Hebron - Tell Rumeida

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tel Rumeida | Arabic | تل رميدة |

| Tel Rumeida | Hebrew | תל רומיידה |

| Jabla al-Rahama | Arabic | |

| Tel Hebron |

- from Chat GPT 5, 4 November 2025

- sources: Wikipedia – Tel Rumeida

Excavations have revealed substantial remains from the Middle Bronze and Iron Age fortifications, including massive cyclopean walls and glacis systems that attest to Hebron’s importance as a fortified urban center during the second millennium BCE. Later strata include domestic structures, industrial installations, and public buildings from the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods.

The site’s proximity to the Tomb of the Patriarchs suggests a long-standing sacred association, reflected in its continued habitation and reuse across eras. Archaeological phases from the Roman–Byzantine through early Islamic periods show adaptive reuse of earlier structures, alongside evidence of later Ottoman occupation.

- from Hebron - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Satellite (Google) View of Hebron

from biblewalks.com

Annotated Satellite (Google) View of Hebron

Annotated Satellite (Google) View of Hebron

biblewalks.com - Tell Rumeida in Google Earth

- Tell Rumeida on govmap.gov.il

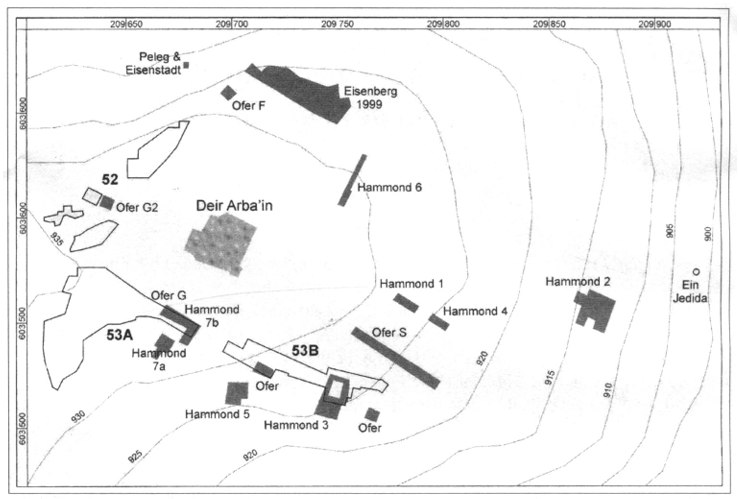

- Fig.1 Excavation Areas

from Ussishkin (2021)

