Khirbet es-Suyyagh

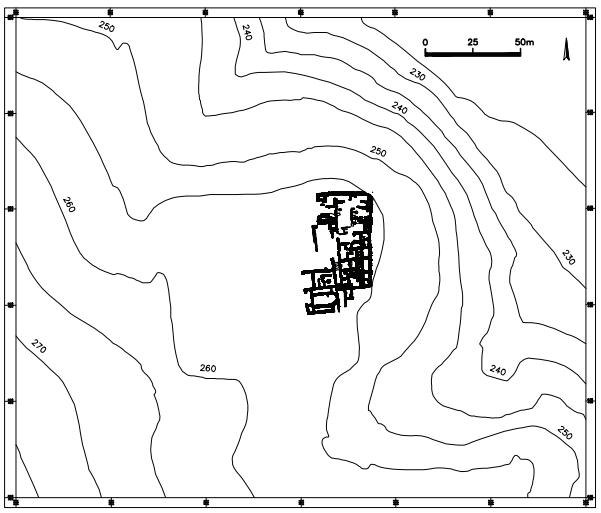

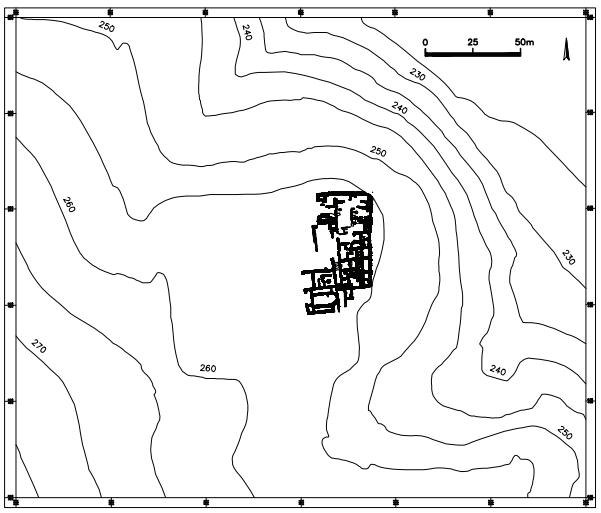

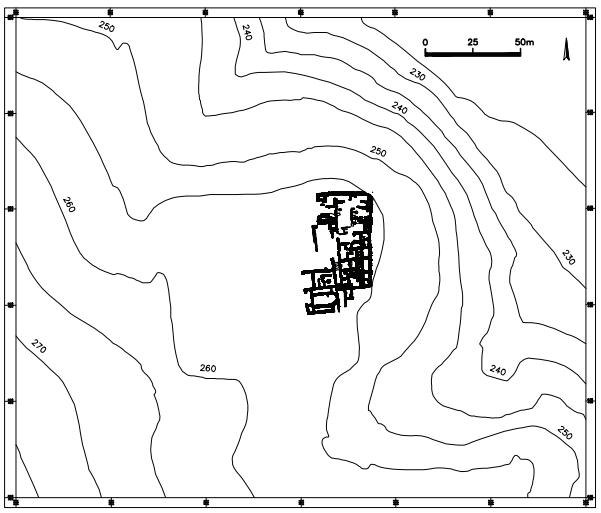

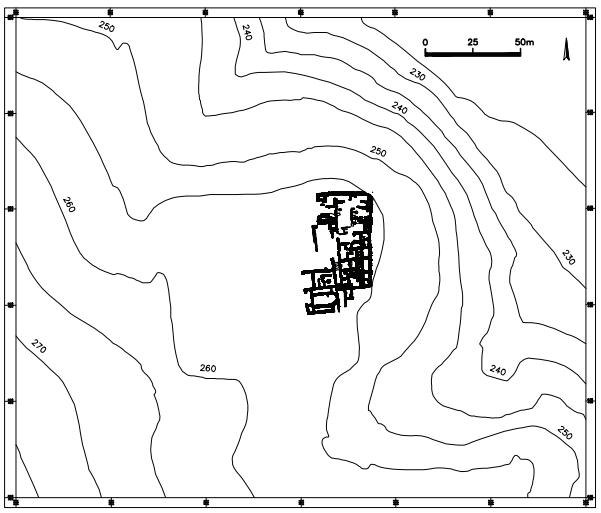

Figure 2.12

Figure 2.12General view of the site, looking north

Taxel et al (2009)

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Khirbet es-Suyyagh | Arabic |

Introduction

- Parsed from Taxel et al (2009)

History of Research

- from Taxel et al (2009)

In 2004, prior to the present excavation, a limited salvage excavation was conducted at the site by E. Kogan-Zehavi, on behalf of the IAA. The excavation included nine squares and several trenches which were dug in different places throughout the area. These probes yielded parts of a Late Byzantine and Early Islamic complex, to which three architectural phases were attributed. Based on these finds, the excavator was the first to suggest that the complex was a monastery (Kogan-Zehavi 2008).

