Beitin

The ruins of Beitin, the site of ancient Bethel, during the 19th century

The ruins of Beitin, the site of ancient Bethel, during the 19th centuryClick on image to view at a higher resolution in a new tab

Wikipedia - Francis Firth - donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art - CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain

| Transliterated Name | Source/Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Beitīn | Arabic | بيتين |

| Bethel, Beth El, Beth-El, Beit El | Biblical/Hebrew | בֵּית־אֵל |

| Luz | Canaanite? | |

| Bethel | Greek (Septuagint) | Βαιθηλ |

| Bethel | Latin (Vulgate) | Bethel |

| Beitin (modern) | English | Beitin |

The site of ancient Bethel is generally identified with the modern village of Beitin, about 17 km (10.5 mi.) north of Jerusalem. Its identity was first established by E. Robinson in 1838, on the basis of geographical references in the Bible (Gen. 12:8, Jg. 21:19 , for example) and in Eusebius (Onom. 40:20–21) and the similarity of the ancient and the Arabic names. The houses of the modern village are concentrated at the southeast corner of the ancient city, leaving only about 4 a. of the ancient site available for excavation.

In 1927, W. F. Albright, in collaboration with H. M. Wiener, investigated the site. They sank a test pit, which came down upon a massive city wall. Albright’s findings demonstrated that here, indeed, was Canaanite and Israelite Bethel. Although the site had no natural defensive features, it had copious springs and stood at the intersection of major highways — the mountain road and the main road leading from Jericho to the Coastal Plain. Because of these assets, a flourishing town was able to develop. The city of Bethel had been preceded in the area by Ai (q.v.), situated about 2.5 km (1.5 mi.) east of it.

According to the Bible, Bethel was formerly called Luz. It was conquered by the House of Joseph (Jg. 1:22–25) and resettled by the Israelites. Bethel was included in the territory of Ephraim and became a sacred site and religious center associated with the tradition of the patriarchs. Jeroboam I built a royal sanctuary at Bethel as a rival to Jerusalem, but no trace of that sanctuary has been found so far. The city was destroyed by the Assyrians at about the same time as Samaria in about 721 BCE, but the shrine was revived toward the close of the Assyrian period (2 Kg. 17:28–41 ).

Bethel escaped destruction during Nebuchadnezzar's conquest of Jerusalem, but it was probably razed in the transition period between Babylonian and Persian rule. The city was soon rebuilt and was a small town in Ezra's day. It prospered in the Hellenistic and Early Roman periods and was the last city captured by Vespasian before he left Judea to become emperor. It continued to prosper in the Late Roman period and reached its maximum size in the Byzantine period. Shortly after the Arab conquest, however, the city ceased to exist.

- Annotated Satellite View

of Beitin (Bethel) from BibleWalks.com

Annotated Satellite View of Beitin (Bethel)

Annotated Satellite View of Beitin (Bethel)

click on image to explore to open in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Annotated Aerial View

of Beitin (Bethel) from BibleWalks.com

Annotated AerialView of Beitin (Bethel)

Annotated AerialView of Beitin (Bethel)

click on image to open a high resolution image in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Unannotated Aerial View

of Beitin (Bethel) from BibleWalks.com

Unannotated AerialView of Beitin (Bethel)

Unannotated AerialView of Beitin (Bethel)

