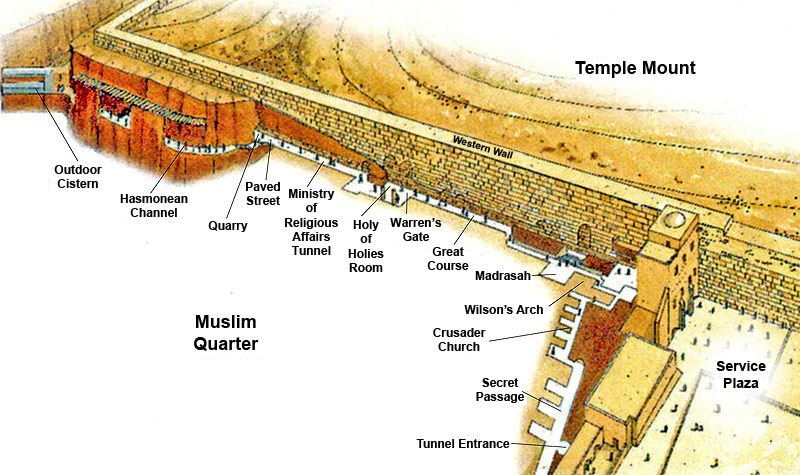

Jerusalem - Western Wall Tunnel

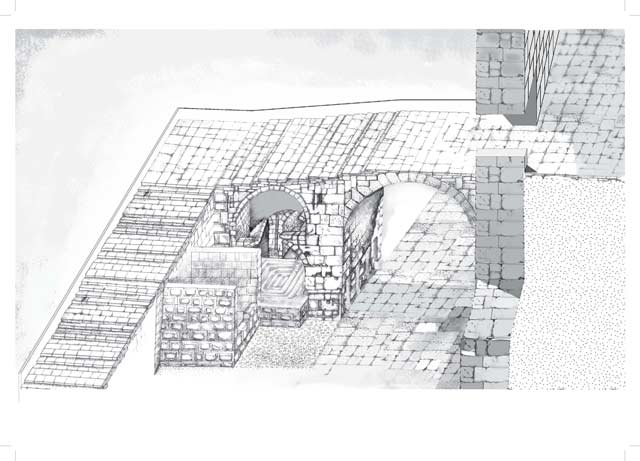

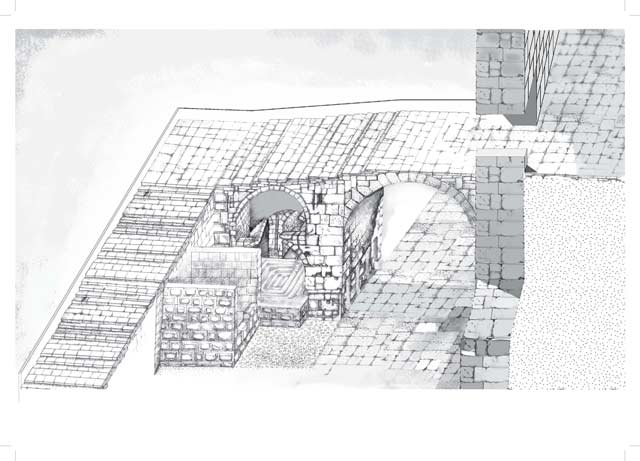

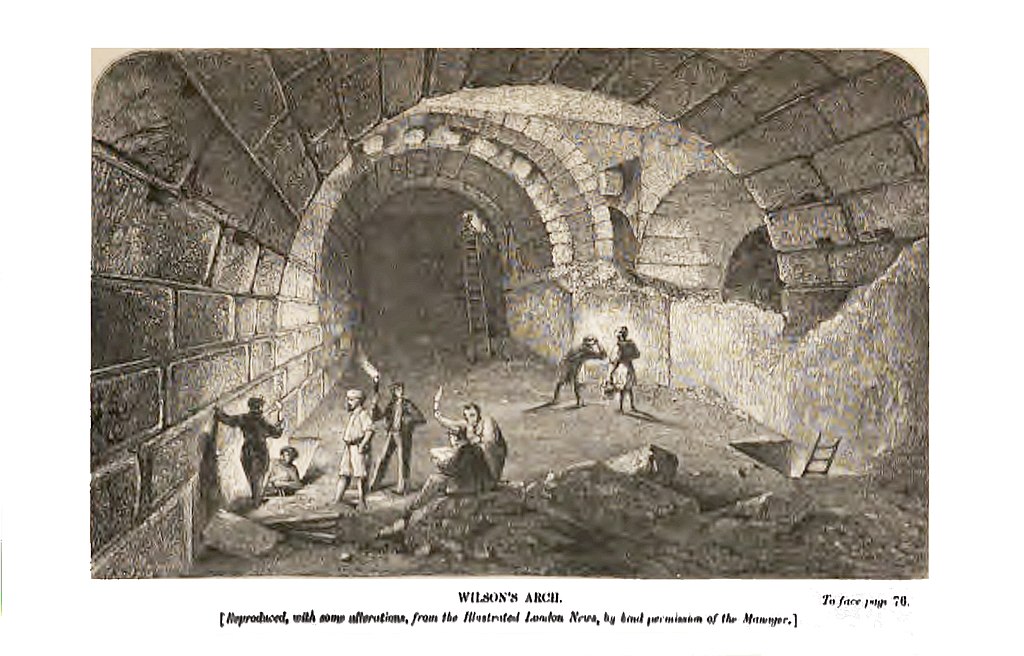

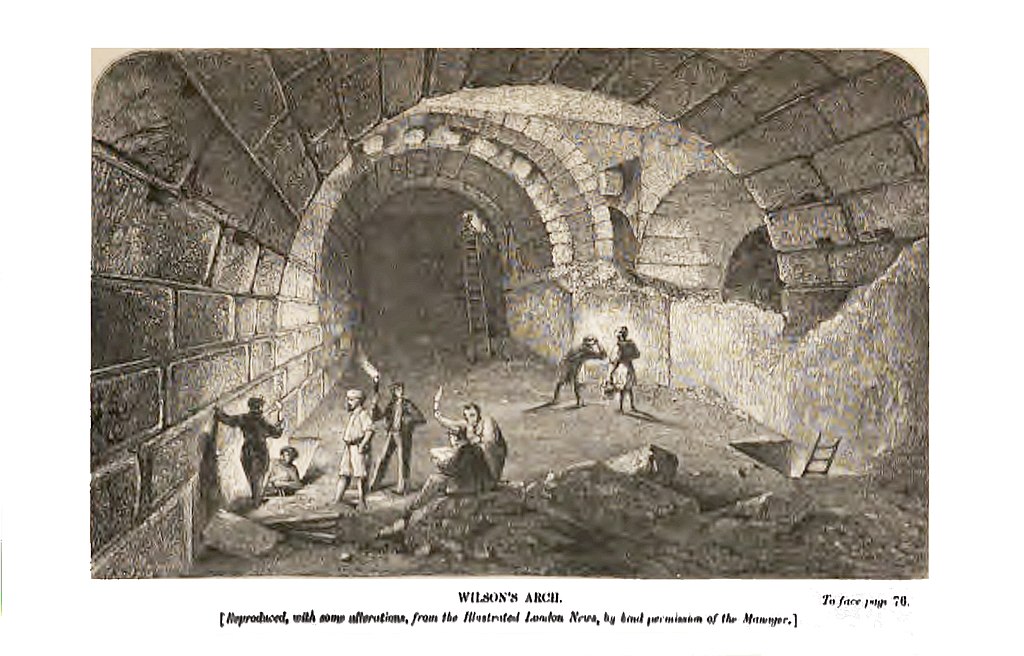

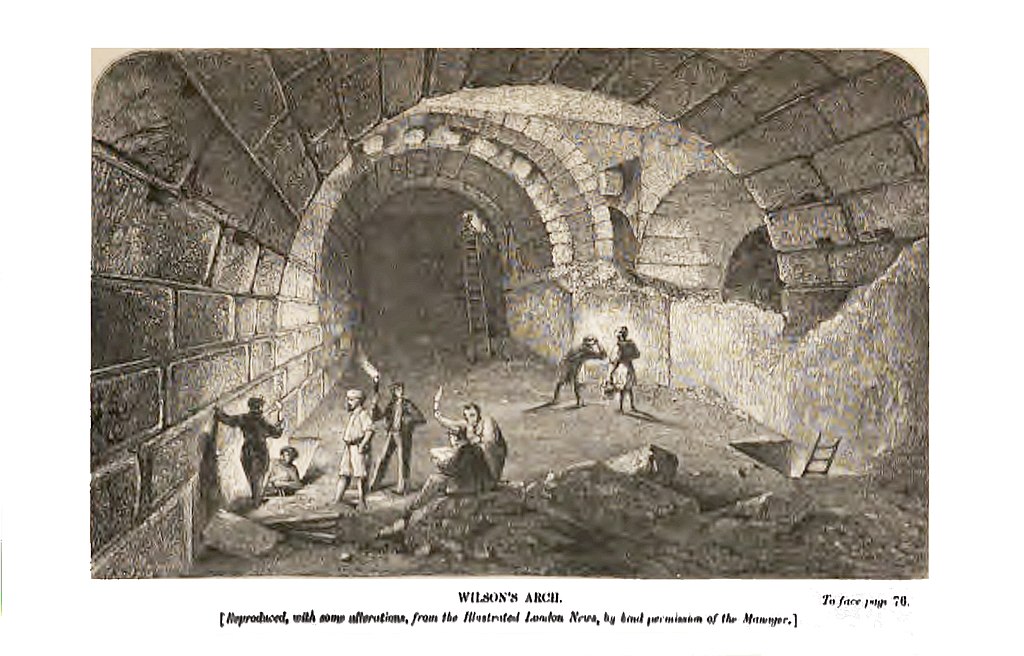

Section of Wilson's Arch

Section of Wilson's ArchClick on image to open a high res magnifiable image in a new tab

Wilson (1871)

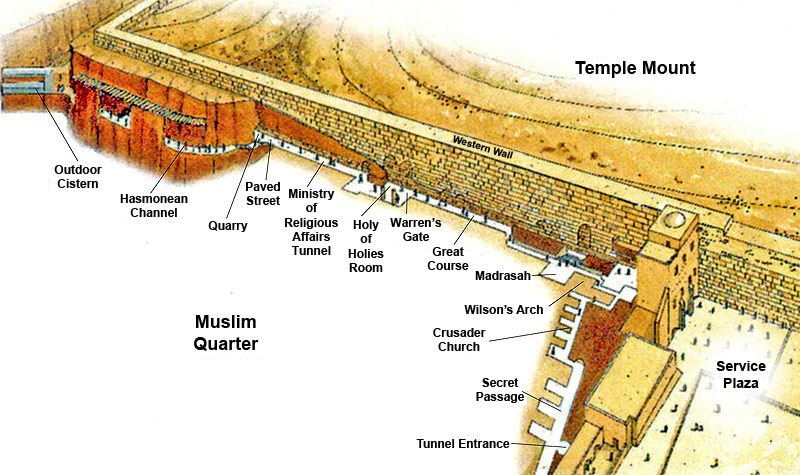

The Herodian Temple Mount enclosure was the most prominent architectural feature in Jerusalem at the end of the Second Temple period. Described in detail by Josephus, it was destroyed at the end of the first Jewish-Roman War in 70 AD. Although the Temple is gone, the large retaining walls still stand. Adjacent to the western retaining wall (Kotel (כותל) in Hebrew), excavations have been ongoing in the tunnels north of the Western Wall Plaza - the holiest side in Judaism.

- from Onn et. al. (2011)

During the twentieth century, several small-scale excavations were conducted north and south of the Great Causeway, as well as below it. Most of these excavations were related to repairs of the municipal drainage system, extending along the main roads that cross the area: Ha-Gāy Street (El-Wad) and the Street of the Chain. R.W. Hamilton and C. Jones excavated on Ha-Gāy Street, next to where the street passes beneath the vaults of the Great Causeway; they exposed the pavement of a street that has been identified with the eastern Roman–Byzantine cardo (Hamilton R.W. 1932. Street Levels in Tyropoeon Valley. QDAP 1:105–110; Hamilton R.W. 1933. Street Levels in Tyropoeon Valley, II. QDAP 2:34–40; Johns C.N. 1932. Jerusalem: Ancient Street Levels in the Tyropoeon Valley within the Walls. QDAP 1:97–100). Other remains of the eastern Roman–Byzantine cardo were recently discovered in Ohel Yizhaq and in the Western Wall Plaza, north and south of the Great Causeway (Barbe H. H. and De‘adle T. 2006. Jerusalem—Ohel Yizhaq. In E. Baruch, Z. Greenhut and A. Faust (eds.) New Studies on Jerusalem 11:19*– 29*; HA-ESI 121; Weksler-Bdolah S., Onn A. and Rosenthal-Heginbottom R. 2009. The Eastern Cardo and Wilson’s Arch in Light of the New Excavations: The Remains from the Second Temple Period and the Roman Period. In L. Di Segni, Y. Hirschfeld, R. Talgam and Y. Patrich (eds.). Man Near a Roman Arch. Studies Presented to Professor Yoram Tsafrir. Jerusalem, pp. 135–159; Weksler-Bdolah S. and Onn A. 2010. Remains of the Eastern Roman Cardo in the Western Wall Plaza. Qadmoniot 140:123–132 [Hebrew]). Street remains paved with flagstones that date to the Roman period were exposed on the Street of the Chain, above the top of the Great Causeway, (ESI 10:134–136; ESI 16:104–106). The street has been identified with the decumanus from the time of Aelia Capitolina (Tsafrir Y. 1999. The Topography and Archaeology of Aelia Capitolina. In Y. Tsafrir and S. Safrai [eds.]. The Jerusalem Book, The Roman and Byzantine Period 70–638 CE, p. 146 [Hebrew]; Kloner A. 2006. Dating the Southern Lateral Street [the Southern Decumanus] of Aelia Capitolina and Wilson’s Arch. New Studies on Jerusalem 11:239–247 [Hebrew]). Part of a monumental staircase from the Second Temple period was exposed above the top of Wilson’s Arch and above its western pier (ESI 16:104–106).

- from Onn et. al. (2011)

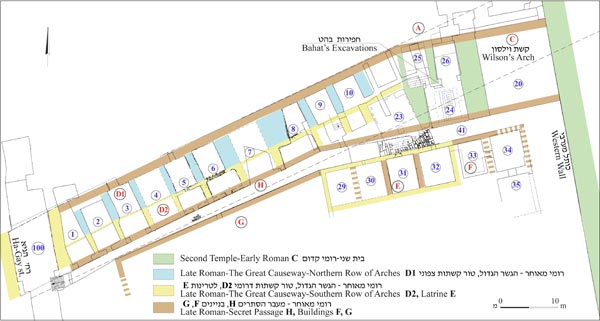

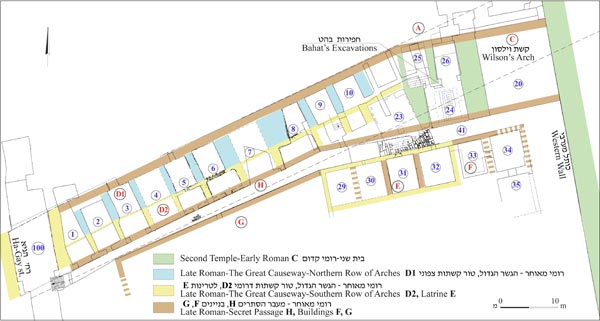

The length of the Great Causeway, extending between Ha-Gāy Street in the west and the western wall of the Temple Mount in the east, is c. 100 m; its overall width is 10.8–11.0 m and it passes above the Tyropoeon Valley, next to the confluence with the Transverse Valley (Nahal Ha-‘Arev). Today, the Street of the Chain, leading to the Chain Gate of the Temple Mount, is borne atop the causeway. The Great Causeway is composed of several units that were built in different time periods; these units are referred to below by the letters: A, B, C, D1 and D2 (Figs. 2, 3). The beginning of the causeway in the east is the monumental Wilson’s Arch (below: C), which is supported up against the western wall of the Temple Mount. Extending westward, the Great Causeway consists of two rows of narrower arches, or vaults: a northern row (D1) and a southern row (D2), which are adjacent to each other and founded atop buildings that date to the Second Temple period (Fig. 3). The northern (D1) and southern (D2) rows of arches are quite similar in their overall appearance; however, a significant discrepancy along their contact line, and the variable width and height of adjacent vaults indicate that they were built at different times (Fig. 4). The walls enclosing the arches to the north and south were built during the Roman period and thus created enclosed spaces inside the archways. These enclosed spaces were numbered in ascending order from west to east (below, arch/vault or room No. 1, 2, 3 etc.). The arches in the eastern part of the Great Causeway were founded on a monumental building composed of three halls, which dated to the Second Temple period (below, Building B). The arches in its western part were founded on a massive foundation wall (max. width c. 14 m), which to the best of our knowledge today, also dates to the Second Temple period (below; W5006, Building A). Remains of the eastern Roman cardo, generally oriented north–south, were exposed beneath what is known today as the westernmost arch of the Great Causeway. Large buildings (below E, F, G) that were constructed in a later period south of the Great Causeway had survived by a narrow route (H) between them, known by the name of the ‘Secret Passage’.

