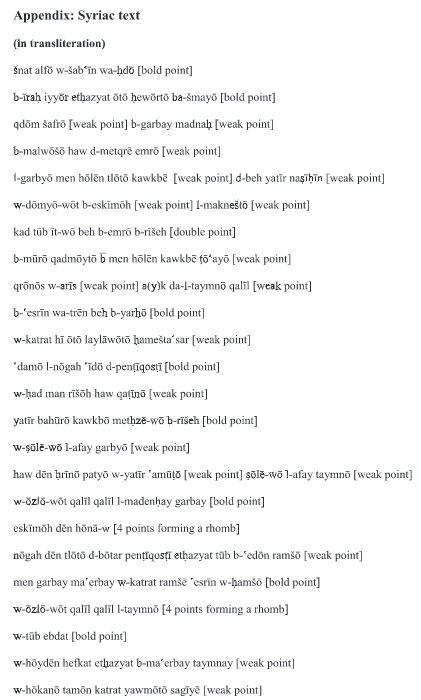

Fig. 1 - Syriac text and drawing: The relevant Syriac text from the Chronicle of Zuqnın (finished AD 775/6) on the comet AD 760 (1P/Halley) – from the middle of the first line shown to the middle of the last line – with a drawing embedded in the text (Vatican Library, Vat. Syr. 162, folio 136v): the comet to the left, the three brightest stars of Aries (α, β, and γ Aries) in the center, and the planets Mars and Saturn as Ares and Kronos to the right, as identified in the Syriac caption. The drawing fits best for around May 25 given the relative position of Ares/Mars east (left) of Kronos/Saturn, both west of Aries. See Fig. 2 for a comparison with a computed position of 1P/Halley for May 25 at 0 h UT.

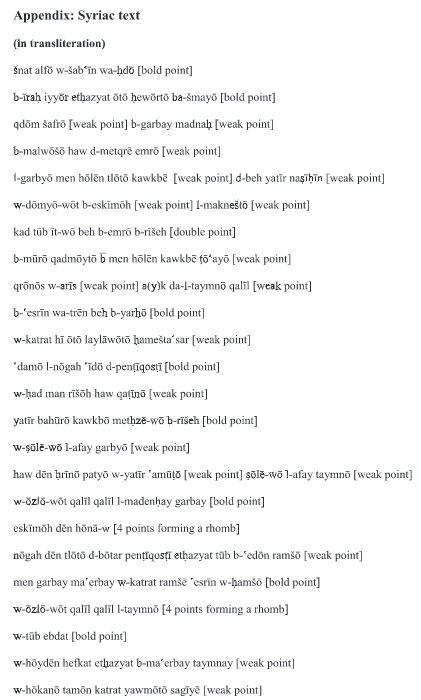

- brackets [] and line breaks are from Neuhauser et al (2021:6).

The year [SE] one thousand seventy one (AD 759/760).

In the month of iyyōr (May)5 a white sign was seen in the sky,

before early twilight (Syriac: šafrō), in the north-east [quarter],

in the Zodiac [sign] which is called Aries (emrō), to the north from these three stars (kawkbē) in it, which are very shining.

And it resembled in its shape a broom, while it was still in the same Aries (emrō) at its edge/end/furthest part (rīšeh)6:

in/at the initial degree (mūrō)7 [of] the second8 [sign] (i.e. Taurus) from these wandering stars (kawkbē), Kronos (Saturn) and Ares (Mars), like somehow a bit to the south, on [day] 22 in the same month.

And the sign itself remained for fifteen nights, until dawn (nōgah)9 of the feast of Pentecost.

And [at] its one end/tip (rīšōh), the narrow one, a very bright star (kawkbō) was seen at its head/end/tip (rīšeh).10 And it was tilting to the north side, but the other wide and very dark one was tilting to the south side,

and it was going bit by bit to the North-East [direction].

Its shape is as follows [now 4 points forming a rhomb meant as pointing to the drawing, which is embedded in the next lines, Fig. 1].

However, at the beginning (nōgah)11 of [the] third [day] after Pentecost, it was seen again at evening time, from the north-west [quarter].

and it remained for twenty-five evenings.

And it was going bit by bit to the south:: [actually 4 points forming a rhomb meant here as a break].

And it again disappeared.

And then it returned [and] was seen in the south-west12 [quarter],

and thus there it remained for many days.Footnotes5 Chabot (1895), Harrak (1999), and Hayakawa et al (2017) read "adar/odor” and gave “March” here (“odor” is the correct West-Syrian transliteration here, while “adar” is East-Syrian); in Syriac, the words for March (odor) and May (iyyor) are written very similar: ‘DR and ‘YR, respectively. We came to the conclusion that iyyor is given here in the MS:

6 The Syriac word rıseh mainly means “its head”, but “its tip, its edge, its end, its furthest part” etc. and such meanings are also attested in dictionaries (e.g. Sokoloff, 2002). See below for a discussion of position 2.

- epigraphically, the Syriac letter /d/ (as in odor) should have a tail, which is not found in the MS

- there is no space between /y/ and the following /r/, the two letters are ligatured, but if it were /d/ (as in odor) there should be a space (as seen in all occurrences of this letter in the month name ‘DR = odor)

- because of a dot underneath the /y/, the letter was thought to be /d/, i.e. reading ‘DR = odor, however, in five occurrences of the month name ‘YR in the MS, four do not have this diacritical dot, one (folio 150v) has it as a thick one, which should be thin – the chronicler was by no means consistent in using diacritics and symbols. Michael the Syrian also gives iyyor as month of the first sighting (Section 4d).

7 The Syriac muro from Greek moira for degree is also attested in Ptolemy’s Almagest for degree.

8 Harrak (1999) gave “in the first degree (of the Zodiacal circle), the second”; Hayakawa et al.: “in the first degree (of the sign), two (degrees)”; see below for a discussion of position 2.

9 Chabot: “la veille”; respectively “eve” in Harrak (1999); the comet was seen in the morning, as mentioned before; for nogah, see footnote 11.

10 An alternative translation could be “and its one end/tip, the narrow one, was very bright; a star was seen at its head/end/tip”, but it does not work because in the MS there is a punctuation between qaṭıno (“narrow”) and yatır bahuro (“very bright”). Hayakawa et al. (2017) brings a punctuation in their transliteration that is in many places inconsistent with the autograph, in particular they overlooked the punctuation by translating “And one end of it was narrow and duskier, one star was seen in its tip”, and they confused the meaning by rendering “duskier” instead of “very bright”: the original word bahuro means “dim” in old Syriac, but later also “bright” after Arabic influence; Chabot (1933) emended bahuro into nohuro, which just means “bright”, but this emendation is not necessary; the first letters (/b/ and /n/) are also quite different in Syriac. The translation by Hayakawa et al. (2017) is not satisfactory: “duskier” would be in contrast to the “star” at this end (comet head), and it would not be in contrast to what is later given as “wide and very dark” (the other end); the drawing also clearly shows a “very bright star”, the comet head; see below for our discussion of the drawing.