The excavations conducted at Khirbet es-Suyyagh by the author in 2004 and 2005 included an area of more than 0.2 hectares, within which a built complex was almost fully unearthed. The lion’s share of the remains and finds belong to the Late Byzantine and Umayyad periods, reinforcing Kogan-Zehavi’s suggestion that the complex was a monastery.3 This monastery was part of a small group of Byzantine rural monasteries known so far in the Judaean Shephelah, and one of the few that has been excavated. The present excavations, therefore, provide important additional knowledge not only about the history of the Judaean Shephelah during the discussed periods (and others), but also about the general phenomenon of rural monasticism in Palestine and different aspects related to it.

Footnotes

2. I wish to thank Y. Dagan (IAA) for the permission to quote yet unpublished details from the final report of the Ramat Beth Shemesh project.

3. For a preliminary report on the 2004 season of excavations, see Taxel 2006.

Maps, Aerial Views, Plans, Drawings, and Photos

Maps

- Fig. 1.1 - Location map

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

Location map of Khirbet es-Suyyagh.

Taxel et al (2009)

Aerial Views

- Fig. 2.12 - Aerial view of the

site from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15

Figure 2.12

General view of the site, looking north

Taxel et al (2009) - Approximate location of Khirbet es-Suyyagh in Google Earth

- Approximate location of Khirbet es-Suyyagh on govmap.gov.il

Plans and Drawings

Site Plans and Drawings

Normal Size

- Fig. 1.1 - General plan of

Khirbet es-Suyyagh from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

General plan of the site.

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.13 - General reconstruction

of the monastery from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15

General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest

Drawing by Yura Smertenko

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.1 - Plan of Phase I

and Phase II from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Plan of Phase I and Phase II .

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.75 - Plan of Phase III

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.75

Fig. 2.75

Plan of Phase III

Taxel et al (2009)

Magnified

- Fig. 1.1 - General plan of

Khirbet es-Suyyagh from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 1.1

Fig. 1.1

General plan of the site.

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.13 - General reconstruction

of the monastery from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15

General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest

Drawing by Yura Smertenko

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.1 - Plan of Phase I

and Phase II from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1

Plan of Phase I and Phase II .

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.75 - Plan of Phase III

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.75

Fig. 2.75

Plan of Phase III

Taxel et al (2009)

Area Plans and Drawings

Gateway

Normal Size

- Fig. 2.16 - Reconstruction of

the gateway from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.16

Fig. 2.16

Reconstruction of the gateway, looking north

Drawing by Yura Smertenko

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.15 - Plan of the

gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15

Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery.

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.76 - Plan of Phase III

gatehouse area and the southern area from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.76

Fig. 2.76

Plan of the gatehouse area and the southern area of the monastery during Phase III.

Taxel et al (2009)

Magnified

- Fig. 2.16 - Reconstruction of

the gateway from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.16

Fig. 2.16

Reconstruction of the gateway, looking north

Drawing by Yura Smertenko

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.15 - Plan of the

gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15

Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery.

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.76 - Plan of Phase III

gatehouse area and the southern area from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.76

Fig. 2.76

Plan of the gatehouse area and the southern area of the monastery during Phase III.

Taxel et al (2009)

Church Complex

Normal Size

- Fig. 2.57 - Plan of church complex

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.57

Fig. 2.57

Plan of the church complex.

Taxel et al (2009)

Magnified

- Fig. 2.57 - Plan of church complex

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.57

Fig. 2.57

Plan of the church complex.

Taxel et al (2009)

Tower

- Fig. 2.31 - Plan of the tower

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.31

Fig. 2.31

Plan of the tower.

Taxel et al (2009)

Photos

- Fig. 2.58 - The Church with asymmetric

apse from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.58

Fig. 2.58

The church (30):

Above) looking north

Below) Section C-C (see Fig. 2.57) through church, looking west.

JW: Note asymmetric apse

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.62 - Southern (repaired) wall

of the apse from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.62

Fig. 2.62

the southern (repaired) wall of the apse (W223), looking northwest.

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.77 - Phase III blocking wall (W210)

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.77

Fig. 2.77

the southeastern corner of Hall 31 and the Phase III blocking wall (W210) of the entrance corridor

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.78 - eastern end of W210

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.78

Fig. 2.78

the eastern end of W210, built over the threshold of Courtyard 2

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.85 - Phase III walls (W115, W116)

in Room 13 from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.85

Fig. 2.85

Phase III walls (W115, W116) in Room 13, looking north

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.32 - Fracture in the

Northern doorway of the tower from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.32

Fig. 2.32

the northern doorway of the tower, looking east.