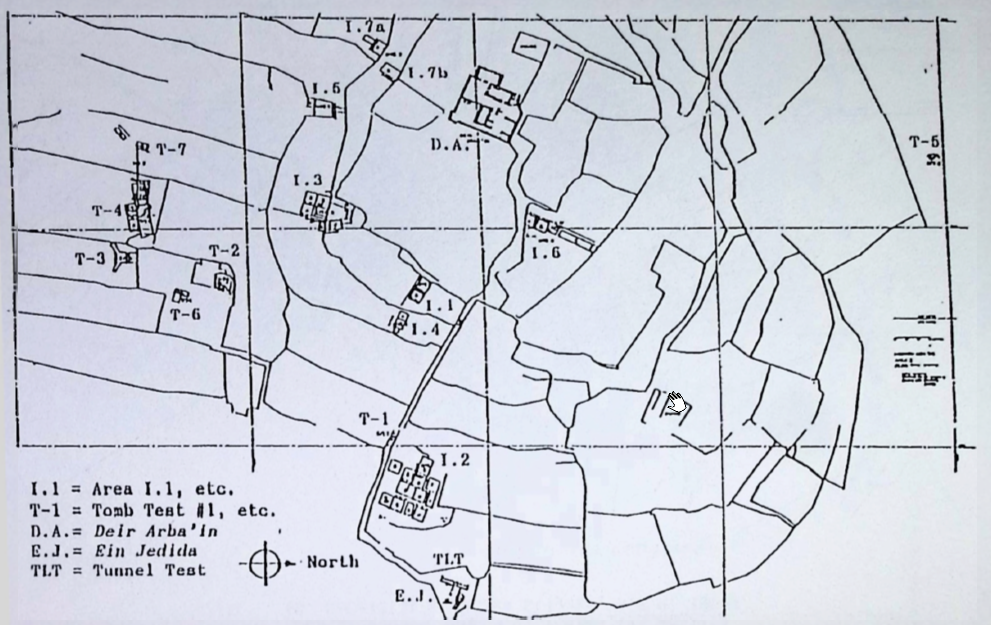

- Excavation Areas at Tell Rumeida from Chadwick (1993)

- Fig.1 Excavation Areas

from Ussishkin (2021)

- Excavation Areas at Tell Rumeida from Chadwick (1993)

| Period / Phase | Relative Date | Site-wide Stratigraphic Summary (from Ofer 1993) | Areas / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze I (EB I) | early 3rd millennium BCE | Earliest occupation; few wall sections and rock shelters used as dwellings. | Area 11 (levels), Area 13 (EB I outside MB wall); burial caves mainly SE; spring at Area W. |

| Early Bronze II–III (EB II–III) | 3rd millennium BCE | Settlement continued, but no substantial remains excavated yet. | Referenced site-wide; limited exposures. |

| Intermediate Bronze (MB I) | late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BCE | Whether fully abandoned is unclear; shaft tombs indicate at least a tribal-nomadic center. | Within modern city limits; site-wide inference. |

| Middle Bronze II (MB II) | 2nd millennium BCE | Fortified city (≈6–7 a.) with cyclopean wall; city is major Judean Hills center; Akkadian tablet listing sacrificial animals (sheep/goats), names, possibly a king; West Semitic with Hurrian minority; rich MB pottery spectrum; Egyptian 12th-Dynasty bulla and socketed axe. | Area S (tablet room, finds); Area 13 (city wall); Area F (MB wall continues); Area G (outer face of MB wall; later glacis). |

| Late Bronze Age | 2nd millennium BCE | City abandoned; burials continue in environs and outskirts; limited possible residential use. | Burial caves SE; outskirts of Tel Hebron. |

| Iron Age I | early 1st millennium BCE | Permanent occupation resumes (Calebites). Hebron likely not fortified on eve of Israelite settlement; earlier cyclopean walls later reused; glacis partly destroyed before Iron Age. | Area 11 (levels); burial cave continuous use into Iron I. |

| Iron Age IIA–IB (two phases) | 1st millennium BCE | Two phases present in the central section. | Area S (two phases noted). |

| Iron Age II (two phases) | 1st millennium BCE | Dense occupation; site’s zenith in 11th–10th c. BCE; probable expansion beyond MB walls; later decline. Finds include five lamelekh seal impressions (two inscribed “Hebron”). | Area 11 (pillared house); Area 13 (tower reused); Area F (revetment outside MB wall, likely 11th–10th c. BCE). |

| Persian | late 1st millennium BCE | Mound completely abandoned; city shifts to valley at foot of tell; start of valley occupation uncertain. | Site-wide note. |

| Hellenistic | Hellenistic | Occupation resumes on mound, probably as suburb of lower city. | Area G (large building begins). |

| Roman | 1st–2nd c. CE | Settlement flourishes; pool installations (possibly industrial); two violent destruction levels (likely Vespasian, then Bar-Kokhba). | Area G (twice destroyed; reused later). |

| Byzantine (two phases) | Late Antique | Two phases of occupation; reuse of earlier walls. | Area G (walls reused); Deir el-Arba‘in built on Byzantine foundations at summit. |

| Early Arab / Umayyad | 7th–8th c. CE | Occupation continues into Umayyad period. | Area 12 (Early Arab buildings; full pottery sequence). |

| Crusader | 12th–13th c. CE | Ongoing occupation; summit building possibly rebuilt in this period. | Deir el-Arba‘in superstructure perhaps Crusader. |

