Ashkelon

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Ascalon | Hebrew | אַשְׁקְלוֹן |

| Ascalon | Koine Greek | Ἀσκάλων |

| Ascalon | Latin | |

| Ascalon | Philistine | |

| Ashkelon or Ashqelon | Hebrew | אַשְׁקְלוֹן |

| ʿAsqalān | Arabic | عَسْقَلَان |

Ascalon (aka Ashkelon) has a long history of occupation going back to the Neolithic.

Ashkelon is situated on the Mediterranean coast, about 63 km (39 mi.) south of Tel Aviv and 16 km (10 mi.) north of Gaza (map reference 107.119). Astride fertile soil and fresh groundwater, Ashkelon is ideally suited for irrigation agriculture and maritime trade. The port was founded on an underground river, which about fifteen million years ago flowed above ground into a great salt lake. Later in prehistoric times, sands from what became the Nile Delta washed up and over the Coastal Plain of Canaan, forming at different times a series of north-south ridges of loosely cemented sandstone (the local bedrock known as kurkar). These sands buried the prehistoric river channel, which carries fresh water along its underground aquifer from the eastern foothills (Shephelah) to the beaches of Ashkelon. Dozens of wells tap the underground water source, some 20 m below the modern surface. The oldest well excavated at Ashkelon dates to about 1000 BCE. In the past, as today, these fresh waters transformed Ashkelon into a veritable oasis and garden spot.

An arc of earthworks, 2 km (1.2 mi.) long and in places 40 m high, encloses ancient settlements spanning six thousand years, from the Chalcolithic to the Mameluke periods. At times (Middle Bronze Age II, Iron Age I-II, and Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Arab periods), the cities were extremely large for the Levant - more than 150 a. in area, with perhaps as many as fifteen thousand inhabitants. Today, the ruined ramparts of Ashkelon enclose the Yigael Yadin National Park. William of Tyre provides this eyewitness account of the defenses of Ashkelon in the twelfth century CE.

[Ascalon] lies upon the seacoast in the form of a semicircle, the chord or diameter of which extends along the shore while the arc or bow lies on the land looking toward the east. The entire city rests in a basin, as it were, sloping to the sea and is surrounded on all sides by artificial mounds, upon which rise the walls with towers at frequent intervals. The whole is built of solid masonry, held together by cement which is harder than stone. The walls are wide, of goodly thickness and proportionate height. The city is furthermore encircled by outworks built with the same solidity and most carefully fortified. There are four gates in the circuit of the wall, strongly defended by lofty and massive towers. The first of these, facing east, is called the Greater Gate and sometimes the Gate of Jerusalem, because it faces toward the Holy City. It is surmounted by two very lofty towers which serve as a strong protection for the city below. In the barbican before this gate are three or four small gates which one passes to the main entrance by various winding ways. The second gate faces west. It is called the Sea Gate, because through it people have egress to the sea. The third to the south looks toward the city of Gaza ... , whence it takes its name. The fourth with outlook toward the north is called the Gate of Jaffa, from the neighbouring city which lies on this same coast.Ashkelon or, better, Ascalon (in the classical sources), lent its name to a special variety of onion (caepa Ascalonia) grown there and exported around the Mediterranean to many Roman cities (Strabo XVI, 2, 29; Pliny, NH XIX, 32, 101-107). Its name is still retained in a variety of onion known as scallion. 'Asqelon (with prosthetic aleph) apparently took its name from the old Northwest Semitic, probably Canaanite, word *tql, meaning "to weigh," from which the word shekel comes.

(William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, [tr. E. A. Babcock and A. C. Krey], New York 1943, pp. 17, 22)

This apt name for a commercial seaport, together with the names of three of its rulers, is already attested in both the earlier and later Egyptian Execration texts of the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries BCE. Ashkelon was a mighty city throughout the Middle Bronze Age II. It might have contributed to the Semitic takeover of Egypt during the Second Intermediate period (c. 1650-1550 BCE), when the Hyksos (or Canaanites) ruled Egypt. Like other cities in southern Canaan, Ashkelon suffered severe destruction in the aftermath of the "Hyksos expulsion."

During most of the Late Bronze Age, Ashkelon remained under Egyptian suzerainty. In the fourteenth century BCE, Yidya, ruler of Ashkelon, sent at least seven letters to the Egyptian court at el-Amarna (nos. 320-326, 370). He promised to provide bread, beer, oil, grain, and cattle for Pharaoh's troops. In another letter, Yidya is accused of provisioning Pharaoh's enemies, the 'Apiru (no. 287). In yet another, Yidya is asked to send glass ingots (ehlipakku) to Egypt. In the late thirteenth century BCE Ashkelon, Gezer, Yanoam, and the Israelites rebelled against Merneptah (recorded in the Israel Stela, c. 1207 BCE). A relief at Karnak, originally ascribed to Ramses II but recently attributed to his son Merneptah, depicts Egyptian troops assaulting Ashkelon (identified in the hieroglyphic legend), while Canaanites, inside the fortified city (or citadel) set on a hill (or tell), pray for mercy. The first Philistine inhabitants of Ashkelon did not arrive until about 1175 BCE, early in the reign of Ramses III.

The Onomasticon of Amenope (early eleventh century BCE) lists Ashkelon as a Philistine city, together with Gaza and Ashdod. Ashkelon is mentioned in the Bible as a member of the Philistine Pentapolis, or league of five cities, each ruled by a seren (Jos. 13:3; 1 Sam. 6:4, 6: 17). According to Deuteronomic tradition, Ashkelon was allotted to the tribe of Judah but not conquered (Septuagint, Jg. 1:18). During the period of the Judges, Samson's exploits took him to Gaza and Ashkelon. After the Philistines guessed his riddle, Samson paid off his bet by killing thirty men of Ashkelon, stripping them of their wardrobes and giving their clothes to the Philistines who answered the riddle.

The most famous biblical reference to Ashkelon is from David's elegy over the death of Saul and Jonathan, which begins: "Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets (Hebrew huzot) of Ashkelon; lest the daughters of the Philistines rejoice" (2 Sam. 1 :20). The Hebrew word commonly translated "streets" probably means "bazaars" or "marketplace," again alluding to the commercial prominence of the Philistines' major seaport.

After the Assyrian monarch Tiglath-Pileser III invaded Philistia in 734 BCE, Mitinti I, king of Ashkelon, acknowledged his suzerainty, but shortly thereafter he revolted. He was replaced by his son Rukibtu, who headed a pro-Assyrian regime. Ashkelon remained loyal to Assyria until late in the eighth century BCE, when Sidqa usurped the throne in Ashkelon and joined Hezekiah, king of Judah, in an alliance against Assyria. Together they deposed Padi, king of Ekron, who, like Mitinti of Ashdod and Sillibel of Gaza, had remained loyal to Assyria. In 701 BCE Sennacherib brought an end to the rebellion by restoring Padi to his throne. He deported Sidqa to Assyria and replaced him with Sharruludari, son of Rukibtu, who had earlier followed a pro-Assyrian policy. However, Ashkelon lost and never regained part of its kingdom, which at one time included Jaffa, Bene-Berak, Azor, and Beth-Dagon. This region (near modern Tel Aviv) was annexed to the Assyrian province in the north.

In the seventh century BCE Ashkelon was ruled by Mitinti II, son of Sidqa, a vassal of Esarhaddon and of Ashurbanipal. After the decline of the Assyrian empire in the West, first the Egyptians (in the time of Psamtik I) and then the Babylonians gained ascendancy. In 604 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Ashkelon and led Aga', the last king of Philistine Ashkelon, into exile in Babylon. The sons of Aga', sailors, and various nobles received rations from Nebuchadnezzar. Herodotus (I, 103-106) reports that Scythian soldiers sacked the temple of Aphrodite Ouriana (the Celestial Aphrodite) at Ashkelon, which was considered by the Greeks to be the "oldest temple consecrated to this deity." Because Scythians served in Nebuchadnezzar's army, it is possible that Herodotus singled out this episode to epitomize the general destruction of Ashkelon by the Babylonians in 604 BCE.

Mopsus, seer and hero of the Trojan War, reached Ashkelon and died here (according to the fifth-century BCE Lydian historian Xanthos). Under the Persians, Ashkelon became a "city of the Tyrians" and the headquarters of a Tyrian governor (Pseudo-Scylax, Periplus I, 78, late fourth century BCE). The Phoenicians curried favors from their Persian overlords by providing naval power and maritime wealth. Coastal cities as far south as Ashkelon grew rich from Phoenician commerce. In classical tradition, Ashkelon was known for its large lake, sacred to the goddess Derketo, or Atargatis (Diodorus Siculus II, 4, 2-6).

After the death of Alexander the Great, first the Ptolemies ruled Ashkelon and then the Seleucids (c. 198 BCE). The city retained its autonomy throughout the Hasmonean period, although Ashkelon was threatened but not destroyed (as Ashdod was) by Jonathan the high priest (1 Mace. 10:84- 87, 11 :60). During the Hellenistic period some Phoenicians from Ashkelon lived abroad in Greek cities, such as Piraeus and in Thessaly (third-century BCE inscriptions on marble stelae). The famous Letter of Aristeas (c. 150 BCE) mentions Ashkelon, Joppa (Jaffa), Gaza, and Ptolemais (Acco) as harbors for maritime trade.

During the first century BCE, Ashkelon minted its own silver shekels, which bore the dove, the symbol of Tyche-Astarte and symbol of the autonomous mint. The Greek inscription on the coins reads: "Of the people of Ascalon, holy, city of asylum, autonomous." Ashkelon had not only the most active mint in the country, it was also a banking center. A certain Philostratus from Ashkelon gained fame as a prominent banker. Antiochus of Ashkelon became head of the Academy in Athens, where he tried to reconcile the philosophies of Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. Dorotheus of Ashkelon compiled a lexicon of Attic Greek. According to Julius Africanus (cited in Eusebius, HE 1.6.2, 7.11), Herod the Great was born in Ashkelon and his grandfather had been a hierodule in the temple of Apollo here. When Herod became king, he bestowed great honors on his birthplace by building "baths and ornate fountains ... with colonnades (peristula) remarkable for their workmanship and size" (Josephus, War I, 21, 42). He also built a palace in Ashkelon for Emperor Augustus. When Herod died, Augustus bestowed it upon Herod's sister, Salome (Antiq. 17, 11, 5).

