Qumran

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Khirbet Qumran | Arabic | خربة قمران |

| Qumran | Hebrew | קומראן |

Khirbet Qumran is situated on the western shore of the Dead Sea, on a spur of the marl terrace, bounded on the south by Wadi Qumran and on the north and west by ravines.lt is probably to be identified with 'Ir ha-Mela (City of Salt), one of the six cities of Judea listed in Joshua 15:61-62 as situated in the wilderness. The area was inhabited several times, beginning with the Israelite buildings of the City of Salt to the Byzantine hermitage at 'Ein Feshkha.

During five campaigns of excavation at Khirbet Qumran, a building complex, extending over 80 m from east to west and 100 m from north to south, was completely cleared. Several periods of occupation were clearly distinguished.

The archaeological investigations at Qumran and 'Ein Feshkha are closely connected with the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The first manuscripts were found by chance in 1947 by Bedouin shepherds in a cave (no. 1) situated near the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea. The cave was excavated in 1949 by a joint expedition from the Jordan Department of Antiquities, the Palestine Archaeological Museum (now the Rockefeller Museum), and the Ecole Biblique et Archeologique Francaise. The site ofKhirbet Qumran, approximately 1 km (0.6 mi.) south of the cave and slightly farther west of the Dead Sea, was excavated under the same auspices in five successive campaigns, from 1951 to 1956. The last campaign surveyed the region situated between Qumran and the source of 'Ein Feshkha, 3 km (2 mi) to the south. A building complex was excavated near this source in 1958. A second cave containing scrolls, discovered by Bedouin in 1952, prompted the above institutions, together with the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem, to explore the entire cliff face dominating Khirbet Qumran. It was during this campaign that cave 3, containing manuscripts and the Copper Scroll, was found. In 1952, Bedouin opened a fourth cave (cave 4) in the marl terrace. When the joint expedition subsequently cleared this cave, it found thousands of fragments belonging to about a hundred manuscripts, as well as a fifth cave on the same terrace. Cave 6, the source of scroll fragments already purchased from Bedouin, was then located at the entrance to Wadi Qumran. In the course of the 1955 expedition at Khirbet Qumran, caves 7 to 10 were discovered at the edge of the plateau overlooking Wadi Qumran, south of Khirbet Qumran. Cave II, which had been searched by Bedouin in 1956, was cleared by archaeologists during the last season of excavations at Khirbet Qumran.

The area's most important occupation extended from the second half of the second century BCE down to the year 68 CE. It left its traces in the caves in the cliffs and on the marl terrace and in the buildings at Qumran and Feshkha. The people who dwelled in the caves and in the huts near the cliffs assembled at Qumran to engage in communal activities. They worked in the workshops at Qumran or on the farm at Feshkha, and after their death they were buried in one of two cemeteries. This was a highly organized sect, as is indicated by the careful planning of the buildings, the water system, the numerous communal facilities, and the arrangement of the graves in the larger of the two cemeteries. The special method of burial, the large assembly hall that also served as a collective dining room, and the remains of meals that were so meticulously interred, all indicate that this community had a religious character and practiced its own peculiar rites and ceremonies. The scrolls discovered at Qumran confirm these conclusions and furnish additional information. The archaeological evidence proves that the scrolls belonged to the religious community that occupied the caves and the buildings at Qumran. These scrolls represent the remains of their library, which contained works describing the organization of the community and the laws that governed its members. The archaeological discoveries at Khirbet Qumran and 'Bin Feshkha were thus interpreted in the context of a living community. Some of the scrolls contain allusions to the history of this sect, which had detached itself from the official Judaism in Jerusalem. The sect led a separate existence in the desert, absorbed in prayer and labor while awaiting the Messiah. The interpretation of these historical references has been the subject of much debate. The archaeological discoveries cannot be expected to provide a decisive answer. They merely lend credence to the hypotheses that a community flourished on the shore of the Dead Sea from the second half of the second century BCE until 68 CE, and that the events described in the manuscripts occurred at Qumran during this period.

The religious affiliation of the community has also been the subject of controversy. Most scholars, however, consider the community to have been in some way connected with the Essenes. This is not contradicted by the archaeological evidence, which indeed provides corroboration. Pliny (NH V, 73) relates that the Essenes lived in isolation among palm trees in a region west of the Dead Sea - at a safe distance from its pestilential salt water. To the south is the region of En-Gedi. There is only one site that corresponds to this description between En-Gedi and the northern end of the Dead Sea: the Qumran Plateau. There is only one region where palm trees can grow in quantity and where it is certain they did grow in ancient times: the region between Khirbet Qumran and Feshkha. The Essenes of Pliny, then, in the opinion of this writer, were the religious community of Qumran-Feshkha.

In the thirty years since de Vaux published his preliminary reports and the French edition of his comprehensive book, a substantial body of literature dealing with problems concerning the archaeology of Qumran has accumulated. In the absence of a final report this discussion relies on preliminary data.

The subject most discussed is the chronological definition of Khirbet Qumran's various strata. The general chronological framework suggested by de Vaux enjoys almost universal consensus. However, of the eight dates offered (actually only five, as three coincide), only one can be established with near certainty. This is the end of stratum II - that is, summer 68 CE - the date the Qumran community ceased to exist. Even here, however, the precision of the date is based on interpretation of historical-literary sources.

The subjects most discussed are the nature and duration of the gap between phase Ib and II. Strong arguments, archaeological as well as historical, have been raised against the excavator's assertion that the site was deserted between 31 and 4 BCE. While the date of the beginning of the gap and its cause (an earthquake) seem quite plausible, although by no means certain, there is considerable doubt that the gap lasted longer than a couple of years.

Near Khirbet Qumran are three cemeteries - one large, with about 1,100 graves, and two small, with 100 graves altogether. On1y about 50 of these 1,200 graves were excavated. In the large cemetery only skeletons of adult males were found, but in the small cemeteries remains of women and children also were found. The existence of the latter graves in a site presumed to have been occupied by a monastic community naturally raised queries. As there are signs that some of the buried were brought from a distance, the explanation for the presence of the females and minors is that they were related to the regular residents of Qumran, either by kinship or ideological beliefs.

N. Golb, the proponent of a counter-theory to the widely accepted view that Qumran was occupied by an Essene monastic community, has suggested that the ruins are, rather, the remains of a fortress. This seems an unlikely explanation, as the site is of inferior strategic value and the flimsy walls of the complex could not have had military value.

Since 1967, several expeditions have conducted surveys, both extensive and intensive, in the neighborhood of Qumran (mainly those led by P. Bar-Adon and J. Patrich). Since 1956, no new manuscripts have been discovered (q.v. Judean Desert Caves).

- Qumran in Google Earth

- Qumran on govmap.gov.il

- Annotated Aerial View of Qumran

from BibleWalks.com

- Plate XL - Map of Qumran region

from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XL

Plate XL

Map of the Qumran region. Nos. 1-40 show the sites with traces of human occupation from north to south. Nos. 4, 5, 6, II, 13, 16, 20, 23, 24, 25, 27, 33, 34, 35, 36, 38 seem not to have been utilized by the community of Qumran. The manuscript caves are indicated by signs 1Q to 10Q. The map was published towards the end of 1955. Cave 11Q, discovered in 1956, is a little to the south of site 8 = 3Q.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 35 - Aerial Photograph of the

Water System from Magen and Peleg (2007)

Fig. 35

Fig. 35

Aerial Photograph of the Water System

Magen and Peleg (2007)

- Plate XL - Map of Qumran region

from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XL

Plate XL

Map of the Qumran region. Nos. 1-40 show the sites with traces of human occupation from north to south. Nos. 4, 5, 6, II, 13, 16, 20, 23, 24, 25, 27, 33, 34, 35, 36, 38 seem not to have been utilized by the community of Qumran. The manuscript caves are indicated by signs 1Q to 10Q. The map was published towards the end of 1955. Cave 11Q, discovered in 1956, is a little to the south of site 8 = 3Q.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 35 - Aerial Photograph of the

Water System from Magen and Peleg (2007)

Fig. 35

Fig. 35

Aerial Photograph of the Water System

Magen and Peleg (2007)

- Plan of the Qumran settlement

from biblewalks.com

- Fig. 4 - General Plan of Qumran

from Magen and Peleg (2007)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Qumran, general plan

Magen and Peleg (2007) - Fig. 12 - Plan of the Tower

from Magness (2002)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12

Plan of the Tower

Magness (2002)

- Fig. 4 - General Plan of Qumran

from Magen and Peleg (2007)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Qumran, general plan

Magen and Peleg (2007)

- Fig. 6 - Plan of Phase Ia settlement

from Magness (2002)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Plan of Qumran in Period Ia

Magness (2002) - Plan of Phase Ib settlement

from Stern et al (1993 v. 4)

Khirbet Qumran: plan of the phase lb settlement.

Khirbet Qumran: plan of the phase lb settlement.

- Entrance of the aqueduct

- Reservoir

- Reservoir

- Tower

- Room with benches along the walls

- Scriptorium

- Kitchen

- Assembly hall and refectory

- Pantry

- Potter's workshop

- Kilns

- Cattle pen

Stern et al (1993 v. 4) - Fig. 7 - Plan of Phase Ib settlement

from Magness (2002)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Plan of Qumran in Period Ib

Magness (2002) - Plate XXXIX - Plan of Qumran

in Phases Ib and II with all the loci from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIX

Khirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II.

JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 8 - Plan of Phase II settlement

from Magness (2002)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Plan of Qumran in Period II

Magness (2002)

- Fig. 6 - Plan of Phase Ia settlement

from Magness (2002)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Plan of Qumran in Period Ia

Magness (2002) - Plan of Phase 1b settlement

from Stern et al (1993 v. 4)

Khirbet Qumran: plan of the phase lb settlement.

Khirbet Qumran: plan of the phase lb settlement.

- Entrance of the aqueduct

- Reservoir

- Reservoir

- Tower

- Room with benches along the walls

- Scriptorium

- Kitchen

- Assembly hall and refectory

- Pantry

- Potter's workshop

- Kilns

- Cattle pen

Stern et al (1993 v. 4) - Fig. 7 - Plan of Phase Ib

settlement from Magness (2002)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Plan of Qumran in Period Ib

Magness (2002) - Plate XXXIX - Plan of Qumran

in Phases Ib and II with all the loci from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIX

Khirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II.

JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 8 - Plan of Phase II settlement

from Magness (2002)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Plan of Qumran in Period II

Magness (2002)

- Cracked Steps at Qumran -

photo by Jefferson Williams

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumran

photo by Jefferson Williams - Plate XVI - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XVI

Plate XVI

Cistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 39 - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from Magness (2002:56)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39

View of the miqveh in L48-L49. Notice the low, plastered partitions on the steps, and the earthquake damage which has caused the left-hand side of the steps to drop

Magness (2002) - Plate Xa - Broken Pottery -

some upside down - in loci 89 from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xa

Plate Xa

Broken Bowls in the south-eastern corner of loc. 89

JW: these bowls are referred to as being in situ in Stern et. al. (1993 v. 4). This photo was not referenced by de Vaux in his Seismic Effects discussion but it is notable that a number of them appear to be upside down indicating that they fell.

de Vaux (1973b) - Plate Xb - Piles of Dishes

from loci 89 from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xb

Plate Xb

Piles of dishes against the southern wall of loc. 89

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 27 - Column bases

(re-used building elements) from Magness (2002)

Fig. 27

Fig. 27

Column bases in the southern part of the secondary building

Magness (2002)

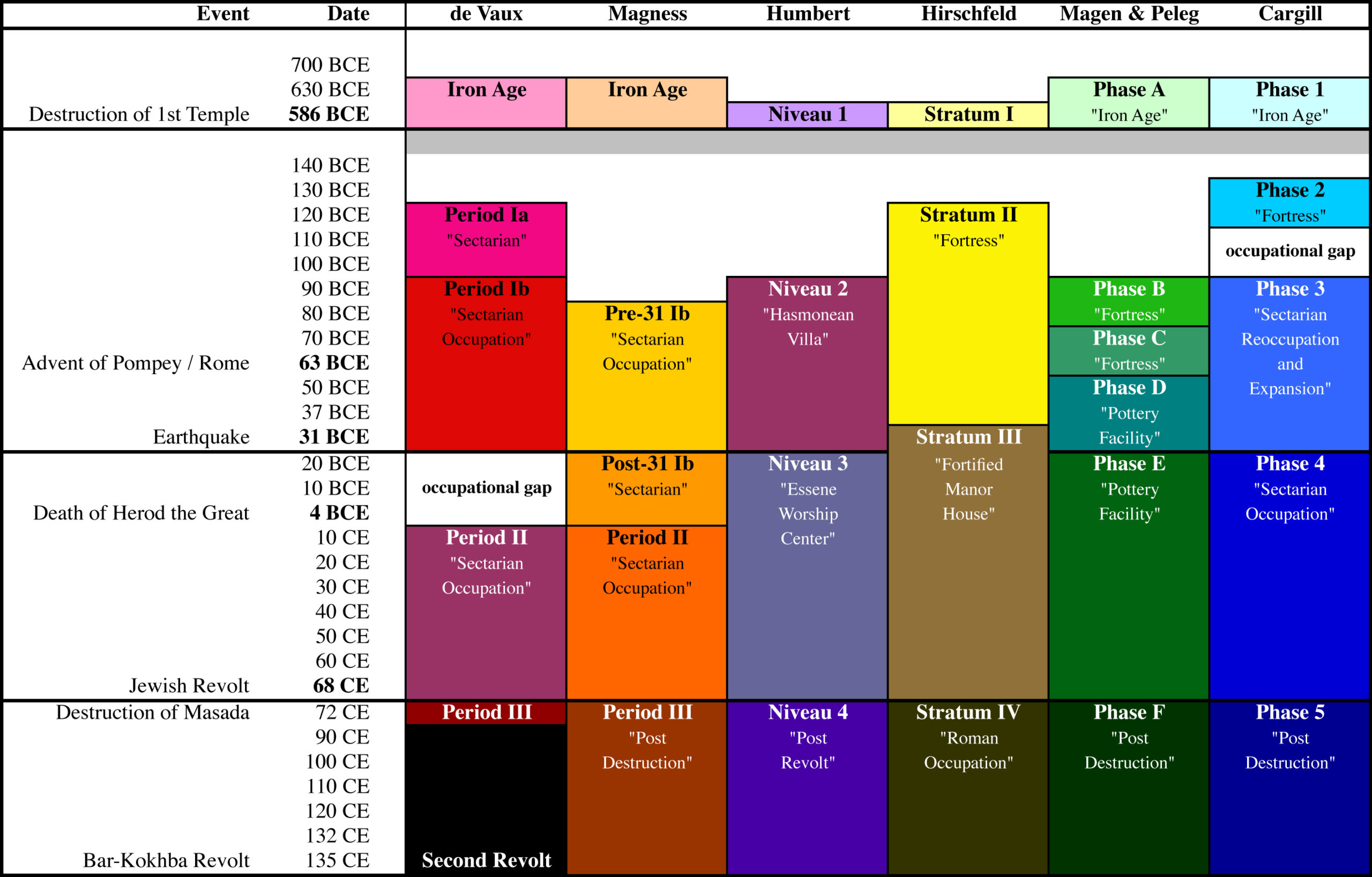

- The chronology of Qumran is so debated that there are at least 6 different naming systems for the various phases

- from Broshi in Stern et al (1993 v. 4)

The subject most discussed is the chronological definition of Khirbet Qumran's various strata. The general chronological framework suggested by de Vaux enjoys almost universal consensus. However, of the eight dates offered (actually only five, as three coincide), only one can be established with near certainty. This is the end of stratum II - that is, summer 68 CE - the date the Qumran community ceased to exist. Even here, however, the precision of the date is based on interpretation of historical-literary sources.

The subjects most discussed are the nature and duration of the gap between phase Ib and II. Strong arguments, archaeological as well as historical, have been raised against the excavator's assertion that the site was deserted between 31 and 4 BCE. While the date of the beginning of the gap and its cause (an earthquake) seem quite plausible, although by no means certain, there is considerable doubt that the gap lasted longer than a couple of years.

Near Khirbet Qumran are three cemeteries - one large, with about 1,100 graves, and two small, with 100 graves altogether. Only about 50 of these 1,200 graves were excavated. In the large cemetery only skeletons of adult males were found, but in the small cemeteries remains of women and children also were found. The existence of the latter graves in a site presumed to have been occupied by a monastic community naturally raised queries. As there are signs that some of the buried were brought from a distance, the explanation for the presence of the females and minors is that they were related to the regular residents of Qumran, either by kinship or ideological beliefs.

N. Golb, the proponent of a counter theory to the widely accepted view that Qumran was occupied by an Essene monastic community, has suggested that the ruins are, rather, the remains of a fortress. This seems an unlikely explanation, as the site is of inferior strategic value and the flimsy walls of the complex could not have had military value.

Since 1967, several expeditions have conducted surveys, both extensive and intensive, in the neighborhood of Qumran (mainly those led by P. Bar-Adon and J. Patrich). Since 1956, no new manuscripts have been discovered (q.v. Judean Desert Caves).

Chart of various scholars' chronological proposals for Qumran

Chart of various scholars' chronological proposals for QumranWikipedia - IsraelXKV8R

- Cracked Steps at Qumran -

photo by Jefferson Williams

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumran

photo by Jefferson Williams - Plate XVI - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XVI

Plate XVI

Cistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 39 - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from Magness (2002:56)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39

View of the miqveh in L48-L49. Notice the low, plastered partitions on the steps, and the earthquake damage which has caused the left-hand side of the steps to drop

Magness (2002) - Plate Xa - Broken Pottery -

some upside down - in loci 89 from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xa

Plate Xa

Broken Bowls in the south-eastern corner of loc. 89

JW: these bowls are referred to as being in situ in Stern et. al. (1993 v. 4). This photo was not referenced by de Vaux in his Seismic Effects discussion but it is notable that a number of them appear to be upside down indicating that they fell.

de Vaux (1973b) - Plate Xb - Piles of Dishes

from loci 89 from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xb

Plate Xb

Piles of dishes against the southern wall of loc. 89

de Vaux (1973b)

Roland de Vaux, the original excavator of Qumran, interpreted a destruction layer between Periods Ib and

2 which he attributed to an earthquake (in 31 BCE) and a fire which caused the settlement to be abandoned for several decades. This interpretation has been challenged -

particularly the several decade long abandonment. Magness (2002), for example, proposed a revised chronology

which subdivided Phase Ib into two sub-phases - before and after a 31 BCE earthquake. The fire and subsequent abandonment was presumed to have occurred almost 30 years after

the earthquake. Magness (2002) suggested that the fire was due to human agency caused by military activity and/or unrest in the area.

For archaeoseismic purposes, most chronologies of

Qumran agree that the site was impacted by the 31 BCE Josephus Quake

earthquake with Hirschfeld, who excavated nearby

En Feshka, as a notable exception.

