Et-Tell

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Et-Tell | Arabic | التل |

| Khirbet et-Tell | Arabic | |

| Ai | Hebrew | הָעַ |

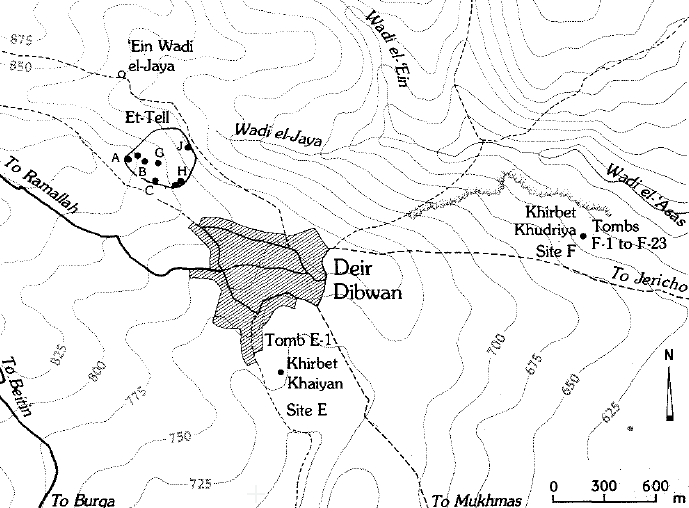

Biblical tradition places Ai in the territory of Ephraim, east of Bethel (Gen. 12:8, Josh. 7:2). Two sites in the vicinity of modern Deir Dibwan, 3 km (2 mi.) east of Beitin (Bethel), were suggested by E. Robinson in 1838 as possible locations of biblical Ai. Et-Tell (map reference 1747.1472) was the obvious choice, but Robinson preferred Khirbet Khaiyan at the southern edge of Deir Dibwan. A third ruin, Khirbet Khudriya, located 2 km (1 mi.) east of Deir Dibwan, was proposed by V. Guérin in 1881.

W. F. Albright published a paper in 1924 advocating et-Tell as the site of Ai. His survey of the region east of Bethel convinced him that no other proposed site could possibly date to the time of the Israelite conquest. The etiological tradition that Joshua “burned Ai, and made it for ever a heap of ruins [tell]” (Josh. 8:28) seemed to support his position. Albright’s identification has not been seriously challenged. Et-Tell, in the view of this writer, is the site of Ai.

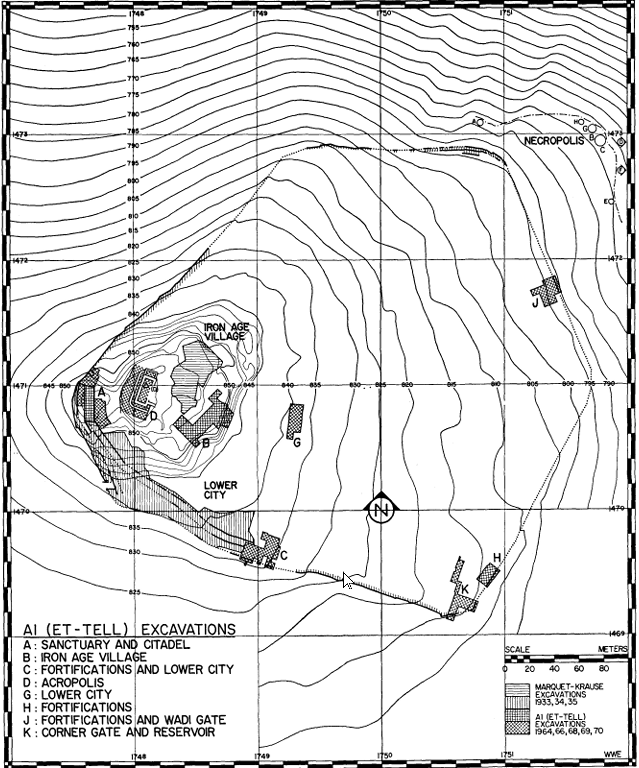

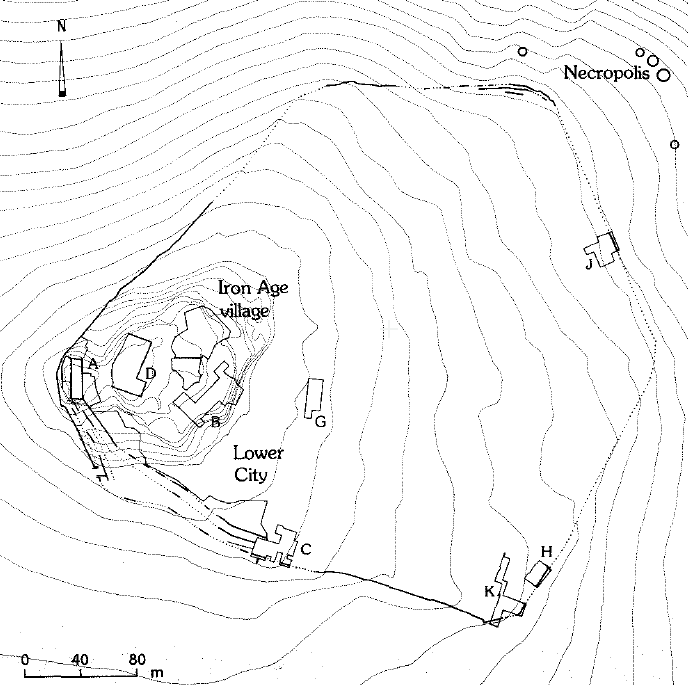

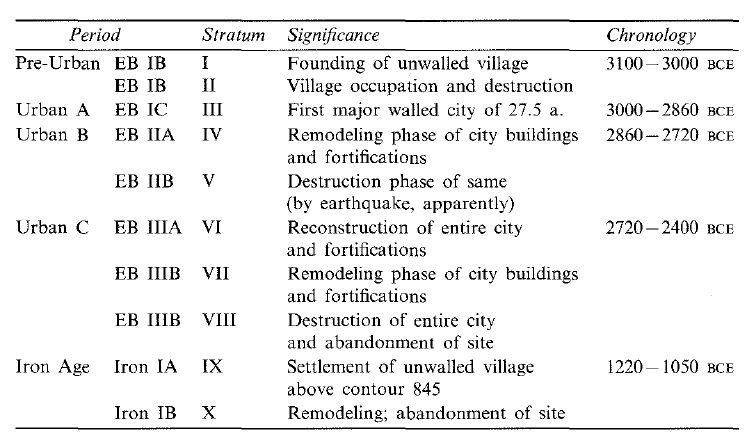

Et-Tell was a city of 27.5 acres, settled in the Early Bronze Age IB (c. 3310 BCE) and occupied until the Early Bronze Age IIIB (c. 2400 BCE), when it was destroyed and abandoned. At the beginning of the Iron Age I (c. 1220 BCE), a 2.5-acre unwalled village was established on the acropolis of the ancient ruin. It was inhabited until about 1050 BCE and then abandoned permanently.