During the First Jewish Revolt, Ashkelon defended itself against attacks from the Jewish rebels. In the period of the Mishnah and Talmud (second-fifth centuries CE), Ashkelon was home to many Jews; however, the city had a reputation for being outside the halakhic borders of the "land of Israel." Talmudic sources refer to the market and gardens around Ashkelon. During the Roman period, both Ashkelon and Gaza were famous for their international trade fairs. Ashkelon was a center of exchange for the wheat trade. It also produced henna, dates, onions, and other garden crops for export. The Severan dynasty took an active interest in Ashkelon and reorganized the city according to Roman plan, while encouraging the survival (and revival) of Phoenician cults, such as that of Tanit (Phanebalos).

In the Byzantine period, Ashkelon flourished as a major center of export for wines from the Holy Land. It also became a port of call for Christian pilgrims. Here they could view wells believed to have been dug by the biblical patriarch Abraham (Origen, Contra Celsum, 4.44, and Eus., Onom. 168 = Puteus Pacis of Antoninus Martyr, c. 560 CE = Bir Ibrahim of lbn Battuta). By 536 CE Ashkelon was the seat of a bishop. Ashkelon surrendered to Caliph Omar in 636, but the Byzantines did not actually evacuate the city until 640. According to the Arab chroniclers, Ashkelon became a beautiful and delightful city once again.

The Fatimids dominated Ashkelon until 1153, then the Crusaders captured and held it until 1187, when, after his decisive victory at the Horns of Hattin, Saladin retook Ashkelon. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, led by Richard the Lion-Heart, the Crusaders once again conquered Ashkelon, but not before Saladin himself reduced the city and its harbor to rubble. Several Arab sources recount the agony of the self-destruction. The following year, Richard partially rebuilt Ashkelon and then, by mutual agreement with Saladin, dismantled it once more. In 1240 Richard, Duke of Cornwall, built a last redoubt. Thirty years later, the Mameluke sultan Baybars destroyed his castle.

In 1815, H. Stanhope led an expedition to Ashkelon in search of buried treasure. She uncovered a large peristyle basilica (?) (known only from David Robert's 1839 lithograph of Ashkelon), as well as a statue of a cuirassed soldier, probably a Roman emperor. On her orders the statue was smashed, but not before her personal physician made a sketch of it. A "twin" of the statue was recently discovered in Roman Beth-Shean. Both the statue and the basilica (?) probably belong to the Severan period.

The first scientific excavations were conducted in 1921-1922 by J. Garstang and his assistant, W. J. Phythian-Adams. Garstang discovered a large Roman building he thought was a combination bouleuterion and peristyle built by Herod the Great. However, this structure and its statuary also belong to the early third century CE reorganization of Ashkelon under the Severan dynasty. Phythian-Adams cut one step trench on the north side of the south mound (el-Khadra) in grid 38 of the Harvard University excavations, and another on the seaside between grids 50 and 57. He discovered Bronze and Iron Age Ashkelon and correctly identified aspects of Philistine culture in the stratified sections. From the 1930s to the present, various salvage operations were undertaken by the Mandatory and Israel Department of Antiquities. Their most noteworthy discoveries from the Roman-Byzantine period are a painted Roman tomb (excavated in 1937 by J. Ory), two basilican churches in Ashkelon-Barnea (one excavated by Ory in 1954 and the other by V. Tzaferis in 1966-1967), and two marble sarcophagi with sculptured reliefs found in 1972 in Ashkelon-Afridar. From earlier periods, a Neolithic site on the shore of Ashkelon was excavated by J. Perrot and J. Hevesy in 1955. The discovery of a major Early Bronze Age I settlement at Ashkelon-Afridar and the soundings there by R. Gophna (and B. Brandl) are extremely important. The Leon Levy Expedition has been conducting the first large-scale excavations at Tel Ashkelon since 1985. The excavations are sponsored by the Harvard Semitic Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and directed by L. E. Stager. The Leon Levy Expedition has recovered cultural sequences from the fourth millennium BCE through the thirteenth century CE. The results of these excavations constitute much of the following survey of Ashkelon.

The Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon has conducted excavations at Tel Ashkelon for 17 seasons, from 1985 to 2000 and another in 2004. The expedition is sponsored by the Semitic Museum of Harvard University and co-sponsored by Boston College. The Director of the Expedition is L. E. Stager. The excavated fields discussed here include grid 2 on the north, grid 50 on the seaside, and grid 38 in the center of the mound.

- Fig. 1 - Location Map

from Di Segni et al. (2022)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

General location map

(created by Itamar Ben-Ezra)

Di Segni et al. (2022) - Location Map of Ashkelon

from biblewalks.com

Ashkelon and the south west of Israel – during the Biblical periods

Ashkelon and the south west of Israel – during the Biblical periods

(based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Fig. 1a&b Location Map of Ashkelon

from Galili et al (2021)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Location map

- the eastern Mediterranean and the Israeli coast (E. Galili)

- Ashkelon coast, including the location of the cross-section a-a (see Fig. 2) (E. Galili)

Galili et al (2021)

- Fig. 1a&b Location Map of Ashkelon

from Galili et al (2021)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Location map

- the eastern Mediterranean and the Israeli coast (E. Galili)

- Ashkelon coast, including the location of the cross-section a-a (see Fig. 2) (E. Galili)

Galili et al (2021)

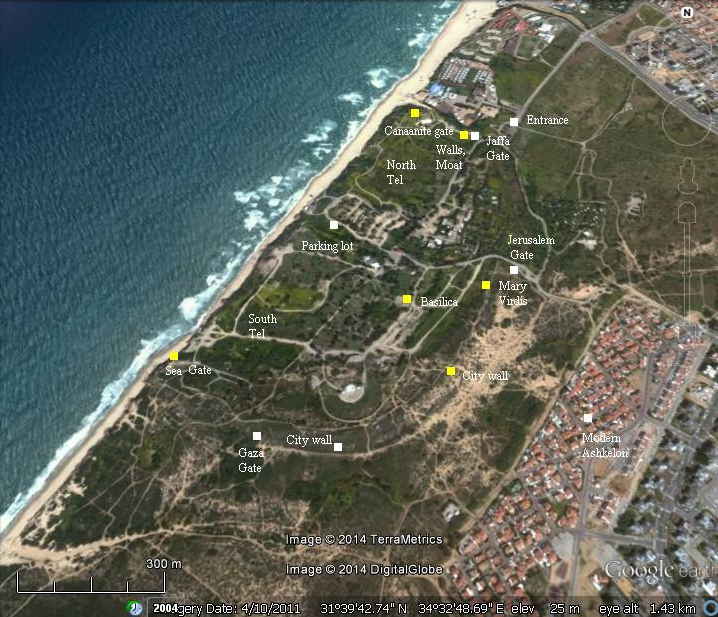

- Annotated Satellite Image (google) of

the Ashkelon environs from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of the Ashkelon environs

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of the Ashkelon environs

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Annotated Satellite Image (google) of

the Ancient Ashkelon from biblewalks.com

- Annotated Aerial View of Ashkelon

from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 1)

Aerial view of Ashkelon:

Aerial view of Ashkelon:

- Roman city

- The mound

- The harbor

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 1) - Fig. 1c Annotated Aerial View of Ashkelon

from Galili et al (2021)

Figure 1c

Figure 1c

Tel Ashkelon, the location of the two wooden installations (A, B), the location of the coastline during the Late Roman period (green line) and at present (thin red line)

(Modified by E. Galili after Google Earth: Image ©2018 TerraMetrics; © 2018 ORION-ME; © 2018 Google; Image © 2018 Digital Globe).

Galili et al (2021) - Ashkelon in Google Earth

- Ashkelon on govmap.gov.il

- Site Plan for Levy

expedition from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 1)

General plan

(numbers correspond to the quadrants excavated by the Levy expedition)

- Al. Iron I (Philistine) mud-brick tower

- A2. MB DC mud-brick tower

- B. Glacis

- C. Sanctuary of the Silver Calf (MB IIC)

- D. Northern fortification line of MB II, Iron, Hellenistic, Byzantine, and Islamic cities

- E. MB II gate(?)

- F. Medieval stone masonry glacis

- G. Jaffa Gate

- J. Santa Maria Viridis (Byzantine church)

- K. Barbican of Jerusalem Gate

- L. Fatimid houses (Grid 37)

- M. MB II-LB II, Iron I-II remains (Grid 38 Lower)

- N. Villas and Bathhouse (Grid 38 Upper)

- 0. Severen Forum (Garstang's Senate Hall and Peristyle)

- P. Medieval towers and fortification line

- Q. Maqam el-Khadra (Shrine of the Green Lady)

- R. Persian period warehouses and "Dog Cemetery"

- S. Persian period buildings and "Dog Cemetery"

- T. Byzantine church

- U. Site of ancient theater

- V. Sea Wall and Gate

- W. Gaza Gate

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 1) - Site Plan with excavation

areas of the Levy expedition from Stern et. al. (2008)

topographic map of the tell showing the location of excavation areas

topographic map of the tell showing the location of excavation areas

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Site Plan for Levy

expedition from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 1)

General plan

(numbers correspond to the quadrants excavated by the Levy expedition)

- Al. Iron I (Philistine) mud-brick tower

- A2. MB DC mud-brick tower

- B. Glacis

- C. Sanctuary of the Silver Calf (MB IIC)

- D. Northern fortification line of MB II, Iron, Hellenistic, Byzantine, and Islamic cities

- E. MB II gate(?)

