Petra - Qasr Bint

Qasr Bint

Qasr BintDennis Jarvis - Wikipedia - CC BY-SA 3.0

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Qasr al Bint | Arabic | قاسر ال بينت |

| Qasr al-Bint Fir’aun | Arabic | فرعون قاسر ال بينت |

- from Chat GPT 5.2, 13 January 2026

- sources: Wikipedia

Architecturally, the temple is characterized by a high podium, ashlar masonry of exceptional quality, and a tripartite cella preceded by a pronaos with columns. Its construction combines Nabataean building traditions with Hellenistic and Roman architectural forms, reflecting Petra’s role as a cosmopolitan capital during the early Roman Near East.

Qasr al-Bint preserves wooden beams embedded within selected wall courses, a construction feature that may reflect an ancient attempt to improve structural performance during earthquakes.

- from Petra - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 0.1 - Photo of Qasr Bint

from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 0.1

Fig. 0.1

Photo of the sanctuary

Augé et al. (2016) - Qasr Bint in Google Earth

- Map of Qasr al-Bint

and environs from Tholbecq et. al. (2021)

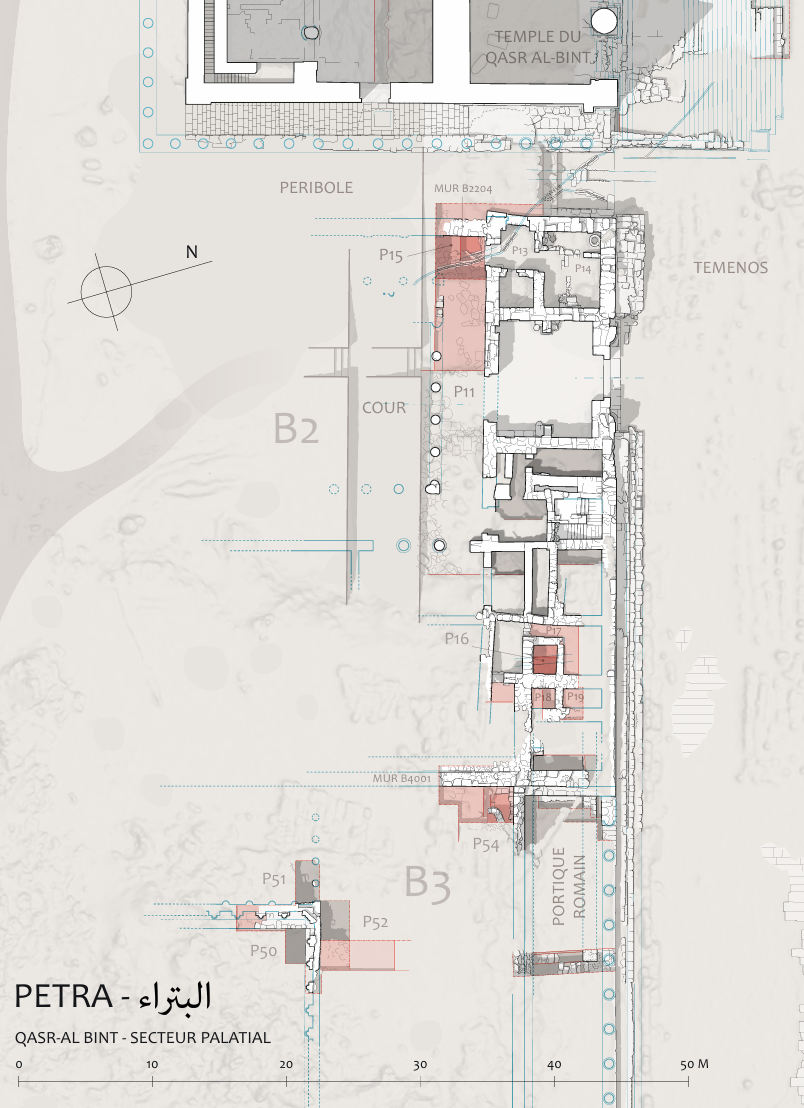

Qasr al-Bint in the Roman period. General plan and location of surveys

Qasr al-Bint in the Roman period. General plan and location of surveys

(MAFP/M. Belarbi/Th. Fournet)

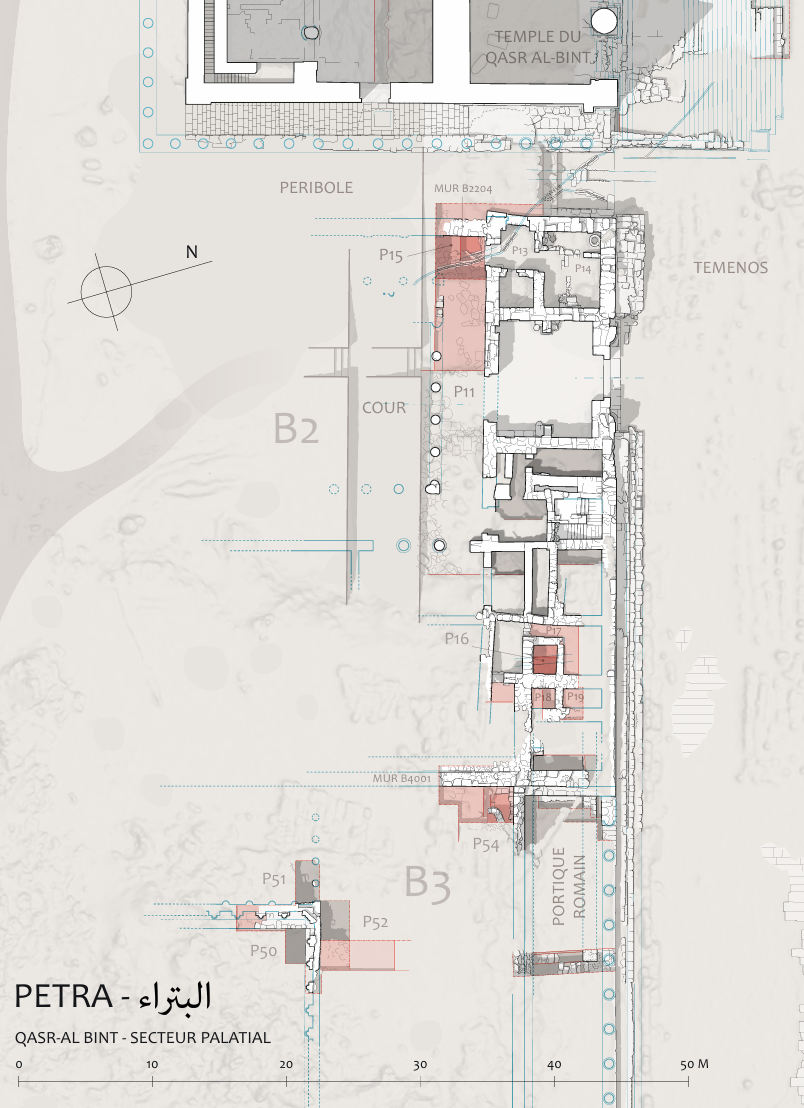

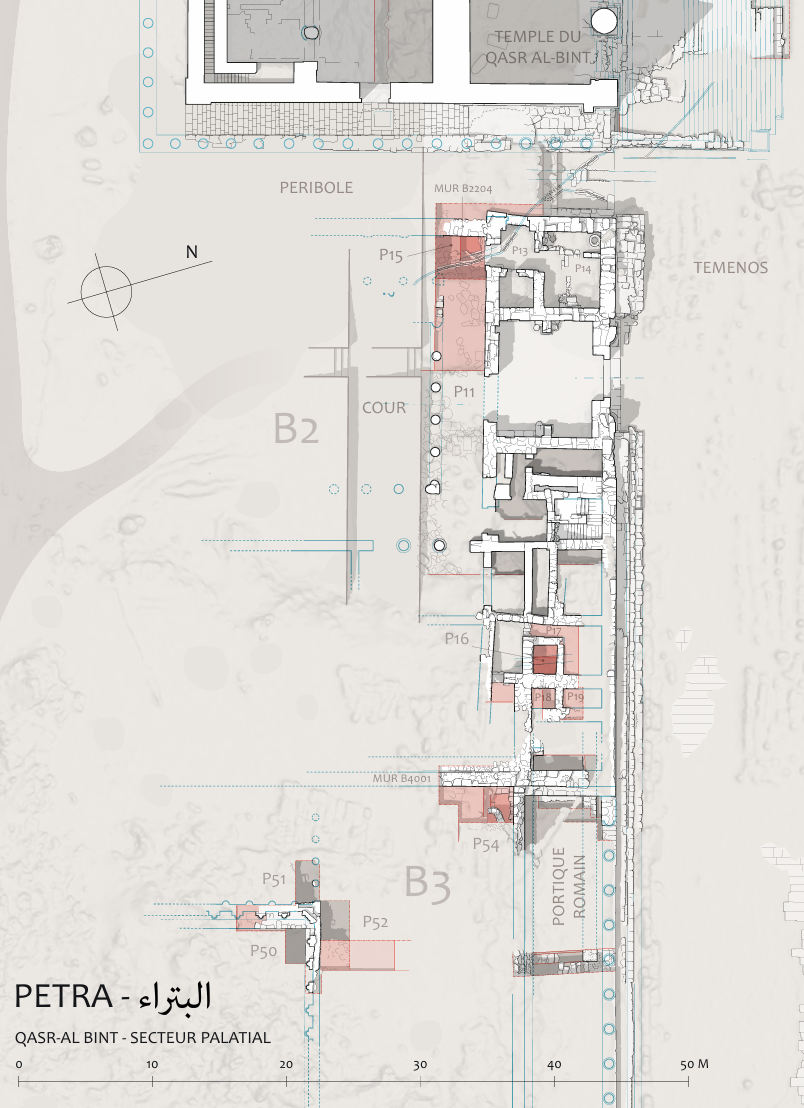

Tholbecq et. al. (2021) - Fig. 1 - Plan of sectors

excavated in 2017 from Tholbecq et. al. (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

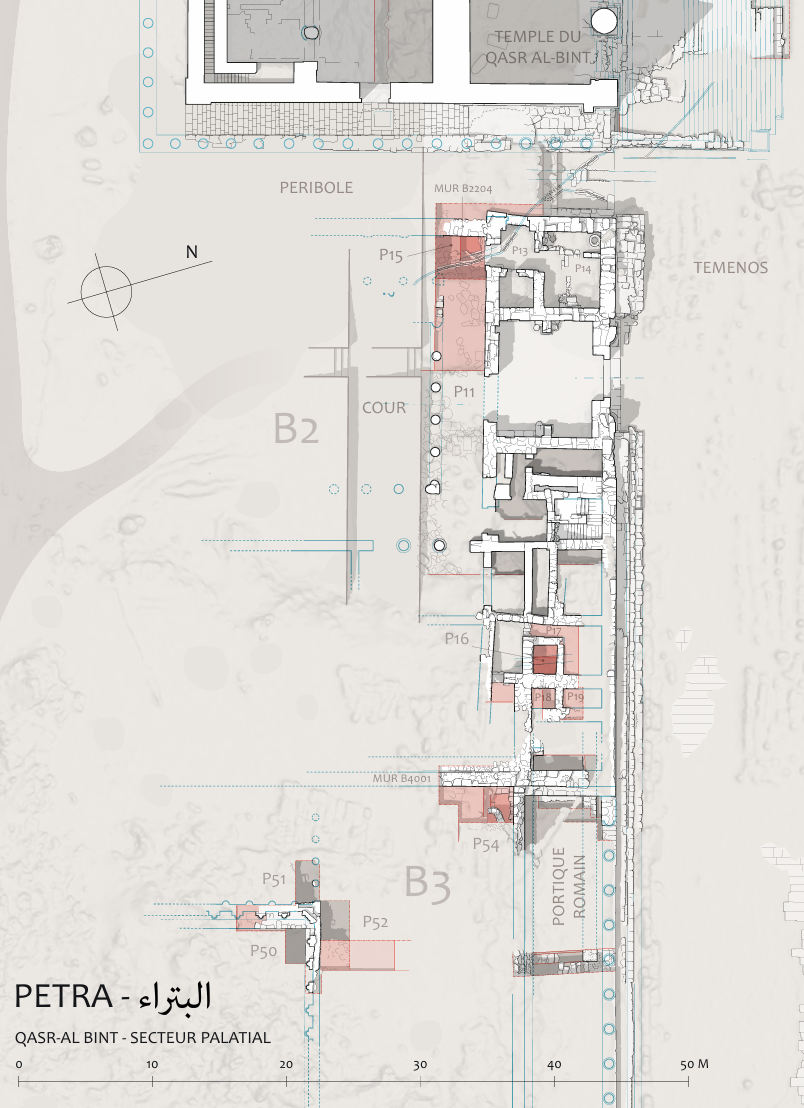

Plan of sectors excavated during the fall 2017 campaign

(Drawing T. Fournet, ©MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2018) - Fig. 1 - Plan of sectors

