Tall al-'Umaryi

Aerial shot of fortress at Tall al-'Umayri

Aerial shot of fortress at Tall al-'UmayriClick on image to open a high res magnifiable image in a new tab

Credit: Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East

Photographer: Robert Howard Bewley

Reference: APAAME_20160928_RHB-0058.jpg

Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommerical-No Derivative Works

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Tall al-'Umaryi | Arabic | |

| Tel El 'Umeiri | Arabic | |

| Tel Al Umaryi | Arabic | |

| Tell Al Umayri | Arabic | |

| el-'Ameireh | Arabic |

- from Chat GPT 5.2, 14 February 2026

- sources: Wikipedia; Bramlett (2008)

Excavations conducted by the Madaba Plains Project have revealed a long occupational sequence extending from the Early Bronze Age through the Hellenistic period (Wikipedia). Stratified architectural remains, destruction layers, and material culture from multiple phases illustrate the shifting political, economic, and settlement patterns of the southern Levant.

In the Late Bronze Age, sites such as Tall al-ʿUmayri formed part of the highland zone situated between Egyptian-controlled lowlands and the more loosely organized pastoral and agrarian populations of the Transjordanian interior. The highlands functioned as a frontier landscape, where local communities adapted to changing imperial pressures, shifting trade routes, and fluctuating political control.

Through time, Tall al-ʿUmayri developed into a fortified settlement with substantial stone architecture and evidence for repeated cycles of construction, destruction, and rebuilding.

A few explorers in the 19th century visited the region of Tell el-'Umeiri. Warren (1869: 291) was among the first, in 1867, noting that "Amary" is the name of the district as well as three ruins in it. Conder (1889: 19), while unable to locate the spring, did visit the region, and also referred to three tells in connection with "el 'Ameireh." Most explorers, however, missed the region, probably because it was not (until recently) near a main thoroughfare and because the other hills surround ing Tell el-'Umeiri obscured its importance.

Motivated by a desire to discover the ancient borders of Ammon, four German scholars explored the region to the west (Gese 1958) south west (Hentschke 1960; Fohrer 1961) and south (Reventlow 1963) of Amman in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Among their discoveries was a series of Grenzfestungen or boundary forts, which they believed represented the ancient western border of Ammon. Typically these forts consisted of a rectangular building with an adjacent watchtower. The present report holds that many of these watch tower sites were not, however, defense installations, but farmsteads.

The first thorough description of the site resulted from the Tell Hesban regional survey of 1976 (Ibach 1978: 209). Tell el-'Umeiri (West), Site 149, was noted as a major site of 16 acres with a spring, considerable evidence of architecture, and huge quantities of sherds. The sherds ranged from the Chalcolithic Age through Iron II with most intervening periods represented (Ibach 1978: 209). Tell el-'Umeiri (East), Site 150, was described as a medium site with even more visible architecture, caves, and cisterns; its pottery ranged from the Iron Age through Umayyad and included Roman and Byzantine. A third 'Umeiri was noted to the north of these sites and contained mainly medieval Mamluk ruins.

Von Rabenau (1978) appears only to have been concerned with Site 150. During a two month survey in 1979, Franken, with four others, completed the most thorough investigation to that date. Franken concluded that "from the archaeological remains and objects found, tell Emairi and its immediate surroundings seem to reflect nearly the entire cultural history of the country" (Franken and Abujaber 1979: 1). Dividing his findings into four "cycles" (Neolithic through Early Bronze, Middle Bronze through Iron Age, Roman through Islamic periods, and 1850 to the present), he advocated urgent investigation not only of the promising tell but also of the rural landscape with its agricultural installations, cemeteries, and water sources (Franken and Abujaber 1979: 61).

In 1981 Redford visited the 'Umeiri region during a three-week survey in which he sought to identify Nos. 89-101 of Thutmose III's list of Asiatic toponyms with a series of sites in Trans jordan. After sherding Tell el-'Umeiri (West) and studying its topography, Redford concluded that it "fulfills all the criteria posed by Nos. 95-96 in Thutmose III's list. It has the largest perennial spring anywhere in the vicinity; it was occupied during MB/LB, and is in a strategic location on a transit corridor of easy passage. . . . The evidence thus seems strong that cyn/krmn, or the Abel Keramim of the Bible, is indeed to be sought at the site of 'Umeiri west" (Redford 1982: 69-70). Finally, Abujaber (1984), 'Umeiri's landowner, completed his own research on the development of agriculture in the region during the 19th century, a development to which his own forebears contributed substantially.

- Figure 1 - Location Map

from Geraty et al. (1986)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Central Jordan. Tell el-'Umeiri is located on the northern edge of the Madaba Plains in the foothills surrounding Amman.

Geraty et al. (1986)

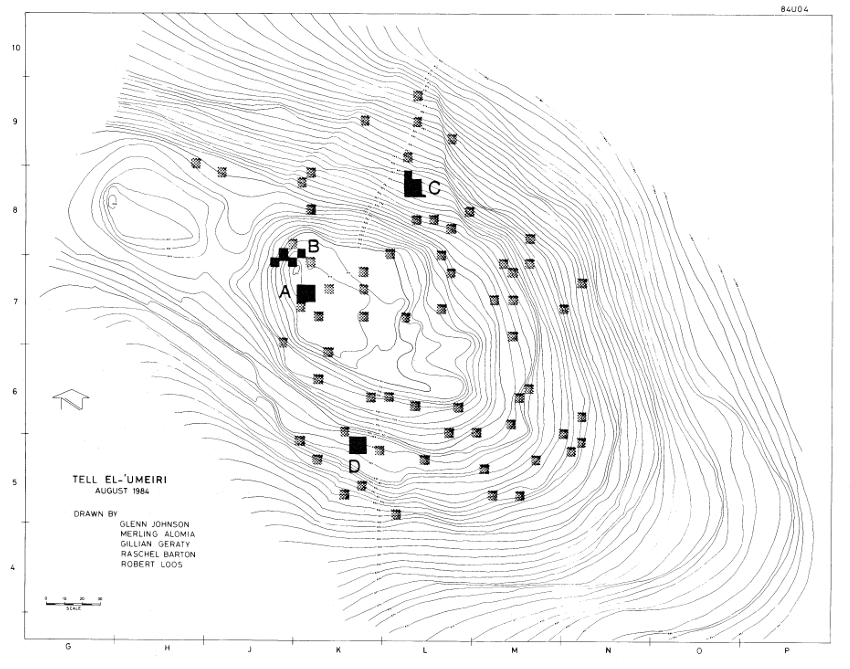

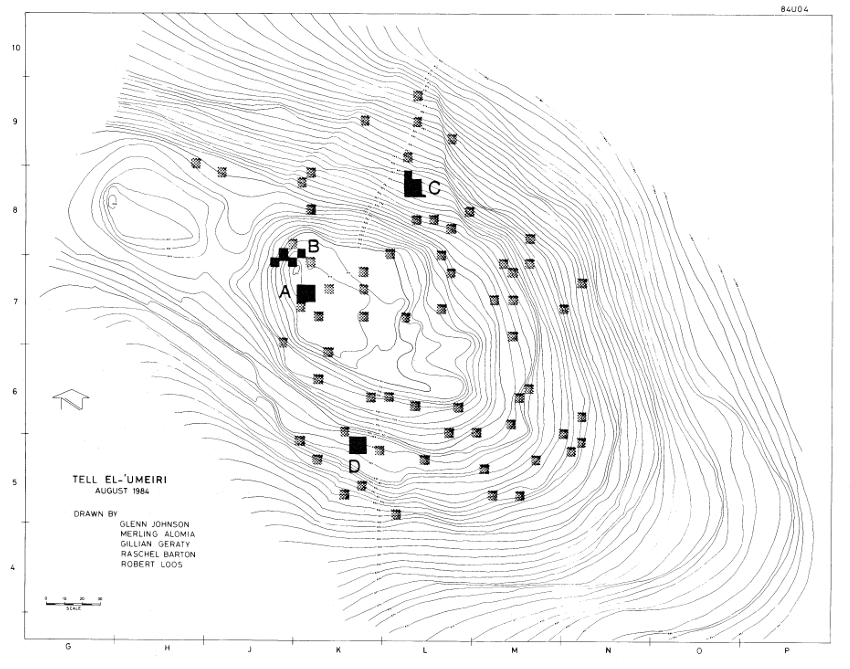

- Topographic Map with

excavation areas from Herr et al. (2009)

Topographic Map of Tall al-'Umayri with the fields of excavation as of the 2008 season.

Topographic Map of Tall al-'Umayri with the fields of excavation as of the 2008 season.