- Fig. 7 - Plan of Phase Ib settlement

from Magness (2002)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Plan of Qumran in Period Ib

Magness (2002) - Cracked Steps at Qumran -

photo by Jefferson Williams

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumran

photo by Jefferson Williams - Plate XVI - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XVI

Plate XVI

Cistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 39 - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from Magness (2002:56)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39

View of the miqveh in L48-L49. Notice the low, plastered partitions on the steps, and the earthquake damage which has caused the left-hand side of the steps to drop

Magness (2002) - Plate Xa - Broken Pottery -

some upside down - in loci 89 from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xa

Plate Xa

Broken Bowls in the south-eastern corner of loc. 89

JW: these bowls are referred to as being in situ in Stern et. al. (1993 v. 4). This photo was not referenced by de Vaux in his Seismic Effects discussion but it is notable that a number of them appear to be upside down indicating that they fell.

de Vaux (1973b) - Plate Xb - Piles of Dishes

from loci 89 from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xb

Plate Xb

Piles of dishes against the southern wall of loc. 89

de Vaux (1973b)

Period lb (see Fig. 7)

According to de Vaux, the sectarian settlement at Qumran acquired its definitive form when it expanded greatly in size during the reign of Alexander Jannaeus. In addition to the large number of coins of this king, six silver and five bronze Seleucid coins dating to the years around 130 E.C.E. were found in Period Ib contexts.

... According to de Vaux, the end of Period Ib was marked by an earthquake and a fire. The evidence for earthquake destruction was found throughout the settlement but is perhaps clearest in the case of one of the pools (L48-L49), where the steps and floor had split and the eastern half had dropped about 50 cm. (see Fig. 39). This crack continues through the small pool just to the north and can be traced for some distance through L40 to the north and L72 to the south. In the pantry, the wooden shelves with the stacks of dishes (L86) collapsed onto the floor (see Fig. 30). Earthquake damage was also evident in the tower, where the lintel and ceiling of one of the rooms at the ground level (L10A) had collapsed. The northwest corner of the secondary building was damaged, as indicated by another earthquake crack running diagonally from southwest to northeast through L111, L115, L118, and L126. The western edge of the large decantation basin (L132) slid into the ravine below. This evidence indicates that the site was occupied when the earthquake occurred. Presumably any human or animal victims were removed and buried when the settlement was cleared and reoccupied after the earthquake. De Vaux noted that three of the tombs he excavated in the cemetery contained secondary burials of four individuals, who he speculated were earthquake victims.

The testimony of Flavius Josephus (War 1.370-80; Ant. 15.121-47) enabled de Vaux to date the earthquake to 31 B.C.E. In addition to the earthquake damage, a layer of ash that had blown across the site when the wood and reed roofs burned indicates there had been a fire. De Vaux concluded that the earthquake and fire were simultaneous, because it was the simplest solution, but admitted that there was no evidence to confirm this. Fires often accompanied earthquakes in antiquity, because the tremors overturned lighted oil lamps. He used the numismatic evidence to support his interpretation: only 10 identifiable coins of Herod were found, all of which came from mixed contexts of Period II, where they were associated with later coins. De Vaux noted that the Herodian coins were not dated, and cited a then-recent study assigning such coins to the period after 30 B.C.E. More recently, it has been suggested that Herod's undated bronze coins were minted after 37 B.C.E.

- Fig. 8 - Plan of Phase II settlement

from Magness (2002)

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Plan of Qumran in Period II

Magness (2002)

Period II (see Fig. 8)

According to de Vaux, the buildings damaged by the earthquake and fire were not repaired immediately. Because the water system ceased to be maintained, the site was flooded and silt accumulated to a depth of 75 cm. This silt over-flowed the large decantation basin at the northwest corner of the site (L132) and spread into L130 up to the northern wall of the secondary building, growing progressively thinner towards the east. The sediment overlay the layer of ash from the fire, indicating that the period of abandonment was subsequent to the fire (and leading de Vaux to suppose that the two events — earthquake and fire — were related).

Following this period of abandonment, the site was cleared and reoccupied by the same community that had left it, as indicated by the fact that the general plan remained the same and many of the buildings seem to have been used for the same purposes as before. Most of the rooms were cleared out and debris was dumped over the slopes of a ravine to the north of the site (where it was discovered in Trench A). Debris was also thrown outside the walls of the buildings, in heaps against the north and west walls of the secondary building (north of L120 and in L124), and in L130 in the main building. This process cleared out the objects that would have helped us to identify the function of these rooms during Period Ib. Some of the damaged structures in the settlement were strengthened, while others were left filled with collapse and abandoned. The store of more than 1000 dishes in the pantry (L86), which had fallen and broken in the earthquake, was left lying on the floor at the back of the room. This area (now designated L89) was sealed off by a low stone wall that incorporated the square pillar (pier) in the center of the room. A narrow area in front of it was enclosed by poor partition walls (L87) and the floor adjacent to the doorway leading into L77 was plastered (L86). The eastern and southern walls of L89 were buttressed on the exterior by a stone revetment. The northwest corner of the secondary building, which had begun to slide into the ravine, was buttressed, as were the inner faces of the east walls of the rooms at the northeast corner of the site (L6, L47).

The tower on the northern side of the site was reinforced by the addition of a sloping stone rampart (or "glacis") around the outside of its walls. On the northern and western sides (facing outside the settlement and along the entrance passage), the rampart is 4 m. high, but it is lower and thinner on the other two sides (facing in towards the settlement). The rampart blocked two narrow windows or light slits at the ground-floor level of the tower's north side (in L10A), and obstructed the open passages around the tower in L12, L17, and L18. Because of this, the doorway between L17 and L25 (the central courtyard of the main building) was narrowed. The ground-story room inside the tower with the collapsed ceiling (L10A) was abandoned, and the door connecting it with the next room (L28) was blocked. As an aside, I note that in Humbert and Chambon's volume, L28 is illustrated only in Periods Ia and Ib; it is replaced in Period II by L11. However, a coin of the Procurators under Nero is listed from L28, which means that this locus must have existed in Period II. Perhaps L28 represents the ground-floor level in Period II, and L11 is the second-story level. In Period Ib, the locus might be L28-L29 (instead of L28).

De Vaux relied on the numismatic evidence to date the beginning of Period II. Since only 10 identifiable coins of Herod the Great were found, all from mixed contexts, he assigned them to Period II. He reasoned that these coins could have continued in circulation after Herod's death. De Vaux therefore dated the beginning of Period II to the time of Herod's son and successor, Herod Archelaus, who ruled Judea, Idumaea, and Samaria from 4 B.C.E. to 6 C.E. He based this on several considerations. First, 16 coins of Archelaus were recovered, after which point the numismatic sequence of Period II continues without interruption to the First Jewish Revolt. Second, one of Archelaus's coins was found among the debris from the buildings. This debris was dumped by the returning inhabitants when they cleared and reoccupied the site at the beginning of Period II. The fact that the other coins in this deposit all date to Period Ib and do not include any coins of Herod the Great suggests that the reoccupation of the site was undertaken during Archelaus's reign. Finally, there is the evidence provided by a hoard of 561 silver coins from L120 (a room on the north side of the secondary building), which had been placed in three pots and buried under the floor. Most of these are Tyrian tetradrachmas (sheqels) from the period after 126 B.C.E., with the most recent coin in the hoard dating to 9/8 B.C.E. (and several earlier pieces counter-marked in the same year). As de Vaux noted, this provides a terminus post quem of 9/8 B.C.E. for the burial of the hoard. Because in de Vaux's time there was thought to be a lacuna in the issues of Tyrian tetradrachmas from 9/8 B.C.E. to 1 B.C.E./1 C.E. (a gap which has since been filled), he dated the beginning of Period II to some time between 4 and 1 B.C.E. - that is, to early in the reign of Herod Archelaus. In other words, the presence of coins of Herod Archelaus provided de Vaux with a terminus post quem of 4 B.C.E., while the absence of Tyrian tetradrachmas of post--1 B.C.E. date in the hoard suggested a terminus ante quem for the beginning of Period II.

- from Magness (2002:63)

- Period Ia, from ca. 130 to 100 B.C.E.

- Period Ib, from ca. 100 B.C.E.10 31 B.C.E.

- Period II, from ca. 4-1 B.C.E. to 68 C.E

- from Magness (2002:66-69)

According to de Vaux, Qumran lay in ruins and was unoccupied for about 30 years after the earthquake of 31 B.C.E. This period of abandonment ended when the site was reoccupied between 4 and 1 B.C.E. by the same community that had inhabited it 30 years earlier. Most scholars have accepted de Vaux's chronology, though many have grappled with the problems raised by the 30-year gap in occupation. For example, it does not make sense that an earthquake would have caused the community to abandon the site for 30 years. One might expect political turmoil or unstable social conditions to cause an abandonment, but not an earthquake. In fact, scholars have wondered why the community at Qumran (assuming they were Essenes) would have felt it necessary to abandon the site, since Josephus indicates that Herod the Great held the Essenes in high regard. Also, how is it that after such a long period the site was reoccupied by the same population with the buildings being put to the same use? And where did the community go for 30 years?

Because of these problems, some scholars have suggested that the earthquake and fire were not simultaneous. They have proposed that the settlement was burned during the turbulent period of the Parthian invasion and the reign of Mattathias Antigonus (the last Hasmonean king; 40-37 B.C.E.) and then abandoned. The site would have been ruined and empty when the earthquake struck in 31 B.C.E. De Vaux argued convincingly against this suggestion, which again fails to account for the whereabouts of this community during such a long gap in occupation.