- F. Medieval stone masonry glacis

- G. Jaffa Gate

- J. Santa Maria Viridis (Byzantine church)

- K. Barbican of Jerusalem Gate

- L. Fatimid houses (Grid 37)

- M. MB II-LB II, Iron I-II remains (Grid 38 Lower)

- N. Villas and Bathhouse (Grid 38 Upper)

- 0. Severen Forum (Garstang's Senate Hall and Peristyle)

- P. Medieval towers and fortification line

- Q. Maqam el-Khadra (Shrine of the Green Lady)

- R. Persian period warehouses and "Dog Cemetery"

- S. Persian period buildings and "Dog Cemetery"

- T. Byzantine church

- U. Site of ancient theater

- V. Sea Wall and Gate

- W. Gaza Gate

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 1) - Site Plan with excavation

areas of the Levy expedition from Stern et. al. (2008)

topographic map of the tell showing the location of excavation areas

topographic map of the tell showing the location of excavation areas

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Superimposed city gates 1-4

(Middle Bronze Age IIA–IIB) from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plans of superimposed city gates 1–4 (Middle Bronze Age IIA–IIB)

Block plans of superimposed city gates 1–4 (Middle Bronze Age IIA–IIB)

Stern et. al. (2008)

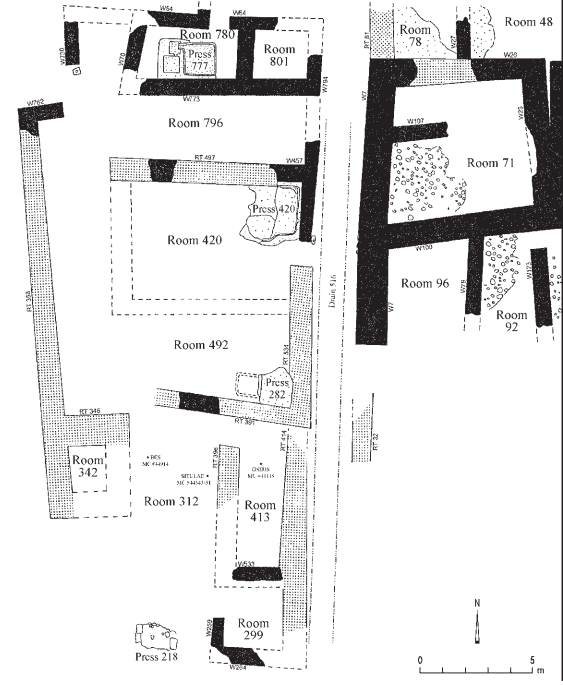

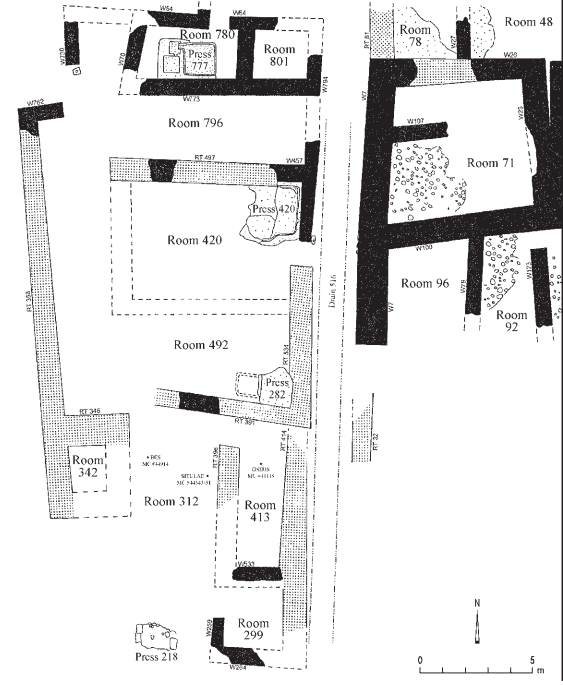

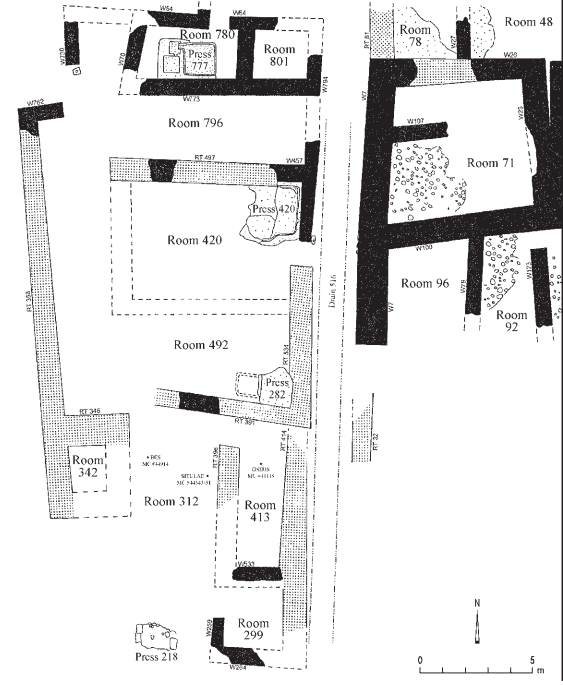

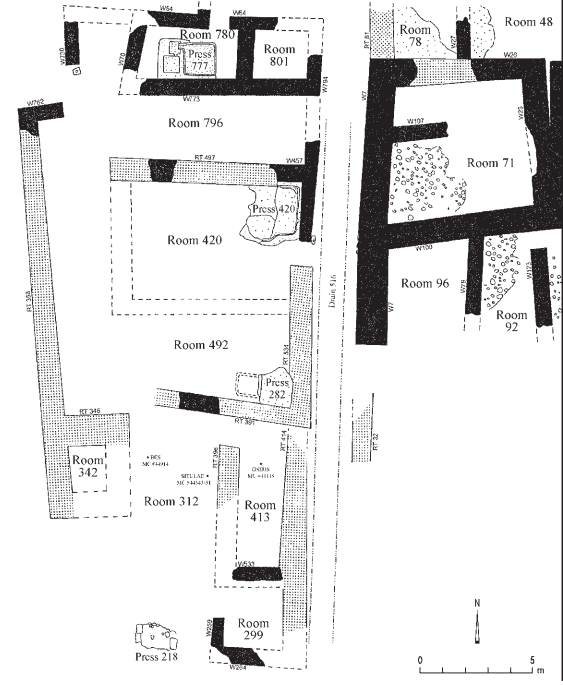

- Plan of Grid 38 Phase 14

(Royal Winery) from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plan of the royal winery (grid 38, phase 14)

Block plan of the royal winery (grid 38, phase 14)

Stern et. al. (2008) - Plan of Grid 38 Phase 19

from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plan of grid 38, phase 19

Block plan of grid 38, phase 19

Stern et. al. (2008) - Plan of Grid 38 Phase 20A

from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plan of grid 38, phase 20A

Block plan of grid 38, phase 20A

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Plan of Grid 38 Phase 14

(Royal Winery) from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plan of the royal winery (grid 38, phase 14)

Block plan of the royal winery (grid 38, phase 14)

Stern et. al. (2008) - Plan of Grid 38 Phase 19

from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plan of grid 38, phase 19

Block plan of grid 38, phase 19

Stern et. al. (2008) - Plan of Grid 38 Phase 20A

from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plan of grid 38, phase 20A

Block plan of grid 38, phase 20A

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Plan of Grid 50 Phase 7

(Marketplace) from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plan of the marketplace (grid 50, phase 7).

Block plan of the marketplace (grid 50, phase 7).

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Plan of Grid 50 Phase 7

(Marketplace) from Stern et. al. (2008)

Block plan of the marketplace (grid 50, phase 7).

Block plan of the marketplace (grid 50, phase 7).

Stern et. al. (2008)

- Section of northern rampart

from Stern et. al. (1993 v. 1)

Schematic section of northern rampart, looking west

Schematic section of northern rampart, looking west

Stern et. al. (1993 v. 1) - Fig. 2 Reconstructed cross-section

of Tel Ashkelon coast during the Late Roman-Byzantine periods from Galili et al (2021)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Schematic possible reconstruction of the cross-section of Tel Ashkelon coast during the Late Roman-Byzantine periods (for the location of the section, see line a-a in Fig.1b)

- ancient seawall with granite columns in secondary use

- remnants of the seawall and ancient settlement that collapsed into the sea, and stone weights (depth 0-1 m)

- ancient coastline

- remnants of wrecked watercraft (depth 2.5-4.5 m)

- ancient level of sand

- offshore anchor hold on a submerged kurkar ridge

(after Galili et al., 2001)

Galili et al (2021)

- Lithograph of the Ruins of

Ashkelon (ca. 1843) from Wikipedia

- Fig. 1 Aerial View of the Ruins of

Ashkelon with location of outcrop with potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

landsat image showing location of profile section as red dot. Layout of archaeological site modified after Stager and Schloen (2008)

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 2 Photo of outcrop with

potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

- A Photograph of the coastal profile at the archaeological site of Ashkelon. The square ‘B’ marks the location of the sampled section.

- Sampled section with locations of specific finds.

- Yellow circles mark pottery sherds (see Fig. 4 for pottery detail)

- Blue circles mark locations of rip-up clasts. For details on rip-up clasts see also Fig. 6.

- Pink circle marks fishbone find (see Fig. 3B).

- Red triangles mark locations of C14 dated samples.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 3 Closeup photos of outcrop

with potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Close up photographs of significant features of the sequence (for location see Fig. 2B)

- Details of profile B-B′. Red triangle marks location of C14 sample

- Fishbone extracted from upper portion of the outcrop

- Example of imbricated shells from layer at approximately 70 cm at A-A’

- in situ photograph of 4–5th c. BC pottery overlying the mud layer also displayed in Fig. 2B

Vertical scale reference is also shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 4

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 4 Analytical results of

different proxies obtained from profiles A-A’ and B-B′ from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Analytical results of different proxies obtained from profiles A-A’ and B-B′. Red triangles mark calibrated C14 ages.

- Particle size distribution contour maps were plotted with Ocean Data View software, version 4.6.3.1, (Schlitzer, 2014) and show % volumetric representation per size (“μm”) by color, with maximum proportion shown 8%, with color range from lavender (‘0’) to yellow (‘ >8%’)

- Proportions of fossil foraminifera, Orbulina universa, individuals > 500 μm and yellowing in %

- ratio of fossil/non fossil assemblage

- sums of non-fossil, fossil and all foraminifera picked normalized to a 1 cm3 sample.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 5 Comparison of assemblage

of fossil foraminifera tests (%) from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Comparison of assemblage of fossil foraminifera tests (%) compared from a composite of A and B section and two surface samples collected offshore from 20 and 12 m water depths.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 6 Photographs of pottery

found within the section from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Photographs of pottery found within the section. See Fig. 2B for reference to position. It is a rim of a Phoenician storage jar dated to the 4–5th century BC

(comparative drawing from Zemer 1978 pl. 7:21).

