Jerusalem - Nea Church

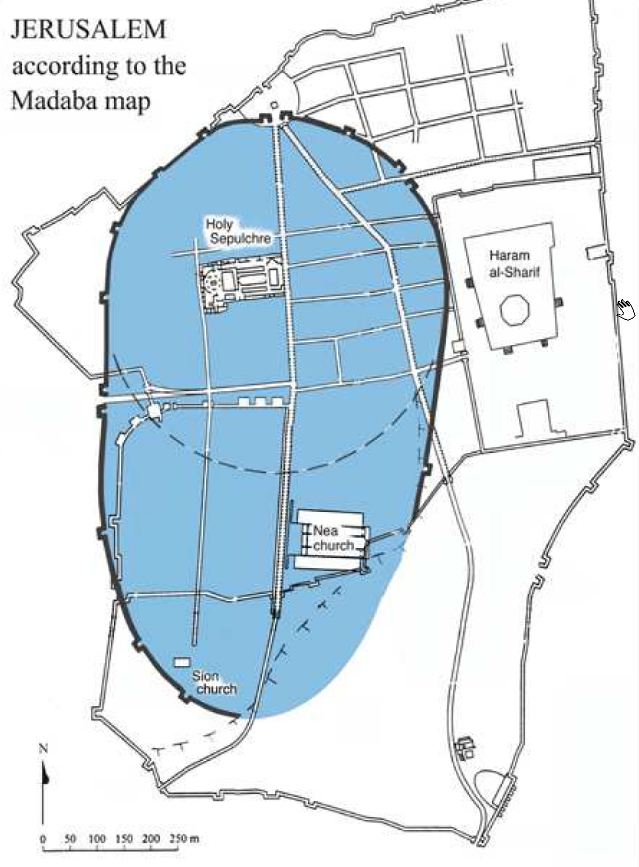

The Nea Church on the Madaba Map, showing its location along the Cardo Maximus

The Nea Church on the Madaba Map, showing its location along the Cardo Maximus Click on Image to open in a new tab

Deror Avi - Wikipedia - Public Domain

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Nea Church | ||

| New Church of the Theotokos | ||

| New Church of the Mother of God | ||

| Nea Ekklesia | Greek | Νέα Ἐκκλησία |

Commissioned by Emperor

Justinian I

and consecrated in 543 CE, the

Nea Church

(New Church of the Theotokos) was among the most ambitious

architectural achievements of Byzantine Jerusalem.

Situated at the southern end of the city’s

Cardo Maximus, the immense basilica rose on a vast substructure

of vaults and piers built into the slope of Mount Zion.

The Nea stood as a monumental expression of Justinian’s imperial

authority and Christian devotion. Intended to rival the

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

and the

Hagia Sion, it formed part of a large complex including a

monastery, hospice, and hospital. Measuring roughly 100 × 52 m,

it was one of the largest churches in the eastern Mediterranean

and dominated Jerusalem’s southern skyline.

The building suffered damage during the Persian invasion

of 614 CE and later from neglect and seismic activity. By the

early 10th century CE, it lay in ruin. Excavations in the 1970s by

Nahman Avigad in the Jewish Quarter uncovered its vaulted substructure, apse,

and foundations, definitively locating the church and revealing

the scale of Justinian’s project.

- Fig. 2 Plan of Jerusalem

as shown on the Madaba Map showng Nea Church from Whitcomb (2011)

- Fig. 2 Plan of Jerusalem

as shown on the Madaba Map showng Nea Church from Whitcomb (2011)

- Excerpts from McCormick (2011:199-217)

| In sancta Maria Noua quad Iustinianus imperator extruxit, xii; in sancta Tathelea i; in sancto Georgio ii; in sancta Maria, ubi nata | fuit, in Probatici v, inclusas Deo sacratas xxv; in sancto Stephano, ubi scpultus fuit, clerici leprosi xv.

