Yavne

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Yavne | Hebrew | יַבְנֶה |

| Jabneh | English | |

| Jamnia | Greek | Ἰαμνία |

| Jamnia | Latin | |

| Iamnia | ||

| Yibna | Arabic | يبنى |

| Yubna | Arabic | يبنى |

| Ibelin | Crusader (Frankish?) |

Yavne has a long history of habitation with occupation on the Tel dating back to the Bronze or Iron Age. It is mentioned in Joshua 15:11 and 2 Chron 26:6 of the Hebrew Bible. The Jewish Sanhedrin was relocated to Yavne after the destruction of the second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE and it is regarded as the birthplace of modern Rabbinic Judaism.

Yavneh is situated c. 25 km south of Tel Aviv and c. 8 km from Mezad Ḥashavyahu on the Mediterranean coast. It was occupied throughout many periods, making it difficult to estimate the extent of the ancient city, which is covered with a thick accumulation of later remains including those of a medieval fortress and an Ottoman period village. The mound occupies a prominent hill, about 45 m above sea level, at the center of the modern city of Yavneh. Ancient remains are also present outside the mound proper.

Yavneh is mentioned in numerous sources from the Iron Age onwards, some of the references providing accurate information as to its location. The ancient name has survived to this day. It was mentioned by many travelers and scholars, including V. Guérin, F. M. Abel, C. R. Conder, and H. H. Kitchener. Its identification has never been a matter of controversy. Recently, however, S. Weingarten and M. Fischer suggested that Ibelin, the name by which Yavneh was known in the Crusader period, derived from the name Abella, which appears in the Theophanes archive and comes from Mount Ba‘alah in Joshua 15:11. However, these are two different sites. Mount Ba‘alah is generally identified with the ridge of el-Mughar, a few kilometers northeast of Yavneh (as claimed by J. Kaplan, B. Mazar, and N. Na’aman). Since settlement at Yavneh was continuous, the change of the name from Mount Ba‘alah to Yavneh is unlikely. The appearance of the name Ibelin/Abilin should probably be understood as a simple linguistic corruption of the name Yavneh.

Yavneh is first mentioned in the biblical description of the borders of Judah, probably dating to the late Iron Age II. It is called Jabneel and is located on the northern border of Judah along the Sorek River (Jos. 15:11). According to 2 Chronicles 26:6, Jabneh (Iabnia in the Vulgate) was captured from the Philistines, together with Ashdod and Gath, by King Uzziah. Many scholars believe this verse to be a reliable source, evidence that Yavneh was ruled by the Philistines prior to Uzziah’s conquest.

Sources about the region are lacking for most of the Persian period. Yavneh is mentioned in the Book of Judith (3:1; Vulgate 2:28). It was later a Hellenistic city, included first in Idumea and then in the Paralia (coastal) region. A second-century BCE inscription from Delos mentions people from Yavneh who made offerings to the gods Heracles and Auronus (Horon). A story in 2 Maccabees 12:40 relates that some Jews died in battle because of the sin of carrying under their tunics “amulets sacred to the idols of Jamnia.” Unfortunately, nothing further is said about these idols.

The Seleucids used Yavneh as a base of operations against Judea. According to 1 Maccabees 5:55–62, Gorgias, the governor of the area, established his base there and repulsed a Judean attack. Judah Maccabee apparently attacked Jamnia by night and set fire to its harbor (2 Macc. 12:3–9). A contemporary inscription from Yavneh-Yam mentions Sidonians who rendered service to King Antiochus V, without any reference to an attack by Judah Maccabee. When Apollonius was appointed over Coele Syria (147 BCE), he encamped at Yavneh and battled with Jonathan the Hasmonean (1 Macc. 10:67–89; Josephus, Antiq. XIII, 88–102). Under Antiochus VII, Cendebeus established himself in Yavneh as governor of the coast and began to harass Judea (1 Macc. 15:40). According to Josephus (Antiq. XIII, 215), Simeon captured Gazara, Jaffa, and Jamnia (137 BC), although they may have been taken by his son, John Hyrcanus (135– 104 BCE). Alexander Jannaeus controlled Yavneh, from which point it is mentioned in ancient sources as a city with a Jewish population.

