Khirbet el-Qom

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Khirbet el-Qom | Arabic | خربة الكوم |

| Sapir | Hebrew | |

| Makkedah | Hebrew |

- from Chat GPT 5.2, 18 December 2025

- sources: Wikipedia – Khirbet el-Qom

The site is best known for its Iron Age bench tombs and associated inscriptions dating to the late eighth century BCE. One tomb contained an inscription invoking Yahweh, accompanied by a protective hand symbol, which has been widely discussed in studies of Judahite religion and epigraphy. Together with material from sites such as Kuntillet ʿAjrud, the Khirbet el-Qom inscriptions are central to scholarly debates concerning religious practice and belief in Iron Age Judah.

Later phases of activity include substantial evidence from the Persian and Hellenistic periods, notably more than a thousand Aramaic ostraca reflecting administrative and daily life, as well as indications of continued cultic activity. Roman-period burial caves with Hebrew inscriptions demonstrate the long-term significance of the site within the regional settlement and funerary landscape.

W. G. Dever, HUCA 40–41 (1969–1970),

139–204

D. Barag, IEJ 20 (1970),

216–218

J. S. Holladay, ibid.

K.

Jaros, Biblische Notizen 19 (1982),

31–42

Lettre d’Information

Archéologique Orientale 6 (1983),

55–71

RB 78 (1971), 593–595

L. T.

Geraty, BASOR 220 (1975), 55–61

id., AUSS 5–6 (1978), 191–193

A.

F. Rainey, BASOR 251 (1983), 1–22

S. Schroer, Ugarit-Forschungen 15

(1983), 190–199

Z. Zevit (1981),

137–140

id., The Word of God Shall

Go Forth (D. N. Freedman Festschrift),

ASOR Special Volume Series, BASOR

255 (1984), 39–47

A. Catastini,

Henoch 6 (1984), 129–138

J. M.

Hadley, VT 37 (1987), 50–62

G.

Garbini, Annali, Istituto Universitario

Orientale di Napoli 38 (1978),

191–193

A. Lemaire, RB 84 (1977),

595–608

id., Maarav 2 (1982),

159–162

id., BAR 10/6 (1984),

42–51

id., VT 38 (1988), 220–230

A. Skaist, IEJ 28 (1978), 106–108

G. Barkay, ibid., 209–217

J. Naveh,

BASOR 235 (1979), 27–30

P. A.

Dorsey, TA 7 (1980), 185–193

S.

Mittmann, ZDPV 97 (1981), 139–152

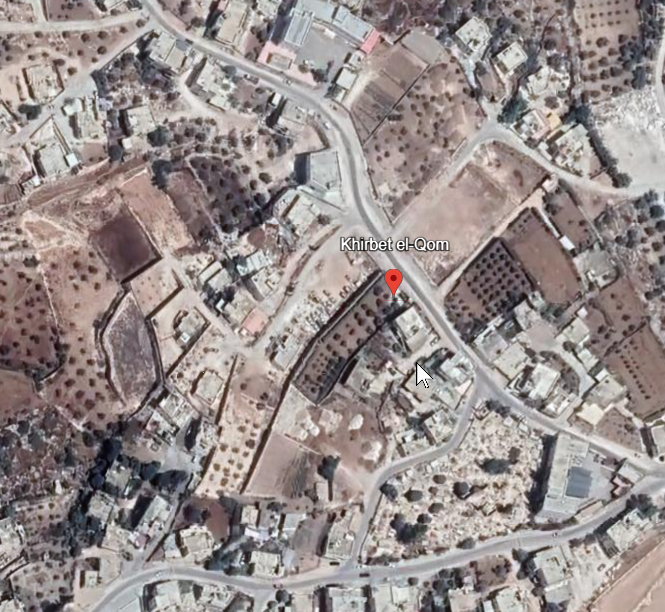

Khirbet el-Qom (map reference 1465.1045) is located 20 km (12 mi.) west of Hebron, at the juncture of the Shephelah and the foothills of the central ridge, at the inner reaches of Nahal Lachish. It had been identified with the Saphir of Micah 1:11 by F. M. Abel, on the basis of the Arabic name of the subsidiary wadi nearby, Wadi es-Saffar. More recently, however, D. A. Dorsey has proposed that Khirbet el-Qom is the Makkedah of Joshua 10 and Eusebius’ Onomasticon—that is, the inner fortress of the Lachish “trough.” In that case it would belong, according to A. F. Rainey, to the third district of the Judean Shephelah, as reflected in Joshua 15. This seems a more plausible identification in the light of Judean toponymy.