The first brief excavation at Ai/et-Tell was conducted by J. Garstang in the fall of 1928. Eight trenches were dug along the southern and western parts of the Early Bronze Age city, five against the outer face of the city fortifications and three inside, near the sanctuary and acropolis sites. The only report from this excavation was a three-page summary and sketch plan filed with the Mandatory Department of Antiquities at the conclusion of the work. Garstang’s later assertion that Late Bronze Age pottery—specifically, the wishbone handle of a Cypriot bowl—was found in this excavation is not mentioned in his summary report, and the relevant finds cannot be located.

The second excavation project at Ai was the Rothschild Expedition, led by J. Marquet-Krause in three campaigns from 1933 to 1935. Her untimely death in July 1936 abruptly terminated the work. She wrote two preliminary reports. Her husband, Y. Marquet, compiled a register of pottery and objects from the expedition records and in 1949 published it, the two preliminary reports, and an album of photographs, plans, and drawings of artifacts. The Rothschild excavations were confined to the upper part of et-Tell, between contours 835 and 850. Most of the initial expedition in 1933 was concentrated in the acropolis area at contour 850, the highest part of the mound. Some clearing of the sanctuary site west of the acropolis was carried on, and the Early Bronze Age tombs east of the mound were excavated. But 1933 was mainly “the year of the palace,” as Marquet-Krause designated the acropolis building.

An unusually long and productive six-month campaign in 1934 allowed considerable expansion of the excavations. The Iron Age village on the east terraces near the acropolis and the lower-city fortifications near contour 835 were discovered and explored. The main discoveries of 1934, however, were the sanctuary and a rich find of alabaster and pottery cult objects. The 1935 campaign was one of consolidation and extension of the lower city and Iron Age village areas. Fortifications were exposed in the lower city, but the postern, with its elliptical tower, was the most significant discovery. A large area of the Iron Age village was cleared inside contour 850, confirming beyond doubt that the Iron Age I houses were built on the ruins of the Early Bronze Age III city with no intervening occupation strata. For biblical scholars, this campaign was “the year of the Iron Age village.” For those interested mainly in the Canaanite city, however, it was “the year of the postern,” because this was the first entrance found to an Early Bronze Age city in Canaan.

The third archaeological project at Ai was directed by this writer from 1964 to 1970. The expedition was sponsored by the American Schools of Oriental Research in cooperation with other research institutions. Five major expeditions were fielded by 1970, followed by two small problem-solving operations in 1971 and 1972 in areas already open. Eight sites were opened at et-Tell in areas adjacent to the Marquet-Krause excavations and in new areas along the lower eastern fortifications of the city: site A, the sanctuary and citadel; site B, the Iron Age village; site C, the lower-city fortifications; site D, the acropolis; and site G, the lower-city residential area, all above contour 835. Sites H, J, and K were new areas against the lower eastern walls of the city.

Four other sites at a distance from et-Tell were opened to seek evidence bearing on the location of the biblical city of Ai. Khirbet Khaiyan, located at the southern edge of Deir Dibwan, was excavated in 1964 and 1969 as site E. It was found to be a Byzantine settlement, the earliest datable evidence being coins of 68 CE on bedrock. Khirbet Khudriya, east of et-Tell, was excavated in 1966 and 1968 as site F; it was also a Byzantine settlement, possibly a monastery. Tombs adjacent to the settlement yielded pottery and objects from as early as the first century BCE.

Salvage excavations were conducted in 1969, 1970, and 1972 at Khirbet Raddana, at the northern edge of modern Bireh, with sites designated R and S. This project was begun because hewn pillars of two Iron Age I houses, contemporary with those at site B at et-Tell, had been exposed during the construction of a road in Bireh. The evidence of these houses, it was thought, would supplement and perhaps illuminate the Iron Age village at et-Tell. Preliminary study indicated that the sites were indeed contemporary and culturally related.

- Location Map from

Stern et al. (1993 v. 1)

- Location Map from

Stern et al. (1993 v. 1)

- Fig.1 City plan of Ai

(et-Tell) from Callaway & Schoonover (1972)

- Map of the Mound and

Excavation Areas from Stern et al. (1993 v. 1)

- Fig.1 City plan of Ai

(et-Tell) from Callaway & Schoonover (1972)

- Map of the Mound and

Excavation Areas from Stern et al. (1993 v. 1)