click on image to open a high resolution image in a new tab

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Beitin in Google Earth

- Beitin on govmap.gov.il

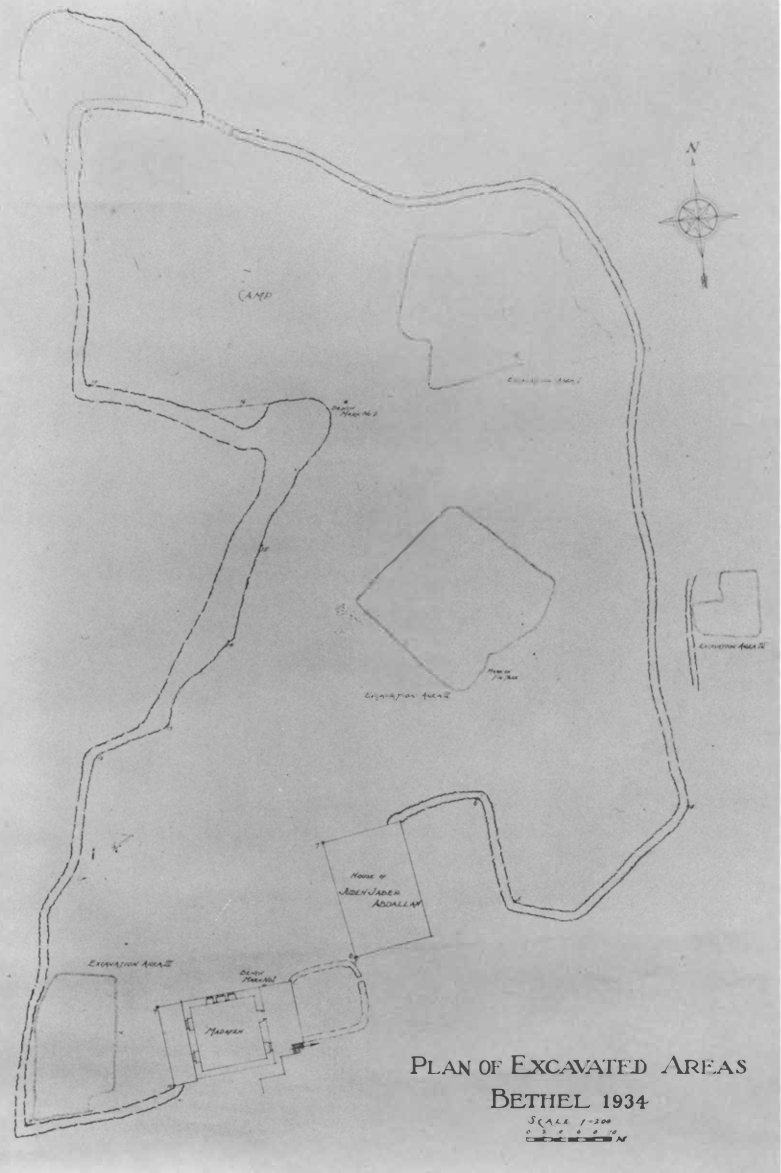

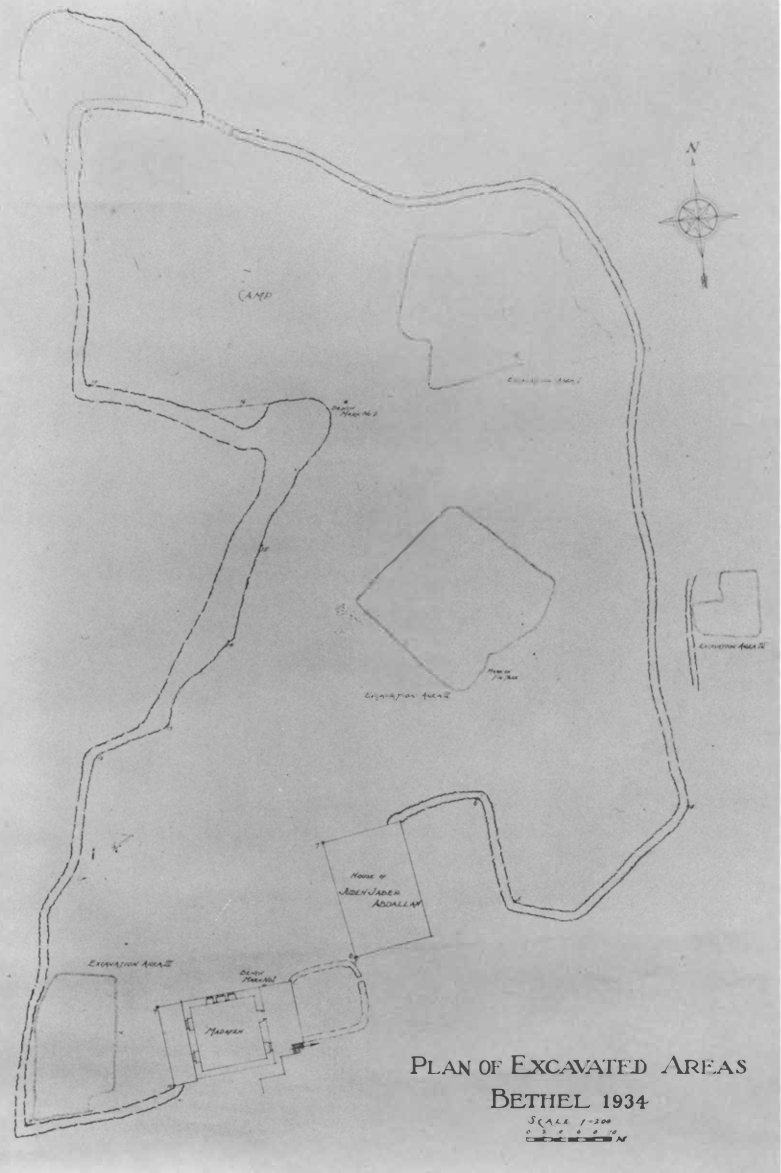

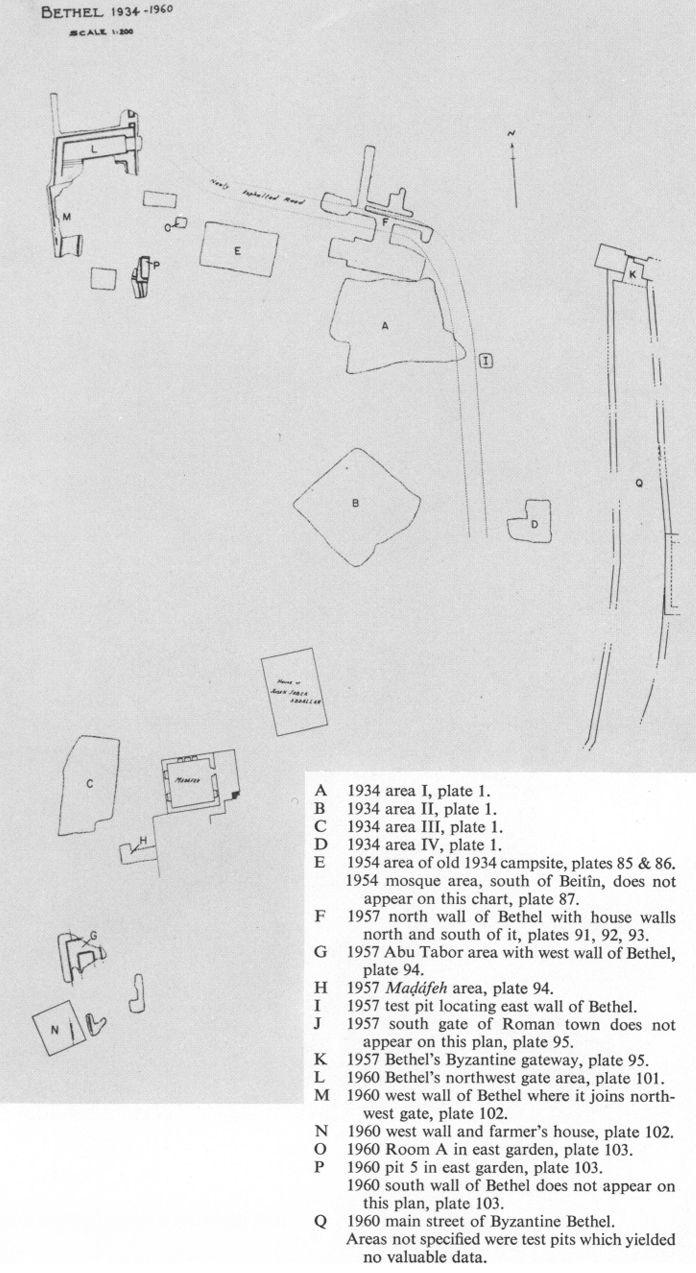

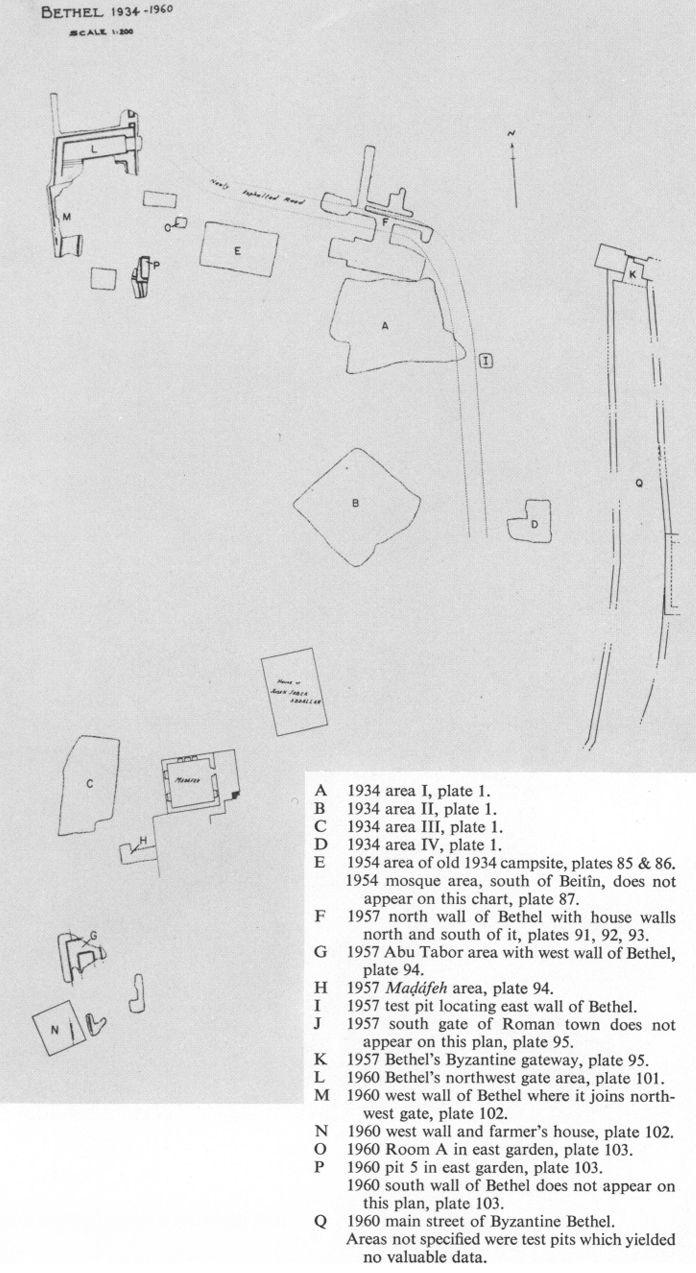

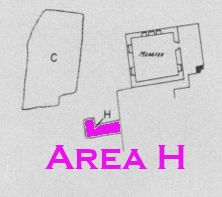

- Pl. 1 Plan of Excavated

Areas Bethel 1934 from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 1

Plate 1

Plan of Excavated Areas Bethel 1934

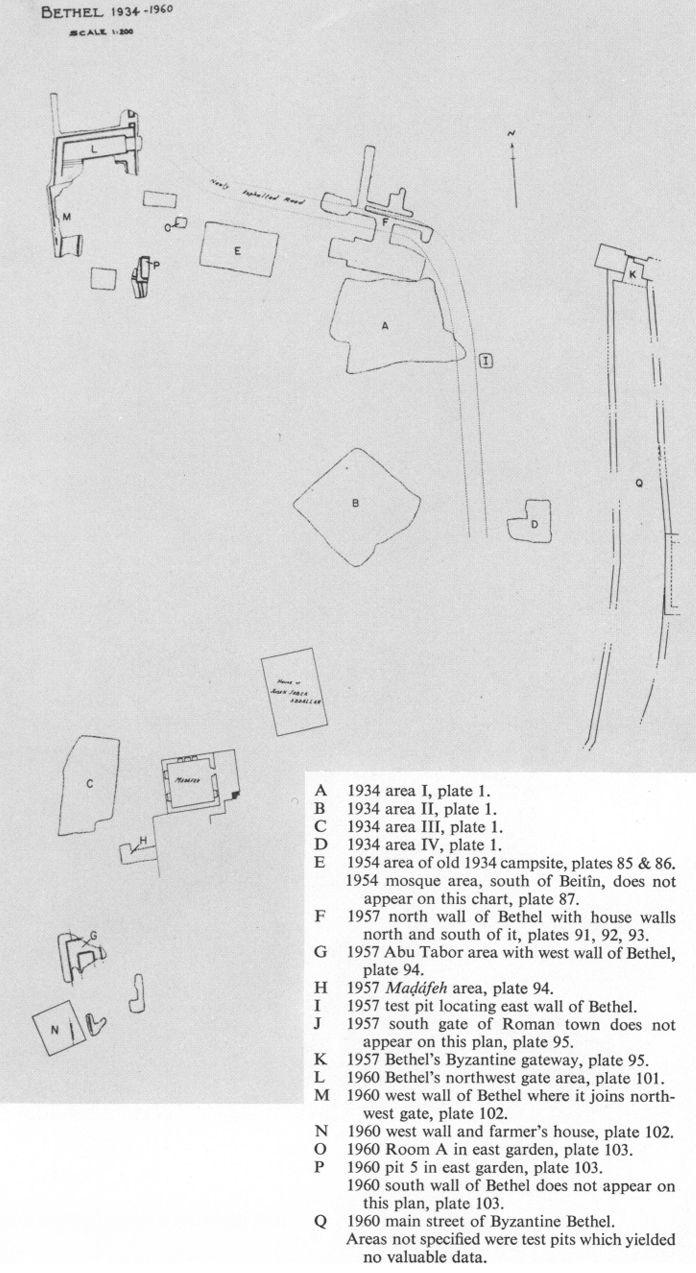

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 120 Plan of Excavated

Areas 1934 through 1960 from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 120

Plate 120

Plan of Excavated Areas 1934 through 1960

Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 1 Plan of Excavated

Areas Bethel 1934 from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 1

Plate 1

Plan of Excavated Areas Bethel 1934

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 120 Plan of Excavated

Areas 1934 through 1960 from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 120

Plate 120

Plan of Excavated Areas 1934 through 1960

Kelso et al. (1968)

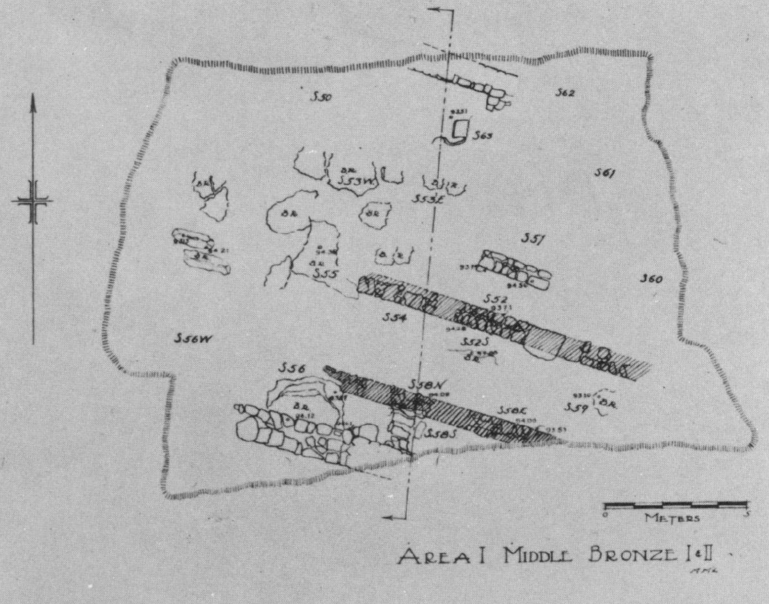

- Pl. 2 Area I - Middle Bronze I and II from Kelso et al. (1968)

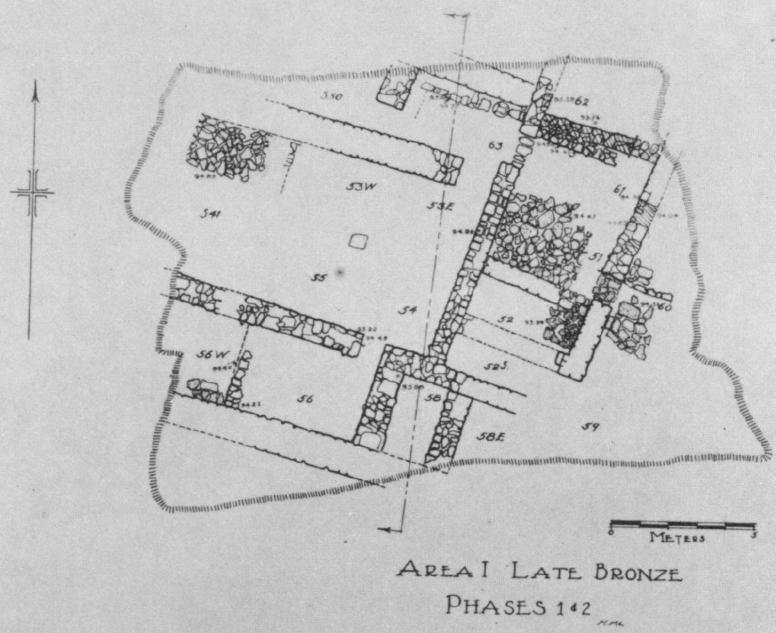

- Pl. 3 Area I - Late Bronze Phases 1 and 2 from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 2 Area I - Middle Bronze I and II from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 3 Area I - Late Bronze Phases 1 and 2 from Kelso et al. (1968)

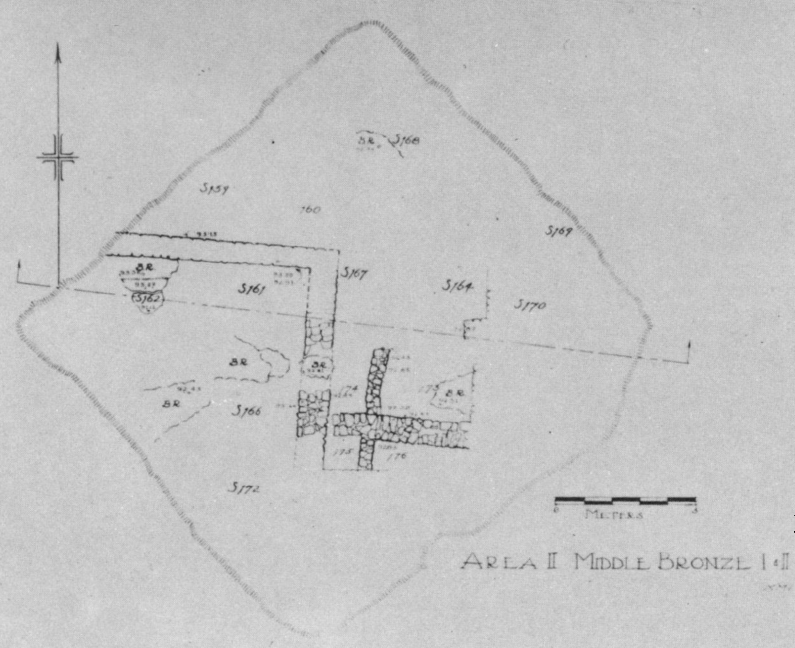

- Pl. 2 Area II - Middle Bronze I and II from Kelso et al. (1968)

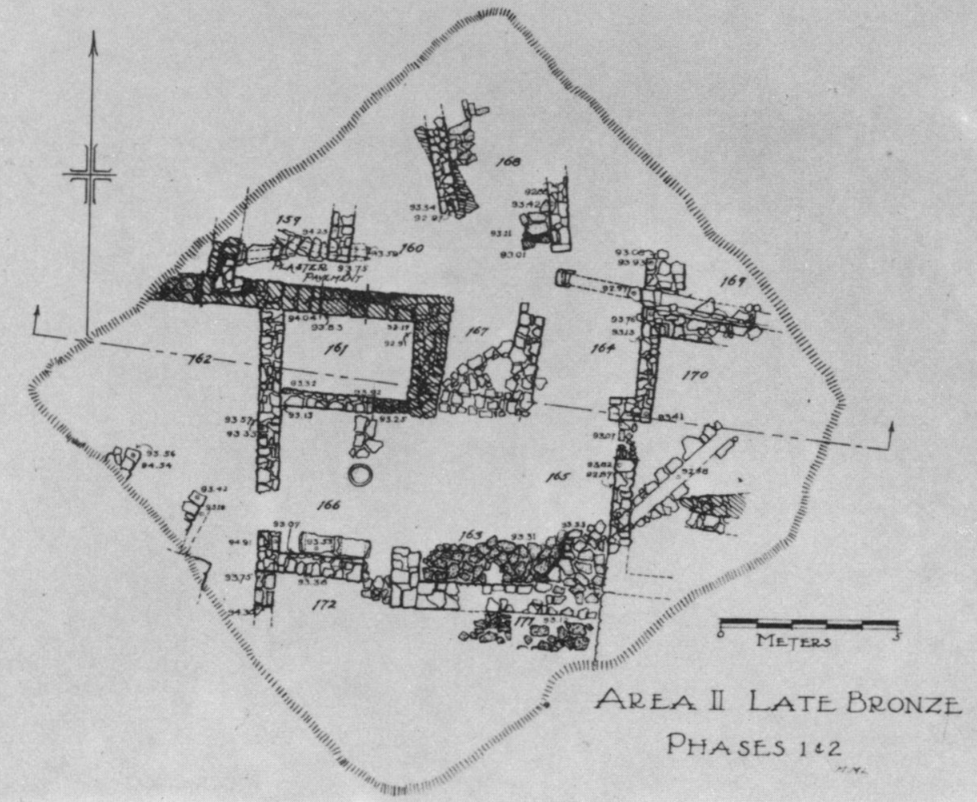

- Pl. 3 Area II - Late Bronze Phases 1 and 2 from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 2 Area II - Middle Bronze I and II from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 3 Area II - Late Bronze Phases 1 and 2 from Kelso et al. (1968)