... The church of St. Mary,70 which the earthquake ruined | and sank into the earth, measures on both sides 3471 dexters in length, on one extremity 3[5]72; | through the middle, across, 32; in length, through the middle, 50. The church in Bethlehem:73 in length, 38 dexters; | on the upper74 extremity, at the transept, 23; on the other extremity, 17; 69 columns. The church of the Sepulcher | of the Lord:75 around, 107 dexters; the dome, 53; from the Holy Sepulcher up to Holy Calvary, 27 dexters; | from Holy Calvary to where the Holy Cross was discovered,76 19 dexters; including the Holy Sepulcher and Holy Calvary and Holy | Constantine: their roof altogether is 96 dexters in length, 30 across. The church of Holy Zion77 is | 39 dexters in length; 26 across.

Ipsa ecclesia sanctae Mar[i]ae quod | cula cxcv; ille terrae motus f[regit] | et in terram demersit, habet mensuram de ambobus lateribus in longe dexteros xx[x]*iiii, in uno fronte xxx[v]; | per medium in aduerso, xxxii; in longo per medium |. ...

1 For the Nea Church of St. Mary, see map 1. See also Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 332, under “New St. Mary.” The Basel Roll offers

the last mention of this shrine. Bieberstein and Bloedhorn (Jerusalem:

Grundzüge der Baugeschichte, 2:191–97) assess its situation about 808

very optimistically. For the great shrine’s dimensions as revealed by the

Basel Roll, see below, lines 50–52, and above, chapter 5.2.

2 Holy Land topographers universally correct saint “Tathelca” to

“Thalelacus,” whose monastery Justinian “renewed” (Procopius, Aedificia 5.9.1, 4:169.9–10) and which a liturgical feast seems to locate on

Zion. See Bieberstein and Bloedhorn, Jerusalem: Grundzüge der

Baugeschichte, 3:42.2; compare Milik, “Notes d’épigraphie, IX,” 360–61,

no. 9. Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, has no gazetteer entry for

“Thaleleus” (as he writes it), but see ibid., 353, under “Sion.” This

appears to be the last mention of this church.

3 Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 304, under “George, St. in

Jerusalem”; J. T. Milik, “La topographie de Jérusalem vers la fin de

l’époque byzantine,” Mélanges de l’Université Saint-Joseph 37 (Beirut,

1960–61): 127–89, at 138–41; Milik, “Notes d’épigraphie, IX,” 567–68.

This seems to be the last mention of this church.

4 Map 1. See Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 346–48, “Sheep Pool”;

Bieberstein and Bloedhorn, Jerusalem: Grundzüge der Baugeschichte,

3:167–68, where this is identified as the last mention of this shrine;

compare Milik, “Notes d’épigraphie, IX,” 363; and Külzer, Peregrinatio

graeca, 2.18–19; see also Aisc, Christian Topography, 150–54.

5 The shrine of St. Stephen’s tomb lay a few hundred meters north of

the city wall. See map 1 and Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 318; and

Bieberstein and Bloedhorn, Jerusalem: Grundzüge der Baugeschichte,

1:227–37. This is the final mention of this shrine (ibid., 292).

70 The great Nea Church built by Justinian and rediscovered in 1970.

See above, chapter 5.2, for this building and the significance of the

roll’s evidence about this and the following buildings.

71 Latin “dexteros xx[x]iiii.”

72 See chapter 11, the textual commentary for the reading.

73 That is, the Nativity church, already mentioned above. See lines 25–26,

and the discussion of this passage, above, chapter 5.2.

74 “Upper” here is used in the familiar Latin sense of “eastern,” which

derived from the fashion in which the ancients imagined, and usually

depicted, space: the surest direction, before the invention of the

compass, the one in which the sun rose, was depicted at the top of the map.

75 See above, lines 3–8, and discussion of this evidence, above, chapter 5.2.

76 That is, the apse of the Constantinian basilica. See above, chapter 5.2,

with note 72.

77 See above, line 9, and discussion of this evidence, above, chapter 5.1.

- Excerpts from McCormick (2011:234)

de Rossi did not detect the f and so suggested quassauit or a similar verb; Tobler and Molinier proposed "[euertit]". The first letter was clear to me and excludes both suggestions. Frango seems the best choice (cf. ThLL 6.1:1242.3-6).

- from Watson (1913:23-24)

Tobler has given an exact copy of the original manuscript with its abbreviations and omissions, accompanied by an extension of the same in Latin, and an excellent commentary in German, in which he endeavours to elucidate certain points which are difficult to understand. He goes thoroughly into the question of the date of the document, and shows from internal evidence that it was probably written about the year A.D. 808. The manuscript which he used is preserved in the public library at Bale in Switzerland, and the writer appears to have been a monk sent to the Holy Land during the reign of the Emperor Charlemagne, to collect information with regard to the Christian establishments in that country, possibly for the use of the emperor himself.