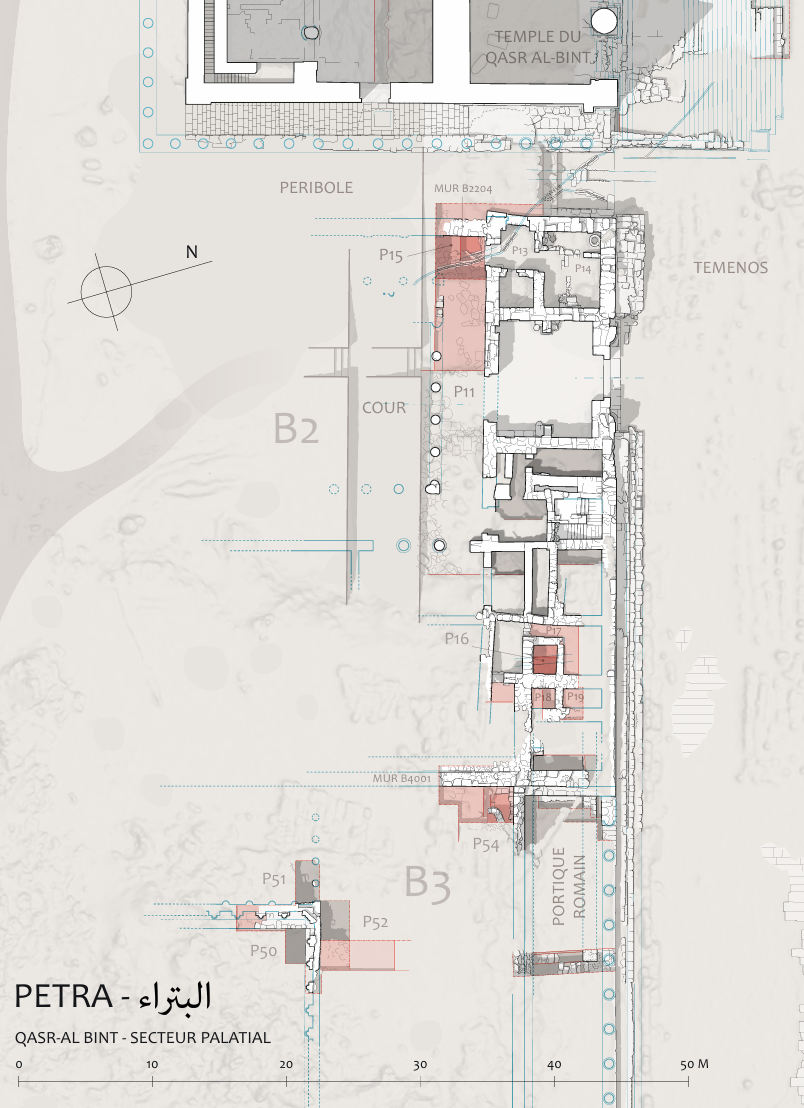

excavated in 2018 from Tholbecq et. al. (2019)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

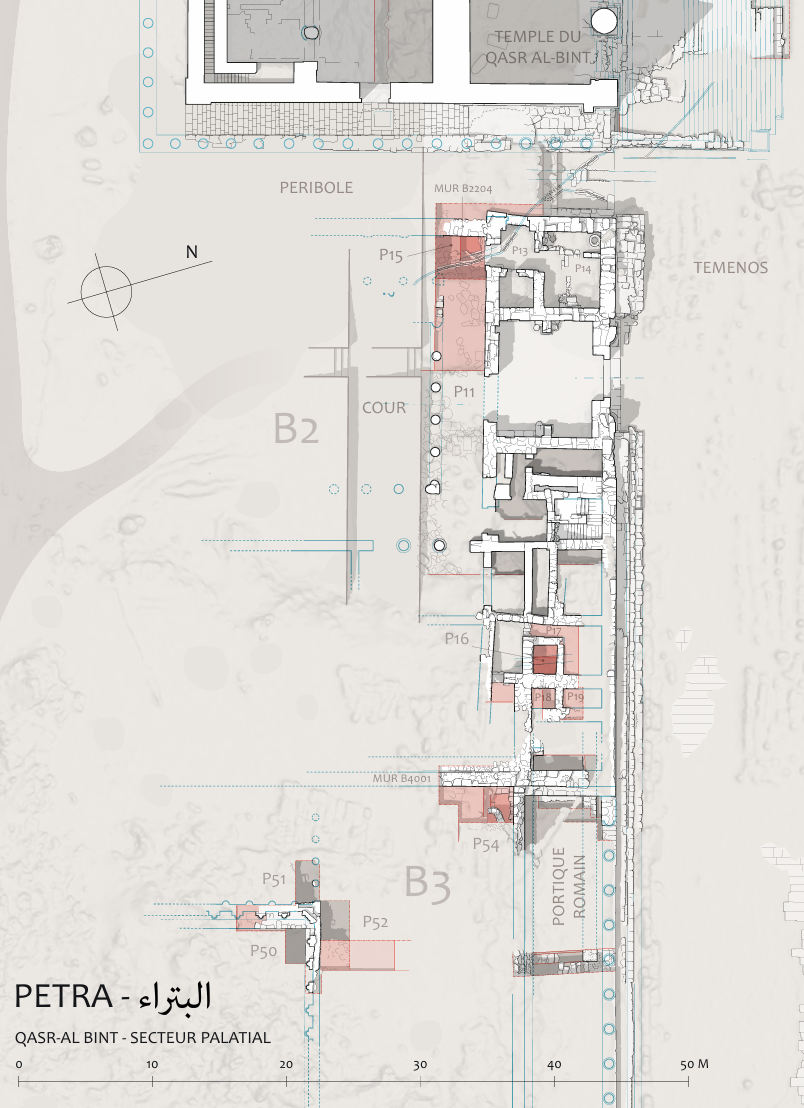

Plan of sectors excavated during the fall 2018 campaign

(Drawing T. Fournet, ©MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2019) - Fig. 1 - Plan of sectors

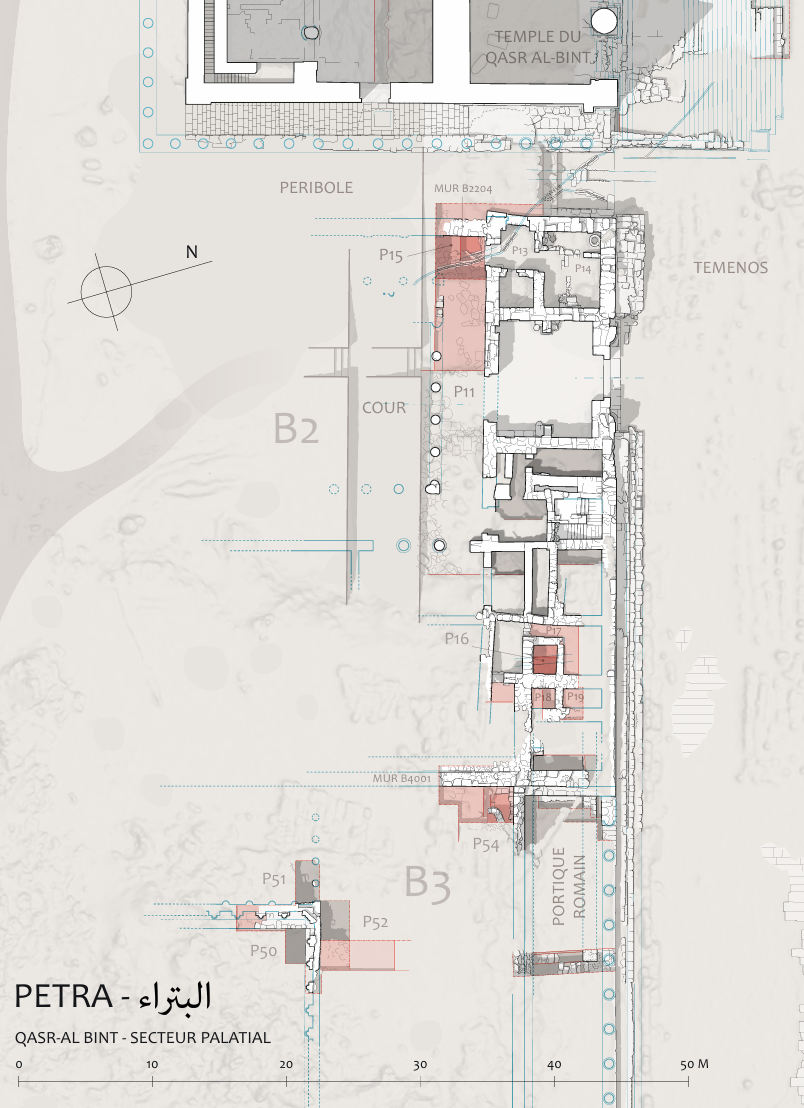

excavated in 2023 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

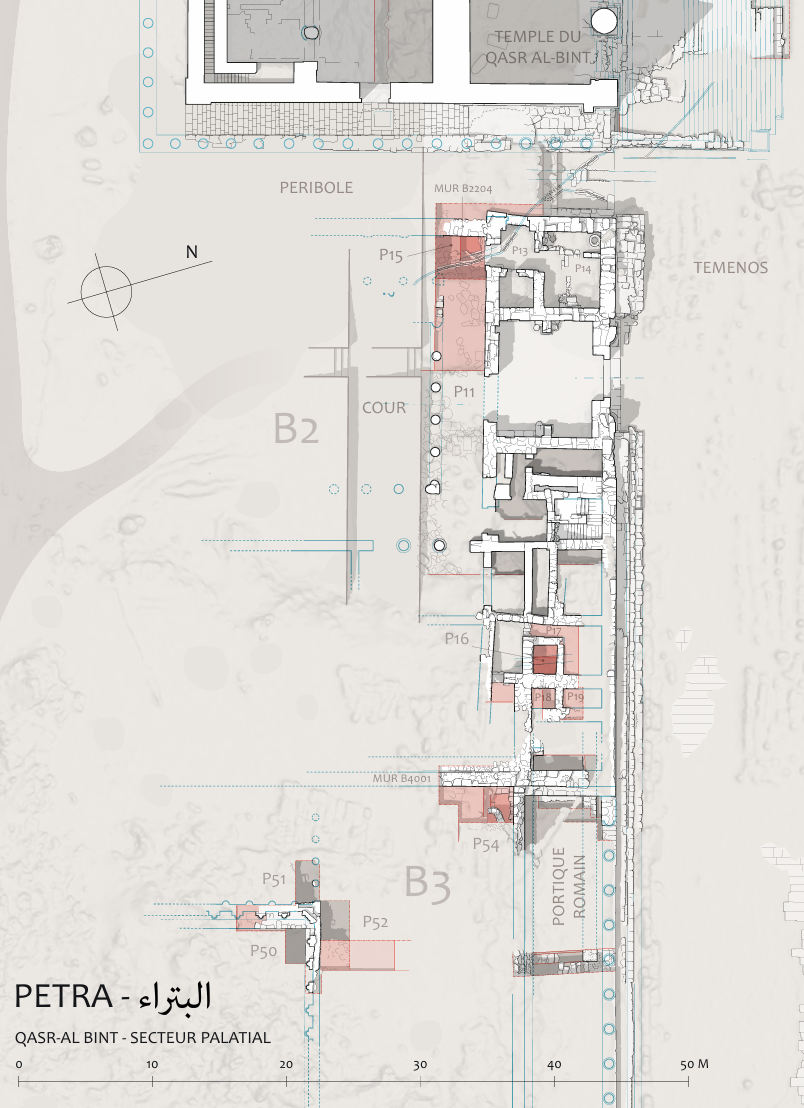

Petra, general plan of the Qasr al-Bint sector, location of operations carried out in 2023

(T. Fournet/ M. Belarbi, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Plan of Qasr al-Bint

from Fournet and Renel (2019)

Plan of Qasr al-Bint

Plan of Qasr al-Bint

Fournet and Renel (2019)

- Map of Qasr al-Bint

and environs from Tholbecq et. al. (2021)

Qasr al-Bint in the Roman period. General plan and location of surveys

Qasr al-Bint in the Roman period. General plan and location of surveys

(MAFP/M. Belarbi/Th. Fournet)

Tholbecq et. al. (2021) - Fig. 1 - Plan of sectors

excavated in 2017 from Tholbecq et. al. (2018)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of sectors excavated during the fall 2017 campaign

(Drawing T. Fournet, ©MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2018) - Fig. 1 - Plan of sectors

excavated in 2018 from Tholbecq et. al. (2019)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Plan of sectors excavated during the fall 2018 campaign

(Drawing T. Fournet, ©MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2019) - Fig. 1 - Plan of sectors

excavated in 2023 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Petra, general plan of the Qasr al-Bint sector, location of operations carried out in 2023

(T. Fournet/ M. Belarbi, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Plan of Qasr al-Bint

from Fournet and Renel (2019)

Plan of Qasr al-Bint

Plan of Qasr al-Bint

Fournet and Renel (2019)

- Fig. 3.2 - Plan of staircase

from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 3.2

Fig. 3.2

Qasr al-Bint: plan of the assembled surveys of the gutters and the staircase (scale: 1/150)

(© MAFP, CAD: C. March)

Augé et al. (2016) - Elevation of western

monumental stairway from Fournet and Renel (2019)

Elevation of western monumental stairway

Elevation of western monumental stairway

MAFP 2018, TF/MB

Fournet and Renel (2019) - Reconstruction of stairway

from Fournet and Renel (2019)

Reconstruction of stairway

Reconstruction of stairway

Fournet and Renel (2019) - Fig. 0.3 - Plan of the

western zone from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 0.3

Fig. 0.3

General plan of the western zone

(© MAFP, CAD: C. March)