| Mamluk | 13th–16th c. CE | Occupation continues. | Site-wide note. |

| Ottoman | 16th c. CE onward | Mound completely abandoned. | Site-wide note. |

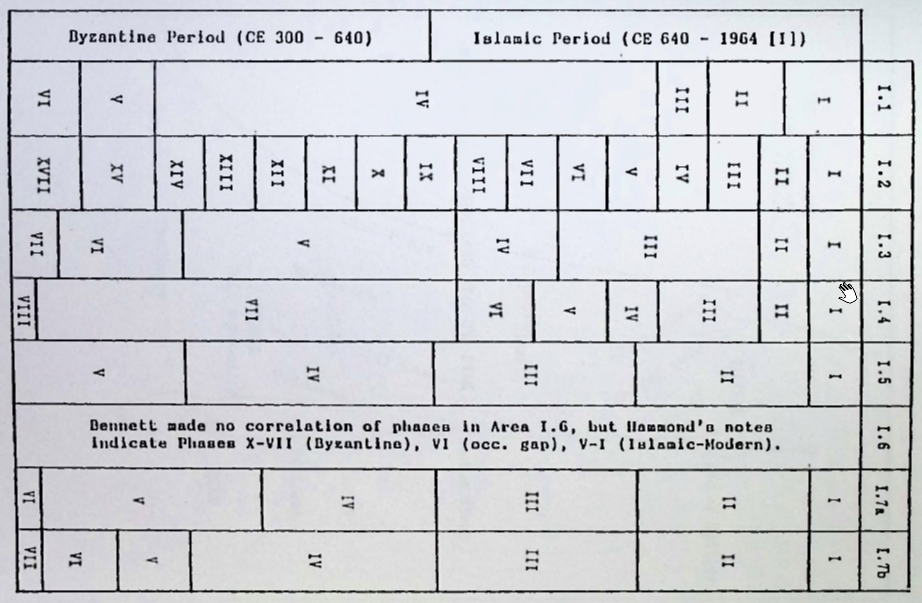

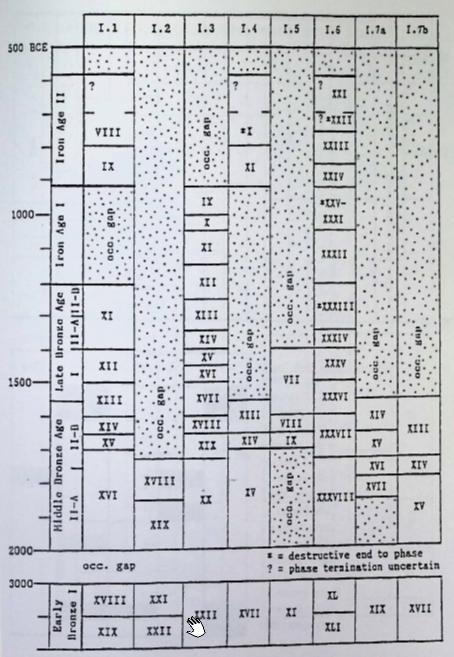

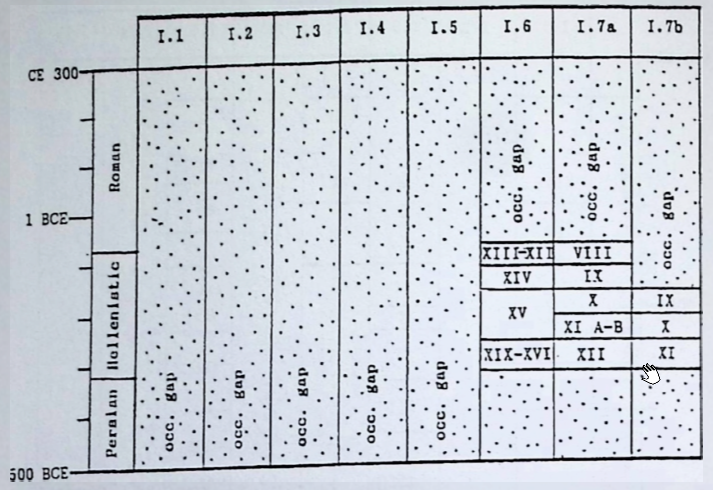

- from Chadwick (1993)