Herr et al. (2009) - Figure 2.1 - Topographic

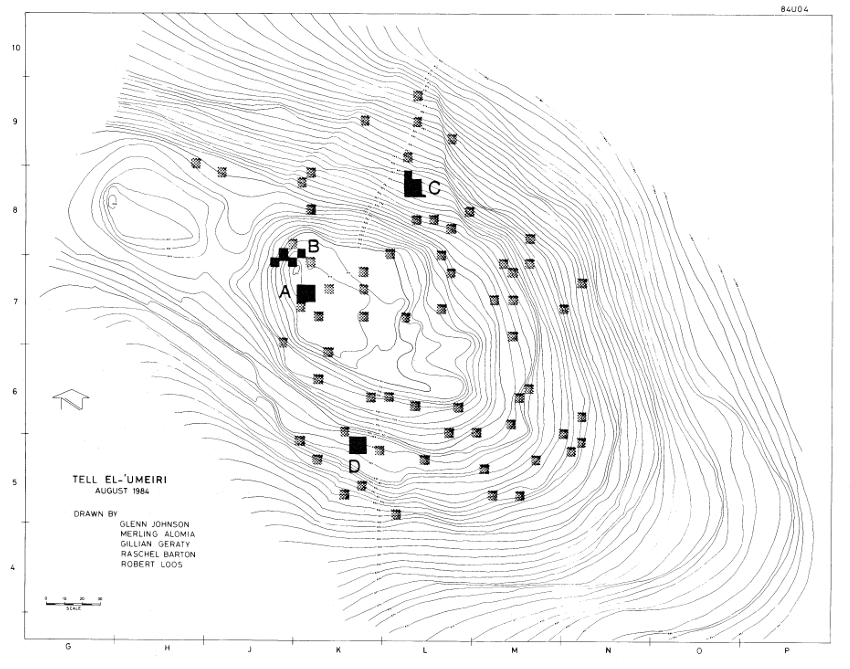

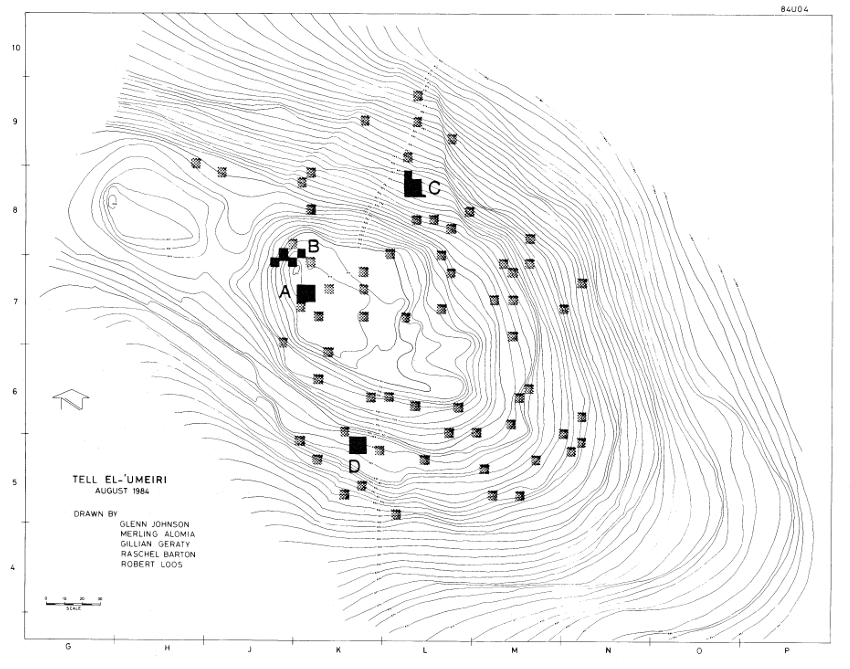

Map with excavation areas from Herr et al. (2014)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Topographic map of Tall al-‘Umayri and the cumulative fields of excavation including the 1984 to 1998 seasons.

Herr et al. (2014) - Figure 6 - Topographic Map

with excavation areas from Geraty et al. (1986)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Central Jordan. Tell el-'Umeiri is located on the northern edge of the Madaba Plains in the foothills surrounding Amman.

Geraty et al. (1986)

- Topographic Map with

excavation areas from Herr et al. (2009)

Topographic Map of Tall al-'Umayri with the fields of excavation as of the 2008 season.

Topographic Map of Tall al-'Umayri with the fields of excavation as of the 2008 season.

Herr et al. (2009) - Figure 2.1 - Topographic

Map with excavation areas from Herr et al. (2014)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Topographic map of Tall al-‘Umayri and the cumulative fields of excavation including the 1984 to 1998 seasons.

Herr et al. (2014) - Figure 6 - Topographic Map

with excavation areas from Geraty et al. (1986)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Central Jordan. Tell el-'Umeiri is located on the northern edge of the Madaba Plains in the foothills surrounding Amman.

Geraty et al. (1986)

- Fig. 4.1c Plan of Building C from Bramlett (2008)

- Fig. 4.1c Plan of Building C from Bramlett (2008)

- Fig. 16.3 Plan of

FP-6 walls from Clark (1989)

Fig. 16.3

Fig. 16.3

Plan of FP-6 walls

Clark (1989) - Figure 4.1 - Plan of

Square layout for Field B from Herr et al. (2014)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Field B: Square Layout, 1984-1998

Herr et al. (2014)

- Fig. 16.3 Plan of

FP-6 walls from Clark (1989)

Fig. 16.3

Fig. 16.3

Plan of FP-6 walls

Clark (1989) - Figure 4.1 - Plan of

Square layout for Field B from Herr et al. (2014)

Fig. 4.1

Fig. 4.1

Field B: Square Layout, 1984-1998

Herr et al. (2014)

- Fig. 16.3 Fields A (Phase 13),

B (Phase 11), and H (Phase 9) from Herr et al. (1999)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Tall al-`Umayri, Fields A (Phase 13), B (Phase 11), and H (Phase 9): Plan of the early Iron I perimeter wall as we re-construct its plan at the western edge of the site.

Herr et al. (1999) - Figure 2.2 - Plan of

Square layout for Fields A, B, and H from Herr et al. (2014)

Fig. 2.2

Fig. 2.2

Plan of Square layout for Fields A, B, and H.

Herr et al. (2014)

- Fig. 16.3 Fields A

(Phase 13), B (Phase 11), and H (Phase 9) from Herr et al. (1999

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Tall al-`Umayri, Fields A (Phase 13), B (Phase 11), and H (Phase 9): Plan of the early Iron I perimeter wall as we re-construct its plan at the western edge of the site.

Herr et al. (1999) - Figure 2.2 - Plan of

Square layout for Fields A, B, and H from Herr et al. (2014)

Fig. 2.2

Fig. 2.2

Plan of Square layout for Fields A, B, and H.

Herr et al. (2014)

- Isometric drawing of

the Late Bronze building from Herr and Clark (2009)

This computerized isometric drawing shows the layout of the Late Bronze building,

which includes two southern rooms (1 and 2), an entry hall (4), a large central room (3), and a back room (5)

along the western side of the building. A small photo of the cultic shrine is set in its niche in room 3.

This computerized isometric drawing shows the layout of the Late Bronze building,

which includes two southern rooms (1 and 2), an entry hall (4), a large central room (3), and a back room (5)

along the western side of the building. A small photo of the cultic shrine is set in its niche in room 3.

Illustration courtesy of Kent Bramlett

Herr and Clark (2009) - Artist's cut-away

reconstruction of the Late Bronze building from Herr and Clark (2009)

Artist's cut-away reconstruction of the Late Bronze Age building.

One entered the building from the east through a stepped threshold lined with orthostats.

Visitors could either ascend the stone stairs to the second story or take one of two short

sets of stairs leading down into Room 4.

Artist's cut-away reconstruction of the Late Bronze Age building.

One entered the building from the east through a stepped threshold lined with orthostats.

Visitors could either ascend the stone stairs to the second story or take one of two short

sets of stairs leading down into Room 4.

Rhonda Root, artist

Herr and Clark (2009)

- Isometric drawing of

the Late Bronze building from Herr and Clark (2009)

This computerized isometric drawing shows the layout of the Late Bronze building,

which includes two southern rooms (1 and 2), an entry hall (4), a large central room (3), and a back room (5)

along the western side of the building. A small photo of the cultic shrine is set in its niche in room 3.

This computerized isometric drawing shows the layout of the Late Bronze building,

which includes two southern rooms (1 and 2), an entry hall (4), a large central room (3), and a back room (5)

along the western side of the building. A small photo of the cultic shrine is set in its niche in room 3.

Illustration courtesy of Kent Bramlett

Herr and Clark (2009) - Artist's cut-away

reconstruction of the Late Bronze building from Herr and Clark (2009)

Artist's cut-away reconstruction of the Late Bronze Age building.

One entered the building from the east through a stepped threshold lined with orthostats.

Visitors could either ascend the stone stairs to the second story or take one of two short

sets of stairs leading down into Room 4.

Artist's cut-away reconstruction of the Late Bronze Age building.

One entered the building from the east through a stepped threshold lined with orthostats.

Visitors could either ascend the stone stairs to the second story or take one of two short

sets of stairs leading down into Room 4.

Rhonda Root, artist

Herr and Clark (2009)

- Monumental Building with

earthquake damage from Herr et al. (2009)

This monumental building, viewed from the east, may have been a temple. At the bottom

of the photo is a monumental entrance with a series of stairs leading down to the entrance room and another

series leading up to what must have been the second floor. Everything shows signs of

having been destroyed by an earthquake. Some of the surviving walls of the structure are almost 3 meters (10 feet) high.