Khirbet el-Qom was placed on the modern archaeological map in 1967, when the Archaeological Survey of Israel, under M. Kochavi and others, made a quick reconnaissance. Also in the fall of 1967, W. G. Dever surveyed the site in the course of a brief salvage project, noting remnants of an offset-inset cyclopean city wall and quantities of tenth- to seventh-century BCE sherds, including a royal lmlk jar handle stamped with the word ziph. The salvage campaign also produced several eighth- to seventh-century BCE Judean bench tombs, several inscribed pottery vessels (a decanter reading “Yahmol” and a bowl reading “El”), and a group of inscribed shekel weights.

One of the bench tombs (tomb 1) was elaborately laid out and well cut, with three chambers off of a central arcosolium, each of which had three benches with recessed head and foot niches. An inscription (no. 2) over the entrance to the central chamber may be read: “Belonging to ʿUzza, son of Nethanyahu” (or “ʿOphah, daughter of Nethanyahu”). To the left was a three-line inscription (no. 1) that read: “Belonging to ʿOphai, son of Nethanyahu; this (is) his tomb-chamber (qeder).” The name ʿOphai, “swarthy one” (?), occurs in Jeremiah 40:8; and ʿUzza is attested, for instance, in 2 Samuel 6:6–8 and 2 Chronicles 6:14. Another bench tomb, of the “butterfly” type, had a four-line inscription (no. 3) on one of the central pillars that was badly defaced. It read in part:

“Uriyahu the Governor (or ‘the singer’) wrote it. May Uriyahu be blessed by Yahweh!”

The third line of the inscription has been interpreted in several ways. J. Naveh read: “My guardian and by his Asherah.” A. Lemaire read: “And from his enemies, O Asherata, save him.” All authorities except S. Mittmann, however, read l’ʾšrt—“Asherah” or “Asherata.” The reading is now confirmed by an eighth-century BCE Horvat Teman (Kuntillet ʿAjrud) pithos that has exactly the same expression. It is unclear, however, whether “his (Yahweh’s) Asherah” refers simply to a cult symbol, or to a shrine connected with the Canaanite fertility goddess Asherah, or to the goddess herself, in this case understood, at least in popular folk religion, as the consort of Yahweh. The latter would not be surprising, in view of the prophets’ well-known proscription against pagan religious cults and practices in the period of the divided monarchy.

In the spring of 1971, J. S. Holladay, J. F. Strange, and L. T. Geraty undertook a brief campaign at Khirbet el-Qom for the Canada Council that brought to light a two-entryway gate in a stretch of city wall along the south side of the modern Arab village (field III) on the site. Ceramic evidence dates the latest phase to the seventh century BCE, but the foundations of the gate go back to the tenth to ninth centuries BCE. A rock-hewn cistern, more than 8 m deep, was cleared at the northeast corner of the village (field I). It produced a good collection of ninth-century BCE pottery, including red hand-burnished and Cypro-Phoenician (“Ashdod”) wares. In addition, a stepped, rock-hewn cellar yielded a collection of seventh- to sixth-century BCE pottery, sealed by destruction debris. Below these levels, a stratified series of Early Bronze Age I–III and Middle Bronze Age I domestic levels was encountered.

Field II, in the threshing floor along the southeastern sector of the village near the modern road, produced several Hellenistic rooms in rebuilt Iron Age II houses abutting the outer portion of the Iron Age defense wall. On the floors were several late fourth- to early third-century BCE ostraca, mostly short dockets. Four were in Aramaic, one was in Greek, and one was an Aramaic-Greek bilingual sherd with nine lines. The latter (no. 3) records a transaction between an Edomite shopkeeper named Qos-yada and a Greek named Nikeratos, involving the payment of thirty-two drachmas. The ostracon is dated to the 12th of Tammuz, year 6, probably of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, 277 BCE. In field III, in foundation trenches for the initial Hellenistic rebuilding of the Iron Age II gate, two more Aramaic ostraca were found.