Gush Halav

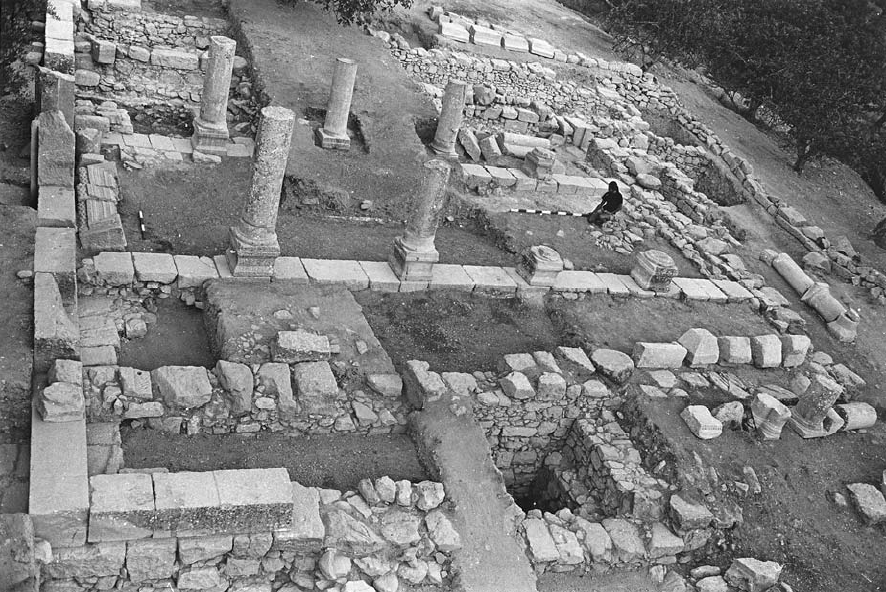

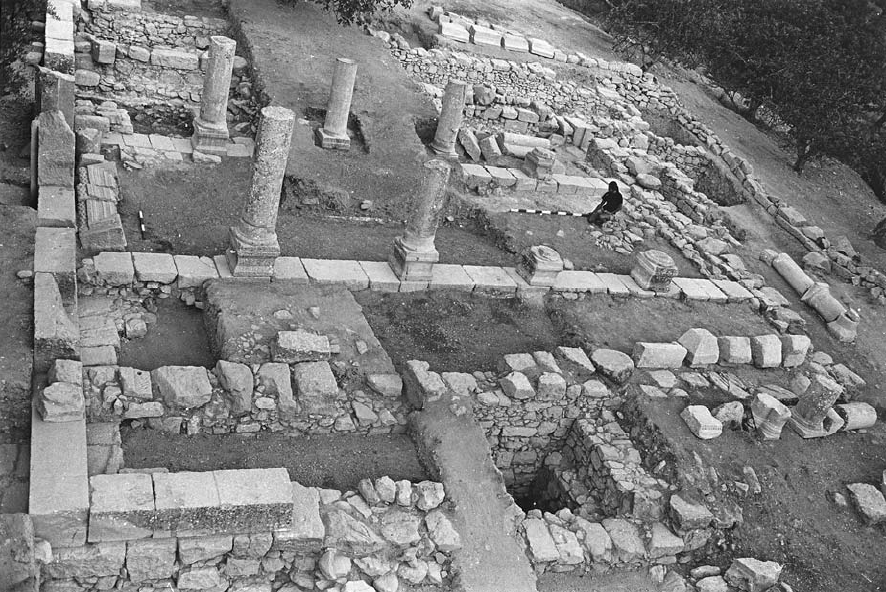

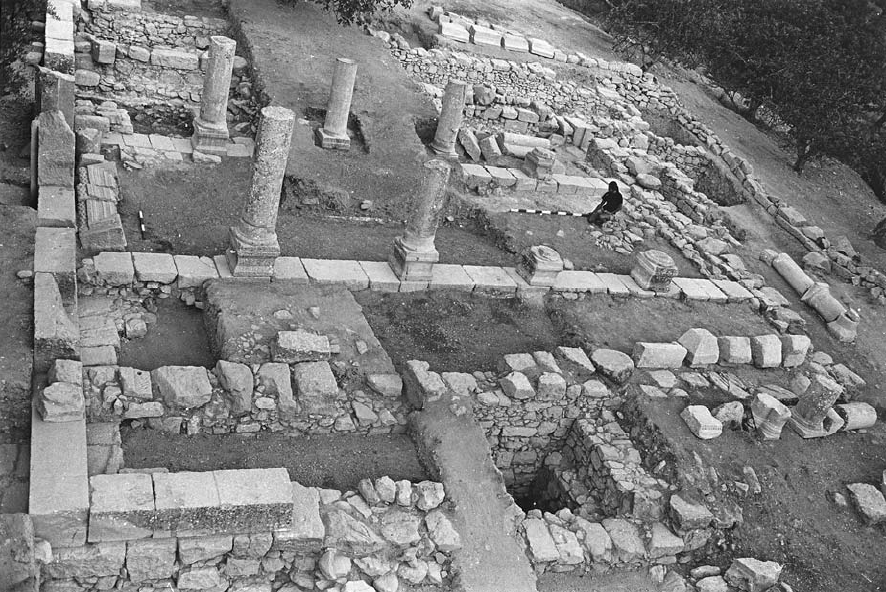

Photo 23

Photo 23Gush Halav basilical synagogue, with eight columns, looking northwest.

Meyers et al (2009)

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Gush Halav | Hebrew | |

| Jish | Arabic | الجش |

| Giscala |

It is mentioned in the Mishnah ('Arakh. 9:6) as a fortified city from the time of Joshua. Its walls were rebuilt in 66 CE, when Josephus fortified many cities and villages in the Galilee (Josephus, War II, 575, 590; Life 189). However, the city surrendered to Titus without a fight in 67 CE (War IV, 92-120). The town was the home of John of Gischala, one of the prominent Zealot leaders in the revolt and a bitter enemy of Josephus, who had survived the siege of Jerusalem to be led in chains in Titus' triumphal procession. According to Jerome (De Viris Illustritus, 5), Gischala was also the home of Paul's parents. Gush Halav (Fat Soil) produced fine olive oil (War II, 591-592; Life, 74-75; Tosefta, Men. 9: 5; B.T., Men. 85b). According to Jewish tradition of the Middle Ages, the town was famed for its graves of rabbis and ancient synagogue.