The current excavations (2007–2010) were conducted in the northern part of Room 3 (Vault 304), Room 5 (Vaults 502, 504), Room 6 (Vaults 602, 604), the northern part of Room 8 (Vault 804), and in Room 21, located on a lower level beneath the southern part of Room 8 (Vault 802) and below the Secret Passage. A later blocking wall (W400) that had sealed off the entrance from the Secret Passage into Room 4 of the Great Causeway (Vault 402) was breached. In addition, a cistern that was installed inside the northern vault (Vault 404) of Vault 4 was partly cleaned. Furthermore, two areas were excavated along the Secret Passage (Onn A. and Solomon A. 2008. A Window to Aelia Capitolina in the Western Wall Tunnel Excavations, Innovations in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and its Surroundings 1: 85–93; Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Avni 2009; Weksler-Bdolah, Onn and Rosenthal-Heginbottom, 2009; Onn A. and Weksler-Bdolah S. 2011a. Wilson’s Arch in Light of New Excavations and Past Studies. In D. Amit, O. Peleg-Bareket and G.D. Steibel [eds.], Innovations in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and its Surroundings Wilson’s Arch and the Great Causeway in the Second Temple Period and in the Roman Period – In Light of New Excavations. Qadmoniot 140:109–122 [Hebrew]). 4:84–100 [Hebrew]; Onn A. and Weksler-Bdolah S. 2011b.

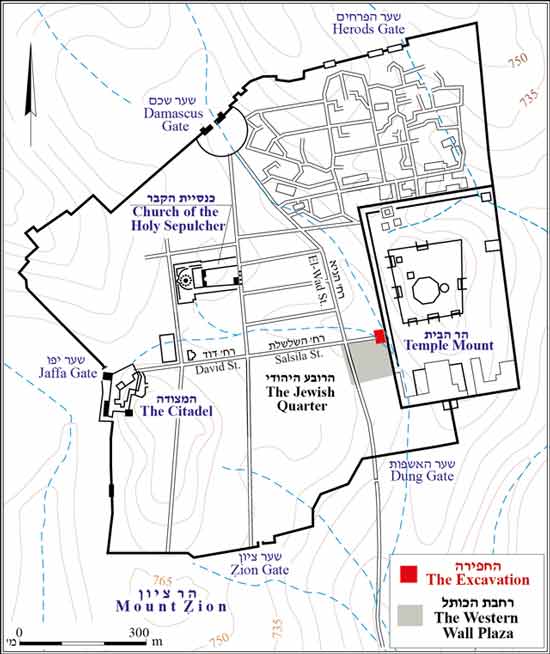

- from Jerusalem - Introduction - click link to open new tab

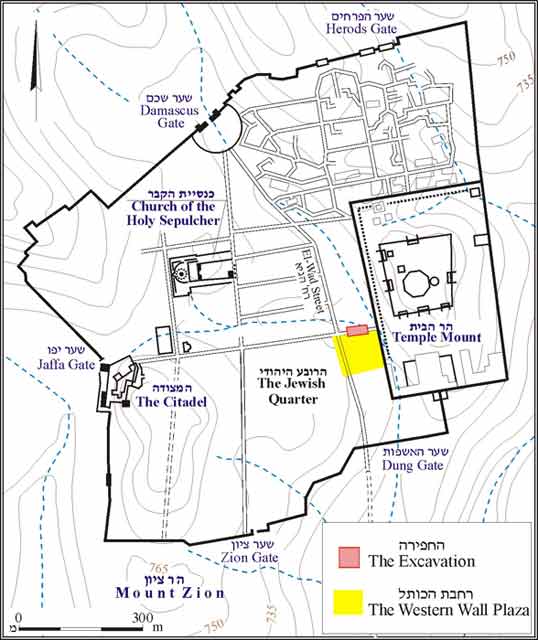

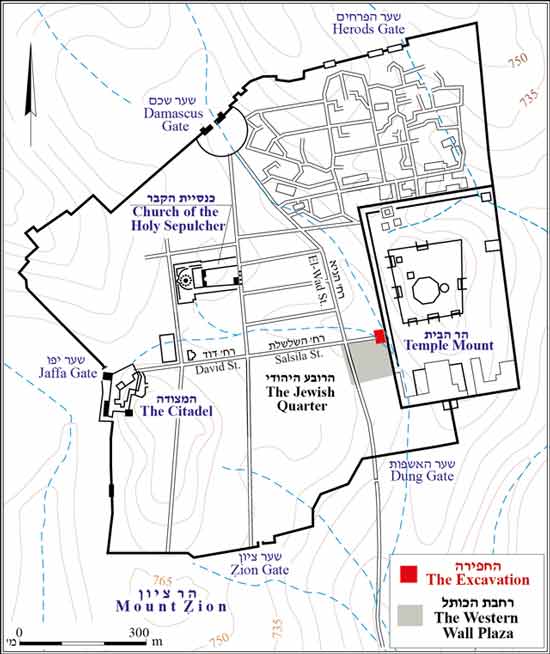

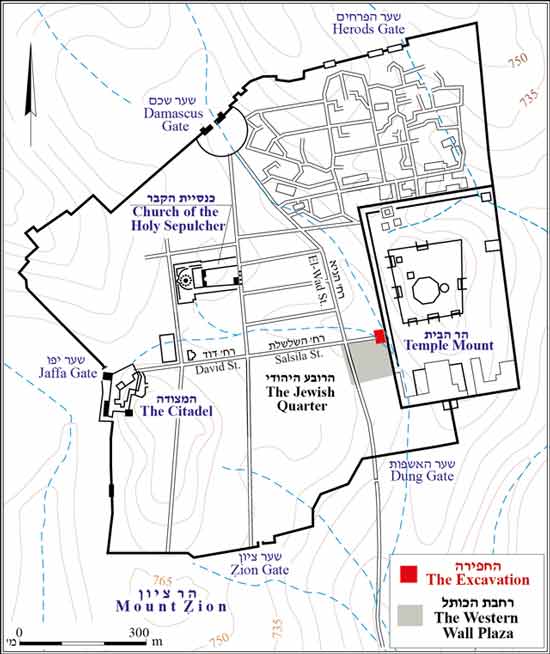

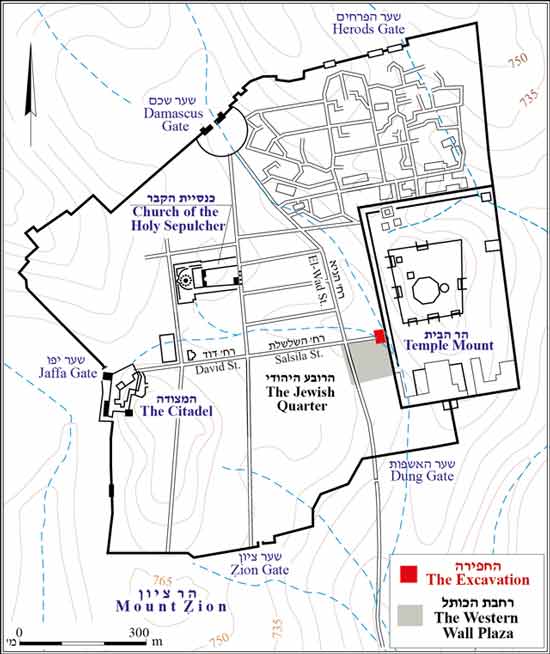

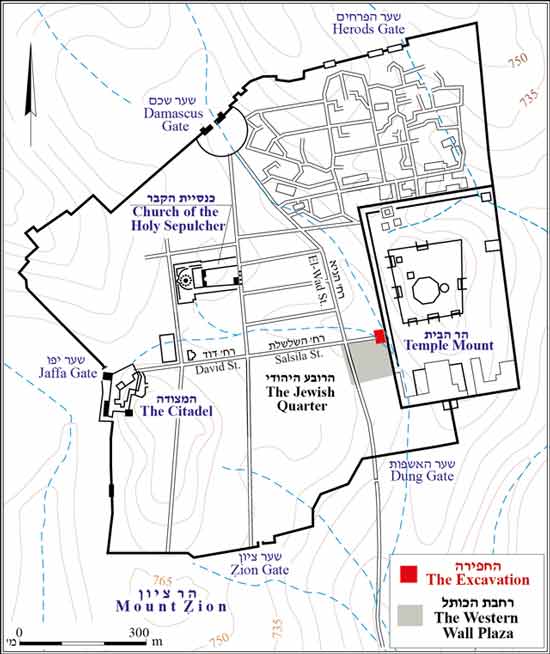

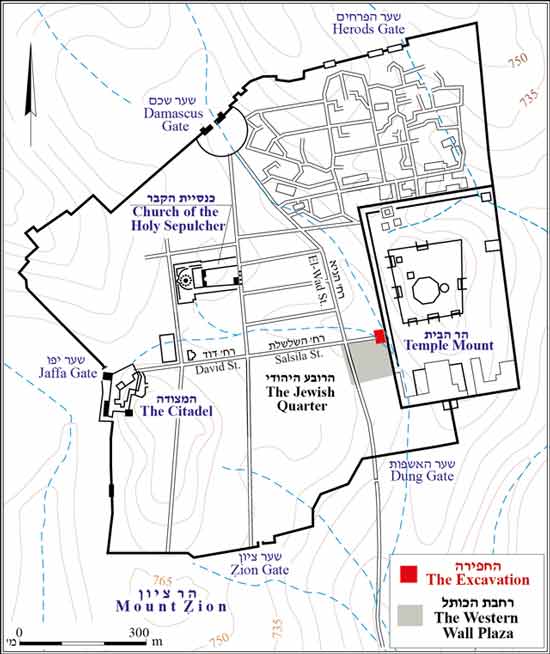

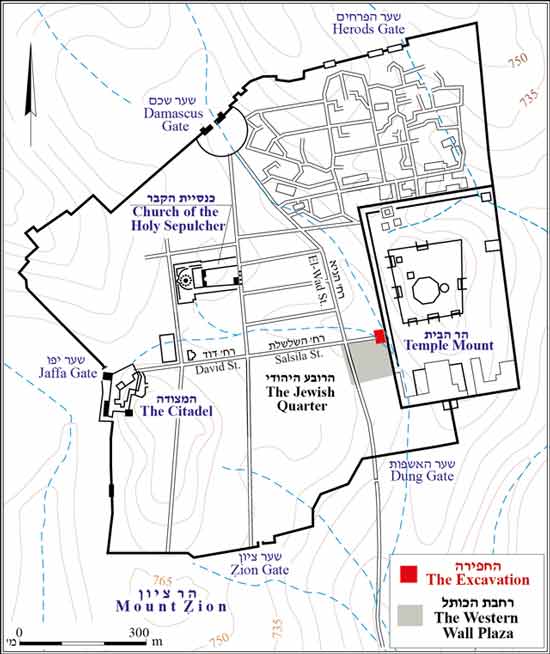

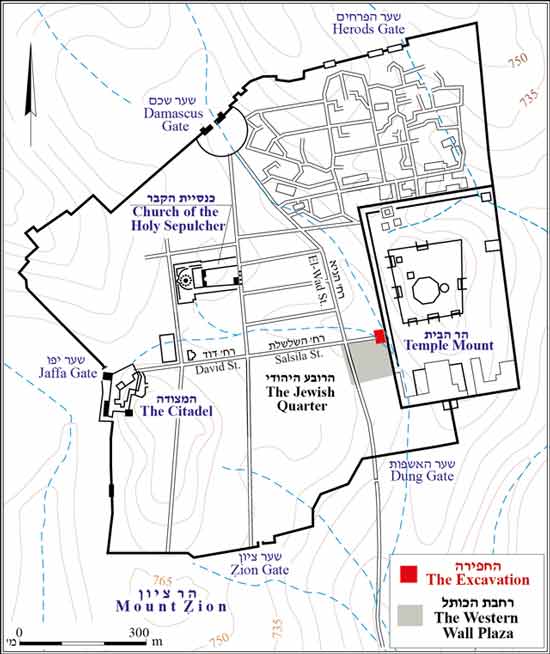

- Fig. 1 - Location map,

the Great Causeway, Wilson’s Bridge from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Location map, the Great Causeway, Wilson’s Bridge.

Onn et. al. (2011)