I believe that a reconsideration of the archaeological evidence and especially the coins provides a solution to these problems. As I mentioned above, only 10 identifiable coins of Herod the Great were found at Qumran, all undated bronze issues from mixed levels. Because of their small number and mixed contexts, de Vaux associated these coins with the Period II settlement, claiming that they remained in circulation after Herod's death. In fact, Herod seems to have minted relatively few coins, and as we have seen, the coins of Alexander Jannaeus remained in circulation through Herod's reign. In addition, other coins dating to Herod's time were found at Qumran. They are among the silver coins found in the hoard from L120, most of which are Tyrian tetradrachmas dating from 126 to 9/8 B.C.E. More important, however, is the context of this hoard, which de Vaux described as follows: "These three pots [containing the coins] were buried beneath the level of Period II and above that of Period Ib" (my emphasis). De Vaux associated the hoard with the reoccupation of the site at the beginning of Period II, which means that the inhabitants buried the coins when they reoccupied the site between 4-1 B.C.E. However, de Vaux's description of the context makes it clear that the hoard could equally be associated with Period Ib, and common sense suggests this is the case. Hoards are often buried in times of trouble and can remain buried if the owner fails to return and retrieve the valuables. It is reasonable to assume that the hoard at Qumran was buried because of some impending danger or threat, and remained buried because the site was subsequently abandoned for some time. For whatever reason, the hoard was never retrieved even after the site was reoccupied.

The assignment of the hoard to Period Ib suggests a different chronological sequence for the settlement at Qumran. The site was not abandoned after the earthquake of 31 B.C.E. The inhabitants immediately repaired or strengthened many of the damaged buildings but did not bother to clear those beyond repair. So, for example, the badly damaged pools in L48-L50 were abandoned, and the pottery store in the pantry (L86) was left buried beneath the collapse. The settlement of Period Ib then continued without apparent interruption until 9/8 B.C.E. or some time thereafter. The coin hoard provides a terminus post quem of 9/8 B.C.E. for the abandonment of the site. The fact that the hoard was buried, combined with the presence of a layer of ash, suggests that the fire which destroyed the settlement should be attributed to human agents instead of to natural causes. In other words, in 9/8 B.C.E. or some time thereafter, Qumran suffered a deliberate, violent destruction. Such a destruction better accounts for the abandonment of the site by the inhabitants. However, it was not the prolonged abandonment postulated by de Vaux. Instead, the site was abandoned in 9/8 B.C.E. or some time thereafter and reoccupied early in the reign of Herod Archelaus in 4 B.C.E. or shortly afterwards. On the basis of the presently available evidence, it is impossible to narrow the range any further. The fact that the water system fell into disrepair and silt covered the site (carried by the flash flood waters through the aqueduct) indicates that the abandonment lasted for at least one winter season. The site was abandoned for a period of one winter season to several years, within a range from 9/8 B.C.E. to some time early in the reign of Herod Archelaus. Since it is impossible to pinpoint the date, the causes leading to the destruction of the site must remain unknown, though it is tempting to associate them with the revolts and turmoil which erupted in Judea upon the death of Herod the Great in 4 B.C.E.

A short period of abandonment better accounts for the fact that the site was reoccupied and put to the same use as before by the same community. It also solves the problem of accounting for the whereabouts of this community for 30 years. When the inhabitants returned to the site, they cleared away the silt and destruction debris and dumped them in various places outside the settlement. As I mentioned, de Vaux used a coin of Herod Archelaus from one of these dumps as evidence for dating the reoccupation of the site to the be-ginning of that king's reign, which was in 4 B.C.E. He suggested that this coin was lost during the work of clearance. My revised chronological sequence means that de Vaux's Period Ib should be subdivided into a pre-31 and post-31 B.C.E. phase. De Vaux's description of the hoard's context suggests that its burial should be associated with the post-31 B.C.E. phase of Period Ib, a phase that he did not recognize (the coins were buried "beneath the level of Period II and above that of Period Ib"). This revised sequence also means that some if not all of the remains de Vaux associated with Period Ia might belong to the pre-earthquake phase of Period Ib. The following diagram compares my revised chronology with that of de Vaux:

Revised Chronology for Qumran from Magness (2002)

Revised Chronology for Qumran from Magness (2002)

A few nicely cut architectural elements that were reused in Period III and II contexts were found in various places around the site:

- one column drum (a drum is part of the column shaft) in L6 (Period II or III)

- two column drums and one column base in L14 (Period III)

- a stone from a pier and a voussoir (a stone belonging to an arch or vault) in L19 (Period III)

- two column drums, several voussoirs, and a console (the springing stone of an arch) built into the base of the wall between L23 and 33 (in the central courtyard of the main building) (Period III)

- one column drum in L24 (Period III)

- a frieze fragment found just south of L34

- a cornice block in L42 (Period III)

- one column drum and two large, nicely cut stone blocks at the bottom of pool L49 (Period II or the post-31 B.C.E. phase of Period Ib?)

- one column drum in pool L56 (Period III)

- two column bases in L100

- one column drum and a base in L102 (Period III?)

- one column drum in L120 (Period III?) (see Fig. 27)

- Some Seismic Effects of de Vaux (1973) are disputed

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faulted Staircase | Cistern 48-49

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumranphoto by Jefferson Williams

Plate XVI

Plate XVICistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west. de Vaux (1973b) |

The steps and the floor of the largest of these cisterns, locs. 48, 49 (Pl. XVI) have been split and the whole of the eastern part has sunk to about 50 cm. lower than the western part.- de Vaux (1973:20) |

| Fractured Cistern | Cistern 48-49-50

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumranphoto by Jefferson Williams

Plate XVI

Plate XVICistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west. de Vaux (1973b) |

|

| Fractured Wall | Eastern Wall of Tower

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12Plan of the Tower Magness (2002) |

The tower was shaken; its eastern wall was cracked.- de Vaux (1973:20) |

|

| Lintel and ceiling collapse | lower chamber of the Tower - L10A (Magness, 2002:56)

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

|

|

| Wall damage at a corner | NW corner of secondary building

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7Plan of Qumran in Period Ib Magness (2002) |

|

|

| Broken Pottery found in fallen position | pantry - SE corner of loci 89

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

Plate Xa

Plate XaBroken Bowls in the south-eastern corner of loc. 89 JW: these bowls are referred to as being in situ in Stern et. al. (1993 v. 4). This photo was not referenced by de Vaux in his Seismic Effects discussion but it is notable that a number of them appear to be upside down indicating that they fell. de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xb

Plate XbPiles of dishes against the southern wall of loc. 89 de Vaux (1973b) |

|

| Re-used building elements | elements were distributed throughout the site and their original location is unknown- Magness (2002:69)

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

Fig. 27

Fig. 27Column bases in the southern part of the secondary building Magness (2002) |

Description

|

- Cracked Steps at Qumran -

photo by Jefferson Williams

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumran

photo by Jefferson Williams - Plate XVI - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XVI

Plate XVI

Cistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 39 - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from Magness (2002:56)

Fig. 39

Fig. 39

View of the miqveh in L48-L49. Notice the low, plastered partitions on the steps, and the earthquake damage which has caused the left-hand side of the steps to drop

Magness (2002) - Plate Xa - Broken Pottery -

some upside down - from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xa

Plate Xa

Broken Bowls in the south-eastern corner of loc. 89

JW: these bowls are referred to as being in situ in Stern et. al. (1993 v. 4). This photo was not referenced by de Vaux in his Seismic Effects discussion but it is notable that a number of them appear to be upside down indicating that they fell.

de Vaux (1973b)

de Vaux (1973:20) described seismic effects which includes a footnote which speaks to the debates over his seismic interpretation:

With regard to the end of Period Ib we have two pieces of evidence : an earthquake and a fire. The effects of the earthquake are particularly apparent in the two cisterns situated in the eastern area of the main building. The steps and the floor of the largest of these cisterns, locs. 48, 49 (Pl. XVI) have been split and the whole of the eastern part has sunk to about 50 cm. lower than the western part. There was a vertical cleavage which left the walls standing, although the north wall of the cistern was split from top to bottom and its eastern portion sank following the movement of the earth. The crack was prolonged into the neighbouring cistern, loc. 50, the floor of which was clearly torn away, and the track of it can be traced right across the ruins of this period to the north and south of the two cisterns. Other parts of the buildings were equally affected. The tower was shaken; its eastern wall was cracked. The lintel and ceiling of the lower chamber fell in. The north-west corner of the secondary building was likewise damaged, and was in danger of collapsing into the ravine immediately below it. In the southern region the signs are less clear, except in the annexe of the large room, the back of which fell in, burying the pottery store of which we have spoken1.Magness (2002:56) summarized de Vaux's paragraph as follows:Footnotes1. Cf. Revue biblique, LXI (1954), 210 and 231-2; LXIII (1956), 544. In two articles, `The Qumran Sect in Relation to the Temple of Leontopolis', Revue de Qumran, VI, I (Feb. 1967), esp. 69, and `Marginal Notes on the Qumran Excavations', ibid., vn, 1 (Dec. 1969), esp. 33-4, S. H. Steckoll attributes the following opinion to T. Zavislock, the expert attached to the English Historical Monuments Service, who directed the measures of conservation at Khirbet Qumran: that there was neither an earthquake nor any cessation in the occupation at Qumran. The faults in the cisterns at 48, 49, 5o would have been caused `by the weight of water introduced upon the first use after the building or repair of these cisterns'. I do not know whether this represents an accurate account of the opinion of T. Zavislock. In any case this explanation cannot be accepted.