The Gush Halav settlement and the entire Meiron area were clearly oriented north, toward Tyre, into whose economic orbit both Khirbet Shema' and Gush Halav fell. The high percentage of coins minted in Tyre found at Gush Halav and Khirbet Shema' attests to the fact that regional trade was directed north, and that the cultural affinities were also northern - that is, southern Syrian. Ancient sources cite fine silk as well as olive oil among the products of Gush Halav. The presence of imported fine wares at the site indicates that the eastern Mediterranean world was very much a part of everyday life here.

Although the site received considerable attention in the nineteenth century by such notables as E. Renan, C. Wilson, V. Guerin, and H. H. Kitchener, the first scientific survey was completed by the Germans H. Kohl and C. Watzinger in 1905. Excavations were carried out at the site in 1977 and 1978 under the auspices of the American Schools of Oriental Research, under the direction of E. M. Meyers. C. L. Meyers and J. F. Strange served as associate directors. All other modern work at Gush Halav has been conducted at sites in el-Jish itself, including the site's upper synagogue on which the village's church was later built.

- Fig. 1 - Block plan of Gush Halav synagogue

from Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Block plan of Gush Halav synagogue

Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979)

- Photo 23 - Gush Halav basilical synagogue

from Meyers et al (2009)

Photo 23

Photo 23

Gush Halav basilical synagogue, with eight columns, looking northwest.