Charlemagne, as is well known, was on good terms with the Khalif Harun er-Rashid, then reigning at Bagdad, with whom he had made a treaty of friendship, and who allowed him to repair the churches in Jerusalem, and to build a new church, known as St. Mary Latina, to which a hospice was attached for the use of Latin-speaking pilgrims to the Holy City.

In the original manuscript of the Commemoratorium there appears to have been no division between paragraphs, the writing running on from line to line without a break; but in the following translation I have divided the matter in a form more convenient for reference, and have numbered the paragraphs so divided, in order to be able to refer to them in some notes which I have added to elucidate the text. These notes, which might be largely extended, deal only with the churches in and close to Jerusalem. Where numbers occur in the text I have put Arabic figures in place of the Roman characters in the original, as they are easier to read.

- from Watson (1913:24-28)

2. In the first place, there are at the Holy Sepulchre of the Lord, 9 priests, 14 deacons, 6 sub-deacons, 23 canons, 13 guardians who are called fragelites, 41 monks, 12 persons who walk before the patriarch with tapers, 17 servants of the patriarch, 2 overseers (praepositi), 2 accountants (computarii), 2 notaries, 2 priests who diligently watch over the Sepulchre of the Lord.

3. There is one priest at Holy Calvary; at the place of the Cup of the Lord, 2 priests; at the place of the Holy Cross and of the Napkin, 2 priests and one deacon.

4. There is a seneschal (syncellus) who keeps all things in order under the patriarch, 2 stewards (cellarii), one treasurer, one guardian of the cisterns (fontes), 9 porters. The total number is 150, 3 hospitallers (hospitalibus) being excepted.

5. At Holy Sion there are 17 priests and clerks (clericos), 2 cloistered monks dedicated to God being excepted.

6. At the church of St. Peter, where he wept, there are 5 priests and clerks. At the praetorium there are 5 priests.

7. At the new church of St. Mary, which the Emperor Justinian built, there are 12 priests.

8. At St. Thalalaeus there is one priest; at St. George 2 priests.

9. At the church of St. Mary, where she was born in the Sheep Pool, there are 5 priests and 25 cloistered nuns.

10. At St. Stephen, where he was buried, 2 clerks and 15 lepers.

11. In the Valley of Jehoshaphat, at the garden which is called Gethsemane, where St. Mary was buried and where her sepulchre is revered, 13 priests and clerks, 6 monks, and 15 nuns, including those cloistered and those serving.

12. At St. Leontius there is one priest; at St. James one priest; at St. Quaranta 3 priests; at St. Christopher one priest; at St. Aquilina one priest; at St. Quiriacus one priest; at St. Stephen 3 priests; at St. Dometian one priest; at the place where St. John was born, 2 priests; at St. Theodore 2 priests; at St. Sergius one priest; at the place where St. Cosmas and Damian were born, 3 priests, and at the place where they begged, one priest.

13. On the Holy Mount of Olives there are three churches: one at the place of the Ascension of the Lord, where there are 3 priests and clerks; the second, at the place where Christ taught his disciples, where there are 3 monks and one priest; the third, built in honour of St. Mary, where there are 2 clerks.

14. The numbers of recluses who sit in their cells are as follows: 11 who chant in Greek; 4 Georgians; 6 Syrians; 2 Armenians; 5 Latins; one who chants in the language of the Saracens. Near the step where you go to the Holy Mount are 2 recluses, one Greek and one Syrian; at the highest step by Gethsemane, there are 3 recluses, one Greek, one Syrian, and one Georgian.

15. In the Valley of Jehoshaphat there is one recluse and a convent of 26 nuns.

16. There are 17 nuns who serve at the Sepulchre of the Lord by command of the Emperor Charles, and one Spanish cloistered nun.

17. In the monastery of St. Peter and St. Paul, in Bisantium, near the Mount of Olives, there are 35 monks. At St. Lazarus in Bethany there is one priest. At St. John, which belongs to the Armenians, 6 monks.