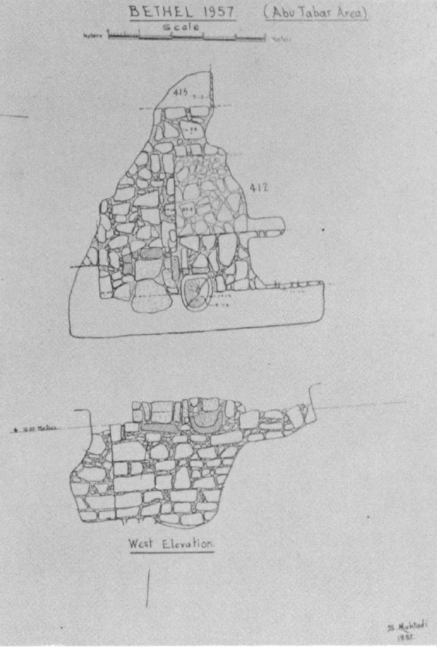

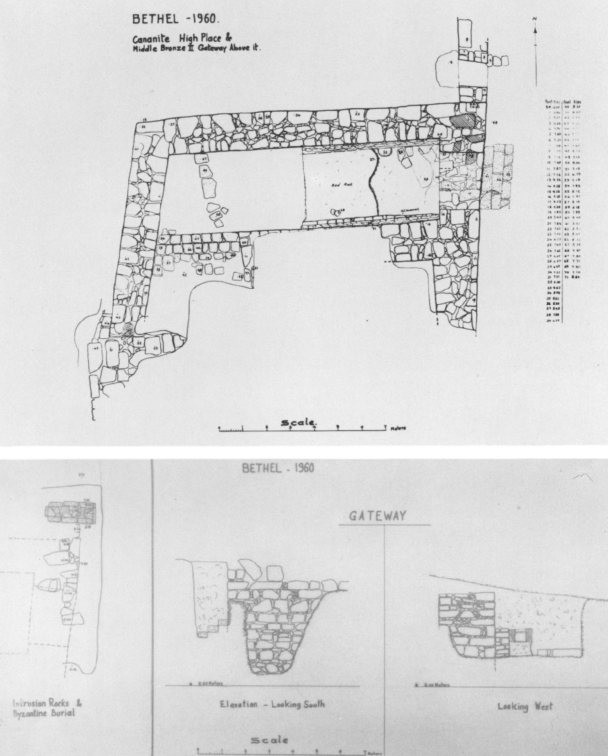

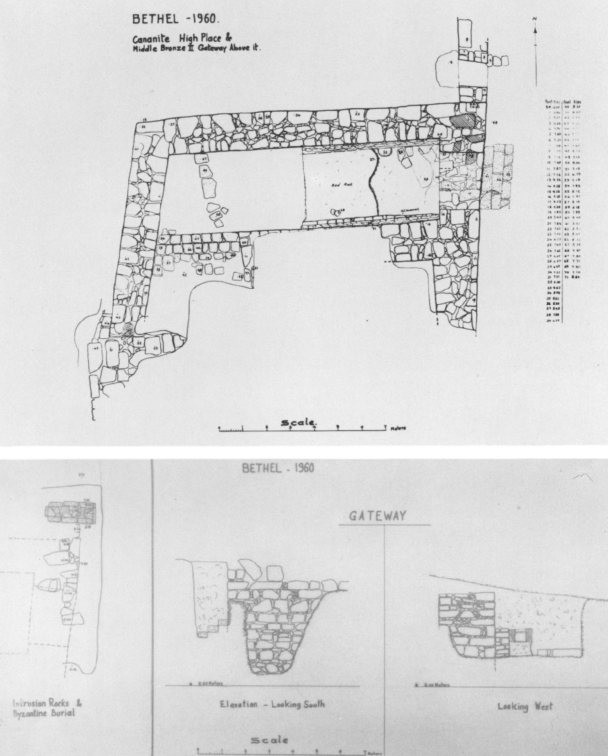

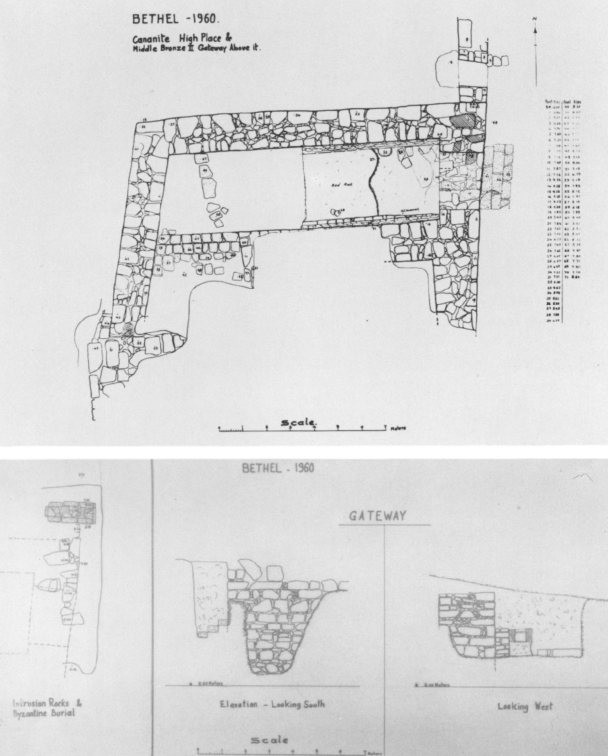

- Pl. 101 Plan and elevations

Middle Bronze II Gateway Complex and Middle Bronze I Cananite high place from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 101

Plate 101

Plan and Elevation of Middle Bronze II Gateway Complex and Cananite high place. The latter is shown in the right half of the long east-weat passageway. The nortwest city gate, with the three steps outside it, is at the east end of the Passageway. Steps also lead up from the west end of the passageway toward the south. Then the gateway turns east. The Haram area lies north of the city gate.

Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 101 Plan and elevations

Middle Bronze II Gateway Complex and Middle Bronze I Cananite high place from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 101

Plate 101

Plan and Elevation of Middle Bronze II Gateway Complex and Cananite high place. The latter is shown in the right half of the long east-weat passageway. The nortwest city gate, with the three steps outside it, is at the east end of the Passageway. Steps also lead up from the west end of the passageway toward the south. Then the gateway turns east. The Haram area lies north of the city gate.

Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 94a West Wall

of City in Abu Tabar area from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 94a West Wall

of City in Abu Tabar area from Kelso et al. (1968)

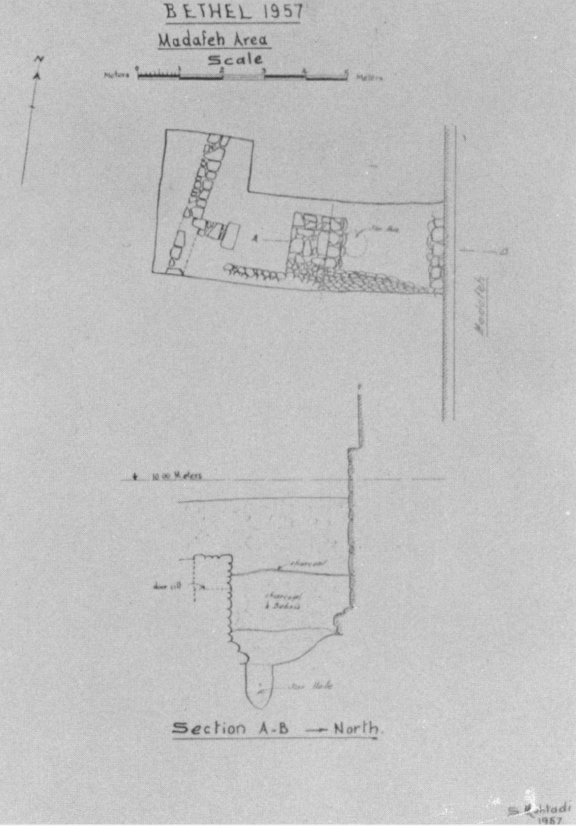

- Pl. 94a Madafeh area from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 94a Madafeh area from Kelso et al. (1968)

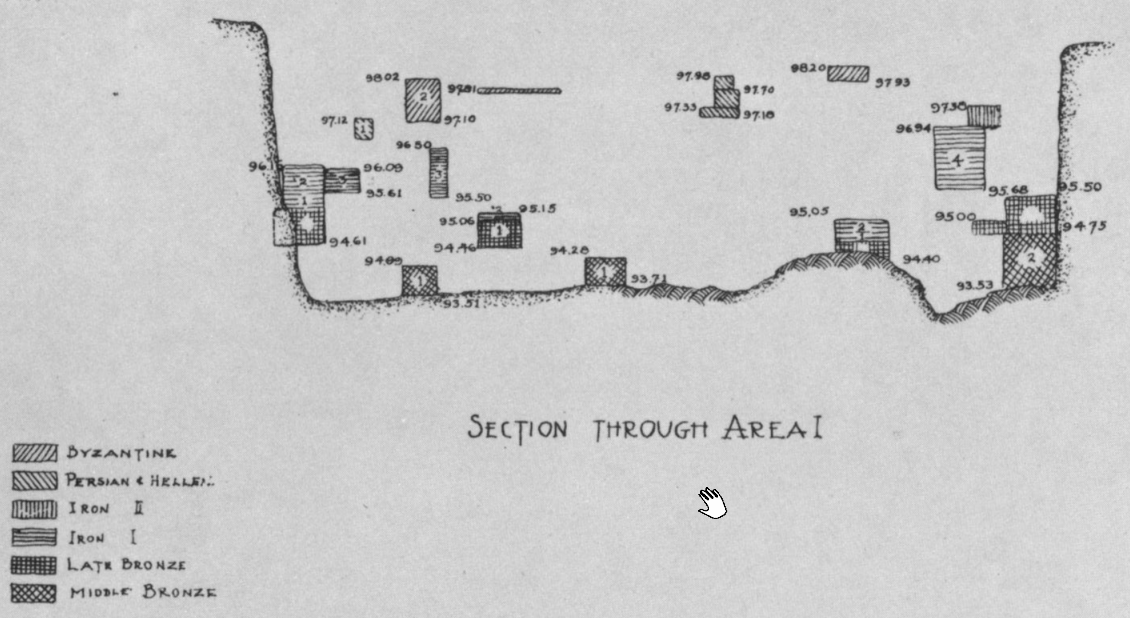

- Pl. 10 Area I Section from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 10 Area I Section from Kelso et al. (1968)

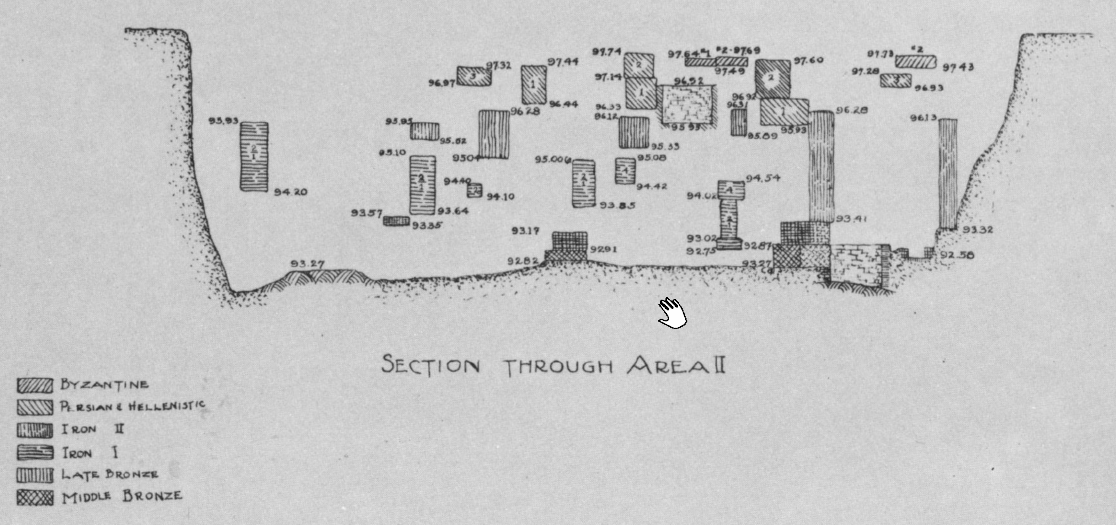

- Pl. 10 Area II Section from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 10 Area II Section from Kelso et al. (1968)