JW: Fracture may be due to soil creep along slope to the left

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.84 - Crushed storage jar

between W131 and W147 from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.84

Fig. 2.84

Crushed storage jar and a lid between W131 and W147.

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.34 - Crushed Storage Jars

in the basement from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.34

Fig. 2.34

Crushed storage jars in the northeastern corner of the basement (L148).

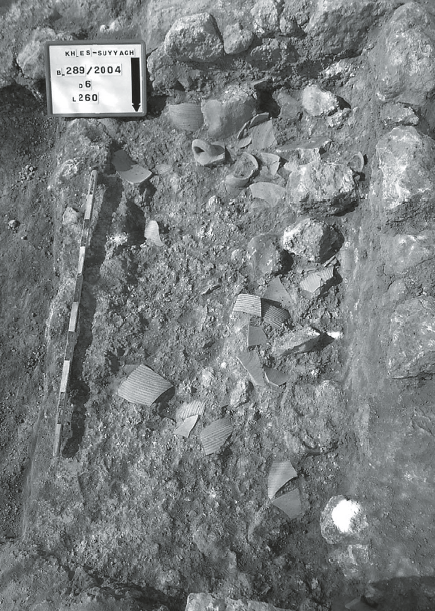

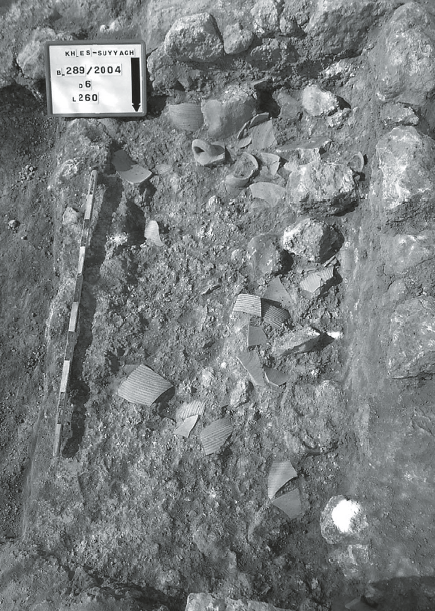

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.27 - Crushed pottery on the floor of room 5

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.27

Fig. 2.27

Crushed pottery on the floor of room 5 (L260).

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.87 - Re-used marble fragment

in Phase III wall (W209) in Hall 31 from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.87

Fig. 2.87

Phase III wall (W209) in Hall 31, looking north. Note the reused marble column fragment at the middle of the wall

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.63 - Re-used Building element (lintel)

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.63

Fig. 2.63

A lintel reused in the central wall of the apse (W223).

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.24 - Threshold of Courtyard 2

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.24

Fig. 2.24

the threshold of Courtyard 2, looking west.

Taxel et al (2009)

Phasing

- from Taxel et al (2009)

| Phase | Period | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| I | THE LATE HELLENISTIC/EARLY ROMAN AND LATE ROMAN/EARLY BYZANTINE PERIODS |

Some find spots and a few architectural remains that pre-dated the foundation of the Christian monastery were unearthed. The only feature which can be securely dated to the late Hellenistic/Early Roman period (i.e., the late Second Temple period) is a cistern unearthed in Squares D-E/9-10 (Figs. 2.1:24, 2.2, 2.3). ... The relatively small number of finds belonging to this period and their concentration in the northern part of the site, points to small-scale activity taking place here during that time. Based on the finding of the cistern and the relatively varied pottery assemblage, it seems that there was here a small farmhouse, perhaps inhabited by no more than one family (Chapter 10). |

| II | THE LATE BYZANTINE/EARLY UMAYYAD PERIOD |

The architectural picture of Khirbet es-Suyyagh, as known from the excavations, originated mainly in the Late Byzantine to Abbasid periods. Two major stages of site formation can be identified within Phase II, which represent the time of the monastery’s heyday during the Late Byzantine and early Umayyad periods (the 6th century CE to late 7th/early 8th century CE). Attributed to the first stage (Phase IIA) is the foundation of the monastery and its main time of existence, which ended in the destruction of parts of the monastery sometime around the mid-7th century CE. The second and shorter stage (Phase IIB) represents the time between its reconstruction and its abandonment by the monastic community. It must be noted that there were sometimes difficulties in determining whether a certain remnant or feature belonged to Phase IIA or Phase IIB, or to Phase IIB or Phase III. ... Phase IIB seems to have ended around the late 7th/early 8th century. |

| III | THE LATE UMAYYAD/'ABBASID PERIODS |

Due to later use in the post-monastery phase and the remodelling which took place at that time, it was not always easy to distinguish between the remains and finds of Phases IIB and III. However, the nature and location of some of the features which postdate Phase II clearly indicate that at the time of their construction the site no longer functioned as a monastery, and therefore they can be securely attributed to Phase III. |

End of Phase IIA Earthquake(s) - 7th century CE

Discussion

Taxel et. al (2009)

Khirbet-es-Suyyagh in Context

- from Taxel et al (2009:219-221) - Chapter 10

- Taxel et al (2009:219-221) repeat some errors and overstatement by Russell (1985) and, possibly, excavators who were relying on Russell (1985). Comments by JW have been added for clarification.