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 7 Photograph of rip-up clast

found within the section from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

- Photograph of rip-up clast in original context (location shown in Fig. 2B)

- photograph of background sediments that surrounded the rip-up clast

- photograph of sediment composition of rip-up clast

- grain size distribution of rip-up clast sediments compared to background sediment

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 8 Stitched photo showing

lateral extent of tsunami deposit from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Stitched high resolution photograph of section following storm-induced cliff collapse in December 2010 (Moshier et al.,2011). Blue Highlighted area shows lateral extent of the proposed tsunami deposit.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 9 Particle size distribution

of pre- and post- storm deposits from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Particle size distribution of pre- and post- storm deposits of the major storm event in December 2010. Contour maps were plotted with Ocean Data View software (version 4.6.3.1; Schlitzer, 2014).

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 10 Reconstructed location

of coastline for the 4–5th century BCE coastline for the 4–5th century BCE from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Reconstructed location of coastline for the 4–5th century BCE according to an average coastline retreat of ca. 0.20 cm/a (after Barkai et al., 2017). Layout of archaeological site modified after Stager and Schloen, 2008 (p. 154 Fig. 9.1). Original photomosaic from Moshier et al. (2011).

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 11 Comparison of tsunamigenic

sediments in Ashkelon with those reported after the 2001 Peruvian tsunami event from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Comparison of tsunamigenic sediments reported after the 2001 Peruvian tsunami event

- sequence photograph and interpretation modified after Jaffe et al. (2003)

- Ashkelon sequence photograph and interpretation

Hoffmann et al. (2017)

- Fig. 2 Photo of outcrop with

potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

- A Photograph of the coastal profile at the archaeological site of Ashkelon. The square ‘B’ marks the location of the sampled section.

- Sampled section with locations of specific finds.

- Yellow circles mark pottery sherds (see Fig. 4 for pottery detail)

- Blue circles mark locations of rip-up clasts. For details on rip-up clasts see also Fig. 6.

- Pink circle marks fishbone find (see Fig. 3B).

- Red triangles mark locations of C14 dated samples.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 3 Closeup photos of outcrop

with potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Close up photographs of significant features of the sequence (for location see Fig. 2B)

- Details of profile B-B′. Red triangle marks location of C14 sample

- Fishbone extracted from upper portion of the outcrop

- Example of imbricated shells from layer at approximately 70 cm at A-A’

- in situ photograph of 4–5th c. BC pottery overlying the mud layer also displayed in Fig. 2B

Vertical scale reference is also shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 4

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 11 Comparison of

tsunamigenic sediments in Ashkelon with those reported after the 2001 Peruvian tsunami event from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Comparison of tsunamigenic sediments reported after the 2001 Peruvian tsunami event

- sequence photograph and interpretation modified after Jaffe et al. (2003)

- Ashkelon sequence photograph and interpretation

Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Hoffmann et al. (2017:2) note that

Ashkelon is associated with events that occurred in 1032, 1068, 1546, and possibly 1759 CE (Maramai et al., 2014). Past studies suggested that there were coastal tsunami deposits from the Bronze Age eruption of Santorini, though the deposits were never dated or analyzed in detail (Pfannenstiel, 1960).Likely causes of the tsunamis in this region are landslides and sub-marine slumping triggered by near and far field earthquakes and volcanic eruptions; such as those originating in the Cypriot and Aegean arcs (e.g. (Fokaefs and Papadopoulos, 2007; Katz et al., 2015a, 2015b; Salamon et al., 2007; Yolsal et al., 2007).Goodman-Tchernov and Austin (2015) and Tyulneva et al (2017) appear to have identified tsunamigenic sediments due to the Bronze Age eruption of Santorini in cores taken offshore of Caesarea and Jisr az-Zarka, respectively. The events of

1032, 1068, 1546, and possibly 1759 CEcorrespond to earthquakes listed in this catalog. They are linked to and briefly discussed below:

- 1032 - The 11th century Palestine Quake struck on 5 Dec. 1033 CE and may have been succeeded by another earthquake around 17 or 18 February 1034 CE. These events did not occur in 1032 CE. Yahya of Antioch, Bar Hebraeus, and an unpublished greek manuscript in Analecta ierosolymitikis stachiologias described a tsunami in Akko which would have presumably struck on 5 December 1033 CE. Michael Bishop of Tannis, an approximately contemporaneous source, also wrote about a tsunami associated with this earthquake but did not specify a location. Tannis, which no longer exists, was located on the eastern end of the Nile Delta close to the modern Mediterranean port town of Port Said.

- 1068 - A number of sources (al-Banna, Mawhub ibn Mansur Mufarrij, Ibn al-Athir, Sibt Ibn al-Jawzi, al-Dhahabi, as-Suyuti, an Ibn al-Imad) report a tsunami from one of the 1068 CE Quake(s) but did not specify a location. Although, some scientific papers have located this tsunami on the Mediterranean coast, there is no historical justification for this. Al-Banna and Sibt Ibn al-Jawzi reported that the entire town of Ayla was destroyed except for 12 people who were fishing at the time of the earthquake indicating that the tsunami reports may have originated from Ayla (i.e. the survivors were far enough out to sea to not have been affected by the tsunami surge). As there were many reports of damage in the Hejaz, an epicenter in the Gulf of Aqaba is a strong possibility - which is yet another reason why this tsunami is more likely to have struck Ayla rather than Ashkelon.

- 1546 - An Anonymous Venetian and the News of '46' reported a tsunami in Jaffa during the 1546 CE Earthquake.

- possibly 1759 CE - The epicenters for the 1759 CE Baalbek and Safed Quakes were well north of Ashkelon.

Marco et al (2014:1457), while citing Ambraseys and Barzanagi (1989),

described "boats that were swept ashore from the Akko harbor and a large wave that was reported from as far south as the Nile Delta".

Ambraseys (2009) reports that during the 30 Oct. 1759 CE Safed Quake,

a seismic sea wave flooded Acre to a height of about 2.5 m above normal sea level, as well as the docks of Tripoli, without causing any damage

. Both Ambraseys (2009) and Ambraseys and Barzanagi (1989) list a multitude of sources for these earthquakes and I have not yet encountered the sources which described a tsunami in Akko (or elsewhere). Marco et al (2014) described flame structures in a section at the Taninim Creek Dam which they attributed to a tsunami. Unfortunately, the date for the formation of these flame structures is not well constrained. They likely formed between ~1500 and ~1900 CE.

- Fig. 1 Aerial View of the Ruins of

Ashkelon with location of outcrop with potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

landsat image showing location of profile section as red dot. Layout of archaeological site modified after Stager and Schloen (2008)

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 2 Photo of outcrop with

potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

- A Photograph of the coastal profile at the archaeological site of Ashkelon. The square ‘B’ marks the location of the sampled section.

- Sampled section with locations of specific finds.

- Yellow circles mark pottery sherds (see Fig. 4 for pottery detail)

- Blue circles mark locations of rip-up clasts. For details on rip-up clasts see also Fig. 6.

- Pink circle marks fishbone find (see Fig. 3B).

- Red triangles mark locations of C14 dated samples.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 3 Closeup photos of outcrop

with potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Close up photographs of significant features of the sequence (for location see Fig. 2B)

- Details of profile B-B′. Red triangle marks location of C14 sample

- Fishbone extracted from upper portion of the outcrop

- Example of imbricated shells from layer at approximately 70 cm at A-A’

- in situ photograph of 4–5th c. BC pottery overlying the mud layer also displayed in Fig. 2B

Vertical scale reference is also shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 4

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 4 Analytical results of

different proxies obtained from profiles A-A’ and B-B′ from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Analytical results of different proxies obtained from profiles A-A’ and B-B′. Red triangles mark calibrated C14 ages.

- Particle size distribution contour maps were plotted with Ocean Data View software, version 4.6.3.1, (Schlitzer, 2014) and show % volumetric representation per size (“μm”) by color, with maximum proportion shown 8%, with color range from lavender (‘0’) to yellow (‘ >8%’)

- Proportions of fossil foraminifera, Orbulina universa, individuals > 500 μm and yellowing in %

- ratio of fossil/non fossil assemblage

- sums of non-fossil, fossil and all foraminifera picked normalized to a 1 cm3 sample.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 5 Comparison of assemblage

of fossil foraminifera tests (%) from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Comparison of assemblage of fossil foraminifera tests (%) compared from a composite of A and B section and two surface samples collected offshore from 20 and 12 m water depths.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 6 Photographs of pottery

found within the section from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Photographs of pottery found within the section. See Fig. 2B for reference to position. It is a rim of a Phoenician storage jar dated to the 4–5th century BC

(comparative drawing from Zemer 1978 pl. 7:21).

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 7 Photograph of rip-up clast

found within the section from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

- Photograph of rip-up clast in original context (location shown in Fig. 2B)

- photograph of background sediments that surrounded the rip-up clast

- photograph of sediment composition of rip-up clast

- grain size distribution of rip-up clast sediments compared to background sediment

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 8 Stitched photo showing

lateral extent of tsunami deposit from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Stitched high resolution photograph of section following storm-induced cliff collapse in December 2010 (Moshier et al.,2011). Blue Highlighted area shows lateral extent of the proposed tsunami deposit.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 9 Particle size distribution

of pre- and post- storm deposits from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Particle size distribution of pre- and post- storm deposits of the major storm event in December 2010. Contour maps were plotted with Ocean Data View software (version 4.6.3.1; Schlitzer, 2014).

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 10 Reconstructed location

of coastline for the 4–5th century BCE coastline for the 4–5th century BCE from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Reconstructed location of coastline for the 4–5th century BCE according to an average coastline retreat of ca. 0.20 cm/a (after Barkai et al., 2017). Layout of archaeological site modified after Stager and Schloen, 2008 (p. 154 Fig. 9.1). Original photomosaic from Moshier et al. (2011).

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 11 Comparison of tsunamigenic

sediments in Ashkelon with those reported after the 2001 Peruvian tsunami event from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Comparison of tsunamigenic sediments reported after the 2001 Peruvian tsunami event

- sequence photograph and interpretation modified after Jaffe et al. (2003)

- Ashkelon sequence photograph and interpretation

Hoffmann et al. (2017)

- Fig. 2 Photo of outcrop with

potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

- A Photograph of the coastal profile at the archaeological site of Ashkelon. The square ‘B’ marks the location of the sampled section.

- Sampled section with locations of specific finds.