- 19th century photo of

the ruins of Beitin from wikipedia

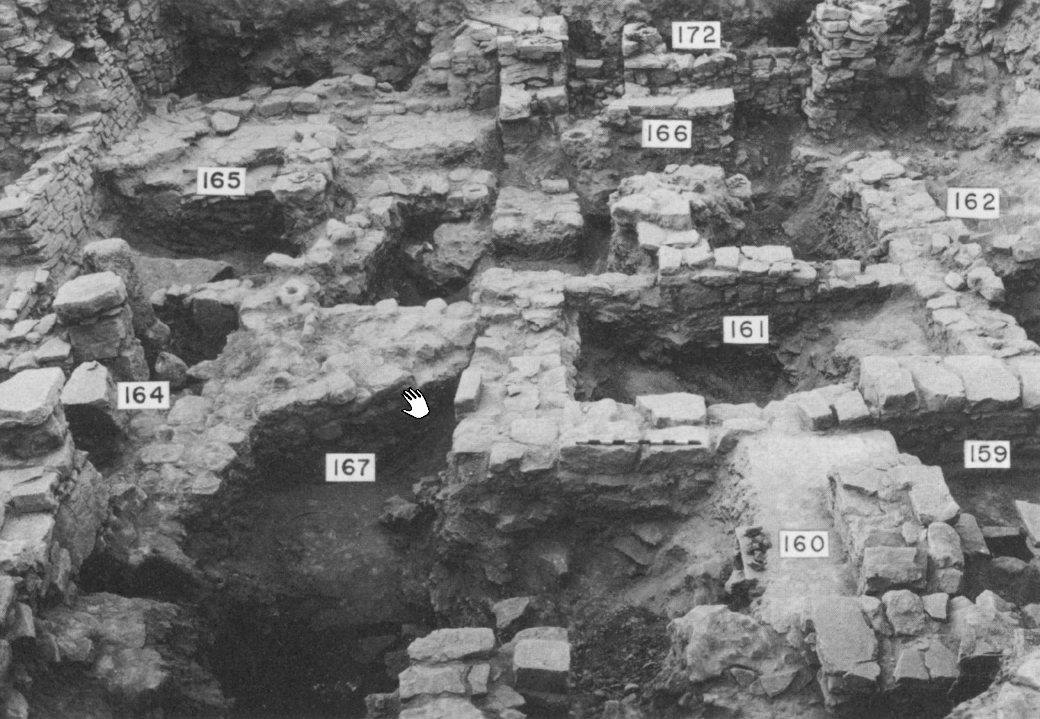

- Pl. 14a Earthquake Collapsed

Wall of LB II phase I from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 14a

Plate 14a

Wall of LB II phase I destroyed by earthquake and left as it fell.

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 14b Thick Ash Layer

from destruction of LB II city in area II from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 14b

Plate 14b

Over a meter of ashes in destruction of LB II city (area II) shown between the wavy black lines

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 15a LB II and MB II

walls from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 15b Area I walls

(MB to Iron I) from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 16a LB II, Iron I,

and Iron II walls in Area II from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 16b Iron I, Iron II,

and Hellenistic walls in LB II area in area II from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 18b Blocked doorway

from phase 2 of LB II from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 18b

Plate 18b

Blocked doorway in north wall of L 161, phase 2 of LB II

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 105c Middle Bronze

II gateway overlying east wall of the MB I Temple from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 105c

Plate 105c

Middle Bronze II gateway, looking east from the passageway after the floor had been excavated. The east wall of the MB I temple with its blocked doorway lies immediately below the gateway

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 106a MB II Northwest city

overlying MB I Temple walls from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 106a

Plate 106a

Northwest city gate above; temple walls immediately below. Huwar floor of gateway in foreground.

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 106b South wall of

MB I Temple from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 106b

Plate 106b

Section of high place rock ledge with south wall of temple and some paving stones of temple floor above the ledge

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 108a South wall of

MB I Temple beneath south wall of MB II city gate from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 108a

Plate 108a

Temple above the high place; south wall oftemple below (with meter stick) and south wall of city gate above. The latter is laid directly on the former.

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 108b North walls of

MB I Temple and MB II city gate from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 108b

Plate 108b

High place ledge and north walls of temple and city gate. West end of the floor of the gates's north corridor is beyond the ledge.

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 109b South jamb of

northwest city gate (Reconstruction) from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 109b

Plate 109b

South jamb of northwest city gate (Reconstruction)

Kelso et al. (1968)

- 19th century photo of

the ruins of Beitin from wikipedia

- Pl. 14a Earthquake Collapsed

Wall of LB II phase I from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 14a

Plate 14a

Wall of LB II phase I destroyed by earthquake and left as it fell.

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 14b Thick Ash Layer

from destruction of LB II city in area II from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 14b

Plate 14b

Over a meter of ashes in destruction of LB II city (area II) shown between the wavy black lines

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 15a LB II and MB II

walls from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 15b Area I walls

(MB to Iron I) from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 16a LB II, Iron I,

and Iron II walls in Area II from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 16b Iron I, Iron II,

and Hellenistic walls in LB II area in area II from Kelso et al. (1968)

- Pl. 18b Blocked doorway

from phase 2 of LB II from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 18b

Plate 18b

Blocked doorway in north wall of L 161, phase 2 of LB II

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 105c Middle Bronze

II gateway overlying east wall of the MB I Temple from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 105c

Plate 105c

Middle Bronze II gateway, looking east from the passageway after the floor had been excavated. The east wall of the MB I temple with its blocked doorway lies immediately below the gateway

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 106a MB II Northwest city

overlying MB I Temple walls from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 106a

Plate 106a

Northwest city gate above; temple walls immediately below. Huwar floor of gateway in foreground.

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 106b South wall of

MB I Temple from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 106b

Plate 106b

Section of high place rock ledge with south wall of temple and some paving stones of temple floor above the ledge

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 108a South wall of

MB I Temple beneath south wall of MB II city gate from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 108a

Plate 108a

Temple above the high place; south wall oftemple below (with meter stick) and south wall of city gate above. The latter is laid directly on the former.

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 108b North walls of

MB I Temple and MB II city gate from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 108b

Plate 108b

High place ledge and north walls of temple and city gate. West end of the floor of the gates's north corridor is beyond the ledge.

Kelso et al. (1968) - Pl. 109b South jamb of

northwest city gate (Reconstruction) from Kelso et al. (1968)

Plate 109b

Plate 109b

South jamb of northwest city gate (Reconstruction)

Kelso et al. (1968)

- from Chat GPT 5, 28 September 2025

- from Kelso et al. (1968)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chalcolithic / Proto-urban | Chalcolithic | – | Earliest material—small finds, jars, minimal architecture. |

| EB Early / Village | Early Bronze (early) | c. 3200 BCE | Village settlement near springs; ephemeral architecture. |

| EB Late / Interruption | Early Bronze (late) | c. 2400–2200 BCE | Reoccupation, followed by abandonment prior to MB I. |

| MB I | Middle Bronze I | Early 2nd millennium BCE | First major continuous phase; temple built on acropolis. |

| MB IIA | Middle Bronze IIA | – | Rebuilding activity around springs; renewal of occupation. |

| MB IIB | Middle Bronze IIB | – | Fortification wall ~3.5 m thick with gates; sanctuary inside. |

| LB I | Late Bronze I | – | Urban phase with pavements, drainage, olive press in situ. |

| LB II | Late Bronze II | 13th century BCE | Smaller, less affluent phase following earlier LB peak. |

| Iron I | Early Israelite | c. 1200–1000 BCE | Crude houses, coarse pottery, temple use declines. |

| Iron II | Monarchic Israelite | c. 1000–586 BCE | Flourishing city, shrine restoration, trade inscriptions. |

| Persian / Continuity | Persian | After 587 BCE | Ongoing occupation; ceramics continuity, no major destruction. |

| Hellenistic Early | Hellenistic (early) | – | Refortification under Bacchides; new tumulus in vicinity. |

| Hellenistic Late | Hellenistic (late) | – | Continued but reduced prominence vs LB period. |

| Roman Early | Early Roman | – | Gate destruction, wall leveling, new gate construction. |

| Roman Late | Late Roman | – | Growth, presence of Roman garrison, cistern expansions. |

| Byzantine Peak | Byzantine | – | Maximum expansion; ecclesiastical structures, urban renewal. |

| Early Islamic Decline | Early Islamic | mid-7th c. CE onward | Site ceases function soon after Arab conquest; decline. |

- culled from James Leon Kelso in Stern et al. (1993 v. 1)

| Phase | Period | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| — | Chalcolithic | — | Single jar in a rock crevice on the acropolis ridge marks the earliest material recovered from the site. |

| — | Early Bronze (early) | c. 3200 BCE | A village grew up near the springs but was later abandoned for much of the Early Bronze Age. |

| — | Early Bronze (late) | c. 2400–2200 BCE | The site was reoccupied briefly before another period of abandonment. |

| I | Middle Bronze I | early 2nd millennium BCE | Continuous occupation begins. A temple with a flagstone pavement was built on the acropolis; it was probably destroyed by an earthquake. |

| IIA | Middle Bronze IIA | — | Rebuilding activity near the springs. |

| IIB | Middle Bronze IIB | — | The entire settlement was encircled by a ca. 3.5 m-thick fortification wall with gates on the northeast and northwest. The northwest gate overlay the ruins of the earlier temple. A sanctuary with cult vessels stood just inside the wall. Two subphases are separated by a distinct ash layer. Egypt may have conquered the town in ca. 1550 BCE. |

| LBI | Late Bronze I | 14th c. BCE | A prosperous urban phase with larger houses, paved streets, and a planned drainage system. An olive oil press was found in situ. |

| LBII | Late Bronze II | 13th c. BCE | A second Late Bronze phase, smaller and poorer than the first. |

| Iron I | Israelite | c. 12th–10th c. BCE | Crude domestic structures and coarse pottery appear. The Canaanite temple went out of use and Astarte plaques became rare. |

| Iron II | Monarchic | c. 10th–6th c. BCE | The city flourished as a major town. A South Arabian seal (c. 9th c. BCE) attests trade. The shrine was rebuilt late in the Assyrian period. Occupation continued into the time of Nabonidus and the early Persian period. |

| Pers. | Persian | after 587 BCE | Occupation continued without a destruction level. Bethel’s ceramic sequence is unique for this reason. |

| Hel.-E | Hellenistic (early) | — | The site regained importance. Bacchides refortified the town. A tumulus (Rujm Abu ʿAmmar) east of the site contained second-century BCE pottery. |

| Hel.-L | Hellenistic (late) | — | Occupation continued but the city was less prominent than in the Late Bronze period. |

| ERom | Early Roman | — | The northeast gate was destroyed and part of the city wall leveled. A house was built over the ruined wall, and a new gate was erected near the earlier south gate. |

| LRom | Late Roman | — | Population increased. Garrisons of Vespasian and Hadrian were stationed here. Cisterns were built to supplement the natural springs. |

| Byz | Byzantine | — | The city reached its maximum size. A large reservoir was constructed, and a main street extended east of the mound. A new northeast gate and east wall were built in 484 or 529 CE to defend against the Samaritans. A large church (later a mosque) and a monastery were constructed. Two other churches were built to commemorate Abraham and Jacob. |

| EI | Early Islamic | mid-7th c. CE onward | The city disappeared shortly after the Arab conquest. |

- from Fall et al. (2023)

Table 1

Table 1Traditional and revised Early and Middle Bronze Age chronologies for the Southern Levant. (Traditional chronology based on Dever 1992; Levy 1995:fig. 3; revised chronology based on Regev et al. 2012; Fall et al. 2021; Höflmayer and Manning 2022.)

