Jerusalem - Mount Zion

View of Mount Zion and Dormitio Church from the Mount of Olives

View of Mount Zion and Dormitio Church from the Mount of OlivesClick on Image for high resolution magnifiable image

Berthold Werner - Wikipedia - Public Domain

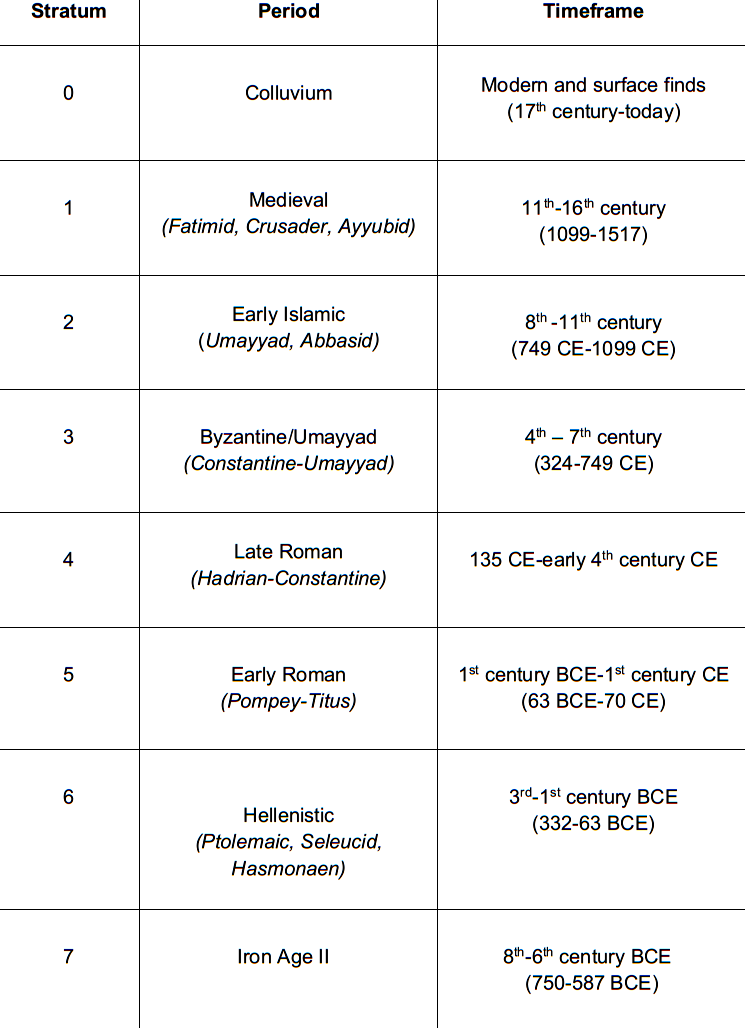

Mount Zion is a hill in Jerusalem located just outside and to the south of the current Ottoman walls of the Old City. The name can be historically confusing as Mount Zion used to be the name for the eastern hill of the Old City with modern day Temple Mount lying on its summit. Excavations in the area of the modern "Mount Zion" have revealed remains as early as Iron Age II (Hillel Geva in Stern et al, 1993).

Sacred for Jews, Christians, and Muslims, Mt Zion was visited by many pilgrims and western travellers (Röhricht 1890; Ish-Shalom 1965). Its first association with religious traditions was probably made by the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela (c. 1165-73) in the twelfth century claiming that the complex hosts the graves of several Jewish kings (Asher 1927).5 In the thirteenth century, after the Mamluks conquered Jerusalem, religious disputes concerning the ownership of the complex emerged (Praver 1947-48) and lasted, although not continuously, for nearly 300 years. Fabri reported that towards the end of their rule over Palestine, the Mamluks decided to ruin the existing Christian Church and convert the lower vault of the complex into a mosque (Fabri 1480–83, 301–305). The Ottomans, who defeated the Mamluks in 1517 and took over Palestine, continued the Islamic construction in the complex and in 1524 converted also the upper hall into a second mosque. The exact construction date of the al-Nabi Da’ud minaret, however, is not explicitly mentioned in the sources but by virtue of its design it looks typical of Ottoman architecture (Alud and Hillenbrand 2000, 659).

In order to prevent Christians from visiting the complex, in the sixteenth century the Ottoman sultan put the care and treatment of the whole complex in the hands of the Dajani family, one of the families in Jerusalem closely associated to him (Layish 1985). They took over complete responsibility of the complex but did not reside within it; they used an external building close to the southern wall of the Old City for their needs (Ben-Arieh 1979). Under their surveillance, only Muslims were allowed to enter. The western travellers Richard Pocoke in 1738 and Frederick Hasselquist in 1751 described the sepulchre as including a mosque and also a minaret (Hasselquist 1766, 123; Pococke 1745, 9). Turner, who visited Jerusalem in 1815, briefly described the complex, but probably from the outside without entering it (Turner 1820, 194) while Bartlett managed to sneak into it in order to visit the sepulchre (Bartlett 1844). None of these or other reports mentions damage to the minaret or repairs that were carried out between 1800 and 1850. An interesting description is provided by Seetzen, who visited the site in 1860. He noted that despite being partly ruined, the mosque of al-Nabi Da’ud is the most prominent mosque outside the walls of Jerusalem (Seetzen 1854– 59). This report is unique, being the only written source from the middle of the nineteenth century implying that perhaps the prominence of the mosque was because of high minaret.

5 The itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela took place sometime between c.1165-73 and included Europe, the Middle East and northern Africa.

Because the 1st century CE historian Josephus mistakenly identified a structural high sometimes called the western hill southwest of what is now the old city of Jerusalem as the Mount Zion of King David's time, this area in the modern city of Jerusalem is currently called Mount Zion. Nearby, close to the Jaffa Gate, is a structure known as the Tower of David or the Citadel. Neither the western hill (mistakenly called Mount Zion) or the Citadel (mistakenly called the Tower of David) bear any relation to the Mount Zion or the Tower of David from the time of King David.

- from Jerusalem - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Fig. 1 The Old City of Jerusalem

and the King David Sepulchre complex from Zohar et al (2015)

Figure 1

The Old City of Jerusalem and the King David Sepulchre complex (outlined in orange and also in the inset). Major structures and minarets within the area include:

- Dormition Church

- the King David Sepulchre complex

- al-Nabi Da’ud minaret

- Greek-Orthodox cemetery

- Protestant cemetery

- Armenian church of the House of Caifas

- Zion Gate

- David Citadel with the al-Qal’a minaret

- Jaffa Gate

- ‘Hurva’ synagogue

- al-Omari minaret

- Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- al-Jami Omar mosque and minaret

- al-Hanaqah mosque and minaret

- al-Fakhriyya minaret

- Bab al-Silsila minaret

- al-Aqsa mosque

- al-Ghawanima minaret

- Bab al-Asbat minaret

- al-Hamra mosque and minaret

- al-Maulawiyya mosque and minaret

- Damascus Gate

- Church of the Ascension

- Church of the St Prodromos

Note the classification of minarets into three types: Mamluk, Ottoman, and Mamluk minarets that were probably renovated by the Ottomans (for further discussion see Alud and Hillenbrand 2000, 334).