11 For the Syriac nogah, instead of “beginning”, Hayakawa et al. (2017) gave “dusk”, which is not attested in Syriac dictionaries; the word nogah does mainly mean “dawn” (see above), but this is not possible here, because the observation was in the “evening time”. Harrak (1999) gave “eve”. Our translation “at the beginning” follows oriental calendars, where the 24 h-day begins with sunset, e. g. nogah d-shapto meaning “Sabbath vespers”, which happen in the evening after sunset. In the report on a bolide in AD 754, the Chronicle of Zuqnın gave the timing as “on Tuesday, when Wednesday was dawning (nogah) ... In the same evening ...”, i.e. it uses nogah here for the beginning of the oriental 24 h-day (D.L. Neuhauser et al., 2018b, event 5, p. 77, Harrak, 1999, p. 196).

12 Lit. west southern

- Part 4

- from Harrak (1999:198)

Left - original drawing of a comet in 760 CE by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre

(Vat.sir.162 137r-136v)

Left - original drawing of a comet in 760 CE by Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre

(Vat.sir.162 137r-136v)Right - redrawn comet by Harrak (1999:198)

On the eve of the third day after Pentecost*, the sign was seen again in the evening in the Northwest, and it remained for twenty five evenings. It moved little by little to the South and then it disappeared. Then it reappeared in the southwest, where it remained in this way for many days.

During this time, many schisms took place in the church because of leadership. The eastern monasteries made John Patriarch, while neither the cities of the Jazira nor all the monasteries approved him. The people of the West and Mosul approved George. Because of this the entire Church became troubled.4

1 A brief mention in Theophanes 431: A.M. 6252 (760-761).

2 Following Ptolemy, the ancients believed that there were seven "wandering stars",

Syriac | | (i.e. planets): The Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars (=Ares),

Jupiter and Saturn (= Kronos), all revolving around the earth.

3 | | : See Manna, Dalil, 54, for its meaning.

4 See above pp. 193ff and 216ff.

- Part 4

- from Harrak (1999:200-201)

- Brackets from JW

The year one thousand and seventy-five [A.G. 1075 = 1 Oct. 763 to 30 Sept. 764 CE]: A severe plague among horses took place in the whole land. ... This disease spread throughout all the nations and kingdoms of the earth, to the point that people were left without horses. The effect of ’the broom’ seen a short while before, was clearly seen in reality, as it swept the world like a broom that cleans the house.

- Part 4

- from Neuhauser et al (2021:Fig. 15)

- Transliteration of the Syriac text on the comet of AD 760 (see also Fig. 1 and Section 2).

[am 6252, AD 759/60]

Constantine, 20th year

Abdelas, 6th year

Paul, 6th year

Constantine, 7th year

... In the same year a very bright comet appeared for ten days in the east and another twenty-one days in the west.b

b Cf. Ps.-Dion. Chron. 63-4, AG 1071.

ANNUS MUNDI 6252 (SEPTEMBER 1, 760— AUGUST 31, 761)

... In the same year a brilliant apparition appeared in the east for ten days, and again in the west for twenty-one.

- brackets [] are from Neuhauser et al (2021:17).

- The same quote (minus the last sentence) appears in Cook (1999:136)

38 This report by Nu'aym ibn Ḥammmad then continues with:

Then we saw a mysterious star with blazing fire the length of two degrees, according to what the eye saw, near Capricorn, orbiting around it like the orbit of a planet during the months of Jumada [July] and [some of the] days of Rajab [Oct] and then it disappeared.This and the following reports definitely do not belong to the comet in AD 760.

(as translated by Cook, 1999 with his additions in brackets, dated by him to AH 145 = AD 762/3)

- brackets [] are from Neuhauser et al (2021:17).

- from Vasilev (1909)

In this same year, a comet [appeared]. It was in Aries, in front of the sun, when the sun was in Taurus. It went on until it came beneath the rays of the sun; then it went behind and remained for forty days.

- from Cook (1999:136)

In this year the star with a tail appeared, and it was in Aries before the sun, and the sun was in Leo. It proceeded until it was under the rays of the sun, then went behind it and stayed 40 days23.Cook (1999:136) notes thatFootnotes(23) I can't find the footnotes in this article.

this observation is probably from Theophilus of Edessa himself.Neuhauser et al (2021:17) wrote the following about the Sun being in Leo:

Note that Cook (1999) incorrectly gave “and the Sun was in Leo”, while the text clearly gives Taurus, see Vassiliev, 1911.

- brackets [] are from Neuhauser et al (2021:19).

40 What is translated as “rod” points to the tail. Chabot translated it as “chevelure”, i.e. “lock of hair” (Chabot, p. 524 n.3). The 16th century Edessan manuscript emended the term sabuqo (“rod”) to sobqo (“emission”), and Chabot interpreted this word as (curled) hair.

In imperial China, court astronomers observed the sky all day and night in order to notice changes2;

owing to this practise — among other transients — comets were recorded in observing logs. While the

original night reports for the 8th century are not extant, later compilations or copies thereof

are available, which are shortened and may suffer from scribal errors. These include: Jiu Tang shu (JTS)

by Liu Xu et al. (945) from AD 945, Tang hui yao (THY) by Wang Pu et al. (961) from AD 961, and Xin Tang shu (XTS)

by Ouyang Xiu et al. (1061) et al. from AD 1061, i.e. the astronomical chapters of the History of the Tang dynasty

(Tang shu), as well as the collection Wenxian tongkao (WHTK) by Ma Duanlin from AD 1317. Extracts for comets were

published by Pingre (1783) in French as well as by Hsi (1957, only for 1P/Halley AD 837),

Ho (1962, see also Hasegawa, 1980 for comments and additions), Kiang (1972), Xu et al. (2000), and Pankenier et al. (2008), all in English.

For general information about astronomy in imperial China, please refer to the detailed monographs by Needham and Wang (1959) and Sun

& Kistemalcer (1997, henceforth SK97), and short summaries also in Kiang (1972), Clark and Stephenson (1977), Stephenson (1994), Xu et al. (2000),

Stephenson and Green (2002), and Pankenier et al. (2008).

