Monastery of Euthymius

Annotated Aerial View of Euthymius Monastery

Annotated Aerial View of Euthymius Monastery

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com

| Transliterated Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Monastery of Euthymius | English | |

| Laura of Euthymius | English | |

| Lavra of Euthymius | English | |

| Khan el-Ahmar | Arabic |

Euthymius' Monastery (Khan el-Ahmar) is located in the industrial zone of Mishor Adummim, about 10 km (6 mi.) east of Jerusalem (map reference 1819.1333). Cyril of Scythopolis (Beth-Shean), the biographer of Euthymius, provides an exact topographical description of the monastery. It was located, according to him, on a small hill surrounded on the east and west by two especially beautiful valleys that meet and converge on the south side.

The Monastery of Saint Euthymius was founded in 428 as a laura (q.v. Monasteries). This laura was unique in its status and central location, and the number of its monks quickly rose to fifty. According to Cyril's description, a garden containing a reservoir was planted next to the laura's church and the bakery. In accordance with Saint Euthymius' will, the monastery was reestablished as a cenobium , containing a church and a refectory, as well as a tower, and surrounded by a wall. The cenobium was dedicated in 482 CE.

Twenty years after the Arab conquest of Palestine, in the summer of 659, the monastery was severely damaged by an earthquake that also destroyed Jericho and the monastery of Saint John the Baptist overlooking the Jordan River [JW: this refers to the Jordan Valley Quake(s)]. Most of the remains visible at the site today belong to the repairs of the earthquake damages carried out by the monks in the late seventh or early eighth century CE. In the early ninth century, the monastery was attacked by desert nomads, the Saracens, but continued to exist. The tombs of Euthymius and of other holy fathers are mentioned in the work of a Russian pilgrim, Abbot Daniel, in 1107 (PPTS IV, 3, 35-36). In the twelfth century, extensive restoration and construction works were carried out in the monastery, including the repaving of the church, the building of a chapel over the tomb of Euthymius, and he construction of additional rooms and halls. The restored monastery is described in the work of Johannes Phocas, a pilgrim who visited the monastery in 1185 (PPTS V, 3, 25). The site was abandoned in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century and presumably became a caravanserai serving Muslim pilgrims going up to Jerusalem from the traditional tomb of Moses, Nebi Musa, in the Hyrcania Valley east of the monastery.

Summarizing the history of the monastery of Euthymius, four main dates of construction are clear:

- 428: dedication of the laura church. Solitary cells, a bakery, a water cistern with a double opening, and a garden were founded alongside the church. From this date on, the laura expanded and the number of its monks reached fifty. In the year of Euthymius' death (473) the original seclusion cave was transformed into a vaulted underground tomb.

- 482: reconstruction of the monastery as a walled coenobium. The grave of Euthymius remained at the center of the monastery. The Old Laura church was demolished and in its stead a refectory was built with a new church over it. A large water reservoir was excavated alongside the monastery, surrounded by walled farming plots. A tower and gatehouse indicated the boundaries of the monastery's estates. Two hostels, one in Jerusalem and the other in Jericho, were owned by the monastery.

- 659: severe damage was caused by an earthquake. In the wake of the damage, most of the monastery's components were rebuilt, except for the underground tomb which survived from the Byzantine period.

- About 1150: large-scale restoration and construction of the monastery. The central church was paved, a chapel was built over the grave of Euthymius, as well as a new refectory and rooms; the wall was restored.

TThe Monastery of Saint Euthymius was the first monastery in the Judean Desert in which archaeological excavations were conducted. It was excavated from 1927 to 1930 by D. Chitty, on behalf of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. Chitty concentrated on uncovering the church and the structure of the adjoining crypt. In the 1970s, Y. Meimaris excavated here, extending the previously excavated areas. In 1987, excavations were resumed by Y. Hirschfeld and R. Birger-Calderon, on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The monastery's successive stages were uncovered and the tower structure in its north wing was partially excavated.

