Khirbet Iskander

Khirbet Iskander

Khirbet IskanderClick on image to explore in Google Earth

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Khirbet Iskander | Arabic | خربة اسكندر |

- from ChatGPT‑4o, 29 June 2025

- Sources: Penn Museum Expedition (1986) , ACOR–CAORC (2017) , ADAJ 2018 Season Report

Traditionally, EB IV has been seen as a period of urban collapse following the abandonment of EB III walled cities. However, excavations at Khirbet Iskander since 1981 (led by Suzanne Richard) have revealed a fortified and complex community that persisted through this transitional era. The site features thick perimeter walls (~2.5 m), a monumental gateway, corner towers, broadroom houses, and specialized storage areas.

Public buildings—including cultic bench-lined rooms and installations with large storage jars, bins, and hearths—suggest a level of social organization not typically associated with EB IV. These findings challenge the collapse narrative and demonstrate adaptation and resilience in the face of regional instability.

Later reoccupation of the site was minimal, and the absence of significant post-EB IV disturbance has left these early strata remarkably intact. Khirbet Iskander thus offers a unique window into settlement continuity, architectural development, and social complexity in a period often labeled a "Dark Age."

- from ChatGPT‑4o, 29 June 2025

- Sources: ACOR–CAORC (2017) , Penn Museum Expedition (1986) , ADAJ 2018 Season Report

Key excavation seasons include:

- 1981–1984: Initial surveys and test trenches confirmed the significance of the site during EB IV ( Richard 1982).

- 1987: Further reports confirmed architectural complexity and stratigraphic integrity of EB IV remains.

- 1994–2004: Major excavation seasons (1994, 1997, 2000, 2004) exposed a fortified settlement plan, the Area C gateway, residential buildings, and cemeteries.

- 2007–2016: Continued work expanded understanding of public architecture and environmental context; this phase included the final publication of Area C.

- 2013 and 2016: Later campaigns focused on new excavation areas, radiocarbon chronology, and preparation for final synthesis and publication.

These excavations demonstrated that Khirbet Iskander was not a transient encampment, but a fortified settlement preserving urban traditions well into EB IV. This has prompted a reevaluation of societal organization and resilience in the southern Levant during the third millennium BCE.

