Dor

Aerial Panorama of Tel Dor from the southeast

Aerial Panorama of Tel Dor from the southeastClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Drone photos taken by Jefferson Williams on 26 June 2023

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Dor | Hebrew | דוֹר |

| Tel Dor | Hebrew | דאר |

| Dora | Greek | Δῶρα |

| Tell el-Burj | Arabic | |

| Khirbet el-Burj | Arabic | |

| al-Tantura (adjacent) | Arabic | الطنطورة |

| Dir | Late Egyptian (Story of Wenamun) |

Tel Dor preserves a long sequence of occupation extending from the Middle Bronze Age through the Byzantine period. Archaeological remains include fortifications, harbor installations, industrial zones, and domestic architecture that together illustrate the site’s role as a major coastal hub. During the Canaanite and Phoenician periods, Dor served as a vital port and trading center linking inland routes with Mediterranean maritime networks. Under Hellenistic and Roman rule, the city flourished as a regional administrative and economic center, developing extensive harbor works and monumental public buildings. The Byzantine layers reveal continuity of settlement and adaptation to changing economic patterns, with evidence of churches, workshops, and harbor reuse. Remains from the Middle Bronze Age to the Byzantine period have been uncovered, reflecting more than two millennia of continuous urban and maritime life along the Carmel coast.

Biblical Dor, known as Δῶρα (Dora) in most Hellenistic sources, is identified with Khirbet el-Burj (map reference 142.224) on the Carmel coast, west of Kibbutz Nasholim, c. 21 km (14 mi.) south of Haifa. According to Greek and Latin sources, Dor was situated between the Carmel range and Straton's Tower (Caesarea). The Tabula Peutingeriana places Dor 8 miles north of Caesarea, while Eusebius gives the distance as 9 miles (Onom. 9, 78; 16, 136). On the basis of these two sources, the location of ancient Dor can almost certainly be established at the site of Khirbet el-Burj.

The city is apparently mentioned in an inscription dating to the reign of Ramses II (thirteenth century BCE) found in Nubia. It contains a list of cities on the Via Maris and on its western branch, between the Sharon and the Acco plains.

Dor is first mentioned in the Bible in connection with the Israelite conquest of Canaan. Joshua defeated the king of Dor (Jos. 12:23), one of the allies of Jabin, king of Hazor (Jos. 11:1-2). Canaanite Dor, located in the territory of the tribe of Manasseh, was not conquered by the Israelites until the reign of king David (tenth century BCE).

- Annotated Satellite Image

(google) of Tel Dor from biblewalks.com

- Annotated Aerial View of

Tel Dor and vicinity from Yasur-Landau et al. (2024)

Figure 2

Tel Dor, its bays and location of main features mentioned in this article:

- Tantura Lagoon

- South Bay

- Love Bay

- North Bay

- Tel Dor (note dashed line for the current boundaries of the Tel)

Main features:

- Area T, submerged Hellenistic fortification

- Tombolo, FDEM survey and possible tower

- Iron Age submerged fortification and mole

- Area D, Iron Age and Hellenistic structures

- Coastal Roman temples

- Slipways/shipsheds

- Love Bay underwater excavations

- Love Bay land excavations and Hellenistic structures

- North Bay Roman rectangular structure

- Area X, submerged Roman mole

- Area W, Roman and earlier anchorage

(prepared by M. Runjajić, A. Tamberino and A. Yasur-Landau)

Yasur-Landau et al. (2024) - Dor in Google Earth

- Dor on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated Aerial View of

Tel Dor and vicinity from Yasur-Landau et al. (2024)

Figure 2

Tel Dor, its bays and location of main features mentioned in this article:

- Tantura Lagoon

- South Bay

- Love Bay

- North Bay

- Tel Dor (note dashed line for the current boundaries of the Tel)

Main features:

- Area T, submerged Hellenistic fortification

- Tombolo, FDEM survey and possible tower

- Iron Age submerged fortification and mole

- Area D, Iron Age and Hellenistic structures

- Coastal Roman temples

- Slipways/shipsheds

- Love Bay underwater excavations

- Love Bay land excavations and Hellenistic structures

- North Bay Roman rectangular structure

- Area X, submerged Roman mole

- Area W, Roman and earlier anchorage

(prepared by M. Runjajić, A. Tamberino and A. Yasur-Landau)

Yasur-Landau et al. (2024)

- Plan of Tel Dor from

Stern et al (1993)

Tel Dor: plan of the mound and excavation areas.

Tel Dor: plan of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et al (1993) - Maritime installations near

the mound of Tel Dor from Stern et al (1993)

Tel Dor: map of maritime installations near the mound.

Tel Dor: map of maritime installations near the mound.

- Northern anchorage

- Roman theater

- Storerooms and quay

- Upper-level flushing channel

- Lower-level flushing channel

- Soaking installation for dying cloth with purple

- Central anchorage

- Slipways, Persian period

- Large retaining structure

- Tel Dor

- Acropolis

- Wave trap and rock-cut fish ponds

- LB and Iron I quays

- Southern harbor

Stern et al (1993) - Map of Tel Dor from

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - with excavation areas

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Map of Tel Dor showing Area G in relation to other excavation areas

(d09Z1-1001)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Map of Tel Dor from

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - The Roman Period

Fig. 1.2

Fig. 1.2

A reconstruction of the Roman street system at Dor, with Area G at the projected intersection of the north–south and east–west streets

(Shalev 2008: Fig. 24)

(d09Z1-1002)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

- Plan of Tel Dor from

Stern et al (1993)

Tel Dor: plan of the mound and excavation areas.

Tel Dor: plan of the mound and excavation areas.

Stern et al (1993) - Maritime installations near

the mound of Tel Dor from Stern et al (1993)

Tel Dor: map of maritime installations near the mound.

Tel Dor: map of maritime installations near the mound.

- Northern anchorage

- Roman theater

- Storerooms and quay

- Upper-level flushing channel

- Lower-level flushing channel

- Soaking installation for dying cloth with purple

- Central anchorage

- Slipways, Persian period

- Large retaining structure

- Tel Dor

- Acropolis

- Wave trap and rock-cut fish ponds

- LB and Iron I quays

- Southern harbor

Stern et al (1993) - Map of Tel Dor from

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - with excavation areas

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Map of Tel Dor showing Area G in relation to other excavation areas

(d09Z1-1001)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Map of Tel Dor from

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - The Roman Period

Fig. 1.2

Fig. 1.2

A reconstruction of the Roman street system at Dor, with Area G at the projected intersection of the north–south and east–west streets

(Shalev 2008: Fig. 24)

(d09Z1-1002)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

- Plan of Phase 7 in Area G

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Plan 7

Plan 7

Phase 7

(d10Z1-1118)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Plan of Phase 9 in Area G

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Plan 5

Plan 5

Phase 9

(d10Z1-1116)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Section of East Balk in

Area G from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Section 1

Section 1

East balk, AI/31–32

(d09Z3-1225)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.1 - Superposition of Phases 9–6

in Area G from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Superposition of Phases 9–6.

(d09Z3-1287)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 3.2 - Axonometric Superposition of

Phases 9-6 in Area G from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 3.2

Fig. 3.2

An axonometric superposition of Phases 6–9, showing the continuity of wall sequences in the Area G house.

(d10Z1-1011)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.56 - Phase 7 schematic plan

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.56

Fig. 2.56

Phase 7, schematic plan.

(d09Z3-1314)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.45 - Phase 9 schematic plan

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.45

Fig. 2.45

Phase 9, schematic plan

(d10Z1-1009)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.22 - Plan of the Phase 9 courtyard

house from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.22

Fig. 2.22

Plan of the Phase 9 house, with rooms and possible accessways.

(d09Z3-1447)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.30 - Phase 9-6 wall alignments

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.30

Fig. 2.30

- The conceptual grid along which most walls and spaces in the house are aligned

- Superposition of Phases 9-6 walls imposed on the grid

See Fig. 2.1 for key to phases.

(d09Z3-1297)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.54 - Artist's depiction of Phase

9 Courtyard House immediately before destruction from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.54

Fig. 2.54

An artist's view of Phase 9, showing a suggestion of the rooms' functions based on their contents when destroyed, looking north

Drawing: T. Kurz, based on an earlier drawing by V. Damov.

(d09Z3-1288))

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

- Plan of Phase 7 in Area G

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Plan 7

Plan 7

Phase 7

(d10Z1-1118)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Plan of Phase 9 in Area G

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Plan 5

Plan 5

Phase 9

(d10Z1-1116)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Section of East Balk in

Area G from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Section 1

Section 1

East balk, AI/31–32

(d09Z3-1225)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.1 - Superposition of Phases 9–6

in Area G from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Superposition of Phases 9–6.

(d09Z3-1287)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 3.2 - Axonometric Superposition of

Phases 9-6 in Area G from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 3.2

Fig. 3.2

An axonometric superposition of Phases 6–9, showing the continuity of wall sequences in the Area G house.

(d10Z1-1011)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.56 - Phase 7 schematic plan

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.56

Fig. 2.56

Phase 7, schematic plan.

(d09Z3-1314)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.45 - Phase 9 schematic plan

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.45

Fig. 2.45

Phase 9, schematic plan

(d10Z1-1009)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.22 - Plan of the Phase 9 courtyard

house from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.22

Fig. 2.22

Plan of the Phase 9 house, with rooms and possible accessways.

(d09Z3-1447)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.30 - Phase 9-6 wall alignments

from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.30

Fig. 2.30

- The conceptual grid along which most walls and spaces in the house are aligned

- Superposition of Phases 9-6 walls imposed on the grid

See Fig. 2.1 for key to phases.

(d09Z3-1297)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.54 - Artist's depiction of Phase

9 Courtyard House immediately before destruction from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.54

Fig. 2.54

An artist's view of Phase 9, showing a suggestion of the rooms' functions based on their contents when destroyed, looking north

Drawing: T. Kurz, based on an earlier drawing by V. Damov.

(d09Z3-1288))

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Figure 6a

Figure 6aThe locations of the cores [6a] and diagram of the chrono-stratigraphy [6b] of the coast of Dor, including Core D.

The OSL dates of the sediments in each core were used to reconstructs coastlines in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods (Figure 7). (Kadosh et al., 2004) and Cores D8, D11, D6, D12 and D4

(Shtienberg et al., 2021)

(prepared by G. Shtienberg, A. Tamberino and M. Runjajić)

Yasur-Landau et al. (2024)

Figure 6b

Figure 6bThe locations of the cores [6a] and diagram of the chrono-stratigraphy [6b] of the coast of Dor, including Core D.