Pompey made Yavneh an independent city under Gabinius, the proconsul of Syria (War I, 157, 166; Antiq. XIV, 75). Around 30 BCE, Augustus granted the city to Herod, who willed it to his sister Salome; she handed it over to Augustus’ wife, Livia, and it later passed into the possession of Tiberius (Antiq. XIII, 321). Philo of Alexandria mentions Jamnia as a large city in Judah. Strabo writes that Jamnia is located about 200 stadia from both Gaza and Ashkelon. Though called a village, the area of Yavneh was densely populated. From this time onwards, the port of Yavneh (YavnehYam) is mentioned separately from the city (Pliny, NH 5, 68). Yavneh was a seat of a procurator named Herennius Capito (also known from an inscription from Italy), who is said to have erected an altar in the city in order to provoke the Jews, who were a majority there. The destruction of this altar led to the occupation of Judea by Rome (Antiq. XVIII, 158; War IV, 130, 663).

According to a famous legend, Yohanan b. Zakkai persuaded Vespasian to “leave him Yavneh and its sages” after the destruction of the temple (70 CE). Yavneh became the seat of the Sanhedrin and the birthplace of rabbinic Judaism. The Mishnah is said to have been edited there. Many references in rabbinical literature deal with sages from Yavneh, particularly Yohanan and Gamliel b. Zakkai. However, the nature of the sources does not allow for a precise history of these sages. As a result of the Second Jewish Revolt (130–135 CE), the Sanhedrin moved to the Galilee and Yavneh lost its importance in Jewish spiritual life.

The Samaritans became part of the population of Yavneh and built a synagogue there, as is evident from an inscription found not in situ. Petrus the Iberian encountered a strong Samaritan population at Yavneh c. 500 CE. During the Byzantine period, it was primarily a Christian city, and the seat of a bishop. The names of six bishops from Yavneh are known. They participated in the councils at Nicea (325 CE), Chalcedon (451 CE), and Jerusalem (518 and 536 CE). Eudocia built a church in the city and Eusebius listed it in his Onomasticon. The Medeba map of the sixth century refers to Yavneh as “Jabneel, which is also Iamneia.”

There are few references to Yavneh from the Early Islamic period. According to al-Baladuri, Yavneh (Yubna) was captured by the Arabs in 634. In 891, al-Yaqubi, in his Geography, describes Yavneh as an ancient village with a Samaritan population. Al-Muqaddasi (985) mentions a magnificent mosque at Yavneh and the fertility of its region. A Crusader castle called Hibelin or Ibelin was established at Yavneh by Fulco, King of Jerusalem (1142). It was ruled by a seigneur, Balian, and his family. William of Tyre erroneously identified it with Philistine Gath. Benjamin of Tudela (c. 1160) wrote that “from [Jaffa] it is five parsangs to Ibelin or Jabneh, the [former] seat of the Academy, but there are no Jews there at this day.” Saladin conquered Yavneh in 1187, and Richard the Lionheart allegedly camped in the ruins of the castle in 1191.

During the Mameluke period, the impressive structure known as Abu Hureirah’s tomb was built by Baybars I at Yavneh. Yaqut (1225) refers to Yavneh as a pleasant place near Ramla, and mentions the tomb. Abu Hureirah was one of Muhammad’s companions, but he was buried at Medina and his connection with the tomb at Yavneh is probably a secondary tradition; its identification as the tomb of Gamliel is a recent invention. During the Mameluke period, a bridge was erected over the Sorek River northeast of the mound, continuing in use until the twentieth century. The large mosque on the mound, built on a former church and now in ruins, contained an inscription of Suleiman en-Nasiri from 1337; it was published by Conder and Kitchener.

In the Ottoman period, Yavneh was an Arab village related to the Gaza district, with 710 people registered in 1596. Nineteenth-century travelers describe it as composed mostly of humble mud-huts, with only a few ancient remains visible above ground. The largely abandoned village came under Israeli control in early June 1948. Soon afterwards, the present city of Yavneh was established nearby.

