Jerusalem - Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The church in 2010, from left to right: the bell tower (12th century), rotunda (big dome), catholicon (smaller dome), and ambulatory

The church in 2010, from left to right: the bell tower (12th century), rotunda (big dome), catholicon (smaller dome), and ambulatory

Click on Image to open a high resolution magnifiable image in a new tab

Gerd Eichmann - Wikipedia -CC BY-SA 4.0

| Transliterated Name | Source | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Calvary | English | |

| Calvariae | Latin | |

| Calvariae locus | Latin | |

| Golgotha | Greek | Γολγοθᾶ |

Since the report of L. H. Vincent and F. M. Abel in 1922, excavations have been carried out in the church [of the Holy Sepulchre] in 1960 to 1963, on behalf of various Christian communities (in the course of renovation work). The present Church of the Holy Sepulcher is basically the church built by the Crusaders. Upon arriving in Jerusalem, they found the eleventh-century church-an inadequate attempt made in 1042-1048 to renovate the Byzantine Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The Crusaders rebuilt it, here and there incorporating the foundations of the previous building. The Crusader structure is essentially modeled on European churches of the twelfth century: a basilica! church with a transept and an apse containing an altar and surrounded by chapels. Excavations have ascertained that the crypt beneath the Chapel of Saint Helena, as well as the chapel itself, were also built in the Crusader period (and not earlier). However, unlike European churches, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher does not have a nave - instead of it, it incorporates the Byzantine rotunda, which was renovated in the eleventh century. The height of the rotunda dictated the height of the church (25.5 m), and the use of a pointed arch, which became increasingly common in this period. The bulk of the Crusaders' building activities took place in the so-called Holy Garden, which was the open part of the church as far back as the Byzantine period. The Crusader sculpture and molded items, some imported from Europe, the style of the capitals and the local decorative elements, such as the wall mosaics, ceiling mosaics and ornamentation of the arches, constitute the sole example in this country of this type of Crusader art. On the site of the Byzantine basilica (which was never rebuilt) the Crusaders built a monastery for the Augustinian canons who served in the church. The monastery was built around a square courtyard; some of the surrounding buildings are preserved, notably the refectory and parts of the basement of the monastery.

- from Jerusalem - Introduction - click link to open new tab

- Map of the Old City and

its environs from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Map of the Old City and

its environs from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

- Plan of the Church of

the Holy Sepulchre in the Crusader Period from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Plan of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Crusader Period

Plan of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Crusader Period

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Table 1 Plan showing

phases from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. X Constantinian

phase at the end of the IV century (?) from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 1 Constantinian

phase at the end of the IV century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 17 Holy Sepulchre

at the end of the VIII century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 3 High Medieval

phase 1 end of VIII century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 18 Holy Sepulchre

at the end of the X century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 4 High Medieval

phase 2 end of X century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 21 Holy Sepulchre

rebuilt by the Byzantines after the Muslim devastation of 1009 from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 5 Byzantine phase

end of XI century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 25 Holy Sepulchre

after the Crusaders restoration in the second half of the XII century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 6 Crusaders

phase end of XII century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 28 Current Status

Quo of the Building of the Holy Sepulchre overlaid onto an ideal reconstruction of the site at the time of Christ from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 12 Longitudinal cross section looking south from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 42 2D plan of the

ground floor of the Complex of the Holy Sepulchre from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 43 Superimposition

of the 3D point cloud of the roof of the Complex of the Holy Sepulchre with the plan of the ground floor from Tucci (2019)

- Plan of the Church of

the Holy Sepulchre in the Crusader Period from Stern et al (1993 v. 2)

Plan of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Crusader Period

Plan of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Crusader Period

Stern et al (1993 v. 2) - Table 1 Plan showing

phases from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. X Constantinian

phase at the end of the IV century (?) from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 1 Constantinian

phase at the end of the IV century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 17 Holy Sepulchre

at the end of the VIII century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 3 High Medieval

phase 1 end of VIII century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 18 Holy Sepulchre

at the end of the X century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 4 High Medieval

phase 2 end of X century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 21 Holy Sepulchre

rebuilt by the Byzantines after the Muslim devastation of 1009 from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 5 Byzantine phase

end of XI century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 25 Holy Sepulchre

after the Crusaders restoration in the second half of the XII century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 6 Crusaders

phase end of XII century from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 28 Current Status

Quo of the Building of the Holy Sepulchre overlaid onto an ideal reconstruction of the site at the time of Christ from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 12 Longitudinal cross section looking south from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 42 2D plan of the

ground floor of the Complex of the Holy Sepulchre from Tucci (2019)

- Fig. 43 Superimposition

of the 3D point cloud of the roof of the Complex of the Holy Sepulchre with the plan of the ground floor from Tucci (2019)

- from Tucci (2019)

| Phase | Date | Period | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | II–IV century AD | Roman | The Hadrianic building. |

| II | IV century AD | Constantinian | The Constantinian Complex. |

| III | XI century AD | Medeival | Restorations by Constantine Monomachus. |

| IV | XII century AD | Crusader | Crusader transformation. |

| V | XX century AD | Modern | Modern restorations. |

- from Tucci (2019)

| Date | Period / Authority | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | Roman | Crucifixion | Probable year of Jesus’ crucifixion. |

| 135 | Roman – Hadrian | Pagan Temple | Emperor Hadrian orders construction of a temple to Venus in the area of the garden of Golgotha. |

| 326 | Constantinian | Clearance of Golgotha | Empress Helen arrives in Jerusalem and orders clearance of the Golgotha area. Construction of the Basilica ordered by Constantine begins. |

| 335 | Constantinian | Dedication | Dedication of Constantine’s Basilica. |

| 614 | Persian invasion | Fire | The Persians set fire to the Basilica. |

| 634–638 | Byzantine / Early Islamic | Restoration | Modestus orders restoration of the building. Caliph Omar occupies Jerusalem (638). |

| 800 | Early Islamic | Earthquake | An earthquake destroys the Anastasis dome. |

| 815–966 | Early Islamic | Decline | Decline of the Sanctuary owing to fires and pillaging. |

| 1009 | Fatimid – al-Hakim | Destruction | Caliph al-Hakim orders destruction of the complex. |

| 1042–1048 | Medieval | Reconstruction | Emperor Constantine Monomachus orders reconstruction of the Basilica, partly altering its layout. |

| 1130–1149 | Crusader | Reconstruction | The Crusaders continue reconstruction of the Sanctuary. |

| 1188 | Ayyubid – Saladin | Closure | Beginning of decline: Saladin closes the Basilica to worship. |

| 1246 | Islamic administration | Custody | The keys are entrusted to two Muslim families. |

| 1555 | Franciscan | Consolidation | Consolidation work by the Franciscans on the Aedicula and dome. |

| 1808 | Ottoman | Fire | Fire in the Basilica. |

| 1810–1837 | Ottoman (Comminos) | Renovation | Parts of the building shored up and renovated in a rough-and-ready manner. |

| 1867 | Ottoman | Metal dome | Anastasis dome renovated in metal (architect: Mauss). |

| 1927 | British Mandate | Earthquake damage | An earthquake damages the complex. |

| 1934 | British Mandate | Stabilization | All building parts shored up. |

| 1961 | Modern | Restoration | Start of restoration work commissioned by all proprietary Communities. Archaeological excavations by Father Corbo. |

| 1997 | Modern | Dome restoration | Restoration of Anastasis dome and of washroom areas. |

| 2016–2017 | Modern | Shrine restoration | Restoration of the Shrine of the Tomb of Christ (National Technical University of Athens). |

- from Tucci (2019:33,35)

The Emperor appointed Dracilianus, the Governor of the province, to organize technicians and everything necessary to build such a multi-partite architectural complex: the small outcrop of rock which housed the Tomb of Jesus became the centre of a grandiose semi-circular mausoleum with a façade, later called the Anostasis (Resurrection); to the east there was a courtyard open to the sky surrounded on three sides by a colonnaded portico, where, in the south-east corner, the Rock of Calvary stood. On the eastern side of this triportico stood a grandiose Basilica for liturgical ceremonies, called the Martyrium (Witness), which, with a colonnaded narthex, gave onto the main road of the city. Eye-witness accounts of the Basilica, now in use, can be read in the catecheses of Bishop Cyril of Jerusalem (347–348 AD), and in reports by pilgrims, as noted earlier.

These include the famous description of the Sunday service at the Holy Sepulchre by the pilgrim Egeria: "When it is the sixth hour, we go before the cross, whether it rains or whether it is very hot. The place is in the open; it is a kind of very large and fine atrium standing between the cross and the Anastasis" (Peregrinatio Aetheriae, 381–384 AD), and the later description of Calvary from the account by the Anonymous Pilgrim from Piacenza: "From the sepulchre to Golgotha there are eighty steps. One climbs up steps, on one side only. There the Lord ascended to be crucified" (Itinerarium, 560–570 AD).