The OSL dates of the sediments in each core were used to reconstructs coastlines in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods (Figure 7). (Kadosh et al., 2004) and Cores D8, D11, D6, D12 and D4

(Shtienberg et al., 2021)

(prepared by G. Shtienberg, A. Tamberino and M. Runjajić)

Yasur-Landau et al. (2024)

Figure 6b

Figure 6bThe locations of the cores [6a] and diagram of the chrono-stratigraphy [6b] of the coast of Dor, including Core D.

The OSL dates of the sediments in each core were used to reconstructs coastlines in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods (Figure 7). (Kadosh et al., 2004) and Cores D8, D11, D6, D12 and D4

(Shtienberg et al., 2021)

(prepared by G. Shtienberg, A. Tamberino and M. Runjajić)

Yasur-Landau et al. (2024)

Figure 6b

Figure 6bThe locations of the cores [6a] and diagram of the chrono-stratigraphy [6b] of the coast of Dor, including Core D.

The OSL dates of the sediments in each core were used to reconstructs coastlines in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods (Figure 7). (Kadosh et al., 2004) and Cores D8, D11, D6, D12 and D4

(Shtienberg et al., 2021)

(prepared by G. Shtienberg, A. Tamberino and M. Runjajić)

Yasur-Landau et al. (2024)

- Fig. 1 Geological sketch of

the eastern Mediterranean from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 1

Geological sketch of the eastern Mediterranean modified after natural earth, showing

- main near-shore sediment transport mechanism (black arrows)

- selected thrusts (CA–Cypriot Arc)

- major fault lines

- CF- Carmel fault

- DSF- Dead Sea Fault system

- SF- Seraghaya fault

- MF-Missyaf fault

- YF-Yammaounch fault

- [3,8]

- submarine landslides

- tsunami deposits

- geomorphological tsunami features

- documented tsunami events

- (Modified from [9])

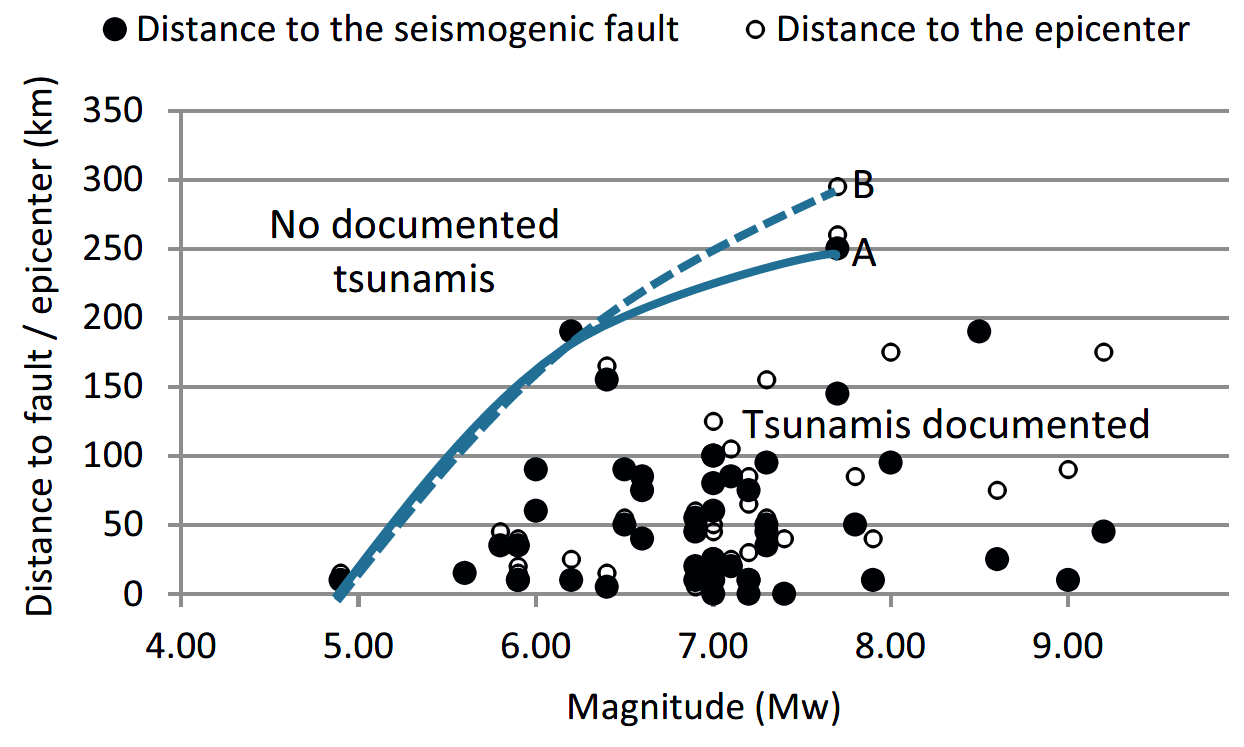

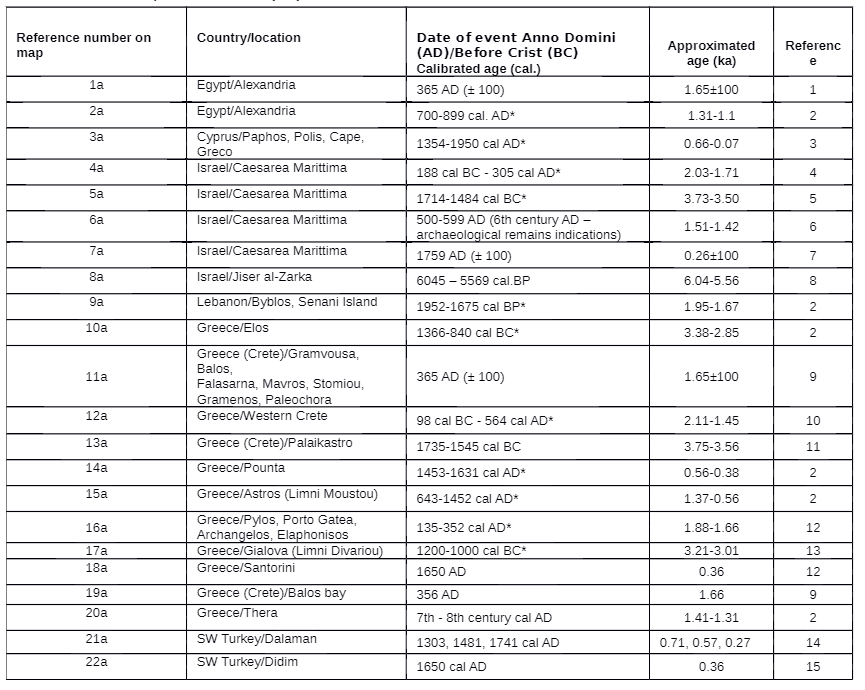

NAME COMPILATION OF THE SITES PRESENTED IN THE FIGURE

Previously dated tsunami deposits

- 1a -2a (Alexandria)

- 3a (Paphos, Polis, Cape, Greco)

- 4a -8a (Caesarea Marittima, Jiser al-Zarka)

- 9a (Byblos, Senani Island)

- 10a (Elos)

- 11a (Gramvousa, Balos, Falasarna, Mavros, Stomiou, Gramenos, Paleochora)

- 12a (Western Crete)

- 13a (Palaikastro)

- 14a (Pounta)

- 15a (Limni Moustou)

- 16a (Pylos, Porto Gatea, Archangelos, Elaphonisos)

- 17a (Limni Divariou)

- 18a (Santorini)

- 19a (Balos bay)

- 20a (Thera)

- 21a (Dalaman)

- 22a (Didim) for the previously dated tsunami deposits

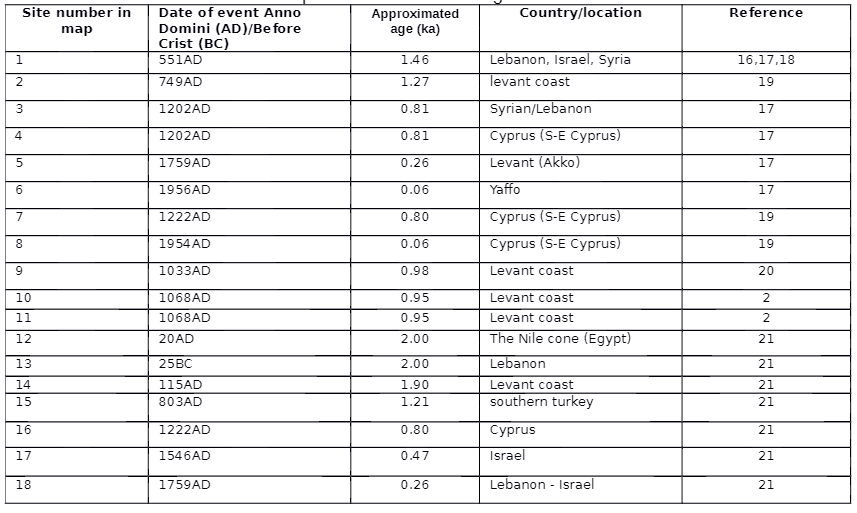

Previously dated tsunami events

- 1 (Lebanon, Israel, Syria)

- 2 (levant coast)

- 3 (Paphos, Polis, Cape, Greco)

- 4 (S-E Cyprus)

- 5 (Akko)

- 6 (Yaffo)

- 7–8 (S-E Cyprus)

- 9–11 (Levant coast)

- 12 (The Nile cone)

- 13 (Lebanon)

- 14 (Levant coast)

- 15 (southern turkey)

- 16 (Cyprus)

- 17 (Israel)

- 18 (Lebanon–Israel

Further details regarding the tsunami data are discussed in S1 and S2 Tables.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Location Maps from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 2

Location maps

(a) Israel’s Carmel coastal plain: surface lithologies, streams, shelf bathymetry and elevations (Republished from [14] under a CC BY license, with permission from [the geological Survey of Israel], original copyright [1994]). The red and green triangles indicate location of Neolithic habitations based on Galili et al. [15] while the red square annotates the location of the study area. The numbered red circles represent previously studied zones in which the stratigraphic sequence was investigated and is described in the following papers according to their numbering: (1) Kadosh et al. [16]; (2) Sivan et al. [16]. The numbered hexagons annotate prehistoric sites

- Nahal Oren (Natufian period)

- Elwad (Natufian period)

- Kebara (Natufian period)

- Tel Mevorakh (PPNB period)

- Aviel (late PPNB-PPNC period)

The projected coastline during the tsunami at ca 9,910–9,290 ya ca. 9.91–9.29 ka, is presumed to have been located between at about 40 to 16 m below present day sea-level and 3.5–1.5 km west of the current shoreline.