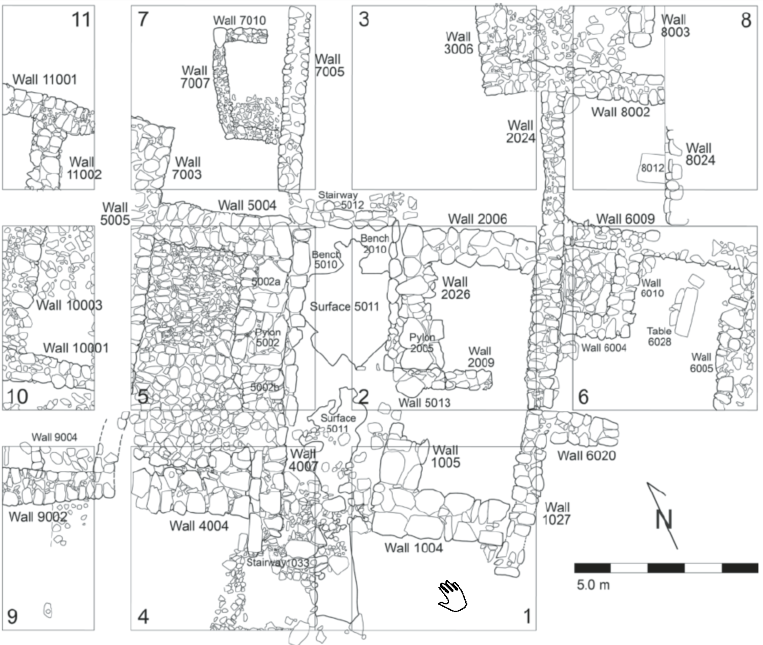

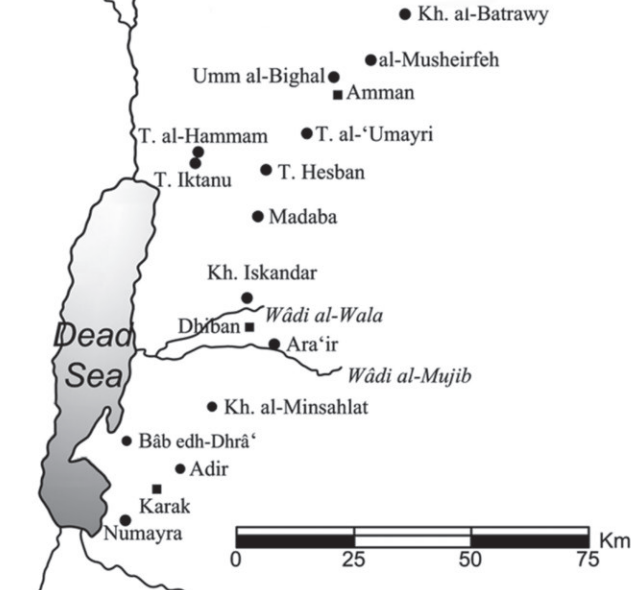

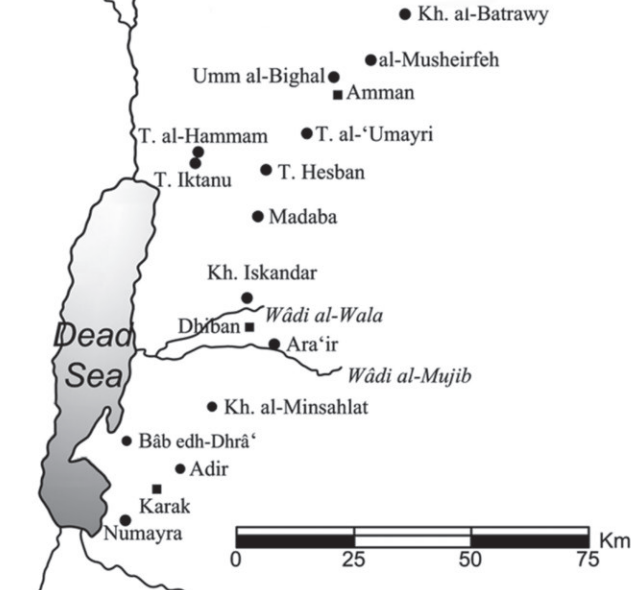

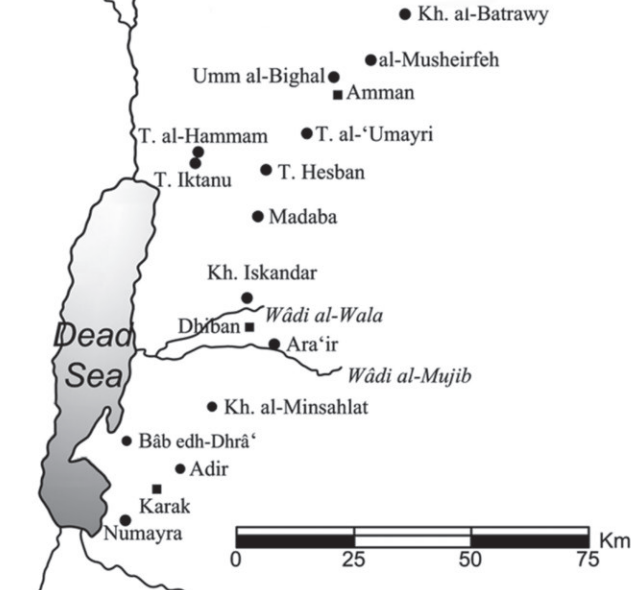

- Fig. 1 Location Map

from Richard et al. (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map showing the location of Khirbat Iskandar

Richard et al. (2018)

- Fig. 1 Location Map

from Richard et al. (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map showing the location of Khirbat Iskandar

Richard et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2 Contour map of

the mound showing the three excavated areas, A, B, and C from Richard and Boraas (1998)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Contour map of the mound showing the three excavated areas, A, B, and C

Richard and Boraas (1998) - Fig. 2 Excavation Areas

from Richard et al. (2018)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan showing excavation areas at Khirbat Iskandar

Richard et al. (2018)

- Fig. 2 Contour map of

the mound showing the three excavated areas, A, B, and C from Richard and Boraas (1998)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Contour map of the mound showing the three excavated areas, A, B, and C

Richard and Boraas (1998) - Fig. 2 Excavation Areas

from Richard et al. (2018)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Plan showing excavation areas at Khirbat Iskandar