American Expedition to Hebron (A.E.H.) Phasing at Tell Rumeida

American Expedition to Hebron (A.E.H.) Phasing at Tell RumeidaCorrelated and drawn by Chadwick (1991)

click on image to open in a new tab

Chadwick (1993)

American Expedition to Hebron (A.E.H.) Phasing at Tell Rumeida

American Expedition to Hebron (A.E.H.) Phasing at Tell RumeidaCorrelated and drawn by Chadwick (1991)

click on image to open in a new tab

Chadwick (1993)

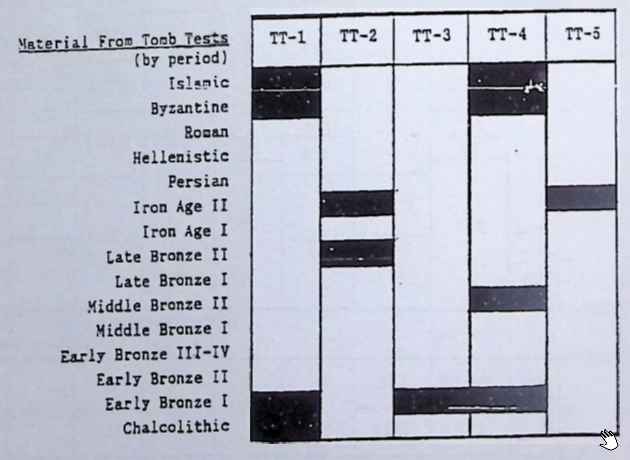

- from Chadwick (1993)

- from Chadwick (1993)

Tel Hebron lies on a secondary spur of Jebel Rumeida, overlooking the city of Hebron from the south. The first settlement was established near a spring ('Ein Judeida) and near an area of cultivated plots in the Hebron Valley. Topographically, the mound is not easily defensible, as it is dominated on the southwest by Jebel Rumeida. The debris on the mound covers an area of some 17 a., but the area of the ancient city was probably not more than 12 a.

The renewed excavations at Hebron were based on a central section (area S), intended to cut through the entire mound and determine its stratigraphical sequence. Thanks to the Middle Bronze Age city wall, it is possible to associate the other excavated areas, as well as some of the areas excavated by Hammond, with the section and its strata.

Area S. A stratigraphical sequence from the Early Arab period, Byzantine period (two phases), Roman period, Hellenistic period, Iron Age II (two phases), Iron Age IIA–IB (two phases), Iron Age I, and Middle Bronze Age has so far been exposed in Area S. The excavators have reached the top of an as yet unexcavated stratum, that dates to the end of the Early Bronze Age.

The most important structure in this area, ascribed to the Middle Bronze Age, is situated near the city wall. One room was used to collect ashes, animal bones, and potsherds. Also discovered in this room was a well-baked clay tablet, inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform, including a list of animals, most probably offered as sacrifices. Also mentioned in the tablet are the names of four people and possibly also a king. The animals listed include only sheep and goats; this complies with the great quantity of bones found at the site, most of which are from sheep and goats. The pottery uncovered here appears to represent a broad range of phases of the Middle Bronze Age. Discovered near the document was a bulla with scarab impressions from the time of the Twelfth Dynasty in Egypt; the finds in a nearby room included a socketed ax from the same period.

Area 13 (Southern City Wall). Exposed in Area 13 was the Middle Bronze Age city wall, which rose to a height of more than 2 m above the surface even before excavations began. Outside the wall the excavators reached bedrock, on which an Early Bronze Age I stratum was found. Incorporated in the wall from the inside was a fortified tower that exhibited evidence of repairs and repeated use during the Iron Age.