Since the Han dynasty (206 BC to AD 220), the sky was structured into about 283 asterisms of various sizes with almost 1500

stars in total (down to 6th mag and a few fainter ones, these are of course incomplete); a Chinese asterism3 can contain one,

few or many stars; the stars of an asterism were combined by lines (skeletons). While this system had a strong continuity

since the Han, some details changed later (not only in Korea and Japan, also in China).

The term zing, often rendered as star(s), can be combined to, e.g. ke zing as guest star(s) or hui zing as broom star(s).

Classical Chinese word morphology does not distinguish between singular and plural.

The names of 28 asterisms are also used for the 28 lunar mansions (LM), which are right ascension ranges from the

determinative (or leading) star of one LM to the next, omitting the south polar region which was not visible

from the Chinese mainland, while the north circumpolar region was of special importance known as the

enclosure (yuan) named Ziwei' or Zigong', see Stephenson (1994), SK97, and Ho (2003, p. 144). For a

list of the 28 LMs and their determinative stars, see, e.g., SK97, Xu et al. (2000), Stephenson and Green (2002),

or Pankenier et al. (2008). Given this equatorial system, hour angles of objects can be given as a certain number

of du (0.9856°) East of the respective determinative star.

There also exist Chinese star charts from the time of the Tang dynasty, namely the Dunhuang maps

(manuscript Stein 3326 dated AD 649-684 by style of characters, mentioning of an astronomer of that

time, style of clothing shown in a figure, and usage of two taboo characters), where more than 1300

stars in 257 asterisms are drawn with skeleton lines, apparently in azimuthal projection (Bonnet-Bidaud et al., 2009).4

Separations on sky including comet tail lengths are given in certain old Chinese linear measures,

which can be converted to angles such as 1 chi being about 1° (Stephenson and Green, 2002; Kiang, 1972 gave 1 chi = 1.50 ± 0.24°),

1 can being 0.1 chi, and 1 zhang =10 chi (see Ho, 1966; Kiang, 1972; Wilkinson, 2000; Stephenson and Green, 2002).

Sometimes, in addition to or instead of a celestial position given as one coordinate, angle, or separation, the compilations

of observing records list the general direction as azimuth, which can be specified in terms of several different compasses;

the precision of the compass used (e.g. 4- or 24-point) then defines the uncertainty or azimuth range of such a position.

The observing dates are specified by name of the emperor, year with a multi-year reign period, lunar month, and then usually the day count

in a 60-day-cycle (ganzhi) - a continuous counting was achieved prior to the advent of the imperial period in 221 BC; sometimes, instead

of or in addition to the day count (1-60), the age of the Moon is given; the luni-solar calendar had 12 lunar months starting on

the second new-moon after winter solstice (i.e. in January or February), plus seven intercalary months in 19 years

(called just "x-th intercalary month" located after the "x-th" month), like the Meton cycle; these rules were in use since a calendar reform during the Han.

The normal Chinese 24 h-day ran from midnight to midnight, but in astronomical records, for observations after midnight,

the former date is given (some late sources may have modified the date to the new civil date). The night was separated

into five watches of equal lengths per night, which changed during the year.

2 Such observations were performed, because it was thought that they identify dangerous political trajectories

(astrology, but also weather rules etc., e.g. from the Han dynasty: "320 stars can be named. There are in all 2500 ...

All have their influence on fate", Needham and Wang, 1959, p. 265), or can indicate misgovernment ("any anomalous happenings in nature ...

were construed as signs of warnings by heaven toward the misbehaviour or misgovernment of the ruler of man", also from the Han,

Wang Yiichuan, 1949, Bielenstein, 1984). The dramatic appearance of comet Halley in 12 BC, for example, was interpreted by

both Gu Yong and Liu Xiang as a sign that the Western Han dynasty was in danger of collapse; the two writers each identified

different court factions as responsible for the peril the dynasty faced, and both held that if the right actions were

undertaken the sign would vanish and the dynasty would likely survive; neither writer saw the future as fixed or

determined, though both associated it with an elevated likelihood of disastrous political events (Chapman, 2015).

3 Groups of stars (xing cang) were given certain names, which do not normally reflect their appearance on sky, even

if connected with skeleton lines; this is similar for Babylonian, Western, and Chinese constellations. To discriminate

from Western constellations, Chinese star groups are often called asterism. However, this term derives from the

Greek asterismos as was used by Ptolemy in his Almagest for what we now call constellations

(now defined as fields on sky by IAU mostly based on Ptolemy's Almagest).

Xing qun is the modern Chinese term for constellation; literally, it means group of stars.

4 Stars and asterisms on the 13 charts are drawn only in a crude way with rough positions and several mistakes,

e.g. the asterism name Lou in Aries is missing (but the three stars apparently are drawn), the colour-convention

for stars is not followed strictly (Chinese charts show the stars and asterisms from three Han dynasty schools

in different colour: red for those from Shi Shen, black from Gan De, and white/yellow from Wu Xian),

twice the Chinese characters for "right" zuo and "left" you, which are very similar, are mixed up,

the asterism Sangong near the pole is shown twice (Bonnet-Bidaud et al., 2009). Given that the maps are

drawn on expensive pure mulberry fibres (3940 mm by 244 mm scroll), this atlas may be a copy produced

by a wealthy but not well-talented student of Li Chunfeng, one of the main astronomers of the 7th century,

who is mentioned in the accompanying text and could have done the (now lost) original map based on

observations and/or the astronomical chapters of the Jin shu, which he had written.

We present here our own new, technical, very literal translations, which aim to preserve the detail and word order of the original Chinese, but have been slightly smoothed to present correct English sentences (see appendix for the Chinese texts); significant variants in Ho (1962, no. 273 and 274), Xu et al. (2000), and Pankenier et al. (2008) are mentioned in footnotes. First, we translate the oldest text from JTS (36.1324, and much shorter in 10.258), counted as object no. 273 in Ho (1962), with some Chinese terms, explanations, and significant variants from THY (43.767) and XTS (32.838, unless otherwise specified) in round brackets, our additions in square brackets (e.g. the day/night number in the 60-day-cycle), starting with the night 760 May 16/17, line breaks by us:

Tang Emperor Suzong (literal: Tang[‘s] Solem Ancestor) Qia- nyuan [reign-period]20 3[rd] year, 4[th] month, dingsi (54) night (THY gives the lunar date: “27[th] day”, XTS omitted “night”), 5[th] watch (“5[th] watch” omitted in THY and XTS),We will discuss this transmission in detail below to obtain dated positions.