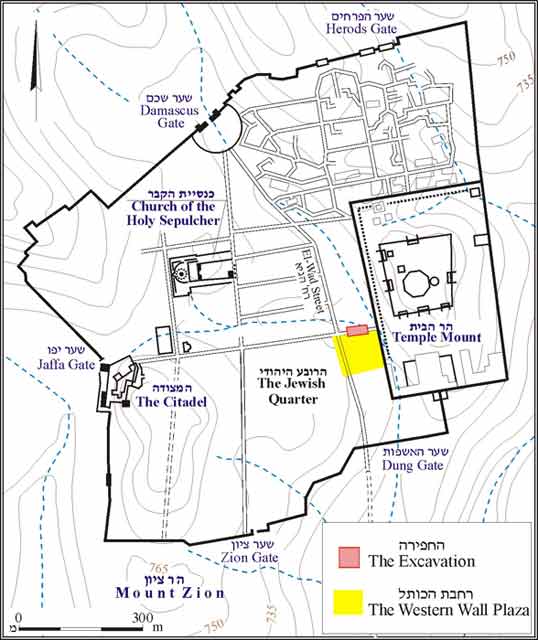

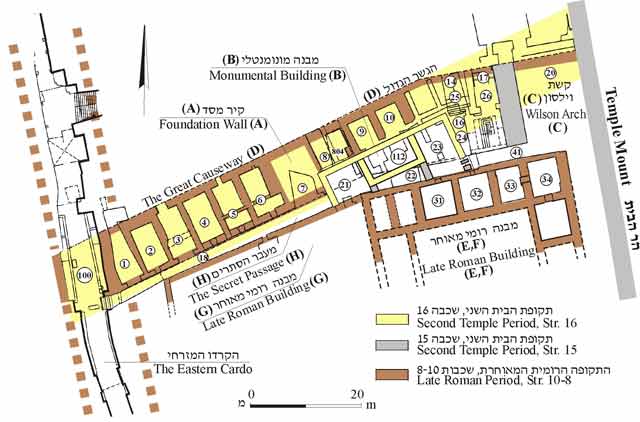

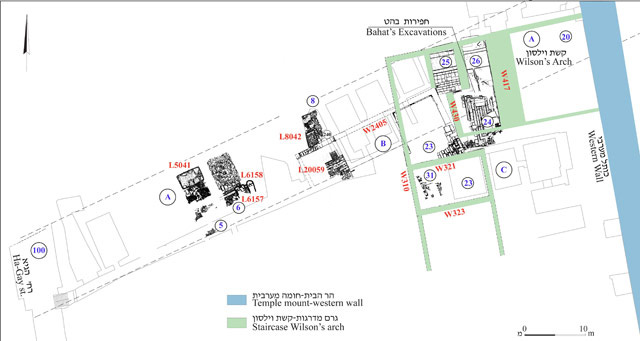

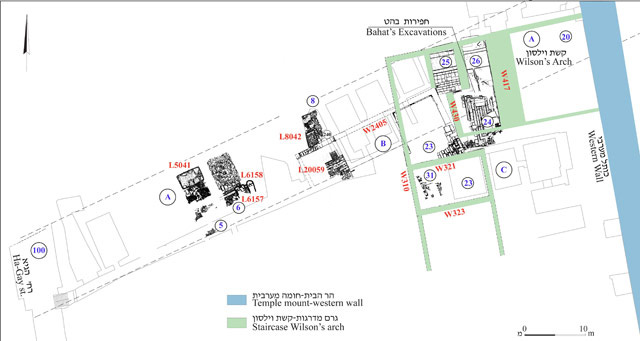

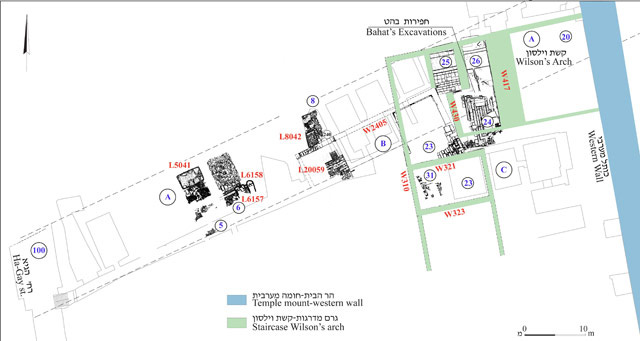

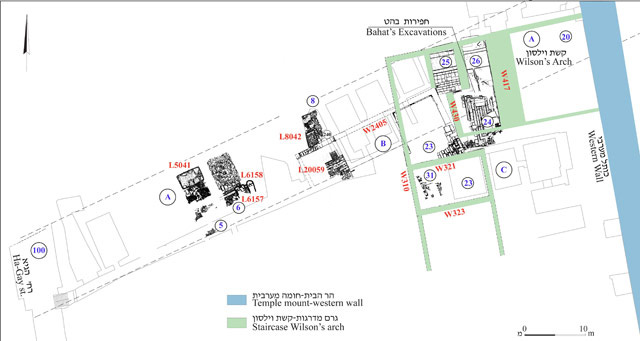

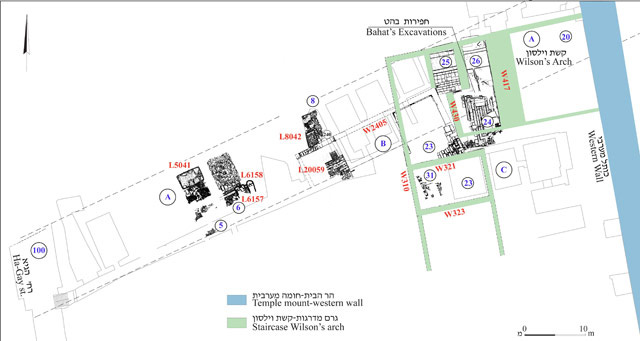

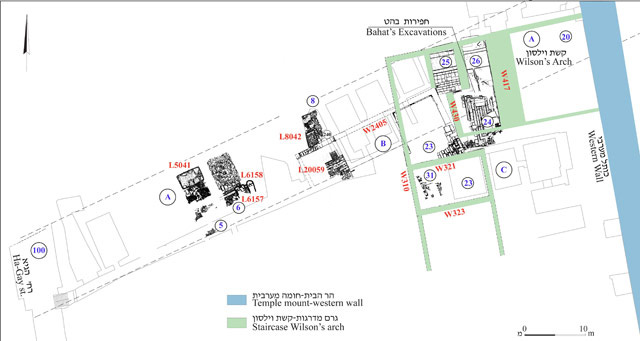

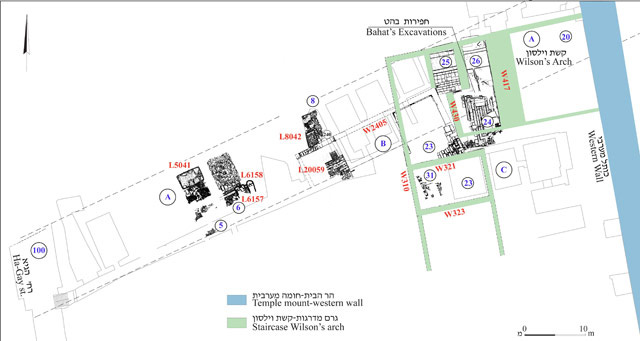

- Plan 1 Plan and Section

of excavation area west of Wilson’s Arch: the Great Causeway, the cast dam wall and the triclinium building from Weksler-Bdolah (2025)

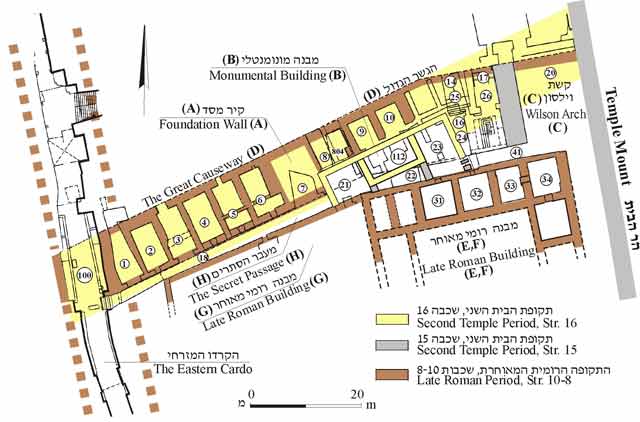

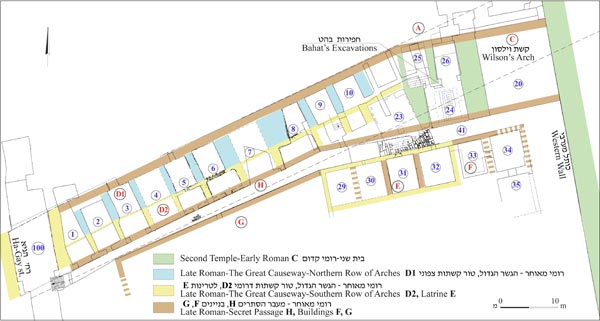

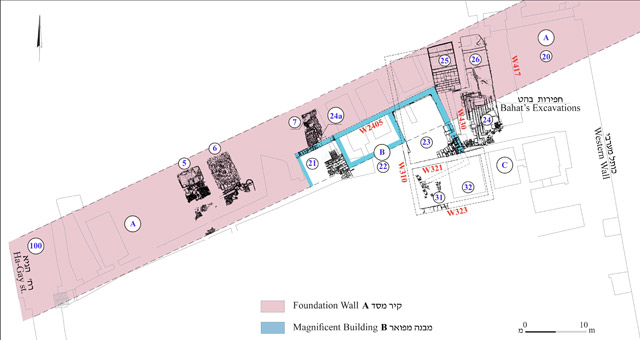

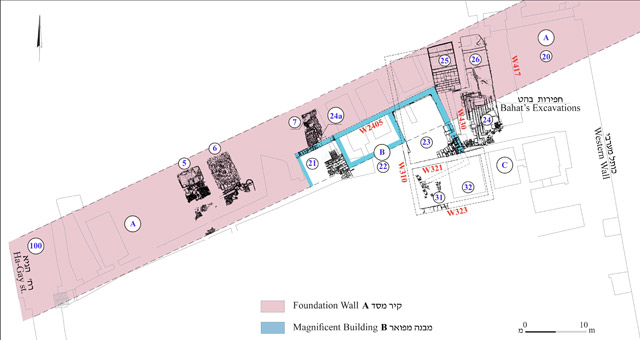

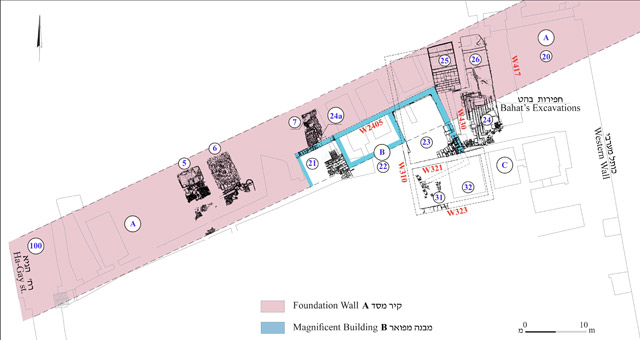

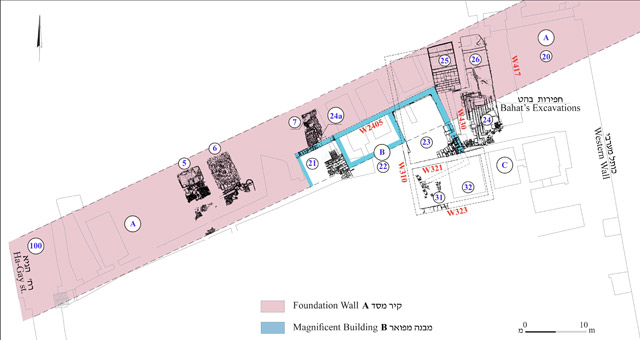

- Fig. 2 - General Plan

of the The Great Causeway excavations from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The Great Causeway excavations (Alexander Onn, 2007–2010), general plan.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 2 - General Plan

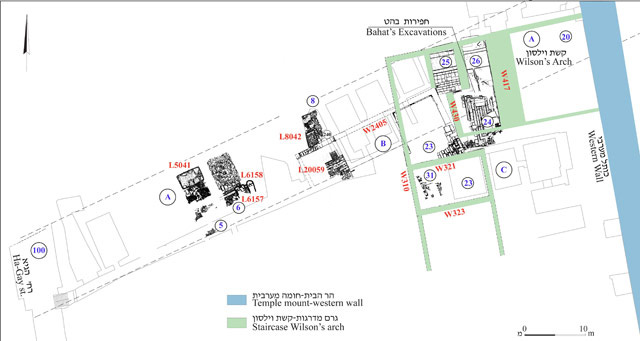

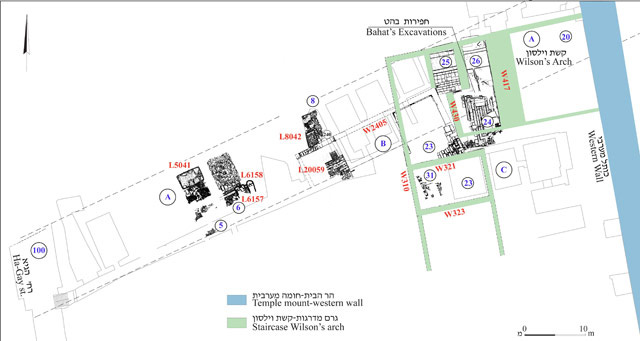

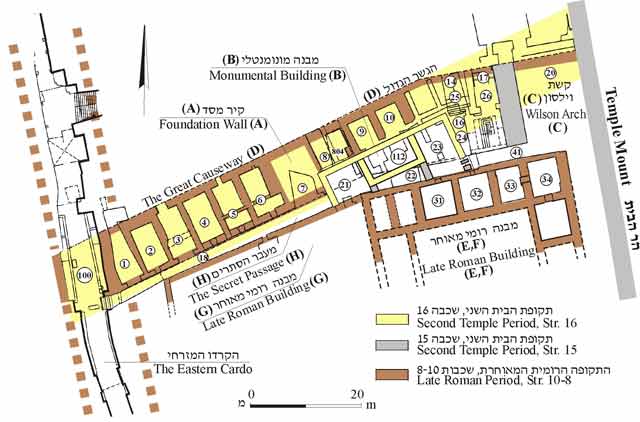

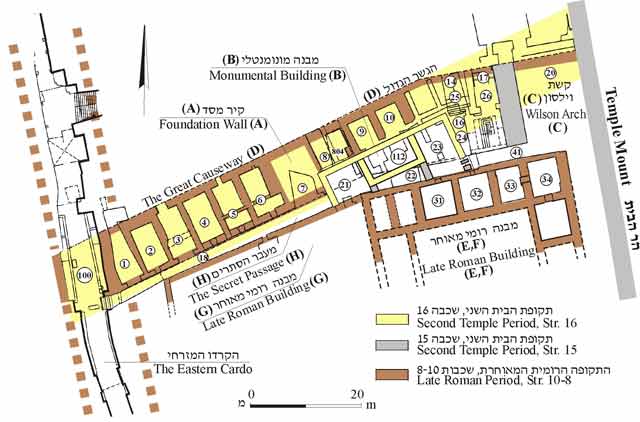

of the the Great Causeway excavations from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Wilson’s Arch, the Great Causeway and the monumental building from the excavations of A. Onn, general plan.

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 5 - Plan of Stratum 16

in Buildings A and B from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Stratum 16, Buildings A and B, plan.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 13 - Plan of Strata 15

to 13 from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Strata 15–13, plan.

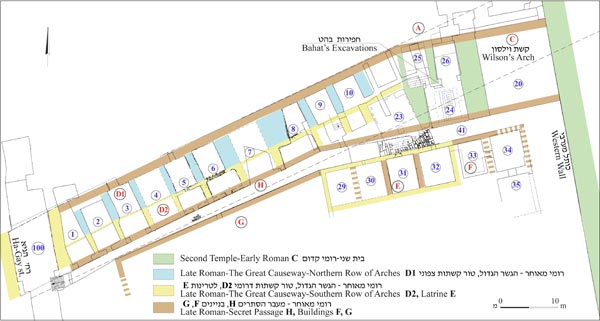

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 22 - Plan of Strata 11-8

(Roman Period) from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 22

Figure 22

General plan of the Roman period, Strata 11-8 plan.

Onn et. al. (2011)

- Plan 1 Plan and Section

of excavation area west of Wilson’s Arch: the Great Causeway, the cast dam wall and the triclinium building from Weksler-Bdolah (2025)

- Fig. 2 - General Plan

of the The Great Causeway excavations from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 2

Figure 2

The Great Causeway excavations (Alexander Onn, 2007–2010), general plan.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 2 - General Plan

of the the Great Causeway excavations from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Wilson’s Arch, the Great Causeway and the monumental building from the excavations of A. Onn, general plan.

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 5 - Plan of Stratum 16

in Buildings A and B from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Stratum 16, Buildings A and B, plan.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 13 - Plan of Strata 15

to 13 from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Strata 15–13, plan.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 22 - Plan of Strata 11-8

(Roman Period) from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 22

Figure 22

General plan of the Roman period, Strata 11-8 plan.