Richard et al. (2018)

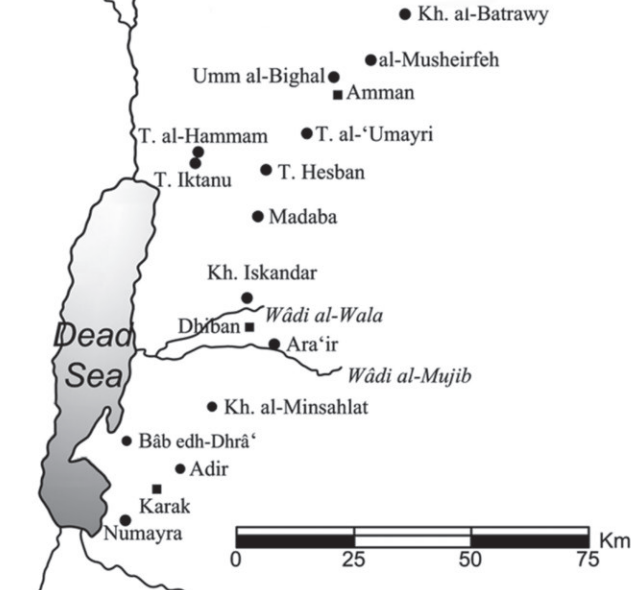

- Fig. 3 Plan of Area C from from Richard et al. (2020)

- Fig. 3 Plan of Area C from from Richard et al. (2020)

- Fig. 5 Wall Collapse

from from Richard et al. (2020)

- Square C06 photo by JW

- Fig. 5 Wall Collapse

from from Richard et al. (2020)

- Square C06 photo by JW

- from ChatGPT‑4o, 29 June 2025

- sources: Richard et al. (2018), Richard et al. (2020)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 3B | EB IV | c. 2500–2300 BCE | Later architectural reuse and additions including W.8002A and curved bench/wall structures; overlaid earlier Phase 3A features. Confirms internal remodeling and construction within gateway room. [2020: Fig. 5] |

| Phase 3A | EB IV | c. 2500–2300 BCE | Main gateway architecture including paved rooms, plaster floors, and pillar bases (e.g., 8064); features included doorway/thresholds indicating formal construction. [2020: Fig. 6] |

| Phase 2 | EB IV | c. 2500–2300 BCE | Outdoor and indoor surfaces west of W.6039 and W.6049; included well-sealed plaster surfaces laid against major wall lines and built over earlier fill layers of mudbrick and concrete-like material. [2018: p. 599] |

| Phase 1 | EB III–IV Transition | c. 2600–2500 BCE | Early domestic construction (e.g., W.6034); pebble and flint surfaces; pottery shows transitional EB III/IV forms. Built atop destruction debris from EB III. [2018: p. 599; 2020: Fig. 7] |

| EB III Destruction | EB III | c. 2700–2600 BCE | Collapsed mudbrick and ash layers beneath Phase 1 surfaces, interpreted as widespread EB III destruction layer. No explicit mention of earthquake cause, but stratigraphic evidence for violent termination. [2018: p. 600; 2020: p. 607] |

- from Richard and Boraas (1998)

- Generated by Chap GPT and suspect

| Phase | Description | Key Features | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | Earliest EB IV occupation |

|

Represents the transition from EB III to EB IV, indicating continuity in settlement patterns. |

| B | Middle EB IV occupation |

|

Indicates a period of established domestic life with significant architectural and societal development. |

| A | Late EB IV occupation |

|

Suggests a shift towards more complex urban features and possible external threats. |

Stratigraphy of Khirbet Iskander

| Stratigraphic Phase | Approx. Period | Description | Area(s) | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase A | Late EB IV (ca. 2200–2000 BCE) |

Rebuilding of Area C gateway and adjacent fortifications. Settlement reorganization following destruction at end of Phase B. Fewer domestic structures; more emphasis on public architecture. |

Area C, Area B | Long (2010); Richard et al. (2018) |

| Phase B | Middle EB IV (ca. 2300–2200 BCE) |

Dense domestic occupation with broadroom houses, work spaces, and public complex (possible cultic structure). Evidence of destruction and burning at end of phase. Highest occupational density of EB IV. |