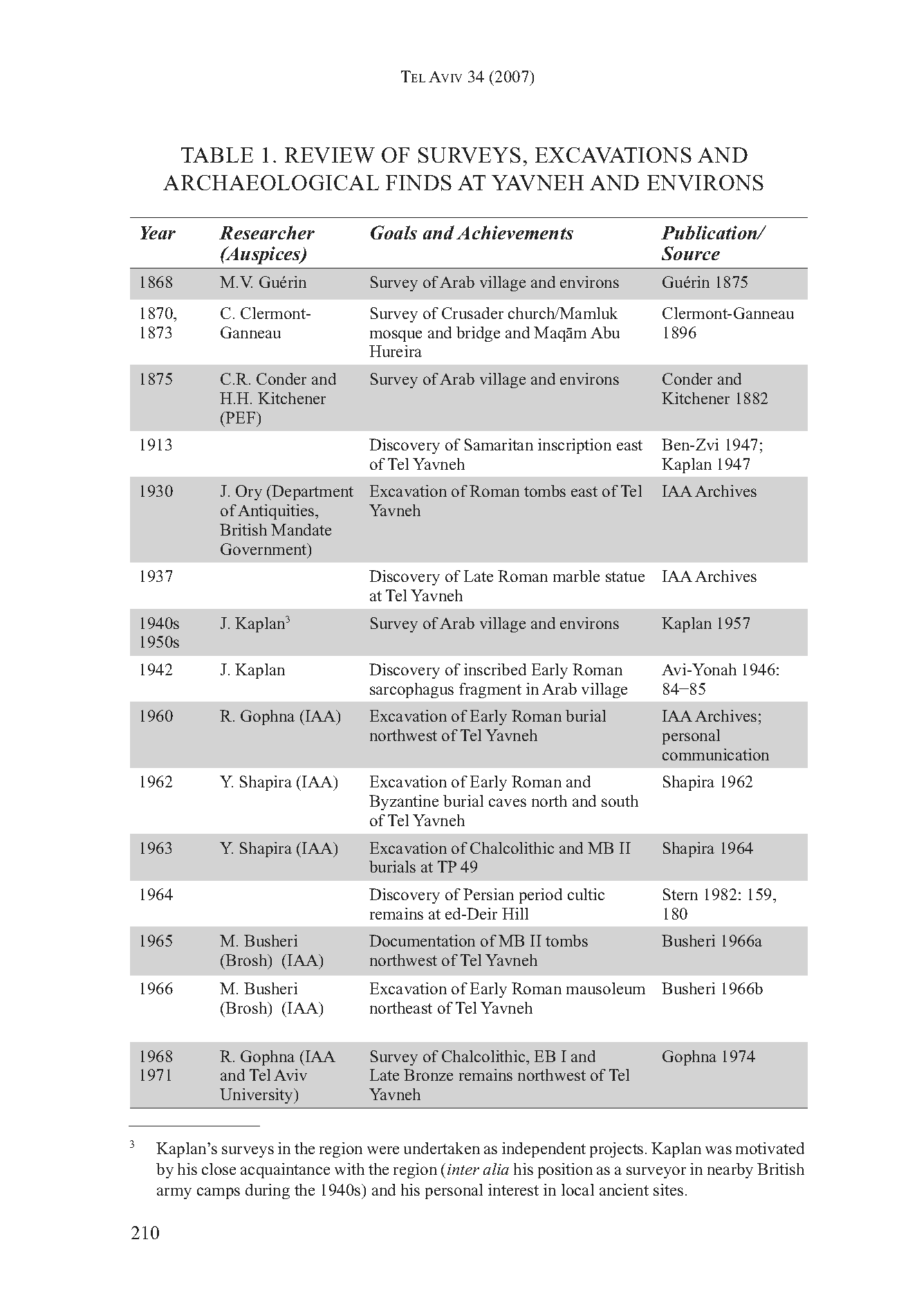

Despite its large size and easily accessible location, the mound of Yavneh has not yet been excavated. In 1957, it was surveyed by J. Kaplan, and in the late 1980s, by A. Maeir and D. Pringle. Numerous salvage excavations have been conducted in the vicinity of the mound, mainly in the wake of development projects in the modern city. The first excavation was conducted in Mandatory times by J. Ory, on behalf of the Palestine Department of Antiquities (1930). He uncovered remains of a Roman period cemetery during the construction of a section of the railway line east of the mound; it lay under debris from the Byzantine period. A second excavation by Ory (1951) and one by S. Piphano (1983) have not been published. M. Brosh excavated a Middle Bronze Age tomb and Roman sarcophagi near Ge’alya, northeast of Yavneh (1964), as well as a Roman period mausoleum containing gold jewelry near Nahal Yavneh (1966).

Since 1990, more than 13 salvage excavations have been carried out at Yavneh. In 1989–1990, Y. Levi excavated Byzantine period remains north of the mound, an ashlar wall with Roman–Byzantine coins near Abu Hureirah’s tomb, and a Byzantine period kiln southwest of the mound. A. Feldstein and O. Shemueli examined buildings and other finds west of the mound, mainly from the Byzantine period. I. Barash excavated Byzantine–Early Islamic remains south of the Mameluke bridge. A. Gorzalzcany mapped a vaulted building on the eastern slope of the mound. C. Eliaz excavated several small areas containing Roman, Byzantine, and Early Islamic remains east of the mound. Other excavations were carried out but have not yet been published.

In a cemetery excavated north of the mound by R. Kletter in 2000–2001, a Late Bronze Age tomb and several Iron Age II/Persian period tombs were uncovered. The latter included tombs built of kurkar masonry, as well as simple graves dug in pits. The graves were covered by a 2-m-thick accumulation of Byzantine and modern remains.

- Fig. 2 - Aerial View of