Onn et. al. (2011)

- Route of the Western Wall

Tunnel from Wikipedia

Route of the Western Wall Tunnel

Route of the Western Wall Tunnel

Modified by JoeDeRose - Courtesy of the Western Wall Heritage Foundation (GFDL- תמר הירדני, באדיבות הקרן למורשת הכותל-היוצר)

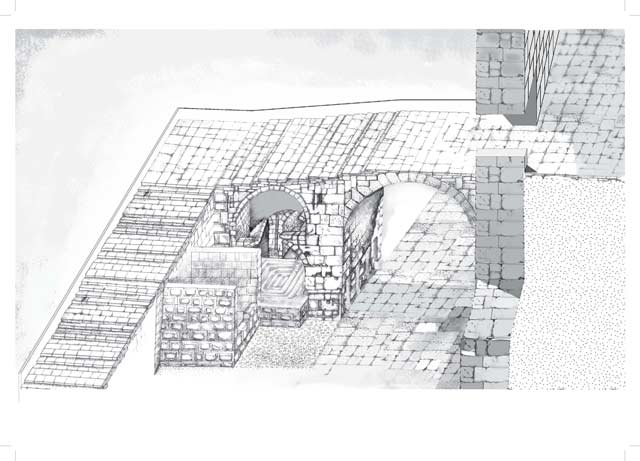

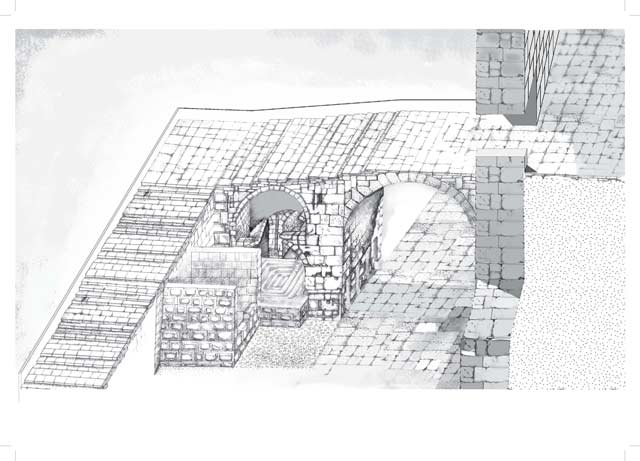

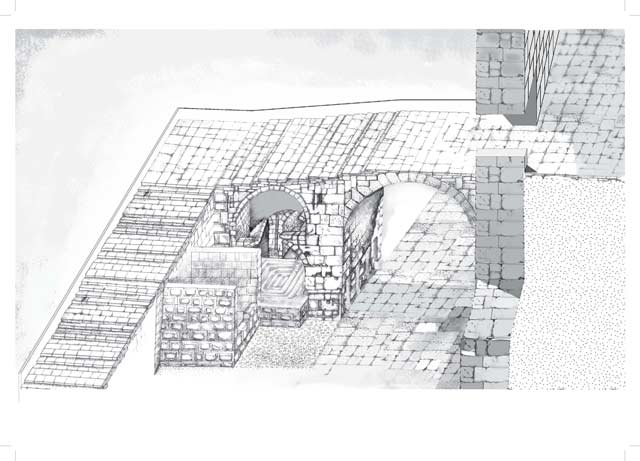

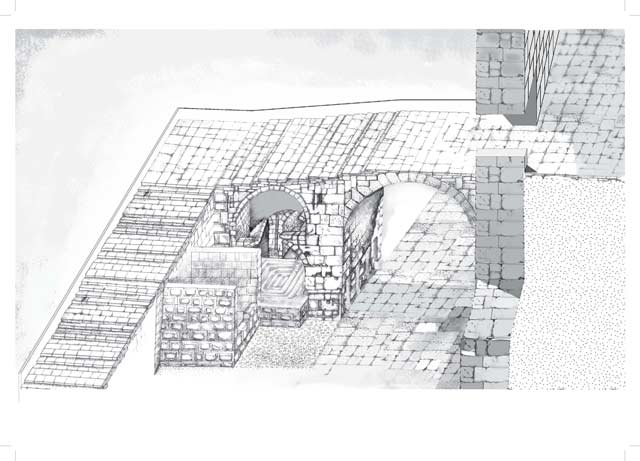

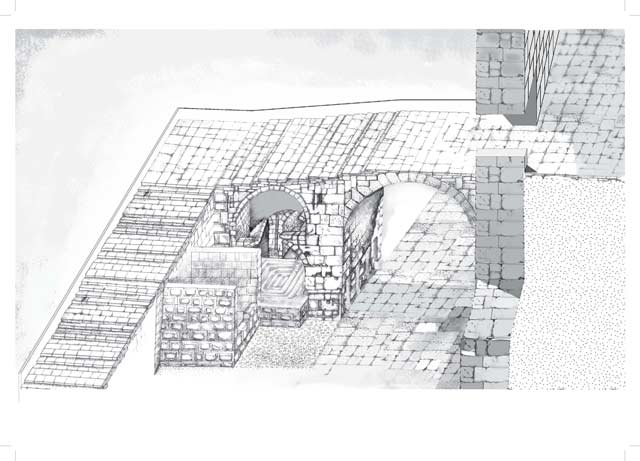

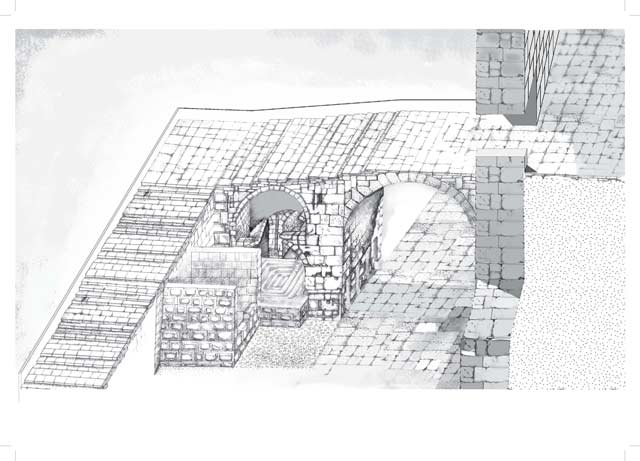

GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 - Wikipedia - Fig. 14 - Isometric reconstruction

of Wilson’s Arch interchange from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Wilson’s Arch interchange (Building C), isometric reconstruction

Drawing: Y. Shmidov

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 24 - Isometric reconstruction

of The Great Causeway from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 24

Figure 24

The Great Causeway, isometric reconstruction

Onn et. al. (2011)

- Fig. 3 - Section of the Great

Causeway looking north from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The Great Causeway, section, looking north.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Section of Wilson's Arch

from Wilson (1871)

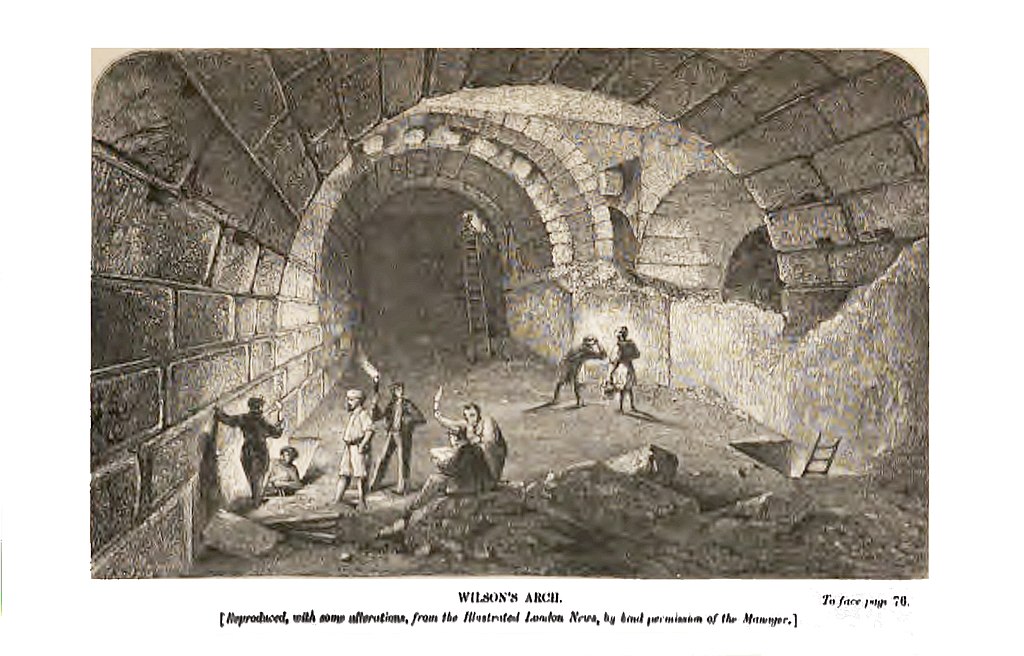

- Drawing of the discovery

of Wilson's Arch from Wilson (1871)

Drawing of the discovery of Wilson's Arch

Drawing of the discovery of Wilson's Arch

Click on image to open a high res magnifiable image in a new tab

Wilson (1871)

- Fig. 3 - Section of the Great

Causeway looking north from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The Great Causeway, section, looking north.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Section of Wilson's Arch

from Wilson (1871)

- Drawing of the discovery

of Wilson's Arch from Wilson (1871)

Drawing of the discovery of Wilson's Arch

Drawing of the discovery of Wilson's Arch

Click on image to open a high res magnifiable image in a new tab

Wilson (1871)

- Fig. 21 - Stratum 14 collapse

likely due to Fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE or possibly due to the Jerusalem Quake from Onn et. al. (2011)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

Room 504, destruction collapse (L5042) inside Installation 5060, looking west.

JW: This Figure was not described in the text of Onn et al (2011) and is difficult to locate in plans but may be damage from the Stratum 14 collapse. This collapse was assigned to the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE (Weksler-Bdolah, personal communication 28 Nov. 2023)

Onn et. al. (2011)

- Fig. 21 - Stratum 14 collapse

likely due to Fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE or possibly due to the Jerusalem Quake from Onn et. al. (2011)

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

Room 504, destruction collapse (L5042) inside Installation 5060, looking west.

JW: This Figure was not described in the text of Onn et al (2011) and is difficult to locate in plans but may be damage from the Stratum 14 collapse. This collapse was assigned to the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE (Weksler-Bdolah, personal communication 28 Nov. 2023)

Onn et. al. (2011)

- Fig. 2 - General Plan

of the the Great Causeway excavations from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Wilson’s Arch, the Great Causeway and the monumental building from the excavations of A. Onn, general plan.

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 3 - Plan of the remains

from the Roman period in the vicinity of Wilson’s Arch from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The remains from the Roman period in the vicinity of Wilson’s Arch, plan

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 4 - Section of Foundation

Wall 5006 and Monumental Building B, and the vaults of the Great Causeway above them from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Foundation Wall 5006 and Monumental Building B, and the vaults of the Great Causeway above them—10 North (10N) and 10 South (10S), and to their south—the Secret Passage (13), looking east; section.

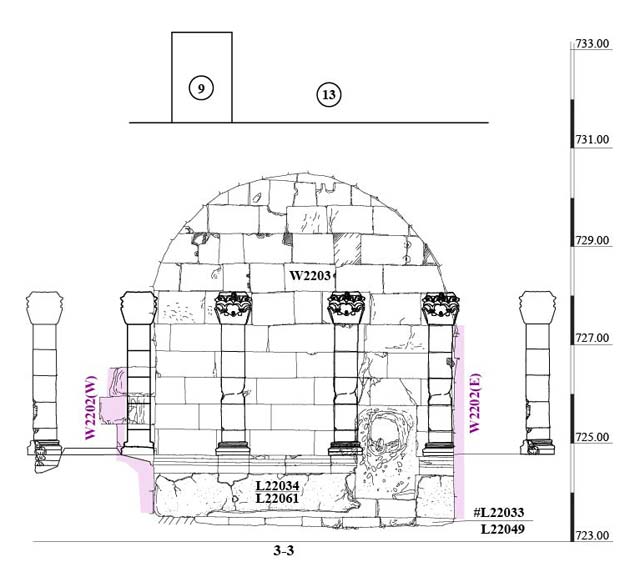

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 5 - Wilson’s Arch (20),

the monumental building (21–23) and the vaults of the Great Causeway above them from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Wilson’s Arch (20), the monumental building (21–23) and the vaults of the Great Causeway above them, looking north; section.

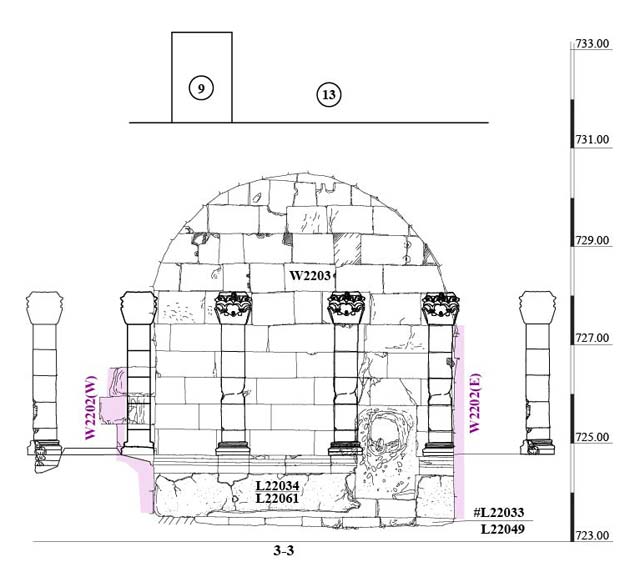

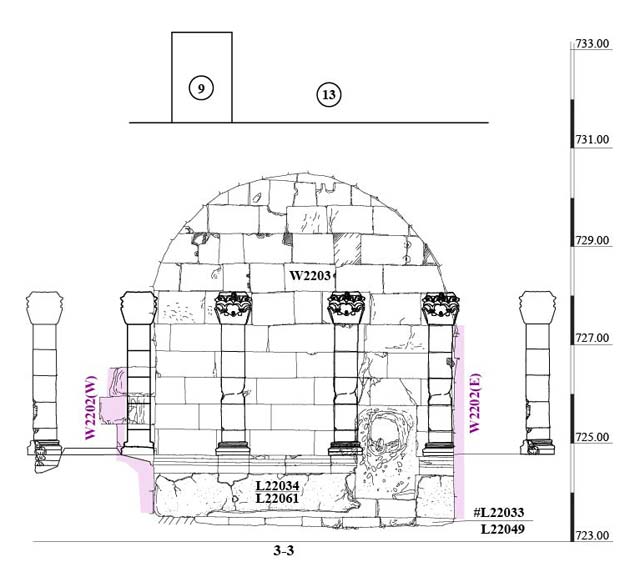

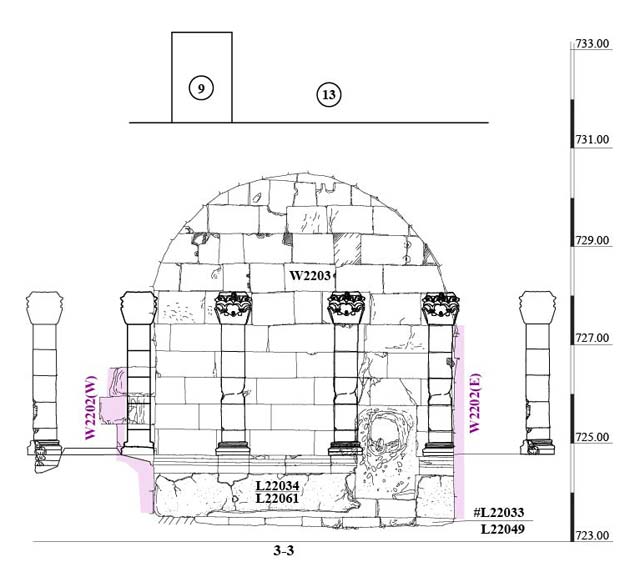

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 6 - Room 22, Wall 2203

from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Room 22, Wall 2203, looking north; section.

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

- Fig. 2 - General Plan

of the the Great Causeway excavations from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Wilson’s Arch, the Great Causeway and the monumental building from the excavations of A. Onn, general plan.

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 3 - Plan of the remains

from the Roman period in the vicinity of Wilson’s Arch from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The remains from the Roman period in the vicinity of Wilson’s Arch, plan

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 4 - Section of Foundation

Wall 5006 and Monumental Building B, and the vaults of the Great Causeway above them from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Foundation Wall 5006 and Monumental Building B, and the vaults of the Great Causeway above them—10 North (10N) and 10 South (10S), and to their south—the Secret Passage (13), looking east; section.

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 5 - Wilson’s Arch (20),

the monumental building (21–23) and the vaults of the Great Causeway above them from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 5

Figure 5

Wilson’s Arch (20), the monumental building (21–23) and the vaults of the Great Causeway above them, looking north; section.

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016) - Fig. 6 - Room 22, Wall 2203

from Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Room 22, Wall 2203, looking north; section.