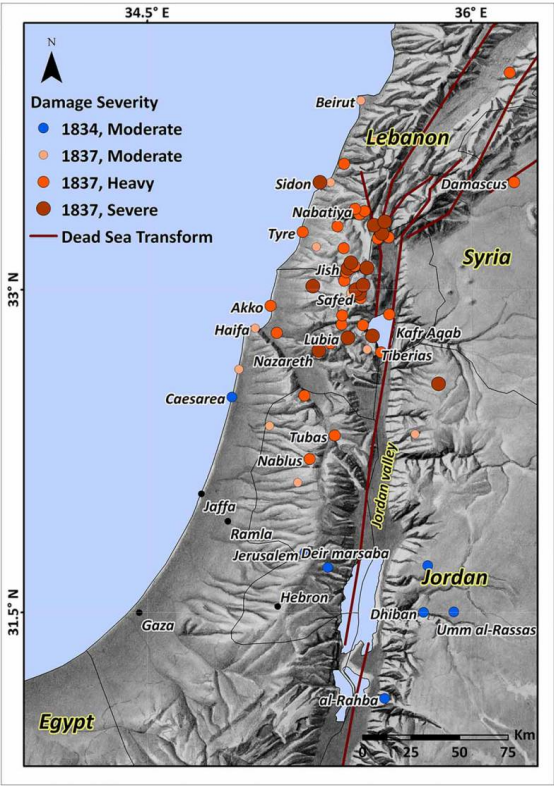

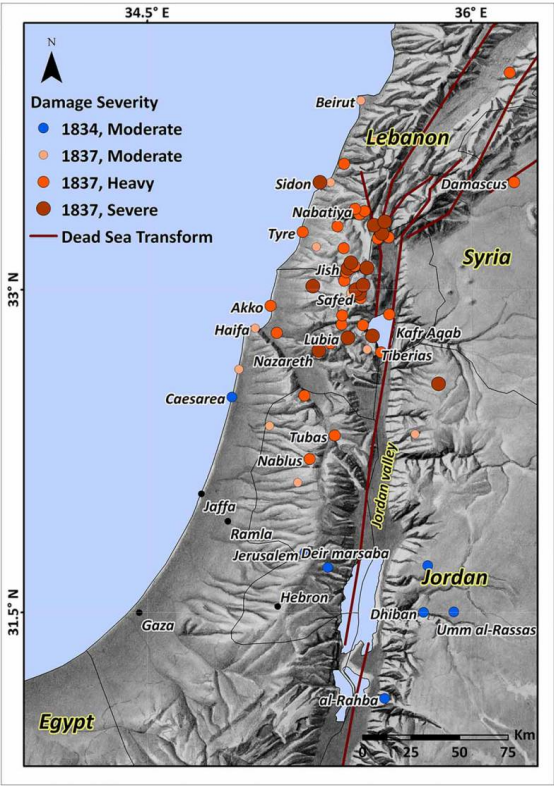

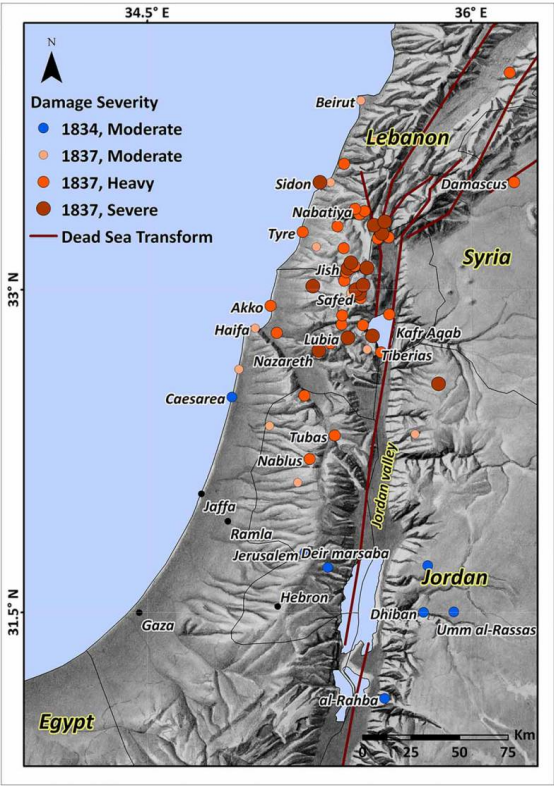

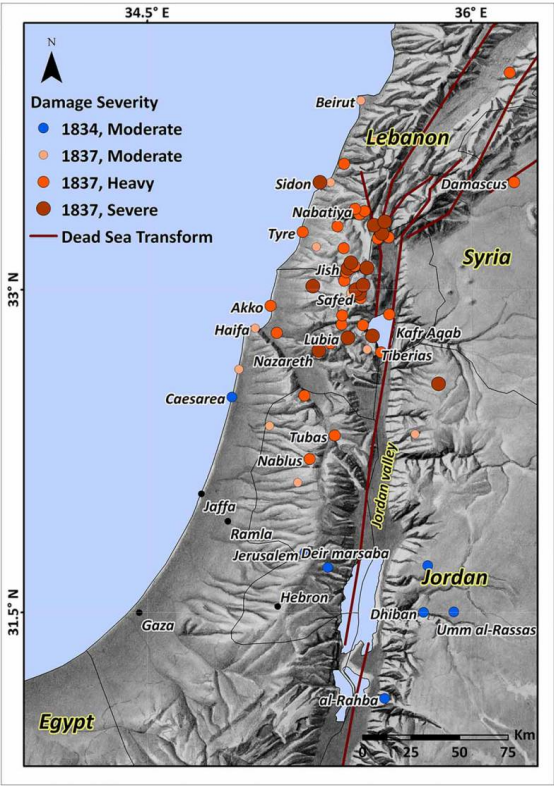

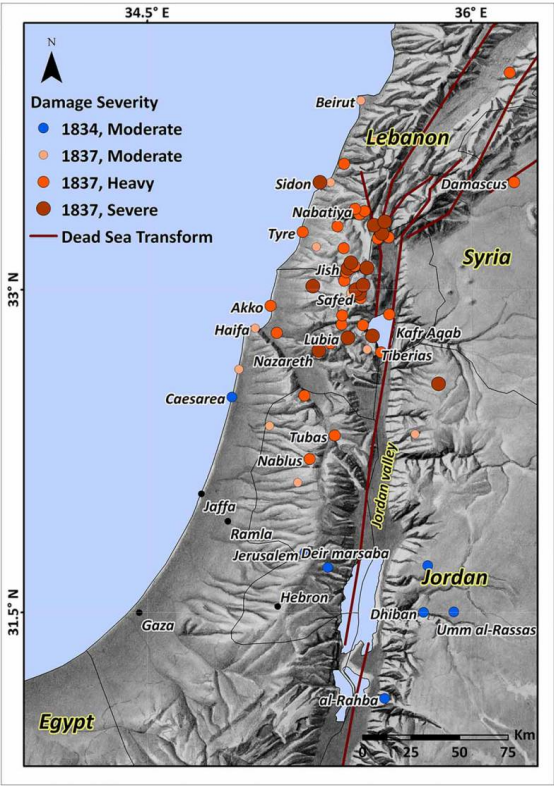

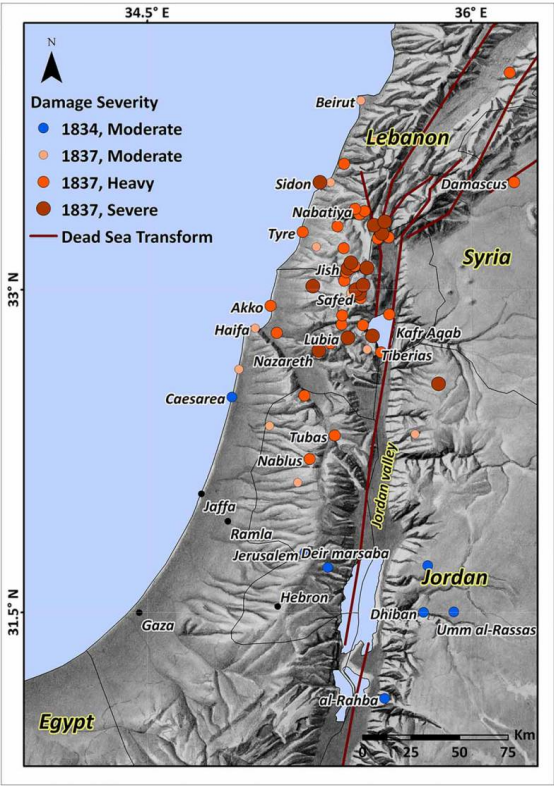

Zohar et al (2015) - Fig. 3 Damage Distributions

for 1834 and 1837 CE Earthquakes from Zohar et al (2015)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Damage distribution and its severity, ranging between ‘Moderate’ and ‘Severe’ (adapted from Zohar et al. 2013), of the May 1834 and January 1837 earthquakes, according to historical reports. Note that the damage that resulted from the 1837 event is more severe in northern than in central Palestine and did not spread south of the Nablus region.

Zohar et al (2015) - Fig. 10.1 Sites in Jerusalem

mentioned by Zimni-Gisler in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 1 The Old City of Jerusalem

and the King David Sepulchre complex from Zohar et al (2015)

Figure 1

The Old City of Jerusalem and the King David Sepulchre complex (outlined in orange and also in the inset). Major structures and minarets within the area include:

- Dormition Church

- the King David Sepulchre complex

- al-Nabi Da’ud minaret

- Greek-Orthodox cemetery

- Protestant cemetery

- Armenian church of the House of Caifas

- Zion Gate

- David Citadel with the al-Qal’a minaret

- Jaffa Gate

- ‘Hurva’ synagogue

- al-Omari minaret

- Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- al-Jami Omar mosque and minaret

- al-Hanaqah mosque and minaret

- al-Fakhriyya minaret

- Bab al-Silsila minaret

- al-Aqsa mosque

- al-Ghawanima minaret

- Bab al-Asbat minaret

- al-Hamra mosque and minaret

- al-Maulawiyya mosque and minaret

- Damascus Gate

- Church of the Ascension

- Church of the St Prodromos

Note the classification of minarets into three types: Mamluk, Ottoman, and Mamluk minarets that were probably renovated by the Ottomans (for further discussion see Alud and Hillenbrand 2000, 334).

Zohar et al (2015) - Fig. 3 Damage Distributions

for 1834 and 1837 CE Earthquakes from Zohar et al (2015)

Figure 3

Figure 3

Damage distribution and its severity, ranging between ‘Moderate’ and ‘Severe’ (adapted from Zohar et al. 2013), of the May 1834 and January 1837 earthquakes, according to historical reports. Note that the damage that resulted from the 1837 event is more severe in northern than in central Palestine and did not spread south of the Nablus region.

Zohar et al (2015) - Fig. 10.1 Sites in Jerusalem

mentioned by Zimni-Gisler in Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Mount Zion in Google Earth