Area B | Richard et al. (2013); Richard et al. (2018) |

| Phase C | Early EB IV (ca. 2400–2300 BCE) |

Initial EB IV occupation following EB III continuity. Reuse of EB III walls with new construction over earlier foundations. Beginning of architectural shift to smaller-scale units. |

Area B, Area C | Long (2010); Richard et al. (2013) |

| EB III Levels | ca. 2700–2500 BCE |

Massive stone architecture including fortification walls. Later reused or modified in EB IV. Pottery and carbon data show prolonged occupation. |

Area C, Area D | Richard (2016); Cordova & Long (2010) |

| Pre-Urban (Sub-EBA) | Pre-2700 BCE |

Sparse evidence for earlier ephemeral activity. Lithic scatter and possible seasonal encampment traces. |

General surface finds | Richard et al. (2010) |

Cordova, C. E. & Long, J. C., Jr. (2010) Khirbat Iskandar and Its Modern and Ancient Environment

In Richard et al. (Eds.), *Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar*, Vol. 1, pp. 21–36. Boston: ASOR.

Long, Jesse C. Jr. (2010) The Stratigraphy of Area C

In Richard et al. (Eds.), *Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar*, Vol. 1, pp. 37–68. ASOR Archaeological Reports 14.

Richard, Suzanne et al. (2013) Three Seasons of Excavations at Khirbat Iskandar, 2007, 2010, 2013

ADAJ, v. 57, pp. 447–461.

Richard, Suzanne (2016) Recent Excavations at Khirbat Iskandar, Jordan: The EB III/IV Fortifications

In O. Kaelin & H.-P. Mathys (Eds.), *Proceedings of the 9th ICAANE*, Vol. III, pp. 585–597. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

As mentioned above, although the work in Area C had been completed, the architecture restored, and the final report published (Richard et al. 2010), the decision was made to reinvestigate the critical EB IV phasing uncovered in this area: the latest Phase 3a-b gateway, the Phase 2, and the Phase 1 domestic levels.

We focused on Squares C06/C08 at the eastern perimeter of the gateway, where features, objects, and considerable debitage suggested a lithic workshop through several phases (Fig. 3, and Long 2010: Figs. 3.11, 3.26). Importantly, excavation had revealed remains of an earlier (Phase 1) settlement on the eastern side of the gateway, which appeared to yield transitional EB III/IV pottery (Long 2010: Figs. 3.1–2; Richard 2010: Fig. 4.5).

The restoration of Square C06 (Long and Libby 1999) was intended to illustrate the superimposition of three EB IV phases. Thus, the northern half preserved the Phase 3 structures, the southern half the remnant of a Phase 2 wall (6039) sandwiched between the later Phase 3 Wall 6005 and the preceding remains of a Phase 1 (6034) domestic structure (Long 2010: Figs. 3.19–20). The goal was to excavate soil layers west of these walls to obtain larger samples of pottery from more exposure of associated surfaces. Specifically, we endeavored to excavate the northern half of the square to the Phase 1 surface visible in the southern half.

Removing the Phase 3 table and benches (which will be returned in the future to their previous restored state), the team excavated the underlying surface, which may actually have been a restored surface, to reveal more of the Phase 2 wall. The rest of the season devoted itself to tracing more of the Phase 2 and Phase 1 surfaces and associated walls in Square C06 (Fig. 4). Excavation confirmed that a plaster surface sealed against the Phase 2 wall (6039), and that it overlay an apparent makeup layer of concrete-like and mud-brick material (6046). The latter covered a plastered interior surface made up of pebbles and flint inclusions (6045) that sealed against Phase 1 W. 6034. The latter was new information about the construction history of Phase 1 W.6034 emerging from a foundation trench (filled with reddish mudbrick material), which showed that Surface 6045 was laid subsequently to the wall’s construction.

Importantly, excavation in Square C06 revealed there was a layer of mudbrick and ash lying beneath the Phase 1 surface, primarily collapse material in the south, whereas in the north there was some alignment of mud bricks. It is almost certain now that this pre-Phase 1 layer witnesses the destruction of the EB III settlement encountered everywhere in Area B below EB IV remains. Moreover, excavation revealed that the Phase 2 surface west of Wall 6039 was an outdoor surface (see below).