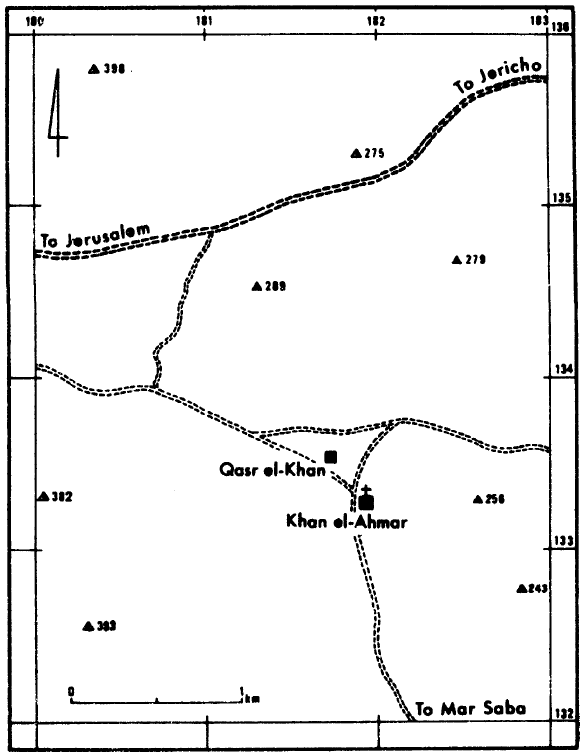

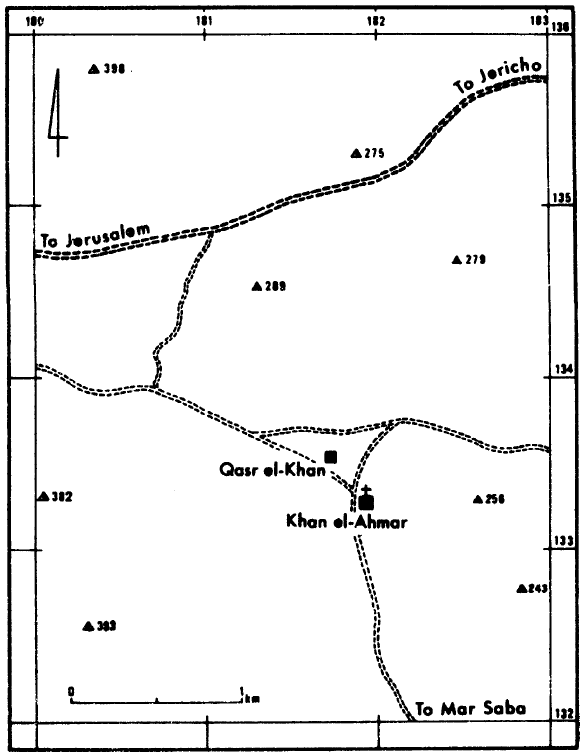

- Fig. 3 - Location Map from

Hirschfeld (1993)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Satellite monasteries around the monastery of Euthymius

Hirschfeld (1993) - Fig. 4 - Location Map from

Hirschfeld (1993)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

The monastery and it's surroundings

Hirschfeld (1993)