- Mount Zion on govmap.gov.il

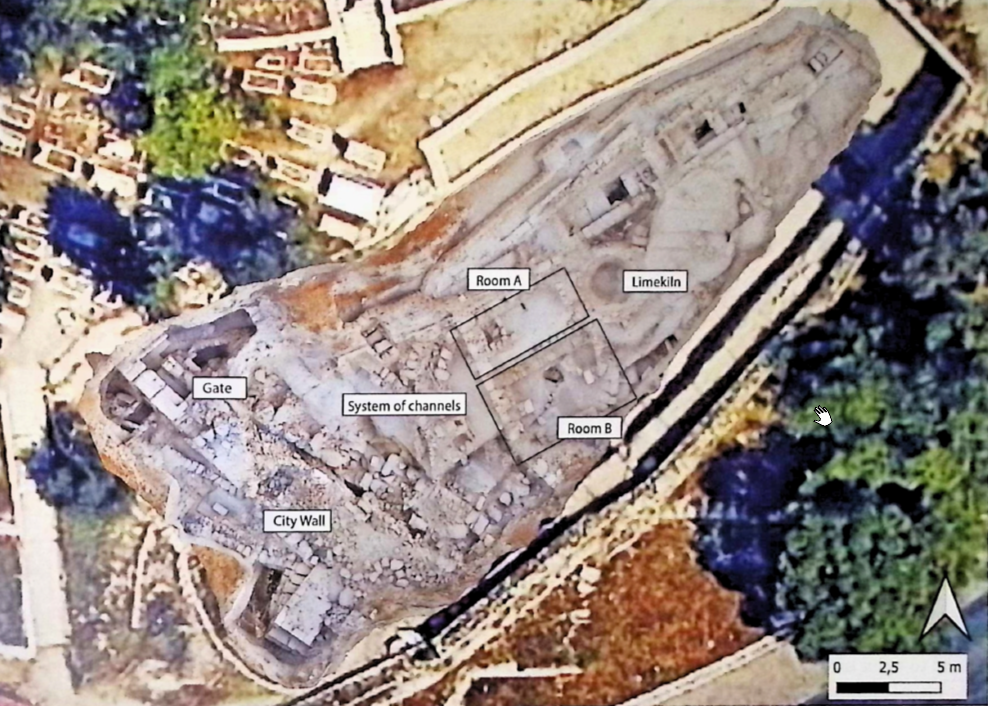

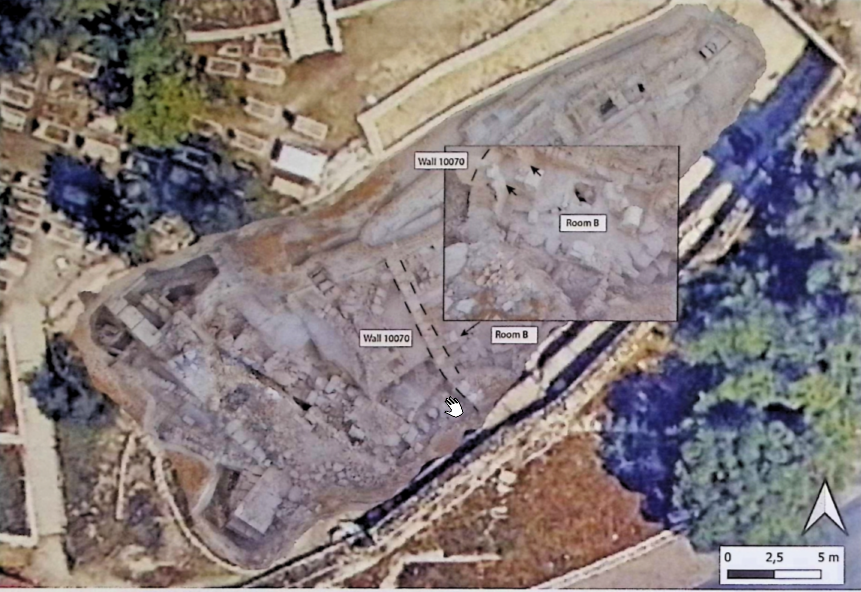

- Fig. 10.2 Aerial overview

of DEI area 1 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Mount Zion in Google Earth

- Mount Zion on govmap.gov.il

- Fig. 10.2 Aerial overview

of DEI area 1 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.4 Aerial view

of Mount Zion’s southern slope marking excavation sites from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 3.1 Aerial view

of Mount Zion’s southern slope marking excavation sites from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 1 Overview of

the GPIA excavation areas from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 3 Aerial view

of the excavation Area I from Vieweger et al. (2020)

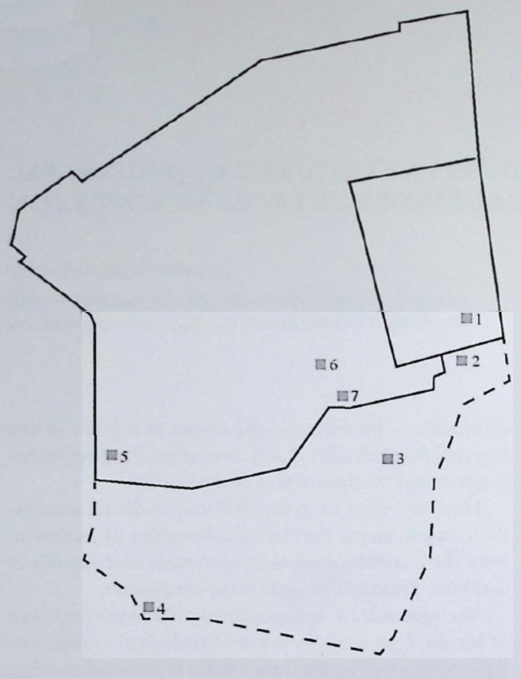

- Fig. 3.3 DEI areas

I-III orthophotographs from Vieweger et al. (2020)

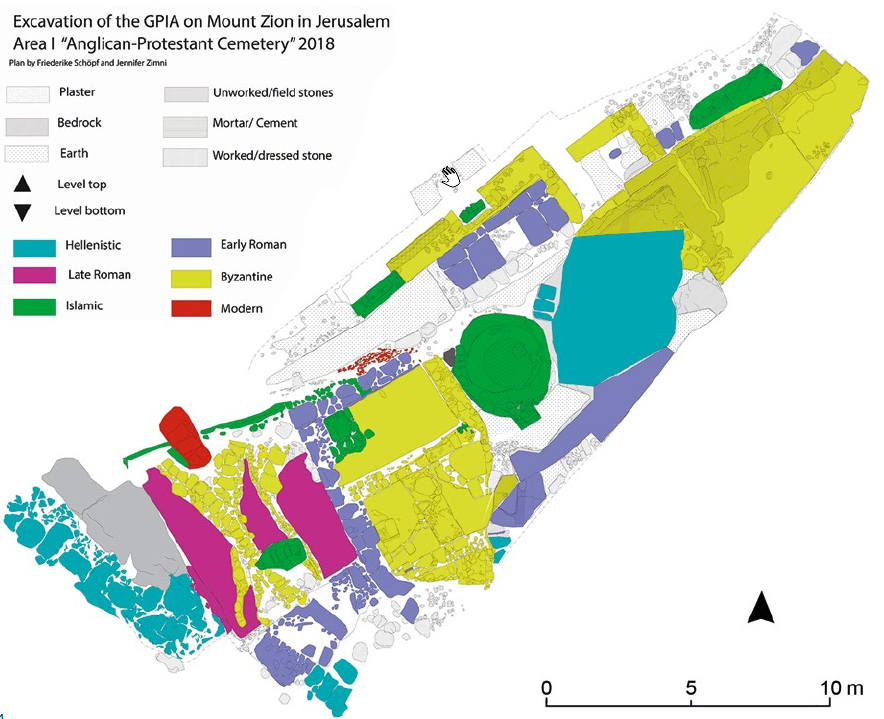

- Fig. 4 Plan of different

strata in Area I from Vieweger et al. (2020)

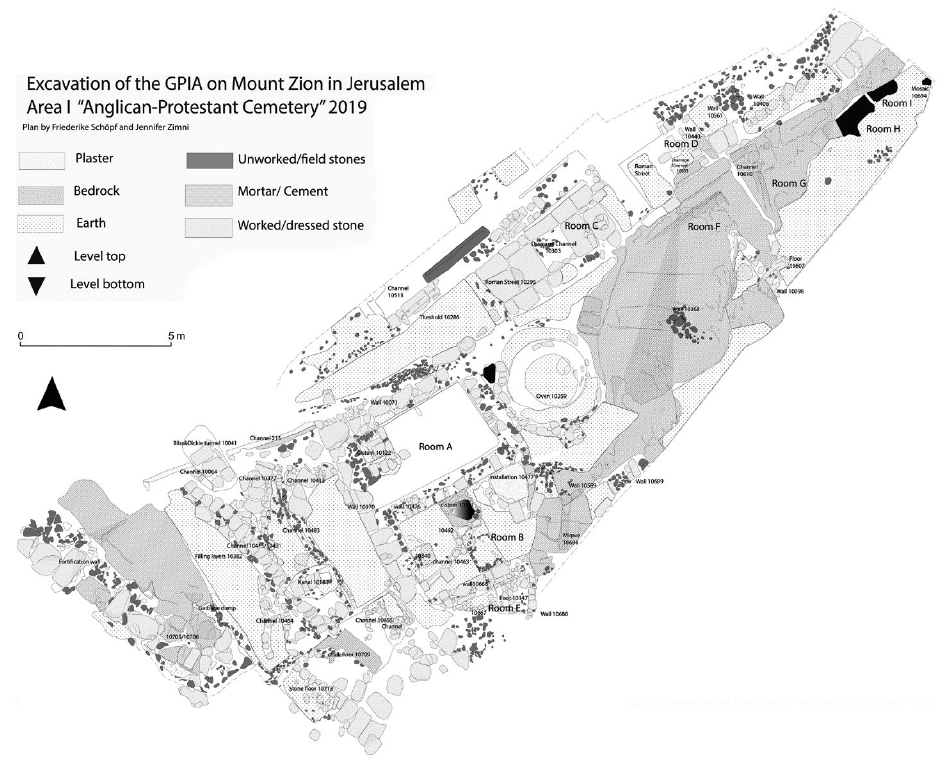

- Fig. 6 Plan of Area I

from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.2 Aerial overview

of DEI area 1 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 10.7 Warped wall

10070 within DEI area I from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 2.4 Aerial view

of Mount Zion’s southern slope marking excavation sites from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 3.1 Aerial view

of Mount Zion’s southern slope marking excavation sites from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 1 Overview of

the GPIA excavation areas from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 3 Aerial view

of the excavation Area I from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 3.3 DEI areas

I-III orthophotographs from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 4 Plan of different

strata in Area I from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 6 Plan of Area I

from Vieweger et al. (2020)

- Fig. 10.2 Aerial overview

of DEI area 1 from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 10.7 Warped wall

10070 within DEI area I from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