Square C08 had previously been excavated with the dimensions of 5.0 × 2.5 m. Significant remains from three EB IV phases convinced us to return to expand the square to 5.0 × 5.0 m, thus aligning it with Square C06, and to revisit the exposed but undated walls discovered in the short 2007 excavation in the area. As published in Vol. 2 (Long 2010: Fig. 3.26), Square C08 comprised two major structural features: a (Phase 3) paved room with a doorway at the north, and a southern area with a central massive stone base jutting out of the east balk. Excavation to expose the presumed northern extension of the Phases 1–2 architecture encountered in Square C06 had been attempted in 2007. Unfortunately, at the end of the season, the exposed wall lines (mentioned above) which emerged in the constricted area remained unexcavated and undated (see Long 2010: Fig. 3.25).

In 2016, confirmation of the previously hypothesized 3B phase in C08 (Long 2010: Fig. 3.28) came to light in the excavation of the eastern half of the square. An addition to east–west W. 8002 (8002A) had been constructed in Phase 3B, as seen in the difference between W. 8002 (1.25 m in height) and W. 8002A (0.60 m in height), as well as in the continuation of the structure’s interior plaster surface, discovered to overlie a Phase 3A pillar base (8064). These two elements affirmed the existence of a Phase 3B room (Fig. 5). Interestingly, though, the wall line (W. 8024) previously apparent in the balk (Long 2010: Fig. 3.53) took an unexpected configuration; a partial wall with collapse at the south.

As Fig. 5 illustrates, there was an unusual curved wall/bench built against the southern and eastern faces of walls 8002A and 8051 respectively in the southern half of the square in Phase 3B. This structure connected with eastern boundary W. 8047; at the west, however, it ended short of W. 6009 to the south. Surface 8053 sealed against the four walls of this Phase 3B room: 8051, 8002A, 6009, and 8047.

In the earlier Phase 3A plan of the area, excavation confirmed the massive square stone base 8012 was correctly dated to this phase. Excavation revealed the base to be associated with a type of cobbled pavement/platform (8055), or row of pillar bases (including pillar base 8064 discovered at the north end). This new feature ran under and thus antedated the Phase 3B room just described (Fig. 6). The Phase 3A plan showed that the room included a doorway/threshold at the southeast juncture of eastern boundary W. 8047 with east–west W. 6009.

The complete Phase 3A architectural plan thus shows that the rooms in C08 and C06 were of similar dimensions, and that stone base 8064, located in the middle of the room, was, in fact, a pillar base, rather than a work platform; an option which had been considered previously.

Since the goal was to expose more complete architectural units of the earlier phases, the Phase 3B bench-like structure, as well as the newly recovered Phase 3A pavement, were removed once fully documented. Continuing excavation revealed the expected northern extent of the C06 Phase 2, W. 6049. It is now clear that this is the western wall of a structure, as it corners with W. 8066 (Fig. 7). The excavation of a foundation trench along the northern side of W. 6009 revealed that a Phase 2 surface of the building covered a leveling of mudbrick materials, below which a Phase 1 pebble and flint exterior surface (8071) came to light, the same stratigraphy of which was discovered in Square C06.

Below the Phase 1 surface, mudbrick and ash materials appeared, undoubtedly the top of the EB III destruction layer discovered throughout Area B below EB IV levels. Regrettably, due to the short season, the intended investigation of the EB III phase and the several undated walls which had been uncovered in 2007 could not take place. Although in the past it was suggested that EB III structures were reused in Phase 1, we were not able to confirm this hypothesis this year, or determine whether there was a hiatus or not in this area between the end of EB III and the beginning of EB IV.

At the northwest corner in Area B, there are 25 5 x 5m squares, where two major EB IV phases (A–B) and multiple EB III phases (C–D–E) have come to light. Phase A at the top was a well-built and well-preserved extensive neighborhood village settlement (Richard and Long 2005: Fig. 5), while the earlier Phase B settlement was quite different, providing an intriguing accumulation of data reflecting unusual complexity for the period, including a public complex with storeroom and ritual activity areas (Richard 1990). The latter settlement was built into and atop the destruction layer of the EB III (Phase C1) settlement, with reuse and rebuilding of earlier walls evidenced, including the fortifications (Richard 2016). The Phase C1 settlement included what appeared to be a public building, or at least a central room for storage, auxiliary workrooms, and a large courtyard (Richard et al. 2013: Fig. 11), built within the fortifications.