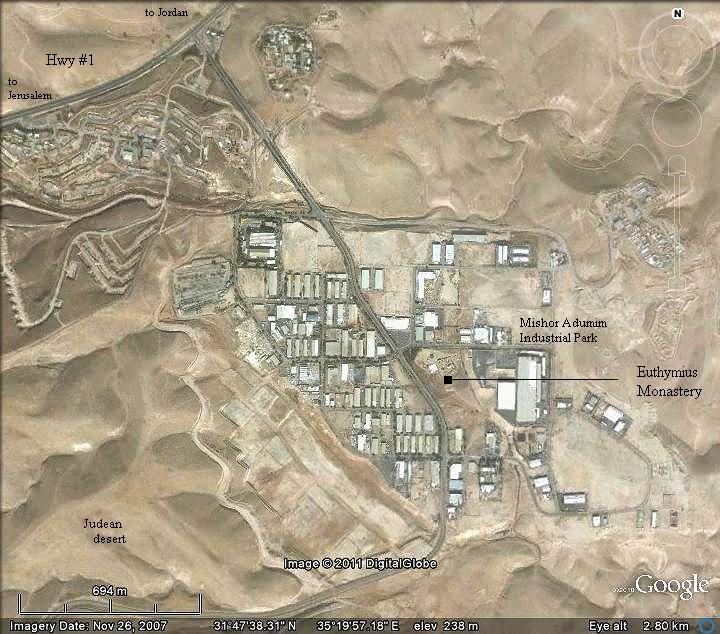

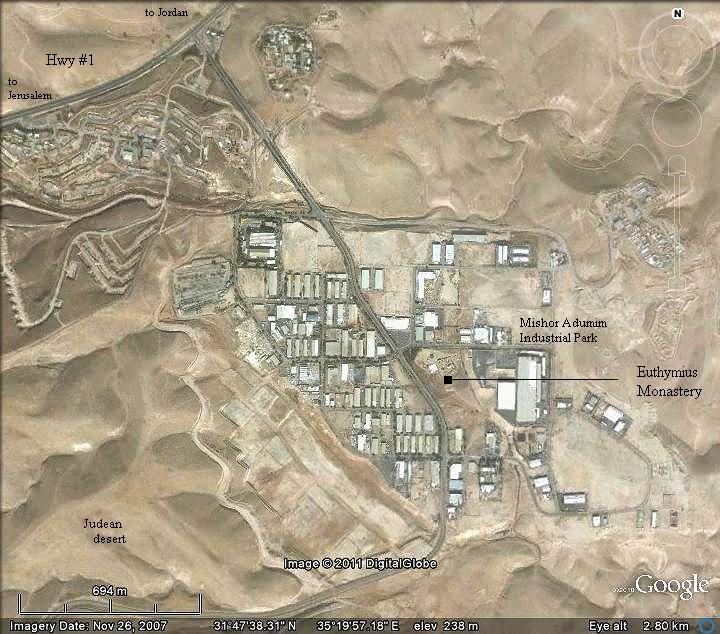

- Annotated Satellite Image of

the area around Euthymius Monastery from BibleWalks.com

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of the area around Euthymius Monastery