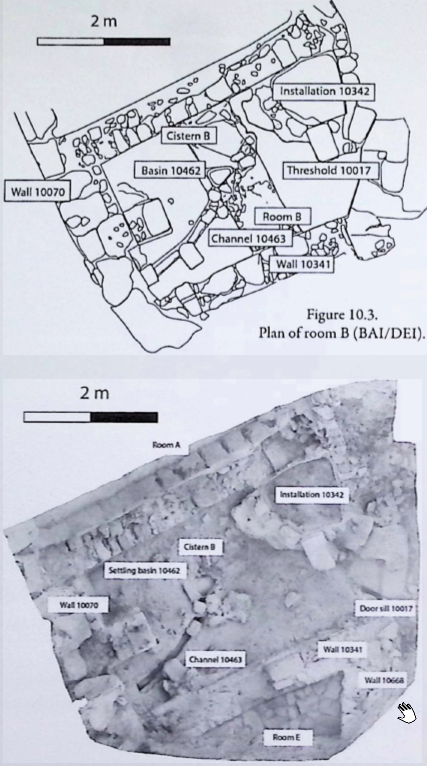

- Fig. 10.4 Orthophotograph

of room B from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

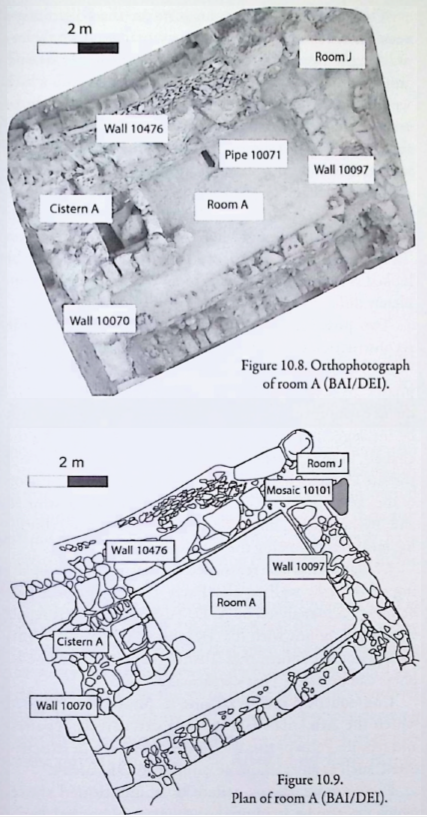

- Fig. 10.8 Orthophotograph

of room A from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 10.4 Orthophotograph

of room B from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 10.8 Orthophotograph

of room A from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 10.5 Destruction layer

of room B (BAI/DEI) from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 10.5 Destruction layer

of room B (BAI/DEI) from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

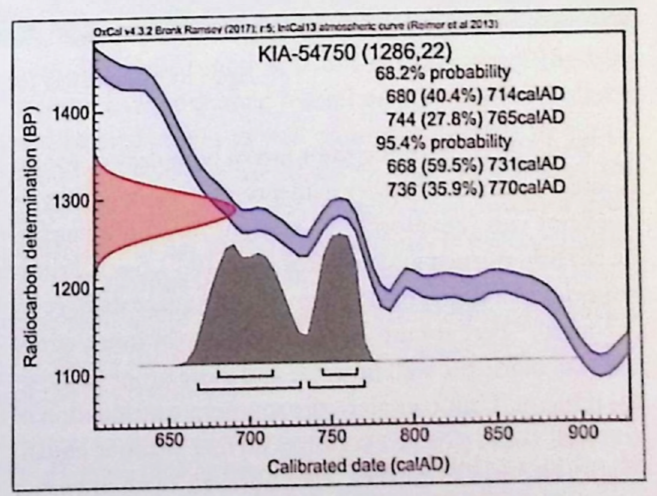

- Fig. 10.6 Radiocarbon

Results from Destruction Later in Room B from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

- Fig. 10.6 Radiocarbon

Results from Destruction Later in Room B from Lichtenberger and Raja (2025)

| Figure | Source | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 1 | Zohar et al (2015) |

The Old City of Jerusalem and the King David Sepulchre complex (outlined in orange and also in the inset). Major structures and minarets within the area include:

Note the classification of minarets into three types: Mamluk, Ottoman, and Mamluk minarets that were probably renovated by the Ottomans (for further discussion see Alud and Hillenbrand 2000, 334). Zohar et al (2015) |

The Old City of Jerusalem and the King David Sepulchre complex |

| Figure 2 | Zohar et al (2015) |

Photographs showing the height of the al-Nabi Da’ud minaret in various periods after mid-nineteenth century:

Zohar et al (2015) |

The Old City of Jerusalem and the King David Sepulchre complex |

| Figure 3 | Zohar et al (2015) |

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Damage distribution and its severity, ranging between ‘Moderate’ and ‘Severe’ (adapted from Zohar et al. 2013), of the May 1834 and January 1837 earthquakes, according to historical reports. Note that the damage that resulted from the 1837 event is more severe in northern than in central Palestine and did not spread south of the Nablus region. Zohar et al (2015) |

Damage Distributions for the 1834 and 1837 Quakes |

| Figure 4 | Zohar et al (2015) |

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Views of King David’s sepulchre and visible damage (noted by red arrows):

(photographs: M.Z.) Zohar et al (2015) |

King David’s sepulchre |

| Figure 5 | Zohar et al (2015) |

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Note the similarity between the two bases photographs B and C: M.Z. Zohar et al (2015) |

al-Nabi Da’ud and al-Qal’a minarets |

| Figure 6 | Zohar et al (2015) |

Fig. 6

Fig. 6Pre-1834 Drawings and maps of Jerusalem. Note the high shaft of al-Nabi Da’ud minaret (magnified and also marked in black arrows) in three of the drawings, and its similarity to the al-Qal’a minaret (red arrows):

Zohar et al (2015) |

Pre-1834 Drawings and maps of Jerusalem |

| Figure 7 | Zohar et al (2015) |

al-Nabi Da’ud minaret in drawings from 1833 and similar views for comparison from mid-nineteenth century and 2013:

Zohar et al (2015) |

al-Nabi Da’ud minaret in drawings from 1833 and similar views for comparison from mid-nineteenth century and 2013 |

| Figure 8 | Zohar et al (2015) |

Fig. 8

Fig. 8The complex in drawings painted in and after 1838:

In the drawings of Roberts and Bartlett (images A and B), black and red arrows denote the al-Nabi Da’ud and al-Qal’a minarets, respectively. Zohar et al (2015) |

The complex in drawings painted in and after 1838 |

| Table 1 | Zohar et al (2015) |

Table 1

Table 1The height (in metres) of the elements in the al-Nabi Da’ud and the al-Qal’a minarets. Parts taller than 2 m were estimated according to the width of a single cut-stone block times the number of the building rows Zohar et al (2015) |

Height of elements in al-Nabi Da’ud and al-Qal’a minarets |

| Table 2 | Zohar et al (2015) |

Table 2

Table 2Artists that have depicted the minaret of al-Nabi Da’ud Zohar et al (2015) |

Artists that have depicted the minaret of al-Nabi Da’ud |

The AD 749 earthquake that shook the entire southern Levant region also struck Jerusalem, as various historical sources describe.1 The seismological data suggests the damage suffered in Jerusalem was disastrous and resulted in grave architectural damage.2 The written, mainly Muslim,3 accounts however focus their description regarding the earthquake and its impact on the area around the al-Haram al-Sharif, mentioning mostly architectural damage to the religious buildings.4 Several narratives developed around the effects of the earthquake in Jerusalem, which were then carried over into later chronicles—for instance, the report of injuries to the descendants of Shadad al Aws, one of the Prophet's companions, and the destruction of their house.5

However, apart from the al-Haram al-Sharif area, little is known about the fate of other parts of Jerusalem since the historical sources seem to omit descriptions of domestic quarters damaged by the earthquake.

The recent DEI6 excavations on the southern slope of Mount Zion brought new archaeological evidence to light, which will be presented here. It shows that other parts of Jerusalem, especially the south-western hill, were also strongly affected by the earthquake. There, it becomes evident that urban life in this part of the city after the so-called "Muslim conquest" in AD 638 continued without any archaeologically noticeable changes for the following century7—until a catastrophic event hit the quarter. This destruction can be connected to the earthquake in AD 749. Following that, the urban character on the south-western hill changed drastically8.

Moreover, in light of this new archaeological evidence of the DEI excavations, this study aims to investigate and reassess further sites regarding potential impacts that the disastrous seismic tremor has left in Jerusalem. Several examples are assessed in the following: the area around the al-Haram al-Sharif, the new excavations of the DEI, the Armenian Garden, as well as the excavations in the modern-day Jewish Quarter and the case of the city walls (Fig. 10.1).

1. Theophanes (AD 758–817), as the main source on the earthquake, does

not report any damages specifically in Jerusalem in either of the

earthquakes he mentioned. However, he described that some cities were

completely or partially destroyed (Theophanes, Chronicle 423, p. 112;

426, p. 115). A similar report was written by Severus Ibn al-Muqaffa

(died in AD 987), who stated that between the years 744–768 a great

earthquake shook the entire East “from the city of Gaza to the furthest

extremity of Persia,” destroying many cities (Ibn al-Muqaffa, pp.

139–40). Further, Ibn Taghribirdi (c. AD 1409/1410–1470) and

al-Dhahabi (1274–1348) also reported heavy damage in Jerusalem as a

result of that earthquake (Ibn Taghribirdi, an-Nujūm az-zāhira fī

mulūk Miṣr wa-l-Qāhira, p. 311; al-Dhahabi, Tārīkh al-Islām

wa-ṭabaqāt al-mashāhīr, 121–40, pp. 29–30).

2. Marco et al. 2003, 667; table 2.

3. No damage is mentioned in Jerusalem by Samaritan sources (Karcz 2004,

784). The Cairo Geniza text, as a Jewish source, mentions a

commemoration list thought to commemorate the earthquake that struck

Jerusalem (Karcz 2004, 785). For a more detailed discussion of the

historical sources regarding the earthquake see Karcz 2004, 78–87;

Tsafrir and Foerster 1992.