- Yellow circles mark pottery sherds (see Fig. 4 for pottery detail)

- Blue circles mark locations of rip-up clasts. For details on rip-up clasts see also Fig. 6.

- Pink circle marks fishbone find (see Fig. 3B).

- Red triangles mark locations of C14 dated samples.

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 3 Closeup photos of outcrop

with potential tsunamigenic evidence from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Close up photographs of significant features of the sequence (for location see Fig. 2B)

- Details of profile B-B′. Red triangle marks location of C14 sample

- Fishbone extracted from upper portion of the outcrop

- Example of imbricated shells from layer at approximately 70 cm at A-A’

- in situ photograph of 4–5th c. BC pottery overlying the mud layer also displayed in Fig. 2B

Vertical scale reference is also shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 4

Hoffmann et al. (2017) - Fig. 11 Comparison of

tsunamigenic sediments in Ashkelon with those reported after the 2001 Peruvian tsunami event from Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Comparison of tsunamigenic sediments reported after the 2001 Peruvian tsunami event

- sequence photograph and interpretation modified after Jaffe et al. (2003)

- Ashkelon sequence photograph and interpretation

Hoffmann et al. (2017)

Hoffmann et al. (2017) identified a possible tsunamigenic deposit in a sea-cliff outcrop near the

southern extent of ancient Ashkelon. The deposit was dated to between 290 and 500 BCE based on archaeological stratigraphic succession and a few sherds of pottery. Two radiocarbon samples gave older and divergent ages

which were not deemed to be diagnostic of the true age of deposition. The ages from these radiocarbon samples conflicted with a stratigraphic succession which showed that the sediment body was deposited during the Persian period.

The older divergent radiocarbon dates were interpreted as indicating possible mixing or re-working of source materials which can be diagnostic of tsunamigenic deposits.

Hoffmann et al. (2017:9) noted that

signs that the deposit is of tsunamigenic origin include rip-up clasts, fining-up sequences, planktic foraminifera1 with signs of corrasion, imbricated clasts, and C14 ages older than the deposit itself (suggesting mixing)

.

In addition, the site's

location seems too far from rivers capable of delivering flash flood deposits (> 6 km. away) and estimates of coastal retreat suggest

that the deposit was far enough inland from the then coastline that a storm surge was less probable explanation. Although Hoffmann et al. (2017:9)

opined that other transport mechanisms that may have created a similar sediment signature, such as storms or floods are less-probable for this specific site

they could not

be entirely excluded

.

1 Deeper water planktic foraminifera would be less likely for storm surge

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tsunami? | sea-cliff outcrop near the southern extent of ancient Ashkelon

Fig. 1

Fig. 1landsat image showing location of profile section as red dot. Layout of archaeological site modified after Stager and Schloen (2008) Hoffmann et al. (2017) |

|

Hoffmann et al. (2017) identified a possible

tsunamigenic deposit in a sea-cliff outcrop near the southern extent of

ancient Ashkelon. The deposit was dated to between 290 and 500 BCE

based on archaeological stratigraphic succession and a few sherds of

pottery. Two radiocarbon samples gave older and divergent ages which

were not deemed to be diagnostic of the true age of deposition. The

ages from these radiocarbon samples conflicted with a stratigraphic

succession which showed that the sediment body was deposited during

the Persian period. The older divergent radiocarbon dates were

interpreted as indicating possible mixing or re-working of source

materials which can be diagnostic of tsunamigenic deposits.

Hoffmann et al. (2017:9) noted that signs that the deposit is of tsunamigenic origin include rip-up clasts, fining-up sequences, corrasion, imbricated clasts, and planktic foraminifera with signs of corrasion, and 14C ages older than the deposit itself (suggesting mixing). In addition, the site's location seems too far from rivers capable of delivering flash flood deposits (> 6 km. away) and estimates of coastal retreat suggest that the deposit was far enough inland from the then coastline that a storm surge was a less probable explanation. Although Hoffmann et al. (2017:9) opined that other transport mechanisms that may have created a similar sediment signature, such as storms or floods are less-probable for this specific sitethey could not be entirely excluded. |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image (s) | Comments | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsunami? | sea-cliff outcrop near the southern extent of ancient Ashkelon

Fig. 1

Fig. 1landsat image showing location of profile section as red dot. Layout of archaeological site modified after Stager and Schloen (2008) Hoffmann et al. (2017) |

|

Hoffmann et al. (2017) identified a possible

tsunamigenic deposit in a sea-cliff outcrop near the southern extent of

ancient Ashkelon. The deposit was dated to between 290 and 500 BCE

based on archaeological stratigraphic succession and a few sherds of

pottery. Two radiocarbon samples gave older and divergent ages which

were not deemed to be diagnostic of the true age of deposition. The

ages from these radiocarbon samples conflicted with a stratigraphic

succession which showed that the sediment body was deposited during

the Persian period. The older divergent radiocarbon dates were

interpreted as indicating possible mixing or re-working of source

materials which can be diagnostic of tsunamigenic deposits.

Hoffmann et al. (2017:9) noted that signs that the deposit is of tsunamigenic origin include rip-up clasts, fining-up sequences, corrasion, imbricated clasts, and planktic foraminifera with signs of corrasion, and 14C ages older than the deposit itself (suggesting mixing). In addition, the site's location seems too far from rivers capable of delivering flash flood deposits (> 6 km. away) and estimates of coastal retreat suggest that the deposit was far enough inland from the then coastline that a storm surge was a less probable explanation. Although Hoffmann et al. (2017:9) opined that other transport mechanisms that may have created a similar sediment signature, such as storms or floods are less-probable for this specific sitethey could not be entirely excluded. |

IX? |

Ambraseys, N. N. and M. Barazangi (1989). "The 1759 Earthquake in the Bekaa Valley: Implications for earthquake hazard assessment in the Eastern Mediterranean Region."

Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 94(B4): 4007-4013.

Ambraseys, N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press.

Brainerd, G.W., 1951. The place of chronological ordering in archaeological analysis.

Am. Antiq. 16, 301–313. - JSTOR

Galili, Ehud, Rosen, Baruch, Oron, Asaf, and Boaretto, Elisabetta (2021) The First Marine Structures Reported from Roman/Byzantine Ashkelon, Israel Do they solve the enigma of the city’s harbour?

in UNDER THE MEDITERRANEAN I Studies in Marine archaeology ed. STELLA DEMESTICHA & LUCY BLUE

Goodman-Tchernov, B. N., et al. (2009). "Tsunami waves generated by the Santorini eruption reached Eastern Mediterranean shores." Geology 37(10): 943-946.

Goodman-Tchernov, B. N. and J. A. Austin Jr (2015). "Deterioration of Israel's Caesarea Maritima's ancient harbor

linked to repeated tsunami events identified in geophysical mapping of offshore stratigraphy." Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 3: 444-454.

Hoffmann, N., et al. (2017). "Possible tsunami inundation identified amongst 4–5th century BCE archaeological deposits at Tel Ashkelon, Israel."

Marine Geology 396.

Israel, Yigal and Erickson-Gini, Tali (2013) Remains from the Hellenistic through the Byzantine Periods at the ‘Third Mile Estate’, Ashqelon

Atiqot 74

Maramai, A., Brizuela, B., Graziani, L., 2014. The Euro-Mediterranean tsunami catalogue.

Ann. Geophys. 57, S0435.

Marco, S., Katz, O., Dray, Y., 2014. Historical sand injections on the Mediterranean shore

of Israel: evidence for liquefaction hazard. Nat. Hazards 1449–1459.

Oked, H. S., et al. (2001). Ashkelon: a City on the Seashore.

ששון אבי ספראי זאב בן שמואל שגיב נחום & המכללה האקדמית (אשקלון). (2001). אשקלון - עיר לחוף ימים. המכללה האקדמית אשקלון.

Pfannenstiel, M., 1960. Erläuterungen zu den bathymetrischen Karten des östlichen Mittelmeeres.

Institut océanographique. Monaco

Rosen, A., 2008. Site formation. In: Stager, L., Schloen, D.J., Master, D. (Eds.), Ashkelon

1: Introduction and Overview. Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, Indiana, pp. 101–104. -

While discussing the 290-500 BCE tsunami (?) deposit, Hoffmann et al. (2017:7)

stated that these deposits were described previously and attributed to a single

catastrophic flood at Ashkelon (Rosen, 2008).

However, no source for a flood could be provided, and the author clearly stated that the interpretation was uncertain

.

Ashkelon 1: Introduction and Overview (1985-2006)

Ashkelon 2: Imported Pottery of the Roman and Late Roman Periods

Ashkelon 3: The Seventh Century B.C.

Ashkelon 4: The Iron Age Figurines of Ashkelon and Philistia

Ashkelon 5: The Land behind Ashkelon

Ashkelon 6: The Middle Bronze Age

Ashkelon 7: The Iron Age I

Ashkelon 8: The Islamic and Crusader Periods

Ashkelon 9: forthcoming

- from the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon

WC Adelman, Charles M. “Greek Pottery from Ashkelon, Israel: Hints of Presence?” American Journal of Archaeology 99/2 (1995): 305.

WC Allen, Mitchell. “Ashqelon, Regional Survey.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 113 (2001): 110*-111*.

WC Ashkelon: A City on the Seashore (Book of Ashkelon 1; Eretz: Geographic Research and Publications; eds. A. Sasson et al.), Ashkelon 2001 (Eng. abstracts).

WC Ashkelon, Bride of the South: Studies in the History of Ashkelon from the Middle Ages to the End of the 20th Century (Book of Ashkelon 2; Eretz: Geographic Research and Publications; eds. A. Sasson et al.), Ashkelon 2002 (Eng. abstracts).

WC Barkay, Rachel. “The Marisa Hoard of Selucid Tetradrachms Minted in Ascalon.” Israel Numismatic Journal 12 (1992-1993): 21-26.

DL Baker, Jill L. “Mortuary and Funerary Customs of the Middle Bronze IIB-C and Late Bronze Age Palestine.” ASOR Newsletter 54/3 (2004): 14-15.

G Barko, Tristan and Assaf Yasur-Landau. “One if by Sea…Two if by Land: How did the Philistines Get to Canaan?.” Biblical Archaeology Review 29/2 (2003): 24-39, 64, 66-67.

GS Barko, Tristan. “The Philistine Settlement as Mercantile Phenomenon?.” American Journal of Archaeology 104/3 (2000): 513-530.