This monumental building, viewed from the east, may have been a temple. At the bottom

of the photo is a monumental entrance with a series of stairs leading down to the entrance room and another

series leading up to what must have been the second floor. Everything shows signs of

having been destroyed by an earthquake. Some of the surviving walls of the structure are almost 3 meters (10 feet) high.

Herr et al. (2009) - Wall fragments of the

MB IIC period from Herr et al. (2009)

Wall fragments of the MB IIC period are visible at the bottom of this photo. The very large boulders

almost qualify as "Cyclopean" masonry, a typical feature of Middle Bronze Age architecture. A lime-coated surface runs up to the wall stones.

Wall fragments of the MB IIC period are visible at the bottom of this photo. The very large boulders

almost qualify as "Cyclopean" masonry, a typical feature of Middle Bronze Age architecture. A lime-coated surface runs up to the wall stones.

Herr et al. (2009) - Fig. 16.4 Area B Field Phase 6

Beaten earth rampart with stabilizing wall from Clark (1989)

Fig. 16.4

Fig. 16.4

Beaten earth rampart with stabilizing wall

JW:Area B Field Phase 6

Clark (1989) - Fig. 4.6 Entry an Stairs of Building C from Bramlett (2008)

- Monumental Building with

earthquake damage from Herr et al. (2009)

This monumental building, viewed from the east, may have been a temple. At the bottom

of the photo is a monumental entrance with a series of stairs leading down to the entrance room and another

series leading up to what must have been the second floor. Everything shows signs of

having been destroyed by an earthquake. Some of the surviving walls of the structure are almost 3 meters (10 feet) high.

This monumental building, viewed from the east, may have been a temple. At the bottom

of the photo is a monumental entrance with a series of stairs leading down to the entrance room and another

series leading up to what must have been the second floor. Everything shows signs of

having been destroyed by an earthquake. Some of the surviving walls of the structure are almost 3 meters (10 feet) high.

Herr et al. (2009) - Wall fragments of the

MB IIC period from Herr et al. (2009)

Wall fragments of the MB IIC period are visible at the bottom of this photo. The very large boulders

almost qualify as "Cyclopean" masonry, a typical feature of Middle Bronze Age architecture. A lime-coated surface runs up to the wall stones.

Wall fragments of the MB IIC period are visible at the bottom of this photo. The very large boulders

almost qualify as "Cyclopean" masonry, a typical feature of Middle Bronze Age architecture. A lime-coated surface runs up to the wall stones.

Herr et al. (2009) - Fig. 16.4 Area B Field Phase 6

Beaten earth rampart with stabilizing wall from Clark (1989)

Fig. 16.4

Fig. 16.4

Beaten earth rampart with stabilizing wall

JW:Area B Field Phase 6

Clark (1989) - Fig. 4.6 Entry an Stairs of Building C from Bramlett (2008)

This chart is an attempt to establish a site-wide stratification. However, none of the connections are certain between the fields, except some of those between Fields A and B, and A and H which are adjacent to one another. We have tried to avoid phase proliferation by suggesting connections if there is no evidence to support them. A question mark beside a phase number indicates that the attribution is correct for the sequence and chronological period, but we are very uncertain to which integrated phase it should be applied. Usually, the least certainty occurs in those fields outside the acropolis, such as Fields C, E, and F. The abbreviation “shds” stands for “sherds;” “Tr” stands for the trench excavated in Field G (Fisher 1997a).

Information for some of the EB attributions has come from T. Harrison who is working on the final publication of the EB material. The assignment of FP 10 in Field C, carvings in bedrock, to IP 24 is far from certain. It is simply earlier than the other EB 3 phases in Field C.

IPs 24-21 were determined by the architecturally differentiated EB 3 phases in Field D. Pottery assemblages were generally not specific enough to help separate the earth layers with confidence. The phasing in Field C is clear, but its equation with the phases of Field D is speculative, based on the room in Square 8L63 (Field C, FP 8), which was similar to those in Field D, FP 5. The same is true of the Field G remains: because bedrock was not reached there and because smashed pots were found, we simply equated the top two EB 3 phases with the two most significant upper occupational phases in Field D, which also had smashed vessels.

The two MB 2C phases (IPs 18-17) were clearly separated in Field C. Although we have found only one MB 2C phase in Field B, the pottery in the rampart infers two original phases. While the rampart dated to MB 2C, the pottery within the rampart was also MB 2C, indicating an earlier settlement for the origin of the pottery. We have thus equated the construction of the Field B rampart with the later MB phase in Field C. The MB evidence from Fields F and G could be from either phase.

The strongest evidence for IP 16 (LB 2, based on the pottery) was found in a major new building in Field B (FP 13) with minor deposits in Fields A and F where we encountered extra-urban earth layers.

The interrelationships of the early stages of the Iron 1 period, IPs 15 to 13, are very good for Fields A and B, both of which have three distinct phases of occupation; the second one was massively destroyed. In Field F, only one phase was inside the city, while the separation into two phases is connected with an apparent extra-urban terrace wall. The remains from Field E have simply been attributed to both IPs 14 and 13 because of their general ceramic date.

As for IPs 12to 11, the storeroom in Field B and the walls in Field A were clearly above the remains of IPs 13 and 14. But because these are the only in-situ architectural deposits from the late Iron 1 and/or early Iron 2 periods so far discovered on the mound, we feel relatively certain the remains from Field E (FP 7) at least overlapped them.

The determination of late Iron 2/Persian IPs 10-6 is based on the stratification of Fields A and B, although stratigraphic connections between the fields are not always direct even within Field A (thus we have had to use a subset of phase numbers with “N” for “north” for some deposits). However, both Fields A and B have the same number of phases with similar relationships to earlier and later phases. The earliest phase in both fields is made up of pits (Field B) and small, weak installations (Field A), suggesting a poor settlement of newcomers. The last phase was that into which the Early Roman ritual bath was dug in both fields. However, it is possible that the intervening phases could have been isolated reconstructions limited to individual structures. The phasing of Field H equates with the main phases of Field A. Although also containing the same number of phases as Fields A and B except for one, the upper phases in Field F seem to be extra-urban in nature and probably had a separate history. The attribution of phases in Field C is guesswork, based on their general ceramic date and sequence. All the late Iron 2/Persian materials from Field E, discerned only in three phases, have been connected with tell phases with great uncertain ty; presumably, the water source would have been used throughout.

The early Roman ritual bath straddling Fields A and B makes a clear connection for IP 4. Later phases have been connected based on general ceramic date.

After a hiatus during the early stages of the Middle Bronze Age, a major settlement was again established. The initial one (Stratum 16) was built on the ridge top and soon grew larger so that houses were constructed on the northern slope in Field C. So far, in situ remains have been found only in this location. Until now, very little could be said about the identity of the people who settled our site. Only rarely do settlers tell us who they were through inscriptions or other identifying features. Based on evidence from many sites and finds in the southern Levant dating to the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, these newcomers may have been what the Bible and other texts refer to as "Canaanites."

Much more prominent was Stratum 15. At some point the inhabitants fortified the site by creating a hill out of the original ridge. In Field B, where the site joined the higher ridge to the west, they dug a north-to-south dry moat five meters deep across the ridge at the western edge of the settlement and then piled up layers of earth and crushed limestone to create a steep rampart climbing up another five meters for a total of ten meters from the bottom of the moat to the top of the rampart. The earth within the rampart contained MB IIC pottery from the Stratum 16 settlement. There does not seem to have been a wall at the top of the rampart at the location of our section. A small portion of the same rampart seems to have been discovered at the top of the northern slope just outside the Stratum 14 (Late Bronze Age) palace/temple. These fortifications transformed the appearance of the site, creating the modern hill-like shape we see today.

Nestled inside the newly fortified settlement (looking much like a crater) was the contemporary town. Our project has so far discovered two locations in Field B where fragmentary MB IIC walls were found. One was made up of two wall fragments constructed of relatively large boulders (a typical feature of many Middle Bronze sites) and was undoubtedly part of a major building, while the other had three walls supporting a plastered pool, one of the earliest constructed water installations inside a site so far discovered in Jordan. The latter construction was situated on top of the rampart. Both sets of walls may have belonged to a large tower or palatial building at the northwest corner of the site, probably the highest spot at the time.

Extra-urban domestic remains were discovered on the northern slope of the site in Field C (a surface and a fragmentary wall) above the Stratum 16 remains (Battenfield 1991: 75).

The pottery associated with all these features was typical of MB IIC assemblages and included "chocolate-on-white" ware, which also continued into LB I.

A cave tomb, with multiple burials and several MB IIC pottery vessels, was found near the dolmen at the southeastern base of the site in Field K (Gorniak and Kapica 2002). This tomb is still visible.

Although the rare potsherd is found now and then from the first half of the Late Bronze Age, we have not yet discovered any certain architectural features from this time period. We thus tentatively suggest a hiatus.

Stratum 14 reflects `Umayri's settlement during the Late Bronze Age II, so far excavated only in Field F, the eastern portion of the tell, and Field B in the northwestern corner of the site. Thus, the extant evidence demonstrates a Late Bronze occupation at `Umayri that may have made use of the entire 1.4 hectare area of the top of the site, probably that area encompassed by the MB IIC rampart.