(b) The coast of Dor with existing cores and new drilling locations as well as elevations.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Neolithic remains and construction

uncovered underwater from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Neolithic remains and construction uncovered underwater in the south bay of Dor during joint excavations conducted by the Department of Maritime Civilizations at the University of Haifa and Scripps Center of Marine Archeology at the University of California San Diego

- location of the findings marked by red polygons—each letter is attributed to the finds presented in the next parts of the figure

- Pre pottery Neolithic–Early Pottery Neolithic arrowhead

- Neolithic architecture which includes curved installations as well as wall foundations

- Pottery Neolithic ceramic base excavated in 2019 by the Department of Maritime Civilizations, University of Haifa

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Longshore Current on the

Israeli Coast from Morhange et. al. (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location map. Akko (Northern Israel) in the Eastern Mediterranean basin.

Morhange et. al. (2016)

- Fig. 2.58 - Skeleton of a

woman in Room 9816 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.58

Fig. 2.58

The skeleton of a woman in Room 9816, looking south, partly covered by fallen stones.

(p08Z3-1013)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 5.2 - "Doreen" the

skeleton in Phase 7 from Nur and Burgess (2008)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

“Doreen,” a probable earthquake victim at Dor in Israel, was crushed by a fallen wall .

(after Andrew Stewart/Biblical Archaeology Review, 1993)

Nur and Burgess (2008) - Fig. 10.10 - Wider shot

of the skeleton with remaining stone collapse on skull from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 10.10

Fig. 10.10

The skeleton against W9841 after partial clearance, looking south. Note remaining stone collapse above skull.

(p08Z3-1248)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 10.11 - Almost

completely exposed skeleton from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 10.11

Fig. 10.11

The almost completely exposed skeleton, looking west.

(p08Z3-1249)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.59 - Smashed

pottery and rubble collapse in Room 9816 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.59

Fig. 2.59

Smashed pottery and rubble collapse on F9816, looking north

(photograph courtesy of Andrew Stewart)

(p10Z3-0059)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 10.6 - Stone

Collapse which covered the skeleton along with smashed jars from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 10.6

Fig. 10.6

Corner of W9211 and W9684, looking north. Northern thicker part of the stone collapse (L9816) that covered the skeleton and the smashed jars (some of which are showing below the meter stick).

(p08Z3-1250)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 10.7 - Pottery

found in wall collapse debris, suggesting material stored on a shelf from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 10.7

Fig. 10.7

Pottery found in wall collapse debris on F9816, suggesting material stored on a shelf

(photograph courtesy of Andrew Stewart)

(p10Z3-0078)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

- Fig. 2.58 - Skeleton of a

woman in Room 9816 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.58

Fig. 2.58

The skeleton of a woman in Room 9816, looking south, partly covered by fallen stones.

(p08Z3-1013)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 5.2 - "Doreen" the

skeleton in Phase 7 from Nur and Burgess (2008)

Fig. 5.2

Fig. 5.2

“Doreen,” a probable earthquake victim at Dor in Israel, was crushed by a fallen wall .

(after Andrew Stewart/Biblical Archaeology Review, 1993)

Nur and Burgess (2008) - Fig. 10.10 - Wider shot

of the skeleton with remaining stone collapse on skull from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 10.10

Fig. 10.10

The skeleton against W9841 after partial clearance, looking south. Note remaining stone collapse above skull.

(p08Z3-1248)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 10.11 - Almost

completely exposed skeleton from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 10.11

Fig. 10.11

The almost completely exposed skeleton, looking west.

(p08Z3-1249)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.59 - Smashed

pottery and rubble collapse in Room 9816 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.59

Fig. 2.59

Smashed pottery and rubble collapse on F9816, looking north

(photograph courtesy of Andrew Stewart)

(p10Z3-0059)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 10.6 - Stone

Collapse which covered the skeleton along with smashed jars from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 10.6

Fig. 10.6

Corner of W9211 and W9684, looking north. Northern thicker part of the stone collapse (L9816) that covered the skeleton and the smashed jars (some of which are showing below the meter stick).

(p08Z3-1250)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 10.7 - Pottery

found in wall collapse debris, suggesting material stored on a shelf from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 10.7

Fig. 10.7

Pottery found in wall collapse debris on F9816, suggesting material stored on a shelf

(photograph courtesy of Andrew Stewart)

(p10Z3-0078)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

- Fig. 2.12 - Phase 9

destruction debris in Room 18033 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.12

Fig. 2.12

Section through the Phase 9 destruction debris in Room 18033, looking west. Note in situ jars on floor, with mudbrick and stone collapse on top and burnt beams and roofing material above

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p09Z3-6011)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.13 - Closeup

on burnt roof material in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.13

Fig. 2.13

Close-up of roof collapse seen in section in Fig. 2.12. Above the beams: burnt organic layer with packing of mudbrick material above

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p09Z3-6014)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.14 - Closeup

on collapsed roof material in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.14

Fig. 2.14

Close-up of roof collapse in western balk in Room 18033, opposite the roofing material in Figs. 2.12 and 2.13. Note the two cross-members under the brush and a thin white organic layer (mat? fronds?) draping across them

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p08Z3-1460)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.26 - Phase 9

collapse debris from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.26

Fig. 2.26

Collapsed debris tumbled against installation 9982 (on right), looking north. Center and left: fallen stones and mudbrick below three layers of fallen ceiling material (=Fig. 9.39).

(p05Z3-0610)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.46 - Phase 9

destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.46

Fig. 2.46

Area G destruction as first encountered in 1992, looking west. Center: narrow partition belonging to southeastern edge of trough-installation 9982, not yet fully exposed (=Fig. 9.41)

(p08Z3-1004)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.47 - Phase 9

destruction layer as seen in a balk from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.47

Fig. 2.47

View of eastern balk, AI/32, showing the depth of Phase 9 destruction debris; the arrow marks the top of the destruction material. Square supervisor Robyn Talman standing on courtyard floor

(photograph courtesy of Andrew Stewart)

(p08Z3-1440)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.48 - Broken

Pottery in Phase 9 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.48

Fig. 2.48

In situ pottery near the trough-installation, looking west. Note basalt bowl, upper grinding stone (above meter stick) and "stone tripod" at bottom (=Fig. 9.47).

(p09z3-6007)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.49 - Broken

Pottery on the floor of Room 18033 in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.49

Fig. 2.49

Jars in destruction on Phase 9 floor in Room 18033, looking west (=Fig. 8.29).

(p08Z3-1459)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.50 - Phase 9

destruction layer in Room 18239 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.50

Fig. 2.50

F18239 under excavation, looking south. Note slope of surface, with in situ pottery and deer antler.

(p08Z3-1007)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 3.16 - Phase 9

destruction east of Wall 18048 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 3.16

Fig. 3.16

W9140(S) above W18048 (AJ/32), looking north. Note destruction debris with fallen bricks and roofing material in the probe east of W18048

(photo courtesy of Andrew Stewart).

(p10Z3-0017)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 15.18 - Annotated

balk showing section of Phase 9 mudbrick collapse from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 15.180

Fig. 15.180

The northern balk of AJ–AK/32 under W9066, after end of excavation (2004).

(p05Z3-0727)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

- Fig. 2.12 - Phase 9

destruction debris in Room 18033 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.12

Fig. 2.12

Section through the Phase 9 destruction debris in Room 18033, looking west. Note in situ jars on floor, with mudbrick and stone collapse on top and burnt beams and roofing material above

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p09Z3-6011)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.13 - Closeup

on burnt roof material in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.13

Fig. 2.13

Close-up of roof collapse seen in section in Fig. 2.12. Above the beams: burnt organic layer with packing of mudbrick material above

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p09Z3-6014)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.14 - Closeup

on collapsed roof material in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.14

Fig. 2.14

Close-up of roof collapse in western balk in Room 18033, opposite the roofing material in Figs. 2.12 and 2.13. Note the two cross-members under the brush and a thin white organic layer (mat? fronds?) draping across them

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p08Z3-1460)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.26 - Phase 9

collapse debris from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.26

Fig. 2.26

Collapsed debris tumbled against installation 9982 (on right), looking north. Center and left: fallen stones and mudbrick below three layers of fallen ceiling material (=Fig. 9.39).

(p05Z3-0610)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.46 - Phase 9

destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.46

Fig. 2.46

Area G destruction as first encountered in 1992, looking west. Center: narrow partition belonging to southeastern edge of trough-installation 9982, not yet fully exposed (=Fig. 9.41)

(p08Z3-1004)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.47 - Phase 9

destruction layer as seen in a balk from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.47

Fig. 2.47

View of eastern balk, AI/32, showing the depth of Phase 9 destruction debris; the arrow marks the top of the destruction material. Square supervisor Robyn Talman standing on courtyard floor

(photograph courtesy of Andrew Stewart)

(p08Z3-1440)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.48 - Broken

Pottery in Phase 9 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.48

Fig. 2.48

In situ pottery near the trough-installation, looking west. Note basalt bowl, upper grinding stone (above meter stick) and "stone tripod" at bottom (=Fig. 9.47).

(p09z3-6007)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.49 - Broken

Pottery on the floor of Room 18033 in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.49

Fig. 2.49

Jars in destruction on Phase 9 floor in Room 18033, looking west (=Fig. 8.29).

(p08Z3-1459)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.50 - Phase 9

destruction layer in Room 18239 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.50

Fig. 2.50

F18239 under excavation, looking south. Note slope of surface, with in situ pottery and deer antler.

(p08Z3-1007)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 3.16 - Phase 9

destruction east of Wall 18048 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 3.16

Fig. 3.16

W9140(S) above W18048 (AJ/32), looking north. Note destruction debris with fallen bricks and roofing material in the probe east of W18048

(photo courtesy of Andrew Stewart).

(p10Z3-0017)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 15.18 - Annotated

balk showing section of Phase 9 mudbrick collapse from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 15.180

Fig. 15.180

The northern balk of AJ–AK/32 under W9066, after end of excavation (2004).

(p05Z3-0727)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

- Fig. 3 Chronostratigraphic cross

sections in the coastal area from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 3

Core analysis and chronostratigraphic correlation

(a) Borehole D4 with core scan

- lithological unit name

- sedimentological and petrophysical results

- lithological identification with OSL sampling location

- OSL ages presented before 2018

- corresponding sea level [23,24]

- approximate shoreline location

(b) Chronostratigraphic cross sections in the coastal area of Dor based on sedimentological and OSL data obtained in the present study, presented for thousand years ago (ka, marked with a red star) as well as Shtienberg et al. (submitted; blue star) correlated with the lithological results, and 14C calibrated dates (cal. ka; green circles) published in Kadosh et al. [16]. A closeup of units F2, F3 and F4 in core D6 with its lithological unit name and accumulative grain texture results. The modern topography portrayed in the cross sections was extracted from the DEM presented in Fig 2B. See Fig 2B for cross section location.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. 5 Age constraint for the

tsunami deposit from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Age constraint for the tsunami deposit (Unit F3) based on the ages and stratigraphic position of the lower wetland deposit (Unit F2) the abruptly overlying sandy tsunami deposit (Unit F3) and upper wetland deposit (Unit F4) that have been correlated between cores in the study area (Fig 3). The age constraint for the tsunami deposit (Unit F3) is based on the overlapping ages and uncertainties (highlighted by dashed red line) between the Unit F2 wetland deposit (green circle, core D6) the overlying Unit F3 tsunami deposit (yellow circle, core D4) and superimposing Unit F4 wetland deposit (blue circle, core D4).