Onn and Weksler-Bdolah (2016)

- Fig. 1 - Location map

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Location map

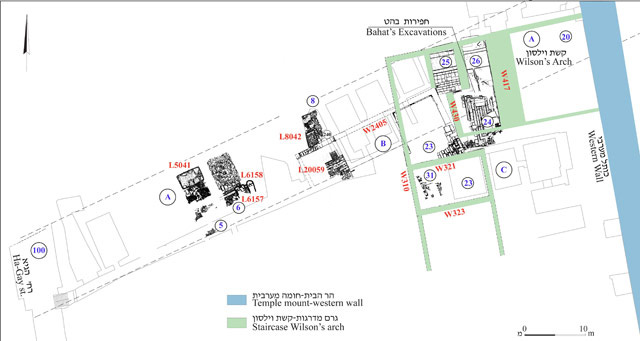

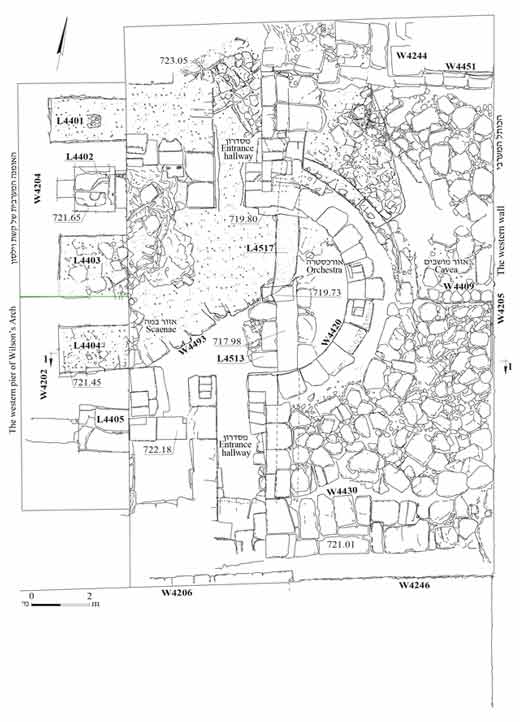

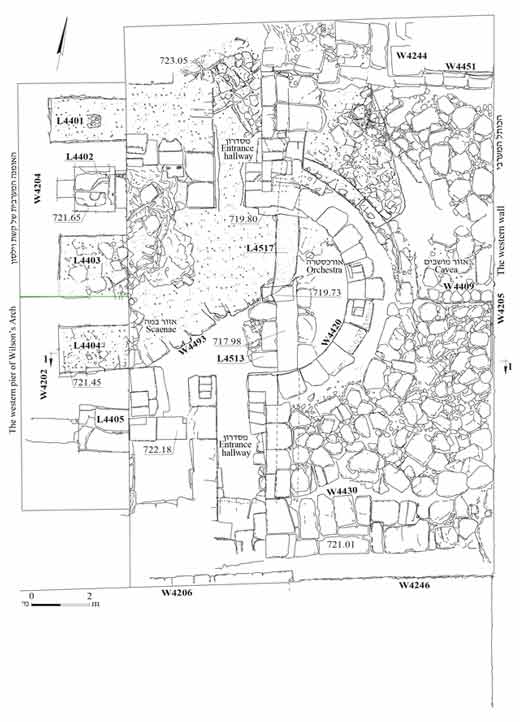

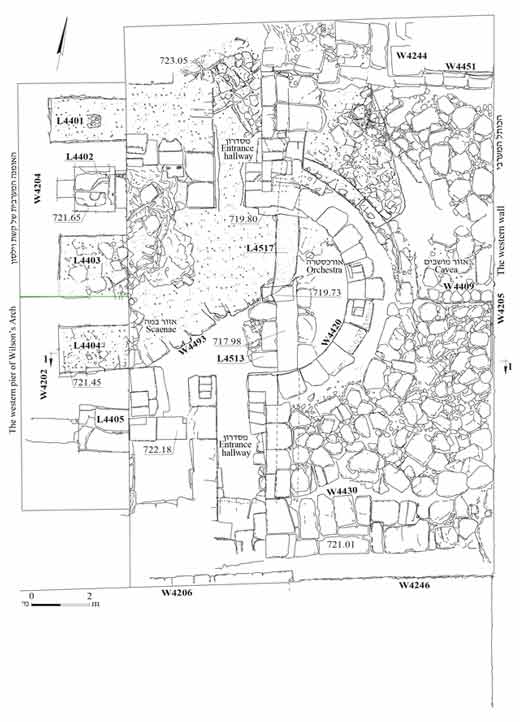

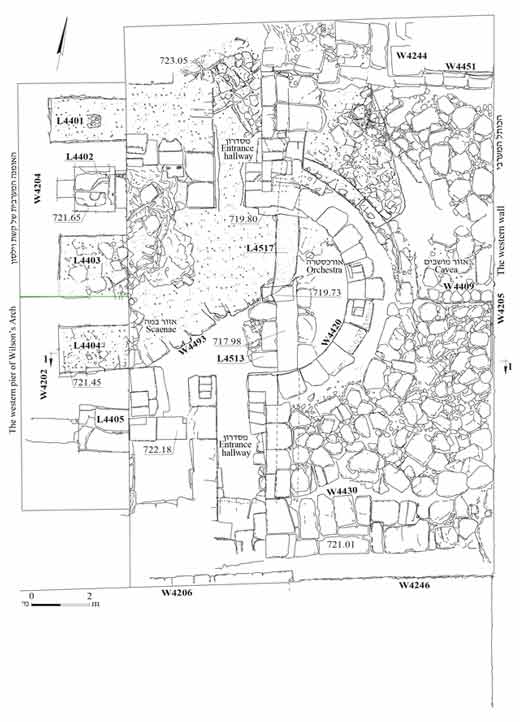

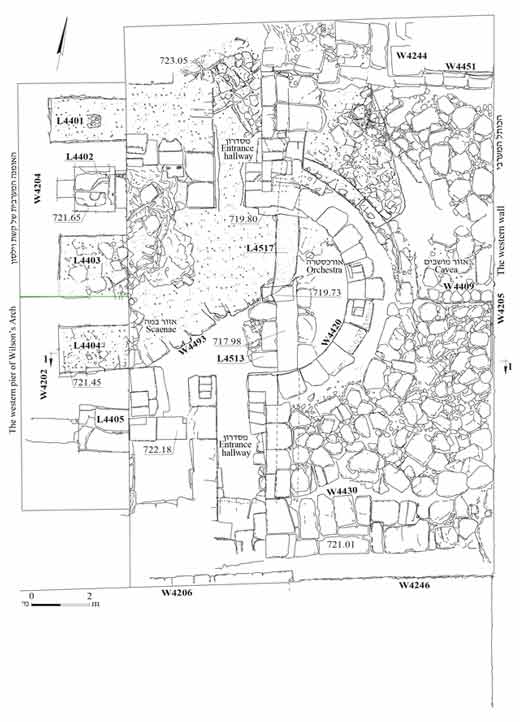

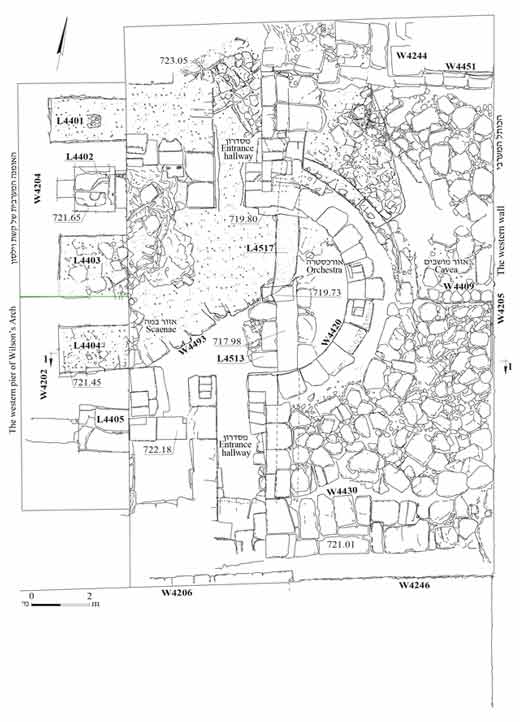

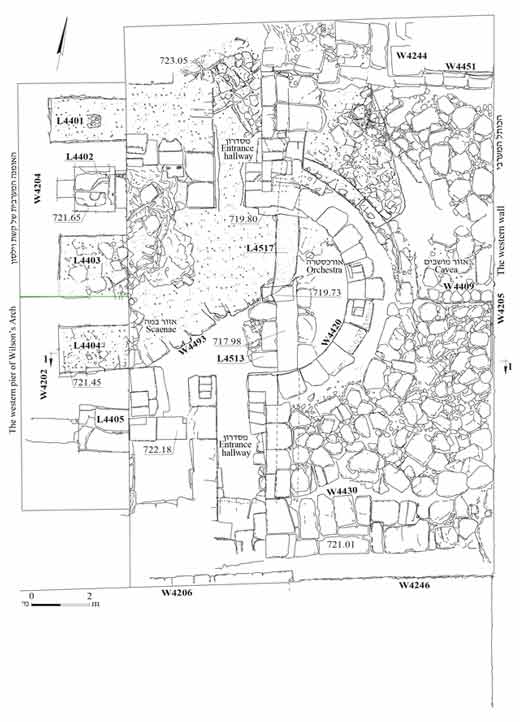

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 2 - Plan

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 3 - Section 1-1

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Section 1-1, looking south

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 4 - Western pier of

Wilson’s Arch from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Western pier of Wilson’s Arch, looking west.

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 5 - western wall

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 5

Figure 5

The western wall, looking east

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 6 - Theater-like structure

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Theater-like structure (L4420), looking southeast

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 7 - Channel 4261

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Channel 4261, looking northeast

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 8 - Plaster foundation

layers of Stratum I ‘Birkat al-Burāq’ reservoir from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Plaster foundation layers of Stratum I ‘Birkat al-Burāq’ reservoir, abutting Wilson’s Arch pier (W4204) and overlying Stratum 4 accumulations, looking northwest.

Uziel et al. (2019a)

- Fig. 1 - Location map

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Location map

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 2 - Plan

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 3 - Section 1-1

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Section 1-1, looking south

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 4 - Western pier of

Wilson’s Arch from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Western pier of Wilson’s Arch, looking west.

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 5 - western wall

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 5

Figure 5

The western wall, looking east

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 6 - Theater-like structure

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Theater-like structure (L4420), looking southeast

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 7 - Channel 4261

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Channel 4261, looking northeast

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 8 - Plaster foundation

layers of Stratum I ‘Birkat al-Burāq’ reservoir from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Plaster foundation layers of Stratum I ‘Birkat al-Burāq’ reservoir, abutting Wilson’s Arch pier (W4204) and overlying Stratum 4 accumulations, looking northwest.

Uziel et al. (2019a)

- Fig. 1 - Location map

from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map showing the area of the Temple Mount, the Great Causeway and Wilson's Arch.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 2 - Plan and Photo

of excavations from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the excavations, showing remains from Strata 8, 7 and 6a, b. Figure 2a:

- pink = Stratum 8

- green= Stratum 7C

- orange = Stratum 7B

- black = Stratum 6

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 3 - Photo of the newly

exposed section of the Western Wall beneath Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 3

Figure 3

View of the newly exposed section of the Western Wall beneath Wilson's Arch, looking east.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 4 - Section of the pier

of Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 4

Figure 4

View of the pier of Wilson's Arch, looking west. Numbers refer to strata as discussed in article.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 5 - Photo of Stratum 7

drainage channel from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 5

Figure 5

View of Stratum 7 drainage channel.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 9 - Section of the excavations

beneath Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Section of the excavations beneath Wilson's Arch, looking east. Numbers refer to strata as discussed in the article. Stratum 5B is not shown in the figure as it covered Strata 6

Uziel et al. (2019)

- Fig. 1 - Location map

from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map showing the area of the Temple Mount, the Great Causeway and Wilson's Arch.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 2 - Plan and Photo

of excavations from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the excavations, showing remains from Strata 8, 7 and 6a, b. Figure 2a:

- pink = Stratum 8

- green= Stratum 7C

- orange = Stratum 7B

- black = Stratum 6

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 3 - Photo of the newly

exposed section of the Western Wall beneath Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 3

Figure 3

View of the newly exposed section of the Western Wall beneath Wilson's Arch, looking east.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 4 - Section of the pier

of Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 4

Figure 4

View of the pier of Wilson's Arch, looking west. Numbers refer to strata as discussed in article.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 5 - Photo of Stratum 7

drainage channel from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 5

Figure 5

View of Stratum 7 drainage channel.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 9 - Section of the excavations

beneath Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Section of the excavations beneath Wilson's Arch, looking east. Numbers refer to strata as discussed in the article. Stratum 5B is not shown in the figure as it covered Strata 6

Uziel et al. (2019)

- Fig. 4 - Chronological chart

of Wilson's arch excavation from Regev et al (2020)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Summarizing chronological chart of Wilson's arch excavation. Comparing the rulers and major events in the history of Jerusalem to the radiocarbon dating of the strata. The grey vertical rectangles mark the length of the historical events. The histograms represent the total probability distributions of the radiocarbon measurements of each stratum (using the 'Sum' function in OxCal).

Regev et al (2020) - Fig. 3 - Age Model of Wilson's

arch excavation from Regev et al (2020)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Multiplot of the stratigraphy-based radiocarbon model of Wilson's arch. The areas plotted in black depict the modeled posterior age of the sample, while the light gray areas depict the entire calibrated range of the measurement.

Regev et al (2020)

- Fig. 4 - Chronological chart

of Wilson's arch excavation from Regev et al (2020)

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Summarizing chronological chart of Wilson's arch excavation. Comparing the rulers and major events in the history of Jerusalem to the radiocarbon dating of the strata. The grey vertical rectangles mark the length of the historical events. The histograms represent the total probability distributions of the radiocarbon measurements of each stratum (using the 'Sum' function in OxCal).

Regev et al (2020) - Fig. 3 - Age Model of Wilson's

arch excavation from Regev et al (2020)

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

Multiplot of the stratigraphy-based radiocarbon model of Wilson's arch. The areas plotted in black depict the modeled posterior age of the sample, while the light gray areas depict the entire calibrated range of the measurement.