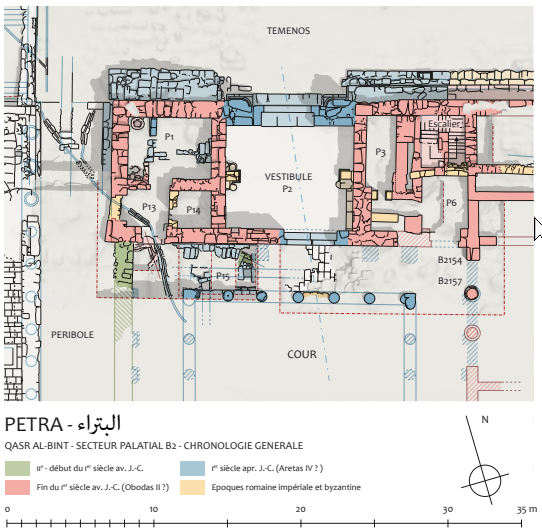

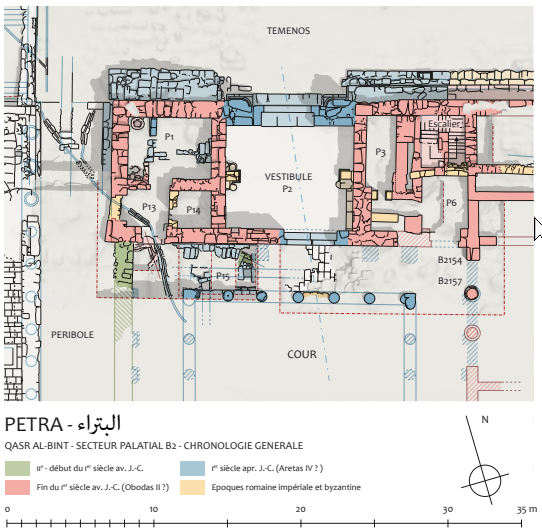

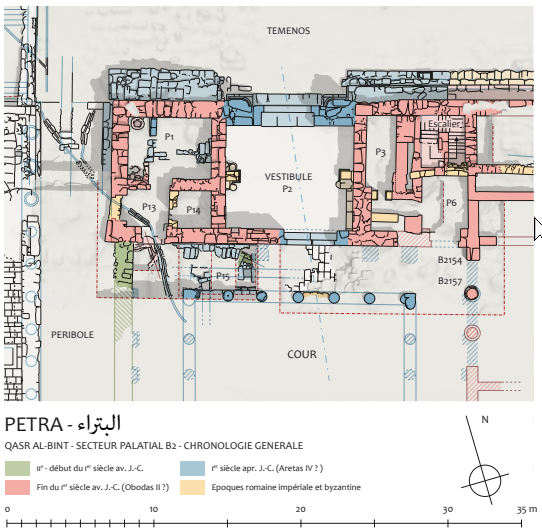

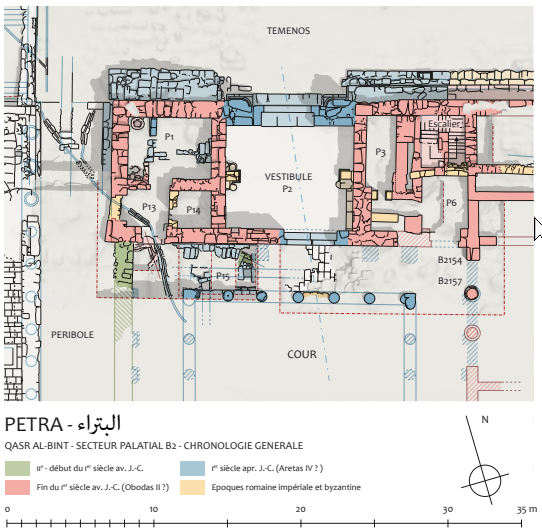

Augé et al. (2016) - Fig. 16 - Plan of the palace

sector of Qasr Bint from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

General plan of the palace sector of Qasr al-Bint sector, location of operations carried out in Fall 2023

(T. Fournet/M. Belarbi/ P. Piraud-Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Simplified plan of "B" building

from Fournet and Renel (2019)

Simplified plan of "B" building

Simplified plan of "B" building

MAFP, 2017

Fournet and Renel (2019) - Fig. 6.38 - General plan

of western part of the Qasr el-Bint Temenos from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.38

Fig. 6.38

General plan of western part of the Qasr el-Bint Temenos

(Zayadine et al. 2003: 8)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.40a - Detailed plan

from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.40a

Fig. 6.40a

Detailed plan

(Larché and Zayadine 2003: Fig.221)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.52b - East-West

section of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.52b

Fig. 6.52b

East-West section of reconstructed roof of Qasr el-Bint as Larché and Zayadine suggested in final report

(Larche in Zayadine et al. 2003: Fig. 15)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 4.3 - Plan of the great altar

from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 4.3

Fig. 4.3

The great altar: plans from the assembled surveys of P. Parr's surveys and sections (scale: 1/100)

(© MAFP, CAD: C. March)

Augé et al. (2016) - Fig. 4.4 - Face of the great altar

from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 4.4

Fig. 4.4

The great altar: east, west and north faces of the assembled statements (scale: 1/100)

(© MAFP, CAD: C. March)

Augé et al. (2016) - Fig. 4 - scree of the

apse monument from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Overall plan of the scree of the apse monument at the end of the October 2022 campaign, superposition of all the layers of blocks in the falling position. In blue the elements of marble statuary, in green the blocks from the temple of Qasr al-Bint

(T. Fournet / C. March / M. Belarbi, MAFP)

Tholbecq et al. (2022)

- Fig. 3.2 - Plan of staircase

from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 3.2

Fig. 3.2

Qasr al-Bint: plan of the assembled surveys of the gutters and the staircase (scale: 1/150)

(© MAFP, CAD: C. March)

Augé et al. (2016) - Elevation of western

monumental stairway from Fournet and Renel (2019)

Elevation of western monumental stairway

Elevation of western monumental stairway

MAFP 2018, TF/MB

Fournet and Renel (2019) - Reconstruction of stairway

from Fournet and Renel (2019)

Reconstruction of stairway

Reconstruction of stairway

Fournet and Renel (2019) - Fig. 16 - Plan of the palace

sector of Qasr Bint from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

General plan of the palace sector of Qasr al-Bint sector, location of operations carried out in Fall 2023

(T. Fournet/M. Belarbi/ P. Piraud-Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 0.3 - Plan of the

western zone from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 0.3

Fig. 0.3

General plan of the western zone

(© MAFP, CAD: C. March)

Augé et al. (2016) - Simplified plan of "B" building

from Fournet and Renel (2019)

Simplified plan of "B" building

Simplified plan of "B" building

MAFP, 2017

Fournet and Renel (2019) - Fig. 6.38 - General plan

of western part of the Qasr el-Bint Temenos from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.38

Fig. 6.38

General plan of western part of the Qasr el-Bint Temenos

(Zayadine et al. 2003: 8)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.40a - Detailed plan

from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.40a

Fig. 6.40a

Detailed plan

(Larché and Zayadine 2003: Fig.221)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.52b - East-West

section of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.52b

Fig. 6.52b

East-West section of reconstructed roof of Qasr el-Bint as Larché and Zayadine suggested in final report

(Larche in Zayadine et al. 2003: Fig. 15)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 4.3 - Plan of the great altar

from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 4.3

Fig. 4.3

The great altar: plans from the assembled surveys of P. Parr's surveys and sections (scale: 1/100)

(© MAFP, CAD: C. March)

Augé et al. (2016) - Fig. 4.4 - Face of the great altar

from Augé et al. (2016)

Fig. 4.4

Fig. 4.4

The great altar: east, west and north faces of the assembled statements (scale: 1/100)

(© MAFP, CAD: C. March)

Augé et al. (2016) - Fig. 4 - scree of the

apse monument from Tholbecq et al. (2022)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Overall plan of the scree of the apse monument at the end of the October 2022 campaign, superposition of all the layers of blocks in the falling position. In blue the elements of marble statuary, in green the blocks from the temple of Qasr al-Bint

(T. Fournet / C. March / M. Belarbi, MAFP)

Tholbecq et al. (2022)