Tel Yavneh from Fischer and Taxel (2007)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Tel Yavneh, aerial view, looking north.

Fischer and Taxel (2007) - Yavne in Google Earth

- Yavne on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated Aerial View of

Yavne from BibleWalks.com

- Map 2 - Tel Yavneh and

environs from Fischer and Taxel (2007)

Map 2

Tel Yavneh and environs

- TP 49, excav., Shapira ’62(?), ’63

- MBII tombs, documen., Busheri ’66

- Excav., Dagot ’03

- Ed-Deir Hill, excav., Honigman ’78, Kletter ’02

- Excav., Kletter ’00–’01

- Maqam Abu Hureira

- Excav., Feldstein and Shmueli ’93

- Maqam ash-Sheikh Salim

- Excav., Levi ’90

- Mamluk bridge, excav., Busheri ’66

- Excav., Meron ’72

- Excav.,Barash ’99

- Quarry cave

- Excav., Levi ’88

- Excav., Levi ’91

- Excav., Levi ’91

- Excav., Eliaz ’99

- Excav.,Velednizki ’00;

- Excav., Sion ’00

- Remains, Byzantine public building

- Crusader fort, excav., Bahat ’05

- Crusader church/Mamluk mosque

- Excav., Levi ’87

- Excav., Eliaz ’99

Fischer and Taxel (2007) - Fig. 1 Location Map from

Yannai (2014)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Location Map

Yannai (2014)

- Fig. 2 Plan of Area A

from Yannai (2014)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Area A, plan

Yannai (2014)

- Fig. 2 Plan of Area A

from Yannai (2014)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Area A, plan

Yannai (2014)

- Fig. 9 Plan of Area C

(the kiln complex) from Yannai (2014)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Area C, the kiln complex, Plan

Yannai (2014)

- Fig. 9 Plan of Area C

(the kiln complex) from Yannai (2014)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Area C, the kiln complex, Plan

Yannai (2014)

- Fig. 5 Master Aerial Photo

of seismic destruction in the kiln complex (Area C) from Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 5

Figure 5

- An aerial photo of one of the clusters of the unique pottery kiln complex. The kilns were connected by barrel-shaped and covered tunnels with a common entrance.