The above are all in Jerusalem and its vicinity, within one mile or thereabouts.

A list of those monasteries which are at some distance from Jerusalem, in the Promised Land

18. At Holy Bethlehem, where Our Lord Jesus Christ condescended to be born of the Holy Virgin Mary, there are 15 persons, including priests, clerks, and monks, and 2 recluses who sit on pillars in imitation of St. Simon.

19. In the monastery of St. Theodosius, which was the first built in that wilderness, there are 70 monks; Basil was buried there. The Saracen robbers burnt that monastery and killed many monks there; others fled to escape from the pagans, who destroyed two churches belonging to the monastery.

20. In St. Saba there are 150 monks.

21. In a small monastery, built by St. Chariton, where he rests in holiness at the distance of a mile (ubi ipse sanctus ab uno milliario requiescit), an abbot named — and — monks. (The name and number are obliterated.)

22. At St. Euthymius 30 monks.

23. At the monastery of St. Mary, in Coziba, there is an abbot named Laetus, and — monks (number obliterated).

24. At the monastery where St. John baptized, there are 10 monks. St. Gerasimus built it and is buried there. He built the church and gave it its name.

25. At the monastery of St. John by Jordan, where the pilgrims descend into the river, there is another church and 35 monks.

26. There is a monastery of St. Stephen near Jericho, and a monastery (name obliterated) in Mount Pharan. I do not know how many monks there are in these two.

27. In Galilee, in the Holy City of Nazareth, there are 12 monks. A mile from Nazareth, at the place where the Jews tried to cast down the Lord Christ, a monastery and church have been built in honour of St. Mary, and there are 8 monks.

28. In Cana of Galilee, where the Lord turned the water into wine, there are — monks (number obliterated).

29. On the Sea of Tiberias there is a monastery called that of the seven fountains (heptapegon), where the Lord fed five thousand people with five loaves and two fishes: here there are 10 monks.

30. Near the Sea is a church called that of the Twelve (several words are obliterated); there is the table where He sat with them; there are one priest and 2 clerks.

31. In the city of Tiberias, Theodore is bishop, and there are 30 clergy, including priests, monks, and canons; there are 5 churches and a convent of nuns.

32. In Holy Mount Tabor, Theophanes is bishop and there are 4 churches: the first in honour of Our Saviour, where He talked with Moses and Elias; the second that of St. Moses; the third that of St. Elias; the fourth (name omitted). There are 18 monks.

33. In Sebastia, where the body of St. John was buried, there was a large church which is now in ruins; but his tomb is in a part which has not fallen, and there is a church at the place where he was imprisoned and beheaded. Basil is bishop, and there are 25 clergy, including priests, monks, and clerks.

34. In Shechem, which is called Neapolis, there is a large church where the woman of Samaria is buried, and other churches; there is a bishop and clerks, and a recluse upon a pillar.

35. At Holy Mount Sinai there are 4 churches: the first at the place where God talked with Moses on the top of the mountain; the second of St. Elias; the third of St. Elisha; and the fourth in the monastery of St. Mary. Elias is the abbot and there are 30 monks. The number of steps (gradicula) going up or down the mountain are 7,700.

36. Where you descend from Jerusalem into the Valley of Jehoshaphat, to the place of the tomb of St. Mary, you have 195 steps, and to ascend to the Mount of Olives, 537 steps.

37. The church of St. Mary, which was damaged by the earthquake, has a measure in length from both wings of 39 dextri; in one front 35 dextri; across through the middle 32 dextri; in length through the middle 50 dextri.

38. The church of Bethlehem has a length of 38 dextri; in the greater front in that cross 23 dextri; in the other front 17 dextri; it has 69 columns.

39. The church of the Holy Sepulchre is 107 dextri in circuit, and the dome 54 dextri.

40. From the Holy Sepulchre to Holy Calvary is 28 dextri, and from Holy Calvary to the place where the Cross was found is 19 dextri.

41. Including the Holy Sepulchre and Holy Calvary, and the Holy Church of Constantine, the space covered by them all has a length of 96 dextri and a width of 30 dextri.

42. The Church of Holy Sion has a length of 39 dextri and a width of 26 dextri.

43. The amount expended annually by the patriarch for priests, deacons, monks, clerks, and the whole of the ecclesiastical body is 630 solidi; for — (obliterated) 550 solidi; for the maintenance of the church buildings 300 solidi; for the Saracens 580 solidi. (Parts of the two last lines are illegible.)