4. See below. It has to be considered that these sources are based on

compilations from the eleventh century CE and therefore should not be

regarded as contemporary reports (Karcz 2004, 783).

5. Al-Dhahabi 121–40, pp. 29–30; Ibn Taghribirdi repeats the narrative

about the death of the descendants of Shadad al-Aws (an-Nujūm

az-zāhira, p. 311).

6. German: Deutsches Evangelisches Institut für Altertumswissenschaft des

Heiligen Landes (English: German Protestant Institute of Archaeology

of the Holy Land).

7. See Namdar et al. 2024.

8. Zimni 2023, 388–90.

The earthquake damage in and around the area of the al-Haram al-Sharif is well documented by historical sources and by archaeological evidence. The area (Fig. 10.1 no. 1) experienced massive remodelling at the beginning of the Umayyad period, when the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock, as well as Umayyad buildings (Fig. 10.1 no. 2) located south of the religious edifices were built.9

Unfortunately, the archaeological evidence that can be gathered from the Holy Sanctuaries — the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock — is limited.9 Therefore, the study of the written accounts is an essential source for investigating the extent of the architectural damage in this area. For instance, it is described by al-Wasiti that the al-Aqsa Mosque suffered severe damage from an earthquake in the middle of the eighth century AD.10 He tells that in the days of the reign of Caliph al-Mansur (AD 754–775), the eastern and western portions of the mosque fell due to an earthquake in the year AH 130.11 As a consequence, Caliph al-Mansur ordered the mosque’s restoration. Since no money was available for this, it is also known from the description of al-Wasiti, that the gold and silver plates decorating the mosque’s gates were to be stripped off, and dinars and dirham were to be coined from them.12 Moreover, he also stated that shortly afterwards another earthquake hit the mosque, which was then restored by the caliph’s successor, Caliph al-Mahdi.13

Furthermore, in the tenth century AD the writer al-Muqadassi wrote about the earthquake damage in the mosque: he described that the earthquake destroyed most of the building, except for the corner around the mihrab.14

South of the Mosque complex, several buildings were constructed during the Umayyad period. Those are interpreted as administrative centres,15 whereas one of these buildings (‘Building ii’) stands out as a possible ‘Umayyad palace’.16 According to the excavators, this complex shows clear archaeological evidence of damage by the 749 earthquake. The damage is described as “cracked walls and warped foundations, fallen columns and sunken floors.”17 The archaeological material also provides evidence for the dating of this destruction: a sewage channel within one of the buildings was blocked shortly before the building went out of use. The material found there was interpreted as Khirbet Mafjar Ware, dating to the first half of the eighth century AD.18

9. Only reports of earlier investigations are available

(Hamilton 1949; Grafman and Rosen-Ayalon 1999).

10. It needs to be kept in mind that the dating of the

described earthquake damage cannot be clarified with

certainty.

11. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 137, p. 92;

referring to AD 747/748 according to Karcz 2004, 780.

12. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 137, p. 92.

Here, it is debatable whether al-Wasiti refers only to the

Mosque itself or the entire Haram al-Sharif area (Elad

1995, n. 77).

13. al-Wasiti, Fada'il al-Bayt al-Muqaddas, no. 256, p. 92.

For a suggestion of the archaeological layout of these

rebuilding measures see Küchler 2007, 226–34. G. Le

Strange assumes the year AD 770–771 for the visit of

Caliph al-Mansur, whereas others suggest that this visit

already took place in AD 758 (Elad 1995, 40; Küchler

2007, 228).

14. al-Muqadassi, The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the

Regions, trans. by B. Collins, p. 276.

15. Rosen-Ayalon 1989, 8.

16. Ben-Dov 1985; Rosen-Ayalon 1989, 8–11.

17. Ben-Dov 1985, 321.

18. Ben-Dov 1985, 2–20; however, this chronology by the

early excavators was doubted by J. Magness who

redates the construction date of these buildings as well

as doubting their damage from the 749 earthquake due

to ceramic evidence supporting the buildings’ existence

throughout the Abbasid period (Magness 2010, 153).

However, in the author’s opinion, the damage described

by the excavators does suggest that a destructive event,

such as an earthquake, occurred in these buildings,

resulting in the described architectural remains.

The ‘Givʿati parking lot’ excavation site is located further south of the previously discussed Umayyad administrative buildings in the Ophel area (Fig. 10.1 no. 3). This is, except for the Haram al-Sharif area, the only place in Jerusalem which was drastically reconstructed at the beginning of the Umayyad period.19 This area was turned from what had been a prosperous Byzantine domestic quarter into an industrial quarter — mainly through the construction of a lime-kiln.20 This layout changed again “at some time during the eighth century CE” when, with the beginning of the Abbasid period, the lime-kiln was partly dismantled and covered, but only a few installations, wall stubs as well as pits were scattered throughout the area.21

In conclusion, one can say that at the site of the ‘Givʿati parking lot’ excavations noticeable changes occurred during the eighth century AD, but the causes cannot be determined with certainty. However, no archaeological traces of earthquake damage were observed at the site.22

19 Tchekhanovets 2018.

20 Ben-Ami 2020, 2–4.

21 Ben-Ami 2020, 283, 287 – pers. comm. Tchekhanovets.

22 Ben-Ami 2020, 283 – pers. comm. Tchekhanovets.

The excavation areas of the DEI project23 (Fig. 10.1 no. 4) are located on the southern slope of Mount Zion. The site to be discussed in the following — area 1 (Fig. 10.2) — is located within the boundaries of the Anglican-Prussian cemetery. There, parts of the fortification walls as well as inner-city buildings from the Late Hellenistic period until the Middle Ages were uncovered.24 The original urban layout of the domestic quarter can be dated back to the Early Roman period, but underwent significant remodelling and reuse during the Byzantine and Umayyad periods. These include the Byzantine city wall with an inserted city gate and eleven rooms. Two of these — rooms A and B — are crucial for the investigation of the damage done by the AD 749 earthquake and will be discussed in more detail in the following. The other rooms were partly destroyed by later building activities, such as the construction of medieval terracing walls, extending across the entire site.

The Byzantine domestic quarter was built around the fifth/sixth century AD and was inhabited throughout the Umayyad period. The site's proximity to the large Hagia Sion church on the plateau of Mount Zion — which continued to be in use until the Crusader period — the discovery of a mould for a cross-shaped pendant, as well as the archaeozoological evidence, suggest Christian inhabitation even throughout the Umayyad period.25 Its occupation continued until a destructive event caused the end of the quarter's inhabitation, evidenced primarily by a destruction layer mainly recorded archaeologically in room B.

Following the violent end of the domestic quarter, a lime-kiln was built in the midst of the former rooms, even destroying a few of them. Thus ending the previous period of a prosperous domestic quarter and turning it into an industrial one. Since the lime-kiln was built in the middle of the former living rooms, it provides a terminus post quem for the inhabited rooms.

23 Directed by D. Vieweger, K. Soennecken and the author. The project

started in 2015 and is still being continued.

24 Zimni 2023; Vieweger and others 2020.

25 Namdar and others 2024; Zimni 2023, 388–93.

The earthquake's impact was mainly recorded in room B (Figs 10.3, 10.4). The rectangular room measures 5 × 6 m. A cistern below supplied its inhabitants with fresh water. It was likely fed by water collected from the roof, which was led by a pipe on the room's western side into a settling basin — from there into the cistern.

A destruction layer was found which filled the entire room (Fig. 10.5). It contained many larger stones which were previously used as building material. Remains of the former vaulting arch can be observed as well. Other building material, such as numerous roof tiles, remnants of wall plaster, a large number of tesserae, and several pieces of ceramic pipes, was also found in this destruction layer. Most of the archaeological material was found burnt — in addition, large chunks of charcoal were also excavated.

This destruction was found in situ and was not removed for later building activity as is the case in all the other rooms, but overbuilt by an early Islamic channel. It provided a unique opportunity to investigate the transitional period from a domestic quarter to an industrial one in the eighth century AD.

Various events may be considered to be responsible for this destruction: the Persian conquest in AD 614, the “Muslim conquest” in AD 638, and the AD 749 earthquake. A closer analysis of the finds from the destruction layer allows us to state that this destruction of the room had occurred not earlier than the Umayyad period. The pottery material, mainly fine ware, found within the contexts in question dates into the Umayyad period, but not later than that, indicating that the room was in use during that time.

Moreover, a C14 sample collected at the entrance to the cistern situated below the room also suggests continuous habitation during the early eighth century AD (Fig. 10.6).

Consequently, one can conclude that the destruction layer was caused by the AD 749 earthquake since the other possible options such as the Persian as well as the “Muslim conquest” for this destruction are dated in the seventh century AD only and therefore can be excluded. After that, the room's destruction layer was sealed by the building of a water channel on top of it. This might be connected to the lime-kiln mentioned above, which was built after the rooms were no longer inhabited.

Wall 10070, forming the western boundary of rooms A and B, provides further evidence of seismic activity. It does not run (anymore) in a straight line, but seems to be slightly warped and crooked (Fig. 10.7). Such a tilt is considered a characteristic sign of earthquake damage by S. Marco.26 Perhaps the vault attached to the inner side of the wall made the wall unstable and more prone to possible damage. Unfortunately, the southern continuation of the wall could not be excavated further without endangering the wall's stability. Therefore, an earthen corner was left in the south-west (Fig. 10.7). Consequently, one cannot see if the stone blocks of the warped part of wall 10070 are perhaps shifted somehow.