Field F produced a series of four arbitrarily defined LB II debris layers overlying a Middle Bronze Age structure that was exposed in only one square (6M90) and consisted of remains of a few walls and earth layers, possibly a terrace wall (Low 1997: 191-95). The Late Bronze layers contained mixed remains from domestic, cultic, and economic spheres of life, including two joining pieces of a plaque figurine, often identified with fertility goddesses such as Asherah or Astarte.

The other source of information from the Late Bronze Age on the site comprises a very well-preserved monumental building in Field B, atop the relatively well defined MB IIC remains of Stratum 15. Because it is an important structure for the archaeology of Jordan, and because it has not been published before, we will describe it in some detail. Built directly into and over the interior portions of the Middle Bronze rampart in the northwest corner of the site, this building emerged over six excavation seasons. Because the walls stood over two meters high in places, it took our team parts of three seasons to excavate any given room to the floor. The site's inhabitants utilized not only the Middle Bronze rampart layers sloping toward the center of the city on which to found the building, but also the two-meter-thick walls of a Middle Bronze tower built at the northwest corner of the site.

The building consisted of five rooms with two floors. Both phases utilized the same architectural elements of the building, albeit with slight variations. A plan of the building reveals the rooms—two on the southern side (Rooms 1 and 2), an entry hall (Room 4), a large central room (Room 3), and a back room along the western side of the building (Room 5).

The exterior dimensions of the building are clear. It is basically rectangular in shape with exterior measurements of 12 by 16 meters. The walls are bonded throughout, except those abutting the northern and western exterior walls, and consist predominantly of semi-hewn small-to medium-sized boulders, making the construction of the walls unique for the site. The interior wall between Rooms 3 and 5 was of mixed construction, made up of both small boulders and mudbricks. Exterior walls measured 1.5 meters in thickness, with the exception of the western wall of Room 5, which consisted of the two-meter-thick external "tower" wall of Stratum 15, and those on the interior between 1 and 1.2 meters thick.

One curious feature is the two parallel walls forming the eastern side of the building, set cheek-by-jowl next to each other. Only during the last season did the obvious explanation appear to us: the inner (western) of the two walls is actually a "stair wall." That is, the stairs preserved farther to the north would have continued upwards on top of this wall to the second floor or the roof. Thus the eastern wall, made of larger stones, is actually the outer wall of the structure.

While for the most part these walls were preserved over two meters high in places, the mixed-construction wall between Rooms 3 and 5 appears only to have been built to its surviving height of just over one meter. It seems clear from the destruction debris in all five rooms that the structure once supported a second story over at least portions of it. Massive amounts of mudbricks from the upper walls and mud from the ceilings, second story flooring, and roofing detritus filled every room, with burned remains of large support beams especially concentrated in Room 3. Added to this evidence for another floor to the building is the stairway on the eastern side of Room 4 leading upward. Indeed, the stairway seems to have continued for a considerable distance on top of the eastern wall of Room 1. There has been some debate about whether Room 3 might have supported a second story, given the wide span between load-bearing walls. Unfortunately, the surviving evidence is of limited value in this regard, but, as the painting on p. 77 makes clear, we tend to think it was a single story, perhaps with a higher ceiling.

One entered the building from the east through a stepped threshold 1.5 meters wide, lined in places with orthostatic stones (flat stones placed on edge). One went up a few steps and then down again to a small paved platform located roughly in the center of the stairway wall of Room 4. At this juncture, those entering could choose to turn left, ascending the stone stairs, we assume, to the second story. On the other hand, the platform also connected to stairs leading down to the right into Room 4. A third option presented itself with at least two steps leading directly down into this room.

Room 4 measured nearly eight meters long and over two meters wide. Doorways were built into three of this room's walls—the 1.5 meter-wide entry on the east, a 1.2 meter-wide door into Room 1 on the south, and two 1.2 meter-wide doors in the western wall, providing access to Room 3. The southern of the two doors was used throughout the building's occupation, but the northern one fell out of use during the second phase, and the owners filled it in with stones. Given the construction of the entryway and span between the walls, it does not seem likely that there was a second story above Room 4. On the floor of the room lay hundreds of bones and two large, flat stones that may have been standing stones used in ritual activities. This, along with broken ascending stairs in the room and the separation of rows in the eastern exterior wall, testifies to an earthquake as the cause of the building's destruction, though this quake may have occurred at the end of Stratum 13 (below).

Rooms 1 and 2 were entered through the southern doorway of Room 4. Occupying about one third of the floor space of the building, their combined thirty-one-square-meter floor area revealed multiple lenses of use surfaces. The walls were all bonded and preserved to more than two meters high. The western wall of Room 2 seems to have used an earlier MB IIC mudbrick wall. Otherwise, besides the evidence of a fiery end for the burned bricks, there was nothing found on the floors in the room to suggest a function. The size of the room, the massive amount of fallen bricky debris (accumulating over two meters thick), and the stairway in Room 4 are persuasive evidence of a second story at least above Rooms 2 and 3.

Room 3, accessed through the doorway (s) in the wall between Rooms 4 and 3, yielded the most exciting discoveries in the building. These finds also contribute to our understanding of the building's function. Encompassing twenty-eight square meters of floor space, its walls were mostly of stone, with extensive evidence of mud plaster covering the stones. But the western, "installation wall" (Bramlett 2008) consisted of mudbrick as well as stone, and originally likely stood only one meter or so high.

Toward the southern end of this wall the ancients had installed, approximately 0.6 meters above the floor, a plastered niche measuring 1.6 meters wide, 0.6 meters high and 0.4 meters deep. It housed five natural standing stones embedded in plaster together with several ceramic artifacts including two carinated bowls, a chalice, parts of four lamps, and two crudely made, unfired figurines. The five stones embedded in the plaster of the niche included a large central aniconic stone in a dome-like shape, flanked on the left by a small, disc-shaped stone and one that looked like a human foot. On the right were a head-shaped stone and then a smaller chert nodule which, with its natural calcareous accretions, gave the appearance of a face with an open eye. Placed on the floor in front of the niche were a flanged presentation altar and small offering table, both made of mudbricks plastered on the exterior surfaces. Near them, beside the entry door, was found an additional lamp. Along the eastern wall, what were probably bench stones were also discovered in Room 3. The floor of almost the complete room was covered with hundreds of bones from domestic animals. The bones showed no signs of burning.

Behind the "cultic wall" of Room 3 was another space, Room 5. Bounded by the Middle Bronze "tower wall" on the west, a short wall on the south, a segment of the northern wall, and the "cultic wall" on the east, it was rectangular in shape, measuring 4.3 meters long and 2.1 meters across. Its floor level was more than one meter above that of Room 3, likely due to the rising Middle Bronze rampart beneath. There appears to be no point of entry into the space. The room produced fifteen handmade, poorly fired ceramic figurines and three nearly complete ceramic vessels—a goblet, a dipper juglet, and one small jar.

Given the combined floor space of Rooms 3 and 5, it is highly unlikely that a second story existed over them. If, as we have proposed, the wall between the two rooms was less than two meters high and thus not load bearing, the span would be too great to support another construction level. But there were at least two phases of use, the second marked by the blockage of the northern doorway in the eastern wall of Room 3 and a use surface approximately ten to twelve centimeters above the original level.

The architectural and artifactual evidence seems to suggest a palatial and certainly a cultic function. The size and construction of walls and the floor plan rule out a primarily domestic function. Was the main purpose of the structure religious or political, if the two can be separated completely? Rooms 1 and 2 have given up little evidence to help us make this distinction. Room 4 was clearly an entry hall, which might fit either palace or temple architecture, but the two "standing stones" definitely suggest a religious aspect to the room. But how should we interpret Rooms 3 and 5? Do they represent the cultic component of a palatial facility or do they reflect the central purpose of the structure as a temple with an entry hall and two large side chambers?

Kent Bramlett's University of Toronto Ph.D. dissertation (2008) on the building in its archaeological and historical context argues cautiously but strongly for identifying this structure as a temple and cites comparative evidence from the Levant, especially from Israel/Palestine and Jordan. The cultic function of Room 3, central to the building's spatial features, along with the function of Room 5 as a probable vestry or favissa for storing unused (or no longer usable) cultic artifacts, certainly gives pride of place to this interpretation.

Bramlett also treats contemporary Late Bronze Age settlements in the region, reconstructing in the process proposed lines of commerce and communication as well as political ties (2008: 55-113). From the archaeological evidence, he posits a string of sites scattered along highland trade routes which served an important role in Late Bronze commerce in Transjordan. The small cluster of sites in central Jordan, including Sahab, Amman, Umm ad-Dananir, Safut, and `Umayri, were close enough in proximity to each other to have formed a city-state form of polity. As part of this city-state system, `Umayri and its fortunes diminished toward the beginning of the thirteenth century at about the time of increasing Egyptian influence in the region, influence that favored Amman and Sahab (Bramlett 2008: 269-70).