According to de Vaux, the end of Period lb was marked by an earthquake and a fire. The evidence for earthquake destruction was found throughout the settlement but is perhaps clearest in the case of one of the pools (L48-L49), where the steps and floor had split and the eastern half had dropped about 50 cm. (see Fig. 39). This crack continues through the small pool just to the north and can be traced for some distance through L40 to the north and L72 to the south. In the pantry, the wooden shelves with the stacks of dishes (L86) collapsed onto the floor (see Plate Xa). Earthquake damage was also evident in the tower, where the lintel and ceiling of one of the rooms at the ground level (L10A) had collapsed. The northwest corner of the secondary building was damaged, as indicated by another earthquake crack running diagonally from southwest to northeast through L111, L115, L118, and L126. The western edge of the large décantation basin (L132) slid into the ravine below. This evidence indicates that the site was occupied when the earthquake occurred. Presumably any human or animal victims were removed and buried when the settlement was cleared and reoccupied after the earthquake. De Vaux noted that three of the tombs he excavated in the cemetery contained secondary burials of four individuals, who he speculated were earthquake victims.

- Modified by JW from Plate XXXIX of de Vaux (1973b)

Deformation Map

Deformation Mapmodified by JW from Plate XXXIX of de Vaux (1973b)

- Some Seismic Effects of de Vaux (1973) are disputed

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faulted Staircase | Cistern 48-49

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumranphoto by Jefferson Williams

Plate XVI

Plate XVICistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west. de Vaux (1973b) |

The steps and the floor of the largest of these cisterns, locs. 48, 49 (Pl. XVI) have been split and the whole of the eastern part has sunk to about 50 cm. lower than the western part.- de Vaux (1973:20) |

? |

| Fractured Cistern | Cistern 48-49-50

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumranphoto by Jefferson Williams

Plate XVI

Plate XVICistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west. de Vaux (1973b) |

|

? |

| Fractured (displaced) Wall | Eastern Wall of Tower

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12Plan of the Tower Magness (2002) |

The tower was shaken; its eastern wall was cracked.- de Vaux (1973:20) |

VII+ | |

| Lintel and ceiling collapse | lower chamber of the Tower - L10A (Magness, 2002:56)

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

|

VII+ | |

| Wall damage at a corner | NW corner of secondary building

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7Plan of Qumran in Period Ib Magness (2002) |

|

VII+ | |

| Broken Pottery found in fallen position | pantry - SE corner of loci 89

Plate XXXIX

Plate XXXIXKhirbet Qumran: schematic plan and position of the loci in Periods Ib and II. JW: de Vaux interpreted a N-S trending fault which is drawn traversing the east side of the compound. de Vaux (1973b) |

Plate Xa

Plate XaBroken Bowls in the south-eastern corner of loc. 89 JW: these bowls are referred to as being in situ in Stern et. al. (1993 v. 4). This photo was not referenced by de Vaux in his Seismic Effects discussion but it is notable that a number of them appear to be upside down indicating that they fell. de Vaux (1973b)

Plate Xb

Plate XbPiles of dishes against the southern wall of loc. 89 de Vaux (1973b) |

|

VII+ |

Baigent, M. and Eisenmann, R. (2000). "A Ground-Penetrating Radar Testing the Claim for Earthquake Damage of the Second Temple Ruins at Khirbet Qumran." The Qumran Chronicle 9(No.2/4): 131-137.

Broshi, M. (1992). THE ARCHEOLOGY OF QUMRAN — A RECONSIDERATION, Brill: 103-115.

Karcz, I. (2004). "Implications of some early Jewish sources for estimates of earthquake hazard in the Holy Land." Ann. Geophys. 47: 759–792.

Magen, I. and Peleg, P. (2018). "Back to Qumran : final report (1993-2004). Jerusalem : Israel Antiquities Authority

Magen, Y and Peleg, Y (2007), The Qumran Excavations, 1993-2004: Preliminary Report. Jerusalem : Israel Antiquities Authority

Magness, J. (2002). The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls, William B. Eerdmans Pub.

Magness, J. (2004). Debating Qumran: Collected Essays on Its Archaeology, Isd.

Salamon, Amos (2004). Seismically induced ground effects of the February 11, 2004, ML=5.2, northeastern Dead Sea earthquake. Jerusalem, Geological Survey of Israel.

Trstensky, F, THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF QUMRAN AND THE PERSONALITY OF Roland de Vaux

de Vaux, R. (1973a). Archeology of the Dead Sea Scrolls. London, Oxford University Press.

de Vaux, R. (1973b). Archeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls The Schweich Lectures 1959 Revised edition in an English translation. London, Oxford University Press. -

open access at archive.org

Hirschfeld, Y. (2004b). "Excavations at 'Ein Feshka, 2001: Final Report." Israel Exploration Journal(54): 37-74.

R. de Vaux, L'Archeo!ogie et les manuscrits de Ia Mer Marte, London 1961

id.,

Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Schweich Lectures of the British Academy), London 1973

J. T.

Milik, Ten Years of Discovery in the Wilderness of Judaea, London 1959

E.-M. Laperrousaz, Qoumran:

l'Etablissment Esst?nien des Bard de Ia Mer M orte, Histoire et Archt?ologie du Site, Paris 1976

Discoveries in

the Judaean Desert 6-7, Oxford 1977-1982.

R. de Vaux, RB 56 (1949), 234-237, 586-609

60 (1953), 83-106, 540-561

61 (1954), 206-

236

63 (1956), 533-577

66 (1959), 225-255

S. Schulz, ZDPV 75 (1960), 50-72

H. Hardtke, TLZ 85

(1960), 263-274

J. B. Pool and R. Reed, PEQ 93 (1961), 114-123

J. A. Fitzmeyer, The Dead Sea Scrolls:

Major Publications and Tools for Study (Sources for Biblical Study 8), Missoula, Mont. 1975

H. T. Frank,

BAR 1/4 (1975), I, 7-16, 28-30

E.-M. Laperrousaz, Qoumran (Review), BASOR 231 (1978), 79-80

id.,

Revue de Qumran46(1986), 199-212

id.,E/20(1989), 118*-123*

F. M. Cross, Jr., BAR3jl (1977), 1,23-

32

id., Bible Review 1/2 (1985), 12-25

1/3 (1985), 26-35

J. Murphy-O'Connor, BA 40 (1977), 125-129;

G. Vermes, The Dead Sea Scrolls: Qumran in Perspective, London 1977

id., BAlAS 1984-1985, 20-23;

MdB4 (1978)

J. Licht, IEJ29 (1979), 45-59

M. Sharabani, RB87 (1980), 274-284

P.R. Davies, Qumran

(Cities of the Biblical World), Guildford, Surrey 1982

id., BA 51 (1988), 203-207

American Archaeology

in the Mideast, 118

J. C. Violette, Les Esseniens de Qoumrdn (Les Partes de l'Etrange), Paris 1983;

S. Bowman, Revue de Qumran 44 (1984), 543-547

N. Golb, BA 48 (1985), 68-82

id., The American

Scholar 58 (1989), 177-207

id., JNES 49 (1990), 103-114

M. Weinfeld, The Organizational Pattern and

the Penal Code of the Qumran Sect (Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus 2), Fribourg 1986

ibid.

(Review), Revue de Qumran 14/53 (1989), 147-148

B. G. Wood, BASOR256 (1984), 45-60

M. Wise, ibid.

49 (1986), 140-154

Archi!ologie, Art et Histoire de Ia Palestine: Colloque du Centenaire de Ia Section des

Sciences Religieuses, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Sept. 1986 (ed. E.-M. Laperrousaz), Paris 1988,

149-165

G. J. Brooke, Revue de Qumran 13/49-52 (1988) 225-237

P.R. Callaway, The History of the

Qumran Community: Investigation (Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha Supplement Series 3),

Sheffield 1988

F. Dionisio, Bibbia e Oriente, !56 (1988), 85-110

P. Crocker, Buried History 25 (1989), 36-

46

E. Lipinski, E/20 (1989), 130*-134*

D. Chen, lOth World Congress of Jewish Studies B/2, Jerusalem

1990, 9-14

JNES49/2 (1990)

L. H. Schiffman, BA 53 (1990), 64-73

S. Goranson, ibid. 54(1991), 110-

111

Discoveries in the Judaean Desert 1–ff, Oxford 1955–ff

Studies on the Texts of the

Desert of Judah, 1–ff, Leiden 1957–ff

Revue de Qumran, 1–ff (1958–ff)

The Qumran Chronicle 1–ff

(1990–ff)

The Dead Sea Scrolls, 40 Years of Research (eds. Dvorah Dimant & U. Rappaport), Leiden 1992;

H. Shanks, Understanding the Dead Sea Scrolls: A Reader from the Biblical Archaeology Review, New

York 1992

Scrolls from the Dead Sea/The Dead Sea Scrolls: An Exhibition of Scrolls and Archaeological

Artifacts from the Collections of the Israel Antiquities Authority (eds. A. Sussman & R. Peled), Washington,

D.C. 1993

ibid., St. Gallen 1999

ibid., Chicago, IL 2000

ibid., New South Wales 2000

ibid. (ed. E. Middlebrook Herron), Grand Rapids, MI 2003

Dead Sea Discoveries, 1–ff (1994–ff)

J. -B. Humbert (& A.

Chambon), Fouilles de Khirbet Qumrân et de Aïn Feshkha, 1: Album de photographies, répertoire du fonds

photographique, synthèse des notes de chantier du Père Roland de Vaux (Novum Testamentum et Orbis

Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 1), Fribourg 1994

ibid. (Reviews) BAR 21/1 (1995), 6, 8. — Dead Sea Discoveries 3 (1996), 342–345. — Orientalische Literaturzeitung 91 (1996), 532–540. — PEQ 128 (1996),

176–177. — The Qumran Chronicle 6 (1996), 188–194. — Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana 72 (1996),

426–427

id. & J. Gunneweg et al., Khirbet Qumrân et ‘Aïn Feshkha, 2: Études d’anthropologie, de physique et de chimie—Studies of Anthropology, Physics and Chemistry (Novum Testamentum et Orbis

Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 3), Fribourg 2003

ibid. (Reviews) BAR 30/6 (2004), 60–61. — Levant 37

(2005), 239

Methods of Investigation of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Khirbet Qumran Site: Present Realities and Future Prospects (Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 722

eds. M. O. Wise et al.), New

York 1994

ibid. (Reviews) BASOR 303 (1996), 102–103. — Dead Sea Discoveries 4 (1997), 241–243

F.