Fall et al. (2023)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

38. Bethel was difficult to defend for there were no favorable geographic features such as a high isolated ridge or spur, steep cliffs or deep valleys. §5. Indeed, since these features are strikingly absent, many scholars questioned the identification of Bethel with Beitin; and it was not until 1927, when Albright's test dig located a massive town wall, that the identification became positive.

39. Bethel, however, was blessed with water, lots of water! Immediately below the site there were two copious springs within a long stone's throw of one another, and several lesser fountains were nearby. So much water so close to the top of the central ridge, which carried the main N and S road of Palestine, naturally demanded a city. A copious water supply near the top of the mountains was too rare to neglect. Furthermore, major E and W valleys on either side of the site carried an important road from Jericho and the Jordan valley via the vale of Aijalon and other westward routes to the Mediterranean. Indeed, the eastern valley served as the boundary between Benjamin and Ephraim, and it was up this road that Joshua's invasion entered the highlands.

40. Late in Chalcolithic times (c. 3200 B.C.) a village sprang up just S of the earlier open-air sacrificial high place dedicated to the god El. No signs of fortifications were found. There were no further signs of occupation until late in EB c. 2400—c. 2200 B.C. The former village area was again occupied and also a new site near the largest of the springs. The areas excavated were too small to warrant any conclusions except those of occupation. Et-Tell (Ai) just E of Bethel had been destroyed a little earlier in EB, and Bethel then replaced Ai as the major city of that district. Major installations calling for defense by a town wall appeared in MB I, c. the nineteenth century B.C. This MB I town must have been defended for it had substantial buildings including the temple erected over the old open-air sanctuary § §96 ff. But no town walls uncovered to date can be assigned to MB I. There are a few massive stones wedged against the foundations of the MB IIB temple (?) inside the NW corner of the town that may have come from such a wall. Most of the stones of an MB I wall would naturally have been reused in building the town's great MB IIB wall.

41. Some MB IIA sherds have been found near the N and the S walls of the MB IIB town, but no house walls of this period have been uncovered at the N section of the site. The MB IIA area to the S is still unexcavated although sherds of that period were found mixed with MB IIB debris.

... 52. The first work scheduled for the 1960 dig was the completion of the excavation at the town's NE gate, but on our return we found that during our absence the street above the gate had been paved, and so we were forced to abandon this project. We then turned our attention to the NW area of the site to get the NW corner of the MB IIB town wall, but this area was covered by a high massive rock pile, whose removal slowed our work greatly. We uncovered, however, not only the NW corner of the wall but also a gateway at that point (Pl. 101). Because of the unique nature of this U-shaped gateway in Palestinian archaeology, it was described in great detail in the BASOR, No. 164 (December, 1961) pp. 6–11. The following is only a modest expansion of that report.

53. The NW gate (c. 1650 B.C.) is a rhomboid whose N wall is 14.6 m., the E wall 9.7 m., and the W wall 9.2 m. This building actually had no S wall of its own, but abutted directly upon the outer face of the N wall of the town and thus used the town wall to complete the building complex. The S dimension along the town wall was approximately 15.3 m. The N and W walls (Pl. 104b) were approximately 1.5 m. wide; the E wall, which contained the gateway proper, was irregular in width (narrowing to the S), but approximately 1.75 m. The NE corner of the building was standing c. 5 m. above bedrock. The largest stones used in the building were over 1 m. long. Three stone steps led up to the gateway proper, which was 2.5 m. wide (Pl. 105b). These stairs with a total height of c. 70 cm. were doubtless replacements for they still show sharp corners and only a fair polish from use. The original stones of the threshold are, on the other hand, highly polished from long service. The first and third risers were c. 20 cm. high; the middle one varied from 25 to 30 cm. The lower treads were 35 to 40 cm. deep and the top one 45 to 50 cm. The N jamb of the gate was still standing c. 2 m. high; the S jamb was slightly lower. The latter showed a reconstruction done in semi-dressed stone and was better workmanship than the N jamb (Pls. 105c; 109b). There was no sign of burning here; perhaps earthquake action destroyed the old jamb. The corridor leading W from the gateway was approximately 3.5 m. in width and the N side of the corridor, which was the longer, measured 11.35 m. (Pl. 106a).

54. Most of the floor area was hawar c. 10 to 15 cm. thick with the hawar of the floor in places continuing upward as a thin plaster on the walls. There were nine flagstones in situ near the W end of the corridor and another about the center of it. These suggested that originally the whole area was paved with stone. This original stone pavement theory was later verified for under the hawar at one point was a sterile earth layer about the same thickness, then a double layer of stones well fitted together. These lay on a 30 cm. bed of small stones and earth. At another point beneath the hawar, there was c. 25 cm. of red earth and ash and below that c. 60 cm. of interlocked rocks. A heavy layer of fallen hawar at the W end of the corridor shows that this room had been roofed over or that there had been a second story.

55. The S wall of the corridor which was 1.7 m. wide, continued 8.45 m. westward where it ceased and was replaced for the remainder of the distance to the W wall of the building (3.35 m.) by a stairway consisting of four steps (Pl. 105a). These four steps lead up from the stone pavement of the corridor to a hawar platform 86 cm. above it — an average height of 21.5 cm. to each riser. Because of the angle of the W wall of the gateway, each ascending step increased slightly in length. The top one was 3.85 m. The stairway was in very poor condition but the four steps can be seen in the plan as follows: The first step is represented by 54 and 47; 54 is the original height of that step; 47 has sunk to corridor level by usage. In the second step 55 rises above 54; 56 and 46 have the same relationship as the lower step 47. 64 is the only stone of the third step still in original position; 57, 58, 59, 65, are all foundations for the third step. 63 is the fourth step. 45 is the hawar platform to which the stairs led. In most places the resurfaced platform covered the top step.

56. Two steps with 30 cm. treads (62 and 61), then appeared at the E end of this platform where they apparently led to a second corridor similar and parallel to the N corridor but shorter. Its hawar floor showed up at a point where this corridor ended against the E wall of the building. Because of the great height of the rock pile over the corridor it was impossible to confirm this circumstantial evidence. The corridor must ultimately have made a right angle turn to the S somewhere near the E wall of the building and there pierced the N wall of the town proper. Inside the town wall there is some evidence pointing toward a palace-temple complex, see §§113 f. The U-shaped gateway had no guard room.

57. There was no definite sign of reconstruction except at the S jamb of the gateway where seven courses of excellent semi-dressed stone marked a rebuilding (Pls. 105c; 109b). They contrast sharply with the cruder stones of the N jamb. The S end of the E wall where it must have originally abutted on the N wall of the town, ended in a rough jagged pattern (Pl. 107b). Some of its stone as well as that of the N wall of the town against which it abutted, had been robbed to build the city's defenses in Byzantine times. We tried to reach the foundation course of both walls but it was impossible because of dangerous rock slides. No heavy timbers were available for shoring. The N wall of the gateway building leaned to the N, but we could not tell whether this was due to earthquake action or to irregular pressure from the temple wall directly beneath it which served as its foundation courses. Although the N unit of the gateway pier did not lean as much as the rest of the N wall, the largest stones of the pier showed pressure cracks.

58. The problem of the missing S wall of the building was not solved until we had cut down a large expensive apple tree. Under it we found a wall. The SW corner of the gateway complex was abutting directly upon the town's N wall just 80 cm. short of the NW corner of the town wall (Pls. 102a; 110a). The 80 cm. may have been a buttress or glacis. The stones of the five courses of the W wall of the gateway complex preserved here were not laid in the normal pattern of corner construction but simply abutted directly on the town's N wall of the city. The only object found in the building with the exception of sherds was a beautiful bone handle for a spindle whorl. All sherds found in the gateway complex were MB IIB and C.

59. We date the construction of the gateway about the same time as the town wall and its destruction about the middle of the sixteenth century B.C., probably by the Egyptians after their capture of Jericho, for the main road W out of Jericho in those days ran through Bethel. (Joshua also used this same route.) The building was burned as shown by ashes in the gateway and outside the building. After its destruction, loose rocks were heaped over the entire structure. These rocks averaged c. 30 cm. in size and seldom exceeded 50 cm. There were some small stones and stone chips. The rocks not only covered the structure but formed a talus slope around it. Some of this rock fill still showed that it had been put in from the E and the N. Some grey earth was found, colored by ashes of the burning. The fill was more complex outside the gate and there may have been a revetment there. A modern paved road prevented a more detailed study of this feature. The only sherds found were MB IIB and C; no LB sherds were present although there was an occasional MB I sherd. The absence of LB sherds here is significant in dating the destruction, as these sherds are plentiful inside the town wall just to the S. This type of desecration is most unusual in Palestine. Only the lowest courses of the N wall near the NW corner of the town were in situ but they were similar to the section of the N wall excavated in 1957.

82. In 1934 we dug to bedrock in about one- quarter of the area excavated1. Two baskets of Late Chalcolithic sherds were recovered from pockets of the virgin red earth2. These sherds were identified as Early Bronze in the preliminary report (BASOR). But later study proved them to be Late Chalcolithic similar to the sherds found at Tulul Abu el-‘Alayiq near Old Testament Jericho, the next city SE of Bethel (AASOR, Vols. XXXII–XXXIII, Pls. 21–37). Although no building remains were found, these sherds came from nearly every locus, thus dating the site's earliest extended occupation to Late Chalcolithic c. 3200 B.C.

83. During the 1960 campaign when we dug through the floor of the town's NW gate, we learned that the walls of that gateway complex had been erected directly on those of a temple, and that this building, in turn, was built immediately upon a Canaanite mountain-top high place. This high place was found when we excavated to bedrock directly inside the threshold of the town's gate. When this bedrock was being washed in preparation for photography, we saw that some of it was normal white limestone, some of it was stained red, and part of the rock surface was powdered as if it had been subjected to a very hot fire.

84. Bedrock was very irregular at this point, and the stains were concentrated on the higher ridges or ran down over the faces of the crevices in the rock. When the rock was wetted and then permitted to dry, the stains showed as light pink splotches. This led Taylor, who was in charge of the work at this point, to believe these dark spots splattered about over the cleared area were blood. Majid Bayyuk, a medical student from the American University of Beirut, who was on our staff, secured the chemicals to run the American Federal Bureau of Investigation (F.B.I.) test for blood. Acetic acid in benzidine activated by the addition of hydrogen peroxide to intensify color, and applied to the stains turned them blue or green and proved they were old blood. All the stained areas gave this reaction, but none was obtained from test areas of the white limestone. We next sank a test pit at the extreme W end of the gate corridor and another outside the NW corner of the gateway building in the large huwar courtyard. Stains on the bedrock in both pits were tested and proved to be blood. The widest E–W bedrock area tested was c. 13 m.

85. Much of the bedrock was milk-white and powdery. Pieces broken from it felt much like soapstone. A number of spherical-shaped stones (10–20 cm.) found nearby had a similar texture. This suggested to us that a sacrificial fire had been built on part of the area. We felt sure we had found the old bare mountain top that the Canaanites had used as an open air sacrificial shrine to their god El. To increase the area of the high place open for study, we next cleared everything below the floor level of the entire E half of the N corridor of the gateway complex to bedrock.

86. The irregular surface of the mountain top rises quickly perpendicularly to a ledge whose nearly level surface slopes only gently to the SE. A test pit sunk at the W end of the corridor showed the ledge to be of approximately the same level there. We found some ashes above it and toward the W end of the cleared section, but otherwise the ledge gave no evidence of burning. Dark stained areas concentrated toward the center and W portion of the ledge gave positive blood reaction to the F.B.I. test while the smaller normal white areas of the rock gave negative reactions. The F.B.I. test identifies a stain as blood but does not differentiate between animal and human blood. We could not run the complicated test used to differentiate them. We therefore submitted bone fragments found in the debris above the rock's surface to the surgeons at the Lutheran Hospital on the Mount of Olives. They reported that none of the bones were human. Although Jordan had had a tragic three years' drought prior to 1960, the clay below the huwar floor was very moist. This wet clay doubtless has been a factor in the preservation of the blood stains through the centuries.