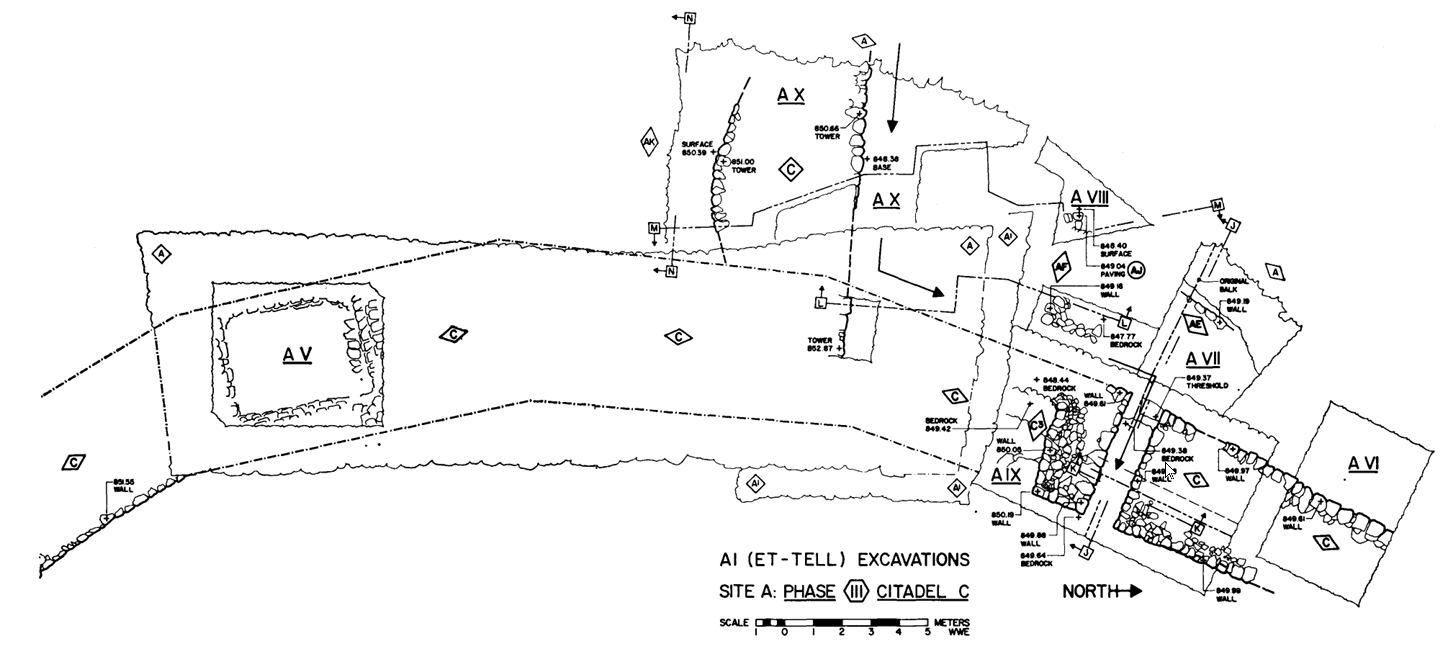

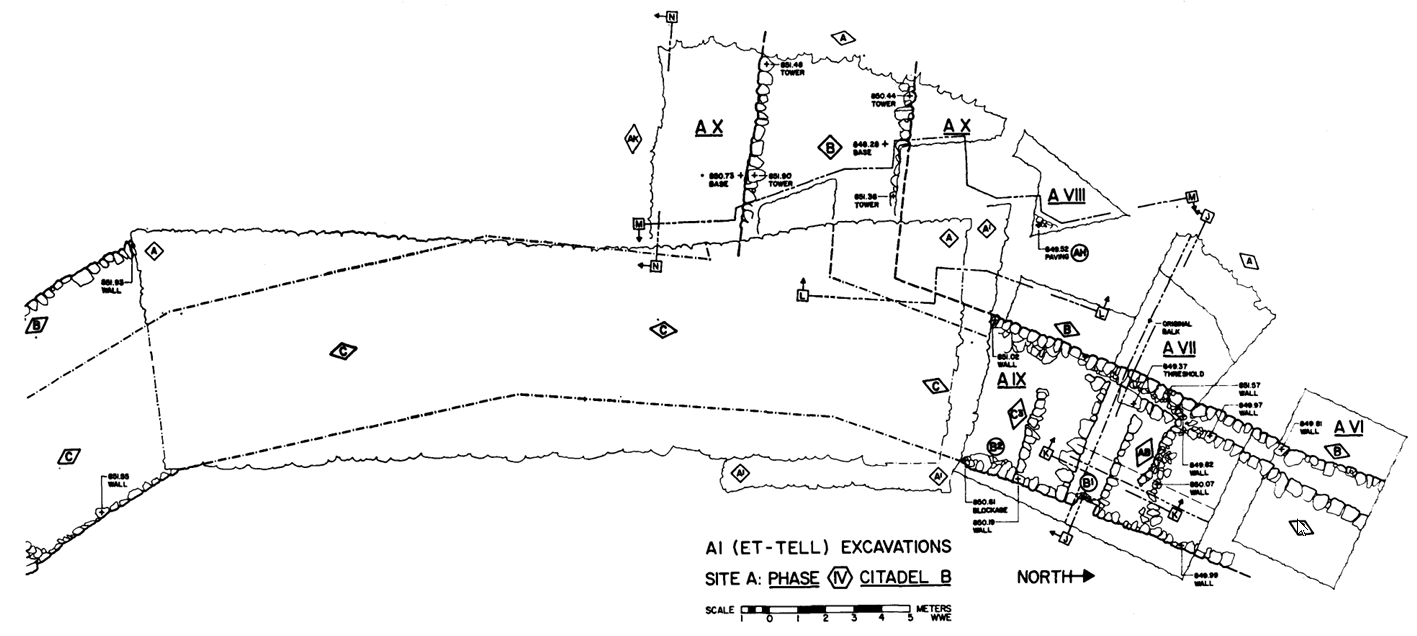

- Fig. 2 The EB IC Citadel

Tower and Gate, Phase III of Site A strata from Callaway & Schoonover (1972)

- Fig. 5 The EB IIA Citadel

Tower and City Wall, Phase IV of Site A strata from Callaway & Schoonover (1972)

- Fig. 2 The EB IC Citadel

Tower and Gate, Phase III of Site A strata from Callaway & Schoonover (1972)

- Fig. 5 The EB IIA Citadel

Tower and City Wall, Phase IV of Site A strata from Callaway & Schoonover (1972)

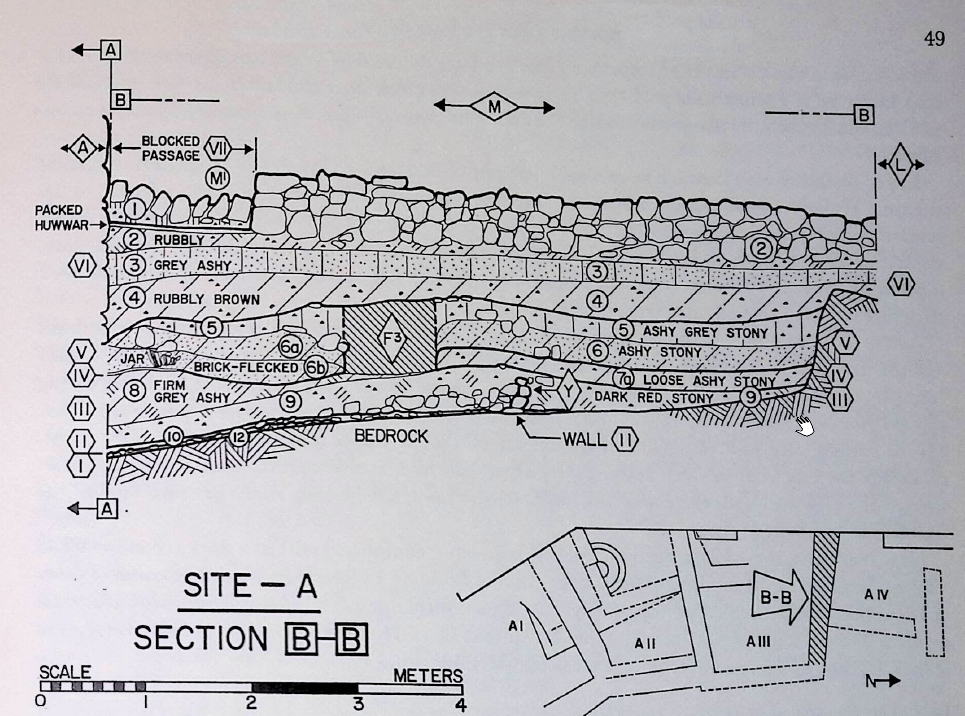

- Fig. 11 Section B-B

from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Fig. 11 Section B-B

from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate IX.2 Phase V

destruction layer in Building B from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate X.1 Phase V

destruction layer in Building B from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate X.2 Crushed Jar