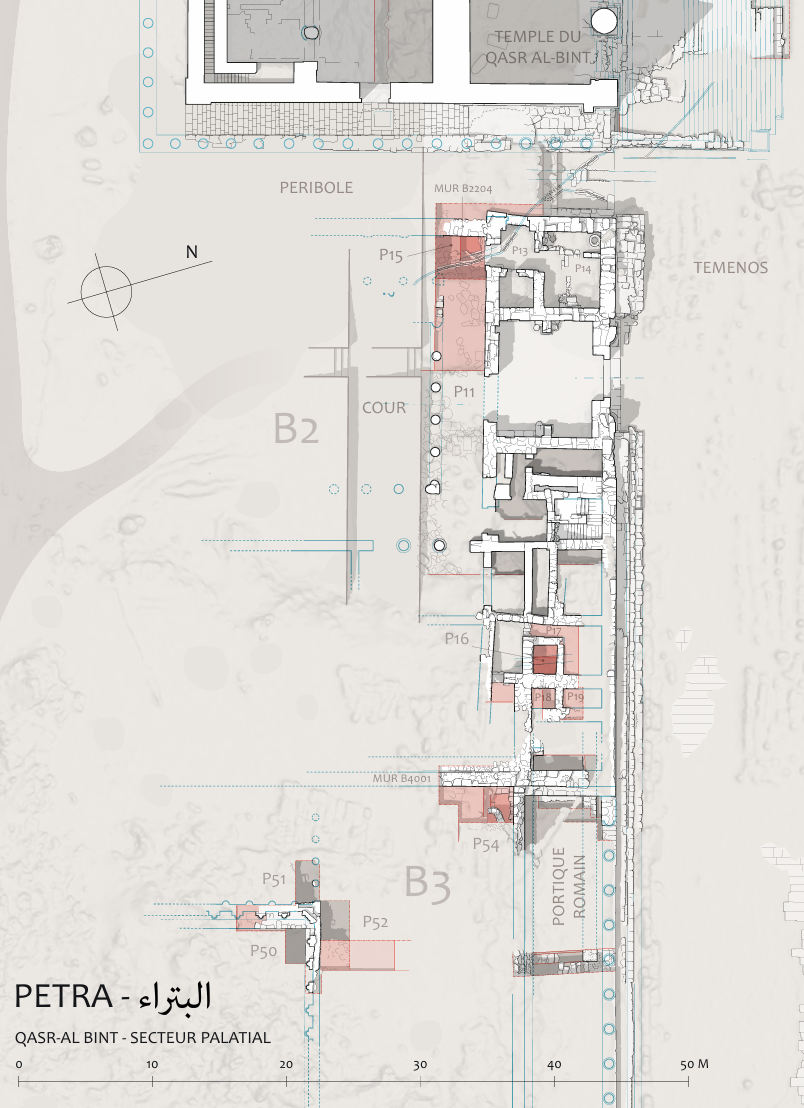

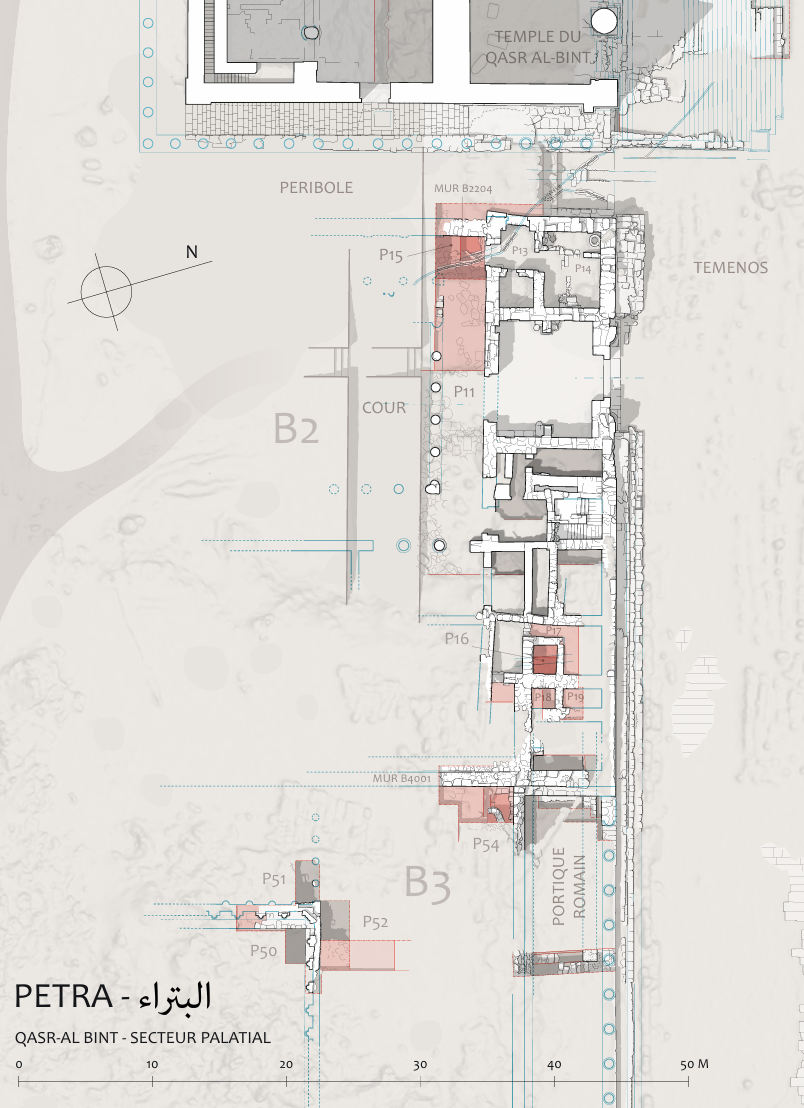

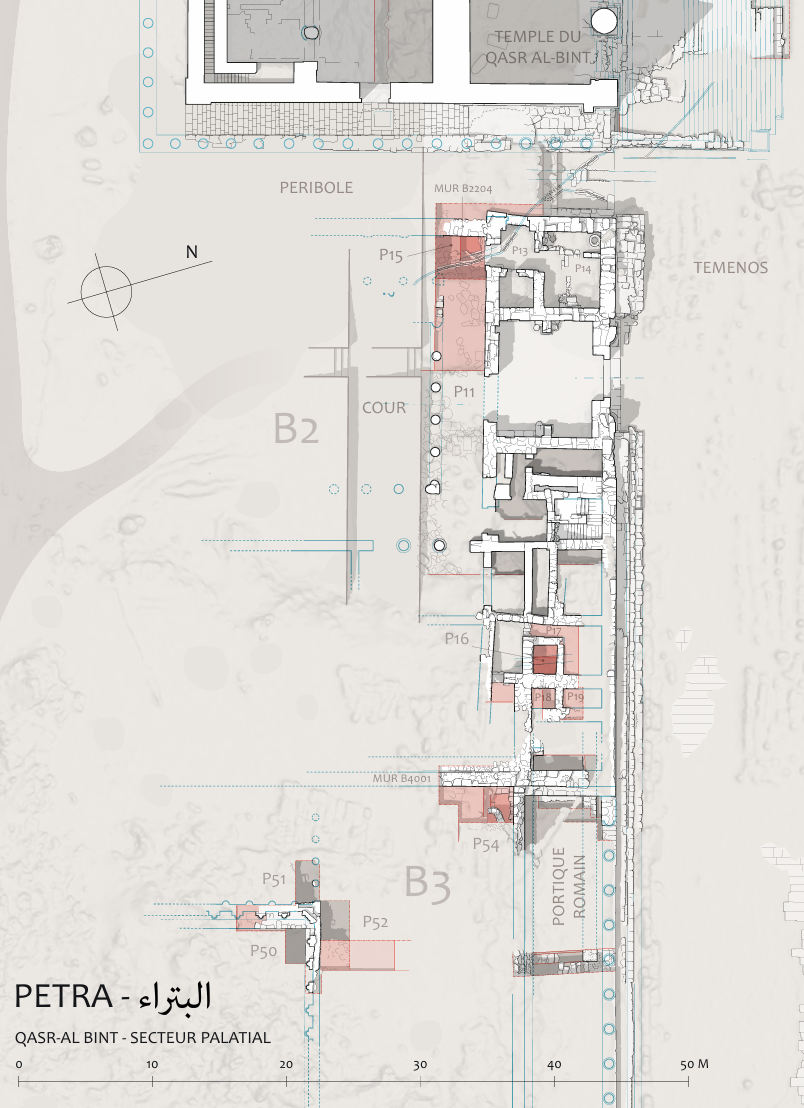

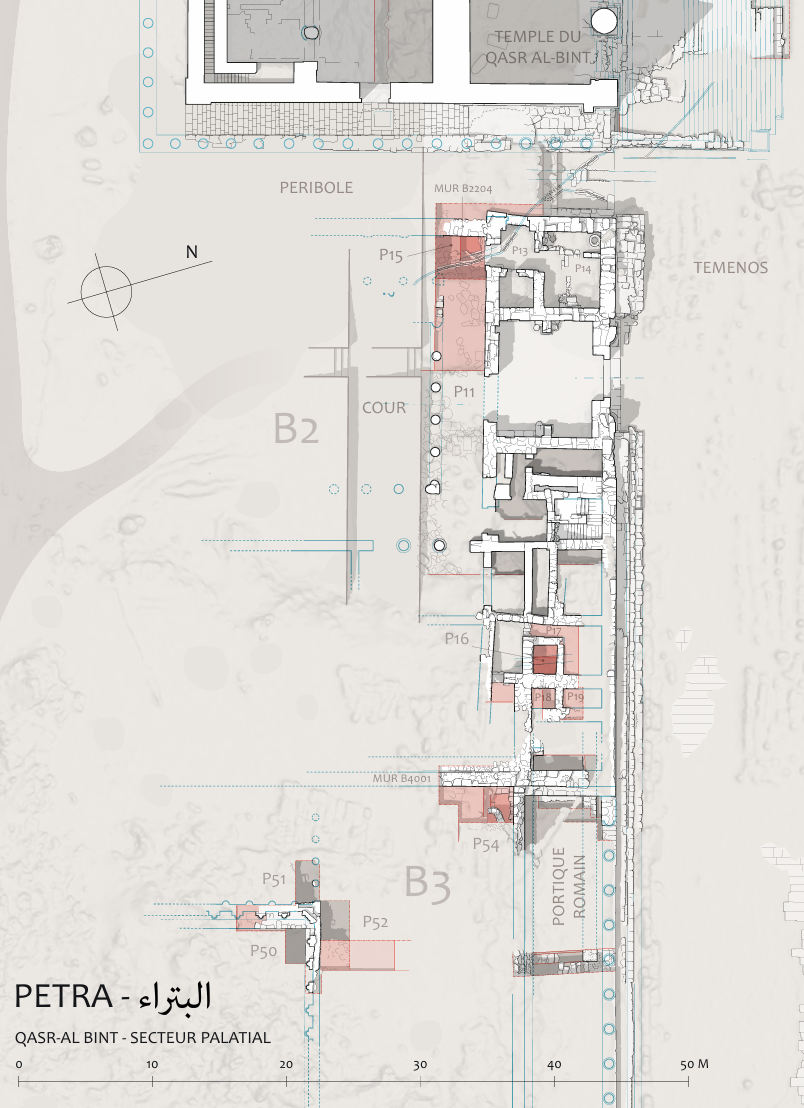

- Fig. 1 - Areas B2 and

B3 from Tholbecq et al. (2024)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the areas examined in the 2024 spring campaign

(T. Fournet / M. Belarbi/ P. Piraud-Fournet, MAFP)

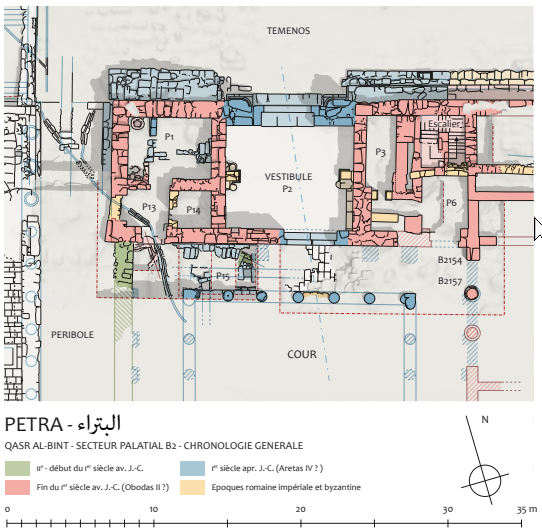

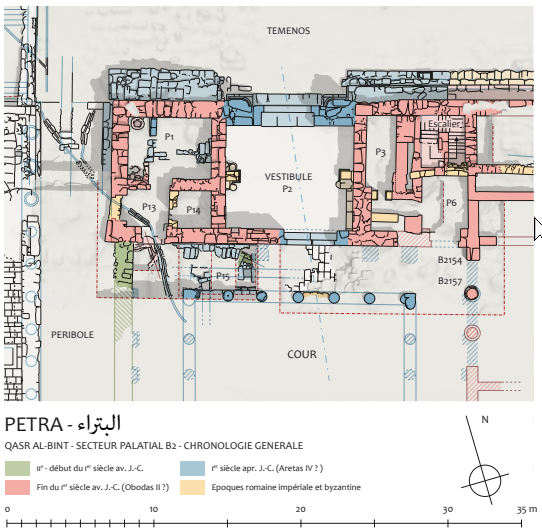

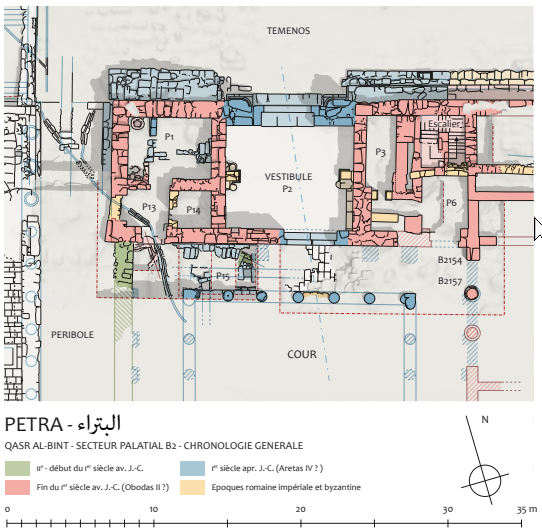

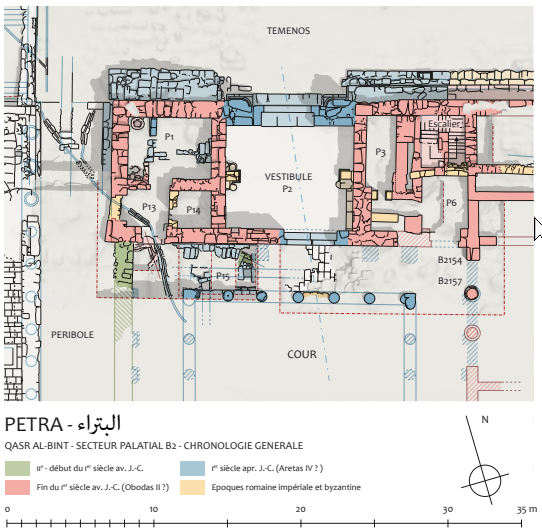

Tholbecq et al. (2024) - Fig. 24 - Phases of

Area B2 from Tholbecq et al. (2024)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

Plan of part of the NE sector (B2) with proposed phasing

(Th. Fournet / M. Belarbi/ P. Piraud-Fournet, MAFP 2024)

Tholbecq et al. (2024)

- Fig. 1 - Areas B2 and

B3 from Tholbecq et al. (2024)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Map of the areas examined in the 2024 spring campaign

(T. Fournet / M. Belarbi/ P. Piraud-Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et al. (2024) - Fig. 24 - Phases of

Area B2 from Tholbecq et al. (2024)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

Plan of part of the NE sector (B2) with proposed phasing

(Th. Fournet / M. Belarbi/ P. Piraud-Fournet, MAFP 2024)

Tholbecq et al. (2024)

- Cover Page - Qasr al-Bint sector

in the Roman era from Tholbecq et. al. (2017)

Cover page

Cover page

The Qasr al-Bint sector in the Roman era

(Thibaud Fournet, 2017)

Tholbecq et. al. (2017) - Fig. 6.52a - Axonometric drawing

of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.52a

Fig. 6.52a

Axonometric drawing of reconstructed roof of Qasr el-Bint as Larché and Zayadine suggested in final report

(Larche in Zayadine et al. 2003: Fig. 220)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.53a - Cutaway Axonometric

drawing of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.53a

Fig. 6.53a

Axonometric reconstruction suggested here

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.41d - Isometric of southeast

corner showing the cavity walls and stairs from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.41d

Fig. 6.41d

Isometric of southeast angle showing the cavity walls including the stairs

(Wright 1961a: Fig. 5)

Rababeh (2005)

- Fig. 10 - Section of western

peribole from Tholbecq et. al. (2019)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

East-west section of the western peribole.

(M. Bélarbi, C. Besnier, F. Renel)

Tholbecq et. al. (2019) - Fig. 3 - E-W section

of the fill of the western peribole with an earthquake destruction layer from Renel (2013)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

East-west section of the fill of the western peribole of the Qasr al-Bint temple.

(© M. Belarbi, MF-PQB)

Renel (2013) - Fig. 9 - Reconstruction of

southern half of the main facade of the apse monument from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Proposal for the restitution in principle of the southern half of the main facade of the apse monument, simplified working hypothesis

(T. Fournet, MAFP).

Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

- Fig. 5.30b - Torsion response

through as-symmetrical building from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 5.30b

Fig. 5.30b

The torsion response through as-symmetrical building

(Arnold 1989: Fig.5.17)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 5.30c - Torsion response

of Qasr el-Bint as symmetrical building from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 5.30c

Fig. 5.30c

The torsion response in the Qasr el-Bint as symmetrical building.

Rababeh (2005)

- Fig. 11 - Stratigraphy at the base

of the western péribole (περίβόλος) from Tholbecq et al (2019:36-37)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Stratigraphy at the base of the western péribole (περίβόλος) of the Temple

Tholbecq et al (2019) - © MAFP - Fig. 12 - View of the Stratum F1082

from Tholbecq et al (2019:36-37)

Figure 12

Figure 12

View of the Stratum F1082

Tholbecq et al (2019) - © MAFP - Fig. 4 - Blocks from collapse

of the apse from Renel (2013)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

View of the pile of blocks linked to the fall of the elevations of the apse monument during the earthquake of 363.

(© L. Borel, MFPQB)

Renel (2013) - Fig. 3 - Destruction layers

of the western peribole from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The western peribole of Qasr al-Bint, towards the south, destruction layers

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Destruction layers of the western

peribole - photo by JW

- Destruction layers of the western

peribole - photo by JW

- Monumental Staircase of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Side and Rear panorama of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Side panorama of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Side photo of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Rear photo of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Front photo of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Fig. 10 - Overview of

destruction layer from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Overview of the ancient destruction level

(F. Renel, MAFP).