After the fire by the Persians in 614, on the occasion of the restoration by the monk Modestus, the rock of Calvary was enclosed within a chapel, as reported by the pilgrim Arculf, bishop of Gaul, in De Locis Sanctis (670–680 AD). Nothing basically changed with the arrival of the Arabs in 638. The Patriarch of Alexandria, Eutychius, gave credit to the far-sightedness of Caliph Omar ibn al-Khattab for having respected the Christian nature of the Holy Sepulchre site. Eutychius narrates that, while he was visiting the Basilica, when the time came for prayers, Omar refused the invitation from Patriarch Sophronius to pray inside, fearing that it might be turned into a mosque later on. In return, the Caliph asked for a place in the city where a mosque could be built, and the Patriarch indicated the temple esplanade which had been abandoned for centuries (Annales, 938–1034 AD).

A violent earthquake at the start of the 9th century damaged the Anostasis dome. The damage was repaired in 810 by Patriarch Thomas. The danger of a new arson attack was averted in 841, and the consequences from the construction in 935 of a mosque almost backing onto the Basilica were limited. In 938, and again in 966, the complex suffered two serious fires. However, the damage in each case affected wooden parts, which could be repaired, although with sizable sacrifices on the part of the Christian community in Jerusalem.

In the year 1009 the Caliph of Egypt, al-Hakim, gave orders to destroy the monument down to its foundations. The historian Yahia ibn Sa'id of Antioch tells that "the pious work began on Tuesday, the fifth day before the end of the month of Safar in the year 400 of Egypt (1009 in the Christian era). Only those parts that were much harder to destroy were spared" (Annales, 938–1034 AD). It began from the plinth of the rock in which the tomb of Jesus was conserved, which was smashed to pieces. The dome followed, and the upper parts of the structures, which were systematically demolished, until the rubble itself prevented the continuation of the work.

- from Tucci (2019:87-91)

| N° | Date (CE) | Source | References to the Anastasis and the Aedicula |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 325 |

EUSEBIUS, De Constantini laudibus (335); De Vita Constantini (337) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

Beginning of the Council of Nicaea, organized according to Emperor Constantine’s wishes to favour the Church ecumenical and doctrinal unity. |

| 2 | 325-326 |

EUSEBIUS, De Vita Constantini (337) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

At the invitation of Emperor Constantine, the Bishop of Jerusalem Macario oversees the construction works for a sanctuary on the site of the Passion of the Christ. According to tradition, the area of the Golgotha was then occupied by the Roman Capitolium of Aelia. After starting the excavation of the Temple of Jupiter, they found the Tomb of the Christ. |

| 3 | Before 328 (?) |

EUSEBIUS, De Vita Constantini (337) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He describes the Cave (Tomb) and the Monument (Aedicula). He says that they are inside a building and that it is necessary to walk «in the open air» to enter the porticoed courtyard (Triportico). |

| 4 | 327-328 |

EUSEBIUS, De Vita Constantini (337) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

Helena, mother of Constantine, arrives in the Holy Land to oversee the construction works of the basilicas of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Eleona on the Mount of Olives, both wanted by the Emperor. |

| 4 bis | 327-328 |

AMBROSIUS MEDIOLANENSIS, De obitu Theodosii oratio (395-397); IOHANNES Chrysostomus Omelia de Iohanne (second half of the IV century) in: J.P. MIGNE 1867. RUFINUS (second half of the IV century) in: J.P. MIGNE 1844. |

In Jerusalem Helena, follows the suggestions of the local inhabitants (Rufinus) and, after researching thoroughly, discovers (or more likely she is present at the casual finding) the relics of the True Cross and of the Title of the Cross (G. Chrysostomus) of the Passion inside a cistern (spelunca). |

| 5 | 333 |

Itinerarium Burdigalenses (333) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the Cave of the Tomb where the Basilica (the Anastasis) was built. Behind the Basilica there is a pool used for baptizing (probably the Pool of the Tower). |

| 6 | 335 |

EUSEBIUS, De Vita Constantini (337) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

Consecration of the Martyrium and the Anastasis. |

| 7 | 347-348 |

CYRILLUS, Catechesibus (347 - 348) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the Church of Resurrection (Anastasis), where the Tomb of Christ is excavated into the rock. The church atrium has been pulled down by Constantinian workers to build up the Aedicula. |

| 8 | IV century |

Ivory plate belonging to the Trivulzio Collection Milan: museo del Castello Sforzesco. |

Representation of the Constantinian Aedicula or the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or a synthesis of both (squared façade with high cornice decorated with acanthus leaves, on the top a lantern tower with a conical roof and windows). |

| 9 | Last twenty years of the IV century (385-388 Gamurrini; 390-395 Geyer) |

EGERIA (AETHERIA). manuscript found in Arezzo library; J.F. GAMURRINI (edited by), S. Silviae ad Loca sancta peregrinatio, 1888. See: E. GIANNARELLI (edited by), Egeria, Diario di viaggio, Milano 2000. |

She mentions the Anastasis and describes liturgies and the complex of gates surrounding the Tomb. |

| 10 | IV-V centuries |

Ivory plate in Munich Munich: Bayerisches Nationalmuseum. |

Representation of the Constantinian Aedicula, probably inspired by the Trivulzian plate (squared façade with high cornice decorated with acanthus leaves and niches with statues; on the top, a lantern tower with a semi spherical roof, blind arches supported by columns, windows, and medals). |

| 11 | 440 |

EUCHERIUS, Epistula ad Faustum de locis sanctis (440) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the Anastasis as the sanctuary of the Resurrection. |

| 12 | 530 |

Brevarius de Hierosolyma (530); in: Codice Sangallese (811) and Codice Ambrosiano (XI century). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the Anastasis, the Basilica of the Holy Resurrection. |

| 13 | 530 |

THEODOSIUS, De situ Terrae Sanctae (530) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the Sepulchrum Domini (Tomb and Aedicula), and the altar made of stone that stands before it; he gives the distance from the Calvary (XV steps). |

| 14 | 527-565 |

Madaba Mosaic Map Madaba (Jordan): Greek-Orthodox church of Saint George. |

It represents the golden semi spherical dome (of the Anastasis). |

| 15 | 570 |

ANONIMUS PLACENTINUS, Antonini Placentini Itinerarium (570) in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the monumentum of Jesus Christ’s Tomb and the altar made

of stone that is in front of it. He notes the distance between the Sepulchre and the Golgotha (LXXX gressi). He mentions the following relics: the Sponge, the Reed, the Calyx. |

| 16 | VI-VII century |

Bobbio Ampullae Bobbio (Piacenza): museum of Saint Columban Abbey. |

They represent the Aedicula with seven sides, with blind arches supported by small columns, atrium, gates, and the pyramidal roof. |

| 17 | VI-IX century | Lateran miniature | It represents the Aedicula as on the Monza and Bobbio ampullae, covered by the semi spherical dome of the Anastasis. |

| 18 | 603 - 604 |

SOPHRONIUS, Anacreontia Carmina XIX et XX (603-604). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He defines the Anastasis as a «basilica full of the sound of monks’ chant night and day, recently redecorated. He mentions the Sponge, the Reed, and the Lance “located in high” (on the upper galleries?)». |

| 19 | 614 |

EUTYCHES, Annales seu liber historicus a tempore Adami ad annum Hegirae Islamiticae, III (933 – 940). in: J.P. MIGNE 1867. |

Persians invade Palestine: the Holy Sepulchre is set to fire and the relic of the True Cross is moved to Persia. |

| 20 | 625 |

EUTYCHES, Annales seu liber historicus a tempore Adami ad annum Hegirae Islamiticae, III (933 – 940). in: J.P. MIGNE 1867. |

Modesto, abbot of Saint Theodore monastery, says that the restoration works of the Jerusalem sanctuaries damaged by Persians, which he directed, are completed. The works have been done thanks to offerings collected in Palestine by himself. |

| 21 | 638 |

EUTYCHES, Annales seu liber historicus a tempore Adami ad annum Hegirae Islamiticae, III (933 – 940). in: J.P. MIGNE 1867. |

The Arabian caliph Omar conquer Jerusalem, in a peaceful and bloodless way. When he reaches the Holy Sepulchre, he does not enter, instead he stops to pray in the atrium, which is declared a Muslim place of worship. |

| 22 | 638 |

Kufic inscription (X century ca) set in a wall of the Martyrium ancient atrium, nowadays part of the Russian hospice in Jerusalem. |

— |

| 23 | VII century |

Anonymous Armenian description of the Holy Places (probably VII century). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