on Building B floor from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

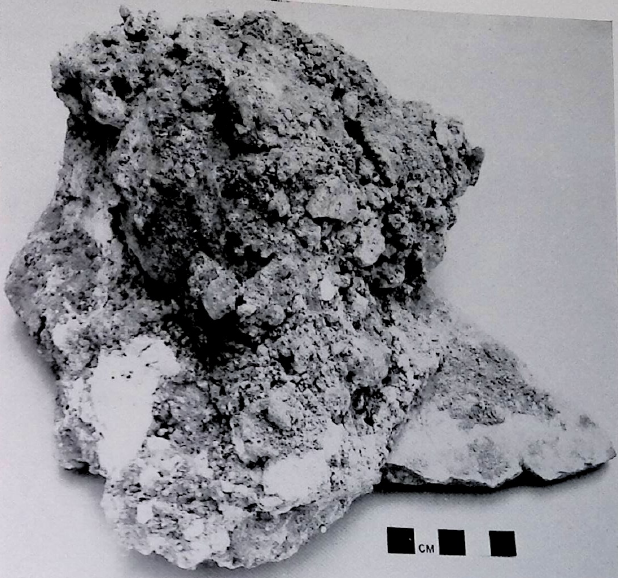

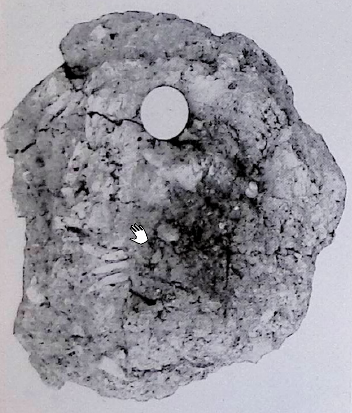

- Plate XV.1 Calcined

mass from Phase V fire from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

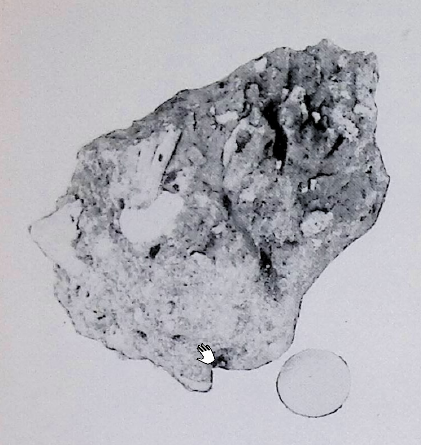

- Plate XVI.1 Leaf

impressions in Phase V destruction Layer from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate XVI.2 Leaf

impressions in Phase V destruction Layer from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate XVI.3 Leaf

impressions in Phase V destruction Layer from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate XVI.4 Leaf

impressions in Phase V destruction Layer from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate IX.2 Phase V

destruction layer in Building B from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate X.1 Phase V

destruction layer in Building B from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate X.2 Crushed Jar

on Building B floor from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate XV.1 Calcined

mass from Phase V fire from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate XVI.1 Leaf

impressions in Phase V destruction Layer from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate XVI.2 Leaf

impressions in Phase V destruction Layer from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate XVI.3 Leaf

impressions in Phase V destruction Layer from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

- Plate XVI.4 Leaf

impressions in Phase V destruction Layer from Callaway and Ellinger (1972)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE |

Table 1

Table 1A chronological scheme for the Levant (after Finkelstein 2010 and 2011; Regev et al. 2012; Sharon 2013).

Palmisano et al. (2019)

A violent disaster brought the Phase IV city at Ai to an end and closed out the first great era in its history. Building B at Site A was completely destroyed and left in ruins. The destruction was radical enough to warrant the designation Phase V, because it was a watershed event in the history of the site. The characteristics of the evidence are as follows:

- Collapsed walls of brick or stone. Bricky debris and stones from the collapse of Wall X and Tower B cover a large jar in Pl. X.2, for instance, to a depth of one-half meter. The scale in front of the jar rests upon a Building B floor, and the destruction debris covers the large stones above the jar as indicated in Section B-B, Fig. II, Layers 5 and 6.

- Calcined wall stones. The intense heat created by burning roof timbers partially, or com-pletely, covered by roofing clay seems to have broken down wall stones into lime. This is particularly evident in the room between Walls Q and W, shown in Pl. IX.1 and 2. A mass of calcined stone rests against Wall Qin the left of Pl. IX.2, and small stones are broken down on the floor across the lower part of the photograph. The calcined small stones are more evident in Pl. X.1 in the lower left corner.

- Cemented masses of pottery solidified into lumps by the calcined stone and other substances producing a molten, lava-like result. A cemented mass is shown in Pl. XV. r, where a small pot, barely discernible in the upper left center, is cemented to the outside of a large store-jar wall fragment. A close-up view of bubble holes on the outside of a store-jar neck and rim left by the molten substances is shown in Pl. X.2.

- Baked lumps of clay with imprints of leaves, twigs, pottery, and stones pressed in the clay. The intense heat seems to have fired the clay to a consistency approaching that of pottery, leaving the imprints sharp and clear, as in Pl. These samples were on the floor shown in Pl. IX.2, in front of the balk.

- Earthquake evidence at Site D, the acropolis. No distinctive evidence of an earthquake was observed at Site A, but the Phase IV outer wall of the acropolis building is tilted outward at a precarious angle from the curve at the northwest corner to the passageway leading into Area D II (see Callaway 1965, 32, Fig. 12, Wall B). This wall was buttressed on the outside and rebuilt in Phase VI, but the tilt was preserved in the rebuilding. The most credible reason for the tilted and partially dislodged wall is an earthquake, and the destruction layer associated with the wall is Phase V.

The beginning of Building B, or Phase IV, was dated to ca. 2860 B.C. based on three Carbon-14 assays—two from roof timbers used in its construction at Site A and one from seeds burned in the destruction of Phase III buildings at Site C. Four additional samples related to the termination of Building B in Phase V and the construction of Building A in Phase VI indicate a date of ca. 2720 B.C. for the end of Phase V at Ai. This places the beginning of EB IIA at ca. 2860 B.C. and the end of EB IIB at ca. 2720 B.C.

The four assays are as follows:

1. TX 1026 A III 204.6 4740 ± 90 2790 B.C.

Charred wood from the courtyard of Building B found on the surface of Layer 5 near Firepit N2, drawn in Section C–C (Fig. 12) and included among the artifacts assigned to Layer 4. The charcoal fragments are probably from Firepit N2 in the courtyard and thus date from near the end of Phase V. Layer 4, as well as Layer 5, derive from the ruins of Building B, but Layer 4 was disturbed in preparing the site for the Phase VI building. Sample TX 1026, therefore, belongs in Phase V and probably near its close.

2. TX 1029 A IV 300.19 4570 ± 120 2620 B.C.

Charcoal fragments in bricky debris between a broken pot and the base of Tower A (Pl. X.2), near the spot where a white tag is pinned in the photograph—close to the surface of the foundation trench for Tower A. The fragments do not appear to be part of the Building B roof but may derive from fires built on the surface of the site before or during the construction of Tower A in Phase VI.

3. TX 1030 C I 1.28b 4830 ± 70 2680 B.C.

Charred seeds from a store-jar in Area I of Site C, Layer 28b, the equivalent of the Phase V destruction layer at Site A. The seeds would have been grown the same year they were burned, so the date reflects the termination of Phase V at Site C. A note in Chapter V (p. 224 n. 2) observes that assay GaK 2381, attributed to C I 2.28b, is of charred wood, not seeds, and therefore probably the same as GaK 2379—an assay of charred wood from D IV 300.5. TX 1030, however, is an assay of the seeds themselves.

4. TX 1031 C IX 800.10 4730 ± 90 2780 B.C.

Charred seeds from a room in Area IX of Site C, near Area I from which sample TX 1030 was taken. Layer 10 of sub-area 800 is nearly contemporary with C I 1.28b and reflects the Phase V period, at or near the destruction horizon.

This cluster of dates bears upon the end of Phase V and the beginning of Phase VI. The spread of ± margins for the four assays is as follows:

1. TX 1026 A III 204.6 2700–2880 B.C.

2. TX 1029 A IV 300.19 2500–2740 B.C.

3. TX 1030 C I 1.28b 2610–2750 B.C.

4. TX 1031 C IX 800.10 2690–2870 B.C.

The mean average of the four assays is 2712 B.C. TX 1026 and TX 1031 are close in both average and margin of error, suggesting no aberrancy. TX 1030 appears reliable with a long count, while TX 1029 is more marginal—its fragments were small and few, giving a shorter count and larger error. The overall impression is that less weight should be given to TX 1029, yet TX 1030, which is slightly lower than TX 1026 and TX 1031, remains significant.