Annotated Satellite Image (google) of the area around Euthymius Monastery

Used with permission from BibleWalks.com - Annotated Aerial View of

Euthymius Monastery from BibleWalks.com

- Monastery of Euthymius in Google Earth

- Monastery of Euthymius on govmap.gov.il

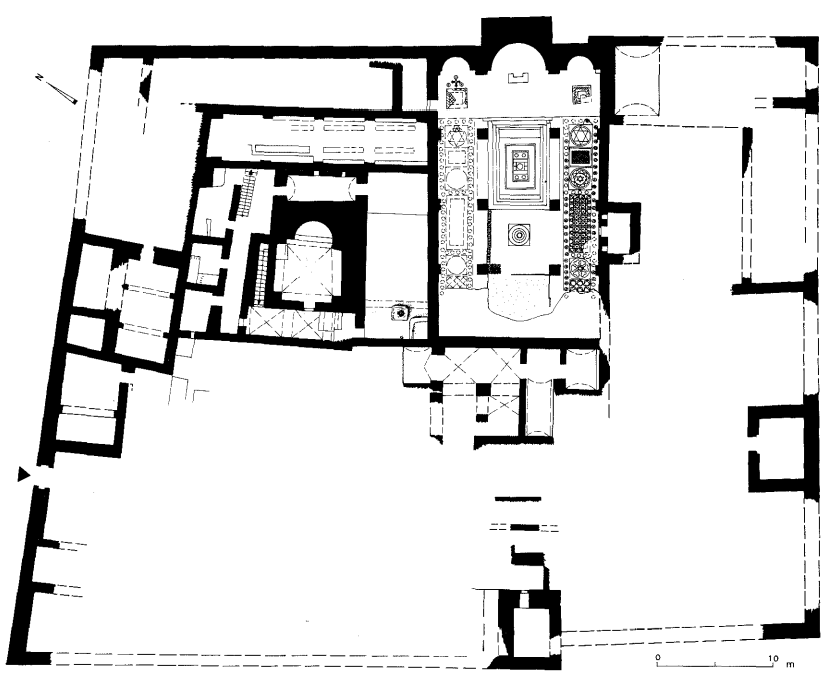

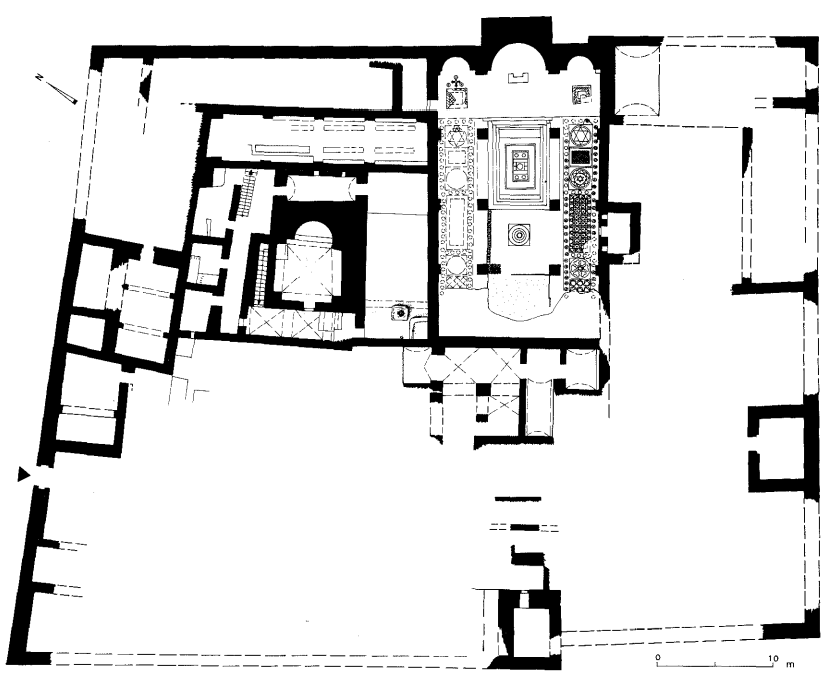

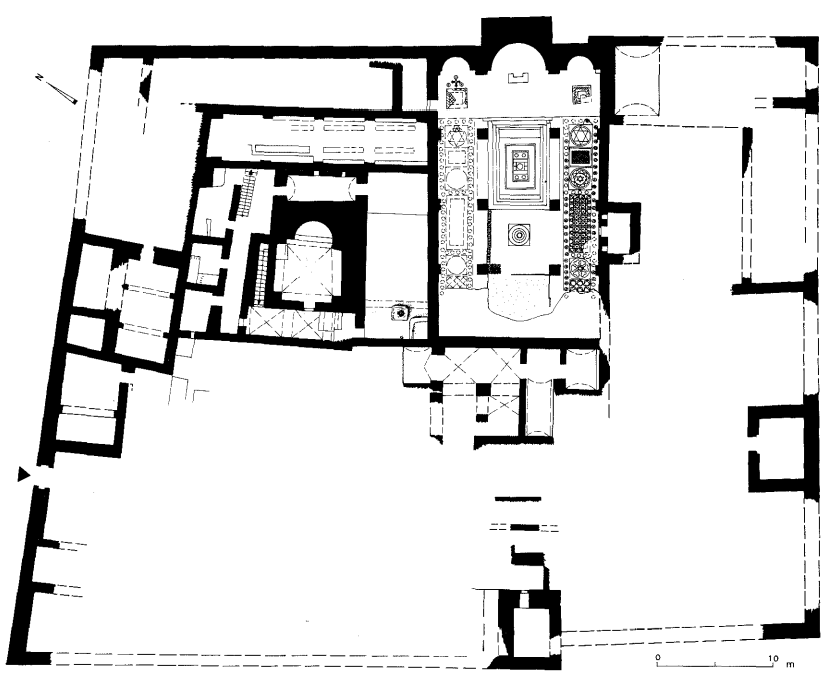

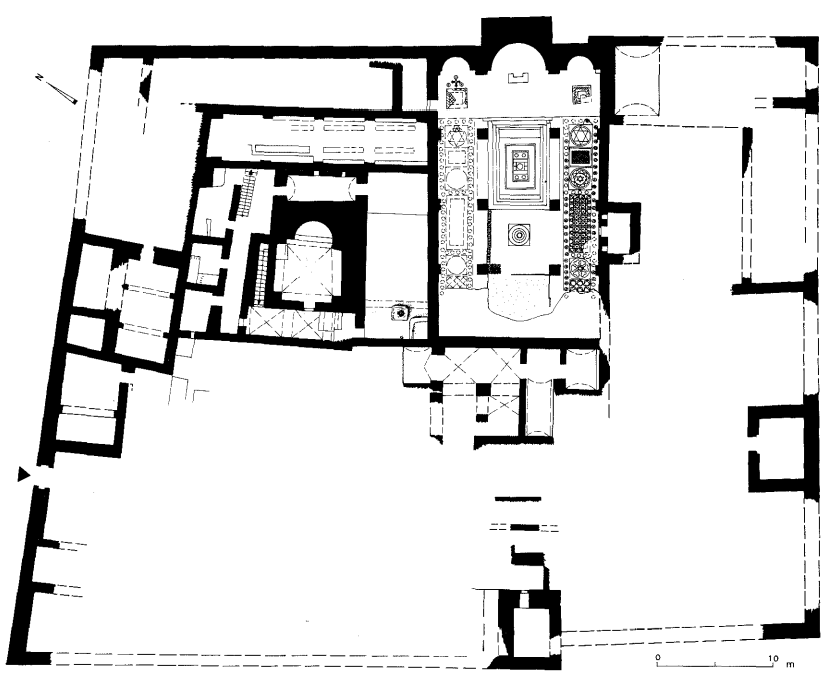

- Fig. 5 - General plan of the site

from Hirschfeld (1993)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

The monastery of Euthymius, general plan of the site.

Hirschfeld (1993) - Plan of Euthymius Monastery

from BibleWalks.com

- Plan of Euthymius Monastery

from Stern et al (1993)

Plan of Euthymius Monastery

Plan of Euthymius Monastery

Stern et al (1993) - Fig. 6 - Sketch plan of the monastery

from Hirschfeld (1993)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

The monastery of Euthymius, sketch plan.

Hirschfeld (1993) - Fig. 7 - Detailed plan of the church

of the monastery from Hirschfeld (1993)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

The church of the monastery, detailed plan

Hirschfeld (1993)

- Fig. 5 - General plan of the site

from Hirschfeld (1993)

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

The monastery of Euthymius, general plan of the site.

Hirschfeld (1993) - Plan of Euthymius Monastery

from BibleWalks.com

- Plan of Euthymius Monastery

from Stern et al (1993)

Plan of Euthymius Monastery

Plan of Euthymius Monastery

Stern et al (1993) - Fig. 6 - Sketch plan of the monastery

from Hirschfeld (1993)

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

The monastery of Euthymius, sketch plan.

Hirschfeld (1993) - Fig. 7 - Detailed plan of the church

of the monastery from Hirschfeld (1993)

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

The church of the monastery, detailed plan

Hirschfeld (1993)

The Maronite Chronicle lists three earthquakes

- The first earthquake occurred in the second hour (~8 am) on a Friday in June 659 CE and was described as

a violent earthquake in Palestine

where many places collapsed. - A second earthquake is described as occurring in the 8th hour (~2 pm) on Sunday 9 June 659 CE. No details about location or seismic effects were given.