Theoretically, the Sassanid-Persian conquest of 614 CE could have been responsible for the destruction at the end of Phase IIB. The literary sources which deal with the conquest mention the destruction of churches and monasteries and even massacre of Christian communities in western Galilee but mainly in Jerusalem and nearby (Schick 1995:21, 31, 33-39). However, these events occurred only in the initial stage of the conquest, and were not reported from the period of the Persian occupation which lasted until 628 CE. Some of the damaged buildings – mainly in Jerusalem – were repaired soon after the conquest, and the reoccupation of some of the abandoned monasteries also occurred at about that time (Schick 1995:41-43). Some renovations were probably carried out after the renewal of the Byzantine rule in Jerusalem in 630 CE, but these were few and undocumented in the archaeological record (Schick 1995:65-67). Therefore, it does not seem very plausible that the monastery of Khirbet es-Suyyagh was damaged in the conquest of 614 and remained partially destroyed (and abandoned?) until at least 629/630 CE. Furthermore, the nature of the damage and renovations does not indicate violent destruction by human agency. The almost total absence of traces of fire weaken the possibility that the monastery of Khirbet es-Suyyagh was damaged during the Persian conquest.

Nor does it seem that this destruction should be attributed to the Muslim conquest of Palestine in the 630s. There is little evidence for deliberate violent destruction of Christian sites at the beginning of the Early Islamic period (Schick 1995:128). Nonetheless, the excavator of nearby Khirbet Fattir suggested that the destruction of that site in the 7th century was caused either by the Persian invasion or by the Muslim army who defeated the Byzantines at the battle of Ijnādayn in 634 CE and “…plundered and destroyed the Christian villages with their sanctuaries in the neighborhood…” (Strus 2003:430). Similarly, the Persian or Muslim conquest was identified as the cause of the destruction of the farmhouse of Khirbet el-Jiljil, although the excavators did not rule out the possibility that an earthquake was responsible (Strus and Gibson 2005:72)..

One of two earthquakes documented by contemporary and later sources could have hit Khirbet es-Suyyagh. According to Russell, the first earthquake occurred in September 633 (1985:46), although Guidoboni predates this event to 631/2 CE (1994:504). The intensity of this earthquake and the exact area affected by it are unknown. The only place mentioned in the sources as damaged by the earthquake is the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem [JW: This was a mistake made by Michael the Syrian attributing seismic destruction to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher was destroyed in 614 during the Sasanian conquest of Jerusalem and was fully rebuilt when Omar visited it in 637 CE. See Sword in the Sky Quake -> Textual Evidence -> Michael the Syrian. In fact, part of the mystery of the Sword in the Sky Quake is that no locations are mentioned by the various authors]. According to Russell it [the Sword in the Sky Quake] was less destructive than other recorded earthquakes and affected a relatively limited area (1985:46) [JW: Russell (1985) lacked sufficient evidence to make such a statement]. Schick suggested that this earthquake could have been responsible for the destruction of ecclesiastical complexes in Palestine and Transjordan, mainly along the Jordan valley (1995:24, 66, 125).

A stronger earthquake occurred in June 659 followed by another in 660 CE (Russell 1985:47) which caused destruction throughout Palestine and Transjordan [JW: We do not know if the Jordan Valley Quake(s) was/were stronger than the Sword in the Sky Quake and, more importantly, which quake(s) would have generated higher intensities at Khirbet es-Suyyagh]. The sources mention several specific settlements and ecclesiastical complexes in Jerusalem and the Jordan valley that were damaged or destroyed by this earthquake, such as the monastery of Euthymius [JW: true]. Indeed, excavation of this monastery revealed evidence of its almost complete renovation after the earthquake of 659 CE (Hirschfeld 1993:357) [JW: also true]. This earthquake was identified archaeologically also at other sites in the Jordan valley, including Pella (Schick 1995:66, 125- 126; Walmsley 1992:254) [JW: Walmsley dated seismic destruction at Pella to the 7th century], and at Caesarea (Raban, Kenneth and Bukley 1993:59-61) [JW: Langgut et al (2015) report that destruction of a building in Caesarea Maritima was tentatively attributed to the 659 CE earthquake by Raban et al (1993:59-61)].