[a] broom (hui) [star] (XTS: “ hui xing” for “broom star”) emerged (THY: “seen at (yu)”, XTS: “there was ... at (yu)”) east (dong) direction, colour being white, length (JTS 10.258 adds: about) 4 chi (THY and XTS have color and length after the next phrase),

it was located/situated in (zai) Lou, [in] Wei21 for-a-while/space (jian),

it rapidly moved toward east (dong) north (bei) corner (THY omitted “corner”; XTS has instead: “east direction rapidly moved”),

passing through Mao, Bi, Zui (XTS: “Zuixi”), Shen,22 Jing (XTS: “Dongjing”), Gui (XTS: “Yugui”), Liu23 [and] Xuanyuan (THY added “xiu” for “lodge”24),

reaching Taiwei Youzhifa25 7 cun position (THY: “reaching Taiwei west (xi), Youzhifa west (xi) 7 chi”; XTS omitted “Taiwei” and has only “reaching Youzhifa west (xi)”),

In all more than 50 days, only then (fang) [it] disappeared (THY very similar; XTS has “in all more than 50 days, [it was] not seen”)” (continued below).

Next, we present additional relevant texts, not given in Xu et al. (2000) and Pankenier et al. (2008). Ho (1962) cited under his no. 274 a record from JTS 36.1324 (Ho: CTS 36/8a), and gives two more texts, HTS 32/6b (=XTS 32.838) and, almost identical, WHTK 286/23a (286/ 29b-30a in the Siku quanshu huiyao edition). Here our own new literal translation of the JTS text (with variants from XTS and also from THY 43.767), which follows immediately after the previous comet report:

Intercalary 4[th] (XTS omitted “4[th]”) month, xinyou (58=May 20 with night 20/21), new-moon (THY: “ Shangyuan reign-period, [initial] year, intercalary 4[th] month, 21[st] day” (=June 9)), [an] ominous star (yao xing) seen at (yu) south (nan) (THY: “west (xi)”; XTS: “there was [a] broom star (hui xing) at (yu) west (xi)”) direction, length several zhang.After reporting the disappearance of the comet, "Only [when] reaching 5[th] month ...", XTS (32.838) adds:

This time, since [the] beginning [of the] 4[th] month, heavy fog [and] heavy rain, reaching [the] end [of the] 4[th] intercalary month (i.e. the last 10 days), only then (fang) [it, i.e. bad weather] stopped (instead of this whole sentence, THY and XTS have “Reaching 5[th] month, [ominous star] disappeared”, XTS adds: “Only [when] reaching ...”).

This month, rebel bandit Shi Siming again captured [the] Eastern Capital (i.e. Luoyang). Grain prices leapt [up] in expense, dou (i.e. about 6 liters of rice) reaching eight hundred wen. People ate each- other [and] corpses covered [the] ground.

Lou corresponds to [the pre-imperial state of] Lu, Wei [and] Mao [and] Bi correspond to Zhao, Zuixi [and] Shen correspond to Tang, Dongjing [and] Yugui correspond to [the] capital city (jingshi) (meaning probably the historical capital of the Zhou dynasty) allotment, [as for] Liu, its half corresponds to [the] Zhou allotment. As-for-cases-in-which (zhe) two brooms seen in-succession, amassing disaster. Moreover, Lou, Wei space (firm) [corresponds to] Tiancang (`Celestial Granary').The whole last paragraph is an astro-omenological interpretation of the comet report. In Chinese astro-omenology, Wei (LM 17) governs granaries and warehouses, as found in the Jin shu ( , p. 100, 2003, p. 147) — and indeed, the term Tiancang means `Celestial Granary/ ies'. There is also an asterism Tiancang, which is however located mostly in LM Kid and only partly in LM Lou; there are further asterisms meaning `Celestial Granaries' in LMs Lou and Wei, e.g. Tianjun (SK97), written Ticatqurt in Pankenier et al. (2008). (Lou governs cattle rearing and animal sacrifices, see Ho, 1966, p. 100.)

In the past, it was considered that there were two comets in spring AD 760, e.g. Yeomans et al. (1986). All sources for Ho no. 274 give "several zhang" as length, so that one could consider that they mean the same object: the "ominous star" (yao xing) in the west in THY (June 9 evening) would fit with the comet path given in the previous text; the object(s) in JTS, XTS, and WHTK for May 20/21 (morning) in the south or west are not consistent with the path of comet no. 273, which was then still in the NE. If the previously cited JTS text refers to the same object, a date correction would be needed — it should be June 9 (as in THY) instead of May 20. One explanation could be: May 20 corresponds to the 58th day, xin-you in the 60-day-cycle, while June 9 is the 18th, xin-si, so that only the 2nd part would have been mistaken in JTS, XTS, and WHTK by a copying scribe (you for si); THY conserves the correct date as date in the lunar calendar (day 21 = June 9), converted from the 60-day-cycle as found in its source. Note that the two dates (May 20 and June 9) pertain to the same Chinese lunar month (4th intercalary month), just the day within the month is different. More reasonably, since "new moon", i.e. the first day of the lunar month, is given in JTS and XTS in addition to xin-you (58), which is correct for May 20, a confusion between date and event might be just due to a false concatenation in the compilation process; furthermore, it is plausible that the second comet report, preserved correctly in the THY text, originates from another source and observing site, where, e.g., weather conditions did not allow a detection earlier than June 9.

To sum up, among the three texts for Ho object no. 274, the THY transmission appears to be the least corrupt: sighting on June 9 (JTS and XTS: May 20/21), THY has west direction (XTS also west, but JTS has south). That the information in THY is most reliable here, relies on the assumption that the "two" objects Ho no. 273 and 274 are one and the same comet; this is supported by the fact that the duration in the first comet report (about 50 days after May 17/18) corresponds well with the disappearance in THY and XTS ("Reaching 5[th] month, [it] dis¬appeared"). This assumption is also supported by the following astro-omenological interpretation in XTS 32.838: "As-for-cases-in-which (zhe) two brooms seen in-succession, amassing disaster". In the translation "two separate broom stars appearing simultaneously" ( phenson and Yau, 1985), the word "separate" is added (but not given in the Chinese text); the sense of the adverb in Classical Chinese (reng) suggests repetition with close or immediate proximity in time ("appear one after the other" or "in quick succession" or "repeatedly").26 That it is only one comet is justified by further independent reports, where the conjunction with the Sun is explicitly reported, e.g. the Chronicle of Zugnin (see above) and several further East Mediterranean and West Asian reports (Section 4).