- Fallen columns.

- End of burning process.

- Fig. 10 Aerial photograph of

the kiln complex from Yannai (2014)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Area C, the kiln complex, aerial photograph looking northwest

Yannai (2014) - Fig. 13 Aerial photograph of

fallen columns from Yannai (2014)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Area C, the stone colonnaded building after the earthquake, aerial view looking northwest

Yannai (2014) - Fig. 6 The kiln during the

excavation from Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 6

Figure 6

The kiln during the excavation. We were able to collect four in situ sealed dust samples for palynological investigation from the kiln’s floor, underneath unbroken ceramic vessels. An additional sample was collected 2-3 cm above the kiln’s floor. The black arrow points to the debris/clay fragments (which were used to cover the kiln during the heating process) and were deposited after the earthquake.

Langgut et al (2015)

- Fig. 7 Possible sequence

of events in the kiln from Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 7 - Possible sequence of events in the kiln.

Figure 7 - Possible sequence of events in the kiln.

- Construction of the kiln; laying the freshly made pots at the bottom.

- Covering with debris/clay fragments; igniting fire, heating.

- End of burning process.

- Removing debris/clay fragments; beginning of vessels’ cooling process. Pollen penetrated the kiln (with the cooling air) and was deposited on the floor, but was partially damaged due to the still high temperatures (as evidenced by the group of degraded palynomorphs D charred pollen). Pollen (of spring bloomers) penetrated and was deposited on the kiln’s floor when normal temperatures prevailed in the kiln (and was therefore well preserved).

- An earthquake - the kiln collapsed.

- The burial of the kiln: sediments were deposited covering the burnt material.

- Fig. 10 Aerial photograph of

the kiln complex from Yannai (2014)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Area C, the kiln complex, aerial photograph looking northwest

Yannai (2014) - Fig. 5 Master Aerial Photo

of seismic destruction in the kiln complex (Area C) from Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 5

Figure 5

- An aerial photo of one of the clusters of the unique pottery kiln complex. The kilns were connected by barrel-shaped and covered tunnels with a common entrance.

- Fallen columns.

- End of burning process.

- Fig. 13 Aerial photograph of

fallen columns from Yannai (2014)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Area C, the stone colonnaded building after the earthquake, aerial view looking northwest

Yannai (2014) - Fig. 6 The kiln during the

excavation from Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 6

Figure 6

The kiln during the excavation. We were able to collect four in situ sealed dust samples for palynological investigation from the kiln’s floor, underneath unbroken ceramic vessels. An additional sample was collected 2-3 cm above the kiln’s floor. The black arrow points to the debris/clay fragments (which were used to cover the kiln during the heating process) and were deposited after the earthquake.

Langgut et al (2015) - Fig. 7 Possible sequence

of events in the kiln from Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 7 - Possible sequence of events in the kiln.

Figure 7 - Possible sequence of events in the kiln.

- Construction of the kiln; laying the freshly made pots at the bottom.

- Covering with debris/clay fragments; igniting fire, heating.

- End of burning process.

- Removing debris/clay fragments; beginning of vessels’ cooling process. Pollen penetrated the kiln (with the cooling air) and was deposited on the floor, but was partially damaged due to the still high temperatures (as evidenced by the group of degraded palynomorphs D charred pollen). Pollen (of spring bloomers) penetrated and was deposited on the kiln’s floor when normal temperatures prevailed in the kiln (and was therefore well preserved).

- An earthquake - the kiln collapsed.

- The burial of the kiln: sediments were deposited covering the burnt material.

Archeological dating alone was able to identify destruction at Yavne to the 7th century CE but was unable to distinguish between two candidate earthquakes - the Sword in the Sky Quake of September 634 CE and the Jordan Valley Quake of June 659 CE. Although there is some chronological ambiguity regarding the exact year of both of these earthquakes, the time of year (June vs. September) was attested in a number of the historical sources making this location an ideal site to use seasonal palynology to distinguish between the two seismic events. Langgut et al (2015) examined pollen in a complex of pottery kilns in Area C on the eastern foot of Tel Yavne.