It is hard to determine which of the two above-mentioned earthquakes hit Khirbet es-Suyyagh. Apparently, the finding of the 629/630 coin below the church mosaic make the option of the 631/2 or 633 earthquake more plausible. However, archaeological evidence from other sites in Palestine and the neighbouring regions clearly shows that coins of Heraclius remained in circulation well into the Umayyad period (Magness 2003b:149, 170; Walmsley 2000:332-333). On the other hand, support for the 659/660 earthquake can be given by the pottery found in Loci 181 and 183, which can be dated to the mid-late 7th century. Thus, the possibility that the site was hit by the 659/660 earthquake rather than that of 631/2 or 633 seems somewhat more reliable. Still, the possibility that another undocumented earthquake hit the site sometime around the mid-7th century, as maybe happened at Beth Shean, cannot be ruled out (Tsafrir and Foerster 1997:143-144).

Earthquake-related Damage Discussion

- from Schmuel Marco in Taxel et al (2009:186-187) - Chapter 9

The area of the large courtyard (Fig. 2.1:8-10) had been completely rebuilt after a destructive event. An earlier construction phase, which is observed south of the centre of the courtyard (Fig. 2.1:9), is covered by a later floor. Fallen masonry and subsequent repairs were observed in the southern part of the apse of the church, with its inner face remaining asymmetric. Since the damage is observed close to the foundations of the church it seems that the damage had a pervasive affect on the entire structure. A section of about 10 m in the southern end of W33 seems also to have been rebuilt. Similarly, in W100 there is a warped contact in room 19, where two different styles of masonry meet but are misaligned.

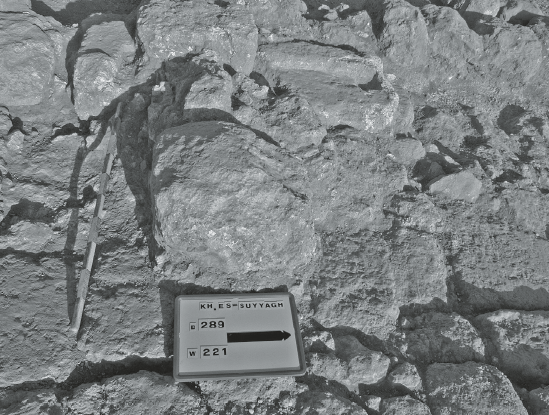

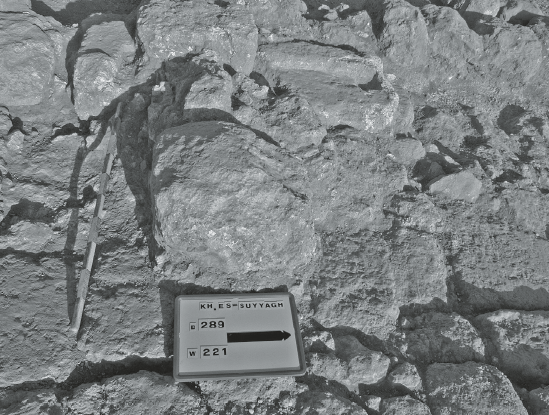

Another type of damage appears in two broken door thresholds, that of the main gate and that of the small courtyard in the south of the monastery. The large, monolithic and nicely carved stones are placed in-situ but broken by a width wise crack into two pieces. Assuming the thresholds were carved from intact rocks without significant fractures, we can envision strong vertical acceleration, perhaps of the order of 1g, which caused the fracturing. Such strong shaking is known based on modern earthquakes to occur either near the epicentre of strong earthquakes (of the order of magnitude 7 and above) or in places with strong local amplification of seismic waves.

Each of the damaged elements alone would not suffice to indicate an earthquake as the damaging agent. However, the occurrence of many such elements, the extensive repair and reconstruction of features without any sign of human violence and in short time, together with the frequent occurrence of earthquakes in the region supports the association of the damage to earthquake/s.

Ideally, the proposed evidence for earthquake related damage would be corroborated by historical accounts and/or by additional independent archaeological observations in contemporary sites and/or geological evidence. Geological evidence for strong earthquake shaking in the vicinity of the site is found in the form of fallen cave deposits (speleothems), in particular stalactites and stalagmites. The damage events to speleothems were dated using the Uranium-series method (Kagan et al. 2005). Several breakage events of speleothems were identified in the Soreq and Har Tuv caves, the age of the youngest of which is estimated by five millennia. A doctorate in progress by E. Kagan (the Hebrew University of Jerusalem) indicates that the analytical methods that were used in the previous stage (i.e., alpha counting) are not sensitive enough and by using MC-ICP-MS system younger historical events are emerging (personal communication).