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S1 Borehole D4 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S1

Fig. S1

Borehole D4 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

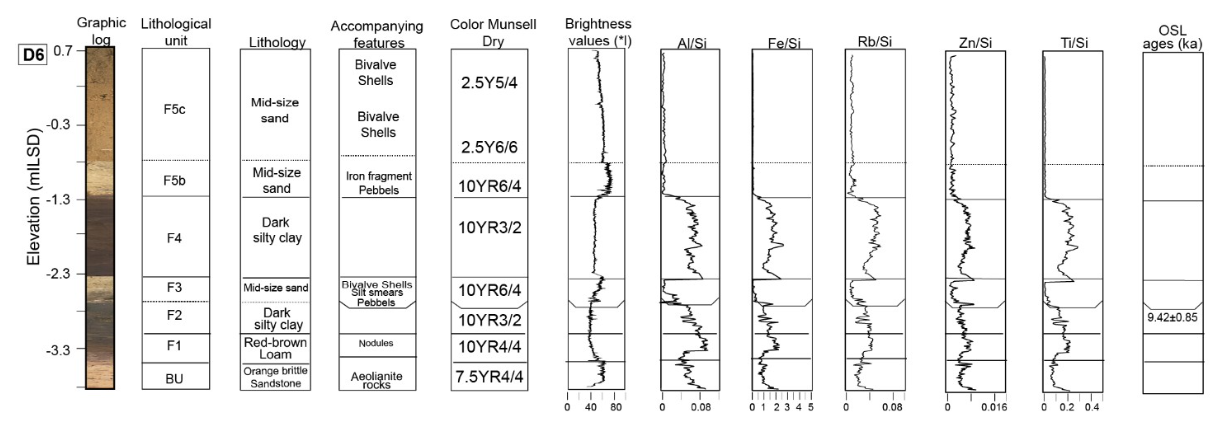

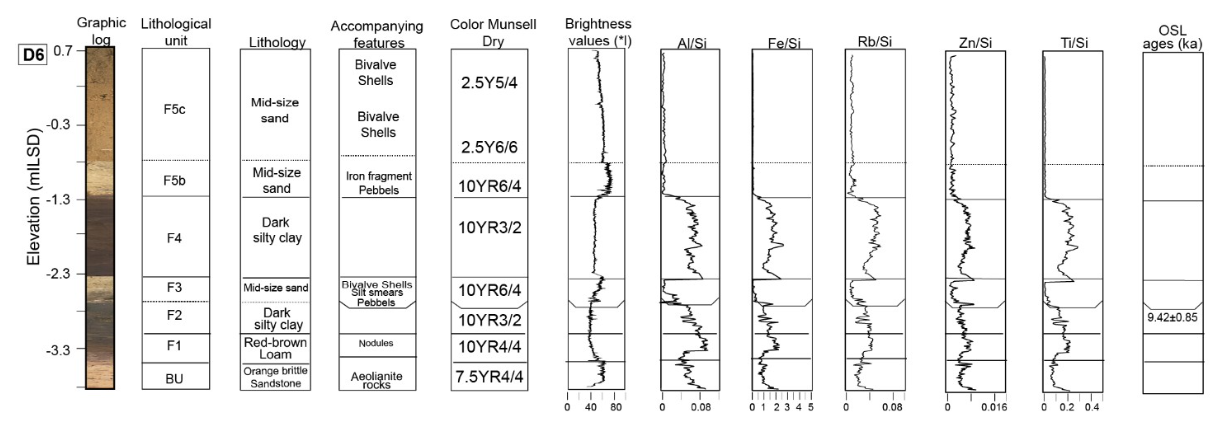

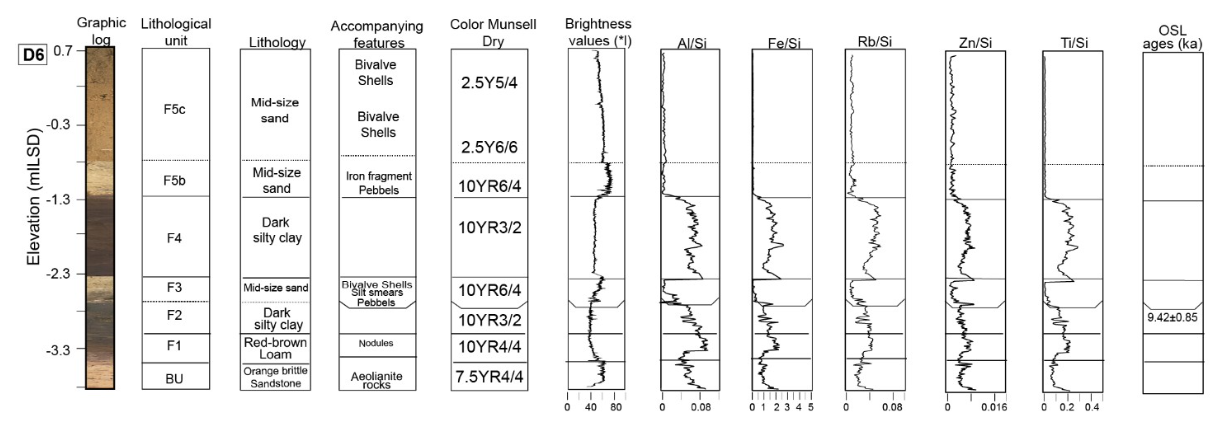

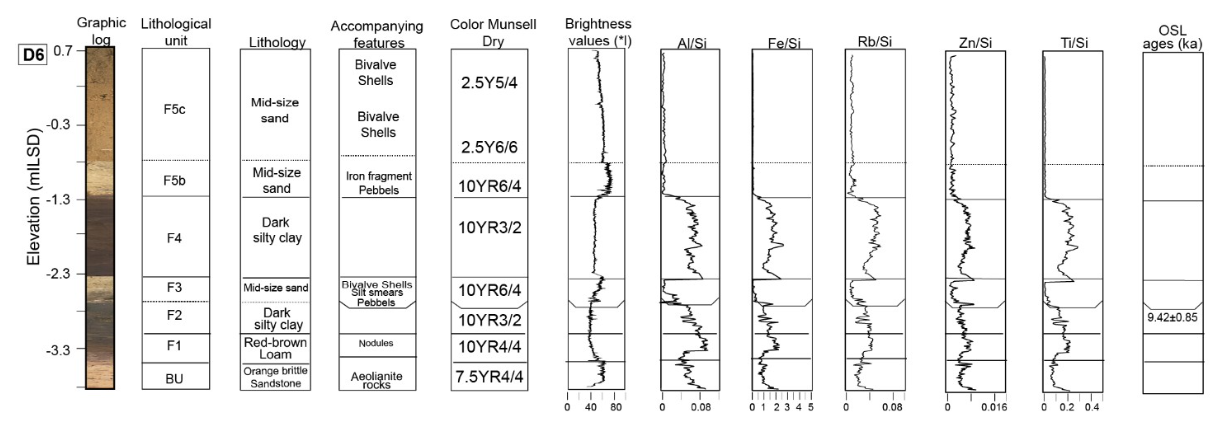

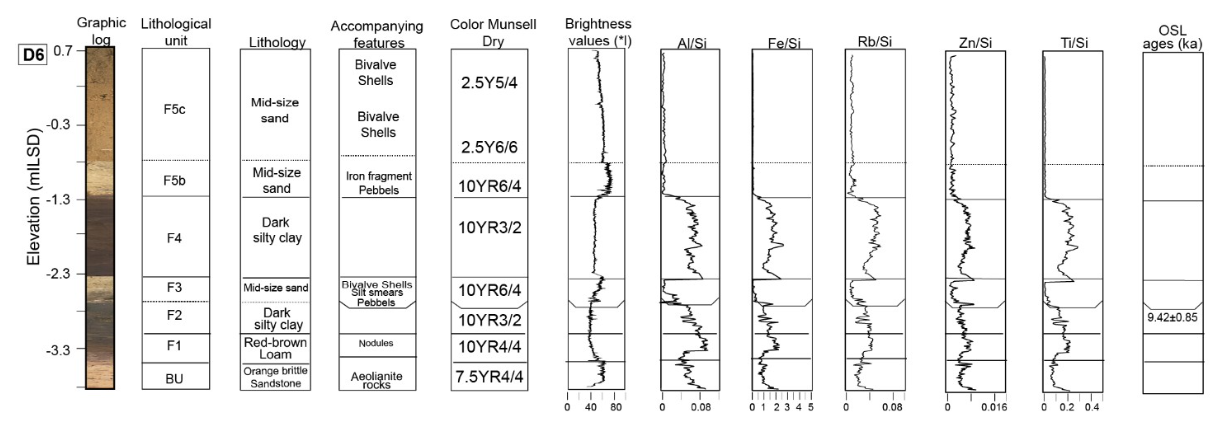

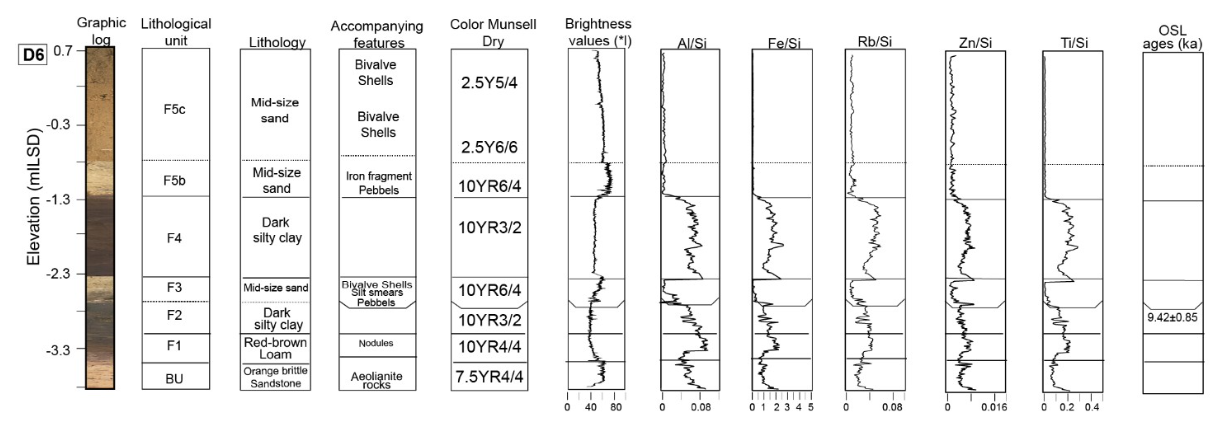

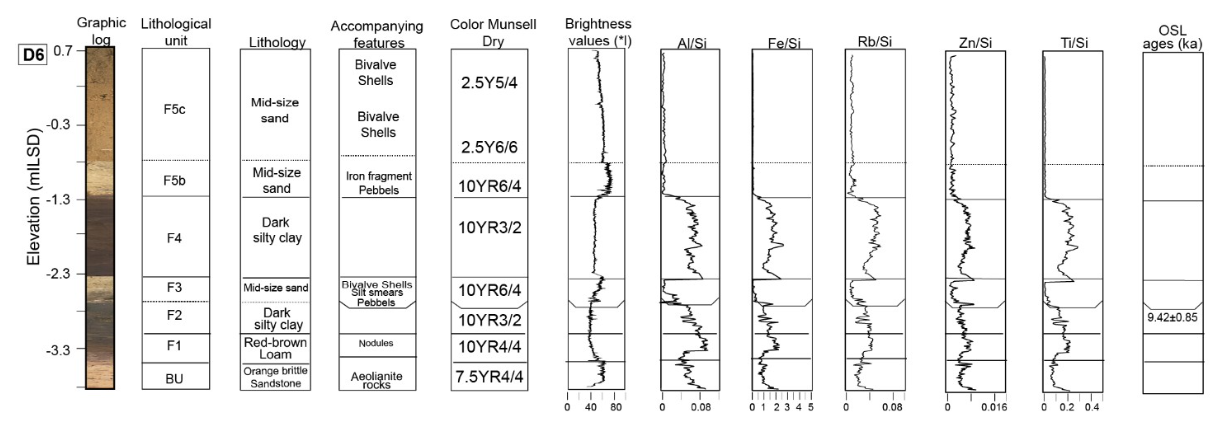

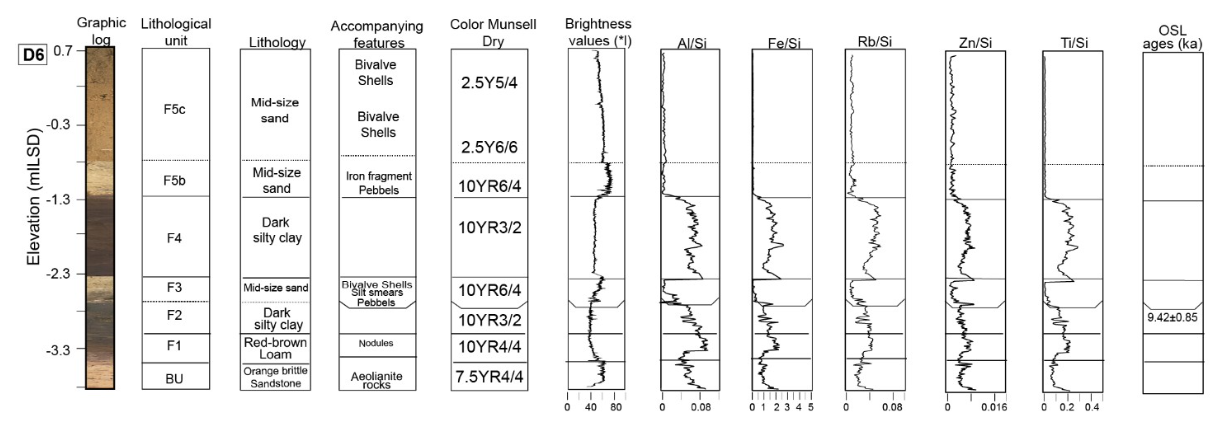

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S2 Borehole D6 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S2

Fig. S2

Borehole D6 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S3 Borehole D12 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S3

Fig. S3

Borehole D12 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S4 Equivalent Dose

distributions for OSL samples from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S4

Fig. S4

Equivalent Dose distributions for OSL samples

- CAM = Central Age Model

- OD = Over-dispersion

Shtienberg et al (2020)

- Fig. 3 Chronostratigraphic cross

sections in the coastal area from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 3

Core analysis and chronostratigraphic correlation

(a) Borehole D4 with core scan

- lithological unit name

- sedimentological and petrophysical results

- lithological identification with OSL sampling location

- OSL ages presented before 2018

- corresponding sea level [23,24]

- approximate shoreline location

(b) Chronostratigraphic cross sections in the coastal area of Dor based on sedimentological and OSL data obtained in the present study, presented for thousand years ago (ka, marked with a red star) as well as Shtienberg et al. (submitted; blue star) correlated with the lithological results, and 14C calibrated dates (cal. ka; green circles) published in Kadosh et al. [16]. A closeup of units F2, F3 and F4 in core D6 with its lithological unit name and accumulative grain texture results. The modern topography portrayed in the cross sections was extracted from the DEM presented in Fig 2B. See Fig 2B for cross section location.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. 5 Age constraint for the

tsunami deposit from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Age constraint for the tsunami deposit (Unit F3) based on the ages and stratigraphic position of the lower wetland deposit (Unit F2) the abruptly overlying sandy tsunami deposit (Unit F3) and upper wetland deposit (Unit F4) that have been correlated between cores in the study area (Fig 3). The age constraint for the tsunami deposit (Unit F3) is based on the overlapping ages and uncertainties (highlighted by dashed red line) between the Unit F2 wetland deposit (green circle, core D6) the overlying Unit F3 tsunami deposit (yellow circle, core D4) and superimposing Unit F4 wetland deposit (blue circle, core D4).

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S1 Borehole D4 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S1

Fig. S1

Borehole D4 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S2 Borehole D6 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S2

Fig. S2

Borehole D6 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S3 Borehole D12 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S3

Fig. S3

Borehole D12 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S4 Equivalent Dose

distributions for OSL samples from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S4

Fig. S4

Equivalent Dose distributions for OSL samples

- CAM = Central Age Model

- OD = Over-dispersion

Shtienberg et al (2020)

- Fig. 1 Geological sketch of

the eastern Mediterranean from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 1

Geological sketch of the eastern Mediterranean modified after natural earth, showing

- main near-shore sediment transport mechanism (black arrows)

- selected thrusts (CA–Cypriot Arc)

- major fault lines

- CF- Carmel fault

- DSF- Dead Sea Fault system

- SF- Seraghaya fault

- MF-Missyaf fault

- YF-Yammaounch fault

- [3,8]

- submarine landslides

- tsunami deposits

- geomorphological tsunami features

- documented tsunami events

- (Modified from [9])

NAME COMPILATION OF THE SITES PRESENTED IN THE FIGURE

Previously dated tsunami deposits

- 1a -2a (Alexandria)

- 3a (Paphos, Polis, Cape, Greco)

- 4a -8a (Caesarea Marittima, Jiser al-Zarka)

- 9a (Byblos, Senani Island)

- 10a (Elos)

- 11a (Gramvousa, Balos, Falasarna, Mavros, Stomiou, Gramenos, Paleochora)

- 12a (Western Crete)

- 13a (Palaikastro)

- 14a (Pounta)

- 15a (Limni Moustou)

- 16a (Pylos, Porto Gatea, Archangelos, Elaphonisos)

- 17a (Limni Divariou)