A better average date may be obtained by averaging the lower margins of Nos. 1 and 4 with the higher margins of Nos. 2 and 3, where the nearest point of coincidence among the four dates occurs:

1. TX 1026 A III 204.6 2700–2880 B.C.

2. TX 1029 A IV 300.19 2500–2740 B.C.

3. TX 1030 C I 1.28b 2610–2750 B.C.

4. TX 1031 C IX 800.10 2690–2870 B.C.

The average of the four dates in the center of this column is 2720 B.C., a better result than the simple mean. This date for the termination of Phase V seems acceptable.

In summary, the chronology of Building B—from its beginning in Phase IV to its termination in Phase V—is ca. 2860–2720 B.C., the equivalent of EB IIA–B at Ai. The termination appears to have occurred before the end of the Second Dynasty, as Hennessy (1967, 88) preferred, though he rejected it reluctantly because of the problem of “filling in” the long span left for EB III. There is no serious difficulty with this correlation at Ai for two reasons. First, the termination of Phase V seems to have been caused by a natural disaster—probably an earthquake—rather than a conquest introducing a new cultural period immediately. Evidence for abandonment of Site A for an appreciable interval indicates that the city was rebuilt only after a considerable lapse of time.

Second, there are two city-wall phases at Ai dating to EB III, probably reflecting a duration as long as that of the first two wall phases—about 280 to 300 years. Phases III–V cover the period from 3000 to 2720 B.C., and Phases VI–VIII span nearly, if not quite, the same length of time.

Early Bronze Age IC. A planned, walled city enclosing 27.5 acres was constructed at the beginning of the Early Bronze Age IC (ca. 3000 BCE). Components of the city that are now known are the impressive acropolis building at site D, an industrial area at site C, a residential area at site G, and four city-gate complexes located at sites A, K, and J and in Marquet-Krause’s lower city.

The acropolis complex at site D dominated the Early Bronze Age IC city. Central in the complex was a large rectangular building (ca. 25 m long), built of large, uncut stones and with walls 2 m thick. An entrance, now lost to erosion, apparently opened toward the east in the broad wall of the structure, possibly into a large courtyard. Five flat-top columns inside the building supported the roof of the large hall in the interior. G. E. Wright argued that this building was a temple, against the theory of Marquet-Krause that it was a palace. The former view is supported by later discoveries.

It now seems certain that the same structure, rebuilt in the Early Bronze Age IIIA, was a temple. First, two alabaster bowls, like those found in the Early Bronze Age IIIB sanctuary at site A, were discovered in the Early Bronze Age IIIA rooms of the acropolis building. Second, a large complex of rooms, almost equal in overall size to the central building, has been defined on the west side. This adjoining structure was built on a smaller scale, but two parallel rows of small columns allowed the roof to span about as wide an area as that in the temple. A bench, characteristic of houses in the Early Bronze Age, was constructed against the temple’s west wall, which supported the roof of the second building on the east side. This second building undoubtedly was the residence of the ruler at Ai in the Early Bronze Age IC.

Third, a 2 m wide enclosure wall, constructed in distinct sections around the east side of the acropolis complex, fortified the residence of the ruler. The enclosure seems to join a fortified tower. The enclosure continued in use in the Early Bronze Age II, but the royal residence inside was constricted in size, making the complex larger in the Early Bronze Age IC than at any later period.

Four gates have been discovered in the Early Bronze Age IC city. Three of them—the citadel, postern, and corner gates—were one meter wide, constructed straight through the wall. The walls on each side of the postern passage were 3 m high when excavated, so it is probable that the passage was roofed to stabilize the sides and to add to the security of the gate. The fourth gate at Ai—the valley gate at site J—was only partially excavated in its Early Bronze Age IC phase; the northern half was in the balk, but the exposed part was more than one meter wide, indicating that it was larger than the others.

The first three gates were fortified either by elliptical or semi-elliptical towers in the Early Bronze Age IC. The citadel gate was secured by a tower on its south side, with one straight face along the approach road leading to the gate and an elliptical face on the opposite side. The elliptical tower also fortified the postern. A large circular tower at the southeastern corner of the city, site K, fortified the corner gate. All of the towers were external, built against the outer face of the city walls.

Comparative analysis of the Early Bronze Age IC pottery forms and decoration places this phase in the same cultural context as Jericho phases L–K in areas E–III–IV, tomb A–108; some elements of Garstang’s level V and tomb 24; tomb 14 and periods 1 and 2 at Tell el-Farʿah (North); Lapp’s first urban phase at Bab edh-Dhra; and Arad stratum III. In a wider context, the artifacts in this phase relate to the Late Gerzean and Early First Dynasty in Egypt, Late Amuq F in Syria, and the Jemdet Nasr period in the Upper Euphrates Valley.

Summary. The Early Bronze Age IC city was inhabited by a substantial element of indigenous people whose pottery culture is rooted in the Chalcolithic period. This indicates that the village population in the Early Bronze Age IB probably was absorbed by the newcomers in the Early Bronze Age IC. However, the radical change evident in the new city and in the imaginative planning behind its construction indicates that new leadership was imposed from the outside. Antecedents of this culture can be traced to coastal and northern Syria, as well as southern Anatolia.

In about 2860 BCE, the first great period at Ai was abruptly terminated by violent destruction. The citadel was stormed and burned by an unknown enemy, and the acropolis buildings were burned to the ground. Scorched stones on top of the citadel and a blanket of ash in the acropolis area underlying the Early Bronze Age II buildings attest to the fury of the destruction.

New leadership seems to have been imposed upon the population of Ai, and the city was rebuilt in the third major phase of its history. The construction evidence of this phase is assigned to the Early Bronze Age IIA on the basis of stratified parallels with phases K-ii—H in areas E-III-IV at Jericho; some elements of Arad strata and periods 2–3 at Tell el-Farʿah (North). In the context of the Near Eastern culture area, this relates to the Late First Dynasty in Egypt, from Djer (Albright) or Den (Hennessy and Lapp). To the north, this phase correlates with Amuq G in northern Syria and Byblos III as the sequences are arranged by H. Kantor, although her high chronology is not supported by the carbon-14 assays of materials from Ai.

The culture of the new regime at Ai contrasts with that of its predecessors. Buildings were repaired and modified, and the fortifications were widened and strengthened. Building C at site A, called a sanctuary by Marquet-Krause but probably a dwelling, was remodeled, and a courtyard was added in the east. The citadel gate was closed by an addition of about 0.75 m to the width of wall C, and the postern was closed and discontinued. The lower-city gate, located at Marquet-Krause’s locus 242, was constructed in wall B, presumably because the place was more easily fortified than the postern. The temple at site D seems to have been rebuilt, and the quarters west of the temple were reconstructed to about half the size of the previous building. A wall with curved corners, laid between the two rows of columns in the center of the Early Bronze Age IC structure, enclosed the residential quarters of the acropolis complex on the west side. All these modifications can be described as functional, ad hoc structures with a tendency to retrenchment.