There is one more extant source, XTS 6.162-3, but the variant transmission gives only very short information:

4[th] month ... dingsi (54), there was [a] broom star, emerged at (yu) Lou, Wei, Jiwei (56), Lai Zhen (died ca. AD 763) became Sharman Eastern Circuit's Military Commissioner charged to overcome [the rebellion of] Zhang Weijin. Intercalary month (4[th] omitted) xinyou (58), there was [a] broom star, emerged at (yu) west (xi) direction.... Jimao (16), [there was a] large amnesty, change [of] reign-period [title], grant [of] civil [and] military office [and] rank.... This month [was a] large famine. Zhang Weijin surrendered.This late source shows how compilers work: XTS 6.162-3 concatenated input from XTS 32.838, a source which is already shortened — as one consequence, the comet's position at the beginning is a bit corrupt. This source, which belongs to the "Basic Annals" (Benji) section of the history (a general chronicle of events during the reign of each emperor), rather than the technical treatise, is only interested in the first appearance of the comet (first sightings at the very beginning and after conjunction with the Sun) - the main point is the connection to historical events on Earth.

The year 760 fell midway through the An Lushan rebellion (AD 755-763). The early years of the rebellion had witnessed the abdication of an emperor who had reigned for more than forty years, the fall and subsequent recapture of the main capital at Chang'an, and casualties reportedly numbering in the millions. In both JTS and XTS 6.162-3, close chronological proximity associates the comet's appearance with politics, the rebellion and the famine that accompanied it; XTS 32.838 reflects these in an astro-omenological interpretation.

As quoted above, JTS reports the weather: "This time, since [the] beginning [of the] 4[th] month (new-moon on Apr 19/20), heavy fog [and] heavy rain, reaching [the] end [of the] 4[th] intercalary month (i. e. the last 10 days, new-moon on June 17/18), only then [it, i.e. bad weather] stopped." Monsoon typically arrives in May and may well end in June. In addition to shortenings and omissions in the compilation process, problems with weather and the rebellion may also have influenced the observations and the data record (and might be partially responsible for the famine). Still, since the beginning of the Tang dynasty (AD 618), there are no better transmitted records for any comet before AD 760 (see Pankenier et al., 2008 for the texts).

The Korean "Chronicle of the Three Kingdoms" (Samguk sagi) briefly reported a " hui comet" sometime during the lunar month 761 May 9 to June 7 (Ho, 1962, no. 275); this work, compiled AD 1142-1145 (Schultz, 2004), is often off by a few years — probably, our comet is meant. The Kingdom of Silla is traditionally dated 58 BC to AD 935. However, the Silla dynasty, which united the whole of peninsula, ran from AD 668 to 935.

From the Chinese observations also all five comet criteria mentioned above (Section 2) are fulfilled. A "broom colour being white" also points to a comet with dust tail.

20 Xu et al. (2000) added here “i.e. 1st year of the Shangyuan reign period” –

in fact the Shangyuan reign period started only at the beginning of the 4th

intercalary month, after the Qianyuan reign period had ended with the 4th

month.

21 Lou (“Hillok” or “Lasso”) and Wei (“Belly” or “Stomach”, see SK97 and Ho,

1966) could be the asterisms of that name (both in “our” Aries, i.e. the

constellation as defined by the International Astronomical Union) or the lunar

mansions (right ascension ranges) named after these asterisms (LM 16 and LM

17, respectively) starting in the west with the determinative star β Ari for Lou

and with 41 Ari for Wei. See below for position C1.

22 Xu et al. (2000) give “Can” here, which is a more common pronunciation of

the Chinese character; however, in this context, the correct pronunciation is

“Shen”, LM 21 and an asterism in Orion.

23 This list could point to either asterisms or LMs: Mao (“Mane”, LM 18), Bi

(“Hunting net”, LM 19), Zui or Zuixi (“Beak”, LM 20), Shen (“Triaster” or

“Hunter”, LM 21), Jing or Dongjing (“Eastern Well”, LM 22), Gui or Yugui

(“Spectral Carriage”, LM 23), and Liu (“Willow”, LM 24); translations of asterisms here are the Han time interpretation, some have changed later (SK97).

24 Xuanyuan (“Yellow Emperor”) is usually only an asterism, which does not

have the additional function as LM asterism; given that it seems to be listed here

as xiu, it may have some ‘lodge’-like function; Xuanyuan is meant as skeleton of

17 stars in Leo and Lynx starting with α Leo close to the ecliptic.

25 Taiwei (“Great Tenuity Enclosure” or “Supreme Subtlety Palace” or “Privy

Council”) is one of three asterisms, which are so-called “enclosures” (yuan) with

two “walls” each, Taiwei being a large area with 10 stars in Virgo and eastern

parts of Leo (12 stars in Tianguan shu, but then only 10 in the official Shi Shi,

SK97); the determinative star of Taiwei is Youzhifa (β Vir) at the southern end of

Taiwei’s western wall (SK97).

26 Stephenson and Yau (1985) and Yeomans et al. (1986) thought that,

in addition to the comet seen since AD 760 May 16/17, there would have

been another comet seen in the south or west since May 20/21.

- from Neuhauser et al (2021:Fig. 16)

- The Chinese texts from JTS, THY, and XTS on the comet of AD 760 (see Section 3).

| Date | Reference | Corrections | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| May 760 CE | Pseudo-Dionysius of Tell-Mahre - The year one thousand and seventy-one: In the month of Adar (March), a shining sign was seen in the sky before dawn on the northeast side which is called Ram in the Zodiac, to the north of the three most shining stars. Its shape resembled a broom. |

month of Adar changed to Iyyar |

|

| 1 Sept. 759 to 31 Aug.760 CE | Theophanes - A.M. 6252 ... In the same year a very bright comet appeared for ten days in the east and another twenty-one days in the west |

none |

Chronological Discussion from Neuhauser et al (2021:17)

A duration of 10 days in the east (before conjunction with the Sun) and 21 days in the west (after conjunction) is slightly shorter but consistent with the reports from Zuqnın (and China) for the comet of AD 760. Theophanes’ chronology is sometimes uncertain by 1–2 yr (Mango and Scott, 1997) – here one year, since the Byzantine year runs from 760 Sep 1 to 761 Aug 311. Footnotes

1 JW: This assumes that Theophanes started his year on Sept. 1 instead of 25 March. According to Grumel (1934:398-402), A.M.a 6252 falls within Synchronism MB when the year starts on 1 Sept. |

| 22 April - 21 May 760 CE | Nu'aym ibn Ḥammmad - We saw the comet rising in Muḥarram in the year [Anno Hijra, AH 145 = AD 762/3] with the dawn from the east, and we would see it during the dawn for the rest of Muḥarram; then it disappeared. |