Following the collapse of the LB II temple and its associated settlement, there was a fundamental change in the nature of the settlement. Gone are palatial buildings associated with activities of the elite classes of society; gone are fertility figurines of Asherah and cultic shrines; and gone are pottery forms solidly at home in the Late Bronze Age. Newly arrived are houses and finds very similar to the earliest stages of the Iron I settlement sites west of the Jordan River; pottery forms that anticipate those found at the scores of Iron I settlement sites throughout the southern Levant; and modest religious expressions in the form of crude standing stones and ceramic model shrines. One can compare the finds best with the settlement of diverse tribal groups, probably a very similar settlement pattern as that noted for highland sites west of the Jordan River (Faust 2006).

The inhabitants of 'Umayri built their settlement, but before they could live there very long an earthquake seriously jolted the settlement around 1200 B.C.E. We have very few architectural remains from this stratum, but we know their cultural remains from the debris taken from their structures for subsequent reuse in the reconstruction of the severely damaged western defensive rampart system, which, until the earthquake, was still in use from its initial founding in Stratum 15 (MBA). Thus, at this point in the excavation of'Umayri, we can speak only of some kind of occupation (Stratum 13) whose earthquake damage provided the raw materials for rebuilding parts of 'Umayri in the subsequent, spectacularly preserved Stratum 12.

It may have been this earthquake that damaged the walls of Stratum 14 (above). We found no signs of occupation above the Late Bronze Age building in either Stratum 13 or 12, even though it was out of use since the end of Stratum 14. The pottery from Stratum 13 is virtually like that of the following one, except there were fewer Iron I forms and more Late Bronze ones, which suggests the tail end of the Late Bronze Age.

Fig. 2.3

Fig. 2.3Cumulative Integrated Phasing (IP) Chart.

Herr et al. (2014)

This chart is an attempt to establish a site-wide stratification. However, none of the connections are certain between the fields, except some of those between Fields A and B, and A and H which are adjacent to one another. We have tried to avoid phase proliferation by suggesting connections if there is no evidence to support them. A question mark beside a phase number indicates that the attribution is correct for the sequence and chronological period, but we are very uncertain to which integrated phase it should be applied. Usually, the least certainty occurs in those fields outside the acropolis, such as Fields C, E, and F. The abbreviation “shds” stands for “sherds;” “Tr” stands for the trench excavated in Field G (Fisher 1997a).

Information for some of the EB attributions has come from T. Harrison who is working on the final publication of the EB material. The assignment of FP 10 in Field C, carvings in bedrock, to IP 24 is far from certain. It is simply earlier than the other EB 3 phases in Field C.

IPs 24-21 were determined by the architecturally differentiated EB 3 phases in Field D. Pottery assemblages were generally not specific enough to help separate the earth layers with confidence. The phasing in Field C is clear, but its equation with the phases of Field D is speculative, based on the room in Square 8L63 (Field C, FP 8), which was similar to those in Field D, FP 5. The same is true of the Field G remains: because bedrock was not reached there and because smashed pots were found, we simply equated the top two EB 3 phases with the two most significant upper occupational phases in Field D, which also had smashed vessels.

The two MB 2C phases (IPs 18-17) were clearly separated in Field C. Although we have found only one MB 2C phase in Field B, the pottery in the rampart infers two original phases. While the rampart dated to MB 2C, the pottery within the rampart was also MB 2C, indicating an earlier settlement for the origin of the pottery. We have thus equated the construction of the Field B rampart with the later MB phase in Field C. The MB evidence from Fields F and G could be from either phase.

The strongest evidence for IP 16 (LB 2, based on the pottery) was found in a major new building in Field B (FP 13) with minor deposits in Fields A and F where we encountered extra-urban earth layers.

The interrelationships of the early stages of the Iron 1 period, IPs 15 to 13, are very good for Fields A and B, both of which have three distinct phases of occupation; the second one was massively destroyed. In Field F, only one phase was inside the city, while the separation into two phases is connected with an apparent extra-urban terrace wall. The remains from Field E have simply been attributed to both IPs 14 and 13 because of their general ceramic date.

As for IPs 12to 11, the storeroom in Field B and the walls in Field A were clearly above the remains of IPs 13 and 14. But because these are the only in-situ architectural deposits from the late Iron 1 and/or early Iron 2 periods so far discovered on the mound, we feel relatively certain the remains from Field E (FP 7) at least overlapped them.

The determination of late Iron 2/Persian IPs 10-6 is based on the stratification of Fields A and B, although stratigraphic connections between the fields are not always direct even within Field A (thus we have had to use a subset of phase numbers with “N” for “north” for some deposits). However, both Fields A and B have the same number of phases with similar relationships to earlier and later phases. The earliest phase in both fields is made up of pits (Field B) and small, weak installations (Field A), suggesting a poor settlement of newcomers. The last phase was that into which the Early Roman ritual bath was dug in both fields. However, it is possible that the intervening phases could have been isolated reconstructions limited to individual structures. The phasing of Field H equates with the main phases of Field A. Although also containing the same number of phases as Fields A and B except for one, the upper phases in Field F seem to be extra-urban in nature and probably had a separate history. The attribution of phases in Field C is guesswork, based on their general ceramic date and sequence. All the late Iron 2/Persian materials from Field E, discerned only in three phases, have been connected with tell phases with great uncertain ty; presumably, the water source would have been used throughout.

The early Roman ritual bath straddling Fields A and B makes a clear connection for IP 4. Later phases have been connected based on general ceramic date.

The five broad cycles of intensification and abatement in our region have been outlined elsewhere (Herr 1991). Tall al-‘Umayri (West) was occupied by urban settlements during Cycles 1 and 2 (Bronze and Iron Ages), but, as can be seen from the stratigraphic summary chart above, indications of non- or partial-occupational activities from the other cycles have been uncovered. The evidence unearthed by the 1984 random surface survey (Herr 1989c) and seven seasons of excavation suggests a steadily shrinking settlement. From a maximum size in EB 3 each subsequent settlement gradually diminished in size to a minimum, possibly during the Late Bronze Age, but also during the Persian period at the end of the major occupational history of the site. However, the economic and social strategies of the inhabitants do not seem to have followed the same general pattern of degeneration. Indeed, the greatest prosperity and highest degree of job specialization probably occurred while the site was near its smallest size during late Iron 2, a time of complex settlement systems in the region when our site seems to have been focused on administrative activities.

The following discussion is a synthesis of the data discovered during the past seven seasons of excavation seen in the light of the cyclic pattern of regional history we have earlier outlined (Herr 1991). It is also intended to amplify the stratigraphic summary chart above. We can now be quite precise about the specific periods of occupation, and how long they lasted. For instance, it is now clear that there was not a continuous intensification process for the Iron Age (Herr 1991: 11-12). The first intensification in early Iron 1 stopped abruptly in the early to mid 12th century, sputtered to life briefly in the 11th-10th centuries and again in the 9th and 8th centuries, and came on strong in the 6th and 5th centuries. Also, during Regional Cycle 1 (the Bronze Age), ‘Umayri saw two sub-cycles:

- an intensification during EB 1-3 and an abatement during EB 4

- another intensification and abatement during MB 2C

After an apparent absence of settlement at the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, a major new structure was built in Field B. It lay above and to the north of some of the MB 2C walls. Its thick walls (most are over a meter thick) and relatively large rooms suggest it is more than a domestic dwelling. So far, two rooms have been found, but a doorway leading to the north suggests that other rooms may be present there. We have not yet reached floor levels even though some of the walls are almost two meters high and must await future excavation, when the surfaces are found, in order to suggest functional interpretations for the building.

Field A has produced a few earth layers and several wall fragments that seem to relate to domestic architecture in scattered locations, but primarily in the south-eastern part of the field (Lawlor 2000). Most of these walls ran north-south and seemed disturbed or were collapsed, perhaps in the earthquake dated to around 1200 B.C. (below). In Field F was a thick layer of fill debris with LB 2B pottery (Low 1997). From the debris came two ceramic female fertility figurines, typical of the Late Bronze Age. Because the debris seemed to have been extra-urban, it is likely that the LB inhabitants lived within the protection of the MB 2C rampart fortification system (ca. 1.5 hectares).

Although no architecture from the earliest phase of Iron 1 has yet been uncovered in Field B, the presence of significant numbers of early Iron 1 pottery in the rampart of the subsequent city (IP 14) infers a settlement that preceded the rampart construction. The pottery contained many pieces that were LB in form. It should thus be dated to the earliest parts of Iron 1. Because of the similarity of the pottery to the preceding LB 2B pottery, we suggest a smooth transition from the LB 2B settlement of IP 16 to that of the early Iron Age 1. A large refuse pit, which contained thousands of animal bones and hundreds of charred cooking pot fragments, may have belonged to this earliest phase. Alternatively, it could have belonged to the houses discovered in the subsequent IP 14.

The most astonishing discovery at ‘Umayri so far is the IP 14 settlement, which included the most extensive and best preserved fortification system so far discovered from this time in all of Palestine (Clark 2000). After an earthquake, which destroyed the earlier MB 2C rampart and moat system near its bottom, a new defensive system was constructed. Preserved by a massive destruction over 2.0 m deep in many places, the fortifications comprised

- a perimeter wall at the top of the slope (built on top of the MB 2C rampart crest)

- a newly constructed rampart 1.5 2.0 m above the MB 2C rampart

- a retaining wall at the bottom of the rampart

- a reuse of the MB 2C dry moat.