Two distinctive new pottery forms suggest the origins of the new people. The first is a carinated bowl with an outward-curving rim; the second is a jug with a tall, cylindrical neck and high loop handle. These vessels appear to be common at Tell el-Farʿah (North) in the late Early Bronze Age IC, but appear at Ai at the beginning of the Early Bronze Age IIA. The authentic bowl form is not found at Arad, although local imitations occur in stratum II. Most significant, however, is the appearance of the carinated bowl in phase K-ii of the mound at Jericho, which is the destruction layer of the Early Bronze Age IC city. This suggests that the people associated with the carinated form had something to do with the termination of Early Bronze Age IC Jericho; the presence of the form in the construction layers of the Early Bronze Age IIA at Ai indicates that the same people may have participated in its violent overthrow.

A movement from north to south in Canaan is indicated by the pottery, supporting the conclusion that the transition from the Early Bronze Age IC to the Early Bronze Age IIA at Ai was brought about by local conflict rather than by an intrusion from the outside. Ultimately, outside influences can be traced to northern Syria and the coastal cities, but those elements seem to have settled in northern Canaan first.

A disaster of massive proportions brought the Early Bronze Age II city to an end. At every excavated site the buildings and walls were in ruins, and there was generally evidence of fire. Building B at site A collapsed, depositing a half meter of roof-fall and brick debris on its floors. Fire, trapped under the heavy fall, smoldered with enough intensity to break down stone walls into calcined masses. Up to one meter of bricky ruins covered houses at site C, and thick layers of ash lay on the floors of the acropolis complex. The total destruction of everything standing seems to have been caused by an earthquake. Evidence of this is strongest at site D, where a rift in the bedrock through the temple room extends through the north wall, and the stones tilt into the break. The curved wall on the west side of the temple was shifted, and when it was rebuilt in the Early Bronze Age IIIA, the angle of tilt westward was preserved in the reconstruction.

Because the general destruction terminated the Early Bronze Age II city, pottery and artifacts from this phase are assigned to the Early Bronze Age IIB. The pottery horizon compares with phases J–G in areas E–III–V and tomb A–127 at Jericho and periods 3–5 at Tell el-Farʿah (North), although period 5 probably terminated after the destruction at Ai.

A conspicuous new kind of pottery appears in the Early Bronze Age IIB at Ai. The prevailing form is a small juglet of pinkish-orange and light-greenish ware, decorated with alternating horizontal and wavy lines and suspended triangles. This is the Abydos ware known from discoveries at Saqqara in Egypt. Other examples occur at Jericho in tomb A–127, in the Kinneret tomb, and at other sites. A similar decoration appears on large jars at Arad in stratum II. North of Canaan, a crude form of the same decoration is found, for example, at Judeideh in Syria, in Amuq phases G and H.

The Early Bronze Age IIB city at Ai was probably destroyed before the end of the Second Dynasty. A group of four carbon-14 assays yields a date of about 2720 BCE for the termination of the city, or about twenty years before the beginning of the Third Dynasty.

The Early Bronze Age III spans some three hundred years and includes two major phases of city fortifications and buildings. The Early Bronze Age IIIA at Ai is a distinct period of construction, occupation, and destruction, dating from about 2700 to 2550 BCE. After the paralyzing destruction of the Early Bronze Age IIB city, both houses and fortifications required rebuilding. The construction seems to have moved slowly. The city wall at site A was rebuilt first; then the houses inside the walls were built against it. Erosion in the doorway of an Early Bronze Age IIB house suggests that twenty years may have elapsed between the rebuilding of the walls and of the houses inside. A minimum period of rebuilding would therefore be about twenty years, or from 2720 to 2700 BCE, and a maximum could be as much as forty years.

There is positive evidence of Egyptian involvement in rebuilding the city. The evidence is twofold. First, there are construction features in the Early Bronze Age IIIA temple at site D that are best understood if attributed to Egyptian craftsmen. Foremost among these are the raised-top column bases in temple A, which superseded the flat-top bases in temples C and B. The sharply defined rectangular top of the former was shaped by sawing four thin grooves 3 cm deep into the flat-top base. All the stone outside the grooves was then chipped away to the bottom of the cut, leaving the center rectangle 3 cm above the base. Copper saws capable of shaping the raised-top bases are known in Egypt from the reign of Djer in the First Dynasty but are not known outside Egypt.

Another Egyptian feature is the manner of construction of the 2 m-wall of hammer-dressed stones in temple A. The stones are shaped roughly to the size of bricks and laid in mud mortar throughout the thickness of the wall. This unique way of building a wall of stones without a rubble core is Egyptian, dating to the beginning of the Third Dynasty.

The bricklike stone wall of temple A at site D was only the core; a sophisticated plastered surface finished the structure on the inside. Mud mortar, like that between the stones, formed the first layer over the wall. This was covered by a thick layer of hamra, or red clay, mixed with straw for a binder. The finishing layer was fine white plaster over the hamra, extending to a floor made of the same material. Piers of stones set on the raised-top bases probably were plastered in the same manner, giving the temple interior an elegance that points to Egyptian influences.

Additional evidence of Egyptian involvement is the imported alabaster and stone vessels found in the ruins of sanctuary A at site A. These vessels have been associated with First and Second Dynasty parallels in Egypt, and many researchers believe that they were brought to Ai before the time of sanctuary A — the Early Bronze Age IIIB. A careful study of the Early Bronze Age IIIA building at site A that precedes sanctuary A reveals no evidence of cultic vessels or installations. In fact, the building seems to be a dwelling with a courtyard. On the other hand, two alabaster bowls made of materials like those in sanctuary A were recovered by Marquet-Krause from the Early Bronze Age IIIA phase of the temple at site D. R. Amiran later restored the bowls, and she has shown that both are indeed from the temple. Thus, there are cult vessels from temple A in the Early Bronze Age IIIA, suggesting that the alabasters in sanctuary A, dating to the Early Bronze Age IIIB, were moved from temple A to the sanctuary in the transition from Early Bronze Age HIA to IIIB.

There may also be evidence of Egyptian involvement in the construction of the water reservoir at site K in the Early Bronze Age IIIA, but this cannot be demonstrated yet. The reservoir was built inside the southeast bend of the city wall, closing off the corner gate. The system, deceptively simple, consisted of an open, kidney-shaped reservoir built above ground level but designed to capture rainwater channeled from the upper city.

Careful engineering is evident in the structural features of the reservoir. The stone-paved floor was closely laid on a backing of hamra, which becomes practically impermeable when moist. Also, large stones were set into a thick dam of hamra to prevent erosion of the dam’s face. There was one meter of clay behind the upper part of the dam; a thick bed of clay supported the lower part. To provide runoff for any leakage from the dam, a fill of loose stones was placed between the hamra and the city wall. The reservoir has a calculated capacity of more than 1,800 cubic meters, being 25 m wide and 2.5 m deep. The depth changes with the rise in the bedrock to the west, and the east–west size varies because the installation is fitted into the corner of the city wall. A study of water consumption made in an arid region in Lebanon in the 1950s revealed that people there got along very well on one cubic meter of stored water yearly per capita. With the added supply of the small spring in Wadi el-Jaya at Ai, the city could have supported a minimum population of about two thousand inhabitants in the Early Bronze Age IIIA.

Two gates from the Early Bronze Age IIIA city are known. The Early Bronze Age II valley gate had been blocked by an erosion-control dam similar to the one at the reservoir, and a new and smaller gate, fortified by two towers, was constructed on top of the blockage. A second gate was located at site C, in the southern wall of the city. Only the east side of this southern gate remains; the west side was apparently broken down, along with more than 10 m of the city wall, in the assault on the city that terminated the Early Bronze Age IIIA phase.