- from Watson (1913:28-33)

Then, westwards of this chapel was the church on Calvary, and between the two was a place where the Cup of the Lord was kept. West of Calvary again was the round church of the Holy Sepulchre, which, at that time, had three enclosures round the Tomb; the first, that now represented by the circle of square columns which support the dome; the second, the wall with three apses, which still exists; and the third, an exterior circular wall, which has nearly disappeared, but of which Dr. Schick found some portions remaining, between the Holy Sepulchre and the rock scarp to the west.1 The fourth church shown on the sketch, that of St. Mary, which stood on what is now the courtyard in front of the church of the Holy Sepulchre, no longer exists, and, as it is not mentioned in the Commemoratorium, it may have been removed previous to the date of that document.

In the following notes the numbers are the same as those of the paragraphs of the translation:—

2. The church of the Holy Sepulchre had naturally the largest number of clergy attached to it, and is mentioned first, with the chapels adjoining it. The writer then enumerates the churches inside the city, and afterwards those outside the walls, commencing with the church of St. Stephen, and going on to the Valley of the Kedron and the Mount of Olives.

3. The Cup of the Last Supper is first mentioned in the Breviary, a document believed to have been written early in the sixth century, and was, at that time, kept in a chamber in the great basilica of Constantine with the Reed and the Sponge of the Crucifixion. Antoninus, who visited Jerusalem about A.D. 570, mentions these relics and gives the further detail that the Cup was made of onyx. But, when Arculfus made his pilgrimage about A.D. 670, after the destruction of the basilica by the Persians, the Cup was shown in a recess near the chapel of Calvary, and was made of silver. Perhaps the onyx cup was carried off by the Persians and not recovered. The Napkin of the Lord is first mentioned by Arculfus, who tells an interesting story of the manner in which the Christians recovered it from a Jewish family, who had preserved it since the time of the Crucifixion.2 These relics, the Cup, the Sponge, the Reed, and the Napkin, are not mentioned by Bernard, who visited Jerusalem about A.D. 870, nor by Saewulf, who made his pilgrimage in A.D. 1102, just after the capture of the city by the Crusaders.

4. It is curious that, in the Commemoratorium, the total number of clergy and employés is given as 150, whereas they add up to 163. Perhaps some of the figures, which are in Roman characters, have been incorrectly copied. I am not sure what the 3 hospitales were, whether guests or attendants.

5, 6. The question of the churches on Sion is rather a complicated one, and, as I have already discussed it in the Quarterly Statement,3 it is unnecessary to repeat the information already given.

7. This statement that there were 12 priests serving in the new church of St. Mary, built by the Emperor Justinian, would seem to be a conclusive proof that this church could not have been at or near the site of the Mosque of Aksa, as commonly supposed. At the beginning of the ninth century the Mahomedans were in the height of their power, and Christians were rigidly excluded from the Haram enclosure. The reasons for believing that Justinian’s church was on the south part of Sion have been given in a paper which I contributed to the Quarterly Statement in 1903,4 and this paragraph in the Commemoratorium appears to be a confirmation of the arguments which I put forward. So far as I am aware none of the writers who uphold the Aksa site for the church have referred to it, and it would be interesting to know how they would explain it.

8. The monastery of St. Thalalaeus is mentioned by Procopius as one of those which the Emperor Justinian restored in Jerusalem. I cannot find where it was situated. The only other mention of a church of St. George in Jerusalem, before the time of the Crusaders, is in the Arabic document descriptive of the capture of the city by the Persians which was commented on by Monsieur Clermont-Ganneau in the Quarterly Statement.5 It is stated therein that seven Christians were murdered at the altar of St. George.