WC Baumgarten, Ya’aqov. “Ashqelon, Hatayyasim Street.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 15 (1996): 99-100.

WC Berman Ariel and Leticia Barda. Map of Nizzanim-West (87); Map of Nizzanim-East (88). Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2005.

WC Bietak, Manfred. “Temple or ‘Bet Marzeah’?.” Symbiosis, Symbolism, and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel, and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age through Roman Palaestina- Proceedings of the Centennial Symposium, W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research and American Schools of Oriental Research, Jerusalem, May 29/31, 2000. Winona Lake, IN: 2003. 155-168.

WC Bietak, Manfred and Karin Kopetzky. The synchronisation of civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the second millennium B.C. : proceedings of an international symposium at Schloss Haindorf, 15th-17th of November 1996 and at the Austrian Academy, Vienna, 11th-12th of May 1998. Wien 2000, 99.

Bietak, M., Kopetzky, K. and L. E. Stager, "Stratigraphie Comparée Nouvelle: The Synchronisation of Ashkelon and Tell el-Dab´a." In Proceedings of the 3ICAANE in Paris, 2002. Ed. J.-C. Margueron, P. de Miroschedji and J.-P. Thalmann. (in press).

G Bijovsky, Gabriela. “Coins from Ashqelon, Semadar Hotel.” ‘Atiqot 48 (2004): 111-121.

WC Borowski, Oded. “Animals in the Religions of Syria-Palestine.” In: A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East (Handbook of Oriental Studies 1: The Near and Middle East 64; Handbuch der Orientalistic 64; ed. B. J. Collins). Leiden 2002. 405-424.

WC Brandl, Baruch. and Ram Gophna. “Ashkelon, Afridar.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 12 (1993): 89.

WC Braun, Eliot L. “Area G at Afridar, Palmahim Quarry 3 and the Earliest Pottery of Early Bronze Age I: Part of the ‘Missing Link’.” Ceramics and Change in the Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant, eds. Graham Philip and Douglas Baird. Sheffield 2000, 113-128.

WC Braun, Eliot L. and Ram Gophna, “Ashqelon, Afridar,” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 15 (1996), 97-99.

Brody, Aaron. ASOR Newsletter. 46/2 (1996).

WC Carmi, I., et al. "The Dating of Ancient Water Wells by Archaeological and 14C Methods: Comparative Study of Ceramics and Wood." Israel Exploration Journal 44 (1994): 184-200.

WC Cohen, Susan. Canaanites, Chronology, and Connections: The Relationship of Middle Bronze Age IIA Canaan to Middle Kingdom Egypt. Harvard Semitic Museum Publications, Studies in the History and Archaeology of the Levant, vol. 3, Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002.

GS Cohen-Weinberger, Anat and Y. Goren. “Levantine-Egyptian Interactions during the 12th to the 15th Dynasties based on the Petrography of the Canaanite Pottery from Tell el-Dabca.” Agypten und Levante 14 (2004): 69-100.

G Cross, Frank M. "A Philistine Ostracon From Ashkelon." Biblical Archaeology Review 22/1 (1996): 64-65.

WC Di Segni, Leah. “Two Greek Inscriptions from the Painted Tomb at Migdal Ashqelon.” ‘Atiqot 37 (1999): 83*-88*.

WC Dothan, Trude. “The Aegean and the Orient: Cultic Interactions.” Symbiosis, Symbolism, and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel, and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age through Roman Palaestina- Proceedings of the Centennial Symposium, W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research and American Schools of Oriental Research, Jerusalem, May 29/31, 2000. Winona Lake, IN: 2003. 189-213.

WC Eck, Werner and B. Zissu. "A Nauclerus de oeco poreuticorum in a New Inscription from Ashkelon/Ascalon." Scripta Classica Israelica.20 (2001). 89-96.

WC Ehrlich, Carl S. The Philistines in Transition: A History from ca 1000-730 B.C.E. (Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East 10). Leiden 1996.

WC Ein Gedy, Miki. “Ashqelon, El-Jura, A-3140.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 114 (2002): 90*.

WC Esse, Douglas. "Ashkelon." Anchor Bible Dictionary. Ed. D. N. Freedman, vol. 1, 477-490. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1992.

WC Fabian, P., et al. “Ashqelon, Hammama.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 14 (1994): 110-111.

WC Fabian, Peter and Y. Goren. “A Byzantine Storehouse and Anchorage South of Ashkelon.” ‘Atiqot 42 (2001): 211-219.

GS Faerman, M., et al. "Determining the sex of infanticide victims from the Late Roman era through ancient DNA analysis." Journal of Archaeological Science 25 (1998): 861-865.

GS —. "DNA analysis reveals the sex of infanticide victims." Nature 385 (1997): 212-213.

GS Fantalkin, Alexander. “Mezad Hashavyahu: Its Material Culture and Historical Background.” Tel Aviv 28/1 (2001): 131-136.

GS Faust, Avraham and Ehud Weiss. "Judah, Philistia and the Mediterranean World: Reconstructing the Seventh Century BCE Economic System.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 338, (2005): 71-92.

WC Finkielsztejn, Gerald. "Phanebal, de esse d'Ascalon." In: Numismatique et historique economique pheniciennes et puniques: actes du colloque, 1987 (Numismatica Lovaniensia 9; Studia Phoenicia 9): Leuven 1992, 51-58.

WC Fischer, Moche L. “The Basilica of Ascalon: Marble, Imperial Art and Architecture in Roman Palestine.” Contributors, Antje Krug and Z. Pearl. In: The Roman and Byzantine Near East: Some Recent Archaeological Research (JRA Supplementary Series 14). Ann Arbor, MI: 1995, 121-135.

WC ---. Marble Studies: Roman Palestine and the Marble Trade. (Xenia. Konstanzer Althistorische Vorträge und Forschungen No. 40) Konstanz: Konstanzer Universitätsverlag, 1998.

G Fuks, Gideon. “A Mediterranean Pantheon: Cults and Deities in Hellenistic and Roman Ashkelon.” Mediterranean Historical Review 15/2 (2000): 27-48.

WC Fuks, Gideon. “Antagonistic Neighbours: Ashkelon, Judaea, and the Jews.” Journal of Jewish Studies 51 (2000): 42-62.

WC Galili, Ehud and Y. Sharvit. “Ashqelon, North, Underwater and Coastal Survey.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 18 (1998): 101-102.

WC Garfinkel, Yossi. “Ashqelon, Afridar.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 110 (1999): 71*-72*.

G ---. “Radiometric Dates from Eight Millennium B.P. Israel.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 315 (1999): 1-13.

WC Geiger, Joseph. “Euenus of Ascalon.” Scripta Classica Israelica. 11(1991-1992): 114-122.

GS Geiger, Joseph. “Julian of Ascalon.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 112 (1992): 31-43.

WC Gersht, Rivka. “’Imperial’, ‘Local’, and ‘Provincial”—Their Definitions and Reflections in Roman Sculptures Uncovered in Eretz-Israel.” Michmanim 16 (2002): 43*-44*.

WC Gershuny, Lilly. “A Middle Bronze Age Cemetery in Ashqelon.” The Middle Bronze Age in the Levant: Proceedings of an International Conference on MB IIA Ceramic Material, Vienna, 24th-26th of January 2001. Wien 2002, 185-188.

G Gitler, Haim and Daniel M. Master. "Cleopatra at Ascalon: Recent Finds from the Leon Levy Expedition." Israel Numismatic Research 5 (2010): 67-98.

WC Gitler, Haim and Y. Kahanov. "The Ascalon 1988 Hoard (CH.9.548), A Periplus to Ascalon in the Late Hellenistic Period?" In Coin Hoards 9: Greek Hoards. Royal Numismatic Society Special Publications No. 35. Ed. A. Meadows, U. Wartenberg, 259Ð268. London: Royal Numismatic Society, 2002.

GS Gitler, Haim. "Achaemenid Motifs in the Coinage of Ashdod, Ascalon and Gaza from the Fourth Century B.C." Transeuphratène 20 (2000): 73-87.

WC —. "New Fourth-Century B.C. Coins from Ashkelon." The Numismatic Chronicle 156 (1996): 1-9.

G Godfrey-Smith, Dorothy and S. Shalev, “Determination of Usage and Absolute Chronology of a Pit Feature at the Ashkelon Marina, Israel.” Geochronometria 21 (2003): 163-166.

WC Golani, Amir. “A Persian Period Cist Tomb on the Ashqelon Coast.” ‘Atiqot 30 (1996): 115-119.

GS ---. “Ashkelon Afridar.” (In: Archaeology in Israel by Samuel R. Wolff) American Journal of Archaeology 100 (1996): 750.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, Hajar ‘Id.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 16 (1997). 122-123.

WC Golani, Amir and I. Milevski. “Ashqelon, Afridar (A).” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 19 (1999): 82*-83*.

WC Gophna, Ram., et al. “The Early Bronze Age Site at Ashquelon, Afridar.” ‘Atiqot 45. Jerusalem 2004.

GS Gophna, Ram and I. Milevski . “Feinan and the Mediterranean During the Early Bronze Age.” Tel Aviv 30/2 (2003): 222-231.

GS Gophna, Ram and N. Liphschitz. “The Ashkelon Trough Settlements in the Early Bronze Age I: New Evidence of Maritime Trade.” Tel Aviv 23/2 (1996): 143-153.

WC Gophna, Ram. “Afridar 1968: Soundings in an EB I Occupation of the “Erani C Horizon.” In: Ahron Kempinski Memorial Volume. Studies in Archaeology and Related Disciplines. Beer-Sheva 15 (2002): 129-137.

WC ---. “Elusive Anchorage Points along the Israel Littoral and the EgyptianCanaanite.” In: Egypt and the Levant: Interrelations from the 4th through the Early 3rd Millennium BCE. London 2002, 418-421.

WC ---. “The Southern Coastal Troughs as EB I Subsistance Areas.” Israel Exploration Journal 47 (1997): 155-161.

WC Goren, Yuval., et al. Inscribed in Clay: Provenance Study of the Amarna Tablets and other Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Tel Aviv 2004, 27, 294-299.

WC Greene, Joseph. "Ascalon." In Encyclopedia of Early Christian Art and Archaeology. Ed. P. Corby Finney. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 2011.