An earlier Phase C2 settlement (the construction phase of the outer (later) fortifications) had been exposed only in limited areas. A Phase D level was mostly known from the inner (earlier) mudbrick/stone fortification. As for the western trace wall, it had been assumed that the “rubble” perimeter wall (B05A002), which abutted the northwest tower, was the only candidate for a western trace wall, although questions about this wall and its unusual construction abounded. In 2013, the discovery of a major EB III fortification (W. 4A006) just west of the “rubble” wall confirmed that the latter wall had been constructed subsequent to W. 4A006 (see below and Richard et al. 2013; Richard 2016: Fig. 3). Likewise in 2013, a small probe area in the western half of Square B01 provided new information about the depth of EB III occupation on the site, information we aimed to explore further in 2016 (see below). With this general background on earlier work in Area B, we turn to the 2016 excavation season.

The discussion will begin with Square B01. The eastern half of the square had been left at the C1 settlement level (below the destruction layer), while to the west the C2 settlement was represented by a lower surface associated with several hearths. The 2013 season had uncovered (below the Phase C2 hearth level/surface) the remains of a 1.0m high stone structure running under the Phase C tower platform (Richard et al. 2013). On the interior of the structure, excavation revealed a series of surfaces and mudbrick debris layers, the upper surfaces of which appeared to connect with Phase D surfaces to the west, while the lower surfaces and the founding level of the wall were at a great depth, making it difficult to associate with other architecture or phases thus far exposed. We very tentatively termed the lower surfaces and construction phase of the wall Phase E. The pottery appeared to be diagnostic for early EB III. With these discoveries in mind, we decided in 2016 to investigate this enigmatic building further, by excavating in the eastern half of Square B01 (a Phase C1 wall was a natural boundary for the work). As we shall see, the nature of the discoveries here were such that it was not possible to trace the building.

Lying below the Phase C1 surface in the east, a layer of mudbrick debris and ash was encountered, within which excavation revealed an unusual mudbrick horseshoe-shaped tabun/bin (B01136) (Fig. 8). There was an extensive firepit, and much ash and mudbrick debris. Cook pot fragments were found inside the feature. The tabun/bin had been constructed on a plaster surface and contiguous to a wall (B01139), which emerged beneath and on a different alignment from overriding Phase C1 wall B01072. Found lying on the surface between the mudbrick feature and the wall were two very large perforated weights (Fig. 9). These new discoveries from this season have considerably clarified the Phase C2 settlement in this area. It is now clear that the lower level of mudbrick, ash, and burning encountered previously related to activity areas, not to an earlier destruction. The tabun/bin, in combination with multiple hearths discovered to the west, suggests there was a significant work area in this vicinity, differing considerably from the later Phase C1 remains above, which we termed a central room, probably for storage. Clearly, more work is needed to comprehend the plan of the Phase C2 settlement, but it is possible that the area so far excavated functioned as a kitchen, although the hearths might indicate other activities/industries, perhaps the firing of pottery.

The 2016 season was extremely important for the new information uncovered about the architectural plan and the EB IV phasing/ceramics in Area C. We will, in the future, return to investigate the important EB III/IV transition and earlier EB III levels.

In Area B, the excavations in Square B01 provided us, finally, with information about the Phase C2 settlement, about which little was known beyond the fact that it was the construction phase of the outer fortifications. The significant, newly revealed work activity area is of great interest, along with the clarification of the earlier mudbrick/ ashy materials just below the Phase C1 settlement.

Although there are still questions about the fortifications vis-à-vis the EB III-IV occupational remains, we believe that we have a good grasp of the construction history of the fortification system at the site, and hope to find even more definitive evidence in future.

- Generated by Chap GPT and may be suspect

- Burn layers with widespread ash and charcoal deposits.

- Collapsed architecture and fragmented domestic installations.

- Abandoned storage vessels, some broken, suggesting sudden departure.

- Disrupted stratigraphy indicating a catastrophic event.

| Effect | Location | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Square C06 and "in the north"

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Contour map of the mound showing the three excavated areas, A, B, and C Richard and Boraas (1998)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Plan showing excavation areas at Khirbat Iskandar Richard et al. (2018) |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Square C06 and "in the north"

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Contour map of the mound showing the three excavated areas, A, B, and C Richard and Boraas (1998)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Plan showing excavation areas at Khirbat Iskandar Richard et al. (2018) |

|

|

Cordova, C. E. (2007) Millennial Landscape Change in Jordan: Geoarchaeology and Cultural Ecology

Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Cordova, C. E., & Long, J. C., Jr. (2010) Khirbat Iskandar and its Modern and Ancient Environment

In S. Richard et al. (Eds.), Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar, Vol. 1, pp. 21–36. Boston: ASOR Archaeological Reports 14.