The pollen was extracted from the dust captured on the floor of the kiln during the cooling process of the vessels. The dust was collected only from below in situ whole vessels, and based on our reconstruction had been accumulated for about several days (after the heating process ended and before the collapse). Since the palynological assemblages included spring-blooming plants (such as Olea europaea and Sarcopoterium spinosum) and no common regional autumn bloomers (e.g. Artemisia), it is proposed that the kiln went out of use due to the early June 659 CE earthquake. We also propose that the recovery of the Yavneh workshops was no longer economically worthwhile, maybe in part due to changes in economic and political conditions in the region following the Muslim conquest.Langgut et al (2015) identified the intersection of the flowering months of identifiable pollen taxa to April-May stating that "the palynological spectra represent palynomorphs which flourished and then were embedded during March-May." This led to the conclusion that the kiln collapsed in the spring. This appears to be compatible with an earthquake which struck in early June however since the textual sources exhibited a number of chronological inconsistencies, may have relied on the same or similar sources (e.g. Jesudenah of Basra), and exhibited a tendency to produced forced synchronicities aligning natural disasters with historical events, the possibility exists that the earthquake struck earlier in the spring. Further, as noted by Guidoboni et. al. (1994), "depending on the region concerned, the month "Daesius" ("Haziran" in the Syriac calendar) will fall somewhere between mid-April and August." Theophanes specified the month of Daesius while Elias of Nisbis and the Maronite Chronicle specified the months of Haziran.

Yannai (2014) noted that palynological dating eventually reported in Langgut (2016)

adds to other evidence for a major earthquake that radically changed the pollen samples at the beginning of the Early Islamic period (Neumann et al. 2009:47–50).Yannai (2014) added

It is difficult to estimate the intensity of the earthquake and which geographic regions it affected, but there was a very sharp drop in the export of Gaza jars that occurred over a short period of time.

... During the Byzantine period, when the jars were a very common industrial product, significant changes were made in the shape and volume of the vessels. Judging by the shape of the rim and the upper part of the body, only Gaza jars that were typical of the seventh century CE were fired in the Yavne kilns. At the same time that production at Yavne flourished, Eretz Israel was conquered by the Muslims. Immediately thereafter, a significant decline is apparent in the trade of these jars and the products stored in them. These jars, which in the fifth and sixth centuries CE were the overwhelming majority of jars in Constantinople, for example, disappeared in the seventh century CE from the repertoire of pottery imported to that city (Hayes 1992:65). A sharp decline in their numbers was also noted in Israel, Egypt (Kelliaand Ostrakina) and North Africa (Benghazi). It is difficult to determine with certainty what were the causes for this, and if there was a connection between the change in rulers over Palestine and the drastic decline in the trade of products stored in Gaza jars. On the basis of the finds from the Yavne excavation, we can assume that one of the possible reasons for the sharp decline in the amount of jars is the destruction of kilns on the coastal plain following the earthquake that struck in 659 CE.

Yannai (2014) reported extensive destruction in Stratum AII (Abbasid) of

Sub-Area 2 noting that

there was no evidence of a conflagration

and that some of the walls collapsed while others were completely uprooted, together with their foundations.

Yannai (2014) suggested that the collapse may have been caused by an earthquake.

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete destruction of buildings - Collapsed Walls | Kiln Complex (Area C)

Figure 5

Figure 5

|

|

|

| Fallen and Oriented Columns | Kiln Complex (Area C)

Figure 5

Figure 5

|

Figure 13

Figure 13Area C, the stone colonnaded building after the earthquake, aerial view looking northwest Yannai (2014) |

|

| Broken Pottery in fallen position | Kiln Complex (Area C)

Figure 5

Figure 5

|

Figure 6

Figure 6The kiln during the excavation. We were able to collect four in situ sealed dust samples for palynological investigation from the kiln’s floor, underneath unbroken ceramic vessels. An additional sample was collected 2-3 cm above the kiln’s floor. The black arrow points to the debris/clay fragments (which were used to cover the kiln during the heating process) and were deposited after the earthquake. Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 7 - Possible sequence of events in the kiln.