Regev et al (2020)

- from Onn et. al. (2011)

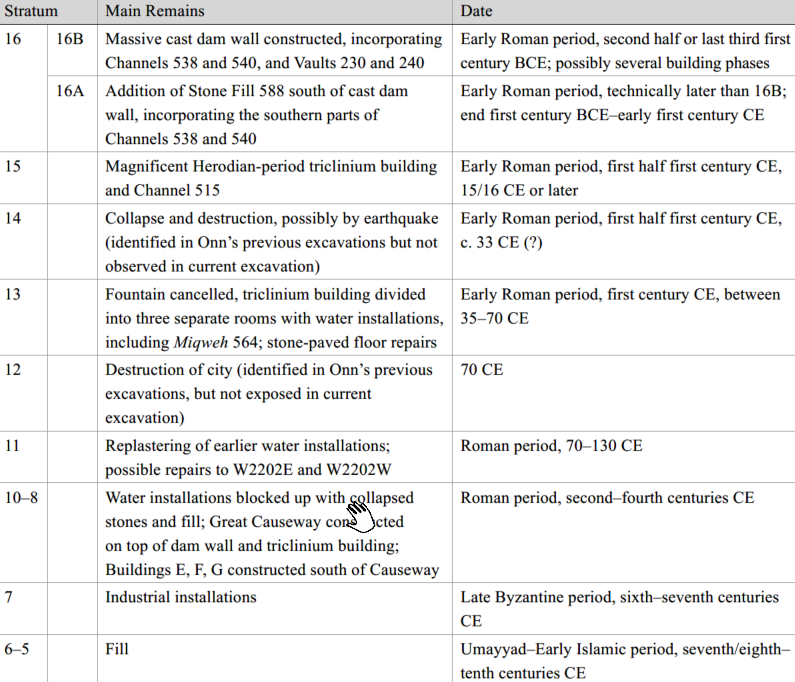

The finds identified in the excavation of the Great Causeway are ascribed to sixteen archaeological strata, listed below

| Stratum | Period | Principal Finds | Century or Year (CE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Modern, post 1967 | Removal of soil fill, repairs and concrete castings | 20th-21st centuries, post 1967 |

| 2 | Modern, Mandatory and Ottoman | Cisterns, cesspits | 19th-20th centuries |

| 3 | Mamluk–Ayyubid | Installations | 13th-15th centuries |

| 4 | Crusader | Pillar in a Crusader building | 12th century |

| 5 | Early Islamic | Installations | 9th-10th centuries |

| 6 | Umayyad | Covering the top of the Secret Passage with a barrel vault and the installation of a staircase linking the Secret Passage to the Street of the Chain | 7th-8th centuries |

| 7A | Late Byzantine | Installations and floors | 6th-7th centuries |

| 7B | Early Byzantine | Installations | 4th-5th centuries |

| 8 | Late Roman-Aelia Capitolina | Expansion of the building E into a large structure with rooms (F), construction of another building to the west (Building G), and formation of the Secret Passage (H) between the Great Causeway (D) and Buildings F and G | 3rd-4th centuries |

| 9 | Late Roman | Construction of the southern line of arches in the Great Causeway (D2). Completion of the causeway structure and paving the decumanus on top of it. Construction of the latrine structure south of the Great Causeway (E) | 2nd-3rd centuries |

| 10 | Late Roman | Construction of the northern line of arches (D1) in the east in the east in the Great Causeway. | Early 2nd century |

| 11 | Late Roman | Industrial ovens and installations | Late 1st-Early 2nd centuries |

| 12 | Destruction of the Second Temple | Destruction layer 50 m west of the Temple Mount and further west. No damage was caused to Wilson’s Arch and the arches adjacent to it. | 70 CE |

| 13A | Second Temple | Ritual baths and installations | 1st century, before 70 CE |

| 13B | Early Roman, Second Temple Period | Renovation of Wilson’s Arch and completion of Staircase C (‘the interchange’) connected to it | 1st century, before 70 CE |

| 13C | Early Roman, Second Temple Period | Buildings next to Wilson’s Arch | 1st century, before 70 CE |

| 14(?) | Early Roman, Second Temple Period | Collapse—destruction, possibly by an earthquake. Damage to Wilson’s Arch | 33 CE (presumed) |

| 15 | Early Roman, Second Temple Period | Expansion of the Temple Mount during Herod’s reign, Wilson’s Arch (C) | 1st century BCE |

| 16 | Late Hellenistic–Early Roman | Wide foundation wall (W5006, A) and a monumental public building (B) | First century BCE (Hasmonean or Herodian period), before the expansion of the Temple Mount |

| Stratum | Period | Principal Finds | Century or Year (CE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Abbasid | In Room 22, soil accumulated to a height of 3 m above the level of the channel (L22014), and fragments of contemporary pottery vessels were found inside it. |

Eighth–Tenth Centuries CE |

| 7, 6 | Byzantine and Umayyad | Rooms 9 and 10. A new pavement was installed inside the two square pools (L9008, L10022; Fig. 3). The pavement was made of square stone slabs, some of which were in secondary use (L9007 in Room 9, L10014 in Room 10; Figs. 3, 4, 12). Most of the paving stones had smooth surfaces and some were notched with parallel grooved lines. The notched slabs were arranged randomly with no particular attention paid to the direction of the notches in them (some ran north–south and others, east–west), and it therefore seems that they were installed here in secondary use. The level of Stone Pavement 10014 was c. 0.15 m higher than the bottom of the pool (L10022; no excavation was conducted below the pavement in Pool 9008). Four sixth-century Byzantine coins discovered below these paving stones (the latest coin minted in 594/595 CE) indicate the coins were sealed there in the late sixth century or later. A later plaster floor was preserved above the paving stones, and soil and collapsed stones that included fragments of pottery vessels from the Umayyad period accumulated above the plaster floor. |

Sixth–Eighth Centuries CE |

| 11-8 | Roman | During this period, Vaults 9 and 10 in the Great Causeway (Fig. 2) were constructed above the tops of the dam wall (W5006). The Great Causeway (‘Giant Viaduct’) is a long arch bridge (length c. 100 m) that extends between the Temple Mount in the east and the Eastern Cardo in the west, and includes the monumental Wilson’s Arch that is incorporated in the Herodian courses of the Temple Mount, and west of it two rows of arches, in the north and south, that were built one after the other. The northern row of arches was erected first and was used for a narrow bridge between the Temple Mount and the Western Hill, and later the narrow bridge was made wider with the addition of another row of arches to the south and a road was paved on top of the widened bridge that led to the Temple Mount (for the history of research on the building see (Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011). |

after the Destruction of 70 CE until the Fourth Century CE |

| 15-13 | Early Roman | Major changes occurred in the buildings during these phases. The magnificent building’s interior was divided into three separate spaces, each covered by a vault, in which water installations were constructed (Fig. 3:21–23). It is impossible to date the construction phases that occurred one after the other in the late Second Temple period, prior to 70 CE, with precision. It seems that the changes are connected to the expansion of the Herodian Temple Mount and the building of Wilson’s Arch, as well as the Great Revolt in 66–70 CE (see also Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011). |

First century BCE - First century CE, until 70 CE |

| 16a or 15 | Early Roman | Sometime after the monumental building was constructed, the level of the road leading to the Temple Mount was raised by constructing a large massive wall that presumably carried on it the elevated road. The wide wall (referred to as the ‘foundation wall’ or the ‘dam wall’ W5006 in previous publications; Figs. 2–4) was built up against the northern wall of the monumental building and concealed its facade. The wall was constructed using opus caementicium—boulders and variously sized fieldstones bonded with very hard mortar. Its known length is c. 70 m—from the axis of Ha-Gay Street in the west, where it was documented in the past (Hamilton 1933:334, 36) until Room 10 of the Great Causeway in the east (below)—and it is 14 m wide west of and c. 6 m wide north of the monumental building (Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011: Foundation Wall W5006; Building A). The wall extends from the southwest to the northeast, perpendicular to the axis of the Tyropoeon Valley. Its continuation east of the monumental building is still unknown. |

First century BCE |

| 16 | Early Roman | The most ancient remains that were discovered are related to a monumental building from the time of King Herod (Building B; Figs. 2; 3:21–23, 112; 4; 5; Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011. The structure seems to have been constructed south of the street that led to the western gate in the pre-Herodian Temple Mount wall (Kiponos Gate). , This street was later raised onto a foundation wall of cast concrete (built of opus caementicium [Roman cement]; below, W5006). In the past, Monumental Building B and Foundation Wall 5006 were ascribed to Stratum 16. Monumental Building B (internal dimensions: length 24.5 m, width 10–11 m) included two halls (21, 23), with a built water reservoir (112) and a fountain (22) that protruded to the south situated between them. The building’s eastern hall (23) was first discovered by Warren in the late nineteenth century CE and was known as the ‘Masonic Hall’ (Wilson1880; Warren and Conder 1884). This hall was studied again by Stinespring (1967), Ben-Dov (1982:178–180) and Bahat and Meir (Bahat 2013:113–128) in the twentieth century and has been referred to as the ‘Hasmonean Hall’ or the ‘Herodian Hall’. In 2007–2008, Onn exposed the structure’s western hall (21; Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011: Hall 21), and in the current excavation, the central part of the building was exposed. This part includes a water reservoir (112) and a fountain (22), which was initially identified as a nympheon (Onn and Weksler-Bdolah 2011; Stiebel 2013). Recently, however, we have suggested reconstructing the building as a complex Herodian triclinium with a fountain in its center (Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Patrich 2016; Patrich and Weksler-Bdolah 2016). The entrance to the building was in the southern part of the eastern wall in Hall 23. The building’s walls facing the interior were built of ashlars, and their bottom parts were decorated with a protruding cornice, whose top was c. 1.25 m above the floor. Protruding from the walls above the cornice were flat square pilasters bearing Corinthian capitals with smooth leaves, and square recesses above them were used to secure the roof beams (Fig. 6). |

First century BCE |

- from Uziel et al. (2019a)

|

Layer

|

Period (CE)

|

Main finds

|

|

0

|

Modern

|

Synagogue prayer hall

|

|

1

|

Mamluk and Ottoman

|

Two phases of reservoir ‘Birkat al-Burāq’

|

|

2

|

Early Islamic

|

Pits and walls (W4244, W4246)

|

|

3

|

Late fourth century

|

Wall (W4206) of Building F

|

|

4

|

Fourth century

|

Refuse accumulations

|

|

5

|

Third century

|

Thick fill of earth and stones, and water channel (L4261)

|

|

6

|

Second century

|

Small theater-like structure

|

|

7A

|

Early to Late Roman

|

Construction of two cavities (L4401, L4403) in northern part of Wilson’s Arch pier (L4202)

|

|

7B

|

Early Roman

|

Western Wall courses, southern part of Wilson’s Arch pier (L4202) and drainage channel (L4513)

|

|

7C

|

Early Roman

|

Northern part of Wilson’s Arch pier (L4204) and drainage channel (L4517)

|

|

8

|

Hasmonean

|

Massive wall (W4493)

|

- from Uziel et al. (2019a)

- Fig. 1 - Location map

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Location map

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 2 - Plan

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 3 - Section 1-1

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Section 1-1, looking south

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 4 - Western pier of

Wilson’s Arch from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Western pier of Wilson’s Arch, looking west.

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 5 - western wall

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 5

Figure 5

The western wall, looking east

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 6 - Theater-like structure

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Theater-like structure (L4420), looking southeast

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 7 - Channel 4261

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Channel 4261, looking northeast

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 8 - Plaster foundation

layers of Stratum I ‘Birkat al-Burāq’ reservoir from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Plaster foundation layers of Stratum I ‘Birkat al-Burāq’ reservoir, abutting Wilson’s Arch pier (W4204) and overlying Stratum 4 accumulations, looking northwest.

Uziel et al. (2019a)

- Fig. 1 - Location map

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Location map

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 2 - Plan

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 3 - Section 1-1

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Section 1-1, looking south

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 4 - Western pier of

Wilson’s Arch from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 4

Figure 4

Western pier of Wilson’s Arch, looking west.

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 5 - western wall

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 5

Figure 5

The western wall, looking east

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 6 - Theater-like structure

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 6

Figure 6

Theater-like structure (L4420), looking southeast

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 7 - Channel 4261

from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 7

Figure 7

Channel 4261, looking northeast

Uziel et al. (2019a) - Fig. 8 - Plaster foundation

layers of Stratum I ‘Birkat al-Burāq’ reservoir from Uziel et al. (2019a)

Figure 8

Figure 8

Plaster foundation layers of Stratum I ‘Birkat al-Burāq’ reservoir, abutting Wilson’s Arch pier (W4204) and overlying Stratum 4 accumulations, looking northwest.

Uziel et al. (2019a)

he earliest element uncovered in the area is a wide solid wall (W4493; over 8 m wide) built on a southwest–northeast axis. The wall was constructed by casting yellowish mortar mixed with small fieldstones, and its southeastern face was faced with a row of large fieldstones; the northwestern face was not exposed as it lay beyond the excavated area. The northeastern part of the wall was cut by the Western Wall (W4205), which it therefore clearly predates. Similarly constructed and aligned wall segments have been discovered in several places to the west of the excavation area, and they are probably parts of the same massive wall (Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011; Onn and Weksler-Bdolah 2016). The function of this wall has been widely discussed: it has been proposed that it was part of the First Wall (Warren and Conder 1884:206–207; Uziel, Lieberman and Solomon 2017), the foundation of the great causeway (Hamilton 1932; 1933), a dam wall (Bahat 2000:38) and a road-bearing dam wall (Weksler-Bdolah 2015). Based on the stratigraphy and data from previous excavations (Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011; Bahat 2013), this solid wall probably dates to the Hasmonean period.

The pier of Wilson’s Arch (W4202, W4204), the Western Wall (W4205) and drainage channels (L4513, L4517) are attributed to this

stratum (Figs. 2, 3). Three construction phases (7C–7A) have been identified in the western pier supporting Wilson’s Arch

(W4202, W4204; c. 15 m total length; Fig. 4). This pier is composed of two adjacent piers, a northern one W4204; 5.0 × 7.5 m)

and a southern one (W4202; 5.0 × 7.5 m), exhibiting different methods and dates of construction.

In the earliest phase (7C), in the Early Roman period, the northern pier (W4204) was built of eleven courses

of stones with drafted margins. Pier 4204 probably originally bore an earlier arch that was as wide as the pier

(7.5 m; not preserved). A small cavity built in the center of the pier (L4402; 2.45 m long) had an arched

opening leading to it (1.3 m wide. 3.15 m max. height) with a stone lintel surmounted by a relieving arch.

Pier 4204 was built on top of the Stratum 8 massive wall (W4493), which served as its base. In the interim phase (7B),

within the Early Roman period, the southern pier (L4202) was built of six courses of large stones without drafted margins.

Wilson’s Arch itself was also built of similar large stones, and the southern pier and the existing arch were probably

constructed at the same phase. Two small rectangular cavities (L4404—1.5 × 2.4 m, height 3.5 m; L4405—1.5 × 1.8 m, height 3.5 m)

were built inside the southern pier. The openings to the two cavities are constructed in a similar manner, with a

large stone lintel supported by the entrance doorjambs. Cavity 4405 was excavated in the past by Warren while digging

the western of the two shafts that he dug at the site. The Western Wall was evidently built in this phase (below).

In the latest phase of the stratum (7A), probably in the Late Roman period, two additional cavities

(L4401—1.4 × 2.7 m; L4403—2.1 × 2.3 m) were cut into the northern pier (W4204). It seems that W4493 from Stratum 8

was probably leveled and used as the floor for the two cavities. Despite the different dimensions of the cavities in

the northern and southern piers, their construction technique is similar, and they were therefore probably opened up

at the same phase. Sockets for lintels were cut in the upper courses of the entrances to the two cavities; the lintels,

presumably made of wood, were not extant. Since the socket in the southern jamb of cavity L4403 was cut into the

southern pier (W4202), it can be established that the two cavities post-date the construction of the W4202 pier,

and that they belong to the final construction phase (7A) of the western pier of Wilson’s Arch.

The Western Wall stands c. 13 m to the east of the Wilson’s Arch pier and it was probably built in Phase 7B,

together with the southern pier (W4202). The excavation unearthed nine additional well-preserved, stone

courses of the Western Wall (Fig. 5), dressed with double drafted margins. Based on the historical sources

and archaeological excavations, the Western Wall was constructed in the Early Roman period, namely between the

rule of Herod the Great and the period of the Roman procurators (Reich and Baruch 2017).

A drainage channel (L4513, L4517; c. 0.95 m wide; Fig. 6) unearthed in the center of the excavation area

was built on north–south alignment, parallel to the Western Wall and c. 7 m to its west. The channel was

sealed beneath a building attributed to Stratum 6 (below). The northern part of the channel (L4517) was

hewn into W4493 of Stratum 8, whereas its southern section (L4513) was constructed of two thick walls

(0.55 m wide) built of ashlar stones. The upper courses of the built channel (L4513) appears to have been

dismantled when the Stratum 6 theater-like structure was built. The floor of the northern rock-hewn channel

is higher than that of the southern, stone-built channel. The northern channel may have been hewn in an

early phase of the stratum (7C), veering slightly to the west; the southern section may have been built

in a later phase (7B), with the widening of the Wilson’s Arch pier and renewed planning of the area.