Area G. In Area G, in the western part of the mound, a large building, whose beginnings go back to the Hellenistic period, was uncovered. Its outer wall was excavated by Hammond as Area 17 and first mistakenly identified as part of the Middle Bronze Age wall. The structure continued in use in the Roman period, during which it was destroyed twice, probably in the first and second centuries CE. Its walls were reused in the Byzantine period. Also exposed here was the outer face of the Middle Bronze Age wall, against which a stone glacis was later built. Area G presents the easiest access to the mound. The excavators found indications of a rock-hewn fosse, and the city gate may have stood here as well.

Area F (Northern City Wall). Area F yielded the continuation of the Middle Bronze Age wall. Outside the wall was a revetment, which should probably be dated to the eleventh and tenth centuries BCE. If that is indeed the case, it would prove that the Iron Age city expanded beyond the limits of the Middle Bronze Age walls.

Area W. Hebron’s water source, 'Ein Judeida (New Spring), is in Area W (in the eastern and lowest part of the mound). The spring, whose water remains very cold throughout the year, was originally a surface groundwater spring. As the area of the spring was buried under debris accumulating from the mound, a domed structure was built over the site (in the Middle Ages?). Debris continued to accumulate on top of the dome, to the extent that today the spring seems to be flowing from a cave. A massive wall built at the inner end of the spring pool may be concealing a water system hewn inside the mound, but this is a conjecture that requires further research.

Area 11. Hammond excavated Area 11 (east of Area S), uncovering levels from the Early Bronze Age I, Middle Bronze Age, Iron Age I, and Iron Age II. He reported the discovery of a well-built pillared house from the Iron Age II.

Area 14. One terrace below Area 11 is Area 14. Here Hammond reported the presence of Arab buildings, overlying earlier remains, down to the Early Bronze Age I.

Area 16. The only area excavated to date on the acropolis of the mound is Area 16. It presented the stratigraphical sequence regularly found at Tel Hebron. Particularly noteworthy is the rich and dense occupation during the Iron Age. Hammond also found here a scarab of Ramesses II, but until his excavations become fully published, the level to which the scarab should be assigned remains unknown.

Area 12. A group of buildings which Hammond ascribed to the Early Arab period belongs to Area 12 (the eastern part of the mound). He also reported a complete sequence (at least in terms of pottery) of the other known periods of the mound, and similarly in Area 15 (in the southwest of the mound).

Hammond’s expedition also exposed some burial caves, mainly in the southeastern part of the mound. Some of them date to the Early Bronze Age I. He reported continuous occupation for one burial cave from the Middle Bronze Age through the Late Bronze Age (including Cypriot pottery) and perhaps also the Iron Age I.

Also noteworthy is Deir el-Arba‘in, a building at the summit of the mound, built on Byzantine foundations; the superstructure is probably later, perhaps from the Crusader period. Since the Middle Ages, popular tradition has identified the building with the tombs of Ruth and Jesse (David’s father), but there is no basis for this identification.

SUMMARY. The earliest known occupation of the mound was in the Early Bronze Age I, as part of a wave of settlement that occurred throughout the entire hill region. However, the only remains of this stratum exposed so far are a few sections of walls and rock shelters that apparently also served as dwellings.

Settlement continued through the Early Bronze Age II–III, but no remains have been excavated as yet. It is not clearly understood whether the site was completely abandoned during the Intermediate Bronze Age (Middle Bronze Age I). In any event, the shaft tombs within the modern city limits testify that the area was at the very least a tribal-nomadic center, like other sites in the hill region.

During the Middle Bronze Age II the site was occupied by a fortified city, some 6 to 7 a. in area, surrounded by a cyclopean wall. This city was the major settlement in the Judean Hills during the Middle Bronze Age. The cuneiform tablet dated to this period testifies to the city’s central role in the administration, apparently as the capital of a kingdom. The list of animals in the tablet, together with the bones found in the area, indicate that the local inhabitants were shepherds. The proper names on the tablet indicate a West Semitic (Amorite) population, with a Hurrian minority.