M. Cross, The Ancient Library of Qumran, 3rd ed., Minneapolis 1995

ibid. (Reviews), The Qumran Chronicle 5 (1995), 173–175. — Dead Sea Discoveries 3 (1996), 68–70

F. Garcia Martinez & J. Trebolle Barrera,

The People and the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Writings, Beliefs and Practices, Leiden 1995

ibid. (Review)

BAR 23/2 (1997), 62–63

N. Golb, Who Wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls? The Search for the Secret of Qumran,

New York 1995

V. Jones, Qumran Excavations: Cave of the Column Complex and Environs, Arlington, TX

1995

Mogilany: International Colloquium on the Dead Sea Scrolls (Qumranica Mogilanensia), 1–ff, Cracow 1995–ff

A Bibliography of the Finds in the Desert of Judah, 1970–1995 (Studies on the Texts of the

Desert of Judah 19

comps. F. Garcia Martinez & D. W. Parry), Leiden 1996

R. De Vaux, Die Ausgrabungen von Qumran und En Feschcha, 1A: Die Grabungstagebücher (Novum Testamentum & Orbis Antiquus,

Series Archeologica 1A), Freiburg 1996

ibid. (Review) RB 106 (1999), 114–125

Orion Center for the

Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Associated Literature, International Symposium, 1–ff, Jerusalem &

Leiden 1996–ff

L. Cansdale, Qumran and the Essenes: A Re-evaluation of the Evidence (Texte und Studien

zum Antiken Judentum 60), Tübingen 1997

ibid. (Reviews) Dead Sea Discoveries 5 (1998), 99–104. RB

105 (1998), 281–285. — Revue de Qumran 18/71 (1998), 437–441. — JQR 89 (1998–1999), 411–414. —

Bibliotheca Orientalis 57 (2000), 166–169. — PEQ 132 (2000), 80. — The Polish Journal of Biblical

Research 1 (2001), 219–220. — ZDPV 117 (2001), 79–81

The Scrolls and the Scriptures: Qumran Fifty

Years After (Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha, Suppl. Series 26

Roehampton Institute London

Papers 3), Sheffield 1997

A. Roitman, A Day at Qumran: The Dead Sea Sect and its Scrolls (Israel

Museum, Catalogue 394), Jerusalem 1997

Caves of Enlightenment: Proceedings of the ASOR Dead Sea

Scrolls Jubilee Symposium (1947–1997) (ed. J. H. Charlesworth), North Richland Hills, TX 1998

Qumran

(Welt und Umwelt der Bibel 9), Stuttgart 1998

Qumran Between the Old and New Testaments (JSOT

Suppl. Series 290

Copenhagen International Seminar 6

eds. F. H. Cryer & T. L. Thompson), Sheffield

1998

Die Schriftrollen von Qumran: zur aufregenden Geschichte ihrer Erforschung und Deutung (ed. S.

Talmon), Regensburg 1998

H. Stegemann, The Library of Qumran: On the Essenes, Qumran, John the

Baptist and Jesus, Leiden 1998

The Dead Sea Scrolls at Fifty: Proceedings of the 1997 Society of Biblical

Literature Qumran Section Meetings (Early Judaism and its Literature 15

eds. R. A. Kugler & E. M. Schuller), Atlanta, GA 1999

ibid. (Reviews) JAOS 121 (2001), 300–301. — JNES 62 (2003), 224

The Provo

International Conference on the Dead Sea Scrolls: Technological Innovations, New Texts and Reformulated

Issues (Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah 30

eds. D. W. Parry & E. Ulrich), Leiden 1999

The

Dead Sea Scrolls Fifty Years After Their Discovery: Major Issues and New Approaches. Proceedings of the

Jerusalem Congress, The Israel Museum, 20–25.7.1997 (eds. L. H. Schiffman et al.), Jerusalem 2000

ibid.

(Reviews) BASOR 329 (2003), 96–97. — IEJ 53 (2003), 139–141. — JNES 62 (2003), 224. — Dead Sea

Discoveries 11 (2004), 122–127

The Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls (eds. L. H. Schiffman & J. C.

VanderKam), Oxford 2000

ibid. (Review) Revue de Qumran 20/77–78 (2001), 133–136

Jericho und Qumran: Neues zum Umfeld der Bibel (Eichstätter Studien, N.F. 45

ed. B. Mayer), Regensburg 2000

ibid.

(Review) BASOR 329 (2003), 94–96

Józef Tadeusz Milik et cinquantenaire de la découverte des manuscrits de la Mer Morte de Qumrân (eds. D. ‘Dlugosz & H. Ralajczak), Varsovie 2000

E. M. Laperrousaz,

Qoumran et les manuscrits de la Mer Morte: un cinquantenaire, rev. & exp. ed., Paris 2000

The Dead Sea

Scrolls in Their Historical Context (eds. T. H. Lim et al.), Edinburgh 2000

ibid. (Review) Bibliotheca Orientalis 60 (2003), 181–186

Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls (NEA 63/3), Boston 2000

Archaeology and

Society in the 21st Century: The Dead Sea Scrolls and Other Case Studies (eds. N. A. Silberman & E. S.

Frerichs), Jerusalem 2001

ibid. (Review) Dead Sea Discoveries 9(2002), 268–271

Qumran: die Schriftrollen vom Toten Meer: Vortäge des St. Galler Qumran-Symposiums, 2–3.7.1999 (eds. M. Fieger et al.),

Freiburg 2001

J. H. Charlesworth, The Pesharim and Qumran History: Chaos or Consensus?, Grand Rapids, MI 2002

The Complete World of the Dead Sea Scrolls, London 2002

Copper Scroll Studies (Journal

for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha Suppl. Series 40

eds. G. J. Brooke & P. R. Davies), London 2002

R.

Donceel, The Khirbet Qumran Cemeteries: A Synthesis of the Archaeological Data (The Qumran Chronicle

10), Cracow 2002

M. & K. Lönnqvist, Archaeology of the Hidden Qumran: The New Paradigm, Helsinki

2002

ibid. (Review) Journal of Jewish Studies 54 (2003), 153–154

J. Magness, The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Literature), Grand Rapids, MI

2002

ibid. (Reviews) BAR 29/4 (2003), 62, 64. — JAOS 123 (2003), 652–654. — JRA 16 (2003), 648–652.

— AJA 108 (2004), 118–119. — BAIAS 22 (2004), 60–67. — BASOR 333 (2004), 92–94. — Dead Sea Discoveries 11 (2004), 361–372. — NEAS Bulletin 49 (2004), 57–59. — PEQ 136 (2004), 81–87

id., Debating

Qumran: Collected Essays on its Archaeology (Interdisciplinary Studies in Ancient Culture and Religion 4),

Leuven 2004

The Complete World of the Dead Sea Scrolls (eds. P. R. Davies et al.), New York 2002

ibid.

(Review), Archaeology Odyssey 7/2 (2004), 58–59

Les Manuscrits de la Mer Morte (Le Livre de Poche

30137

eds. F. Mebarki & É. Puech), Rodez 2002

The Excavations of Khirbet Qumran and Ain Feshkha:

Synthesis of Roland de Vaux’s Field Notes, I/B (Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 1/B

eds. J. -B. Humbert & A. Chambon

tr. & rev. S. J. Pfann), Fribourg 2003

Meghillot: Studies in the

Dead Sea Scrolls, 1–ff (2003–ff) (Eng. abstracts)

Y. Hirschfeld, Longing for the Desert: The Dead Sea Valley in the Second Temple Period (Judaism: Here and Now), Tel Aviv 2004 (Heb.)

id., Qumran in Context:

Reassessing the Archaeological Evidence, Peabody, MA 2004

ibid. (Review) BASOR 340 (2005), 94–95.