A.H. 145 corrected to A.H. 143 - see Chronological Discussion. |

Chronological Discussion from Neuhauser et al (2021:17) and Cook (1999:136)

Given other dating errors in this quite apocalyptic Hadith collection, it may be dated to AH 143, i.e. AD 760/1 (Cook, 1999). With new-moon on 760 Apr 20 and May 19, the month of Muḥarram would run from AD 760 about Apr 21 to May 20 (±1 or 2 days depending on the first detection of the crescent moon), but the comet of AD 760 did not disappear at around May 20. However, the source used by Nu'aym ibn Ḥammad could have given the date on a western calendar system, e.g. as May, which would have been converted loosely to Muḥarram, probably based on a Christian source using e.g. the West Syrian Seleucid calendar as, e.g., the Chronicle of Zuqnın. A scribal error is then required only for the year number (AH) “145”, which should be 143. Then, the text would be fully consistent with the Chronicle of Zuqnın: seen first since some time in the month of May of AD 760 in the morning dawn (“with the dawn”, Zuqnn: “safro”) in the east and also like that for the rest of that month “during the dawn” (Zuqnın: “nogah”) – instead of “rest of Muḥarram”, we should read “rest of iyyor/May”; the Chronicle of Zuqn ̄ın reported the last visibility before conjunction with the Sun for the early morning of the night May 31/June 1 (“Pentecost”). Then, according to Nu'aym the comet was seen after conjunction “after the sunset in the twilight between the north and the west for two month or three”, i.e. again similar as in Zuqnın (for 25 evenings in the NW and later again for “many days”), after conjunction the comet was definitely seen in two different months (June and July). When Nu'aym ibn Ḥammad mentioned a reappearance “two or three years” later, he could either mean some other comet or transient object, or he could have interpreted the text in the Chronicle of Zuqnın, which is found in the report for SE 1075 (AD 763/4), which is, however, again about the comet of AD 760: “The effect of ’the broom’ seen a short while before, was clearly seen in reality, as it swept the world like a broom that cleans the house” (Harrak, 1999), see Section 2.1 for full citation (given that the Chronicle of Zuqnın does not mentioned any other comet or celestial sign in between the comet report in AD 760 and this short statement later, it is likely that the latter short note points to the comet of AD 760). Therefore, given all the similarities (except the offset by 2 years), it is likely that the (direct or indirect) source used by Nu'aym ibn Ḥammad is the Chronicle of Zuqnın – this would be the first hint that our chronicle was active before been buried in a Sinai monastery in the 9th century. It is very likely because of the tradition in Theophanes that there was a mistake made in the date here (since there are a great many errors in this edition of the apocalyptic text), and that the real date is 143/760.22 According to the Chinese records of this appearance it began on 16 May (corresponding to 24 Muharram of that year) and lasted into July. This would be consistent with our tradition, which continues to detail several other comets. Footnotes

(22) I can't find the footnotes in this article. |

| 760 CE | Agapius of Menbij - In this year [AD 760] the star with a tail appeared, and it was in Aries before the Sun, and the Sun was in Taurus. It proceeded until it was under the rays of the Sun, then went behind it and stayed 40 days |

none |

Chronological Discussion from Neuhauser et al (2021:17)

Cook remarks: “This observation is probably from Theophilus of Edessa himself”. (Note that Cook (1999) incorrectly gave “and the Sun was in Leo”, while the text clearly gives Taurus, see Vassiliev, 1911.) |

| May 755 CE - May 765 CE | Michael the Syrian - And in this year in the month of iyyor (May), a comet star [kawkbo qumiṭus – the latter obviously from the Greek kometes] was seen before the Sun in Lamb (Aries), when the Sun was in Taurus. |

“and in this year” equated to A.G. 1066-1076 - see Chronological discussion. |

Chronological Discussion from Neuhauser et al (2021:19)

The expression “and in this year” refers to SE 1076 (AD 764/5), if related to the preceding account which deals with an earthquake in Khorasan. However, chapter 25 of Michael the Syrian, in which the comet report appears, covers the period from SE 1066 to 1076 – this cast doubt about the expression “and in this year”. When Michael the Syrian quotes large texts, he names his sources, but when he gathers information to include in a Chapter, he picks and copies, but not necessarily in chronological order. |

| Description | Image | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Comet in Chronicle of Zuqnin |

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Syriac text and drawing: The relevant Syriac text from the Chronicle of Zuqnın (finished AD 775/6) on the comet AD 760 (1P/Halley) – from the middle of the first line shown to the middle of the last line – with a drawing embedded in the text (Vatican Library, Vat. Syr. 162, folio 136v): the comet to the left, the three brightest stars of Aries (α, β, and γ Aries) in the center, and the planets Mars and Saturn as Ares and Kronos to the right, as identified in the Syriac caption. The drawing fits best for around May 25 given the relative position of Ares/Mars east (left) of Kronos/Saturn, both west of Aries. See Fig. 2 for a comparison with a computed position of 1P/Halley for May 25 at 0 h UT. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 1 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Sky around 760 May 25 in the early morning |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2A comparison with Fig. 1 shows that the original drawing is for a date around 760 May 25 in the early morning (2:40 h local time, 0 h UT): both Sun (NE) and Moon were under the horizon at that time, 1P/Halley was ~7° above the NE horizon. IAU constellations are indicated in black, the ecliptic in orange with dots at the borders of zodiacal signs. The planets Mars (0.7 mag, red dot) and Saturn (0.5 mag, yellow dot) are still close to each other. The position of the comet is indicated on our own new (green) orbit (and as grey cross on the old orbit, JPL, YK81); both orbits start on May 17. The drawing (Fig. 1) was not used for orbital reconstruction. Here and in all other figures, the comet plasma tail pointing away from the Sun is displayed, while observation and drawing regard the dust tail. This and all other such figures are drawn with Cartes du Ciel (v3.10). Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 2 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Horizon plot for Amida for 760 May 18 at 2:40 h local time |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Horizon plot for Amida for 760 May 18 at 2:40 h local time: The Chronicle of Zuqnın reported a white sign ... in ... Aries, to the north from these three stars in it, which are very shining ... before early twilight, the first dated position in Section 2 (Z1), to the north of α, β, γ Ari on the horizontal system. The comet with tail directed away from the Sun (in the NE below horizon) is indicated for May 18 at 0 h UT on the new (green) orbit (as grey cross on the old orbit). The expected positions on May 20.0 and 26.0 (UT) are indicated with green (and grey) tick marks. Our positional error box is shown in red, the relevant stars in Aries as red dots with their names, Mars as labelled red dot, Saturn yellow, and the ecliptic in orange. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 3 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Horizon plot for Amida for 760 May 22 at 2:40 h local time |