26 Marco 2008, 151, fig. 2L.

Room A (Figs 10.2, 10.8, 10.9) also underwent remodelling during the same period. The room, similar to room B, was built on top of a cistern whose entrance is situated within the room's north-western corner A (Fig. 10.7). The cistern probably belonged to the room's original Early Roman layout but was used throughout the Byzantine period. During the Early Islamic period, the cistern's entrance was raised approximately 0.50 m higher than its original floor level. A stone slab integrated into the room's outer wall suggests that the early Islamic floor level was also raised to the same height. Finds taken from the contexts to which the cistern's entrance was raised can be dated at the latest to the Umayyad period.

It can be concluded that the damage caused by the earthquake of AD 749 initiated architectural changes in the domestic neighbourhood on the southern slope of Mount Zion, marking the end of its residential use. After this severe destruction, which can be traced archaeologically in room B, the inhabitants decided not to rebuild the former domestic quarter but rather to build a lime-kiln in the same place. Thus, turning the previous residential quarter into an industrial quarter, partially built on top of the remains of the destroyed rooms, partially destroying the former rooms.

It can be assumed that already earlier, during the seventh century AD, archaeologically not tangible structural changes must have taken place within the society, resulting in the final decision not to rebuild that quarter. The destruction caused by the earthquake only seems to have been the final triggering factor for those urban changes on Mount Zion.

With its detailed publication, the excavations in the Armenian Garden under the direction of A. D. Tushingham27 from 1961 to 1967 provide lots of material for studying the Byzantine–Early Islamic period. This site might also show archaeological evidence for the AD 749 earthquake which was not interpreted as such by the excavator.

Three phases of buildings of the Byzantine–Early Islamic period were distinguished: the phase entitled ‘Byzantine I’, which clearly served a religious (Christian) purpose, likely a chapel or even a small church.28 Attributed to this phase are an apse, the ‘Hare Mosaic’, an additional mosaic, some cisterns, and a few walls.29 The excavators attribute this phase to the end of the reign of Justinian. A. D. Tushingham assumes this phase was short,30 suggesting an “abrupt end by a washout.”31

After that, a completely different constructed building sounded the bell for a new architectural phase in this area. The so-called ‘Byzantine II’ phase consists of a building erected with a completely different orientation. It had a central courtyard and three adjoining smaller rooms. A. D. Tushingham describes this building as a possible khan or a caravanserai.32

Additionally, an area enclosed with walls containing structures which are called ‘bins’, is attributed to this period.33 Their function is not entirely clear. The bins seem to have contained several pieces of burned plaster and burned stones as well as a large number of tiles.34 However, possible use as a kiln was excluded by the excavator.35 This phase was brought to an end by a ‘great washout’, similar to the previous one. It is described by A. D. Tushingham as follows: “It is difficult to believe that rains alone could have been responsible for such a flood, but there is no doubt that the water was the agent of the destruction.”36

The last phase, ‘Byzantine III’, was a reconstruction of the previous one but with a reduction of the large central courtyard, which was cut in half by an inserted wall.38 The excavator interpreted both of the latter buildings as a possible caravanserai or a pension for pilgrims.39

In the light of the interpretation of the DEI area I results, the transition between the different phases should be reassessed. A. D. Tushingham claims that the last of the phases, ‘Byzantine III’, was destroyed during the seventh century AD, either by the Persian conquest in AD 614 or by the ‘Muslim conquest’ in AD 638 and only resettled in the medieval period.40 Such an occupation gap does not seem very likely, considering that during the Umayyad period, the south-western hill was still a flourishing place, especially for Christian pilgrims, as is known from various sources.

However, A. D. Tushingham still reports excavated material, such as pottery and coins, from the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, mainly in various fillings.41 This does indicate that the area was occupied during this period, but no architectural features were attributed to this period.

J. Magness reassessed the pottery assemblages found in the excavations of the Armenian Garden. She discovered that the pottery of the Byzantine levels includes a mixture of types that can be dated from the sixth to the eighth centuries AD. Therefore, she concludes that it might be possible that the settlement phase in the Armenian Garden cannot be dated exclusively to the Byzantine period but can also have continued throughout the Umayyad period.42 Considering again the archaeological evidence of continuous occupation from DEI area I,43 a similar inhabitation pattern throughout the Umayyad period in the nearby Armenian Garden seems very likely.

Therefore, the author suggests in the following a reassessment of the Byzantine occupational phases — at least the later ones — into the Early Islamic period. Instead of ‘washouts’ (or the ‘Muslim conquest’) which were described by the excavator, these events might be connected to the earthquake. Following each ‘washout’ the area was rebuilt differently. Similarities can be drawn with the excavation results of the nearby DEI area I — after the destructive earthquake, the urban layout was altered drastically, thus changing the nature of the site.

The transition between the excavator’s phases ‘Byzantine I’ and ‘Byzantine II’ in particular may be looked at here: from a chapel to an architecturally completely different, possible caravanserai.

Two possible solutions can be considered for the reconstruction of the Armenian Garden’s history:

Either the earthquake occurred between Tushingham’s phases ‘Byzantine I’ and ‘Byzantine II’ and as a consequence, the former chapel with an apse was overbuilt by the suggested caravanserai (instead of rebuilding the chapel). In any case, these measures changed the nature of the site altogether. The other option is the modification of the caravanserai in Tushingham’s phases ‘Byzantine II’ and ‘Byzantine III’ might be a possible result of rebuilding measures following the earthquake.44

J. Magness has also reassessed the dating of the repairing of the city wall to the Early Islamic period (see below); as is analysed by A. D. Tushingham, this repair work corresponds with his ‘Byzantine II’ period.45 This dating would confirm that Tushingham’s ‘Byzantine II’ phase can be dated post-earthquake.

Consequently, the ‘Byzantine III’ phase was a time in which the Armenian Garden was extensively repaired and rebuilt. Perhaps this was necessary after a destructive event, such as an earthquake, similar to DEI area I.

Furthermore, the so-called ‘bins’ mentioned above, which can also be attributed to the possible early Islamic layers, contain a lot of burnt material and former building material, such as burnt plaster and tiles, as described by A. D. Tushingham.47 It can be suggested that this material could be the remains of the destroyed former buildings, the ‘Byzantine I’ structures. Those ‘bins’ were sealed, as described by A. D. Tushingham, by the latest ‘Byzantine III’ floor, which supports that argument.48 For this, a detailed find analysis of the content of these ‘bins’ would be necessary.

Certainly, this chapter cannot provide a complete detailed reassessment of all the stratigraphical contexts and corresponding finds of the excavation in the Armenian Garden; still, it can provide cause to reconsider the archaeological history of the site during the transitional period from the Byzantine to the Early Islamic period.

27 From 1962 onwards; the first year (1961) was under the

direction of R. de Vaux and J. A. Callaway (Tushingham 1985, 3).

28 Tushingham 1985, 101, pl. 6.

29 Tushingham 1985, 101, pl. 6.

30 Without providing a further time frame for “short.”

31 Tushingham 1985, 101. It remains uncertain what exactly

is meant by “washout.”

32 Tushingham 1985, 104.

33 Tushingham 1985, 101–02, pl. 6.

34 Tushingham 1985, 79.

35 Tushingham 1985, 79.

36 Tushingham 1985, 69.

37 Which is actually subdivided into IIIA

(redressing the damage caused by the previous 'washout') and IIIB

(actual rebuilding measures; Tushingham 1985, 103).

38 Tushingham 1985, 103–04.

38 Tushingham 1985. 103-04.

39 Tushingham 1985. 104.

40 Tushingham 1985, 104-05. Many earlier scholars,

especially from the 1960s and 1970s, attributed any

urban changes during this period to the `Muslim

conquest, neglecting the possibility of the AD 749

earthquake. But this view is no longer reflected in

modern research (Avni 2014, 14).

41 Tushingham 1985, 105-06. He wrote that the majority of

the Umayyad and Abbasid coins stems from 'deposits

that on stratigraphic grounds can be assigned to the

fills chat precede the first medieval, that is Ayyubid,

occupation of the site' (Tushingham 1985, 106).

42 Magness 1991, 212.

43 Zimni 2023; Namdar and others 2024.

44 We must also consider the possibility that several earthquakes

or aftershocks occurred in a short time, causing two different

“washouts” in the Armenian Garden.

45 Keeping in mind, that these repairs are either a result of the

earthquake or might also be the result of the reconstruction of the

city walls by Caliph Hisham.

46 Tushingham 1985, 65.

47 Tushingham 1985, 79.

48 Tushingham 1985, 79.

The excavations directed by N. Avigad from 1969 to 1982 in the modern-day Jewish Quarter within the Old City are usually a rich source for reconstructing Jerusalem's history and archaeology. However, no explicit hints suggest an impact of the AD 749 earthquake on the Jewish Quarter. In many areas, the remains from the eighth century AD onwards, even until the Ottoman period are combined into one stratum.49 This is likely the result of modern building activity there, which may have destroyed many of the remains that date later than the Byzantine period.50

Nevertheless, the modern Jewish Quarter excavations also revealed the Roman-Byzantine Cardo as the main thoroughfare during that time. The areas including the western Cardo (area X), do not seem to record any structures between the sixth to the thirteenth centuries AD.51 The same can be said about the pottery deriving from the fills above the Cardo — only a few examples of the pottery shards can be dated to the Early Islamic period, whereas most of the pottery can be dated to later periods.52 In contrast, a few coins from the Umayyad and Abbasid periods nevertheless suggest a use throughout these periods.53 Moreover, the excavations carried out in Jerusalem's eastern Cardo did not reveal any earthquake damage. It is described that the eastern Cardo was partially overbuilt by a new building which also dismantled parts of the Cardo.54

It can be assumed that any possible damage caused by the earthquake in those areas was simply rebuilt in the same way as before, and therefore no destroyed architecture was found. But according to the reports, no repair layers were observed in the architectural remains that could support such a rebuilding.