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 18 - Upper stratigraphic

sequence of P15 in the palace sector from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

view of the upper stratigraphic sequence of space P15, southern section

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 19 - Fallen blocks

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

the level of fallen blocks B2165-2173, towards the northeast

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 24 - Fallen capitals

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

detail of the elements of Corinthian capitals in fallen position in destruction layer B2165-2173

(T. Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 40 - Fallen blocks

in room P16 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 40

Fig. 40

fallen blocks (B2171) present in the upper filling of room P16

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 41 - Fallen architecture

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 41

Fig. 41

detail of a stucco preserved on its facing block (B2171)

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

- Fig. 11 - Stratigraphy at the base

of the western péribole (περίβόλος) from Tholbecq et al (2019:36-37)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Stratigraphy at the base of the western péribole (περίβόλος) of the Temple

Tholbecq et al (2019) - © MAFP - Fig. 12 - View of the Stratum F1082

from Tholbecq et al (2019:36-37)

Figure 12

Figure 12

View of the Stratum F1082

Tholbecq et al (2019) - © MAFP - Fig. 4 - Blocks from collapse

of the apse from Renel (2013)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

View of the pile of blocks linked to the fall of the elevations of the apse monument during the earthquake of 363.

(© L. Borel, MFPQB)

Renel (2013) - Fig. 3 - Destruction layers

of the western peribole from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The western peribole of Qasr al-Bint, towards the south, destruction layers

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Destruction layers of the western

peribole - photo by JW

- Destruction layers of the western

peribole - photo by JW

- Monumental Staircase of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Side and Rear panorama of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Side panorama of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Side photo of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Rear photo of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Front photo of Qasr Bint - photo by JW

- Fig. 10 - Overview of

destruction layer from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Overview of the ancient destruction level

(F. Renel, MAFP).

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 18 - Upper stratigraphic

sequence of P15 in the palace sector from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

view of the upper stratigraphic sequence of space P15, southern section

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 19 - Fallen blocks

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

the level of fallen blocks B2165-2173, towards the northeast

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 24 - Fallen capitals

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

detail of the elements of Corinthian capitals in fallen position in destruction layer B2165-2173

(T. Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 40 - Fallen blocks

in room P16 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 40

Fig. 40

fallen blocks (B2171) present in the upper filling of room P16

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 41 - Fallen architecture

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 41

Fig. 41

detail of a stucco preserved on its facing block (B2171)

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

- from Augé et al. (2016)

- proposed for the

entire central sector of Petra

| Phase | Dates | Label | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Occupation before Hellenistic occupation of the site ? |

Description

Wadi Musa turns towards the north at the foot of the cliffs which delimit the basin where the future city of Petra would be built. Then it returns to an east-west direction (Wadi Siyyagh). This bend forms a deep and wide hollow towards which several passable paths converge. The slopes of the southern hill, against the Al-Habis cliff, offer locations sheltered from westerly winds and protected from floods84. In this sector, the thickness of the sediments and the embankments and human constructions have profoundly modified the relief. A few sporadic finds in deep levels, in contact with the ancient bed of the wadi - cut flints, fragments of Iron Age ceramics - could constitute indications of human presence, but their low number does not make it possible to determine its duration or nature. The first proven traces of occupation in this sector date back to the Hellenistic era.

Footnotes

84. Mouton, Renel & Kropp 2008 ; Renel, Mouton, Augé et al. 2012. |

|

| 1 | 4th-3rd c. BCE | Terraced developments |

Description

Deep borings carried out to the east and west of the imperial apse monument (sectors C9 and C4) revealed a surficial layer of reddish aeolian sand in several locations - vestiges of terraced developments made with stone blocks bound with clay. To this phase belong traces of tent stakes, a silo (FR C4250), and a hearth associated with remains of circulation levels materialized by thin layers of packed earth mixed with ashes (FR C4030). These developments, hitherto recognized in isolation, cannot be attributed to a specific occupation. No trace of wadi flooding was detected within these levels, confirming the existence of a middle terrace at this location. |

| 2 | end 2nd-mid-3rd c. BCE | Oblique constructions |

Description

Identified over 30 m long under the temenos and to the west of the imperial monument, these buildings are distinguished by their distinct difference from the religious complex of the following phase. Their walls, leveled during this phase, are preserved in one or two courses with the associated floors. They rest on deep foundations, made of uncut blocks and pebbles bound with clay. The small surface area of the surveys does not make it possible to restore an overall plan of these constructions or to determine their function. Domestic use seems most likely, but it is still difficult to specify the mode of establishment of the dwellings: juxtaposition of small separate units around a central space or gradual formation of a large house by successive extensions and partitions. Three architectural phases have been recognized there85. The associated material and the available radiocarbon dates make it possible to anchor the chronology86. These first constructions should be compared with the discoveries made by the “Hellenistic Petra Project”87 and those of Al-Katuteh.

Footnotes

85. Mouton, Renel & Kropp 2008 |

| 3 | mid-1st c. BCE | Construction of the large Nabataean residence (Building C, zone C4) |

Description

3a — Remains of a first construction along a N-S axis in the classic Nabataean style.

All of the “oblique constructions” are leveled, apparently in a planned manner88.

It is assumed that religious installations already existed at the location of the

large altar, the small altar, and perhaps Qasr al-Bint itself89. The first state of

the eastern complex (Building B) could also relate to this phase (between approx. 50 BCE and approx. 10 BCE).

Footnotes

88. Mouton, Renel & Kropp 2008 |

| 4 | mid-1st c. BCE - early 2nd c. CE | Planning of a large sanctuary and transformation of its surroundings |

Description

4a — A major program implemented for the creation of a monumental sanctuary with a

general north-south orientation was established following a metrological grid in

large Egyptian cubits of 0.525 m; it led to the definitive razing of the Hellenistic

remains. It includes the construction of the temple known as “Qasr al-Bint”90,

as well as changes to its surroundings, including its western limit marked by a

north-south wall which truncates the facade of the Nabataean residence (Building C)

inducing the backfilling of its southern rooms to connect to a new access higher

up, to the south, through a terraced building. During this phase (around 10 BC -

around 40 AD), the east building (Building B) was built, in direct relation to the

sanctuary. This monumental organization corresponds to the reign of Aretas IV,

to whom major developments are attributed in the large buildings of the city center

of Petra (phase II of the pseudo-"Great Temple" and construction of the "Temple of the Winged Lions".

Footnotes

90. Zayadine, Larché & Dentzer-Feydy 2003. |

| 5 | Roman takeover (106 CE) - 1st half of 4th c. CE | The Roman Province |

Description

5a — Building C to the west and Building B to the east were abandoned at the beginning of the 2nd century AD91

Footnotes

91. To explain this phenomenon observed elsewhere on the site, S. T. Parker concludes that two events, an earthquake and the annexation of the Nabatean kingdom occurred in a short period of time: Parker 2009, p. 1590. |

| 6 | mid 3rd - 1st half of 4th c. CE | Destruction and abandonment |

Description

We observe a sandy layer in the western part of the temenos which could correspond to a phase of abandonment or neglect. Then, a fire destroyed the frame of the temple, causing the roof to collapse92. The pediment and the columns of the facade undoubtedly fell later. Much of the sanctuary went out of use. We observe a probable phase of recovery of materials (debris of the statue of Marcus Aurelius). At the same time, the dwellings which developed in contact with the apse monument were also abandoned.

Footnotes

92. This phase of fire was identified during surveys carried out inside the temple: Zayadine 1982, p. 377. |

| 7 | 2nd half of 4th - early 5th c. CE | Reoccupation and change of function of the sector in the late Roman period and the beginning of the Byzantine period |

Description

7a — Following the abandonment of the sector, a second “squat” is observed in the apse and adjacent structures, accompanied by indications of a partial reoccupation of Building B.

Footnotes

93. Russel 1980 [to be developed in the bibliography]. |

| 8 | 6th c. CE | Abandonment of the sector and development of agricultural terraces during the Byzantine period |

Description

Agricultural terrace walls were built in the western sector (Building C) in the 5th-6th centuries AD, replacing the facing blocks of the north wall of the apse. Likewise, it is possible that elements from the sanctuary could have been reused for the construction of churches in Petra, for example in the area of the “Ridge Church”. |

| 9 | Medieval reoccupation |

Description

9a — Installation of an isolated necropolis at the beginning of Islamic rule. Two groups of

burials were located, the first in the collapsed elevation of the apse monument and

the second, to the north, at the foot of the Byzantine terrace walls along the bed

of the wadi. Radiocarbon dating dates them to the Umayyad or Abbasid periods (7th-9th century AD).

Footnotes

95. Zayadine, Larché & Dentzer-Feydy 2003. |

|

| 10 | Development of tourist facilities |

Description

It is in this sector that the first tourist facilities were established during the 20th century. The tour operator Cook organized a camp there in 1934. The “Nazzal Camp” was built in 1943 by leveling and terracing the area to the west of the apse monument. The rest of the southern slope of Wadi Musa remained cultivated in terraces until the clearances and archaeological excavations were carried out throughout the city center in the 1960s-1970s. To encourage the development of tourism, large-scale developments were carried out in the 1980s and 1990s: construction of walls to channel the wadi, a bridge, and several buildings. |

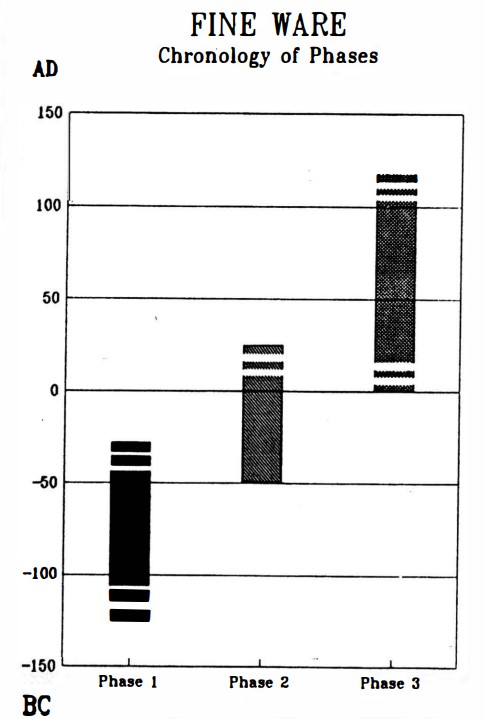

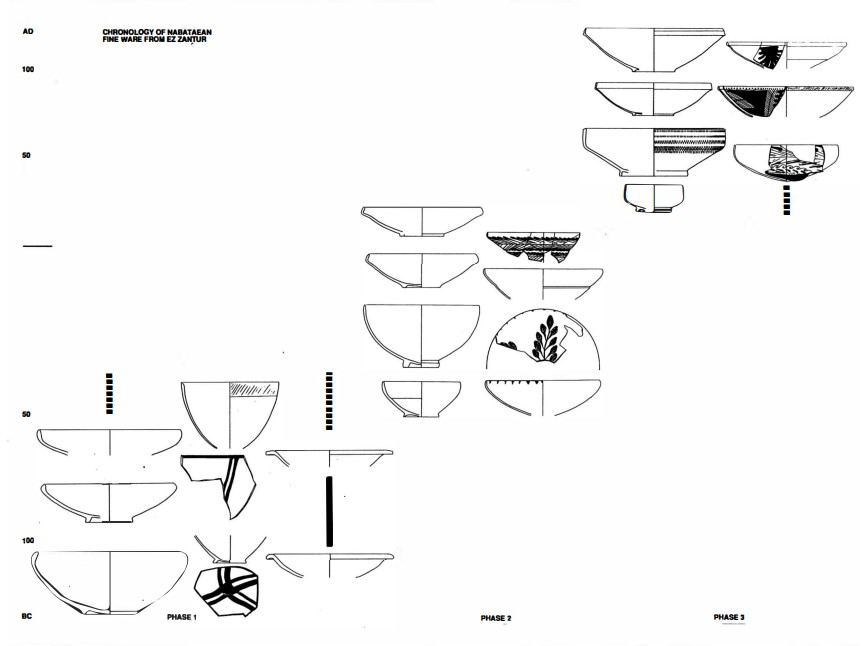

- from Schmid (1995)

- Ez-Zantur Excavations utilized Nabatean fineware chronology of Schmid (2000) - which I don't currently have access to

Left

Chronology of Nabatean finewares

Right

Typology and chronology of the Nabataean fine ware

Both from Schmid (1995)

- Fig. 6.38 - General plan

of western part of the Qasr el-Bint Temenos from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.38

Fig. 6.38

General plan of western part of the Qasr el-Bint Temenos

(Zayadine et al. 2003: 8)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.40a - Detailed plan

from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.40a

Fig. 6.40a

Detailed plan

(Larché and Zayadine 2003: Fig.221)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.52b - East-West

section of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.52b

Fig. 6.52b

East-West section of reconstructed roof of Qasr el-Bint as Larché and Zayadine suggested in final report

(Larche in Zayadine et al. 2003: Fig. 15)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.52a - Axonometric drawing

of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.52a

Fig. 6.52a

Axonometric drawing of reconstructed roof of Qasr el-Bint as Larché and Zayadine suggested in final report

(Larche in Zayadine et al. 2003: Fig. 220)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.53a - Cutaway Axonometric

drawing of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.53a

Fig. 6.53a

Axonometric reconstruction suggested here

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.41d - Isometric of southeast

corner showing the cavity walls and stairs from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.41d

Fig. 6.41d

Isometric of southeast angle showing the cavity walls including the stairs

(Wright 1961a: Fig. 5)

Rababeh (2005)

- Fig. 6.38 - General plan

of western part of the Qasr el-Bint Temenos from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.38

Fig. 6.38

General plan of western part of the Qasr el-Bint Temenos

(Zayadine et al. 2003: 8)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.40a - Detailed plan

from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.40a

Fig. 6.40a

Detailed plan

(Larché and Zayadine 2003: Fig.221)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.52b - East-West

section of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.52b

Fig. 6.52b

East-West section of reconstructed roof of Qasr el-Bint as Larché and Zayadine suggested in final report

(Larche in Zayadine et al. 2003: Fig. 15)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.52a - Axonometric drawing

of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.52a

Fig. 6.52a

Axonometric drawing of reconstructed roof of Qasr el-Bint as Larché and Zayadine suggested in final report

(Larche in Zayadine et al. 2003: Fig. 220)

Rababeh (2005) - Fig. 6.53a - Cutaway Axonometric

drawing of reconstructed temple from Rababeh (2005)

Fig. 6.53a

Fig. 6.53a

Axonometric reconstruction suggested here

Rababeh (2005)

- Fig. 10 - Section of western

peribole from Tholbecq et. al. (2019)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

East-west section of the western peribole.