It contains information about the Tomb, made of cut rock, and about the church «shaped as a cupola». That contains it (high and wide 100 ells). The church has two floors, each supported by twelve columns. The Lance, the Sponge, and the golden Calyx of the Christ are displayed on the upper gallery. |

| 24 | 668 |

ARCULFUS, Adammani de locis sanctis libri tres (670). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He describes the Anastasis as a «round church built above the Tomb of the Lord», the Aedicula, the amount of altars (two of them are cut into the rock that closed the Tomb) and of doors, and the position of corridors. He mentions the church of Saint Mary is located «a dextera» of the Anastasis, thus demonstrating that, liturgically, the latter was directed towards east. |

| 25 | 668 |

Drawing by Arculfus Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale. |

It represents the Aedicula and the Anastasis, both round and divided by gates. As for the latter, it also represents the three apses, the altars, and the doors directed towards south-east and north-east, which open onto a rounded path all around the Basilica. |

| 26 | 723-726 |

WILLIBALDUS, Itinerarium Sancti Willibaldi (written after his death, 786). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He describes the Tomb and the Aedicula and talks about the big stone that originally blocked the entrance to the Sepulchre. |

| 27 | 800 |

Annales regni Francorum; EGINHARD, Vita Karoli (775 - 840), in: L. HALPHEN 1967. |

Charlemagne becomes Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. A delegation (including the presbyter Zechariah, a Benedictine from the Mount of Olives and a monk from the monastery of San Saba) sent by the Patriarch of Jerusalem brings the symbols of the Protectorate: the keys of the Holy Sepulchre, of the city of Jerusalem, and of the Mountain (Mount of Olives?). |

| 28 | 803 |

Annales regni Francorum; EGINHARD, Vita Karoli (775 - 840), in: L. HALPHEN 1967. |

A Frankish delegation guided by the missus Radbertus is sent to Jerusalem and to the court of Baghdad, where the caliph Harun al-Rasid accepts Charlemagne’s requests and allows the Holy Roman Empire to protect the sanctuary of the Holy Sepulchre. |

| 29 | 807 |

Annales regni Francorum; EGINHARD, Vita Karoli (775 - 840), in: L. HALPHEN 1967. |

A delegation including a representative of Harun al-Rascid and two representatives of the patriarch of Jerusalem visits Charlemagne bringing precious gifts. |

| 30 | Between 807 and 820 |

EUTYCHES, Annales seu liber historicus a tempore Adami ad annum Hegirae Islamiticae, III (933 – 940). in: J.P. MIGNE 1867. |

When Thomas is patriarch, a severe earthquake hits Palestine and damages the Anastasis. The Church of Jerusalem gets a mortgage on its properties to rebuild the wooden dome of the Basilica. |

| 31 | Between 808 and 810 |

Commemoratorium de casis Dei (rapporto stilato dagli emissari di Carlo Magno per accertare le necessità materiali delle basiliche della Terrasanta). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

It mentions the ecclesia de Sepulcro Domini and gives the distance between the Aedicula atrium and the nave of the Adam’s crypt (XXXIII dexteri). |

| 32 | IX century |

EPIPHANIUS MONACHUS, Enarratio Syriae (a. 750-800 per Schneider; a. 840 per Roericht). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the Sepulcrum Domini. |

| 33 | 843 | Rerum et imperatorum Germaniae e stirpe Carolingiorum, in: MONUMENTA GERMANIAE HISTORICA, Diplomata, 1826. | The sons of Louis the Pious, Lothar, Carlo, and Louis, divided the Holy Roman Empire into three parts: kingdom of France (Charles), kingdom (Louis) and kingdom (with the imperial title) of Frisia, Alsace, Burgundy, and Italy (Lothar). |

| 34 | 870 |

BERNARDUS MONACHUS, Itinerarium (a. 870). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the western church «in cuius medio est Sepulcrum Domini» and describes the Aedicula, surrounded by nine columns. |

| 35 | 881 |

EUTYCHES, Annales seu liber historicus a tempore Adami ad annum Hegirae Islamiticae, III (933 – 940). in: J.P. MIGNE 1867. |

The patriarch of Jerusalem, Elias, writes a letter «to all the kings from Charlemagne’s stock and to the Western clergy», to collect offerings to pay back the debt the Church accumulated «to rebuild several sanctuaries». |

| 36 | IX-X century |

Typicon Anastasis (manuscript, 1122). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

It mentions the Holy Sepulchre and the church of the Holy Resurrection, inside which there is the Santo Bema. That is to say that the Anastasis became the Chair of the Patriarch (which was previously inside the Martyrium), the place where the main liturgies are celebrated as well as the most important church within the complex (see n° 9). |

| 37 | Between 929 and 937 |

EUTYCHES, Annales seu liber historicus a tempore Adami ad annum Hegirae Islamiticae, III (933 – 940). in: J.P. MIGNE 1867. |

— |

| 38 | 966 |

Patrologia Orientalis in: R. GRAFFIN, F. NAU, 1901. |

The governor of Palestine, Mohammed ibn Ismail as-Sanagi, kills the patriarch of Jerusalem and sets the Anastasis on fire. The fire causes the collapse of the dome and several damages. |

| 39 | 1006 |

Patrologia Orientalis in: R. GRAFFIN, F. NAU, 1901. |

The patriarch of Jerusalem, Orestes, completes the reconstruction works of the Anastasis wooden dome. |

| 40 | 1009 |

GUGLIELMO MALMESBURIENSE in: J.P. MIGNE, 1844. |

The Muslim governor Al-Hakim orders to destroy the Holy Sepulchre. |

| 41 | XI century |

YAHIA-IBN-SAID Annales. in: R. GRAFFIN, F. NAU, 1901. |

It tells about the destruction of the church of Resurrection, ordered by Hakim and started on August 25th, 1009. The Anastasis is severely damaged and the Aedicula completely destroyed. |

| 42 | 1014 |

Patrologia Orientalis in: R. GRAFFIN, F. NAU, 1901. |

Mary, mother of al-Hakim and fervent Christian, starts the reconstruction of the «Temple of the Christ», destroyed on his son’s command. |

| 43 | 1020 |

Patrologia Orientalis in: R. GRAFFIN, F. NAU, 1901. |

The Christian Community of Jerusalem obtains the right to celebrate liturgies «inside the fence of the Quoyoma» (Resurrection). |

| 44 | 1021 |

Patrologia Orientalis in: R. GRAFFIN, F. NAU, 1901. |

The governor of Palestine, el-Zahir, succeeded to al-Hakim, signs a treaty with Constantinople. Among other conditions there is the concession to the Byzantine Emperor to rebuild the Basilica of the Anastasis. |

| 45 | 1023 |

Patrologia Orientalis in: R. GRAFFIN, F. NAU, 1901. |

The patriarch of Jerusalem, Nicephorus, visits the court of Constantinople to inform the Emperor Basil about the restoration works of the Anastasis and of other Palestinian churches that have been destroyed. |

| 46 | 1035-1042 |

NASSIRI KHOSRAU, Sefer Nameh. Relation du voyage en Syrie, en Palestine. (1035 - 1042). in: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He tells of a great church that can host up to eight thousand people, a favourite destination for pilgrims from Rome. He describes the paintings that decorate it and mentions several other chapels. |

| 47 | 1037-1038 |

Patrologiae cursus completus, Series Latina in: J.P. MIGNE 1844. GUILLIELMUS TYRENSIS, Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum (up to year 1143). In: Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Parigi 1841-1906. |

The Byzantine Emperor Michael IV concludes a formal agreement with the caliph al-Mustansir, in which it is stated that the Anastasis will be rebuilt at the expenses of the imperial crown. |

| 48 | 1048 |

GUILLIELMUS TYRENSIS, Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum (up to year 1143). In: Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Parigi 1841-1906. |

The Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX, Michael’s successor, completes the restoration works of the Holy Sepulchre. |

| 49 | 1099 |

FULCHERIUS CARNOTENSIS, Gesta peregrinationum Francorum cum armis Hierusalem peregrinantium (1095 - 1125); ALBERTUS AQUENSIS, Historia Hierosolymitanae expeditionis (1095 - 1120); GUILLIELMUS TYRENSIS, Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum (up to year 1143). In: Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Parigi 1841-1906. |

Crusaders conquer Jerusalem. |

| 50 | 1102-1103 |

SAEWULFUS, Peregrinatio ad Hierosolymam et Terram Sanctam (1102-1103). In: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He mentions the church of the Holy Sepulchre and the two siding chapels: Saint Mary (on whose western wall there is the miraculous painting of the Virgin Mary) on the north side and Saint John on the south side. On the southern side of the latter there is the monastery-baptistery of the Holy Trinity and the chapel of Saint James. |

| 51 | 1106-1107 |

DANIEL ABBAS, Vie et pèlerinage (1106-1107). In: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He talks of the church of Resurrection, with a round shape, a wooden dome, and mosaic decorations. He describes the Sepulchre as a little cave, in front of which lies the block overturned by the angel. The Aedicula is surrounded by twelve columns and has a slim tower with a dome on top. In the courtyard, beneath the Anastasis eastern apse, there is the Omphalos. It is covered by a ciborium decorated with mosaics. |

| 52 | ante 1143 |

GUILLIELMUS TYRENSIS, Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum (up to year 1143). In: Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Parigi 1841-1906. |

He mentions the round church of the Holy Resurrection, dark inside, and covered by a framed roof with an oculo in the middle. |

| 53 | 1130-1150 |

De situ urbis Jerusalem (1130-1150). In: D. BALDI, 1982. |

It mentions the ecclesia Sepulcri, with a round shape, very beautiful, and with four doors facing East. |

| 54 | 1149 |

Epigraph (no longer existing) on the entrance arch to the chapel of the Golgotha. See: M. BIDDLE, 2000. |