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Horizon plot for Amida for 760 May 22 at 2:40 h local time: The Chronicle of Zuqnın reported the comet to be in/at the initial degree of [the] second [sign] (i.e. Taurus) ... still in the same Aries at its edge/end/furthest part, the second dated position in Section 2 (Z2). This record constraints the comet position to be close to 30° ecliptic longitude (Taurus 0°) ± some uncertainty, estimated to be ±1.5° (from some other observations of the same author, see Section 2) – indicated here by orange dashed lines with ecliptic longitude λ given (ecliptic in orange). The comet was at this longitude range and also still in Aries (at its end); the end of Aries was built by 33, 35, 39, and 41 Ari, indicated as red error box, while the head of Aries and its surrounding is made up by α, β, and γ Ari. The comet is indicated for May 22.0 (UT) on the new (green) orbit (grey cross on the old orbit). The expected positions on May 20.0 and 29.0 (UT) are indicated with green (and grey) tick marks. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 4 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Horizon plot for Amida for 760 June 1 at 2:40 h local time |

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Horizon plot for Amida for 760 June 1 at 2:40 h local time: The Chronicle of Zuqnın reported that the comet was going bit by bit to the North-East direction until dawn of Pentecost in the night May 31 to June 1, the third dated position in Section 2 (Z3), the red error box. The NE direction is taken to be azimuth 45 ± 22.5°. The comet is indicated with tail directed away from the Sun for June 1 at 0 h UT on the new (green) orbit (as grey cross on the old orbit slightly below the horizon). On our new orbital solution, the comet was in conjunction with the Sun on June 1.8 (UT) with minimal elongation being 19.1° (according to the standard JPL orbit, it was on May 31.9 with 18.5° minimum elongation); the last observation before comet-sun-conjunction as reported in the Chronicle of Zuqnın for early morning of June 1 is consistent only with our new orbit regarding this inferior conjunction. The expected positions on May 30.0 and 31.0 (UT) are indicated with green (and grey) tick marks. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 5 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Horizon plot for Amida for 760 June 3 at 20:30 h local time |

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Horizon plot for Amida for 760 June 3 at 20:30 h local time: The Chronicle of Zuqnın reported that the comet was seen from the north-west [quarter] at the beginning of [the] third [day] after Pentecost ... at evening time (Z4 and Z5, Section 2), the red error box. The comet is indicated with tail directed away from the Sun on the new orbit (cross on the old orbit). Along our best fitting orbit of 1P/Halley the closest encounter of the comet with the Earth occurred on 760 June 3.6 (UT) with 0.37 au (according to the JPL standard orbit, closest approach was on June 2.7 with 0.41 au). The expected positions on June 2.74 and 4.74 (UT) are indicated with green (and grey) tick marks. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 6 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Horizon plot for Chang’an (now Xi’an, China), the Tang capital, for the night 760 May 16/17 at 4 h local time |

Horizon plot for Chang’an (now Xi’an, China), theTang capital, for the night 760 May 16/17 at 4 h local time: The waning crescent moon is seen in Aries. The Chinese reported a broom [star] emerged east direction ... it was located in Lou, the first dated position in Section 3 (C1). Lou is here Lunar Mansion 16 (LM 16), the right ascension range from β Ari to 35 Ari (Wei is LM 17). The given East direction can be considered as azimuth 90 ± 45∘, so that the given right ascension range (LM 16) is constrained in the NE by azimuth 45°, but in the SE by the local horizon. The positional error box is indicated by blue lines. The star α, β, and γ Ari and 35, 39, and 41 Ari, which make up the asterisms Lou and Wei, respectively, are indicated as blue dots, but the asterisms are not meant here. Our new and the previous (JPL/YK81) orbits are shown as green and grey lines, respectively, from May 16/17 midnight onward to the east. We draw a comet with plasma tail directed away from the Sun (in the NE below horizon) for its position on May 16.86 (UT) on the new (green) orbit – and for the same date as cross on the old (grey) orbit. In order to illustrate the motion of the comet along both paths the expected positions on May 20.0 and 30.0 (UT) are indicated with green and grey tick marks, respectively; the ecliptic in orange. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 7 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Equatorial plot showing the whole comet path for the AD 760 perihelion |

This equatorial plot shows the whole comet path for the AD 760 perihelion (north up, east left): borders of the Chinese lunar mansions (right ascension ranges) are indicated as dotted lines (numbers on top) always going through their determinative star. The Chinese asterisms Lou, Wei, Xuanyuan, and Taiwei east and west (with Youzhifa in Taiwei west) are shown as blue skeletons. The ecliptic is shown as orange line with dots every 30° to indicate the borders of zodiacal signs. The planets Mars and Saturn are shown in close conjunction for May 22 at 0 h UT, the waning crescent moon for May 16.86 (UT). The positions derived here for the comet (Table 1) are shown as coloured boxes. Our new orbit is shown in green, the previous (YK81/JPL) orbit in grey, both from May 17 at 0 h UT (in Aries, right) until July 15 at 0 h UT (in Virgo, left), comet positions are shown as comet symbols on our new orbit on the dates of observation, and as crosses on the old orbit; the software Cartes du Ciel v3.10 shows the plasma tail directed away from the Sun. We can see that on June 9.58 (UT), the comet is indeed in Xuanyuan. Tick marks are shown on the new orbit on June 14.0, 19.0, 24.0, 29.0, and July 10.0 (UT) showing that the comet slowed down and got too faint (Section 5). Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 8 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