- 18a (Santorini)

- 19a (Balos bay)

- 20a (Thera)

- 21a (Dalaman)

- 22a (Didim) for the previously dated tsunami deposits

Previously dated tsunami events

- 1 (Lebanon, Israel, Syria)

- 2 (levant coast)

- 3 (Paphos, Polis, Cape, Greco)

- 4 (S-E Cyprus)

- 5 (Akko)

- 6 (Yaffo)

- 7–8 (S-E Cyprus)

- 9–11 (Levant coast)

- 12 (The Nile cone)

- 13 (Lebanon)

- 14 (Levant coast)

- 15 (southern turkey)

- 16 (Cyprus)

- 17 (Israel)

- 18 (Lebanon–Israel

Further details regarding the tsunami data are discussed in S1 and S2 Tables.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Location Maps from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 2

Location maps

(a) Israel’s Carmel coastal plain: surface lithologies, streams, shelf bathymetry and elevations (Republished from [14] under a CC BY license, with permission from [the geological Survey of Israel], original copyright [1994]). The red and green triangles indicate location of Neolithic habitations based on Galili et al. [15] while the red square annotates the location of the study area. The numbered red circles represent previously studied zones in which the stratigraphic sequence was investigated and is described in the following papers according to their numbering: (1) Kadosh et al. [16]; (2) Sivan et al. [16]. The numbered hexagons annotate prehistoric sites

- Nahal Oren (Natufian period)

- Elwad (Natufian period)

- Kebara (Natufian period)

- Tel Mevorakh (PPNB period)

- Aviel (late PPNB-PPNC period)

The projected coastline during the tsunami at ca 9,910–9,290 ya ca. 9.91–9.29 ka, is presumed to have been located between at about 40 to 16 m below present day sea-level and 3.5–1.5 km west of the current shoreline.

(b) The coast of Dor with existing cores and new drilling locations as well as elevations.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Neolithic remains and construction

uncovered underwater from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Neolithic remains and construction uncovered underwater in the south bay of Dor during joint excavations conducted by the Department of Maritime Civilizations at the University of Haifa and Scripps Center of Marine Archeology at the University of California San Diego

- location of the findings marked by red polygons—each letter is attributed to the finds presented in the next parts of the figure

- Pre pottery Neolithic–Early Pottery Neolithic arrowhead

- Neolithic architecture which includes curved installations as well as wall foundations

- Pottery Neolithic ceramic base excavated in 2019 by the Department of Maritime Civilizations, University of Haifa

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Longshore Current on the

Israeli Coast from Morhange et. al. (2016)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Location map. Akko (Northern Israel) in the Eastern Mediterranean basin.

Morhange et. al. (2016)

- Fig. 3 Chronostratigraphic cross

sections in the coastal area from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 3

Core analysis and chronostratigraphic correlation

(a) Borehole D4 with core scan

- lithological unit name

- sedimentological and petrophysical results

- lithological identification with OSL sampling location

- OSL ages presented before 2018

- corresponding sea level [23,24]

- approximate shoreline location

(b) Chronostratigraphic cross sections in the coastal area of Dor based on sedimentological and OSL data obtained in the present study, presented for thousand years ago (ka, marked with a red star) as well as Shtienberg et al. (submitted; blue star) correlated with the lithological results, and 14C calibrated dates (cal. ka; green circles) published in Kadosh et al. [16]. A closeup of units F2, F3 and F4 in core D6 with its lithological unit name and accumulative grain texture results. The modern topography portrayed in the cross sections was extracted from the DEM presented in Fig 2B. See Fig 2B for cross section location.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. 5 Age constraint for the

tsunami deposit from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Age constraint for the tsunami deposit (Unit F3) based on the ages and stratigraphic position of the lower wetland deposit (Unit F2) the abruptly overlying sandy tsunami deposit (Unit F3) and upper wetland deposit (Unit F4) that have been correlated between cores in the study area (Fig 3). The age constraint for the tsunami deposit (Unit F3) is based on the overlapping ages and uncertainties (highlighted by dashed red line) between the Unit F2 wetland deposit (green circle, core D6) the overlying Unit F3 tsunami deposit (yellow circle, core D4) and superimposing Unit F4 wetland deposit (blue circle, core D4).