— |

| 55 | 1163 |

Tomb of Baldwin III, King of Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Church of the Holy Sepulchre. See: M. BIDDLE, 2000. |

— |

| 56 | 1163-1174 |

Epigraph (no longer existing) in honour of Genoeses in the Anastasis eastern apse. See: M. BIDDLE, 2000. |

«Praeponens Ianuensium praesidium». The inscription disappeared during the reign of Almarico, when the apse was pulled down to connect the Constantinian Basilica to the Romanesque Chorus Dominorum. |

| 57 | 1172 |

THEODERICUS, Libellus de Locis Sanctis (1172). In: D. BALDI, 1982. |

He describes the «ecclesia Sepulchri Dominici» founded by Helena (round shaped, with the cave of the Tomb at the centre), the altars, the gates, and the ciborium with its dome. On the north side of the Anastasis there is the chapel of Saint Mary, kept by the Armenians (nowadays by Franciscans), with the ladder before it that connects to the street level. On the left side of the chapel (where the ancient Patriarchica used to be), there is the other chapel of the Holy Cross, kept by the Syrians. On the southern side he mentions the chapel of Saint John the Baptist, below the bell tower, which contains the baptistery. |

| 58 | 1187 | See in general: Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Parigi 1841-1906. | October 2nd, the Salah-al-Din (Saladin) army conquers Jerusalem again and put an end to the crusade domination. |

- The bay'ah was given to Harun ar-Rashid b. al-Mandi — his mother was al-al- Khayzuran — in the same night that Musa al-Nadi died, the night of Friday 14 Rabi al-awwal in the year 170. That night his son al-Ma'mun was born. He entrusted the management of his business to Yahya b. Khalid b. Barmak. During his caliphate he made the pilgrimage to Mecca nine times and he invaded the territories of Rum eight times. He removed his favour from the Barmakees in the month of Safar of the year 187 of the Hegira. His caliphate lasted twenty-three years, two months and sixteen days.

- Leo (IV), son of Constantine, son of Leo, king of Rum, died. After him there was made king of Rum Nicephorus (I), son of Istiraq,96 who asked for a truce from [Harun] ar-Rashid. Ar-Rashid gave him a respite of three years. There ruled in Egypt, in the name of ar-Rashid, Musa b. Isa al-Hashimi, who extended the Great Mosque of Misr at the rear of the building which may still be seen. Ar-Rashid then deposed Musa ibn Isa and entrusted the government of Egypt to Abd Allah ibn al-Mandi. Abd Allah sent as a gift to ar-Rashid a young girl of his choice from among the Yemenis who lived in the south of Egypt. She was very beautiful and ar-Rashid fell intensely in love. The young girl was then hit by a serious disease. The doctors cared for her but no medicine was effective. They said to ar-Rashid: "Send word to your governor in Egypt, Abd Allah, to send you an Egyptian doctor. The Egyptian doctors are more able than those of Iraq to cure this young girl." Ar- Rashid sent word to Abd Allah ibn al-Mandi to choose the most skillful Egyptian doctor and send him to him, telling him about the young girl and of what had happened. Abd Allah sent for Politianus, the Melkite Patriarch of Alexandria, expert in medicine, made him aware of the young girl and the disease that had struck her, and sent him to ar-Rashid. [Politianus] brought with him some Egyptian durum "ka'k",97 and some pilchards. When he arrived in Baghdad and presented himself to the young girl, he gave her some rustic ka'k and pilchards to eat. The young girl recovered her health at once, and the pain disappeared. After that [ar-Rashid] began to order from Egypt, for the sultan's use, durum ka'k and pilchards. Ar-Rashid gave lots of money to the patriarch Politianus and gave him in writing an order which provided that all the churches that the Jacobites had taken away from the Melkites and of which they had taken possession, should be returned. The patriarch Politianus returned to Egypt and got back his churches. The patriarch Politianus died after having held the patriarchal seat for forty six years. After him there was made patriarch of Alexandria Eustathius,98 in the sixteenth year of the Caliphate of ar-Rashid. Eustace was a linen-maker and had found a treasure in the house in which he used to prepare linen. He had embraced the monastic life at "Dayr al-Qusayr", later becoming the superior. He built at "Dayr al- Qusayr" the church of the Apostles, and a residence for the bishops. Later he was made patriarch of Alexandria, held the office for four years and died. After him there was made patriarch of Alexandria Christopher99 in the twentieth year of the Caliphate of ar-Rashid. The patriarch Christopher was hit by hemiplegia and could only move if supported. There was therefore appointed a bishop named Peter after a vote whom the bishops put in place of the patriarch. Christopher held the office for thirty-two years and died. In the eighth year of the Caliphate of ar-Rashid there was made patriarch of Antioch Theodoret. He held the office for seventeen years and died. During the caliphate of ar-Rashid there was, after the afternoon prayer, an eclipse of the sun so intense that you could see the stars, and people stood screaming at the sky imploring God — may His name be glorious! In Khurasan there rebelled against ar-Rashid, Rafi ibn al-Layth and occupied it. Ar-Rashid invaded Khurasan, but at Gurgan he became ill and stopped at Tus, sending al-Ma'mun to Merv to the head of a large army.

- Ar-Rashid died in the month of Jumada al-Akhar in the year 193 [of the Hegira], at the age of forty-six. He was buried in Tus, in the city of an-Nirat.100 The sons who were with him, those of his family and his commanders gave the bay'ah to his son Muhammad ibn Zubaydah. Al-Fadl ibn ar-Rabi returned with his men to Baghdad. Ar-Rashid was of perfect stature, handsome of face, with a black and flowing beard which he used to cut when he went on pilgrimage. The leaders of his bodyguard were al-Qasim ibn Nasr b. Malik first, then Hamza ibn Hazim b. Obayd Allah b. Malik, then Hafs ibn Umar b. ash-Shugayr. His hagib was Bishr ibn Maymun b. Muhammad b. Khalid b. Barmak. Then al-Fadl ibn Rabi regained this position.

96 Elsewhere "Istabraq"; i.e.

Stauracius.

97 A collective term for various

pastries and pretzels.

98 813–817 AD.

99 817–848.

100 Possibly "Iran" is meant?

- The news of the death of ar-Rashid arrived in Baghdad on Wednesday, twelve days before the end of Jumada al-Akhar. The crowds gathered, his son Muhammad went out in the pulpit, and invited them to mourn his death. The people gave him the bay'ah on that day. Then there appeared strong differences between him and his brother al-Ma'mun. The mother of Muhammad al-Amin was called Umm Jaffar,101 and was the daughter of Abu Jaffar al-Mansur. Muhammad al-Amin sent Ali ibn Isa b. Mahan to Khurasan to fight against al-Ma'mun, who sent against him, from Merv, Zahir ibn al-Husayn b. Sa'b al-Busagi. Zahir killed Ali ibn Isa, put to flight the armies of Muhammad al-Amin and came to Baghdad, where he was joined by Hartama ibn A'yan and Humayd ibn Abd al-Hamid at-Tusi. Al-Ma'mun was hailed as caliph in Khurasan in the year 196. The civil war then moved to Baghdad.

- Muhammad al-Amin was killed in Baghdad on Saturday, five days before the end of the month of Muharram of the year 198 [of the Hegira]. His caliphate, until the day of his murder, had lasted four years, eight months and six days. He was killed at the age of twenty-eight years.

- Nicephorus, son of Istabraq, king of Rum, died. After him there reigned over Rum Istabraq,102 son of Nicephorus, son of Istabraq.

- In the third year of the caliphate of Muhammad al-Amin there was made patriarch of Jerusalem Thomas, nicknamed Tamriq.103 He held the office for ten years.

- Muhammad al-Amin was handsome, with a perfect constitution, white-skinned, fat, strongly built, with thin fingers. His body was buried at Baghdad and his head brought to Khurasan. The leader of his bodyguard was Ali ibn Isa b. Mahan and his hagib al-Fadl ibn ar-Rabi, who was also his confidential adviser.

101 I.e. Zubaydah, the wife of Harun ar-Rashid.

102 Stauracius, emperor of the East from 26 July 811 to

2 October 811.

103 807-821.

- In Khurasan, in the year 196 of the Hegira, the bay'ah was given to al-Ma'mun, i.e. 'Abd Allah ibn Harun ar-Rashid b. Muhammad al-Mandi b. 'Abd Allah Allah b. Harun b. Al-Mansur — his mother was Maragil and belonged to one of the most illustrious families of al-Badalshah.