87. Under the deep foundations of the floor of the gate corridor, in some areas 85 cm. thick, flints and sherds were found everywhere in great quantity. A variety of forms of flints were found, some of them of types used in butchering or scraping of skins. About 60% of the Chalcolithic sherds found in the extreme E end of the fill near the burned surface of the rock were from cooking pots. There were some EB sherds, but more were MB I representing a wider variety of forms. There were no MB II sherds. In a hollow immediately above bedrock and directly below the center of the E doorway of the MB I temple was a jar identified by Père de Vaux as Chalcolithic. Broken by pressure from the fill above, it contained two small animal bones, one the eye ridges of a skull, the other probably a femur fragment. Although the jar's position might lead to the speculation that it was a foundation sacrifice for the temple built above the high place, the jar is approximately 1500 years earlier than the temple and comes from the time of the original mountain-top shrine. Because the jar is dated at least as early as 3500 B.C., it establishes the earliest firmly dated human use of the Bethel high place as 3500 B.C. although the site was doubtless used much earlier.

88. The only actual installation in connection with this earliest place of sacrifice was a shallow elliptical pit or bin, 55 cm. long and 15 cm. deep. It was on a thin layer of debris just above bedrock and c. 50 cm. E of the ledge. It was made by standing thin slabs of limestone on edge in the ground. They averaged c. 1 cm. thick and 15 cm. in height. The thickest was 2 cm. and the highest 20 cm. There were a few stone slabs on the bottom of the bin, the longest being 22 cm. There were also some pieces of charcoal, the largest 2–5 cm. Some yellow ochre was nearby. The N wall of the temple was built directly over the N half of this bin.

89. This bare mountain-top was the ancient high place where the Canaanites worshipped El, the chief god of the old Canaanite pantheon; and the city became one of his major shrines as witnessed by its name, Beth-el. The antiquity of the site and worship is shown by the continuing use of the name El whereas most Palestinian shrines preferred to honor the new god Baal. Although we did not discover Jeroboam's temple, we did find its ancestral high place. The area excavated at Bethel is too small for exact comparisons with the Jebusite high place at Jerusalem above which Solomon erected his temple, but the ledge at Bethel reminds one of that “rock” in Jerusalem. Although Jeroboam did not build a temple directly on the original Bethel site, the MB I population did, laying their pavement on the ledge itself and aligning their door directly to the E. Furthermore there was what we believe to be a large huwar paved haram area just N of the gateway complex of the MB IIB city. In the debris of various shaped rocks in a field NW of our work was a large stone that may have served as a massebah or sacred pillar.

90. About all that can be said at present of the history of Bethel in the Chalcolithic period is that the NW corner of the site was occupied by a large, well-used open-air sanctuary which can be dated at least as early as 3500 B.C. To the S of that high place and extending along what later became the W wall of the town, there was a settled occupation c. 3200 B.C. The village showed no signs of fortification nor could house walls be traced. This masonry was doubtless all used later in constructing the W wall of the MB II town. All the sherds found belonged to the category of “kitchen ware” and one can conjecture that the new settlers were poor.

91. The ridge E of Bethel was sacred soil, for in 1934 a massebah stood in a roughly squared socket at the nearest point on the ridgeline from the town. Unfortunately the farmers cleared the land of rocks for cultivation before the installation could be studied. On the same ridge S of the Deir Diwan road and near the W edge of the ridge, was an excellent table-shaped stone altar with cup marks. The rock was 2.5 m. long and 1 m. wide at one end and 2 m. at the other. The surface was semi-flat. One cup mark was very shallow, the other deeper. Many flints were strewn about at its base. Some were microlithic. L. Vestri reports another altar on this ridge. Abraham's altar was somewhere on this long N–S ridge, which has a clear view of the Mt. of Olives. A few sherds belonging to the transition from EB to MB I were found at Burj Beitin, the Byzantine identification of Abraham's altar.

1. The figure 20 sq. m. in BASOR, No. 56, p. 3, is a

printer's error. It should read 200 sq. m.; see correction

in BASOR, No. 57, p. 27.

2. For the significant difference between red and black

earth see AASOR, Vol. XVII, §17.

92. During the 1954 campaign no EB floors or walls were discovered, but sherds of late EB, similar to the TBM "J" level, were found in the lowest debris at the old camp site in 305, 308, and 310. Similar sherds were found in test pits in the mosque area close to the springs. Some similar sherds had been washed down from the tell above, and their edges had been abraded in the process. The only new information added by the 1957 campaign was based on the finding of sherds still earlier than those found in 1954. One Neolithic sherd and four Khirbet Kerak sherds (EB III A) were found in the glacis of the W wall of the city. Sherds similar to those of the 1954 campaign were found in the glacis of the N wall as well as the W wall. During the 1960 campaign late EB sherds were also found in the fill of the MB I temple, and in the lowest debris in the NW corner of the town. No building remains were uncovered in any campaign.

The EB age at Bethel (c. 2400 B.C. to c. 2200 B.C.) may be summarized as follows. After the Chalcolithic period the site was abandoned. We could find no clue for the town's disappearance. Four Khirbet Kerak sherds were the only signs of life here until the very close of early EB. The town suddenly came to life showing occupation around the great spring in the mosque area and also in the NW section of Beitin adjacent to the old high place. No building remains were found. Stones from these walls were doubtless used to construct the massive MB II fortifications in the same general area.

93. The EB occupation had ended c. 2200 B.C. and the site was unoccupied until about the nineteenth century, when the first major urban installations still intact were found (Pl. 2). This marks the MB I town. Pottery found in the 1934 campaign was no longer in the red earth but in the black occupation soil. This MB I pottery was succinctly described in the preliminary report3 as follows: "This ware is nearly all thin and free from grits, red-baked or creamy grey in color, with a creamy grey slip. It is decorated with vestigial folded ledge-handles and with elaborate bands of incised design, including horizontal bands, wavy bands, and rows of dots or dashes. This class of ware is identical with that from TBM level H, the Copper Age at Tell el-Ajjol, the extensive parallel remains from Tell ed-Duweir, and Watzinger's Spätkanaanitisch at Jericho. It may be observed that the closest relations of our Bethel ware seem to be with Jericho and Tell el-Ajjol, while the TBM pottery is more or less identical with that at Tell ed-Duweir. There can no longer be any question that this category of pottery continued in use over two centuries, roughly from the 21st to the end of the 19th century."

94. In the southern part of Area I of the 1934 campaign, sections of two parallel walls were found (see hatched lines on plan, Pl. 2a). Their fragmentary nature makes it uncertain whether they outlined a long chamber or were parts of different buildings. Their width (c. 80 cm.) shows substantial wall building. Furthermore, parts of these walls were incorporated into later constructions. In Area II no walls could be attributed to this phase, nor were any walls found in the 1954 or 1957 campaigns.

95. In the 1954 campaign only a few characteristic MB I sherds were found at the old camp site and in the test trenches of the mosque area. They were more numerous in the 1957 campaign, especially in the revetments. For a detailed study of this pottery see §§215 ff., and for other artifacts of MB I see Chapter XVI.

96. In 1960 we had better success with the MB I level. Immediately above the bedrock high place was an MB I building which we are identifying as a temple (Pls. 105c; 106; 108). Apparently the building was identical in size (11.35 × 3.5 m) with the north corridor of the town's northwest gateway, for the lowest walls of the eastern half of the gateway, the only part excavated to bedrock, are laid directly upon the stubs of the temple wall (Pl. 108). A test pit sunk at the western end of the corridor showed the same fill with flints and MB I sherds as at the eastern end.

97. Both the north and south walls of the new structure (Pl. 108) were battered as can be seen on Pl. 101a, although the east wall with its door facing almost due east was perpendicular (Pls. 105c; 106a). The latter wall had a foundation course similar to the south wall. The striking difference between the east wall and the adjacent north and south walls makes us wonder if it is not the result of a repair of the east wall. The blocked doorway in the east wall was about 1 m wide and was well centered — 1.1 m to the north and 1.15 m to the south (Pls. 105c; 106a). The course below the blocking formed the doorsill and established the floor level.

The north wall was still standing 2.25 m above bedrock at the east end but only about 1.5 m above the ledge of bedrock farther west. The lowest course in the south wall was roughly squared stones rising to about 30–45 cm above the ledge and forming a foundation course, wide to the west but narrow to the east. Isolated flagstones (28, 24, etc.) doubtless belonged to this paved floor. Since the building is directly above the blood-stained and calcined high place, and since the flagstones at the western end of the excavation were virtually on bedrock, it seems natural to identify this building as a temple, especially in light of the many cooking pot sherds and butchering flints found in the fill of this building. (The same kinds of flints and sherds were found both above and below the temple floor.) The far end of the room, where the altar and cult objects should be found, has not yet been excavated.

98. We found no exact clue to the date of the erection of the temple except that the town began at the very end of EB and reached quick prosperity in MB I — a prosperity leading us to believe the likely date for the temple's erection is early in MB I. The chief evidence for the date of its abandonment was the flints and sherds which were mostly MB I. No MB II sherds were found in the fill. Since the walls of the town's northwest gate complex were laid directly on the temple walls except at the outer edge of the north jamb, where they were laid on debris, there must not have been a great lapse of time between the abandonment of the temple and the building of the gateway (§§52 ff.). The temple may have been destroyed by fire since a scattering of ashes was found at two points. Perhaps an earthquake toppled it and the new builders used the stubs of the walls as foundations for the new northwest gate.

The temple may have had a longer life than the town proper, for the temple seems to have remained in use longer than the adjacent house walls of the northern area of the town. If so, the temple may have lived through the initial phase of MB II A, which is not true for the northern area of Beitin.

99. The MB I town is dated to about the nineteenth century B.C. The temple described above certainly gives evidence of the town's importance. The few house walls that have been preserved belonged to substantial buildings, and the change of soil from red earth to black shows that there was a much heavier population. The site was doubtless fortified although no defenses have yet been discovered in situ. This is not unexpected, for the MB II builders would likely have used the stone of any former wall and the line of the town's two walls was probably somewhat similar at the northern end of the site. The section of an MB II B building near the town wall was laid in the debris of MB I rocks similar to those used in the MB II B city wall.

3 Cf. AASOR, No. 56, p. 4, and also TBM, §§20 and 23. See also G. E. Wright in BASOR, No. 71 (1938), pp. 27–34. Numerous sites with this pottery have been found by Nelson Glueck east of the Jordan and in the Negeb. Quantities of pottery have been excavated at Khirbet Kerak (Beth-yerah) at the southwest end of the Sea of Galilee. The classical stratigraphic locus for caliciform pottery is now at Hamath where eight phases, covering some four meters of depth, reflect an occupation c. 2100–1850 B.C.; see BASOR, No. 155, p. 32.

100. The northern section of Bethel where we have been excavating houses has only a small amount of pottery corresponding to MB II A. No building installations were found unless, as suggested above, the temple continued in use during the first part of MB II A. Test pits sunk in the southern, or built-up, area of the town might present a different story. MB II A sherds were being found in larger numbers at the base of the southern wall of the MB II B town, and we seemed to be reaching an MB II A level at the time we had to close the 1960 campaign and before we could excavate below that wall.

101. In MB II B Bethel, c. 1700–1650 B.C., reached the status of a full-grown town. In contrast to the structures of preceding periods, MB II B Bethel had stronger, better buildings and excellent defenses (§§42 ff.). The 1934 campaign provided clues to the town's importance in MB II B. Later excavations proved that the walls of the MB II B town were so strong they remained her major defense through most of the rest of Bethel's history.

102. More masonry and pottery were found in the MB II level uncovered in 1934 than in its MB I predecessor (Pl. 2). Two phases of MB II were demonstrated by pottery differences, but no such distinction could be seen in the building remains in Area I. The earlier ceramic phase corresponded to the E level at TBM and is characterized by pottery covered with a highly burnished slip. The later phase must be placed somewhat later than TBM D on typological grounds. Its closest analogy is the latest MB occupation at Jericho, which may be dated about 1550 B.C.

103. The houses excavated tell the following story. At the extreme southern edge of Area I the wall south of sub 564 belonged to MB II. This was shown not only by the large stones, which were quite different from the thin flat ones used in the LB constructions above it (Pls. 15a; 16a), but also by the greater width of the MB wall (1.25 m). This contrast was especially clear where the narrower LB construction reused an MB wall.5 The LB wall between 56 and 58 began at the south by reusing an MB II wall, whose big stones had been bonded into the south MB II wall, but the LB wall quickly changed to typically small flat stones of the first phase. In the south wall of 56 the same was true, but it was difficult to show it on the plans. The south wall of 56 became less and less MB as it ran west, and more and more Iron I in construction, until the MB II wall disappeared completely just east of the LB partition wall separating 56 and 56W. Farther west the wall was entirely rebuilt in Iron I and ran over an LB pavement. In sub 58S there was an MB II pavement with a raised ledge or border of stones on the north. This pavement fitted tightly against the edge of the MB wall. North of sub 63 we found a wall of heavy construction, 1 m wide with a jagged stump of wall projecting from it at right angles at the northeast, where it was broken away by the later north–south LB I wall. The short wall separating sub 51 and sub 52 was also MB II, and reused in LB. All house walls found in 1934 that were 1 m or more in thickness were either MB II or continuations of MB II, whereas the 70–80 cm walls related to them were LB. The 1957 campaign, however, showed thinner MB walls in a poorer area. In sub 63 there was an MB II fireplace and floor level with MB II sherds below and MB plus LB sherds above. The rise of terrain here was so considerable that there must have been either steps or a ramp in it, but we found no clear trace of either in the excavated area.