But the major structure so far uncovered in IP 14 was a four-room house in Field B. An attached courtyard east of the building contained an apparent animal pen bordered by post bases and filler stones between. The building itself comprised three long rooms abutting a broadroom whose western wall was the perimeter wall of the site. The broad room was filled with ca. 60 collared pithoi (20 from the room itself and another 30-40 fallen from the second floor). Many of the floors in the buildings were paved with flagstones and one of the buildings was a clear four-room house.

A second phase, especially visible in the four-room house constitutes the last phase of the early Iron 1 period (IP 13), though this may simply be a localized rebuilding of the structure. An alternative is that the first phase of the building could belong to the pre-earthquake settlement (IP 15).

The deep destruction debris in Field B suggests the original walls were high. Moreover, reconstructable collared pithoi found within the destruction debris, high above the floors, indicate the presence of at least one upper floor where these jars were stored. At other locations on the site, this destruction was also very graphic. In both Fields A and F a thick layer of ash and burned bricks covered the early Iron 1 walls. Unfortunately, these have not yet been extensively exposed. The strong, fortified settlement of IP 14 was abruptly and violently destroyed. One of the rooms produced five bronze weapons and the burned and scattered bones of at least four individuals, who had mostly likely been burned in the destruction of the upper story and then fell with the debris of the upper story as the floor collapsed. Nothing has yet been found which might suggest the ethnicity of either the inhabitants or the destroyers. After this destruction, the city was not immediately rebuilt.

Field A has produced several isolated wall and surface fragments that can be dated to the early Iron 1 period (Lawlor 2000). But there is not enough to suggest a coherent plan or functional interpretation. The phasing in Field A matches nicely that in Field B. In Field C, a terrace wall had early Iron 1 pottery running up to it; the ashy layer suggests that it was used as a place for garbage disposal (Battenfield 1991a: 85). In Field F, a long terrace wall was constructed which preserved the IP 16 fill layer upslope (Low 1997: fig. 7.8) and allowed early Iron 1 debris to build up above it; similar debris accumulated at the bottom of the wall’s exterior. It would seem that these remains were again outside the contemporary settlement. In Field E, the water source at the bottom of the northern slope, Iron 1 materials probably belong here (Fisher 1997b: fig. 6.6). Stone tumble and fragmentary walls in Field A probably also belong to IP 15.

The settlement at Tall al-‘Umayri thus reflects the regional intensification pattern for the beginning of the Iron Age, although it began perhaps a little earlier than most, near the end of the Late Bronze Age, probably because of easy access to water. Although the site did not grow in size (probably still confined to the acropolis, ca. 1.5 hectares), it appears to have intensified economically, building from an unfortified settlement (IP 15) or one in which the earlier, MB 2C fortification system was reused, to one which constructed the elaborate casemate fortification system in Field B. The pottery may also reflect this intensification process. The vessels from the rampart (the earlier settlement) reflect a utilitarian subsistence pattern, while those from the houses of the later period included a very few chalices and flasks, an alabaster jug, and a fine basalt platter suggesting a more luxurious or complex lifestyle

Above the IP 14-13 rooms immediately inside the perimeter wall was a thin surface with late Iron 1 pottery in both Fields A and B (IP 12). A few wall fragments were found in the north ern portion of Field A (Lawlor 2002: 27). A storeroom was constructed immediately on top the early Iron 1 destruction debris at right angles to the perimeter wall (Clark 1997: fig. 4.29). Into the surface were 18 late Iron 1 collared pithoi sitting in shallow pits supporting their conical bases. The separation of these pithoi from the scores of other pithoi found below the destruction debris emphasizes very well the consistent typological developments that took place during the time between the deposition of the two assemblages (Herr, this volume).

Although it may have been constructed already in the last phase of early Iron 1, it seems more likely that a square room with two pillars and filled with over a meter of fine ash was constructed during IP 12. The walls are clearly above the early Iron 1 walls. Unless a very narrow space between some of the stones in the upper portion of the northern wall of the room was a doorway to the room, no entrance could be detected. In any case, the room may have functioned at least partially underground. We have no function to suggest for the presence of the thick, but fine and powdery ash. It was not deposited in laminated layers and was still very loose as if it had just been deposited a few days earlier.

IP 11 was not strongly represented, but enough evidence exists to suggest that it was a settlement similar to that of IP 12. Both seem to reflect village lifestyles.

The perimeter wall and the rampart seem have continued in use, as well, during both IPs 12-11. Several wall fragments and surfaces in Field H seem to belong to the late Iron 1 and/or early Iron 2 period. One of the walls seems larger than a domestic wall and may be a perimeter wall for a major building complex in IP 11 that was partially paved by thick plaster surfaces. At no other location on the site were other finds made from this period. Only an earth layer or two at the water source could be attributed to this period. It appears that the settlement was limited, perhaps, to a few houses on the western acropolis built upon the ruins of the early Iron 1 town.

No clear evidence for a settlement in the 8th and 7th centuries has been found. There would thus seem to be another hiatus following the brief stutter of activity in IPs 12-11.

Field B, located along the west-northwest escarpment of Tall al-‘Umayri, lies at the point most vulnerable to ancient enemy assault (fig. 2.1). From the bedrock at the base of the western slope to the top of the Iron 1 defenses the vertical rise was ca. 10 m (Clark 2002: fig. 4.4); to the top of the MB rampart 5 m; to the bedrock at the base of the moat 5 m; and to the bedrock of the EB settlement less than 1 m. These figures illustrate well the situation confronting ancient inhabitants of ‘Umayri as they attempted to protect their settlement on its western side. This is particularly the case for the MB and Iron 1 periods that supported significant fortification efforts.

Although initially in 1984 we laid out the four Squares of Field B in a checkerboard fashion to extend exposure both laterally across and longitudinally down the slope of the defenses (Clark 1989), the last several seasons have witnessed a more coherent pattern, especially at the top of the tell. As of the 1994 season, Field B included a trench made up of eight Squares, running east-west and extend ing from the bottom of the slope to a point 10 m inside what we have tentatively called a double or casemate wall system (Clark 2002). They are, from bottom to top: 7J84, 7J85, 7J86, 7J87, 7J88, 7J89, 7K80, and 7K81 (fig. 4.1). Two Squares (7J98 and 7K90), both from 1984, lie north of and adjacent to the trench. The previous season also saw the opening of three new squares either straddling or inside the perimeter wall (7J99, 7K91 and 7K92), as well as continued work in 7K90. Thus, we began the 1996 season with not only the major east-west trench completed, but as well a line of three squares immediately to the north of and adjacent to the trench (fig. 4.1).

Previous excavation seasons have proven remarkably productive (Clark 1989; 1991; 1997; 2000; 2002). Among the major architectural discoveries: extremely ephemeral remains from the EB settlement (on the bedrock shelf of 7J88, beneath the MB rampart construction) (Clark 2000: 64); portions of the MB2C dry moat and rampart (in Squares 7J84, 7J85, 7J88 and 7J89) (Clark 2002: 49-51); extensively preserved remains from the early Iron 1 defense system and associated buildings inside the fortifications (in all squares of the Field) (Clark 2002: 51-100); a storeroom from the late Iron 1/early Iron 2 period (located in 7J89 and 7K80) (Clark 1989: 250-253; 1991: 58-62); late Iron 2 structures (throughout the squares inside the perimeter wall) and likely periodic rampart repairs (throughout the squares outside the walls) (Clark 1991: 62-69); and fragments of Persian structures and repairs (throughout most squares in the Field) (Clark 1991: 69-72).

At the bottom of the slope (fig. 4.1), Square 7J84 (opened in 1992) revealed the westernmost extension of the defenses—the bedrock outer edge of the dry moat (Clark 2002: fig. 4.5). Square 7J85 (begun in 1989) encompassed virtually nothing but the moat, which was first dug in antiquity during MB2C and later reused by the Iron 1 defenders of the city. Moving up the slope to the east, layers of the Iron 1 rampart (and later repairs) were represented in Squares 7J86 (opened in 1987), 7J87, 7J88, and 7J98. The last three were at least partially started in 1984, with 7J98 lying outside and to the north of the main trench line, adjacent to 7J88. Square 7J88 also exposed the upper portion of the MB2C rampart (Clark 1997: fig. 4.5) built on a bedrock shelf scraped clear of EB occupational debris prior to construction (Clark 2000: fig. 4.8). Square 7J89 (begun in 1984) contained, below the level of a late Iron 1/early Iron 2 storeroom, an entire early Iron 1 store room, complete with more than 15 collared pithoi (two standing in situ), thousands of carbonized grain seeds, and evidence of an intense blaze which turned some of the wall stones into powdered lime (Clark 1997: fig. 4.13). Adjacent were two squares east of the storeroom—7K80 and 7K81 (both begun in 1987). Their excavation divulged portions of two early Iron 1 buildings, well preserved beneath nearly 2 m of destruction debris from second story mudbrick walls (Clark 1997: fig. 4.10). The south ernmost one, Building A, contained three rooms, but it is not yet completely excavated (Clark 2000: fig. 4.15). The farthest room from the perimeter wall was for domestic use, the next room toward the west (and the perimeter wall) suggested a cultic function (Clark 2000: fig. 4.18), and the storeroom itself (in 7J89) comprised the third room. The adjoining building (B) to the north was exposed sufficiently enough (especially through excavations of 7J99 and 7K91 in 1994) to determine that it was a pillared building tied in some way to the perimeter wall (Clark 2002: fig. 4.31). Square 7K90, immediately inside the perimeter wall and adjacent to the north of 7K80, was begun in 1984 and gave us the first indication of a massive tumble of mudbrick which preserved the early Iron 1 remains (Clark 1989: fig. 16.2). The late Iron 2 period saw the construction of parallel east-west walls with a beaten earth surface between them. Square 7K92 (opened in 1994) exposed only late Iron 2 remains including walls (Clark 2002: fig. 4.47), two surfaces, and the presence of large pits (Clark 1989: fig. 16.8).