During the Late Bronze Age, the city of Hebron was abandoned; however, a tribal population continued to bury its dead in the environs, and even on the outskirts of Tel Hebron. It is possible that a small part of the site itself, besides serving as a necropolis, was also used for residential purposes. However, it would seem that during the Late Bronze Age there was no large, permanent settlement on the site. The permanent occupation of Hebron was resumed in the first phase of Iron Age I, apparently by the tribal unit known as the Calebites. Judging from the finds, it is unlikely that Hebron was a fortified town on the eve of the Israelite settlement. This detail in the Calebite tradition is probably etiological, a conjecture on the part of a late writer, who was probably familiar with the ancient cyclopean walls of Hebron and associated them with the tradition telling of the war with the Anakites. In fact, parts of these walls are still visible on the mound; in the Iron Age they rose to an even greater height and were probably a familiar sight and may well have been reused. The glacis (if such existed) was partly destroyed before the Iron Age.

The next occupational level at Tel Hebron represents the zenith of the city’s history, between the eleventh century and the end of the tenth century BCE. During that time the city probably extended beyond the line of the Middle Bronze Age walls. The latter were presumably used as fortifications for the upper sector of the city. Historically speaking, this golden age at Hebron reflects the city’s position as a tribal and religious center for the people of the Judean Hills and the first royal capital of King David.

In the later part of the Iron Age, Hebron's importance declined; the remains exposed from this phase are fragmentary. Hammond's excavations probably exposed more abundant evidence from the period of the monarchy, but it has not been published. The precise history of Hebron during that period, including the date of its final destruction, is unclear. An important find from the time of the monarchy are five lamelekh seal impressions on 609 storage jar handles. All five feature the two-winged symbol, and the two inscribed ones include the name Hebron. Notably, of the four cities named in the lamelekh seal impressions, Hebron is the only one that has also been confidently identified and excavated; hence, the considerable significance of the find.

During the Persian period Tel Hebron was completely abandoned; in subsequent periods the city shifted to its present location in the valley, at the foot of the mound. As the city of Hebron has not been excavated, it cannot be determined whether occupation of the area began during the Persian period.

Occupation of the mound resumed in the Hellenistic period, probably as a suburb of the lower city. During the Roman period, settlement flourished; to this period are dated pool installations of an uncertain, perhaps industrial, nature. Two violent destruction levels belong to this period—the first probably under Vespasian, the second perhaps during the Bar-Kokhba Revolt. The remains from the Byzantine period comprise two phases, and occupation continued into the Umayyad, Crusader, and Mamluk periods. Only in the Ottoman period was the mound completely abandoned.

Tomb Test #3, also on the southern slope about 80 meters southeast of I.3, revealed a subterranean chamber last used in the Early Bronze I period, probably as a dwelling, as in the case of TT-1. Three phases of occupation were detected, the uppermost featuring complete ceramic pieces left on the floor by the cave's Early Bronze I inhabitants, who probably fled the dwelling in consequence of an earthquake. The lower phases also showed primarily Early Bronze I ceramics, with possibly some very late Chalcolithic representatives, indicating to Hammond that "the transition between the two periods was chronological, not cultural" (Hammond 1966d:40). The earthquake seems to have sealed off the chamber from any use in later periods. TT-3 was excavated in 1964.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Tomb Test #3 (T-3) |

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tomb Test #3 (T-3) |

|

|

Anbar, M. and Na'aman, N. (1986-1987) An Account Tablet of Sheep from Ancient Hebron, Tel Aviv 13-14 (1986-1987), pp. 3-12

Chadwick, J.R. (1993) The Archaeology of Biblical Hebron in the Bronze and Iron Ages: An Examination of the Discoveries of the American Expedition to Hebron

(Ph.D. diss., Salt Lake City, UT 1992), Ann Arbor, MI 1993

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1965a). Hebron. *Revue Biblique, 72*(2), 267–270.