G. Bonani, Radiocarbon 34 (1992), 843–849

M. Broshi, The Dead Sea Scrolls, 40 Years of

Research (op. cit.), Leiden 1992, 103–115, 124

id. (& H. Eshel), MdB 107 (1997), 16–18

id. Dead Sea

Discoveries 6 (1999), 328–348 (with H. Eshel)

11 (2004), 133–142

id. (& H. Eshel), The Provo International Conference on the Dead Sea Scrolls (op. cit.), Leiden 1999, 267–273

id., NEA 63 (2000), 136–137;

id., Revue de Qumran 19/74 (2000), 273–276

id., Bread, Wine, Walls and Scrolls (Journal for the Study of

the Pseudepigrapha Suppl. Series 36), Sheffield 2001

id., Cathedra 100 (2001), 402

109 (2003), 192–193;

114 (2004), 177

id., Les manuscrits de la Mer Morte (op. cit.), Rodez 2002, 149–157

id., BAR 29/2 (2003),

62–63

30/1 (2004), 32–37, 64

id. (& H. Eshel), Religion and Society in Roman Palestine: Old Questions,

New Approaches (ed. D. R. Edwards), London 2004, 162–169

L. Cansdale, The Qumran Chronicle 2

(1992), 117–125

4 (1994), 157–168

P. Donceel-Voûte, Banquets d’Orient, Leuven 1992, 61–84

id., Res

Orientales 4 (1992), 61–84

11 (1998), 93–124

id., Archéologia 298 (1994), 24–35

id., La mosaïque

gréco-romaine 8: Actes du 8. Colloque International pour l’Étude de la Mosaïque Antique et Médiévale,

Lausanne, 6–11.10.1997 (Cahiers d’archéologie romande 86

eds. D. Paunier & C. Schmidt), 2, Lausanne

2001, 490–509

R. Donceel, RB 99 (1992), 557–573

id., OEANE, 4, New York 1997, 392–396

id., Mogilany 1995 (1998), 87–104

id., Bulletin de l’Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique 28 (1999–2000), 9–40;

S. C. Goranson, Michmanim 6 (1992), 37*–40*

id., BAR 19/6 (1993), 67

20/5 (1994), 36–39

Z. J. Kapera,

The Qumran Chronicle 2 (1992), 73–84

5 (1995), 6–9, 123–132

6 (1996), 93–114

9 (2000), 35–49, 139–

151

id., Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny 49 (1996), 18–28

id., Zydzi I Judaizm we wspolczesnych badaniach

Polkich, 1: Materialy z Konferencji, Krakow, 21–23.11.1995 (ed. K. Pilarczyk), Krakow 1997, 81–89

id.,

Mogilany 1998, 15–33

E. -M. Laperrousaz, Mogilany 1992, 109–129

J. Murphy-O’Connor, ABD, 5, New

York 1992, 590–594

D. Walker (& R. Eisenman), The Qumran Chronicle 2 (1992), 45–49

3 (1993), 93–

100

G. J. Brooke, BAIAS 12 (1992–1993), 84–86

id., PEQ 125 (1993), 74, 158–160 (Review)

H. Eshel (&

Z. Greenhut), RB 100 (1993), 252–259

id., JSRS 4 (1994), xiii–xiv, 16

10 (2001), xi

id., Orion Center

International Symposium (op. cit.) 5, Leiden 2000, 45–52

id., Copper Scroll Studies (Journal for the Study

of the Pseudepigrapha Suppl. Series 40

eds. G. J. Brooke & P. R. Davies), London 2002, 92–107

id., Journal of Religious History 26 (2002), 179–188

id., Cathedra 109 (2003), 193

id. (& M. Broshi), IEJ 53

(2003), 61–73

A. S. Kaufman, Niv Hamidrashia 24–25 (1993), 51–56

J. Patrich, Annals of the New York

Academy of Science 1993, 113–132

id., ESI 13 (1993), 64

id., Methods of Investigations of the Dead Sea

Scrolls (op. cit.), New York 1994, 73–95

id., 11th World Congress of Jewish Studies, A, Jerusalem 1994;

id., The Dead Sea Scrolls Fifty Years after Their Discovery (op. cit.), Jerusalem 2000, 720–727

G. A. Rodley, Radiocarbon 35 (1993), 335–338

H. Shanks, BAR 19/3 (1993), 62–65

27/6 (2001), 20

28/4 (2002),

19–17, 60

id., On Scrolls, Artefacts and Intellectual Property (Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha,

Suppl. Series 38

eds. T. H. Lim et al.), Sheffield 2001, 63–73

J. C. Trever, Mogilany 1993, 71–78

A. D.

Crown & L. Cansdale, BAR 20/5 (1994), 24–35, 73–74

P. R. Davies, Scripture and Other Artifacts, Louisville, KY 1994, 126–142

D. Fernandez-Galiano, Los manuscritos del Mar Muerto: balance de hallazgos y

de cuarenta anos estudios (eds. A. Pinero & D. Fernandez-Galiano), Cordoba 1994, 51–77

J. -B. Humbert,

MdB 86 (1994), 14–21

151 (2003), 50–51

id., RB 101 (1994), 161–121

id., Antike Judentum und frühes

Christentum (H. Stegemann Fest.

Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Kunde der älteren Kirche 97

eds. B.

Kollmann et al.), Berlin 1999, 183–196

J. Magness, Methods of Investigations of the Dead Sea Scrolls (op.

cit.), New York 1994, 39–48

id., Revue de Qumran 16/63 (1994), 397–419

id., Dead Sea Discoveries 2

(1995), 58–65

id., BAR 22/6 (1996), 38, 40–47, 72–73

23/3 (1997), 12–13

id., The Qumran Chronicle 7

(1997), 1–10

8 (1998), 49–62

id., BASOR 312 (1998), 37–44

id., Mogilany 1998, 55–76

id., The Dead

Sea Scrolls Fifty Years after Their Discovery (op. cit.), Jerusalem 2000, 47–77, 708–719

id., Shaping Community: The Art and Archaeology of Monasticism: Papers from a Symposium, University of Minnesota,

10–12.3.2000 (BAR/IS 941

ed. S. McNally), Oxford 2001, 15–28

id., What Athens Has to Do with Jerusalem, Leuven 2002, 89–123

id., MdB 151 (2003), 15–18

id., Minerva 14/2 (2003), 29–30

id., Religion

and Society in Roman Palestine: Old Questions, New Approaches (ed. D. R. Edwards), London 2004, 146–

161

MdB 86 (1994), 2–42

107 (1997), 1–73

J. Perrot & M. Broshi, Les Dossiers d’Archeologie 189

(1994), 4–39

S. J. Pfann, RB 101 (1994), 212–214

id., Copper Scroll Studies (Journal for the Study of the

Pseudepigrapha Suppl. Series 40

eds. G. J. Brooke & P. R. Davies), London 2002, 163–180

É. Puech,

Revue de Qumran 16/3 (63) (1994), 463–471

N. A. Silberman, Archaeology 47/2 (1994), 27–28

47/6

(1994), 30–40

R. Bertholon et al., Restauration, de-restauration: Colloque sur la conservation, restauration des biens culturels, Paris, 5–7.10.1995, Paris 1995, 295–306

id. (et al.), Metal 98: Proceedings of the

International Conference on Metals Conservation (eds. W. Mourey & L. Robbiola), London 1998, 125–135;

M. Goodman, Journal of Jewish Studies 46 (1995), 161–166

J. Picca, Tra Giudaismo e Cristianesimo (ed.

A. Straus), Roma 1995, 15–42

R. Reich, Journal of Jewish Studies 46 (1995), 157–160

id., The Dead Sea

Scrolls Fifty Years after Their Discovery (op. cit.), Jerusalem 2000, 728–731

BAR 22/2 (1996), 10, 12

24/1

(1998), 24–37, 78, 81–84

25/5 (1999), 48–53, 76

P. R. Callaway, Mogilany 1996, 15–30

id., The Qumran

Chronicle 7 (1997), 145–170

8 (1998), 21–47, 169–170

E. M. Cook, BAR 22/6 (1996), 39, 48–51, 73–75;

Y. Nir-el (& M. Broshi), Archaeometry 38 (1996), 97–102

id., Dead Sea Discoveries 3 (1996), 157–167

A.

Strobel, Orientalistische Literaturzeitung 91 (1996), 532–540

B. E. Thiering, The Qumran Chronicle 6

(1996), 115–124

id., Dead Sea Discoveries 9 (2002), 347–363

id., Copper Scroll Studies (op. cit.), London

2002, 276–287

M. Albani & U. Glessmer, RB 104 (1997), 88–115

J. R. Bartlett, Archaeology and the Biblical Interpretation (ed. J. R. Bartlett), London 1997, 67–94

E. Barzilay & N. Tal, JSRS 7 (1997), xxviii

R.

Bergmier, ZDPV 113 (1997), 75–87

A. M. Berlin, BA 60 (1997), 2–51

H. M. Cotton & A. Yardeni, Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek Documentary Texts from Nahal Hever and Other Sites (Discoveries in the Judaean

Desert 27), Oxford 1997

F. M. Cross & E. Eshel, IEJ 47 (1997), 17–28

id., BAR 24/2 (1998), 48–53, 69

F.