(M. Bélarbi, C. Besnier, F. Renel)

Tholbecq et. al. (2019) - Fig. 11 - Stratigraphy at the base

of the western péribole (περίβόλος) from Tholbecq et al (2019:36-37)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Stratigraphy at the base of the western péribole (περίβόλος) of the Temple

Tholbecq et al (2019) - © MAFP - Fig. 12 - View of the Stratum F1082

from Tholbecq et al (2019:36-37)

Figure 12

Figure 12

View of the Stratum F1082

Tholbecq et al (2019) - © MAFP

- Fig. 9 - level of spoliation

peribole from the Byzantine period from Tholbecq et. al. (2019)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

View of the level of spoliation from the Byzantine period revealed in the western peribole of the temple.

© MAFP

Tholbecq et. al. (2019) - Fig. 10 - Section of western

peribole from Tholbecq et. al. (2019)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

East-west section of the western peribole.

(M. Bélarbi, C. Besnier, F. Renel)

Tholbecq et. al. (2019) - Fig. 11 - Stratigraphy at the base

of the western péribole (περίβόλος) from Tholbecq et al (2019:36-37)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Stratigraphy at the base of the western péribole (περίβόλος) of the Temple

Tholbecq et al (2019) - © MAFP - Fig. 12 - View of the Strata F1082

from Tholbecq et al (2019:36-37)

Figure 12

Figure 12

View of the Strata F1082

Tholbecq et al (2019) - © MAFP

The beginning of the western peribole was excavated in its northern part, in continuity with work started in 2017. The latter had highlighted four distinct phases, the majority of them late occupations of the sector, as well as different phases of destruction7. The work of the 2017 campaign had stopped on the deposition of sandy colluvium, sealing the abandonment of the sector and thus leaving a berm circumscribed by the wall of the temple, the facade of the imperial monument to the west and the temenos paving to the north. The level reached corresponds to the base of the collapse and presents a series of blocks including architectural elements (column base, frieze) placed flat on the abandoned levels; We provisionally interpret these remains as the remains of one of the phases of spoliation of the imperial monument (Fig. 9). The nature and arrangement of the architectural elements present suggests associating this layer with the search for spolia generated by the construction of the Byzantine churches on the right bank of Wadi Musa. The resumption of work in 2018, carried out in the form of a survey carried out on the substrate, therefore only concerned the lower part of the stratigraphy, largely predating the sequences of abandonment and Late Roman destruction and Byzantine documented in 20178. The observed stratigraphy shows, under the restored level of the peribole pavement, several distinct phases of occupation, relating for the construction phases to Hellenistic, Nabataean and Roman periods (Fig. 10).

7 Renel 2018.

8 Renel 2018, p. 57-59

Directly in contact with the level of preparation of the peribole paving – the latter having been the subject of systematic recovery during the Byzantine era – lie strata of mud (F1076) corresponding to a phase of partial abandonment of the sector (Fig. 11). The discovery, among the shards found associated with this layer, of a plate painted with decoration relating to phase 4 of S. Schmidt and that of a fragment of North African sigillata (probably Hayes 50 type) allows us to date this phase to the 3rd or 4th century AD. These sedimentary deposits are associated with a level of sandstone blocks of corresponding medium modulus at a first level of destruction attributed to the earthquake of 363 AD. In the west corner of the survey, at the height of the opening of the southern bay of the monument to apse, a deposit rests on the masonry of the latter. This level (F1082) is mainly characterized by fragments of marble slabs and veneer of centimeter dimensions interpreted as the result of sorting of materials during an abandonment phase (Fig. 12). Fragments of oil lamps discovered within this embankment all relate to productions from the early Byzantine period.

- Fig. 1 - Plan of sectors

excavated in 2023 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Petra, general plan of the Qasr al-Bint sector, location of operations carried out in 2023

(T. Fournet/ M. Belarbi, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 2 - Overview of sector

excavated in 2023 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Overview of the sector at the end of the [Spring 2023] campaign, towards the southwest

(T. Fournet 2023, CNRS / MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 3 - Destruction layers

of the western peribole from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The western peribole of Qasr al-Bint, towards the south, destruction layers

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 9 - Reconstruction of

southern half of the main facade of the apse monument from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Proposal for the restitution in principle of the southern half of the main facade of the apse monument, simplified working hypothesis

(T. Fournet, MAFP).

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 10 - Overview of

destruction layer from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Overview of the ancient destruction level

(F. Renel, MAFP).

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 16 - Plan of the palace

sector of Qasr Bint from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

General plan of the palace sector of Qasr al-Bint sector, location of operations carried out in Fall 2023

(T. Fournet/M. Belarbi/ P. Piraud-Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 18 - Upper stratigraphic

sequence of P15 in the palace sector from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

view of the upper stratigraphic sequence of space P15, southern section

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 19 - Fallen blocks

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

the level of fallen blocks B2165-2173, towards the northeast

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 24 - Fallen capitals

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

detail of the elements of Corinthian capitals in fallen position in destruction layer B2165-2173

(T. Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 40 - Fallen blocks

in room P16 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 40

Fig. 40

fallen blocks (B2171) present in the upper filling of room P16

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 41 - Fallen architecture

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 41

Fig. 41

detail of a stucco preserved on its facing block (B2171)

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

- Fig. 1 - Plan of sectors

excavated in 2023 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Petra, general plan of the Qasr al-Bint sector, location of operations carried out in 2023

(T. Fournet/ M. Belarbi, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 2 - Overview of sector

excavated in 2023 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Overview of the sector at the end of the [Spring 2023] campaign, towards the southwest

(T. Fournet 2023, CNRS / MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 3 - Destruction layers

of the western peribole from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

The western peribole of Qasr al-Bint, towards the south, destruction layers

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 9 - Reconstruction of

southern half of the main facade of the apse monument from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

Proposal for the restitution in principle of the southern half of the main facade of the apse monument, simplified working hypothesis

(T. Fournet, MAFP).

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 10 - Overview of

destruction layer from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Overview of the ancient destruction level

(F. Renel, MAFP).

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 16 - Plan of the palace

sector of Qasr Bint from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

General plan of the palace sector of Qasr al-Bint sector, location of operations carried out in Fall 2023

(T. Fournet/M. Belarbi/ P. Piraud-Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 18 - Upper stratigraphic

sequence of P15 in the palace sector from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

view of the upper stratigraphic sequence of space P15, southern section

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 19 - Fallen blocks

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

the level of fallen blocks B2165-2173, towards the northeast

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 24 - Fallen capitals

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

detail of the elements of Corinthian capitals in fallen position in destruction layer B2165-2173

(T. Fournet, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 40 - Fallen blocks

in room P16 from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 40

Fig. 40

fallen blocks (B2171) present in the upper filling of room P16

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023) - Fig. 41 - Fallen architecture

from Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

Fig. 41

Fig. 41

detail of a stucco preserved on its facing block (B2171)

(F. Renel, MAFP)

Tholbecq et. al. (2023)

The stratigraphic results for the upper parts match those established in particular in 2017 and 2018 (Renel 2017, 2018): the destruction layer mixes the blocks from the northwest corner of the Qasr and those from the apse monument, fallen at the same time (fig. 3). This layer (F1110) brings together the majority of blocks useful for restoring the imperial facade: column drums, capitals, friezes, cornices, etc.

... This destruction layer is of a different nature from the previous one. It indeed contains numerous fragments of very fragmented blocks, having been exposed to fire, and a majority of blocks coming not from the apse monument, but from the northwest corner of the temple of Qasr al-Bint. We thus found the angle of the denticulated cornice, but also a drip edge front with the start of the pediment (fig. 11). These elements complete and clarify the restitution of this part of the Qasr proposed by Fr. Larché (Zayadine et al. 2003), but above all they confirm a hypothesis put forward in 2017: the destruction took place in two stages. The crowning angle of the temple (entablature and pediment) fell first, probably after the fire of the temple, and only later, after a period of abandonment (sandy layers F1111, F1125 and F1127) , did the apse monument and other parts of the Qasr, already weakened, fell in turn. The levels of the first destruction also include other elements which do not belong to the upper parts of the temple, but on the contrary seem to result from a sorting carried out during an abandonment phase. Among them, a fragment of molded marble bearing a Nabataean inscription (fig. 12). A first reading carried out by Laïla Nehmé mentions “(…) Malichos, king of the Nabataeans” (cf infra, 2.1.4). The material found in the sandy layer associated with this level (F1129) can be dated to the second half of the 4th century A.D.

... To summarize, the chronological sequence brought to light is made up of 8 phases. The first occupation, domestic, was directly placed on the alluvial terrace during the Hellenistic period (phase 1) and is followed by two major construction phases: the foundation of the temple staircase (1st century AD) followed by the imperial monument with an apse ( 2nd century AD). After the temple fire, probably during the second half of the 3rd century AD, its remains remained in place, and a first spoliation of the sector occurred (removal of the paving of the peribole and lead pipes). It was probably the earthquake of 363 which then led to the fall of the blocks in the northwest corner of the temple which were already weakened (which explains their significant fragmentation). A second phase of spoliation followed, at the end of the 4th century , then abandonment, and finally the apse monument and upper parts of the temple that were still in place were completely ruined, on the occasion of an earthquake (419, 749?).

In zone B2, we examined two sectors. The first is located in the northwest corner of courtyard P11, in line with the door giving access to rooms P13 and 14, excavated during the 2012 and 2013 campaigns (fig. 17). This Sondage (noted P15), with an area of 40 m2 , aimed to highlight the supposed return of the Stylobate from the Nabataean court and to identify the phases of late occupation in this sector.

Below a level of sterile sand of aeolian origin, the upper part of the stratigraphy (fig. 18) includes, under a level of falling blocks (B2161), an alternation of ash and carbon deposits and sandy contributions (B2162-B2164 ) on a level of packed earth ground (B2163) corresponding to the reoccupation of this sector following its ruin. A significant amount of furniture was found in these layers, combining ceramics, fauna as well as fragmentary inscriptions (Nabataean and Latin) engraved on marble or alabaster and probably coming from neighboring elevations. The discovery of fragments of LRA 1 and LRA 4b amphorae and dishes in late North African sigillata makes it possible to date this phase from the first quarter of the 5th century, testifying to the reuse of this space following the earthquake of 363 A.D.

Sealed by this sequence, a collapse level (B2165-B2173) was revealed over the entire excavated area (fig. 19). Resulting from the earthquake of 363, it combines facing blocks of the southern facade of the north wing with a series of architectural elements including several Corinthian columns and half-columns (see below for a first study of these blocks).

The blocks of the Corinthian order unearthed this year all seem to be in a fallen position, the three supports (cordiform corner column, free column and pilaster) were therefore located in the immediate vicinity of the Sondage, and fell one on top of the other. The limited extent of the excavation did not make it possible to know where they were located exactly. The alignment of the Doric portico of the courtyard (see fig. 16) extends up to 3.50 m from our Sondage, where it seems to transform into a solid wall. It is in this sector, which was only stripped this year, that the solution of discontinuity was to be found allowing us to move from the Doric order of the court (65 cm in diameter) to this Corinthian order of 53 cm in diameter. diameter. It seems at this stage of the study that the west wing of building B, leaning on the older wall B2204, could have constituted a sort of basilica, widely open onto the Doric courtyard, in a fairly original layout. The extension of the excavation in spring 2024 will make it possible to understand this connection.

The room [P 16] is finally sealed by a collapse level (B2171) containing architectural blocks covered with painted stucco (figs. 40 and 41, see below 3.1).

Recognized over more than three meters, the stratigraphy made it possible to highlight three main phases of occupation (fig. 43). Firstly, a heavily reworked Nabataean state which works with wall B4001 and which probably corresponds to a courtyard space. Only two sandstone slabs (B3061), leaning against the eastern facing of wall B4001, are preserved. Their altimetry (ca. 869.75 m) shows that the circulation levels of this part of the B3 complex are located two meters higher than those of the B2 complex, probably due to the fact that this sector is located on the embankments of a first leveled Hellenistic architectural state (Renel & Fournet 2022, p.99). This level constitutes the excavation limit for this campaign.