9. The church of St. Mary, at or near the site of the present church of St. Anne, north of the Haram, and close to Bethesda, or the Sheep Pool, is first mentioned early in the sixth century. Theodosius (A.D. 530) says: “Near the Pool of the Sheep Market is the church of St. Mary.” Antoninus (A.D. 570) relates that “he came to a swimming pool, which has five porticoes, and in one of them is the basilica of the Blessed Mary, in which many miracles are wrought.” Arculfus (A.D. 670) and Willibald (A.D. 754) do not mention the church at all. Then comes the Commemoratorium (A.D. 808) which says: “St. Mary, where she was born in the Sheep Pool.” From this it would seem that the church was actually in the Pool. It is curious that the next pilgrim who has left an account of his travels, Bernard (A.D. 870), does not mention the church of St. Mary by the Sheep Pool, and places the birth-place of St. Mary by the Garden of Gethsemane, “where there is a very large church in honour of her.” At some time before the Crusaders captured Jerusalem, the name of the church near the Sheep Pool had been altered from St. Mary to St. Anne, for Saewulf, who visited the city in A.D. 1102, says: “From the Temple of the Lord you go towards the north to the church of St. Anne, the mother of Blessed Mary, where she lived with her husband. There also she brought forth her most beloved daughter Mary, the saviour of all the faithful. Near there is the Probatica Pool, which is called in Hebrew Bethsaida, having five porches.”

10. This would seem to have been the church of St. Stephen, outside the Damascus Gate. It was apparently a small church built near the ruins of the great basilica, erected by the Empress Eudocia, and destroyed by the Persians.

11. The church of the tomb of the Virgin has never altered its position since it was first built in the fifth or sixth century. It is first mentioned by Theodosius (A.D. 530) and is described at considerable length by Arculfus (A.D. 670).

12. Next follows a list of chapels and monasteries in the Valley of the Kedron, where they were always numerous. Theodorus (A.D. 530) says that there were 24 churches, and Antoninus (A.D. 570) “visited many monasteries and places where miracles had been performed, and beheld a multitude of men and women living as recluses on the Mount of Olives.” But the numbers appear to have considerably reduced, probably by the massacre of Christians by the Persians in A.D. 614.

13. Three churches are enumerated as being on the Mount of Olives. The first of these, that of the Ascension, was probably on the same site as at present; the second, that at the place where Christ taught his disciples, may have been the successor of the basilica built by the Empress Helena, which, as Eutychius states, was destroyed by the Persians; the third church, that of St. Mary, has, so far as I know, disappeared. It is first mentioned by Theodorus (A.D. 530), and, according to Procopius, was restored by the Emperor Justinian. Antoninus (A.D. 570) apparently refers to it as “the basilica of the Blessed Mary, which they say was her house”; and Bernard (A.D. 870) distinguishes it carefully from the church of the Tomb of the Virgin, saying: “going forth from Jerusalem we descended to the Valley of Jehosophat, distant a mile from the city, containing the Garden of Gethsemane, with the birth-place of St. Mary, where there is a very large church in honour of her. In the garden also is the round church of St. Mary, where is her sepulchre, which, having no roof over it, stands rain badly.” I can find no mention of the church later than this. Father Vincent thinks that it may have been on the Karm es-Sayad, that part of the summit of the Mount of Olives, north of the church of the Ascension, on which the house of the Greek bishop of Jericho stands, and where many fragments of Byzantine work have been found, but it is rather difficult to reconcile this with Bernard’s statement that it was near the Garden of Gethsemane. I think that, for the present, we must regard the question of St. Mary on the Mount of Olives as one of the problems respecting Jerusalem churches which have yet to be solved.

15. This convent of nuns is mentioned by Theodorus (A.D. 530), who says that it was in the Valley of Jehoshaphat under the pinnacle of the Temple, and that the nuns were never allowed to go out. “When one of them goes from earth, she is placed in the monastery itself, and those who enter, while they live, they do not go forth thence. When anyone would be admitted to vows, and for a penitent, then only are the doors opened, for they are ever shut in. They receive food from the wall, and water from a cistern, which they have within.”

17. Bisantium has not been identified. Tobler suggests that it may be Bethphage, but, at all events, it was somewhere on the road from Jerusalem to Bethany.

37. I do not propose to discuss the churches and monasteries in other parts of Palestine and will go on to paragraphs 37–42 which give the dimensions of certain churches. These dimensions are recorded in dexters, a measure not very well known, and respecting which there is an interesting article in Du Cange’s Glossary of Mediaeval Latin.6 He does not give a length for the dexter, and states that it was the ecclesiastical pace, used in connection with church measures. From the dimensions in the Commemoratorium it appears to have been about equal to the Roman pace of five Roman feet. As the Roman foot was 11.65 British inches, this pace was 1.85 British feet. It is best first to take the church at Bethlehem, the dimensions of which have, most probably, not altered since the ninth century.