WC Hakim, Besim S. “Julian of Ascalon’s Treatise of Construction and Design Rules from Sixth-century Palestine.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 60 (2001): 4-25.

WC Halpern, Baruch. “The Canine Conundrum of Ashqelon: A Classical Connection?.” In: The Archaeology of Jordan and Beyond: Essays in Honor of James A. Sauer. eds. L.E. Stager et. al. Winona Lake, IN: 2000, 133-144.

WC ---. David’s Secret Demons: Messiah, Murderer, Traitor, King (The Bible in its World). Grand Rapids, MI: 2001.

WC Hoch, Martin. “The Crusaders’ Strategy Against Fatimid Ascalon and the “Ascalon Project” of the Second Crusade.” The Second Crusade and the Cistercians (ed. M. Gervers). New York: 1992, 119-128.

WC Hoffman, Tracy. “Ascalon on the Levantine Coast.” Changing Social Identity with the Spread of Islam: Archaeological Perspectives (University of Chicago Oriental Institute Seminars 1; ed. D. Whitcomb). Chicago, IL: 2004, 25-49.

WC Huehnergard, John and W. van Soldt. "A Cuneiform Lexical Text from Ashkelon with a Canaanite Column." Israel Exploration Journal 49 (1999): 184-192.

WC Israel, Yigael. “Ashqelon” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 13 (1993), 100-105.

WC ---. “The Economy of the Gaza-Ashkelon Region in the Byzantine Period in the Light of the Archaeological Survey and Excavations of the '3rd Mile Estate' near Ashkelon.” Michmanim 8 (1995): 16*-17*.

WC Israeli, Shoshana. “Ashqelon, Afridar (B).” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 19 (1999): 83*-85*.

WC Johnson, Barbara and L. E. Stager. "Ashkelon: Wine Emporium of the Holy Land." American Journal of Archaeology 97 (1993): 334.

WC Katsnelson, Natalya. “Glass Vessels from the Painted Tomb at Migdal Ashqelon,” ‘Atiqot 37 (1999), 67*-82*.

WC Keel, Othmar. "Aschkelon." In Corpus der Stempelsiegel—Amulette aus Palästina/Israel vol. 1. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 13. Ed., 688-736 (nos. 1-120). Freiburg: Freiburg University, 1997.

WC Khalaily, Hamudi and Z. Wallach. “Ashqelon, Ha-Tayysim Street.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 18 (1998): 100-101.

WC Kingsley, Sean A. “The Economic Impact of the Palestine Wine Trade in Late Antiquity.” Economy and Exchange in the East Mediterranean during Late Antiquity: Proceedings of a Conference, Somerville College, Oxford, 29.5.1999. eds. S. Kingsley & M. Decker. Oxford: 2001, 44-68.

WC Kogan-Zehavi, Elena. “A Painted Tomb of the Roman Period at Migdal Ashqelon.” ‘Atiqot 37 (1999): 179*-181*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 16 (1997): 123-126.

WC ---. “Late Roman-Byzantine Remains at Ashqelon.” ‘Atiqot 38 (1999): 230-231.

WC ---. “Migdal Ashqelon.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 15 (1996): 94-97.

WC Kol-Ya’aqov, Shlomo and Y. Shor. “Ashqelon, en-Nabi Husein.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 110 (1999): 73*-75*.

GS Kushnir-Stein, Alla. “On the Chronology of Some Inscribed Lead Weights from Palestine.” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palastina-Vereins 113 (1997): 88-91.

WC Lewin, Ariel. “Ashkelon (Ascalon.” In: The Archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2005, 156-161.

WC Masarwah, Yumna. “Tel Ashqelon.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 111 (2000): 86*.

WC Master, Daniel. M. "From the Beqe'ah to Ashkelon." In Exploring the Longue Durée: Essays in Honor of Lawrence E. Stager. Ed. J. David Schloen, 305-317. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2009.

WC ---. "The Renewal of Trade at Iron 1 Ashkelon." Eretz Israel 29, Stern Volume (2009): 111-122.

WC —. "Iron I Chronology at Ashkelon: Preliminary Results of the Leon Levy Expedition," in The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating: Archaeology, Text and Science, ed. T. Levy. Equinox, 2005.

WC —. "Ashkelon" in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books, ed. B. T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2005.]

WC Mayerson, Philip. "An Additional Note on Ascalon Wine (P. Oxy. 1384)." Israel Exploration Journal 45 (1995):190.

WC —. "The Use of Ascalon Wine in the Medical Writers of the Fourth to the Seventh Centuries." Israel Exploration Journal 43 (1994): 169-173.

WC Mayerson, Philip. “The Gaza “wine” jar (Gazition) and the “lost” Ashkelon” Jar (Askalonion).” Israel Exploration Journal 42 (1992): 76-80.

WC Michaeli, Talia. “The Pictorial Program of the Roman Period Tomb at Migdal Ashqelon.” Michmanim 14 (2000): 18*-19*.

WC Michaeli, Talia. “The Wall-paintings of the Migdal Ashqelon Tomb.” ‘Atiqot 37 (1999): 181*-183*.

GS Mildenberg, Leo. “On Fractional Silver Issues in Palestine.” Transeuphratene 20 (2000): 89-100.

GS Na’aman, Nadav. “Two Notes on the History of Ashkelon and Ekron in the Late Eighth-Seventh Centuries B.C.E.” Tel Aviv 25/2 (1998): 219-227.

WC Nahshone, Pirhiya. “Ashqelon, Khirbet Kisas.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 113 (2001): 109*-110*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, Migdal (North).” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 19 (1999): 81*-82*.

WC Palatnik, Michal. 5,500 Years Old Metal Production in Ashkelon: the Mean of the Archaeological Evidence. (M.A. thesis): Rehovot 1999.

WC Perrot, J. and A. Gophner, “A Late Neolithic Site Near Ashkelon” Israel Exploration Journal 46 (1996), 145-166.

G “Prize Find: Ashkelon’s Mudbrick Arch.” Biblical Archaeology Review 19/1 (1993): 46-47.

G Rainey, Anson F. “Israel in Merenptah’s Inscription and Reliefs.” Israel Exploration Journal 51 (2001): 57- 75.

WC Richter, Tonio Sebastian. “A Hitherto Unknown Coin of Ascalon.” Israel Numismatic Journal 13 (1994-1999): 83-85.

WC Rose, Mark. “Ashkelon’s Dead Babies.” Archaeology 50/2 (1997): 12-13.

WC Rosen-Ayalon, Miriam. "The Islamic Jewellery From Ashkelon In Jewellery and Goldsmithing.” in the Islamic World: International Symposium, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1987. Ed. N. Brosh, 9-20. Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1991.

WC ---. “Medieval Archaeology: Islamic Art and Archaeology.” Biblical Archaeologist 56 (1993): 146-148.

WC Saliou, Catherine. Le traite d’urbanisme de Julien d’Ascalon: Droit et Architecture em Palestine au VIeme siècle. (Travaux et Memoires du Centre de Recherche D’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance Monographies 8): Paris 1996.

WC Schloen, David. "Ashkelon." In Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. Ed. E. Meyers, vol. 1, 220-223. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1997.

WC ---. ASOR Newsletter. 48/1 (1998), 20.

WC Segal, Irina., et al. A Study of the Metallurgical Remains from Ashkelon Afridar Areas E, G, and H. (Geological Survey of Israel): Jerusalem 1997.

WC Shalev, Sariel. “Early Bronze Age I Copper Production on the Coast of Israel: Archaeometallurgical Analysis of Finds From Ashkelon-Afridar.” In: Culture Through Objects: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of P.R.S. Moorey (P. R. S. Moorey Fest.; Griffth Institute Publicaitons; eds. T. Potts et al.): Oxford 2003, 313-324.

WC ---. “Archaeometallurgy in Israel: Impact of the Material on the Choice of Shape, Size and Colour of Ancient Products.” Archaeometry 94 (International Symposium on Archaeometry, METU & TUBITAK, Ankara, Turkey, 1994): 1996, 10-15.

---. “What did the EBI People do on the Coast of Ashkelon?” (Settlement, Civilization and Culture): Bar-llan University 2001.

WC Sharon, Moshe. "A New Fatimid Inscription from Ascalon and Its Historical Setting." 'Atiqot 26 (1997): 61-86.

WC —. Egyptian Caliph and English Baron: The story of an Arabic inscription for Ashkelon. Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1994.

GS Smith, Patricia and G. Avashai. “The use of dental criteria for estimating postnatal survival in skeletal remains of infants.” Journal of Archaeological Science 32/1 (2005): 83-89.

WC Smith, Patricia and G. Kahila. "Identification of Infanticide in Archaeological Sites: A Case Study from the Late Roman-Early Byzantine Periods at Ashkelon, Israel." Journal of Archaeological Science 19 (1992): 667-675.

WC Stager, Lawrence E. and P. J. King. Life in Biblical Israel. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 2001.

WC Stager, Lawrence E. "Port Power: The Organization of Maritime Trade and Hinterland Production." In Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and Neighboring Lands: In Memory of Douglas L. Esse. SAOC 59, ASOR Books 5. Ed. S. R. Wolff, 625-638. Atlanta, GA: ASOR, 2001.

WC Stager, Lawrence E. and P. Smith. "DNA Analysis Sheds New Light on Oldest Profession at Ashkelon." Biblical Archaeology Review23/4 (1997): 16.

WC Stager, Lawrence E. and P.A. Mountjoy. "A Pictorial Krater from Philistine Ashkelon," in Up to the Gates of Ekron [1 Samuel 17:52]: Essays on the Archaeology and History of the Eastern Mediterranean in Honor of Seymour Gitin, eds. S.W.Crawford et al, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2007.

WC Stager, Lawrence E. and F. M. Cross, "Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions Found in Philistine Ashkelon," Israel Exploration Journal 56/4, 2006.

Stager, Lawrence E., M. Bietak and K. Kopetzky. "Stratigraphie Comparee Nouvelle: the Synchronisation of Ashkelon and Tell el-Dab`a" in International Conference on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (ICAANE) vol. 3 (Conference held in Paris, April 2003) eds. Pierre de Miroschedji and Jean-Paul Thalmann, pp. 221-234.

WC Stager, Lawrence E. and R. J. Voss. "A Sequence of Tell el Yahudiyah Ware from Ashkelon" in Tell el Yahudiyah Ware from Egypt and Levant, ed. M. Bietak. Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Vienna., 2010.