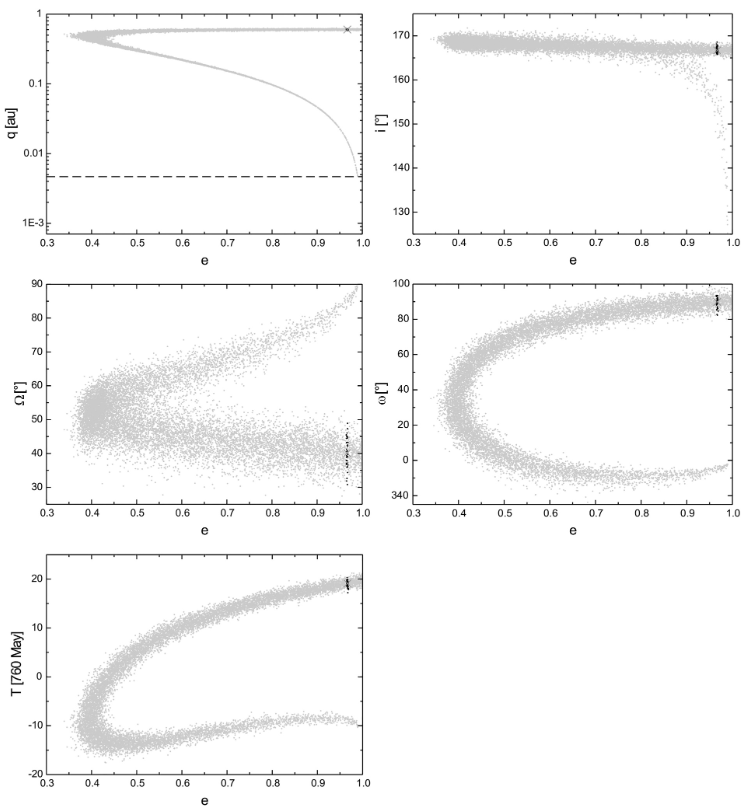

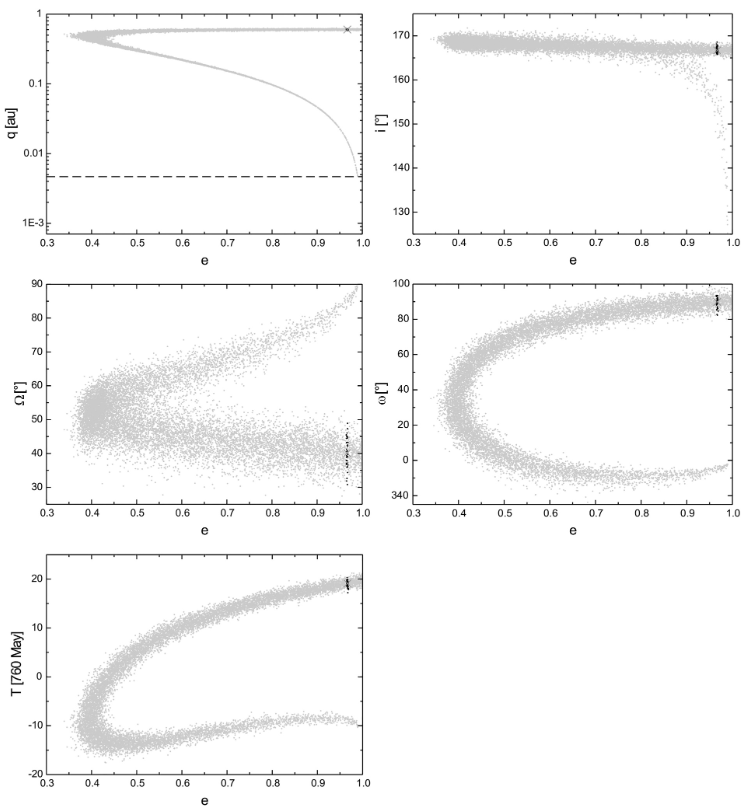

| Keplerian elements for non-periodic solutions |

Fig. 9

Fig. 9Keplerian elements for non-periodic solutions (eccentricity e=1): They can be compared to (and are fully consistent with) the parameter ranges for periodic solutions with semi-major axes 17–19 au (Table 2, Fig. 13) shown as grey data points with error bars in the upper parts of the graphs. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 9 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Results from fitting the orbit |

Fig. 10

Fig. 10Results from fitting the orbit: Correlations between the Keplerian elements, shown as light grey points, of all closed solutions found: perihelion distance q, inclination i, longitude of ascending node Ω, argument of perihelion ω, and perihelion time T (from top left to bottom). In the upper left, for q, we indicate the solar radius as dashed line. Since most solutions for perihelion distance q and inclination i cluster within small ranges, we can use these two to identify the comet of AD 760, see next two figures. Having identified the comet as 1P/Halley (Fig. 12), we constrain the solution to those with semi-major axes from 17 to 19 au as 1P/Halley – these are shown here as dark points, and the best fit among them as cross. For eccentricity e = 1, one can see the parameter range for non-periodic solutions. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 10 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Results from fitting the orbit |

Fig. 11

Fig. 11The cumulative distribution functions for q (left) and i (right panel) (all solutions as in the previous figure): The highest slopes (i.e. the peaks in the probability density distribution) are indicated by vertical dashed lines and are located at q ~ 0.60 au and i ~ 168° (i.e. retrograde). We use these values for identifying the comet (Fig. 12). Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 11 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Perihelion distance q versus inclination i. |

Perihelion distance q versus inclination i. the comet of AD 760 (as constrained to q ~ 0.6 au and i ~ 168°, Fig. 11, as diamond in the upper part) is compared to other presently known comets with values in the range of i = 155 - 180° and q = 0.56 - 0.64 au: C/1855 Ll (Donati) has a very uncertain period of about 252 yr, it was observed only for 14 days, C/1963 Al (Ikeya) has a well-known orbit, but was not visible in AD 760; the three other comets shown as circles in the lower center are unperiodic. For C/1992 J2 (Bradfield) and C/1896 Cl (Perrin-Lamp) there is no evidence that they have periods less than many thousands of years, the case is similar for C/2002 T7 (eccentricity e = 1.00048565(39), JPL 144, i.e. non-periodic). There are no comets with i = 170 - 180° in the plotted range for q. For comet 1P/Halley, we show the data pair for its perihelion in AD 1986 (plus sign) and all pairs from the orbital solutions in Yeomans and Kiang (1981) connected by a line (their data for perihelion AD 760 as plus), obtained from the JPL small-body database, precessed to 2000.0; the orbital elements from telescopic observations scatter more than those from extrapolation to pre-telescopic time. In the upper part, we show q and i of the best fitting solution for 17-19 au semi-major axes for the comet of AD 760: they are best consistent with comet 1P/Halley (YK81 did not specify error bars). Therefore, the identification of the comet in AD 760 as comet 1P/Halley is justified - for the first time for this perihelion only from historical data. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 12 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Probability distribution of the Keplerian elements |

Fig. 13

Fig. 13Probability distribution of the Keplerian elements as found in the semi-major axes range of 17–19 au. Small grey squares with error bar indicate the best fitting solution (Table 2). The distributions of the elements correspond well with the elements of the best fitting solution – within their uncertainties. Neuhauser et al (2021) |

Fig. 13 - Neuhauser et al (2021) |

| Apparent brightness evolution for a usual comet |

Fig. 14