38. Here the length of the church of Bethlehem is given as 38 dexters, the breadth in the cross, apparently meaning the transept, as 23 dexters, and the other breadth as 17 dexters. The actual lengths are length of church from west to east, 177 British feet; width across transept 118 feet; width across nave 86 feet. These give, for the corresponding lengths in dexters, 4.66 feet, 5.13 feet, and 5.06 feet as the length of the dexter. The mean is 4.88 feet, which is very near the length of the Roman pace.

39. These dimensions are more difficult, as we do not know how the writer took his measures, whether with a tape or by pacing. But if we take the outside wall, as shown on the sketch by Arculfus (p. 28), of which the remains were found by Dr. Schick, the length of the circumference would be 490 feet, which gives the length of the dexter as 4.58 feet. Also, if we take the width of the then existing dome as being the same as the outside of the present circle of columns, the length of the circumference would be 252 feet, giving a dexter of 4.66 feet.

40. The actual distance from the tomb to the centre of Calvary is 132 feet, which, divided by 28, gives a dexter of 4.71 feet; and the distance from Calvary to the entrance of the chapel of St. Helena is 92 feet, which, divided by 19, gives a dexter of 4.84 feet.

41. The length of the area occupied by the churches of Constantine may be taken as extending from the west side of the church of the Holy Sepulchre to the remains of columns west of the street called Khan ez-Zeit, i.e., 472 feet. Dividing this by 96 we get 4.88 as the length of the dexter. The width of the area varies, but may be taken as about 150 feet, which gives a dexter of 5 feet.

37. To return to paragraph 37. The writer has mentioned four churches of St. Mary, i.e., the church at the Sheep Pool, the church of the tomb of St. Mary, the church of St. Mary on the Mount of Olives, and the new church built by the Emperor Justinian. The church that was damaged by the earthquake was probably one of the two latter. The dimensions of it, as given, are hard to understand. The Latin words are: “Ecclesia Sancta Maria habet mensuram de ambobus lateribus in longo dexteros XXXVIIII, in una fronte XXXV, per medium in adverso XXXII, in longo per medium L.” The church was evidently very large, larger than the church of Bethlehem.

38. The dimensions of the church of Sion, on the contrary, are simple. It had a length of 39 dexters, or about 180 feet, and a width of 26 dexters, or about 126 feet.

Looked at as a whole, the Commemoratorium is a very interesting document, and one worthy of careful study. I do not feel certain as to the exact meaning of some words and sentences, and would be obliged by criticism on the translation.

1. See "Plan of Church of Holy Sepulchre" in

Quarterly Statement, 1898, p. 145.

2. See Palestine Pilgrims' Texts, Vol. III,

"Arculfus," p. 12.

3. See Quarterly Statement, 1910, p. 196,

"The Traditional Sites on Sion."

4. See Quarterly Statement, 1903, pp. 250, 344,

"The Site of the Church of St. Mary at Jerusalem,

built by the Emperor Justinian."

5. See Quarterly Statement, 1898, p. 36,

"The Taking of Jerusalem by the Persians in A.D. 614."

6. Glossarium Mediae et Infimae Latinitatis,

by C. Du Fresne, Seigneur Du Cange, Vol. II,

Article "Dextri."

The excavations in the Jewish Quarter also revealed remains of the 'New Church of the Holy Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary,' commonly known as the 'Nea Church.55 The church, depicted on the Madaba Map, was one of the most significant building ventures undertaken by Emperor Justinian I and therefore played a central role in Christian Jerusalem.56 The final days of the Nea Church have not yet been fully studied. The pottery from the areas within the church clearly shows continuation of the church throughout the Umayyad period,57 but found its end sometime during the Abbasid period.58 Different dates are suggested for the church's discontinuation: N. Avigad indicated that it was destroyed by an earthquake in the eighth century AD.59 D. Bahat, on the other hand, suggested an earthquake in AD 846, although he also suggested the possibility that the church was destroyed during the earthquake of AD 749.60 These assumptions about the church being damaged in the earthquake are based on account of the Commemoratorium de casis Dei — written in the ninth century: “The Church of St Mary which was thrown down by the earthquake and engulfed by the earth has side walls 39 dexteri long.”61 The Nea Church is the only church mentioned in this source as having suffered damage from the earthquake — no other churches were mentioned.