A major reconstruction of the city at Ai and the citadel site occurred at the beginning of EB IIIA, dated ca. 2700 B.C.24 A new city wall was built outside the existing EB II wall, and the space between was filled with rubble. The outer course of Wall A, EB IIIA, is visible in Fig. 6 at the end of Tower B, where we see the back side of the facing stones. This wall enclosed the area in a gentle curve as shown in Fig. is at the right end of the two-meter scale, and Wall A1, an EB IIIB addition, is at the left end. Tower A, the rectangular citadel structure of EB IIIA-B, is on top of the EB IC-II walls on the right.

A significant change in the form of the citadel tower occurred in the EB IIIA construction. For the first time, the fortification tower is located above the city wall, set back from the outer face of the wall. The same characteristic is evident in the Lower City where Wall A bends around the entire area, enclosing it and creating a strong backing of rubble and earlier walls behind the new fortification. A tower seems to have been built on top of Walls 199/197 where a single course of stones is indicated by heavy lines in P1. C. The same kind of structure is evident also at Site K, where the Corner Gate of EB IC-II is closed off by a curving wall around the outside of the area, and a rectangular, or square, tower is built on top of the enclosed structures. This manner of building towers is new at Ai in EB IIIA, because all previous towers are external, built against the outer face of the city wall.

At Site A, the EB IIIB reconstruction of the city wall is evident in Wall A1, shown in Fig. 7, and the addition of two phases of buttresses to the north end of the citadel tower. The two phases of buttresses are visible in Fig. 8. Tower A, the original construction, is at the right end of the two-meter scale. The first phase of buttressing at the north end of the tower is under the right end of the scale, and a final buttress is under the left end. These two sub-phases of the EB IIIB structure are paralleled at the Lower City in Wall A1 which is built into a buttressed tower at the bend visible in Marquet-Krause P1. C. The irregular faced buttress on the right side of Locus 244, outside the straight buttress shaded with diagonal lines to the left, belongs in the first phase of EB IIIB, and the straight buttress belongs in the second phase.

A massive rectangular tower similar to the EB IIIA citadel at Ai is reported at Taanach25. This tower is assigned to Phase IV by Lapp, or the equivalent of EB IIIB at Ai, but it is the result of a wall strengthening operation at the south end of the city that began in Phase III, or EB IIIA at Ai. The Taanach tower in its final dimensions reached a size of 9.85 by 20.5 m.26, slightly smaller than the citadel at Ai which was about 8.50 by 29.5 m. in the EB IIIA phase, and was buttressed on the north end in EB IIIB to a width there of 10 m., and a total length of 31 m.

One other tower dated to EB III may be associated with the citadel at Ai. Garstang excavated a large rectangular structure built into the east city wall at Jericho, which he assigned to "the Second City (2500–2000 B.C.)."27 The final dimensions of the tower were about "60 ft. by 30 ft.," or near the size of the towers at Ai and Taanach. This tower did have vaults or chambers built into the core, which may have influenced Vincent and Marquet-Krause in thinking there were rooms in the Ai citadel. Unlike the fortifications at Ai and Taanach, the Jericho tower was built into the line of the city wall and projected outward. By the time of the Second City, however, the tell had grown to a considerable height, so that the tower was still above the slope leading up to the supposed gate, and its location commanded a wide area in front and on each side.

Reconstruction of possible cultural movements associated with the new type of citadel towers at Ai, Jericho and Taanach is difficult because the chronology of the three sites cannot be correlated. The EB IIIA citadel at Ai seems to have been built ca. 2700 B.C. in a major rebuilding of the city which bears evidence of strong Egyptian influence. Garstang's date of 2500 B.C. for the Jericho tower may be late, but it is impossible at this point to push the date back with any certainty of being accurate. Also, Lapp's phases III–IV are not dated in the preliminary reports, but he seemed to place them later than the date assigned to EB IIIA at Ai. The rebuilding of the city at Ai seems to have followed a major destruction by an earthquake, and not by enemy action28, so the foothold gained by new leadership, apparently supported by Egyptian resources, may have expanded its influence to Jericho and Taanach, reversing the flow of cultural influence which had been from north to south at the beginning of EB IIA.

24 Carbon 14 assays indicate the beginning of EB IIIA ca. 2700, and the termination of EB IIIB ca. 2400 B. C. at Ai.

See The Early Bronze Age Sanctuary at Ai (et-Tell), pp. 260, 305-7.

25 Paul W. Lapp, op. cit., p. 12; also see p. 6, Fig. 2. The tower outlined in the plan is located on top of Wall

28, set back from the outer face of the earlier walls below, which shape the base of the tell.

26 Ibid., p. 12.

27 John Garstang, The Story of Jericho, pp. 85-8; Fig. 4, p. 50.

28 See Callaway, The Early Bronze Age Sanctuary at Ai (et-Tell), p. 191, for evidence

supporting the conclusion that an earthquake destroyed the EB IIB city, and pp. 247-49

for the arguments for Egyptian involvement in rebuilding the city in EB IIIA.

EB II (3000-2700 BCE)

Ai: “total destruction of everything standing seems to have been caused by an earthquake.” At the Acropolis (Area D, Phase V), a rift in the bedrock of the temple room extends through the north wall and stones tilt into the break. The curved wall in the west side of the temple shifted and when it was later rebuilt, the angle of the tilt was preserved (Callaway 1972: 191). Roof and walls collapsed (Building B, Area A). Debris 0.5-1 m thick covered houses in Area C. Fierce signs of fire. The earthquake put an end to the Early Bronze city. 14C dates the destruction to 2720 BCE (Callaway 1993: 41-42).

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Every Excavated Site |

Fig. 11 Plate IX.2 Plate X.1 Plate X.2 Plate XV.1 Plate XVI.1 Plate XVI.2 Plate XVI.3 Plate XVI.4 |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224) - Environmental Effects (ESI 2007)

- Synoptic Table of ESI 2007

Intensity Degrees from Michetti et al. (2007)

Plate I

Plate I

Synoptic Table of ESI 2007 Intensity Degrees - The accuracy of the assessment improves in the higher degrees of the scale, in particular in the range of occurrence of primary effects, typically starting from intensity VIII, and with growing resolution for intensity IX, X, XI and XII. Hence, in the yellow group of intensity degrees (XI-XII) they become the most effective tool for intensity assessment.

click on image to open a higher resolution version in a new tab

Michetti et al. (2007)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Every Excavated Site |

Fig. 11 Plate IX.2 Plate X.1 Plate X.2 Plate XV.1 Plate XVI.1 Plate XVI.2 Plate XVI.3 Plate XVI.4 |

|

|

Marquet-Krause, J. (1949). Les fouilles de ‘Ay (et-Tell), 1933–1935.

Bibliothèque Archéologique et Historique, Vol. 45. Paris: P. Geuthner.

Callaway, J. A. (1964). Pottery from the tombs at ‘Ai (et-Tell).

Colt Archaeological Institute Monograph Series No. 2. London: B. Quaritch.

Callaway, J. A. and Ellinger (1972). The Early Bronze Age sanctuary at ‘Ai (et-Tell).