A small theater-like structure (Fig. 6) was unearthed that contained an orchestra, a stage area, entrance passages, staircases and a seating area; the building was not completed. The structure was built over the Stratum 7 drainage channel, and above Stratum 8 Wall 4493, parts of which were removed and leveled to create a base for the structure. The outer perimeter of the structure is rectangular, and it is delineated by Wilson’s Arch in the west, the Western Wall in the east and by walls in the south (W4430) and in the north (W4451). A semi-circular wall (W4420) curving delineated the area of the orchestra (6 m diam.) was preserved in the center of the structure; pilasters, only partially finished, were preserved at each end of the wall. The stage is narrow (c. 3.0 × 10.5 m) and bounded to north and south by two pedestals (0.7 × 1.0 m), that are 1.2 m higher than the stage; the profiles of the pedestals were not fully finished. The stage was founded mainly on top of W4493, but large protrusions discovered in the wall in this area are evidence of preparations for a superstructure that was not completed; the stage was apparently therefore not finished. The passages (aditi maximi; c. 1.5 m wide) led into the structure from the north and south and their walls were built of well-dressed stones. A staircase (0.6 m wide) found at the end of each passage led to the seats, whose construction was not completed. Steps were installed in the seating area as a base for an array of stone seats (cavea); the seats themselves were not found, either because they were never built, or as a result of secondary use of the stones in a later period (see for example, Reich and Billig 2000). The steps found in the area of W4493 were built into the wall itself, whereas the steps to the east and south of W4493 were built using a system of supporting walls with large stones between them. Architectural elements from the walls of the Temple Mount were found within these stone fills (for a review of methods of fixing theater seats, see Sear 2006:71–80). A retaining wall (W4409) uncovered in the center of the seating area and built of roughly dressed small and medium-sized stones, abutted the Western Wall. The wall, which clearly post-dates the Western Wall, provides a stratigraphic anchor with which to date the structure. Two sections were excavated in the foundations of the seating, south of W4409 and W4451, in an attempt to date the structure. The sections retrieved ceramic finds as well as roof tiles, bricks and clay pipes characteristic of the period following Jerusalem’s destruction in 70 CE (first half of second century CE; for discussion see Uziel, Lieberman and Solomon 2017), thus dating the structure’s construction. The theater-like structure unearthed in the excavation is the smallest to be discovered so far in the country (Segal 2000: Theater Table Appendix; Mazor 2007; Weiss 2014:81–100). Although the building was not fully completed, it may have been used by the citizens of the Roman colony of Aelia Capitolina from the time when it was built early in the second century CE until it was deliberately buried under a fill of earth and stones in the latter half of the third century CE (below, Stratum 5).

A uniform fill of gray-brown soil uncovered throughout the excavation area contained a large quantity of small stones and gravel (L4258, L4305, L4339, L4341; at least 3 m thick; see Fig. 3). The fill was deposited from different angles, abutting the Western Wall and the piers (L4202, L4204) of Wilson’s Arch, as well as W4420 of the theater-like structure. The fill sealed the Stratum 6 theater-like structure. A water channel (L4261; 0.3 m inner width, 0.64 m outer width, depth 0.5 m; Fig. 7) unearthed in the upper part of the fill led from north to south, veering westward in the southern part of the excavation area. The channel had small fieldstone walls and a stone slab roof, and was not plastered, and its floor was covered with a hard layer of moist brown sediment. The channel was cut by the foundation trench of a wall (W4206) from a previously excavated Building F, attributed to Stratum 3 (below). Based on pottery finds and coins retrieved from the stratum, the channel probably dates from the latter half of the third century CE (for further details, see Uziel, Lieberman and Solomon 2017).

Dense deposits of ash, moist red clayey soil and chalk were discovered (L4304, L4310; max. thickness 2 m; Fig. 8) on a southwesterly descending slope. The deposits yielded a large quantity of organic matter. Judging by the gradient, the accumulations were probably not habitation levels but were the result of prolonged dumping of refuse. Based on the pottery found in the stratum, it probably dates from the fourth century CE (for further details, see Uziel, Lieberman and Solomon 2017).

The northern face of the northern wall of Building F that was uncovered in previous excavations was

unearthed (W4206; Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011; Onn and Weksler-Bdolah 2016). Wall 4206 (12.6 m long)

was built of dressed stones and preserved to a height of ten courses (5.2 m preserved height), including the upper

part of the wall foundation, which was wider than the wall. The foundation trench of W4206 cut into the Stratum 4

accumulations and the Stratum 5 Channel 4261 (see Fig. 3), dating Building F accordingly to not before the end of

the fourth century CE. Wall 4206 abuts the western end of the northern wall of previously excavated Building E, that

was dated to the second–third centuries CE (Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011).

Also attributed to this stratum was a channel with a trapezoidal cross-section hewn into the Western Wall stones,

which was discovered at the bottom of Course D of the Western Wall (according to Warren’s numbering; Warren 1884:

Plan XXXIII). This channel was unearthed in Warren’s eastern shaft next to the Western Wall (Wilson and Warren 1871:81),

and it continues to the northern end of Robinson’s Arch. Four rectangular hewn niches unearthed at the bottom of Course E

may possibly also be attributed to this stratum; they lie c. 3.5 m apart and were apparently used to support wooden beams.

The niches were evidently hewn in the Western Wall stones after the destruction of the Second Temple, and they may be

related to the construction of a large water reservoir to the north of the excavation area.

Pits and walls (W4244, W4246) unearthed cutting into the Stratum 4 accumulations, yielded Early Islamic pottery. These pits and walls are sealed beneath the foundations of the Stratum 1 water reservoir (‘Birkat al-Burāq’; below) and therefore predate its construction.

A plastered water reservoir was unearthed that extended across the entire excavation area (Birkat al-Burāq’; at least 15 m long, 13 m wide; Fig. 8); it was dismantled at the beginning of the excavation and hence does not appear on the plan. It was encountered directly beneath the synagogue’s stone floor. The eastern part of the reservoir may continue southward, as documented by Wilson (Wilson 1865:28–29; Bahat 2013:222–241). The reservoir was founded in the west on the western pier of Wilson’s Arch and in the east on the Western Wall. The base of the reservoir walls is curved at the junction with the floor. Two construction stages were identified in the reservoir, the earlier from the Mamluk period and the later from the Ottoman period. In the earlier phase, the reservoir was built on a thick foundation of stones and hard mortar, coated with two consecutive layers of pinkish plaster. In the later phase, the floor of the reservoir was covered with another layer of stones and bonding material, and the reservoir was coated with a new layer of pinkish plaster. Based on the traces of plaster preserved on the Western Wall, the reservoir wall after its later plastering evidently stood to a height of 3.2 m.

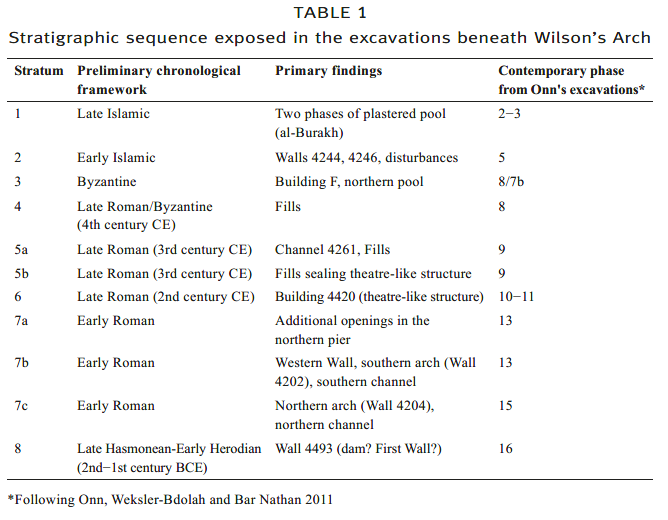

- from Uziel et al. (2019b)

Table 1

Table 1Stratigraphic sequence exposed in the excavations beneath Wilson’s Arch

Uziel et. al. (2019b)

- from Uziel et al. (2019b)

- Fig. 1 - Location map

from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map showing the area of the Temple Mount, the Great Causeway and Wilson's Arch.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 2 - Plan and Photo

of excavations from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the excavations, showing remains from Strata 8, 7 and 6a, b. Figure 2a:

- pink = Stratum 8

- green= Stratum 7C

- orange = Stratum 7B

- black = Stratum 6

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 3 - Photo of the newly

exposed section of the Western Wall beneath Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 3

Figure 3

View of the newly exposed section of the Western Wall beneath Wilson's Arch, looking east.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 4 - Drawing of the pier

of Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 4

Figure 4

View of the pier of Wilson's Arch, looking west. Numbers refer to strata as discussed in article.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 5 - Photo of Stratum 7

drainage channel from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 5

Figure 5

View of Stratum 7 drainage channel.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 9 - Section of the excavations

beneath Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Section of the excavations beneath Wilson's Arch, looking east. Numbers refer to strata as discussed in the article. Stratum 5B is not shown in the figure as it covered Strata 6

Uziel et al. (2019)

The earliest feature uncovered in the excavation is a thick wall (Wall 4493) that runs southwest to northeast (Fig. 2). The southern face of the wall is built of large, uncut boulders, and a core of smaller fieldstones mixed with hard, orange-yellow mortar. The 8 m wide wall was exposed for a length of 13 m, although it clearly extended farther to the west and to the north. Stratigraphically, the wall is sealed by Stratum 7 remains that use it as a foundation, as well as Stratum 6 Building 4420 (see below). Wall 4493 is cut by the Western Wall of the Temple Mount (Stratum 7), indicating that it precedes the Herodian platform (for further discussion on the dating of the Herodian Temple Mount, see, e.g., Shukron 2012; Patrich and Edelcopp 2015; Weksler-Bdolah 2015; Reich and Baruch 2016). The early date of this feature is also supported by its alignment, different from all Herodian and later architecture, which is oriented north−south, east−west. The seeming western extension of this feature―or at least a similar feature using this yellow mortar, has been noted in many previous excavations in the Western Wall Tunnels compound (Wilson 1880; Warren and Conder 1884; Onn, Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011; Onn and Weksler-Bdolah 2016). Warren and Conder (1884) suggested that this may be part of the First Wall, mentioned in the writings of Josephus Flavius, and dating to the Hasmonean period. Hamilton (1932, 1933) proposed that it served as the foundation of a bridge, while Bahat (2000) interpreted it as a dam. Weksler-Bdolah (2015) expanded on this idea, arguing that the proportions of the dam were very wide (Hamilton 1933 documents the width at a total of 12 m) since it also served as a major pathway leading to the Temple. Although our excavations exposed only a small portion of this wall, this is the first time that a clearly constructed stone façade was exposed, possibly supporting the theory that this may have served as a fortification wall―even possibly the First Wall, as suggested by Warren and Conder. From a chronological perspective, the initial dating of this feature to the Hasmonean−early Herodian period may be fitting. Furthermore, the orientation and location of the wall follows the line of fortification―probably the First Wall―discovered by Avigad in the Jewish Quarter (Geva and Avigad 2000: 224−225). This proposal must be treated with caution as the dating of the feature is far from certain, and since the other sections of the First Wall were not built of this orange-yellow mortar. Still, it is possible that these differences are due to changes in the topography.3

3 Both the absolute dating of the feature and its physical makeup are currently being studied by J. Regev and E. Boaretto of the Weizmann Institute.

Stratum 7 consists of several monumental and public architectural elements related to the

urban development of Jerusalem in the Early Roman period. First and foremost, the Western

Wall (Wall 4205, Figs. 2, 3) of which 8 courses were exposed (courses D−K following

Warren 1876), was attributed to this stratum. The Western Wall―part of the Herodian

platform of the Temple Mount (see, e.g., Patrich and Edelcopp 2015)―undoubtedly

dates to the Early Roman period, although recently, questions of when exactly this was

completed have been raised (Shukron 2012; Weksler-Bdolah 2015; Reich and Baruch

2016). Stratigraphically, the Western Wall cuts―and therefore postdates―Wall 4493 of

Stratum 8. At the base of Course D of the Western Wall, a cut channel, which had already

been documented by Warren, was traced; it continues to the area just north of Robinson’s

Arch. Within the channel, which is poorly executed and must represent activity later than

the construction of the wall, white plaster can be seen, indicating that it may have been

used as a conduit. In Course E, four rectangular niches were carved, which were no doubt

used as supports for wooden beams. The niches are distanced 3.5 m from each other; they

too likely date later than the Early Roman period.

On the southern end of the excavation, Course J was exposed, with two stones of the

Western Wall that were not fully carved, leaving a very rough boss; these stones were

probably intended to be buried beneath the street level of the Herodian period, as is the case

in the area of Robinson’s Arch (Shukron 2012; Hagbi and Uziel 2016). That said, Courses

J and K, discovered on the northern side of the excavation, as well as those documented

by Warren beneath Course J, were all finely carved.

The pier of Wilson’s Arch was exposed 13 m west of the Western Wall (Figs. 2, 4).

Three distinct phases were noted in the pier of the arch [A, B, and C]

This wall (4204) must initially have served as the pier for an earlier, thinner arch that either collapsed or was dismantled during the construction of Stratum 7B. The pier is 7.5 m wide and 3.5 m thick. Eleven courses were discovered, built of small, finely carved stones with fine marginal drafting. The pier was preserved to elevation 728 m, above which the Stratum 7B arch was built (see below). In this phase, a single room (4402) was built into the pier, at its centre. The room was roofed with an arch reaching 3.15 m above the floor and had a small niche in its back (western) wall. The western face of the pier served as a wall of a plastered ritual bath (miqwe—uncovered in earlier excavations; Bahat 2013: Pl. 4.03). The fact that the plaster of the miqwe, a unique cultural feature of late Second Temple Jerusalem, coats the pier indicates that it too should date to the Second Temple period. The pier is built directly upon thick Stratum 8 Wall 4493, using it as its base.

Six courses of this wall (4202) were uncovered. It has the same dimensions as its northern counterpart. A seam between the two parts of the pier is easily discernable. The southern section is built of much larger, finely cut ashlars, with no marginal drafting. These stones were also used to build the arch itself, which is supported by both the northern and southern piers. The upper courses are built on the uppermost stair of a stepped pool to its west, also dated to the Herodian period (Bahat 2013: Pl. 4.10), making it―and in turn the arch―later than this pool. Two additional rooms were built in the southern pier; one had already been discovered by Warren (Room 4405), while the second was exposed in the current excavation (Room 4404). Both rooms measure 2.4 × 1.5 m, and are built in the same manner, with a large lintel held up by two doorposts.

Two rooms were added to the northern pier. Both have niches that were carved on

either side of the doorway in order to insert a wooden lintel. The southern niche of one

lintel was carved into the southern pier, indicating that these rooms were built after the

pier already existed, making these the final stage of construction related to the arch.

The northern room (4401) measures 1.4 × 2.7 m; the southern room (4403) measures

2.3 × 2.1 m.

An additional feature that was attributed to Stratum 7 is a north to south drainage

channel, located approximately 7 m from the Western Wall (Fig. 5). The channel is

0.95 m wide and is sealed by Stratum 6 remains (see below). The southern portion of the

channel is built of ashlar masonry, similar to the drainage channel exposed farther south

in the City of David and beneath Robinson’s Arch (Shukron and Reich 2011; Szanton et

al. 2016), the northern part of the channel is cut into the mortar of Stratum 8’s Wall 4493,

and then covered with a coat of plaster.

Stratum 6, dated to the first half of the 2nd century CE, features an impressive theatrelike structure (Building 4420; Figs. 2, 6) that was built above Stratum 8’s Wall 4493 and

Stratum 7’s drainage channel. The interior of the building was semi-circular and the exterior

rectangular. It was enclosed on the east by the Western Wall, on the west by the pier of

Wilson’s arch, on the north by Wall 4451 and on the south by Wall 4430. A narrow stage

area was located on the western side of the building, with pedestals extending from

either end. The stage area was approximately 2 m wide and 10 m long, including the

pedestals. The building was entered from two aditi maximi, located north and south of

the orchestra. These 1.5 m wide passages brought audiences to two small staircases that

led up to the cavea. The orchestra was a mere 6 m in diameter, attesting to the diminutive

size of the building. This is seemingly the smallest known theatre-like structure in the

eastern Roman Empire (Segal 2000: Table; Mazor 2007b; Wiess 2014), even smaller than

the private theatre recently discovered at Herodium (Porat, Chachy and Kalman 2015).