104. In Area II all MB walls found were attributed to phase 2. The north and east walls of 161 and the west wall of 170 were reused in LB. The doorway between 173 and sub 170 had an MB and two LB phases.6 Some LB pavement in 163 was laid above the north wall of MB 175 and 176. The new wall, number 173 in Pl. 17b, served as a socle with a flat surface on which a mud-brick wall had been erected. For cross-sections of Areas I & II, see Pl. 10.

105. In the 1954 campaign (Pl. 85a), MB II was again represented by a stone socle (Pl. 88c) typical of those built to carry a brick wall (307–308).7 The width of most of the wall was 107 cm, but in places it varied from 103 to 109 cm. This roughly approximated the width of the solid stone walls found in the MB phase of the 1934 campaign. A trench had been dug for the socle, and after the large stones had been laid in place, small stones were wedged in at the edges of the trench. Brick from the wall was in the debris above and beside the foundation. The use of brick in large buildings in the mountainous interior of Palestine was characteristic of the Hyksos period, and the pottery checked with that dating. It was predominantly MB II C rather than MB II B. There was a heavy burning above this socle, telling the story of the destruction of this building and marking the end of MB II. The only MB II floor levels are in 303 and 304; the former room had a hawar floor and the latter a stone pavement. MB II sherds were found at these points, and in 305, 306, 309, and 310. The best MB pottery was found in 310. In 307 and 308 there was evidence of a fierce burning containing bricks and the remains of a collapsed roof under this 107 cm wall. In the debris there was a broken toggle pin as well as MB II B sherds. Similar sherds were found between this level and bedrock. 106. Although there were some indications in the 1934 campaign that the latest MB town had been destroyed by fire, they were not impressive enough to justify a definite conclusion. In the 1954 campaign we did not find enough floor levels to settle this question. The 107 cm wall was, however, destroyed by a fierce fire. There was a section of stone pavement still intact in 305 that probably dates from MB II B, since it was about 50 cm below the other building remains of MB II. A few EB sherds (hand-molded and combed) were found here and below it but no typical MB I sherds were discovered.

107. The best MB II installations were found during the 1957 campaign, and they enabled us to work out the history of this phase of the town's occupation better than in the earlier campaigns (Pl. 91a, b; bench mark is 10.00 m). MB II B pottery similar to the E ware at TBM was found with the first phase of construction (Pl. 91a). These MB II house walls were built on or near bedrock and were contemporary with the erection of the town's north wall. (The surface of the bedrock was irregular.) There was an isolated wall in 406 at the east edge of the excavation, but the other walls were bonded together and formed one large house. One wall of 410 abutted on the town wall. It was six courses high and 70 cm wide while two other walls nearby were 50 cm (Pl. 97a). There was a stone pavement laid on a djawar bed in 410. This first major phase of construction was completely destroyed by fire at the 7.9 m level. There had been an earlier partial burning in MB II B at 7.5 m.

108. The succeeding phase of construction (Pls. 91b, 98b) was MB II C. The pottery associated with it corresponded to D ware at TBM. It was built on a new plan, and the only earlier MB wall carried through into this phase was the isolated one at the extreme east edge of the excavations, which was used only in the first phase of MB II C. The new construction was excellent MB masonry. To be appreciated this masonry must be seen in photographs rather than in the plans, which are often complicated by LB repairs (Pl. 100a).

There were two phases in MB II C, separated by a very thick layer of ashes which at one place was 30–40 cm deep. Only minor changes were introduced into the construction of the second phase. The dominant feature of both phases was a patrician house built around a courtyard (403–406) about 8.6 × 4.25 m in extent. There were two grain pits in the courtyard at pavement level, and a third grain pit in the pavement of 408, which was only about 16 cm higher. The courtyard (403–406) had been repaved. The remnants of a very solid pavement on its south side are 45 cm higher than the earlier and thinner pavement along the north wall. There were two pavements in 408. The one on the plans is about 40 cm above the lower one which apparently belongs to the earlier courtyard pavement. This lower pavement continues under the south wall of LB 408. The pavement in 411 goes with the earlier courtyard.

109. The north wall of the courtyard was 1.4 m wide and the south wall was approximately the same. In phase 2 the north wall was modified so that it was only about half as thick. Against it on the south side two piers stood on the projecting ledge left by the wider earlier wall. We do not know their use. Only the west section of the south wall of the courtyard was preserved. It ended in an excellent door jamb on the east but the other jamb was missing. Opposite, in the next phase, was an isolated pier. The west wall of the court was approximately 75 cm wide with a doorway at each end (Pl. 100a). In the lower left corner of Pl. 98b, this wall is shown in the process of being excavated. Six courses were preserved, with one of the original doorsills which was a single stone. The central section of the upper two courses had been replaced by a very inferior LB repair. The west walls of 407 and 411 were also of excellent masonry and of about the thickness of the wall just mentioned. No walls separated 410 and 411 in the first phase. In the second, a wall between the rooms was extended north to abut on the town wall. This wall, including repairs, was preserved for about ten courses. Because of the cost of removing and replacing the heavy boundary walls along the north street of Beitin, we excavated only this small area along the inner face of the town wall. Room 409 was not dug below the LB level.

110. The east wall of the courtyard marked the eastern boundary of the excavations. Grain pit No. 1 was built directly against it; it was bell-shaped with a maximum width of 1.5 m and a height of 2 m. It was well preserved and contained charred material. The last of these successive MB houses was also burned, unlike the corresponding levels excavated in 1934 and 1954.

111. In the 1960 campaign, just north of the U-shaped gateway and abutting on it, we found the east and south walls of a large MB II B structure which we are tentatively calling a haram area, something like the Dome of the Rock esplanade at Jerusalem (Pls. 101; 107a; 120, upper left corner). Its east wall (3.5 m long) was on the same alignment as that of the northwest town gate. The wall was irregular in thickness but was approximately 1.25 m wide. The doorway (later filled in) was 1 m wide on the outside but wider inside. The south jamb was nine8 courses high. Just west of the door was some stone paving although most of the floor in the area was djawar. We believe there is a blocked doorway at the north edge of the excavation. We were unable to locate the corresponding west wall of this large area although we went some distance beyond the west wall of the adjacent gate complex. At that point we found a second thin djawar pavement 25 cm above the former. We found no cross walls. The whole area was a single unit. We did not locate the north wall, although we dug a narrow test trench (Pl. 120, upper left-hand corner) about 6 m north from the northwest corner of the gateway complex so the area covered by this building was at least 28 × 5 m. We conjecture sections of fallen betwar found upon the floor are accounted for by collapse of the roof of a colonnade built against the north wall of the gateway complex. The large size of this area suggests that it may have been an open courtyard used for worship after the abandonment of the temple which lies underneath the gateway just to the south. A test area still farther to the northwest yielded what may have been a massebah or stone pillar located in a great mass of discarded rocks of all sizes. This courtyard was dated by its MB II B and C sherds to the same period as the adjacent northwest gate, and the courtyard floor was on the same level as the bottom of the lowest step that leads up to the gate.

112. The lower section of the blocked doorway in the east wall of this courtyard area was a normal blocking but the upper section was a Byzantine grave 2.1 m long (Pl. 101b)9. Three well-dressed rectangular stones formed each side of the grave, which was oriented east and west. It was covered by five thin irregular slabs with small stones which filled the cracks.

The contents were unusual. Dr. T. Canaan identified one skeleton as that of a man about 40 years of age, taller than usual for that time and well built. The teeth were in excellent condition. The bones gave no clue to the reason of death. There was also the lower half of the skeleton of a man about 21 years old, and what was apparently his lower jaw, plus another lower jaw of a still younger person. In digging this grave through the talus slope of the rock fill over the city gate, the Byzantine diggers had been troubled by rock slides and the grave was at the bottom of a wide funnel-shaped hole. The funnel-shaped area, however, was not refilled with the rocks removed from it but with earth which contained MB II sherds which sifted into the grave through the cracks between the irregular stone coverings. There was a sort of rock pavement a little above the grave, apparently to discourage hyenas and jackals. The doorway leading east out of this large betwar courtyard went into another djawar-paved area but the wall of this new room was thin — only a single stone wide. This room could not be traced more than three stones when it disappeared under a paved street of modern Beitin.

113. When we first began looking for the west wall near the northwest gate, three test pits were sunk. One pit came down directly over the corner of one of the finest masonry structures yet excavated from early Palestine (see NE room in Pl. 103b). It was made of fine semi-dressed limestone and the section uncovered looks much like the corner of an expensive city church today (Pl. 109a). It had very heavy foundations and a drain at floor level.10 The south wall still stands 3.7 m high, without counting the three foundation courses (1.12 m) which were laid in debris containing MB I sherds and a few from the end of EB. The debris was chiefly massive stones, perhaps from the town's earliest wall. They prevented us reaching bedrock in this pit. The building was probably a palace or temple. The latter identification is based on the pottery found outside the building: a pottery cult stand (patterned after an Egyptian column), a pottery bull's leg, and fragments of two jars with serpent motifs. There were two baskets of animal bones with a heavy proportion of beef bones. Inside the building was a jar handle with a serpent motif. The structure was in use from MB II B through much of Iron II. The north wall was later than the original building but went with the three floors found in the room. The first, a stone pavement later patched with djawar, was 2.8 m below the surface of the ground. LB sherds including bil-bils, milk bowls, and painted ware were found on the floor. Iron II and Iron I sherds had been found earlier but recent farmers had destroyed the floor levels.

114. At 3.2 m sections of a second stone and djawar floor (8–10 cm) and ashes were found. At 3.45 m there was a thinner djawar floor and below it painted pottery in ashes. At 3.62 m the top of the outer face of a wall appeared at the east edge of the pit. It passed under the north wall. Its foundation was at 4.77 m, which is just below the west and south walls proper but above the foundations of the west and south walls. The east wall passed under the north wall. MB pottery was found below the last painted pottery mentioned. (Some MB had appeared with LB a little earlier, especially store-jars.) A large MB II bowl and serpent handles were found at approximately 3.9 m, i.e. the bottom of the west and the south walls proper. This is apparently the floor level of the temple as shown by the drain hole and the beginning of the foundation courses. We did not excavate the northwest room except to discover that its south wall (#9 and #10) was not earlier than Iron II and may be even later. The wall separating the southwest and southeast room was Iron II, as sherds of that period were found in the wall when it was removed. It went down only to 1.86 m. In the north end of the southwest room a djawar floor was found at 2.23 m under the surface, and associated with it at 2.1 m was a very shallow wall (one or two courses only) in the south end of the room. (This wall is not on the plan.) At 2.78 m a djawar floor appeared in both the southwest and southeast rooms. Apparently at that time the area was a single room. This level was approximately the same as the stone pavement in the northeast room. Beneath this floor in the southwest and southeast rooms were at least 15 cm of ashes. No more floor levels appeared in the area but considerable ashes appeared in the debris from 3.10 to 3.75 m. At approximately the top of the foundation courses of the MB II building we found ashes mixed with animal bones, especially beef, a trumpet-foot bowl, a V-shaped drinking cup and cult stand, a pottery bull's leg, and MB II sherds. Inside the building, i.e. the northeast room, at the same level, were the serpent handle and the trumpet-foot bowl. Three other MB II houses were found and they abutted on the town's west wall (§§61, 64, 66).

115. The collective evidence of the four campaigns shows that Bethel was occupied at least in part during MB II A and the whole site was continuously inhabited throughout MB II B and C. The town continued to increase in importance until its fall at the very end of MB II C. The town's defenses which were erected at the beginning of MB II B were so effective that they served Bethel through most of her long history. The best buildings found were the temple just described and the patrician house of the 1957 campaign. The section of the town excavated along the north wall showed traces of enormous fires within MB II B as well as one at its close. In MB II C the same area produced an excellent patrician house. About halfway through the period it was destroyed by a great conflagration but was quickly rebuilt with little change of plan, suggesting that there was no change of population. This building was again destroyed by fire at the close of MB II C, but no similar destruction was found in any of the other areas we excavated. MB II Bethel was a well-to-do community center for local peasants and also a good trading center for semi-nomads, since it was located at a major crossing of north–south and east–west roads. Although MB did produce some excellent masonry the peak of the town's material culture was to come in LB. MB II pottery is treated in Chapter XI and other artifacts in Chapter XVI.