- Muhammad al-Amin, brother of al-Ma'mun, was killed in Baghdad at the end of the month of al-muharram of the year 198. Zahir ibn al-Husayn was in Baghdad in the east, Hartama in the west and Humayd b. 'Abd al-Hamid at-Iasi was four parasangs from Baghdad. [Al-Ma'mun] entrusted the government of Iraq to al-Husayn ibn Sahl (66) around whom the provinces of Iraq and others had been united. The countries were all in turmoil. All the time a pretender came from one side or another, and from other lines. Al-Ma'mun then left Khurasan and went to Baghdad during the month of Safar of the year 204. He gave the command of the guards to Zahir ibn al-Husayn and granted his protection to everyone. Then he defeated Ibrahim ibn al-Mandi, nicknamed Ibn Shiklah, who had been proclaimed caliph and had assumed the title of prince of the believers. He sent his troops to the countries in revolt, and reduced all the provinces to obedience. Everyone submitted and obeyed him, and every insurrection was thus subdued.

- Abu Ishaq Ibrahim ibn al-Mandi, better known by the name of Ibn Shiklah, said: "Before the killing of Muhammad al-Amin we used to exchange letters in this form: "From A, son of B, to C, son of D." or: "From the father of A, to the father of C,"104 or: "To the father of A from C, son of D.", without introducing any formula of greeting in the heading." And he records that the governor of Baghdad sent him a letter from DhO'r-Ri'asatayn, i.e. al-Fadl ibn Sahl, whose heading was like this: "To Abu Ishaq — may God Most High preserve him! —, from Abu'l-'Abbas". Abu Ishaq tells us also: "When I saw that heading, I sent the letter to my uncle Sulayman, believing that he would see it as something new. But when he received my letter, he sent his hagib with a letter of DhO ar-Ri'asatayn the same as the heading of what he had written to me. It was since then that greeting formulas have been used in the headings of letters".

- Muhammad ibn as-Sari b. al-Hakam was in Egypt [as governor]. He rebelled, refused the authority of al-Ma'mOn and seized Egypt. His father, as-Sari ibn al-Hakam, had previously had his hands on Egypt before him. Al-Ma'mun then sent 'Ubayd Allah ibn Zahir to Egypt. When he arrived in Egypt, Ubayd Allah offered peace to Ibn as-Sari, who was governor at the time of his arrival in Egypt, made his entrance to Misr, received the [tribute] money, and sent it to al-Ma'mOn in Baghdad. 'Ubayd Allah expanded the great Misr Mosque, after writing to al-Ma'mOn and having it approved, adding the "dar ar-Raml", of which he completed the construction, and leaving incomplete the "Dar ad-Darb". The dome of the church of the Resurrection in Jerusalem was in a bad condition and was threatening to collapse.

- Palestine and Jerusalem were suffering a severe famine and the invasion of countless grasshoppers. Many died of hunger. The Muslims fled from Jerusalem because of the famine and there was only a scattering in the city. The patriarch of Jerusalem Thomas, known as Tamriq, seized the opportunity — that Jerusalem had been abandoned by the Muslims — and sent men to Cyprus to cut fifty cedar and pine logs and bring them to Jerusalem. There was a man called Bukam, of Burah of Egypt, who was very wealthy. He sent a large sum of money to Thomas, patriarch of Jerusalem, to use it to repair the dome, asking him not to take any money from others and to turn to him alone if he needed any more money. Thomas demolished the dome piece by piece, by hand, replacing the beams upon which he then built the new construction. In a dream, Patriarch Thomas saw forty men come out of one of the columns that held up the dome of the Resurrection, who supported the cupola with their hands so that it would not collapse. The column was the one found under the temple. He awoke and said, "Those forty who the column supported must be the Forty Martyrs." He made forty logs support the dome, as thick as a man's arms could encircle, according to the number of the Forty Martyrs. The column was the one in front of the ambo, next to the altar, on the south side. When the feast of the Forty Martyrs came round, they celebrated it in front of that column. After finishing repairing the dome with the logs, attaching one to the others, above and below, Patriarch Thomas made another dome above the dome, leaving enough space between them for a man to be able to walk, and he lined it all over with lead.

- While Ubayd Allah ibn Zahir was returning from Egypt, going to Baghdad, the Muslims complained to him, about the fact that Christians had transgressed the provisions that had been made to list what was not permissible, by demolishing the dome of the Church of the Resurrection. It had been a small dome, but they had enlarged it so much that it was bigger than before, exceeding the Dome of the Rock in height. 'Ubayd Allah ibn Zahir then summoned the Patriarch Thomas and another group of people and put them in prison, while he investigated what they were doing: if what the Muslims had complained about was true, then he would punish them. They were led to prison in the night by an old Muslim who told the patriarch Thomas: "I am able to suggest a way to save you and your companions, with the help of God, and the dome also, provided that you promise to give me a thousand dinars and to pay me, my son and the children of my son, until their extinction and always, an income of the income of this cupola in the measure that the priests and deacons receive it." Patriarch Thomas promised him what he asked and put it in writing. Then the old Muslim said to them, "When they prosecute you and bring evidence against you, you say to them, 'May God save the prince! All I did was repair the part of the dome that needed repairs. And in fact I did it without destroying anything and added nothing to it. Those who depose against me have only been able to say that the dome was smaller than it is now and that I have enlarged it. Well, let the Prince ask them how large was the "small dome" that I am supposed to have demolished, as they say, and how much is this that I am supposed to have built and expanded, so that the Prince can realizes what has been added to its dimensions.' Certainly they will not know how to answer." The next day, when the Patriarch Thomas and his companions were summoned and the Muslims appeared to stand against him, on the expansion of the dome, the Patriarch Thomas refuted them by resorting to that argument. Then Ubayd Allah ibn Zahir said to them: "What he asks is right, and we too are of the same opinion. Let me know what the size of the dome was before it was demolished, and what is the size of the dome." They said: "We will be doing surveys," and they went out. 'Ubayd Allah ibn Zahir went off to Damascus, and patriarch Thomas and his people returned to Jerusalem. The Patriarch Thomas gave the thousand dinars to that old Muslim man and continued to pay to him, to his son and to his son the income of the dome, until there was only a daughter from whom the patriarch of Jerusalem Elijah, son of Mansur, removed that privilege. Patriarch Thomas died and his disciple Basil was made patriarch of Jerusalem, in the seventh year of the caliphate of al-Ma'mun. Basil held the office for twenty-five years and died.

-

In the first year of the caliphate of

al-Ma’mūn, Job was patriarch of Antioch.

He held the office for thirty years.

‘Ubayd Allah ibn Zāhir returned to

Baghdad to al-Ma’mūn, made him aware of

the situation in Egypt and how much he

had done to restore order. Subsequently,

there appeared the Bima – a Coptic word

that means “descendants of the Forties”.

For when the Rūm left Egypt at the time

of the advent of Islam, they left behind

forty men who propagated, multiplied and

reproduced in Lower Egypt, receiving the

name of “Bima”, the descendants of the

Forty. They rebelled and refused to pay

the poll tax and the land tax. Learning

of this, al-Ma’mūn sent to Egypt

al-Mu’tasim at the head of an army. The

Bima faced him and he fought against

them, making great slaughter, and he

routed them, captured their women and

children and carried them off to

Baghdad. After establishing order in

Egypt, al-Mu’tasim returned to Baghdad.

Then al-Ma’mūn went to Egypt together

with al-Mu’tasim and entered on the

night of Friday, 9th of the month of

al-Muharram of the year 217 of the

Hegira. The first day of the month of

Safar, they went to the territory of the

“Bima”, then left and entered Misr and

al-Fustāt on Saturday 14th of the month

of Safar. In the month of Rabī

‘al-awwal of the same year, al-Ma’mūn

left Egypt. After he entered Misr,

al-Ma’mūn had built, on Mount

al-Muqattam, his own residence with a

dome called “qubbat al-Hawà”: With

al-Ma’mūn were some Christian

upholsterers. Because the churches of

the citadel were far from where they

were, they asked al-Ma’mūn permission to

build a church to pray near the “qubbat

al-Hawa”. He granted it. Thus they built

a church to pray, which they called the

church of “Martmaryam” at al-Qantarah,

which is nowadays known as the “Rūm

church”, but previously it was called

the “Church of the Upholsterers”. It is

said that they built it using the

remains of the “Qubbat al-Hawa”.