- The third earthquake suffers from some chronological inconsistencies and, unlike the first two earthquakes, does not specify details such as hour, day of the week, and date.

It appears to have taken place in 660 CE but may be a false event which copied in seismic effects from one or both of the the first two earthquakes.

It was described as

an earthquake and a violent tremor

wherethe greater part of Jericho fell, including all its churches

, theHouse of Lord John at the site of our Saviour’s baptism in the Jordan

was overthrown, andthe monastery of Abba Euthymius as well as many convents of monks and solitaries and many other places also collapsed

.

Hirschfeld (1993:354) reported on the results of excavations at the Monastery of Euthymius. He dated seismic destruction based on reconstruction evidence and the report of its destruction in the Maronite Chronicle (see Textual Evidence section).

The severity of the destruction in the monastery of Euthymius may be deduced from the results of the excavations. During our excavation at the site, it became clear that most of the monastery – except for the crypt, whose vaults remained intact, and another vault which survived at the north end of the church – was rebuilt after the earthquake of 659. At this stage, the basilical church was reconstructed over the vaults; the latter are not Byzantine, as Chitty suggests, but early Muslim.39 The floor of the church was decorated with fine mosaic patterns. These have also been dated, on the basis of their style, to the early Muslim period, i.e., following the earthquake of 659. Reconstruction of the monastery probably took place not long after the earthquake, in the second half of the 7th century.Footnotes39. Chitty seems to have dated the church to 482, even before beginning the excavation, see: Chitty and Jones, “The Church” (above, note 1), pp. 175-176. This was done despite the fact that the mosaics of the church were dated by the Dominican archaeologist Père Savignac to the 7th-8th centuries (ibid.). The early dating of the church was reiterated by Chitty later, see: Chitty, “The Monastery” (above note 1), p. 194

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Monastery of Abba Euthymius |