4. The prefix sub signifies that the locus is MB; the

absence of sub in a corresponding locus number

signifies LB.

5. Some MB walls were reused or modified through two LB

phases and on into Iron I.

6. In the LB phase these same rooms are renumbered 165

and 170.

7. Megiddo has similar constructions at this same time,

although at Megiddo they also appeared in earlier levels.

Meg II, Text, p. 97.

8. Two courses were accidentally removed from this pier

before the surveyor got them on the section, and also three

courses from the south pier.

9. See elevation drawing of gateway. Intrusion rocks above

city gateway may have belonged to a Turkish tower.

10. The building was laid on debris containing many rough

field stones but large bracing rocks were leaning against the

foundation courses. We had to break them with sledge

hammers before we could go deeper.

- from Chat GPT 5, 28 September 2025

- from Kelso et al. (1968)

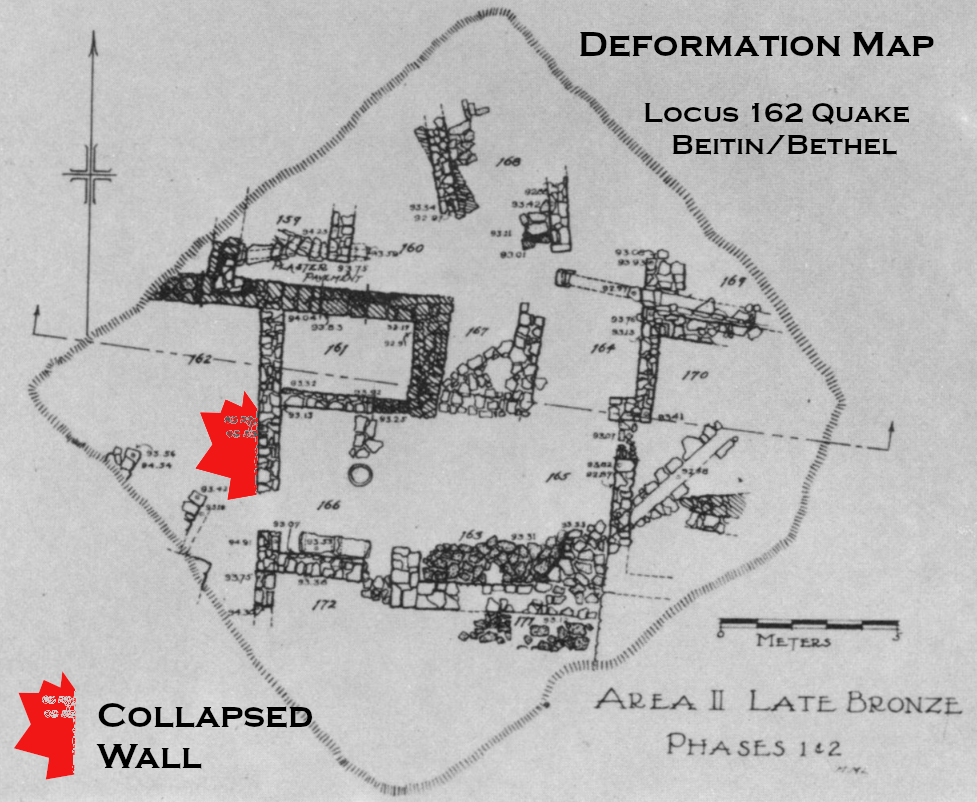

On p. 22, Kelso notes that the debris contained fragments of cultic installations, including an offering table, dislodged and buried beneath collapsed wall material. The orientation of the fallen stones suggests lateral shaking from the northwest, and the abrupt stratigraphic break indicates a single catastrophic event rather than multiple episodes of decay.

Associated stratigraphy shows a clear destruction horizon separating the original Middle Bronze I temple floor from subsequent occupational phases. Above the destruction layer, a new temple superstructure was built with substantial architectural changes, indicating deliberate rebuilding following the disaster (pp. 23–24).

Photo plates III, IV, and VI illustrate the collapsed temple walls, concentrations of fallen masonry, and burial of cultic installations beneath debris. These images provide visual confirmation of the violent nature of the destruction and support its interpretation as the result of an earthquake rather than human conflict.

No weapons, burn layers, or evidence of siege were found in association with the destruction level. The stratigraphic context and architectural damage strongly indicate that the temple’s destruction was caused by a seismic event rather than warfare or abandonment (p. 24).

- from Chat GPT 5, 28 September 2025

- from Kelso et al. (1968)

| Stratum / Phase | Date | Archaeoseismic Evidence | Notes (Interpretation / Sources) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MB I temple (acropolis) | MB I (early 2nd millennium BCE) |

Structure most likely destroyed by an earthquake. | East-oriented, flagstone-paved temple above the acropolis. This is the earliest securely dated seismic event recorded at the site. |

| MB IIB city (sub-phase break) | c. 16th century BCE | — | Two MB II phases separated by a layer of ashes. Reconstruction followed destruction, but the cause was likely military rather than seismic. |

| LB I (Phase 1) | Late Bronze I | Earthquake trace noted in locus 162. | An earthquake signature is documented within Phase 1 destruction debris, although the end of this phase was not catastrophic for the whole town. |

| LB II (Phase 2) | c. 1240–1235 BCE | — | Destruction attributed to a widespread conflagration. No explicit seismic evidence recorded. |

| Iron II wall (Area detail) | Iron II (Monarchic) | Wall had fallen during an earthquake. | Specific mention of seismic collapse in Iron II levels, demonstrating at least one earthquake event during this period. |

| Iron II city end | c. 721 BCE | — | City destroyed in conjunction with the fall of Samaria. Destruction attributed to Assyrian military activity, not an earthquake. |

| Iron II → Persian transition | 553–521 BCE (range) | — | Total destruction occurred between Nabonidus year 3 and the rise of Darius. The cause is uncertain, possibly political or military rather than seismic. |

| Early Roman gate | Early Roman | — | Northeast city gate destroyed and adjacent wall leveled. A new gate was built nearby. No signs of burning, and no direct seismic evidence cited. |

MB IIB (1750-1550 BCE)

Bethel: Temple destroyed in a fire or earthquake, mid-16th century BCE (Albright and Kelso 1968:14,23)

38. Bethel was difficult to defend for there were no favorable geographic features such as a high isolated ridge or spur, steep cliffs or deep valleys. §5. Indeed, since these features are strikingly absent, many scholars questioned the identification of Bethel with Beitin; and it was not until 1927, when Albright's test dig located a massive town wall, that the identification became positive.

39. Bethel, however, was blessed with water, lots of water! Immediately below the site there were two copious springs within a long stone's throw of one another, and several lesser fountains were nearby. So much water so close to the top of the central ridge, which carried the main N and S road of Palestine, naturally demanded a city. A copious water supply near the top of the mountains was too rare to neglect. Furthermore, major E and W valleys on either side of the site carried an important road from Jericho and the Jordan valley via the vale of Aijalon and other westward routes to the Mediterranean. Indeed, the eastern valley served as the boundary between Benjamin and Ephraim, and it was up this road that Joshua's invasion entered the highlands.

40. Late in Chalcolithic times (c. 3200 B.C.) a village sprang up just S of the earlier open-air sacrificial high place dedicated to the god El. No signs of fortifications were found. There were no further signs of occupation until late in EB c. 2400—c. 2200 B.C. The former village area was again occupied and also a new site near the largest of the springs. The areas excavated were too small to warrant any conclusions except those of occupation. Et-Tell (Ai) just E of Bethel had been destroyed a little earlier in EB, and Bethel then replaced Ai as the major city of that district. Major installations calling for defense by a town wall appeared in MB I, c. the nineteenth century B.C. This MB I town must have been defended for it had substantial buildings including the temple erected over the old open-air sanctuary § §96 ff. But no town walls uncovered to date can be assigned to MB I. There are a few massive stones wedged against the foundations of the MB IIB temple (?) inside the NW corner of the town that may have come from such a wall. Most of the stones of an MB I wall would naturally have been reused in building the town's great MB IIB wall.

41. Some MB IIA sherds have been found near the N and the S walls of the MB IIB town, but no house walls of this period have been uncovered at the N section of the site. The MB IIA area to the S is still unexcavated although sherds of that period were found mixed with MB IIB debris.

... 52. The first work scheduled for the 1960 dig was the completion of the excavation at the town's NE gate, but on our return we found that during our absence the street above the gate had been paved, and so we were forced to abandon this project. We then turned our attention to the NW area of the site to get the NW corner of the MB IIB town wall, but this area was covered by a high massive rock pile, whose removal slowed our work greatly. We uncovered, however, not only the NW corner of the wall but also a gateway at that point (Pl. 101). Because of the unique nature of this U-shaped gateway in Palestinian archaeology, it was described in great detail in the BASOR, No. 164 (December, 1961) pp. 6–11. The following is only a modest expansion of that report.

53. The NW gate (c. 1650 B.C.) is a rhomboid whose N wall is 14.6 m., the E wall 9.7 m., and the W wall 9.2 m. This building actually had no S wall of its own, but abutted directly upon the outer face of the N wall of the town and thus used the town wall to complete the building complex. The S dimension along the town wall was approximately 15.3 m. The N and W walls (Pl. 104b) were approximately 1.5 m. wide; the E wall, which contained the gateway proper, was irregular in width (narrowing to the S), but approximately 1.75 m. The NE corner of the building was standing c. 5 m. above bedrock. The largest stones used in the building were over 1 m. long. Three stone steps led up to the gateway proper, which was 2.5 m. wide (Pl. 105b). These stairs with a total height of c. 70 cm. were doubtless replacements for they still show sharp corners and only a fair polish from use. The original stones of the threshold are, on the other hand, highly polished from long service. The first and third risers were c. 20 cm. high; the middle one varied from 25 to 30 cm. The lower treads were 35 to 40 cm. deep and the top one 45 to 50 cm. The N jamb of the gate was still standing c. 2 m. high; the S jamb was slightly lower. The latter showed a reconstruction done in semi-dressed stone and was better workmanship than the N jamb (Pls. 105c; 109b). There was no sign of burning here; perhaps earthquake action destroyed the old jamb. The corridor leading W from the gateway was approximately 3.5 m. in width and the N side of the corridor, which was the longer, measured 11.35 m. (Pl. 106a).

54. Most of the floor area was hawar c. 10 to 15 cm. thick with the hawar of the floor in places continuing upward as a thin plaster on the walls. There were nine flagstones in situ near the W end of the corridor and another about the center of it. These suggested that originally the whole area was paved with stone. This original stone pavement theory was later verified for under the hawar at one point was a sterile earth layer about the same thickness, then a double layer of stones well fitted together. These lay on a 30 cm. bed of small stones and earth. At another point beneath the hawar, there was c. 25 cm. of red earth and ash and below that c. 60 cm. of interlocked rocks. A heavy layer of fallen hawar at the W end of the corridor shows that this room had been roofed over or that there had been a second story.

55. The S wall of the corridor which was 1.7 m. wide, continued 8.45 m. westward where it ceased and was replaced for the remainder of the distance to the W wall of the building (3.35 m.) by a stairway consisting of four steps (Pl. 105a). These four steps lead up from the stone pavement of the corridor to a hawar platform 86 cm. above it — an average height of 21.5 cm. to each riser. Because of the angle of the W wall of the gateway, each ascending step increased slightly in length. The top one was 3.85 m. The stairway was in very poor condition but the four steps can be seen in the plan as follows: The first step is represented by 54 and 47; 54 is the original height of that step; 47 has sunk to corridor level by usage. In the second step 55 rises above 54; 56 and 46 have the same relationship as the lower step 47. 64 is the only stone of the third step still in original position; 57, 58, 59, 65, are all foundations for the third step. 63 is the fourth step. 45 is the hawar platform to which the stairs led. In most places the resurfaced platform covered the top step.

56. Two steps with 30 cm. treads (62 and 61), then appeared at the E end of this platform where they apparently led to a second corridor similar and parallel to the N corridor but shorter. Its hawar floor showed up at a point where this corridor ended against the E wall of the building. Because of the great height of the rock pile over the corridor it was impossible to confirm this circumstantial evidence. The corridor must ultimately have made a right angle turn to the S somewhere near the E wall of the building and there pierced the N wall of the town proper. Inside the town wall there is some evidence pointing toward a palace-temple complex, see §§113 f. The U-shaped gateway had no guard room.