H. Cryer, Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 11 (1997), 232–240

A. Demsky, Dead Sea Discoveries 4 (1997), 157–161

J. Konik & M. Kisielewicz, The Qumran Chronicle 7 (1997), 97–104

Z. U. Ma’oz,

BAR 23/3 (1997), 11–12

L. P. Ritmeyer, ibid., 13

B. Rochman, ibid. 23/4 (1997), 20

Y. Roman, Eretz 53

(1997), 16–28, 67–68

S. Shapiro, The Qumran Chronicle 7 (1997), 93–115, 215–223

M. W. Wise, OEANE,

2, New York 1997, 118–127

A. Yardeni, BAR 24/3 (1998), 44–47

id., IEJ 47 (1997), 233–237

J. E. Taylor

(& T. Higham), ibid., 83–96

48 (1998), 83–104

id., Dead Sea Discoveries 6 (1999), 285–323

id., PEQ

134 (2002), 144–164

137 (2005), 159–167 (et al.)

id., BAIAS 21 (2003), 101–103

Z. Amar, Dead Sea Discoveries 5 (1998), 1–15

F. Garcia Martinez, MdB 113 (1998), 76

Y. Hirschfeld, JNES 57 (1998), 161–189;

id., The Dead Sea Scrolls Fifty Years after Their Discovery (op. cit.), Jerusalem 2000, 673–683

id., TA 27

(2000), 286–291

id., LA 52 (2002), 247–296

id., Cathedra 109 (2003), 193

id., JRA 16 (2003), 648–652;

id., IEJ 54 (2004), 37–74

I. Hutchesson, The Qumran Chronicle 8 (1998), 177–194

A. H. Levy, BAR 24/4

(1998), 18–23

J. Naveh, IEJ 48 (1998), 252–261

Y. Porat, ESI 18 (1998), 84

F. Rohrhirsch, Folia Orientalia 34 (1998), 71–94

id., Dead Sea Discoveries 6 (1999), 267–281

id. (& O. Rohrer-Ertl), ZDPV 117

(2001), 164–170

K. A. D. Smelik, Bijdragen: International Journal of Philosophy and Theology 59 (1998),

204–234

E. Ullmann-Margalit, Social Research 65 (1998), 839–870

A. Aerts et al., JAS 26 (1999), 883–

891

id., La route du verre: ateliers primaires et secondaires du 2. millenaire af. J.-C. au Moyen Age

(Travaux de la Maison de l’Orient 33

ed. M. -D. Nenna), Lyon 2000, 113–122

J. M. Beyer, Antike Welt

30/1 (1999), 67–70

G. Hagenow, Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 6 (1999), 92–108

J. Gunneweg, Orion Center International Symposium (op.

cit.) 4, Leiden 1999, 179–185

N. Marchetti & L. Nigro, Les Dossiers d’Archeologie 240 (1999), 106–112;

S. Weitzmann, JAOS 119 (1999), 35–45

J. K. Zangenberg, RB 106 (1999), 114–125 (Review)

id., Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 10 (2004),

100–112

id., Religion and Society in Roman Palestine: Old Questions, New Approaches (ed. D. R.

Edwards), London 2004, 170–187

D. Amit & J. Magness, TA 27 (2000), 273–285

M. Baigent & R. H.

Eisenman, The Qumran Chronicle 9 (2000), 131–138

P. R. Davies, ibid., 105–122

R. Eisenman, ibid.,

123–130

Z. Safrai, Cathedra 96 (2000), 189

R. Van de Water, Revue de Qumran 19/75 (2000), 423–439;

M. Burdajewicz, ASOR Newsletter 51/3 (2001), 14

D. Dorner, On Scrolls, Artefacts and Intellectual Property (Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha Suppl. Series 38

eds. H. L. MacQueen & C. M.

Carmichael), Sheffield 2001, 26–62

N. Liphshitz & G. Bonani, TA 28 (2001), 305–309

J. Maier, Qumran:

die Schriftrollen von Toten Meer (op. cit.), Freiburg 2001, 23–95

Y. Rapuano, IEJ 51 (2001), 48–56

J. F.

Strange & J. R. Strange, Judaism in Late Antiquity III/4, Leiden 2001, 45–73

J. Yellin et al., BASOR 321

(2001), 65–78

R. Bar-Nathan, Hasmonean and Herodian Palaces at Jericho: Final Reports of the 1973–

1987 Excavations (director E. Netzer), III: The Pottery, Jerusalem 2002, 203–204

Y. Baruch et al., ‘Atiqot

41/2 (2002), 177–183

I. Carmi, Radiocarbon 44 (2002), 213–216

T. Elgvin & S. J. Pfann, Dead Sea Discoveries 9 (2002), 20–33

D. Herman, BAR 28/6 (2002), 8–10

S. Laurant & E. Villeneuve, MdB 143

(2002), 54–55

A. Lemaire, Internationales Josephus-Kolloquium, Paris 2001 (eds. F. Siegert & J. U.

Kalms), Münster 2002, 138–151

F. Mebarki & É. Puech, Les manuscripts de la Mer Morte (op. cit.), Rodez

2002, 159–175

J. VanderKam & P. Flint, The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Significance for

Understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity, San Francisco 2002, 3–53

J. Ben-Dov, Journal

of Jewish Studies 54 (2003), 125–138

D. Dlugosz, MdB 151 (2003), 47

id., Revue de Qumran 22 (2005),

121–131

M. E. Kislev & M. Marmorstein, IEJ 53 (2003), 74–77

G. Bijovsky, ibid. 54 (2004), 75–76

G.

M. Hollenback, Dead Sea Discoveries 11 (2004), 289–292

J. A. Kelhoffer, ibid., 293–314

Y. Peleg & I.

Magen, Artifax 19/4 (2004), 7

L. I. Levine, The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years, 2nd ed.,

New Haven, CT 2005, 63–66

A. Lewin, The Archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine, Los Angeles, CA

2005, 120–125

M. McCormack, ibid. 20/3 (2005), 1, 24–25

E. Netzer, IEJ 55 (2005), 97–100

M. Samet,

BAR 31/2 (2005), 26–27

Jericho und Qumran: Neues zum Umfeld der Bibel (Eichstätter Studien, N.F. 45

ed.

B. Mayer), Regensburg 2000

ibid. (Review) BASOR 329 (2003), 94–96

R. Donceel, The Khirbet Qumran

Cemeteries: A Synthesis of the Archaeological Data (The Qumran Chronicle 10), Cracow 2002

J. B. Humbert. & J. Gunneweg et al., Khirbet Qumrân et ‘Aïn Feshkha, 2: Études d’anthropologie, de physique et de

chimie—Studies of Anthropology, Physics and Chemistry (Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series

Archaeologica 3), Fribourg 2003

H. Eshel (& Z. Greenhut), RB 100 (1993), 252–259

id. (et al.), Dead Sea Discoveries 9 (2002),

135–165

R. Hachlili, Revue de Qumran 16/62 (1993), 247–264

id., The Dead Sea Scrolls Fifty Years after

Their Discovery (op. cit.), Jerusalem 2000, 661–672

Z. J. Kapera, Methods of Investigations of the Dead Sea

Scrolls (op. cit.), New York 1994, 97–110

id., The Qumran Chronicle 5 (1995), 123–132

9 (2000), 139–152;

E. -M. Laperrousaz, Revue des Etudes Juives 154 (1995), 227–238

É. Puech, BASOR 312 (1998), 21–36;

J. K. Zangenberg, The Qumran Chronicle 8 (1998), 213–218

9 (2000), 51–76

id., ASOR Annual Meeting

Abstract Book, Boulder, CO 2001, 25

B. Zissu, Dead Sea Discoveries 5 (1998), 158–171

O. Röhrer-Ertl

et al., Revue de Qumran 19/73 (1999), 3–46

J. E. Taylor, Dead Sea Discoveries 6 (1999), 285–323

J.

Zias, Dead Sea Discoveries 7 (2000), 220–253

id., MdB 151 (2003), 48–50

id., Revue de Qumran 21/81

(2003), 83–98

S. Guise Sheridan, ASOR Annual Meeting Abstract Book, Boulder, CO 2001, 42

id., ASOR

Newsletter 51/3 (2001), 5–6

id., Dead Sea Discoveries 9 (2002), 199–248

id. (et al.), Khirbet Qumrân et

‘Aïn Feshkha, 2: Études d’anthropologie, de physique et de chimie—Studies of Anthropology, Physics and

Chemistry (Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 3

by J. -B. Humbert & J. Gunneweg et al.), Fribourg 2003, 129–169

M. Broshi & H. Eshel, BAR 29/1 (2003), 26–33, 71

id., Revue de

Qumran 21/83 (2004), 487–489

id., JRA 17 (2004), 321–332

C. Clamer, Khirbet Qumrân et ‘Aïn Feshkha,

2 (op. cit.), Fribourg 2003, 171–183

The Excavations of Khirbet Qumran and Ain Feshkha: Synthesis of

Roland de Vaux’s Field Notes (Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus, Series Archaeologica 1/B

eds. J.

-B. Humbert & A. Chambon

tr. & rev. S. J. Pfann), Fribourg 2003, 73–79

R. A. Freund, BAR 29/2 (2003),

62–63

J. Norton, Khirbet Qumrân et ‘Aïn Feshkha, 2 (op. cit.), Fribourg 2003, 107–127

K. L. Rasmussen

et al., ibid., 185–189

A. Baumgarten, Dead Sea Discoveries 11 (2004), 174–190

G. L. Doudna, Journal of

the Hebrew Scriptures 5 (2004), 1–46

S. Katz, Artifax 19/4 (2004), 9

R. Kugler & E. Chazon, Dead Sea

Discoveries 11 (2004), 167–173

J. Ciecielag, Mogilany 5 (1995–1998), 105–115

R. D. Leonard, Jr., The Qumran Chronicle 7 (1997), 105–

108, 225–234.

P. Hidiroglou, NEA 63 (2000), 138–139

id., Revue des Études Juives 159 (2000), 19–47

Z. Ilan, Wasser im

Heiligen Land: Biblische Zeugnisse und archäologische Forschungen (Schriftenreihe der Frontinus-Gesellschaft Suppl. 3

eds. W. Dierx & G. Garbrecht), Mainz am Rhein 2001, 159–164

id. (& D. Amit), The

Aqueducts of Israel, Portsmouth, RI 2002, 381–386

K. Galor, Cura Aquarum in Israel, Siegburg 2002,

33–45

- Cracked Steps at Qumran -

photo by Jefferson Williams

Cracked Steps at Qumran

Cracked Steps at Qumran

photo by Jefferson Williams - Plate XVI - Cracked Steps at Qumran

from de Vaux (1973b)

Plate XVI

Plate XVI

Cistern 48-49, split by the earthquake. Towards the south-west.

de Vaux (1973b) - Fig. 39 - Cracked Steps at Qumran