In Upper Egypt al-Ma’mūn built a hydrometer in order to measure the waters of the Nile, in a place called Shūrāt, at a village called Banūdah, and he repaired the nilometer at Ikhmim. One day there came to al-Ma’mūn, the Christian Bukām of Būrah, the same who sent the money to build the dome of the Resurrection, and asked him to make him governor of the province of Būrah. He was very rich. Al-Ma’mūn answered him; “Become a Muslim, and you will be their lord.” Bukām replied: “The prince of believers has tens of thousands of Muslim officials, but he does not have even one Christian.” Al-Ma’mūn rose and entrusted to him the province of Būrah and its surroundings. Bukām built many beautiful churches in the territory of Būrah. Facing the door of his house there was the main mosque. He said to the Muslims of Būrah: “I’ll build you another big mosque if you destroy that which is in front of my house.” The Muslims replied: “Build another mosque while we continue to pray in this. When you finish building, we’ll pray in it and destroy the other one.” He thus constructed a large and beautiful mosque and when he completed the construction, he said to them: “Be faithful to the word given and demolish the mosque that is in front of my door.” But they answered him, “Our religion does not allow us to pull down a mosque in which we have already prayed, where we gathered at the voice of the muezzin and in which we held the Friday prayer together. No, our religion does not allow it.” The mosque therefore remained where it was and in Būrah there were two mosques where they gathered for the rite of prayer. The Muslims prayed on one Friday in one and one Friday in the other. Bukām used to dress in black and girded with a sword and went riding a horse preceded by his men. When he came to the mosque, he stopped and a delegate went in, who was a Muslim, to direct the prayer and hold the prayers in the caliph’s name, returning, once he had finished, to him. The Christians continued to dress in black and to ride until the time of al-Mutawakkil. Al-Ma’mūn returned to Baghdad. - Constantine fought against Nicephorus, son of Istabrāq, and defeated him, becoming king of the Rūm. Al-Ma’mūn made three campaigns, the last of which was in the year 218. Then he came to al-Yadidūn, fell ill and died. He was carried to Tūs, and was buried there. His caliphate – after he was saluted as caliph in Khurāsān – lasted twenty-two years. He died at the age of forty-nine years in the month of Rağab in the year 218. He was of a whitish-rosy complexion, handsome, and had a long beard, already white in many places. The chiefs of his bodyguard were Zuhayr ibn al-Musayyab as-Sabbi, then Zahir ibn al-Husayn. Among his guards the command was held by Ishāq ibn Ibrāhūn. His hāgib while he was in Khurāsān was al-Husayn ibn Abi Sa’id. Later his hāgib was ‘Ali ibn Sālih, sāhib al-musallā. The influential ministers at the beginning of his caliphate were Dhū’r-Ri’āsatayn al-Fadl ibn Sahl and after that many others, including al-Husayn ibn Sahl, Umar ibn Sa’id and Ahmad ibn Abī Khālid.

104 In his lifetime King Hussein of Jordan, father of the current ruler King Abdullah, used to be referred to as "Abu Abdullah", i.e. "Father of Abdullah".

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Church of the Holy Sepulchre |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Church of the Holy Sepulchre |