Hence, the regional seismic activity is capable of triggering severe damage in the vicinity of Beth Shemesh. The time of the damaging episode in Khirbet es-Suyyagh is determined by the ceramic and numismatic finds to around the middle of the 7th century. This is supported by historical accounts on 7th century earthquakes, which report considerable damage in Judaea by earthquakes that are dated to 631/2 CE and 659 CE (Amiran, Arieh and Turcotte 1994; Guidoboni 1994:355-358; and see Chapter 10). These reports need to be examined in detail and cross-checked in further studies.

The most likely source of earthquakes in this region is the Dead Sea fault, an active boundary between the Sinai and the Arabia tectonic plates. The plates’ relative movements of average 4-5 mm/yr trigger occasional strong earthquakes. The earthquakes are recognized in numerous damaged archaeological sites throughout the Middle East as well as in deformed rock units (e.g., Amit et al. 2002; Kagan et al. 2005; Marco and Agnon 2005; Marco et al. 2005) The nearest segment of this fault is in the Jordan valley, some 50 km east of the site, which ruptured in the earthquakes of 31 BCE, 363 CE, 749 CE, and 1033 CE (Marco et al. 2003).

In conclusion, it is highly likely that the observed damage and subsequent repairs in Khirbet es-Suyyagh were caused by one or more earthquakes.

The Gatehouse

The destruction caused to the monastery by the earthquake that marked the end of Phase IIA is very apparent in the area of the main gate. The massive threshold was broken into two large pieces (see Chapter 9). The remains which point to the architectural changes that took place here during Phase IIB are:

- The western part of the monastery’s southern wall, which included the main gate, is not built exactly on the same line as the rest of the wall. In addition, the level of the main gate’s threshold itself is 0.5-0.6 m higher than that of the path which leads to it from the south. This height difference did not, of course, allow comfortable passage from the path into the monastery

- The western edge of the gate ended without being connected to any of the other nearby walls, e.g., those of the church complex (Fig. 2.15). Actually, only a thin wall (W218; whose first course is built of three small coarsely-carved stones) abutted on it from the south and connected it to the church’s apse, while creating a small trapezoidal room (Room 33; 2.3-3.3×2.2 m)

- The path and the entrance corridor to its north was found covered with a fill rich in pottery sherds and other finds.

Wall W33

Another alteration identified in this area is the rebuilding of the last 10 m of the southern end of W33. This section of the wall, excluding maybe the foundation course, was completely destroyed and rebuilt in a different manner than was usually common at the site. The rebuilt part, which was 0.4 m wider than the original wall, was made of small and medium-sized fieldstones bound with mortar. Theoretically, it seems that the southern end of W33 was destroyed during the earthquake that hit other parts of the monastery at the end of Phase IIA. However, we cannot say if the renovation of the damaged section occurred during Phase IIB or only in Phase III.

Subsidiary Gate and Central Courtyard

The original arrangement of the courtyard was changed, probably due to the earthquake that struck the monastery at the end of Phase IIA. The walls of the entrance room or corridor were demolished down to their foundation course. The floor of this room/corridor, which was lower than those of the courtyards themselves, was raised to create a uniform-level platform in which were embedded the remains of the entrance room.

The storerooms in the Western Unit

The construction of this storeroom can be attributed to Phase IIA, and it probably collapsed in the earthquake that ended this phase.

Damage Descriptions for entire site (some repetitive)

- from Taxel et al (2009)

The area of the large courtyard (Fig. 2.1:8-10) had been completely rebuilt after a destructive event. An earlier construction phase, which is observed south of the centre of the courtyard (Fig. 2.1:9), is covered by a later floor. Fallen masonry and subsequent repairs were observed in the southern part of the apse of the church, with its inner face remaining asymmetric. Since the damage is observed close to the foundations of the church it seems that the damage had a pervasive affect on the entire structure. A section of about 10 m in the southern end of W33 seems also to have been rebuilt. Similarly, in W100 there is a warped contact in room 19, where two different styles of masonry meet but are misaligned.

Another type of damage appears in two broken door thresholds, that of the main gate and that of the small courtyard in the south of the monastery. The large, monolithic and nicely carved stones are placed in-situ but broken by a width wise crack into two pieces. Assuming the thresholds were carved from intact rocks without significant fractures, we can envision strong vertical acceleration, perhaps of the order of 1 g, which caused the fracturing. Such strong shaking is known based on modern earthquakes to occur either near the epicentre of strong earthquakes (of the order of magnitude 7 and above) or in places with strong local amplification of seismic waves.

Each of the damaged elements alone would not suffice to indicate an earthquake as the damaging agent. However, the occurrence of many such elements, the extensive repair and reconstruction of features without any sign of human violence and in short time, together with the frequent occurrence of earthquakes in the region supports the association of the damage to earthquake/s.