Meyers et al (2009)

Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) dated the construction of a Gush Halav synagogue (in Stratum VI) to around 250 A.D. and report the village was abandoned beforehand;

possibly after the Bar Kokhba Revolt. The date for building the synagogue is primarily based on ceramics but is

supplemented by 6 coins. Magness (2001a) proposed that the 'first' synagogue

at Gush Halav was constructed no earlier than the second half of the fifth century and perhaps as late as the first half of the sixth century

while adding that

there were no major earthquake destructions followed by reconstructions as envisioned by the excavators. Instead, occupation continued until the late seventh or early eighth century.

Although Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) interpret destruction at the end of VIa due to the

Eusebius' Martyr Earthquake of ~306 AD, their chronology is debated.

Magness (2001a) performed a detailed examination of the stratigraphy

presented in the final report of Meyers, Meyers, and Strange (1990) and concluded, based on numismatic and ceramic evidence,

that a synagogue was not built on the site until no earlier than the second half of the fifth century. While she agreed that earthquake destruction evidence was present in the excavation,

she dated the destruction evidence to some time after abandonment of the site in the 7th or 8th centuries AD.

Strange (2001) and

Meyers (2001) went on to rebut

Magness (2001a) to which

Magness (2001b) responded again. One point of agreement however is that

earthquake destruction evidence does appear to be present.

Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) also discussed this earthquake

Although the earthquake of 306 CE apparently did a great deal of damage to the structure, the stylobates were shored up and other repairs undertaken to make the period II building sturdier.

Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) report strong evidence for destruction at the end of VIb due to the northern Cyril Quake of 363 CE. Their discussion of archeoseismic evidence follows:

Therefore a second phase - VIb - of Late Roman occupation, after this seismic event, is postulated. This second Late Roman phase is also terminated by an earthquake, no doubt in A.D. 362. The coin evidence for this terminus is extremely illuminating, inasmuch as the earliest preserved surfaces of the western corridor contain coins which may extend at the latest until A.D. 365. Equally important, the ceramic repertoire from VIb corresponds precisely to that of Meiron Stratum IV and Khirbet Shema Stratum IV. In other words, there is a clear continuity in the ceramic tradition here, unmistakably late Roman. Whereas Stratum VIa contains many 3rd-century Middle Roman forms, these forms virtually disappear in VIb.Their misdating of the Cyril Quake to 362 AD is a mistake frequently found in older papers. Their mention of coins from the Western corridor extending "at the latest until 365 AD" is somewhat problematic as this coincides with the date of the Crete Earthquake of 365 AD. The epicenter of this earthquake was too far away to have produced archeoseismic damage at Gush Halav so this will be left as a numismatic mystery which does not infringe badly on their chronology. The biggest potential problem with their chronology is it is debated. Magness (2001a) performed a detailed examination of the stratigraphy presented in the final report of Meyers, Meyers, and Strange (1990) and concluded, based on numismatic and ceramic evidence, that a synagogue was not built on the site until no earlier than the second half of the fifth century. While she agreed that earthquake destruction evidence was present in the excavation, she dated the destruction evidence to some time after abandonment of the site in the 7th or 8th centuries AD. Strange (2001) and Meyers (2001) went on to rebut Magness (2001a) to which Magness (2001b) responded again.

Stratum VII, representing the Byzantine period, thus begins after the 362 earthquake and is characterized by significant localized repairs made within the building.

Netzer (1996) reviewed the original archaeological reports and although he agreed with the original dating of the material remains, he concluded that only one synagogue was constructed at Gush Halav and it was constructed in the first half of the 4th century CE. He further concluded that the seismic destruction of this synagogue dates to the 551 CE Beirut Quake. He did not interpret destruction in 363 CE that left a mark in the material remains.

Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) also discussed this earthquake

The second building period thus witnessed no major modification [for] the plan of the building. However, stratigraphic assessment of the data indicates quite clearly that great effort was made to reinforce corners, stylobates, and walls. The debris buildup in the western corridor in particular demonstrates how soon after the great 363 CE earthquake the basilica was reused. Many architectural fragments were then reused, and a smaller bema replaced the earlier and larger one on the southwest interior of the southern facade wall.

Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) attributed seismic destruction at the end of VIIb to the

551 CE Beirut Quake however their chronology is debated.

Magness (2001a) performed a detailed examination of the stratigraphy

presented in the final report of Meyers, Meyers, and Strange (1990) and concluded, based on numismatic and ceramic evidence,

that a synagogue was not built on the site until no earlier than the second half of the fifth century. While she agreed that earthquake destruction evidence was present in the excavation,

she dated the destruction evidence to some time after abandonment of the site in the 7th or 8th centuries AD.

Strange (2001) and

Meyers (2001) went on to rebut

Magness (2001a) to which

Magness (2001b) responded again. One point of agreement however is that

earthquake destruction evidence does appear to be present. Archeoseismic evidence at Gush Halav for the

551 CE Beirut Quake,

based on epicentral distance and the magnitude of the earthquake is very possible but unfortunately the chronology from this excavation is not clear.

Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) also discussed this earthquake

The final Byzantine phase (period IV), is basically attested through the buildup of floors, which were renewed regularly over time. A coin hoard of some 1,953 specimens was discovered in the western corridor. Although the latest coins do not extend to the great earthquake of 551 CE, the collapse of 19m of molding in the western corridor testifies to the building's collapse in a single event. [JW: The youngest coins date to 491-518 or 457-518 - Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979:54)]Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) add

The vivid reminder of the 551 disaster may be seen in the photographs of the excavated remains of this last phase of the synagogue's use as a sanctuary. All the major architectural elements collapsed, where they lay more or less unmoved until the recent excavations.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Walls ? | Synagogue

Figure 1

Figure 1Block plan of Gush Halav synagogue Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) |

Although the earthquake of 306 CE [JW: this date and earthquake assignment is debated] apparently did a great deal of damage to the structure, the stylobates were shored up and other repairs undertaken to make the period II building sturdier.- Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reused Building Elements and Displaced Walls | western corridor and elsewhere (?)

Figure 1

Figure 1Block plan of Gush Halav synagogue Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) |

The second building period thus witnessed no major modification [for] the plan of the building. However, stratigraphic assessment of the data indicates quite clearly that great effort was made to reinforce corners, stylobates, and walls. The debris buildup in the western corridor in particular demonstrates how soon after the great 363 CE earthquake [JW: This date and earthquake assignment is debated] the basilica was reused. Many architectural fragments were then reused, and a smaller bema replaced the earlier and larger one on the southwest interior of the southern facade wall.- Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