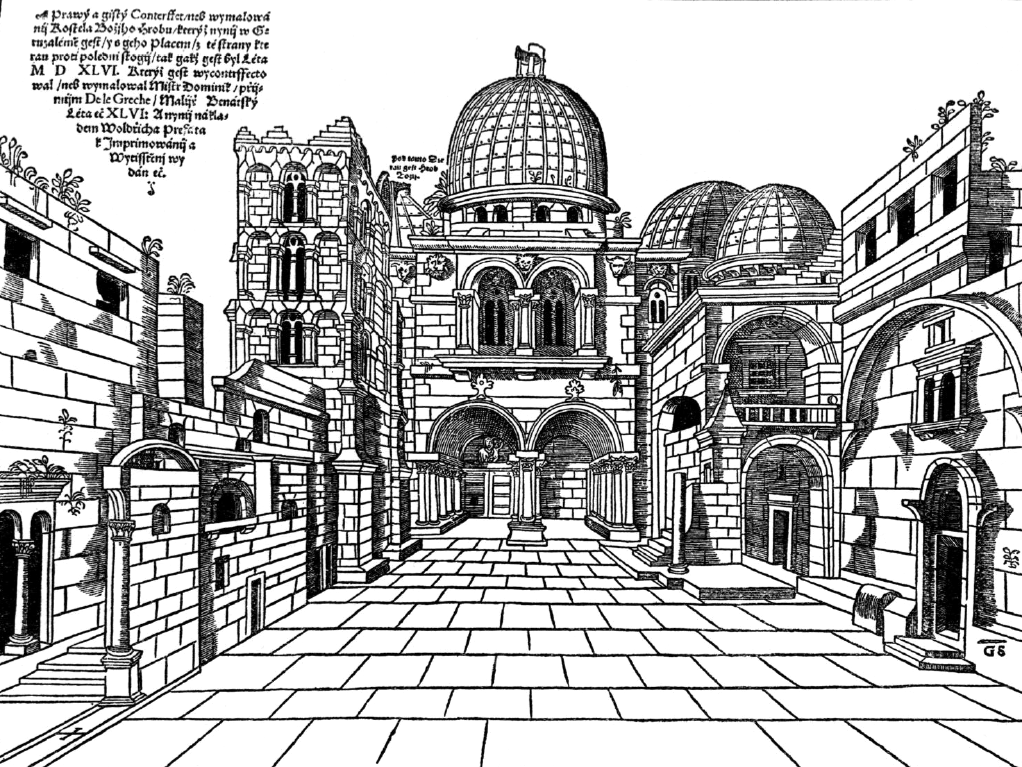

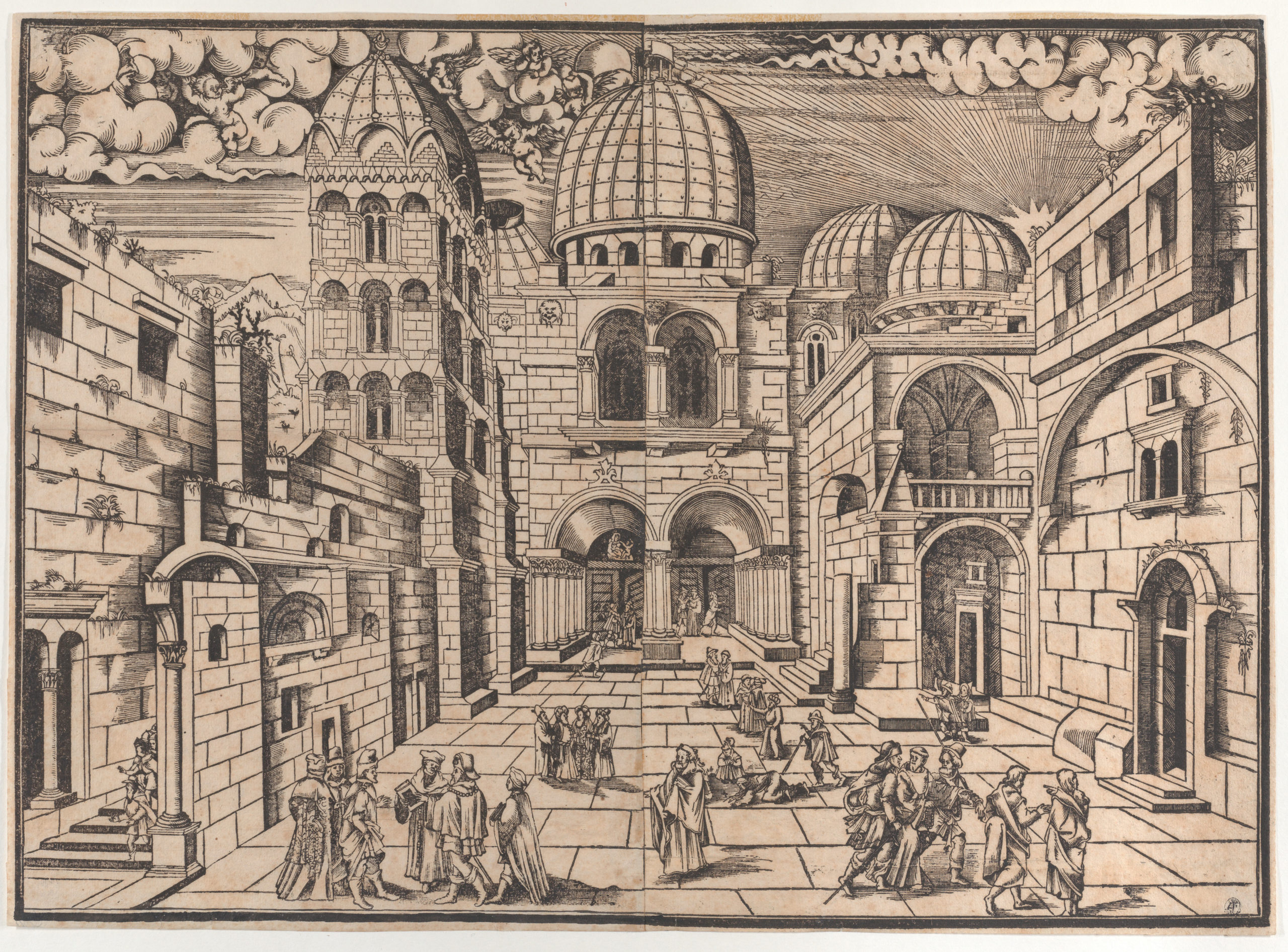

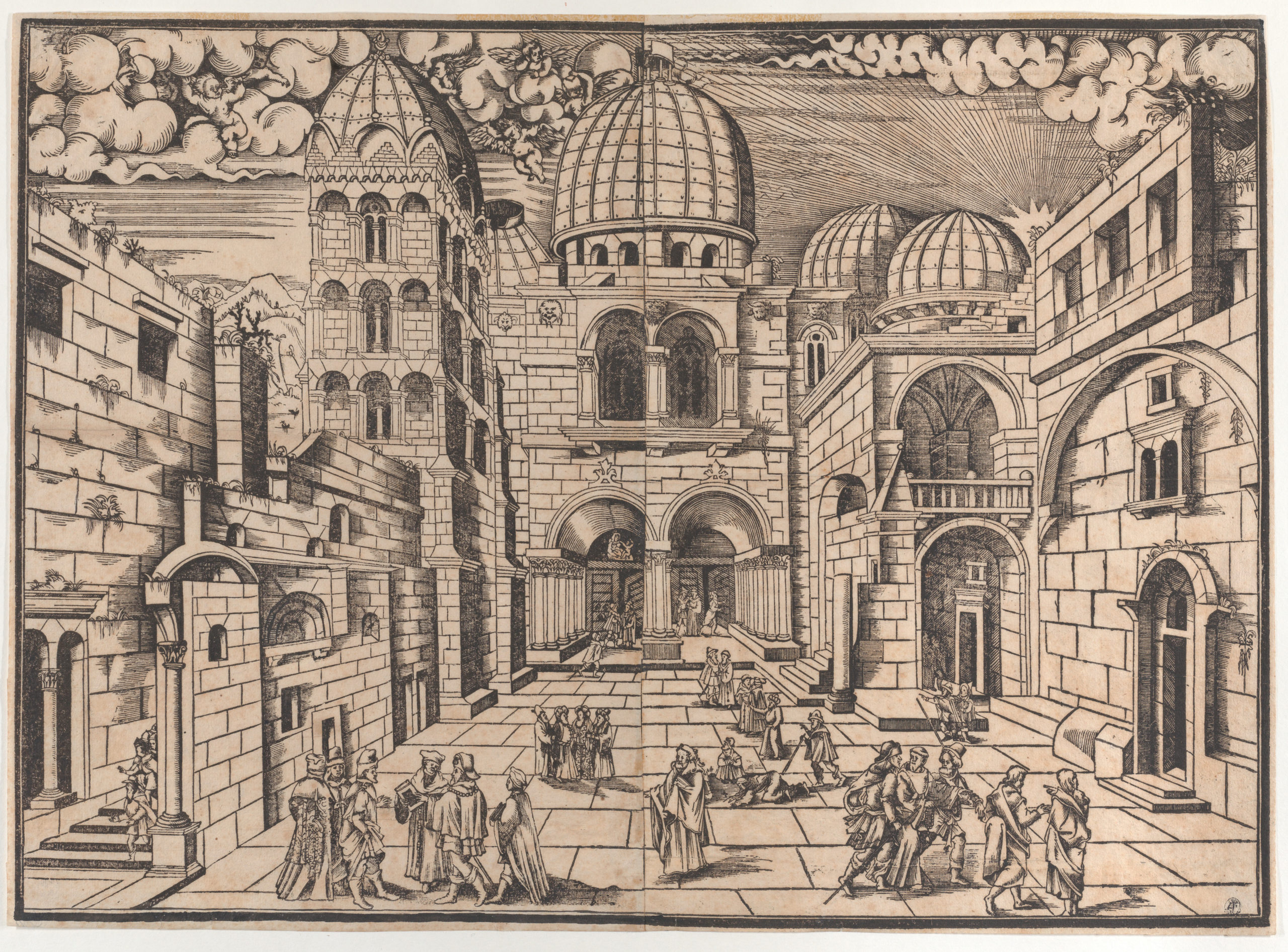

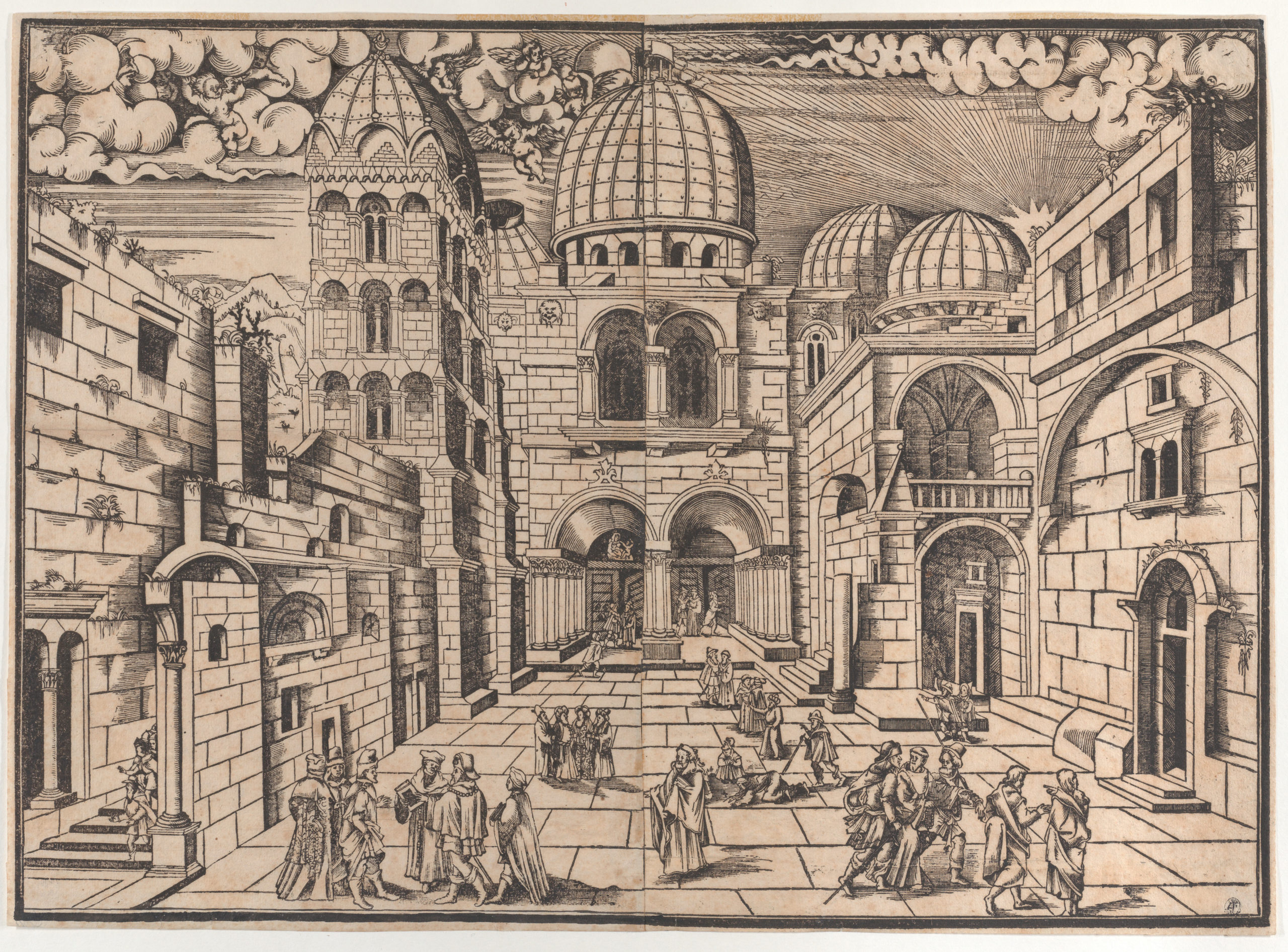

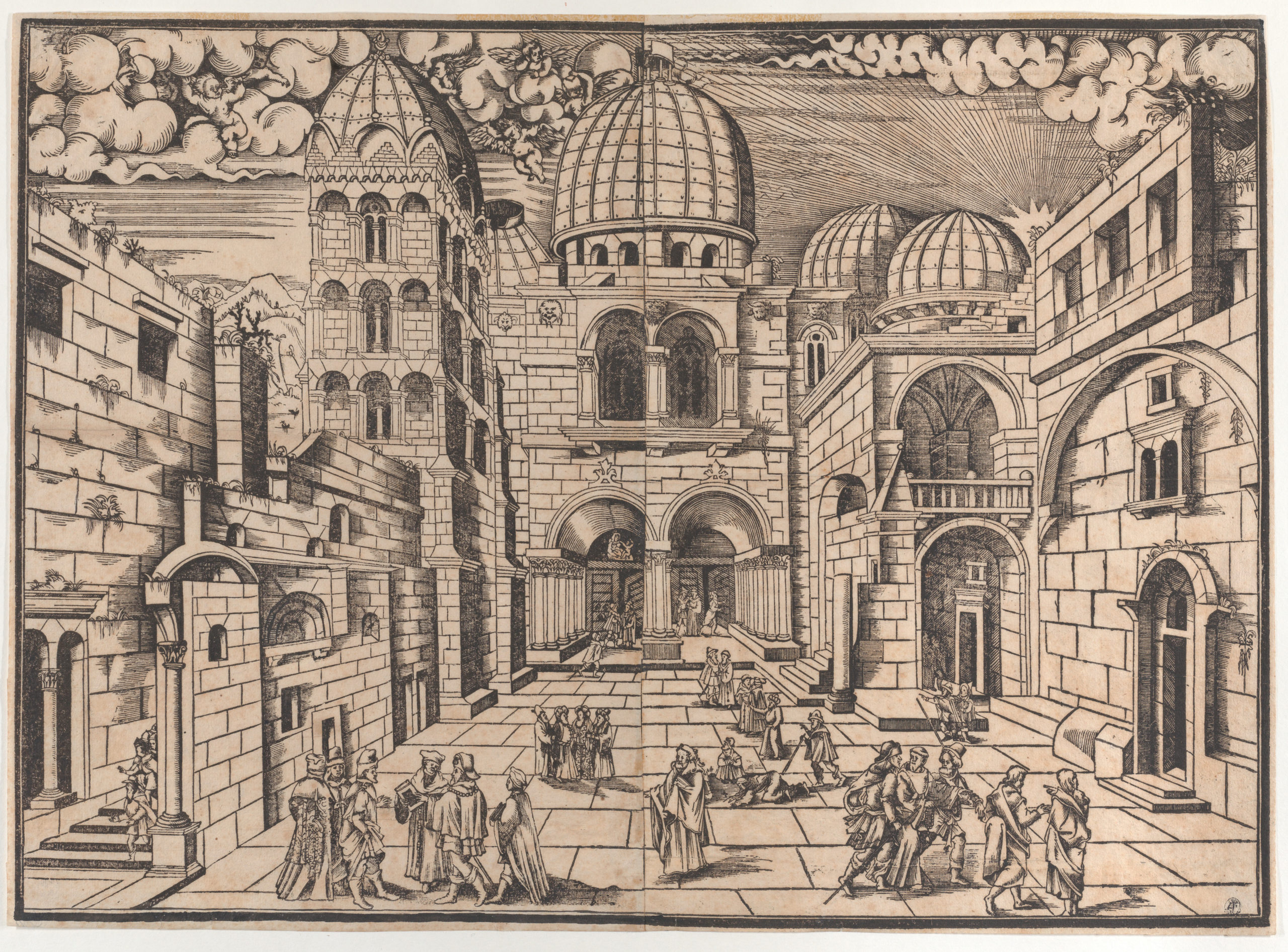

Before 1546 CE Quake

A drawing by Dominik de la Greche of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre apparently before the earthquake when the

Bell Tower Dome to the left was still intact

A drawing by Dominik de la Greche of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre apparently before the earthquake when the

Bell Tower Dome to the left was still intactfrom The Met - NYC After 1546 CE Quake |

|

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Church of the Holy Sepulchre |

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Church of the Holy Sepulchre |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Church of the Holy Sepulchre |

Before 1546 CE Quake

A drawing by Dominik de la Greche of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre apparently before the earthquake when the

Bell Tower Dome to the left was still intact

A drawing by Dominik de la Greche of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre apparently before the earthquake when the

Bell Tower Dome to the left was still intactfrom The Met - NYC After 1546 CE Quake |

|

|

- Earthquake Archeological Effects chart

of Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Earthquake Archeological Effects (EAE)

Rodríguez-Pascua et al (2013: 221-224)

| Effect | Location | Image(s) | Description | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Church of the Holy Sepulchre |

|

|

Ambraseys, N. N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: a multidisciplinary study of seismicity up to 1900.

Corbo, V. C. (1981). Il Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme : aspetti archeologici dalle origini al periodo crociato. Franciscan Print. Press. Vol 1-3

Corbo, V. (1988). Il Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme, Vol. 38. Nova et vetera. Liber Annuus, pp. 381-422.

Garbarino, 0. (2001). II Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme: la rappresentazione tridimensionale de dati materiali come ambito privilegiato della filologia e fase ulteriore della ricerca archeologica

, PhD thesis. Universita di Genova.

Garbarino, O. (2005). Il Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme. Appunti di ricerca storico-architettonica. Liber Annuus, 55(1), 239–314.

Eutychius, Patriarch of Alexandria (1906). Annales, sive liber historicus a tempore Adami ad annum Hegirae Islamiticae. Beryti: E Typographeo Catholico. (in Arabic)

Kazmer, M. (2025) The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and earthquakes

, Central European Geology

Pearse, R. (comp. 2024). The Annals of Eutychius of Alexandria (English translation, draft and combined files). Retrieved from Roger-Pearse.com.

Selden, J., & Pococke, E. (1658–1659). Contextio gemmarum, sive, Eutychii Patriarchae Alexandrini Annales. Oxford: Printed for the Authors. (Latin translation of the Annals of Eutychius of Alexandria).

Tucci, G. (Ed.) (2019). Jerusalem. The Holy Sepulchre. Research and Investigations (2007–2011)

. Collana di restauro architettonico 14. Altralinea Edizioni, Florence, Italy, p. 335.

Vincent-Abel, Jerusalem Nouvelle, 40-300

W. Harvey, Church of the Holy

Sepulchre, Jerusalem, London 1935