End of Phase IIA Earthquake(s) - 7th century CE

| Effects | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Subsidiary Gate and The Large Central Courtyard

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

Apse of the Church

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.57

Fig. 2.57Plan of the church complex. Taxel et al (2009) |

Fig. 2.58

Fig. 2.58The church (30): Above) looking north Below) Section C-C (see Fig. 2.57) through church, looking west. JW: Note asymmetric apse Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.62

Fig. 2.62the southern (repaired) wall of the apse (W223), looking northwest. Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

Main Gate

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery. JW: Broken threshold is in Square D/5 to the lower left. Note elevation differences Taxel et al (2009) |

Fig. 2.24

Fig. 2.24the threshold of Courtyard 2, looking west. Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

Gatehouse

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery. Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

Southern end of Wall W33

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery. JW: Rebuilt part of wall W33 is on the far right in Squares E/5-6 Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

Wall W100 in Room 19

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II JW: Room 19 is in the middle (Squares D/6-7) and though Wall W100 is not labeled, it appears to be the warped southwestern wall of Room 19 . Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

Storerooms in the Western Unit

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

northern doorway of the tower

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.31

Fig. 2.31Plan of the tower. Taxel et al (2009) |

Fig. 2.32

Fig. 2.32the northern doorway of the tower, looking east. JW: Fracture may be due to soil creep along slope to the left Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

various locations

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery. JW: wall W131 is in Squares E/5-6 Taxel et al (2009) |

Fig. 2.84

Fig. 2.84Crushed storage jar and a lid between W131 and W147. Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.34

Fig. 2.34Crushed storage jars in the northeastern corner of the basement (L148). Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.27

Fig. 2.27Crushed pottery on the floor of room 5 (L260). Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

central wall of the apse (W223)

Fig. 2.57

Fig. 2.57Plan of the church complex. JW: Wall W223 is in Square D/4 Taxel et al (2009) |

Fig. 2.63

Fig. 2.63A lintel reused in the central wall of the apse (W223). Taxel et al (2009) |

|

End of Phase IIA Earthquake(s) - 7th century CE

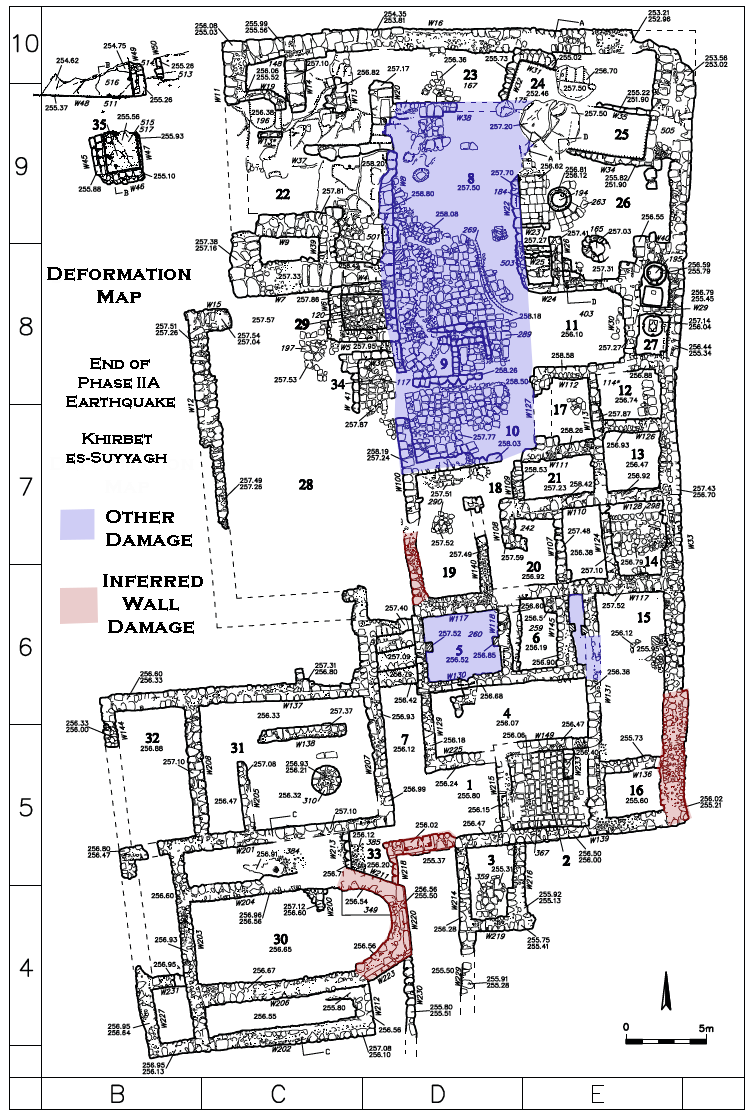

- Modified by JW from Fig. 2.1 of Taxel et al (2009)