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S1 Borehole D4 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S1

Fig. S1

Borehole D4 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S2 Borehole D6 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S2

Fig. S2

Borehole D6 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S3 Borehole D12 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S3

Fig. S3

Borehole D12 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S4 Equivalent Dose

distributions for OSL samples from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S4

Fig. S4

Equivalent Dose distributions for OSL samples

- CAM = Central Age Model

- OD = Over-dispersion

Shtienberg et al (2020)

- Fig. 3 Chronostratigraphic cross

sections in the coastal area from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 3

Core analysis and chronostratigraphic correlation

(a) Borehole D4 with core scan

- lithological unit name

- sedimentological and petrophysical results

- lithological identification with OSL sampling location

- OSL ages presented before 2018

- corresponding sea level [23,24]

- approximate shoreline location

(b) Chronostratigraphic cross sections in the coastal area of Dor based on sedimentological and OSL data obtained in the present study, presented for thousand years ago (ka, marked with a red star) as well as Shtienberg et al. (submitted; blue star) correlated with the lithological results, and 14C calibrated dates (cal. ka; green circles) published in Kadosh et al. [16]. A closeup of units F2, F3 and F4 in core D6 with its lithological unit name and accumulative grain texture results. The modern topography portrayed in the cross sections was extracted from the DEM presented in Fig 2B. See Fig 2B for cross section location.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. 5 Age constraint for the

tsunami deposit from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Age constraint for the tsunami deposit (Unit F3) based on the ages and stratigraphic position of the lower wetland deposit (Unit F2) the abruptly overlying sandy tsunami deposit (Unit F3) and upper wetland deposit (Unit F4) that have been correlated between cores in the study area (Fig 3). The age constraint for the tsunami deposit (Unit F3) is based on the overlapping ages and uncertainties (highlighted by dashed red line) between the Unit F2 wetland deposit (green circle, core D6) the overlying Unit F3 tsunami deposit (yellow circle, core D4) and superimposing Unit F4 wetland deposit (blue circle, core D4).

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S1 Borehole D4 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S1

Fig. S1

Borehole D4 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S2 Borehole D6 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S2

Fig. S2

Borehole D6 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S3 Borehole D12 from

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S3

Fig. S3

Borehole D12 (location is displayed in Fig. 2b) with

- lithological classification

- description

- accompanying features

- brightness differences

- relative elemental concentration variations

- OSL data

obtained in the present study.

Shtienberg et al (2020) - Fig. S4 Equivalent Dose

distributions for OSL samples from Shtienberg et al (2020)

Fig. S4

Fig. S4

Equivalent Dose distributions for OSL samples

- CAM = Central Age Model

- OD = Over-dispersion

Shtienberg et al (2020)

Shtienberg et al. (2020) identified a tsunamogenic deposit which they dated to

9.91 to 9.29 ka. They estimated that the tsunami had a run-up of at

least ~16 m and traveled between 3.5 to 1.5 km inland from the palaeo-coastline.

They

suggested a subsea landslide in the "Dor complex" (16 km. west of Dor) as a likely cause. OSL dating was

used to date their cores.

Shtienberg et al. (2020:8-9) discussed the dating and interpretation of the presumed tsunamogenic deposit (Unit F3)

The age of the abrupt marine sand interbed (Unit F3) including its uncertainties (10.19 ± 0.90 ka; Table 1) and age constraint from the underlying wetland surface (unit F2; 9.42 ± 0.85 ka; Fig 3B; Table 1) as well as overlying wetland bottom (unit F4; 9.15 ± 0.78 ka) indicates that deposition occurred between 9.91 to 9.29 ka (see Fig 5 for further details) when global sea-level was ca. 40–16 m below present sea level (Fig 3A; ref. [24–26]). The early Holocene shoreline at this time was plotted against the offshore bathymetric chart after consideration of the Holocene shelf sediment thickness [26] and indicates its location was ~ 3.5–1.5 km seaward from the current shoreline (Figs 2A and 3A). In order to deposit marine shells into the contemporaneous fresh to brackish wetland at Dor, the wave front must have traveled a minimum distance of 1.5 km with a coastal run-up of at least ~16 m. The run-up could have been much larger as the oldest permissible dates on the deposit imply a travel distance of 3.5 km and a run-up of as much as 40 m. The possibility of an extreme winter storm can be ruled out because even the strongest storms only produce surge up to a few hundred meters inland and yield a run-up of only tens of centimeters to a few meters at most [13].

In addition to the estimated run-up, the sand layer (Unit F3) is composed of a poorly sorted sand with marine shells and the rip-up clasts of the underlying wetland deposits, all of which are indicative of a tsunami. Previously identified tsunamis in the eastern Mediterranean from the past ca. 6,000 years (Fig 1, S1 and S2 Tables and ref. [7,10,27]) have had smaller run-up distances as the palaeo event reported here, consisting of inland dispersion limited to only 300 meters compared to the present shoreline. Thus, the Dor event, was generated by a much stronger mechanism than previously documented events in the Eastern Mediterranean.

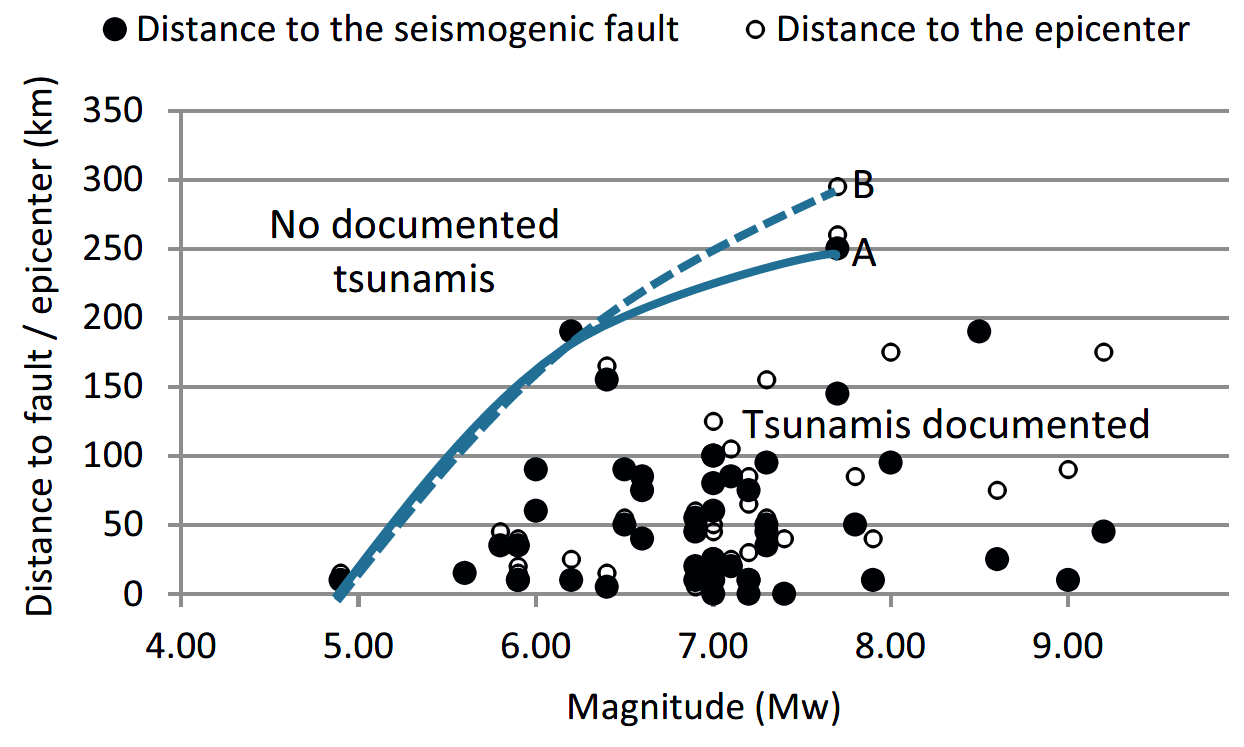

Local tsunami-generating mechanisms in the Levant basin include earthquakes associated with onshore and offshore faulting as well as submarine landslides, linked to over steepened slopes or earthquake-induced failure. The main source of earthquakes in Israel is the Dead Sea Fault system (DSF; Fig 1) that crosses the Middle East from south to north parallel to the present Levant coast [28]. Although situated onshore, this large seismogenic system is located close to the coastal zone and can generate strong ground motions that could influence failures along the continental margin. The Carmel fault (CF; Fig 1) branches off the Dead Sea Fault in a NW–SE direction extending onto the continental shelf of the Mediterranean Sea. This fault line is believed to be capable of producing earthquakes up to a magnitude (M) of 6.5 [29]. Salamon and Manna [30] empirically constrain the relationship between the magnitude of inland and offshore earthquakes that generate tsunamigenic submarine landslides and the maximal distance of the tsunami source from the epicenter of the seismogenic fault. They estimate the threshold magnitude for tsunamigenic earthquakes to be approximately M 6. Notably, an earthquake contemporary (ca. 10 ka) with the Dor paleo-tsunami has been dated using damaged speleothems from a cave in the nearby Carmel ridge [31]. Given age uncertainty of the event, this earthquake could have triggered an underwater landslide that produced the tsunami recorded here.