D’Andrea, M. (2013) Of Pots and Weapons: Constructing the Identities During the Late 3rd Millennium BC in the Southern Levant

In L. Bombardieri et al. (Eds.), Identity and Connectivity, BAR-IS 2581[I], pp. 137–146. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Gophna, R. (1992) The Intermediate Bronze Age

In A. Ben-Tor (Ed.), The Archaeology of Ancient Israel, pp. 126–158. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Long, J. C., Jr. & Libby, B. (1999) Khirbet Iskander

In V. Egan & P. M. Bikai (Eds.), “Archaeology in Jordan, 1998 Season”, AJA, 103(3), pp. 498–499.

Mazar, A. (2006) Tel Beit Shean and the Fate of Mounds in the Intermediate Bronze Age

In S. Gitin et al. (Eds.), Confronting the Past, pp. 105–118. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Prag, K. (2014) The Southern Levant during the Intermediate Bronze Age

In M. L. Steiner & A. E. Killebrew (Eds.), The Archaeology of the Levant, pp. 388–400. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Regev, J., de Miroschedji, P., Greenberg, R., Braun, E., Greenhut, Z., & Boaretto, E. (2012) Chronology of the Early Bronze Age in the Southern Levant

Radiocarbon, 54(3–4), pp. 525–566.

Richard, S. (1982) Report on the 1981 Season of Survey and Soundings at Khirbet Iskander

ADAJ, v. 26, pp. 289–299.

Richard, S. (1990) The 1987 Expedition to Khirbet Iskander and Its Vicinity: Fourth Preliminary Report

BASOR Supplement 26, pp. 33–58.

Richard, S. & Long, J. C., Jr. (1995) Archaeological Expedition to Khirbet Iskander, 1994

ADAJ, v. 39, pp. 81–92.

Richard, S. and Boraas, R. (1998) The Early Bronze IV Fortified Site of Khirbet Iskander, Jordan: Third Preliminary Report (1984 Season)

, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. Supplementary Studies, No.

25, Preliminary Reports of ASOR-Sponsored Excavations 1982-85 (1988), pp. 107-130

Richard, S. & Long, J. C., Jr. (2005) Three Seasons of Excavations at Khirbat Iskandar, 1997, 2000, 2004

ADAJ, v. 49, pp. 261–275.

Richard, S. (2010) The Area C Early Bronze IV Ceramic Assemblage

In S. Richard et al. (Eds.), Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar, Vol. 1, pp. 21–35. Boston: ASOR Archaeological Reports 14.

Richard, S., Long, J. C., Jr., Wulff-Krabbenhöft, R., & Ellis, S. (2013) Three Seasons of Excavations at Khirbat Iskandar, 2007, 2010, 2013

ADAJ, v. 57, pp. 447–461.

Richard, S. (2016) Recent Excavations at Khirbat Iskandar, Jordan: The EB III/IV Fortifications

In O. Kaelin & H.-P. Mathys (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th ICAANE, Vol. III, pp. 585–597. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Richard, Suzanne; Long, Jesse C. Jr.; D’Andrea, Marta; Wulff-Krabbenhöft, Rikke (2018)

Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar and Its Environs: The 2016 Season Annual of the

Department of Antiquities of Jordan, v. 59, pp. 597–606.

Richard, Suzanne; Long, Jesse C. Jr.; D’Andrea, Marta (2020)

Expedition To Khirbat Iskandar And Its Environs: The 2019 Season Annual of the

Department of Antiquities of Jordan, v. 61.

Richard, S., Long, J. C., Jr., Holdorf, P. S., & Peterman, G. (Eds.) (2010)

Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar and Its Environs

Vol. 1: Final Report on the Early Bronze IV Area C “Gateway” and Cemeteries. Boston: ASOR Archaeological Reports 14.

S. Richard et al. (Eds.), Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar, Vol. 1, pp. 37–68. Boston: ASOR Archaeological Reports 14.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master kmz file | various |