- Other Damage is either crushed pottery or inferred damage due to a rebuild of the large central courtyard

Deformation Map

Deformation MapInferred Wall Damage is largely based on rebuilding evidence along with limited collapse evidence. Other Damage is either broken pottery found on floors or a significant rebuild to the large central courtyard.

modified by JW from Fig. 2.1 (Phase I and II plan) of Taxel et al (2009)

End of Phase IIA Earthquake(s) - 7th century CE

Intensity Estimate from Earthquake Archaeological Effects (EAE) Chart

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effects | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Subsidiary Gate and The Large Central Courtyard

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

Apse of the Church

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.57

Fig. 2.57Plan of the church complex. Taxel et al (2009) |

Fig. 2.58

Fig. 2.58The church (30): Above) looking north Below) Section C-C (see Fig. 2.57) through church, looking west. JW: Note asymmetric apse Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.62

Fig. 2.62the southern (repaired) wall of the apse (W223), looking northwest. Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

Main Gate

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery. JW: Broken threshold is in Square D/5 to the lower left. Note elevation differences Taxel et al (2009) |

Fig. 2.24

Fig. 2.24the threshold of Courtyard 2, looking west. Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

Gatehouse

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery. Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

Southern end of Wall W33

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15Plan of the gatehouse complex and the southern area of the monastery. JW: Rebuilt part of wall W33 is on the far right in Squares E/5-6 Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

Wall W100 in Room 19

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II JW: Room 19 is in the middle (Squares D/6-7) and though Wall W100 is not labeled, it appears to be the warped southwestern wall of Room 19 . Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

Storerooms in the Western Unit

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

northern doorway of the tower

Fig. 2.1

Fig. 2.1Plan of Phase I and Phase II . Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.15

Fig. 2.15General reconstruction of the monastery, looking northwest Drawing by Yura Smertenko Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.31

Fig. 2.31Plan of the tower. Taxel et al (2009) |

Fig. 2.32

Fig. 2.32the northern doorway of the tower, looking east. JW: Fracture may be due to soil creep along slope to the left Taxel et al (2009) |

|

|

Intensity Estimate from Taxel et. al. (2009)

Figures

- Fig. 2.24 - Broken Threshold of Courtyard 2

from Taxel et al (2009)

Fig. 2.24

Fig. 2.24

the threshold of Courtyard 2, looking west.

Taxel et al (2009) - Fig. 2.24 - Deformation Map -

created by Jefferson Williams using a plan from Taxel et al (2009)

Deformation Map

Deformation Map

Inferred Wall Damage is largely based on rebuilding evidence along with limited collapse evidence. Other Damage is either broken pottery found on floors or a significant rebuild to the large central courtyard.

modified by JW from Fig. 2.1 (Phase I and II plan) of Taxel et al (2009)

Schmuel Marco in Taxel et al (2009:186-187) suggested that seismic intensity may have reached IX (1 g) apparently largely based on the broken threshold of the Main Gate (shown in Fig. 2.24 above and not necessarily fractured in an earthquake) and rebuilding evidence which inferred wall collapses down to the foundations. Archaeoseismic evidence at the Monastery of Euthymius as reported by Hirschfeld (1993) showed evidence for a near total rebuild after it was presumably destroyed in one of the Jordan Valley Quake(s) of 659/660 CE. Although direct archaeoseismic evidence was not observed at the Monastery of Euthymius, the contemporary Maronite Chronicle reported that the Monastery of Euthymius collapsed during this earthquake - which supports the idea that a near total rebuild supports such a high level of local seismic intensity. However, the Monastery of Euthymius is closer to active Jordan Valley faults that seem to have broken during the Jordan Valley Quake(s) which means that Khirbet es-Suyyagh, further away from these faults, would have likely experienced lower levels of intensity during this event(s). This would explain why there were repairs at Khirbet es-Suyyagh rather than a complete rebuild. Given the distance between Khirbet es-Suyyagh and the active faults of Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea, Schmuel Marco in Taxel et al (2009:186-187) suggested that such an elevated intensity estimate (guesstimate ?) of IX (1 g) could be explained by a site effect or being above the hypocenter when the Quake struck (e..g in a blind thrust scenario). While a site effect is possible as it is described as being located on a spur, the Deformation Map (see in Figures above) suggests that North-South walls were preferentially damaged which is not what one would suspect above a hypocenter where inclination and collapse typically do not display directional patterns. Such directional patterns, which seem to be evident at Khirbet es-Suyyagh, are what one would expect at some distance form the epicenter (e.g. see Korzhenkov and Mazor, 1999).

References