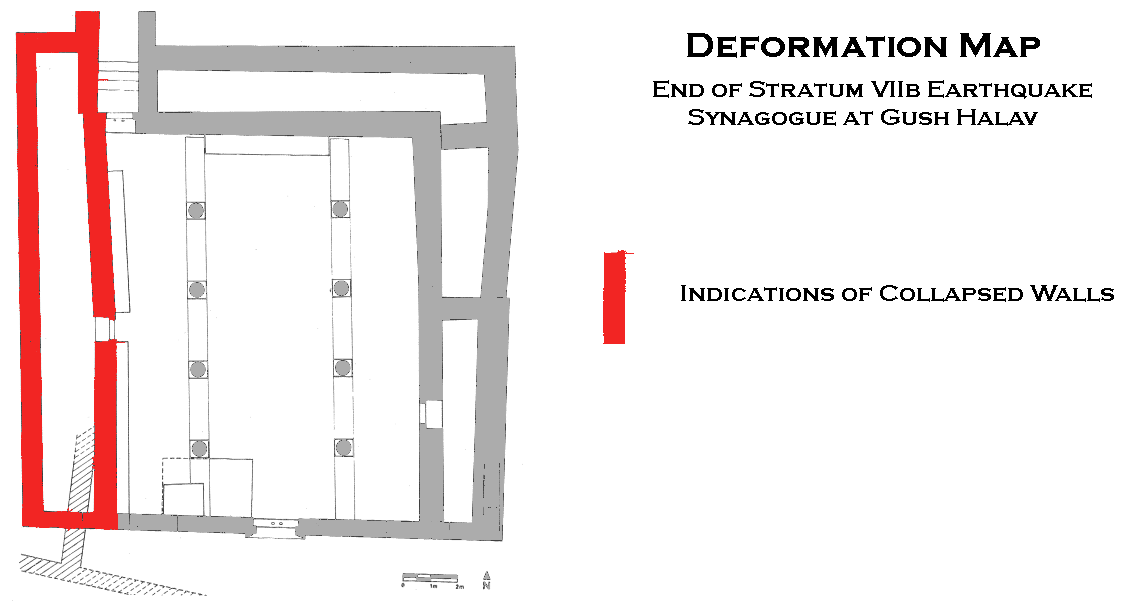

| Collapsed Walls | western corridor

Figure 1

Figure 1Block plan of Gush Halav synagogue Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) |

collapse of 19 m of molding in the western corridor testifies to the building's collapse in a single event.- Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) |

- Modified by JW from Fig. 1 of Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 1 of Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979)

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displaced Walls ? | Synagogue

Figure 1

Figure 1Block plan of Gush Halav synagogue Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) |

Although the earthquake of 306 CE [JW: this date and earthquake assignment is debated] apparently did a great deal of damage to the structure, the stylobates were shored up and other repairs undertaken to make the period II building sturdier.- Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) |

VII + |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reused Building Elements and Displaced Walls | western corridor and elsewhere (?)

Figure 1

Figure 1Block plan of Gush Halav synagogue Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) |

The second building period thus witnessed no major modification [for] the plan of the building. However, stratigraphic assessment of the data indicates quite clearly that great effort was made to reinforce corners, stylobates, and walls. The debris buildup in the western corridor in particular demonstrates how soon after the great 363 CE earthquake [JW: This date and earthquake assignment is debated] the basilica was reused. Many architectural fragments were then reused, and a smaller bema replaced the earlier and larger one on the southwest interior of the southern facade wall.- Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) |

VII + |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | western corridor

Figure 1

Figure 1Block plan of Gush Halav synagogue Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979) |

collapse of 19 m of molding in the western corridor testifies to the building's collapse in a single event.- Eric M. Meyers in Stern et al (1993 v. 2) |

VIII + |

Magness, J. (2001a). THE QUESTION OF THE SYNAGOGUE: THE PROBLEM OF TYPOLOGY. THE QUESTION OF THE SYNAGOGUE: THE PROBLEM OF TYPOLOGY, Brill: 1.

Magness, J. (2001b). A RESPONSE TO ERIC M. MEYERS AND JAMES F. STRANGE. Judaism in Late Antiquity 3. Where we Stand: Issues and Debates in Ancient Judaism, Brill: 79.

Meyers, Strange, Meyers, and Hanson (1979). "Preliminary Report on the 1977 and 1978 Seasons at Gush Halav (el-Jish)." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research(233): 33-58.

Meyers, E. M. (2001). THE DATING OF THE GUSH HALAV SYNAGOGUE: A RESPONSE TO JODI MAGNESS. Judaism in Late Antiquity 3. Where we Stand: Issues and Debates in Ancient Judaism, Brill: 49.

Russell, K. W. (1981). The earthquake chronology of ancient Palestine and Arabia from the 2nd to the 8th century A.D. Anthropology. Salt Lake City, UT, University of Utah. MS.