49 See for area A: Geva and Reich 2000, 43; area W: Geva and

Avigad 2000, 135; area E: no strata later than the Byzantine

period are recorded at all (Geva 2006, 11, 70); area B: the

last stratum combines remains from the Byzantine period

to the Mamluk period (Geva 2010, 10); area Q also does not

distinguish between any different strata during the Early

Islamic period — it ranges from the eighth to thirteenth

centuries AD (Geva 2017a, 8, 33); in area H the majority of

the archaeological remains later than the Early Roman period

were destroyed by building activity of the modern Jewish

Quarter buildings (Geva 2017b, 156). Severe damage from

the building activity seems to have occurred in areas F-2, P,

and P-2, since the last stratum covers all the remains from

the Late Roman until the Ottoman period (Geva 2021, 12).

50 See for instance Geva 2010, 10; 2017a, 8, 33.

51 Gutfeld 2012a, 27, 29, 41, 84.

52 Avissar 2012, 312.

53 Bijovsky and Berman 2012, 346–49.

54 Weksler-Bdolah and Onn 2019, 55. It seems very likely that

this phenomenon can be seen in the light of the “usual”

urban change in that period which includes encroachment

of colonnaded streets.

The excavations in the Jewish Quarter also revealed remains of the 'New Church of the Holy Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary,' commonly known as the 'Nea Church.55 The church, depicted on the Madaba Map, was one of the most significant building ventures undertaken by Emperor Justinian I and therefore played a central role in Christian Jerusalem.56 The final days of the Nea Church have not yet been fully studied. The pottery from the areas within the church clearly shows continuation of the church throughout the Umayyad period,57 but found its end sometime during the Abbasid period.58 Different dates are suggested for the church's discontinuation: N. Avigad indicated that it was destroyed by an earthquake in the eighth century AD.59 D. Bahat, on the other hand, suggested an earthquake in AD 846, although he also suggested the possibility that the church was destroyed during the earthquake of AD 749.60 These assumptions about the church being damaged in the earthquake are based on account of the Commemoratorium de casis Dei — written in the ninth century: “The Church of St Mary which was thrown down by the earthquake and engulfed by the earth has side walls 39 dexteri long.”61 The Nea Church is the only church mentioned in this source as having suffered damage from the earthquake — no other churches were mentioned.

But in contrast to the textual evidence, no actual archaeological evidence was recorded indicating any impact of the earthquake. Following the types of possible seismic damage by S. Marco,62 it can be assumed that there is archaeological evidence for the earthquake in the Nea Church: a published photograph of the site63 shows the height difference which can be seen in different parts of the church's marble pavement — some parts that were not supported by a wall running below it are located 0.10 m lower than other parts.64 Additionally, it must be noted that most of the marble slabs were broken, which may perhaps hint at seismic damage.65 But the suggestions remain merely assumptions, as no other evidence for this can be retrieved.

55 Gutfeld 2012b, 141.

56 Gutfeld 2012b, 141.

57 Areas D and D-1; Avissar 2012, 311-12; Although the

stratigraphy published in the excavation report does not

subdivide the Early Islamic phases further (Gutfeld 2012b,

149, 215).

58 Gutfeld 2012a, 10.

59 Avigad 1977, 145.

60 Bahat 1996, 59.

61 Commemoratorium de casis Dei, p.138.

62 Marco 2008.

63 Gutfeld 2012b, 174, ph. 5.26 (L.2191 is located higher than

L.2199; Gutfeld 2012b, 176).

64 Gutfeld 2012b, 174.

65 Gutfeld 2012b, 224; Marco 2008, 151–52.

It seems likely that when Jerusalem's buildings suffered several destructions during the earthquake, that its city wall was also damaged.66 Indeed, several excavations around the city walls show signs of repair works during the period in question.

Precisely when the wall circuit used during the Byzantine period — the so-called 'Eudocia Wall' — was built and how long it remained functional is debated amongst scholars.67 However, one can be quite certain that during the eighth century AD, under discussion here, the same city wall was still in use.

J. Magness reassessed some of these repair phases in the Byzantine–Early Islamic city wall circuit based on a re-evaluation of the pottery — especially the precise distinction of Byzantine and Umayyad ceramic material — to clarify the chronology of the wall repairs. She concluded that, for instance, excavations by R. Hamilton along the northern part of the city wall during the 1930s revealed “clear evidence for a reconstruction of the city wall in the vicinity of the Damascus Gate no earlier than the first half of the eighth century C.E.”68

In the city's south-west, an additional stretch of the city wall with “clear evidence for a major rebuild” from the same time period was found in the Armenian Garden by A. D. Tushingham.69 This part of the wall was also reassessed based on the pottery evidence by J. Magness. She re-attributes some of the excavated pottery forms found in the city wall’s foundation trenches to the (Late) Umayyad period70. Consequently, J. Magness suggests an Early Islamic, Umayyad date for the repair of the city wall rather than the sixth century, as stated by A. D. Tushingham.71

Therefore, it can be said that Jerusalem’s city walls were reconstructed or renovated in the middle of the eighth century AD based on the two re-evaluated archaeological examples, which show that renovation works were carried out in this time period.72 However, it cannot be stated with certainty that these repair phases of the city wall are a result of the AD 749 earthquake rather than later measures to reconstruct buildings. It is also possible that these rebuilding measures were part of other construction projects in the eighth century AD — for instance, the reconstruction of Jerusalem’s city walls ordered by Caliph Hisham between AD 728 and 744 — because the walls were previously torn down by his predecessor Caliph Marwan II, as described by Theophanes.73

The archaeological material does provide a terminus post quem —the first half of the eighth century AD—for the partial reconstruction of the city walls, but due to the proximity of both events in question, an exact attribution to one of them, at least in the case of the city walls, cannot be given.

66 Weksler-Bdolah 2011, 421.

67 Weksler-Bdolah 2011, 421-24; Zimni 2023, 286-90.

68 Magness 1991, 212.

69 Tushingham 1985, 65, 68.

70 Magness 1991, 212-13.

71 Magness 1991, 215; Tushingham 1985, 65, 68.

72 Excavations in the area of the citadel suggest further

alterations of the early Islamic city wall (Magness 1991,

214; Wightmann 1993, 233).

73 Theophanes, Chronicle 422, p.114; Wightmann 1993, 235;

Magness 1991, 215.

It has become evident — both from historical records as well as from archaeological evidence — that Jerusalem's buildings suffered severe damage from the AD 749 earthquake. The al-Aqsa Mosque in particular faced partial destruction as described in various historical sources. Additionally, the area located south of it — the “Umayyad palaces” — also shows archaeological evidence of similar architectural damage.

While the primary written Muslim sources for that time only describe the damage that occurred in the al-Aqsa Mosque in more detail, other religious edifices were also affected by that earthquake damage — such as the Nea Church, for instance, as can also be learned from historical sources. But with this being the only larger Christian building mentioned, it certainly raises the question of the fate of other significant churches, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or the Hagia Sion.74 Not much is known about any earthquake damage to the latter buildings during the eighth century AD. Pilgrim itineraries do not mention the remains of any destruction during that time75.

New archaeological research from the south-western hill in DEI area I provides compelling evidence that Jerusalem's domestic quarters also suffered damage from the earthquake. A clear destruction layer in room B suggests that these buildings were severely destroyed, leading to extensive remodelling that altered the character of the area.

Reassessment of the archaeological data from the Armenian Garden indicates similar transformations.

It can be said that the devastating seismic catastrophe functioned — certainly at least on Jerusalem’s south-western hill — as an agent of change for the cityscape, triggering drastic urban alterations, thus changing the nature of the respective quarters.

These alterations were very likely the result of structural changes within society that preceded the earthquake and created the need to change the nature of a few parts of the city.

Unfortunately, not as much is known about other parts of the city, since the Jewish Quarter excavations, for instance, cannot contribute as much to that question as most of the archaeological remains from the period in question have fallen victim to modern construction works.

However, the study also shows that the transitional period from the Byzantine to the Early Islamic period cannot be looked at in the city as a whole. Instead, it needs to be looked at independently in different parts of Jerusalem on a smaller scale to understand the larger-scale image of the city.76

This contribution shows the importance of the earthquake of AD 749 (and its impacts) for investigating the development of Jerusalem during the transitional period, especially from the Umayyad to the Abbasid period. In many cases, the archaeological contexts do not show evident damage which can be connected to the earthquake or are not interpreted as such.

In general, the lack of archaeological material, such as apparent destruction layers, cannot be taken as evidence that Jerusalem was not affected by the earthquake, since, as shown in this study, extensive remodelling and reuse would not leave many destruction layers visible in situ in the archaeological record.

Therefore, future excavations in Jerusalem might shed more light on the transitional phases as well as on the impact of the earthquake in AD 749 and its consequences for Jerusalem's urban layout.

74 The sparsity of the archaeological remains of this

church might also affect that state of knowledge.

75 The only known destruction of the Hagia Sion is during

the Persian Conquest in AD 614.