In all, four staircases were discovered leading to the cavea―two, mentioned above at

the end of the aditi maximi, and an additional two staircases at the centre of the podium

wall (4420), separating the cavea and the orchestra. Clear signs on the staircases leading

to the cavea showed that the carving was incomplete (Fig. 7), meaning that the building

was never finished. Supporting this assumption is the incomplete molding of the cornices

of the pedestals. Most of the building’s cornices and the podium wall were carved in

stepped fashion, with no additional decoration (see, e.g., Peleg-Barkat 2017: 78−79). Such

profiles are known for example in the odeon in Beth Shean (Mazor and Amos 2007: Figs.

9.6, 9.7). Certain cornices of the building, however, were left uncarved, remaining flat,

with a triangular section. It appears that the stones were transported to the site in advance

of final carving, which would have been undertaken after they were set in place. At the

southern end of the podium wall, an incision was noted, indicating where a stone should

have been carved as a pilaster; this carving never occurred, leaving the stone unfinished.

The walls of the aditi maximi are constructed of finely cut ashlars, overlying the Stratum

8 mortar. It appears that in the entire northern half of the building, the mortar of Wall 4493

was carved and straightened to serve as the base of the orchestra and the seats of the cavea.

Here, too, it is clear that the process of construction was never completed, notably in the

stage area, where the mortar of Stratum 8’s Wall 4493 was only partially carved; a significant

portion remained uncarved and was higher than the intended height of the stage.

The use of the earlier Wall 4493 as a foundation is clearest in the area of the cavea,

where it was carved in a stepped fashion, in order to fit the stone seats that would have

been placed over it. The stone seats were not found in the excavation, save for one possible

fragment that was not found in situ.4 At the centre of the cavea foundations stood a small

wall (4409), which abuts the Western Wall, clearly indicating that the theatre-like structure

was built after the construction of the Western Wall. South of Wall 4409, heaps of large

stones created an artificial slope upon which the cavea could have been built. The heap

included architectural elements that could be attributed chronologically to the Early Roman

period, similar to those exposed near Robinson’s Arch (Peleg-Barkat 2017).

The structure found beneath Wilson’s Arch is small in comparison to other such

structures, both locally (Segal 2000; Wiess 2014) and throughout the Roman world (Sear

2006). Therefore, it is evident that the size of the audience would have been limited. That

said, there is still quite a range in the calculation of spectators (see Sear 2006: 26 for further

discussion). The width of the cavea at the centre―extending between the Western Wall and

the Podium―is 4 m. The width of the seats in a small, theatre-like structure ranges from

0.6 to 0.81 m (Sear 2006: Table 3.4). It is logical, considering other features in the building,

to assume that the seats were narrow. The negative left in the carving of the mortar of Wall

4493 measures 0.50 m, suggesting that a minimal width should be considered for the rows―

somewhere between 0.5−0.6 m―meaning the building had between 6−8 rows. If this is the

case, following Sear’s (ibid.: 27−28) equation, the capacity was between 150−200 people.

In order to date the construction of the theatre-like structure, two probes were

excavated into the foundations of the cavea.5 The vessels presented in Fig. 8 derived

from these probes. The majority of the ceramic forms are typical of the 2nd century CE.

Large basins and mortars, such as the rilled rim basin (Fig. 8: 1) or the thumb indented

mortarium (Fig. 8: 2) are typical of the legionary pottery production in the Binyanei

HaUma kilns (Magness 2005, Rosenthal-Heginbottom 2005, 2011). The cooking

cauldron (Fig. 8: 3) and jug (Fig. 8: 4) also date to the 2nd century CE. Production of

ceramic building supplies such as roof tiles, bricks and pipes began after the destruction

of the Second Temple. The foundations of the theatre-like structure yielded hundreds of

examples of ceramic building supplies such as the tegula roof tile presented in Fig. 8: 5.

A few of the roof tiles uncovered in the foundations carried legionary stamps on them.

Based on the above data as well as the negative evidence, the absence of ceramic forms

typical of the late 3rd century CE (see below, Stratum 5), this layer and consequently the

construction of the theatre-like building should be dated to the 2nd century CE.

Further supporting the dating of the structure to the period after the Roman destruction

of Jerusalem in 70 CE is the presence of architectural elements that apparently originated

from the Second Temple period Temple Mount (for the secondary use of earlier architectural

elements as building materials, see, e.g., Stiebel 2008: 222−224). Lichtenberger (2006:

293) argued that the theatre seats found near Robinson’s Arch (Reich and Billig 2000)

should be dated to the period subsequent to the destruction in 70 CE. While the relationship

between these seats and Building 4420 cannot be securely established, the moldings of

both are parallel.

4 We would like to thank B. Arubas, who noted that this fragment was in fact part of a theatre seat.

5 Beyond the ceramic data presented here, radiocarbon dating of the various strata in the excavation,

including Building 4420, was undertaken by J. Regev and E. Boaretto of the Weizmann Institute.

The results of this research― which will be published in the future, will hopefully fine-tune the

dating presented here.

A thick, uniform fill covered the entire excavation area of Stratum 5 (Fig. 9). Its matrix

was characterised by gray-brown earth with many small stones that abutted the Western

Wall and the pier of Wilson’s Arch. The fill of Phase 5b abutted circular Podium Wall

4420 of the theatre-like structure; Phase 5a sealed the structure, including the foundations

of the cavea. Small drainage Channel 4261, at the top of the fill, led from north to south,

turning westward at the southern end. The channel and the fill were cut by the foundation

trench of Building F of Stratum 3 to the south, which had been excavated earlier (Onn,

Weksler-Bdolah and Bar-Nathan 2011). The channel’s walls are built of small fieldstones

covered with flat capstones. There was no plaster in the channel; neither was there any

clearly constructed floor—only a hard, damp layer of brown sediment serving as a base.

The channel measures 0.30 m wide internally, 0.64 m wide externally and is 0.50 m deep.

The ceramic assemblages of the two phases―5b and 5a―were treated independently.

The vessel types constituting the assemblage from Phase 5b can be dated to the 2nd−3rd

centuries CE. Many of the forms are similar to the vessels produced and used in the

Binyanei HaUma workshop operated by legionary craftsmen during the Late Roman

period, until the end of the 2nd century CE (Magness 2005; Rosenthal-Heginbottom 2005).

Since several forms that appear in this assemblage were absent in the Binyanei HaUma

finds, the date of this phase should be post late 2nd century CE. The numismatic finds

and the similarities between the Stratum 5 ceramic assemblage and the one uncovered in

L.6032 of the Western Wall Plaza excavations (Rosenthal Heginbottom 2011) indicate

that Stratum 5 can be dated to the late 3rd century CE.

Numerous vessel forms occur in both Phases 5b and 5a. Several types of local bowls

(Fig. 10a: 1−3), including many rouletted bowls with varied body and rim shapes and

surface treatments (Fig. 10a: 4−5) and a number of large basins and mortaria were also

found (Fig. 10a: 6−9) The cooking vessels comprised closed and open cooking pots,

cooking cauldrons and cooking bowls (Fig. 10a: 10−12, 10b: 1). Jugs and juglets of several

forms (Fig. 10b: 2−4), kraters with thumb indention decoration (Fig. 10b: 5) and dolia

(Fig. 10b: 6) were unearthed. The typical storage jars of Stratum V exhibit an outfolded,

smoothed rim (Fig. 10b: 7−10). Very few examples from this assemblage have an inner

protrusion. The Stratum 5 lamps are ovoid with large filling holes or with a decorated disc

(Fig. 10b: 11−14). Several slipped body sherds carrying combed and printed decoration

were also found (Fig. 10b: 15).

As opposed to the ceramic assemblage of Phase 5a, the Phase 5b fill yielded no

vessel types distinctive of the 4th century CE. This may indicate that the fill layers were

deposited at different times. Still, the sloping nature of the Phase 4 fill (see below) may

have permeated the Phase 5a loci.

Many rouletted bowls with variations of rim and body shape were found in this

transition between Phase 4 and Phase 5b (Fig. 11a: 1−4). An imported African Red Slip

bowl from 5a dates to 230–300 CE (Fig. 11a: 5, Hayes 1972: 73). Large bowls, basins and

mortaria of several types were found: rilled rim, shelf rim, arched rim and cut rim basins

(Figs. 11a: 6−10, 11b: 1). Combing decoration or incised wavy lines are visible on the

rim or exterior of some examples. The cooking vessels are closed with a grooved rim or

a convex neck (Fig. 11b: 2−3); other cooking bowls have horizontal handles (Fig. 11b:

4). Storage jars with a thickened rim were found (Fig. 11b: 5) along with jars with an

outfolded rim (Fig. 11b: 6); some of the rims protruded inward (Fig. 11b: 7). Other jars

were of the Gaza (Fig. 11b: 8), dolia (Fig. 11b: 9) or holemouth types (Fig. 11b: 10); the

latter bears incised lines (letters?) on the shelf rim. The lamps from this layer were ovoid.

They had large filling holes as well as items with a decorated disc (Fig. 11b: 13−16).

Stratum 4 is characterised by a dense striation of alternating ash and chalky and red-clayey

tiers (Fig. 9). These do not represent surfaces, as they slope sharply to the southwest, and

should be interpreted as the dumps of alternate layers within the area beneath the arch.

The reasoning behind dumping of this fill is unknown.

A large pottery assemblage dating to the Late Roman period was uncovered within

these thin, stratified fill layers. Similar pottery assemblages have been published from

Mazar’s excavations near the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount (Mazar and Gordon

2007; De Vincenz 2011a, 2011b). Additional parallels derive from the Ophel excavations

(Fleitman and Mazar 2015), the Givati Parking Lot (Balouka 2013) and several contexts

in the Jewish Quarter excavations (Magness 2006, 2012).

The assemblage includes late 4th century items such as: bowls with a rouletted

decoration, presenting several rim variations (Fig. 12a: 1−2); two imported African Red

Slip bowls defined by Hayes as Type 50b dated to 350–400 CE (Fig. 12a: 3−4, Hayes

1972: 73) and Type 53b dated to the 4th–early 5th centuries (Hayes 1972: 78 – 82); rilled

rim basins, shelf rim basins and arched rim basins. Several examples carry decoration on

the body exterior (Fig. 12a: 5−8). The most frequent vessel uncovered in this assemblage

is the bowl-lid. Typically, the bowl had rounded or slightly carinated walls, a thickened

rim and a narrow ring base that was used as a handle (Fig. 12a: 9−11). The relatively

few cooking pots uncovered were all of a closed, globular form with a convex neck (Fig.

12b: 1−2). The typical storage jars from this phase had an outfolded rim, some with inner

protrusions (Fig. 12b: 3), or a thickening on the inner neck (Fig. 12b: 4−5). Other jar forms

uncovered include Gaza jars (Fig. 12b: 6), holemouth jars (Fig. 12b: 7) and wide neck

jars (Fig. 12b: 8). The representative lamps include ovoid items with large filling holes

(Fig. 12b: 9−10) and round ones with decorated discs (Fig. 12b: 11).

Stratum 3 consists of a single building (Building F) found at the southern end of the

excavation. The external, northern face of the building was exposed in an earlier excavation

farther to the west and dated to the 3rd−4th centuries CE (Onn, Weksler Bdolah and

Bar-Nathan 2011). It was interpreted as belonging to an expansion of an earlier structure

(Building E). In the current excavation, the final 5 m to the east of the northern wall of

the structure were exposed, along with its foundation trench. Stratigraphically it cuts the

Stratum 4 fills, suggesting that it cannot date earlier than the 4th century CE. Ten courses

of the building’s Wall 4206, built of fine cut ashlars and preserved to a height of 5.2 m,

were exposed. The entire length of the wall is 12.65 m, abutting the corner of Building E

(ibid.). The lower portion of the wall protrudes; the foundation is apparently wider than

the superstructure.

To the north, a large plastered pool, excavated earlier by Bahat (2013: 226−227),

belongs to this phase. The southern wall is the northern border of the current excavation.

The pool had plaster walls that did not survive but which left a mark on the Western Wall;

it occupies an area of 26 × 26 m north of Wilson’s Arch. The exact date is still unclear, as

minimal ceramic material was retrieved when it was dismantled

This stratum displays many disturbances in the Stratum 4 fills, and several unclear poorlybuilt walls. All these features are sealed by the Stratum 1 pool (see below). Pottery dating to the late Byzantine and Early Islamic period was found in the intrusions of this phase. The walls positioned at the southern (4246) and northern (4244) ends of the excavation, abut the Western Wall and Building F. Furthermore, the plaster of the Stratum 1 pool abuts the upper part of both walls, signifying that they served as outer walls of the later pool (see below).

The remains of a large plastered pool were discovered directly beneath the modern floor of the current prayer area housed beneath Wilson’s Arch (Fig. 9). This pool was partially excavated and discussed when small excavations were conducted in the southern end of the area (Bahat 1993: 38). In the current excavation, two phases of this pool were discerned. The plaster of the pool coats the pier of the arch and the Western Wall, where the negative of the plaster can be distinguished. Following this negative, the depth of the pool can be estimated as approximately 3.2 m. With the pool covering the entire area under the arch (15 × 13 m), the approximate volume of water that it could have held is 624,000 litres, although it is likely that it would not have been filled to capacity. The foundation of the earlier pool was built of large boulders and hard, concrete-like mortar, coated with two layers of thick, pinkish plaster. In a second stage, for an unknown reason, a layer of hard cement-like mortar covered this plaster and was subsequently coated with another layer of pinkish plaster. No pottery was found within the foundation and plaster of the pool, however organic material was obtained and was set aside for future radiocarbon dating. Early Islamic remains were sealed beneath the pool, meaning that it probably dates to sometime in the Late Islamic period.

- Fig. 1 - Location map

from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 1

Figure 1

Map showing the area of the Temple Mount, the Great Causeway and Wilson's Arch.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 2 - Plan and Photo

of excavations from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 2

Figure 2

Plan of the excavations, showing remains from Strata 8, 7 and 6a, b. Figure 2a:

- pink = Stratum 8

- green= Stratum 7C

- orange = Stratum 7B

- black = Stratum 6

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 3 - Photo of the newly

exposed section of the Western Wall beneath Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 3

Figure 3

View of the newly exposed section of the Western Wall beneath Wilson's Arch, looking east.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 4 - Drawing of the pier

of Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 4

Figure 4

View of the pier of Wilson's Arch, looking west. Numbers refer to strata as discussed in article.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 5 - Photo of Stratum 7

drainage channel from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 5

Figure 5

View of Stratum 7 drainage channel.

Uziel et al. (2019) - Fig. 9 - Section of the excavations

beneath Wilson's Arch from Uziel et al. (2019)

Figure 9

Figure 9

Section of the excavations beneath Wilson's Arch, looking east. Numbers refer to strata as discussed in the article. Stratum 5B is not shown in the figure as it covered Strata 6

Uziel et al. (2019)

The following discussion deals with two issues. The first is establishing the date of construction of Wilson’s Arch. As discussed above, several opinions regarding the dating of the arch have been posited. Though our excavation found no clear, unequivocal surface relating to the pier of the arch, much information was obtained that helps narrow the possibilities of its date. Three separate stages of construction can be discerned:

- The northern half of the pier was constructed in the first stage (Stratum 7C, see Fig. 4). During this stage the arch appears to have been 7.5 m wide, as evidenced by the western side of the pier. The northern half of the arch had one central opening (4402) with a vaulted roof.

- The width of the pier was doubled, supporting the wider arch during the second stage (Stratum 7B, see Fig. 4),. At this point, the arch was 15 m wide, and had two openings (4404 and 4405). These openings had an entranceway supported by a single lintel stone that resembled the openings like those of Robinson’s Arch.

- Two additional openings, breached into the existing pier, were created in the northern part of the pier (4401 and 4403, see Fig. 4) in the third and final stage, Niches were carved in order to insert what was probably a wooden beam that held the lintel stones in place.

- Fig. 3 - Section of the Great

Causeway looking north from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 3

Figure 3

The Great Causeway, section, looking north.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 13 - Plan of Strata 15

to 13 from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 13

Figure 13

Strata 15–13, plan.

Onn et. al. (2011) - Fig. 14 - Isometric reconstruction

of Wilson’s Arch interchange from Onn et. al. (2011)

Figure 14

Figure 14