London.

Callaway, J. A. (1980). The Early Bronze Age citadel and lower city at ‘Ai (et-Tell):

A report of the Joint Archaeological Expedition to ‘Ai (et-Tell).

ASOR Excavation Reports No. 2. Cambridge, MA.

Callaway, J. A. (1980). The Early Bronze Age citadel and lower city at ‘Ai (et-Tell):

A report of the Joint Archaeological Expedition to ‘Ai (et-Tell).

ASOR Excavation Reports No. 2. Cambridge, MA. - borrow unavailable at archive.org

J. Marquet-Krause, Les Fouilles de Ay (et-Tell), 1933–1935

(Bibliothèque Archéologique et Historique 45), Paris 1949.

J. A. Callaway, Pottery from the Tombs at Ai (et-Tell)

(Colt Archaeological Institute, Monograph Series 2),

London 1964.

id., The Early Bronze Age Sanctuary at Ai (et-Tell),

London 1972.

id., The Early Bronze Age Citadel and Lower City at Ai (et-Tell):

A Report of the Joint Archaeological Expedition to Ai (et-Tell) 2

(ASOR Excavation Reports), Cambridge, Mass. 1980.

W. F. Albright, AASOR 4 (1924), 141–149.

J. Garstang, Joshua–Judges, London 1931, 149–161, 355–356.

S. Yeivin, PEQ 66 (1934), 189–191.

J. Marquet-Krause, QDAP 4 (1935), 204–205; id.,

Syria 16 (1935), 325–345.

R. Dussaud, Syria 16 (1935), 346–352.

M. Noth, PJB 31 (1935), 7–29.

L. H. Vincent, RB 46 (1937), 231–266.

M. W. Prausnitz, Annual Report, Institute of Archaeology,

University of London 11 (1955), 19–28.

J. M. Grintz, Biblica 42 (1961), 201–216.

J. A. Callaway, BASOR 178 (1965), 13–40; id. (with M. B. Nicoli), 183 (1966), 12–19; 196 (1969), 2–16; 198 (1970), 7–31; (with R. E. Cooley), 201 (1971), 9–19; (with K. Schoonover), 207 (1972), 41–53; 213 (1974), 57–61.

id., JBL 87 (1968), 312–320; id., IEJ 19 (1969), 236–239; id., PEQ 101 (1969), 56; 102 (1970), 42–44; (with N. E. Wagner), 106 (1974), 147–155.

id., The Early Bronze Age Sanctuary at Ai (et-Tell) (Reviews), IEJ 27 (1977), 57–58; PEQ 114 (1982), 67–68; BA 39 (1976), 18–30; Archaeology in the Levant (K. M. Kenyon Fest.), Warminster 1978, 46–58; Antike Welt 11 (1980), 38–47; AJA 86 (1982), 133–134; BIAL 19 (1982), 206–208; JNES 46 (1987), 151–153; BAR 9/5 (1983), 42–53; 11/2 (1985), 68–69; The Answers Lie Below (L. E. Toombs Fest.), Lanham, Md. 1984, 51–66; Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation (D. Glenn Rose Fest.), Atlanta 1987, 87–99.

R. Amiran, IEJ 17 (1967), 185–186; 20 (1970), 170–179; BASOR 208 (1972), 9–13; L’Urbanisation de la Palestine à l’Âge du Bronze Ancien (Actes du Colloque d’Emmaüs 1986; BAR/IS 527, ed. P. de Miroschedji), Oxford 1989, 53–60.

K. Schoonover, RB 75 (1968), 243–247; 76 (1969), 423–426; 77 (1970), 390–394.

G. E. Wright, Archäologie und Altes Testament (K. Galling Fest.), Tübingen 1970, 299–319; Biblical Studies in Contemporary Thought (ed. M. Ward), Burlington 1975, 170–187.

Y. Aharoni, IEJ 21 (1971), 130–135.

F. M. Cross Jr. and D. N. Freedman, BASOR 201 (1971), 19–22.

A. Ben-Tor, BASOR 208 (1972), 24–29.

N. E. Wagner, PEQ 104 (1972), 5–25.

J. Briend, BTS 151 (1973), 6–15; American Archaeology in the Mideast, 151–152.

Z. Zevit, BASOR 251 (1983), 23–35; BAR 11/2 (1985), 58–69.

J. J. Bimson and D. Livingston, BAR 13/5 (1987), 40–53, 66–68.

A. F. Rainey, BAR 14/5 (1988), 67–68.

B. Z. Luria, Dor le-Do 17 (1988–1989), 153–158.

E. Braun, PEQ 121 (1989), 1–43.

S. Wimmer, Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 1 (1989), 37–39; id., Studies in Egyptology Presented to Miriam Lichtheim (ed. S. Israelit-Groll), Jerusalem 1990, 1065–1106.

L. E. Stager, EI 21 (1990), 83*–88*.

B. Brandl (1992). The Nile Delta in Transition.

Tel Aviv, 441–477.

Callaway, J. A. (1992). Ai. In

Anchor Bible Dictionary, Vol. I,

New York, 125–130.

Erlich, Z. H. (1992). JSRS 2, v–vii.

Joffe, A. H. (1993). Settlement and Society in the Early

Bronze Age I and II, Southern Levant: Complementarity and

Contradiction in a Small-Scale Complex Society

(Monographs in Mediterranean Archaeology 4). Sheffield.

Fritz, V. (1994). Das Buch Josua

(Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/7). Tübingen.

Livingston, D. (1994). PEQ 126, 154–159;

(2003). Khirbet Nisya: The Search for Biblical Ai,

1979–2002. Excavation of the Site with Related Studies in

Biblical Archaeology. Manheim, PA.

Stone, G. R. (1994). BH 30/1, 11–33.

Van den Bout, T. P. J. (1994). ZAW 84, 60–88.

Mattingly, G. L. (1995). BA 58, 14–25.

Lapp, N. L. (1995). SHAJ 5, 545–554.

Keel, O. (1997). Corpus der Stempelsiegel-Amulette aus

Palästina/Israel, Vol. I, Göttingen, 528–529.

Sasson, A. (1998). Tel Aviv 25, 3–51.

Wimmer, S. (1998). Jerusalem Studies in Egyptology.

Wiesbaden, 87–123.

Bietak, M., & Kopetzky, K. (2000). Synchronisation.

Vienna, 97–98; (2003). Ägypten und Levante 13, 13–38.

Ilan, O. (2001). Studies in the Archaeology of Israel

(D. L. Esse Festschrift). Chicago, IL, 317–354.

Koenen, K. (2003). ZDPV 119, 93–105.

Mazar, A. (2003). Symbiosis, Symbolism and the Power of

the Past. Winona Lake, IN, 85–98.

Rainey, A. (2003). In ibid., 547.

Wood, B. G. (2003). Giving the Sense: Understanding and

Using Old Testament Historical Texts

(eds. D. M. Howard, Jr. & M. A. Grisanti).

Grand Rapids, MI, 256–282.

Merling, D. (2004). The Future of Biblical Archaeology:

Reassessing Methodologies and Assumptions.

Proceedings of a Symposium, 12–14 August 2001,

Trinity International University

(eds. J. K. Hoffmeier & A. Millard). Grand Rapids, MI, 29–42.