Table 2.2 (aka Chart 2)

Table 2.2 (aka Chart 2)Area G Bronze and Iron Ages phases and horizons by context

- Small Roman numerals (i, ii, etc.): local stages within unit

- Thick separator between stages: evidence for destruction or trauma

- Asterisk (*): context fully illustrated (numbers above are plate nos. in Volume IIC)

- Arrows (↔): placement of the stage separator (or of the entire stage) is arbitrary; it might be moved right (later) or left (earlier)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Table 2.1 (aka Chart 1)

Table 2.1 (aka Chart 1)Comparative stratigraphy and chronology of Areas G, D2, D5 and B1 and correlation to Megiddo strata

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

| Phase | Horizon | Nature of Occupation |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Roman | Plaza, porticos, drains |

| Phase 2 | Later Hellenistic | Domestic insulae |

| Phase 3 | Early Hellenistic | Monumental building, domestic insula |

| Phase 4 | Persian | Pits, scanty architecture |

| Phase 5 | Iron 2c | Scanty remains |

| Unclear | Iron 2b–Iron 2a | — |

| Phases 6–9 | Iron 2a–Iron 1a late | Courtyard house |

| Phase 10 | Iron 1a early | Copper/Bronze metal working |

| Missing | Late Bronze | Iron 1 | — |

| Phases 11–12 | Late Bronze IIB | Dumping of metallurgical debris |

Table 20.1

Table 20.1Radiometric determinations from Area G produced by liquid scintillation counting from charcoal samples

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIB Ch. 20)

| Age | Dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3300-3000 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3000-2700 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2700-2200 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze I | 2200-2000 BCE | EB IV - Intermediate Bronze |

| Middle Bronze IIA | 2000-1750 BCE | |

| Middle Bronze IIB | 1750-1550 BCE | |

| Late Bronze I | 1550-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1150 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1150-1100 BCE | |

| Iron IIA | 1000-900 BCE | |

| Iron IIB | 900-700 BCE | |

| Iron IIC | 700-586 BCE | |

| Babylonian & Persian | 586-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-167 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 167-37 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 37 BCE - 132 CE | |

| Herodian | 37 BCE - 70 CE | |

| Late Roman | 132-324 CE | |

| Byzantine | 324-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | Umayyad & Abbasid |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | Fatimid & Mameluke |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

| Phase | Dates | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Early Bronze IA-B | 3400-3100 BCE | |

| Early Bronze II | 3100-2650 BCE | |

| Early Bronze III | 2650-2300 BCE | |

| Early Bronze IVA-C | 2300-2000 BCE | Intermediate Early-Middle Bronze, Middle Bronze I |

| Middle Bronze I | 2000-1800 BCE | Middle Bronze IIA |

| Middle Bronze II | 1800-1650 BCE | Middle Bronze IIB |

| Middle Bronze III | 1650-1500 BCE | Middle Bronze IIC |

| Late Bronze IA | 1500-1450 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1450-1400 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIA | 1400-1300 BCE | |

| Late Bronze IIB | 1300-1200 BCE | |

| Iron IA | 1200-1125 BCE | |

| Iron IB | 1125-1000 BCE | |

| Iron IC | 1000-925 BCE | Iron IIA |

| Iron IIA | 925-722 BCE | Iron IIB |

| Iron IIB | 722-586 BCE | Iron IIC |

| Iron III | 586-520 BCE | Neo-Babylonian |

| Early Persian | 520-450 BCE | |

| Late Persian | 450-332 BCE | |

| Early Hellenistic | 332-200 BCE | |

| Late Hellenistic | 200-63 BCE | |

| Early Roman | 63 BCE - 135 CE | |

| Middle Roman | 135-250 CE | |

| Late Roman | 250-363 CE | |

| Early Byzantine | 363-460 CE | |

| Late Byzantine | 460-638 CE | |

| Early Arab | 638-1099 CE | |

| Crusader & Ayyubid | 1099-1291 CE | |

| Late Arab | 1291-1516 CE | |

| Ottoman | 1516-1917 CE | |

- Fig. 2.1

- Superposition of Phases 9–6 in Area G from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Superposition of Phases 9–6.

(d09Z3-1287)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 3.2

- Axonometric Superposition of Phases 9-6 in Area G from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 3.2

Fig. 3.2

An axonometric superposition of Phases 6–9, showing the continuity of wall sequences in the Area G house.

(d10Z1-1011)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.12

- Phase 9 destruction debris in Room 18033 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.12

Fig. 2.12

Section through the Phase 9 destruction debris in Room 18033, looking west. Note in situ jars on floor, with mudbrick and stone collapse on top and burnt beams and roofing material above

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p09Z3-6011)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.13

- Closeup on burnt roof material in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.13

Fig. 2.13

Close-up of roof collapse seen in section in Fig. 2.12. Above the beams: burnt organic layer with packing of mudbrick material above

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p09Z3-6014)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.14

- Closeup on collapsed roof material in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.14

Fig. 2.14

Close-up of roof collapse in western balk in Room 18033, opposite the roofing material in Figs. 2.12 and 2.13. Note the two cross-members under the brush and a thin white organic layer (mat? fronds?) draping across them

(photograph courtesy of J.C. Monroe)

(p08Z3-1460)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.22

- Plan of the Phase 9 courtyard house from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.22

Fig. 2.22

Plan of the Phase 9 house, with rooms and possible accessways.

(d09Z3-1447)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.26

- Phase 9 collapse debris from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.26

Fig. 2.26

Collapsed debris tumbled against installation 9982 (on right), looking north. Center and left: fallen stones and mudbrick below three layers of fallen ceiling material (=Fig. 9.39).

(p05Z3-0610)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.29

- Phase 9 trough-installation in "courtyard" from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.29

Fig. 2.29

Phase 9 trough-installation 9982 with bin 9805 and pavement F18087 to its left, looking north. Right: unpaved part of courtyard with "tripod" installation. Traces of fire clearly seen on both floor and installation.

(p08Z3-1010)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.30

- Phase 9 wall alignment from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.30

Fig. 2.30

- The conceptual grid along which most walls and spaces in the house are aligned

- Superposition of Phases 9-6 walls imposed on the grid

See Fig. 2.1 for key to phases.

(d09Z3-1297)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.45

- Phase 9 schematic plan from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.45

Fig. 2.45

Phase 9, schematic plan

(d10Z1-1009)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.46

- Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.46

Fig. 2.46

Area G destruction as first encountered in 1992, looking west. Center: narrow partition belonging to southeastern edge of trough-installation 9982, not yet fully exposed (=Fig. 9.41)

(p08Z3-1004)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.47

- Phase 9 destruction layer as seen in a balk from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.47

Fig. 2.47

View of eastern balk, AI/32, showing the depth of Phase 9 destruction debris; the arrow marks the top of the destruction material. Square supervisor Robyn Talman standing on courtyard floor

(photograph courtesy of Andrew Stewart)

(p08Z3-1440)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.48

- Broken Pottery in Phase 9 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.48

Fig. 2.48

In situ pottery near the trough-installation, looking west. Note basalt bowl, upper grinding stone (above meter stick) and "stone tripod" at bottom (=Fig. 9.47).

(p09z3-6007)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.49

- Broken Pottery on the floor of Room 18033 in Phase 9 destruction layer from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.49

Fig. 2.49

Jars in destruction on Phase 9 floor in Room 18033, looking west (=Fig. 8.29).

(p08Z3-1459)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.50

- Phase 9 destruction layer in Room 18239 from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.50

Fig. 2.50

F18239 under excavation, looking south. Note slope of surface, with in situ pottery and deer antler.

(p08Z3-1007)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.53

- The "basin" in Room 9928 (possible subsidence) from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.53

Fig. 2.53

The "basin" in possible entryway in Room 9928, looking south

(photograph courtesy of Andrew Stewart)

(p09Z9-6009)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA) - Fig. 2.54

- Artist's depiction of Phase 9 Courtyard House immediately before destruction from Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Fig. 2.54

Fig. 2.54

An artist's view of Phase 9, showing a suggestion of the rooms' functions based on their contents when destroyed, looking north

Drawing: T. Kurz, based on an earlier drawing by V. Damov.

(d09Z3-1288))

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Table 2.1 (aka Chart 1)

Table 2.1 (aka Chart 1)Comparative stratigraphy and chronology of Areas G, D2, D5 and B1 and correlation to Megiddo strata

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Table 2.2 (aka Chart 2)

Table 2.2 (aka Chart 2)Area G Bronze and Iron Ages phases and horizons by context

- Small Roman numerals (i, ii, etc.): local stages within unit

- Thick separator between stages: evidence for destruction or trauma

- Asterisk (*): context fully illustrated (numbers above are plate nos. in Volume IIC)

- Arrows (↔): placement of the stage separator (or of the entire stage) is arbitrary; it might be moved right (later) or left (earlier)

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIA)

Table 20.1

Table 20.1Radiometric determinations from Area G produced by liquid scintillation counting from charcoal samples

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIB Ch. 20)

PROGRESS OF FIELDWORK AND SCOPE OF EXCAVATION

... It was also at this phase of excavation that we first encountered the Phase 9 destruction layer in the central courtyard, with its “trough” installation possibly meant for processing grain (“the bakery”) (Fig. 1.11). The discovery of this destruction event enabled the possibility of linking the disparate early Iron Age deposits across the tell. By this time, massive destructions of the same chronological horizon had been excavated in Area B1 and in a narrow probe in Area F. Similar destruction horizons were subsequently found in Areas D2 and D5. It is the building of Phase 9, with in situ deposits on almost all of its floors, that came to be the best understood structure in Area G and serves as the focus of the functional analysis attempted in Chapter 2.

Phase 9: Ir1a late (ca. 1100/1075–1075/1025 BCE)

Phase 9 is the best-preserved and understood phase in Area G because of the destruction that sealed its fate and contents. Most rooms contain in situ or otherwise primary deposits of pottery and other objects of daily use. They also occasionally preserve some ecofacts related to the use of the space. This allows a fairly comprehensive picture to be drawn of an area ca. 10 x 15 m, 150 sq m. Despite this relatively wide exposure, however, the entire area of the structure was not uncovered and only three rooms are known in their entirety.

The area of Phase 9 (Fig. 2.45) is dominated by the large central courtyard (9795), at least 6 m north to south and over 5 m east to west (Plan 5). The western half of the courtyard was stone-paved, while the eastern part had an earthen floor; the stone pavement was re-established in the same location in Phases 8 and 7 as well. South of the courtyard is Room 18033, ca. 2 m north to south and at least 2.5 m east to west. To the west of the courtyard are R ooms 18242, 18241, 18239 and 04G0-004. The latter had a stone pavement in its northern part. The size of these rooms is unknown due to incomplete excavation, but 18242 is very narrow, only about 1 m wide. Immediately north of the courtyard are a series of rooms (18067, 9928 and 18750), all about the same size, ca. 3.8 m north to south and 2.5 m east to west. In the northern half of Room 9928 was a thick, basin-like clay floor. To the northwest of these are two partially excavated rooms: 18089 and 18041.