But in contrast to the textual evidence, no actual archaeological evidence was recorded indicating any impact of the earthquake. Following the types of possible seismic damage by S. Marco,62 it can be assumed that there is archaeological evidence for the earthquake in the Nea Church: a published photograph of the site63 shows the height difference which can be seen in different parts of the church's marble pavement — some parts that were not supported by a wall running below it are located 0.10 m lower than other parts.64 Additionally, it must be noted that most of the marble slabs were broken, which may perhaps hint at seismic damage.65 But the suggestions remain merely assumptions, as no other evidence for this can be retrieved.

55 Gutfeld 2012b, 141.

56 Gutfeld 2012b, 141.

57 Areas D and D-1; Avissar 2012, 311-12; Although the

stratigraphy published in the excavation report does not

subdivide the Early Islamic phases further (Gutfeld 2012b,

149, 215).

58 Gutfeld 2012a, 10.

59 Avigad 1977, 145.

60 Bahat 1996, 59.

61 Commemoratorium de casis Dei, p.138.

62 Marco 2008.

63 Gutfeld 2012b, 174, ph. 5.26 (L.2191 is located higher than

L.2199; Gutfeld 2012b, 176).

64 Gutfeld 2012b, 174.

65 Gutfeld 2012b, 224; Marco 2008, 151–52.

| Effect | Location | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Nea Church |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nea Church |

|

|

Avigad, N. (1977) ‘A Building Inscription of the Emperor Justinian and the Nea in Jerusalem’, Israel Exploration Journal, 27: 144-51.

Avissar, M. (2012) ‘Pottery from the Early Islamic to the Ottoman Period from the Cardo and the Nea Church’

, in O. Gutfeld (ed.), Jewish Quarter Excavation in the Old City of Jerusalem Conducted by Nahman Avigad, 1962-1982, v (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society), pp. 301-45.

Avni, G. (2014) The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Bahat, D. (1996) ‘The Physical Infrastructure’, in J. Prawer and H. Ben-Shammai (eds), The History of Jerusalem: The Early Muslim Period (639-1099) (New York: New York University Press), pp. 38-101.

Bijovsky, G. and Berman, A. (2012) ‘Coins from the Cardo and the Nea Church’, in O. Gutfeld (ed.), Jewish Quarter Excavation in the Old City of Jerusalem Conducted by Nahman Avigad, 1962-1982, v (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society), pp. 346-77.

Commemoratorium de Casis Dei in Descriptiones Terrae Sanctae ex saeculo VIII, IX, XII et XV by Titus Tobler (1874) - open access at archive.org

McCormick, M. (2011). Charlemagne’s Survey of the Holy Land: Wealth, Personnel, and Buildings of a Mediterranean Church between Antiquity and the Middle Ages

. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Namdar, L., Zimni, J., Lernau, O., Vieweger, D., Gadot, Y. and Sapir-Hen, L. (2024) ‘Identifying Cultural Habits and Economical Preferences in Byzantine and Early Islamic Mount Zion, Jerusalem’, Journal of Islamic Archaeology, 10.2: 175-94.

Watson, C. M. (1913) “Commemoratorium De Casis Dei Vel Monasteriis,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 45 (1913): 23–33

Tsafrir, Y. (2000) Procopius and the Nea Church in Jerusalem. An Tard 8: 149-64.

Whitcomb, D. (2011) 'Jerusalem and the Beginnings of the Islamic City'

, in K. Gator and G. Avni (eds), Unearthing Jerusalem: 150 Years of Archaeological Research in the Holy City

(Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns), pp. 311-30.

Zimni, J. (2023) 'Urbanism in Jerusalem from the Iron Age to the Medieval Period at the Example of the DEI Excavations on Mount Zion'

(unpublished doctoral thesis, Bergische Universitic Wuppertal)

Zimni-Gitler, J. (2025) Chapter 10. Traces of the AD 749 Earthquake in Jerusalem: New Archaeological Evidence from Mount Zion

, in Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749,

Brepolis