Secondly, the installation of the Roman portico must have obliterated part of the Nabatean occupation levels. An east-west wall (B4003) leans against the facade of wall B4001, its foundation (B3060) cutting into the previous levels. Preserved on 3 to 4 courses in elevation, it has a facing of bossed blocks. No related material was found. The existence of an internal facing, however, testifies to the continued use of the spaces located behind the portico during the Roman period.

Finally, the last phase of occupation corresponds to the construction of a crude habitat, in contact with the level of the courtyard (fig. 44). Only the northeast exterior corner of this building (B3059) is included in the excavated area, its internal arrangement therefore not being known. Associated with this phase of occupation, an earthen floor, rich in charcoal inclusions (B3058), yielded fragments of a jar attributable to the second half of the 4th century to the beginning of the 5th century. This habitat which marks the last phase of occupation is sealed by a sequence of embankments massifs associated with fallen blocks with sandy passes (B3052-3053).

- Fig. 1 - Plan of western sector

from Renel (2013)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

General plan of the western sector of the Qasr al-Bint sanctuary.

Renel (2013) - Fig. 2 - Fire and abandonment

layers from Renel (2013)

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

View of the ash level linked to the fire of Qasr al-Bint (C3087-3088) and of the abandonment level (C3106) observed at the start of the western peribole of the temple.

(© F Renel, MFPQB)

Renel (2013) - Fig. 3 - E-W section

of the fill of the western peribole with an earthquake destruction layer from Renel (2013)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

East-west section of the fill of the western peribole of the Qasr al-Bint temple.

(© M. Belarbi, MF-PQB)

Renel (2013) - Fig. 4 - Stone tumble interpreted

as due to collapse of the apse during the 363 earthquake from Renel (2013)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

View of the pile of blocks linked to the fall of the elevations of the apse monument during the earthquake of 363.

(© L. Borel, MFPQB)

Renel (2013) - Fig. 5 - Plan of structures

linked to the Byzantine reoccupation from Renel (2013)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of structures linked to the Byzantine reoccupation.

Renel (2013) - Fig. 6 - Overhead view of

the Byzantine reoccupation of the apse monument from Renel (2013)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Overhead view of the Byzantine reoccupation of the apse monument.

(© R. Gabrielli, CNR)

Renel (2013)

- from Renel (2013:349)

The excavation of the Qasr al- Bint sector, over the past ten years (FIG. 1)2, has revealed a continuous occupation of this part of the city center from the 1st century BC (Mouton et al. 2008: 51-71) until the beginning of the Byzantine period (first quarter of the 5th century). The absence of Byzantine reoccupations in this sector made it possible to work on an undisturbed study area with the exception of tourist developments from the second half of the 20th century. The notable elements of this sector are the emergence of the great Nabataean sanctuary dominated by the temple of Qasr al-Bint, which was succeeded in the western part of the temenos, during the second half of the 2nd century AD, by an imperial propaganda building dedicated to the emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (Augé et al. 2002). The purpose of this communication is to show the complexity of the last phases of occupation of this sector and to highlight the existence of several phases of destruction, distinct from the earthquake of 363 and poorly known to this day in Petra.

The effects of the 363 earthquake are materialized in many sectors of the ancient city by a level of collapse of architectural blocks, a sequence generally assigned to the impact caused by the earthquake (Russell 1980). However, in the area of the Qasr al-Bint temple, several phases of abandonment and destruction marked this religious space before and after this event. They were observed in particular in the eastern sector of the peribole of the sanctuary, below the fall level attributed to the earthquake, and in the central part of the Roman apse monument (FIG. 2).

1 Mission under the program “From Petra to wadi Ramm: the south

Jordanian Nabataean and Arab” under the direction of Chritian Augé

2 we must here thank the late Dr. Fawwaz al-Khraysheh, director of the

Department of Jordanian Antiquities, Mr. Mohammed Abd al-Aziz, head of

the Petra museum and representative of Antiquities in the field, and

Mr. Sulaiman Farajat, former head of the Petra site.

- from Renel (2013:349-351)

On the other hand, it seems clear that following this fire, the temple no longer functioned, the damage having certainly caused irreparable harm. The small size of the excavated area between the temple and the apse monument (west peribole) makes it impossible to measure the impact of this fire on the structure of the imperial building. No trace is perceptible at the rear of this building.

This fire was followed by a period of abandonment materialized by a succession of sterile wind-driven sandy contributions and sequences of colluvium and runoff (locus C3106) coming from the hill located to the south (FIG. 3). These levels completely removed the ash deposit from the fire. These deposits are difficult to quantify chronologically. Their deposition can be spread out over a few days or a few years. The suite present, heterogeneous and rolled, does not allow for reliable and precise dating. The excavation of the “Great Temple” also showed, in its phase X between the 4th and 5th centuries, an abandonment of the complex characterized by the contribution of fluvial deposits (Joukowsky 2009: 294).

On the surface of these deposits, in the peribole of Qasr al-Bint, a thin layer of whitish powdery sandstone (locus C3086, C3105) testifies to the first phase of material recovery. This layeris perceptible at least within the temple and undoubtedly occasionally at the level of part of the decoration of the exedra. We are tempted to associate this phase, at least from a stratigraphic point of view, with the recovery and debitage, or sawing, of elements of imperial marble statuary.

These elements therefore testify to an abandonment or at least a partial disuse of the sacred space of the temenos after the ruin of the temple, the date of which is not yet fully assured, and probably several decades before the earthquake of 363 AD. The impact of this phase on the imperial apse monument still remains difficult to measure due to subsequent reoccupations.

3 This episode is better documented in the north of the Arabian province with the destruction of

the temple of Jupiter Hammon in Bostra and the evidence of Zenobia's passage to Qasr al-Azraq

(see Christol and Lenoir 2001: 170).

4 Identification Christian Augé

- from Renel (2013:351-352)

5 Great Temple, phase IX.

6 Current study carried out by J. Dentzer-Feydy, L. Borel and C. March. It is from these falling blocks that an

anastylosis allows restitution of the elevations the arrangement of the decor.

- from Renel (2013:352-357)

The occupation established on the ruins of the apse monument, although its influence is not completely clear, is defined by two distinct occupation units (FIGS. 5 and 6). The first one, adjoined and partly reusing the podium of the monument, forms the lower part used as a storeroom of a rectangular building measuring 10 m by 6 m (unit P2) taking up the foundations of a bossed building partially collapsed during the earthquake. The preserved volume constitutes the cellar of a larger building which opened onto the apse monument which reuses the platform of the exedra as a complementary room. This was accessed from the temenos by a staircase attached to the podium. The furniture associated with its occupancy levels (loci C2006, 2026) ensures its function. Within the contexts of this main building, the number of storage containers is not negligible. The presence of numerous jugs, dishes (in particular productions imported from North Africa) and small everyday objects designates it as the main place of residence. The cellar retains, on the other hand, in its south-east corner the remains of a religious installation combining a libation cup cut from a reused column and betyles (see below)8.

The second group, more difficult to perceive due to its degree of leveling, corresponds to a courtyard space with the presence of possible lean-tos and a semi-buried building located to the north of the excavation (FIG. 5). It reuses certain rooms of the Nabatean building (rooms P3 and P4) abandoned since the Roman period. Room P4 of the Nabataean building was over-dug about fifty centimeters below its level of primitive soil. Once again, the function of this set poses little problem. Among the material unearthed in its operating levels (locus C4053 and soil C4058), the most important lot is a set of bone objects within which failures and objects in progress testify to an activity its artistic function. In this semi-buried room we are indeed in the presence of a tablet workshop working with camel bone.

The enclosed space between these two sets is interpreted as a courtyard where the main structures encountered are discharge zones (pits C4092, 4109, C4341). Within these dumps, once again, the significant presence of bone fragments and objects in progress attests to the activity of the northern workshop. These pits essentially contain the primary waste products of this activity, with the distal ends of long bones dominating within these contexts. The suite unearthed in association with these bone rejects confirms the functioning of the workshop in a short period of time after 363. A large batch of coins confirms the activity of this occupation nucleus between the last third of the 4th century and the first quarter of the 5th century.

The area located in front of the northern part of the facade of the imperial apse monument also bears witness to this reoccupation. An earthen floor is preserved over the entire area (locus C3009), while a retaining wall is built to the south to delimit and contain the pile of blocks located between the temple and the west wall of the peribole9.

An important piece of suite was brought to light in relation to this habitat. It reflects, contrary to commonly accepted opinion, a material culture still strongly anchored in economic networks and open to large-scale Mediterranean trade. In this corpus, several amphoras come from Aegean productions (Kipitan II and LR3). The dishes fine is present in the form of North African sigillata productions (FIG. 7:2-3), the most frequent forms are the Hayes 59 types, dated between 320 and 420 AD and the Hayes 50 plate, in its variants a and b (350-400 AD ), and to a lesser extent the Hayes 67 form, which appeared around 360 and lasted until 470 (Hayes 1972). Common local ceramics present an assemblage similar to that from the Az-Zantur excavations in late contexts (FIG. 7:4-9). Several painted plates attributable to phase 4 defined by S. Schmid testify to the continuity of fine Nabataean painted productions until the abandonment of this sector (FIG. 7:1).

Only the lamps show a certain originality in the ceramic assemblage brought to light. Their association with a domestic beytl altar and the date of their abandonment could direct the debate towards the religious use of this space. These objects were found associated with a large number of late Roman lamps, classic models for this period (FIG. 7:10-11). They therefore do not represent a model which has supplanted the previous one. We must therefore see here a type of lamp intended for a particular use. All of the comparison models come from contexts where there is little doubt about their use as liturgical instruments, in particular for all of the lamps unearthed in churches. Lamps of this type are similar to a more or less monumental free-standing luminaire, equipped with series of multiple nozzles organized in a stepped manner. This is a luminaire (FIG. 8) intended to be placed on the ground, as shown by the different bases with molded lips found. Several similar fragments were discovered at Jebel Nmeir during a prospection. A very fragmentary copy is presented in the publication concerning Madaba and its territory, coming from Nebo-Siyagha (Alliata 1989: 343-347). It comes from the excavations of the basilica and the chapel (level late 6th, early 7th century AD). Regarding the function of the late structures present to the west of the apse monument, at the level of the courtyard and the semi-buried building, several elements indicate that this is a sector devoted to artisanal activities. All the waste and bone blanks found in the different contexts attest to the existence of a tablet workshop installed after the earthquake of 363 AD during the reoccupation of the space, as confirmed by the presence of a currency in the context of the C434110 dump. This was identified in the excavated building to the north (room P4). The different contexts which yielded these types of remains make it possible to reconstruct the operational chain which led to the production of a corpus of bone objects that is quite typologically reduced11. However, three types of objects resulting from the major stages of production are represented: cut scraps (unusable parts of bone), failed objects (blanks abandoned during production) and objects in progress. They are reflections of everyday life and are made up of everyday objects such as pins, beads, perhaps pyxides and to a lesser extent spoons (FIG. 9).

The abandonment of this sector took place, according to the data, essentially numismatic, in the first quarter of the 5th century. It is characterized in the area studied by a violent destruction by fire of the building adjacent to the apse monument. A layer of several centimeters of ash associated with charred beams lies on the ground. On the other hand, several clues indicate intentional destruction of the place before its fire. The betyls are overturned (FIGS. 10-11) and the objects related to this cult space smashed12. The presence of a dagger and a winged arrowhead (Inv. C2028.172, FIG. 12) in this layer of ashes constitutes the most remarkable element of this phase. A second set comes from the abandoned levels, also characterized by traces of fire, of the building located to the east of the temple (zone B; FIG. 1). These are a second winged arrowhead, fragmentary bronze plated breastplates (Inv. B1015.007; FIG. 13)13 and fragments of siya in bone corresponding to several examples of so-called reflex and “composite” arch (Inv. B2005.001; FIG. 14). It is difficult to say if they are present in this context of rejection due to the presence of a local manufacturing workshop or if they are the remains of combat14.

All these elements reinforce the idea of a violent and definitive intervention in this sector, with no perceptible subsequent reoccupation15.

7 A partial reoccupation of the temple is, it seems, proven if we associate it with the reduction of the cella door (Zayadine 1982: 376).

8 It is interesting to note the discreet character of this place of worship relegated to the back of a cellar.

9 This structure, frustrated in its implementation, was only identified late during the excavation. Partly covered by the colluvium of the hill,

it delimits a space located in the axis of the apse of the imperial monument, probably empty of any architectural element recovered

in this place due to the lesser thickness of the collapse.

10 Coin of 364-375 (Inv. C4341.001; identification C. Augé).

11 Ongoing study carried out by Bénédicte Khan (Doctoral student, University of Paris I — Sorbonne).

12 The reassembly of the containers present in this context shows the fragmentation and dispersion of certain individuals over the entire area of the cellar.

13 The most important lot from context B1015 constitutes a section of armor with another 15 plates held in place by their system mounting (dimensions: h: 24 mm, 1: 17 mm).

14 The composite reflex arc is, by its shaping technique, the most technologically sophisticated and requires a high degree of

qualification on the part of the craftsmen. It is therefore not an object that can be easily separated.

15 Following this abandonment, only agricultural terrace walls from the Byzantine period (6th century) and a series of burials from the

beginning of Islam have been identified in this sector of the city center.