In A.G. 971, Constans’s 18th year, many Arabs gathered at Jerusalem and made Mu'awiya king141 and he went up and sat down on Golgotha; he prayed there, and went to Gethsemane and went down to the tomb of the blessed Mary to pray in it. In those days, when the Arabs were assembled there with Mu'awiya, there was an earthquake and a violent tremor and the greater part of Jericho fell, including all its churches, and of the House of Lord John at the site of our Saviour’s baptism in the Jordan every stone above the ground was overthrown, together with the entire monastery. The monastery of Abba Euthymius as well as many convents of monks and solitaries and many other places also collapsed in this (earthquake).- Maronite Chronicle |

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Structures | Most of the monastery |

The severity of the destruction in the monastery of Euthymius may be deduced from the results of the excavations. During our excavation at the site, it became clear that most of the monastery – except for the crypt, whose vaults remained intact, and another vault which survived at the north end of the church – was rebuilt after the earthquake of 659.- Hirschfeld (1993:354) |

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Walls | Monastery of Abba Euthymius |

In A.G. 971, Constans’s 18th year, many Arabs gathered at Jerusalem and made Mu'awiya king141 and he went up and sat down on Golgotha; he prayed there, and went to Gethsemane and went down to the tomb of the blessed Mary to pray in it. In those days, when the Arabs were assembled there with Mu'awiya, there was an earthquake and a violent tremor and the greater part of Jericho fell, including all its churches, and of the House of Lord John at the site of our Saviour’s baptism in the Jordan every stone above the ground was overthrown, together with the entire monastery. The monastery of Abba Euthymius as well as many convents of monks and solitaries and many other places also collapsed in this (earthquake).- Maronite Chronicle |

VIII+ |

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collapsed Structures including walls | Most of the monastery |

The severity of the destruction in the monastery of Euthymius may be deduced from the results of the excavations. During our excavation at the site, it became clear that most of the monastery – except for the crypt, whose vaults remained intact, and another vault which survived at the north end of the church – was rebuilt after the earthquake of 659.- Hirschfeld (1993:354) |

VIII + |

Hirschfeld (1993:354) EUTHYMIUS AND HIS MONASTERY

IN THE JUDEAN DESERT Liber Annus 43 339-371 - open access at archive.org - also available at the wayback machine

Meimaris,Y. E. (1989) The Monastery of Saint Euthymios the Great at Khan el-Ahmar, in the

Wilderness of Judaea: Rescue Excavations and Basic Protection Measures, 1976-1979, Preliminary

Report, Athens 1989.

Y. E. Meimaris, The Monastery of Saint Euthymios the Great at Khan el-Ahmar, in the

Wilderness of Judaea: Rescue Excavations and Basic Protection Measures, 1976-1979, Preliminary

Report, Athens 1989.

D. J. Chitty and A. H. M. Jones, PEQ 61 (1929), 98-102, 175-178; 62 (1930), 43-47, 150-

153; 64 (1932), 188-203

Y. Hirschfeld, ESI 3 (1984), 80; id., The Judean Desert Monasteries in the

Byzantine Period, New Haven (in prep.)

R. Birger and Y. Hirschfeld, ESI7-8 (1988-1989), 110

Y. E. Meimaris (Review), LA 40 (1990), 524-526.

Y. Hirschfeld, The Judean Desert Monasteries in the Byzantine Period, New Haven CT 1992; id., LA 43

(1993), 339–371

V. Eshed, Paleoanthropological Research on Four Byzantine Populations (M.A. thesis),

Tel Aviv 1993

I. Hershkovitz (et al.), LA 43 (1993), 373–385; id. (& R. Yakar), International Journal of

Osteoarchaeology 5 (1995), 61–77

J. Patrich, Abas, Leader of Palestinian Monasticism: A Comparative

Study in Eastern Monasticism, 4th to 7th Centuries (Dumbarton Oaks Studies 32), Washington, D.C. 1995,

162–163

H. Goldfus, Tombs and Burials in Churches and Monasteries of Byzantine Palestine (324–628

A.D.), 1–2 (Ph.D. diss.), Ann Arbor, MI 1998, 176–205

S. Santelli et al., Les Dossiers d’Archéologie 240

(1999), 86–87

F. Mébarki, MdB 131 (2000), 60

L. Di Segni, The Sabaite Heritage in the Orthodox Church

from the 5th Century to the Present (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 98; ed. J. Patrich), Leuven 2001, 31–36

P. Donceel-Voûte, La mosaïque gréco-romaine 9: Actes du 9. Colloque International pour l’Étude de la

Mosaïque Antique et Médiévale, Roma, 5–10.11.2001, Paris 2002, 151–170.