Our work in 1996 and 1998 had several objectives.

- For the early Iron 1 period, we wished to expose horizon tally the complete extent of the pillared house (Building B) and investigate the area immediately adjacent to its eastern wall (Clark 2002: fig. 4.31). We also hoped to uncover early Iron 1 remains to the north of Building B, assuming the settlement extended in that direction toward an expect ed northern perimeter wall perhaps 10 m away and might expose yet another building.

- We also hoped to continue exploring what made this small site (ca. 1.5 hectares) significant enough to merit such strong fortifications early in the Iron Age.

- For the Late Bronze Age, we hoped to find any kind of architectural feature that could explain the presence of LB ceramics at the site.

- The Middle Bronze Age continued to pique our curiosity, leading us to intensify our quest to find something inside the walls related to the massive rampart already studied.

- In addition, we maintained our commitment to place our finds within the context of food-systems theory with an eye toward the cyclical oscillation between times of intensification and abatement of settlement and land use.

- Finally, we paid close attention to the need for and methods of accomplishing restoration and preservation of the site for future research and educational purposes.

In the course of the 1996/98 seasons, we achieved a broader exposure of early Iron 1, Late Bronze, and Middle Bronze (along some with Iron 2 and Persian) architecture inside the settlement, and, in the process, we can be more confident in our assessment of the construction design and features of these settlements, and of the lifeways of the inhabitants during these various periods. We also have a clearer understanding of the challenges faced and efforts expended by the builders of the Iron 1 defenses outside the perimeter wall.

Past excavation to bedrock in Squares 7J85, 7J86, and 7J87 allowed a more complete picture of the MBIIC defenses as well. Significant deterioration and collapse, however, stemming from a major earthquake around 1200 B.C., resulted in major damage to parts of the rampart, thereby limiting our efforts to reconstruct it completely. In order to preserve both the early Iron 1 and Middle Bronze defense structures and to make them accessible to site visitors, we cleared the beaten-earth rampart in three levels (Clark 2002: fig. 4.5). The northern third exposed the surface of the early Iron 1 rampart; the central third shows the way the MBIIC rampart appeared before the earthquake; and the southern third was excavated to bedrock. This now graphically presents the important stages in the history of the western defenses and, except for the central exposed portion (MB), the ramparts have weathered several years of exposure very well.

Prior to the 1996/98 seasons 13 Field Phases had been delineated, extending from Early Bronze to post-Roman periods. Some of the dating for the phases has changed since previous publications. Phase 13, not well represent ed in Field B, consisted of two shallow layers of debris from the Early Bronze Age left in bedrock cavities following ancient clearing operations for construction of the MB2C rampart (Clark 2000: fig. 4.8). Along with the dry moat construction, this rampart constituted Phase 12. Near the top of the slope (in 7J88) the rampart was 3 m deep above the level bedrock, becoming shallower as it continued down the hill. Phases 11B and 11A represented the early Iron 1 settlements before and during use of the massive defense system. A late Iron 1 rubble layer, apparently separating two clearly defined phases, made up Phase 10 and a late Iron 1 storeroom and associated surfaces comprised Phase 9. Phases 8-6 dated from the late Iron 2 to Persian periods and consisted of limited remains, stratigraphically well defined in only one or two squares each (on top of the tell). These included pits and a stone-lined silo, later covered by a temporary hearth. Mainly domes tic structures made up Phases 5 and 4, Persian in date. An early Roman ritual bath (in Squares 7K80 and 7K81 and in Field A) represented Phase 3, followed by Phase 2, a massive pit/trench which had been dug around the pool complex. An ephemeral wall and topsoil complete the stratigraphy as Phase 1.

Field excavations in 1996/98 have in fact somewhat altered our understanding of Field B phasing. We have changed designations for one phase and added another to the 1994 cumulative assessment. Phase 11B has become Phase 12 (early Iron 1); Phase 13 (previously Middle Bronze) is now the designation for the Late Bronze period; the Middle Bronze Age is now represented by Phase 14; and the ephemeral remains from the Early Bronze period atop the bedrock beneath the MB rampart constitute Phase 15. Fig. 4.2 is the stratigraphic summary of phasing by square as plotted following the 1996/98 seasons. Fig. 4.3 is a comparative phasing chart by season, relating the phase numbers for each of the seven seasons. Fig. 4.4 is a stratigraphic sequence chart that identifies all of the 1996 and 1998 loci by square and by phase as reflected in the report that follows. Horizontal lines indicate major destruction levels.

In what follows, only Field Phases excavated in 1996/98 will be listed and treated. Likewise, only the loci excavated during these two seasons are included. In the course of the seasons represented in this report, it became apparent that some loci designations needed to be discard ed, normally because two loci turned out to be only one, upon further investigation. This is the case for 7K82:9 and 10, which turned out to be part of tumble Layer 21; 8K00:22, which was combined with another earth layer; 8K01:9, which became clear as the top of 8K01:19; 8K01:18, which collapses into 8K01:26; 8K01:35, which was voided.

Loci excavated in 1996 and 1998

Loci excavated in 1996 and 1998Herr et al. (2014)

The early Iron 1 phases (11B and 11A in 1994) have appeared in all squares in the Field and have demanded most of our attention in Field B since excavations began in 1984. It represents one of the very earliest and best-preserved defense systems anywhere in the Levant from this time. From previous seasons we know the basic features of the defenses (Clark 2002: fig. 4.4): a dry moat at the base of the western slope (reusing the old MB 2C moat), a retaining wall on the east side of the moat (toward the tell), a steep rampart (35°, although this leveled somewhat as it approached the perimeter wall), a stabilizing row of stones to help hold the top rampart layer in place against erosion, and a perimeter wall. This was all built atop the disturbed and partially eroded Phase 14 Middle Bronze rampart following a major earthquake, dated to around 1200 (Clark 2002: 49-51).

Inside the perimeter wall in earlier seasons we discovered parts of two buildings built against the wall (fig. 4.22 below). Building A was divided into three rooms, including a cultic installation and domestic food-preparation area. The perimeter wall and adjoining rooms were covered, and thus preserved, by up to 2 m of destruction debris from the ceiling/roof of two stories, the lower constructed of stone and the upper of mudbrick. Building B began to emerge in 1994 and, although excavations to that point did not expose all the features of the building, the shape of a large, multi-room building was becoming apparent. At the time we designated four rooms, beginning at the eastern end. The functions of Rooms B1, B2, and B3 were not readily clear to us following the 1994 season, but Room B4 at the back of the building and situated against the perimeter wall revealed approximately 70 collared pithoi, half of which had fallen down from a second-story store room along with ballistica, lance points, and the scattered burned bones of at least four people, likely killed on the roof attempting to defend the settlement from attackers, if the weapons have any relevance, or perhaps simply occupying the house on the second story when killed.

Based on the presence of early Iron 1 ceramic material (including a few sherds from the tail end of the LB tradition) in the Phase 11 rampart layers, we inferred a second, earlier phase following the 1992 season (Clark 2000: 66-73). Phase 11 was thus divided into two parts: Phase 11B represented a transitional Late Bronze/early Iron 1 settlement prior to the construction of the defenses. It was the debris from this occupation that provided the rampart builders with their construction material. The only definitive Phase 11B remains we have been able to identify with certainty are those now reused in the rampart construction. However, we have been looking to continued excavation that could contribute to an understanding of Phase 11B structures inside the perimeter wall. A number of rooms now accessible to us reveal two levels of stone paving, normally larger flagstones immediately over cobbles, in Squares 7K80, 7K81, and 7K90. Were these repairs to damaged floors? If so, this damage was perhaps connect ed with the earthquake that appears to have broken the bedrock beneath the Middle Bronze rampart in Square 7J87 forcing the reconstruction of the defensive system (Clark 2000: 66-73; 2002: 51). Interpretive challenges remain, however, about how the house related to the perimeter wall, because the wall was constructed post earthquake and the house appears to have abutted the wall.

Following the 1996/98 excavations, we feel it is time to give this phase independent status and have thus designated it Phase 12. The natural disaster in the form of the earthquake around 1200 B.C. has drawn a substantial stratigraphic line between what preceded it and what followed that we feel justified in renaming the phase. As already noted (Clark 2000: 66-73), the evidence outside the perimeter wall is convincing. And, while not as persuasive, the repairs inside the settlement and now new stratigraphy from Square 7K92 at least provide some support for the idea.