76 This is already obvious in previous transitional periods,

such as the beginning of the Umayyad period. Whereas the south-eastern part

of the city is massively reconstructed (see also Whitcomb 2011) the

south-western hill shows urban continuity until the middle of the

eighth century AD - which likely only ended with the earthquake

(see Zimni 2023; Namdar and others 2024).

| Effect | Location | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Room B on Southern Slope of Mount Zion |

Fig. 10.5 |

|

|

Room B on Southern Slope of Mount Zion |

Fig. 10.7 |

|

| Effect | Location | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

al-Nabi Da'ud Minaret

The Old City of Jerusalem and the King David Sepulchre complex (outlined in orange and also in the inset). Major structures and minarets within the area include:

Note the classification of minarets into three types: Mamluk, Ottoman, and Mamluk minarets that were probably renovated by the Ottomans (for further discussion see Alud and Hillenbrand 2000, 334). Zohar et al (2015) |

Fig. 8a

Fig. 8a

Fig. 8aPainting by David Roberts in 1838 CE (Roberts (1842-49) that shows an apparently ruined al-Nabi Da’ud minaret (pointed to by black arrow) extracted from Zohar et al (2015) Fig. 4C

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Views of King David’s sepulchre and visible damage (noted by red arrows):

(photographs: M.Z.) Zohar et al (2015) |

|

|

wall beside the eastern entrance facing the Muslim cemetery | Fig. 4B

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Views of King David’s sepulchre and visible damage (noted by red arrows):

(photographs: M.Z.) Zohar et al (2015) |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Room B on Southern Slope of Mount Zion |

Fig. 10.5 |

|

|

|

Room B on Southern Slope of Mount Zion |

Fig. 10.7 |

|

|

-

Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

al-Nabi Da'ud Minaret

The Old City of Jerusalem and the King David Sepulchre complex (outlined in orange and also in the inset). Major structures and minarets within the area include:

Note the classification of minarets into three types: Mamluk, Ottoman, and Mamluk minarets that were probably renovated by the Ottomans (for further discussion see Alud and Hillenbrand 2000, 334). Zohar et al (2015) |

Fig. 8a

Fig. 8a

Fig. 8aPainting by David Roberts in 1838 CE (Roberts (1842-49) that shows an apparently ruined al-Nabi Da’ud minaret (pointed to by black arrow) extracted from Zohar et al (2015) Fig. 4C

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Views of King David’s sepulchre and visible damage (noted by red arrows):

(photographs: M.Z.) Zohar et al (2015) |

|

|

Namdar, L., J. Zimni, O. Lcrnau, D. Vieweger, Y. Gadot, and L. Sapir-Hen (2024)

'Identifying Cultural Habits and Economical Preferences in Byzantine and Early Islamic, Mount Zion, jerusalem; Journal of lslamic Archaeology, 10.2: 175-94.

Vieweger, D., J. Zimni, F. Schopf, and M. Wiirz. (2020)

`DEI Excavations on the Southwestern Slope of Mount Zion (2015-2019)

; Archaologischer, Anzeiger, 2020.

Zimni, J. (2023) 'Urbanism in Jerusalem from the Iron Age to the Medieval Period at the Example of the DEI Excavations on Mount Zion'

(unpublished doctoral thesis, Bergische Universitic Wuppertal)

Zimni-Gitler, J. (2025) Chapter 10. Traces of the AD 749 Earthquake in Jerusalem: New Archaeological Evidence from Mount Zion

, in Lichtenberger, A. and Raja, R. (2025) Jerash, the Decapolis, and the Earthquake of AD 749,

Brepolis

Zohar, M., et al. (2015). "Why Is The Minaret So Short? Evidence For Earthquake Damage On Mt Zion." Palestine exploration quarterly 147(3): 230-246.

Alud, S. and R. Hillenbrand (2000). Ottoman Jerusalem: The Living City, 1517–1917.

Ambraseys, N. N. (1997). Annals of Geophysics 11(null): 923.

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: A Multidisciplinary Study of Seismicity up to 1900.

Ambraseys, N. N. and M. Barazangi (1989). Journal of Geophysical Research-Solid Earth and Planets 94(B4): 4007.

Ambraseys, N. N. and I. Karcz (1992). Terra Nova 4(null): 253.

Arundale, F. (1837). Illustrations of Jerusalem and Mount Sinai including the most interesting sites between Grand Cairo and Beirout.

Asher, A. (1927). The Itinerary of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela.

Balmar, J. and T. H. Horne (1835). The Biblical Keepsake, or, Landscape Illustrations of the Most Remarkable Places Mentioned in the Holy Scriptures.

Bartlett, W. H. (1838). Syria Illustrated with Description of the Plates by John Carne.

Bartlett, W. H. (1844). Walks about the City and Environs of Jerusalem.

Bartlett, W. H. (1855). Jerusalem Revisited.

Ben-Arieh, Y. (1970). The Discovery of the Holy Land in the Nineteenth Century.

Ben-Arieh, Y. (1973). Eretz Israel 1(null): 54.

Ben-Arieh, Y. (1974). The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 3(null): 150.

Ben-Arieh, Y. (1977). A City Reflected in Its Times - Jerusalem in the Nineteenth Century.

Ben-Arieh, Y. (1979). A City Reflected in Its Times. New Jerusalem - the Beginnings.

Ben-Arieh, Y. (1986). Cathedra 40(null): 159.

Ben-Arieh, Y. (1997). Painting the Holy Land in the Nineteenth Century.

Ben-Arieh, Y., et al. (2001). A Land Reflected in Its Past.

Bloom, J. M. (1989). The Minaret: Symbol of Islam.

Bonfils, F. (1877). Souvenirs d'Orient: Album pittoresque des sites, villes et ruins les plus remarquables de la Terra-Saints.

Burgoyne, M. H. (1990). Mamluk Jerusalem.

Calman, S. E. (1837). Description of Part of the Scene of the Late Earthquake in Syria.

Cohen, A. (1982). Cathedra 22(null): 61.

de Bruyn, C. (1698). Ierusalem. door de vermaardste deelen van Klein Asia, de eylanden Scio, Rhodus, Cyprus, Metelino, Stanchio, &c. mitsgaders de voornaamste steden van Ægypten, Syrien en Palestina.

de Forbin, L. N. P. A. (1819). Voyage dans le Levant en 1817 et 1818 / par M. le C.te de Forbin.

Dogangum, A. (2008). Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering 6(null): 505.

Fabri, F. and A. Stewart (1480). The Book of the Wanderings of Brother Felix Fabri.

Hasselquist, F. (1766). Voyages and Travels in the Levant in the Years 1749, 50, 51, 52.

Henniker, F. (1823). ‘Jerusalem from the Cave of the Apostles on the Mount of Olives (1822)’ in Notes during a visit to Egypt, Nubia, the oasis Boeris, Mount Sinai and Jerusalem.

Hinzen, G. K. (2013). Seismological Research Letters 84(null): 982.

Ish-Shalom, M. (1965). Christian Travels in the Holy Land: Description and Sources on the History of the Jews in Palestine.

Jacoby, D. (1986). Cathedra 39(null): 51.

Karniel, G., et al. (2006). New Frontiers in Dead Sea Paleoenvironmental Research.

Layish, A. (1985). Cathedra 35(null): 17.

Mayer, L. (1804). ‘Jerusalem’ in Views in Palestine, from the Original Drawings of Luigi Mayer, with an Historical and Descriptive Account of the Country, and its Remarkable Places.

Mendel, M. (1839). The Book 'Korot Ha‘etim li-Yeshurun' in Eretz Israel.

Michaeli, C. E. (1928). Construction and Industry 11–12(null): 9.

Modena, C., et al. (2010). Seismic Assesment of the Monumental Historical Complex on Mount Zion (‘Tomb of David’ and ‘Cenaculum’).

Motosaka, M. and A. Somer (2002). Journal of Seismology 6(null): 419.

Nee'man, A. and A. Ya'ari (1837). Letters of Eretz Israel.

Nemer, T. and M. Meghraoui (2006). Journal of Structural Geology 28(null): 1483.

Niebuhr, C. (1837). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und den umliegenden Ländern.

Nir, Y. (1985). Cathedra 38(null): 67.

null, n., et al. The Itinerary of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela.

Oliveira, C. S. (2012). Earthquake Engineering and Structual Dynamics 41(null): 19.

Pierotti, E. and T. G. Bonney (1864). Jerusalem Explored: being a description of the ancient and modern city, with numerous illustrations consisting of views, ground plans and sections.

Pococke, R. (1745). A Description of the East and Some Other Countries.

Praver, Y. (1947). Yedi‘ot ha-Hevrah la-Hakirat Erets-Yisra'el ve-‘Atikoteha 14(null): 15.

Quaresmius, F. (1639). Novae Ierosolymae et locorum circumiacentium accurata imago.

Re‘em, A. (2012). Hadashot Arkheologiyot 124(null): 1.

Roberts, D. The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt & Nubia. Drawings made on the spot by David Roberts, R.A. With historical descriptions by the Rev. George Croly, L.L.D. Lithographed by Louis Haghe.

Röhricht, R. (1890). Bibliotheca Geographica Palaestinae : chronologisches Verzeichnis der von 333 bis 1878 verfassten Literatur über das Heilige Land.

Rose, G. (2000). Journal of Historical Geography 26(null): 555.

Rose, G. (2001). Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Interpretive Visual Materials.

Rubin, R. (2006). Journal of Historical Geography 32(null): 267.

Seetzen, U. J. (1854). Ulrich Jasper Seetzen's Reisen durch Syrien, Palästina, Phönicien, die Transjordan-Länder, Arabia Petraea und Unter-Aegypten.

Sezen, H. (2008). Engineering Structures 30(null): 2253.

Sezen, H., et al. (2012). Earthquake Engineering.

Shklov, I. and A. Ya'ari (1837). Letters of Eretz Israel.

Spyridon, S. N. (1938). Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 18(null): 63.

Tirion, I. (1732). Jerusalem, zoo als het tegenwoordig is. Salmon, Th. and M. van Goch, Hedendaegsche historie of … alle Volkere.

Turner, W. (1820). Journal of a Tour in the Levant.

Vilnay, Z. (1965). The Holy Land in Old Prints and Maps.

Vincent, H. and F. M. Abel (1922). Jerusalem Recherches de Topographie, D'archeeolgie et D'histoire.

Willis, B. (1927). To the Acting High Commissioner Lt-Col. G.S Symes.

Zohar, M., et al. (2014). Seismological Research Letter 85(null): 912.

Zohar, M., et al. (2013). Damage Patterns of Past Earthquakes in Israel – Preliminary Evaluation of Historical Sources.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master Jerusalem kmz file | various |