Russell, K. W. (1985). "The Earthquake Chronology of Palestine and Northwest Arabia from the 2nd through the Mid-8th Century A.D."

Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research 260: 37-59.

Strange, J. F. (2001). SYNAGOGUE TYPOLOGY AND KHIRBET SHEMAʿ: A RESPONSE TO JODI MAGNESS. SYNAGOGUE TYPOLOGY AND KHIRBET SHEMAʿ: A RESPONSE TO JODI MAGNESS, Brill: 71.

E. M. Meyers et al., Excavations at the Ancient Synagogue of Gush Halav (Meiron

Excavation Project 5), Winona Lake, Ind. 1990.

Kohl-Watzinger, Synagogen, 107-111

Goodenough, Jewish Symbols I, 205

E. M. Meyers,

IEJ27 (1977), 253-254; 28 (1978), 276-279; id., RB 85 (1978), 112-113; 86 (1979), 439-441; id. (eta!.),

BASOR233 (1979), 33-58; id., BA 43 (1980), 97-108; id., Ancient Synagogues: The State of Research (ed.

J. Gutmann), Chico, Calif. 1981, 61-77; id., ASR, 75-77; id., The Synagogue in Late Antiquity (ed. L. I.

Levine), Philadelphia 1987, 127-137

D. Chen, LA 38 (1988), 249-252.

F. Vitto, IEJ 24 (1974), 282; id., RB 82 (1975), 277-278.

N. Makhouly, QDAP8 (1938), 45-50

H. Hamburger, IEJ 4 (1954), 201-226

M. Avi'am, ESI

3 (1984), 37; 5 (1986), 44-45

I. Stepanski, ibid. 4 (1985), 39-40.

E. Damati & H. Abu ‘Uqsa, ESI 10 (1991), 70–72

E. M. Meyers, ABD, 2, New York 1992, 1029–1030; id.,

BASOR 297 (1995), 17–26; id., Judaism in Late Antiquity III/4, Leiden 2001, 49–70

R. K. Falkner, PEQ

125 (1993), 170–171 (Review)

P. Kaswalder, LA 43 (1993), 596–602 (Review)

R. Horsley, BASOR 297

(1995), 5–16, 27–28

E. Netzer, EI 25 (1996), 106*

C. L. Meyers, OEANE, 2, New York 1997, 442–443

G.

Bijovsky, ‘Atiqot 35 (1998), 77–106

Z. Safrai, The Missing Century: Palestine in the 5th Century—Growth

and Decline (Palestine Antiqua N.S. 9), Leuven 1998, (index)

M. Aviam, ESI 109 (1999), 7*–8*; id., Jews,

Pagans and Christians in the Galilee: 25 Years of Archaeological Excavations and Surveys—Hellenistic

to Byzantine Periods (Land of Galiliee 1), Rochester, NY 2004

Y. Stepansky, Cathedra 93 (1999), 180

B. Bagatti, Ancient Christian Villages of Galilee (SBF Collectio Minor 37), Jerusalem 2001, 190–195

J.

Magness, Cathedra 101 (2001), 204–205; id., Judaism in Late Antiquity III/4, Leiden 2001, 1–48, 79–91

Y.

Shivtiel, Eretz 93 (2004), 70–75.

Ambraseys (2009) states

Gush Halav, 30 km southeast of Tyre, shows archaeological evidence of destruction in the mid sixth century but this, like other archaeological datings, cannot be trusted.Russell (1985) reports

The 551 earthquake has been used to date the 6th century destruction of the synagogue at Gush Halav (Meyers, Strange, and Meyers 1979: 37; Meyers 1982: 121-22), although this correlation is suspect in light of the coin hoard sealed beneath the collapse rubble (see above). The "washed-in layer of yellowish soil" in which the hoard was found (Meyers, Strange, and Meyers 1979: 54) could represent post destruction deposition as a result of water percolation through the loose collapse rubble, rather than human deposition prior to the 551 earthquake.