Excavations carried out in 1996/98 in Square 7K92 have forced us to consider several matters related to the transition between the Late Bronze (Phase 13) evidence we now have and the early Iron 1 remains (Phase 11), especially the four-room or pillared house (Building B) immediately west of this square. In particular, two areas of excavation deserve mention: first, a massive pit 1.5 m east of the Phase 11 four-room house (Building B), and second, limited stratigraphy in the space between house and pit.

The pit itself was fortuitously dug in antiquity into a series of pre-existing, superimposed walls that provided well for the lining of the pit on east, south, and west sides (fig. 4.19). At the bottom of the pit, Phase 14 Walls 7K92:24 and 29 and hard-packed Surfaces 35 and 36 marked the bottom of the pit.

Our description will begin on the eastern side of the pit and move clockwise (fig. 4.18). Directly above and virtually following the same line as Phase 14 Wall 24 (6 degrees difference in orientation), Wall 7K92:22 added another 1.4 m of height to the eastern wall of the pit. Like Wall 24 (and Wall 2 above it), Wall 22 was half buried in the east balk of the square, in fact disappears into it toward the northern end of the east balk. It also abuts Phase 14 Wall 20 at its southern extremity, a wall that survives to a height within 0.75 m of Wall 22. Stones in Wall 22 were mostly small boulders, with some cobbles and a few medium boulders. Atop Wall 22, Phase 6 Wall 7K92:2 was founded, again along the same orientation.

Also abutting Phase 14 Wall 20, now in the south western corner of the pit, was Wall 7K92:25. It consisted of irregularly laid small and medium boulders maintaining the same orientation as Phase 14 Wall 29, although now slightly curvilinear (352° to 010°) and resting directly on top of it for the most part. It ranged from 0.8 to 1.1 m in height and may actually have provided founding for Foundation Wall 7K92:23 precisely over it. Wall 23, most ly small and some medium boulders, was also slightly curvilinear (orientations changed from 344° to 010°), and survived beneath Wall 7K92:9 to a height of 0.5 to 0.7 m. Wall 9, not curvilinear and oriented at 020°, rested direct ly atop Wall 23, except along the southern portion where Wall 23 begins its curve to the east. In construction, it consisted of an even split between small and medium boulders, was 0.90 to 0.95 m wide, and measured 0.57 to 0.65 m high. It represents the latest of the superimposed walls to be used as the western lining for the fill in the pit.

In the pit itself, beginning on top of the Phase 14 Layers 31 and 32 and building upward, were Layers 7K92:30, 26 and 14/19. Layer 30 covered the entire space within the pit for an average depth of 0.35 m (its top level being determined arbitrarily at the beginning of a new sea son of excavation) and consisted of brown earth, contain ing large amounts of bones, some ash pockets and pebbles, and several small object fragments (mostly undeterminable), including a stone plate fragment (Object No. B986561). Layer 7K92:26 represented the earth above Layer 30. It was yellowish-brown, 0.7 m deep, and contained a large ash pocket, large amounts of bones and some shells. It was also arbitrarily set apart from what lay above it: Layers 7K92:14/19. Layers 14 and 19 consisted of brown earth between 1.05 and 1.32 m deep. Layer 19 marked a 1-to-1.5-m-wide portion of pit debris beneath and north of Phase 7(?) Wall 7K92:12, while Layer 14 filled the remainder of the pit at the same level and should be understood to represent the same earth layer. This layer contained ash and nari pockets, some bricky materials, a remarkable amount of bones, pottery, and small objects/object fragments. By far, most of the objects/ object fragments were domestic (textile operations, food preparation and storage, cosmetic application, recreation), and a very small number administrative or military. All the earth loci in the pit consisted of thin layers with ashy deposits and were slightly sloped from the west down toward the east. They thus represented periodic fill debris from above.

In the end, the superimposed walls (24 and 22 on the east; 20 on the south; and 29, 25, 23 and 9 on the west) formed the contours of the massive pit (Locus 7K92:46) measuring 2.7 m wide, 4.2 m long and 2.4 m deep and containing pottery dating for the most part to the earliest years of the Iron 1 period. The contents of the pit included 50 small objects/object fragments, 4700 ceramic sherds and approximately 15,000 bone fragments.

Some stratigraphic questions remain, but the picture is fairly clear overall. It appears the inhabitants of ‘Umayri at around 1200 or slightly before dug out a garbage pit. They excavated down to the hard-packed earth of Phase 14 Surfaces 35 and 36 within an area bounded by Walls 24 on the east, 20 on the south and 29 on the west. On the one hand, did they construct the superimposed Walls 22 on the east (above 24) and 25 and 23 on the west (above 29) to increase the depth of the pit or to keep it from collapsing? Both Walls 22 and 23 were founded at the same level. But, at least on the western side of the pit, Wall 9 raised this side further, now to a level equal with the top surviving level of Wall 22. On the other hand, were the Phase 12 inhabitants simply fortunate to have found already superimposed walls in place (Walls 24 and 22 on the east and Walls 29, 25, 23 and 9 on the west) and oriented nicely for their purposes? Further excavation of these walls will be necessary to provide answers to these questions.

When completed, the pit was filled over time with refuse that formed a homogenous fill for virtually its entire depth. Since there were so many sherds, because most of the objects/object fragments were domestic in nature and since the bones were almost wholly those of edible portions of domesticated animals (Peters, Pöllath, and vonden Driesch 2002), we suggest this was a disposal site per haps for the household immediately west (and upwind) of the pit, along with other households. There was also a very large ratio of cooking potsherds among the ceramic remains, again suggesting that the fill contained refuse from cooking and eating.

Given the difficulty of placing the pit stratigraphically before the earthquake of 1200 or after, in light of the problems associated with our understanding of the Iron 1 four-room house (Building B) to the west of the pit in terms of its initial construction and repairs (did construction or repairs or both come after the earthquake?), and given the lack of a direct stratigraphic connection between the two features, we can only place the pit in Phase 12 with some reservations. These reservations extend to uncertain ties about assigning the four-room house to Phase 11, a phase representing construction inside the perimeter wall following the earthquake, although a Phase 11 designation appears the more likely for Building B.

This brings us to the area west of the pit but east of the four-room house in Square 7K92. Several earth layers became apparent in the western portion of the square, lay ers that have not yielded as much stratigraphic information as we could wish. On top of Phase 14 Surfaces 40, 38 and 39 was Layer 7K92:37 in the southwestern corner of the square. It measured 2.06 by 1.27 m and was 0.5 m deep. Its top level was arbitrarily determined. Farther north along the west balk were Surfaces 7K92:27 and 28. Surface 27 was preserved to a length of 0.85 m and a width of 0.65 and consisted of a very pale brown, plaster-like material. Likely associated with this surface, Surface 28 was made up of three flat-lying stones (two medium boulders and one small boulder) that might have been part of a pavement (or the top courses of a wall?). Over all these loci there was another earth layer (7K92:18), which contained brown earth and large amounts of pebbles and cobbles. It stretched over most of the western third of the square and measured 0.45 m deep.

Unfortunately, given the limited area within which to excavate and the complex potential connections with other walls(?), very little can be said about these loci at the present time. Ceramic evidence fairly consistently points to an early Iron 1 date (fig. 4.20), but later pitting in the area has increased the risk of contamination.

Tell al-`Umayri

Douglas R. Clark, Walla Walla College, Larry G. Herr, Canadian University College, and Lawrence T. Geraty, La Sierra University, report:

Finds from three major time periods in Jordan's history have been excavated at Tell al-'Umayri, located about 12 km south of Amman's 7th Circle on Airport Highway. The Bronze and Iron Ages between 1500 and 500 B.C. and the Hellenistic period around 150 B.C. have again yielded up significant discoveries during our ninth excavation season at the site.

The team of 37 archaeologists from the United States, Canada, and Poland worked six weeks at the site, where the team has been working since 1984 with a crew of workers from the nearby village of Bunayat. The site is conveniently located between two national parks — the Amman National Park immediately to the west and Ghamadan National Park on the eastern side of Airport Highway.

What appears at this stage of excavation to be a palace (or at least more than a domestic building) that is almost 3,500 years old was discovered with walls preserved to about 1.3 m thick and 3.5 m high (fig. 13). Parts of four rooms of this Late Bronze Age building have been discovered along with pottery vessels and crudely made ceramic figurines dating to the time just prior to its construction. The remarkable state of preservation of the building is all the more spectacular because of the rarity of other buildings from this time period in Jordan. Although other buildings of this date exist at sites in the Jordan Valley, none are nearly as well preserved as this one, and only two or three others exist in the highlands.

Excavators reached the floor in two of the rooms, but they will need another season to do so in the other two. Portions of a large perimeter wall were discovered surrounding the building. An earthquake distorted many of the north-south walls from this period at the site, including some of those in the palace.

The palace probably reused a strong perimeter wall and rampart constructed at the end of the Middle Bronze Age ca. 1600 B.C. The structure is now one of the best preserved buildings from this period in the Levant.