The Phase 9 Destruction

When first encountered at the southern end of AI/32 (Fig. 2.46), the Phase 9 destruction appeared as a mass of swirling burnt orange, black and white mudbrick debris, interspersed with bits of carbonized roofing timbers, fallen stones and fire-hardened mudbricks and ceiling plaster. Heat-altered clay and other components in this destruction debris indicate a fire temperature above 500°C and, in places, as high as 1000° (Berna et al. 2007). In some of the rooms, this destruction layer was 90 cm thick (Fig. 2.47). The fiery destruction did not, however, engulf the entire house. The burnt layer was thickest and most impressive in AI/31 and AI/32 in the south, but dwindled and petered out as it spread towards AI/33 to the north and AJ/32 to the west (cf., Chapter 3, Fig 3.31). It thus seems that most of the highly combustible materials were concentrated in a relatively small part of the overall structure (but see more on this below). However, vessels in primary deposition in the north and west (such as in Rooms 18570, 18241 and more) indicate that these rooms too were destroyed (although not burnt) and, in any case, at least part of their contents abandoned. In other rooms (e.g., 04G0-004), there was no unequivocal evidence of destruction. Because this latter room was the last to be excavated, with the express purpose of locating the destruction level, we did notice that the constructional fill below the Phase 8 floors contained what seems to probably be degraded burnt orange mudbrick debris and that the floor was covered by (unburnt) mudbrick collapse. Had we gone in unsuspecting, however, it is doubtful that we would have noted any traces of trauma. This should be a cautionary note to the concept of destruction layers which ostensibly can serve as "benchmarks" for site stratigraphy and for correlation with known or assumed historical events. The actual phenomenology of destruction, even for a very traumatic event, can be very localized and may seem arbitrary.

Although in primary deposition, not all the pottery in the rooms was in situ. Vessels were scattered about over quite large distances and their original positions could only seldom be reconstructed. This means that there is no certainty that other artifacts were found in their systemic contexts either. At least in some cases, we have clear evidence that pots were broken and their sherds were scattered about not only before the architecture collapsed, but also before the fire started. In many of the reconstructed vessels (e.g., the krater and pithos in Chapter 20, Pls. 20.21:19; 20.25:3), fragments that were heavily burnt mended with others that were not, demonstrating that they were exposed to fire only after they were broken. This seems to best fit a scenario in which the house was ransacked and then burnt, although alternative explanations (e.g., an earthquake and a subsequent fire) cannot be entirely ruled out

Room 18033

As mentioned above, this space to the south of the courtyard was only partially excavated and it is unclear whether it was indeed a separate room or possibly a pantry/storage space associated with the courtyard, as indicated by the numerous, densely packed storage containers found here (Fig. 2.49). The fact that it could be directly accessed from the courtyard implies that no attempt was made to control or regularize access to the goods stored in these containers. Alongside the courtyard, this is the space where the conflagration was the heaviest, as indicated by masses of burnt wood, burnt mudbrick and other debris, although not all the vessels showed signs of burning. When mended, several vessels showed conjoint burned and unburned pieces, as mentioned above, indicating that they were broken and scattered before the fire. It probably also indicates that (at least in some cases) structural collapse preceded the fire, covering and protecting some of the potsherds on the floor.

... The charcoal in Room 18033 (Loci 18033 and 18265) yielded four 14C dates (Chapter 20, Table 20.1).

Table 20.1

Table 20.1Radiometric determinations from Area G produced by liquid scintillation counting from charcoal samples

Gilboa et. al. (2018 v. IIB Ch. 20)

Rooms 18242, 18241 and 18239

Distinctive evidence for fire gradually diminishes as one moves from Courtyard 9795 west into Corridor 18242 and thence into 18241 and northwards into 18239. On the other hand, all of these spaces, as well the opening between Rooms 18241 and 18242 (L18293) had quite a few restorable vessels. Unlike Courtyard 9795 and Room 18033, where the restorable pottery was by-and-large smashed on the floor and sealed by more-or-less sterile mudbrick collapse, in these rooms, at least some of the restorable pottery came from the collapse above the floor, giving a distinct impression that it fell from an upper story. This is most clearly the case in Room 18239, where two distinct "floor"' surfaces were detected. F18239, the upper, is sharply sloped and appears to be sagging towards the center of the room, where it nearly merges with the lower floor, F18370 (Fig. 2.50). We interpret the upper surface to be the floor of the second story which fell onto the first.

... Room 18239 also produced three human bones: two finger bones and a skull fragment (not discussed in Chapter 29). These are the only human bones in the Area G sequence, other than a complete skeleton buried under a stone collapse in Phase 7 (below and Chapter 29). One of the bones, however, was found in the fill well above the floor, although restorable pottery was found at approximately the same elevation.

Rooms 18041 and 18089

These two rooms in the far north of the building were only minimally excavated in Phase 9 and hardly produced any finds. In Room 18041, nothing can be demonstrated to be in primary deposition (Chapter 20, Pl. 2032). In Room 18089, destruction is evident by crushed pottery which was partly overlain by stone collapse and mudbrick debris, with only very few traces of fire. This room had been disturbed by the "cult deposit" 9903 of Phase 8 (infra). Two bowls, one large piece of a krater and the upper part of a decorated piriform jar are probably in primary deposition (Chapter 20, Pl. 2033:4-5, 8,10). In addition, a wavy-band pithos was represented here by dozens of fragments which could not be joined and were not illustrated. Open vessels are also dominant among the sherd material from this room and only one fragment of a straight shouldered jar was recorded (Chapter 21).

The only other notable find, in Room 18089, was an oblong decorated ivory plaque (Chapter 26, Fig. 26.3:3) ...

Room 9928

As mentioned, this room is the main candidate for an entryway to the excavated part of the building. Its thick clay floor (Fig. 2.53) suggests a special role, although this remains unclear and it is likewise uncertain if its basin-like shape is related to this role or is a result of subsidence. ...

The End of Phase 9

What precipitated the fire that was coincident with the overall destruction of the building? Although extremely intense, it evidently was fairly well confined to the area used for the storage and processing of grain and perhaps of other food products. However, many of the jars were found broken and body pieces of restorable vessels were found strewn around these rooms. This breakage happened before they were burned. The western half of the courtyard contains some evidence of building collapse from the west. Only a few fragments of human remains were found in the destruction debris, most valuables seem to have been removed and the building was rebuilt along exactly the same lines almost immediately (see below, Phase 8).

The Phase 9 destruction is the only event that, most plausibly, can be identified across more than one excavation area at Dor. Destruction levels, which by their ceramic contents are attributed to the same horizon (Irla early) were unearthed in Area B1 on the far east (Phase B1/12), Area D5 on the southwest (Phase D5/11) and Area D2 on the south (Phase D2/13) (Table 2.1). A small probe on the west, in Area F, also produced destruction debris with similar pottery. Although it will never be possible to unequivocally demonstrate that all these mishaps are the result of the same event, this is highly probable. Throughout the 2400 years of occupation history in all these areas, this is the only clear fiery destruction. Not every house was burnt, nor even destroyed, yet this seems to have been a site-wide disruption. On present evidence, this catastrophe happened between 1075-1025 BCE, possibly slightly later, ca. 1000 BCE (see Tables 2.1-2.2 and discussion in Chapter 20).

Considering Area G alone, it seems impossible to decide between accident (a kitchen fire), belligerent action or natural catastrophe (an earthquake) as the cause of the disaster that brought Phase 9 to a fiery end. However, the probable parallel destructions in other areas indicate that this was not a localized event. Stern (e.g., 1990; 1991) associates this destruction with the conquest of this part of the coast by Phoenicians from Lebanon (about 1050 BCE) and Halpern (1996: n. 8), with an Israelite conquest. Others (e.g., Gilboa 2005; Sharon and Gilboa 2013) deny any cultural upheaval coincident with this destruction, but remain undecided as to its exact nature. In any event, the structure was rebuilt along almost identical lines, there is no break in local material cultural traditions across Phases 10-6 and there is no intrusion of a new material culture after Phase 9.

THE IRON AGE: PHASES 10–5, IR1a–IR2c

Introduction

Area G at Dor is justly renowned for its early Iron Age sequence, extending through five phases (10-6) and over 3 m of cultural debris, covering a span of some 300 years, from Ir1a early to Ir2a (Iron Age IB to Iron Age IIA in the terminology used in Mazar 1990). Due to the very meager and poorly preserved remains between the end of Phase 6a of Ir2a and the end of Phase 5 in the 7th century BCE, the nature of occupation of this area in the latter part of the Iron Age is currently undeterminable. ...

A Brief synopsis of the history of the house

This report treats Phases 12–5 as one continuous developmental sequence, based on the fact that these phases represent one evolving entity, the kernel of which is what we hold to be a single house which existed in Phases 9–6, over a period of some two centuries (regardless of the absolute chronology; see below). Despite the fact that the house was destroyed at least once during this sequence (and possibly twice or even three times), there is conceptual continuity in the plan (and probably in the use) of the structure throughout these phases (Fig. 2.1). Some of the walls built in Phase 9 (e.g., W9140, W9684, W9266) continued to be used unchanged until Phase 6, if not even later. In other cases, walls were rebuilt, nearly always on the same lines as previous walls. Actual architectural changes are limited to partitioning spaces (in particular the courtyard), moving installations, etc., as detailed below. Finally, the ceramic picture is very similar to the architectural one. Pottery traditions in Phases 9 through 6 follow a similar pattern of gradual change. In general, the locally produced pottery becomes simpler both in form and decoration.

... Whether or not the Phase 10 architecture should be considered part of the Phases 9–6 house is unclear, partially because its exposure is fairly limited. The little that can be said is that the Phase 9 house makes limited use of some Phase 10 walls ...

... As regards ceramics, the Iron Age traditions emerge from those of the LBA. However, at least in the limited area where LBA layers were exposed, there seems to be a hiatus in habitation between Phases 11 and 10. The latest pottery in LBA Phase 11, including Cypriot and Aegean-type imports, dates to the early 12th century. On the other hand, fills immediately below and above the first floors of the Iron Age construction in Phase 10 already produced Philistine Bichrome fragments, some of them demonstrated by petrography to indeed have been imported from Philistia. This means that no habitation has been revealed in Area G that would be contemporary with the Philistine Monochrome (or “local Myc IIIC”) horizon in Philistia. This includes most of the Egyptian 20th Dynasty (for details, see Chapter 20). Typologically, and in every cultural respect, the local Phase 9 pottery is a direct continuation of that of Phase 10 (Chapter 20), although minute transformations in the formal attributes of many pottery shapes indicate that considerable time had elapsed—a generation or, perhaps, two.

The period following the use of the house, the Iron Age IIC (what happened in this area during Iron IIB is unclear), is represented by a single phase (5), which is heavily damaged by Persian period pits of Phase 4 and later massive construction of the Hellenistic to Roman eras (Phases 1–3). Combined, Iron IIB–C cover a span of time similar to the entire Phases 10–6 sequence, ca. 800 (depending on the chronology employed) to ca. 600 BCE. Only a few fragments of walls and patches of floor attest to habitation in this long period. We cannot say anything definitive about its architecture, least of all to what extent, if any, it formed part of the architectural continuum described for Phases 9–6. No significant ceramic assemblages were recovered and the few late Iron Age sherds in reliable contexts point to the 7th century, when Dor was ruled by the Assyrians, as the date for the end of Phase 5.