WC Stager, Lawrence E. "Ashkelon and the Archaeology of Destruction." In Eretz Israel 25 [Joseph Aviram Volume]. Ed. A. Biran, et al., 61*-74*. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1996.

WC —. "The Fury of Babylon." Biblical Archaeology Review 22/1 (1996): 58-69, 76-77.

WC —. "The Impact of the Sea Peoples in Canaan (1185-1050 BCE)." In The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Ed. Thomas E. Levy, 332-348. New York, NY: Facts on File, 1995.

WC —. "Ashkelon." New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations In the Holy Land. Ed. E. Stern, vol. 1,103-112. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1993.

WC —. "The MB IIA Ceramic Sequence at Tel Ashkelon and Its Implications for the 'Port Power' Model of Trade." In The Middle Bronze Age in the Levant: Proceedings of an International Conference on MB IIA Ceramic Material, Vienna, 24th-26th of January 2001. Ed. M. Bietak, 353-362. Wien: Verlag Der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2002.

WC —. "Chariot Fittings from Philistine Ashkelon," Confronting the Past: Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever, eds. S. Gitin, J.E. Wright, and J.P. Dessel. Eisenbrauns 2006, pp. 169-176.

WC —. "Biblical Philistines: A Hellenistic Literary Creation?" in "I Will Speak the Riddles of Ancient Times:" Archaeological and Historical Studies in Honor of Amihai Mazar, eds. A. Maeir and P. de Miroschedji. Eisenbrauns 2006, pp.375-384.

WC —. "New Discoveries in the Excavations of Ashkelon in the Bronze and Iron Ages," Qadmoniot. Vol. 39, No. 131, 2006 (Hebrew).

WC —. "The House of the Silver Calf of Ashkelon" in Timelines: Studies in Honour of Manfred Bietak Volume II, eds. E. Czerny, I. Hein, H. Hunger, D. Melman, and A. Schwab, Peeters 2006, pp 403-410.

WC —. "Das Silberkalb von Aschkelon." Antike Welt 21/4 (1990): 271-272.

WC —. Ashkelon Discovered: From Canaanites and Philistines to Romans and Moslems. Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1991.

WC —. "Un Veau d'argent déacouvert à Ashqelôn." Le Monde de la Bible 70 (1991): 50 52.

G —. "When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon." Biblical Archaeology Review 17/2 (1991): 24 43.

G —. "Why Were Hundreds of Dogs Buried at Ashkelon?" Biblical Archaeology Review 17/3 (1991): 27 42.

G —. "Eroticism and Infanticide at Ashkelon." Biblical Archaeology Review 17/4 (1991): 35-53.

WC ---. Recent Excavations in Israel: A View to the West; Reports on Kabri, Nami, Miqne-Ekron, Dor, & Ashkelon. (Archaeological Institute of America, Colloquia and Congerence Papers 1; ed. S. Gitin): Dubuque, IA 1995, 95-106.

WC Stager, Lawrence E. and D. Esse. "Notes and News: Ashkelon." Israel Exploration Journal 37 (1987): 68-72.

GS Sternberg, Rob., et al. “Anomalous Archaeomagnetic Directions and Site Formation Processes at Archaeological Sites in Israel.” Geoarchaeology 14/5 (1999): 415- 439.

WC Thompson, Christine. "Sealed Silver in Iron Age Cisjordan and the 'Invention' of Coinage." Oxford Journal of Archaeology 22/1 (2003): 67-107.

WC Varga, Daniel. “Ashqelon (B).” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 115 (2003): 60*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, Afridar and Barnea’ (A).” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 114 (2002): 87*-88*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, Afridar and Barnea’ (B).” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 114 (2002): 89*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, Ben-Gurion Street.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 110 (1999): 72*-73*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, Ben-Zvi Street.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 110 (1999): 70*-71*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, Hof Ha-Dayyagim (Fishermen’s Beach).” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 109 (1999): 89*.

WC Voss, Ross. "A Sequence of Four Middle Bronze Gates in Asheklon." In The Middle Bronze Age in the Levant: Proceedings of an International Conference on MB IIA Ceramic Material, Vienna, 24th-26th of January 2001. Ed. M. Bietak,.379-384. Wien: Verlag Der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2002.

WC Wallach, Zvi. “Ashqelon (A). ” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 115 (2003): 58*-59*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, el-Jura.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 20 (2000): 120*-121*.

P Waldbaum, Jane. “Trade Items or Soldiers’ Gear? Cooking Pots from Ashkelon, Israel,” in Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidze, edited by Daredjan Kacharava, Murielle Faudot et Évelyne Geny. (Paris: Presses Universitaires Franc-Comtoises, 2002), pp. 133-140.

GB Waldbaum, Jane. “Seventh Century B.C. Greek Pottery from Ashkelon, Israel: An Entrepôt in the Southern Levant,” in Pont-Euxin et Commerce. La Genèse de la “Route de la Soie,” Actes du Ixe Symposium de Vani (Colchide) - 1999, edited by M. Faudot, A. Frayesse and É. Geny. Institut des Sciences et Techniques de l’Antiquité. (Paris: Presses Universitaires Franc-Comtoises, 2002), pp. 57-75 .

WC Wapnish Paula and B. Hesse. "Pigs' Feet, Cattle Bones and Birds' Wings." Biblical Archaeology Review 22/1 (1996): 62.

GS Wapnish, Paula. "Beauty and Utility in Bone: New Light on Bone Crafting." Biblical Archaeology Review 17/4 (1991): 54-57.

DL Weiss, Ehud and M. E. Kislev. “Weeds and Seeds: What Archaeobotany can Teach Us.” Biblical Archaeology Review 30/6 (2004): 32-37.

WC Weiss, Ehud and M. E. Kislev. "Plant Remains as Indicators for Economic Activity: A Case Study from Iron Age Ashkelon." Journal of Archaeological Science 31 (2004): 1-13.

Wenning, R., “A representation of Caracalla in Ashkelon.” Moisikos ANER (M. Wegner Fest.) Antiquitas Series 3/32, Bonn 1992, 499-510.

WC Whincop, Matthew R. “Aspects of Cultic Ritual within early Philistia: Who are you calling a Philistine?.” Buried History 37-38 (2001-2002): 25-44.

GS Wolff, Samuel R. “Archaeology in Israel.” American Journal of Archaeology 100/4 (1996): 732-733.

GS ---. “Ashkelon (Afridar).” In: “Archaeology in Israel.” American Journal of Archaeology 98/3 (1994): 486-487.

WC Yekutieli, Yuval. “The Early Bronze Age IA of Southwestern Canaan.” In: Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and Neighboring Lands in Memory of Douglas L. Esse. Chicago, IL 2001, 659-688.

WC Younger, K. Lawson. “Yahweh at Ashkelon and Calah? Yahwistic Names in Neo-Assyrian.” Vetus Testamentum 52/2 (2002): 207-218.

WC Zelin, Alexey. “Ashqelon, Barnea’.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 113 (2001): 108*-109*.

WC ---. “Ashqelon, Barnea’.” Excavations and Surveys in Israel 114 (2002): 86*-87*.

PhD Dissertations

WC Aja, Adam J. "Philistine Domestic Architecture in the Iron Age I." Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2009.

WC Baker, Jill L. "The Middle and Late Bronze Age Tomb Complex at Ashkelon, Israel: The Architecture and the Funeral Kit." Ph.D. diss., Brown University, 2003.

WC Barako, Tristan. "The Seaborne Migration of the Philistines." Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2001.

WC Ben-Shlomo, David. Pottery Production Centers in Iron Age Philistia: An Archaeological and Archeometric Study (Ph.D. diss.): Jerusalem 2005.

WC Burke, Aaron. The Architecture of Defense: Fortified Settlements of the Levant during the Middle Bronze Age (Ph.D. diss.): Chicago 2004.

WC Di Segni, Leah. Dated Greek Inscriptions from Palestine from the Roman and Byzantine Periods (Ph.D. diss.): 1-2. Jerusalem 1997.

WC Hoffman, Tracy L. "Ascalon 'Arus Al Sham: Domestic Architecture and the Development of a Byzantine-Islamic City." Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 2003.

WC Lipovitch, David. "Can These Bones Live Again? An Analysis of the Persian Period Non-Candid Mammalian Faunal Remains from Tel Ashkelon." Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1999.

WC Master, Daniel. "The Seaport of Ashkelon in the Seventh Century BCE: A Petrographic Study." Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2001.

Voulgaridis, George. Les ateliers monetaires de Ptolemais- ‘Akko et d’Ascalon sous la domination Seleucide, 1-2 (Ph.D. diss.): Strasbourg 2000.

WC Yasur-Landau, Assaf. Social Aspects of Aegean Settlement in the Southern Levant in the End of the 2nd Millennium BCE (Ph.D. diss.): Tel Aviv 2002.

Gm\rin, Judee2, 135ff., 153ff.

J. Garstang, PEQ 53 (1921), 12-16,73-75, 162ff.

54 (1922), 112-119 (with

map of site)

56 (1924), 24-35

W. Phythian-Adams, ibid. 53 (1921), 163-169

55 (1923), 60-84

J. H.

Illife, QDAP 2 (1933), 11-14, 110-112

3 (1934), 165-166 (sculpture)

5 (1936), 61-68 (bronze figurines);

J. Ory, ibid. 8 (1939), 38-44 (tombs)

M. Avi-Yonah, ibid. 4(1935), 148-149 (lead collins)

id., 'Atiqot II

(1976), 72-76

id., Rabinowitz Bulletin 3 (1961), 61 (synagogue remains)

J. Perrot, IEJ5 (1955), 270-271;

G. Radan, ibid. 8 (1958), 185-188 V. Tsaferis, IEJ 17 (1967), 125-126 (basilica)

U. Rappaport, ibid. 20

(1970), 75-80

P.R. Diplock, PEQ 103 (1971), 11-16

B. Bagatti, LA 24 (1974), 227-264

T. Noy, IEJ24

(1974), !33-134

L. Y. Rahmani, ibid., 110-111

id., ibid. 37 (1987), 134-135

39 (1989), 66-70

B. Z.

Kedar and W. G. Mook, IEJ 28 (1978), 173-176

G. Koch, Archiiologischen Anzeiger 1979, 233-238;