E. B. Smith, The Dome: A Study in the History of Ideas (Princeton

Monographs in Art and Archaeology 25), Princeton 1950, 16-29

V. Corbo, LA 12 (1962), 221-304

14

(1964), 293-338

15 (1965), 316-318

19 (1969), 65-144

38 (1988), 391-422

id., II Santo Sepolcro di

Gerusalemme 1-3, Jerusalem 1981-1982

A. Ovadiah, Corpus of the Byzantine Churches in the Holy Land

(op. cit.), 75-77

Supplementum 2, 134-138

M. T. Petrozzi, Dal Calvaria a! S. Sepolcro (Quaderni de La

Terra Santa), Jerusalem 1972

D. Barag and J. Wilkinson, Levant 6 (1974), 179-187

C. Coiiasnon, The

Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, London 1974

id., Atti del IX Congresso lnternazionale di

Archeologia Cristiano[[ 1975, Vatican City 1978, 163-166

Y. Tsafrir (op. cit.), 587-600

M. Broshi, IJNA

6 (1977), 349

S. de Sandoli, Calvary and the Holy Sepulchre: Historical Outline (The Holy Places of

Palestine), Jerusalem 1984

S. Eisenstadt, BAR 13/2 (1987), 46-49

G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville, Journal of

the Royal Asiatic Society 2 (1987), 187-207

G.-W. Nebe, Zeitschrift fur die Neutestamentliche

Wissenschaft 78 (1987), 153-161

J. D. Purvis, Jerusalem, The Holy City: A Bibliography (op.

cit.), 320-334

G. R. Stone, Buried History 24 (1988), 84-97

Y. Boiret, MdB 61 (1989), 41-43;

N. Kenaan Kedar, ibid., 37-40

M. Biddle and B. Kjolbye-Biddle, PEQ 122 (1990), 152

A. Recio

Veganzones, Christian Archaeology in the Holy Land: New Discoveries (V. C. Corbo Fest.), Jerusalem

1990, 571-589

Walker(op. cit.), 235-281

D. Pringle, BAlAS IO (1990-1991), 108-110

J. M. O'Connor,

Les Dossiers d'Archiologie, 165-166 (1991), 78-87

J. Patrich, Ancient Churches Revealed, Jerusalem (in

prep.).

S. Gibson & J. E. Taylor, Beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem: The Archaeology and Early

History of Traditional Golgotha (PEF Monographs: Series Minor 1), London 1994

ibid (Reviews) LA 44

(1994), 725–729. — BAIAS 14 (1994–1995), 64–66. — IJNA 24/1 (1995), 81–82. — PEQ 127 (1995), 173.

— BAR 22/4 (1996), 16–17

M. Biddle, The Tomb of Christ: History, Structural Archaeology and Photogrammetry, Stroud, Gloucestershire 1999

ibid. (Reviews) RB 106 (1999), 441–446. — MdB 125 (2000),

59. — PEQ 134 (2002), 173–176. — JRA 15 (2002), 688–690

id. (et al.), La chiesa del Santo Sepolcro a

Gerusalemme, Milano 2000

id. (et al.), The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, New York 2000

C. Joffe, Armenian Mosaics in the Holy Sepulchre Church (Calendar), 2000

J. Krüger, Die Grabeskirche zu Jerusalem:

Geschichte-Gestalt-Bedeutung, Regensburg 2000

ibid. (Review) Antike Welt 32 (2000), 676–677

J. Seligman & G. Avni, ESI 111 (2000), 69*–70*

G. Avni (& J. Seligman), One Land—Many Cultures, Jerusalem

2003, 153–162

V. Clark, Holy Fire: The Battle for Christ’s Tomb, London 2005

J. Krüger, Saladin und die

Kreuzfahrer (Publikationen der Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen 17

Schriftenreihe des Landesmuseums für Natur

und Mensch, Oldenburg, 37

eds. A. Wieczorek et al.), Mainz am Rhein 2005, 31–36

C. Morris, The Sepulchre of Christ and the Medieval West: From the Beginning to 1600, Oxford 2005.

- download these files into Google Earth on your phone, tablet, or computer

- Google Earth download page

| kmz | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Right Click to download | Master Jerusalem kmz file | various |