- from Renel (2013:357-358)

This movement of abandonment or destruction of pagan sanctuaries is observed quite widely in the southern Levant. We see the same phenomenon in Banias, where the pagan sanctuary of Pan was abandoned in the same period of time. Unlike Petra, however, we do not observe tangible traces of destruction, but rather the result of a “voluntary” abandonment of the complex (Berlin 1999: 41).

This fight against paganism seemed to have taken the side of violence fairly early on, the action of the monk Barsauma, if it proved correct, would find its place perfectly in this ideological current. In Greece, Christianization seems to have been slow and late; we had to wait until the middle of the 4th century to see the destruction of the last sanctuaries (Laurant 2004: 39-40). All these elements combine to show that at the same period, in the eastern part of the Mediterranean basin, groups rose up within the developing Christianity to overthrow ancient cults and impose their cult definitively. It is also interesting to note that the main ecclesiastical remains unearthed in Petra date from after this date: the “Ridge Church” was built in 423, the transformation of the Urn tomb into a church dates back to 446 AD under the episcopate of Jason (McKenzie 1990: pl. 97; Sartre 1993: 82).

The presence of the late settlement excavated near Qasr al-Bint, marked by the presence of abundant liturgical furniture (betyls and lamps) in a place with very symbolic connotations, could therefore to be the expression of this pagan resistance, defeated in one way or another by the arrival of Barsauma, and by that of triumphant Christianity, marking a decisive turning point in the history of the city.

16 The Syriac Barsauma of Nisibis also destroyed synagogues in Judea for three years from 419.

The work carried out during the spring campaign in sector B2 (western palatial complex) corresponds to an extension to the east of the survey carried out in 2023 (Renel, Fournet 2023, p. 35–40) in the northwestern part of the courtyard of the stylobate (space P15) (fig. 2). This represents an excavation of 60 m². It aimed to determine the nature and chronology of the portico of the courtyard at its western end, in contact with the peribolus of the temple, to understand its supposed return and to identify the phases linked to the late reoccupation in this sector before its abandonment.

Already partially excavated in 2023, this space presents a stratigraphy quite similar, in its upper part, to that of the previous campaign, the excavation having however revealed more architectural phases.

Beneath a level of sterile sand mixed with brown sandy loam (US B2212), linked to the agricultural exploitation of the area during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the upper stratigraphy is defined by a level of destruction (US B2222). This level of falling blocks corresponds to the definitive abandonment of this part of the complex. It comprises, for the most part, facing blocks of wall B2201 constituting the limit of the north wing. It seals a level of occupation, in the form of squatting, delimited to the east by the low wall B2216 and to the south by a tabûn-type domestic hearth (structure B2217; fig. 3) and its associated structures. These light structures make it possible to identify a courtyard space with a lean-to.

Among the few sherds linked to this occupation, fragments of cooking pots, a jug and an amphora body from Aqaba date from the end of the 4th century or the beginning of the 5th century AD, testifying to a reuse of the courtyard following the earthquake of 363 and probably abandoned after that of 418/419.

The stratigraphy present under this phase is similar to that observed during the 2023 campaign, i.e. a sequence of ash and sand deposits (Us B2223–B2224 and B2225) (figs. 4 and 5), indicating a first phase of reoccupation of the area during the Late Roman period. These levels have yielded a large quantity of material, including domestic ceramics, amphorae, oil lamps, fauna and fragmentary inscriptions. Among these, a bilingual inscription (Nabataean and Greek) mentions the name of Obodas (see identification by L. Nehmé in this volume, p. 47). The discovery of fragments of Cilician amphorae LRA 1 and Palestinian amphorae LRA 4b and dishes in late North African sigillata (Hayes form 61A/B) allows us to date this phase between the end of the 4th and the first quarter of the 5th century. It is also worth noting the strong representation of painted plates from phase 4 depicting birds and characteristics of this phase (fig. 6).

Sealed by these levels of domestic waste, a phase of spoliation of the courtyard paving can only be dated more precisely between the Roman period and the Late Roman period. Indeed, the ceramic material present on the surface of the embankment constituting the preparation of the ground seems to be contemporary with the shards discovered in the upper levels.

The surface of this level being strongly disturbed by ravine phenomena, two specific surveys were able to be carried out highlighting two distinct architectural phases, both dated to the Nabataean period (fig. 7). The first survey, located in the northeast corner of the excavation, revealed the foundation of wall B2201, which forms the southern facade of the northern wing of complex B2. Its elevation consists of a facing of well-dressed sandstone blocks resting on a raft of sandstone and limestone blocks bound with sand (B2253) which cuts into natural red sands of aeolian origin.

Although no dating furniture was found in association with the raft in this survey, the wall was dated by the surveys dug further north in room P1 (1999 campaign). The associated material allows this first architectural phase to be attributed to the reign of Obodas II or the beginning of that of Aretas IV (end of the 1st century BC).

The second identified architectural phase corresponds to the installation of the portico in the courtyard. Engaged in the southern berm of the survey, two columns (B2214 and B2215) and a pillar (B2213), aligned along an east–west axis, extend those uncovered in 2014 to the east (Renel 2014, p. 97–99). The column shafts retain part of their original stucco (fig. 8). They rest on a stylobate (B2239) built on an overhanging foundation (B2240) made of sandstone blocks (fig. 9).

To the north, opposite the columns and the pillar and leaning against wall B2210, three masonry blocks have been identified (Us B2232, B2234 and B2235). Made up of blocks placed on edge on square-plan rafts, they correspond to the foundations of pilasters added during this phase; the elevations were recovered during a phase of spoliation whose chronology could not be specified.

In relation to this architectural phase, the remains of a hydraulic system (fig. 10) comprising two pipes were revealed under the Nabataean soil preparation level (Us B2242). The most important (Us B2245), whose route towards the entrance vestibule (space P2) follows a west–east axis, parallel to the stylobate. Its conduit, about fifty centimeters wide, is delimited by two low walls made with limestone pebbles from the wadi, covered with sandstone slabs. Its base is paved with limestone blocks. Its filling testifies to a slow sedimentation, very hydromorphic and devoid of material.

To the southwest, it is connected to a second canal (Us B2237), oriented south–north, which passes under the foundation of the stylobate, the whole constituting a probably complex evacuation network whose outlet is to be located under the influence of the temenos. It is to be compared with the discovery in 2023 of another pipe (Us B2177) (Renel, Fournet 2023, p. 39) which seems to extend the system to the west and continue to the north under the threshold of the door giving access to room P13.

The phase related to the construction of the portico is dated by the discovery of ceramics in the foundation of the stylobate and in the level of preparation of the ground, in particular thin-walled tableware including Nabataean painted plates belonging to phase 3a of Schmid, dated between 70/80 and 100 AD.

An earlier phase could be partially observed in the northeast corner of the survey. It is attested by the remains of another hydraulic conduit (Us B2250) intersected by the installation of structure B2245. Presenting the same construction method, it retains part of its cover. Its filling (Us B2252) which includes numerous charcoals has yielded only rare unidentifiable rolled shards. On the other hand, the furniture present in its construction trench includes a series of shards including a fragmentary glazed base from Mesopotamian productions which are attributable to the late Hellenistic period (2nd–beginning of the 1st century BC).

Alongside this survey, the cleaning of the southern berm of the old surveys (Renel 2014, p. 97–99) made it possible to identify other walls erected with recovered elements observable at the level of the stylobate courtyard further east. This includes, among other things, the blocking of the intercolumnation built with reused blocks including column shafts (fig. 11). The dating of these different structures remains difficult to establish, however.

The report of the October 2023 campaign ended with numerous questions related to the discovery, in a fallen position, of elements of a beautiful Corinthian order in the northwest corner of the courtyard of building B (sector P15) (Fournet-Renel 2023, pp. 40–48). This order, with a diameter of approximately 55 cm, probably placed on a pedestal, seemed incompatible with the portico that had been uncovered further east during previous campaigns (Fournet 2017, pp. 43–61), composed of a Doric order with a much larger diameter, approximately 75 cm. The articulation in plan between these two orders remained incomprehensible at the end of the campaign.

The extension of the survey towards the east (fig. 12) this year revealed a corner pillar (cordiform column B2213) preserved on 5 courses (approx. 2.20 m high), as well as two columns, further east (B2214–B2215). These three supports, with a diameter of approx. 80 cm (with their thick coating), placed on a stylobate (B2239), are similar to those unearthed in 2014, and indicate that the Doric portico, which was thought to be interrupted to give way to another construction (basilica?) of the Corinthian order, in fact continued to the northwest corner of the courtyard, where it turned back to the south, as we had imagined before the 2023 discovery of the Corinthian order in a fallen position.

The only possible option, which we should have considered already last year, is that the Doric order does not belong to the ground floor of the monument, but rather to an upper register, to an upper-floor portico. The nature of the Corinthian elements (isolated column and cordiform pillar, as on the ground floor), their scale (slightly smaller diameter than those on the ground floor), as well as their position of discovery (exactly aligned above the corner of the ground floor portico), all now support this conclusion.

The extension of the excavation also enriched the catalog of blocks found in a fallen position (fig. 13), based on which we can propose a complete graphic anastylosis hypothesis for the order of this first floor (see infra). It also yielded other, rarer elements, also in a fallen position, but originating from the order of the ground floor:

The first element found in the highest level of destruction (US B2222), just north of the cordiform pillar B2213 (see its find position on the section in fig. 14), is a large fragment of a Doric capital (B24-07, fig. 15). The presence of a projection articulating a curved part (1/2 column) and a smooth part (pillar) makes it possible to restore the entirety of this cordiform capital. It has a similar profile to the capital from the old excavation carried out to the south of the vestibule, in front of the same portico (Fournet 2017, p. 48, Fig. 4, Capital B.11).

The second is more interesting. It is a set of four large fragments (B24-27&28) found in connection with the foot of the cordiform pillar B2213 (fig. 16). Located in the same level of destruction as the elements of the portico of the floor, these fragments are made up of sandstone flakes embedded in a thick mortar (total maximum thickness of approx. 20 cm). The face located against the ground is curved, smoothed, except for the last 15 centimeters of fragment B24-27, which are made up of slightly recessed and curved cut sides, characteristic of sharp-edged fluting. Their width allows 22 to be restored on the complete circumference, 11 on the half-column (fig. 17).

Once reassembled and modeled, this group clearly appears as a large section of the facing of the cordiform pillar B2213, detached from the half-column and fallen to the ground. It attests to the presence of sharp-edged fluting on the upper part of the shafts, where we had restored smooth shafts in 2017. The rear face of fragment B24-27 has the trace of a horizontal joint between two courses (fig. 17), which allows the assembly to be virtually repositioned on the column (fig. 14). The start of the sharp-edged fluting was at about 195 cm from the stylobate. Up to this height the shafts are therefore smooth, and seem to have been without a base, since the coating of columns B2214 and B2215 is preserved up to the level of stylobate B2239.

The hypothesis of a molded base (in decorative stone, marble or other), placed against the smooth shafts, in the manner of the annular bases of the temple with winged lions, remains possible. The stylobate is however the same width as the columns (about 80 cm), so part of these bases would be overhanging. This is therefore unlikely, unless the stylobate was also entirely covered in marble (this is a possibility, due to the numerous fragments found, but also in view of the recovery phase of all the paving in the area, which was very systematic and early).

In the previous report, we noted the discovery, in the eastern part of the survey, of numerous fragments of a thick red coating, flat or curvilinear. They were in direct proximity to this column element of the ground floor, and their thickness seems to correspond to this order rather than to that of the upper floor (see below, the coating preserved on the blocks is less thick, and never red). It is therefore likely that we can restore, for the Doric order, a coating of a solid red color (at least on the smooth part of the shafts).

The height of this order was estimated in 2017 at 4.75 m, a measurement calculated based on the proportions of the exterior porticoes of the Urn Tomb, whose Doric capitals and intercolumnation are comparable1. The presence of fluting perhaps changes the situation a little, since when they do not decorate the entire column, it is traditionally considered that they start at a third of the height. In our case, with a start located at 1.95 m from the ground, we would have a high order of 5.85 m.

Examples of preserved fluted columns are rare in Petra, and the comparison is limited. The only ones that can really be measured are located in triclinium 235 of the funerary complex of the "Roman Soldier". The order is, however, Ionic, and the fluting is rudentate (and not sharply edged as here), so the comparison is delicate. We note that the start of the fluting is not exactly at a third, but a little higher, at 4/11 of the height. In our case, the total height would then be 11 x 1.96/4 = 5.40 m (which corresponds, considering the diameter at the base, to a proportion of 6.5:1).

We must leave Petra to find Doric comparisons with fluting. In this preliminary study we will be content with a well-known Alexandrian example, the tombs of "Mustapha Pasha"2. The columns, comparable to ours in the fluting, but equipped with simpler capitals, have fluting that only begins at about 2/5 or 5/12 of the height. In our case, with fluting starting at 195 cm, this would give a column about 4.70 or 4.90 m high. This gives a column ratio of approximately 6:1, which is also comparable to Alexandrian examples, which respect ... From this point of view, the proportions follow Vitruvian principles. However, they belong to the Hellenistic period and are therefore older than our examples, which date to the 1st century CE. At this stage of study, we can only consider that the ground floor order must have measured between 4.80 m and 5.40 m in height. In the drawing of fig. 14, we used the second option (proportion 6.5:1, 5.40 m), prioritizing at this stage local comparisons (Urn Tomb, triclinium of the Roman soldier), which are also chronologically closer.