Figure 7 - Possible sequence of events in the kiln.

|

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Sub-Area A2

Figure 2

Figure 2Area A, plan Yannai (2014) |

|

|

| Foundation damage | Sub-Area A2

Figure 2

Figure 2Area A, plan Yannai (2014) |

|

- Modified by JW from Fig. 9 of Yannai (2014)

Deformation Map

Deformation MapModified by JW from Fig. 9 of Yannai (2014)

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete destruction of buildings - Collapsed Walls | Kiln Complex (Area C)

Figure 5

Figure 5

|

|

VIII + | |

| Fallen and Oriented Columns | Kiln Complex (Area C)

Figure 5

Figure 5

|

Figure 13

Figure 13Area C, the stone colonnaded building after the earthquake, aerial view looking northwest Yannai (2014) |

|

V + |

| Broken Pottery in fallen position | Kiln Complex (Area C)

Figure 5

Figure 5

|

Figure 6

Figure 6The kiln during the excavation. We were able to collect four in situ sealed dust samples for palynological investigation from the kiln’s floor, underneath unbroken ceramic vessels. An additional sample was collected 2-3 cm above the kiln’s floor. The black arrow points to the debris/clay fragments (which were used to cover the kiln during the heating process) and were deposited after the earthquake. Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 7 - Possible sequence of events in the kiln.

Figure 7 - Possible sequence of events in the kiln.

|

|

VII + |

- Fig. 9 Plan of Area C

(the kiln complex) from Yannai (2014)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Area C, the kiln complex, Plan

Yannai (2014) - Fig. 10 Aerial photograph of

the kiln complex from Yannai (2014)

Figure 10

Figure 10

Area C, the kiln complex, aerial photograph looking northwest

Yannai (2014) - Fig. 5 Master Aerial Photo

of seismic destruction in the kiln complex (Area C) from Langgut et al (2015)

Figure 5

Figure 5

- An aerial photo of one of the clusters of the unique pottery kiln complex. The kilns were connected by barrel-shaped and covered tunnels with a common entrance.

- Fallen columns.

- End of burning process.

- Fig. 13 Aerial photograph of

fallen columns from Yannai (2014)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Area C, the stone colonnaded building after the earthquake, aerial view looking northwest

Yannai (2014)

In a peripheral building to the west of the kiln, five fallen columns "all paralleling an east-west orientation (Figure 5a and 5b)" were discovered. In Fig. 9 Yannai (2014) shows the columns fell in an ESE direction which, due to inertia forces, might suggest an epicenter in the same ESE direction. This direction points towards the southern Jordan valley or the north Dead Sea which the source documents suggest is the probable location of the epicenter of the 659/660 CE Jordan Valley Quake(s).

In discussing 31 fallen columns at the site, Langgut et al (2015) suggested that the fallen columns were part of a colonnade that was oriented in an approximate N-S direction. They cautioned that the direction of column fall (105 ± 16 degrees) was not necessarily indicative of epicentral direction.

Slow deterioration of the colonnade is likely to result with columns falling in different directions. Aligned fallen columns are found in many earthquake-affected sites (Stiros 1996; Marco 2008; Hinzen et al. 2011; Rodríguez-Pascua et al. 2011; Sintubin 2011) and we propose that the same cause led to similar results in Yavneh. The colonnade’s azimuth is 010-190 degrees and all the columns fell eastward (Figure 5b). The average azimuth of 31 column segments is 105 ± 16 degrees Simulations using strong-motion records of modern earthquakes show only little correlation between falling directions and back azimuth to the wave source (Hinzen 2009, 2011). This requires that the individual columns were connected, possibly with wooden beams that were not preserved, and unified the falling direction. We therefore regard the columns as evidence for earthquake as a trigger for the destruction of the site, but they cannot serve as a reliable indicator for determining the source location.