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1965b). David’s first city: The excavation of Biblical Hebron. *Princeton Seminary Bulletin, 58*(2), 19–28. – open access at Archive.org

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1966a). Hebron. *Revue Biblique, 73*, 566–569.

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1966b). *American Expedition to Hebron — Preliminary reports: 1963–1966* (Unpublished typewritten manuscript).

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1966c). Ancient Hebron, the city of David. *Natural History, 75*(5), 42–49.

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1966d). The search for ancient Hebron. *Dominion*, December 1966, 31–41.

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1968). Hebron. *Revue Biblique, 75*, 253–258.

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1971). The excavation of Biblical Hebron. *Newsletter of the Society for Early Historic Archaeology, 128*, 1–5.

Hammond, P. C., Jr. (1963–1966). *Notes on excavations and material finds at Tell er-Rumeide (Biblical Hebron)* (Unpublished field notes).

Jericke, D (2003) Abraham in Mamre: historische und exegetische Studien zur Region von Hebron und zu Genesis 11,27–19,38

(Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 17), Leiden 2003.

Ofer, A. (1984) Tell Rumeida / תל רומידה. Hadashot Arkheologiyot / חדשות ארכיאולוגיות, פה, 43–44. In Hebrew

Ofer, A. (1986) Tell Rumeida (Hebron) – 1985 / תל רומידה (חברון) – 1985. Hadashot Arkheologiyot / חדשות ארכיאולוגיות, פח, 28–28. In Hebrew

Ofer, A. (1988). Tell Rumeideh (Hebron) – 1986. *Excavations and Surveys in Israel, 6*, 92–93.

Ofer, A. (1989). Hapirat Tel Hevron (Atarah Shel Hevron HaMikrayit) [The excavation of Tel Hebron – the site of Biblical Hebron]. Unpublished Hebrew manuscript.

Ussishkin, D. (2021). The Date of the Cyclopean Wall at “Tell er-Rumēde / Tẹ̄l Ḥevrōn.”

Zeitschrift Des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (1953-), 137(2), 125–136.

Ofer, A. (1984) ESI/3 (1984), 94-95

Ofer, A. (1984) Tell Rumeida / תל רומידה. Hadashot Arkheologiyot / חדשות ארכיאולוגיות, פה, 43–44.

5 (1986), 92-93

6 (1987-1988), 92-93

M. Anbarand N. Na'aman, TA 1314 (1986-1987), 3-12.

Chadwick, J.R. (1993) The Archaeology of Biblical Hebron in the Bronze and Iron Ages: An Examination of the Discoveries of the American Expedition to Hebron

(Ph.D. diss., Salt Lake City, UT 1992),

Ann Arbor, MI 1993

Jericke, D (2003) Abraham in Mamre: historische und exegetische Studien zur Region von Hebron und zu Genesis 11,27–19,38

(Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 17), Leiden 2003.

S. Applebaum, ABD, 5, New York 1992, 614–615

P. W.

Ferris, Jr., ibid., 3, New York 1992, 107–108

B. Mazar, Biblical Israel: State and People (ed. S. Ahituv),

Jerusalem 1992, 78–87

M. Spaer, Journal of Glass Studies 34 (1992), 44–62

H. Hizmi & Z. Shabtai, JSRS

3 (1993), xiii–xiv

D. Amit, ibid. 4 (1994), xxii

Y. Baruch, ESI 14 (1994), 121–122

M. L. Fischer, Mediterranean Language Review 8 (1994), 20–40

id., EI 25 (1996), 106*–107*

A. Frisch, Abr-Nahrain 32 (1994),

80–96

F. N. Hepper & S. Gibson, PEQ 126 (1994), 94–105

A. Elad, Pilgrims and Travellers to The Holy

Land (Studies in Jewish Civilization, Creighton University, Center for the Study of Religion and Society,