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Sub-Area A2

Figure 2

Figure 2Area A, plan Yannai (2014) |

|

VIII + | |

| Foundation damage | Sub-Area A2

Figure 2

Figure 2Area A, plan Yannai (2014) |

|

VIII + |

Fischer, M., Taxel, I. (2007). "Ancient Yavneh: Its History and Archaeology." Tel Aviv 34(2): 204.

Langgut, D., et al. (2016). "Resolving a historical earthquake date at Tel Yavneh (central Israel) using pollen seasonality." Palynology 40(2): 145-159.

Neumann, F. H., et al. (2009). "Assessment of the effect of earthquake activity on regional vegetation --

High-resolution pollen study of the Ein Feshka section, Holocene Dead Sea." Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 155(1-2): 42-51.

Taxel, I. (2013). "Rural Settlement Processes in Central Palestine, ca. 640–800 c.e.: The Ramla-Yavneh Region as a Case Study."

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 369: 157 - 199.

Velednizki, N. (2044). "Yavneh" Hadashot Arkheologiyot - Excavations and Surveys in Israel 116.

Yannai, E. (2014). "Excavations at Yavneh." Hadashot Arkheologiyot - Excavations and Surveys in Israel 126.

Yavneh, Yavneh-Yam and Their Neighborhood: Studies in the Archaeology and History of the Judean Coastal Plain (Eretz: Geographic Research & Publications; ed. M. L. Fischer), Tel Aviv 2005

V. Guérin, Description géographique, historique et archéologique de la Palestine, Judée, 1–3, Paris

1868–1869

Y. Aharoni, PEQ 90 (1958), 27–31

B. Mazar, IEJ 10 (1960), 65–77

RB 75 (1968), 381–428;

T. Noy, EI 13 (1977), 290*–291*

J. Neusner, Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II/19/2, Berlin

1979, 3–42

O. Keel et al., Orte und Landschaften der Bibel: ein Handbuch und Studienreisefürer zum Heiligen Land, 1–2, Zürich 1982–1984, 33–37

F. Blanchetiere, MdB 29 (1983), 20–21

Y. Porath, ESI 2 (1983),

50

S. J. D. Cohen, HUCA 55 (1984), 27–53

N. Na’aman, Borders and Districts in Biblical Historiography

(Jerusalem Biblical Studies 4), Jerusalem 1986

Y. Levy, ESI 9 (1989–1990), 61

10 (1991), 170

12 (1994),

113

J. J. Schwartz, Lod (Lydda), Israel: From its Origins Through the Byzantine Period, 5600 B.C.E.–

640 C.E. (BAR/IS 571), Oxford 1991

J. P. Lewis, ABD, 3, New York 1992, 634–637

id., HUCA 70–71

(1999–2000), 233–259

H. Taragan, Cathedra 97 (2000), 180

id., Milestones in the Art and Culture of Egypt

(Assaph Book Series

ed. A. Ovadiah), Tel Aviv 2000, 117–143

S. Weingarten & M. Fischer, ZDPV 116

(2000), 43–56

I. Barash, ESI 113 (2001), 101*

C. Eliaz, ibid. 114 (2002), 115–116*

A. Gorzalczany, ibid.,

72*

BAR 29/3 (2003), 20

P. De Miroschedji, Les “Maquettes architecturales” de l’antiquité (Bibliothèque

archéologique et historique 160

ed. B. Muller), Beiruth 2002

D. Boyarin, Jewish Culture and Society Under

the Christian Roman Empire (Interdisciplinary Studies in Ancient Culture and Religion 3), Leuven 2003,

285–318

R. Kletter, Welt und Umwelt der Bibel 30/4 (2003), 58–59

id., ASOR Annual Meeting 2004, www.

asor.org/AM/am.htm

id., ESI 116 (2004), 45*–46*

id., Yavneh: An Early Cemetery and Other Remains, ESI

(in prep.)

H. Shanks, BAR 30/6 (2004), 47–51

N. Velednizki, ESI 116 (2004), 47*

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master Tel Yavne kmz file | various> |