7

eds. B. F. Le Beau & M. Mor), Omaha, NE 1996, 21–62

J. P. J. Olivier, Old Testament Essays 9 (1996),

451–464

P. C. Hammond, OEANE, 3, New York 1997, 13–14

Z. Safrai, The Missing Century: Palestine in

the 5th Century—Growth and Decline (Palestine Antiqua N.S. 9), Leuven 1998, (index)

A. A. Taveres, 34.

Rencontre Assyriologique International, Istanbul, 6–10.7.1987, Ankara 1998, 320–329

B. Grossfeld, The

Solomon Goldman Lectures 7 (1999), 47–65

J. Sudilovsky, BAR 25/6 (1999), 14

D. M. Jacobson, Levant

32 (2000), 135–154

M. Kochavi, Les routes du Proche-Orient des séjours d’Abraham aux caravans de

l’Anciens (MdB

ed. A. Lemaire), Paris 2000, 51–56

Y. Peleg (& Y. Feller), ESI 112 (2000), 104*

id. (& I.

Shrukh), ibid., 105*

id. (& I. Eisenstat), Burial Caves and Sites in Judea and Samaria from the Bronze and

Iron Ages (Judea and Samaria Publications 4

eds. H. Hizmi & A. De Groot), Jerusalem 2004, 231–259

A.

D. Petersen, Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk Eras, 3: Proceedinsg of the 6th, 7th, and

8th International Colloquium, Leuven, May 1997, 1998 and 1999 (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 102

eds.

U. Vermeulen & J. Van Steenbergen), Leuven 2001, 359–383

S. Batz & Y. Peleg, ESI 114 (2002), 90*–91*

E. Eisenberg & A. Nagorski, ibid., 91*–92*

M. Patella, The Bible Today 41 (2003), 32–37

J. R. Chadwick,

ASOR Annual Meeting 2004, www.asor.org/AM/am.htm

id., BAR 31/5 (2005), 24–33, 70–71

O. Keel &

S. Munger, Burial Caves and Sites (op. cit.), Jerusalem 2004, 13, 240–241, 276–278

B. Yuzefovsky, ibid.,

11–12, 83, 238–240.

Ben Shlomo, D., 2016. New Excavations in Tel Hebron, Kadmoniyot : A Journal for the Study of the Land of Israel and Bible Lands, 152:101-108 [Hebrew].

Eisenberg, E., 2011, Fortifications of Hebron in the Bronze Age, 30 Land of Israel: Studies in Knowledge of the Land of Israel and its Antiquities 31-40 [Hebrew].

Ibid.

Ben Shlomo, D. Eisenberg, E., 2017. The Remains in Area 53A: Stratigraphy and Architecture. In Ben Shlomo D.,

Eisenberg, E. (eds.) 2017. The Tel Hevron 2014 Excavations: Final Report: 137-152. Ariel: Ariel Univ.

Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series No. 1.

Reich, R. Ritual Baths in the Period of the Second Temple and in the Period of the Mishna and the Talmud

: 251-52, Jerusalem, Yad Yitzchak Ben Zvi [Hebrew].

Ben-Shlomo, D., 2017. The Ritual Baths (Miqwa’ot) at Tel Hevron, in Ben-Shlomo, D. Eisenberg, E. (eds.) 2017,

The Tel Hevron 2014 Excavations, supra note 4, 251-262. Ariel: Ariel Univ. Institute of Archaeology Monograph Series No. 1.

Magen, I., Peleg, Y., 2007. The Qumran Excavations 1992-2004: Preliminary Report, in Magen Y. (ed.)

Judea and Samaria Researches and Discoveries JSP 6:353-426. Jerusalem Staff Officer of Archaeology – Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria.

Eisenberg, E., 2016. Tel Hevron: The Excavations in 1999, 152 Kadmoniyot: Journal of Study of the Land of Israel and the Bible Lands 92-100 [Hebrew].

Id.

Id.

Batz, S., 2002, Hebron, Dir al-Arba’in, Archaeological News 114:144. [Hebrew]

Ofer, A., 1984, Tel Rumeida, Archaeological News, vol. 85, 43.